Abstract

This paper takes China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO)’s investment in the Piraeus Port as a case study to explore the development of the sensemaking of its CEOs in taking key strategic decisions. The extant literature assumes that decisions by CEOs of Chinese state own enterprises are informed by the interests of the State. This paper employs social constructionist organisation theory to investigate COSCO’s then CEO Wei Jiafu’s social interaction with various Chinese and Greek stakeholders from his multiple social identities in the Chinese corporate and political realms. It shows that the synergy of these identities was a driving factor behind the first encounters between Mr Wei and the Greek government officials and behind the initiation of the idea to invest in Piraeus during those first encounters. The following encounters gradually enlarged the critical mass of supporters for the investment, ending in the signing of the agreement.

1. Introduction

With the increasing Chinese outbound foreign direct investment (OFDI) in the European Union (the EU), infrastructure and logistics (harbours, airports, etc.) have become attractive industries for Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs). China Ocean Shipping Co. (COSCO)’s investment in the Greek port of Piraeus is a prominent case in this respect.

In 2008, COSCO Pacific Ltd. (a subsidiary of COSCO Group) successfully obtained a 35-year concession from the Greek government to operate Pier II as well as rebuild and operate Pier III in the port of Piraeus, involving an investment of €4.3 billion (Reuters Staff, Citation2008). COSCO launched its operation on October 1, 2009 (COSCO, Citation2009), and COSCO Shipping1 finally obtained the controlling stake with an investment of €368.5 million in 2016 (Stamouli, Citation2016).

Chinese investment in European infrastructure led to concerns that ‘the Chinese are buying up Europe’ among European politicians. The apprehension triggered by COSCO’s investment in the Port of Piraeus was strongly voiced by workers who were afraid of losing their jobs, and went on a 6-week strike with a banner written ‘COSCO Go Home!’ in 2009 (Smoltczyk, Citation2015). Moreover, COSCO’s active involvement in the Greek government’s plan for further privatisation of the Piraeus Port made some fear that Chinese investors were taking advantage of the Greek crisis (Batzoglou & Ertel, Citation2011). Some scholars even worried that Chinese investment in the Port of Piraeus not only aims to explore a new gateway for export to Europe (Mihalakas, Citation2011; Vamvakas, Citation2014), but also to seek a regional hub for the country’s geopolitical strategy (Dokos, Citation2013; Van der Putten & Meijnders, Citation2015), and even a port for potential military activities (Kynge, Campbell, Kazmin, & Bokhari, Citation2017). Those researchers take for granted that investment by a Chinese SOE must serve the political agenda of the national government (Godement, Parelle-Plessner, & Richard, Citation2011). Few studies analyse it from the perspective of Greek demand for development (Huliaras & Petropoulos, Citation2014; Psaraftis & Pallis, Citation2012).

This case has also received attention in China. Chinese media coverage considers the COSCO Piraeus project as the first pillar of China’s new Maritime Silk Road in Europe (Brinza, Citation2016; Zou, Citation2016), which is a part of One Belt One Road Initiative (Kampanis, Citation2017; Ma, Citation2015). Chinese academics often position it as a successful case of Chinese enterprises’ ‘going global’ (COSCO Report Team, Citation2011; Ren, Citation2015), again on the assumption of a strong relation between COSCO as an SOE and the Chinese government.

All these studies, Chinese and international, seem to assume that the main function of Chinese SOEs is to serve that state’s interests and execute the state’s policies. In that assumption, their CEOs are regarded as appointed by the state to act as stewards of the state assets. Concrete for our COSCO in Piraeus case, all research cited assumes that the Chinese government had at some time decided that it wanted to acquire influence in that port and had selected COSCO as the vehicle for that acquisition and therefore automatically given COSCO’s CEO the task to act as the State’s agent to finalise the deal.

This assumption is apparently so strong that extant studies ignore the influence of the role of the person of the CEO in this decision-making process. We look critically at this assumption from two angles. Our first criticism is towards the belief that the decision making is a completely conscious and rational process. In his seminal work on management decision making, Simon (Citation1977) presents decision making as comprising four principal phases: finding occasions for making a decision; finding possible courses of action; choosing among courses of action, and evaluating past choices’ (p. 40). Distinguishing these stages makes sense, but the choice of verbs seems to indicate that Simon regards each step as a conscious process. In social practice, people often do not ‘find’ an occasion for decision making, but run into such an issue in the course of social interaction. In a similar fashion, possible courses of action and the final choice of one of them can also take place gradually in ongoing social interaction.

Our second angle of criticism is that people engaged in a decision making process do so from multiple social identities. When we look at the role of Mr Wei Jiafu2 in this particular decision making, we assume that his actions in each of the four phases will be informed by his inclusions in a number of social-cognitive contexts; the most obvious being his role as CEO of COSCO and his functions in the political hierarchy. However, there could be more, then can be revealed through systematic research.

That COSCO is a SOE does not mean that it can be equalled to an administrative organisation like a tax office. It is also a commercial enterprise, which means that its CEO will define ‘opportunities’ in a different way from what the manager of a tax office would regard as opportunities. In a similar way, Mr Wei Jiafu’s decision making in his functions in the political hierarchy will not always serve the interests of COSCO, simply because he was its CEO. However, his being the of COSCO will always, to a larger or lesser extent, inform his decisions. To generalise this, all of Mr Wei’s decisions will be informed by a number of roles in various social contexts in which he is involved, but never by one single context. In each occasion of decision making, one particular context exercise a stronger influence than others, but that has to be established for each occasion of social interaction in the decision making process.

In this paper, we will study the various stages in the decision-making process regarding the idea for investing in the Port of Piraeus by analysing the social interaction of Mr Wei Jiafu with various Greek and Chinese individuals in the period from late 2005 to August 2008. We will apply the social integration (SI) model of social constructionist organisation theory (Peverelli & Verduyn, Citation2012). The SI model assumes that any decision people make is based on the way they make sense of the world and that the sensemaking of individuals is a product of ongoing social interaction with others in various social contexts. Applied to our case, we thus need to determine the relevant social contexts in which Mr Wei was active in the period under consideration and his social identity in each context. We can then try to reconstruct the decision in favour of investing in the Port of Piraeus as a combination of influences from those contexts.

In the remainder of this paper, we will first present a review of the current literature about the OFDI of Chinese SEOs and continue with an introduction to SI theory. Then we will analyse Mr Wei Jiafu’s social identities in the decision-making process, followed by his roles in various social contexts at the time of his meetings with the Greek government officials. Next, we will further discuss how the idea to invest in the Port of Piraeus came up as a possibility and gradually grew in importance by attracting the attention of more and more people, until a critical mass was reached. Finally, we will draw a conclusion and elaborate the limitation.

