Abstract

Objectives

Sexual health includes the state of physical, emotional, mental, and social well-being related to sexuality. Masturbation is an important sexual activity with many potential benefits which has gained considerable interest in sexuality research in the past twenty years; however, this research is the first of its kind within the Aotearoa/New Zealand context. In this in-depth investigation, we examined frequencies of, reasons for, and activities during masturbation as well as the relationship between masturbation and other factors.

Methods

Participants were 698 New Zealand women at least 18 years of age participating in a 42-item anonymous online survey collecting comprehensive information about sexual practices and related factors.

Results

The results indicated that female masturbation has high prevalence in the New Zealand population.

Conclusion

The pattern of results enabled us to identify the positive effects of masturbation, masturbation practices commonly used by New Zealand women and the differences between New Zealand women who masturbate frequently and less frequently.

Introduction

Masturbation has been the subject of cultural, religious, political and scientific debates for centuries (Bullough, Citation2003; Coleman, Citation2003; Laqueur, Citation2003). Historically, masturbation, especially female masturbation, has been considered as a harmful and abnormal practice in most cultures, and is still a taboo in many societies (Coleman, Citation2003; Laqueur, Citation2003).

Many traditional cultures and religions hold that the appropriate aim of sexual behavior is reproduction that should happen within the context of marriage, rendering masturbation sinful, or inappropriate (Ruan, Citation1991; Verma et al., Citation1998), often associating guilt and shame with it (Aneja et al., Citation2015). The stigmatization sometimes leads to classifying masturbation not only as socially deviant or abnormal (Bullough, Citation2003; Bullough & Bullough, Citation2019; Maines, Citation1999), but also as damaging for the individual or for the social order (Ruan, Citation1991).

Although attitudes toward sex have become more open over time (Wells & Twenge, Citation2005) and several studies have confirmed that masturbation is a common and frequently practiced sexual activity in humans of both sexes and all ages (Bowman, Citation2014; Richters et al., Citation2014), there is still considerable stigma around it and abstinence is frequently recommended by lay people to avoid harmful physiological and psychological consequences (Zimmer & Imhoff, Citation2020).

More than 70 years after publishing the famous Kinsey Reports (Kinsey et al., Citation1948, Citation1953), the first major scientific studies that contributed to normalizing many aspects of sexual behavior, masturbation remains a relatively unexplored area of sexual health studies, and as a result, there is still insufficient scientific knowledge, particularly in societies outside of Europe and North America available on why and how people engage in the behavior, what their thoughts, feelings and experiences are, and how it impacts their overall sexual health (Coleman, Citation2003; Driemeyer et al., Citation2017).

Sexual health and masturbation

The first WHO definition of sexual health was relatively broad at the time, including not only somatic, but “emotional, intellectual and social aspects of sexual being, in ways that are positively enriching and that enhance personality, communication and love,” the “right to sexual information and the right to pleasure,” the “capacity to enjoy and control sexual and reproductive behavior,” and “freedom from fear, shame, guilt, false beliefs, and other psychological factors inhibiting sexual response” (World Health Organization, Citation1975, p. 6). Later definitions gradually included awareness of values, the appreciation of one’s own body, diversity, and as the latest development, the importance of human rights, responsibility, and mental health (Edwards & Coleman, Citation2004). This new understanding of sexuality had a huge effect on the promotion of sexual health and sexual education.

Recent understanding of sexual health puts masturbation into a new light. Multiple studies examined its potential benefits (Bancroft, Citation2005; Coleman, Citation2003; Zamboni & Crawford, Citation2003) and recognized that labeling it as negative or harmful can lead to adverse health consequences. Masturbation today is understood as an important part and a marker of healthy sexual development (Bancroft et al., Citation2003; Langfeldt, Citation1981; Saliares et al., Citation2017) as it provides a valuable opportunity, especially for adolescents and young adults, to learn about their bodies and sexual responsiveness (Atwood & Gagnon, Citation1987; Saliares et al., Citation2017) and to enhance and monitor sexual arousal and sexual pleasure (Brindis, Citation2006; Davidson & Darling, Citation1993; Pinkerton et al., Citation2003; Rowland & Cooper, Citation2017).

Masturbation can also be beneficial for improving the ability to experience orgasm (Rowland et al., Citation2019; Rowland, Hevesi, et al., Citation2020) and was found to be effective in the treatment of various disorders related to sexual health, such as female sexual dysfunction (Both & Laan, Citation2008; Coleman, Citation2003; Heiman et al., Citation2010; Laan & Rellini, Citation2011; Phillips, Citation2000). Several authors recommend using masturbation in sexual therapy instead of medical therapeutic approaches (McCarthy, Citation2004; Zamboni & Crawford, Citation2003), sometimes as the primary choice for treating sexual dysfunction in women, as partnered sex is “inherently more complex and less predictable” (McCarthy, Citation2004, p. 22)

In addition, masturbation now is considered to have a positive impact on relaxation and stress-reduction (Burri & Carvalheira, Citation2019; Fahs & Frank, Citation2014; Leonard, Citation2010), sleep quality (Lastella et al., Citation2019), pain relief (Ellison, Citation2000; Komisaruk & Whipple, Citation1995; Masters & Johnson, Citation1966), or strengthening the pelvic floor muscles (Levin, Citation2007).

Masturbation and culture

Social norms strongly influence masturbatory behaviors and attitudes (Pinkerton et al., Citation2003). Kinsey et al.’s (Citation1953) study reported more than 60% of American women ever trying or regularly engaging in masturbation. This number in their self-selected sample was shockingly high at the time, but since then, as a result of more liberal attitudes toward female sexual behavior, in most Western societies, where gender equality is more valued, women’s reported masturbation rates have been steadily increasing (Kontula & Haavio-Mannila, Citation2003). However, it is unclear if women are actually more likely to masturbate or are more willing to report that they do so.

Today, women in more liberal cultures report much higher masturbation rates than women in more traditional societies. For example, 85.5% of female Swedish senior high-school students (Driemeyer et al., Citation2017), 85% of young American women (Herbenick et al., Citation2010), 78.9% of female Australian high school students (Fisher et al., Citation2020), 74% of French women (Kraus, Citation2017), and 71% of British (Gerressu et al., Citation2008), but only 32% of Russian (Kontula & Haavio-Mannila, Citation2003), 12.5% Bangladeshi (Chowdhury et al., Citation2019) and 10–11% of Chinese women (Chi et al., Citation2015) reported ever trying masturbation. Croatia, with approximately 60% (Baćak A & Štulhofer, Citation2011) and Iran with 62% (Shekarey et al., Citation2011) are in the middle.

Within countries, there are great differences among women depending on their SES and where they live. In China, different lifetime prevalence rates were found for rural (7%) and urban (18%) populations (Das et al., Citation2009). In Kraus’s (Citation2017) study French women with higher education level, higher SES, and in positions with more control (such as self-employed women and managers) were reported to masturbate more often than women from lower socioeconomic status, rural, or churchgoing communities. Religion itself is strongly associated with lower masturbation frequencies (Baćak A & Štulhofer, Citation2011; Driemeyer et al., Citation2017; Gerressu et al., Citation2008).

Cultural beliefs are often maintained even if the individual becomes part of another culture that is more accepting and liberal regarding masturbation (Meston et al., Citation1998; Yu, Citation2010). Canadian immigrant Chinese students are more likely to hold negative attitudes toward masturbation than Canadian-born students (Meston et al., Citation1998). Similarly, Reyes (Citation2016) found that mothers of Mexican origin in the US believed that masturbation was unhealthy, and females were not sexual beings until a man-initiated sexuality.

