ABSTRACT

How did COVID-19 related movement restrictions impact sentiment toward refugees? Existing theories offer conflicting answers. On the one hand, contact theories suggest that movement restrictions might reduce casual interactions with refugees, leading to less negative sentiments. On the other hand, integrated threat theories suggest refugees may be perceived as a security threat and blamed for these movement restrictions in the first place. To gauge the effect of movement restrictions, we investigate the effect of physical isolation on sentiments toward refugees in Turkey by using a novel dataset. We use Google Mobility Reports’ measurements of movement and our measures of sentiments toward refugees using refugee-related tweets from Turkey. Statistical analysis shows that xenophobic sentiment generally decreased during the pandemic. Our study shows that different types of reduced mobility correlate with increased sympathy toward refugees: the more people stay at home, the more positive sentiments toward refugees they exhibit on Twitter. We conclude by proposing two possible causal mechanisms for these findings. The findings suggest that the absence of casual contact with refugees may yield less negative sentiment, and/or that a rally around the flag mechanism yields unprecedented levels of social solidarity in response to the pandemic.

Introduction

How did COVID-19 related movement restrictions impact sentiment toward refugees? There is no consensus in the extant literature on the potential impact of pandemic-related measures on sentiment toward refugees. In this piece, we aim to help fill this gap by examining the effect of movement restrictions on attitudes toward Syrian refugees on the Turkish social media landscape. In doing so, we aim to contribute to the theoretical literature on anti-refugee sentiment across various disciplines.

There are two potential explanations. On the one hand, the contact theory postulates that meaningful and sustained contact between communities is required for cultivating sympathy toward each other as a strategy to curb xenophobia and discrimination, instead of casual interactions (Çirakoğlu, Demirutku, & Karakaya, Citation2021). If that is the case, then mobility restrictions that came with the pandemic might have reduced these casual interactions between host and refugee communities, leading to less negative sentiments. The pandemic may also have reduced the visibility and saliency of vulnerable groups through mobility restrictions, which would contribute to lessening negative sentiments toward them. On the other hand, many scholars and pundits expressed concerns that refugees would be blamed for the pandemic and social isolation (Kluge, Jakab, Bartovic, D’anna, & Severoni, Citation2020, 1239). To address these potential explanations and examine the effect of movement restrictions on sentiments toward refugees, we focus on Turkey as our case study.

As a high-refugee-per-capita country, Turkey constitutes a typical case to study discrimination against refugees (Erdoğan & Uyan Semerci, Citation2018; Erdoğdu, Citation2018; Girgin & Turna Cebeci, Citation2017; Secen, Citation2021; Çirakoğlu, Demirutku, & Karakaya, Citation2021). Over the last few years, Turkish host communities’ negative sentiments toward refugees have increased – the level of anxiety due to the refugee crisis is on average around 3.6 out of a 5-point metric among the Turkish population, and economic anxiety ranks the top (Erdogan, Citation2020, p. 82). The material and psychological stress (Dushime & Hashemipour, Citation2020, p. 83) of movement restrictions complicated an already fragile situation brought about by the devaluation of the Turkish lira in 2019 and long-term simmering anti-refugee sentiments, as the COVID-19 crisis has led to job losses and employment vulnerability (Şeker, Sırma, & Acar Erdoğan, Citation2020).

We use a novel dataset to examine the impact of movement restrictions on sentiments toward refugees. First, we use six measures of movement in Turkey during the COVID-19 pandemic made available through the Google Mobility Report. We measure feelings toward refugees using 7,988 refugee-related tweets collected between February 15 and August 31, 2020. The descriptive analysis shows that xenophobic sentiment in Turkey decreased somewhat during the pandemic (March 2020 onward compared to February 2020). To explain this decrease, we use statistical tests aggregated at the country and region levels and show that four types of decreased mobility correlate with increased sympathy toward refugees. In sum, the more people stay at home, the less they use transit stations, the less they go to work, and the less they go to retail and recreation areas, the more likely it is that positive sentiment will be displayed toward refugees that day on Twitter.

This paper is organized as follows: First, we offer a theoretical framework for the relationship between mobility restrictions and prejudicial behavior against refugees, followed by a series of statistical tests to probe the impact of mobility restrictions. Then we conclude by identifying several potential causal mechanisms to explain our findings.