2. Literature review

With regard to OFDI by Chinese SOEs, the existing literature departs from various perspectives (Liang, Ren, & Sun, Citation2015; Sauvant & Chen, Citation2014; Wang, Hong, Kafouros, & Wright, Citation2012). The institution-based view seems to be the mainstream view for exploring OFDI (Buckley et al., Citation2007; Robins, Citation2013), focussing on the home countries’ institutional influences. Chinese SOEs are institutionally embedded in the economy by their ownership. They are business entities established and supervised by central and local governments (OECD Working Group, Citation2009). In the Chinese institutional framework, the state is still regarded as the most important pillar (Scott, Citation2002); while as assets of the Chinese government, SOEs also play a pioneer role in internationalisation. From this perspective, the OFDI of Chinese SOEs is often studied by exploring their interaction with the Chinese government. Chinese SOEs undertake OFDI for their own international business expansion, but are still subject to the (national or local) government’s instructions (Luo & Tung, Citation2007) or serve the government’s political or economic goals (Cui & Jiang, Citation2012; Ren, Liang, & Zheng, Citation2012). The Chinese government regards the international expansion of SOEs as important for accessing essential natural resources and seeking strategic assets (Buckley et al., Citation2007; Luo & Tung, Citation2007; Wang et al., Citation2012). SOEs are therefore often perceived as political actors (Cui & Jiang, Citation2012). The Chinese government has adjusted regulations regarding OFDI frequently during the past three decades, from tight control to encouragement by incentives. Since the Chinese government launched the ‘Going Global’ Strategy,3 Chinese SOEs have been encouraged to engage in overseas investment, referring to the ‘Outbound Catalogue Guidance’ issued by Chinese government, and obtaining direct financial support from their local government (Holtbrügge & Berning, Citation2014; Huang & Wilkes, Citation2011; Si, Citation2014).

From a micro-level perspective, the institution-based view stresses that Chinese SOEs’ international strategy is shaped and influenced by the institutional environment (Buckley, Cross, Tan, Xin, & Voss, Citation2008; Child & Rodrigues, Citation2005). Chinese SOEs are supported by their government and enjoy favourable treatment, while this is not always the case for non-SOEs. It is speedy government approval for OFDI and financial support from the home government that encourage Chinese SOEs to expand overseas (Gao, Liu, & Lioliou, Citation2015).

Another institutional connection between Chinese SOEs and the home government are their CEOs. The prominent status of SEOs has created a stratification among Chinese business managers along the ownership of their companies (Dickson, Citation2003). Liang et al. (Citation2015) point out that ‘the managers of SEOs are often directly appointed by the state, after having served as government officials’ (p. 224). In this way, the state can achieve its political and social objectives by granting incentives through the SOEs’ managers. Robins (Citation2013) even stresses it is one of the unique characteristics of Chinese OFDI that the major corporate policy decisions are influenced directly by the state through appointing most senior managers in SOEs. He points out that ‘the CEOs of the largest 54 “national” SOEs are appointed directly by the Organization Department of the Party and most of the others by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC)’ (p. 527). Through the downsizing of government agencies, a considerable number of officials have been given managerial jobs in SEOs. While that was meant to avoid high-level officials becoming unemployed, a side effect was that they retained their friendship ties with former colleagues who remained in office (Li, Yao, Sue-Chan, & Xi, Citation2011). Those personal ties are bound to have considerable influence on the individual sensemaking of strategic decisions by the CEOs, including those regarding OFDI. However, the influence of such social networks has so far never been studied.

To reveal the detailed process in which Mr Wei Jiafu decided to invest in the Port of Piraeus, we need to identify all relevant social inclusions of Mr Wei. Then, we can try to reconstruct the thought process from the birth of the idea to its realisation. We will employ the Social Integration model of social constructionist organisation theory for our analysis.

3. Social integration theory and social identity

3.1. Social integration (SI) theory

SI theory has been developed by researchers at Erasmus University Rotterdam using Weick’s organisation theory (Weick, Citation1979, Citation1995), enriched with concepts from postmodern philosophy, in particular Foucault and Derrida (Van Dongen, Citation1996) and concepts derived from psycholinguistics (Peverelli, Citation2000; Peverelli & Verduyn, Citation2012). SI theory focuses on the formation of social-cognitive groups as a result of people’s sensemaking of the world in ongoing social interaction. Social-cognitive groups are groups of people (social) bound by a shared view on reality (cognitive). The latter does not refer to the entire reality, but only to that part of reality relevant to the topic of interaction. Membership of a group is referred to as ‘inclusion’. People are included in a large, theoretically indefinite, number of groups, which is referred to as ‘multiple inclusion’. Two or more social groups are regarded as connected, if there is at least one person with inclusions in both. As soon as members of different groups start interacting about issues related to their groups, they form a new group, giving its members another identity. Some of such groups can gain a (semi-)permanent nature and become recognised as fully functional social groups. This is a key process in ongoing human social interaction. It is the motor of continuous social change in which groups dissolve and new groups are formed.

SI theory could be regarded an alternative social network model (Peverelli & Verduyn, Citation2012). Where mainstream social networks take individuals as the nodes of a network, social groups form the nodes in SI network graphs. Two social groups are linked if they have at least one member in common. An example would be a person P with two inclusions, Family and Work. P can introduce ideas from one inclusion to the other, thus enriching the sensemaking process. The strength of this model is that it not only indicates the relationships but also the nature of the relationships. Moreover, each inclusion refers to a number of people. For instance, ‘Family’ will include other family members, but in our mini-case, there is no information regarding the influence of a particular family member.

Applied to our research topic, we can use the same model to indicate how the decisions made by the CEO of a Chinese SOE will be based on the way that person makes sense of the world in his company inclusion, but can and usually will be moderated by a number of other inclusions. This study is the first time this model is applied to CEOs of Chinese SOEs. However, it has been applied to explain the decision making of Chinese private entrepreneurs (Peverelli & Song, 2012).

3.2. Social identity in a theory of social integration

In psychology, social identity is regarded as ‘a definition of who one is and a description and evaluation of what this entails’ (Hogg & Vaughan, Citation1995, p. 329). Moreover, identity is a social term, as your identity is what puts you apart from others. As a consequence, to construct an identity you need to identify what it is that sets you apart from significant others (Andersen & Chen, Citation2002; Cross & Vick, Citation2001). Davis (Citation2006) provides a sharp definition of the two issues of the problem of multiple identities of the same person.

How a single person can have different selves understood as a person’s different social identities:

How different persons can make up a single social group understood as their shared social identity.

In this paper, we concentrate on the individual level, through studying the construction of the different identities of the same person in different social groups. Social identity is not an innate trait of a person but constructed through ongoing social interaction in a specific social context. If you believe yourself to be the chief motivator of a certain group, then that perception must be supported by the behaviour of the other group members, allowing themselves to be motivated by you (Carsten, Uhl-Bien, West, Patera, & McGregor, Citation2010; Smircich & Morgan, Citation1982).

