Abstract

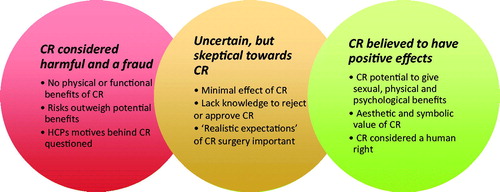

Background: Clitoral reconstruction (CR) is surgical reparation of the clitoris cut as part of the practice of female genital cutting (FGC) available in a handful of countries, including Sweden. The surgery aims at restoring the clitoris esthetically and functionally, thus has implications for sexual health. Gynaecological examinations can be an opportunity for dialogue regarding women’s sexual health. Gynecologist play a role in referring patients experiencing FGC-related problems, including sexual, to specialist services such as CR. Aim: The aim of this study was to explore how gynecologists position themselves in relation to CR. Method: Eight gynecologists were interviewed using semi-structured interviews. The interviews were tape-recorded, transcribed and analyzed using thematic analysis. Results: The gynecologists positioned themselves in three different ways in relation CR; outright negative, uncertain or positive toward the surgery. Those positioning themselves as negative thought CR was a harmful fraud and denied any possible benefits, at least sufficient for referral for CR. Those positioning themselves as uncertain did not deny possible benefits, but were skeptical toward CR improving cut women’s sexual health and function. Those positioning themselves positive considered the potential physical, psychological/emotional, esthetic, or symbolic aspects of CR as important for general well-being and sexual health. Conclusion: There was a great variety in how the gynecologists positioned themselves toward CR, and many were skeptical toward the functional benefits in relation to sexual health. This is likely to diverge cut women’s access to CR surgery.

Introduction

In Sweden, women who have had their clitoris cut as part of female genital cutting (FGC) can have their clitoris surgically repaired (TT, Citation2015; Werner, Citation2016). The surgery, often referred to as clitoral reconstruction (CR), aims at restoring the clitoris esthetically and functionally (Foldès et al., Citation2012). CR has implications for sexual health and function, but also for well-being in a broader sense, as women sometimes request surgery with the intention to symbolically restore their bodily integrity and sense of womanhood (Jordal et al., Citation2019; Villani, Citation2015).

FGC is a recognized term for various alterations of the female genitals for non-medical reasons (WHO, Citation2016). It is traditionally practiced in areas of Africa, the Middle East and Asia, and an estimated 200 million women and girls worldwide have undergone some form of FGC (UNICEF, Citation2016). Due to migration, FGC has become a global phenomenon; it is estimated that more than half a million women affected by FGC live in Europe (Van Baelen et al., Citation2016), with 38,000 residing in Sweden (The National Board of Health & Welfare, Citation2015). With a continued increase of FGC-affected women in Europe and Sweden (Eurostat, Citation2016), the demand on healthcare systems to deal with FGC-related problems is likely to intensify. Studies indicate that healthcare professionals (HCPs) generally lack knowledge regarding FGC-affected women’s needs and how to adequately care for patients with FGC-related problems (Dawson et al., Citation2015; Jordal & Wahlberg, Citation2018; Tilley, Citation2015; Turkmani et al., Citation2018; Vissandjée et al., Citation2014; Zaidi et al., Citation2007; Zurynski et al., Citation2015). In Sweden, the HCPs most likely to encounter women with FGC-related concerns are midwives, obstetricians and gynecologists (Länsstyrelsen Östergötland, Citation2014). The few existing studies in Sweden investigating HCPs perceptions’ of FGC-affected patients and their healthcare needs concern midwives and obstetricians in the context of infibulation and childbirth (Jordal & Wahlberg, Citation2018). Thus, there is a lack of research on gynecologists’ experiences of caring for FGC-affected women.

There is no clear evidence as to what the effect of FGC on women’s sexual health, pleasure and function is. According to WHO sexual health is “a state of physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality; not merely the absence of disease, dysfunction and infirmity” (WHO, Citation2002). Because sexual health is highly subjective and influenced by several factors such as body image, self-confidence, culture and language, it is difficult to measure (Berman et al., Citation2003; Parker, Citation2009). Challenges in studying the effects of FGC on women’s sexual health, pleasure and function specifically include difficulties in finding accurate measuring scales and selecting appropriate comparison groups (Abdulcadir et al., Citation2016; Johnson-Agbakwu & Warren, Citation2017). Thus, studies trying to investigate the effect of FGC on sexual health do not have coherent findings; some point toward a negative effect (Battle et al., Citation2017; Elnashar & Abdelhady, Citation2007) while others have not noted much difference in cut and uncut women’s sexual pleasure (Berg et al., Citation2010; Obermeyer, Citation2005).

CR was developed in the 1990s to offer FGC-affected women a possibility to restore the clitoris anatomically and functionally (Foldès et al., Citation2012). The surgery involves bringing underlying clitoral tissue to the surface and thereby relocating the clitoral stump to the position of the clitoral glans (Foldès & Louis-Sylvestre, Citation2006). CR is only available in a handful of European countries, including France, Switzerland, Belgium, Spain, and Sweden (Jordal & Griffin, Citation2018). Studies investigating the effects of the surgery are as yet few in number, but documented positive effects include: a sense of restored identity and self-image, improved sexual function, and reduced vulvar and clitoral pain (Abramowicz et al., Citation2016; Berg et al., Citation2017; Foldès et al., Citation2012; Merckelbagh et al., Citation2015; Vital et al., Citation2016). Post-operative complications such as postoperative bleeding and infections, as well as reduced capacity to orgasm after surgery, have been reported (Berg et al., Citation2017; Foldès et al., Citation2012).

