ABSTRACT

Background

Reducing opioid reliance in chronic pain treatment may best be accomplished with interdisciplinary teams. Shared Medical Appointments (SMAs) are one format whereby an interdisciplinary team partners with groups of patients to provide health education and clinical care. The Whole Health (WH) model is an emerging framework whereby the care team partners with the patient to reach shared goals with emphasis on self-care and healing modalities.

Purpose

Assess the impact of a WH Education intervention in patients with chronic pain and long-term opioid use within the framework of Shared Medical Appointment (SMA).

Results

Retrospective chart review of 86 participants indicated significant opioid reduction at 12 and 24 months. The rate of opioid reduction in the SMA group surpassed the rate of decline of the host or national VA cohorts. Overall pain perception did not increase while patient satisfaction and safety indices improved.

Discussion

Results of the intervention suggest that a WH education model in a SMA is one approach to help patients reduce long-term opioid reliance.

Translation to Health Education Practice: Trained Whole Health Coaches/Education Specialists are key personnel in the implementation of the WHSMA model of care and facilitators of behavioral change that results in improved wellness outcomes.

A AJHE Self-Study quiz is online for this article via the SHAPE America Online Institute (SAOI) http://portal.shapeamerica.org/trn-Webinars

Background

The scope of the national opioid crisis

The national opioid epidemic is one of the most serious manmade health crises of the last decade resulting in an unprecedented number of deaths from both illicit and prescription drugs.Citation1 Despite gains in reducing opioid prescriptions, opioid-related deaths remain at an all-time high and have increased during the Coronavirus Pandemic from 2020 to 2022.Citation2 In order to grasp the magnitude of the opioid crisis, a brief review of vital statistics surrounding the epidemic is helpful. Opioid prescribing for the treatment and relief of chronic pain has risen precipitously over the last several decades, with approximately 4% of U.S. adults consuming opioids for chronic pain relief.Citation3,Citation4 There are direct correlations between the number of prescriptions written and overdoses.Citation5 In 2017, an estimated 17.4% of the U.S. population was prescribed one or more opioids, with the average person receiving 3.4 prescriptions.Citation6 Both illicit and prescribed opioids were responsible for 47,600 overdose deaths in the United States and 67.8% of all overdose deaths in 2017.Citation7 Opioid-related overdose deaths rose from 21,089 in 2010 to 47,600 in 2017 and remained steady through 2019. In the first year of the Corona Virus Pandemic in 2020, there were 68,630 reported deaths from opioids. On a local level, from 2016 to 2017, the state of Alabama experienced an 11% increase in death rates from opioids. In 2017, Alabama providers wrote 107.2 opioid prescriptions for every 100 persons, the highest prescribing rate in the nation, and almost twice the average U.S. rate of 58.7 prescriptions.Citation8

Etiology of the rise in opioid related deaths

Over the last decade, and despite many of the recommendations of the Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) in 2013, opioid-related deaths remain at an all-time high. In 2017 the US Dept. of Health and Human services declared the opioid crisis a public health emergency.Citation9 While there appears to be a slight downward trend in deaths related to prescription drugs, the availability of the synthetic opioid fentanyl, has likely contributed to the persistent overall increase in opioid-related deaths.Citation4,Citation10 The relationship between prescription opioids and use of illicit drug use are complex with several associations of particular interest. One is the use of prescription opioids over time renders the user susceptible to Opioid Use Disorder (OUD).Citation11 OUD, in addition to being a risk factor for overdose, is associated with other health-related co-morbidities. These co-morbidities include but are not limited to sleep disturbances, communicable diseases, COPD, hypertension, coronary artery diseases and trauma-related injuries. In addition, there are negative impacts on finances and the physical and mental health of family members.Citation12

There are a number of important factors believed to have contributed to the current opioid crisis with the Health Care System being partly to blame.Citation13 First, the beginning of widespread treatment of non-cancer pain in the early 1990s underestimated the long-term harmful effects especially with patients with COPD, sleep apnea, or mental health conditions.Citation13 As such, both providers and consumers took a biased view that opioids were a simple solution to a complex problem of pain. Second, pharmaceutical companies took an aggressive marketing and promotion strategy of opioids, which overexaggerated their benefits particularly that of the long-acting opioid oxycontin. Third, the introduction of the pain score as the “fifth vital sign” as a clinical indicator of patient well-being has been suggested as one of the turning points for an upward trend in opioid prescribing.Citation9 Consequently, consumer expectations for treatment with opioids have increased. Fourth, the opioid market has also had profound influences on the epidemic with the availability of high potency opioids such as heroin and fentanyl in the illicit drug trade. Use of prescription drugs has served as a stop-gap for users to prevent withdrawal and thus has increased their street value. As a consequence, there has been an increase in diversion of prescription drugs for non-medical uses and self-treated opioid use disorder. Lastly, “pill mills” from unscrupulous providers may have fueled overdoses and opioid use disorders in certain communities.

History of Veteran’s opioid use for pain

Military Veterans have been severely affected by the opioid epidemic. Between the years 2010 and 2019, there was a 50% increase in overdose mortality in the veteran population.Citation14 Military-related musculoskeletal injuries are often the entry point for individuals into the VA health care system and chronic pain is perhaps the single most important factor for using opioids. Indeed, chronic pain has been reported by 50% of Veterans.Citation15 The factors leading to opioid dependence are indeed complex with chronic pain, psychosocial factors such as depression, anxiety, and PTSD being major contributors.Citation16 These factors have led to an upward trend in opioid prescribing within the VA.Citation15 Our VA medical center is no exception and over the years opioid prescribing has paralleled national trends. Consequently, many veterans with chronic pain have been on opioids for years. Both patient and provider fatigue in finding other pain-remitting modalities may be contributors to long-term opioid use.Citation14 Long-term use in the aging veteran population with comorbidities such as sleep apnea, COPD and depression, known risks associated with respiratory depression and accidental overdose, highlight the need for alternative pain remitting modalities.

A national response to the opioid epidemic

The opioid epidemic has necessitated a comprehensive response from the health care system including the Veteran’s Administration. One such response was the government-sponsored Opioid Safety Initiative (OSI) which began in 2013.Citation17 With the OSI new guidelines were developed to assist providers in making decisions for initiating, continuing, and tapering opioids for use of both acute and chronic pain. While the number of opioids being prescribed has declined as a result of the initiative, it has not reversed the trend in opioid-related deaths which unfortunately increased during the COVID Pandemic from 2020 to 2022. Some of the key features of the opioid safety initiative included important revisions of opioid prescribing practices. One safety strategy directed at preventing overdoses has been the widespread distribution of Narcan kits which reverses the effects of an opioid overdose.Citation18 Other strategies have included the use of the Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (PDMP). The PDMP is a national database whereby scheduled drugs are reported by pharmacists and can be accessed by prescribers prior to ordering another scheduled medication and helps reduce duplication of certain medications. There has also been a focus on recommending reducing the amount prescribed, particularly for patients using >100 mg equivalents of morphine.

