Abstract

Maternal substance misuse affects caregiving, which influences children’s coping skills. However, little is known about how children of mothers with substance misuse describe their coping in stressful situations. We studied coping and caregiver support among 29 children 4 years of age recruited from a children’s health clinic serving families with maternal substance misuse in Finland. Children completed a revised Attachment Story Completion Task that we examined with qualitative content analysis. We identified children’s experiences with coping in stressful situations with optimal and non-optimal caregiver support. Experiences with optimal caregiver support included (a) empathy, (b) solicitude, (c) intimacy, (d) reassurance, (e) being a role model, (f) concrete help, and (g) shared joy. Ones with non-optimal caregiver support included (a) punishment, (b) abandonment, (c) unresponsiveness, (d) physical aggression, (e) aggressive protection, and (f) parentification. Children’s strategies for coping without caregiver involvement were (a) magic, (b) avoidance, (c) inappropriate laughing, (d) self-reliance, or (e) a lack of strategy. Our findings highlight that preschool children of mothers with substance misuse employ various coping strategies in stressful situations that either include caregiver support or indicate non-optimal support. Children also tended to use maladaptive coping strategies when a caregiver was not involved. Understanding children’s coping with stress in families with maternal substance misuse is essential to supporting their socioemotional development and providing adequate interventions.

Introduction

Coping with stressful situations, an integral behavior in human life, requires individuals to manage and control their emotions, thoughts, actions, and physiological arousal and to act on environmental cues as a means to modify sources of stress (Compas et al., Citation2001). Among young children, coping is characterized by action regulation and effortful, goal-directed responses to stressors (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2007). For children, a sensitive and supportive caregiver–child relationship is considered to be a psychological resource for coping with stressful situations, with long-term consequences for children’s optimal cognitive and socioemotional development and mental health (McElwain et al., Citation2015). Children of mothers with substance misuse often experience insensitive caregiving as well as caregiver hostility and intrusiveness (Belt et al., Citation2012; Hatzis et al., Citation2017; Mansoor et al., Citation2012), and those experiences may hinder the development of their ability to cope in stressful situations. However, the ways in which children experience caregiver support under distress and how they cope with stressors with or without that support remain poorly understood from their own perspectives. In response, we examined with qualitative content analysis the experiences of 4-year-old children of mothers with substance misuse in order to clarify their coping strategies in stressful situations.

Stress experienced by vulnerable children of mothers with substance misuse

In addition to caregiving difficulties, maternal substance misuse is associated with a variety of psychosocial risks, including psychiatric problems and socioeconomic disadvantages (Kaltenbach, Citation2013), which create stressful, even toxic environments for children’s development. Such environments and early life stress can alter children’s stress reactivity by way of several biological mechanisms (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016). Moreover, these children may often experience challenges in their cognitive and socioemotional development (for review, see Huizink, Citation2015). Those environmental and developmental factors, together with the possible effects of prenatal substance exposure on children’s regulatory capacities (Beauchamp et al., Citation2020), may affect the abilities of children of mothers with substance misuse to cope with stressful situations.

Traditionally, early life stress has been associated with not only maladaptive coping strategies in children but also a lack of adaptive coping strategies in the face of stressful situations (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016). However, research has also acknowledged, on the one hand, that not all children employ maladaptive coping strategies during stressful life events and that some can even thrive despite adversity (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Citation2009), partly due to protective factors such as secure caregiver–child relationships (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Citation2009). On the other, adaptiveness in coping depends on the context as well as the outcome, and maladaptive coping may thus be conceptualized as functional adaptation (Wadsworth, Citation2015). For example, children of parents with substance misuse may cope with their parents’ hostility by avoiding conflicts; however, even if that strategy is adaptive in that specific context, it is likely to affect children’s capacities to cope with subsequent stressors and may predispose them to mental health problems and psychopathology. At the same time, the literature addressing vulnerable children’s coping strategies is currently incomplete, especially concerning children living with mothers with substance misuse, because most studies on children’s coping have been performed with samples of low-risk individuals.

Caregiving and coping with stress among young children

Beginning with symbiotic co-regulation with caregivers as infants, children’s coping develops into direct actions to seek help from and engage with caregivers during toddlerhood and preschool as a means to avoid stress (Wadsworth, Citation2015). However, because coping responses are shaped by context and can serve multiple demands (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2007), the literature indicates no consensus on how children’s coping should be categorized (Compas et al., Citation2001). In their comprehensive review, Skinner et al. (Citation2003) have suggested a hierarchical view on coping that differentiates lower- and higher-order categories of coping. Lower-order categories (i.e., coping strategies) refer to recognizable types of actions, such as avoidance, that describe conceptually clear, exhaustive, mutually exclusive categories (Skinner et al., Citation2003). By contrast, higher-order categories (i.e., families of coping) are multidimensional and consist of coping strategies clustered according to their adaptive functions (Skinner et al., Citation2003).

Of the dozen of core families of coping identified in research, support-seeking encompasses four coping strategies—contact-seeking, comfort-seeking, instrumental aid, and social referencing—with the adaptive function of using available social resources to cope with stress (Skinner et al., Citation2003; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2007). Support-seeking is recognized as one of the most common families of coping across all age groups, one that among preschoolers is directed toward caregivers (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2007). Caregiver–child relationships are thus essential in shaping preschool children’s adaptive ways of coping with stress (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016) and, as such, can be understood in light of attachment theory.

