Abstract

Transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) people are frequently exposed to stigma, discrimination, and violence, with adverse impacts on wellbeing. The ‘Minority Stress Model’ and sources of gender affirmation both highlight the impact of social oppression and provide useful means to understand how TGNC people can develop their resilience and what may contribute to different ways of coping. While this stress has been explored in previous reviews, a limited focus on lived experiences constrained discussion of how coping approaches could be put into action in relation to gender affirmation. Therefore, the current review sought to better understand TGNC individuals’ opportunities for gender affirmation through their experiences of coping with minority stress. A systematic search yielded nine studies reporting qualitative data related to adaptive coping. Framework synthesis was applied through an a priori framework, based on minority stress and gender affirmation research, which generated eight themes: four themes privileging psychological affirmation comprised ‘defining one’s own gender identity’, ‘fostering self-belief’, ‘using information and knowledge’, and ‘drawing upon other identities’; and four themes offering social affirmation comprised ‘connecting with the TGNC community’, ‘cultivating allies’, ‘advocating for change’, and ‘asserting oneself’. Our findings augment established models and concepts with the delineation of coping responses for TGNC individuals that can support gender affirmation and mitigate minority stress.

Introduction

For transgender and gender nonconforming (TGNC) people, the sex they were assigned at birth does not match their own internal gender identity; yet they must live within social climates rooted in harmful cis/heteronormative assumptions (van der Toorn et al., Citation2020). While there is greater legal recognition of TGNC rights, dichotomising debate has both increased public attention and galvanised groups who are overtly hostile (Bachmann & Gooch, Citation2017). TGNC individuals are consequently exposed to explicit stigma, discrimination and violence as well as micro-aggressions (Testa et al., Citation2015). Given the threatening situations that TGNC people encounter and the potential for harm to them, it would be useful to understand any strategies and actions that TGNC people can engage in to mitigate and navigate the impact of such stressors, and whether doing so may enable access to gender affirmative experiences.

Lloyd et al. (Citation2019) highlight numerous studies that have shown that TGNC people are subject to gender-related discrimination, stigma, rejection, and violence because of their minority status, with adverse impacts on psychological wellbeing and quality of life. The Minority Stress Model (Meyer, Citation1995) examines how minority group membership can contribute to mental health and wellbeing, articulating how minority stressors exist on a distal to proximal continuum of events and experiences, which potentiate internalising negative messages from society, anticipating rejection and discrimination, and identity concealment (Meyer, Citation2015). This model was augmented for TGNC people by Testa et al. (Citation2015) with their Gender Minority Stress and Resilience (GMSR) model, adding the construct of ‘non-affirmation’ when gender identity is not recognised by others.

Both models highlight the importance of affirmative experiences; these allow TGNC people to be recognised, or accepted, in their gender identity and expression (Reisner et al., Citation2016). This has been explored with the gender affirmation framework (Sevelius, Citation2013) and further advanced by Glynn et al. (Citation2016) through their affirmative domains that acknowledge TGNC identities and enhance wellbeing. This includes medical affirmation (hormone blockers and replacements, and surgery), psychological (self-respect and validation, comfort and acceptance of gender identity, resisting internalised transphobia) and social processes (pronoun and name choices, interpersonal and societal acknowledgement of identity and needs) and legal status (name change, gender recognition, gender markers) (Glynn et al., Citation2016; Reisner et al., Citation2016). Importantly, alongside the Minority Stress model the gender affirmation framework recognises that social oppression increases psychological distress and decreases access to gender affirmation, consequently reducing resilience.

Indeed, social oppression through non-affirmation is not uncommon. A UK Government survey (Government Equalities Office, Citation2019) revealed over half of respondents had avoided expressing their gender identity for fear of others’ negative reactions. While this is consistent with previous research finding that TGNC people often attempt to hide or conceal their gender (Bockting et al., Citation2013), Meyer (Citation2015) highlights that many TGNC people do engage with minority stressors and draw upon sources of resilience in these contexts. Indeed, Meyer (Citation2015) positions resilience as an essential part of the minority stress model. For TGNC people, resilience i.e. “being able to survive and thrive in the face of adversity” (Meyer, Citation2015), may include adopting specific coping strategies to mitigate the impact of minority stress.

Lazarus and Folkman (Citation1984) describe coping as “cognitive and behavioural efforts to manage specific external and internal demands that are appraised as taxing or exceeding the resources of the person”. Coping efforts may aim to increase wellbeing, but certain approaches can have consequences that reduce this in the long-term. This difference can be framed as either adaptive or maladaptive coping, where the former includes directly mitigating the distress-causing problem, and the latter may result in not dealing directly with the problem by avoiding the stressor (Folkman & Lazarus, Citation1985).

These definitions can be used to underpin how minority stressors may be responded to, by categorising coping strategies as adaptive or avoidant. Avoidant coping involves disengaging from the minority stressors, such as through concealment of gender (e.g. Miller & Kaiser, Citation2001), and although this may protect against immediate effects of stigma it could become a safety behaviour (e.g. McManus et al., Citation2008); concealment perpetuating distress by reducing exposure to situations that may enable resilience to develop (Wells et al., Citation1995). By contrast, adaptive coping involves active engagement (Compas et al., Citation2001) with a stressor and there is evidence that this approach can protect against the negative consequences of stigma (Chronister et al., Citation2013; Talley & Bettencourt, Citation2011).

A range of protective factors have consistently been identified in the literature (Bariola et al., Citation2015; Bockting et al., Citation2013; Singh & McKleroy, Citation2010; Testa et al., Citation2015) and are consolidated within two recent quantitative reviews by McCann and Brown (Citation2017) and Valentine and Shipherd (Citation2018), and a non-systematic review by Matsuno and Israel (Citation2018). These papers highlight resilience against discrimination can be garnered through social support from peers and family, identity pride and comfort, authentic expression of gender, oppression awareness, TGNC community connections and resources, and hope. All these experiences may offer TGNC people routes to affirmative experiences of their gender identity.

