Abstract

Answering calls for an interactionist approach that would help clarify complex relationships among organizational socialization variables, this study applied a person-centered analytic approach aiming to examine the role of proximal socialization outcome profiles for distal outcomes. This approach is novel to organizational socialization research, contrasting the variable-centered approach dominating the field. Data from new police officers in Sweden (N = 430) were analyzed using latent profile analysis (LPA). Three proximal outcome profiles – a vulnerable (n = 151), a troublesome (n = 47), and a successful (n = 232) – were identified, with distinct patterns in the proximal outcome indicators role conflict, task mastery, and social integration. Complementary analysis showed subgroup differences in some antecedents and distal outcomes, which emphasized the role of personality and psychosocial working conditions. Thus, the findings show that proximal socialization outcome indicators may yield profiles characteristic of subgroups of newcomers who follow different socialization paths. Importantly, the findings show that a person-centered approach can add nuance to the understanding of how socialization processes differ among newcomers. While these results are promising, their generalizability to other professions and organizations remains to be investigated, which calls for continued person-centered research of organizational socialization processes.

Starting to work in an organization brings challenges. Learning and adjustment are central challenging processes that help newcomers make the transition from organizational outsiders to insiders (Bauer et al., Citation2007; Saks & Gruman, Citation2012). To become accepted and effective members, new employees have to take on new roles, norms, tasks, and people (Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007). When addressing such challenges newcomers typically experience uncertainty and ambiguity. In fact, newcomers often experience a “reality shock” when their prior expectations meet the actual working conditions (Saks & Ashforth, Citation2000). This experience can be particularly pronounced for newly graduated newcomers who begin a new professional career (Bauer & Erdogan, Citation2012), for instance for new police officers. Thus, enhancing learning and reducing uncertainty help newcomers feel confident and able to contribute to the new organization (Ashforth, Sluss, & Saks, Citation2007; Ellis et al., Citation2015).

In the research literature, the learning and adjustment process enabling new members to adapt to an organizational role is known as organizational socialization (e.g., Chao, Citation2012). In examining this process, it is common to distinguish between proximal and distal socialization outcomes (Kammeyer-Mueller & Wanberg, Citation2003; Saks et al., Citation2007; Saks & Ashforth, Citation1997). Proximal outcomes (or adjustment indicators) are assumed to reflect how well individuals adjust on their way to become organizational insiders, while distal outcomes reflect the ultimate organizational socialization outcomes (Bauer & Erdogan, Citation2011, Citation2012). This distinction helps to emphasize that organizational socialization is a process, where proximal outcomes precede distal outcomes, mediating effects of various organizational and individual socialization factors (also known as antecedents) that foster the socialization process (e.g., Saks & Ashforth, Citation1997). Some frequent proximal outcomes are role conflict, task mastery, and social integration. Accordingly, a large number of studies have shown relations between these indicators (or similar variables, e.g., role clarity or self-efficacy) and distal outcomes such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and job performance (Bauer et al., Citation2007; Saks et al., Citation2007).

Yet, it has been challenging to describe comprehensively how organizational socialization works since the process involves many factors and complex relationships. In response to this challenge, there have been repeated calls for an interactionist approach that may be helpful in describing the interplay between different factors (e.g., Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007; Klein & Heuser, Citation2008). One way to respond to this call is to apply a person-centered analytical approach, which focuses on the heterogeneity among subgroups of newcomers, instead of using a more traditional variable-centered approach that focuses on relationships between variables (cf. Howard & Hoffman, Citation2018; Morin et al., Citation2018). However, person-centered approaches have seldom been applied within organizational socialization research. To help further the understanding of the organizational socialization process, this study sets out to address this gap and apply a person-centered approach to examine the role of proximal outcome profiles for distal outcomes, to focus on the heterogeneity among subgroups of newcomers. More specifically, this study examines the role of proximal socialization outcome profiles, based on indicators of role conflict, task mastery and, social integration, for distal outcomes among new police officers in Sweden.

Organizational socialization theory

Research on organizational socialization has evolved for more than 50 years, with most studies published since the mid-1990s (Ashford & Nurmohamed, Citation2012; Bauer & Erdogan, Citation2014; Chao, Citation2012; Cooper-Thomas & Anderson, Citation2006; Saks & Gruman, Citation2018). Yet, there is no generally accepted theory that explains the content and process of organizational socialization (Chao, Citation2012). Rather, organizational socialization theory can be viewed as a broad theoretical framework, including numerous conceptual models that focus on similar processes, factors, and supporting theories (e.g., uncertainty reduction theory).

Successful organizational socialization can be described as a process where newcomers pass several stages. There is a number of stage-models, with most covering four overall stages of anticipation, encounter, adjustment, and stabilization (Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007). These stages have been linked to characteristic attitudes and behaviors of newcomers. The first stage, anticipation, occurs before organizational entrance, when individuals develop expectations about the organization. In the second stage, encounter, newcomers enter the organization and confront its realities, often experiencing a gap in relation to their prior expectations. In the third stage, adjustment, newcomers struggle to resolve core challenges and demands that they face in the organization. In the fourth and last stage, stabilization, individuals’ attitudes and actions indicate that the former newcomers have become organizational insiders. However, since the trajectories may take numerous paths, these stages only provide a rough heuristic of the socialization process (Ashforth, Citation2012).

Existing conceptual models typically focus on the main drivers behind successful organizational socialization. Overall, learning is considered central to socialization, in reducing newcomers’ uncertainty and enhancing relevant job knowledge (Ashforth, Sluss, & Saks, Citation2007). The main drivers behind the learning and adjustment process have been addressed as socialization factors (Saks & Ashforth, Citation1997), which include organizational and individual tactics (Chao, Citation2012; Ellis et al., Citation2015). Tactics are organizational (e.g., formal and informal) and individual actions (i.e., proactive behaviors), which help foster the learning and adjustment process. Besides socialization factors, conceptual models often include additional factors assumed relevant to newcomers’ socialization process, such as individual differences (e.g., personality and demographics; Fang et al., Citation2011; Gruman & Saks, Citation2011; Saks & Ashforth, Citation1997; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, Citation2000), and contextual factors (Ellis et al., Citation2015). Although findings suggest that psychosocial working conditions are important (e.g., Humphrey et al., Citation2007), such factors have seldom been examined in relation to organizational socialization (Saks & Gruman, Citation2012). Recently, however, the organizational socialization research has addressed working conditions, including job autonomy, feedback, and workload, as important resources (Saks & Gruman, Citation2018).