Attachment implies an affective bond between a child and a caregiver and, under most conditions, develops during the first year of life (Ainsworth, Citation1973; Bowlby, Citation1958). Children’s fundamental motivational need for relatedness with social partners results in attachment behavior, that is, seeking comfort and protection from caregivers in times of stress and exploring the environment during low-stress situations (Bowlby, Citation1973). Furthermore, caregiver’s responses and attunement to children’s needs, as well as the fit between the regulating dyad, underlie the development of children’s coping systems (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016). Theoretically, experiences with attachment figures prompt the construction of children’s internal representations, or internal working models (IWMs), about themselves, others, and the world that guide their future behavior in close relationships (Bowlby, Citation1973). Furthermore, IWMs of oneself (e.g., worthy or not worthy of care) and others (e.g., responding, not responding) have been suggested to extend into children’s capacities to cope with also other than attachment-related moderate stressors by preschool age (McElwain et al., Citation2015; Skinner & Edge, Citation2002). However, knowledge on how caregiver support shapes the development of preschool children’s coping remains limited.

Studying coping with children’s narratives

Representational and narrative methods, including the MacArthur Story Stem Battery (MSSB; Bretherton et al., Citation1990a) and the Attachment Story Completion Task (ASCT; Bretherton et al., Citation1990b), have been developed to assess attachment in children as young as 3 years old. Although narrative methods were initially developed to address children’s attachment-related representations, they have also been used to more extensively capture the characteristics of children’s inner worlds (Holmberg et al., Citation2007). In either case, narrative methods focus on meaning-making by way of language and representation while incorporating intra- and interpersonal perspectives (Oppenheim, Citation2006). In that way, the methods maintain that individuals construct meaning via internal representations but in dialogue with the social environment. Experiences in caregiver–child relationships, for example, thus shape children’s representations in a reciprocal way (Oppenheim, Citation2006).

For children with limited verbal capacity, narrative methods can serve as alternatives to self-report methods of reflecting and reporting on personal experiences (Oppenheim, Citation2006). Among vulnerable children whose language and pretend play skills may be delayed, narrative methods can capture reliable information starting from the age of 4 years (Holmberg et al., Citation2007). Such methods enable young children to express their thoughts and experiences with the social environment in age-appropriate ways, typically by using dolls and props in a functional but playful manner (Oppenheim, Citation2006). Children’s capacity to construct coherent narratives and understand the meanings of emotional events can influence their emotion regulation skills and further contribute to their socioemotional well-being (Thompson, Citation2016).

Studies involving the use of children’s story stem narratives have employed quantitative scoring systems that, despite their differences, generally include narrative coherence, thematic content—that is, themes that children create—and features of performance—or how stories are told (Holmberg et al., Citation2007; Oppenheim, Citation2006). Using those systems, sum scores of themes can be evaluated by quantitative means and by comparing the differences between different groups of children. When using quantitative scoring systems, more detailed aspects of children’s ways of coping with stressors may, however, be missed. As an alternative, children’s experiences expressed in narrative form can be qualitatively evaluated instead and, in turn, provide a deep understanding, description, and explanation of the phenomenon under study (Flick, Citation2018). In our context, the phenomenon of interest is vulnerable preschool children’s coping in stressful situations, which has yet to be qualitatively assessed save a few interview studies performed among school-aged children (e.g., Cheetham-Blake et al., Citation2019; Normann & Esbjørn, Citation2020; Sotardi, Citation2018). Beyond that, the literature contains no qualitative research conducted with preschool children and focused on their narratives.

The current study

The aim of our study was to explore children’s coping with everyday conflict situations as described by the 4-year-old children of mothers with substance misuse in story stem narratives. Adopting the view that emphasizes caregiver support as the optimal way for children to cope with stressful situations, we formulated two research questions:

What kind of experiences with caregiver support in coping with stressful situations do children of mothers with substance misuse describe?

What other coping strategies do those children describe?

Prioritizing the interpretation of the qualitative content of children’s narratives, our qualitative data-driven approach to analyzing children’s story stem narratives was expected to afford profound insights into the perspectives of children’s experiences with coping with stressors that are otherwise absent in the literature on families with substance misuse.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

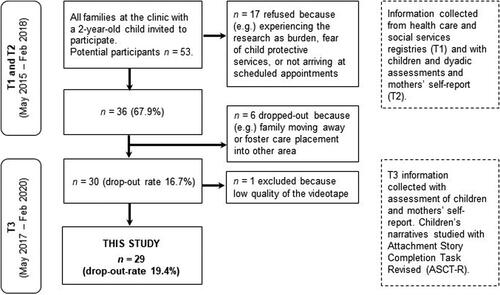

We used the dataset of a prospective study that followed children of mothers with substance misuse from 2 to 4 years of age and retrospectively collected information concerning pregnancy when the children were 2 years old. Participants of this study were 29 preschool children at 4 years of age (M = 49.2 months, SD = 1.8 months) recruited from a children’s health clinic in Southern Finland serving families with maternal substance misuse. Consecutive sampling was used, and all families at the clinic with a 2-year-old child at the time of data collection were invited to participate. Children living with biological and/or foster parent(s) were eligible for inclusion. The sample contained two pairs of siblings (see for the prospective study design, participant flow chart, and data used in this study).

Figure 1 Prospective study design of families with substance misuse, participant flow, and data used in this study. T1 = pregnancy and first two years of life (collected retrospectively), T2 = child 2 years of age, T3 = child 4 years of age.

