Abstract

Play and exploration may develop within the child’s early attachment relationship to e.g. their mother. This study examined whether attachment security and disorganisation predicted the developmental level of play as well as the duration of pretend play in a low-risk sample. 64 mother-child dyads participated in an assessment of child attachment at 18 months (using the Strange Situation Procedure) and a 20-minute laboratory play setup including four different conditions at 30 months. Children’s play were coded using the 12 Step Play Scale. Generalized estimating equations showed a significant positive association between attachment security and developmental play level. Further, play level scores decreased as disorganisation increased in a story stem play condition. There were no significant associations regarding attachment and duration of pretend play. Our findings indicate the importance for a secure base that the child can explore from, leading to a more developmentally advanced play.

Through play, children learn to understand the world and people around them. Play contributes to the cognitive, physical, social, and emotional well-being of children (Ahloy-Dallaire et al., Citation2018; Valentino et al., Citation2006). Particularly pretend play, i.e. including imaginary components, has received special attention as it is generally acknowledged to mark a major cognitive shift towards symbolic functioning, i.e. the ability to represent objects mentally (Piaget, Citation1962; Vygotsky, Citation1978). Moreover, pretend play serves an important function in the development of complex psychological functions (e.g. theory of mind, creativity, intelligence, language, emotion regulation, etc.) and is crucial for optimal development (for a review, see Lillard et al., Citation2013). Studies have found that parental participation in the child’s play can developmentally elevate the play both in matureness and duration (Bigelow et al., Citation2004, Citation2010; Bornstein et al., Citation1996; Damast et al., Citation1996; Fiese, Citation1990). In general, children’s close relationships in the early years act as a critical mediator of the child’s developmental trajectory (Ginsburg et al., Citation2007). For example, the security of children’s attachment relationships plays an important role in children’s engagement and interactions with their surroundings (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978) and thus may also affect the development of play. The present study aims to investigate if early child attachment security and disorganization predict the developmental level and duration of play in 30-months-old children.

Researchers have reported how children’s play develops during the first years of life (Belsky & Most, Citation1981; Fenson & Ramsay, Citation1980; Lowe, Citation1975; McCall, Citation1974; McCune-Nicolich, Citation1981; Spencer & Meadow-Orlans, Citation1996). In its earliest form, play presents as visual exploration which is followed by oral exploration of objects. Play then begins to include physical exploration which becomes increasingly complex as the child starts by exhibiting simple manipulation of objects, then moves through functional play (i.e. playing with toys according to their intended function like rolling a ball) and then develops functional-relational behaviour where objects are brought together in play (e.g. assembling toy bricks). The next step in play development is entering the phase of pretend play (also termed e.g. symbolic, fantasy, imaginary, and figure-role play). At around 2.5 years in typically developing children, it is to be expected that they are able to engage in pretend play (Belsky & Most, Citation1981; Fonagy & Target, Citation1996). Pretend play can be defined as “an activity that involves role play, object substitution, and imaginative situations” (Shim, Citation2007, p. 18). Pretend play indicates that play activities become decontextualised (Bates, Citation1979; Belsky & Most, Citation1981) as they “become increasingly detached from particular and immediately present situations, persons and objects” (Fein, Citation1979, p. 2). Children exhibit pretend play when real life situations are imitated and acted out during play; e.g. making car noises while driving a toy car or moving a toy horse in bouts in a lively fashion, using short narratives (“she eats”), and also start attributing moods to toy figures. Through pretend play, children act out stories involving multiple perspectives and start to playfully manipulate ideas and emotions (Kaufman et al., Citation2012). As mentioned, research indicates that play is a precursor to the development of various psychological functions (for a review, see Lillard et al., Citation2013), but less attention has been on investigating factors in the child’s social environment that affect their play development. One of these factors may be the child’s early attachment relationship as it has been suggested children develop exploration and play within those relationships (Bowlby, Citation1969; Grossmann et al., Citation2008).

According to attachment theory, first presented by John Bowlby (Citation1969), the attachment system and the exploratory system are two separate but interlinked mutually inhibiting behavioural systems (Cassidy, Citation2008), meaning that when the child’s attachment system is activated, the exploration system is inhibited (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978). These behavioural systems are reflected in children’s need for protection and the need to explore the environment, respectively (Ainsworth, Citation1985). When there is no stress, the caregiver may act as a secure base for exploration (Bowlby, Citation1969; Grossmann et al., Citation2008). When the attachment system is active, e.g. when the child is tired/frightened and needs protection and proximity, the caregiver provides a safe haven for the child in affect regulation (Mikulincer et al., Citation2003). A balance between the two systems characterises secure attachment (B). These children will typically explore the environment eagerly, knowing that a secure base is available (Grossmann et al., Citation2008). When they perceive a threat, they actively seek comfort but are promptly able to return to their exploratory activities knowing a safe haven is available (Whipple et al., Citation2011). Children with an insecure-avoidant (A) attachment relationship will likewise explore readily but display little affect and secure base behaviour even when faced with a threatening or stressful situation (Solomon & George, Citation2008). In contrast, children with an insecure-resistant (C) attachment relationship will typically show angry resistant and passive behaviour aimed at eliciting a response from the mother, which prevents the child from engaging in exploratory activities (Whipple et al., Citation2011).