A shift from opioid-centric to comprehensive pain management

The VA Health Care System has taken a proactive stance to the opioid crisis through support of safer opioid prescribing practices and through providing state-of-the art approaches to pain management. Initiatives for promoting safer opioid prescribing have included use of a PDMP. PDMP data can be readily accessed for any patient in the VA electronic database (Computerized Patient Record System or CPRS). Elements of the PDMP include requiring patients on long-term opioids to have a Narcan kit in the home. Secondly, patient databases or Dashboards interface directly with the patient’s medical record so providers can track aspects of patient’s clinical data such as date of last urine drug screen, and last check of the PDMP. A Risk Index for Overdose or Serious Opioid-Induced Respiratory Depression (RIOSORD) is provided to assist prescribers in determining which patients may be at greatest risk for opioid-related overdose. Factors included in the risk calculation include gender (male), history of alcohol abuse or illegal substances, or mental health conditions such as ADD, anxiety, PTSD, and major depression. Another tool for assessing risk is the Stratification Tool for Opioid Risk Management (STORM) available on any patient in the VA CPRS electronic database. The STORM index incorporates factors such as prior history of mental illness, substance use disorders, prior adverse events and ER visits. While the RIOSORD and STORM index does not determine or dictate whether a prescriber will initiate or continue an opioid, it does provide information that can assist with counseling patients on their safety risks so patients can make informed decisions about long-term use.Citation19,Citation20

The prior state of opioid prescribing practices

To develop a clearer view of a future state of safer prescribing of opioids to see how a clinical prescribing model needs to evolve, it is helpful to examine the former state of opioid prescribing. Prior to the OSI, a typical opioid prescribing protocol was directed at reducing pain primarily with opioid analgesics. Indeed, VA provider training workshops in the early 2000s were held on how to escalate short acting opioids to a maximum dose (e.g. 10 mg four times a day of hydrocodone or oxycodone (with or without acetaminophen)). If the patient was still having breakthrough pain, then a long-acting opioid such as extended-release morphine or methadone was initiated at 5 mg once or twice a day, and escalated monthly until the patient received a satisfactory level of pain control. While this approach had a certain logic to it, it clearly underestimated the risks associated with long-term and higher doses of opioids as patients required increasing levels of medication due to tolerance, hyperalgesia, and loss of efficacy. Consequently, over time many veteran patients were on hundreds of morphine equivalents of pain medication while still reporting pain levels that were not trending downward. Moreover, it has been shown that higher doses of opioids place patients are risk for accidental overdose.Citation14

A need for better pain-remitting modalities

As the emphasis in pain management has moved away from an opioid-centric paradigm, the demand for additional pain-remitting modalities has increased. In addition to analgesic medications, there has been an emphasis on restorative therapies (e.g. physical therapy), interventional procedures (e.g. pain blocks), behavioral health approaches (e.g. cognitive behavioral therapy) and finally, holistic approaches using complementary alternative modalities (CAMs) and integrative health modalities (e.g. Yoga, Tai Chi, Acupuncture, and chiropractic care). Once thought of as alternative medicine, CAMs are now viewed as evidence-based modalities of care with clear benefits for patients with chronic pain.Citation21–26 The use of CAMs and integrative modalities is particularly attractive for a number of important reasons. For instance, Yoga and Tai Chi are modalities proven to help manage chronic pain. These modalities can be taught and replicated in the safety and comfort of one’s own home. Another benefit is cost saving as one staff member can lead groups in person or virtually. CAMs, which once were limited to multi-specialty or interdisciplinary care teams, are now growing in their adaptability for use in primary care clinics, home exercise programs, or through virtual care, thereby expanding access for patients.Citation27

Engaging patient participation through shared medical appointments

Getting patients engaged in integrative modalities is probably best accomplished within the context of inter- and multi-disciplinary teams where patients can receive education of the modality and the value of the modality is supported across disciplines. One approach to bring different disciplines together in a single encounter is the use of Shared Medical Appointments (SMAs). In SMAs, patients with a similar medical condition are brought together for an extended appointment where a single or multiple providers can provide education as well as clinical care. SMAs have shown benefits for patients with chronic diseases such as diabetes, heart failure and chronic pain.Citation28–33 Because SMAs are adaptable in primary care settings, they are ideal for bringing together inter- or multi-disciplinary teams of Subject Matter Experts (SMEs) in a single visit. In a prospective study, Romanelli et al. demonstrated the benefit of SMAs for addressing various chronic medical conditions, including chronic pain.Citation34 Survey data from 130 patients who attended the SMAs showed improvements in patients’ confidence levels to manage their pain and their healthcare team’s ability to assist them in managing their pain.

Use of the Whole Health model

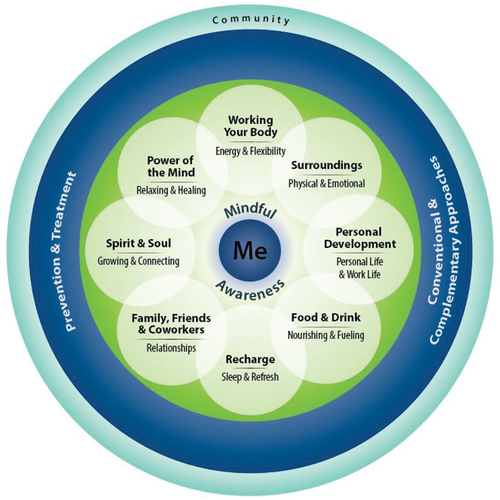

As with any behavior change, patient readiness is a key component for adopting and sustaining a plan-of-care and lifestyle changes. With respect to chronic pain self-management, a barrier to overcome is fear that the intervention may not be effective, or worse, aggravate the condition. The Whole Health (WH) model is a conceptual framework that is designed to foster patient “buy in” by allowing the patient to choose an area of self-care which focuses on patient-centered goals of achieving “what matters most” to them.Citation35,Citation36 () Through motivational interviewing and health coaching along with the development of shared SMART (specific, measurable, actionable, relevant, and timely) goals, a Personal Health Plan (PHP) is agreed upon that is personalized, proactive, and patient-centered.Citation35,Citation36 The WH model has been used in patients with diabetes and has led to improved clinical outcomes.Citation29 Consequently, there has been growing in interest using the WH model for improving patient outcomes with various chronic diseases. Efforts are now underway nationally to test the WH model in primary care settings in patients with chronic pain.Citation37

Figure 1. Proactive health and well-being model. The eight dimensions of Whole Health at the core of the personal health inventory self-assessment tool used in the quality improvement project. Adapted from “Whole Health for life: components of proactive health and well-being,” Reuse permission granted by U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, 2016.

