Abstract

Objectives

We tested whether social activities and interactions as part of a condom campaign strengthened young adults’ condom-use intentions and normative perceptions of condoms compared to simple exposure to campaign information.

Method

Data from 3,041 young adults collected after four annual condom campaigns were analyzed and combined into a meta-analysis.

Results

Interaction about the campaign and engagement in campaign-related activities was associated with higher condom use intention and more positive pro-condom norms.

Conclusions

The authors call for a greater emphasis on social influence in youth-aimed sexual health campaigns. Implications for the research are discussed.

Considering the social nature of human beings, it is crucial to understand the role of socialization when reviewing sexual health promotion programs (Braeken & Cardinal, Citation2008). Despite abundant evidence for the impact of social norms on sexual behavior (see Huebner et al., Citation2011; Scholly et al., Citation2005), open and honest communication about norms in sexual settings is often still lacking (Noar et al., Citation2006; Rader et al., Citation2021) or even considered taboo (Abel & Fitzgerald, Citation2006). Young adults are, therefore, often left to rely on biased norms that are introduced through exposure to sexually explicit media (Wright et al., Citation2016, 2019) or that are inferred through sexist conversations (Koudenburg et al., Citation2020). Despite evidence capturing the positive effect of social factors in sexual health interventions (i.e., Figueroa et al., Citation2014; Noar et al., Citation2006), interventions lack components that affect social norms and social structure (Charania et al., Citation2010).

This study aims to examine whether social engagement in a condom campaign can improve social norms, intentions, and risk perceptions related to condom use in young adults. In our research, social campaign engagement is conceptualized by interaction about campaign information or participation in condom-themed campaign activities. These activities may be verbal or nonverbal, yet they allow learning through socializing. Research has established that communication about sexual health stimulates preventative sexual health behavior such as condom use (Noar et al., Citation2006; Sales et al., Citation2012), STI testing, and treatment seeking (Hoffman et al., Citation2019; Reddy et al., Citation2000) as well as a decrease in the number of sexual partners (Figueroa et al., Citation2014) among young adults. Even nonverbal activities such as participating in a video game or watching a web-based video can change sexual health behavior among adolescents (Fiellin et al., Citation2017; Gragnano & Miglioretti, Citation2017) through observational learning. Hence, we argue that young adults’ sexual health beliefs and condom use intentions may be altered through peer interaction but also through engagement in verbal or nonverbal social activities through observational learning, compared to being provided with information about sexual health or the risks of unsafe sex. In our research, we will use the term young adults to refer to the age group of our sample (18-25-year-olds, Society for Adolescent Health & Medicine, 2017).

The spread of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) poses a severe challenge to sexual and reproductive health globally (World Health Organization, Citation2024). Still, condoms offer a highly effective prevention method when used correctly and consistently. Contrary to common misconceptions, STI epidemics are not a result of reckless sexual behavior but rather due to a lack of awareness, access to healthcare, and the persistent societal stigma surrounding condoms (The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, Citation2022). Moreover, decisions to engage in safe sex are often hindered by unfavorable social norms around condom use and sexual health behavior (Abel & Fitzgerald, Citation2006; Chang, Citation2014).

The effect of social norms on beliefs and behavior

Social norms are standards of acceptable behavior widely agreed upon within a particular society or culture. Social norms are transmitted explicitly through conversation and implicitly through observation and imitation of others’ behavior (Cialdini & Trost, Citation1998). At the same time, perceived social norms are focal drivers of people’s thoughts and actions. We use them to make sense of our social surroundings and to modify our behavior accordingly, which is a central perspective of social learning theory (Bandura, Citation1977). Perceived social norms are descriptive and injunctive: perceived descriptive norms are notions of the commonality of a particular behavior, and perceived injunctive norms describe the social appropriateness of a behavior (Cialdini et al., Citation1990; Spears, Citation2021). In social psychology, descriptive norms have been documented as strong predictors of risky health behavior among adolescents (Wang et al., Citation2019). For instance, adolescents are more likely to engage in binge drinking when they perceive their schoolmates to do so (Lynch et al., Citation2015; Perkins, Citation2003) and to exhibit less restrictive sexual behavior when they believe that it is consistent with peer behavior (Coley et al., Citation2013). Correspondingly, young adults alter their sexual behavior to dovetail with peer sexual behavior, even when deemed risky (Lewis et al., Citation2014)

In a study by Wang et al. (Citation2019), adolescents were more prone to behave according to the descriptive social norms of a restrictive friend group than of a permissive family. This finding highlights that people’s behaviors are especially likely to be influenced by others who share the most relevant social identity in a specific context (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). While the opinions of family members may be imperative in certain facets of life, e.g., social or political issues (Degner & Dalege, Citation2013), sexual behavior and beliefs are most relevant in relationships with peers and, therefore, more likely to be guided by peer norms (Peҫi, Citation2017). Indeed, youth perceptions of descriptive and injunctive peer norms have been identified as effective cues to sexual behaviors and beliefs (Chia, Citation2006; Tseng et al., Citation2020; van de Bongardt et al., Citation2015, Citation2017), and a link between social influence and sexual risk perception and behavior in young adults is established by several scientific studies (Cherie & Berhane, Citation2012; Macleod & Jearey-Graham, Citation2015; Wang et al., Citation2011).

Unfortunately, perceptions of peer norms are not always accurate. Research has shown that young adults often overestimate how much alcohol their peers consume (Prentice & Miller, Citation1993; Scholly et al., Citation2005) and that the perception of peer substance use is often biased (Henry et al., Citation2011; Perkins, Citation2003). Contrary to other social behavior, sexual behavior is not directly observable and is particularly prone to inferences based on peer conversations. Consequently, young adults tend to overestimate how sexually active their peers are (Chia & Lee, Citation2008), the frequency with which their peers engage in risky sexual behavior (Lewis et al., Citation2014; Scholly et al., Citation2005), and how comfortable peers are engaging in various sexual activities with hookups (Lambert et al., Citation2003). While young adults tend to rely on friends as one of the primary sources of sexual health information (Chia, Citation2006; Trinh et al., Citation2014) they generally finding it challenging to communicate honestly about sex with peers (Chang, Citation2014; Noar et al., Citation2006). As a result, sexual norms are also shaped (and biased) by sex-related mass media (Chia, Citation2006; Chia & Lee, Citation2008) or, as some research suggests, locker room talk (Simeone & Jeglic, Citation2019).

Norm-based interventions have been widely applied and tested to curb the adverse effects of exaggerated norm perceptions. Such interventions are especially potent in cases where norm perceptions are based on beliefs about norms rather than actual descriptive norms (Miller & Prentice, Citation2016). Since young people’s sexual behavior and beliefs are especially susceptive to false norm perceptions, sexual health campaigns should gain a lot from improving the accuracy of norm perceptions (Chang, Citation2014). The current research, therefore, focuses on the question of how norms about sexual behavior, and specifically condom use, develop and are maintained among the young adult population. It uses insights from both cultural and social psychology that point to a pivotal role of peer-to-peer communication in norm formation (Clark & Brennan, Citation1991; Kashima et al., Citation2013; Koudenburg et al., Citation2017; Miller & Prentice, Citation2016; Perkins, Citation2003; Postmes et al., Citation2000, Citation2005).

The role of interactions in constructing social norms

Through the social transmission of information, members of a culture come to a shared understanding of the world in terms of attitudes, ideas, and beliefs (Clark & Kashima, Citation2007; Kashima, Citation2008). Mutual understanding is established when people share and confirm one another’s beliefs and knowledge through interactions, in a process called grounding (Clark & Brennan, Citation1991; Kashima et al., Citation2013). Members of a culture may also distribute cultural information through social practices: by observing other culture members’ behavior, people pick up on social norms. Once an idea is socially grounded within a culture, it informs people’s behavior and norms (Kashima et al., Citation2007).

