ABSTRACT

The objective of this study was to define the types of digital tools currently used and desired by food pantries for pantry management. A nationwide online survey of U.S. food pantries was conducted by searching the foodpantries.org database. Surveys were sent via e-mail and completed using Google Forms. The most desired food pantry app/software features included staff and volunteer scheduling (49.2%); inventory management (42.1%); communicating with volunteers and staff (35.7%); client registration at the pantry (35.4%); and tracking pantry statistics (33.7%). Overall, food pantry staff and volunteers desire access to digital tools related to both staff/volunteer and client management.

Introduction

Food insecurity, defined as a lack of consistent access to healthy, culturally-appropriate food for leading an active, healthy life,Citation1 affects 35 million people in the United States (U.S.) annually.Citation2 During the Coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, food insecurity increased in the U.S., compounded by critical limitations and unmet needs at food banks and pantries.Citation3 These food assistance organizations play a crucial role in addressing food insecurity, serving more than 46 million individuals in the U.S. annually, prior to the COVID-19 spread.Citation4 In addition to providing access to food, these organizations influence the diet quality of the clients they serve. Therefore, they have the potential to act as change agents for improving client food consumption through nutrition education, and the empowerment that comes with a client choice model (where clients can choose their own foods at a pantry based on their needs, preferences, and cultural appropriateness).Citation5–7

Food banks and the food pantries they serve face many challenges in meeting the demand for food. Previous work has demonstrated that clients value being able to choose their own food in food pantry settings, having a variety of food options consistently available (especially staple food items), and having knowledgeable staff/volunteers available on-site for assistance.Citation6 Yet, many food pantries tend to be understaffed with older adult volunteers with limited physical ability and nutrition training, and lack the means to adequately communicate with clients and available volunteers. As a result, there may be a general lack of capacity to support a client choice model.Citation8 Food banks and pantries also experience regular challenges both individually and in working together. For example, there are communication challenges between food banks and pantries regarding what foods are available, and challenges at the food bank and pantry level related to meeting clients’ needs and preferences. Recent evidence suggests that systems need to be developed to address mismatches between client demand and food banks to food pantry supply in general, and during disaster response.Citation9 The COVID-19 pandemic has heightened these barriers and underscored the need for intervention.Citation6 For example, food supply chain disruptions, and challenges related to staffing given that the food pantry volunteer population tend to be older adults (who were at highest risk during the pandemic) made it difficult for food pantries to stay open at all.Citation10–12 Importantly, providing a safe form of client choice during the pandemic was a huge challenge.

Public health efforts, including the charitable food system and other fields, are moving toward the adoption of digital strategies to support their operations and more effectively meet end-user needs.Citation9,Citation13–17 Such strategies are enticing giving the ubiquity of digital platforms, ability to personalize, improved communication, and cost effectiveness.Citation18–20 However, barriers to uptake include difficulties in set-up/onboarding, lack of technical support, and low user-friendliness.Citation18–20 Although several digital tools are available for use for food pantries for tasks such as inventory management, reporting, and scheduling appointments,Citation13 the adoption and use of digital tools by food pantries is not well understood. For example, tools like Link2FeedCitation21 and Oasis,Citation22 which were developed to support food pantry management tasks, lack information on how they were developed, and their effectiveness and level of uptake are unknown. A recent review outlines the number and types of tools available in the food assistance realm, and highlights the scarcity of 1) user-centered development approaches and 2) data on the uptake and effectiveness of the apps among its intended end-users.Citation13 Furthermore, it is unknown how pantry characteristics, such as pantry size and related staffing capacity, impact their ability to implement digital tools. These gaps urgently need to be addressed in order to improve food pantry services. By understanding food pantry needs and desires related to enhancing pantry management, the design and development of digital tools may be enhanced, increasing uptake. Ultimately, the mismatch between client needs and preferences and food pantry operation may be reduced.

Therefore, we conducted a nationwide survey of food pantries guided by the following aims:

To define the types of digital tools currently used by food pantries and how they are used.

To identify which features are most desired and needed for a food pantry support digital tool, as expressed by pantry managers and staff.

To explore whether digital tool usage, or desire for digital tools, differs by pantry size.