Applied to our case, we can use this model to identify Wei Jiafu’s social identities, so we can study how his various identities played a role in initiating the idea to invest in the Port of Piraeus (occasion to decision making) and developing that idea (finding possible courses of action and choosing among courses of action).

4. Data collection and research method

Our main research tool in this paper is making an inventory of the relevant inclusions of the key people involved in our case and how shared inclusions form a network on the basis of the SI model (Peverelli & Verduyn, Citation2012). This requires us to identify key actors and how, when and where they interacted. We first retrieved a corpus of media reports on meetings between representatives of COSCO and the Greek government from the media centre of COSCO’s official website in the period 2006–2008 (COSCO, Citation2017). These texts have been placed in order of the occurrence of the events in Chinese. That database is thus simultaneously a timeline of a series of events. For each event, we noted who was participating, in what social identity (inclusion), and how each event contributed to the formation or development of social-cognitive groups. These data were also checked with similar reports from other media.

We then conducted 10 interviews with relevant Greece and Chinese experts. Some of these have actively participated in the events studied in this paper. But most of them wish to remain anonymous, the data retrieved from those interviews enabled us to engage in triangulation to further check the findings.

The questions that guided interviews

What do you think COSCO‘s investment in Piraeus port?

How did the project start?

How was the situation of Greek government and Chinese government promoting the case?

When was your first time to hear COSCO?

How was the situation interacting with COSCO?

What role did President Wei Jiafu play in promoting the investment?

How did you perceive on his role?

What do you think this case brings to Greece? (Impacts)

How do you think the investment and COSCO‘s activity involved in building One Road One Belt initiative?

5. Analysis

Generally, decision making is the most significant activity engaged in by the managers in the enterprises, which is the most clear authority sign distinguish from the others. Hence, one aspect of investigating the role of the key individuals such as the managers is to explore his/her/their involvement in the decision-making process or flow. Especially, the managers or key individuals in charge play a crucial role in the process of making strategic decisions, which are ‘highly complex and involve a host of dynamic variables’ (Harrison, Citation1996, p. 46), just as the decisions of undertaking overseas investment. Thus, here we investigate the COSCO’s then CEO, Mr Wei Jiafu’s role by analysing his involvement in the decision-making process in investing in Piraeus port.

In a classic work on the science of management decision making, Simon (Citation1977) views it as a process synonymous with the whole process of management. For him, ‘decision making comprises four principal phases: finding occasions for making a decision; finding possible courses of action; choosing among courses of action, and evaluating past choices.’ (p. 40). The function of key individuals such as the managers or CEOs in the enterprises is revealed in this typical decision-making process flow, which could be generalised as initiatives, opportunities and feasibilities in short. However, just as we introduced above, in social practice, the decision-making is formed gradually in the process of social interaction in various social contexts rather than ‘found’. This perspective provides a clue to investigate how Mr Wei Jiafu’s various identities played a role in initiating the idea to invest in Piraeus (initiative and occasion to decision making) and further developing the idea (finding possible courses of action and choosing among the courses of action). Therefore, we will apply it in the analysis below.

5.1. The initiatives of investing in Piraeus: Wei Jiafu’s pre-Piraeus social identities

When we look back to the beginning of the course of events in the case of COSCO’s investment in Piraeus, we find that COSCO as a shipping company was interested in the Piraeus port in early 2005 for its international layout. This motivation for profit was revealed as the initiative in the manager’s decision-making process, which is reflected from Mr Wei Jiafu’s inherent social identities.

5.1.1. Firm identity

With his professional inclusions stemming from nearly 20 years of sea-faring experience, and a doctoral degree in shipping design, Wei Jiafu has rich knowledge in international shipping management and operation. After his appointment as President of the COSCO Group in 1998, during the Asian financial crisis, he first devoted himself to leading COSCO to overcome the financing difficulties and then turned to the internationalisation process (Xiao, Citation2011). Under Wei’s leadership, COSCO became one of the most successful SOEs in the wave of ‘going out’. Starting from obtaining the operation rights in the Long Beach Port in South California of the USA in 2001, COSCO became the fifth largest multinational shipping enterprise in the world, with more than 1000 companies and branches in over 50 countries and regions which contribute half of the total turnover (COSCO Group, Citation2015).

Wei played an important role in the decision-making related to COSCO’s investment in the port of Piraeus. Operating its own main port in Europe was entered in COSCO’s international agenda in early 2005. The strategic geographic position of the port of Piraeus is attractive to COSCO. Piraeus is a primary transshipment port close to the European market and emerging new markets in Turkey, serving Eastern Europe, the Mediterranean, the Balkans and Black Sea (Mihalakas, Citation2011). By investing this container port, ‘COSCO could create its own hub in the Mediterranean, which would facilitate developing transit service and reduce costs, improve efficiency of logistics and expand the global network of container port business’ (COSCO Staff, 2015). However, there was also some apprehension about the risks of the investment in Greece because of its small economic scale. Moreover, the efficiency of the port was extremely low, the equipment was out-dated and 90% of equipment operators lacked expert training (COSCO Report Team, Citation2011). While Piraeus was a top contender, it was clearly lacking technology and advanced management experience (PCT staff, Citation2015). President Wei, instead, was aware of the real value of the port. ‘The port of Piraeus is the biggest port in Greece, and it is a transit port to connect the markets in the Mediterranean area, West Asia, Central and South Europe as well in North Africa, which has big commercial value. We are determined to win it’ (COSCO Report Team, Citation2011). In this sense, Mr Wei as the CEO of COSCO, was the key individual who raised the initiative of investing in Piraeus and also made the decision to promote the investment for the firm’s international layout and to pursue the firm’s commercial profits.

5.1.2. Political identities

As stated earlier, there is a common belief that SOEs are owned and controlled by the government, serving the government’s policies (Ren, Liang, & Zheng, Citation2010), and are receiving government support (Szamosszegi & Kyle, Citation2011), including in their overseas investment (Buckley et al., Citation2008; Huang & Wilkes, Citation2011; Voss, Buckley, & Cross, Citation2009). As the largest SEO in the shipping industry, COSCO has an important strategic position in China’s economy. The shipping industry is one of strategic industries concerning national security and national economic lifelines in China, which should be absolutely controlled by the state (Ren & Liu, Citation2006). In 2010, the top three SOEs (COSCO, Sinotrans and China Changjiang National Shipping (Group) Corporation, and China Shipping (Group) Company) account for more than half of the revenue of the shipping industry (Szamosszegi & Kyle, Citation2011, p. 37). The CEOs of these three companies will form a social-cognitive group in which they are included, as they will interact regularly in various political meetings.

