Abstract

Most research showing results of psychotherapy come from efficacy studies or effectiveness studies from university counselling centers, or therapy clinics at universities. This study is an effectiveness study that aims to investigate the results of psychological treatment in psychiatric clinics for outpatients under naturalistic conditions. The study contributes unique insights regarding the outcomes of psychological treatment for patients with severe psychiatric problems in the complex real environment where many influencing variables exist. Patients were recruited from 2012 to 2016 from psychiatric clinics in Sormland, Sweden in the regular service. They received psychological treatment lasting between 1 and 50 months. The entire period of assessment took place between 2012 and 2021. A total of 325 patients received treatment from 59 participating therapists. Patients completed symptom assessment instruments regarding anxiety, depression, and quality of life at the start of therapy, upon the completion of therapy and, at follow-up one year after completion. Analyses indicated a significant improvement in all outcome instruments between start and completion of therapy. The improvement was largely maintained until follow-up. The effect sizes were moderate. Between 49.1% and 62.9% of patients “improved” or “recovered” as measured by the symptom assessment instruments at completion of therapy. The proportion of improved/recovered on the quality-of-life instrument was 37.4%. In a naturalistic cohort with comparatively severe psychiatric problems, substantial and stable improvements were achieved. The outcomes were respectable considering the population. The study provides external validity to efficacy studies on how psychological treatment works in a real-life context.

1. Introduction

The effectiveness of psychotherapy for psychological health has been repeatedly demonstrated empirically (Lambert, Citation2013). It is well-documented that psychotherapy can reduce symptoms of many psychological problems (Cuijpers et al., Citation2011; Newby et al., Citation2015) and it is especially effective if the problems are not too severe at the start of therapy (McAleavey et al., Citation2019).

Efficacy studies with randomized controlled trials (RCT) have been considered as the leading research design for evaluating the effects of psychotherapy (Lutz, Citation2003). A strict control over the parameters to be studied, randomized groups, use of control groups, manual-based treatments, fixed number of sessions and distinct inclusion and exclusion criteria are significant for RCT efficacy studies. The latter refers to homogeneous groupings of participants that make it possible to link a specific treatment to a certain diagnosis (Nathan et al., Citation2000; Nordmo et al., Citation2020). Given that effectiveness studies examine how a specific intervention works in a clinical setting, several other influencing factors can be present, and reliable causal relationships cannot be established as in RCT studies (Lutz, Citation2003). Another difference between efficacy and effectiveness trials is that the group of therapists are usually more homogeneous in the former. In efficacy trials, therapists are usually specially trained for the specific treatment they provide (Nathan et al., Citation2000).

Most data from benchmarking studies regarding effectiveness trials are from US university counselling centers or therapy clinics. Therefore, the results may not be generalizable to non-university clinical settings (McAleavey et al., Citation2019; Nordmo et al., Citation2020). Other existing naturalistic psychotherapy studies are mostly conducted in primary care or health centers. These agencies treat less severe problems than those treated at psychiatric specialist clinics (Nilsson et al., Citation2020; Rapp et al., Citation2010). Benchmarking studies show a marginal difference in treatment outcomes between efficacy and effectiveness trials (Gaskell et al., Citation2023; Minami et al., Citation2009; Nordmo et al., Citation2020).

In research regarding pharmacological and psychological treatments, it has been noted that effectiveness studies are needed to determine how treatment methods work in everyday clinical settings and efficacy studies are needed to achieve external validity (Hunsley et al., Citation2014; Hunsley & Lee, Citation2007; Lutz, Citation2003; Tiihonen et al., Citation2011). It is also important to determine how the eventual outcomes last over time (McAleavey et al., Citation2019). There is a lack of studies involving outpatient psychiatric specialist clinics where patients report more severe psychiatric conditions and symptoms, and there is a higher level of comorbidity, a lower level of functioning, and more extensive long-term psychiatric problems in the anamnesis (Nordmo et al., Citation2020; Wampold et al., Citation2011). Comorbidity has been associated with worse prognosis for a positive treatment outcome (Koppers et al., Citation2019).

Taking into account the above, this study serves an important function. The aim of the current study was to evaluate the outcome of psychological treatment for outpatients with psychiatric severe problems in a clinical context. We wanted to further determine how the outcome was maintained over time, considering the heterogeneous patient and therapist groups, as well as the different treatment lengths and treatment methods. Few studies such as this exist, in which all of Shadish et al.’s criteria for the highest level of clinical relevance is met: This includes a non-university clinical setting, clinically referred patients, professional therapists with regular caseloads, no standard treatment manual, no monitoring of treatment other than routine supervision, no restriction on therapeutic procedures, heterogeneous patients regarding age, sex, class, and focal problem, and therapists that have not been given any specific training for the purposes of the study (Shadish et al., Citation1997).

It is important to understand the outcome of psychotherapy at the completion of treatment and follow-up. Gaining increased knowledge about the actual results of psychological treatments provided in outpatient psychiatric specialist clinics is valuable for therapists, patients, other care givers, and decision-makers in the care sector.

Healthcare is often highly focused on symptoms and their reduction. Mental suffering can be manifested in ways other than anxiety and depression. To gain a broader perspective on the results of psychological treatment, it may therefore be appropriate to also study the patients’ assessment of perceived quality of life in connection with the treatment, which is why this variable was included in our study.

In this study, we aimed to answer the following questions: Did the outcome of anxiety, depression, and quality of life improve statistically and clinically for outpatients with psychiatric problems after psychological treatment? If patients’ outcomes improved, what was the extent of these improvements? Were the possible psychological treatment outcomes at completion of therapy sustained until one year follow-up? How are the psychological treatment outcomes in this study compared to other effectiveness studies?