Methods

An online nationwide survey of U.S. food pantries was conducted from January 2022 to June 2022. Survey questions were developed based upon findings from a recent scoping review of existing literature,Citation13 and via iterative conversations with food pantry directors in Baltimore City, Maryland, and faculty experts in food pantry management and emergency preparedness at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. The survey link was delivered via e-mail and completed through Google Forms.

Pantry Sample Identification Strategy

The online food pantry database, foodpantries.org,Citation23 was used to identify pantries to invite to participate in the survey. Foodpantries.org is an online portal where over 15,000 food pantries across each state can voluntarily enter their contact information. In an effort to balance time and resources with representation of all U.S. states, the database was systematically searched such that every 10th food pantry on each state list was selected. If there was no e-mail address listed, the next pantry was selected until a pantry with an e-mail address was identified. A database of food pantry e-mails was compiled and kept in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet on a secure Johns Hopkins OneDrive server.

Follow-Up Strategy

If there was no initial response, a follow-up e-mail was sent approximately one week later. Two more follow-up reminder e-mails were sent approximately one month apart for pantries that had still not responded.

Online Survey Components

The survey was comprised of four sections for a total of 26 questions. The first section included participant and pantry background questions, including the respondent’s role at their food pantry and general pantry features, such as the pantry zip code, size, programs offered, and client choice model utilization before and after the pandemic.

The second section pertained to the availability of electronic devices at the pantry, such as smartphone ownership among food pantry staff, volunteers, and clients, and availability of electronic devices (i.e., desktop computers, laptops, iPads, tablets, or other mobile devices) at the pantry.

The third section probed on the availability and/or desire for specific app or software features to improve the operations and management of their food pantry. Possible features included inventory management; staff/volunteer recruitment, scheduling, and training; client communication; and tracking pantry statistics. Each question listed several response options where respondents could “select all that apply,” and the option to select “other” with space for elaboration. Each response list had an option for “an app or software on my phone” and “an app or software on my computer” in order to probe on specific digital tools. If a respondent selected one or both of those options, they were subsequently asked to list the specific tool used using a free text field.

The final section of the survey included a list of pantry management tasks. Respondents were asked to indicate which management tasks they desired that an app or software could support. The tasks listed included: inventory; tracking pantry numbers; training, recruiting, and scheduling of staff/volunteers; communication with staff/volunteers, and clients; online ordering for clients; providing client choice; scheduling client appointments; client registration; enrolling clients in other food assistance programs; and connecting with emergency services in the area (see supplemental material).

Ethical Considerations

No personal identifying information was collected outside of the name of the food pantry, which was an optional field in the survey. This study (#9034) was considered exempt by the Johns Hopkins University Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Response Rate

A total of 1,095 food pantries were contacted via e-mail. After removing duplicates, there were a total of 297 responses (a 28.8% response rate, excluding those who were unable to be contacted [n = 63] from the denominator). Reasons for “declining to participate” included: they do not have a food pantry (n = 10), no longer have an operating food pantry since the pandemic (n = 9), concern that results from this survey would inform food pantry regulations and restrictions (n = 1), and not interested in participating (n = 1). Those who were unable to be contacted had inactive e-mail addresses. See for the full study recruitment flow diagram.

Analysis

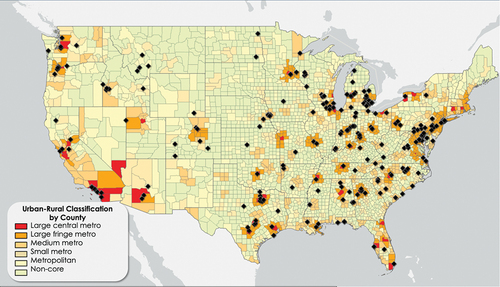

Descriptive statistics were used to summarize each section of the survey in terms of pantry characteristics, access to digital devices, current use of apps and software, and desire for specific management features. Responses were then divided and analyzed by pantry size (small (<10,000 pounds of food distributed/year), medium (10,000–24,999 pounds of food distributed/year), large (25,000 pounds or more of food distributed/year). We based these numbers on the Maryland Food Bank’s classification system for food pantry size given our collaboration with them and the lack of a published standardized classification system. The analysis was conducted in Microsoft Excel. The distribution of pantry locations was mapped using ArcGIS mapping tool (Esri, Redlands, CA).