Chinese society uses rank to gauge social status (Li et al., Citation2011). SEOs operating directly under the national government are divided into three categories: ministerial level (zhengbuji 正部级), vice-ministerial level (fubuji 副部级), and departmental level (zhengtingji 正厅级). The CEOs of those companies are given the rank of minister, vice-minister and head of department, respectively. These ranks are not related to a specific ministry, but indicate their status in the Chinese political hierarchy (Leutert, Citation2016). COSCO is a SEO of vice-ministerial level, and its CEO is attributed the rank of Vice-Minister. We will refer to this with the term ‘conceptual Vice-Minister’ to distinguish it from acting vice-ministers. Wei Jiafu thus played an important role for COSCO (company inclusion) while interacting with Chinese government officials on that level (political inclusion).

From his inclusion in the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), Wei was elected member of the CCP Central Committee for Discipline Inspection in 2002 and 2007 at the 16th and 17th CCP National Congress (COSCO, Citation2013). These multiple inclusions placed him in a beneficial position for ensuring that COSCO’s development fitted the direction of the development of the State, securing support from the central government for COSCO’s internationalisation strategy. The personnel of central SOEs is ‘under the jurisdiction of the CCP Central Organisation Department’, the department in charge of a cadre rotation system that directly appoints all the top leaders of vice-ministerial-level enterprises (Wang, Citation2014, p. 659) like COSCO. In the evaluation system, senior executives are rewarded on their financial performance (Szamosszegi & Kyle, Citation2011). They, therefore, will align their direction and targets with those of the government for the sake of further promotions (Brockman, Rui, & Zou, Citation2013). This trait of top leaders of Chinese SOEs demonstrates how deeply they are embedded in China’s political institutions. President Wei confirms this in an interview on how to be a good entrepreneur. For him, a successful entrepreneur is trying to be a politician, ‘learning to do things from a political angle, both in terms of managing the enterprises and making decisions based on the guidelines set by local government and conform to the trends of the time’ (Editorial, Citation2006, p. 95).

We contend that the driving force behind the final decision to invest in Piraeus is the personal motivation of the individual decision maker, President Wei Jiafu. This paper will therefore focus on how the idea to invest in Piraeus came up and gradually gained critical mass through the ongoing social interaction of Wei Jiafu with various Greek stakeholders and key managers within COSCO. It will be useful to summarise Mr Wei’s relevant inclusions as shown in .

Table 1. Mr Wei Jiafu’s social identities Pre-Piraeus.

5.2. The social constructions of COSCO-Piraeus

To reconstruct how the idea for COSCO’s investment in Piraeus started and gradually developed in the course of that interaction, we conduct an analysis of social interaction between Wei Jiafu and various Chinese and Greek actors in the period 2005–2006. After reviewing the collected data, we found two main events providing a significant context of social construction of President Wei’s roles for COSCO’s investment in Piraeus Port. They are

The work visit to China by Mr Evripidis Stylianidis, Greek Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs for Economic Cooperation and Development in the end of 2005;

The official visit to China by Greek Premier Costas Karamanlis in January 2006.

From these two meetings, we can learn the Greek governmental officials’ reactions on Mr Wei Jiafu’s social identities, while the process of social construction also presented Mr Wei’s efforts on finding possible chances to take actions to promote the investment in Piraeus.

5.2.1. Stylianidis’ visit

Mr Evripidis Stylianidis, the then Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs for Economic Cooperation and Development, has granted a generous amount of time for an interview and allowed us to freely cite him (Stlylianidis, Citation2017). Most of the contents of this section have been derived from that interview.

He stated that Greece was then following a foreign policy of ‘looking East’, in particular: The Black Sea Area, Turkey, Russia, Ukraine. The Prime Minister proposed to extend that to China, as the two countries already had extensive commercial and cultural relations. Moreover, Italy, another Mediterranean nation, was also intensifying its contacts with China and the Greek Premier feared that the Italians beat the Greek in winning the most interesting Chinese opportunities.

To execute the new policy, Mr Stylianidis organised a work visit to China with a number of Greek ship-owners. The latter already had personal networks in China, as they were buying ships from China and transported Chinese goods all over the world. In terms of the SI model, Mr Stylianidis was included in the group of ship owners from his political function, and in the then Greek cabinet as the Vice-Minister responsible for international economic cooperation. He used this multiple inclusion to link the Chinese network of the Greek ship owners to the new political agenda of the cabinet.

Mr Stylianidis recounts that the discussions with various Chinese parties were not restricted to economic and commercial topics. The shared long history was also stressed. He knew about the Chinese policy of the New Silk Road and the Belt and Road Initiative and pleaded that those roads would also call at Greece. A highly interesting anecdote indicating the positive ambiance is that the Chinese are the only nation whose designation for ‘Greece’ was based on the Greek name for their nation ‘Hellas’ (Xila 希腊 in Chinese). This joint sensemaking has clearly constructed a social cognitive group from which the Deputy Minister still derives an identity.

Mr Stylianidis also met Mr Wei during this visit. He mentioned that the Greek ship owners already had contacts with COSCO, which helped in getting high-level meetings during their visit at the end of year 2005. Mr Stylianidis vividly recalls that ‘Captain Wei at that time was the President and CEO of COSCO… And I think he was very high in the position in the Communist Party of China. So, he was a very influential guy’. Earlier in the interview, Mr Stylianidis mentions that ‘We did not participate in a political discussion. We met him as a manager’. He continues praising Mr Wei’s intelligence, referring to Wei as ‘a key person in creating the contract’ (investing in the Port of Piraeus). Towards the end of that section, referring to Prime Minister Karamanlis’ official visit (see the following section of this paper), he points out that ‘after the official visit of our Prime Minister Mr Karamanlis, the bilateral relation became better and better. And out of the changes in China, we continued, our country, to have this good relations’. Back to our model, Mr Stylianidis once more shows that he has an intuitive feeling for multiple inclusions, sensing that Mr Wei’s firm and political identities created strong synergy. In fact, as Vice-Ministers, Mr Stylianidis (actual) and Wei (conceptual) were of the same rank.

5.2.2. Karamanlis’ visit

The Greek Prime Minister Kostas Karamanlis visited China in January 2006, the Chinese government arranged a meeting between him and Mr Wei Jiafu on 20 January. The Greek Minister of Foreign Affairs, the Chairman of the Greek Ship Owners Association and the President of the Port of Piraeus also attended (COSCO, Citation2006a).

Including the President of the Port of Piraeus was an obvious sign that Mr Karamanlis had Piraeus on his agenda. The Chinese government would, therefore, want to include someone from the Chinese maritime world on the list of prominent Chinese to meet with him. In view of Chinese political practice, potential candidates should also be people relatively close to the central government. COSCO was a major state owned (= close to the government) shipping (= maritime) company, so the company’s then CEO, Mr Wei Jiafu, with the bureaucratic rank of conceptual Vice-Minister, emerged as a natural candidate.