In outpatient psychiatric specialist clinics, in addition to psychotherapy, psychological treatments are provided to maintain patients’ mental health status or prevent deterioration. This kind of supportive counselling is provided especially when the risk of suicide is high, when there are other acute crisis reactions, and when patients’ rigidity complicates the work of change. The concept of psychological treatment in this study includes both psychotherapy and supportive counselling.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Procedures

Participants were recruited between December 2012 and December 2016 from five psychiatric outpatient clinics in the county of Sörmland, Sweden. Patients were offered to participate in the study by the therapists responsible for their assessment, and usually for their psychological treatment. Inclusion criteria were broad to maximize generalizability. If the patient and therapist were interested in participating in the study and the patient had sufficient knowledge of the Swedish language as well as the cognitive skills to fill in self-assessment questionnaires, they were included in the study.

The exclusion criterion for the study was contact between the therapist and patient for less than five sessions. Based on clinical experience we considered that at least five sessions were required to achieve any effect of therapy on the patients at a specialist psychiatric clinic. Patients came to the clinic through referrals (approximately 90%) or self-referrals (10%). The referrals were assessed by a multi-professional team before the therapist received the patient. If the therapist assessed the patient to be suitable for psychological treatment, and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were satisfied, the therapist informed the patient about the study. Patients received information regarding the purpose and structure of the study and confidentiality. The completed questionnaires were sent to the research assistant who provided administrative support. The patients and therapists gave consent prior to participation in the study.

Patients filled out self-report questionnaires at three time points: at the start and completion of the psychological treatment, and at one year follow-up after completion of the therapy. At the start and completion of therapy, the therapists directly administered the questionnaires to the patients in-person. The one year follow-up questionnaires were directly sent to the patients’ homes by the research assistant.

After the patient filled out the questionnaires, the therapist and patient decided jointly, according to common routines, about the content and objectives of therapy. The method(s) used during the treatment depended on the therapist’s experience, therapeutic orientation, and training.

The therapists filled out questionnaires about their experience and education at the start of the treatment and about the patient and content of the therapy at the end of treatment.

The questionnaires from the patient and therapist were de-identified and transferred to a coded matrix by the research assistant. Data was de-identified to ensure that the respondents could not be identified based on their answers.

2.2. Sample description

2.2.1. Participating patients

presents a summary of the demographic and clinical data of the 325 patients who answered questionnaires at the start of the psychological treatment and participated in at least 5 sessions of therapy.

Table 1. Demographic and clinical description of the participants. Data was obtained at pre-treatment. “N” varies due to missing data. Maximum N = 325.

Patients were between 18 and 73 years of age when they began participating in the current study (mean age = 35, standard deviation = 12.2). Approximately two thirds or 226 (69.5%) of the participants were women, and 98 (30.2%) were men. One person stated “other” (0.3%) when asked about gender.

A significant majority of the patients had previously received psychological treatment, had been afflicted with psychopathology for several years, and were undergoing a pharmacological treatment before psychotherapy ().

Diagnosis was made according to the current routines in outpatient care. The patient initially underwent a basic psychiatric examination as an in-depth and structured anamnesis supplemented with diagnostic screening instruments and assessment forms. Deviations from the diagnosis procedure mentioned occurred in certain circumstances.

2.2.2. Attrition and adherence

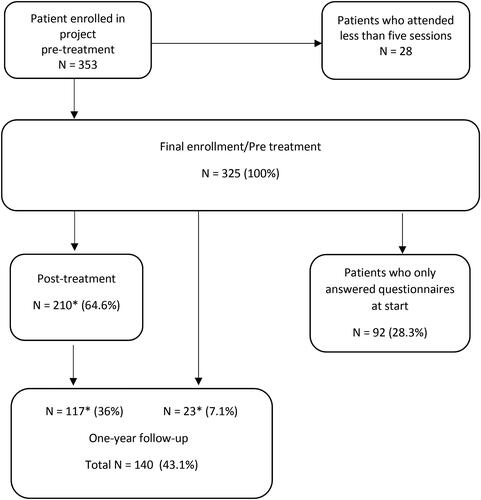

Out of the 353 patients who answered questionnaires at the start of psychological treatment, 28 did not meet the inclusion criterion of having attended at least 5 sessions. Of the remaining 325 patients, nearly 65% also provided post-treatment data and 43% provided one year follow-up data ().

Figure 1. Flowchart of participating patients. Number of patients who answered the questionnaires at the start of therapy, completion, and follow-up.

*There were 117 patients who answered the questionnaires on all three occasions. The number of patients who answered questionnaires on two occasions, at pre-treatment and post-treatment was 93 (210–117) and at pre-treatment and follow-up was 23.

2.2.3. Participating therapists

All 84 therapists who practiced psychological treatment at the 5 outpatient psychiatric clinics while the study was ongoing were invited to participate. Of these, 11 therapists declined to participate, and another 11 did not respond, nor did they participate in the study. Sixty-two therapists chose to participate in the study, of which three did not have any patients for the study. Of the 59 therapists with participating patients 48 (81%) were women and 11 (19%) were men. Out of the 59 therapists, 11 (19%) therapists had between 9 and 21 patients each, which corresponded to about 50% of all patients participating in the study. The remaining 48 (81%) therapists had between 1 and 7 patients.

The therapists in the psychiatric clinics had different levels of psychotherapeutic education and different occupational backgrounds. Most of them were licensed psychologists (27.8%), nurses (25.9%), and psychotherapists (16.6%). Some were nurse assistants (14.8%), medical social workers (5.6%), occupational therapists (5.6%), and psychology students (not yet licensed psychologists, 3.7%). Most therapists had basic (63%) or specialist (19%) training in psychotherapy. Of those who had completed a therapeutic education (82%), 46% had cognitive behavioral focus, 37% had psychodynamic focus, and 14% had integrative focus. Most of the therapists who had not completed basic education in psychotherapy had several years of experience of working at a psychiatric clinic. The average experience of the therapists in psychiatric treatment was 12.5 years (SD = 11.1).