Results

shows where the participating food pantries were located. There were 46 states represented. In general, there was a higher concentration of respondents in the north-eastern part of the U.S., and fewer responses from more rural locations. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize pantry characteristics, access to digital tools, current use of digital tools, and desire for specific management features.

Respondent and Pantry Characteristics

Most survey respondents (95.6%) were food pantry directors or managers. The majority of respondents owned a smartphone (87.5%), and reported that, on average, about two-thirds of their clients also owned/had access to a smartphone. Most pantries who participated in the survey were large (55.3%) or medium (19.3%) sized pantries. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 66.2% of respondents reported utilizing a client choice model, while only 38.5% reported continuing to do so after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. For a full description of participating food pantries, see .

Table 1. Characteristics of food pantries who participated in an online nationwide survey of food pantries from January-June 2022 (n = 297).

Current Pantry Management Strategies

The most common methods (participants could select all that applied) used for inventory management were visual assessment (62.3%), and paper and pencil (48.5%). The most common methods used for recruiting volunteers and staff were word of mouth (87.2%), and e-mail (36.4%); and phone calls (32.3%) and e-mail (32.0%) for scheduling volunteers and staff. Staff and volunteer trainings most often took place in person (68.4%), with a few mentioning the ability to conduct training via Zoom (6.7%) or via prerecorded sessions (6.1%). For client management, most respondents reported using phone calls (57.5%) or e-mail (32.5%) to communicate with clients. Most respondents said they kept track of important pantry statistics using paper and pencil (49.2%) and/or an app or software on their computer (45.1%). Of those who indicated use of food pantry specific app or software on their phone, the most common tools mentioned were Link2FeedCitation21 (n = 27) and Oasis (n = 11).Citation22

Desire for an App or Software for Different Aspects of Pantry Management

The most frequently indicated food pantry app or software features of interest included, in rank order, staff and volunteer scheduling (49.2%); inventory management (42.1%); communicating with volunteers and staff (35.7%); client registration at the food pantry (35.4%); and tracking pantry statistics (33.7%). About 22% of respondents expressed the need for a feature that allowed for communication with nearby emergency services.

Desired features were then grouped by two main management domains: staff and volunteer management and client management. Staff and volunteer features included communication, recruitment, scheduling, and training. Over half (55.2%) of respondents indicated interest in at least one client management feature, and 37% selected at least two or more related features. Client features included registration, communication, online ordering, client choice, scheduling appointments, and enrolling clients in other food assistance programs. There was particular interest (41.4%) in providing client choice, either through general online ordering or providing specific choice options through a digital application.

Tool Use by Pantry Size

In general, large and medium food pantries had better access to electronic devices (e.g., laptops, desktops, tablets, smartphones) as compared to small pantries (see Supplemental Table S1). Relatedly, there was greater interest in apps and software among large and medium pantries as compared to small pantries (). In particular, there was less interest from small pantries compared to large/medium pantries in terms of logistical aspects of management, such as communicating with staff, volunteers, and clients, tracking inventory, and scheduling.

Table 2. Desire for digital tool features by size of food pantries who participated in an online nationwide survey of food pantries from January-June 2022 (n = 268*).

Discussion

This is the first study to explore what digital tools are being used by food pantries, and for what specific aspects of pantry management. Overall, we found high rates of smartphone ownership among respondents and their clients, supporting the idea of utilizing smartphone-based digital tools for management in food pantry settings. Even among those who reported not owning a smartphone, about half still indicated they would be interested in using an app for pantry management. Of those who were interested in using an app or software, the most desired features involved management of pantry logistics (inventory, registration, tracking pantry statistics), scheduling of staff and volunteers, and communication. Larger pantries, which most often reported having higher availability of electronic devices, tended to have greater interest in an app or software for pantry management.

There are many apps and software options available for pantry management, with most only supporting 1–2 aspects of management.Citation13 Food pantries have limited time and staff, and may not have the capacity to use multiple tools (in addition to existing food bank websites and reporting portals) to manage their pantries. Further, most existing tools are not geared toward older adult populations who comprise the majority of food pantry staff and volunteers, nor do they provide assistance for setting up or maintaining the tool. What is needed is a tool developed with a user-centered design approach. Such a tool would enable efficient pantry management with multiple desired features bundled into one digital application, in order to ease workflow without being burdensome. However, logistical issues related to the sustainability of assisting with tool set-up and maintenance, and long-term data management and storage are potential challenges that must be considered. Existing tools in the food assistance arena have originated from philanthropic endeavors that quickly expand to global levels (e.g., Link2Feed).Citation21 Perhaps localizing where food bank and food pantry digital tools are housed could streamline set up and provide a means for sustainable tech support. To our knowledge, study of these issues specifically in food pantries has not yet occurred, and is needed in order to create and refine digital tools to support them.