Essential for our research is the suggestion that cultural information is grounded in two means through which communicators reach their shared goal of establishing common ground. First, they engage in (1) practices that lead them toward the shared goal, and second, they make use of (2) communication to coordinate and maintain ideas and knowledge about the practices that help them to reach the shared goal (Clark & Brennan, Citation1991; Kashima et al., Citation2013). Importantly, achieving common ground tells us something about the subject agreed upon and implicitly points to the existence of a collective of people that agrees (Kashima et al., Citation2007; Koudenburg et al., Citation2017).

The suggestion that grounding processes are contingent upon people sharing a social group membership is central to social psychological theorizing. This relation is bidirectional: when people experience common ground on a topic, they tend to assume a shared group membership, and vice versa; a shared group membership motivates the development of common ground (Swaab et al., Citation2007). While most research focuses on actual discussions of the topics at hand, recent research suggests that the experience of common ground can also develop rather implicitly; by engaging in joint activities or smooth conversation, people may experience a sense of mutual understanding (Kashima et al., Citation2007; Koudenburg et al., Citation2015, Citation2017). Such findings validate the cultural perspective that communication and joint activities are fundamental to forming social norms.

Notably, the inferences of social norms in a particular interaction within a specific group of young adults are easily generalized to norm perceptions about the whole population of young adults (Chia & Lee, Citation2008; Koudenburg et al., Citation2020; Meeussen & Koudenburg, Citation2022). Indeed, cultural perspectives have pointed to interpersonal communication as the accelerator of changing social or cultural norms (Kashima, Citation2008, Citation2014; Kashima et al., Citation2007).

The campaign “only with a condom”

The objective of the current study is to examine the role of peer-to-peer interaction and joint activities in changing norms, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions regarding condom use. This is done in the context of an extensive sexual health campaign targeting young adults in Denmark during the years 2011-2014. With assistance from the Danish Family Planning Association (DFPA), the Danish Health Authority ran a national and annual two-week condom campaign between 2009 and 2018. The DFPA has reached credibility in Denmark by attending expert debates on sexual health in public media, providing sexual education in Danish schools, and providing educational resources for teachers. The purpose of the campaign was to increase condom use in Danish young adults and to create awareness about the risks of unprotected sex. Part of the campaign focused on reaching a national audience to inform individuals about STIs and condom use. National TV spots and billboards were introduced with messages about the risks involved in unsafe sex. Display boxes with condoms were sent out to campaign actors and thus made accessible throughout bars, cafés, libraries, stores, drug stores, and educational institutions across Denmark.

At a deeper level of participation, DFPA involved communities by distributing campaign materials through educational and municipal institutions (i.e., youth centers, health care centers, and libraries), companies, and volunteers. At this level, information and condoms were provided and, whenever possible, substantiated by an opportunity to engage in conversations about condom use and sexual health. These conversations were initiated by campaign volunteers recruited from a pool of DFPA volunteers trained to engage their peers. The incentive to volunteer differed: for some, it was an opportunity to attend a festival or a concert, while others enjoyed teaching and discussing sexual health with peers. It was also possible to nominate an exceptionally responsible friend as a campaign volunteer, making it a task of honor. Volunteers were supposed to encourage their peers to participate in condom-themed campus bar nights, condom quizzes, and sex jeopardy arranged at local hang-outs or schools. They were also expected to bring up the topic of sexual health among friends and to make condoms accessible by carrying them around. It was also possible to participate online by competing against peers in an app-based condom game, participating in daily contests on the campaign’s Facebook page, or writing speech bubbles on campaign posters in an app. Together, campaign participants’ norm perceptions were targeted explicitly through peer information sharing in conversations and games.

The campaign strategy was primarily based on the idea that perceptions of normative behaviors and beliefs guide young adults’ decisions to engage in certain behaviors. Considering the influence of social learning on sexual behavior, research has suggested that it is vital to target social norms when promoting condom use (Chang, Citation2014; Huebner et al., Citation2011), and accounting for group behavior generally result in greater positive effects on sustainable health-seeking behavior than individual-level interventions (Miller & Prentice, Citation2016; Wang et al., Citation2011). Therefore, we expect that the latter part of the Danish condom campaign, in which young adults engage in conversations or activities related to the campaign, is especially likely to affect attitudes and behavior regarding condom use.

The present study

We posit that if social engagement reinforces social norms, the intention to use condoms with novel partners should be higher among young adults who interact about sexual health and condom use compared to those who do not engage in such interactions. To test this idea, we analyzed data collected after the Danish condom campaign in 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014. Each annual survey was first analyzed individually, and then, the four surveys were combined in a meta-analysisFootnote1. Since we were interested in the effect of social engagement beyond mere exposure to sexual health information, we distinguished between three exposure groups: people who had not seen or heard about the campaign (1, no exposure group), people who had been exposed to the campaign (2, mere exposure group), and people who had communicated about or had engaged in social activities related to the campaign (3, social engagement group). The outcome measures were condom use intention, perceived risk of contracting an STI, and pro-condom norm.

Participants were also asked whether they perceived their condom use intention, risk perception, and pro-condom norm to have changed due to the campaign. We reasoned that if a participant perceived the campaign to have a considerable impact on their behaviors and beliefs regarding condom use, this was an additional indication that the campaign had been relevant in producing the reported changes.

We hypothesized that people who had seen or heard about the campaign would perceive a higher risk of contracting an STI, have stronger pro-condom norms, and a higher intention to use a condom with a new partner than people who had not been exposed to the campaign at all (H1a), and that people who had been socially engaged in the campaign by conversing about it or taken part in campaign-related activities would score higher on these measures than those who had been merely exposed to the campaign (H1b). Moreover, we expected people who had socially engaged in campaign activities to report more self-perceived changes due to the campaign (H2). An additional analysis testing whether these self-perceived changes due to the campaign mediate the observed condition differences in condom use intention, risk perception, and pro-condom norm is reported in the Appendix.

Method

Participants

A total of 3,031 participants took part in Studies 1-4. Overall, the sample comprised adolescents and young adults ages 15-25 was representative regarding age, gender, geography, and education. For each study, these demographics and descriptive statistics concerning participants’ sexual debut, civil status, student status, are presented in . also presents the type of social engagement, that is, the frequency of participants who discussed vs. participated in campaign activities. The surveys were constructed such that those who reported not having had their sexual debut (sexual intercourse) were omitted from the condom use intention item.

Table 1. Sample demographics, studies 1–4.

Procedure

Advice Denmark Bureau of Communication performed the distribution, administration, and data collection on behalf of the Danish National Board of Health. The sample was drawn from Advice’s panel pool, and participants were recruited to the surveys through email invitations. Invitations to participate in the survey were sent out to the target group of the campaign during the first two weeks of October each year, two weeks after the campaign had ended. In the email invitation, participants were given a link to click if they were interested in participating in a survey about young adults’ attitudes and beliefs about sex. A browser window opened, and they were presented with an introductory text, after which they were asked for their consent to participate in the study. Upon finishing the survey, participants were presented with a screen that thanked them for their time.