Developing a Whole Health Education team

The Whole Health Model of Care is designed to foster well-being and optimized health. The WH Model is an approach to provide WH care between the VA provider, the Health System and the Veteran patient. A central feature of the WH model is the emphasis on self-care in the framework of well-being. Supporting the patient beyond self-care is a system that includes a full range of integrative, conventional, and complementary approaches. The VA WH System is built on three key components, The Pathway, Well-being Programs, and Whole Health Clinical Care. The Pathway is accomplished through education and information provided to the Veteran at any point along their journey within the Health Care System. One of the primary tools for introducing the Pathway is the Personal Health Inventory (PHI).Citation29 Through the use of the PHI, the veteran is introduced to Whole Health by exploring “What Matters Most” to them. With the assistance of a Health Coach/Health Facilitator or Health Education Specialist (HES), a Personal Health Plan (PHP) is developed that is unique, Personalized, Proactive, and Patient-Driven.

Within the Clinical Care component, the HES helps align the patient’s health and personal goals with conventional and integrative health care.Citation38 The PHP may include but is not limited to physical therapy, acupuncture, mindfulness, Yoga, Tai Chi and other interventional modes of care. Clinical care may be conventional care in both inpatient and outpatient settings, integrating healing environments and relationships and works seamlessly with well-being programs. The Whole Health care team is available to assist the veteran in setting goals to participate in Well-Being Programs. The VA has been a model system for integrated care with multiple services under one roof, providing a truly interdisciplinary/multidisciplinary approach to care. Whole Health centers on Veterans self-care and is not necessarily disease-based. Whole Health focuses on self-referral programs and services, emphasizes open access to Veterans, and provides support via multidisciplinary teams that may include but are not limited to Dieticians, Physical Therapists, Pharmacists, and Social Workers. The VA has been supportive of Whole Health for its employees.Citation39

Use of health coaches/HESs to foster health change

A major strength of the WH model of care is its emphasis on self-care modalities. A Health educator/health coach or Health Education Specialist (HES) is an important member of the care team where there are multiple components to the patient’s overall care plan. For instance, the health educator/coach/HES provides important information to the patient about the chronic medical condition and helps the patient make informed decisions about the different components of their health care plan. The VA has been proactive in the last decade in developing health educators/health coaches who play a larger role in the organization’s top health goals and priorities. To fulfill the mission of developing health educators/health coaches/HESs, the VA developed a two-week training program in the area of health coaching and motivational interviewing.Citation35 Health Educators/coaches/HESs are not limited to RNs or LPNs, but may include providers, pharmacists, dieticians, social workers, or peer support specialists. A health educator/coach/HES can play a key role in facilitating healthy living goals and self-care modalities. An example of a self-care modality would be achieving healthy restorative sleep using mindfulness based strategies. For self-care modalities, a health educator or health coach can assist the patient with identifying specific health goals and assisting the patient in making meaningful progress toward specific health goals. Achieving meaningful life and health goals can have a very powerful positive effect upon well-being. By meeting routinely with the patient over several weeks to months, the particular components of the overall health goal can be refined to address the patient’s individual preferences, consequently building patient confidence for making meaningful life-style changes.

Purpose

This Quality Improvement (QI) project was selected because our health care team has been seeking better solutions to assist patients in reducing opioid reliance and assist them in better managing their pain on a day-to-day basis without depending solely on an opioid. While gains have been made in recent years nationally and within the VA to improve opioid safety as a result of the OSI and changes in prescribing practices, our experience indicates that many patients are still reluctant to decrease opioids for a number of reasons. Consequently, our Primary care team sought through a QI project to change several aspects of our practice in treating patients that use opioids for chronic pain management.

The purpose of the following project is as follows

Assess the impact of a Whole Health Education intervention in patients with chronic pain and long-term opioid use within the framework of Shared Medical Appointment (SMA).

This will be accomplished through the following methods.

-Recruit patients to participate in the Whole Health SMA program through an initial brief education discussion on the value of the SMA and potential benefits of the intervention

-Train staff in how to implement the Whole Health model of care using resources developed by the VA’s Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT)

-Develop and train Health Educators/Coaches (Health Education Specialist (HESs)) to facilitate behavioral change using various techniques such as Motivational Interviewing

-Through a series of SMAs, introduce and educate patients on the Whole Health model of care, and introduce them to the Personal Health Inventory (PHI)

-Using the PHI, assist the participant in developing a Personal Health Plan (PHP)

-Facilitate patients in developing SMART shared goals, and provide support over time to build trust and foster patient confidence

Assessing the impact of the WH SMA intervention will be accomplished by examining several outcome measures.

First, participation in CAMs and other pain-remitting modalities will be tracked.

Second, opioid utilization will be tracked over time using the primary care Opioid Therapy Risk Reduction (OTRR) Dashboard to track opioid utilization after the intervention.

Third, patient’s self-perception of the program using a patient report card and self-reported pain scores will be monitored before and after the intervention.

Methods

Patient recruitment, engagement, and participation

Patients (n = 86) were recruited from a single VA provider’s primary care panel to participate in a nine-session opioid safety SMA. There was no threshold for opioid dose to be included or excluded. Patients were contacted by letter and phone to meet with the team nurse facilitator, learn about the purpose, start date, and what to expect at the SMA. Informed consent for long-term opioid therapy was obtained, a standard procedure for VA patients receiving long term opioids. Patients agreed to attend a 90-min orientation session (). Subsequent sessions after the orientation meeting were optional. Participants from group 1 attended sessions over 9 months. Patients were sent an appointment letter one week prior to the first SMA and called the day prior to the appointment to remind them of the time and location of the appointment. Patients were greeted by the Advanced Medical Staff Assistant (AMSA) at the conference room entrance and signed an attendance sheet. The AMSA entered their visit into the medical scheduling record for the daily appointment. Eligible participants were provided travel pay vouchers at the end of the SMA. Participants were given a three-ring binder containing the Whole Health SMA Toolkit. The Tool Kit contained information on opioid safety (VA Opioid Safety sheet), a blank PHI, and report card(s) to be filled out after each of the first nine sessions. They were provided with 4 × 6 index cards to place their requests at the end of the each SMA.

Table 1. Whole Health opioid safety 90 min sessions.