Food pantries rely heavily on food supplied from food banks and donations, and therefore supply of healthy options is not always consistent.Citation8,Citation24,Citation25 Instead, there is a focus on keeping shelves stocked so that clients have access to enough food, which is not always in alignment with health considerations as reported by pantry staff/volunteers and clients.Citation26 An app or software could allow pantries to: 1) expand where they obtain food from in order to improve consistent stock of healthy options (e.g., local farmers or producers, donors, gleaners), 2) track client preferences related to healthy options to report to their affiliated food bank to show demand for specific items, and 3) communicate with clients when healthy products (especially fresh, perishable product) arrive at the pantry to reduce spoilage. A tool of this nature would require input from all key stakeholders to ensure effectiveness, usability, and user-friendliness.

Interestingly, survey respondents indicated interest in an app or software to support client choice either in the form of general choice within the pantry (browsing the shelves and making selections) or online ordering (making their choices ahead of time and picking up their food afterward). Previous literature has shown that providing client choice improves healthy food selections,Citation5 and that staff and volunteers play a key role in assisting clients with making healthy choices.Citation26 However, food pantry staff and volunteers may have limited nutrition knowledge,Citation27,Citation28 and the logistics of supporting healthier client choices on a digital platform, such as a smartphone application, are not well understood. A tool that simply lists the foods available at the pantry and allows clients to make their choices remotely (online ordering) would certainly be helpful during crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as for pantries with limited hours of operation and staff. But, additional exploration of how nutritional messaging could be incorporated into this type of feature is needed in order to understand what type of messaging would be most useful to food pantry staff, volunteers, and clients, given the limitations within the food assistance food system.Citation24 For example, general nutrition messages related to nutrient content of certain foods and the associated health benefits (e.g., carrots have high vitamin A content which is good for eye health), or more targeted “nudging” or messaging for diet-related chronic diseases which clients have shown interest in in previous studies,Citation26,Citation29 such as hypertension, diabetes, etc., (e.g., selecting low-sodium options when available, rinsing canned items, putting together a carbohydrate-controlled diet using food pantry items).

Inclusion of client choice or a modified version of client choice supports the emerging aim of national organizations like the USDA to not only address food security but food and nutrition security.Citation30 Food security predominately focuses on the acquisition of food, with minimal focus on quality of that food. Nutrition security goes beyond simply meeting caloric needs, and considers access to nutrient-dense foods that contribute to health and chronic disease prevention and treatment.Citation31–33 Using digital tools to increase client choice may help show demand for healthier options, as well as assist pantries with supplying a consistent stock of appropriate healthy food products to meet this need. In doing so, the charitable food system can begin to shift from addressing food security to also addressing nutrition security and contributing to improved diet quality among clients.

This study was novel in that it probed on current and desired tool utilization among food pantries, and aimed to capture food pantries across the U.S. to increase generalizability. The response rate was 28.8%, which is fair as compared to other studies of food pantries.Citation6,Citation34,Citation35 However, these findings should be considered preliminary due to several limitations. First, little is known about the foodpantries.org database (i.e., who uploads the food pantry contact information, is it maintained/updated regularly, and whether it covers all existing food pantries) and is therefore likely not comprehensive. Many food pantries could have been missed using this search strategy. At the same time, to our knowledge, there is no other comprehensive database of food pantries that can be easily accessed. Previous studies have utilized Feeding America’s website to locate food banks and request that the food banks distribute the survey to their affiliated pantries. This method requires a significant amount of time and resources, as well as a virtually unknown denominator and response rate. There were four states not represented in our survey; we opted not to oversample those states at the risk of reducing the reproducibility and reliability of our search strategy. We also had fewer responses from rural locations; we speculate that these operations may be smaller and thus lack staff capacity to keep up with e-mail, social media, and/or websites. Given that not all respondents were food pantry directors or managers, we cannot ensure that the most knowledgeable staff person completed the survey. Finally, this survey was not validated before it was disseminated. We conducted face validation with a small group of experts, but testing with food pantry staff and key stakeholders was not done due limited resources.