Materials and design

The four studies were quasi-experimental, using nonequivalent groups without random group assignment. The surveys were CAWI interviews (Computer Assisted Web Interviews) in the form of self-administered questionnaires. The questionnaires were constructed by experts in youth sexual health employed at DFPA with the objective to assess the impact of the campaign on young adults in Denmark and their norms, risk perceptions, and attitudes toward condom use. The questionnaires consisted of 39-49 open-ended or multiple-choice items. Responses were assessed using Likert-scales or response categories that were either multinomial or ordinal. Multiple-choice questions were forced-choice to avoid high fall-out rates. The response option “I don’t know” was available on most items.

We, as researchers, received the survey data from four years on which we decided which items could be used to measure pro-condom norm, risk perception, and intention to use a condom with a novel partner. While surveys were similar, some questions were changed each year. For each year, we selected items that best represented the construct while keeping consistency high. If an item was included in the analyses for a construct in one year, it was also included in the studies for the subsequent years (unless it was not measured). All decisions regarding the inclusion of items were made before any data was analyzed.

Measures

All measures included the option “I don’t know” on some of the items. We believed this response would add meaning to the analyses; therefore, it was treated as neutral. On items where "I don’t know" was an option (e.g., norm items 1-6 in Study 1), it was recoded with a middle value (e.g., on a 5-point Likert-scale where "I don’t know" was 5, we replaced it with 3), before it was standardized. Item 6 in Studies 3 and 4 were standardized, so we recoded "I don’t know" with the mean (0) for those items. On norm items 1 and 2 in Study 2, the response category "Neither" was given the same neutral meaning as "I don’t know" by allocating the middle value to it.

Pro-condom norm

To assess pro-condom norm, we constructed a scale from four to six items about perceived normative behavior (see for a specification of the items per study). On the measures that consisted of items with varying scales (Studies 2, 3, and 4), the responses were standardized before the items were combined into scales. In Studies 3 and 4, responses on items 1 and 5 were categorized into three response categories coded 1-3 before they were standardized: negative, neutral, and positive. Across studies, Cronbach’s α ranged between .59 and .84 for the scales. Generally, a Cronbach’s α between .6 and .7 is considered an acceptable level of internal consistency, and values above .7 are considered good.

Table 2. Overview of all measures, response scales and coding across studies 1-4.

Risk perception

A single item assessed participants’ risk perception of contracting an STI in Studies 1 and 2. It was decided not to include the two risk perception measures in the analyses of Studies 3 and 4. They were considered to be unreliable measures due to their very low or negative correlation with each other (r2013 = .033, r2014 = .104) as well as the norm (r2013 = −.168, r2014 = −.192) and the condom use intention measure (r2013 = −.093, r2014 = −.114).

Condom use intention

A single item was used to assess participants’ intention to use a condom across all studies. On this item, participants rated the likelihood of using a condom the next time they were to have sex with a new partner on a 5-point Likert scale.

Self-perceived changes due to the campaign

The surveys also included items to assess to what extent the participants themselves believed that the campaign had had an impact on their norm, risk perception, and condom use intention. The participants who reported not having seen or heard about the campaign did not receive these questions. Hence, the self-assessment measures only compared the participants in the mere exposure group to those in the social engagement group.

Pro-condom norm

Self-perceived change in pro-condom norm was tested with a single item in Studies 2 and 3, where "I don’t know" was recoded with the middle value 3. In Study 4, we combined three items to construct a scale with acceptable reliability (α = .702).

Risk perception

Self-perceived change in risk perception was measured by a scale of two items in Studies 1-3. The association between the two items was strong across all three studies (rs > .6). In Study 4, a single item was used.

Condom use intention

A single item assessed self-perceived change in condom use intention across all four studies.

Participants’ social engagement in the campaign

About halfway through the questionnaires, participants were asked about their awareness of and involvement in the campaign. To that end, participants were presented with a campaign picture and asked if they had seen or heard about the campaign during the past month. If the response was no, participants were informed that the picture was from the condom campaign, and then they were asked the same question. If the response remained negatory, they skipped to the next question. If the response was yes, they were asked to indicate whether they had discussed the campaign with anyone, and whether they had participated in one of the following campaign activities: condom-themed campus bar night, condom quiz, or sex jeopardy; competing with peers in a condom game on a phone application; participated in daily contests on the campaign’s Facebook page or filled in a speech bubble on one of the campaign posters in a phone application. Based on these responses, we created three different exposure groups, distinguishing between participants who (1) had not been exposed to the campaign, (2) had been exposed to the campaign, and (3) had been socially engaged in the campaign (interacted about the campaign or participated in campaign-related activities).

Analyses plan

Between-condition differences were tested with one-way ANOVAs unless the assumption for homogeneity of variances was violated according to Levene’s test of equality of variances (p < .05), in which case we performed a Welch’s F-test. To get an idea of the effect sizes, we provide ηp2 along with ANOVA test results and ω2 (proposed by Lakens, Citation2013, as a more conservative measure of effect size) along with Welch’s F-test results. According to Field (Citation2013), both statistics indicate that .01 is a small effect, .06 is medium, and .14 is large. After this initial test, we tested the specific hypotheses with regression analyses using weighted repeated contrasts to correct for the differences in sample size between the groups. Contrast 1 compared the no exposure (weighted code: −1/nno exposure group) to the mere exposure group (weighted code: 1/nmere exposure group) to test the effect of campaign exposure on the outcome variables. Contrast 2 compared the social engagement group (weighted code: 1/nsocial engagement group) to the mere exposure group (weighted code: −1/nmere exposure group) to test the effect of interacting about the campaign or engaging in campaign activities on the outcome variables. This follow-up analysis was done regardless of the ANOVA result because they tested the main hypotheses and provided input for the meta-analyses over the four studies.

Additionally, to estimate the size of the difference between the social engagement group and the mere exposure group on norm, condom use intention, and risk perception across Studies 1-4, we conducted three meta-analyses. We specified a Random-Effects Model using the Metafor package in R.

A second set of three meta-analyses estimated the size of the difference between the social engagement group and the mere exposure group on self-perceived changes on the same variables. Here, effect sizes are reported as Cohen’s d (1992): Cohen’s d = .20 is small and Cohen’s d = .50 is considered a medium effect.

Results

Assumptions

A few outliers were detected across all four datasets, as assessed by inspection of a boxplot for values greater than 1.5 box-lengths from the edge of the box. It was decided to proceed with the analyses without removing them due to the robustness of the ANOVA when sample sizes are adequate (i.e., Sawilowsky & Blair, Citation1992). Q-Q plots revealed that the data of the four datasets was normally or approximately normally distributed. Finally, Levene’s test for equal variances indicated that there was homogeneity of variance on all measures across all studies except for risk perception and condom use intention in Studies 1 and 2 and self-perceived change in risk perception in Study 4.

Study 1

In Study 1, we used data from the 2011 survey. presents an overview of descriptive statistics.

Table 3. Study 1: descriptive statistics per group.

Campaign effects on the main outcome variables

ANOVA results revealed no statistically significant between-group differences on pro-condom norm, risk perception, or condom use intention. Contrast estimates are presented in .

Table 4. Study 1: contrast estimates.

Self-perceived changes due to the campaign

Participants in the social engagement group reported higher self-assessed risk perception changes than those in the mere exposure group, F(1, 338) = 7.93, p = .005, ηp2 = .023. The participants in the mere exposure group did not differ from those in the social engagement group in terms of self-perceived changes in condom use intention.

Study 2

For Study 2, the 2012 data was analyzed. Descriptive statistics are presented in .

Table 5. Study 2: descriptive statistics per group.

Campaign effects on the main outcome variables

The ANOVA revealed a significant difference between the three exposure groups on pro-condom norm, F(2, 997) = 9.35, p < .001, ηp2 = .018. The follow-up analysis with a weighted repeated contrasts indicated that norm scores were significantly higher in the mere exposure group than in the no exposure group. People in the social engagement group scored significantly higher on the norm items than did those in the mere exposure group.