Descriptive information of the participating children is presented in . All mothers (n = 28, because two children had the same mother) had a history of substance misuse, although use during each child’s lifetime varied considerably. Registry information revealed that, during their pregnancies, 18 of the mothers (64.3%) used medication (e.g., benzodiazepines or sertraline) and/or illegal substances (e.g., cannabis or amphetamines), two (7.1%) consumed alcohol only, and 15 (53.6%, n = 1 missing) smoked cigarettes. When the children were 4 years old, three of the mothers (10.7%, n = 6 missing) reported using either medication or illegal substances, seven (25.0%) reported drinking alcohol, and eight (28.6%, n = 2 missing) reported smoking cigarettes. In Finland, families with maternal substance misuse receive free, wide-ranging, long-term communal health care and social services. Family social work may often start at pregnancy and continue until the age of majority of 18 years. Depending on the family’s situation, services can include intensive support from social and family workers, home service, short- and long-term inpatient family treatment, outpatient treatment (including, for example, family therapy and mothers’ substance replacement therapy), and support person or support family. The development of children is followed in clinics specialized in women with problems on drugs, alcohol, and medication. Families represented by our sample had also used those services. During their lifetimes, most of the mothers (n = 26, 92.9%, n = 1 missing) had received treatment for either substance misuse—for example, intensive institutional care or opioid replacement therapy—or mental health, including psychotherapy or stay in a psychiatric unit. Twenty-five (89.3%) families had received family social work services, and 20 (71.4%, n = 2 missing) had been in inpatient family treatment.

Table 1 Descriptive information of participating children (n = 29).

Data were collected as part of the clinical work of two licensed psychologists. The first psychologist (Ph.D.) participated in designing the study and received training in using story stem narratives from the first author, who had a research reliability with a comparable method aimed at school-aged children, had clinical experience with the method for preschool-age children, and had permission to use the method from its developer. The second psychologist (Psy.M) participated in data collection after beginning to work at the clinic and received training from the other psychologist. Participation in the study was part of the families’ treatment, and all children had previously had contact with the psychologists. To conduct the study, each child was invited for a psychologist’s appointment as part of an individual assessment at the clinic, at the children’s day care center, or at the family’s home. The duration of the story stem narratives ranged from 16 to 37 min. Finally, data collection took place before the research questions of the current study were formulated.

Children’s narratives were assessed with the ASCT (Bretherton et al., Citation1990b). We used revised scripts (with permission from Timothy Page, Ph.D.; see ) that included seven narratives: five from the ASCT (i.e., “Spilled Juice,” “Hurt Knee,” “Monster,” “Departure,” and “Reunion”) and two high-intensity narratives that each depicted a strong conflict involving a parent or between parents (i.e., “Uncle Fred” and “Lost Keys”). Following the manual, we also provided an initial, warm-up narrative about a birthday party and a final, concluding narrative about family fun. The presentation of the narratives was standardized so that the interviewer began the narrative and asked the child to show and tell what they thought would happen next. To serve the clinical setting, we adapted the presentation of the stories so that more prompts could be given than in standard instructions in the case that the child had difficulties engaging in the task. Stories included mother and father figures, a younger sibling (i.e., Jane or Bob), and/or an older sibling (i.e., Susan or George) of the same gender as the participating child and with names translated into Finnish. A grandmother and/or a family dog were also included in some stories. All stories were video-recorded. During one child’s assessment, a technical problem occurred, and only the warm-up and first three stories were recorded (i.e., 7 min of recording). In another child’s assessment, a loud background noise drowned out the child’s narratives at times. The audible parts of those tapes were submitted for transcription and analysis.

Table A1 Stories from the attachment story completion task revised (ASCT-R) used in the study.

Videos were transcribed verbatim by two undergraduate students of psychology who were trained by the first author. We formed the dataset for the current qualitative content analysis according to the following procedure. First, we excluded warm-up and concluding stories, because they described non-stressful situations. Second, we excluded stories in which (a) the child’s voice on the tape was so unclear that the child’s narrative could not be understood even with the video, (b) the interviewer used prompting to the extent of influencing the content of the narrative so that it could not be interpreted to be the child’s own, and (c) the child’s narrative was too short (e.g., one word) and the story’s conclusion could not be understood. Last, we formed the dataset from the passages in which the child’s own narrative to the story stem could be discerned. At that stage, we decided to include both the manifest (i.e., transcribed texts) and latent content (i.e., performance features) in the analysis. Performance features encompassed children’s behavior on the video, such as silences, withdrawal, laughing, tone of voice, and children’s handling of the dolls. These features were expected to support the interpretation and understanding of some children’s narratives that were otherwise limited due to their language capacities or other qualities.

Data analysis

We examined the data with qualitative content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) using ATLAS.ti (version 8.4.22). We applied a conventional approach to content analysis because our aim was to describe a phenomenon—that is, vulnerable preschool children’s experiences with caregiver support and other coping strategies not involving caregivers in stressful situations—and derive understanding from the data (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005).

The first author read all of the transcripts and formed the dataset for content analysis following the aforementioned criteria. After defining the data, the first and second authors independently created themes and meaning units that emerged from children’s narratives. One narrative could provide more than one theme and meaning unit. The first author read the entire dataset and wrote reductions of children’s narratives in their own words. The first author included both the manifest and latent content in the analysis, such that the interpretation of the video was used in clustering the reductions and interpreted some narratives in which the child did not tell a story and/or expressed a solution with their behavior only (e.g., turned their back or left the room). The second author read 13 of the transcripts and used only the manifest content. Afterward, all three authors discussed the themes and meaning units that they had identified to generate a new understanding of the data. Next, the first author continued to cluster reductions of children’s narratives into new categories with shared meaning, and during the process, all authors reviewed and discussed the findings together several times. Last, the first author developed definitions of each category and subcategory that were reviewed and refined by the research team (see for an example of an audit trail).

Table A2 Audit Trail.