Curriculum development and clinical implementation

Team facilitation and engagement

We utilized the Primary Aligned Care Team (PACT) (MD, RN, LPN, MSA, PharmD) as HESs and course instructors for the initial 90-minute Whole Health SMA Orientation. The remaining eight sessions were considered Introduction. Meetings were held in a conference room one floor below the out-patient clinic affiliated with the Birmingham VA Health Care System. At the first session, team members were introduced. Ground rules for the SMA were briefly discussed. Verbal consent was obtained to discuss medical conditions within the privacy of the conference room. Our local Health Promotions Disease Prevention (HPDP) Program Director served as the meeting facilitator and HES for the first nine sessions. The facilitator coordinated the SMAs, secured the meeting location, facilitated the data collection tools, and determined topics for each SMAs’ education portion. For subsequent sessions, our PACT RN served as the facilitator. We allowed patients and spouses to introduce themselves and have a moment to verbalize what they would like to get out of the appointment. We provided a name card for each participant. Once the Whole Health Education curriculum was developed with Group I, we shortened the program to 9 weeks for Groups 2 and 3 in order to introduce the model of care to the remaining group participants. Midway through the first nine SMA sessions, two RNs, a LPN and a pharmacist were sent to the VA-sponsored 2-week Health Coaching program.

We invited local SMEs (Dietician, Physical Therapist (PT), Social worker, Psychologist, Chaplain, Peer Support Specialist) from our medical center to provide short didactic instruction in specific areas related to self-care and/or pain management. In addition, we utilized multimedia and short training videos from the VA Office of Patient Centered Care and Cultural Transformation (OPCC&CT) Web site as instructional videos for point-of-contact participation (e.g., Chair Yoga) and for promoting discussion and sharing of viewpoints. We provided extensive education on opioid safety at every session. At every session the clinical pharmacist gave a short didactic training session on opioid safety. These included use and storage of Narcan kits, opioid safe storage within the home, and use and effectiveness of other non-opioid medical modalities. Patients completed a 12-question satisfaction and participation survey () both before and after each of the nine sessions. We provided 4 × 6 index cards for patients to list their requests (e.g., medication refills, referral to PT or other CAM classes, or calls from SMEs). Requests were handled at point-of-care when feasible, or same day for Narcan Kit ordering, medication changes, prosthetic item ordering, and referrals.

Table 2. Results of SMA participation & clinical outcomes.

Table 3. Demographics and select clinical characteristics of Whole Health SMA participants.

Table 4. Pharmacotherapy modalities added or changed in Whole Health SMA participants.

Table 5. Non-pharmacotherapy modalities utilized by Whole Health SMA participants.

Table 6. Participant report card/survey pre- and post-SMA.

At the SMA orientation, we introduced the Circle of Health and Well Being () with the eight dimensions of self-care. The circle of health was used at every session as a way to start a conversation about a particular area of self-care. When appropriate we invited a SME to provide 10–15 min didactic sessions. For example, our weight management dietician gave short presentations on the areas of “Food and Drink” but participated in multiple sessions and was available for consultation as weight loss was a common goal for many of the participants. For the body movement sessions, we introduced integrative healing modalities such as Mindfulness, Tai Chi, and Yoga through educational videos and point-of-contact practice sessions. We had two veteran volunteers assist with weekly mindful exercises and chair Yoga. Extensive health coaching was provided to assess patient’s goals and establish SMART goals for self-care.Citation40 Lengthier health coaching sessions (3–5 min depending upon the number of patients participating on a given day) took place in the maintenance sessions in order for patients to modify or change their SMART goal.

Health Education and coaching

Patients completed the Personal Health Inventory (PHI) self-assessment tool to identify “What Matters Most” to them and to rate areas of the eight-dimensions of Self-Care on the Circle of Health that pertained to them and their health goals for optimum health.Citation29 Coaching sessions were performed by dividing patients into two groups of 10–12 patients each. Our HPDP Program Director, RN and LPN each received training in the VA-sponsored two-week health coaching program. The health coach/HES rotated throughout the group allowing each patient to answer questions based upon their PHI. Their overarching life goal was termed the mission, aspiration, and purpose (MAP). The patient was encouraged to identify a goal or activity to help them fulfill their MAP. The HES then helped the patient develop SMART goals which became their personalized health plan. Outlined below are some examples of Health Coaching Motivational Interviewing questions.

Conversation starters and vision questions

It would help me partner with you in your care if I understood what is important to you in your life.

As we work together on your health goals, could you describe a vision of your best possible health?

How does your current health impact what is most important to you?

What is your vision of your best possible health?

Connecting to the circle of health and well-being

In thinking about your best possible health, can you choose at least one self-care area that you would like to focus on today to support your health?

How would focusing on this area of self-care support your health right now?

What needs to change for you to achieve your best possible health?

Support needed

What steps are you interested in taking to make a change for your health?

What resources do you have that will help you achieve your goal?

What support do you need in this area of your life?

What support do you need from us, or your health team to make progress toward your goal?

Would you like more information on this area of self-care?

Are you interested in any specific referrals or resources to support your goal?

Patient’s goals were documented in the chart for every visit. End-point goals varied and may not have included a change in opioid utilization or use of CAMs. At the next visit, the patient reported on his/her progress. Computer access was available in the conference room for charting the visit and encounter, documenting patient goals, ordering medications, and entering consults for well-being programs or prosthetic items.

Data analysis methods

This Quality Improvement QI study consisted of a retrospective review of VA computerized patient medical records of patients who participated in a Whole Health and Opioid Safety Education SMA program, as well as survey results from handouts distributed in the class. The intervention for Groups 1, 2, and 3 was the Whole Health Education program and participation in the SMA. The non-SMA, while not a randomized control group, received usual care at routine clinic appointments. The non-SMA patients did not receive any formal education about the Whole Health model of care although they may have been encouraged to participate in pain-remitting modalities as part of their overall health care plan as well as have a discussion about tapering opioids.

Results

On the first day of the nine sessions, 29 patients presented for the course Orientation and Introduction. In subsequent sessions, Group 1 averaged 9 patients per session over the 9 months between Nov. 2016 and Aug. 2017 while Groups 2 and 3 averaged 20 and 22 patient respectively in weekly sessions (). Group 1 participants attended an average of 4.9 sessions while participants of Groups 2 and 3 attended ~7 sessions respectively. Maintenance sessions were continued from mid-2018 to March 2020 (monthly for 6 months then quarterly) with an average of nine patients/session with each patient attending ~3.5 sessions. Pain scores were assessed from three office visits pre- and post-SMA. Both groups 1 and 3 from the SMA group showed reductions in the average reported pain scores. There was a slight but insignificant increase in the pain scores for Group 2 and no significant reduction in pain scores in the non-SMA group. Participation in CAMs is summarized in for the SMA Groups 1–3 and the non-SMA group. The modalities used in the SMA groups are summarized in . Collectively, participants from group 1,2, & 3 participated in 34 CAMs (40% in SMA) vs. 8 (26% in non-SMA).