Age-related differences

Age and generational differences are also relevant (Rowland, Hevesi, et al., Citation2020). In a 14–17 years old US sample, lifetime prevalence of masturbation was higher in 17-year-old than in 14-year-old males and females, but the rate of recent masturbation (last 90 days) was higher only in older males, while it remained relatively similar in different female age groups (Robbins, Citation2011).

In a Chinese sample the percentage of women who never tried masturbation was higher for older age (96% of age 40 or over, 89% of women 30–39, and 82% of women 20–29) (Jing et al., Citation2018). These generational differences might also reflect the changes in cultural norms. Some authors note that women’s masturbation rate peaks later in life than that of men (Barr et al., Citation2002). Even though masturbation activity seems to decline with age (Palacios‐Ceña et al., Citation2012), more and more studies demonstrate that it is becoming commonly practiced and viewed as acceptable or normal by the elderly (Brecher, Citation1984; Bretschneider & McCoy, Citation1988; Johnson, Citation1998). In a study focusing on a US elderly population (mean age ± SD of 81 ± 6 years), Smith et al. (Citation2007) found that 18% of the participating women were still sexually active and masturbation turned out to be their most commonly reported sexual activity. A Spanish study of younger elderly women (mean age ± SD of 74.5 ± 6.3 years) also reported higher rates, with 37.4% of the participating women reported being sexually active (Palacios‐Ceña et al., Citation2012).

Why do women masturbate?

Much of the research on masturbation has focused on prevalence and frequency, not on reasons (Goldey et al., Citation2016; Hogarth & Ingham, Citation2009). According to the traditional belief, the goal of masturbation, and any sexual activity by that matter, was orgasm (Lavie-Ajayi & Joffe, Citation2009). Orgasm as a sole purpose of sexual activity nicely fits into Masters and Johnson’s stages of arousal framework (Masters & Johnson, Citation1966), Freud’s sex drive (Freud, Citation2012), and other motivation theories.

Orgasm seems to be an important reason for masturbation. Kinsey et al. (Citation1953) pioneering study found that 95% of female masturbation ends in orgasm, and it offers the most specific and quickest way to achieve orgasmic response, which has been confirmed by several studies since (Rowland et al., Citation2018; Towne, Citation2019). Some women who find it difficult to orgasm in heterosexual relationships can experience orgasm when they engage in masturbation (Fisher, Citation1973; Masters & Johnson, Citation1966). One possible explanation is that traditional sexual scripts prioritize vaginal-penile intercourse and male orgasm, which does not result in female orgasm as often as self-oriented sexual activity (Kraus, Citation2017; Willis et al., Citation2018).

Several studies have found that women masturbate for various reasons other than experiencing orgasm, such as physical pleasure, relief of sexual tension (although these two are often associated with orgasm), regulating negative physical and emotional feelings, feelings of self-affirmation and agency, stress relief or relaxation, and learning about their body (Bowman, Citation2014; Carvalheira & Leal, Citation2013; Fahs & Frank, Citation2014; Goldey et al., Citation2016; Laumann et al., Citation1994; Rowland et al., Citation2019). According to some studies, masturbation can feel sexually empowering to women (Bowman, Citation2014), as masturbation is self-controlled and self-directed, it can contribute feeling of autonomy and control over one’s body (Coleman & Bockting, Citation2013).

A brief history of the sexual culture in Aotearoa/New Zealand

New Zealand is a bicultural society: its social norms and traditional cultural beliefs are based on the Māori culture of the indigenous people of Aotearoa and the British/Victorian culture brought to New Zealand by the Europeans. Traditional Māori society accepted sexuality: sex and sexuality were openly discussed, and sexual diversity was recognized. This approach to sexuality changed after the European migrants introduced and imposed more conservative views on sexuality to New Zealand (Aspin & Hutchings, Citation2007). Just like in Europe and the US, New Zealand Pakeha (non-Māori) culture was characterized by conservative, Christian-based morality, aimed at suppressing sexual desire, especially in young girls (Jackson & Weatherall, Citation2010). New Zealand physicians promoted anti-masturbation attitudes and beliefs, repressive anti-masturbation strategies, and exposed masturbating boys to psychological and physical punishment until the early 20th century. As a result, “masturbation anxiety” remained present in New Zealand until the 1940s (Watson, Citation2016).

Sex education in New Zealand in the postwar period was still focusing on family, marriage, reproduction, and parenting (Gooder, Citation2016), completely ignoring pleasure as an important part of human sexuality. In the 1960s and 1970s, sexual education was not part of the national curriculum and occurred only in some schools either at parent-child evenings or under the guise of health education (Brickell, Citation2007).

As traditional gender roles and sexual morality were challenged in the 1960s, public opinion regarding the topic started to shift. Two government reports, the Ross Report in 1973 and the Johnson Report in 1977, were published supporting classroom discussion of gender roles, abortion, masturbation, and homosexuality, among other topics (Brickell, Citation2007). The reports met considerable opposition, and for almost two decades, sex education remained in the focus of different value groups clashing over broader societal issues, such as moral education and the rights of schools and parents (Weir, Citation2001).

It is worth mentioning that Gooder (Citation2016) analyzed sex education pamphlets published in New Zealand in the 1970s and found that none of them recognized masturbation as a legitimate sexual activity. A book, titled Down Under the Plum Trees (Tuohy & Murphy, Citation1976), discussed topics such as puberty, masturbation, pregnancy and birth, sexually transmitted diseases, and sexuality, illustrated with photographs, but in spite of its high popularity, a year later it was declared indecent for young people, and book shops were fined for exhibiting it (Brickell, Citation2007).

Finally, during the 1990s, sexual education was officially incorporated into the New Zealand school curriculum. Although these programs mainly discussed health concerns, they represented a step away from moral considerations. In 1999 the New Zealand Health and Physical Education curriculum included mandatory sexual education for all 13–14 year old students (New Zealand Family Planning, Citation2017). The main focus was still describing the male and female genitals, discussing health-related issues such as menstruation cycle, and advice on avoiding unwanted pregnancies and sexually transmitted illnesses (Ministry of Education, Citation1999).

Today, New Zealand’s Sexual and Reproductive Health Strategy (Ministry of Health, Citation2003) states that positive sexuality and sexual health are Government priorities; however, with its emphasis on reducing Sexually Transmitted Infections and unwanted pregnancies, the sexual education curriculum remains narrow, and it still tends to overemphasize sexual danger for women. In summary, there has been a steady improvement in the societal approaches toward sexuality in New Zealand and today, the government promotes good sexual and reproductive health and embraces sexual education (Ministry of Education, Citation1999; Ministry of Health, Citation2003, Citation2010; New Zealand Family Planning, Citation2017). However, the scope of the discussion is still limited and leaves out or only briefly mentions essential topics, such as masturbation and pleasure.

Aims for this study

The current study is aimed at exploring the practice of masturbation in a convenience sample of New Zealand women. The study is focusing on the following areas regarding masturbation in New Zealand women: (1) masturbation rates and habits in Aotearoa/New Zealand, (2) reasons for masturbation (3) sexual practices during masturbation, (4) pleasure, orgasmic response and orgasmic difficulty during masturbation (5) and the differences between women who masturbate more and less frequently.

Method

The current study is part of a cross-cultural research project taking place in various countries: the United States, Hungary and New Zealand. This paper only examines the results obtained in New Zealand.