The above factors echo concepts within the gender affirmation framework. Psychological gender affirmation can include experiences of identity pride, authentic expression of gender identity, and recognition of oppression; it is also associated with lower depression, reduced anxiety and higher self-esteem (Glynn et al., Citation2016; Riggle et al., Citation2011). Likewise, social gender affirmation involves community connectedness along with recognition and acceptance from peers, family, and the wider public with access to gender affirmative resource previously described. Hendricks and Testa (Citation2012) suggest social supports can protect TGNC people from the effects of minority stress. However, despite emergent evidence on experiences that may be affirmative, it is unclear how TGNC people may draw upon such protective factors in an active and intentioned way, akin to adaptive coping, when managing minority stress.

The domains of psychological and social affirmation provide a lens through which to identify adaptive coping strategies that can affirm gender identities in the face of minority stress. Previous quantitative reviews (McCann & Brown, Citation2017; Valentine & Shipherd, Citation2018) precluded more nuanced exploration of how and with what success coping strategies were used. Neither review examined how such coping strategies may link to affirmative processes. The ‘TRIM model’ developed by Matsuno and Israel (Citation2018) collated potentially useful resilience strategies among ‘transgender’ people in the context of minority stress, but without a clear search process, inclusion criteria, or quality appraisal it is unclear how a model was developed without potential bias. It is therefore timely to review research systematically with a robust, transparent methodology.

More nuanced understanding of qualitative research may reveal how minority stress and related coping responses are experienced by TGNC people, permitting exploration of how adaptive coping operates and drawing on research focusing on wellness and thriving, rather than just seeing TGNC people as “objects of vulnerability” (Glynn et al., Citation2016). The current review thus seeks to interrogate the qualitative research literature to explore the gender affirmative experiences sought out or enacted by TGNC people to manage minority stress. It aims to synthesise the available literature to capture these experiences for a greater range and population than individual studies can. This will explore a) the experiences TGNC people report benefit them when responding to minority stress b) the adaptive coping strategies they use and c) how these fit within a gender affirmative framework.

Method

Qualitative meta-synthesis has been challenged as contravening the essence of qualitative enquiry through bringing qualitative studies together (Jensen & Allen, Citation1996). However, such synthesis can address qualitative studies conducted in isolation and provide “more formalized knowledge” (Zimmer, Citation2006). Qualitative synthesis can also address potential limitations of quantitative reviews, which may be less grounded in participants’ lived experiences and own narratives. For the current review, a framework synthesis approach was taken, guided by previous methods (Carroll et al., Citation2013; Ward et al., Citation2013).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria were applied to guide selection of suitable papers for the synthesis. The SPIDER approach to inclusion criteria was used to inform on studies’ eligibility (see ).

Table 1 SPIDER inclusion criteria.

Inclusion criteria required that papers be in English, peer-reviewed, and included qualitative research designs reporting findings that could be examined for qualitative synthesis (determined by the inclusion of direct participant quotes and discussion of these by the authors). Papers were excluded if: they solely utilised quantitative methods, there was no explicit reference to minority stress (including constituent components of discrimination, stigma, prejudice and oppression) in which experiences of coping needed to be grounded, there was no reference to adaptive coping concepts that could facilitate gender affirmative experiences, and they did not include sufficient numbers of TGNC participants or these were conflated with sexual minority participants.

Search strategy

The Cochrane Database and PROSPERO (International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews) were consulted to ensure there were no previous, current, or proposed systematic reviews on the current topic. A scoping exercise determined the extent of possible literature available relevant to the review topic. This established the presence of qualitative papers reporting TGNC minority stress and resilience and coping but these tended not to have a primary focus on adaptive coping strategies, although this was often included as a facet of findings. To ensure sufficient data for synthesis we adopted a search strategy expansive enough to discover findings that were not necessarily the primary focus of a study. A systematic search was undertaken in December 2019 using four databases; PsycINFO, Scopus, ASSIA, and Web of Science via the OVID gateway, chosen to encompass psychological, social care and healthcare literature.

Search terms were derived from the review questions, with the process refined by removing terms that overly restricted the returned results, supported by a specialist University librarian. The final search terms (transgender or transsexual or transwoman or transwomen or transman or transmen or “gender non*” or “gender diverse” or “gender variant” or “gender minority” and "minority stress") were felt to capture the range of terms that TGNC individuals may identify with and likely to elicit papers that explored minority stress with this population, after which further examination determined their eligibility for inclusion.

Study selection

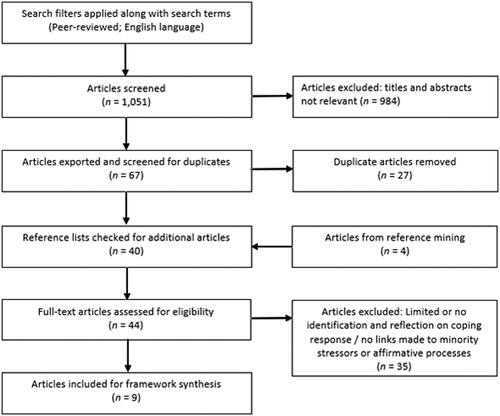

Study selection involved screening papers regarding eligibility for inclusion; displays this process.

After applying inclusion criteria, 1,051 papers were identified. After examination of titles and abstracts, 984 were removed. We examined a high number of papers at this initial stage to ensure none were missed because of the inclusion/exclusion criteria’s specificity. Papers were typically excluded at this stage because they were not qualitative in nature, did not include TGNC participants or lacked focus on either minority stressors or coping responses.