The duration of psychological treatment provided in this study varied between 1 and 50 months with a mean of 12.4 months. The number of sessions varied between 5 and 140 with a mean of 24.5.

2.3. Questionnaires

2.3.1. Primary outcome measures of the study

To measure anxiety, the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (Beck et al., Citation1988) was used. It consists of 21 symptoms of anxiety which patients rate on a scale of 0 (not at all) to 3 (severely) to indicate the extent to which they have been disturbed by these symptoms during the previous seven days. The interpretations of the instrument indicate minimal anxiety (up to seven points), mild anxiety (8–15 points), moderate anxiety (16–25 points), and severe anxiety (26–63 points). High internal consistency was obtained in our sample with a pre-treatment, post-treatment and follow-up Cronbach’s alphas being 0.92, 0.93 and 0.93, respectively (Carlbring et al., Citation2007).

Depression was measured using the Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale Self-Rated (MADRS-S; (Montgomery & Asberg, Citation1979). It consists of nine questions regarding symptoms of depression in the previous three days. Each question is rated from 0 to 6. The total score ranges from 0 to 54 points. In the interpretation of results, 0–10 points indicate no depression; 11–19 points, mild depression; 19–34 points, moderate depression, and 35–54 points, severe depression. There was a high internal consistency in our sample with pre-treatment, post-treatment and follow-up Cronbach’s alphas being 0.86, 0.91 and 0.92, respectively.

The Symptom Check List-90 (SCL-90) (Derogatis et al., Citation1973) was used to describe the overall presence of psychiatric symptoms and their severity. The scale consists of 90 items about problems and complaints that patients rate on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 4 (very much), indicating the intensity of perceived symptoms in the last seven days. Results from SCL-90 are reported in three ways: Global Severity Index (GSI), calculated as the total score divided by 90 and measuring the general level of mental illness; Positive Symptom Total, calculated as the number of non-zero answers divided by the number of symptoms; and Positive Symptoms Distress Index, calculated as the total points divided by the number of non-zero responses resulting in the intensity measure. We used the GSI-score. The GSI is a robust measure of overall symptom severity (Hill & Lambert, Citation2004). We deleted question 21 in the SCL-90 as the question was not up to date. High internal consistency was obtained in our sample with pre-treatment, post-treatment, and follow-up Cronbach’s alphas of 0.96, 0.98 and 0.98, respectively.

To measure quality of life, the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire - Short Form (Q-LES-Q-SF; (Endicott et al., Citation1993), was used. The Swedish translation was revised by the article author prior to the study. The revision was approved by the original author. Q-LES-Q-SF consists of 16 questions regarding the extent to which patients are satisfied or dissatisfied with different aspects of life, reflecting their perceived quality of life, over the past seven days. The scale ranges from 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). The most common way to use the instrument is to indicate the result as a percentage of the maximum score for the first 14 questions. The other two questions are dealt with separately. There is no established classification of different levels of satisfaction regarding Q-LES-Q-SF. There was a high internal consistency in our sample with pre-treatment, post-treatment, and follow-up Cronbach’s alphas of 0.85, 0.92 and 0.92, respectively.

2.4. Data management

Missing values for respective outcome instruments were negligible. Individual lapses on a questionnaire were replaced by the mean. Data were missing completely at random (MCAR): BAI: 0.005%, MADRS-S: 0.01%, SCL-90: 0.007%, Q-LES-Q: 0.006%.

The results of the study are based on an analysis of completed questionnaires. Missing questionnaires were largely due to therapists’ handling difficulties, such as forgetting to distribute questionnaires at completion of therapy. Difficulties in obtaining questionnaires arose when patients completed the treatment over the telephone instead of at the clinic where therapists could hand out questionnaires directly to them. Based on a comparison between patients who completed the questionnaires at different points/occasions of measurements, no significant differences were discovered that would, in any decisive way, be assumed to affect the results in any particular direction. There is no statistically significant difference regarding diagnoses (p-value = 0.8), medication (p = 0.8), age (p = 0.7), baseline BAI (p = 0.8), MADRS-S (p = 0.7), Q-LES-Q (p = 0.4) or SCL-90 (p = 0.9) between patients who completed and who did not completed questionnaires, nor is the difference between gender (p = 0.051) substantial enough to be of clinical relevance.

2.5. Statistical analyses

2.5.1. T-test and significance testing

Dependent t-tests were used to examine whether the mean values of the outcome measures differed significantly between the start and completion of therapy, and between start and one year follow-up.

2.5.2. Effect size

Cohen’s d was used to examine whether any change was achieved in the patients’ assessment of the outcome instruments and if so, whether that change had a clinically significant value. Cohen’s levels for between-group design were used; small (0.2–0.5), moderate (0.5–0.8), and large effect sizes (>0.8) (Cohen, Citation1988). In within-group design, the standard deviation is usually lower, which leads to an increase in the effect size. This means that the outcome in this study cannot directly be interpreted using Cohen’s criteria.

2.5.3. Reliable change

Reliable change (RC) is a way to calculate if a change on a psychological test is reliable and statistically significant, not depending on simple measurement unreliability (Jacobson & Truax, Citation1991). It examines whether there is a positive change, no change, or deterioration of the patient’s clinical condition.