Participants

Participants for this study were 698 New Zealander women at least 18 years of age who completed the questionnaire (). Those who only completed the demographic section were excluded. The average age of participants was 34.8 years (SD = 12.07, range: 18–78 years). Participation in the online survey occurred through self-selection, with the only promotion being social media advertisement identifying the need for women ages 18+ for a survey on female sexual health. No paid incentives or rewards were offered for participation.

Table 1. Demographic data by masturbation rates.

Measurement

A 42-item questionnaire, developed by Rowland et al. (Citation2018) based on three focus groups of women from the USA and Hungary, was used for the present study. Focus groups reviewed items, commented on their relevance, and added response categories. The questionnaire consists of three main sections. The first part of the survey asked about demographics, lifestyle behaviors, medications, and medical and sexual history, including questions regarding sexual orientation, gender identity, partnership status, and overall relationship characteristics and satisfaction. Medical history was examined via five binary (Yes/No) questions referring to (1) state of menopause, (2) use of sex-hormone supplements, (3) use of prescription medication (including birth control pills), (4) identification of any ongoing medical issues the respondent gets treatment for. One question referred to the current state of depression or anxiety (“Are you currently suffering from ongoing/persistent (>6 months) anxiety or depression?). The second part of the survey collected information about sexual response, including items related to the frequency of masturbation and partnered sex, sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, genital pain during sex, orgasmic response, orgasmic latency, orgasmic distress, and perceived partner distress in the past 12 months and/or in their current or most recent (primary) sexual relationship. This section used relevant items from the Female Sexual Function Index (Rosen et al., Citation2000). The third part focused on orgasmic response during partnered sex and masturbation, including methods and types of stimulation, estimated latency, derived pleasure, difficulties in orgasmic response, and perceived reasons for these difficulties during partnered or masturbatory activities.

Relevant to this analysis, the frequency of masturbation was measured using a 9-point Likert scale (1 = never; 9 = one or more times daily). Two questions explored the reasons for masturbation, using the past year as a timeframe, with the possibility of selecting one of 7 answer choices or “other.” In the first question, participants selected as many responses as they preferred, and in the second, they chose a single main reason. Participants were also asked about specific activities they typically engaged in during masturbation by selecting as many activities as they wanted from a list of 10 reasons (derived from the focus group) or by specifying activities not included in the list (Rowland et al., Citation2018).

Procedure

Ethical approval was obtained in New Zealand (approval no. 18/96) by AUTEC. Before completing the survey, all participants were informed about the purpose of the research and informed consent was obtained in the following way: once participants accessed the survey link, they were asked to confirm their consent by checking a consent statement box. Only those participants who confirmed their willingness to participate and who met the eligibility criteria were presented with the survey. Participation in the study was voluntary, and participants could withdraw from the study at any time by closing the online survey without submitting. Data from these withdrawn participants were deleted.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics and correlational analysis were conducted using IBM SPSS statistics software version 24.0. Missing data for demographic variables ranged from 0.3% to 1.7%, and 0.3–10.6% for a few items on frequency, orgasmic response, satisfaction and difficulties with masturbation. Some items on the length of time to reach orgasm and emotions around masturbation had slightly higher missing data (between 11.3% and 13.1%) but still within acceptable levels. Missing values were either addressed by collapsing categories or excluding these variables from the model. The outcome variable “frequency of masturbation” was sub-divided into “frequent,” “less frequently” and “almost never/never” groups based on participant numbers.

Results

Masturbation frequency

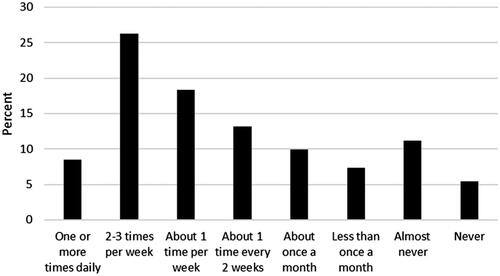

The results show that 76.1% of the participating New Zealand women reported masturbating at least once a month and only 5.4% reported never masturbating. The overall distribution for masturbation frequency was never: 5.4%, almost never: 11.2%, less than once a month: 7.3%, about once a month: 9.9%, about once every two weeks: 13.2%, about once a week: 18.3%, 2–3 times a week: 26.2%, one or more times daily 8.5% as displayed in .

Demographic and medical variables are compared in between 370 women who masturbate frequently (more than once a week), 212 who masturbate less frequently (between once a week to less than once a month), and 116 women who almost never masturbates (almost never or never). Within the sample, 52.9% masturbate frequently, 30.3% masturbate less frequently (between once a week to less than once a month), while 16.6% never or almost never masturbate.

There were significant age differences between the frequent and less frequent groups (p = .002). Women reporting more frequent masturbation were slightly younger (M = 33.35, SD = 11.33) than those who masturbate less frequently (M = 36.96, SD = 12.07), and those who reported almost never or never (M = 35.56, SD = 13.75), p = .002. Those who had current medical problems were also less likely to masturbate frequently (p = .010).

Reasons for masturbation

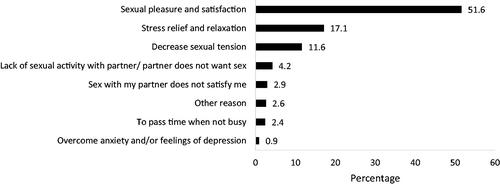

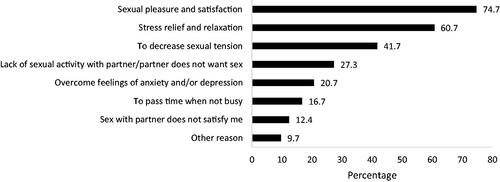

displays the single most important reason why the sample’s participants masturbate, while presents all the reasons why they masturbate. The most highly endorsed response was “sexual pleasure and satisfaction” identified by 74.7% of the sample as a contributing reason and by 51.6% as the most important reason. This was followed by “stress relief and relaxation” (most important: 17.1%, contributing: 60.7%) and “decreases sexual tension” (most important: 11.6%, contributing: 41.7%). Other contributing reasons on why women masturbate in decreasing order, include “lack of sexual activity with partner/partner does not want sex (27.3%),” “overcome feeling of anxiety and/or depression” (20.7%), “pass time when not busy” (16.7%) and “sex with my partner does not satisfy me (12.4%),” A minority (∼10%) reported other reasons such as “helping to sleep, and coping with long distance relationships or when partner is away.”

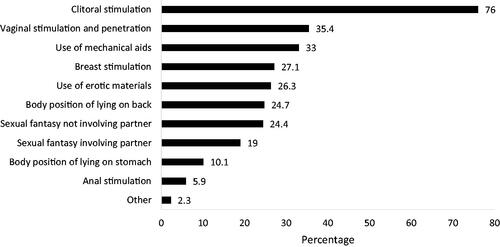

Sexual practices during masturbation

displays the percentage of various sexual activities used during masturbation, of these, clitoral stimulation was the most commonly selected activity (76%), followed by vaginal stimulation and penetration (35.4%), use of mechanical aids (33%), breast stimulation (27.1%), use of erotic materials (26.3%), body position of lying on back (24.7%), sexual fantasies not including one’s partner (24.4%), sexual fantasies that include/incorporate one’s partner (19%), body position lying on stomach (10.1%), anal stimulation (5.9%), only 2.3% of the participants chose other sexual practices not included in the above list, such as self-bondage or erotic writing.

shows the use of sexual practices during masturbation by the frequency of masturbation indicating that those who engage in masturbation frequently are more likely to incorporate clitoral, vaginal, breast, and anal stimulation into their masturbatory behaviors, compared to those who masturbate less frequently or almost never.