In Sweden, CR was introduced in 2014 and is offered free of charge as part of public healthcare (Hallberg, Citation2015; Werner, Citation2016). The surgery is carried out by plastic surgeons who also perform reconstructive plastic surgeries and transgender surgeries (Sigurjonsson & Jordal, Citation2018). The surgeons work together with specialists in gynecology, sexology and psychiatry, and women asking for CR are required to undergo sexual counseling prior to surgery. This model has been recommended based on experience in other countries such as France and Belgium (Caillet et al., Citation2018; Merckelbagh et al., Citation2015). Since CR surgery is part of specialist care in Sweden, women opting for CR surgery need to be referred by their general practitioner or first line doctor.

Among HCPs, gynecologists are often perceived to be among those with the greatest competence regarding problems and diseases related to female genitalia. Gynaecological examinations can be an opportunity for dialogue regarding women’s sexual health (Neises, Citation2002). Women experiencing FGC-related problems who may desire to undergo CR are likely to choose a gynecologist as the first point of entry in seeking help (Jordal et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, gynecologists are likely to meet FGC-affected patients in maternal and delivery wards and during routine gynaecological checkups. This places gynecologists in a unique situation for investigating potential FGC-related problems, which the women themselves may feel too shy to bring up (Berggren et al., Citation2006). Gynecologists thus play a crucial role in referring women to specialist services, including CR surgery. How gynecologists position themselves in relation to CR surgery will most probably affect how they advise women around CR surgery as well as their likelihood to refer patients for such surgery. Thus, it is of interest to understand how gynecologists understand and position themselves in relation to CR as a potential way to help FGC-affected women in terms of sexual health and general well-being.

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore how gynecologists position themselves in relation to CR surgery.

Methods

The study has a qualitative design. Qualitative designs are ideal for obtaining an in-depth understanding of a scarcely studied phenomenon (Kvale & Brinkmann, Citation2009), thus suitable for exploring gynecologists’ perspectives on CR. The inclusion criterion for the participants was to be a trained gynecologist working at a hospital or healthcare clinic and having the experience of working with FGC-affected patients. Participants were recruited from two hospitals in urban Sweden. Fourteen eligible gynecologists were asked to participate, whereof ten accepted the invitation.

The interviews were carried out by the second author under supervision of the first author in the period between 2016 and 2018. They took place in a location chosen by the participant, often their work place, and dealt with the gynecologists’ thoughts around (a) FGC as a practice, (b) the relationship between FGC and sexuality, (c) the role of gynecologist in supporting FGC-affected patients, and (d) their knowledge and thoughts about CR. The interviews lasted between 40 and 80 min. While all the interviews were recorded, technical problems resulted in two of the recordings being unusable. Thus, eight interviews were transcribed and analyzed thematically (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). The included participants were aged between 35 and 67 years, and all but one were women. Some were, in addition to being trained gynecologists, also obstetricians, researchers and/or sexologists. Two of the participants were non-European immigrants.

The participants were given oral and written information stating the purpose of the study, and procedures regarding confidentiality. Participation was voluntary and could be discontinued at any point of during the data collection phase without the need to state a reason. The interviews were anonymized already at the time of the recording. The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Stockholm (2016/702-32).

Results

The gynecologists had different experiences in caring for FGC-affected patients; some positioned themselves as “experts” due to their extensive exposure to such patients, while others said they only saw such patients occasionally.

In general, the gynecologists’ said they knew little about CR surgery; some had read articles about this surgery while others knew little except that it existed. Yet, some considered themselves to have more than average knowledge on the topic. Not knowing much regarding the effect of FGC on women’s sexual health or how CR is carried out, on which indications, and what is to be expected from the surgery, the gynecologists based their thoughts and reflections on CR on their gynaecological and medical knowledge. This included whether the surgery could possibly help FGC-affected women, especially in relation to sexual health and function. Our data analysis suggested three different themes in terms of how the gynecologists positioned themselves in relation to CR surgery (), detailed below.

CR considered harmful and a fraud

Some of the gynecologists could not see any possible justification for referring patients to CR, which they considered both harmful and a fraud. They positioned themselves against CR and denied any possible benefits, at least sufficient for referral for CR. Rejecting CR, they often based this on a disavowal of the physical or functional benefits of CR, which they regarded as pivotal for referring women for surgery. Further, they worried that surgical risks such as post-surgical infections, bleeding, pain, and or possible long-term consequences including keloid formation and chronic pain might harm the women instead of helping them.

Potential psychological, esthetic, or symbolic expectations of the surgery, such as feeling “normal,” “whole” or esthetically restoring “destroyed” genitals were not perceived as justifying CR; instead women experiencing resentment over their FGC and cut genitals should be treated with psychosexual support and education about clitoral anatomy:

Every time we investigate we palpate and can feel that that clitoris is there, and we don’t make such a big business over it. Then we tell the woman that ‘you are not mutilated, but you have your gland there. The [clitoris] gland is very big, there are two legs…’ and then you explain. So, one can educate, it becomes like sexual education, and perhaps a bit of body awareness. (Kelly, 56 years old)

While this quote highlights the psychosexual aspects of FGC treatment, it also illustrates a focus on function and physiology; women’s understanding of themselves as “cut” and in need of CR might be “reversed” by proper education about the anatomy of the clitoris.