Conclusion

This study provides insights into the current state of digital tool use in pantries, and desire for specific management features to be addressed in future tools. Overall, food pantry staff and volunteers desire accessibility of digital features related to both staff/volunteer and client management, and there was particular interest expressed in digital assistance with staff and volunteer scheduling, inventory management, and communicating with volunteers and staff. There is a need for a user-centered design approach to develop a tool for food pantry management, and findings from this study, augmented by existing literature, show a need to explore, in-depth, the barriers and facilitators related to uptake and sustainability of such a tool among food pantries. A robust digital tool could provide an opportunity to improve the disconnect between client needs/preferences, and pantry operations.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (43.3 KB)Acknowledgements

The first author (SM Sundermeir) would like to acknowledge the generous support received from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health T32 Predoctoral Clinical Training Grant.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/19320248.2023.2228728

Additional information

Funding

References

- Food Security in the U.S.: Key Graphs and Statistics. United States department of agriculture economic research service website. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-u-s/key-statistics-graphics/#insecure. Published September, 2021. Accessed March, 2022.

- Food Security in the US: Key Statistics & Graphics. The United States department of agriculture website. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/key-statistics-graphics.aspx. Published September 8, 2021. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- The Impact of the Coronavirus on Food Insecurity in 2020 & 2021. Feeding America’s website. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2021-03/National%20Projections%20Brief_3.9.2021_0.pdf. Published March, 2021. Accessed September 16, 2021.

- Hunger in America. Feeding America’s national report; 2014. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2020-02/hunger-in-america-2014-full-report.pdf Accessed August 16, 2022.

- An R, Wang J, Liu J, Shen J, Loehmer E, McCaffrey J. A systematic review of food pantry-based interventions in the USA. Public Health Nutr. 06, 2019;22(9):1704–1716. doi:10.1017/S1368980019000144.

- Caspi CE, Davey C, Barsness CB, et al. Needs and preferences among food pantry clients. Prev Chronic Dis. 04 01 2021;18:E29. doi:10.5888/pcd18.200531.

- Remley DT, Kaiser ML, Osso T. A case study of promoting nutrition and long-term food security through choice pantry development. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2013;8(3):324–336. doi:10.1080/19320248.2013.819475.

- Sally Y, Caspi C, Angela C, Trude B, Gunen B, Gittelsohn J. How urban food pantries are stocked and food is distributed: food pantry manager perspectives from baltimore. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2020. doi:10.1080/19320248.2020.1729285.

- Martin NM, Sundermeir SM, Barnett DJ, et al. Digital strategies to improve food assistance in disasters: a scoping review. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. Oct 11 2021;17:1–10. doi:10.1017/dmp.2021.281.

- Aday S, Aday MS. Impact of COVID-19 on the food supply chain. Food Qual Saf. 2020;4(4):167–180. doi:10.1093/fqsafe/fyaa024.

- Belarmino EH, Bertmann FMW, Wentworth T, Biehl E, Neff R, Niles MT. The Impact of COVID-19 on the Local Food System: Early findings from Vermont. College of Agriculture and Life Sciences Faculty Publications. 2020. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/calsfac/23.

- Cummins S, Berger N, Cornelsen L, et al. COVID-19: impact on the urban food retail system and dietary inequalities in the UK. Cities Health. 2020. doi:10.1080/23748834.2020.1785167.

- Martin NM, Barnett DJ, Poirier L, Sundermeir SM, Reznar MM, Gittelsohn J. Moving food assistance into the digital age: a scoping review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. Jan 25, 2022;19(3):1328. doi:10.3390/ijerph19031328.

- WHO. WHO guideline: recommendations on digital interventions for health system strengthening. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2019. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- Rose T, Barker M, Maria Jacob C, et al. A systematic review of digital interventions for improving the diet and physical activity behaviors of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. Dec 2017;61(6):669–677. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.05.024.