2.5.4. Clinically significant change

Clinically significant change (CSC) is the change from a typical problematic or dysfunctional score to that of the “healthy” population (Jacobson & Truax, Citation1991). First, the person must meet the conditions for a RC. Then there are three ways to calculate if the changes also meet the conditions for CSC: 1) method A - if the person has moved more than 2 SD from the mean of the “problem group”; 2) method B - if the person has moved within 2 SD of the mean of the “normal population”; and 3) method C - if the person has moved closer to the mean of the “normal population” than to the “problem group”. In the current study, we chose method A as it was considered an appropriate way to determine a real change in selected outcome instruments and there were no available studies showing normal population values for MADRS-S. The problem group was identified based on thresholds at baseline. After calculation, individuals’ test results could be sorted into recovered, improved, unchanged, or deteriorated. When calculating RC and CSC, cutoff values were used to exclude patients who, at the start of psychotherapy, could be considered as “healthy,” based on the scores of the self-assessment instrument. Selected cutoff values were BAI ≤ 10 (Westbrook & Kirk, Citation2005), SCL-90 ≤ 66 = 0.73/item (Carrozzino et al., Citation2016), Q-LES-Q ≥ 60 = 82% (Schechter et al., Citation2007), and MADRS-S ≤ 13. The MADRS-S cutoff was selected based on scale comparisons with BAI with which the degree of difficulty level was matched.

2.5.5. Remission and 50% reduction in symptoms

To get a broader perspective on the results of the study, additional calculations were also made. The proportion of patients who achieved remission, that is, “healthy” values on the cutoff of outcome instruments, a 50% or more estimated reduction in symptoms, see Supplementary Material Tables 3–6. Both ways of measuring treatment outcomes are common in pharmacological studies (Baldwin et al., Citation2006; Cipriani et al., Citation2018).

3. Results

3.1. Outcome at completion of treatment and at one year follow-up

A total of 325 patients answered questionnaires at pre-treatment and 210 patients answered questionnaires at both pre- and post-treatment. Of these, 140 patients answered questionnaires also at one year follow-up (see ).

Table 2. Pre- to post-treatment and pre- to one year follow-up. Means, standard deviations (SDs), effect sizes (Cohen’s d) for outcome measures, t-values, and p-values.

This outcome can be compared to the results for the group of patients who answered the questionnaires on all occasions, see Supplementary material Table 1.

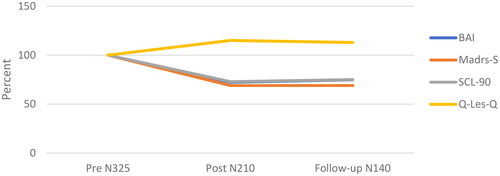

3.2. Percentage change from pre-treatment to post-treatment and follow-up

Percentage changes of mean values on outcome instruments from pre-treatment (100%) to post-treatment and follow-up are shown in . From pre-treatment to post-treatment, the value of BAI decreased to 72.3% of the baseline value (i.e. a decrease of 27.7%), and from post-treatment to follow-up, it increased slightly to 74.8% (a decrease of 25.2% from baseline). MADRS-S decreased to 69% at post-treatment compared to baseline, a decrease of 31% which was maintained at follow-up. On SCL-90, the value decreased to 72.9% at post-treatment relative to the baseline and increased to 75% at follow-up. Regarding Q-LES-Q, the mean perceived quality of life increased to 115% at post-treatment compared to baseline and decreased to 113% at follow-up.

3.3. Reliable change Index (RCI) and clinically significant change (CSC)

shows the severity rating at pre-treatment, post-treatment, and follow-up for all outcome instruments for patients who scored on or above the cutoffs on the symptom assessment instruments and on or below the cutoff on the quality-of-life instrument. For applied cut offs see subsection 2.5.4.

Table 3. Number of patients who recovered (i.e. achieved reliable change and clinically significant change), improved (reliable positive change), remained unchanged, or deteriorated (reliable negative change) on each outcome instrument at completion of therapy and follow-up one year after completion of therapy.

For results regarding remission and 50% reduction in symptoms please see Supplementary Materials.

4. Discussion

Patients mean pre- and post-treatment reported values showed significant improvements on instruments measuring depression, anxiety, and general psychiatric symptoms, as well as quality-of-life. This improvement was maintained at follow-up one year after completion. On all symptom assessment instruments, mean scores decreased by almost a third at post-treatment compared to baseline. At follow-up, mean scores increased slightly on two of three instruments by a few percentage points. On the MADRS-S, the score remained unchanged. On quality of life, the mean score increased by 15% and went down to a 13% increase at follow-up compared to baseline.

A moderate effect size was achieved on all outcome instruments at completion of treatment. A fairly large effect size was obtained from the MADRS-S. A moderate effect size was obtained on all outcome instruments between pre-treatment and one year follow-up. The effect sizes in the current study were better than those in studies where only psychopharmacological treatment was used (Leucht et al., Citation2012). Most patients in the current study were undergoing parallel medical treatments which started before psychotherapy. In a study examining the improvement achieved by psychotherapy as an adjunct to medical treatment, the effect size was 0.43 (Cuijpers et al., Citation2014), which was exceeded in the current study if we exclude the initial presumed medical effect that the majority of patients had before starting psychotherapy. In the current study, the mean effect size for all symptom and quality of life instruments at completion of psychotherapy was 0.64.

There are no significant differences when comparing treatment outcomes for those patients who completed questionnaires at all time points with outcomes for all patients, see Supplementary Material Table 1.

Between 49.1% and 62.9% of the patients experienced an RC (improved) or CSC (recovered) at completion of psychotherapy on the symptom assessment instruments BAI, MADRS-S, and SCL-90 (see ). Between 24.7% and 43.6% of patients remained unchanged and between 7.3% and 12.4% of patients reliably deteriorated. Almost one-third of the patients experienced complete recovery as indicated by the MADRS-S. There was a lower rate of improvement or recovery (37.4%) as indicated from the quality-of-life questionnaire, Q-LES-Q. Almost 59% of patients remained unchanged.