Considering that young children’s exploration of the environment largely consists of play, it might be expected that attachment security would play a role in children’s play development. Given that according to attachment theory as explained above, securely attached children are better able to explore their environment than insecurely attached children, these children might show a more advanced play development. However, research on the role of attachment security on children’s play development is relatively limited and most studies are from the 1980–90s. One explanation may be that play has not been considered a valuable research area in and of itself, but instead only considered a phenomenon affecting other developmental domains (Bergen et al., Citation2013; Bergen & Fromberg, Citation2021). Thus, it has not been more researched in relation to attachment previously, as research seems to have focused more on the role of attachment for outcomes of play development such as cognitive development, e.g. executive functioning or school performance (Bernier et al., Citation2015). The limited number of studies investigating the link between attachment and play have found mixed results. A study with 48 two-year-olds investigated the link between attachment security (assessed with the Strange Situation Procedure; SSP, Ainsworth et al., Citation1978), and pretend play (defined as the children showing clear signs of pretending and imagining) in a free solitary play setting in a laboratory (Matas et al., Citation1978). They found securely attached engaged more in pretend play than insecurely attached children. Moreover, in a study of 24 three-year-olds observed in a free play laboratory setting with a peer, Jacobson and Wille (Citation1986) found securely attached children, assessed with the SSP, were more likely than insecurely attached children to explore the environment and less likely to play with toys without the peer. However, no associations of attachment security and playing with toys were found. Kerns and Barth (Citation1995) examined 54 three-to-four-years-old children engaging in physical play (i.e. tumbling and tickling) with their parents and found a positive correlation between attachment security (measured on the Attachment Q-set; Waters & Deane, Citation1985) and play engagement: Mother-child attachment security correlated with higher play engagement, and father-child attachment security correlated with measures of play quality. Conversely, one study by Main (Citation1983) of 40 21-month-olds examining solitary free play and structured play with a stranger found no association between attachment security (measured with the SSP) and amount of pretend play (coded based on Piaget’s (Citation1962) descriptions of symbolic play). Finally, McElwain et al. (Citation2003) investigated 1,060 mother-child dyads for a link between attachment, assessed at 15 months using SSP, and pretend play, assessed at 36 months in a free solitary play situation in a laboratory using a modified version of the 12 Step Play Scale (Belsky & Most, Citation1981). They found that in accordance with attachment theory, securely attached children and children with an insecure-avoidant attachment relationship exhibited more pretend play than children with an insecure-resistant attachment relationship.

For play differences between the insecure groups, findings are less clear. The reviewed studies suggest insecure-resistant attachment is associated with a compromised quantity of play as theory would predict. Cassidy and Berlin (Citation1994) point to the interference of the mother in the child’s exploration as a possible cause of inhibited play of children with resistant attachment relationships. For the insecure-avoidant pattern, the findings are contradictory. Two out of the four reviewed studies point towards less play with a peer and less pretend play compared to secure attachment (Jacobson & Wille, Citation1986; Matas et al., Citation1978). However, McElwain et al.'s study (2003), which has the largest sample by far, found no pretend play differences between secure and avoidant groups, while another study notably found that children with an avoidant relationship exhibited more object play than children with a secure or resistant relationship (Lewis & Feiring, Citation1989). In this latter study, three-month-olds were observed in a free play setting with the mother in their home, and those who were later categorized as avoidant played more with objects compared to those with secure and resistant attachment as measured with the SSP (Lewis & Feiring, Citation1989). These findings are in line with the above-mentioned theoretical assumptions that children with an insecure-avoidant attachment relationship may even show more exploration than children with insecure-resistant relationships and thus may not always be hampered in their play development. However, it is important to point out that a higher quantity of play does not necessarily mean it is more developmentally advanced. Studies have noted that avoidant children seem to be more focused on the environment and exploring it, but their play is superficial because they have to constantly monitor the parent to be able to keep avoiding them (Cassidy & Berlin, Citation1994; Groh, Citation2021). This would explain the findings described above, i.e. that there is more object play than in the secure or resistant attachment groups. Presumably these two latter groups are more focused on the parent and thus less focused on objects. Thus, more—perhaps superficial—object play may not necessarily be good or better for the child’s development. This theoretical notion highlights the importance of including both quantity and maturity measures of play which the present study contributes. However in general, there is a tendency to describe the measurement of play insufficiently, not enabling further comparisons of the reviewed studies.

Disorganised attachment was developed as a fourth attachment category to classify children who exhibited odd, inexplicable, or contradictory behaviour during the reunion episodes of the SSP (Main & Solomon, Citation1986). Although less efficient than secure attachment strategies in addressing attachment needs, insecure-avoidant and –resistant attachment strategies are considered organised behavioural strategies that are conditional on the caregiving environment. Attachment disorganisation, however, is characterised by a breakdown of organised attachment strategies when the attachment system is activated. This is thought to be the result of a conflict children are faced with, i.e. that the caregiver is at the same time a source of comfort and a source of alarm, resulting in a breakdown of strategies described as “fright without solution” (Hesse & Main, Citation1999). It is therefore likely that exploration would be impaired to the degree that the fear-system is activated either partially or altogether, meaning a general impairment of the child’s ability to play.

To our knowledge, the only study on the association between disorganised attachment and play is by McElwain et al. (Citation2003). They did not find an association between disorganised attachment and quantity of pretend play. The authors suggest more research about attachment disorganisation and play is needed, particularly in low-risk samples as the vast majority of studies on disorganised attachment has been carried out with high-risk samples.