No between-group differences were found in risk perception. There was a statistically significant difference in condom use intention between the exposure groups, Welch’s F(2, 433.010) = 6.75, p = .001, ω2 = .010. The contrast analysis revealed that people who had been merely exposed to the campaign reported significantly higher condom use intentions than those who had not been exposed to the campaign. Moreover, people who were socially engaged in the campaign reported higher condom use intentions than those who were merely exposed to campaign information. presents all estimates of the weighted repeated contrast analyses in Study 2.

Table 6. Study 2: contrast estimates.

Self-perceived changes due to the campaign

People in the social engagement group reported significantly greater pro-condom norm changes due to the campaign than those in the mere exposure group, F(1, 670) = 17.89, p = .003, ηp2 = .013. In the social engagement condition, people reported a significantly greater change in risk perception due to the campaign than those in the mere exposure group, F(1, 670) = 10.50, p = .001, ηp2 = .015. Likewise, people who had been socially engaged in the campaign reported statistically significantly higher condom use intentions due to the campaign than those who had been merely exposed to the campaign F(1, 670) = 11.08, p < .001, ηp2 = .016.

Study 3

The 2013 data was analyzed in Study 3. Descriptive statistics are presented in .

Table 7. Study 3: descriptive statistics per group.

Campaign effects on the main outcome variables

Pro-condom norm significantly differed between exposure groups, F(2, 1077) = 3.52, p = .030, ηp2 = .006. The contrasts analysis revealed that the people in the social engagement group reported statistically significantly higher pro-condom norms than those in the mere exposure group. No statistically significant group difference in condom use intention was found, see for contrast estimates.

Table 8. Study 3: contrast estimates.

Self-perceived changes due to the campaign

The difference in self-assessed change in pro-condom norm was statistically significantly higher among those who had socially engaged in the campaign than those who were merely exposed to the campaign, F(1, 801) = 15.65, p <.001, ηp2 = .019. Similarly, people in the social engagement condition scored higher on self-assessed change in risk perception than did those in the mere exposure group, F(1, 799) = 16.65, p <.001, ηp2 = .020. Participants in the social engagement group reported a greater change in condom use intention than in the mere exposure group, F(1, 716) = 7.1, p = .008, ηp2 = .010.

Study 4

Finally, Study 4 was based on data from the 2014 campaign. Descriptive statistics for all variables are found in .

Table 9. Study 4: descriptive statistics per group.

Campaign effects on the main outcome variables

Participants in the different groups did not differ in pro-condom norm or condom use intention. Results from the weighted repeated contrast analyses are presented in .

Table 10. Study 4: contrast estimates.

Self-perceived changes due to the campaign

Compared to the mere exposure condition, participants in the social engagement condition reported a greater self-perceived change in pro-condom norm, F(1, 355) = 3.7, p <.001, ηp2 = .077, in risk perception, Welch’s F(1, 234.45) = 28.27, p < .001, ω2 = .068, and in condom use intention, F(1, 288) = 28.3, p < .001, ηp2 = .089.

Meta-analysis

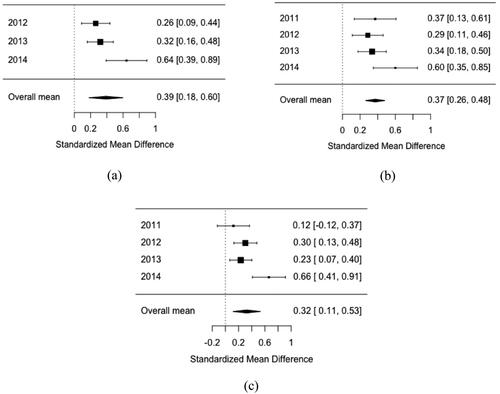

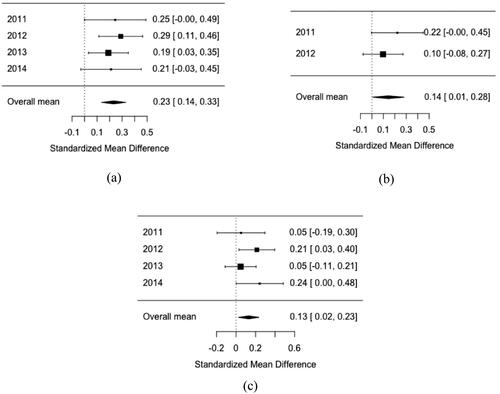

The results of the meta-analyses estimating the size of the difference between the social engagement group and the mere exposure group on norm, risk perception, and condom use intention are displayed in . For all three variables, the estimated effect sizes were small (Cohen, Citation1992) but reliably different from 0 across studies, pro-condom norm: Cohen’s d = 0.23, SE = .04, Z = 4.69, p < .001, 95% CI [.14; .33], condom use intention: Cohen’s d = 0.13, SE = .05, Z = 2.42, p = .016, 95% CI [.02; .23], perceived risk (data only for 2011 and 2012): Cohen’s d = 0.14, SE = .07, Z = 2.04, p = .041, 95% CI [.01; .28].

Figure 1. Meta-analyses 1. Panel A: Effects of social engagement on pro-condom norms. Panel B: Effects of social engagement on perceived risk. Panel C: Effects of social engagement on condom use intention.

The second set of meta-analyses (see ) revealed that the size of the difference between the social engagement group and the mere exposure group on participants’ self-perceived changes in norm, risk perception, and condom use intention, and were small to medium in size (Cohen, Citation1992) and reliably different from 0 across studies, self-perceived change in norm (no data for 2011): Cohen’s d = 0.39, SE = .11, Z = 3.63, p < .001, 95% CI [.17; .60], self-perceived change in condom use intention: Cohen’s d = 0.32, SE = .11, Z = 3.01, p = .003, 95% CI [.11; .53], self-perceived change in risk perception: Cohen’s d = 0.37, SE = .06, Z = 6.62, p < .001, 95% CI [.26; .48].

Discussion

This research aimed to understand the impact of social elements within campaigns for changing norms, risk perceptions, and behavioral intentions regarding condom use. We tested this in a meta-analysis of four large-scale quasi-experimental field studies in the context of a sexual health campaign in Denmark. Our hypotheses are partially supported by individual study results: Hypothesis 1a (H1a) was partially supported in Study 2, where results showed that mere exposure to the campaign increased pro-condom norms and condom use intentions compared to not being exposed to the campaign. We found partial support for hypothesis 1b (H1b) in Study 2 and 3; socially engaged participants reported stronger pro-condom norms than participants in the mere exposure group. In Study 2, this was also true for condom use intentions. Although findings for individual studies reported in this paper differ in strength (but not in direction), the converging evidence across studies, as established by the meta-analysis, supports H1b: young adults who had conversed about campaign-related topics or taken part in campaign activities perceived stronger pro-condom norms than those who had merely been exposed to campaign information. Beyond its link to social norms, social engagement in the campaign was also associated with higher intention to use a condom with a novel partner and perception of the risks involved in having intercourse without a condom. The results of the meta-analyses indicated small but reliable effect sizes for pro-condom norm, risk perception, and condom use intention across studies. In support of Hypothesis 2 (H2), participants also recognized this impact; those who socially engaged with the campaign reported that their norm, risk perception, and condom use intention had changed more due to the campaign than those who had merely observed the campaign information.