- Beleigoli AM, Andrade AQ, Cançado AG, Paulo MN, Diniz MFH, Ribeiro AL. Web-based digital health interventions for weight loss and lifestyle habit changes in overweight and obese adults: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 01, 2019;21(1):e298. doi:10.2196/jmir.9609.

- Wu J, Guo S, Huang H, Liu W, Xiang Y. Information and communications technologies for sustainable development goals: state-of-the-art, needs and perspectives. IEEE Commun Surv Tutorials. 2018;20:2389–2406. doi:10.1109/comst.2018.2812301.

- Pang C, Wang ZC, McGrenere J, Leung R, Dai J, Mofatt K. Technology adoption and learning preferences for older adults: evolving perceptions, ongoing challenges, and emerging design opportunities. In CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI ’21), May 08–13, 2021, Yokohama, Japan; 2021. ACM, New York, NY, USA, pp. 13. 10.1145/3411764.3445702.

- Whitelaw S, Pellegrini DM, Mamas MA, Cowie M, Van Spall HGC. Barriers and facilitators of the uptake of digital health technology in cardiovascular care: a systematic scoping review. Eur Heart J Digit Health. Mar, 2021;2(1):62–74. doi:10.1093/ehjdh/ztab005.

- Svendsen MJ, Wood KW, Kyle J, et al. Barriers and facilitators to patient uptake and utilisation of digital interventions for the self-management of low back pain: a systematic review of qualitative studies. BMJ Open. Dec 12, 2020;10(12):e038800. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-038800.

- Link2Feed. https://www.link2feed.com/. Published December 14, 2020.

- Oasis Insight. https://oasisinsight.net/. Published July, 2022.

- Foodpantries.org. https://www.foodpantries.org/.

- Byker Shanks C. Promoting food pantry environments that encourage nutritious eating behaviors. J Acad Nutr Diet. Apr, 2017;117(4):523–525. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2016.12.020.

- Caspi CE, Canterbury M, Carlson S, et al. A behavioural economics approach to improving healthy food selection among food pantry clients. Public Health Nutr. 08, 2019;22(12):2303–2313. doi:10.1017/S1368980019000405.

- Cooksey-Stowers K, Read M, Wolff M, Martin KS, McCabe M, Schwartz M. Food pantry staff attitudes about using a nutrition rating system to guide client choice. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2019;14(1–2):35–49. doi:10.1080/19320248.2018.1512930.

- Remley DT, Franzen-Castle L, McCormack L, Eicher-Miller HA. Chronic health condition influences on client perceptions of limited or non-choice food pantries in low-income, rural communities. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):105–118. doi:10.5993/AJHB.43.1.9.

- Chapnick M, Barnidge E, Sawicki M, Elliott M. Healthy options in food pantries—a qualitative analysis of factors affecting the provision of healthy food items in St. Louis, Missouri. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2019;14(1–2):262–280. doi:10.1080/19320248.2017.1284027.

- Dave JM, Thompson DI, Svendsen-Sanchez A, Cullen KW. Perspectives on barriers to eating healthy among food pantry clients. Health Equity. 2017;1(1):28–34. doi:10.1089/heq.2016.0009.

- Agriculture USDo. Food and nutrition security: What is nutrition security? https://www.usda.gov/nutrition-security#:~:text=Nutrition%20security%20means%20consistent%20access,Tribal%20communities%20and%20Insular%20areas. Published April 18, 2023.

- Ingram J. Nutrition security is more than food security. Nat Food. 2020;1(1):2–2. doi:10.1038/s43016-019-0002-4.

- Mozaffarian D, Fleischhacker S, Andrés JR. Prioritizing nutrition security in the US. JAMA. Apr 27, 2021;325(16):1605–1606. doi:10.1001/jama.2021.1915.

- USDA Announces Actions on Nutrition Security. U.S. department of agriculture website. https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2022/03/17/usda-announces-actions-nutrition-security. Published March 17, 2022. Accessed August 3, 2022.

- Companion M, Companion M. Constriction in the variety of urban food pantry donations by private individuals. J Urban Aff. 2010;32(5):633–646. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9906.2010.00511.x.

- Joly BM, Hansen, A, Pratt J, Michael D, and Shaffer J. A descriptive study of food pantry characteristics and nutrition policies in maine. J Hunger Environ Nutr. 2020;15(4):514–526. doi:10.1080/19320248.2019.1675564.