Within this positioning, CR was sometimes portrayed as a fraud produced by greedy HCPs, not gynecologists, intending to exploit vulnerable, FGC-affected women with low self-esteem for their own benefit, whether money or power. They doubted that women had any “real need” for CR. Instead they thought that it was the media portrayals of CR promising improved esthetics and sexual function that had created a feeling of lack, and thus a desire for CR:

When I heard about this operation [CR] for the first time (…) I thought ‘what kind of stupidity is this?’ I thought that no woman will come and ask for it. But if we talk about it they will become interested, of course. If somebody told me that there is an operation that can improve your looks and you are going to be more attractive, of course I will be interested. We are all humans and one thinks that one can have more [sexual] enjoyment, become more beautiful, etc. So, when I heard that I thought ‘oh, now there is another stupidity driven by healthcare professionals’. (Casey, 51 years)

Because the CR surgeons’ intentions were doubted, some expressed concern that the women in question would not be informed about the limited evidence related to the surgery. Even the surgeons’ competence in carrying out CR was questioned. These gynecologists saw cut women as in need of protection from surgeons and positioned themselves as gatekeepers in protecting women opting for surgery. They also positioned themselves as experts on FGC, the clitoris and CR. One gynecologist recounted how she would deal with women seeking care for FGC-related problems:

I would, based on my experience (…) first do an investigation and judge whether she has a clitoris or not, and then, depending on what kind of concerns she has and my judgement I would inform her honestly whether I think her concern that she tells me about has anything to do with the circumcision and its consequences and whether an operation [CR] can help her. Then I help her. (Casey, 51 years)

This quote illustrates the notion that there are “necessary” and “unnecessary” problems related to FGC, some that ought to, and can, be treated while others one just have to live with.

Even if rejecting any potential benefits from CR, some gynecologists had performed other types of reconstructive surgery after FGC such as defibulations. Yet, because these surgeries were considered “functional,” as opposed to CR, they were considered necessary and thus legitimate.

Uncertain, but skeptical toward CR

Several gynecologists positioned themselves as uncertain regarding whether they thought CR could be justified or not. They positioned themselves rather neutrally, thus did not outrightly reject the possibility that the surgery might have some possible positive effects on women’s sexual health or well-being. Yet, they admitted not knowing much about how physical, mental and emotional aspects of FGC-affected women’s sexual health and function. Some found it difficult to communicate with FGC-affected patients regarding FGC and sexual matters, mostly because these issues were considered taboo among FGC-affected women and because the gynecologists considered issues related to sexuality outside of their field of expertise. One gynecologist commented with disapproval on the average gynecologists’ reluctance to deal holistically with sexual health:

I think one [the average gynaecologist] tries to keep it [sex] as clinical as possible, so that it doesn’t become uncomfortable. And ‘in-out’, then one can relate it to reproduction. And then there will be babies, and it is clinical then. Then one also doesn’t need to handle all of this psychosocial stuff surrounding it either. (Alexis, 32 years)

Yet, this view was countered by others who positioned gynecology as a particularly holistic medical field and gynecologists to be more concerned about sexual identity and nonphysical aspects of sexuality than other medical professionals.

Some thought that the effect of FGC and clitorectomy on women’s sexual health and function was minimal, and based this on the fact that the clitoris is a large organ most of which remains under the surface. They therefore also thought that the effect of CR on women’s sexual function would be minimal. In particular, the gynecologists expressed skepticism toward believing CR could have any physical or functional effect:

I know very little [about CR], but then I have a lot of reflections about, I mean, what is it that one can help the woman with? One can help her cosmetically to look more normal, but can one help her improve her clitoral function? That I doubt… I do not know enough, but I have difficulties believing, based on my gynaecological-based knowledge, that a reconstruction could help. (Ellis, 48 years)

Within this positioning, the gynecologists considered the esthetic and symbolic benefits of CR, which some thought sufficient for justifying referral for CR, others not. Yet, they argued that the functional benefits were what should be in focus when considering surgery: “No, altogether I would say that one absolutely should see if this operation could benefit these women from a functional perspective, …. the main question should be function.” (Alexis, 32 years)

The gynecologists talked about needing to investigate women’s expectations of CR surgery; what they considered “realistic expectations” seemed to be important for the gynecologists’ willingness to refer a woman for surgery. Because the gynecologists often doubted any functional improvements regarding sexuality, women requesting CR surgery to improve their sexual health were deemed unrealistic. On the other hand, the gynecologists expressed willingness to refer patients for CR if they found the women’s motivation to be in line with their own view: “Yes, because one must find out what it is that you [the patient] expect from this [CR]. It is easy to say I want to be operated, but what do you expect? Is there a reasonable expectation? Like, is it about genitals that are destroyed by mutilation, to look more normal, if that is something that the patient believes could improve her situation, I wouldn’t hesitate to refer.” (Ellis, 48 years)

CR believed to have positive effects

Some gynecologists expressed a positive attitude toward CR surgery. They thought CR had the potential to help women experiencing FGC-related problems, including sexual, whether for physical or psychological reasons. Aware of the limited evidence concerning CR, some expressed trust in the surgeons performing CR regarding competence and willingness to inform women asking for surgery about the limited evidence, and that they had better technical skills to perform such an operation, as opposed to gynecologists.