Adjustment indicators, including role conflict, task mastery, and social integration, are assumed to reflect core challenges and demands that follow organizational entry (Bauer et al., Citation2007; Saks et al., Citation2007). Thus, newcomers have to understand their job tasks and task priorities to avoid uncertainty (role conflict), gain confidence in performing their tasks and in their professional roles (task mastery), and become accepted by peers and integrated in the organization (social integration). Key indicators are typically associated, but still represent different constructs (Bauer & Erdogan, Citation2012). This suggests that proximal socialization outcomes may yield different adjustment profiles, characteristic for subgroups of newcomers.

Frequently studied distal outcomes, such as job satisfaction, organizational commitment, turnover intention, and job performance, focus on newcomers’ later actions and attitudes toward the organization (Chao, Citation2012). In focusing on work-related attitudes and behaviors important for retention and productivity, these common outcomes reflect the extent to which newcomers’ socialization matters to the organization (Bauer & Erdogan, Citation2012). Recently, however, there has been an interest in adding distal outcomes relating to what is best for the individuals, such as health and well-being (see Ellis et al., Citation2015; Saks & Gruman, Citation2018).

Person-centered approach

During the past decades the person-centered approach has received increasing attention within organizational research (Howard & Hoffman, Citation2018; Morin et al., Citation2018; Spurk et al., Citation2020; Wang & Hanges, Citation2011), for instance in organizational commitment research (Meyer et al., Citation2012). Contrasting the traditional variable-centered approach, which focuses on relationships between variables (e.g., regression analysis), a central aim of the person-centered approach is to study individuals as wholes, instead of separate variables (Collins & Lanza, Citation2010). Person-centered approaches include methods such as latent profile analysis (LPA) that identify latent groups of individuals who share similar patterns of relevant individual characteristics (Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Citation2018; Woo et al., Citation2018). Thus, assuming the existence of meaningful subgroups within a population, this approach relaxes the traditional assumption of all participants belonging to the same group. Importantly, variable-centered approaches, including for instance moderation analysis, which may clarify how variables interact, are less suitable for the study of complex interactions (Meyer & Morin, Citation2016). Instead, the person-centered analytical approach, which builds on a holistic interactionistic perspective that emphasizes the need to study individuals as a whole instead of single variables (e.g., Bergman et al., Citation2006), provides a viable alternative. Thus, applying a person-centered approach may provide new insights into the process of organizational socialization. Considering the central role of proximal outcomes in the research literature, examining the prevalence and relevance of characteristic patterns of key proximal socialization indicators for distal outcome variables, seems highly relevant.

Organizational socialization in the police

Within organizational socialization research, the early studies typically focused on single occupations, including the police (Cooper-Thomas & Anderson, Citation2005). Pioneering studies showed that police subculture had strong influence on newcomers (e.g., Skolnick, Citation1966; Van Maanen, Citation1975). Later, this view influenced the police literature in so that police subculture and police socialization were often used interchangeably (Britz, Citation1997). This line of research typically emphasizes the negative effects of police socialization (Moon, Citation2006; Terpstra & Schaap, Citation2013) and pays little attention to the role of individuals (Oberfield, Citation2012). Thus, police socialization research stands in contrast to the general literature on organizational socialization, which has instead turned toward a more individual-focused interactionist perspective, emphasizing organizational socialization as a process fostered by an interplay between newcomers and organizations (Bauer & Erdogan, Citation2012). Accordingly, this approach has not been widely adopted in police socialization research (for exceptions, see e.g., Alessandri et al., Citation2020; Moon, Citation2006; Terpstra & Schaap, Citation2013). Still, the police-specific studies may add important perspectives, when examining organizational socialization outcomes among new police officers.

Due to the characteristics of police work, stress and health among police personnel have attracted substantial research interest (e.g., Arble et al., Citation2018). New police officers generally start their careers in good health, which relates to pre-employment screening routines applied by police authorities (Waters & Ussery, Citation2007). However, after some years of duty, police officers frequently report mental and physical health problems (Gershon et al., Citation2009). Following this, numerous studies have examined the role of police officers’ psychosocial working conditions in relation to stress and health, emphasizing the importance of job demands, control, and support (e.g., Annell et al., Citation2018; Houdmont et al., Citation2012; Noblet et al., Citation2009). Findings suggest that organizational demands (e.g., work overload and poor management) are more important than operational demands (e.g., exposure to danger and dealing with victims) for stress and health (Stinchcomb, Citation2004; Waters & Ussery, Citation2007). Accordingly, the recent interest in health-related outcomes in organizational socialization research (Ellis et al., Citation2015) is highly relevant to police officers.

Regarding distal socialization outcomes, police officers tend to distrust their management and experience a lack of organizational support, while having more positive attitudes toward their immediate superiors and remain committed to their vocation (e.g., Chan & Doran, Citation2009; Johnson, Citation2012; Terpstra & Schaap, Citation2013). Still, trust in management is desirable. This suggests that trust toward the management may be a relevant distal outcome among new police officers.

Aim and research questions

The aim of this study was to add to the understanding of the organizational socialization process by examining the role of proximal outcome profiles for distal outcomes. We thus applied a person-centered approach in analyzing data from a sample of new police officers in Sweden, to clarify complex relationships among socialization indicators. Considering the lack of similar studies in organizational socialization research, we adopted an exploratory approach, in attempting to find proximal outcome profiles that are typical among police trainees. Accordingly, our first research question was:

Research question 1. Which profiles of key proximal socialization outcomes can be distinguished among police trainees and how prevalent are these profiles?

According to organizational socialization theory, proximal outcomes are assumed to mediate effects of socialization factors on distal outcomes. To explore the role of proximal outcomes in the socialization process, we first examined differences in demographics, individual characteristics, and psychosocial working conditions, assumed important for group membership, before examining group differences in distal work- and health-related outcomes. Thus, our second and third research questions were:

2. Research question 2. Which demographic characteristics, individual characteristics, and psychosocial working conditions describe police trainees with different socialization profiles?

3. Research question 3. Do socialization profiles differ with respect to distal work- and health-related outcomes?

Method

Setting

Sweden has one national police force. To become a police officer in Sweden, applicants have to pass an extensive admittance process and then complete the basic police-training program, with two years of academy training and six months of supervised field training. During field training, police trainees have a salaried temporary employment. After completing their basic training, new officers get employed as constables and typically work in operational duty.

In 2010, the field training following the two years of academy training was conducted at one of the 21 county police authorities. This was often the same authority which later employed the police trainee. Thus, field training served as an introduction to both the occupation and the local police authority.