The remaining 67 papers were exported to RefWorks with 27 papers then removed as duplicates. The reference lists of the 40 papers selected for full reading were scrutinised for potentially relevant papers not identified during the initial literature search, eliciting four further papers. Thus 44 papers were read in full, with 35 papers removed as they did not consider adaptive coping responses or strategies in either results or discussion. Nine papers remained for quality appraisal and final inclusion in the meta-synthesis.

Quality appraisal and data extraction

Quality appraisal was undertaken using a bespoke tool developed from The Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP, Citation2017) and enriched using the analysis of quality appraisal criteria for qualitative research by Santiago-Delefosse et al. (Citation2016). Quality was therefore assessed across 12 key domains: aims; research design; methodology; recruitment; sampling; ethics; data collection; analysis; verification methods; credibility; transferability; and reflexivity. Within each domain, specific indicators of quality were assessed as being present, partially present, or absent. Issues in sampling, qualitative analysis or reporting would have constituted fundamental flaws leading to exclusion. Data extraction was incorporated within the quality appraisal tool and relevant information was collated under the key headings of research aims, participant characteristics, data collection methods, approach to analysis, and key findings from analysis and discussion to develop an understanding of the study characteristics.

Framework-based synthesis

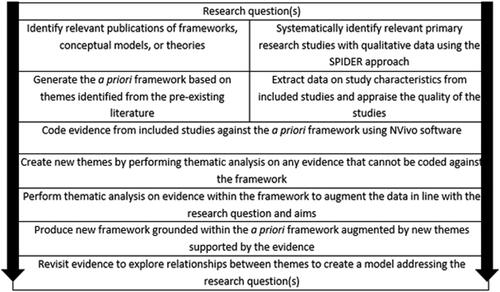

Our data analysis involved scrutiny of findings across the studies using framework-based synthesis (e.g. Carroll et al., Citation2011; Ward et al., Citation2013), an approach both augmentative and deductive, building on an existing framework of themes to map and code the data. Framework synthesis () begins by creating a framework of a priori themes against which to code data from included studies. This framework is then modified in response to the evidence reported and thematic analysis may be applied to new emerging themes, so that the final revised framework may include both modified factors and new factors.

Figure 2 Framework synthesis method; adapted from Carroll et al. (Citation2013).

We selected framework synthesis given the pre-existing models of minority stress, gender affirmation, and resilience and coping. Psychological affirmation and social affirmation offered the starting point for the a priori framework, informed by pre-existing findings on sources of affirmation. This provides the initial conceptual framework to guide analysis of the data extracted from the nine included studies () from which adaptive coping strategies could be identified. In developing the initial framework and throughout the synthesis, the first author considered their own position due to identifying with the LGBT community and previous experience working clinically with TGNC people, holding a view there would be evidence of adaptive coping within the literature. None of the authors identifies as trans and each identify as cis. As Paz Galupo (Citation2017) has noted, it is recognised that since the authors do not hold lived experience of being trans, cis identities are a potential source of bias and affect the way we may frame the results of this review. As recommended, in each stage of the review process it was endeavoured to check assumptions about gender to inform decisions and mitigate potential bias.

Table 2 The a priori concepts on gender affirmation and coping.

Data for coding and mapping onto the a priori framework comprised direct verbatim quotations from participants and findings reported by authors. The software programme NVivo was used to construct nodes for the superordinate themes of social and psychological affirmation, under which were nodes for the pre-existing themes (see ). Quotes and extracts that supported these themes were grouped within them. Data reflecting adaptive coping that did not fit within these were held under a separate node for later thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) to generate additional themes. The pre-existing themes were continually revisited and revised as new data was added to develop the pre-existing framework and flesh out adaptive coping strategies. It was not intended to generate superordinate themes as these were already present.

Results

Nine papers were selected for inclusion in the present review: Alanko et al. (Citation2019); Bockting et al. (Citation2019); Chen et al. (Citation2017); Jackman et al. (Citation2018); Matsuzaka (Citation2018); Mizock et al. (Citation2017); Scandurra et al. (Citation2019); Singh et al. (Citation2011); and Singh et al. (Citation2014). The key characteristics for each study were collated and their quality appraised before being analysed through framework synthesis.

Summary characteristics of the selected studies

Summary characteristics of the included studies are presented in . The selected papers all utilised qualitative methodologies and were undertaken in Western developed countries (the USA, Finland, and Italy). Papers reported data from 361 participants, but many (n = 201) came from Chen et al. (Citation2017). Participants included trans women (n = 194), trans men (n = 104), and non-binary individuals (n = 63) including genderqueer, gender-fluid and non-conforming identities.

Table 3 Summary characteristics of selected studies.

The key findings for all nine papers included responses to distal stressors of societal stigma and discrimination, socio-political changes relating to TGNC issues, and experiences within non-TGNC specific communities, as well as proximal stressors of micro-aggressions, non-affirmation and rejection. None of the papers specifically sought to examine adaptive coping but this was captured within their findings and reflected engaging with minority stress through purposeful strategies with a clear element of agency. Avoidant coping strategies were also identified from some papers and included detachment from stressors, submission to oppression, self-harm as a means of externalising pain, and concealment of gender.

Quality appraisal

From initial quality appraisal all nine papers sufficiently met the quality indicators with no concerns significant enough warrant exclusion. Quality was also checked through the independent appraisal of four papers by the second author, where little discrepancy was noted and consensus achieved through discussion. All nine papers fully met at least nine of the twelve quality domains and seven quality domains were fully met by all papers (research design; recruitment; sampling; ethics; data collection; analysis; credibility). Four papers were identified as being comparatively strong in quality; Alanko et al. (Citation2019), Mizock et al. (Citation2017), Singh et al. (Citation2011), and Singh et al. (Citation2014) given the number of quality indicators met. Poorer quality was evident across the included papers for three quality domains: ‘clear and logical aims’ (Bockting et al., Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2017; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Mizock et al.,Citation2017), ‘appropriate transferability’ (Bockting et al., Citation2019; Scandurra et al., Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2014), and ‘reflexive account provided’ (Bockting et al., Citation2019; Chen et al., Citation2017; Jackman et al., Citation2018; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Scandurra et al., Citation2019).