On all outcome instruments, the proportion of patients that reliably deteriorated was within the range of 5.3–12.4%, with the lowest proportion being on the Q-LES-Q and the highest on the SCL-90. The proportion of deterioration is usually around 5–10% after completion of treatment, according to a study by Lambert (Citation2013), which corresponds to the results in this study. In studies that focus on symptoms, the proportion of patients who do not achieve change from psychotherapy can range from 30% to over 50% (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021; Lambert, Citation2017; van Bronswijk et al., Citation2019). In the current study, the proportion of unchanged patients ranged between 24.7% and 43.6% on the symptom outcome instruments at post-treatment and between 19% and 48.7% at follow-up, which can be considered a decent result, especially on the SCL-90. The average proportion of no change on the symptom assessment instruments is about 36% post-treatment and about 37% at follow-up, which puts the unchanged rate in the current study in the lower range compared to that in peer-reviewed studies.

The proportion of patients that improved and recovered one year after completion of treatment is comparable with the proportion of patients that improved and recovered at completion on the MADRS-S and SCL-90. Thus, the symptomatic improvement was largely sustained until follow-up. In contrast, there was a larger reduction in patients that improved and recovered as indicated by the BAI and Q-LES-Q at follow-up.

The result that stands out is the proportion of patients that deteriorated on the SCL-90, where the proportion went from 12.4% at completion of treatment to 23.1% at one year after completion. The largest positive change was also achieved on the SCL-90, where 62.9% of patients improved or recovered at completion of treatment and 57.9% further improved or recovered at follow-up. It seems that the SCL-90, which is a broad questionnaire containing various symptom assessment questions including anxiety and depression, was the most decisive instrument for showing the symptom results of psychological treatment. Further investigations may focus on patient factors associated with a positive outcome from psychological treatment, and deterioration after completion of therapy in psychiatric care for outpatients.

Our findings suggest that psychological treatment has a more positive effect on anxiety and depression than on quality-of-life. The Q-LES-Q had the largest proportion of unchanged patients at completion of therapy and follow-up (around 60%). It would be desirable to obtain more knowledge about which aspects of quality-of-life are affected by psychological treatment in psychiatric care for outpatients, to determine how psychological treatment could affect quality-of-life to a greater extent. If quality of life is low at the start of psychological treatment, it has been shown to remain unchanged at the completion of therapy (Herzog et al., Citation2022).

Other examples of effectiveness studies that have been published in recent years include the works of Nordmo et al. (Citation2020) and Westbrook and Kirk (Citation2005). Nordmo et al. (Citation2020) investigated the results of open-ended psychotherapy on a sample consisting of mostly outpatients with psychiatric problems. Patients experienced positive changes in self-report measures of overall psychiatric symptoms and most of them (69%) experienced a reliable improvement or recovery/CSC in symptoms measured by the SCL-90, with an effect size of 0.85. The improvement was largely sustained at follow-up measurement. Westbrook and Kirk (Citation2005) investigated patients treated with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) in routine clinical practice in a National Health Service. The results suggest that CBT is a well-functioning treatment in that context, although the results achieved may not be as good as in research trials. Almost 50% of the patients experienced a reliable improvement or recovery/CSC in both reported anxiety (49.5% for the BAI) and depression (47.9%. for the Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI)). Effect size for the BAI was 0.54 and for BDI was 0.67.

Compared to Nordmo’s study, our results are somewhat modest when comparing outcomes on the SCL-90 from pre-post and pre-follow-up. Conversely, our results are relatively comparable to Westbrook and Kirk’s study when comparing outcomes on the BAI and MADRS-S/BDI from pre-post treatment (see Supplementary Material Table 1).

Nordmo et al.’s study (Nordmo et al., Citation2020) has many parallels to the current study. It must be noted that the patients in the two studies differ in essential aspects. A large proportion of patients participating in Nordmo et al.’s study were recruited from psychiatric clinics for outpatients in Scandinavia. A non-negligible share (18.6%) of patients in Nordmo et al.’s study was recruited from a student clinic at a university and a clinic with physiotherapists. Therefore, the problem severity of those patients may not be comparable with that of the patients in psychiatric clinics. The mean SCL-90 values for patients’ at the start of psychotherapy in Nordmo et al.’s study was a GSI-score of 115 (Nordmo et al., Citation2020) compared with the current study’s GSI of 140.5 (i.e. over 22% higher symptom assessment in the current study). The mean number of sessions patients received in Nordmo et al.’s study was 51.3 compared with 24.5 in the current study. The average duration of psychotherapies in Nordmo et al.’s study was 24.5 months, while it was 12.4 months in the current study.

The proportion of patients in Nordmo et al.’s study who, at the start of the psychotherapy, took medication when needed was 7%, or took medication regularly was 22%, which can be compared with the current study where 77.8% of patients took medication regularly due to mental disorders. Of the nearly 80% patients who took medication regularly at the start of the psychological treatment, 40.7% regularly took two or more medications. Gender distribution and average age are identical in Nordmo et al.’s study and the current one.

The results of the current study are similar to those of Westbrook and Kirk’s study in terms of the percentage of patients who recovered and improved on the BAI questionnaire. The effect sizes are also comparable. The baseline BAI scores show that the mean scores are slightly higher in the current study, above five points of the cutoff scores and seven points when all patients are included. A total of 23.5% of patients in Westbrook and Kirk’s study and 83.5% in the current study had previously availed psychological treatment. Thus, we can assume that the patients in the current study, compared to those in Westbrook and Kirk’s study, are burdened with more psychiatric severity.

The proportion of patients who achieved remission on the symptom assessment instruments ranged from 27 to 39% (see Supplementary Material Table 3). The result is similar to that of a meta-study where about one-third of patients achieved remission (Cuijpers et al., Citation2021). At the completion of therapy, only 5.7% of patients rated their health level comparable to that of the “healthy” population on the quality-of-life instrument (i.e. achieved remission). This probably confirms the burden of care and low level of functioning of patients at the psychiatric clinics in the current study, where patients often return at a later stage for further treatment of various kinds. Even if patients make significant progress in treatment and achieve significant reduction in symptoms, this rarely leads to an increased quality of life at par with the “healthy” population.