To assess the impact of the Whole Health Education and SMA intervention versus usual standard of care on opioid utilization within the single provider’s panel, the Computerized Patient Record System (CPRS) Opioid Therapy Risk Reduction (OTRR) dashboard was reviewed pre-and post-SMA. While the specific opioid prescribed is listed, the amount of opioid is presented as Morphine Equivalent Daily Dose (MEDD). One patient from each SMA group (1 to 3) was able to discontinue opioids during the SMA. An additional 10 patients (3, 3 and 4 from groups 1, 2, & 3) discontinued opioids throughout the 9-month maintenance phase (total of 13). Groups 1, 2, and 3 had average MEDD reductions of 43%, 30% and 28% respectively when assessed ~9 months from the end of the program (). The non-SMA group received education during individual patient appointments on opioid safety and the risks and benefits of long-term opioid use, but no other interventions occurred. Four patients (13%) from the non-SMA group were able to discontinue opioids.

To further assess the effectiveness of the SMA intervention versus usual standard of care during the SMA period, the single providers average MEDD per patient (Groups 1, 2 and 3 combined) was compared to the host facility and National MEDD utilization (). The MEDD utilization for the single provider’s PACT patient panel, included both SMA and non-SMA participants, and patients that were transient to the provider’s panel or on short term opioids only ( lower bold line). The patients on short term or transient opioids were excluded in order to compare MEDD reduction in the SMA and non-SMA groups. The average reduction of MEDD per patient was 27.1 (37%) in the SMA group and 14.5 (31%) in the non-SMA group (, upper 2 lines). There was an additional 9% reduction in average MEDD in the SMA group throughout the maintenance period while the non-SMA group showed a 9% increase. Compared to facility and national, the SMA participants continued to make reductions throughout the assessment period and to the conclusion of in-person group meetings in FY20Q2 (Fiscal Year 2020 Quarter 2).

Figure 2. Average MEDD (Y axis) per patient over Time (X axis) by yearly quartile. The PC Provider average MEDD per patient over time (solid bold line) included patients who participated in the SMA, non-SMA participants and patients transiently on opioids. The dotted and lower dashed lines represent average MEDD/patient of National and host facility. The MEDD/patient PC-provider was further partitioned into SMA and non-SMA participants (upper two lines + SEM).

Opioid reductions were tracked beyond the period of the SMA maintenance phase up to Sept. ’20 () in order to assess the sustainability of the patient’s individual programs. At the end of the SMA period in May ’18, 6% of SMA participants had discontinued opioids with 55% of the patients having made from 0% to 10% reduction. Over the next 18 months, opioid discontinuations increased to ~20% and stabilized. The group of patients making 0–10% or less, shrunk from 55% to 20%. Four of the patients (6%) who did not wish to discontinue opioids were amenable to conversion to Suboxone (buprenorphine/naloxone).

Figure 3. Distribution of opioid use reduction in the SMA combined groups over time. The lowermost part of the bar represents percentage of patients discontinuing opioids between May 2018 (end of SMA initiation phase and beginning of maintenance phase) and Sept. 2020. The groups represented as %Reduction were arbitrarily chosen as benchmarks to track success over time.

Patient demographics and engagement/modality results

is a summary of patient demographics of the combined groups. is a summary of percentages of patients prescribed additional non-opioid pharmacotherapy. is a summary of integrative/non-pharmacologic modalities implemented in the three groups during the study period. The most frequently identified goal was to improve pain management.

12-question report card results

Participants completed a 12-question survey pre-and post-SMA () to assess patient satisfaction with the program and self-report their progress. Of the 12 queries, the areas of reportable improvement pre-and post-SMA were the following: 1, 2, 6, 7, 9, 11, & 12. Of particular interest, patients reported managing their pain better, utilizing CAMs, and becoming more physically active (Ques. 2, 9,12). Patients rated question 3, 4, & 5 low (strong disagreement) and did not appear to change their responses to any degree pre-and post-SMA.

Discussion

The purpose of this QI project was to assess the impact of a Whole Health Education intervention in patients with chronic pain and long-term opioid use within the framework of a Shared Medical Appointment (SMA). The Whole Health Education model was introduced in the context of a SMA. The patients were educated on the Whole Health model of care which included a self-assessment Personal Health Inventory (PHI). The PHI was used to help each participant identify “What matters most?.” HESs were used to foster goal setting for the participants and for facilitating the development of SMART goals. The HES helped partner participants with integrative modalities to assist them with managing pain. Our PACT initiated its first SMA for Whole Health and Opioid Safety in November 2016. The first group of ~30 patients became the pilot for two subsequent SMA groups (2 & 3) who attended the course from Oct. to Dec. 2017 and March to May 2018, respectively. During the initial pilot, we developed a Whole Health Resource Tool Kit for staff and patients. Our team of HESs and SMEs learned how to set up a SMA and to keep patients engaged through interactive training videos, class instruction, and group participation. The comradery among the patients created a community that fostered sustained participation. The educational component of the program allowed patients to learn of new modalities for pain management such as mindfulness and chair yoga which could be done at point-of-care. By attending meetings, patients had exposure to team-based care and to learn from their comrades. Over time, participants were exposed to success stories from other veterans.

The value of the Whole Health-based SMA is clear from the results obtained in several areas including engagement in CAMs, reduction in pain scores, and decreased utilization of opioids. There were patients that made major reductions and even discontinuations in their opioid use that, prior to the SMA, had not been a possibility. Moreover, the reductions in opioid utilization were sustained over time. There are certain similarities with our project and that of Seale et al.Citation41 The Seal et al. team utilized an Integrated Pain Team (IPT) imbedded within primary care to engage patients in a multimodal pain care plan that included integrative mind-body modalities. They compared outcomes of opioid utilization in 147 participants using the IPT with 147 patients treated with usual patient care (UPC). The IPT participants had ~45% reduction in opioid dose at a six-month interval compared to 14% reduction in the UPC group.

In a large retrospective study by Bokhour et al. the team examined the health records of ~1.3 million Veteran patients (114,397 who were receiving care for pain) receiving care at 18 Whole Health pilot medical centers.Citation42 Over an 18-month period there was an 11% decrease in opioids in patients receiving conventional care. Patients who participated in any Whole Health modality had a 23% reduction in opioid use that was further reduced another 15% (to 38%) after intensive Whole Health interventions. By comparison, results from our Whole Health SMA study, demonstrated a decrease in average opioids dose (MEDD) by 21% at 9 months and 43% at 24 months. SMA groups 2 and 3 showed reductions of 30% and 28% at 24 months.