Framework synthesis

The framework synthesis identified eight themes of adaptive coping in response to minority stress. Themes were analysed in respect of psychological affirmation and social affirmation constructs, suggesting four adaptive coping strategies within each being used to achieve affirmative experiences (). Psychological affirmation themes included: defining one’s own gender identity; fostering self-belief; using information and knowledge; and drawing upon other identities. For social affirmation, themes comprised: connecting with the TGNC community; cultivating allies; advocating for change; and asserting oneself.

Table 4 Presence of themes across studies.

Psychological affirmation

‘Defining one’s own gender identity’ emerged from six of the papers and refers to how TGNC participants independently describe their gender and communicate this to others using “their own words and concepts” (Singh et al., Citation2014, p. 211). By engaging in self-discovery and definition in response to distal powers of gender oppression and rejection, TGNC participants were able to develop their sense of self and take ownership of who they are, “Well, I am a woman. And I might be the only one who knows that, and that’s OK” (Singh et al., Citation2011, p. 23). This process of self-definition had both a positive impact on how participants saw themselves and provided them with a means to engage with others about their identity in which they could hold some sense of certainty and resist non-affirmation. As Singh et al. (Citation2011, p. 23) state, this enabled “being able to use their own words and terms to define their gender helped them cope with discrimination”, also illustrated by one participant for whom defining their identity meant “I had the courage to tell her and my dad” (Scandurra et al., Citation2019, p. 67). This adaptive coping strategy provided both increased comfort and pride with one’s gender identity against cisnormative constraints – “they tried to put me in the same category. But now it’s not my problem anymore” (Alanko et al., Citation2019, p. 126).

‘Fostering self-belief’ emerged from five of the papers and describes how participants seek to remind themselves of their own self-worth, value, hopes and beliefs. It is often described in conflict with non-affirmation from others, “I try to value my life as more important than letting someone put me down” (Mizock et al., Citation2017, p. 288). Intentional attempts to value oneself and believe in their ability to manage can combat negativity. Within this theme, participants often drew upon their future hopes, maintaining an optimism to anticipate a better future rather than current conflict (Bockting et al.,Citation2019) and illustrated in Singh et al. (Citation2011, p. 24), “I would remember that the first 18 years were going to be tough, and the next 67 years were going to be mine”. Through explicit development of self-belief via recognising one’s own value, strengths and hopes, participants expressed greater comfort both in the present and anticipated future.

‘Using information and knowledge’ emerged from six of the papers and reflects how participants actively sought out information and knowledge about gender, resources available, the experiences of other TGNC people, and the wider socio-political climate. This involved more practical engagement as illustrated by Bockting et al. (Citation2019, p. 169) through “learning new information about their legal rights as TGNC people and the importance of trans-affirming legislation”. This also offers greater opportunity for participants to develop comfort with their identity and to empower themselves and others, “I educate myself and educate people around me about how to work around the system” (Bockting et al., Citation2019, p. 169). Using information and knowledge about gender identity and TGNC issues also enabled participants to resist internalising transphobia as a potent minority stressor, and illustrated in Singh et al. (Citation2011, p. 23) who describe “awareness of oppression as helping them to identify societal messages that were not trans-positive” and therefore better internalise affirmative ones.

‘Drawing upon other identities’ emerged from four of the papers and describes how participants identify other strengths when their gender identity is under threat. A flexible view of identity and integrating their gender with other parts of themselves enabled participants to bolster both gender identity pride and comfort. Facets of identity from belonging to other communities could be drawn upon, as well as past experiences in which they overcame difficulties. Singh et al. (Citation2014, p. 213) highlight how participants “identified successful strategies of addressing mental health challenges and then reframed these strategies to address trans-related challenges” and Jackman et al. (Citation2018) report how TGNC individuals who self-harm accessed ways to manage this in the context of minority stress. Drawing upon other identities and experiences related to these were a source of resilience, succinctly captured by one army veteran participant (Chen et al., Citation2017, p. 69) stating “I am a warrior on multiple levels”. By drawing upon other identities, participants were able to locate strengths and resources from other aspects of themselves to resist non-affirmation.

Social affirmation

‘Connecting with the TGNC community’ emerged from seven of the papers and describes how TGNC participants engage with peers and wider TGNC communities. By forging connections offering acceptance and recognition, proximal and distal minority stressors are resisted - “now I have a whole group of friends who actually understand now what being trans is” (Jackman et al., Citation2018, p. 593). Participants described how finding a community of peers provided direct support when struggling and helped them to cope, “you have a group…of trans and gender non-conforming people to call on if you need help” (Bockting et al., Citation2019, p. 168). Connection with the TGNC community was utilised to help understand gender identity, manage relationships, deal with threats from others, and address mental health difficulties (Jackman et al., Citation2018; Matsuzaka, Citation2018; Mizock et al., Citation2017; Singh et al., Citation2014). Chen et al. (Citation2017, p. 72) highlight how the TGNC community can be drawn upon when individuals may be struggling by themselves “to endure and possibly grow from challenging experiences”. Actively connecting with a wider TGNC community provided TGNC people with support for difficulties encountered, countering non-affirmative experiences from wider society.

‘Cultivating allies’ emerged from five of the papers and reveals how participants sought out and built relationships with non-TGNC people, including in the workplace, cisgender friends, and family members – but particularly those in influential or more powerful positions e.g. ‘Supportive colleagues and bosses were also identified as a source of power’ (Alanko et al., Citation2019, p. 125). In the workplace, allies provided security through their availability and support for challenges encountered, “talking to my supervisors and knowing who I can rely on to defend me if there’s a problem—that was helpful” (Mizock et al., Citation2017, p. 288). Supportive allies could come from a range of backgrounds and situations but often involved already being in positions of care and served as important sources of affirmation, “many research participants shared positive and empowering experiences of speaking directly with a teacher or professor” (Singh et al., Citation2014, p. 216). Allies could be sought across a range of settings including where cisnormative views dominated, “I’ve always had (AA) sponsors who, we would…try and get at what’s actually useful and what I identify with” (Matsuzaka, Citation2018, p. 168). Cultivating relationships with non-TGNC people provided support when needed, strengthened relationships and access to social power, and allowed participants to be recognised and accepted for their TGNC identity.