We want to point out that not all individual analyses yielded statistically significant group differences. With Study 1 presenting the weakest support for the hypotheses, in which group differences for none of the three central outcome variables were statistically significant. It is important here to point to the sample size of this study, which was small and unevenly distributed across experimental groups, and made the analyses underpowered. The same problem may underly the lack of statistically significant difference in norm in Study 4. It is important to note that the effects in all studies go in the hypothesized direction, and that the meta-analyses are more informative in this sense because they are robust to these differences in power across studies.

The support for a group difference in condom use intention was only statistically significant in Study 2. Although it is common practice to assess behavioral intention by single items (Webb & Sheeran, Citation2006), this can be problematic in several ways (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Citation2009), which are discussed further down in the limitations section. Note that here again, differences in all four studies are in the hypothesized direction, and the meta-analysis across studies points to a significantly higher intention to use a condom with a novel partner among those who socially engaged with the campaign compared to those who had merely been exposed.

Taken together, the results of the meta-analyses across studies indicate (a) an increment in pro-condom norms, intentions to use a condom, and perceptions of risks connected to condomless sex for participants who had been socially engaged by interacting about the campaign or taking part in campaign activities compared to those who had been merely exposed to the campaign information, and (b) that participants themselves attribute these changes to their engagement with the campaign. This is in line with previous research suggesting that interaction has an influential effect on social norm formation (Kashima et al., Citation2007; Koudenburg et al., Citation2015) and that social observation is the key to learning about behavior from others (Bandura, Citation1977; Cialdini, Citation2001).

Theoretical and practical implications

The findings of this paper suggest that socially engaging with the campaign increases intention to use a condom with a novel partner. According to the theory of reasoned action (Fishbein, Citation1980; Fishbein & Ajzen, Citation1975), intention is considered the most adjacent antecedent to behavior. Despite studies identifying intention as an unreliable predictor of condom use among young people (Carvalho & Alvarez, Citation2015; Sutton, Citation1998), other studies have established a link between pro-condom norms, intended condom use, and actual condom use (Jellema et al., Citation2013; van Empelen & Kok, Citation2008), indicating that under favorable conditions, intention is a primary criterion for behavior. Most importantly, social norms are a key factor limiting or boosting the intention to perform a behavior (Rader et al., Citation2021). In our study, discussing condoms was associated with higher intention to use a condom with a new partner and a more positive pro-condom norm. The finding that conversations about condoms or engagement in condom-related activities can foster a combination of increased condom use intentions and more positive norms yields confidence that actual condom use is likely to increase. In addition to social norms, some studies highlight that the link between the intention to use a condom and actual condom use is mediated by preparatory behavior, such as discussing safe sex and acquiring condoms (Bryan et al., Citation2002) and volitional self-efficacy (Carvalho & Alvarez, Citation2015; Teng & Mak, Citation2011). We therefore advise future research on young adult’s condom use to identify and study causal links between intended condom use, preparatory behaviors and attitudes, and actual condom use. To this end, it might be helpful to consult reviews on health behavior research, such as Webb and Sheeran (Citation2006) and Sheeran et al. (Citation2016).

Supported by a growing body of research suggesting that dyadic communication is essential to condom use (i.e., Figueroa et al., Citation2014; Noar et al., Citation2006; Reddy et al., Citation2000; van de Bongardt et al., Citation2017), our findings highlight that communication within a group of several peers or a community may add to the effectiveness of condom use interventions (see Chin et al., Citation2012 for a systematic review of group-based sexual risk reduction interventions). Moreover, the present research demonstrates a link between shared activities and changes in beliefs, norms, and behavior regarding condom use. For example, in the current studies, young adults were not always engaging in active discussions about the topic of condom use but sometimes simply playing an online condom game against peers. While condom use is not deliberately negotiated in these activities, the issue appears to surface from the taboo sphere and become a more socially acceptable and connective (i.e., normative) behavior. This extends previous research suggesting that social acceptance can often occur implicitly, for instance, when an expressed opinion is not objected to Koudenburg et al. (Citation2020). Indeed, observing others’ behavior leads to inferences about social norms and, further, applying these perceived norms to the general public (Chia & Lee, Citation2008; Koudenburg et al., Citation2020; Meeussen & Koudenburg, Citation2022).

Beyond the demonstrated link between peer-to-peer interaction and condom-related norms, beliefs, and behavior, a significant body of research suggests that parent-child conversations also positively influence sexual health norms (Wang et al., Citation2019) and reduce risky sexual behavior and attitudes (Willoughby & Guilamo-Ramos, Citation2022; Wright et al., Citation2020). Albeit, parental monitoring of youth sexual behavior may bring along adverse effects such as resistance to warnings, while family ratification of promiscuity may foster risky sexual behavior (Coley et al., Citation2013). We argue that when designing interventions that facilitate peer-to-peer communication, a similar impact can be reached while thwarting problems that accompany parental communication.

Because of the pluriformity of social engagement studied in this paper we cannot say with certainty which element of the interaction was effective in promoting change. One might suggest that people who engaged more with the campaign elaborated more on its content (consistent with the elaboration likelihood model, by Petty & Cacioppo, Citation1986). However, we have reason to believe that especially the social processes motivated shifting perceptions and behavioral intentions, for two reasons. First, while we can say with certainty that people engaged in more social interaction, we cannot be sure – only theorize that participants elaborated more or less in the different conditions. Second, in our meta-analysis, we found the largest effect on social norms, which underlined that a shifting normative process was most central in producing the observed change and that (individual) cognitive elaboration on the risks involved may have resulted from this.

The current research has direct implications for future norm-based condom campaigns, proposing a two-fold approach to foster a change in the sexual health behavior of young adults: beliefs are targeted by the availability of appropriate information, and perceptions of peers’ beliefs are addressed by enabling social information sharing. This approach allows young people to learn about the pitfalls of unsafe sex while confirming the commonality of safe-sex practices, thereby reducing the social stigma of sexual preventative behavior (van Empelen & Kok, Citation2008) and averting false norm perceptions (Miller & Prentice, Citation2016).

Lastly, referencing several studies about adolescents, it is necessary to address the interchangeable use of the terms adolescence and young adulthood (which is broadly defined in the literature; Society for Adolescent Health & Medicine, 2017), as the role of social norms may change drastically between ages 10 to 30. Steinberg and Monahan (Citation2007) found that resistance to peer influence was curvilinearly related to age, peaking between ages 14 and 18, suggesting that social needs develop and shift focus as adolescence and young adulthood emerge. For example, most young people want to differentiate themselves from their family in early adolescence and proximate their peers in beliefs and behavior, but the onset of seeking a unique identity requires them to distance themselves from peers in later adolescence. Future studies might consider that markedly different motivational forces may be at play regarding social influence at different developmental stages during early, mid, and late adolescence and young adulthood.

Limitations

The large-scale field study strengthens our confidence in the ecological validity of the reported effects. However, as with all quasi-experimental designs, causal claims need to be made with caution: Participants with a stronger pro-condom norm may dispose of a tendency to actively seek engagement in debates and activities related to the topic. While we will never be fully able to refute such claims with cross-sectional data, our findings suggest that this may not explain our results. Indeed, participants were asked to report how much their perceptions of risks, social norms, and condom use intentions had changed during the campaign. Importantly, these findings revealed that participants who had socially engaged in campaign-related activities reported that their perceptions of norms and risks and their intentions had changed more than those who were merely exposed to the campaign information. These higher self-perceived changes were reported in all four studies, and the meta-analyses revealed a consistent and slightly larger effect on all three self-perceived change variables. Moreover, additional analyses reported in the Appendix revealed that differences in outcomes between those who socially engaged with the campaign and those who were merely exposed to campaign information, were explained by participants’ attributions to the campaign: between-group differences in condom use intentions and norm perceptions were mediated by their perceived increases in these variables due to the campaign.