One line of reasoning was that because the clitoris is important for women’s sexual pleasure, removal of sensitive clitoral tissue would physically reduce women’s capacity for sexual pleasure,. The gynecologists reasoned that CR made the clitoris more available for external stimulation and improved sensation in the area, thus had the potential to improve women’s sexual health: “when one is cut it [the clitoris] is there, hidden. And it is positioned deeper than… it is not on the surface. So then I could believe that it [CR] could influence the sex life positively. And then, an operation like that, as far as I understand, it is about expositing the clitoris glans more.” (Lennox, 65 years)

Some highlighted that FGC affected women mentally or emotionally, particularly if they had experienced FGC as a trauma or an insult to their bodily integrity, which again was thought to negatively affect women’s sexual health. Women experiencing FGC as a violation or deprivation of a body part were thought to benefit from CR on a psychological level. The gynecologists reasoned that CR could have a symbolic value, improving women’s self-confidence, which in turn could have positive effects on women’s sexual health and well-being. Furthermore, cut immigrant women’s exposure to the liberal norms around sexuality prevailing in Sweden was thought to make women want to reconstruct their genitals as part of a desire to “fit in” and increase their sense of belonging in Swedish society:

I think that these women who are mutilated, who have heard this terrible word, that they are ‘mutilated’, that it is an important aspect of the surgery to say that ‘you are now a “normal” woman, now you are a “normal, western, emancipated woman. Now we have operated away the past.” (…) To give back what has been taken away from them and to regain some kind of self-confidence. (Baylor, 67 years)

Some also pointed out the importance of the esthetic aspects related to FGC and CR, even if not everyone agreed that esthetics was a valid rationale for surgery. Having migrated from a context where FGC was constructed as beautiful and “right” to a context where it is not, was believed to affect women’s perceptions of their cut genitals, and result in discontent and resentment. CR, which by some was perceived as restoring the genitals esthetically, was thought to make cut women feel more at ease with their bodies, including in intimate and sexual encounters. In this context, the desire to undergo CR due for symbolic and esthetic reasons was considered legitimate.

Those positive toward CR surgery were aware that this view was not always shared by their gynecology colleagues, who might advocate for psychosexual counseling instead of surgery. Yet, as part of rejecting FGC and considering it a criminal act, some gynecologists argued that it was disrespectful to deny these women surgery. Instead, access to CR should be considered a human right, even for women who desire to undergo CR to “be like everybody else”: “It must be respected, then one cannot as a Swedish feminist say that you shouldn’t want that [CR], it is just because you want to be like everybody else.” Be proud of yourself”, what? What the heck, somebody has cut me to pieces when I was little, that needs to be respected.” (Alexis, 32 years)

Some gynecologists argued that cut woman’s own desire and wishes should be brought into consideration when deciding whether to refer patients for CR or not. Yet, one gynecologist talked about the difficulties doing so in practice, as there was resistance toward this among more experienced colleagues:

I even had women seeking healthcare for sexual dysfunction and asking about possibilities for reconstruction, and I then sought advice from more experienced colleagues. And they told me ‘there is nothing to be done, you should tell her that’. And I just ‘Is there not? She has heard that there is something in Stockholm’. ’No, not here!’ (Alexis, 32 years)

Discussion

The interviewed gynecologists positioned themselves in three different ways toward CR surgery; some were skeptical or outrightly negative toward any possible benefits of such surgery, others believed that CR could improve FGC-affected women’s lives and sexual health.

The role of the clitoris for women’s sexual health

The gynecologists did not agree on whether they thought a restored clitoris could improve sexual health and function; many doubted that this was the case. That the clitoris is a much larger organ than previously known, with a large part remaining under the surface, is today widely recognized (O’Connell et al., Citation1998). So is the acceptance that the clitoris is important for sexual pleasure (Mahar et al., Citation2020). Despite this, the normative sexual script is still focused on the coital imperative with penile-vaginal intercourse being the norm in heterosexual sex. This, in turn, affects how women’s sexual pleasure and climax through stimulation of the clitoris continues to be sidelined (Limoncin et al., Citation2020). The coital imperative goes back to Freud’s theories of the vaginal orgasm as the “mature” form, which has, despite being highly debated, impacted on prevailing sexual scripts (Gerhard, Citation2000; Koedt, Citation2010). The rejection of CR but not of defibulation in our findings, could imply a focus on the coital imperative and an alignment with heteronormative sexual scripts. It could also result from a focus on childbearing, something that was suggested by one gynecologist’s skepticism toward colleagues’ strictly “clinical” view of sexuality. The gynecologists who considered CR as potentially able to improve cut women’s sexual health and function did so based on functional, symbolic and esthetic aspects. Some thought that a restored clitoris could increase sexual function due to easier access for external stimulation. Further, they talked about sexual health in a broader way, where symbolic and esthetic aspects came into play and aspects outside the coital imperative were considered important. Those outright rejecting CR did not talk about potential symbolic or psychological benefits of the surgery, at least not as more than a “deception” initiated by the media and other HCPs. They also did not believe in any functional improvements through CR.