We interviewed one of the high-ranking Greek officials present during that meeting, who preferred to do so anonymously (Greek Government Official, Citation2017). We are consistently referring to him with ‘the official’ in this section. He shared an inclusion in the Greek cabinet with Mr Stylianidis. We can assume that Mr Stylianidis had briefed him extensively about his earlier visit to China. This is reflected in a number of similar words and phrases in both interviews. For instance, the official also mentioned that China and Greece not only have good relations in the shipping business but also share a rich historical heritage. The official was not included in the Greek Shipping business, which explains why Mr Wei’s firm identity does not play a prominent role in his story of the meeting, though he does mention that Mr Wei was an influential political person. However, what struck this official most were Mr Wei’s open personality, speed, and efficiency. He remarks that ‘Personally, he (Mr Wei) is very friendly, open, easy-going, full of humour, and easily to become a friend. Through the interactions, we have a very good personal relationship’. And follows with: ‘Besides, I am very impressed by him. He managed this big company, and made quick decisions. We were surprised the project went so quickly’. This impression is confirmed in the interview with a high-level policy advisor of then-Greek government, stating ‘the deal went very quickly and practical, which was surprised us’(Greek Government Policy Advisor, Citation2017). The official also added that ‘We know he has influence in the Chinese government, but he is the man that made decision. And he made fast decisions and helped to promote it very quickly. He was very positive in promoting the agreement’.

The interview reveals that Wei’s political and firm identities played a role in the counterparts’ cognition. We will analyse the social interaction during both meetings using the SI model, making an inventory of the main social-cognitive groups involved. We will then identify how what happened in one group influenced what happened in other groups through the multiple inclusions of key persons. Compliant with the conventions of the SI model, we will mark names of social cognitive groups with initial capitals. Once this has been done for both meetings, we can place the events in temporal order to reconstruct the social construction of the idea of COSCO’s investment in the Port of Piraeus.

5.2.3. Social interaction during Stylianidis’ visit

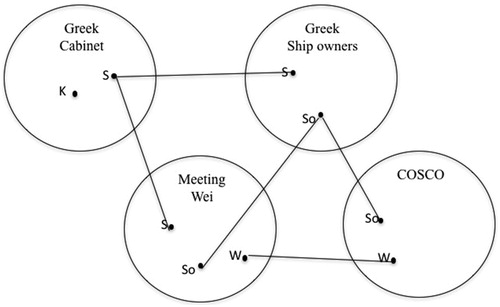

Mr Stylianidis was a Vice-Minister in the Greek Cabinet. We do not enter all (vice-) ministers in the graph, as the typical composition of a European cabinet is common knowledge. We only add the Prime Minister, as his suggestion to look further to China is indicated in Mr Stylianidis’ interview. Mr Stylinidis had good contacts in the Greek Ship-owners circles and the Greek Ship-owners had good relations with COSCO. A group of the same type of persons can be represented by one of them in the graph, so ‘SO’ refers to the group of Greek ship-owners. A meeting like that with Mr Wei during this visit is also a type of social interaction, and therefore constructs a social-cognitive group, which we will name: ‘Meeting Wei’. This group is placed in the centre of the graph indicating that it is the focus of our analysis. The situation right after the meeting with Mr Wei during Stylianidis’ visit is represented in .

5.2.4. Social interaction during Karamanlis’ visit

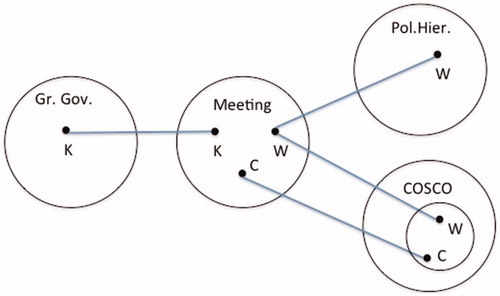

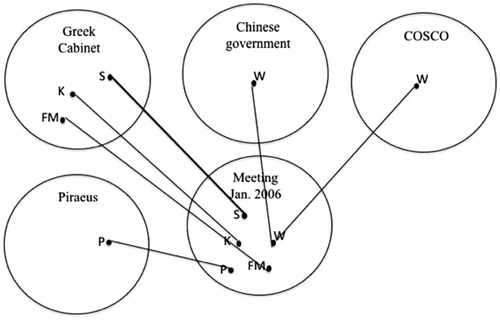

The Greek Cabinet also plays a role in this visit. It therefore reappears and we need to add the Foreign Minister, who attended the meeting. Mr Stylianidis attended as a prime source of information in the Greek Cabinet group. Mr Wei participated from his Government and COSCO inclusions. The President of the Port of Piraeus has a somewhat peripheral role in this meeting. He is mentioned in the COSCO press release, but not in the interview with the high-level Greek official. Once more, this meeting constructed a social-cognitive group that we will name ‘Meeting Jan. 2006’. This group is placed in central position, indicating that it is the focus point of our analysis. The graph is represented in .

Figure 2. Graphic representation of the meeting between Mr Karamanlis and Mr Wei (S: Mr Stylianidis; K: Mr Karamanlis; W: Mr Wei; FM: Greek Foreign Minister; P: President of the Port of Piraeus).

When we observe the graphs of both meetings together, and look for actors with shared multiple inclusions, it is clear that besides President Wei, Mr Stylianidis is another key actor, because they participated in both meetings as the connectors. Both gentlemen stand out as people apt in bringing different groups of people together to create synergy to realise ideas. However, while Mr Wei mainly participated in the first from his firm inclusion, he participated in the latter from his firm and political inclusion.

5.2.5. Further social interaction

When the decision was made, the manager would take actions to promote it realised, which is the process of feasibility. Specifically, the Styliandis’ visit seeded the idea that COSCO, and other parties involved, would benefit from COSCO’s investment in Piraeus, while the idea itself sprouted in the Karamanlis meeting, which became an important case for bilateral cooperation involved in the Sino-Greek Joint Statement on Establishing a Comprehensive Strategic Partnership (Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC, Citation2006). From then on, that meeting was followed by several more, alternatingly in Greece and China, gradually involving more and people, representing a growing number of social-cognitive groups at both sides (see ).

Table 2. Meetings between COSCO and Greek Government (2006–2008).