Participants and procedure

This study uses data from the project Longitudinal validation of the Swedish police selection (Annell et al., Citation2018), which followed a cohort of new police officers from the application process (T0; spring 2008) until the end of their first work year (T2; end 2011). The cohort included 710 participants who, after fulfilling field-training during the fall 2010, were employed as constables by the Swedish Police and in active duty during the fall 2011. This study includes individuals (N = 430) who participated in two follow-up surveys: one near the end of their field training (T1; end of 2010; N = 523) and one near the end of their first work year as police officers (T2; end of 2011; N = 508). The mean age of this subsample at project start (2008) was 26 years (SD = 4), with 146 (34%) being women.

Data came from three consecutive time points: (1) the application process (T0; register data and background details); (2) the end of field training (T1; survey); (3) the end of first year as constables (T2; survey and supervisors’ performance ratings). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants during the application process. Ethical approval was obtained from the Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm (Ref. No. 2008/1268-31/5; 2010/232-31/5; 2017/1384-31).

Measures

This study includes five categories of variables: (1) indicators of proximal socialization outcomes (T1); (2) demographic characteristics (T0); (3) individual characteristics (T0); (4) psychosocial working conditions (T1); (5) distal socialization outcomes (T2). Unless specified, participants were asked to provide ratings along a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). presents descriptive statistics, correlations, and reliability estimates (mostly Cronbach’s alphas) for study variables. Reliability estimates were above .70, for all variables but four.

Table 1 Descriptives and correlations for all study variables (N = 430), including reliability estimates (in italics) in the diagonal.

Proximal socialization outcomes

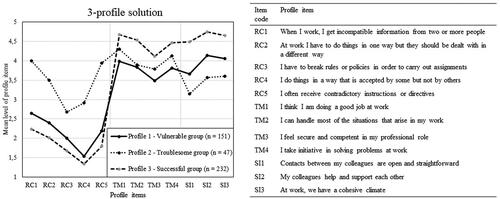

Indicators of proximal outcomes included five role conflict items (Rizzo et al., Citation1970), four task mastery items (Hall & Hall, Citation1976), and three social integration items (Falkenberg et al., Citation2015). These items are found in and in the Appendix.

Demographics

Four demographic variables were included: gender (0 = man, 1 = woman); age (2008; years), parental education level (0 = maximum upper secondary school, 1 = higher education); educational level (0 = upper secondary school, 1 = higher education less than three years, 2 = higher education three years or more).

Individual characteristics

Four individual characteristics, assessed during the application process, were included. General intelligence was measured by Uniq, a test developed to screen police applicants in Sweden (Lothigius & Sjöberg, Citation2004), which provides a composite score on a Stanine scale (Annell et al., Citation2014). Three personality dimensions – conscientiousness, emotional stability, and agreeableness – were assessed by Measuring Integrity (MINT), a personality-based integrity test (Sjöberg & Sjöberg, Citation2007), with 20 items per dimension and response alternatives ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 4 (strongly agree). Due to commercial copyright, no sample items are provided for Uniq and MINT.

Psychosocial working conditions

Four measures, covering aspects of job demands, control, and social support, assumed central during field-training were included. Workload, included to reflect organizational demands, was measured with three items (e.g., “I often have too much to do in my job”; Beehr et al., Citation1976; Hackman & Oldham, Citation1975) while emotional demands were included to reflect operational demands (Sundin et al., Citation2008). The emotional demands measure was adapted to the police setting, with four items regarding the frequency of facing emotionally demanding situations (e.g., death, suffering people, and fearing for one’s life), with response alternatives ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (daily). Job control was assessed with a scale of four items (e.g., “I can make my own decisions on how to organize my work”; Sverke & Sjöberg, Citation1994) based on a measure of job autonomy (Walsh et al., Citation1980). Feedback, included as key aspect of support to police trainees was measured with four items (e.g., “My supervisor and instructors give me a pretty good idea of how well I am performing my job”; Walsh et al., Citation1980).

Distal socialization outcomes

Five work-related (i.e., organizational commitment, job satisfaction, trust in management, intention to stay in the occupation, and job performance) and two health-related (subjective health complaints [SHC] and work-related anxiety) distal socialization outcomes were included. Organizational commitment was measured with a six-item scale adapted to the police setting and included affective and value-based components (e.g., “I would be very happy to spend the rest of my career within the Police”; Allen & Meyer, Citation1990; Cook & Wall, Citation1980; Guest & Dewe, Citation1991; Mowday et al., Citation1979). Job satisfaction was measured by three items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my job”; Brayfield & Rothe, Citation1951; Hellgren et al., Citation1997). Trust in management was assessed with a six-item scale (e.g., “I have complete confidence in my employer”; Robinson, Citation1996): Intention to stay was measured by three reverse coded items (e.g., “I am actively looking for a job outside the Police”; Cohen, Citation1998; Mobley et al., Citation1979) were included. Job performance was measured by supervisor-ratings of overall job performance, with ratings from 1 (well below average) to 10 (well above average). Subjective health complaints (Eriksen et al., Citation1998) included eight common health complaints (e.g., back-pain and fatigue) with their frequency during the first year of work being rated along a scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (daily). Work-related anxiety was measured using four items from a measure of job-induced tension (e.g., “I feel fidgety or nervous because of my job”; House & Rizzo, Citation1972).

Analyses

The original dataset (N = 430), had 175 cells (0.33%) with missing values. To avoid information loss by excluding 93 cases with incomplete data, imputation was performed through the expectation-maximization (EM) method (Little & Rubin, Citation1987) in SPSS 26. All variables were used as predictors in the equation. Due to lack of appropriate data, one cell without information regarding parental educational level was not imputed. To avoid information loss, this case was included in all analyses but the one including this variable.

Latent profile analysis (LPA) was performed in Mplus 8.4 (Muthén & Muthén, Citation1998–2017) to identify latent profiles among proximal socialization outcomes (research question 1). The twelve indicators (role conflict, task mastery, and social integration items) were included. Five models were estimated with one to five profiles each using an uncorrelated specification and maximum likelihood (ML). The models were evaluated by the following criteria (Nylund et al., Citation2007): (1) the sample-size adjusted Bayesian information criterion (SABIC; Sclove, Citation1987), (2) the bootstrapped likelihood ratio test (BLRT; McLachlan & Peel, Citation2000), (3) the profile membership distribution, and (4) the posterior probabilities associated with each profile. An optimal solution should have the lowest SABIC, the lowest significant BLRT, no groups with less than 5% of the respondents, and no posterior probabilities lower than .70 (Stanley et al., Citation2017). This was accompanied by tests for entropy (Celeux & Soromenho, Citation1996), where a proportion of 0.80 or higher suggests good classification (Clark & Muthén, Citation2009), but values of .76 have been found to be indicative of at least 90% correct assignment (Wang et al., Citation2017). To ensure stability, the best fitting solution was replicated (Geiser, Citation2013).