One of the positive benefits from this project was transitioning patients from conventional opioids (oxycodone, hydrocodone, methadone or morphine) to buprenorphine/naloxone (Suboxone). There are clear health benefits of buprenorphine over other opioids. For example, there is less respiratory depression with Suboxone, and it is preferred for opioid use disorder. It has been recommended to consider buprenorphine first-line opioid for chronic pain, especially in the elderly as it may be associated with less cognitive impairment, falls, and sarcopenia when compared with schedule II opioids.Citation43–45

Despite the onset of the Corona Virus Pandemic in March 2020 which prohibited in person group visits, at least two patients discontinued long term opioids through continued team support received through virtual group visits. Finally, one key observation from the WH SMA intervention, was that even with participation in a SMA and/or addition of CAMs and other pain-relieving modalities, certain patients made little or no reductions in their opioid utilization. This project did not address the reasons for not reducing opioid usage.

The SMA model of health care delivery allows for creating an environment for patient-centered shared goal setting. The use of the Whole Health model and the PHI allowed participants to self-reflect and identify “What Matters Most” to them. Through the use of PACT-trained health coaching in the SMA setting, our team assisted patients in developing SMART goals that were commensurate with their mission, aspiration and purpose as identified in the PHI. By identifying shared SMART goals, patients were able to develop their own personalized plan of care, whether it be weight loss, physical therapy participation, or simply managing stress better using mindfulness meditation. Data collected at the end of the SMA () indicated that a substantial number of patients participated in physical therapy (PT). Other non-opioid medical modalities were incorporated including topicals for pain, non-opioid oral medications, TENS units and acupuncture ( and ). The initial (start) doses for the non-opioid medications are provided in .

The 12-question survey corroborated with the chart reviews and indicated that patients were increasing their physical activity whether at home or through one of the mind-body integrative modalities offered through our PT department. We continued to observe sustained successes even beyond the initial 9-session course. Between June 2018 and March 2019, we continued monthly SMAs for graduates and observed continued opioid reductions. Indeed, most of the opioid reductions occurred after the initial 9-session WH SMA suggesting that healing modalities and readiness for change take time to develop.

The value of team-based care cannot be underestimated. There were certain patients with anxiety or PTSD, that were agitated from the moment they entered a room with other patients. These patients were gently escorted to a quiet room by one of the team members. Addressing their individual needs had to be done on a one-on-one basis in person or by phone. At least one patient filed a formal complaint stating they were not going to participate in “Eastern Religion” such as Yoga. On one occasion, a patient became ill and had to be taken to our treatment room and administered a Naloxone kit from an apparent unintentional opioid overdose. Of note there were no suicides or lethal overdoses during the study period.

Limitations to the QI project

There are several notable limitations to this study. First, it was not a randomized controlled trial. Second, there was likely clinical bias in the non-SMA group given our team also emphasized opioid reduction and use of pain-remitting modalities in patients that did not attend the SMA. Certain instruments have not been evaluated for reliability and validity such as the 12-question survey and the PHI. These assessment instruments merely served as guides to help us determine patient satisfaction and progress in the program. We continued with maintenance sessions for 6 months, then quarterly. Many of the participants did not make changes in their opioid use, but still expressed an interest in participating and meeting with other veterans. Looking back, there are several changes that could have been made at the start of the program. A pre-assessment “readiness for change” evaluation might have been useful to get an idea of patients who were contemplating a change in how they were managing their pain. For example, several patients noted at early visits that they wanted to discontinue opioids but did not feel ready or did not have a pain management strategy in mind were they to reduce or discontinue their medications. Education tips on safely tapering opioids were all that was needed to assist those patients ready to discontinue opioids. Indeed, it has been shown that for some patients on chronic opioids, just having a conversation about safety may be all that is needed to taper.Citation46 For others it was a re-introduction to traditional modalities such as physical therapy, something they had tried in the past, but had not really considered for years.

While it is unrealistic to believe that all patients with chronic pain will become opioid free, many patients are able to reduce their amount of pain medication and actually report lower levels of pain, suggesting that more complex physical and psychological factors are determinants of pain perception.Citation47 Indeed, patients that made the greatest reductions in opioids in our QI study tended to report lower pain scores. In summary, the Whole Health Education SMA is one clinical model that can be implemented in the primary care setting. The WH model is patient-centered allowing the patient to develop a personalized health plan. Positive outcomes from this QI project included improved engagement in CAMs from Veterans, improved satisfaction in terms of pain levels, decreased opioid reliance and improved safety with knowledge of Narcan kits.

Translation to Health Education Practice

The opioid crisis has highlighted the need for new approaches to assist patients in reducing their reliance on opioids and educating them on non-opioid pain-remitting modalities. To that end, this QI project reached a number of important endpoints. We utilized a SMA as a conceptual framework for patients to meet other veterans with similar conditions. The patients became engaged in the program and returned for subsequent sessions. Using the PACT-trained HESs, we were able to include our RN and LPN and clinical pharmacist directly in the patient’s decision making through the use of the PHI and PHP without the need for additional paid personnel. We used SMEs from our institution (social worker, psychologist, chaplain, physical therapist) at point of contact as well as Veteran Peer Support specialists who led patients in stress reducing mind-body exercises (e.g. mindfulness and chair yoga), thus providing a value-added appointment and learning experience for the veteran. Using the WH model, patients were able to get involved in CAMs. By developing trusting relationships with the staff, and improving patient’s attitudes toward their care, and better managing their pain, many of the participants were able to decrease and even discontinue their opioid use.