The present study examined the role of early child attachment security and disorganisation at 18 months for toddler’s developmental play level and duration of pretend play at 30 months in a longitudinal study of a low-risk sample. We used the 12 Step Play Scale (Belsky & Most, Citation1981) to measure play. It has been used in a number of studies with various modifications (Belsky et al., Citation1984; Belsky & Most, Citation1981; Bornstein et al., Citation1992; McElwain et al., Citation2003; Meins et al., Citation1998) and consists of 12 steps of play: Steps 1–5 are increasing levels of functional play with no signs of pretend play, 6 indicates “approximate pretend activity but without confirming evidence,” and Step 7 and higher indicate increasing levels of pretend play (see Belsky & Most, Citation1981, for more details). The higher the level, the more developmentally advanced the child’s play is. We expected that children with higher attachment security would predict a higher level of play as well as a longer duration of pretend play (Hypothesis 1). We also expected that higher attachment disorganisation was associated with a lower play level and less pretend play (Hypothesis 2). We did not have any concrete expectations with regard to which specific level the child’s play would reach.

The child’s play was measured in four conditions with varying degrees of involvement from the mother (for further description see Procedure). In a play context where the mother is present, it could be possible that the child’s attachment relationship would affect their ability to play. We therefore wanted to explore how attachment security and attachment disorganisation would affect the child’s play in a play condition involving the mother compared to when the child played solitarily. As we did not have any hypotheses about these interactions between attachment and play conditions, we conducted those analyses in an exploratory manner.

Methods

Participants

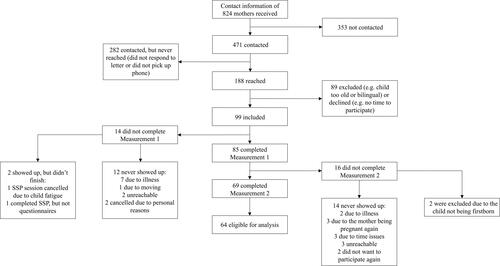

The sample and procedure have also been described in Stuart et al. (Citation2023). Mothers and children were recruited from the Copenhagen area in Denmark via registers from the National Board of Health. Inclusion criteria were: All mothers were primiparous; infants were full-term and had an Apgar-score > 6; all mothers and children were mentally and physically well; and Danish was the spoken language in the home. Dyads were predominantly Scandinavian and White, and the sample can be characterized as low-risk (high educational level, no illnesses and low percentage of single mothers; see for sample characteristics). 99 dyads were initially enrolled; 69 (68.3%) completed both visits (T1 at 1.5 years of age and T2 at 2.5 years, respectively) (see for detailed information on enrolment and exclusion). An additional five dyads were not included in the final sample because Danish was not the primary language (n = 2), lack of father’s consent (n = 1), mother had a psychiatric diagnosis (n = 1), and one child had a stomach ache during T2. This resulted in a total of 64 mother-child dyads (54.7% male children) included in the final analysis. Sample size calculation showed that in order to have 80% power at a significance level of 5% to detect a small-to-medium effect size (Cohen’s f2 of .02-.15, respectively), we would need between 55 and 395 participants. All mothers gave written and informed consent before entering the study. For all children, all parents with custody gave written and informed consent to participate. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (approval number: 2015/11). Dyads received a free package of LEGO DUPLO™ toys at both visits (approximate value of €20–30 per package).

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N = 64).

Procedure

Dyads visited the university laboratory when the child was 18 months (T1, M = 18.69, SD = 0.43) and one year later at 30 months (T2, M = 30.37, SD = 0.54). All visits were video-recorded. The children’s eating and sleeping patterns were taken into consideration at both visits so they were not overly tired or hungry during assessment. T1 typically lasted one hour in total and included assessment of attachment using the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP) (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978; Main & Solomon, Citation1990) and questionnaires not used in the current study.

T2 lasted approximately 1–1.5 h in total and included mother and child participating in a play procedure followed by an assessment of the child’s developmental status using the cognitive and language scales from the Bayley-III (Bayley, Citation2006). All children had a short break and snack between the play procedure and the Bayley. For the play setup, mother and child were seated on the floor in the laboratory, and four consecutive play trials took place. A variety of toys had been placed to be immediately accessible. The toys were of the brand DUPLO™ and consisted of: a two-storied playhouse with furniture (four chairs, a table, a sink, a bed, a drawer, a toilet, a bathtub); figures (a man, a woman, a happy boy, a sad boy, a happy girl, a sad girl, a prisoner, a policeman, a princess, two knights); animals (one baby cow, one mother cow, a crocodile, a knight’s horse); models of real life objects (a fire truck, a motorcycle, a slide, an ice cream cone, a cupcake, a chest, a sword, an axe, two flames, a suitcase, a pot, a watering can, a present); various blocks with prints (a toothbrush, a cereal bowl, milk, a cake, money, an alarm clock, a book, a cloud); and seven 2 × 2 blocks and ten 2 × 4 blocks of various colours. Four envelopes with instructions for each respective play trial were immediately accessible to the mother. Every play condition had a duration of five minutes, and mothers were instructed to open the next numbered envelope upon the experimenter knocking on a one-way-screen separating the experimental room and the welcome room. For the first condition, the child was instructed to play freely solitarily while the mother sat nearby reading a magazine. In the second play condition, the mother was instructed to sit next to the child and engage in free play naturally as they would do at home. In the third condition, the mother was asked to instruct the child to specifically play with the figures. Finally, in the fourth condition, the mother was instructed to read out a scenario involving the figures (“The figures are having a birthday party for the boy/girl, but he/she falls and hurts his-/herself on the slide.”). The mother then asked the child, “what happens next?” and participated in the child’s play as she thought appropriate.