To examine profile distinctiveness, one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were performed to examine differences in mean scores of profile indicators, with profile membership as the independent variable. Additional analyses were conducted to examine the proximal socialization profiles in relation to the organizational socialization process. First, Chi-square tests (for categorical variables) and ANOVAs (for continuous variables) were performed to examine differences between profiles in demographics, individual characteristics, and psychosocial working conditions (research question 2). Additional ANOVAs were performed to examine differences between profiles and distal socialization outcomes (research question 3). With different sizes between profiles and Levene’s tests showing unequal group variances, Dunnett’s T3 test (p-level < .05), an adequate test for unequal variances (Rafter et al., Citation2002), was used for post-hoc comparisons. These analyses were performed in SPSS 26. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d (Cohen, Citation1988).

Results

presents results from the latent profile analysis comparing solutions up to five profiles. The 3-profile model had the lowest significant BLRT, while SABIC was lower, and entropy was higher for four or five profile solutions. However, both the 4-profile and 5-profile models included profiles with less than 5% of the respondents. Posterior probabilities (indicating the probability of an individual belonging to the assigned group) were high for all profiles, ranging from .85 to .94 (see ). Considering that entropy of .76 has been found to be indicative of at least 90% correct assignment, the value of .78 for the 3-profile was found satisfactory. Thus, the 3-profile solution was found as the best fitting model. Three successful replications supported the stability of the model.

Figure 1 Mean-level profiles for the 3-profile solution (N = 430). Profile items to the right.

Note: RC = Role conflict item. TM = Task mastery item. SI = Social integration item.

Table 2 Model fit statistics, profile membership, and posterior probabilities (N = 430).

Table 3 Posterior probabilities for the three-profile solution.

shows mean level profiles in the proximal socialization indicators for the three profiles. ANOVAs examining mean level differences for the 12 indicators showed significant mean level differences for all indicators. All post-hoc tests but one, regarding task mastery indicator 2 (item TM2; “I manage most of the situations that arise in my work”), were significant. Profile 1, a mid-sized group (n = 151; 35%), was characterized by rather low role conflict, the lowest task mastery, and moderate social integration. As for proximal socialization outcomes, this group was only partially successful. The lower task mastery indicates that this group struggled with lack of confidence in performing their work tasks and roles. This group was labeled the Vulnerable group. Profile 2, the smallest group (n = 47; 11%), was characterized by the highest role conflict, moderate task mastery, and the lowest social integration. Regarding socialization, this group was the least successful, foremost experiencing conflicting work role expectations and a less inclusive social climate. This profile was named the Troublesome group. Profile 3 was the largest group (n = 232; 54%) and had the lowest role conflict, the highest task mastery, and the highest social integration. This suggests that this group had the most successful socialization into the profession. Accordingly, this group was labeled the Successful group. Taken together, these findings answer the first research question, showing that it was possible to distinguish profiles of proximal socialization outcomes and their prevalence among police trainees.

presents results regarding the role of the proximal outcome profiles in the socialization process regarding the second research question. For demographics, there were no significant age differences between profiles. Chi-square tests showed no significant differences in gender, parental education, and education. Thus, there were no significant differences in demographics between groups with different socialization profiles.

Table 4 Profile means or frequencies of demographic characteristics, individual characteristic, psychosocial working conditions, and distal socialization outcomes variables, and statistical comparisons with ANOVA or Chi-square test (N = 430).

Analyses of individual characteristics showed no significant differences for intelligence. However, significant differences were found for all personality dimensions, with post-hoc tests revealing distinct group patterns. The Successful group had higher conscientiousness and emotional stability than the Vulnerable group, and higher emotional stability and agreeableness than the Troublesome group. In addition, the Vulnerable group had higher agreeableness levels than the Troublesome group. Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) ranged from small to medium, aside the difference in emotional stability between the successful and the problematic groups, which was large. These findings suggest that personality plays a role.

Analyses of psychosocial working conditions showed distinct patterns for all profiles for workload, job control, and feedback, while post hoc tests showed no significant differences in emotional demands, despite a significant F-test. The Successful group reported lower workload than the Troublesome group, and higher control and feedback than both the Troublesome and the Vulnerable groups. Further, the Vulnerable group reported lower workload, higher control, and feedback than the Troublesome group. Effect sizes were medium to large, with largest differences in control and feedback, between the Troublesome and the Successful groups. These findings suggest that there were important differences in psychosocial working conditions among the profiles.

As for the third research question, regarding differences in distal work- and health-related outcomes, significant differences were found for organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and trust in management while intention to stay and job performance were non-significant. For health-related outcomes, there was no significant difference in SHC, while a significant difference was found for work-related anxiety. Post-hoc tests revealed unique patterns between profiles for the four significant outcome variables. When compared to the Vulnerable and the Troublesome groups, the Successful group reported higher organizational commitment and job satisfaction, but lower work-related anxiety. Also, the Successful group reported higher trust in management than the Troublesome group. Moreover, the Vulnerable group reported lower work-related anxiety than the Troublesome group. All effect sizes ranged from small to moderate, with the largest differences between the Troublesome and the Successful groups. These differences in distal outcomes confirm the meaningfulness of the three profiles.

Discussion

In the organizational socialization literature, proximal outcomes are assumed to have a central role in the entry process of newcomers, in mediating effects of socialization factors on distal outcomes (e.g., Bauer et al., Citation2007; Saks & Ashforth, Citation1997). However, the complexity of the relationships between factors involved in the socialization process has been challenging to describe within the traditional variable-centered statistical approach (cf. Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007; Klein & Heuser, Citation2008). To address this, the present study employed a person-centered approach (cf. Meyer & Morin, Citation2016), in aiming to examine the role of proximal socialization outcome profiles for distal socialization outcomes among new police officers in Sweden. Specifically, occupationally relevant key proximal outcome indicators (role conflict, task mastery, and social integration) were analyzed using LPA to identify profiles sharing similar combinations of the proximal indicators.

The first research question addressed the number and prevalence of socialization profiles, while the second and third questions aimed to examine and validate the role of the identified profiles in the socialization process, by examining whether there were differences in relevant antecedents and distal outcomes. Regarding the first question, the LPA identified three profiles, with distinct proximal outcome patterns, near the end of six months of field training. These groups were labeled Vulnerable group (Profile 1), Troublesome group (Profile 2), and Successful group (Profile 3). The Successful group (54%) was the largest, showing a proximal outcome pattern with the lowest role conflict, highest task mastery, and highest social integration. The Vulnerable group (35%) was medium sized and had a pattern with rather low role conflict, the lowest task mastery, and rather high social integration, while the smallest, the Troublesome group (11%), had a pattern with the highest role conflict, medium task mastery, and the lowest social integration. These findings indicate that the socialization process was successful for most new police officers. Still, for a large proportion of officers (i.e., the Vulnerable and Troublesome groups), the proximal outcome profiles indicated a less favorable adjustment.