Not having constructed the surveys ourselves, we ran into a few methodological concerns. First, in the current analysis, we treated the answer category "I do not know" as a neutral category to avoid losing meaningful data. The reliability of the scales may have suffered from these decisions because these open-answer categories may reflect different motivations. The use of validated Likert-scales could have improved the reliability. Second, we used single-item measures for some constructs. Single-item measures have been criticized because their reliability remains unknown which makes them more vulnerable to measurement error. Importantly, these concerns are less prevalent when constructs are unidimensional, clearly-defined and narrow in scope (Fuchs & Diamantopoulos, Citation2009; Postmes et al., Citation2013), and in such cases, single-item measures allow for unambiguous and efficient testing (Allen et al., Citation2022). In the present studies, we used single items only for clear behavioral intentions and risk perceptions. The more central construct of norms, which arguably is broader because it encompasses the behavior of friends (descriptive norms), but also what people consider normal, or acceptable social practice (prescriptive norms), was measured with four to six items in each study. Moreover, as an alternative way to assess the reliability of the effects, a meta-analysis across studies was performed.

Third, items assessing condom use intention were phrased in terms of intended condom use with a new partner. Evidence suggests that the likelihood of using condoms is higher with a new partner than with a steady partner (Staras et al., Citation2013). Moreover, STI history, age, marriage status, and gender are all demographics that may motivate people to use condoms with casual partners, more so than with steady partners (Chatterjee et al., Citation2006). Several other studies point toward different motives for using a condom with casual partners compared to new partners (Fortenberry et al., Citation2002; van Empelen et al., Citation2001; van Empelen & Kok, Citation2008). It was not possible to distinguish condom use with a casual partner from condom use with a steady partner in the current study. Still, we believe it would be insightful for future studies to make this distinction.

Finally, another limitation is the messages communicated to the public through the campaign. Although deciding upon these messages was beyond our control, we want to discuss them to provide input for future sexual health prevention efforts. The main message of the 2011-2014 campaigns was “Only with a condom are you alone in bed.” This statement implies that by not using a condom, you bring the "presence" of your partner’s previous sexual partners to bed by risking the contraction of an STI that your partner has contracted from a former sexual partner. The message on another 2011 campaign poster with a girl posing in underwear read, "Do I look like I have an STI?". (This image can be found in the open repository of this research project https://osf.io/5kr98/). These messages may be problematic because they make use of scare tactics that focus on the health hazards of not using a condom, which is proven to be an ineffective strategy (Scholly et al., 2005). Second, they may inaccurately convey information about normative youth behavior. That is, young people may mistakenly believe that the messages reflect peer behavior, leading them to overestimate condomless sex and discount the negative consequences thereof (Chia & Lee, Citation2008). A qualitative study of condom use among Danish youth confirmed that contracting an STI was perceived to be expected and relatively harmless: “a logical consequence of having sex” or “something you just take a pill to get rid of” (Hanghøj, Citation2017).

Conclusion

Based on a large national dataset, the knowledge gained from the study provides a crucial insight that reduces some of the adverse side effects of campaigns addressing social norms. Indeed, as discussed in the introduction of this paper, such campaigns may sometimes backfire if the portrayed “bad” behavior is mistaken as the behavior of the majority, leading young adults to overestimate the risky sexual behavior of their peers and to act accordingly. The current research findings suggest that such adverse side effects can be lifted when combining campaign information with the possibility of socially validating information with relevant peers and, as indicated by other studies, parents and other supportive adults such as teachers (Tseng et al., Citation2020; van Empelen & Kok, Citation2008; Wang et al., 2019; Willoughby & Guilamo-Ramos, Citation2022). Therefore, this paper’s take-home message is that young adults need sexual health promotion programs with interactional elements that permeate their social environments (i.e., at school, at home, and among friends). Moreover, the messages conveyed by such programs should remain factual to serve as foundations for equitable peer-to-peer discussions, minimizing the social transmission of inaccurate norms. Nonetheless, including playful elements in sexual health campaigns may be beneficial as norms sometimes form implicitly. Honest conversations about sexual health thrive in non-judgmental and inclusive settings and ought to be facilitated in collaboration with healthcare professionals, teachers, and parents, but most importantly, led by young adults themselves.

Declaration of interest

The study was performed on existing data collected on behalf of The Danish Health Authority. The organization had no influence on the research question studied in this paper, nor on the analyses, write-up, or decision to publish. The authors therefore declare no conflict of interest.

Notes

1 Because of differences in measurement per year, we could not analyse these as a single study.

References

- Abel, G., & Fitzgerald, L. (2006). When you come to it you feel like a dork asking a guy to put a condom on’: Is sex education addressing young people’s understandings of risk? Sex Education, 6(2), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681810600578750

- Allen, M. S., Iliescu, D., & Greiff, S. (2022). Single item measures in psychological science. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000699

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191–215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

- Braeken, D., & Cardinal, M. (2008). Comprehensive sexuality education as a means of promoting sexual health. International Journal of Sexual Health, 20(1-2), 50–62. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317610802157051

- Bryan, A., Fisher, J. D., & Fisher, W. A. (2002). Tests of the mediational role of preparatory safer sexual behavior in the context of the theory of planned behavior. Health Psychology, 21(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.21.1.71

- Carvalho, T., & Alvarez, M. J. (2015). Preparing for male condom use: The importance of volitional predictors. International Journal of Sexual Health, 27(3), 303–315. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2014.982264

- Chang, L. (2014). College students search for sexual health information from their best friends: An application of the theory of motivated information management. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 17(3), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12063

- Charania, M. R., Crepaz, N., Guenther-Gray, C., Henny, K., Liau, A., Willis, L. A., & Lyles, C. M. (2010). Efficacy of structural-level condom distribution interventions: A meta-analysis of U.S. and international studies, 1998–2007. AIDS and Behavior, 15(7), 1283–1297. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-010-9812-y

- Chatterjee, N., Hosain, G. M., & Williams, S. (2006). Condom use with steady and casual partners in inner-city African-American communities. Sexually Transmitted Infections, 82(3), 238–242. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2005.018259

- Cherie, A., & Berhane, Y. (2012). Peer pressure is the prime driver of risky sexual behaviors among school adolescents in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. World Journal of AIDS, 02(03), 159–164. https://doi.org/10.4236/wja.2012.23021

- Chia, S. C. (2006). How peers mediate media influence on adolescents’ sexual attitudes and sexual behavior. Journal of Communication, 56(3), 585–606. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2006.00302.x

- Chia, S. C., & Lee, W. (2008). Pluralistic ignorance about sex: The direct and indirect effects of media consumption on college students’ misperception of sex-related peer norms. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 20(1), 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edn005

- Chin, H. B., Sipe, T. A., Elder, R., Mercer, S. L., Chattopadhyay, S. K., Jacob, V., Wethington, H. R., Kirby, D., Elliston, D. B., Griffith, M., Chuke, S. O., Briss, S. C., Ericksen, I., Galbraith, J. S., Herbst, J. H., Johnson, R. L., Kraft, J. M., Noar, S. M., Romero, L. M., … Santelli, J. (2012). The effectiveness of group-based comprehensive risk-reduction and abstinence education interventions to prevent or reduce the risk of adolescent pregnancy, human immunodeficiency virus, and sexually transmitted infections: two systematic reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 42(3), 272–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.11.006

- Cialdini, R. B. (2001). The science of persuasion. Scientific American, 284(2), 76–81. https://doi.org/10.1038/scientificamerican0201-76

- Cialdini, R. B., Reno, R. R., & Kallgren, C. A. (1990). A focus theory of normative conduct: Recycling the concept of norms to reduce littering in public places. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(6), 1015–1026. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.58.6.1015

- Cialdini, R. B., & Trost, M. R. (1998). Social influence: Social norms, conformity, and compliance. In D. T. Gilbert, S. T. Fiske, & G. Lindzey (Eds.), The handbook of social psychology (pp. 151–192). McGraw-Hill.