‘Asserting oneself’ emerged from seven of the papers and describes how TGNC people can directly communicate their needs and views to others, particularly standing up to proximal hostilities encountered. Many participants described this as empowering, “I say things that everyone else is too afraid to say” (Mizock et al., Citation2017, p. 290) and can enable them to have their needs recognised and identity seen by others. Asserting oneself involved objecting to mistreatment as illustrated by one participant who would “stand up for myself and to say I don’t deserve to be treated like this” (Bockting et al., Citation2019, p. 169). This meant confronting hostility directly which provided further confidence to be assertive in one’s right to exist and be recognised, “If people are yelling nasty insults…at least I can be assertive about it and speak up for myself and my own worth. And that feels amazing and sustains me” (Singh et al., Citation2011, p. 23). Taking a stand and being assertive also provided opportunity to exert more control and influence over situations and, as stated by Matsuzaka (Citation2018, p. 169), this “results in beneficial changes at individual and collective levels, but also has ramifications for the larger (AA) community”. Responding to minority stressors by asserting oneself enables TGNC people to engage directly with sources of minority stress, affirm their right to exist, be accepted, and have their identity recognised.

‘Advocating for change’ emerged from five of the papers and involves participants actively engaging in social activism for trans rights and issues at a distal level. For some participants, this focused on rights in the workplace e.g. “talking to supervisors, consulting with human resources, and promoting a TGD-inclusive bathroom policy” (Mizock et al., Citation2017, p. 288), and taking on leadership positions that would enable them to influence wider changes around them. Adopting such positions also offered opportunity to act as role models for others and respond to marginalisation (Mizock et al., Citation2017). Advocating for change meant getting involved in broader social activism, which often felt like a necessary part of being a TGNC person since inaction could suggest complicity with oppression, “I think inherently as a transwoman you either have the choice to make yourself a disease or you’re an activist” (Bockting et al., Citation2019, p. 169). Activism was often a source of empowerment where “demonstrations were a way of voicing dissent” (Bockting et al., Citation2019, p. 169), enabling changes in environments important to them. Advocating for change provided social affirmation by drawing attention to the right to be recognised and accepted by others and feelings of empowerment this provides.

Revised framework

The eight themes identified were synthesised to construct a revised framework () based upon the gender affirmation framework and Minority Stress model (Meyer, Citation2015). The framework includes the pre-existing concepts of gender affirmation and the psychological and social sources for this, along with the barrier minority stress can present. The adaptive coping themes identified through this review advance these by showing how TGNC people can actively use different strategies to overcome the impact of minority stress and access affirmative experiences.

Table 5 Revised framework of adaptive coping for TGNC people.

Discussion

The current review aimed to synthesise experiences reflecting adaptive coping by TGNC people to counter minority stress and enable affirmative experiences. Although previous reviews have been conducted in this area (e.g. McCann & Brown, Citation2017; Valentine & Shipherd, Citation2018), the lived experiences of TGNC people engaging in adaptive coping had not been sufficiently examined. Nine studies undertaking qualitative exploration were included for review, and their findings integrated via framework synthesis, permitting a more detailed and nuanced understanding of the intentional strategies and responses engaged in by TGNC people in the context of minority stressors within cis/heteronormative societies and settings that can oppress opportunities for gender affirmation.

Following application of the a priori framework, eight themes were identified under the pre-established superordinate themes of psychological and social gender affirmation. These were either modifications of pre-existing themes or additionally generated based on evidence from the nine papers. This formed a revised framework, consonant with framework synthesis methodology to incorporates gender affirmation concepts (Sevelius, Citation2013; Testa et al., Citation2015) and minority stress. Identified adaptive coping responses are included in the revised framework, providing further detail on how individuals may work towards affirmative experiences and mitigate minority stress. Consonant with previous reviews (McCann & Brown, Citation2017; Valentine & Shipherd, Citation2018), and findings by Matsuno and Israel (Citation2018), this review identified themes associated with community and social connections, identity, and pride. Systematic synthesis of the data brings together qualitative findings from across selected studies to provide a more nuanced understanding of adaptive coping strategies that are engaged in by TGNC individuals.

Under psychological affirmation, the four emergent themes may all help resist cisnormative pressures and hostility, potentially mitigating internalising transphobia from distal societal messages and maintaining resilience against proximal experiences of discrimination and aggression. ‘Defining one’s own gender identity’ and ‘fostering self-belief’ relate directly to previously identified facets of comfort and pride in one’s gender identity by illustrating how this might be achieved and enhancing self-efficacy to persevere when faced with adversity (Gillespie et al., Citation2007). Alongside self-efficacy, one of three ‘fundamental building blocks of resilience’ (Shastri, Citation2013) self-definition and belief may also support ‘a secure base’ and ‘good self-esteem’ which comprise the other keystones of resilience. ‘Accessing knowledge and information’ enriches the previously identified awareness of oppression, and highlights this as an important resource for TGNC people to utilise to manage minority stressors. ‘Drawing upon other identities’ did not feature in the pre-existing TGNC literature that informed the a priori framework. However it suggests that actively integrating gender with other aspects of self has value, and resonates with intersectionality approaches to distress in which variation in coping and sources of resilience depend on other aspects of identity (McConnell et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, the themes providing psychological affirmation can be categorised as adaptive coping as they involve either engagement with minority stressors encountered or internally addressing them to mitigate their impact. They echo the privileging of ‘psychological flexibility’ as protective against minority stress; being able to define one’s gender identity, foster self-belief and make use of internal resources and experiences to address minority stressors adaptively and creatively (Lloyd et al., Citation2019). Psychological flexibility can enable TGNC people to connect with the present to change or persist in behaviour that is in line with their values (Hayes et al., Citation1999), and permits internalising gender affirmative experiences.