Notably, levels of role conflict and social integration appear to be coupled in all three groups (i.e., higher role conflict – lower social integration or vice versa), while task mastery seems to follow a diverse pattern, with the Troublesome group (with higher role conflict and lower social integration) had higher task mastery than the Vulnerable group (with lower role conflict and higher social integration). Identifying such complex patterns is a strength of the person-centered approach (cf. Meyer & Morin, Citation2016).

The differences in proximal outcome patterns suggest that the Troublesome (Profile 2) and the Vulnerable (Profile 1) groups struggled with somewhat different adjustment challenges. The Troublesome group appeared to primarily deal with challenges in understanding their professional role and in becoming socially integrated, while the Vulnerable group struggled to gain confidence in their task and role performance. Recent research suggests that proximal outcomes indicate how well individuals manage to gain resources to cope with the organizational challenges (Ellis et al., Citation2015). Thus, in terms of resources, our findings suggest that those in the Troublesome group mainly struggled to gain structural (e.g., role clarity and perceived fit) and relational resources (e.g., social acceptance), while the Vulnerable group struggled to gain personal resources (e.g., mastery beliefs).

The second research question addressed differences in demographics, individual characteristics, and psychosocial working conditions among socialization profiles, that is, in factors assumed important to the socialization process (cf. Saks & Ashforth, Citation1997; Saks & Gruman, Citation2018). Significant between-group differences were found in the personality dimensions conscientiousness, emotional stability, and agreeableness, and in psychosocial working conditions (workload, job control, and feedback). Indeed, this suggests that these variables are important for determining how proximal socialization outcomes may combine in forming distinct profiles. However, there were no differences in general intelligence, emotional demands, or demographics (gender, age, level of parental education, and educational level), which in turn suggests that these variables play a limited role for proximal outcome profiles.

Comparing the latent profiles with respect to personality and psychosocial working conditions, large effect sizes (Cohen, Citation1988) were observed for emotional stability (d = 1.06 between the Successful and the Troublesome group), control (d = 1.40 between the Successful and the Troublesome group), and feedback (d = 1.67 between the Successful and the Troublesome group; d = 0.88 between the Successful and the Vulnerable group), while effect sizes for conscientiousness, agreeableness and workload were small to medium sized. These findings underscore that psychosocial working conditions in terms of control and feedback are important socialization resources (cf. Saks & Gruman, Citation2012, Citation2018), and aligns with previous research showing that personality plays a role in fostering organizational socialization (Gruman & Saks, Citation2011; Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, Citation2000). In line with previous research (e.g., Miller et al., Citation2009; Saks & Ashforth, Citation2000), the magnitude of the effect sizes found here suggests that the differences in psychosocial working conditions were more characteristic of the different profiles, than the differences in personality. However, the current study only included three of the Big Five personality dimensions. In view of previous socialization research (cf. Wanberg & Kammeyer-Mueller, Citation2000), the dimensions not included (extraversion and openness), may have produced larger differences. Regardless, effect sizes for control and feedback were strikingly large when compared to the included personality dimensions.

In this study, we made use of personality measures from the application process. Since a favorable personality was a characteristic of newcomers in the Successful group, our findings support the importance of including personality in the selection process. Specifically, our findings suggest that emotional stability is key to help foster socialization among new police officers. Further, our findings suggest that lower agreeableness is coupled with difficulties in gaining structural and interpersonal resources (i.e., higher role conflict and lower social integration in the Troublesome group). Yet, recent research suggests that personality is more dynamic than previously assumed (e.g., Roberts et al., Citation2006), and research on police cadets (Alessandri et al., Citation2020) points to an interplay where personality fosters organizational socialization and organizational socialization fosters personality change during police training. Clearly, there are reasons to examine further the roles of psychosocial working conditions and personality in organizational socialization.

As for the third and final research question, findings showed significant differences between the Successful group (Profile 3) and the others in three out of seven distal outcome variables: organizational commitment, job satisfaction, and work-related anxiety. For these outcomes, comparisons with the Troublesome group (Profile 2) showed medium effect sizes (d = 0.50–0.60), while effect sizes were small in relation to the Vulnerable group (Profile 1; d = 0.26–0.33). Additionally, a small significant difference was observed between the Successful and the Troublesome groups in trust in management (d = 0.47). However, not only those in the Troublesome group, but all profiles had rather low trust levels (range: 2.21–2.67), a finding in line with previous research on police personnel (e.g., Terpstra & Schaap, Citation2013). Thus, our findings show that distal outcome patterns of the proximal socialization profiles mainly differ at a general level.

Somewhat surprisingly, there were no significant group differences in the distal outcomes intention to stay, job performance, and subjective health complaints. Possible explanations include low interrater reliability of supervisor-rated performance, which may suppress differences between socialization profiles (see Hunter & Schmidt, Citation2004). Also, within the time-frame studied here, strain from work-related anxiety may not have resulted in health impairments. Further, these distal outcomes may be primarily attributable to single explanatory factors rather than to the proximal socialization outcome profiles, which suggests that differences in distal outcome variables may be better explained within a variable-centered approach or by proximal outcome profiles including other indicators.

From an applied perspective, our findings suggest that organizations may benefit from taking on an interactionist perspective (cf. Bergman et al., Citation2006) and monitor proximal socialization outcome profiles, rather than single variables, to identify groups of newcomers with different needs. For instance, if field training supervisors identify police trainees who experience high role conflict and low social integration (i.e., Troublesome profile), then they may target interventions toward helping trainees to cope with the police role and to build a personal social network within the organization. If police trainees instead experience low role conflict combined with low task mastery (i.e., Vulnerable profile), then field training supervisors may provide further training and feedback opportunities to strengthen trainees’ confidence in their job performance. Thus, targeting the challenges and needs that characterize different groups of newcomers may help organizations to tailor their tactics to facilitate learning and adjustment among newcomers in so that they become accepted and effective organizational members (cf. Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007; Bauer et al., Citation2007; Saks & Gruman, Citation2012). In addition, organizations may benefit from monitoring newcomers’ experiences of their working climate and their personality, to identify needs and tailor appropriate organizational tactics for different groups of newcomers.