Table 2. Sexual practices during masturbation by frequency of masturbation.

Pleasure, orgasmic response, and difficulty during masturbation

displays the experienced pleasure during masturbation. Only 3.8% of the participating women reported masturbating but not reaching orgasm. Orgasmic pleasure during masturbation was measured on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = not satisfying to 5 = very satisfying. For those who reach orgasm during masturbation approximately 60% of the participants rated their pleasure experience at high levels of satisfaction, and 22.6% rated it at a moderate level of satisfaction.

Table 3. If you masturbate (alone, without a partner present), how pleasurable or satisfying would you rate your typical orgasm?

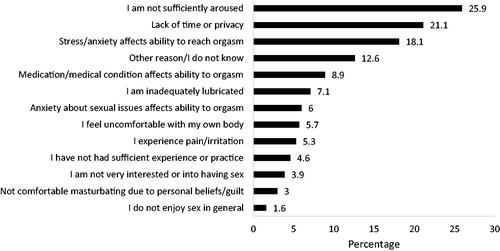

illustrates the percentage of identified contributing factors for those who are unable or have difficulty with reaching orgasm during masturbation: 25.9% identified not being sufficiently aroused, 21.1% named the lack of privacy, 18.1% reported experiencing stress and anxiety affecting orgasmic ability. Other reasons included medication or medical condition (8.9%), insufficient lubrication (7.1%), anxiety about sexual issues (6%), body image issues (5.7%), pain or irritation (5.3%), lack of practice (4.6%), lack of interest (3.9%), personal beliefs or guilt about masturbation (3%). 12.6% of the participating women reported not knowing the reason why they experience difficulties with reaching orgasm. The obtained qualitative data (asking participants choosing “other” to explain their choice) included mood problems such as lack of concentration and fatigue, preference for sexual activity with a person, but also medical issues relating to past sexual assault.

Figure 5. If you are unable to reach orgasm during masturbation (alone, without a partner present) or have difficulty doing so, what factors do you feel contribute to the problem?

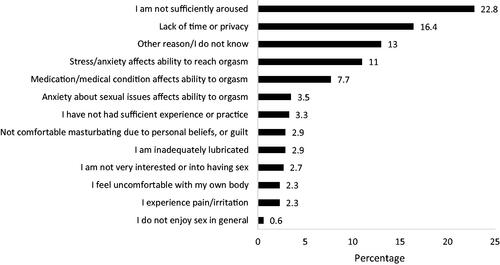

When choosing only one main factor contributing to orgasmic difficulties (unable or having difficulty with reaching orgasm during masturbation), the results showed slightly different percentages, but the top two reasons remained not being sufficiently aroused, 22.8% and the lack of privacy (16.4%), as per . Among participating women, 13% stated that they do not know the reason or have other specific reason.

Figure 6. If you are unable to reach orgasm during masturbation (alone, without a partner present) or have difficulty doing so, what is the ONE factor that you think contributes most to the problem?

When asked if the experienced difficulty or inability to reach orgasm causes distress (frustration, feeling upset or being bothered) rated on a 5-point scale (1 = almost never and 5= almost always) only 17.6% of the respondents stated that it almost never causes them distress and only 8.7% indicated that they almost always experience distress (see ).

Table 4. If you have difficulty or are unable to reach orgasm during masturbation (alone, without a partner present), does this bother, upset, or frustrate you?

Both the satisfaction with the orgasmic response and the distress associated to the inability or difficulty with reaching orgasm showed connection with masturbation frequency. The increased frequency of masturbation had a small positive correlation with satisfaction with orgasmic response (rs = 0.260, p < .001). Negative feelings associated with lack of ability to reach orgasm during masturbation were also associated with the frequency of masturbation (rs = 0.232, p < .001).

Relationship between sexual history, sexual arousal, orgasmic response and frequency of masturbation

displays correlations between factors around sexual history, sexual arousal and orgasmic response and the frequency of masturbation. Interest and importance of sex, as well as satisfaction with primary relationship (sexual or other) displayed small to moderate positive correlations with masturbation frequency (rs = 0.102–0.291, p < .01). There were only small correlations between specific difficulties encountered during masturbation and frequency of masturbation (rs = 0.102–0.291, p < .05). Masturbation frequency had some correlation with orgasmic response rated by participants, notably the length of time taken to reach orgasm during masturbation (rs = 0.216), and satisfaction with orgasm during masturbation (rs = 0.260). Difficulties with reaching orgasm during masturbation and associated frustrated feelings both showed some relationship with the frequency of masturbation (rs = −0.137, and rs = 0.232, respectively).

Table 5. Relationship between the frequency of masturbation and sexual history, sexual arousal, and orgasmic response.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to assess the masturbation practices of New Zealand women and enhance our understanding of why and how Aotearoa/New Zealand adult women engage in masturbatory behaviors and the connection of these factors with orgasmic pleasure, latency, and experienced difficulties during masturbation. The current study also investigated the differences between women who masturbate more frequently and those who tend to masturbate less frequently.

Masturbation frequency and correlating factors

The results show that 94.6% of the participating New Zealand women engaged in masturbation in their lifetime, and 76.1% at least once a month in the past 12–24 months. This number is similar to the findings of other recent studies on masturbation frequency finding high prevalence for female masturbation in Western societies (Baćak A & Štulhofer, Citation2011; Burri & Carvalheira, Citation2019; Gerressu et al., Citation2008; Herbenick et al., Citation2018; Richters et al., Citation2014; Rowland et al., Citation2019; Rowland, Hevesi, et al., Citation2020). Our sample was self-selected, which also probably results in higher prevalence than in the whole population.

Comparing the demographic variables of women with different reported masturbation frequency revealed that similar to previous research, younger women reported higher masturbation frequencies than older ones (Barr et al., Citation2002; Palacios‐Ceña et al., Citation2012). Such a difference has been explained in previous studies by a number of factors including better physical fitness (Jiannine & Reio, Citation2018), higher estradiol level (Bancroft, Citation2005; Motta-Mena & Puts, Citation2017), or holding more liberal attitudes toward masturbation (Driemeyer et al., Citation2017). In our study, however, the age difference was slight, probably due to relatively low proportion of older women.

The relationship between physical health and sexual health has been reported in many studies for various illnesses and age groups, indicating that sexual health problems are more prevalent in populations presenting with physical illnesses (Dorner et al., Citation2018). This is in line with our current findings that those who reported having current medical problems were less likely to masturbate frequently.

Reasons for masturbation

Various studies have shown that women favor a variety of motivations for masturbation (Carvalheira & Leal, Citation2013; Goldey et al., Citation2016; Rowland, Hevesi, et al., Citation2020). When asked about the reasons for masturbation, the majority (74.7%) of the New Zealand respondents identified sexual pleasure and satisfaction as a contributing reason. Indeed, most participating women (96.2%) experienced orgasm during masturbation, the majority (59.6%) indicating high levels of satisfaction with their experience.

At the same time, only a little more than half (51.6%) of the respondents chose pleasure and satisfaction as the most important reason for masturbating. Besides sexual pleasure, other highly endorsed reasons included stress relief and relaxation (60.7%), decreasing sexual tension (41.7%), or overcoming feelings of anxiety and/or depression (20.7%). Qualitative data indicated that women also use masturbation to improve various aspects of physical health—the responses included “toning pelvic floor,” “burn calories,” or “coping with chronic pain,” or psychological wellbeing, the reasons included “helps me reconnect with my body” by a former sexual assault victim, “helps me think clearly afterwards, and makes mental tasks less frustrating,” or “learn to orgasm.” These findings reiterate that masturbation serves many different purposes over a variety of populations/cultures, and that orgasm is not its sole purpose as had been traditionally assumed (Bowman, Citation2014; Carvalheira & Leal, Citation2013; Fahs & Frank, Citation2014; Goldey et al., Citation2016; Laumann et al., Citation1994; Rowland et al., Citation2019). The motivation behind masturbation is complex, and women engage in masturbation for a variety of physical and psychological reasons.