The four themes emerging as social affirmation all suggest coping can be enabled through increasing recognition and acceptance of gender identity by others. ‘Community connectedness’ was a key theme that required little modification from the a priori framework and is consistent with previous research (e.g. McCann & Brown, Citation2017), along with engaging in activism and building relationships. That community connectedness can mitigate minority stress is consistent with research demonstrating the power of group identification to increase social support, stereotype rejection, and resistance to stigma (Crabtree et al., Citation2010) and, in terms of social capital, reflects the process of bonding capital (Schuller, Citation2007). Intentionally seeking out ‘allies’ can also enhance social capital through ‘bridging capital’ to provide the links a community has with others that are different (Schuller, Citation2007). Proximal minority stressors can be challenged through increased social power where assertive engagement within social interactions could promote an active voice as a TGNC person. It is notable that adaptive coping responses involving family support were not greatly evidenced in the data (except for Alanko et al., Citation2019), despite this being previously identified as a key source of affirmation (Matsuno & Israel, Citation2018; McCann & Brown, Citation2017). This may reflect a more inert influence from family, which may be protective if present or detrimental when absent or overtly hostile (Katz-Wise et al., Citation2016). However, seeking allies and connecting with the TGNC community both demonstrate how alternative support and belonging can be actively sought and may lessen any detriment from family rejection (e.g. Barr et al., Citation2016).

The social affirmation coping responses reveal ways of resisting the distal minority stressors and societal oppression, reflecting the benefits of group-level coping and identification (Bariola et al., Citation2015; Crabtree et al., Citation2010; Matsuno & Israel, Citation2018) for TGNC individuals. While Matsuno and Israel (Citation2018) previously collated resilience factors at the group or individual level, the current review advances understanding by evidencing adaptive coping responses that can better enable gender affirmation to protect against minority stress. Moreover, the coping experiences described under both psychological and social affirmation reflect a progression from self-belief, definition, and knowledge to actively building relationships, asserting oneself and advocating for change; this illustrates the movement from ‘social abuse to social action’ (Holland, Citation1992).

Indeed, empowerment has long been a key concept in community psychology where, by understanding the strengths of individuals and communities, wellbeing can be enhanced by making positive changes and challenging inequities in the environment (Zimmerman, Citation2000) such as minority stress for TGNC people. The coping responses reported in the current review reveal how accessing power embedded in social interactions can increase social influence in both dyadic interactions and within wider social systems (Cattaneo & Chapman, Citation2010).

However, TGNC people can experience numerous barriers to accessing support, professional or peer (McNeil et al., Citation2012), made more difficult if experiencing psychological distress. TGNC individuals with ongoing mental health problems may require therapeutic intervention before being able to engage in the adaptive coping responses described in this review. Encouragement and support to move away from avoidant coping strategies, such as concealment and avoidance of stressors, while still managing safely in relation to real threats from hostile others may need to be offered through services.

Strengths and limitations

The current review is the first to critically appraise and systematically synthesise literature reporting on adaptive coping, which can foster empowering responses for TGNC people managing minority stress. It offers initial direction on developing processes permitting more gender affirmative experiences. The findings were incorporated into the existing literature and theory through framework synthesis while providing useful information on what people can actively do to feel affirmed and challenge sources of minority stress. However, the concepts elicited are broad in nature and do not direct precise strategies. A limitation is the specific focus on participants’ intentional responses, which neglects how reactive and immediate coping may interact, subvert, and undermine action. Acute stress can reduce capacity to fully engage in coping, which is well-articulated in compassion-focused models (e.g. Gilbert, Citation2009) where ‘threats’ can overwhelm planned adaptive responses, and necessitate avoidant styles for survival.

Furthermore, while framework synthesis may facilitate efficient and succinct analysis of evidence acknowledging pre-existing concepts, this approach may be reductionist. Themes identified through the lens of current understanding may constrain emergence of divergent themes. The current review attempted to counter this by ensuring analysis included space for new concepts, and the breadth and rigour of the initial search stage, and examination of numerous papers reduced likelihood of papers being overlooked. It is also of note that quality appraisal revealed some included papers lacked ‘appropriate transferability’ (Bockting et al., Citation2019; Scandurra et al., Citation2019; Singh et al., Citation2014) and were contextually specific (sampling from the workplace and AA). Caution regarding the transferability of the results from this review is advised, given many studies were located within the United States. However, as all included papers reported data from Western societies there is likely to be a heterogeneity of experiences, aiding coherent synthesis, given exposure to similar social constructions and pressures for TGNC people.

Finally, given all authors are cisgender, whilst we sought to check our assumptions about gender to inform our approach and interpretation, future reviews and indeed core research should include TGNC authors to further mitigate potential bias.

Implications

Despite the limitations noted the findings have clear clinical utility. Elicitation of coping responses suggests that support could be provided by gender identity clinics and other services for TGNC people. For instance, guidance towards the coping responses outlined and developing skills to meet these if needed e.g. self-esteem, assertiveness, confidence related interventions, and strengths-based identity exploration beyond gender. Third wave therapy approaches such as Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) and Compassion Focussed Therapy (CFT), as well as community perspectives, would be most beneficial.