Measures

Child attachment

Child attachment security and disorganisation were assessed at T1 (age range: 17.1–20.0 months) using the Strange Situation Procedure (SSP, Ainsworth et al., Citation1978). It is a standardised 20-minute laboratory observational procedure for children between 12 and 24 months. The parent and child are observed in a laboratory setting for eight brief episodes with the goal of looking at the child’s attachment behaviour, which is triggered through mild stress. In short, mother and child are placed in an unfamiliar room, a stranger enters, and the mother leaves the room twice. The child’s attachment behaviours are observed during the reunions. Children’s behaviour on reunion is coded on four behavioural scales (proximity seeking PS, contact maintenance CM, avoidance A, and resistance R) ranging from 1 (behaviour is not present) to 7 (behaviour is persistent and active). Based on the pattern of scores, a classification (A, B or C) is assigned. As such, secure attachment relationships (B) are characterized by a pattern of high PS and CM paired with low A and R. Insecure-avoidant (A) classification is characterized by low PS, CM and R, and medium-to-high A. Insecure-resistant (C) classification is characterized by high PS, CM and R, and low A. Disorganised behaviour (e.g. conflicted, disoriented, or fearful behaviour) is coded according to the Main and Solomon (Citation1990) manual scale ranging from 1 (disorganized behaviour is not present) to 9 (disorganized behaviour is strong, frequent, or extreme). A score of 5 or more qualifies for a disorganised classification.

Attachment behaviour was coded by a certified SSP coder (AT). For purposes of reliability, 16 of the 69 dyads who completed T2 (23.2%) were coded by a second certified SSP coder. Inter-coder agreement for ABCD-classifications was 81.3%, κ = .73. Instead of using the conventional classifications, we used a continuous score for attachment security based on Richters et al. (Citation1988) approach, later modified and validated by van IJzendoorn and Kroonenberg (Citation1990) and used in several studies (see Smith-Nielsen et al., Citation2016; Tharner et al., Citation2012). Higher scores reflect more attachment security (scores ≥ 0 indicate secure attachment). We also used the continuous disorganisation score in the analyses.

Child play

Play was assessed at T2 (age range: 29.2–31.6 months) using The 12 Step Play Scale (Belsky & Most, Citation1981). Children only move to a higher level in the play developmental sequence after lower levels have been attained (Belsky et al., Citation1984).

Since it took the mothers some time to read the instructions at the beginning of the four play conditions and in order to standardise the coding procedure, each coding was started one minute into each of the five minute conditions, resulting in four minutes to code for each of the four play conditions. All play conditions were segmented into 10-second intervals, and each interval was ascribed a code corresponding to the highest level of play exhibited by the child during this interval, resulting in 24 codes per condition per child. Play was coded from video recordings by a trained psychology student (primary coder). A total of 256 conditions (64 subjects x 4 conditions) were coded by the primary coder. Of these, 56 (22%) were randomly selected to make up a reliability set and coded by a second trained psychology student. Four out of the 56 conditions (7.1%) coded for reliability were afterwards consensus coded due to Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) values under 0.6, indicating a lower range moderate reliability (Koo & Li, Citation2016). An additional eight conditions (play data from two dyads) were consensus coded since they had been included in the pilot pool, but these conditions were not part of the reliability set. Inter-coder agreement for the reliability-coded conditions was 75.2%. Inter-rater reliability was calculated on a 10-second interval basis using ICC and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) based on a single measure, absolute agreement, two-way mixed effects model (Koo & Li, Citation2016) and showed a good-to-excellent inter-rater reliability, ICC = .85, 95% CI [.83; .86]. Cohen’s κ was .69, indicating good reliability.

Two variables were developed from the coded values: Developmental Play Level and Duration of Pretend Play. Developmental play level indicates the general play level in each episode and was calculated as the mean of the 24 codes per episode. The minimum and maximum scores on play level are 0 and 12 per condition, higher scores indicate higher level of play. In line with the procedure for measuring pretend play by McElwain et al. (Citation2003), duration of pretend play indicates how long the child engages in pretend play (code of 7 or higher) during the episode, ranging from 0 to 288.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS Statistics 28 (IBM, Chicago, IL). All analyses were performed on both dependent variables, Developmental Play Level and Duration of Pretend Play separately. As a large number of dropouts took place between the two visits, a binary logistic regression was done to assess whether maternal education predicted dropout status (yes/no). Maternal education was chosen, as research shows this to be one of the best indicator of socio-economic status (SES; Baker, Citation2014). Maternal education was dummy coded with lowest educational level as the reference group. We also tested whether maternal education and child language as measured with the Bayley-III (Bayley, Citation2006) should be included as covariates by testing their associations with the dependent and independent variables.

Generalized Estimating Equations was used to test all of the hypotheses. As the study design consisted of repeated measures (i.e. the four play conditions), a first-order autoregressive covariance structure (AR(1)) was chosen. A linear model was chosen. To test if attachment security predicted play level and duration of pretend play (hypothesis 1), attachment security was entered as the independent variable. These analyses were repeated to test whether attachment disorganisation predicted the play outcomes (hypothesis 2) with attachment disorganisation score entered as the independent variable. Finally, to test if associations were dependent on play condition (the explorative analyses), interaction effects between attachment security/disorganisation and play condition was entered. Play condition 1 (i.e. child solitary free play) was used as the reference group. All reported p-values are two-tailed and evaluated at a significance level of .05.