Theoretical framework

There are two broad theoretical frameworks that aim to explain anti-refugee sentiment with different observable implications: contact and group threat theories (see Jens & Hopkins, Citation2014; Paluck & Green, Citation2009). These theories’ explanatory power has not been fully tested in the context of extraordinary conditions around the COVID pandemic (see also Appendix 9).

A new wave of scholarly work has recently emerged that assesses the explanatory power of contact theories in terms of negative attitudes toward marginalized/disadvantaged communities (de Coninck, Ogan, & D’haenens, Citation2021, p. 232; Hangartner, Dinas, Marbach, Matakos, & Xefteris, Citation2019, p. 443; Kanas, Scheepers, & Sterkens, Citation2015, p. 105). The main premise of the contact theory is that sustained interactions—defined as friendships, equal status interactions, and intimate relationships – reinforce tolerance between groups while casual interactions, i.e. unequal status interactions and random encounters at work or in transit, reinforce stereotypes, negativity, and the rejection of out-group members (Kenworthy, Turner, Hewstone, & Voci, Citation2008; Weber, Citation2019; Çirakoğlu, Demirutku, & Karakaya, Citation2021, 2987;). COVID-19 and its restrictions on movement may have decreased the latter due to stay-home orders and limited contact with other households. At the same time, it is reasonable to expect that sustained interactions could be maintained through social media and cellphone use, given that both increased substantially during the COVID-19-related lockdown orders around the world (Koeze & Popper, Citation2020; Pérez-Escoda, Jiménez-Narros, Perlado-Lamo-de-Espinosa, & Miguel Pedrero-Esteban, Citation2020). Such a mechanism would logically serve to decrease negativity toward refugees. In addition, as casual interactions phase out, the visibility and saliency of the “refugee problem” may decline (see Menshikova & van Tubergen, Citation2022), which would alleviate the overall negative sentiment toward refugees.

In contrast, refugees may also be scapegoated for movement restrictions. The literature documents many cases in which refugees are stigmatized as security threats and tagged as “disease carriers,” such as in Thailand with the Myanmar refugee crisis (Sunpuwan & Niyomsilpa, Citation2012) or the USA during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1919 (Kraut, Citation2010). On numerous occasions in the context of disasters, refugees and asylum seekers are described as a health risk; as violent, fringe populations; or as terrorists (Dempster & Hargrave, Citation2017, p. 10; Yigit & Tatch, Citation2017). Negative coverage on media through depictions such as bogus refugee claimants or villains may exacerbate this perceived group threat (Crawley, Mcmahon, & Jones, Citation2016; Esses, Medianu, & Lawson, Citation2013; Louis, Esses, & Lalonde, Citation2013, p. 161; Schlueter & Davidov, Citation2013). Political parties may also leverage this politically charged topic to harness popular support. In countries like Turkey, views of refugees are colinear with current political party affiliations (Erdoğan & Uyan Semerci, Citation2018). This division emerges because the refugee issue has become a constitutive component of many political parties’ discourses and campaigns (Polat, Citation2018; Secen, Citation2021, p. 16).

Therefore, there is no consensus in the extant literature on the potential impact of pandemic-related measures on sentiments toward refugees. Our research aims to help fill this gap by examining the effect of movement restrictions on attitudes toward Syrian refugees voiced on the Turkish social media landscape.

Data

We use two data sources to explore the impact of COVID-19 movement restrictions on attitudes toward refugees in Turkey: social media data and Google Mobility reports.

There are three main reasons why select Turkey for a case study. First, Turkey constitutes a typical case for examining anti-refugee sentiment because it is a high-refugee-per-capita country – Turkey has been the largest refugee hosting country in the world for the past eight years (UNHCR, Citationn.d..). There has also been a substantial growth of anti-refugee sentiment in recent years – according to a recent survey conducted by the UNHCR, compared to three years ago, the percentage of Turkish citizens who believe that Syrian refugees should be sent back to Turkey has tripled (Tahiroglu, Citation2022). Second, the internet penetration rate in Turkey is quite high: 82%, which justifies the use of social media data for such analysis (DataReportal, Citation2022). Third, the Turkish government imposed a variety of mobility restrictions throughout the pandemic, at different levels, for various groups of people in various locations, and acrossdifferent time periods. Such variation offers us a leverage to analyze their impact on sentiment toward refugees.