Limited sexological training among gynecologists

Previous studies have shown that while many women think of the gynecologist as the first person to contact in case of sexual problems, this is in stark contrast to the gynecologists’ often limited training and competence regarding sexual matters (Abdolrasulnia et al., Citation2010; Neises, Citation2002; Sobecki et al., Citation2012; Yulevitch et al., Citation2013). Even if it has been suggested that questions regarding sexual health should be included in routine gynaecological examinations (Briedite et al., Citation2013), many gynecologists, while considering it an important issue, rarely talk about sex in patient consultations (Kottmel et al., Citation2014; Sobecki et al., Citation2012; Wendt et al., Citation2007). Studies show that women often prefer their gynecologist to bring up the issue of sex (Briedite et al., Citation2013) and ask about FGC-related problems (Jordal & Wahlberg, Citation2018), as they themselves often feel embarrassed to initiate such conversations. These findings are in line with what the gynecologists in our study indicated and imply that women seldom get to discuss FGC-related problems, sexual or otherwise, in a healthcare context. In a recent study from Norway (Ziyada et al., Citation2020), the authors found that FGC-affected women with positive attitudes toward sexual and gender equality in their relationships were the ones anticipating that they would use FGC-related healthcare services. This was linked to perceiving themselves as having control over their lives and bodies. In Sweden, women seeking out CR similarly articulated this as a way to exercise control over their (sexual) lives (Jordal et al., Citation2019). If personal and sexual decision-making and control are among the driving factors behind FGC-related healthcare seeking, including CR, being stopped at the level of the gynecologist may have negative effects on the women’s well-being. And while psychosexual counseling may be an important part of healthcare, it is a concern that women are met with HCPs who have already made up their mind about CR. This may affect HCPs’ willingness to discuss CR as one possible care option for women experiencing FGC-related problems.

Genital determinism

As seen in our study, the gynecologists felt more confident dealing with physical problems than with psychological or sexual ones, although there were some exceptions. Considering the Swedish gynecologists’ limited training around sexual health (Statens Folkhälsoinstitut, Citation2016) it is not surprising that the gynecologists showed uncertainty surrounding psycho-sexual problems and solutions, and instead concentrated on the physical and anatomical aspects of their patients’ genitals. A broader understanding of the nonphysical dimension of women’s sexuality could perhaps facilitate a useful discussion around CR, including who might or might not benefit from such an operation. Johnsdotter (Citation2013) has argued that in much research the importance of physical genitals for sexual experience is overemphasized. She coins this “genital determinism” which fails to recognize the cultural context which is important for peoples’ meaning-making around sexuality. While some gynecologists were open toward the symbolic and cultural meanings of CR, the rejection of CR based on lack of physical benefits could be argued to be a kind of “genital determinism” in that it fails to consider those other meanings involved in CR.

The gynecologists as “gatekeepers”

The gynecologists who were skeptical toward CR highlighted the potential surgical risks. This could express a medical adherence to the Hippocratic Oath of “do no harm” and a desire to provide treatment based on science and evidence-based medicine (WHO, Citation2016). Instead, they argued for less invasive methods such as psychosexual treatment and counseling, something which has also been recommended as an alternative to CR in other contexts (Merckelbagh et al., Citation2015). Yet, this focus on surgical risks is interesting as CR is a minor operation compared to other surgeries, such as transgender surgery, that are widely accepted and carried out primarily based on social, emotional and symbolic bodily discomfort (Griffin & Jordal, Citation2018). Some gynecologists positioned themselves as “gatekeepers” of FGC-affected women, who were seen as vulnerable to deception by the media and the surgeons performing CR. Those that did not outrightly reject CR, but who had opinions on what qualified as legitimate reasons for undergoing CR, similarly saw it as their role to investigate women’s expectations for undergoing surgery. Based on the women’s reasons for the surgery as well as their medical expertise, they could then decide whether these expectations were deemed valid and justified referral for CR. The tendency for HCPs to evaluate whether patients’ reasons for CR surgery are “valid” has also been highlighted by Villani (Citation2009), who studied how medical teams providing CR surgery in France either accepted or rejected women for surgery based on the women’s articulated rationales. An example of gatekeeping in our study was illustrated by one gynecologist who had been discouraged by colleagues in referring a patient for CR. This means that, since a referral is needed for CR, women desiring to undergo CR may get different advice depending on the gynecologist they meet, or even be denied a referral. This may lead to inequality in care encounters and highlights the need for recommendations to HCPs to guarantee that all women with a desire for CR have the same chances of referral.