Results

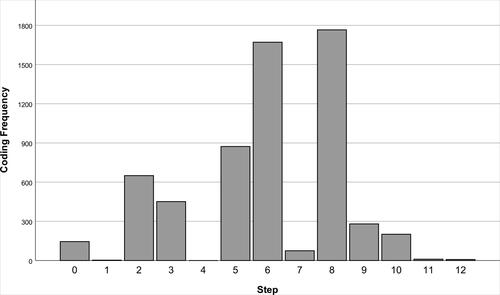

Descriptive statistics are presented in . Frequencies of play codes are presented in . Steps 6 and 8 of the 12 steps were the most frequently coded, indicating that the scale was appropriate for examining play development and the shift to pretend play in this age group. The amount of time where no play was exhibited was evenly distributed across the sample, with the highest frequency of no play for any child being nine intervals out of 96 possible. Step 1 (“mouthing”) was almost never coded as children had moved past this developmental stage. Step 4 (“bringing together two or more materials in a manner not intended by the manufacturer”; Belsky & Most, Citation1981, p. 632) was never coded, because the objects and blocks in the toy set generally structurally fit together (a quality which is characteristic of LEGO DUPLO™ toys). Step 7 (“pretend play on self”) was rarely coded, presumably because almost all of the toys were smaller than life size, thus not inviting this type of play. Steps 11 and 12 (“sequence pretend substitution” and “double substitution”) were rarely coded, as these types of play were too developmentally advanced for this age group (cf. Belsky & Most, Citation1981).

Figure 2. Coding frequencies of each step on the play scale based on a total of 96 codings for 64 child-mother dyads.

Due to the relatively large number of dropouts, a binary logistic regression model assessed whether maternal education at 18 months could predict dropout at T2. Maternal education was not a significant predictor of dropout status (all ps > .76), indicating that there were no significant differences in educational level between mothers who completed both visits and mothers who didn’t.

We checked whether maternal educational level and the child’s language were relevant covariates in the sample. Neither was significantly associated with the dependent variables (all ps > .12) or the independent ones (all ps > .27). They were thus not included in any of the subsequent analyses to maximise power.

Attachment security and play

Attachment security was significantly positively associated with play level (b = 0.08, Wald χ2(1) = 5.15, p = .023, 95% CI [0.01; 0.14]), meaning that higher attachment security predicted a higher developmental play level. There were no significant interaction effects of attachment security and play conditions on play level (all ps > .22). Thus, the association between attachment security and developmental play level was independent of the play conditions.

There was no significant association between attachment security on duration of pretend play (b = 2.34, Wald χ2(1) = 2.78, p = .096, 95% CI [-0.41; 5.08]). None of the interactions between attachment security and play conditions were significant (all ps > .18). Thus, play condition did not play a moderating role in the association between attachment security and duration of pretend play.

Attachment disorganisation and play

There was no significant association between disorganisation and play level (b = 0.04, Wald χ2(1) = 0.25, p = .62, 95% CI [-0.10; 0.17]). There was a significant interaction effect between disorganisation and play condition four (b = −0.15, Wald χ2(1) = 4.11, p = .043, 95% CI [-0.29; −0.01]). This indicates that the higher disorganization was, the child played on a lower developmental level only in the story stem play condition. None of the other interactions were significant (all ps > .14).

Disorganisation was not significantly associated with duration of pretend play (b = 0.55, Wald χ2(1) = 0.05, p = .830, 95% CI [-4.44; 5.53]). There were no significant interaction effects between disorganisation and play conditions (all ps > .14).

Discussion

The present study examined the role of infant-mother attachment for children’s play in a longitudinal study of a low-risk sample. We investigated whether attachment security and disorganisation at 18 months would predict developmental play level and duration of pretend play at 30 months.

Our first hypothesis was partly supported as we found a significant association between attachment security and play level but not duration of pretend play. This seems to be in line with previous research that found attachment security associated with higher play engagement with parents (Kerns & Barth, Citation1995) and positive play outcomes such as more exploration of the environment and looking at toys with a peer (Jacobson & Wille, Citation1986). Our result is also in line with attachment theory which predicts that securely attached children have a secure base in their mother from which they can explore and play. Thus, higher attachment security is thought to increase children’s freedom to allocate resources in exploration and play. This might explain our finding that higher attachment security was related to higher developmental levels of play. It is, however, surprising that we did not find an association regarding duration of pretend play as previous studies have found that secure attachment is related to more pretend play (Matas et al., Citation1978; McElwain et al., Citation2003). This may be explained by the fact that by using the attachment security score, we did not distinguish between insecure-avoidant and insecure-resistant children in our analyses. Previous studies indicate that insecure-avoidant attachment may be related to more exploration (Lewis & Feiring, Citation1989). Supporting this, McElwain et al. (Citation2003) found that only the children with insecure-resistant attachment relationships showed significantly less pretend play than children with secure and insecure-avoidant attachment relationships. However, as previously noted, more exploration does not necessarily equate to a higher developmental level of this play; theory and research seem to indicate that the play is more superficial in nature (Cassidy & Berlin, Citation1994; Groh, Citation2021), and studies would therefore benefit in assessing play both in its quantity and developmental level. Because the insecure groups were very small in our sample (nA = 7, nC = 5) and as we used the continuous attachment security score in order to maximise power, it was not possible to test the hypotheses for the separate insecure groups. As those groups were combined by using the security score, potential differences in pretend play between these groups may have cancelled each other out. Based on our theoretical considerations outlined in the introduction, one would expect that securely attached children show better play development than both insecure classifications. Attachment theory states that securely attached children are better able to use their caregiver as a secure base for exploration than children with either of the insecure classifications. As in addition, the security score better reflects subtle differences in attachment security than the categories, we chose here to use the security score. However, contrary to theoretical considerations, one empirical study indicates that only children with insecure resistant relationships show limited play development compared to children with secure attachment relationships (McElwain et al., Citation2003). It is a limitation of our present study that we cannot investigate whether this association is different for different insecure classifications and thus needs to be examined in larger studies with sufficient power to use the classifications.