To improve the overall trustworthiness of the study, we followed a checklist that describes phases of preparing, organizing, and reporting content analysis (Elo et al., Citation2014). Furthermore, we evaluated the study’s trustworthiness by covering relevant items from the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ; Tong et al., Citation2007).

Ethical considerations

The study received ethical approval from regional University Hospital Ethics Committee. Informed consent to participate was obtained from legal caregivers or from social workers if the children were in foster care. During the assessment of story stems, only the child and psychologist were present, except in three cases in which the children wanted their caregivers to stay in the room. Due to the ethical permission, we report the results so that individual participants and families cannot be identified, and to protect participants’ anonymity, data extracts are identified only by the child’s gender, as shown in the children’s names in the narratives.

Results

We identified children’s experiences with optimal and non-optimal caregiver support used to cope with stressful situations. Those experiences were illustrated in narratives in which children described optimal or non-optimal exchanges between themselves and a caregiver or between caregivers in a way that aimed to support children in coping with everyday stressors. In the narratives, a caregiver denoted a parent, a sibling, the grandmother, or the family dog. We also identified children’s strategies of coping without caregiver involvement. All categories, subcategories, their descriptions, and examples of original data are presented in .

Table 2 Coping categories, subcategories, their descriptions, and examples of original data.

Children’s experiences with caregiver support

Experiences with optimal caregiver support included seven subcategories: (a) empathy, (b) solicitude, (c) intimacy, (d) reassurance, (e) being a role model, (f) concrete help, and (g) shared joy. By comparison, experiences with non-optimal caregiver support included six subcategories: (a) punishment, (b) abandonment, (c) unresponsiveness, (d) physical aggression, (e) aggressive protection, and (f) parentification.

Optimal caregiver support

Empathy was described in experiences in which the caregiver was empathetic toward the child’s pain. The caregiver ensured that the child received help or the caregiver’s empathetic approach helped, for example, to heal an injury, and thus guaranteed children’s coping with the situation.

Solicitude represented experiences in which caregivers provided attention to and nurtured children when they were scared, hurt, or separated from their parents. Caregiver’s solicitude was seen, for example, in the caregiver’s way of taking care of the child and being present for the child to help them to cope with stressful situations.

Intimacy captured the caregiver’s helping the child to cope by showing emotional proximity to the child or being available to receive the child’s expressions of intimacy. Those experiences included, for example, hugging, kissing, the child’s going to the caregiver’s lap, the caregiver’s carrying the child, or the child’s saying “I love you” or “I miss you” after a stressful situation.

Reassurance represented children’s experiences with a caregiver’s helping them to cope with their fear by reassuring them that there is nothing to be scared of (e.g., saying that a storm, not a monster, scared the child) or helping to expel the source of fear (e.g., by chasing a monster out of the child’s bedroom or playing a ghost that scared the monster away).

Being a role model was described in experiences in which the caregiver showed the child how to cope with a stressful situation—for example, by showing the child how to climb a rock that the child had previously fallen from. Those experiences also included exchanges between the caregivers only that served to solve the conflict in an adaptive way (e.g., when a father comforted a sad mother), which supported children’s coping in that situation.

Concrete help was seen in caregivers’ concrete actions—for example, by putting a band aid on the child’s hurt knee, taking the child to the hospital after an injury, cleaning spilled juice, or bringing new juice to replace the spilled one. Those actions focused on supporting the child in ways that allowed them to cope with mildly stressful situations.

Shared joy captured experiences in which children coped with separation from their parents by sharing fun and playful experiences with another caregiver (i.e., the grandmother). Those experiences included, for example, playing hide-and-seek, going to a fun park, or spending the night in a tent.

Non-optimal caregiver support

Experiences of punishment portrayed caregivers as mean and vengeful at times when the children needed support from them. Those experiences emerged in narratives in which the caregivers took the children to prison after an accident that the children caused or took revenge on the children for the accident. Punishment also included an experience with a caregiver’s bullying the children when she was supposed to take care of them.

Abandonment emerged in children’s experiences with being left alone by a caregiver (i.e., the grandmother), who was supposed to take care of the children after they were separated from their parents. In one narrative, the children died after being abandoned. Children were thus left alone to cope with the separation.

Unresponsiveness represented the caregiver’s unresponsive approach to the children’s distress and needs. Those experiences were illustrated in narratives in which the caregiver did not react when, for example, an accident or a scary event recurred, or else the child needed help in finding the parents’ lost keys.

Physical aggression involved experiences with the caregiver’s or the child’s pushing or hitting others in stressful situations. It also included an experience in which all of the family members got hurt because of the child’s aggression. Overall, those experiences involved aggressive ways of coping with distress in the family.

Aggressive protection was illustrated in narratives in which the caregiver protected the child from their fear, albeit in an aggressive or harsh way—for example, by killing the monster that the child was afraid of. Those narratives showed an inconsistency in children’s coping strategies encompassing both protection and aggression from the caregiver at the same time.

Last, parentification involved experiences with the caregiver’s taking the child’s role and the child’s acting as an adult in a role-reversed way as a means of coping with stressful situations. Those experiences included narratives of children’s solving or settling parents’ conflicts or taking care of and comforting a sad or sick parent.

Children’s coping without caregiver involvement

Children’s strategies of coping without caregiver involvement included five subcategories: (a) magic, (b) avoidance, (c) inappropriate laughing, and (d) self-reliance or else (e) a lack of strategy.

Magic was depicted in narratives in which children managed a stressful situation (i.e., spilled juice, being scared of a monster, or parent’s sadness) with a magic wand or by magically finding another adult to replace the one who had deceased. Magic helped children to survive in those situations without involving caregivers.