Stress relief and mental wellbeing

Stress relief and relaxation were rated as the second most common reason for masturbation, 60.7% of the surveyed women reported using masturbation as a form of stress relief as a contributing reason and 17.1% of the respondents reported masturbating primarily as a stress relief or a form of relaxation. Stress relief and relaxation as a reason for masturbation has been reported in many studies (Burri & Carvalheira, Citation2019; Carvalheira & Leal, Citation2013; Goldey et al., Citation2016; Laumann et al., Citation1994; Rowland, Hevesi, et al., Citation2020). Zamboni and Crawford (Citation2003) depicted that masturbatory frequency and masturbatory desire significantly correlated with experienced life stress. As relaxation has been proven to be an effective tool to reduce stress (Kaspereen, Citation2012; Rainforth et al., Citation2007; Rausch et al., Citation2006), and stress relief can be achieved via masturbation, masturbation can be used as a safe and effective tool to cope with daily stress.

Introducing pleasure and pleasurable activities as a form of depression treatment is well documented in the clinical literature (Barlow, Citation2014; Beck & Beck, Citation1995; Nathan & Gorman, Citation2015) and a widely used strategy in clinical practice, however, masturbation is rarely included in the list of recommended pleasurable activities. In our study women seem to know about this effect, as 20.7% women reported using masturbation to cope with feelings of anxiety or depression as contributing factor and 0.9% as a primary reason.

Sexual practices during masturbation

When investigating the sexual practices of New Zealand women during masturbation, clitoral stimulation was rated to be the most commonly used practice (76%), followed by vaginal stimulation (35.4%) but only 33% reported using mechanical aids, such as vibrators or dildos which is consistent with research indicating that many women do not rely on or even include vaginal penetration when they are masturbating (Fahs & Frank, Citation2014; Herbenick et al., Citation2018; Rowland, Hevesi, et al., Citation2020), providing another piece of evidence against the traditional phallocentric view of female sexuality.

There were observed differences in sexual practices between women who masturbate frequently, less frequently or never: the current study has shown that those New Zealand women who engage in masturbation frequently are more likely to incorporate clitoral, vaginal, breast and anal stimulation into their masturbatory behaviors, compared to those who masturbate less frequently or almost never (see ) so, it seems that the more someone masturbates, the more likely that they involve a variety of practices during masturbation.

Cognitive factors, such as sexual fantasy, tend to play an important role in masturbation for the participating New Zealand women as 43.4% indicated engaging in sexual fantasies during masturbation. In their review article, Leitenberg and Henning (Citation1995) observed high prevalence of fantasy during masturbation: between 31% and 65% of females in various studies reported fantasizing during masturbation. Zamboni and Crawford (Citation2003) found significant correlation between masturbatory frequency and sexual fantasy and Yule et al. (Citation2017) report that even asexual women engage in sexual fantasies, however according to Nutter and Condron (Citation1983) females with inhibited sexual desire fantasize significantly less than sexually satisfied controls during masturbation. The content of the sexual fantasies can vary widely, in the current study 24.4% of participating women reported fantasizing about their partner and 19% reported not including their partner in their sexual fantasies.

Orgasmic response and difficulty during masturbation

Even though most participating women reported high orgasmic pleasure during masturbation, approximately 10% of the participants either could not reach orgasm during masturbation or rated the orgasm as not satisfying. Orgasmic difficulties can be relatively common for women; Female Orgasmic Disorder is reported to be the second most common sexual problem for women (Meston et al., Citation2004). In the current study, the primary identified reason for experiencing orgasmic difficulty was the lack of sexual arousal. The role of sexual arousal in orgasmic response has been well known since Masters and Johnson (Citation1966) described the female sexual response and identified sexual arousal as an important contributing factor, which has been confirmed in various studies since (Carvalheira et al., Citation2010; Walton & Bhullar, Citation2018). However, environmental factors can also play an important role in orgasmic difficulty: more than one-fifth of the participating women disclosed that the lack of privacy prevented them from reaching orgasm during masturbation. The third most common reason for experiencing orgasmic difficulty was stress and anxiety. Other studies have shown that heightened level of anxiety can increase the likelihood of orgasmic difficulties (De Lucena & Abdo, Citation2014; Hevesi et al., Citation2020). The obtained qualitative data included mood-related problems, lack of concentration and fatigue, preference for sexual activity with a person, but also medical issues relating to past sexual assault.

Despite orgasmic difficulties, experiencing difficulty or even inability to reach orgasm seem to have little importance in the masturbatory experience for many women, as 17.6% of the participating women indicated that not reaching orgasm does not bother, upset or frustrate them at all and only 8.7% participants indicated that it is a problem for them. This could be a reciprocating problem, whereby women who experience difficulty tend to minimize the importance of reaching orgasm, often the result of ensuring cognitive consonance.

Relationship between the frequency of masturbation and orgasmic response

Not surprisingly, experiencing orgasm has an impact on masturbation frequency: we have found that those women who frequently experience orgasm during sexual activities, including masturbation, are more likely to masturbate frequently which is in line with previous findings (Rowland, Kolba, et al., Citation2020), and those who typically reach orgasm within 15 min or less were almost twice as likely to masturbate more frequently.

Both the satisfaction with the orgasmic response and the distress associated to orgasmic difficulty showed connection with masturbation frequency: those women who tend to masturbate more frequently tend to be more satisfied with their orgasmic response but also tend to experience more frustration or distress when they cannot reach orgasm. Women who masturbate more frequently reported needing more time to reach orgasm during masturbation but also rated their orgasmic response more satisfying. A possible explanation is that those women who enjoy masturbating will masturbate more frequently and will also make the experience last longer.

As delayed orgasm is often associated with decreased sexual interest (Humble & Bejerot, Citation2016) or a form of sexual dysfunction (Jenkins & Mulhall, Citation2015) or a side effect of SSRIs medication (Higgins, Citation2010), it remains a controversial topic in sexual psychology. The current research found that those women who tend to masturbate less frequently tend to experience more difficulties with reaching orgasm and have increasing feelings of frustration regarding their orgasmic difficulties, possibly viewing delayed orgasm as sexual dysfunction or difficulty. It might be that when the orgasm is extended deliberately to enhance sexual pleasure, the sense of control is still maintained, and it reflects a positive experience; however, when orgasmic delay is perceived as an orgasmic difficulty and accompanied by the lack of control, it reflects a negative sexual experience. Further research is needed to explore these differences in delayed female orgasm.

In conclusion, the relatively high reported masturbation rates among New Zealand women, compared to other countries, puts New Zealand among the liberal sexual cultures, where masturbation is an accepted sexual behavior for women. This might be due to the bicultural nature of the country, where the indigenous, liberal Māori culture and the traditional, often Christianity-based British culture are influencing each other. New Zealand women give similar reasons for the practice as their Western counterparts, and as their sexual practices during masturbation indicate, they display similar masturbatory behaviors compared to US and Hungarian women. Overall, the results of this study were broadly congruent with findings in similar studies on female masturbation, while providing new insights into masturbation rates and practices in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

Strengths and limitations

The current study is the first of its kind to measure masturbatory practices of New Zealand women and it may be a valuable starting point for large scale studies. This study may also serve as evidence to clinicians working in the field of sexual health that masturbatory behaviors seem to be very common for women in Aotearoa/New Zealand.