Contrary to our second hypothesis, attachment disorganisation predicted neither developmental play level nor duration of pretend play. This result is in concurrence with, to our knowledge, the only previous study that has investigated such an association (McElwain et al., Citation2003). The authors attributed their null finding to the sample being low risk with regard to maternal education, income, partner status, time in day care, and ethnicity. Our sample can also be characterised as low-risk regarding the same factors. The results may therefore indicate that attachment disorganisation does not affect the child’s play in low-risk samples.

However, interestingly, we did find a significant interaction between attachment disorganisation and the story stem play condition for developmental play level but not for duration of pretend play in the explorative analyses. In the story stem condition, play was introduced with a short, emotional narrative by the mother. As mentioned in the introduction, attachment disorganisation theory posits that the attachment system may be activated more than usual due to experienced danger and alarm, thereby lowering exploration (cf. Bowlby, Citation1969; Hesse & Main, Citation1999, Citation2006) and the child may even experience shutdowns where play is not an option. However, it is only in the story stem play condition that this association between disorganised attachment and play level is seen. This may indicate that the short emotional narrative that the mother introduces at the start is the trigger for the decrease in play level for children with more disorganised attachment. A story stem is often used to open up for a conversation about feelings and can possibly reveal the child’s inner world as the child can narrate memories, hoped-for-events, feared scenarios, or even distancing themselves from the story stem by refusing the address it (Bretherton & Oppenheim, Citation2003; Emde et al., Citation2003). It may be that this story stem activates the attachment system and the mechanisms described for how disorganisation may impair play, especially if the narrative is not only emotional but also has attachment related themes. This would also be in line with story stem assessments of attachment which are used to activate the attachment system and observe differences in play (Bretherton et al., Citation2003; O’Connor & Gerard Byrne, Citation2007). Our results might thus be explained by the fact that the child is not able to play out an emotional narrative of the hurt child figurine possibly being comforted by the mother figure in the presence of the mother that the child has a disorganised relationship with and may not find a source of comfort. Thus, overall resulting in a lower developmental play level. We do not know if we would see the same moderation effect in non-emotional narrative play situations, and future studies should thus further investigate how play with a narrative and disorganised attachment is associated. However, the play context may thus affect whether or not attachment disorganisation affects play, and this needs to be taken into account in future studies on this topic.

We did not find any significant results for the rest of the explorative analyses on an interaction effect between attachment security and play conditions. This indicates that the child’s play does not depend on the degree or type of involvement of the mother in the play or on the context in which the play takes place. As such, the effect of the mother’s presence on the play of children with more secure attachment style seems to be of equal size across conditions. The previously mentioned positive association between play level and attachment security thus seems to apply across conditions, indicating that more securely attached children in general exhibit higher developmental levels of play. This might suggest that attachment security has a general impact on child development during the early years independent of different play contexts.

The findings of the present study should be considered in light of several limitations. A relatively large number of dropouts took place between inclusion and T1 and T2 (see ). This can be expected in longitudinal studies as well as for this population (first-time mothers just starting a family), but dropouts can bias the results if the missing data is not missing at random. However, our analysis of maternal education and dropouts indicated no apparent relationship between missingness and SES, suggesting that dropout happened in a non-systematic manner. We would have liked to further support this argument by investigating the relationship between dropout and attachment status, but due to funding and man-power limitations we only coded those participants who completed both visits. Another limitation is that the order of the play conditions was not counter-balanced, meaning that the story stem condition always came last in the test situation. We chose not to counterbalance, as we wanted the child’s solitary play to be unaffected by the other play conditions where the mother took part in the play. However, as our only significant finding was regarding the last play condition, it should be studied further whether the findings as well as the null-findings could be due to the order of play conditions. Lastly, the findings may not be broadly generalizable due to sample characteristics such as being low risk. As mentioned previously, it may be that the null-finding regarding the association between attachment disorganisation and play may be due to sample characteristics as also theorised by previous research (cf. McElwain et al., Citation2003). Future research should thus further explore the relationship between attachment and play in high-risk groups.

In sum, the findings of the present study point to a connection between the children’s early attachment security and disorganisation and play outcomes. The present study shows that higher mother-child attachment security is associated with positive play outcomes. From an attachment theory point of view, findings suggest that when children have a secure base to return to, they are more likely to play on a higher developmental level. The study also shows that attachment disorganisation is related to a lower developmental play level in a situation where the child and the mother play out an emotional narrative. From a theoretical point of view, this may indicate that when children do not feel safe in the relationship with their caregiver—as is the case with disorganised attachment—the play may be affected negatively and to some degree hinder the child’s ability to feel safe enough to let themselves play.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the families for their participation. The second author would like to thank the research assistants and everyone involved in collecting the data and executing the study overall.

Disclosure statement

The study was funded by the LEGO Foundation. Toys that were used in the study were donated by LEGO DUPLO™. The funding parties had no deciding power in connection to the design of the study and were not involved in the interpretation of the results.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- Ahloy-Dallaire, J., Espinosa, J., & Mason, G. (2018). Play and optimal welfare: Does play indicate the presence of positive affective states? Behavioural Processes, 156, 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beproc.2017.11.011

- Ainsworth, M. D. S. (1985). Patterns of infant-mother attachments: Antecedents and effects on development. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 61(9), 771.