Avoidance was identified as children’s ways of escaping, hiding, vanishing, or turning their attention to something else, including playing tricks with the dog doll, during a stressful situation. That coping strategy captured children’s passive ways of coping with emotion-evoking situations.

Inappropriate laughing represented children’s way of coping with an inappropriate emotional reaction—that is, laughing—in stressful situations, including when facing the everyday accident of spilling juice or experiencing parent’s sadness. Those narratives illustrated children’s difficulties in expressing appropriate emotional reactions when distressed and, in one narrative, was associated with a parent’s death.

Self-reliance described children’s way of coping with stressful situations by relying on themselves. That strategy occurred in narratives in which the participating child solved the problem by involving themselves in the story instead of by using a doll—for example, by pretending to wipe spilled juice from the floor or saying that there was no monster and putting the child doll to bed.

Last, a lack of strategy illustrated children’s difficulties with telling a coherent narrative about how to cope with a stressful situation. Such behavior was observed, for example, in children’s inability or unwillingness to tell the story or their anxious, withdrawn behavior during the story stem assessment.

Support from different caregivers and types of coping

Children expressed receiving different kinds of support from different caregivers. Solicitude, intimacy, and reassurance were received from all caregivers (i.e., parents, the grandmother, a sibling, and the family dog). By contrast, empathy was experienced with the father and the grandmother only. Parents, the siblings, and the family dog were seen as role models and provided concrete help to children in coping with stress. Last, shared joy was experienced only with the grandmother. Among forms of non-optimal support, punishment was received from parents and the grandmother, whereas experiences with abandonment related to the grandmother only. All caregivers were described as being unresponsive, and physical aggression was identified as stemming from parents and the grandmother in addition to the children themselves. Experiences with aggressive protection were described with the father and the family dog. Last, parentification related only to experiences with role-reversal with the parents.

Some of the children’s coping strategies were identified only in certain types of stressful events. Receiving caregiver support via empathy was associated with children’s injuries, while caregiver’s reassurance was present only when the child was scared. Children’s fear also elicited caregiver’s aggressive protection. Caregiver’s concrete help was seen only in mildly stressful situations (i.e., spilling juice or hurting a knee), and, interestingly, some children showed no coping strategy in those situations. Parentification and avoidance were evoked only by highly stressful situations (i.e., parents’ conflict or the death of an uncle). Last, certain types of coping tended to co-occur; concrete help typically concurred with intimacy and physical aggression with inappropriate laughing.

Discussion

Despite a lack of consensus on how children’s coping should be understood, caregiver support has been recognized as an important factor in shaping and characterizing its development (Compas et al., Citation2001; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016). Research on coping among vulnerable children of mothers with substance misuse is, however, missing from the literature, and we addressed that gap in our study. In particular, we assessed 4-year-old children’s experiences with caregiver support in coping with stressful situations and what other coping strategies they described. By conducting a qualitative content analysis of the preschool children’s narratives, we identified seven experiences with optimal caregiver support and six experiences with non-optimal support in coping with stressful situations. Moreover, five strategies of coping without caregiver involvement were identified.

Optimal caregiver support was observed in children’s experiences with caregivers’ (a) empathy, (b) solicitude, (c) intimacy, (d) reassurance, (e) being a role model, (f) concrete help, and (g) shared joy. Our findings comply with the hierarchical view of coping and identify children’s experiences as conceptually clear and mutually exclusive coping strategies—that is, encompassing contact-seeking, comfort-seeking, and instrumental aid—that could be classified in the support-seeking family of coping (Skinner et al., Citation2003; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2007). More precisely, those experiences describe children’s adaptive ways of coping with stress with the help of caregivers (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Citation2009), which is noteworthy considering the vulnerability of our sample. It should be noted that experiences with empathy and concrete help were identified only in mildly stressful situations that were not as likely to activate children’s attachment behavior. Nevertheless, children employed caregiver support in coping with mild stressors. As suggested by previous literature (McElwain et al., Citation2015; Skinner & Edge, Citation2002), those results may indicate that earlier experiences with caregivers guide children’s coping with also other than attachment-related stressors.

Non-optimal caregiver support in coping was identified in children’s experiences with (a) punishment, (b) abandonment, (c) unresponsiveness, (d) physical aggression, (e) aggressive protection, and (f) parentification. Caregivers were thus represented as unable to adequately respond to children’s support-seeking behavior in stressful situations. Similar experiences have been related to difficulties with caregiver–child interaction in families with substance misuse (e.g., Hatzis et al., Citation2017) and may indicate a caregiver’s unavailability, inconsistency, and even disorganized, disoriented parenting that often underlie children’s insecure attachment (Main & Solomon, Citation1986; Out et al., Citation2009). Previous studies have frequently revealed associations between physical aggression and role-reversal (i.e., parentification in our study) with children’s insecure or disorganized attachment (Macfie et al., Citation2008; Savage, Citation2014) that often appears to be prevalent among vulnerable children (Cyr et al., Citation2010). This can potentially impair children’s coping skills by creating a mismatch in the regulating dyad (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016). Moreover, the effects of prenatal substance exposure on children’s impaired regulation capacities (Beauchamp et al., Citation2020) and reduced cognitive skills characterizing many children in our study, could increase children’s vulnerability to major life stressors, thereby predisposing the individual to later psychopathology (Kobak & Bosmans, Citation2019). Those findings point to extensive vulnerabilities among the preschool children of mothers with substance misuse in our study.