Twitter posts

First, we analyze Twitter posts about refugees in Turkey to assess public sentiment toward refugees. To the best of our knowledge, this paper is one of the first to leverage Twitter posts to systematically study interactions between refugees and host communities in Turkey for generalizable inference. Even though qualitative analysis of specific racist hashtags or collection of tweets generated some insights into the patterns of xenophobia in Turkey (Bozdağ, Citation2019; Erdogan-Ozturk & Isik-Guler, Citation2020; Ozduzen, Korkut, & Ozduzen, Citation2020), most qualitative studies of Twitter sentiment toward refugees in Turkey select on the dependent variable. Hatipoglu, Zeki Gokce, Arin, and Saygin (Citation2018, p. 7) suggest that such studies tend to choose small-N tweets to demonstrate their arguments, which fails to adequately capture the ratio of positive to negative tweets. The quantitative scholarship’s external validity and theoretical generalizability also remain limited (Adam-Troian & Cigdem Bagci, Citation2021; Frydenlund et al., Citation2019; Öztürk & Ayvaz, Citation2018). One such constraint is the scarce geo-location information of tweets (Frydenlund et al., Citation2019, p. 421).

We circumvent this problem by using data collected by the Natural Language Processing crisis branch of the Qatar Computing Institute for the entire world during the COVID-19 pandemic. This data is collected using an algorithm that helps geolocate tweets using either the text’s content, the tweeter’s GPS coordinates, or the geo-location registered by the user account (Qazi, Imran, & Ofli, Citation2020). This approach generates a more representative sample of tweets in Turkey and allows us to circumvent virtual private networks (VPNs) by some Twitter users. This data is collected in a way that encompasses three rather conventional geo-location methods, which expands access to geotagged tweets much more than the 1–3% of tweets containing geolocated information. Thus, tweets are geolocated not only by geotags but also by location: the profile is registered, and a geo-location inference approach is used that infers the location from the tweet’s content – for instance, mentions that the user is currently located in a specific place in Turkey (Qazi, Imran, & Ofli, Citation2020). Therefore, our paper offers an essential contribution to the use of social media data for inference in terms of the study of attitudes toward refugees.

The tweets in the sample were collected from February 1, 2020, to August 31, 2020. The reasons why we decided to focus on this timeline are that, first, the first case of COVID was identified on March 11th, and the mobility restrictions were imposed the following month. Our final dataset offers a very holistic way of determining the location of Twitter users despite the use of VPNs or non-geotagged tweets, thus substantially expanding the sample. We also filter for tweets that pertain to refugees. Therefore, while our selection is much more tightly focused on tweets that discuss refugees and includes far fewer false positives, our approach generates a smaller sample of geocoded tweets – roughly 6,766 in Turkish and 1,300 in English.

We use the VADER algorithm on both English- and Turkish-language tweets to measure their sentiment about refugees in Turkey during the pandemic. Sentiment for the Turkish-language posts is computed by machine translating the posts into English first and then using the VADER algorithm. This last step is critical: many previous studies show that machine translations maintain sentiment and optimize measured values thanks to robust English-language sentiment algorithms compared to the algorithms developed in other languages, like Turkish (Mohammad, Salameh, & Kiritchenko, Citation2016; Refaee & Rieser, Citation2015; Balahur, Fondazione, and Kessler Citation2013).

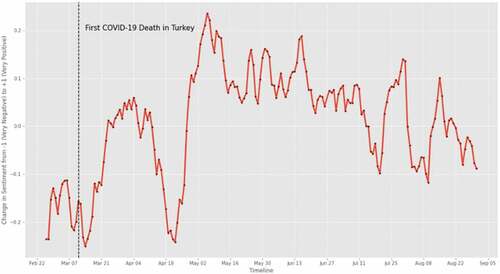

shows the daily evolution of average sentiment voiced toward refugees in Turkey during the study period. To smooth the daily fluctuation of sentiment, we use a 10-day moving average. Overall, the figure shows that sympathy toward refugees increased during the pandemic. It indicates rather considerable spikes in positivity after the pandemic was declared in Turkey in mid-March and a substantial shift from largely negative values before May 2020 to largely positive values between May and July 2020. The overall sympathy toward refugees has somewhat increased during the pandemic.