We will refrain from analysing each meeting to the same level of detail as we have done above for the first two, but will highlight one detail, that can be regarded as a sub-timeline: the growth of the Pireaus configuration within COSCO. Mr Wei visited Greece as a member of a Chinese delegation including in July 2006. He brought along Vice-Chairman Chen Hongsheng (COSCO, Citation2006c). Within COSCO Mr Wei as a single actor did not constitute a group. With Mr Chen added, a Piraeus configuration was started. We see Mr Chen reappeared during a meeting between Mr Wei with a Greek delegation in October 2006 (COSCO, Citation2006b) (see as an example). There is another Greek visit to China in May 2007 and Mr Wei then included Vice-Chairman Zhang Liang (COSCO, Citation2007). During a Greek visit to China in August 2008, Mr Wei brought along Vice-Chairmen Chen Hongsheng and Xu Lirong (COSCO, Citation2008). All these additions strengthened the Pireaus configuration in the COSCO Board and gave the other inclusions of the Vice-chairmen access to that configuration. This again displays the strong explanatory powder of the methodology of analysing and social development by following the development of inclusions of key people. It also gives a more detailed insight in how decisions of groups, even as large a corporation like COSCO, are embedded in the social interaction of the key individuals involved.

6. Discussion and conclusion

From the analysis above, we can conclude that President Wei’s pivotal role in the process of identifying a European port for COSCO’s investment was based on his inclusions in the company and the political hierarchy, and the informal inclusions constructed in his ongoing interaction with Greek counterparts.

Specifically, Mr Wei’s firm identity formed the initiative for investing in the Port of Piraeus after the evaluation of the strategic position of the port in COSCO’s international layout. Meanwhile, his political identity is a conceptual Vice-minister as CEO of an SEO in a pillar industry. He represents the relatively small group of old league managers of Chinese SOEs, who had been appointed on the basis of good performance, in the professional as well as in the political realm. As the CEO of a vice-minister-level SOE, his status of conceptual Vice-minister was a powerful resource in making that transition to a successful CEO. His two identities were socially integrated in the process of interaction with Greek counterparts.

Through the analysis above, we can see that Mr Wei was aware of his different social identities and kept access to all his inclusions open at all occasions, which is revealed from his social interaction in the first two meetings. Moreover, he also kept all his inclusions open to others who showed interest. He could therefore function as a connector of groups of people that, once connected, were able to continue and develop that connection. This connecting of groups does not always take place deliberately, based on some grand design. It is more often based on instinct, or on a haphazard basis.

An interesting finding of our research is that by strictly following the methodology of the SI model, we could identify Mr Stylianidis as another key individual, who played an important role as a connector to promote COSCO’s investment in Piraeus Port.

Therefore, through the analysis on Mr Wei Jiafu’s and Mr Stylianidis’ social identities and social integration of those identities, we can gain insight in the individual level social processes in which the idea for COSCO’s investment in Piraeus was initiated. It shows that it was forged by combining Greek and Chinese personal networks, rather than as a deliberately strategic action. The above analysis also provides a new perspective for understanding OFDI of Chinese SOEs. Existing research on decision making in this field concentrates on the role of the government and the role of the enterprises as instruments of the government. We acknowledge that SOEs are usually still the first choices for the Chinese government’s strategic OFDI; however, the literal meaning of ‘state-owned’ has changed considerably during the decades of economic reform. The older term guoying qiye(国营企业) ‘enterprises run by the State’ has been replaced by guoyou qiye (国有企业) ‘State owned enterprises’. This change confirms that the State no longer regards itself as the party engaged in the day-to-day operation of the SOEs, but as the owner, who delegates the management to professional managers.

Hence, although this paper is based on a single case study, we believe this is a strong proof that research into any aspect of the operation of Chinese SOEs should allocate more attention to the persons of the Chinese managers involved. In this sense, it opens the black box of the decision-making process in Chinese SOEs, which contributes to understanding Chinese SOEs’ behaviour from the aspect of the pursuit of commercial profits.

7. Limitations and future research

This paper is limited in a number of aspects. It is based on one single case, though one of major importance. The research method developed in this study should be applied to a number of other similar cases, to see to what extent the new findings corroborate ours. Although the number of texts in the corpus is large, they have been mainly extracted from one source. Data from additional sources and in-depth interviews with relevant people should generate valuable control data.

However, we believe that the research method developed in this research is mature enough to apply it to leaders of other Chinese SEOs with substantial overseas investments. The next step could be to extend the application to leaders of large private Chinese corporations to explore how their set of inclusions has contributed to strategic decisions related to foreign investments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yuan Ma

Yuan Ma is a Ph.D candidate in Political Science in the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. Her doctoral research is about Chinese investment in the European Union: motivations, strategies and impacts. Her research interests are transnational political economy, European Studies, and Chinese enterprises in the context of globalisation.

Peter J. Peverelli

Dr. Peter J. Peverelli is affiliated with the School of Business and Economics of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He has a Ph.D Literature from Leiden University and a Ph.D Business Administration from Erasmus University Rotterdam. He specializes in organisation theory and has published research on Chinese corporate identity and Chinese entrepreneurship.

Notes

1 On 4 January 2016, COSCO and China Shipping were merged into China COSCO Shipping Corporation Limited.

2 Mr Wei Jiafu (魏家福) had been the President and CEO of COSCO between November 1998 and July 2013. In this paper, we call him President Wei.

3 In 2001, the ‘Going Global’ strategy was made an official part of the 10th Five-year Plan (2001–2005) during the National People’s Congress. In the plan the Chinese government ‘encouraged outward investment that reflect China’s competitive advantages, and expand the areas, channels and methods of international economic and technology cooperation…. encourage capable enterprises to operate overseas and grow globally’ (Bernasconi-Osterwalder, Johnson, & Zhang, Citation2013, p. 2).

References

- Andersen, S.M., & Chen, S. (2002). The relational self: An interpersonal social-cognitive theory. Psychological Review, 109, 619–645. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.109.4.619

- Batzoglou, F., & Ertel, M. (2011, 16 November). Chinese investors take advantage of Greek crisis. Retrieved from http://www.spiegel.de/international/europe/good-friends-are-there-to-help-chinese-investors-take-advantage-of-greek-crisis-a-797751.html

- Bernasconi-Osterwalder, N., Johnson, L., & Zhang, J. (2013). Chinese outward investment: An emerging policy framework: A compilation of primary sources. Winnipeg, Canada: International Institute for Sustainable Development and Institute for International Economic Research. Retrieved from http://www.iisd.org/pdf/2012/chinese_outward_investment.pdf

- Brinza, A. (2016, April 25). How a Greek port became a Chinese ‘Dragon Head’. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2016/04/how-a-greek-port-became-a-chinese-dragon-head/

- Brockman, P., Rui, O.M., & Zou, H. (2013). Institutions and the performance of politically connected M&As. Journal of International Business Studies, 44, 833–852. doi:10.1057/jibs.2013.37