The current study had a relatively large sample size and wide distribution drawn from New Zealand/Aotearoa, including all age groups over 18 regardless of sexual orientation, physical location, or socioeconomic background. The anonymity of the research was aimed at reducing the factors related to social desirability and improving the openness in responding, allowing participants to express their opinion about sensitive topics (Ong & Weiss, Citation2000), such as masturbation or sexual practices and most likely contributed to many women feeling comfortable disclosing masturbatory behaviors.

However, some limitations should also be acknowledged. Firstly, the possibility of systematic bias, which is a common limitation for any non-probability study, characterized our research as well, it is most likely that potential participants from lower socioeconomic status or elderly people with lower computer literacy have less access to online survey which limits the generalizability of the results. Even though the study is not representative of the population profile, as Māori, Pasifika and Asian population were underrepresented (Stats New Zealand, Citation2019), it is more diverse than many studies of this sort. Nevertheless, given the underrepresentation of specific cultural-ethnic groupings, the current study did not allow a comparative analysis of masturbation practices across these groups. Future studies may want to target minority populations to include a more representative sample via community sampling, and include more information related to women’s sexual histories, such as age of first intercourse, age of first masturbation, and history of abuse that might impact masturbatory patterns. Another possible future study would explore the differences between individuals with varying sexual orientations and gender identities. In our research, the sample of different orientations was too small to conduct any meaningful analyses, a separate research study focused solely on queer and non-binary orientations would be warranted here. Clinical practice suggests that mood and anxiety affect sexual practices, including masturbation. However, our research addressed this aspect using a single binary question which was not sufficient to establish such relationship. Future research could explore the relationship between masturbation frequencies, and, for example, the severity of depression, by using psychometric assessment tools such as the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI-II), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) or the Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS).

Despite the limitations, the current study represents a valuable contribution to the field of sexual psychology, and the findings of this research may inform policy makers developing the sexual education curriculum in Aotearoa/New Zealand or even in Oceanic countries having similar cultures, as well as clinical practice and future research on female sexuality.

IRB statement

All research methods were approved by and conducted in accordance with the ethical requirements of the Auckland University of Technology Ethics Board (AUTEC no. 18/96).

Disclosure statement

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Data availability statement

Raw data were generated at Auckland University of Technology. Derived data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author R.C. on request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aneja, J., Grover, S., Avasthi, A., Mahajan, S., Pokhrel, P., & Triveni, D. (2015). Can masturbatory guilt lead to severe psychopathology: A case series. Indian Journal of Psychological Medicine, 37(1), 81–86. https://doi.org/10.4103/0253-7176.150848

- Aspin, C., & Hutchings, J. (2007). Reclaiming the past to inform the future: Contemporary views of Maori sexuality. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 9(4), 415–427. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050701195119

- Atwood, J. D., & Gagnon, J. (1987). Masturbatory behavior in college youth. Journal of Sex Education and Therapy, 13(2), 35–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/01614576.1987.11074907

- Baćak A, V., & Štulhofer, A. (2011). Masturbation among sexually active young women in Croatia: Associations with religiosity and pornography use. International Journal of Sexual Health, 23(4), 248–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2011.611220

- Bancroft, J. (2005). The endocrinology of sexual arousal. The Journal of Endocrinology, 186(3), 411–427. https://doi.org/10.1677/joe.1.06233

- Bancroft, J., Herbenick, D., & Reynolds, M. (2003). Masturbation as a marker of sexual development. In J. Bancroft (Ed.), Sexual development in childhood (pp. 156–185). Indiana University Press.

- Barlow, D. (2014). Clinical handbook of psychological disorders: A step-by-step treatment manual. The Guilford Press.

- Barr, A., Bryan, A., & Kenrick, D. T. (2002). Sexual peak: Socially shared cognitions about desire, frequency, and satisfaction in men and women. Personal Relationships, 9(3), 287–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6811.09305

- Beck, J. S., & Beck, A. T. (1995). Cognitive therapy: Basics and beyond. Guilford Press.

- Both, S., & Laan, E. (2008). Directed masturbation: A treatment of female orgasmic disorder. In W. T. O’Donohue & J. E. Fisher (Eds.), Cognitive behavior therapy: Applying empirically supported techniques in your practice (pp. 158–166). John Wiley & Sons.

- Bowman, C. P. (2014). Women’s masturbation: Experiences of sexual empowerment in a primarily sex-positive sample. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684313514855

- Brecher, E. M. (1984). Love, sex, and aging: A Consumers Union report. Consumers Union US.

- Bretschneider, J. G., & McCoy, N. L. (1988). Sexual interest and behavior in healthy 80- to 102-year-olds. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 17(2), 109–129. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01542662

- Brickell, C. (2007). Sex education, homosexuality, and social contestation in 1970s New Zealand. Sex Education, 7(4), 387–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810701635988

- Brindis, C. D. (2006). A public health success: Understanding policy changes related to teen sexual activity and pregnancy. Annual Review of Public Health, 27(1), 277–295. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.27.021405.102244

- Bullough, V. L. (2003). Masturbation: A historical overview. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2-3), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v14n02_03

- Bullough, V. L., & Bullough, B. (2019). Sin, sickness and sanity: A history of sexual attitudes. Routledge.

- Burri, A., & Carvalheira, A. (2019). Masturbatory behavior in a population sample of German women. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(7), 963–974. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.04.015

- Carvalheira, A. A., Brotto, L. A., & Leal, I. (2010). Women's motivations for sex: Exploring the diagnostic and statistical manual, fourth edition, text revision criteria for hypoactive sexual desire and female sexual arousal disorders. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(4), 1454–1463. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2009.01693.x

- Carvalheira, A., & Leal, I. (2013). Masturbation among women: Associated factors and sexual response in a Portuguese community sample. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(4), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.628440

- Chi, X., Bongardt, D. V. D., & Hawk, S. T. (2015). Intrapersonal and interpersonal sexual behaviors of Chinese university students: Gender differences in prevalence and correlates. Journal of Sex Research, 52(5), 532–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.914131

- Chowdhury, M., Khan, R. H., Chowdhury, M. R. K., Nipa, N. S., Kabir, R., Moni, M. A., & Kordowicz, M. (2019). Masturbation experience: A case study of undergraduate students in Bangladesh. Journal of Population and Social Studies, 27(4), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.25133/JPSSv27n4.024

- Coleman, E. (2003). Masturbation as a means of achieving sexual health. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2-3), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v14n02_02

- Coleman, E. J., & Bockting, W. O. (2013). Masturbation as a means of achieving sexual health. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315808789

- Das, A., Parish, W. L., & Laumann, E. O. (2009). Masturbation in urban China. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(1), 108–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9222-z

- Davidson, J. K., & Darling, C. A. (1993). Masturbatory guilt and sexual responsiveness among post-college-age women: Sexual satisfaction revisited. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 19(4), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239308404372

- De Lucena, B. B., & Abdo, C. H. N. (2014). Personal factors that contribute to or impair women’s ability to achieve orgasm. International Journal of Impotence Research, 26(5), 177–181. https://doi.org/10.1038/ijir.2014.8

- Dorner, T. E., Berner, C., Haider, S., Grabovac, I., Lamprecht, T., Fenzl, K. H., & Erlacher, L. (2018). Sexual health in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and the association between physical fitness and sexual function: A cross-sectional study. Rheumatology International, 38(6), 1103–1114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00296-018-4023-3

- Driemeyer, W., Janssen, E., Wiltfang, J., & Elmerstig, E. (2017). Masturbation experiences of Swedish senior high school students: Gender differences and similarities. Journal of Sex Research, 54(4-5), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1167814

- Edwards, W. M., & Coleman, E. (2004). Defining sexual health: A descriptive overview. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 33(3), 189–195. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:ASEB.0000026619.95734.d5

- Ellison, C. R. (2000). Women's sexualities: Generations of women share intimate secrets of sexual self-acceptance.