Role of the health coach/health educator/Health Education Specialist (HES)

Key personnel of this project are the RN/LPN/Pharmacist HESs. Their involvement in the project aligns with a number of priority areas of the National Commission for Health Education Credentialing Inc.Citation48 Area I: 1.1.2, 1.1.5 While not yet fully certified as a Certified Health Education Specialist (CHES), our team of health coaches/HESs assisted with identification of the priority population (patients with chronic pain on opioids) and 1.15, recruitment of the patients to participate in the SMA. Area 1.3, 1.3.1, 1.3.4 The HES assesses the patient’s current state of health at each meeting, uses Motivational Interviewing to identify readiness for change, and assist in partnering patient’s goals with organizational resources. Area II: 2.3.1, 2.3.3 through 2.3.7 The HES uses the Whole Health Model as a conceptual framework as the primary educational tool using printed materials and training videos supplied on the OPCC&CT website. Area III: 3.2.1-The HES helps create a healing and relaxing atmosphere in the classroom through use of calm speech, dim lighting, and relaxing sounds/music. Area IV: 4.1.9 The HES assists in using the PHI and the 12-question report card for data collection. 4.4.4 through 4.4.8. The HES collects data for evaluating the effectiveness of the intervention. 4.5.3, 4.5.4 The HES evaluates collected data each week to improve the next weeks’ meeting. Area V. 5.2.4 The HES along with the provider informs Executive Leadership and Quality Management to educate stakeholders on the value and benefits of the program. Area VI: 6.4.3, 6.5.6 The HES assists in the development of teaching aids to foster learning for the participants. Area VII: 7.3.1, 7.3.2, 7.3.8 The HES uses the Whole Health Circle of Health to meet the patients where they are in a socioecological patient-centered framework. HES facilitators are representatives of the VA, which practices ICARE values (Integrity, Commitment, Advocacy, Respect, Excellence). Area VIII: 8.1.1 through 8.1.6 The HES practices all of the principles of Ethics and Professionalism in accordance with established ethical principles to build patient trust and prove reliability. 8.3.1, 8.3.3, 8.3.4, 8.3.5. The HES takes responsibility for their professional development through workshops, training, and continuous learning opportunities and mentoring new staff.

The HES played a key role in numerous aspects of the Whole Health SMA. First, the HE had a good working knowledge of how the Whole Health model of care is structured and how to assist participants in the WH Pathway, Clinical Care and Well-being aspects of the program. Second, the HES served initially as the WH SMA facilitator. The HES participated in coaching. The HESs, using motivational interviewing and shared goal setting with participants were able to assist participants in setting SMART goals that led to meaningful life-changes and improved well-being.

Among the many important clinical outcomes of the WH SMA, one was improved staff development. During the SMA, we sent three nurses to the VA-sponsored Whole Health training program, two of whom were part of our regular PACT. This training has been instrumental not only within the SMA but in daily clinical practice and one-on-one patient encounters. The tools used by the HESs are used every day in helping patients identify “what matters most” and facilitating formation of shared health goals. These skills have been useful for helping patients manage other chronic diseases such as hypertension and diabetes. One of our LPN HESs has been promoted within the organization as Whole Health Coach for the Birmingham VA HCS and has been instrumental for bringing Whole Health to Veterans during the COVID-19 pandemic using primarily virtual Whole Health visits.

The NCHEC Website was queried on 3/27/23.

Acknowledgments

The following individuals made significant contributions to the success of the WH-SMA: Health Coaches/Health Educators/HES Traci Carlisle, LPN, Latonya Johnson, LPN, Victoria Moore, RN, Princess Pippen, RN; Ms. Gail Carter; Kim Chism, RD; Dr. Durinda Warren; Pharmacy-led education (Liz-Marie Avilez-Gonzales, PharmD, Lisa Ambrose, PharmD, Meredith Thompson, PharmD); Mental Health Psychologist, Craig Alexander, Ph.D.; Other SMEs from our VA. A special thanks to WH Peer Support, Veteran Mr. Jerry McClain and Volunteer Movement/Yoga Specialist, Veteran Ms. Deborah Parker who led multiple sessions with mindfulness and chair yoga. The Office of Patient Centered Care & Cultural Transformation’s comprehensive Web site with educational and training materials made this project feasible in primary care.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare. This work was reviewed by the Birmingham VA IRB as non-Research or Quality Improvement.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Hedegaard H, Warner M, Minino AM. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2015. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(273):1–8.

- Silva MJ, Kelly Z. The escalation of the opioid epidemic due to COVID-19 and resulting lessons about treatment alternatives. Am J Manag Care. 2020;26(7):e202–e204. doi:10.37765/ajmc.2020.43386.

- Clark DJ, Schumacher MA. America’s opioid epidemic: supply and demand considerations. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(5):1667–1674. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000002388.

- Wilson N, Kariisa M, Seth P, Smith H, Davis NL. Drug and opioid-involved overdose deaths - United States, 2017-2018. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(11):290–297. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6911a4.

- Dart RC, Surratt HL, Cicero TJ, et al. Trends in opioid analgesic abuse and mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(3):241–248. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa1406143.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2018 Annual surveillance report of drug-related risks and outcomes—United States. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/pubs/2018-cdc-drug-surveillance-report.pdf. Published 2018. Accessed 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Opioid overdose-understanding the epidemic. https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html. Published 2017. Accessed 2022.

- National Institute on Drug Abuse. Overdose death rates. http://www.drugabuse.gov/related-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates. Published 2019. Accessed 2022.

- Chisholm-Burns MA, Spivey CA, Sherwin E, Wheeler J, Hohmeier K. The opioid crisis: origins, trends, policies, and the roles of pharmacists. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019;76(7):424–435. doi:10.1093/ajhp/zxy089.

- Schiller EY, Goyal A, Mechanic OJ. Opioid overdose. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470415/. Accessed 2022.

- Salsitz EA. Chronic pain, chronic opioid addiction: a complex nexus. J Med Toxicol. 2016;12(1):54–57. doi:10.1007/s13181-015-0521-9.

- Hagemeier NE. Introduction to the opioid epidemic: the economic burden on the healthcare system and impact on quality of life. Am J Manag Care. 2018;24:S200–S206.

- Kolodny A, Courtwright DT, Hwang CS, et al. The prescription opioid and heroin crisis: a public health approach to an epidemic of addiction. Annu Rev Public Health. 2015;36(1):559–574. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031914-122957.

- Bennett AS, Guarino H, Britton PC, et al. U.S. military veterans and the opioid overdose crisis: a review of risk factors and prevention efforts. Ann Med. 2022;54(1):1826–1838. doi:10.1080/07853890.2022.2092896.

- Gellad WF, Good CB, Shulkin DJ. Addressing the opioid epidemic in the United States: lessons from the department of veterans affairs. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(5):611–612. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0147.

- Manhapra A, Becker WC. Pain and addiction: an integrative therapeutic approach. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(4):745–763. doi:10.1016/j.mcna.2018.02.013.

- Lin LA, Bohnert ASB, Kerns RD, Clay MA, Ganoczy D, Ilgen MA. Impact of the opioid safety initiative on opioid-related prescribing in veterans. Pain. 2017;158(5):833–839. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000837.

- Kahn LS, Wozniak M, Vest BM, Moore C. “Narcan encounters:” overdose and naloxone rescue experiences among people who use opioids. Subst Abus. 2022;43(1):113–126. doi:10.1080/08897077.2020.1748165.