- Clark, A. E., & Kashima, Y. (2007). Stereotypes help people connect with others in the community: A situated functional analysis of the stereotype consistency bias in communication. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93(6), 1028–1039. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.93.6.1028

- Clark, H. H., & Brennan, S. E. (1991). Grounding in communication. In L. B. Resnick, J. Levine & S. D. Teasley (Eds.), Perspectives on socially shared cognition (pp. 127–149). American Psychological Association.

- Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

- Coley, R. L., Lombardi, C. M., Lynch, A. D., Mahalik, J. R., & Sims, J. (2013). Sexual partner accumulation from adolescence through early adulthood: The role of family, peer, and school social norms. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 53(1), 91–97.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.005

- Degner, J., & Dalege, J. (2013). The apple does not fall far from the tree, or does it? A meta-analysis of parent–child similarity in intergroup attitudes. Psychological Bulletin, 139(6), 1270–1304. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031436

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics with IBM SPSS statistics. Sage.

- Fiellin, L. E., Hieftje, K. D., Pendergrass, T. M., Kyriakides, T. C., Duncan, L. R., Dziura, J. D., Sawyer, B. G., Mayes, L., Crusto, C. A., Forsyth, B. W. C., & Fiellin, D. A. (2017). Video game intervention for sexual risk reduction in minority adolescents: Randomized controlled trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(9), e314. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.8148

- Figueroa, M. E., Kincaid, D. L., & Hurley, E. A. (2014). The effect of a joint communication campaign on multiple sex partners in Mozambique: The role of psychosocial/ideational factors. AIDS Care, 26 Suppl 1(sup1), S50–S55. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540121.2014.907386

- Fishbein, M. (1980). A theory of reasoned action: Some applications and implications. In H. Howe & M. Page (Eds.), Nebraska symposium on motivation (Vol. 27, pp. 65–116). University of Nebraska Press.

- Fishbein, M., & Ajzen, I. (1975). Belief, attitude, intention and behavior: An introduction to theory and research. Addison Wesley.

- Fortenberry, J. D., Tu, W., Harezlak, J., Katz, B. P., & Orr, D. P. (2002). Condom use as a function of time in new and established adolescent sexual relationships. American Journal of Public Health, 92(2), 211–213. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.2.211

- Fuchs, C., & Diamantopoulos, A. (2009). Using single-item measures for construct measurement in management research: Conceptual Issues and Application Guidelines. Betriebswirtschaft, 69(2), 195–210.

- Gragnano, A., & Miglioretti, M. (2017). Is a web video effective in increasing intention to use condoms? A test based on the Health Action Process Approach. Applied Psychology Bulletin, 279(65), 2–14.

- Hanghøj, S. (2017). Kun med Kondom. En kvalitativ undersøgelse af 18-23-åriges kondombrug [Only with a condom. A qualitative study of 18–23-year-olds use of condoms]. https://www.klinisk.aau.dk/digitalAssets/450/450017_rapport-sst_sh.pdf

- Henry, D. B., Kobus, K., & Schoeny, M. E. (2011). Accuracy and bias in adolescents’ perceptions of friends’ substance use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: journal of the Society of Psychologists in Addictive Behaviors, 25(1), 80–89. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021874

- Hoffman, C. M., Fritz, L., Matlakala, N., Mbambazela, N., Railton, J. P., McIntyre, J. A., Dubbink, J. H., & Peters, R. P. H. (2019). Community‐based strategies to identify the unmet need for care of individuals with sexually transmitted infection‐associated symptoms in rural South Africa. Tropical Medicine & International Health: TM & IH, 24(8), 987–993. https://doi.org/10.1111/tmi.13274

- Huebner, D. M., Neilands, T. B., Rebchook, G. M., & Kegeles, S. M. (2011). Sorting through chickens and eggs: A longitudinal examination of the associations between attitudes, norms, and sexual risk behavior. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 30(1), 110–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021973

- Jellema, I. J., Abraham, C., Schaalma, H. P., Gebhardt, W. A., & van Empelen, P. (2013). Predicting having condoms available among adolescents: The role of personal norm and enjoyment. British Journal of Health Psychology, 18(2), 453–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8287.2012.02088.x

- Kashima, Y. (2008). A social psychology of cultural dynamics: Examining how cultures are formed, maintained, and transformed. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 107–120. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2007.00063.x

- Kashima, Y. (2014). Meaning, grounding, and the construction of social reality. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 17(2), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12051

- Kashima, Y., Klein, O., & Clark, A. E. (2007). Grounding: Sharing information in social interaction. In K. Fiedler (Ed.), Social communication (pp. 27–77). Psychology Press.

- Kashima, Y., Wilson, S., Lusher, D., Pearson, L. J., & Pearson, C. (2013). The acquisition of perceived descriptive norms as social category learning in social networks. Social Networks, 35(4), 711–719. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socnet.2013.06.002

- Koudenburg, N., Kannegieter, A., Postmes, T., & Kashima, Y. (2020). The subtle spreading of sexist norms. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 24(8), 1467–1485. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430220961838

- Koudenburg, N., Postmes, T., & Gordijn, E. H. (2017). Beyond the content of conversation: The role of conversational form in the emergence and regulation of social structure. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 21(1), 50–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315626022

- Koudenburg, N., Postmes, T., Gordijn, E. H., & van Mourik Broekman, A. (2015). Uniform and complementary social interaction: Distinct pathways to solidarity. PloS One, 10(6), e0129061. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129061

- Lakens, D. (2013). Calculating and reporting effect sizes to facilitate cumulative science: A practical primer for t-tests and ANOVAs. Frontiers in Psychology, 4, 863. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00863

- Lambert, T. A., Kahn, A. S., & Apple, K. J. (2003). Pluralistic ignorance and hooking up. Journal of Sex Research, 40(2), 129–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490309552174

- Lewis, M. A., Litt, D. M., Cronce, J. M., Blayney, J. A., & Gilmore, A. K. (2014). Underestimating protection and overestimating risk: examining descriptive normative perceptions and their association with drinking and sexual behaviors. Journal of Sex Research, 51(1), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.710664

- Lynch, A. D., Coley, R. L., Sims, J., Lombardi, C. M., & Mahalik, J. R. (2015). Direct and interactive effects of parent, friend and schoolmate drinking on alcohol use trajectories. Psychology & Health, 30(10), 1183–1205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2015.1040017

- Macleod, C. I., & Jearey-Graham, N. (2015). "Peer pressure" and “peer normalization”: Discursive resources that justify gendered youth sexualities. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 13(3), 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-015-0207-8

- Meeussen, L., & Koudenburg, N. (2022). A compliment’s cost: How positive responses to non‐traditional choices may paradoxically reinforce traditional gender norms. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 61(4), 1183–1201. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12532

- Miller, D. T., & Prentice, D. A. (2016). Changing norms to change behavior. Annual Review of Psychology, 67(1), 339–361. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015013

- Noar, S. M., Carlyle, K., & Cole, C. (2006). Why communication is crucial: Meta-analysis of the relationship between safer sexual communication and condom use. Journal of Health Communication, 11(4), 365–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730600671862

- Peҫi, B. (2017). Peer influence and adolescent sexual behavior trajectories: Links to sexual initiation. European Journal of Multidisciplinary Studies, 4(3), 96–105. https://doi.org/10.26417/ejms.v4i3.p96-105

- Perkins, H. W. (2003). The emergence and evolution of the social norms approach to substance abuse prevention. In H. W. Perkins (Ed.), The social norms approach to preventing school and college age substance abuse: A handbook for educators, counselors, and clinicians (pp. 3–17). Jossey-Bass/Wiley.