Methodological considerations

The strengths of this study include its longitudinal design, the rather large sample, and the use of an analytic approach that is novel to the field of organizational socialization. However, there are methodological limitations as well, for instance regarding the explorative approach; due to a lack of similar studies within the field, we applied an explorative approach in identifying proximal socialization profiles and investigating their associations with antecedents and distal outcomes. Yet, this approach limits generalizability of findings. Moreover, the fact that this study investigated organizational socialization, without including measures of organizational and individual tactics, is another limitation. However, no such measures were available in our data. Still, the data provided opportunity to focus on other factors considered important for organizational socialization, including demographics, individual characteristics, and psychosocial working conditions. We also had the possibility to examine a wide set of relevant distal outcomes, including health-related outcomes and trust in management. Thus, we were able to explore and validate our proximal outcome profiles, which is an important strength.

An additional methodological issue relates to timing. We made use of a previously collected data set including three time points. Thus, we had no possibility to change or add time points. Obviously, other time points may have yielded different results. Also, adding additional time points would have been valuable to examine closer the socialization process (e.g., during field training). For instance, the cross-sectional comparisons of profiles with psychosocial working conditions restrict conclusions regarding causality.

As for reliabilities, four measures had coefficients below .70. Three of these measures included psychosocial working conditions (i.e., workload, emotional demands, and control), and were based on established scales intended for use in working life. However, here, they were used during field training, which in this context involves a mix between education and work, with the trainees typically having less demanding tasks and limited autonomy. This may have resulted in lower reliabilities, and accordingly, in an underestimation of differences between profiles (see Hunter & Schmidt, Citation2004). The fourth measure was the distal outcome of job performance. The value of including an external outcome measure (i.e., based on supervisor ratings instead of self-ratings) made us include this measure, despite interrater reliabilities of such ratings typically being low, around .50 (see Annell et al., Citation2015; Viswesvaran et al., Citation1996). Obviously, this may have produced biased estimates when comparing the profiles. Although these reliability issues involve limitations, our explorative approach still justifies the decision to include the four measures, in adding overall value to the study.

The LPA is a powerful analytic tool to gain valuable insights regarding the role of subgroups in a sample, such as among newcomers in the process of organizational socialization. However, it has certain methodological challenges that are relevant to this study. There were no more than three socialization profiles, which is slightly fewer than expected since similar research often yields at least five groups (e.g., Meyer et al., Citation2012). There are different explanations behind the LPA challenges of this study. Importantly, the sample of new police officers was preselected and had a rather standardized introduction. This homogeneity may have supressed differences between subgroups, thereby making it more difficult to discriminate between groups – or even to identify more profiles. The sample size of 430 is in the range of what is commonly seen in similar studies (cf. Nylund-Gibson & Choi, Citation2018; Spurk et al., Citation2020). However, it may have been too small to detect additional subgroups. Further, we included three proximal socialization outcomes (cf. Bauer et al., Citation2007; Saks et al., Citation2007). Adding additional proximal outcomes (e.g., role clarity, cf. Bauer et al., Citation2007) would potentially have allowed identifying additional subgroups. Moreover, while the profile items that we used were based on established measures, it is still possible that their measurement properties were compromised in this particular setting. Thus, when planning to use a person-oriented approach, it is advisable to make an effort to include suitable indicators in identifying latent profiles. Despite these limitations, the exploratory approach with the analysis of data from a specific occupational group provides an addition to the field.

Conclusions

By using LPA, three distinct latent profiles, representing different patterns of proximal socialization outcomes, were identified in a sample of new police officers in Sweden – a vulnerable, a troublesome, and a successful. A majority of the new officers belonged to the Successful group, while the Troublesome group, who experienced a more demanding work situation and the worst distal outcome pattern, was the smallest. Further, our findings emphasize that both psychosocial working conditions and personality may be important antecedents of proximal socialization outcomes, which supports viewing organizational socialization as an interactive process including both organizational and individual factors (Ashforth, Citation2012; Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007; Klein & Heuser, Citation2008). The socialization profiles also had differential associations, in several cases, with the distal outcomes variables, where the patterns mainly differed on a general level. Taken together, the study findings show that the new police officers followed three main socialization paths.

More generally, this study has shown that proximal outcome indicators may form profiles that are characteristic for subgroups of newcomers following different paths. Depicting how the socialization process may differ among subgroups is a significant theoretical contribution to the literature that adds nuances to traditional stage models (cf. Ashforth, Sluss, & Harrison, Citation2007). From an applied perspective, identifying newcomers with different proximal outcome profiles may help organizations to tailor their tactics. From a methodological perspective, the study has demonstrated that a person-centered approach may help to gain understanding on how the socialization process may differ among subgroups of newcomers. However, even though the results are promising, it is important to remember the exploratory approach of this study. Thus, the generalizability to other occupations and countries remains to be examined. Therefore, we encourage researchers to apply a person-centred approach in further examining organizational socialization.

Declaration of interest statement

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Stefan Annell, upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alessandri, G., Perinelli, E., Robins, R. W., Vecchione, M., & Filosa, L. (2020). Personality trait change at work: Associations with organizational socialization and identification. Journal of Personality, 88(6), 1217–1218. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12567

- Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective, continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

- Annell, S., Lindfors, P., Kecklund, G., & Sverke, M. (2018). Sustainable recruitment: Individual characteristics and psychosocial working conditions among Swedish police officers. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 8(4), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.18291/njwls.v8i4.111926

- Annell, S., Lindfors, P., & Sverke, M. (2015). Police selection – Implications during training and early career. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 38(2), 221–238. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-11-2014-0119

- Annell, S., Sjöberg, A., & Sverke, M. (2014). Use and interpretation of test scores from limited cognitive test batteries: how g + Gc can equal g. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 55(5), 399–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12140

- Arble, E., Daugherty, A. M., & Arnetz, B. B. (2018). Models of first responder coping: Police officers as a unique population. Stress and Health, 34(5), 612–621. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2821

- Ashforth, B. E. (2012). The role of time in socialization dynamics. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 161–186). Oxford University Press.

- Ashford, S., & Nurmohamed, S. (2012). From past to present and into the future: A hitchhiker's guide to the socialization literature. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 8–24). Oxford University Press.

- Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., & Harrison, S. H. (2007). Socialization in organizational contexts. In G. P. Hodgkinson & J. K. Ford (Eds.), International review of industrial and organizational psychology 2007: Vol. 22 (pp. 1–70). John Wiley & Sons Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470753378.ch1

- Ashforth, B. E., Sluss, D. M., & Saks, A. M. (2007). Socialization tactics, proactive behavior, and newcomer learning: Integrating socialization models. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(3), 447–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2007.02.001

- Bauer, T. N., Bodner, T., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Tucker, J. S. (2007). Newcomer adjustment during organizational socialization: A meta-analytic review of antecedents, outcomes, and methods. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(3), 707–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.3.707

- Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2011). Organizational socialization: The effective onboarding of new employees. In S. Zedeck (Ed.), APA handbooks in psychology. APA handbook of industrial and organizational psychology, Vol. 3. Maintaining, expanding, and contracting the organization (pp. 51–64). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/12171-002

- Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2012). Organizational socialization outcomes: Now and into the future. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 97–112). Oxford University Press.

- Bauer, T. N., & Erdogan, B. (2014). Delineating and reviewing the role of newcomer capital in organizational socialization. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 1(1), 439–457. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091251

- Beehr, T. A., Walsh, J. T., & Taber, T. D. (1976). Relationship of stress to individually and organizationally valued states: Higher order needs as a moderator. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 61(7), 41–47. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.61.1.41

- Bergman, L. R., von Eye, A., & Magnusson, D. (2006). Person-oriented research strategies in developmental psychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (Eds.), Developmental psychopathology: Theory and method (pp. 850–888). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Brayfield, A. H., & Rothe, H. F. (1951). An index of job satisfaction. Journal of Applied Psychology, 35(5), 307–311. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0055617

- Britz, M. T. (1997). The police subculture and occupational socialization: Exploring individual and demographic characteristics. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 21(2), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02887446

- Celeux, G., & Soromenho, G. (1996). An entropy criterion for assessing the number of clusters in a mixture model. Journal of Classification, 13(2), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01246098

- Chan, J., & Doran, S. (2009). Staying in the job: Job satisfaction among mid-career police officers. Policing, 3(1), 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pan078

- Chao, G. T. (2012). Organizational socialization: Background, basics, and a blueprint for adjustment at work. In S. W. J. Kozlowski (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of organizational psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 579–614). Oxford University Press.

- Clark, S., Muthén, B. (2009). Relating latent class analysis results to variables not included in the analysis. Retrieved October 3, 2020, from http://www.statmodel.com/download/relatinglca.pdf

- Cohen, A. (1998). An examination of the relationship between work commitment and work outcomes among hospital nurses. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 14(1-2), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0956-5221(97)00033-X

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

- Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2010). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences. Wiley.

- Cook, J., & Wall, T. (1980). New work attitude measures of trust, organizational commitment and personal need non-fulfilment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 53(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1980.tb00005.x

- Cooper-Thomas, H. D., & Anderson, N. (2005). Organizational socialization: A field study into socialization success and rate. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 13(2), 116–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0965-075X.2005.00306.x

- Cooper-Thomas, H. D., & Anderson, N. (2006). Organizational socialization: A new theoretical model and recommendations for future research and HRM practices in organizations. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 21(5), 492–516. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940610673997

- Ellis, A. M., Bauer, T. N., Mansfield, L. R., Erdogan, B., Truxillo, D. M., & Simon, L. S. (2015). Navigating uncharted waters: Newcomer socialization through the lens of stress theory. Journal of Management, 41(1), 203–235. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314557525

- Eriksen, H. R., Svendsrød, R., Ursin, G., & Ursin, H. (1998). Prevalence of subjective health complaints in the Nordic European countries in 1993. The European Journal of Public Health, 8(4), 294–298. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/8.4.294

- Falkenberg, H., Näswall, K., Lindfors, P., & Sverke, M. (2015). Working in the same sector, in the same organization and in the same occupation: Similarities and differences between women and men physicians’ work climate and health complaints. Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 5(4), 67–84. https://doi.org/10.19154/njwls.v5i4.4844

- Fang, R., Duffy, M. K., & Shaw, J. D. (2011). The organizational socialization process: Review and development of a social capital model. Journal of Management, 37(1), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310384630

- Geiser, C. (2013). Data analysis with Mplus. Guilford Press.

- Gershon, R. R. M., Barocas, B., Canton, A. N., Xianbin Li, L., & Vlahov, D. (2009). Mental, physical, and behavioral outcomes associated with perceived work stress in police officers. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854808330015

- Gruman, J. A., & Saks, A. M. (2011). Performance management and employee engagement. Human Resource Management Review, 21(2), 123–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2010.09.004

- Guest, D. E., & Dewe, P. (1991). Company or trade union: Which wins workers' allegiance? A study of commitment in the UK electronics industry. British Journal of Industrial Relations, 29(1), 75–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.1991.tb00229.x

- Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1975). Development of the job diagnostic survey. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0076546

- Hall, D. T., & Hall, F. S. (1976). The relationship between goals, performance, success, self-image, and involvement under different organization climates. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 9(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(76)90055-5

- Hellgren, J., Sjöberg, A., & Sverke, M. (1997). Intention to quit: Effects of job satisfaction and job perceptions. In F. Avallone, J. Arnold, & K. de Witte (Eds.), Feelings work in Europe (pp. 415–423). Guerini.

- Houdmont, J., Kerr, R., & Randall, R. (2012). Organisational psychosocial hazard exposures in UK policing: Management standards indicator tool reference values. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 35(1), 182–197. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639511211215522

- House, R. H., & Rizzo, J. R. (1972). Role conflict and ambiguity as critical variables in a model of organizational behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 7(3), 467–505. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(72)90030-X

- Howard, M. C., & Hoffman, M. E. (2018). Variable-centered, person-centered, and person-specific approaches: Where theory meets the method. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 846–876. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117744021

- Humphrey, S. E., Nahrgang, J. D., & Morgeson, F. P. (2007). Integrating motivational, social, and contextual work design features: A meta-analytic summary and theoretical extension of the work design literature. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(5), 1332–1356. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.5.1332

- Hunter, J. E., & Schmidt, F. L. (2004). Methods of meta-analysis: Correcting error and bias in research findings (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Johnson, R. R. (2012). Police officer job satisfaction: A multidimensional analysis. Police Quarterly, 15(2), 157–176. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611112442809

- Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D., & Wanberg, C. R. (2003). Unwrapping the organizational entry process: Disentangling multiple antecedents and their pathways to adjustment. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 779–794. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.88.5.779

- Klein, H. J., & Heuser, A. E. (2008). The learning of socialization content: A framework for researching orientating practices. In J. J. Martocchio (Ed.), Research in personnel and human resources management (Vol. 27, pp. 279–336). Emerald Group Publishing Limited. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-7301(08)27007-6

- Little, R. J. A., & Rubin, D. B. (1987). Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley.