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment. Erlbaum.

- Baker, E. H. (2014). Socioeconomic status, definition. In W. C. Cockerham, R. Dingwall, & S. R. Quah (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell encyclopedia of health, illness, behaviour, and society (pp. 2210–2214). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Bates, E. (1979). The emergence of symbols, cognition and communication in infancy. Academic Press.

- Bayley, N. (2006). Bayley scales of infant and toddler development. PsychCorp, Pearson.

- Belsky, J., Garduque, L., & Hrncir, E. (1984). Assessing performance, competence, and executive capacity in infant play: Relations to home environment and security of attachment. Developmental Psychology, 20(3),406–417. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.17.5.630

- Belsky, J., & Most, R. K. (1981). From exploration to play: A cross-sectional study of infant free play behavior. Developmental Psychology, 17(5), 630–639. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.17.5.630

- Bergen, D. (2013). Does pretend play matter? Searching for evidence: Comment on Lillard et al. (2013).

- Bergen, D., & Fromberg, D. P. (2021). Emerging and future contexts, perspectives, and meanings of play. In D. P., Fromberg & D. Bergen (Eds.), Play from birth to twelve and beyond (pp. 537–541). Routledge.

- Bernier, A., Beauchamp, M. H., Carlson, S. M., & Lalonde, G. (2015). A secure base from which to regulate: Attachment security in toddlerhood as a predictor of executive functioning at school entry. Developmental Psychology, 51(9), 1177–1189. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000032

- Bigelow, A. E., MacLean, K., & Proctor, J. (2004). The role of joint attention in the development of infants’ play with objects. Developmental Science, 7(5), 518–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7687.2004.00375.x

- Bigelow, A. E., MacLean, K., Proctor, J., Myatt, T., Gillis, R., & Power, M. (2010). Maternal sensitivity throughout infancy: Continuity and relation to attachment security. Infant Behavior & Development, 33(1), 50–60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2009.10.009

- Bornstein, M. H., Haynes, O. M., O'Reilly, A. W., & Painter, K. M. (1996). Solitary and collaborative pretense play in early childhood: Sources of individual variation in the development of representational competence. Child Development, 67(6), 2910–2929. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131759

- Bornstein, M. H., Vibbert, M., Tal, J., & O'Donnell, K. (1992). Toddler language and play in the second year: Stability, covariation and influences of parenting. First Language, 12(36), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/014272379201203607

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Basic Books.

- Bretherton, I., & Oppenheim, D. (2003). The MacArthur Story Stem Battery: Development, administration, reliability, validity, and reflections about meaning. In R.N. Emde, D.P. Wolf, & D. Oppenheim (Eds.), Revealing the inner worlds of young children: The MacArthur Story Stem Battery and parent-child narratives (pp. 55–80). Oxford University Press.

- Bretherton, I., Oppenheim, D., & Emde, R. N. (2003). The MacArthur story stem battery. In R.N. Emde, D.P. Wolf, & D. Oppenheim (Eds.), Revealing the inner worlds of young children: The MacArthur Story Stem Battery and parent-child narratives (pp. 381–396). Oxford University Press.

- Cassidy, J. (2008). The nature of the child’s ties. In J. Cassidy & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 3–22). Guilford Press.

- Cassidy, J., & Berlin, L. J. (1994). The insecure/ambivalent pattern of attachment: Theory and research. Child Development, 65(4), 971–991. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131298

- Damast, A. M., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., & Bornstein, M. H. (1996). Mother-child play: Sequential interactions and the relation between maternal beliefs and behaviors. Child Development, 67(4), 1752–1766. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131729

- Emde, R. N., Wolf, D. P., & Oppenheim, D. (2003). Revealing the inner worlds of young children: The MacArthur Story Stem Battery and parent-child narratives. Oxford University Press.

- Fein, G. G. (1979). Echoes from the nursery: Piaget, Vygotsky, and the relationship between language and play. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development, 1979(6), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.23219790603

- Fenson, L., & Ramsay, D. S. (1980). Decentration and integration of the child’s play in the second year. Child Developmment, 51(1), 171–178.

- Fiese, B. H. (1990). Playful relationships: A contextual analysis of mother-toddler interaction and symbolic play. Child Development, 61(5), 1648–1656. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130772

- Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1996). Playing with reality: I. Theory of mind and the normal development of psychic reality. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 77(Pt 2), 217–233.

- Ginsburg, K. R, the Committee on Communications, & the Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health. (2007). The importance of play in promoting healthy child development and maintaining strong parent-child bonds. Pediatrics, 119(1), 182–191. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2697

- Groh, A. M. (2021). Revisiting Ainsworth’s patterns of infant-mother attachment: An overview and appreciative critique. In A.M. Slater & P.C. Quinn (Eds.), Developmental psychology: Revisiting the classic studies (2nd ed., pp. 23–36). SAGE.

- Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Kindler, H., & Zimmermann, P. (2008). A wider view of attachment and exploration: The influence of mothers and fathers on the development of psychological security from infancy to young adulthood. In J. Cassidy & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 857–879). Guilford Press.