- Buckley, P.J., Clegg, L.J., Cross, A.R., Liu, X., Voss, H., & Zheng, P. (2007). The determinants of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Journal of International Business Studies, 38, 499–518. doi:10.2307/4540439

- Buckley, P.J., Cross, A.R., Tan, H., Xin, L., & Voss, H. (2008). Historic and emergent trends in Chinese outward direct investment. Management International Review, 48, 715–747. doi:10.1007/s11575-008-0104-y

- Carsten, M.K., Uhl-Bien, M., West, B.J., Patera, J.L., & McGregor, R. (2010). Exploring social constructions of fellowship: A qualitative study. The Leadership Quarterly, 21, 543–562. doi:10.1016/j.leaqua.2010.03.015

- Child, J., & Rodrigues, S.B. (2005). The internationalization of Chinese firms: A case for theoretical extension? Management and Organization Review, 1, 381–410. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8784.2005.0020a.x

- COSCO. (2006a, January 20). 希腊总理在京会见中国远洋魏家福董事长. Retrieved from http://cn.chinacosco.com/art/2006/1/20/art_895_24869.html

- COSCO. (2006b, October 25). 魏总裁会见希腊经济财政部长. Retrieved from http://www.cosco.com/art/2006/10/25/art_40_10057.html

- COSCO. (2006c, July 27). 魏董事长拜会希腊总理. Retrieved from http://cn.chinacosco.com/art/2006/7/27/art_895_24908.html

- COSCO. (2007, May 13). 魏总裁会见希腊外长芭戈雅妮. Retrieved from http://www.cosco.com/art/2007/5/13/art_40_10209.html

- COSCO. (2008, August 7). 魏总裁会见希腊外长. Retrieved from http://www.cosco.com/art/2008/8/7/art_40_10969.html

- COSCO. (2009, October 9). COSCO Pacific Commenced 35-year Concession in Relation to Piers 2 and 3 of Piraeus Port. Retrieved from http://en.chinacosco.com/art/2009/10/9/art_1076_35540.html

- COSCO. (2013, April 15). The Profile of Wei Jiafu. Retrieved from http://en.cosco.com/art/2013/4/15/art_766_35375.html

- COSCO. (2017, March 31). Corporation news of COSCO. Retrieved from http://cn.chinacosco.com/col/col895/index.html

- COSCO Group. (2015). Introduction of COSCO Group. Retrieved from http://en.cosco.com/col/col771/index.html

- COSCO Report Team. (2011). "走出去"战略发展模式的创新之路——中远希腊比雷埃夫斯港集装箱码头项目启示录. [Theroad of 'Going Global' strategy: inspiration of Piraeus Container Terminal S.A.]. 中国远洋航务(2), 32-36.

- COSCO Staff. (2015, August 24) Personal interview with one COSCO Staff/Interviewer: Y. Ma. COSCO's Investment in the Piraeus Port, Beijing.

- Cross, S.E., & Vick, N.V. (2001). The interdependent self-construal and social support: The case of persistence in engineering. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 27, 820–832. doi:10.1177/0146167201277005

- Cui, L., & Jiang, F. (2012). State ownership effect on firms' FDI ownership decisions under institutional pressure: A study of Chinese outward-investing firms. Journal of International Business Studies, 43, 264–284. doi:10.1057/jibs.2012.1

- Davis, J.B. (2006). Social identity strategies in recent economics. Journal of Economic Methodology, 13, 371–390. doi:10.1080/13501780600908168

- Dickson, B.J. (2003). Red capitalists in China: The party, private entrepreneurs, and prospects for political change. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dokos, T. (2013, July 10). The geopolitical implications of Sino-Greek relations. Retrieved from http://www.clingendael.nl/publication/geopolitical-implications-sino-greek-relations-0?lang=nl

- Editorial. (2006). Shipping cargo globally, earning credit internationally: An interview with Wei Jiafu, President and Chief Executive Officer, China Ocean Shipping (Group) Company (COSCO), Beijing’. Leaders Magazine, 29, 94–95. Retrieved from http://www.leadersmag.com/issues/2006.2_apr/091e292chi.pdf

- Gao, L., Liu, X., & Lioliou, E. (2015). A double-edged sword: The impact of institutions and political relations on the international market expansion of Chinese state-owned enterprises. Journal of Chinese Economic and Business Studies, 13, 105–125. doi:10.1080/14765284.2015.1021131

- Godement, F., Parelle-Plessner, J., & Richard, A. (2011). The scramble for Europe. Retrieved from http://www.ecfr.eu/page/-/ECFR37_Scramble_For_Europe_AW_v4.pdf

- Greek Government Official. (2017, December 5). Personal interview with a former high-level Greek Government Offical on COSCO's investment in Piraeus Port/Interviewer: Y. Ma.

- Greek Government Policy Advisor. (2017, December 5). Personal interview with a former policy advisor for former Greek Government on COSCO's investment in Piraeus Port/Interviewer: Y. Ma.

- Harrison, E.F. (1996). A process perspective on strategic decision making. Management Decision, 34, 46–53. doi:10.1108/00251749610106972

- Hogg, M.A., & Vaughan, G. (1995). Social psychology: An introduction. London, UK: Prentice Hall.

- Holtbrügge, D., & Berning, S.C. (2014). The National Government's role in Chinese outward foreign direct investment. In C.C. Julian, Z.U. Ahmed, & J. Xu (Eds.), Research handbook on the globalizaiton of Chinese firms (pp. 94–134). Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Huang, W., & Wilkes, A. (2011). Analysis of China's Overseas Investment Policies. Bogor, Indonesia: Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Retrieved from http://www.cifor.org/publications/pdf_files/WPapers/WP-79CIFOR.pdf

- Huliaras, A., & Petropoulos, S. (2014). Shipowners, ports and diplomats: The political economy of Greece’s relations with China. Asia Europe Journal, 12, 215–230. doi:10.1007/s10308-013-0367-1

- Kampanis, Z. (2017, June 2). One Belt One Road: the turning point for the recovery of Greek economy? Retrieved from http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/opinion/2017beltandroad/2017-06/02/content_29598723.htm

- Kynge, J., Campbell, C., Kazmin, A., & Bokhari, F. (2017, January 12). How China rules the waves. Retrieved from https://ig.ft.com/sites/china-ports/

- Leutert, W. (2016). Challenges ahead in China's reform of state-owned enterprises. Asia Policy, 21, 83–99. doi:10.1353/asp.2016.0013

- Li, S.X., Yao, X., Sue-Chan, C., & Xi, Y. (2011). Where do social ties come from: Institutional framework and governmental tie distribution among Chinese managers. Management and Organization Review, 7, 97–124. doi:10.1111/j.1740-8784.2010.00187.x

- Liang, H., Ren, B., & Sun, S.L. (2015). An anatomy of state control in the globalization of state-owned enterprises. Journal of International Business Studies, 46, 223–240. doi:10.1057/jibs.2014.35

- Luo, Y., & Tung, R.L. (2007). International expansion of emerging market enterprises: A springboard perspective. Journal of International Business Studies, 38, 481–498. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400275

- Ma, D. (2015, November 6). Personal interview with an Expert on Shipping Business of China/Interviewer: Y. Ma.