Value and compassion driven interventions such as ACT and CFT may have particular utility, partly as they are supported by previous research (Lloyd et al., Citation2019), and as they draw upon what matters to TGNC people, enabling meaningful affirmative experiences. The adaptive coping responses described can be understood through a compassion-focussed (Gilbert, Citation2009) lens due to their inclusion of seeking resources, affiliation, and support from others and this is likely to be a helpful model for interventions. The findings also revealed the prominence of connecting with the TGNC community and advocating for change, where support based around social action could be beneficial. Social action therapy enables people to move from being an individualised patient to taking social action (Holland, Citation1992), and could help TGNC groups to devise and implement community projects to engage with socio-political issues, particularly for those struggling with social gender affirmation.

Moreover, these recommendations do not have to exist solely in clinical or healthcare domains. TGNC people may find it helpful to make use of the findings from this review to consider as individuals and within their communities how to incorporate them. Defining one's own identity can be an actively encouraged through people's transition journeys where seeking out relevant information and knowledge can aid communicating one’s needs and support developing connections with others, through which people may learn to assertively advocate for themselves and others. By actively engaging these strategies people within the TGNC community can develop skills and responses to resist the impact of minority stress and attain key sources of gender affirmation.

Future research should focus on exploring the use of the described adaptive coping responses by TGNC people in response to minority stressors. It would be useful to build upon the revised framework and examine more specific coping strategies that could be employed within these. Further exploration of the different outcomes from engaging in adaptive and avoidant coping strategies has merit, in addition to what helps people move towards the former. Research taking a more empowerment-based perspective to explore and foster TGNC strengths already present within the community also has significant value.

Conclusion

Framework synthesis of the elicited literature enabled a new focused identification of the coping responses and strategies reported on and engaged in by TGNC people. Clinical services can offer support to foster such adaptive coping through specific psychological and community-based intervention approaches. Further research would be useful for testing the operation of the new conceptual model with TGNC people and how it can be utilised clinically. The current review also highlighted the importance of gender affirmative experiences for resisting the oppressive impact of minority stress and how this can provide opportunities for empowerment within the TGNC community that they can actively engage in.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (29.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alanko, K., Aspnäs, M., Ålgars, M., & Sandnabba, N. K. (2019). Coping in narratives of Finnish transgender adults. Nordic Psychology, 71(2), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/19012276.2018.1515032

- Bachmann, C. L., & Gooch, B. (2017). LGBT in Britain: Trans report. Stonewall.

- Bariola, E., Lyons, A., Leonard, W., Pitts, M., Badcock, P., & Couch, M. (2015). Demographic and psychosocial factors associated with psychological distress and resilience among transgender individuals. American Journal of Public Health, 105(10), 2108–2116.

- Barr, S. M., Budge, S. L., & Adelson, J. L. (2016). Transgender community belongingness as a mediator between transgender self-categorization and well-being. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000127

- Bockting, W., Barucco, R., LeBlanc, A., Singh, A., Mellman, W., Dolezal, C., & Ehrhardt, A. (2019). Sociopolitical change and transgender people’s perceptions of vulnerability and resilience. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 17, 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-019-00381-5

- Bockting, W. O., Miner, M. H., Swinburne Romine, R. E., Hamilton, A., & Coleman, E. (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Database] https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Carroll, C., Booth, A., & Cooper, K. (2011). A worked example of "best fit" framework synthesis: a systematic review of views concerning the taking of some potential chemo-preventive agents. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 11, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-11-29

- Carroll, C., Booth, A., Leaviss, J., & Rick, J. (2013). "Best fit" framework synthesis: Refining the method” . BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13(37), 37 https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-37

- Cattaneo, L., & Chapman, A. (2010). The process of empowerment: A model for use in research and practice. American Psychologist, 65(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018854

- Chen, J. A., Granato, H., Shipherd, J. C., Simpson, T., & Lehavot, K. (2017). A qualitative analysis of transgender veterans’ lived experiences. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 4(1), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000217

- Chronister, J., Chou, C. C., & Liao, H. Y. (2013). The role of stigma coping and social support in mediating the effect of societal stigma on internalized stigma, mental health recovery, and quality of life among people with serious mental illness. Journal of Community Psychology, 41(5), 582–600. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.21558

- Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127.

- Crabtree, J. W., Haslam, S. A., Postmes, T., & Haslam, C. (2010). Mental health support groups, stigma, and self‐esteem: Positive and negative implications of group identification. Journal of Social Issues, 66(3), 553–569. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2010.01662.x

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2017). CASP (Qualitative Research) Checklist. http://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/dded87_25658615020e427da194a325e7773d42.pdf

- Folkman, S., & Lazarus, R. S. (1985). If it changes it must be a process: Study of emotion and coping during three stages of a college examination. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(1), 150–170.

- Gilbert, P. (2009). The compassionate mind. Constable & Robinson Ltd.

- Gillespie, B., Chaboyer, W., & Wallis, M. (2007). Development of a theoretically derived model of resilience through concept analysis. Contemporary Nurse, 25(1–2), 124–135.

- Glynn, T. R., Gamarel, K. E., Kahler, C. W., Iwamoto, M., Operario, D., & Nemoto, T. (2016). The role of gender affirmation in psychological well-being among transgender women. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(3), 336–344.

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K., & Wilson, K. G. (1999). Acceptance and commitment therapy: An experiential approach to behavior change. The Guilford Press.

- Hendricks, M. L., & Testa, R. J. (2012). A Conceptual Framework for Clinical Work with Transgender and Gender Nonconforming Clients: An Adaptation of the Minority Stress Model. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 43(5), 460–467.

- Holland, S. (1992). From social abuse to social action: A neighborhood psychotherapy and social action project for women. In J. Ussher & P. Nicholson (Eds.), Gender issues in clinical psychology (pp. 68–77). Routledge.

- Jackman, K., Edgar, B., Ling, A., Honig, J., & Bockting, W. (2018). Experiences of transmasculine spectrum people who report nonsuicidal self-injury: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 65(5), 586–597.