- Fahs, B., & Frank, E. (2014). Notes from the back room: Gender, power, and (in)visibility in women's experiences of masturbation. Journal of Sex Research, 51(3), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.745474

- Fisher, S. (1973). The female orgasm: Psychology, physiology, fantasy. Basic Books.

- Fisher, C. M., Kauer, S., Mikolajczak, G., Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Bellamy, R., Waling, A., & Lucke, J. (2020). Prevalence rates of sexual behaviors, condom use, and contraception among Australian heterosexual adolescents. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(12), 2313–2321.

- Freud, S. (2012). The basic writings of Sigmund Freud. Modern library.

- Gerressu, M., Mercer, C. H., Graham, C. A., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A. M. (2008). Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors in a British National Probability Survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(2), 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9123-6

- Goldey, K. L., Posh, A. R., Bell, S. N., & van Anders, S. M. (2016). Defining pleasure: A focus group study of solitary and partnered sexual pleasure in queer and heterosexual women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 45(8), 2137–2154. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0704-8

- Gooder, C. (2016). To know the facts' the New Zealand Health Department's sex education pamphlets. New Zealand Journal of History, 50(1), 1955–1983. 109–133.

- Heiman, J. R., LoPiccolo, J., & Piccolo, L. L. (2010). Becoming orgasmic: A sexual and personal growth programme for women. Hachette UK.

- Herbenick, D., Fu, T.-C., Arter, J., Sanders, S. A., & Dodge, B. (2018). Women's experiences with genital touching, sexual pleasure, and orgasm: Results from a U.S. probability sample of women ages 18 to 94. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1346530

- Herbenick, D., Reece, M., Schick, V., Sanders, S. A., Dodge, B., & Fortenberry, J. D. (2010). Sexual behavior in the United States: Results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14–94. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 7(s5), 255–265. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02012.x

- Hevesi, K., Gergely Hevesi, B., Kolba, T. N., & Rowland, D. L. (2020). Self-reported reasons for having difficulty reaching orgasm during partnered sex: relation to orgasmic pleasure. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 41(2), 106–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/0167482X.2019.1599857

- Higgins, A., Nash, M., & Lynch, A. M. (2010). Antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction: Impact, effects, and treatment. Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety, 2, 141–150. https://doi.org/10.2147/DHPS.S7634

- Hogarth, H., & Ingham, R. (2009). Masturbation among young women and associations with sexual health: An exploratory study. Journal of Sex Research, 46(6), 558–567. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490902878993

- Humble, M. B., & Bejerot, S. (2016). Orgasm, serotonin reuptake inhibition, and plasma oxytocin in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Gleaning from a distant randomized clinical trial. Sexual Medicine, 4(3), e145–e155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esxm.2016.04.002

- Jackson, S., & Weatherall, A. (2010). Dilemmas of delivery: Gender, health and formal sexuality education in New Zealand/Aotearoa classrooms. Women's Studies Journal, 24(1), 47.

- Jenkins, L. C., & Mulhall, J. P. (2015). Delayed orgasm and anorgasmia. Fertility and Sterility, 104(5), 1082–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.09.029

- Jiannine, L. M., & Reio, T. G. Jr. (2018). The physiological and psychological effects of exercise on sexual functioning: A literature review for adult health education professionals. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 30(2), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1002/nha3.20211

- Jing, S., Lay, A., Weis, L., & Furnham, A. (2018). Attitudes toward, and use of, vibrators in China. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 44(1), 102–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2017.1321600

- Johnson, B. K. (1998). A correlational framework for understanding sexuality in woman age 50 and over. Health Care for Women International, 19(6), 553–564. https://doi.org/10.1080/073993398246115

- Kaspereen, D. (2012). Relaxation intervention for stress reduction among teachers and staff. International Journal of Stress Management, 19(3), 238–250. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029195

- Kinsey, A. C., Martin, C. E., & Pomeroy, W. B. (1948). Sexual behaviour in the human male. WB Saunders Co.

- Kinsey, A. C., Pomeroy, W. B., Martin, C. E., & Gebhard, P. H. (1953). Sexual behavior in the human female. WB Saunders Co.

- Komisaruk, B. R., & Whipple, B. (1995). The suppression of pain by genital stimulation in females. Annual Review of Sex Research, 6(1), 151–186. https://doi.org/10.1080/10532528.1995.10559904

- Kontula, O., & Haavio-Mannila, E. (2003). Masturbation in a generational perspective. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2–3), 49–83. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v14n02_05

- Kraus, F. (2017). The practice of masturbation for women: The end of a taboo? Sexologies, 26(4), e35–e41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2017.09.009

- Laan, E., & Rellini, A. H. (2011). Can we treat anorgasmia in women? The challenge to experiencing pleasure. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 26(4), 329–341. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2011.649691

- Langfeldt, T. (1981). Childhood masturbation: Individual and social organization. In L. L. Constantine & F. M. Martinson (Eds.), Children and sex (pp. 63–74). Little, Brown and Co.

- Laqueur, T. W. (2003). Solitary sex: A cultural history of masturbation. Zone Books.

- Lastella, M., O'Mullan, C., Paterson, J. L., & Reynolds, A. C. (2019). Sex and sleep: Perceptions of sex as a sleep promoting behavior in the general adult population. Frontiers in Public Health, 7, 33. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00033

- Laumann, E. O., Gagnon, J. H., Michael, R. T., & Michaels, S. (1994). The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. University of Chicago Press.

- Lavie-Ajayi, M., & Joffe, H. (2009). Social representations of female orgasm. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308097950

- Leitenberg, H., & Henning, K. (1995). Sexual fantasy. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 469–496. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.469

- Leonard, A. (2010). An investigation of masturbation and coping style [Paper presentation]. 38th Annual Western Pennsylvania Undergraduate Psychology Conference.

- Levin, R. J. (2007). Sexual activity, health and well-being – The beneficial roles of coitus and masturbation. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 22(1), 135–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990601149197

- Maines, R. P. (1999). The technology of orgasm: "Hysteria," the vibrator, and women's sexual satisfaction. JHU Press.

- Masters, W. H., & Johnson, V. E. (1966). Human sexual response. Brown.

- McCarthy, B. W. (2004). An integrative cognitive-behavioral approach to understanding, assessing, and treating female sexual dysfunction. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 15(3), 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1300/J085v15n03_02

- Meston, C. M., Levin, R. J., Sipski, M. L., Hull, E. M., & Heiman, J. R. (2004). Women's orgasm. Annual Review of Sex Research, 15(1), 173–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10532528.2004.10559820

- Meston, C. M., Trapnell, P. D., & Gorzalka, B. B. (1998). Ethnic, gender, and length‐of‐residency influences on sexual knowledge and attitudes. Journal of Sex Research, 35(2), 176–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499809551931

- Ministry of Education. (1999). Health and physical education in the New Zealand curriculum. Learning Media Limited.