The “clinical gaze” of the medical expert

The gynecologists’ positioning of themselves as gatekeepers and “experts” in regard of whether women need CR or not can be related to Foucault’s description of the “clinical gaze”; namely that the medical doctor, in this case the gynecologist, is the one possessing knowledge relevant to decide what the patients’ problem is and how it should be solved. Foucault described the emergence of the medical profession prevailing in western societies today to the end of the 18th century when rationality and science came to influence the profession (Foucault, Citation1989). Prior to this, the doctor had to a large degree used conversations with the patient to understand her situation and set a diagnosis. Foucault argues that medical science appealed to a separation of body and psyche, where the doctor’s judgment of the patient’s health weighed more than patients’ own judgment, experiences and perceptions (Foucault, Citation1989, p. 58). Such a perspective, he argued, is merely one point of view among many, but that it has come to dominate western medical science after modernity (Foucault, Citation1989). The idea of the medical doctor as authoritative and as most capable of making decisions than the patient is evident in the interviews with the gynecologists. Based on their positions as medical professionals with specialized knowledge of female genitalia, the gynecologists positioned themselves as equipped to make decisions concerning CR. Yet, they simultaneously admitted relatively limited knowledge of the surgery. This paradoxical relationship may not be surprising since evidence of the effects of CR is still limited (WHO, Citation2016). Yet, it displays a form of Foucault’s “clinical gaze”. The reluctance of some gynecologists to consider CR can also be linked to what Ruth Holliday recognizes as a distinction between “cosmetic” and medically necessary surgery (Holliday, Citation2019). While “cosmetic” surgery is considered an issue of beauty and not often sanctioned by the public healthcare (but instead associated with plastic surgeons), surgery should solve a “medical” problem, which CR seemingly fail to do. Consequently, the gynecologists may be judging the patient’s reasons for CR as “unnecessary” and thus unjustified for public healthcare interventions. It is also an indication of a perception of FGC-affected women as incapable of judging their own needs and making own decisions.

The gynecologists’ skepticism toward the CR as a practice driven by the plastic surgeons performing it may also be a question of power. They expressed concern that the plastic surgeon is able to deceive vulnerable women, and wished to counter this through their gatekeeping. While this can be viewed as a wish to protect the patient from harm, it may also illustrate a hierarchy within the medical profession, including a fear that other specialisms such as plastic surgeons will use their power and undermine that of the gynecologists.

Methodological considerations

This study was undertaken as part of a thesis for the medical degree written by the second author. The second author, supervised by the first author who is experienced in research on the topic, recruited the participants and carried out the interviews. They continuously discussed issues relating to recruitment and interviewing, as well as the interpretation of the data.

The interviewer’s position as an “almost completed” medical doctor with explicit interest in sexuality, is likely to have influenced the participants’ answers, perhaps reflecting more on how CR is related to sexual health and function. Yet, this article focused less on how they perceived the link between FGC and sexuality and their professional role in relation to FGC-affected patients. CR is still relatively unknown in Sweden, something that is likely to have affected the results. And while the study is based only on eight interviews, it nevertheless demonstrated a wide range of positions toward CR, providing a broad description of the phenomenon and a sound basis for further research. Due to feasibility issues, the study was carried out in only two hospitals in urban Sweden. This limits the study to an urban setting, but it enhanced the chances of the gynecologists having been exposed to information about CR, compared with rural areas. Using illustrative and rich quotes, we have attempted to enable the reader judge our interpretation of the data as well as their transferability to other contexts.

Conclusion

The findings of this study demonstrate that the gynecologists positioned themselves in three different ways in relation to CR surgery: negative, uncertain, and positive. The study indicated that those positioning themselves as positive toward CR considered esthetic, psychological/emotional and physical aspects of the surgery important for women’s general well-being and sexual health, while those positioning themselves as negative dismissed any potential benefits of the surgery, at least of sufficient importance for referral. These findings may indicate that a positive positioning involves a more holistic view of sexual health and well-being, while a negative positioning involves a reductionist view of genitals and sexual function. Yet, at the same time, an outspoken argument against CR involved questioning the need to surgically change the genitals to improve psychosexual aspects. Viewing FGC and CR as a physical or medical but not sexual or psychosocial problem reflects the medical tradition of casting the doctor in the role of expert, with limited consideration of the patient’s view. It is also associated with limited expertise in sexology and sexual matters among gynecologists. FGC-related problems and possible solutions such as CR are still marginalized in many western contexts, although an increasing interest in the topic is evident. To equip gynecologists to provide adequate care for cut women, more knowledge and focus on different care options, both surgical and psychological, are needed. Given the limited conclusive evidence around CR, future research should investigate to what degree CR is a means to reduce FGC-related ill-health. The role of psychosexual education, alone or in combination with surgery, in improving cut women’s lives, should also be investigated. In any event, healthcare interventions to solve or reduce FGC-related problems should always be done in discussion with the women affected by FGC, considering their needs and desires.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the gynaecologists who took their time to participate in this interview study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Abdolrasulnia, M., Shewchuk, R. M., Roepke, N., Shanette Granstaff, U., Dean, J., Foster, J. A., Goldstein, A. T., & Casebeer, L. (2010). Management of female sexual problems: Perceived barriers, practice patterns, and confidence among primary care physicians and gynecologists. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(7), 2499–2508. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.01857.x

- Abdulcadir, J., Botsikas, D., Bolmont, M., Bilancioni, A., Djema, D. A., Bianchi Demicheli, F., Yaron, M., & Petignat, P. (2016). Sexual anatomy and function in women with and without genital mutilation: A cross-sectional study. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(2), 226–237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2015.12.023

- Abramowicz, S., Oden, S., Dietrich, G., Marpeau, L., & Resch, B. (2016). [Anatomic, functional and identity results after clitoris transposition]. Journal de gynecologie, obstetrique et biologie de la reproduction, 45 (8), 963–971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jgyn.2016.03.010

- Battle, J. D., Hennink, M. M., & Yount, K. M. (2017). Influence of female genital cutting on sexual experience in Southern Ethiopia. International Journal of Sexual Health, 29 (2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2016.1265036

- Berggren, V., Bergström, S., & Edberg, A.-K. (2006). Being different and vulnerable: Experiences of immigrant African women who have been circumcised and sought maternity care in Sweden. Journal of Transcultural Nursing : Official Journal of the Transcultural Nursing Society, 17(1), 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043659605281981