Google mobility report

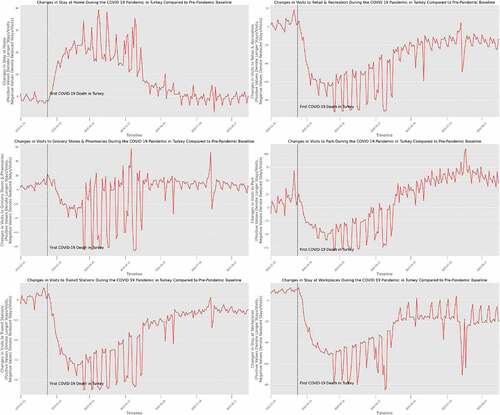

We use the Google data to operationalize our main independent variables. The data measure percentage changes in visits and lengths of stay compared to a pre-pandemic baseline computed from the median value for the corresponding day of the week (Google, Citationn.d..). The mobility data represents variations in mobility for five categories of places that people may visit – Grocery & Pharmacy, Parks, Transit Stations, Retail & Recreation, Residential, and Workplaces (see the Appendix for the list). These changes are calculated at the national, provincial, and district levels. Mobility data is measured based on Google users who have a smartphone device, on which they are signed into a Google account, and where location reporting is turned on.

shows daily national-level changes in mobility in Turkey compared to a baseline for each of the six variables computed out of the median length of stay/visits to each of the six destinations. In the long term, trends show that stay-home behavior levels off from being almost lower than the baseline to reach very high levels in a matter of days. Lengthier stays at home start to decrease in frequency in May and steadily reduce throughout June 2020, returning to a value close to the baseline (or lower) beginning in July 2020. In the following section, we explore the correlation between variation in the Google Mobility Report and sentiments voiced toward refugees on Twitter to test the general intuition of contact theories and integrated threat theories.

Research design

We estimate a range of linear models that account for the multilevel and time features of the data. Sentiment toward Syrian refugees is computed at the individual level, while our main independent variables – changes in stay/visit to specific areas and places – are measured at the national and regional levels. To address the multilevel nature of our data, we compute multilevel linear models for mobility changes at the national and regional levels. We include random intercepts for time and user IDs because mobility changes compared to the pre-pandemic baseline are averaged once per day at the national and regional levels. Adding random effects both for time and user IDs also allows us to account for the number of tweets about refugees per user ID and the number of positive/negative tweets per day. Therefore, our model accounts for the relative difference in the number of positive and negative tweets before and during the pandemic (see Appendix for details on model specifications).

Estimation results

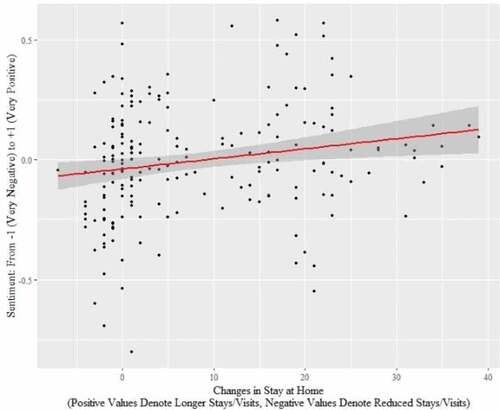

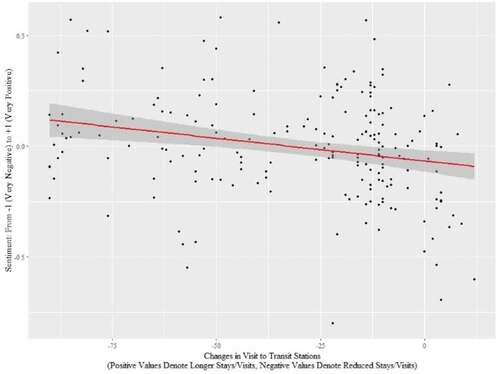

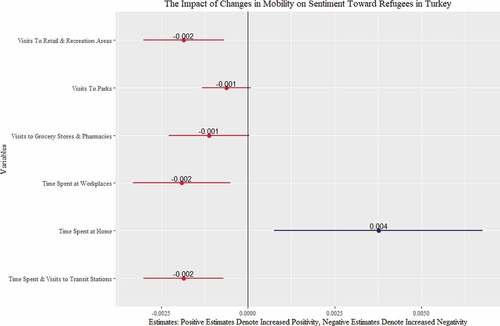

presents the main coefficients of the effect of the COVID-19 restrictions on movement on sentiment toward refugees voiced on Twitter in Turkey.

Figure 3. The Impact of Changes in Mobility During the COVID-19 Pandemic on Sentiment Voiced Toward Refugees on Twitter.