Just over one-third of patients have had a 50% or greater reduction in symptoms upon completion of therapy (see Supplementary Material Table 5). This effect seems to persist at follow-up, although there is some variation within the patient group (see Supplementary Material Table 6).

Overall outcomes of psychological treatment are rather unclear and unexplored in psychiatric outpatient clinics. Increased knowledge in the field provides a better basis for decision-makers, increases opportunities for therapists to provide tailored treatment to patients, and allows patients to gain a better understanding of the outcomes that can be achieved through psychological treatment. The fact that psychological treatment can have sustained outcomes for many patients, especially in terms of symptom reduction, is important knowledge for therapists, patients, and decision-makers in the care sector. At the same time, it is necessary to understand that a relatively large proportion of patients do not achieve significant symptom reduction. This needs to be made visible and discussed further, based on actual clinical realities and not from assumptions. The value of psychological treatment, even for the latter group, may be of great importance in preventing suicide, ward admission, worsening of suffering and deterioration at a functional level (even if this is not reflected in any improvement at symptom level). Further studies could then investigate patient satisfaction with treatments, regardless of outcome.

This study has some limitations. Neither the therapists nor the patients were randomized to participate in the study and there was no control group. There was also a difference between the number of patients each therapist recruited. Nearly 19% of therapists had almost 50% of all participating patients, which means a minority of therapists had a major influence on the results of the study. However, we can conclude that there are no significant differences in treatment outcomes between the 11 therapists who have almost 50% of all patients in the study compared with the remaining 48 therapists who have all other patients, see Supplementary material Table 10. There was no control over which patients were not included in the study and on what basis these decisions were made by the therapists. In outpatient psychiatric care, patients can be treated for acute problems when they attend psychotherapy for the first time, which is why submission of questionnaires is not a priority. This increases the risk of questionnaires being forgotten, as well as the offers to participate in the study. Moreover, we do not know to what extent specific medications or life events outside the treatment room affected the results. This was a real-life study where many factors could have affected the result as the treatment took place in a realistic environment. The fact that the study involves a mix of patients with different problems and a mix of therapies are limitations that reduce internal validity. However, this increases external validity.

Whether the outcomes accurately reflect the results for all therapists is not the focus of this study. ANOVA counts show no significant differences in outcomes at completion of psychological treatment between therapists with different levels of psychotherapeutic training or between different therapeutic orientations (see Supplementary Material Tables 7 and 8). Reservation for the calculations is appropriate. Existing calculations have not been adjusted for base line values (which can give an indication of the patient’s burden of care) nor have we considered that a therapist may have had many patients in the study, which may significantly affect the results based on the category that the therapist belongs to. We could also consider the patients’ diagnosis and the main type of counselling provided, which may further affect outcomes. Some therapists also treat more patients for psychological treatment by focusing on supportive counselling, which may mainly be of a maintenance nature: preventing suicide, preventing hospitalization, and preventing deterioration in well-being (i.e. they do not work much with transition processes from a psychotherapeutic perspective). The possible impact of therapists on outcomes should be investigated further.

The lack of a uniform systematic diagnosis method can lead to uncertainty regarding the reliability of diagnoses for patients participating in the study. This is common in many other psychiatric clinics in Sweden. There are guidelines, recommendations, and care programs for diagnosis, but those cannot always be followed for various reasons. In particular, the initial diagnosis, before initiating the psychological treatment is uncertain. The diagnosis can often be preliminary, or a not-so-thoroughly-investigated diagnosis performed by a trainee doctor.

There were no strict routines regarding the assessment and diagnosis by the therapists. Some used certain questionnaires to help, others did not. Some therapists made the actual diagnosis based on the initial meeting with the patient, while others left the previous diagnosis intact in the medical records. Sometimes the diagnosis was discussed in interprofessional teams and sometimes not. The priority of the psychiatric clinic is often to deal quickly with the patient’s acute problems to prevent suicide, admission to an inpatient ward, or aggravation of mental suffering instead of immediately making a detailed diagnostic investigation where differential diagnostic considerations are included. Patients are often in immediate need of care and considerations are made as to whether there is a clinical relevance of, for example, a neuropsychiatric or personality investigation. It is common for the patient’s initial diagnosis to be revised gradually as treatment continues and new information is obtained about the patient’s problems, difficulties, and disabilities. A reasonable assumption, when the diagnoses are not too thorough at the start of the psychological treatment, is that many patients are underdiagnosed, have personality disorders, and neuropsychiatric disabilities that require more detailed investigations. Thus, the possibility of detecting patients’ real comorbidity also deteriorates, which complicates the description of the extent and complexity of the patients’ actual problem in specialist psychiatry clinics.

Certain weaknesses in the diagnostic procedure led to patients, in some cases, not being offered the most accurate treatment based on their needs. Such examples had a negative effect on the results of this study. At the same time, from a clinical experience as psychotherapists, we know patients’ problems in psychiatry are so complex and multifactorial that traditional treatment manuals often have limited effect. Other tools can be more effective to achieve constructive change, such as the therapist’s ability to create a trustful relationship with the patient and adapt the treatment based on the patient’s unique combination of problems, level of function, and personality. The fact that there were no significant differences in patient outcomes between practitioners with different levels of psychotherapeutic training or different therapeutic orientations may indicate that factors other than the ability to follow treatment manuals tailored to the correct diagnosis are crucial to good treatment outcomes for patients in psychiatry. It may also be emphasized that waiting for in-depth investigations can be of value. Sometimes knowledge about the patient’s problems increases during the therapy and clear information is obtained that would have been difficult to detect in an initial survey and assessment, no matter how extensive it was. We should also consider that trade-offs are made as to whether an investigation is clinically relevant. Thus, what benefit does the patient and therapist make through an in-depth investigation in relation to the patient’s problems, wishes, and level of function?