- Berg, R. C., Taraldsen, S., Said, M. A., Soerby, I. K., & Vangen, S. (2017). The effectiveness of surgical interventions for women with FGM/C: A systematic review. BJOG. https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.14839

- Berg, R. C., Taraldsen, S., Said, M. A., Sorbye, I. K., & Vangen, S. (2017). Reasons for and experiences with surgical interventions for female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): a systematic review. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 14(8), 977–990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.05.016

- Berg, R. C., Underland, V., & Fretheim, A. (2010). Psychological, social and sexual consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): A systematic review of quantitative studies. In Report from Kunnskapssenteret nr 13 − 2010. Nasjonalt kunnskapssenter for helsetjenesten.

- Berman, L. A., Berman, J., Miles, M., Pollets, D. A. N., & Powell, J. A. (2003). Genital self-image as a component of sexual health: Relationship between genital self-image, female sexual function, and quality of life measures. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 29(sup1), 11–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/713847124

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Briedite, I., Ancane, G., Ancans, A., & Erts, R. (2013). Insufficient assessment of sexual dysfunction: A problem in gynecological practice. Medicina (Medicina) 49(7), 49–320. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina49070049

- Caillet, M., O’Neill, S., Minsart, A.-F., & Richard, F. (2018). Addressing FGM with multidisciplinary care. The experience of the Belgian reference center CeMAViE. Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(2), 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-018-0145-6

- Dawson, A., Homer, C. S. E., Turkmani, S., Black, K., & Varol, N. (2015). A systematic review of doctors’ experiences and needs to support the care of women with female genital mutilation. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics: The Official Organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics, 131(1), 35–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2015.04.033

- Elnashar, A., & Abdelhady, R. (2007). The impact of female genital cutting on health of newly married women. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics, 97(3), 238–244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.03.008

- Eurostat (2016). Migration and migrant population statistics. Eurostat.

- Foldès, P., Cuzin, B., & Andro, A. (2012). Reconstructive surgery after female genital mutilation: A prospective cohort study. Lancet (London, England), 380(9837), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60400-0

- Foldès, P., & Louis-Sylvestre, C. (2006). [Results of surgical clitoral repair after ritual excision: 453 cases]. Gynecologie, obstetrique & fertilite, 34(12), 1137–1141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gyobfe.2006.09.026

- Foucault, M. (1989). The birth of the clinic: An archaeology of medical perception. Routledge.

- Gerhard, J. (2000). Revisiting ‘The myth of the vaginal orgasm’: The female orgasm in American sexual thought and second wave feminism. Feminist Studies : FS, 26 (2), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178545

- Griffin, G., & Jordal, M. (Eds.). (2018). Body, migration and re/constructive surgeries. Making the gendered body in a globalized world, Routledge Research in Gender and Society. Routledge.

- Hallberg, J. (2015). Stort intresse för att återskapa klitoris. http://sverigesradio.se/sida/artikel.aspx?programid=105&artikel=6203018.

- Holliday, R. (2019). Vagina dialogues: Theorizing the ‘designer vagina’. In G. Griffin & M. Jordal (Eds.), Body, migration, re/constructive surgeries. Making the gendered body in a globalized world (pp. 192–208). Routledge.

- Johnsdotter, S. (2013). Discourses on sexual pleasure after genital modifications. The fallacy of genital determinism (a response to J. Steven Svoboda). Global Discourse, 3(2), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1080/23269995.2013.805530

- Johnson-Agbakwu, C., & Warren, N. (2017). Interventions to address sexual function in women affected by female genital cutting: A scoping review. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0099-0

- Jordal, M., & Griffin, G. (2018). Clitoral reconstruction: Understanding changing health care needs in a globalized Europe. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 25(2), 154–167. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350506817742679

- Jordal, M., Sigurjonsson, H., & Griffin, G. (2019). ‘I want what every other woman has’: Reasons for wanting clitoral reconstructive surgery after female genital cutting – a qualitative study from Sweden. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 21(6), 701–716. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1510980

- Jordal, M., & Wahlberg, A. (2018). Challenges in providing quality care for women with female genital cutting in Sweden - A literature review. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives, 17, 91–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2018.07.002

- Koedt, A. (2010). The myth of the vaginal orgasm. Nouvelles Questions Féministes, 29(3), 14–14. https://doi.org/10.3917/nqf.293.0014

- Kottmel, A., K. V., Ruether‐Wolf, & J. Bitzer, (2014). Do gynecologists talk about sexual dysfunction with their patients? The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 11(8), 2048–2054. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12603

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews. Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. Vol. 2. Sage.

- Länsstyrelsen Östergötland. (2014). Våga se. En vägledning för stöd, vård och skydd av flickor och kvinnor som är eller risikerar att bli könsstympade. Enheten för social hållbarhet.

- Limoncin, E., Nimbi, F. M., & Jannini, E. A. (2020). Pleasure, orgasm, and sexual mutilations in different cultural settings. In D. L. Rowland & E. A. Jannini (Eds.), Cultural differences and the practice of sexual medicine (pp. 237–252). Springer.

- Mahar, E. A., Mintz, L. B., & Akers, B. M. (2020). Orgasm equality: Scientific findings and societal implications. Current Sexual Health Reports, 12, 1.