Our findings also indicate that the vulnerable children commonly used strategies for coping with distress without caregiver involvement. Those strategies included (a) magic, (b) avoidance, (c) inappropriate laughing, and (d) self-reliance or else (e) a lack of strategy. All of those strategies could be understood as functional adaptations that helped the children to cope in specific situations but are likely to be harmful and maladaptive in the long run (Wadsworth, Citation2015). An exception was the final category, the lack of any strategy whatsoever, that captured children’s overall difficulties with and reluctance in constructing a narrative and finding a strategy to cope, which may have been influenced by their lowered language skills. However, this may also indicate incoherence in their internal representations and difficulties with understanding emotional events (Kerns, Citation2013). In general, when caregivers are not a source of comfort, children learn to rely on themselves to cope with stressors and are likely to develop insecure attachment relationships as a result (Schechter et al., Citation2007; Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016). Therefore, the findings also suggest that when coping by themselves, children were compelled to regulate their stress by means other than support-seeking behavior. That dynamic is consistent with other studies’ findings showcasing how, in addition to support-seeking, preschool children primarily use withdrawal, distraction, and direct action when confronting stressors (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2007). Interestingly, avoidance has been recognized as a demobilizing coping strategy that aims to limit attention from caregivers and may be observed in frightening family environments (Davies & Martin, Citation2014). Beyond that, the coping strategies of magic and inappropriate emotional expression (i.e., inappropriate laughing in our study) that are often associated with children’s disorganized attachment narratives (Duschinsky, Citation2020; Kerns, Citation2013) could also indicate those children’s stressful, even toxic family environments.

In addition to parents, also the grandmother, the siblings, and the family dog were often represented as caregivers who provided both optimal and non-optimal support in coping with stress. The active involvement of all family members could partly be elicited by the story stems that introduced those characters into the stories. However, children in our study, as well as their mothers, were characterized by having already received numerous health care and social services by the time the children were of preschool age, which could suggest vulnerabilities related to the caregiving environment of those families. It is thus possible that support received from caregivers other than parents served as a protective factor for children who may have experienced toxic stress related to mothers’ substance misuse in their early lives (Cicchetti & Rogosch, Citation2009). This finding also accords with studies identifying grandparents as important in supporting children’s coping and well-being when parents misuse substances (e.g., Peterson Lent & Otto, Citation2018; Sheridan et al., Citation2011). More than a third of the children in our study were also living with either their grandparents or foster parents, which may further help to explain why some children relied on caregivers other than their parents in coping with stressful situations.

Trustworthiness

We utilized two distinct checklists—one for content analysis (Elo et al., Citation2014), the other for qualitative studies (COREQ; Tong et al., Citation2007)—to scrutinize the trustworthiness of the qualitative content analysis at every stage. According to Elo et al. (Citation2014), our approach to content analysis was conventional. We used a preexisting dataset that, despite imposing limitations, contained systematically collected data with the potential to be analyzed. Important questions related to trustworthiness were, first, how much the narrative story stem method guided our results by producing certain types of narratives. For example, it is likely that, with free play, children would have told different narratives. The method has, however, been recognized as a valuable, age-appropriate tool for understanding children’s representations and inner worlds more extensively, especially regarding attachment-related experiences and conflict resolution (Holmberg et al., Citation2007). We prioritized the transferability of results by describing the data, sampling method, and participants in a detailed manner and by showing an example of an audit trail (see ) of how categories were derived from the original data.

Second, the context of our sample influenced our interpretation of the results. To illustrate its influence, we have highlighted the complex caregiving environments of the children (e.g., variations in maternal substance misuse, children’s health care histories, and place of residence) in as much detail as respect for the participants’ anonymity allows. Moreover, we have factored in the health care and social services systems available to families with substance misuse in Finland, which greatly differ from those of many other countries.

Last, researcher bias may have influenced our findings, primarily because the first author had been in clinical contact with some of the participating families. Such contact could have affected the interpretation of the children’s narratives but also likely afforded a deeper understanding of their experiences. To minimize that potential bias, two researchers were involved in creating the categories and meaning units that emerged from the children’s narratives. In analyzing the results, we used not only the text but also the video in order to acquire a full understanding of children’s experiences that were sometimes better illustrated by their play than their verbal descriptions. All authors discussed the developed categories, confirmed that no overlap existed, and, whenever necessary, consulted the original data to elaborate the findings. Deviating from the COREQ (Tong et al., Citation2007), we did not have field notes for our data because data collection was part of clinical work. Returning transcripts to participants and having them check the findings were also not applicable in our study.

Strengths and limitations

The study’s first limitation was the preexisting data collected with ASCT that guided our research questions and may have ruled out other important aims for the study. Nevertheless, the research questions responded to a clear research gap in the literature on coping among vulnerable preschool children of mothers with substance misuse. A second limitation was that mothers’ substance misuse when the children were 4 years old was measured with self-report only, and many answers were missing. That limitation hampered a clear understanding of characteristics of the mothers’ substance misuse at the time of the study. However, substance use disorders are often chronic problems that tend to show frequent relapses over time, which suggests that the severe use during pregnancy that was better documented was likely to indicate later substance use problems. Third, because we used qualitative content analysis that differed from the traditional analytical methods of children’s narratives, our results cannot be generalized to other groups or populations of children of mothers with substance misuse beyond our sample. It is also noteworthy that the narrative method allowed us to explore children’s representations that cannot be interpreted as their actual experiences. Nevertheless, the qualitative approach permitted us to form understandings and interpret the meanings of the experiences of vulnerable young children in a naturalistic setting more deeply than traditional analysis methods allow.