- Mihalakas, N. (2011, January 15). Chinese 'trojan horse'-investing in Greece, or invading Europe (Part I). Retrieved from http://foreignpolicyblogs.com/2011/01/15/chinese-%E2%80%98trojan-horse%E2%80%99-investing-in-greece-or-invading-europe-part-i/

- Ministry of Foreign Affairs of PRC. (2006, January 20). 中国和希腊关于建立全面战略伙伴关系的联合声明. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/gongbao/content/2006/content_219956.htm

- OECD Working Group. (2009). State owned enterprises in China: Reviewing the evidence. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/daf/ca/corporategovernanceofstate-ownedenterprises/42095493.pdf

- PCT Staff. (2015, September 10) Personal interview with a Senior Staff of Piraeus Container Terminals S. A./Interviewer: Y. Ma.

- Peverelli, P.J. (2000). Cognitive space: A social cognitive approach to Sino-Western Cooperation. Delft: Eburon.

- Peverelli, P.J., & Verduyn, K. (2012). Understanding the basic dynamics of organizing. Delft: Eburon.

- Psaraftis, H.N., & Pallis, A.A. (2012). Concession of the Piraeus container terminal: Turbulent times and the quest for competitiveness. Maritime Policy & Management, 39, 27–43. doi:10.1080/03088839.2011.642316

- Ren, B., Liang, H., & Zheng, Y. (2010). Chinese multinationals' outward foreign direct investment: an institutional perspective and the role of the state. Paper presented at the 4th China Goes Global Conference, Harvard University. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1603763

- Ren, B., Liang, H., & Zheng, Y. (2012). An institutional perspective and the role of the state for Chinese OFDI. In I. Alon, M. Fetscherin, & P. Gugler (Eds.), Chinese international investments (pp. 11–37). Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ren, F., & Liu, B. (2006, December 18). 国资委:国有经济应保持对七个行业的绝对控制力. Retrieved from http://www.gov.cn/jrzg/2006-12/18/content_472256.htm

- Ren, H. (2015). 中远比雷埃夫斯项目——中国企业 “走出去” 的新形象. [The project of COSCO Piraeus: A new look for Chinese enterprises' Going Global']. 中国远洋航务 (2), 15.

- Reuters Staff. (2008, June 12). UPDATE 2-Piraeus Port names COSCO provisional tender winner. Retrieved from https://in.reuters.com/article/greece-port-cosco/update-2-piraeus-port-names-cosco-provisional-tender-winner-idINL1245511020080612

- Robins, F. (2013). The uniqueness of Chinese outward foreign direct investment. Asian Business & Management, 12, 525–537. doi:10.1057/abm.2013.15

- Sauvant, K.P., & Chen, V.Z. (2014). China’s regulatory framework for outward foreign direct investment. China Economic Journal, 7, 141–163. doi:10.1080/17538963.2013.874072

- Scott, W.R. (2002). The changing world of Chinese enterprise: An institutional perspective. In A.S. Tsui & C.-M. Lau (Eds.), The management of enterprises in the people’s republic of China (pp. 59–78). Boston, MA: Springer US.

- Si, Y.-F. (2014). The development of outward FDI regulation and the internationalization of Chinese firms. Journal of Contemporary China, 23, 804–821. doi:10.1080/10670564.2014.882535

- Simon, H.A. (1977). The new science of management decision: Revised edition. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prenstice-Hall.

- Smircich, L., & Morgan, G. (1982). Leadership: The management of meaning. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 18, 257–273. doi:10.1177/002188638201800303

- Smoltczyk, A. (2015, April 9). China seeks dominance in Athnes Harbor. Retrieved from http://www.spiegel.de/international/business/china-seeks-gateway-to-europe-with-greek-port-a-1027458.html

- Stamouli, N. (2016, April 8). Greece signs deal to sell stake in port of Piraeus to China’s COSCO. Retrieved from http://www.wsj.com/articles/greece-signs-deal-to-sell-stake-in-port-of-piraeus-to-chinas-cosco-1460130394

- Stlylianidis, E. (2017, December 4) Personal interviews with Mr Evripidis Stylianidis on COSCO's investment in Piraeus Port/Interviewer: Y. Ma.

- Szamosszegi, A., & Kyle, C. (2011). An analysis of state-owned enterprises and state capitalism in China. Washington, DC: Capital Trade. Retrieved from http://www.uscc.gov/sites/default/files/Research/10_26_11_CapitalTradeSOEStudy.pdf

- Vamvakas, P. (2014). Global stability and the geopolitical vortex of the Eastern Mediterranean. Mediterranean Quarterly, 25, 124–140. doi:10.1215/10474552-2830902

- Van der Putten, F.-P., & Meijnders, M. (2015, March 25). China, Europe and the maritime silk road. Clingendeal Magazine, Retrieved from: http://www.clingendael.nl/publication/china-europe-and-maritime-silk-road

- Van Dongen, C.J. (1996). Quality of life and self-esteem in working and nonworking persons with mental illness. Community Mental Health Journal, 32, 535–548. doi:10.1007/BF02251064

- Voss, H., Buckley, P.J., & Cross, A.R. (2009). An assessment of the effects of institutional change on Chinese outward direct investment acitivity. In I. Alon, J. Chang, M. Fetscherin, C. Lattemann, & J. R. McIntyre (Eds.), China rules: Globalization and political transformation (pp. 135–165). Houndmills, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wang, C., Hong, J., Kafouros, M., & Wright, M. (2012). Exploring the role of government involvement in outward FDI from emerging economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 43, 655–676. doi:10.1057/jibs.2012.18

- Wang, J. (2014). The political logic of corporate governance in China’s state-owned enterprises. Cornell International Law Journal, 47, 632–669. Retrieved from https://scholarship.law.cornell.edu/cilj/vol47/iss3/5'.

- Weick, K.E. (1979). The social psychology of organizing. New York, NY: Random House.

- Weick, K.E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. London, UK: SAGE Publications.

- Xiao, Y. (2011, November 18). 魏家福:世界航运中心将向中国转移. Retrieved from: http://finance.sina.com.cn/g/20111118/124910841564.shtml

- Zou, X. (2016, March 30). Speech by Ambassador Zou Xiaoli at the seminar 'the New Silk Road of China: One Belt, One Road (OBOR) and Greece'. Retrieved from: http://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/wjb_663304/zwjg_665342/zwbd_665378/t1351971.shtml