5. Conclusions

In the current study, a non-negligible proportion of patients had been hospitalized on one or more occasions or were treated at homes due to mental illness. A significant majority of patients previously had one or more years of psychological treatment before starting therapy. Given the high proportion of patients who were already on medications at the start of treatment, the relatively short average treatment time, and patients’ problem severity compared to that in other studies, the symptom reduction is considerable. Patients with severe psychiatric problems have more difficulty making progress (McAleavey et al., Citation2019). The significant reduction in symptoms between pre- and post-treatment seemed to be maintained at follow-up. The effect sizes achieved were respectable. Moreover, around one-third of patients achieved remissions in symptoms and over one-third achieved a 50% or greater reduction in symptoms at completion of therapy (see Supplementary Material Tables 3 and 5). However, the results were less impressive in terms of improving quality-of-life.

Given that almost four fifths of the patients had already started pharmacological treatment before psychological treatment, there is reason to believe that the main cause of improvement after starting psychological treatment was not explained by the medical treatment, especially considering that for many patients, the change was largely intact one year after completion of treatment. However, we cannot claim this with certainty as the medication/dosage may also have changed during the psychological treatment.

Time could not be seen as the main explanation for improvement, as symptom reduction ceased after psychological treatment was completed. After completion of psychological treatment, the level of symptoms remained relatively stable up to one year later.

This study is relevant as it represents the patient base in outpatient psychiatric care from the perspective of patients’ burden of care, disability, and complexity of problems. The study is an important complement to other effectiveness and efficacy studies.

The study was mainly concerned with the outcome effects of psychological treatment on outpatients with psychiatric problems. This raises several new questions. How satisfied are patients with treatment regardless of symptom outcome? What effect do medicines have on treatment? What is the presence of risk factors, such as risky use of alcohol, and how do those affect the results in such cases? Are there differences between the severity of problems for patients who are offered short and long treatment times and are different outcomes achieved for these patient groups? Further research could shed light on this.

Ethics statement

The Ethics Review Authority in Sweden approved the study, approval no 2012/1308-31 and after additions 2016/310-32.

Author contributions

JL, KG, and TL initiated and started the project and contributed to the conception and design of the work. JL and KG were responsible for the organization and collection of data. JL and TA were mainly responsible for the design and content of the article and analysis of data. All authors discussed the results. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (75.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank all patients and therapists for their commitment and participation in the study. We are deeply grateful for the solid work of research assistant Pirjo Suominen, who was responsible for the management and entry of patients’ and therapists’ completed questionnaires into the database, as well as for the management of the database. Nicklas Pihlström, statistician at the Centre for Clinical Research in Sörmland, and Johan Westerbergh, statistician at Uppsala Clinical Research Center have provided invaluable help and knowledge regarding statistical handling and processing of the data.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baldwin, D. S., Huusom, A. K., & Maehlum, E. (2006). Escitalopram and paroxetine in the treatment of generalised anxiety disorder: Randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind study. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 189, 264–272. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.012799

- Beck, A. T., Epstein, N., Brown, G., & Steer, R. A. (1988). An inventory for measuring clinical anxiety: Psychometric properties. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 893–897. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.56.6.893

- Carlbring, P., Brunt, S., Bohman, S., Austin, D., Richards, J., Öst, L.-G., & Andersson, G. (2007). Internet vs. paper and pencil administration of questionnaires commonly used in panic/agoraphobia research. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(3), 1421–1434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2005.05.002

- Carrozzino, D., Vassend, O., Bjørndal, F., Pignolo, C., Olsen, L. R., & Bech, P. (2016). A clinimetric analysis of the Hopkins Symptom Checklist (SCL-90-R) in general population studies (Denmark, Norway, and Italy). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 70(5), 374–379. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2016.1155235

- Cipriani, A., Furukawa, T. A., Salanti, G., Chaimani, A., Atkinson, L. Z., Ogawa, Y., Leucht, S., Ruhe, H. G., Turner, E. H., Higgins, J. P. T., Egger, M., Takeshima, N., Hayasaka, Y., Imai, H., Shinohara, K., Tajika, A., Ioannidis, J. P. A., & Geddes, J. R. (2018). Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet (London, England), 391(10128), 1357–1366. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32802-7

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral science. Routledge.

- Cuijpers, P., Andersson, G., Donker, T., & van Straten, A. (2011). Psychological treatment of depression: Results of a series of meta-analyses. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 65(6), 354–364. https://doi.org/10.3109/08039488.2011.596570

- Cuijpers, P., Karyotaki, E., Ciharova, M., Miguel, C., Noma, H., & Furukawa, T. A. (2021). The effects of psychotherapies for depression on response, remission, reliable change, and deterioration: A meta-analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 144(3), 288–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13335

- Cuijpers, P., Sijbrandij, M., Koole, S. L., Andersson, G., Beekman, A. T., & Reynolds, C. F. 3rd (2014). Adding psychotherapy to antidepressant medication in depression and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis. World Psychiatry: Official Journal of the World Psychiatric Association (WPA), 13(1), 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20089

- Derogatis, L. R., Lipman, R. S., & Covi, L. (1973). SCL-90: An outpatient psychiatric rating scale—Preliminary report. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 9(1), 13–28.

- Endicott, J., Nee, J., Harrison, W., & Blumenthal, R. (1993). Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire: A new measure. Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 29(2), 321–326.