Clinical implications and directions for future research

Our results highlight that preschool children of mothers with substance misuse employ various coping strategies that involve caregivers. Because caregiving requires coping with stress, which is often challenging among parents with substance misuse (Rutherford & Mayes, Citation2019), our study suggests that it is important in clinical work to support the caregiving provided by parents with substance misuse, including their sensitivity and reflective functioning, with interventions starting at pregnancy. For example, attachment-based interventions aimed at families with substance misuse (e.g., Attachment and Biobehavioral Catch-up; Bick et al., Citation2013; Mothering from the Inside Out; Suchman et al., Citation2017), have been found to support parental sensitivity and reflective functioning, as well as children’s attachment security and regulatory capacities. In addition, it is crucial to teach different coping strategies to children—for example, through interventions based on cognitive–behavioral therapy (e.g., Ruocco et al., Citation2018), because vulnerable children may need a more extensive repertoire of coping skills than children at lower risk when facing with even mild stressors (Wadsworth, Citation2015).

Our findings indicate several directions for future research. First, the ways in which non-optimal or lacking caregiver support in coping are associated with vulnerable children’s later socioemotional development need clarification. More generally, our findings bring out important questions about what factors may explain differences in children’s coping strategies, which could be answered with quantitative study designs. Second, our data-driven approach supported the hierarchical view of coping in finding different coping strategies that describe preschool children’s support-seeking coping behavior. The results can thus benefit future studies seeking to advance the coping hierarchy and formulate coping categories for vulnerable children. Last, despite the children’s high-risk environment, our findings of numerous adaptive coping strategies potentially indicate the plasticity of the brain and the importance of protective factors in shaping children’s ways of coping (Skinner & Zimmer-Gembeck, Citation2016). Future studies should therefore identify which factors protect against the maladaptive development of vulnerable children’s coping skills.

Conclusion

Our study highlighted that preschool children of mothers with substance misuse experience both caregiver support and non-optimal support when coping with everyday stressors. When caregivers were not involved, those children coped by themselves, often in maladaptive ways. Caregivers’ function to adjust the level of stress for children so that they can learn adaptive coping strategies is essential, because children’s coping is known to affect their socioemotional development and later psychopathology. Based on our results, interventions should therefore target both caregiving and children’s coping strategies to support vulnerable children’s well-being.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank the families who participated in this research for their valuable time and efforts. This work was supported by a fund from the Finnish Cultural Foundation to the first author and by the university faculty of the first author.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability

Research data are not shared due to ethical reasons and for confidentiality of the research participants.

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1973). The development of infant-mother attachment. In Review of child development research (3rd ed., pp. 1–94). University of Chicago Press.

- Beauchamp, K. G., Lowe, J., Schrader, R. M., Shrestha, S., Aragón, C., Moss, N., Stephen, J. M., & Bakhireva, L. N. (2020). Self-regulation and emotional reactivity in infants with prenatal exposure to opioids and alcohol. Early Human Development, 148, 105119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2020.105119

- Belt, R. H., Flykt, M., Punamäki, R. L., Pajulo, M., Posa, T., & Tamminen, T. (2012). Psychotherapy groups and individual support to enhance mental health and early dyadic interaction among drug-abusing mothers. Infant Mental Health Journal, 33(5), 520–534. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21348

- Bick, J., Bernard, K., & Dozier, M. (2013). Attachment and biobehavioral catch-up: An attachment-based intervention for substance using mothers and their infants. In N. E. Suchman, M. Pajulo, & L. C. Mayes (Eds.), Parenting and substance abuse: Developmental approaches to intervention (pp. 303–320). Oxford University Press.

- Bowlby, J. (1958). The nature of the child’s tie to his mother. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 39(5), 350–373.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Vol. 2. Separation: Anxiety and anger. Basic Books.

- Bretherton, I., Oppenheim, D., Buchsbaum, H., & Emde, R. (1990a). MacArthur story stem battery [Unpublished Manual]. University of Wisconsin-Madison.

- Bretherton, I., Ridgeway, D., & Cassidy, J. (1990b). Assessing internal working models of the attachment relationships: An attachment story completion task for 3-year-olds. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years (pp. 273–308). University of Chicago Press.

- Cheetham-Blake, T. J., Family, H. E., & Turner-Cobb, J. M. (2019). ‘Every day I worry about something’: A qualitative exploration of children's experiences of stress and coping. British Journal of Health Psychology, 24(4), 931–952. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12387

- Cicchetti, D., & Rogosch, F. A. (2009). Adaptive coping under conditions of extreme stress: Multilevel influences on the determinants of resilience in maltreated children. In E. A. Skinner & M. J. Zimmer-Gembeck (Eds.), Coping and the development of regulation. New directions for child and adolescent development (pp. 47–59). Jossey-Bass. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.242

- Compas, B. E., Connor-Smith, J. K., Saltzman, H., Thomsen, A. H., & Wadsworth, M. E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127(1), 87–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.87

- Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990289

- Davies, P., & Martin, M. (2014). Children’s coping and adjustment in high-conflict homes: The reformulation of emotional security theory. Child Development Perspectives, 8(4), 242–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12094

- Duschinsky, R. (2020). Cornerstones of attachment research. Oxford University Press.