- Lothigius, J., & Sjöberg, A. (2004). UNIQ. Version 2.0 [Manual, in Swedish]. Psykologiförlaget AB.

- McLachlan, G., & Peel, D. (2000). Finite mixture models. Wiley.

- Meyer, J. P., & Morin, A. J. S. (2016). A person‐centered approach to commitment research: Theory, research, and methodology. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 37(4), 584–612. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2085

- Meyer, J. P., Stanley, L. J., & Parfyonova, N. M. (2012). Employee commitment in context: The nature and implication of commitment profiles. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.07.002

- Miller, H. A., Mire, S., & Kim, B. (2009). Predictors of job satisfaction among police officers: Does personality matter? Journal of Criminal Justice, 37(5), 419–426. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2009.07.001

- Mobley, W. H., Griffeth, R. W., Hand, H. H., & Meglino, B. M. (1979). Review and conceptual analysis of the employee turnover process. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 493–522. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.493

- Moon, B. (2006). The influence of organizational socialization on police officers' acceptance of community policing. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 29(4), 704–722. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510610711619

- Morin, A. J. S., Bujacz, A., & Gagné, M. (2018). Person-centered methodologies in the organizational sciences: Introduction to the feature topic. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428118773856

- Mowday, R. T., Steers, R. M., & Porter, L. W. (1979). The measurement of organizational commitment. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 14(2), 224–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/0001-8791(79)90072-1

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2017). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables (8th ed.). Muthén & Muthén.

- Noblet, A., Rodwell, J., & Allisey, A. (2009). Job stress in the law enforcement sector: Comparing the linear, non-linear and interaction effects of working conditions. Stress and Health, 25(1), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.1227

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Nylund-Gibson, K., & Choi, A. Y. (2018). Ten frequently asked questions about latent class analysis. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4(4), 440–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000176

- Oberfield, Z. W. (2012). Socialization and self-selection: How police officers develop their views about using force. Administration & Society, 44(6), 702–730. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095399711420545

- Rafter, J., Abell, M., & Braselton, J. (2002). Multiple comparison methods for means. SIAM Review, 44(2), 259–278. https://doi.org/10.1137/S0036144501357233

- Rizzo, J. R., House, R. J., & Lirtzman, S. I. (1970). Role conflict and ambiguity in complex organizations. Administrative Science Quarterly, 15(2), 150–163. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391486

- Roberts, B. W., Walton, K. E., & Viechtbauer, W. (2006). Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin, 132(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1

- Robinson, S. L. (1996). Trust and breach of the psychological contract. Administrative Science Quarterly, 41(4), 574–599. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393868

- Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. (1997). Organizational socialization: Making sense of the past and present as a prologue for the future. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 51(2), 234–279. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1997.1614

- Saks, A. M., & Ashforth, B. E. (2000). The role of dispositions, entry stressors, and behavioral plasticity theory in predicting newcomers’ adjustment to work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 21(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(200002)21:1<43::AID-JOB985>3.0.CO;2-W

- Saks, A. M., & Gruman, J. A. (2012). Getting newcomers on board: A review of socialization practices and introduction to socialization resources theory. In C. R. Wanberg (Ed.), Oxford library of psychology. The Oxford handbook of organizational socialization (pp. 27–55). Oxford University Press.

- Saks, A., & Gruman, J. A. (2018). Socialization resources theory and newcomers’ work engagement: A new pathway to newcomer socialization. Career Development International, 23(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.1108/CDI-12-2016-0214

- Saks, A. M., Uggerslev, K. L., & Fassina, N. E. (2007). Socialization tactics and newcomer adjustment: A meta-analytic review and test of a model. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 70(3), 413–446. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2006.12.004

- Sclove, S. L. (1987). Application of model-selection criteria to some problems in multivariate analysis. Psychometrika, 52(3), 333–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02294360

- Sjöberg, S., & Sjöberg, A. (2007). MINT Measuring integrity – Manual [Swedish version]. Assessio International.

- Skolnick, J. (1966). Justice without trial: Law enforcement in democratic society. Wiley.

- Spurk, D., Hirschi, A., Wang, M., Valero, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2020). Latent profile analysis: A review and “how to” guide of its application within vocational behavior research. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 120, 103445. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103445

- Stanley, L., Kellermanns, F. W., & Zellweger, T. M. (2017). Latent profile analysis: Understanding family firm profiles. Family Business Review, 30(1), 84–102. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486516677426

- Stinchcomb, J. B. (2004). Searching for stress in all the wrong places: Combating chronic organizational stressors in policing. Police Practice and Research, 5(3), 259–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/156142604200227594

- Sundin, L., Hochwälder, J., & Bildt, C. (2008). A scale for measuring specific job demands within the health care sector: Development and psychometric assessment. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 45(6), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2007.03.006

- Sverke, M., & Sjöberg, A. (1994). Dual commitment to company and union in Sweden: An examination of predictors and taxonomic split methods. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 15(4), 531–564. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X94154003

- Terpstra, J., & Schaap, D. (2013). Police culture, stress conditions and working styles. European Journal of Criminology, 10(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370812456343

- Van Maanen, J. (1975). Police organization: A longitudinal examination of job attitudes in an urban police department. Administrative Science Quarterly, 20(2), 207–228. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391695

- Viswesvaran, C., Ones, D. S., & Schmidt, F. L. (1996). Comparative analysis of the reliability of job performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(5), 557–574. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.81.5.557

- Walsh, J. T., Taber, T. D., & Beehr, T. A. (1980). An integrated model of perceived job characteristics. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 25(2), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/0030-5073(80)90066-5

- Wanberg, C. R., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. D. (2000). Predictors and outcomes of proactivity in the socialization process. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 85(3), 373–385. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.85.3.373

- Wang, M.-C., Deng, Q., Bi, X., Ye, H., & Yang, W. (2017). Performance of the entropy as an index of classification accuracy in latent profile analysis: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 49(11), 1473–1482. https://doi.org/10.3724/SP.J.1041.2017.01473

- Wang, M., & Hanges, P. J. (2011). Latent class procedures: Applications to organizational research. Organizational Research Methods, 14(1), 24–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110383988

- Waters, J. A., & Ussery, W. (2007). Police stress: History, contributing factors, symptoms, and interventions. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 30(2), 169–188. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639510710753199

- Woo, S. E., Jebb, A. T., Tay, L., & Parrigon, S. (2018). Putting the “person” in the center: Review and synthesis of person-centered approaches and methods in organizational science. Organizational Research Methods, 21(4), 814–845. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428117752467

Appendix

Table A1 Descriptives and correlations for the twelve profile items of role conflict, task mastery, and social integration (N = 430).