- Hesse, E., & Main, M. (1999). Second-generation effects of unresolved trauma in nonmaltreating parents: Dissociated, frightened, and threatening parental behaviour. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 19(4), 481–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/07351699909534265

- Hesse, E., & Main, M. (2006). Frightened, threatening, and dissociative parental behaviour in low-risk samples: Description, discussion, and interpretations. Development and Psychopathology, 18(2), 309–343. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579406060172

- Jacobson, J. L., & Wille, D. E. (1986). The influence of attachment pattern on developmental changes in peer interaction from the toddler to the preschool period. Child Development, 57(2), 338–347. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130589

- Kaufman, S. B., Singer, J. L., & Singer, D. G. (2012). The need for pretend play in child development. Psychology Today, 6.

- Kerns, K. A., & Barth, J. M. (1995). Attachment and play: Convergence across components of parent-child relationships and their relations to peer competence. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 12(2), 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407595122006

- Koo, T. K., & Li, M. Y. (2016). A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 15(2), 155–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcm.2016.02.012

- Lewis, M., & Feiring, C. (1989). Infant, mother, and mother-infant interaction behavior and subsequent attachment. Child Development, 60(4), 831–837. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131024

- Lillard, A. S., Lerner, M. D., Hopkins, E. J., Dore, R. A., Smith, E. D., & Palmquist, C. M. (2013). The impact of pretend play on children’s development: A review of the evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 139(1), 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029321

- Lowe, M. (1975). Trends in the development of representional play in infants from one to three years – an observational study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 16(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1975.tb01870.x

- Main, M. (1983). Exploration, play, and cognitive functioning related to infant-mother attachment. Infant Behavior and Development, 6(2–3), 167–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0163-6383(83)80024-1

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of an insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T.B. Brazelton & M.W. Yogman (Eds.), Affective development in infancy (pp. 95–124). Ablex Publishing.

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1990). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (vol. 1, pp. 121–160). The University of Chicago Press.

- Matas, L., Arend, R. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (1978). Continuity of adaptation in the second year: The relationship between quality of attachment and later competence. Child Development, 49(3), 547–556. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128221

- McCall, R. B. (1974). Exploratory manipulation and play in the human infant. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 39(2), 1–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/1166007

- McCune-Nicolich, L. (1981). Toward symbolic functioning: Structure of early pretend games and potential parallels with language. Child Development, 52(3), 785. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129078

- McElwain, N. L., Cox, M. J., Burchinal, M. R., & Macfie, J. (2003). Differentiating among insecure mother-infant attachment classifications: A focus on child-friend interaction and exploration during solitary play at 36 months. Attachment & Human Development, 5(2), 136–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/1461673031000108513

- Meins, E., Fernyhough, C., Russell, J., & Clark-Carter, D. (1998). Security of attachment as a predictor of symbolic and mentalising abilities: A longitudinal study. Social Development, 7(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00047

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Pereg, D. (2003). Attachment theory and affect regulation: The dynamics, development, and cognitive consequences of attachment-related strategies. Motivation and Emotion, 27(2), 77–102. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024515519160

- O’Connor, T. G., & Gerard Byrne, J. (2007). Attachment measures for research and practice. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 12(4), 187–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-3588.2007.00444.x

- Piaget, J. (1962). Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. Routledge.

- Richters, J. E., Waters, E., & Vaughn, B. E. (1988). Empirical classification of infant-mother relationships from interactive behaviour and crying during reunion. Child Development, 59(2), 512–522. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130329

- Shim, J. (2007). Low-income children’s pretend play: The contributory influences of individual and contextual factors. The University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

- Smith-Nielsen, J., Tharner, A., Krogh, M. T., & Vaever, M. S. (2016). Effects of maternal postpartum depression in a well-resourced sample: Early concurrent and long-term effects on infant cognitive, language, and motor development. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 57(6), 571–583. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12321

- Solomon, J., & George, C. (2008). The measurement of attachment security and related constructs in infancy and early childhood. In J. Cassidy & P.R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (pp. 383–416). Guilford Press.

- Spencer, P. E., & Meadow-Orlans, K. P. (1996). Play, language, and maternal responsiveness: A longitudinal study of deaf and hearing infants. Child Development, 67(6), 3176–3191. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131773

- Stuart, A. C., Gufler, S. R., Tharner, A., & Væver, M. S. (2023). Story stems in early mother-infant interaction promote pretend play at 30 months. Infant Behavior & Development, 73, 101893. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2023.101893

- Tharner, A., Luijk, M. P. C. M., Raat, H., Ijzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Moll, H. A., Jaddoe, V. W. V., Hofman, A., Verhulst, F. C., & Tiemeier, H. (2012). Breastfeeding and its relation to maternal sensitivity and infant attachment. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics: JDBP, 33(5), 396–404. https://doi.org/10.1097/DBP.0b013e318257fac3

- Valentino, K., Cicchetti, D., Toth, S. L., & Rogosch, F. A. (2006). Mother-child play and emerging social behaviors among infants from maltreating families. Developmental Psychology, 42(3), 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.3.474

- van IJzendoorn, M. H., & Kroonenberg, P. M. (1990). Cross-cultural consistency of coding the strange situation. Infant Behavior and Development, 13(4), 469–485. https://doi.org/10.1016/0163-6383(90)90017-3

- Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. Readings on the Development of Children, 23(3), 34–41.

- Waters, E., & Deane, K. E. (1985). Defining and assessing individual differences in attachment relationships: Q-methodology and the organization of behavior in infancy and early childhood. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 50(1/2), 41. https://doi.org/10.2307/3333826

- Whipple, N., Bernier, A., & Mageau, G. A. (2011). Broadening the study of infant security of attachment: Maternal autonomy-support in the context of infant exploration. Social Development, 20(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2010.00574.x