- Elo, S., Kääriäinen, M., Kanste, O., Pölkki, T., Utriainen, K., & Kyngäs, H. (2014). Qualitative content analysis: A focus on trustworthiness. SAGE Open, 4(1), 215824401452263–215824401452210. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244014522633

- Flick, U. (2018). Doing qualitative data collection – Charting the routes. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Data Collection (pp. 3–16). SAGE Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526416070

- Hatzis, D., Dawe, S., Harnett, P., & Barlow, J. (2017). Quality of caregiving in mothers with illicit substance use: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Substance Abuse : Research and Treatment, 11, 1178221817694038–1178221817694015. https://doi.org/10.1177/1178221817694038

- Holmberg, J., Robinson, J., Corbitt-Price, J., & Wiener, P. (2007). Using narratives to assess competencies and risks in young children: Experiences with high risk and normal populations. Infant Mental Health Journal, 28(6), 647–666. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.20158

- Hsieh, H. F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Huizink, A. C. (2015). Prenatal maternal substance use and offspring outcomes: overview of recent findings and possible interventions. In European Psychologist (Vol. 20, pp. 90–101). Hogrefe Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000197

- Kaltenbach, K. (2013). Bio-psychosocial characteristics of parenting women with substance use disorder. In N. E. Suchman, M. Pajulo, & L. C. Mayes (Eds.), Parenting and substance abuse: Developmental approaches to intervention (pp. 185–194). Oxford University Press.

- Kerns, K. A. (2013). Story stem procedures for assessing attachment representations in late middle childhood [Unpublished manual]. Kent State University.

- Kobak, R., & Bosmans, G. (2019). Attachment and psychopathology: A dynamic model of the insecure cycle. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 76–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.018

- Macfie, J., Fitzpatrick, K. L., Rivas, E. M., & Cox, M. J. (2008). Independent influences upon mother-toddler role reversal: Infant-mother attachment disorganization and role reversal in mother's childhood. Attachment & Human Development, 10(1), 29–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730701868589

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of a new, insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In M. Yogman & T. B. Brazelton (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95–124). Ablex.

- Mansoor, E., Morrow, C. E., Accornero, V. H., Xue, L., Johnson, A. L., Anthony, J. C., & Bandstra, E. S. (2012). Longitudinal effects of prenatal cocaine use on mother-child interactions at ages 3 and 5 years. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 33(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e31823968ab

- McElwain, N. L., Holland, A. S., Engle, J. M., Wong, M. S., & Emery, H. T. (2015). Child–mother attachment security and child characteristics as joint contributors to young children’s coping in a challenging situation. Infant and Child Development, 24(4), 414–434. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1886

- Normann, N., & Esbjørn, B. H. (2020). How do anxious children attempt to regulate worry? Results from a qualitative study with an experimental manipulation. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 93(2), 207–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12210

- Oppenheim, D. (2006). Child, parent, and parent-child emotion narratives: Implications for developmental psychopathology. Development and Psychopathology, 18(3), 771–790. https://doi.org/10.1017/s095457940606038x

- Out, D., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2009). The role of disconnected and extremely insensitive parenting in the development of disorganized attachment: Validation of a new measure. Attachment & Human Development, 11(5), 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730903132289

- Page, T. F. (2001). Attachment themes in the family narratives of preschool children: A qualitative analysis. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 18(5), 353–375. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1012555323631

- Peterson Lent, J., & Otto, A. (2018). Grandparents, grandchildren, and caregiving: The impacts of America’s substance use crisis. Generations, 42(3), 15–22.

- Ruocco, S., Freeman, N. C., & McLean, L. A. (2018). Learning to cope: A CBT evaluation exploring self-reported changes in coping with anxiety among school children aged 5–7 years. The Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 35(2), 67–87. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2018.8

- Rutherford, H. J. V., & Mayes, L. C. (2019). Parenting stress: A novel mechanism of addiction vulnerability. Neurobiology of Stress, 11, 100172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100172

- Savage, J. (2014). The association between attachment, parental bonds and physically aggressive and violent behavior: A comprehensive review. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(2), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.02.004

- Schechter, D. S., Zygmunt, A., Coates, S. W., Davies, M., Trabka, K. A., McCaw, J., Kolodji, A., & Robinson, J. L. (2007). Caregiver traumatization adversely impacts young children's mental representations on the MacArthur Story Stem Battery. Attachment & Human Development, 9(3), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730701453762

- Sheridan, K., Haight, W. L., & Cleeland, L. (2011). The role of grandparents in preventing aggressive and other externalizing behavior problems in children from rural, methamphetamine-involved families. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(9), 1583–1591. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.03.023

- Skinner, E. A., & Edge, K. (2002). Parenting, motivation, and the development of children’s coping. In L. J. Crockett (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation. Agency, motivation, and the life course (Vol. 48, pp. 77–143). University of Nebraska Press.

- Skinner, E. A., Edge, K., Altman, J., & Sherwood, H. (2003). Searching for the structure of coping: A review and critique of category systems for classifying ways of coping. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 216–269. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.216

- Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2007). The development of coping. Annual Review of Psychology, 58, 119–144. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085705

- Skinner, E. A., & Zimmer-Gembeck, M. J. (2016). Early adversity, temperament, attachment, and the differential development of coping. In E. A. Skinner & M. J. Zimmer-Gembeck (Eds.), The development of coping: Stress, neurophysiology, social relationships, and resilience during childhood and adolescence (pp. 215–238). Springer.

- Sotardi, V. A. (2018). Bumps in the road: Exploring teachers’ perceptions of student stress and coping. The Teacher Educator, 53(2), 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2017.1422826

- Suchman, N. E., DeCoste, C. L., McMahon, T. J., Dalton, R., Mayes, L. C., & Borelli, J. (2017). Mothering from the inside out: Results of a second randomized clinical trial testing a mentalization-based intervention for mothers in addiction treatment. Development and Psychopathology, 29(2), 617–636. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579417000220

- Thompson, R. A. (2016). Early attachment and later development: reframing the questions. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 330–348). The Guilford Press.

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Wadsworth, M. E. (2015). Development of maladaptive coping: A Functional Adaptation To Chronic, Uncontrollable Stress. Child Development Perspectives, 9(2), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12112