- Petty, R., & Cacioppo, J. (1986). The elaboration likelihood model of persuasion - The really long article. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 19, 1–24.

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Jans, L. (2013). A single-item measure of social identification: Reliability, validity, and utility. The British Journal of Social Psychology, 52(4), 597–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjso.12006

- Postmes, T., Haslam, S. A., & Swaab, R. I. (2005). Social influence in small groups: An interactive model of social identity formation. European Review of Social Psychology, 16(1), 1–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463280440000062

- Postmes, T., Spears, R., & Lea, M. (2000). The formation of group norms in computer-mediated communication. Human Communication Research, 26(3), 341–371. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2000.tb00761.x

- Prentice, D. A., & Miller, D. T. (1993). Pluralistic ignorance and alcohol use on campus: Some consequences of misperceiving the social norm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.64.2.243

- Rader, K., Hovick, S. R., & Bigsby, E. (2021). "Are you clean?" Encouraging STI communication in casual encounters through narrative messages in romance novels. Communication Studies, 72(3), 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2021.1899006

- Reddy, P., Meyer-Weitz, A., Borne, B. V. D., & Kok, G. (2000). Determinants of condom-use behaviour among STD clinic attenders in South Africa. International Journal of STD & AIDS, 11(8), 521–530. https://doi.org/10.1258/0956462001916434

- Sales, J. M., Lang, D. L., DiClemente, R. J., Latham, T. P., Wingood, G. M., Hardin, J. W., & Rose, E. S. (2012). The mediating role of partner communication frequency on condom use among African American adolescent females participating in an HIV prevention intervention. Health Psychology: official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 31(1), 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025073

- Sawilowsky, S., & Blair, R. C. (1992). A more realistic look at the robustness and Type II error properties of the t-test to departures from population normality. Psychological Bulletin, 111(2), 352–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.111.2.352

- Scholly, K., Katz, A. R., Gascoigne, J., & Holck, P. S. (2005). Using social norms theory to explain perceptions and sexual health behaviors of undergraduate college students: An exploratory study. Journal of American College Health, 53(4), 159–166. https://doi.org/10.3200/JACH.53.4.159-166

- Sheeran, P., Maki, A., Montanaro, E., Avishai-Yitshak, A., Bryan, A., Klein, W. M. P., Miles, E., & Rothman, A. J. (2016). The impact of changing attitudes, norms, and self-efficacy on health-related intentions and behavior: A meta-analysis. Health Psychology: Official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(11), 1178–1188. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000387

- Simeone, S., & Jeglic, E. L. (2019). Is locker room talk really just talk? An analysis of normative sexual talk and behavior. Deviant Behavior, 40(12), 1587–1595. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1597319

- Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. (2017). Young adult health and well-being: A position statement of the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health, 60(6), 758–759. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.03.021

- Spears, R. (2021). Social influence and group identity. Annual Review of Psychology, 72(1), 367–390. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-070620-111818

- Staras, S. A., Livingston, M. D., Maldonado-Molina, M. M., & Komro, K. A. (2013). The influence of sexual partner on condom use among urban adolescents. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 53(6), 742–748. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.06.020

- Steinberg, L., & Monahan, K. C. (2007). Age differences in resistance to peer influence. Developmental Psychology, 43(6), 1531–1543. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.6.1531

- Sutton, S. (1998). Predicting and explaining intentions and behavior: How well are we doing? Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 28(15), 1317–1338. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1998.tb01679.x

- Swaab, R., Postmes, T., van Beest, I., & Spears, R. (2007). Shared cognition as a product of, and precursor to, shared identity in negotiations. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(2), 187–199. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167206294788

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. (1979). An integrative theory of inter-group conflict. In W. S., Austin (Ed.), The social psychology of inter-group relations. Brooks/Cole.

- Teng, Y., & Mak, W. W. (2011). The role of planning and self-efficacy in condom-use among men who have sex with men: An application of the Health Action Process Approach model. Health Psychology: official Journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 30(1), 119–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022023

- The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, (2022). Youth STIs: An epidemic fueled by shame. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 6(6), 353. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(22)00128-6

- Trinh, S. L., Ward, L. M., Day, K., Thomas, K., & Levin, D. (2014). Contributions of divergent peer and parent sexual messages to Asian American college students’ sexual behaviors. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 208–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.721099

- Tseng, Y. ‐H., Cheng, C. ‐P., Kuo, S. ‐H., Hou, W. ‐L., Chan, T. ‐F., & Chou, F. ‐H. (2020). Safe sexual behaviors intention among female youth: The construction on extended theory of planned behavior. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(3), 814–823. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14277

- van de Bongardt, D., Reitz, E., Overbeek, G., Boislard, M. A., Burk, B., & Deković, M. (2017). Observed normativity and deviance in friendship dyads’ conversations about sex and the relations with youths’ perceived sexual peer norms. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(6), 1793–1806. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0763-x

- van de Bongardt, D., Reitz, E., Sandfort, T., & Deković, M. (2015). A meta-analysis of the relations between three types of peer norms and adolescent sexual behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Review: An Official Journal of the Society for Personality and Social Psychology, Inc, 19(3), 203–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314544223

- van Empelen, P., & Kok, G. (2008). Action-specific cognitions of planned and preparatory behaviors of condom use among Dutch adolescents. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(4), 626–640. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9286-9

- van Empelen, P., Schaalma, H. P., Kok, G., & Jansen, M. W. J. (2001). Predicting condom use with casual and steady sex partners among drug users. Health Education Research, 16(3), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/16.3.293

- Wang, K., Brown, K., Shen, S. Y., & Tucker, J. (2011). Social network-based interventions to promote condom use: A systematic review. AIDS and Behavior, 15(7), 1298–1308. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0020-1

- Wang, Y., Chen, M., & Lee, J. H. (2019). Adolescents’ social norms across family, peer, and school settings: Linking social norm profiles to adolescent risky health behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 48(5), 935–948. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-00984-6

- Webb, T. L., & Sheeran, P. (2006). Does changing behavioral intentions engender behavior change? A meta-analysis of the experimental evidence. Psychological Bulletin, 132(2), 249–268. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.2.249

- Willoughby, J. F., & Guilamo-Ramos, V. (2022). Designing a parent-based national health communication campaign to support adolescent sexual health. The Journal of Adolescent Health: official Publication of the Society for Adolescent Medicine, 70(1), 12–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2021.09.023

- Wright, P. J., Tokunaga, R. S., & Kraus, A. (2016). Consumption of pornography, perceived peer norms, and condomless sex. Health Communication, 31(8), 954–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2015.1022936

- Wright, P. J., Herbenick, D., & Paul, B. (2020). Adolescent condom use, parent-adolescent sexual health communication, and pornography: Findings from a U.S. probability sample. Health Communication, 35(13), 1576–1582. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2019.1652392

- World Health Organization. (2024). Sexually transmitted infections (STIs). https://www.who.int/news-room/factsheets/detail/sexually-transmitted-infections-(stis)#:∼:text=More%20than%201%20million%20sexually,%2C%20gonorrhoea%2C%20syphilis%20and%20trichomoniasisW