- Ministry of Health. (2003). Sexual and Reproductive Health: A resource book for New Zealand health care organisations. Ministry of Health. http://www.moh.govt.nz/

- Ministry of Health. (2010). A compact guide to sexual health. Ministry of Health. https://www.healthed.govt.nz/system/files/resource-files/HE1438_1.pdf

- Motta-Mena, N. V., & Puts, D. A. (2017). Endocrinology of human female sexuality, mating, and reproductive behavior. Hormones and Behavior, 91, 19–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.yhbeh.2016.11.012

- Nathan, P. E., & Gorman, J. M. (2015). A guide to treatments that work. Oxford University Press.

- New Zealand Family Planning. (2017). Sexual and reproductive health and rights in New Zealand: Briefing to incoming members of parliament. New Zealand Family Planning.

- Nutter, D. E., & Condron, M. K. (1983). Sexual fantasy and activity patterns of females with inhibited sexual desire versus normal controls. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 9(4), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926238308410914

- Ong, A. D., & Weiss, D. J. (2000). The impact of anonymity on responses to sensitive questions. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 30(8), 1691–1708. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2000.tb02462.x

- Palacios‐Ceña, D., Carrasco‐Garrido, P., Hernández‐Barrera, V., Alonso‐Blanco, C., Jiménez‐García, R., & Fernández‐de‐las‐Peñas, C. (2012). Sexual behaviors among older adults in Spain: Results from a population‐based national sexual health survey. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 9(1), 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02511.x

- Phillips, N. A. (2000). Female sexual dysfunction: Evaluation and treatment. American Family Physician, 62(1), 127–136.

- Pinkerton, S. D., Bogart, L. M., Cecil, H., & Abramson, P. R. (2003). Factors associated with masturbation in a collegiate sample. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2–3), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v14n02_07

- Rainforth, M. V., Schneider, R. H., Nidich, S. I., Gaylord-King, C., Salerno, J. W., & Anderson, J. W. (2007). Stress reduction programs in patients with elevated blood pressure: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Hypertension Reports, 9(6), 520–528. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11906-007-0094-3

- Rausch, S. M., Gramling, S. E., & Auerbach, S. M. (2006). Effects of a single session of large-group meditation and progressive muscle relaxation training on stress reduction, reactivity, and recovery. International Journal of Stress Management, 13(3), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.13.3.273

- Reyes, D. V. (2016). Conundrums of desire: Sexual discourses of mexican-origin mothers. Sexuality & Culture, 20(4), 1020–1041. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-016-9372-z

- Richters, J., de Visser, R. O., Badcock, P. B., Smith, A. M. A., Rissel, C., Simpson, J. M., & Grulich, A. E. (2014). Masturbation, paying for sex, and other sexual activities: The Second Australian study of health and relationships. Sexual Health, 11(5), 461–471. https://doi.org/10.1071/SH14116

- Robbins, C. L. (2011). Prevalence, frequency, and associations of masturbation with partnered sexual behaviors among US adolescents. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(12), 1087. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.142

- Rosen, R., Brown, C., Heiman, J., Leiblum, S., Meston, C., Shabsigh, R., Ferguson, D., & D'Agostino, R. (2000). The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): A multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 26(2), 191–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/009262300278597

- Rowland, D. L., & Cooper, S. E. (2017). Treating men's orgasmic difficulties. In Z. D. Peterson (Ed.), The Wiley handbook of sex therapy (pp. 72–97). Wiley Online Books. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118510384.ch6

- Rowland, D., Donarski, A., Graves, V., Caldwell, C., Hevesi, B., & Hevesi, K. (2019). The experience of orgasmic pleasure during partnered and masturbatory sex in women with and without orgasmic difficulty. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45(6), 550–561. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2019.1586021

- Rowland, D. L., Hevesi, K., Conway, G. R., & Kolba, T. N. (2020). Relationship between masturbation and partnered sex in women: Does the former facilitate, inhibit, or not affect the latter? The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 17(1), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.10.012

- Rowland, D. L., Kolba, T. N., McNabney, S. M., Uribe, D., & Hevesi, K. (2020). Why and how women masturbate, and the relationship to orgasmic response. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 46(4), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1717700

- Rowland, D. L., Sullivan, S. L., Hevesi, K., & Hevesi, B. (2018). Orgasmic latency and related parameters in women during partnered and masturbatory sex. J Sex Med, 15(10), 1463–1471. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2018.08.003

- Ruan, F. F. (1991). Sex in China: Studies in sexology in Chinese culture. Springer Science & Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0609-0

- Saliares, E., Wilkerson, J. M., Sieving, R. E., & Brady, S. S. (2017). Sexually experienced adolescents’ thoughts about sexual pleasure. The Journal of Sex Research, 54(4–5), 604–618. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1170101

- Shekarey, A., Rostami, M. S., Mazdai, K., & Mohammadi, A. (2011). Masturbation: Prevention & treatment. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1641–1646. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.318

- Smith, L. J., Mulhall, J. P., Deveci, S., Monaghan, N., & Reid, M. C. (2007). Sex after seventy: A pilot study of sexual function in older persons. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 4(5), 1247–1253. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1743-6109.2007.00568.x

- Stats New Zealand. (2019). New Zealand’s population reflects growing diversity. S. N. Zealand. https://www.stats.govt.nz/news/new-zealands-population-reflects-growing-diversity

- Towne, A. (2019). Clitoral stimulation during penile-vaginal intercourse: A phenomenological study exploring sexual experiences in support of female orgasm. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 28(1), 68–80. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2018-0022

- Tuohy, F., & Murphy, M. (1976). Down under the plum trees. A. Taylor. http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/interactive/30858/down-under-the-plum-trees

- Verma, K. K., Khaitan, B. K., & Singh, O. P. (1998). The frequency of sexual dysfunctions in patients attending a sex therapy clinic in North India. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 27(3), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1018607303203

- Walton, M. T., & Bhullar, N. (2018). Hypersexuality, higher rates of intercourse, masturbation, sexual fantasy, and early sexual interest relate to higher sexual excitation/arousal. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(8), 2177–2183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1230-7

- Watson, L. R. (2016). Evil habits New Zealand anti-masturbation fervour, 1860s-1960s. New Zealand Journal of History, 50(1), 47–68.

- Weir, K. (2001). Sexuality education: The values education debate continues. New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 10, 109–123.

- Wells, B. E., & Twenge, J. M. (2005). Changes in young people's sexual behavior and attitudes, 1943–1999: A cross-temporal meta-analysis. Review of General Psychology, 9(3), 249–261. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.249

- Willis, M., Jozkowski, K. N., Lo, W. J., & Sanders, S. A. (2018). Are women's orgasms hindered by phallocentric imperatives? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 47(6), 1565–1576. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1149-z

- World Health Organization. (1975). WHO technical report series No. 572: Education and treatment in human sexuality: the training of health professionals (9241205725). WHO.

- World Health Organization. (2017). Sexual health and its linkages to reproductive health: An operational approach (9241512881). WHO.

- Yu, J. (2010). Young people of Chinese origin in western countries: A systematic review of their sexual attitudes and behaviour. Health & Social Care in the Community, 18(2), 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2009.00906.x

- Yule, M. A., Brotto, L. A., & Gorzalka, B. B. (2017). Sexual fantasy and masturbation among asexual individuals: An in-depth exploration. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(1), 311–328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0870-8

- Zamboni, B. D., & Crawford, I. (2003). Using masturbation in sex therapy. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 14(2–3), 123–141. https://doi.org/10.1300/J056v14n02_08

- Zimmer, F., & Imhoff, R. (2020). Abstinence from masturbation and hypersexuality. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(4), 1333–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01623-8