- Strombotne KL, Legler A, Minegishi T, et al. Effect of a predictive analytics-targeted program in patients on opioids: a stepped-wedge cluster randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(2):375–381. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07617-y.

- Minegishi T, Garrido MM, Lewis ET, et al. Randomized policy evaluation of the veterans health administration stratification tool for opioid risk mitigation (STORM). J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(14):3746–3750. doi:10.1007/s11606-022-07622-1.

- Becker WC, DeBar LL, Heapy AA, et al. A research agenda for advancing non-pharmacological management of chronic musculoskeletal pain: findings from a VHA state-of-the-art conference. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(Suppl 1):11–15. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4345-6.

- Edmond SN, Becker WC, Driscoll MA, et al. Use of non-pharmacological pain treatment modalities among veterans with chronic pain: results from a cross-sectional survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(Suppl 1):54–60. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4322-0.

- Elwy AR, Johnston JM, Bormann JE, Hull A, Taylor SL. A systematic scoping review of complementary and alternative medicine mind and body practices to improve the health of veterans and military personnel. Med Care. 2014;52(12 Suppl 5):S70–82. doi:10.1097/MLR.0000000000000228.

- Garland EL, Brintz CE, Hanley AW, et al. Mind-body therapies for opioid-treated pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):91–105. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4917.

- Kligler B, Bair MJ, Banerjea R, et al. Clinical policy recommendations from the VHA state-of-the-art conference on non-pharmacological approaches to chronic musculoskeletal pain. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(Suppl 1):16–23. doi:10.1007/s11606-018-4323-z.

- Kligler B, Niemtzow RC, Drake DF, et al. The current state of integrative medicine within the U.S. department of veterans affairs. Med Acupunct. 2018;30(5):230–234. doi:10.1089/acu.2018.29087-rtl.

- Vaughn IA, Beyth R, Ayers ML, et al. Multispecialty opioid risk reduction program targeting chronic pain and addiction management in veterans. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):406–411.

- Carroll AJ, Howrey HL, Payvar S, Deshida-Such K, Kansal M, Brar CK. A heart failure management program using shared medical appointments. Fed Pract. 2017;34:14–19.

- Drake C, Meade C, Hull SK, Price A, Snyderman R. Integration of personalized health planning and shared medical appointments for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. South Med J. 2018;111(11):674–682. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000892.

- Edelman D, Gierisch JM, McDuffie JR, Oddone E, Williams JW Jr. Shared medical appointments for patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 2015 Jan;30(1):99–106. doi:10.1007/s11606-014-2978-7.

- Heisler M, Burgess J, Cass J, et al. Evaluating the effectiveness of diabetes shared medical appointments (SMAs) as implemented in five veterans affairs health systems: a multi-site cluster randomized pragmatic trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2021;36(6):1648–1655. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06570-y.

- Kirsh S, Watts S, Pascuzzi K, et al. Shared medical appointments based on the chronic care model: a quality improvement project to address the challenges of patients with diabetes with high cardiovascular risk. Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(5):349–353. doi:10.1136/qshc.2006.019158.

- Omogbai T, Milner KA. Implementation and evaluation of shared medical appointments in veterans with diabetes: a quality improvement study. J Nurs Adm. 2018;48(3):154–159. doi:10.1097/NNA.0000000000000590.

- Romanelli RJ, Dolginsky M, Byakina Y, Bronstein D, Wilson S. A shared medical appointment on the benefits and risks of opioids is associated with improved patient confidence in managing chronic pain. J Patient Exp. 2017;4(3):144–151. doi:10.1177/2374373517706837.

- Purcell N, Zamora K, Bertenthal D, Abadjian L, Tighe J, Seal KH. How VA whole health coaching can impact veterans’ health and quality of life: a mixed-methods pilot program evaluation. Glob Adv Health Med. 2021;10:2164956121998283. doi:10.1177/2164956121998283.

- Simmons LA, Drake CD, Gaudet TW, Snyderman R. Personalized health planning in primary care settings. Fed Pract. 2016;33:27–34.

- Seal KH, Becker WC, Murphy JL, et al. Whole health options and pain education (wHOPE): a pragmatic trial comparing whole health team vs primary care group education to promote nonpharmacological strategies to improve pain, functioning, and quality of life in veterans-rationale, methods, and implementation. Pain Med. 2020;21(Suppl 2):S91–S99. doi:10.1093/pm/pnaa366.

- Griesemer I, Vu MB, Callahan LF, et al. Developing a primary care-focused intervention to engage patients with osteoarthritis in physical activity: a stakeholder engagement qualitative study. Health Promot Pract. 2022;23(1):64–73. doi:10.1177/1524839920947690.

- Reddy KP, Schult TM, Whitehead AM, Bokhour BG. Veterans health administration’s whole health system of care: supporting the health, well-being, and resiliency of employees. Glob Adv Health Med. 2021;10:21649561211022698. doi:10.1177/21649561211022698.

- Borsari B, Li Y, Tighe J, et al. A pilot trial of collaborative care with motivational interviewing to reduce opioid risk and improve chronic pain management. Addiction. 2021 Sep;116(9):2387–2397. doi:10.1111/add.15401.

- Seal KH, Rife T, Li Y, Gibson C, Tighe J. Opioid reduction and risk mitigation in VA primary care: outcomes from the integrated pain team initiative. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(4):1238–1244. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05572-9.

- Bokhour BG, Hyde J, Kligler B, et al. From patient outcomes to system change: evaluating the impact of VHA’s implementation of the whole health system of care. Health Serv Res. 2022;57(Suppl 1):53–65. doi:10.1111/1475-6773.13938.

- Case AA, Kullgren J, Anwar S, Pedraza S, Davis MP. Treating chronic pain with buprenorphine- the practical guide. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2021;22(12):116. doi:10.1007/s11864-021-00910-8.

- Rudolf GD. Buprenorphine in the treatment of chronic pain. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2020;31(2):195–204. doi:10.1016/j.pmr.2020.02.001.

- Webster L, Gudin J, Raffa RB, et al. Understanding buprenorphine for use in chronic pain: expert opinion. Pain Med. 2020;21(4):714–723. doi:10.1093/pm/pnz356.

- Goodman MW, Guck TP, Teply RM. Dialing back opioids for chronic pain one conversation at a time. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:753–757.

- Baron MJ, McDonald PW. Significant pain reduction in chronic pain patients after detoxification from high-dose opioids. J Opioid Manag. 2006;2(5):277–282. doi:10.5055/jom.2006.0041.

- National Commission for Health Education Credentialing. Responsibilities & competencies. https://www.nchec.org/. Published 2019. Accessed 2023.