- Merckelbagh, H. M., Nicolas, M. N., Piketty, M. P., & Benifla, J. L. (2015). [Assessment of a multidisciplinary care for 169 excised women with an initial reconstructive surgery project]. Gynecologie, obstetrique & fertilite, 43 (10), 633–639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gyobfe.2015.09.002

- Neises, M. (2002). Sexuality and sexual dysfunction in gynecological psychooncology. Onkologie, 25 (6), 571–574. https://doi.org/10.1159/000068630

- Obermeyer, C. M. (2005). The consequences of female circumcision for health and sexuality: An update on the evidence. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 7(5), 443–461.

- O'Connell, H. E., Hutson, J. M., Anderson, C. R., & Plenter, R. J. (1998). Anatomical relationship between urethra and clitoris. Journal of Urology, 159(6), 1892–1897. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-5347(01)63188-4

- Parker, R. (2009). Sexuality, culture and society: Shifting paradigms in sexuality research. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 11(3), 251–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050701606941

- Sigurjonsson, H., & Jordal, M. (2018). Addressing female genital utilation/Cutting (FGM/C) in the era of clitoral reconstruction: Plastic surgery. Current Sexual Health Reports, 10(2), 50–56. doi: doi.org/10.1007/s11930-018-0147-4. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-018-0147-4

- Sobecki, J. N., Curlin, F. A., Rasinski, K. A., & Lindau, S. T. (2012). What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex: Results of a National Survey of U.S. Obstetrician/Gynecologists. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9 (5), 1285–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02702.x

- Statens folkhälsoinstitut. (2016). Sex, hälsa och välbefinnande. Statens folkhälsoinstitut.

- The National Board of Health and Welfare (2015). Kvinnor och flickor som kan ha varit utsatta för könsstympning: En uppskattning av antalet. Socialstyrelsen.

- Tilley, D. S. (2015). Nursing care of women who have undergone genital cutting. Nursing for Women’s Health, 19(5), 445–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/1751-486X.12237

- TT. (2015, June 01). Kö för att få klitoris återskapad. Dagens Nyheter.

- Turkmani, S., Homer, C., Varol, N., & Dawson, A. (2018). A survey of Australian midwives’ knowledge, experience, and training needs in relation to female genital mutilation. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 3(1), 25–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2017.06.009

- UNICEF (2016). At least 200 million girls and women alive today living in 30 countries have undergone FGM/C. UNICEF.

- Van Baelen, L., Ortensi, L., & Leye, E. (2016). Estimates of first-generation women and girls with female genital mutilation in the European Union, Norway and Switzerland. The European Journal of Contraception & Reproductive Health Care: The Official Journal of the European Society of Contraception, 21(6), 474–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/13625187.2016.1234597

- Villani, M. (2009). From the ‘maturity’ of a woman to surgery: Conditions for clitoris repair. Sexologies, 18(4), 259–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2009.09.013

- Villani, M. (2015). Le sexe des femmes migrantes. Excisées au Sud, reparée au Nord. Travail, genre et sociétés, n° 34(2), 93–108. https://doi.org/10.3917/tgs.034.0093

- Vissandjée, B., Denetto, S., Migliardi, P., & Proctor, J. (2014). Female genital cutting (FGC) and the ethics of care: Community engagement and cultural sensitivity at the interface of migration experiences. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 14(1), 13–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-698X-14-13

- Vital, M., de Visme, S., Hanf, M., Philippe, H. J., Winer, N., & Wylomanski, S. (2016). Using the female sexual function index (FSFI) to evaluate sexual function in women with genital mutilation undergoing surgical reconstruction: A pilot prospective study. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Biology, 202(2016), 71–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2016.04.029

- Wendt, E., Hildingh, C., Lidell, E., Westerståhl, A., Baigi, A., & Marklund, B. (2007). Young women’s sexual health and their views on dialogue with health professionals. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 86(5), 590–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/00016340701214035

- Werner, M. (2016, 27 Sep). Könsstympade kvinnor kan få klitoris återskapad. Sydsvenskan. http://www.sydsvenskan.se/2016-09-27/konsstympade-kvinnor-kan-fa-klitoris-aterskapad.

- WHO (2002). Defining sexual health: Report of a technical consultation on sexual health. World Health Organization.

- WHO (2016). WHO guidelines on the management of health complicatons from female genital mutilation. WHO.

- Yulevitch, A., Czamanski-Cohen, J., Segal, D., Ben-Zion, I., & Kushnir, T. (2013). The vagina dialogues: Genital self-image and communication with physicians about sexual dysfunction and dissatisfaction among Jewish patients in a women’s health clinic in Southern Israel. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 10(12), 3059–3068. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12322

- Zaidi, N., Khalil, A., Roberts, C., & Browne, M. (2007). Knowledge of female genital mutilation among healthcare professionals. Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology: The Journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 27(2), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443610601124257

- Ziyada, M. M., Lien, I.-L., & Johansen, E. B. (2020). Sexual norms and the intention to use healthcare services related to female genital cutting: A qualitative study among Somali and Sudanese women in Norway. Plos One, 15(5), e0233440. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0233440

- Zurynski, Y., Sureshkumar, P., Phu, A., & Elliott, E. (2015). Female genital mutilation and cutting: A systematic literature review of health professionals’ knowledge, attitudes and clinical practice. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0070-y