- Jensen, L. A., & Allen, M. N. (1996). Meta-synthesis of qualitative findings. Qualitative Health Research, 6(4), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239600600407

- Katz-Wise, S. L., Rosario, M., & Tsappis, M. (2016). Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth and family acceptance. Pediatric Clinics, 63(6), 1011–1025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcl.2016.07.005

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer Pub. Co.

- Lloyd, J., Chalklin, V., & Bond, F. W. (2019). Psychological processes underlying the impact of gender-related discrimination on psychological distress in transgender and gender nonconforming people. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 66(5), 550–563.

- Matsuno, E., & Israel, T. (2018). Psychological interventions promoting resilience among transgender individuals: Transgender resilience intervention model (TRIM). The Counseling Psychologist, 46(5), 632–655. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000018787261

- Matsuzaka, S. (2018). Alcoholics anonymous is a fellowship of people: A qualitative study. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 36(2), 152–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/07347324.2017.1420435

- McCann, E., & Brown, M. (2017). Discrimination and resilience and the needs of people who identify as transgender: A narrative review of quantitative research studies. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 26(23-24), 4080–4093. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13913

- McConnell, E. A., Janulis, P., Phillips, G., 2nd, Truong, R., & Birkett, M. (2018). Multiple minority stress and LGBT community resilience among sexual minority men. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 5(1), 1–12.

- McManus, F., Sacadura, C., & Clark, D. M. (2008). Why social anxiety persists: An experimental investigation of the role of safety behaviours as a maintaining factor. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 39(2), 147–161.

- McNeil, J., Bailey, L., Ellis, S., Morton, J., & Regan, M. (2012). Trans mental health study. Scottish Transgender Alliance. https://www.gires.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/trans_mh_study.pdf

- Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137286

- Meyer, I. H. (2015). Resilience in the study of minority stress and health of sexual and gender minorities. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(3), 209–213. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000132

- Miller, C. T., & Kaiser, C. R. (2001). A theoretical perspective on coping with stigma. Journal of Social Issues, 57(1), 73–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00202

- Mizock, L., Woodrum, T. D., Riley, J., Sotilleo, E. A., Yuen, N., & Ormerod, A. J. (2017). Coping with transphobia in employment: Strategies used by transgender and gender-diverse people in the United States. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 282–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1304313

- Paz Galupo, M. (2017). Researching while cisgender: Identity considerations for transgender research. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 241–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2017.1342503

- Reisner, S., Radix, A., & Deutsch, M. (2016). Integrated and gender-affirming transgender clinical care and research. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 72, 235–242.

- Riggle, E. D. B., Rostosky, S. S., McCants, L. E., & Pascale-Hague, D. (2011). The positive aspects of a transgender self-identification. Psychology and Sexuality, 2(2), 147–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2010.534490

- Santiago-Delefosse, M., Gavin, A., Bruchez, C., Roux, P., & Stephen, S. L. (2016). Quality of qualitative research in the health sciences: Analysis of the common criteria present in 58 assessment guidelines by expert users. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 148, 142–151.

- Scandurra, C., Vitelli, R., Maldonato, N. M., Valerio, P., & Bochicchio, V. (2019). A qualitative study on minority stress subjectively experienced by transgender and gender nonconforming people in Italy. Sexologies, 28(3), e61–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2019.05.002

- Schuller, T. (2007). Reflections on the use of social capital. Review of Social Economy, 65(1), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346760601132162

- Sevelius, J. M. (2013). Gender affirmation: A framework for conceptualizing risk behavior among transgender women of color. Sex Roles, 68(11–12), 675–689. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0216-5

- Shastri, P. C. (2013). Resilience: Building immunity in psychiatry. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 55(3), 224–234. https://doi.org/10.4103/0019-5545.117134

- Singh, A. A., Hays, D. G., & Watson, L. S. (2011). Strength in the face of adversity: Resilience strategies of transgender individuals. Journal of Counseling & Development, 89(1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6678.2011.tb00057.x

- Singh, A. A., & McKleroy, V. S. (2010). “Just getting out of bed is a revolutionary act”: The resilience of transgender people of color who have survived traumatic life events. Traumatology, 20, 1–11.

- Singh, A. A., Meng, S. E., & Hansen, A. W. (2014). “I am my own gender”: Resilience strategies of trans youth. Journal of Counseling & Development, 92(2), 208–218. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6676.2014.00150.x

- Talley, A. E., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2011). The moderator roles of coping style and identity disclosure in the relationship between perceived sexual stigma and psychological distress. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(12), 2883–2903. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00863.x

- Testa, R. J., Habarth, J., Peta, J., Balsam, K., & Bockting, W. (2015). Development of the gender minority stress and resilience measure. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 2(1), 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000081

- United Kingdom. Government Equalities Office. (2019). National LGBT Survey: Summary report. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/national-lgbt-survey-summary-report/national-lgbt-survey-summary-report#the-results

- Valentine, S. E., & Shipherd, J. C. (2018). A systematic review of social stress and mental health among transgender and gender non-conforming people in the United States. Clinical Psychology Review, 66, 24–38.

- van der Toorn, J., Pliskin, R., & Morgenroth, T. (2020). Not quite over the rainbow: The unrelenting and insidious nature of heteronormative ideology. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 34, 160–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.03.001

- Ward, D. J., Furber, C., Tierney, S., & Swallow, V. (2013). Using framework analysis in nursing research: A worked example. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 69(11), 2423–2431.

- Wells, A., Clark, D. M., Salkovskis, P., Ludgate, J., Hackmann, A., & Gelder, M. (1995). Social phobia: The role of in-situation safety behaviors in maintaining anxiety and negative beliefs. Behavior Therapy, 26(1), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80088-7

- Zimmer, L. (2006). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A question of dialoguing with texts. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 53(3), 311–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03721.x

- Zimmerman, M. A. (2000). Empowerment theory. In J. Rappaport & E. Seidman (Eds.), Handbook of community psychology (pp.43–63). Springer.