- Gaskell, C., Simmonds-Buckley, M., Kellett, S., Stockton, C., Somerville, E., Rogerson, E., & Delgadillo, J. (2023). The effectiveness of psychological interventions delivered in routine practice: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 50(1), 43–57. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-022-01225-y

- Herzog, P., Feldmann, M., Kube, T., Langs, G., Gärtner, T., Rauh, E., Doerr, R., Hillert, A., Voderholzer, U., Rief, W., Endres, D., & Brakemeier, E.-L. (2022). Inpatient psychotherapy for depression in a large routine clinical care sample: A Bayesian approach to examining clinical outcomes and predictors of change. Journal of Affective Disorders, 305, 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.02.057

- Hill, C. E., & Lambert, M. J. (2004). Methodological issues in studying psychotherapy processes and outcomes. Bergin and Garfield’s Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, 5, 84–135.

- Hunsley, J., Elliott, K., & Therrien, Z. (2014). The efficacy and effectiveness of psychological treatments for mood, anxiety, and related disorders. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 55(3), 161–176. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036933

- Hunsley, J., & Lee, C. M. (2007). Research-informed benchmarks for psychological treatments: Efficacy studies, effectiveness studies, and beyond. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 38(1), 21–33. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.38.1.21

- Jacobson, N. S., & Truax, P. (1991). Clinical significance: A statistical approach to defining meaningful change in psychotherapy research. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(1), 12–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006x.59.1.12

- Koppers, D., Kool, M., Van, H., Driessen, E., Peen, J., & Dekker, J. (2019). The effect of comorbid personality disorder on depression outcome after short-term psychotherapy in a randomised clinical trial. BJPsych Open, 5(4), e61. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2019.47

- Lambert, M. J. (2013). Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change. John Wiley & Sons.

- Lambert, M. J. (2017). Maximizing psychotherapy outcome beyond evidence-based medicine. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 86(2), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1159/000455170

- Leucht, S., Hierl, S., Kissling, W., Dold, M., & Davis, J. M. (2012). Putting the efficacy of psychiatric and general medicine medication into perspective: Review of meta-analyses. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 200(2), 97–106. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.096594

- Lutz, W. (2003). Efficacy, effectiveness, and expected treatment response in psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 59(7), 745–750. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.10169

- McAleavey, A. A., Youn, S. J., Xiao, H., Castonguay, L. G., Hayes, J. A., & Locke, B. D. (2019). Effectiveness of routine psychotherapy: Method matters. Psychotherapy Research: Journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 29(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2017.1395921

- Minami, T., Davies, D. R., Tierney, S. C., Bettmann, J. E., McAward, S. M., Averill, L. A., Huebner, L. A., Weitzman, L. M., Benbrook, A. R., Serlin, R. C., & Wampold, B. E. (2009). Preliminary evidence on the effectiveness of psychological treatments delivered at a university counseling center. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56(2), 309–320. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015398

- Montgomery, S. A., & Asberg, M. (1979). A new depression scale designed to be sensitive to change. The British Journal of Psychiatry: The Journal of Mental Science, 134, 382–389. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382

- Nathan, P. E., Stuart, S. P., & Dolan, S. L. (2000). Research on psychotherapy efficacy and effectiveness: Between Scylla and Charybdis? Psychological Bulletin, 126(6), 964–981. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.126.6.964

- Newby, J. M., McKinnon, A., Kuyken, W., Gilbody, S., & Dalgleish, T. (2015). Systematic review and meta-analysis of transdiagnostic psychological treatments for anxiety and depressive disorders in adulthood. Clinical Psychology Review, 40, 91–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.06.002

- Nilsson, L., Borgstedt-Risberg, M., Brunner, C., Nyberg, U., Nylén, U., Ålenius, C., & Rutberg, H. (2020). Adverse events in psychiatry: A national cohort study in Sweden with a unique psychiatric trigger tool. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2447-2

- Nordmo, M., Sønderland, N. M., Havik, O. E., Eilertsen, D. E., Monsen, J. T., & Solbakken, O. A. (2020). Effectiveness of open-ended psychotherapy under clinically representative conditions. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 11, 384. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00384

- Rapp, M. A., Majic, T., Pluta, J.-P., Mell, T., Kalbitzer, J., Treusch, Y., Heinz, A., & Gutzmann, H. (2010). [Pharmacotherapy of neuropsychiatric symptoms in dementia in nursing homes: A comparison of service provision by psychiatric outpatient clinics and primary care psychiatrists]. Psychiatrische Praxis, 37(4), 196–198. [German] https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0029-1223475

- Schechter, D., Endicott, J., & Nee, J. (2007). Quality of life of ‘normal’ controls: Association with lifetime history of mental illness. Psychiatry Research, 152(1), 45–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2006.09.008

- Shadish, W. R., Matt, G. E., Navarro, A. M., Siegle, G., Crits-Christoph, P., Hazelrigg, M. D., Jorm, A. F., Lyons, L. C., Nietzel, M. T., Prout, H. T., Robinson, L., Smith, M. L., Svartberg, M., & Weiss, B. (1997). Evidence that therapy works in clinically representative conditions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 65(3), 355–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.65.3.355

- Tiihonen, J., Haukka, J., Taylor, M., Haddad, P. M., Patel, M. X., & Korhonen, P. (2011). A nationwide cohort study of oral and depot antipsychotics after first hospitalization for schizophrenia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(6), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10081224

- van Bronswijk, S., Moopen, N., Beijers, L., Ruhe, H. G., & Peeters, F. (2019). Effectiveness of psychotherapy for treatment-resistant depression: A meta-analysis and meta-regression. Psychological Medicine, 49(3), 366–379. https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329171800199X

- Wampold, B. E., Budge, S. L., Laska, K. M., Del Re, A. C., Baardseth, T. P., Fluckiger, C., Minami, T., Kivlighan, D. M., & Gunn, W. (2011). Evidence-based treatments for depression and anxiety versus treatment-as-usual: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(8), 1304–1312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.012

- Westbrook, D., & Kirk, J. (2005). The clinical effectiveness of cognitive behaviour therapy: Outcome for a large sample of adults treated in routine practice. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 43(10), 1243–1261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.09.006