The results for “time spent at home” suggest that COVID-19‘s restrictions on movement increased positive sentiment toward refugees in Turkey. The other estimates also support the idea that COVID-19 restrictions on movement increased positivity toward refugees in Turkey. Visits to transit stations and length of stay at workplaces have statistically significant negative impact on sentiment toward refugees. However, the effects of increased visits to parks, and to grocery stores and pharmacies are statistically insignificant.

To illustrate the impact of mobility changes on sentiment toward refugees, plot the impact of changes in stay at home and changes in visits to transit stations with national-level residuals. shows that lengthier stays at home yielded a change from negative to positive sentiments voiced on average on Twitter, even after controlling for many features of individual Twitter users. corroborates these results. It exhibits a steady rise in negative values as people visit transit stations (subways, buses, and tramway stations) across Turkey, where it is reasonable to assume that Turks are very likely to casually encounter refugees. In the next section, we discuss the theoretical implications of our findings.

Discussion

This paper focuses on a potential driver of sentiment toward refugees during the COVID-19 pandemic by exploring whether physical isolation plays a substantive role in driving xenophobia. To do so, we explored the impact of movement restrictions on sentiment toward refugees in a high-refugee-per-capita country – Turkey. We empirically tested the effect of the restrictions on movement using six mobility measures from the Google mobility reports on views toward refugees measured with tweets about refugees posted in the country. We find support for the idea that the limits on movement contributed to increasing sympathy for refugees. To sum it up, when refugees are out of sight, they are also out of mind.

We reckon that there may be two potential, theoretical mechanisms at play. The first fits the contact theory of anti-refugee sentiment – when mobility is restricted, casual interactions decrease, while sustained interactions survive through social media. As a result of being stuck at home, individuals who encounter refugees casually in the city may not see them anymore – and therefore do not post negative comments about them online. However, those who typically interact with refugees as friends and close acquaintances keep doing so through social media and phone use during the restrictions on movement. It is possible that mobility “in general” is aligned with negative attitudes toward refugees and its absence during the lockdowns does not necessarily mean that becoming homebound during a lockdown increases one’s positive sentiments toward refugees. Even though variation in our mobility data is measured against a pre-pandemic mobility baseline, it remains impossible to fully distinguish between these two different scenarios in the empirical tests. Ultimately, both still fit with the mechanism of the contact theory. It is also plausible that refugee-related issues have become less salient during the pandemic. However, an analysis of the frequencies of tweets indicates that negative sentiment still goes down during mobility restrictions while positive sentiment goes up too, or remains the same (see Figure S6.1 and S6.2 in the Appendix).

Second, sympathy may increase when mobility is restricted due to the kind of widespread societal solidarity that emerges in response to disasters (Pierskalla & Roth, Citation2020). The widespread shock of being vulnerable to the pandemic during movement restrictions could increase sympathy for – rather than animosity toward – out-groups. Such a scenario would be like experiences of natural disasters, in which outgroups are not blamed for the security threat. Instead, such disasters and hardships may generate intergroup solidarity, interpersonal trust, and social capital through shared experience of suffering (Ahmad & Zeeshan Younas, Citation2021; Lee, Citation2020; Pierskalla & Roth, Citation2020). This mechanism has been documented by many scientific studies of post-disaster situations around the world, where natural catastrophes have helped end conflicts between various social groups and/or increased sympathy toward disliked groups(P. L. Billon & Waizenegger, Citation2007; Pierskalla & Roth, Citation2020). In this scenario, Turks feel vulnerable and bond with each other and refugees to face the pandemic together – several supportive hashtags trend during our timeline. For instance, several tweets with the #Suriyeli hashtag express support for Syrian doctors risking their lives helping Turkey fight the coronavirus pandemic. Several tweets also mention feelings of vulnerability for the plight of Syrian refugees in Turkey. For instance, some tweets point to the folk tale of a mistreated Syrian refugee child who promised to “complain to God” about the Turkish people upon his death. Future work will benefit from disentangling the intricate link that exists between the two proposed mechanisms.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (2 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/19331681.2023.2183301

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adam-Troian, J., & Cigdem Bagci, S. (2021). The pathogen paradox: Evidence that perceived COVID-19 threat is associated with both pro- and anti-immigrant attitudes. International Review of Social Psychology, 34(1), 1–15. doi:10.5334/irsp.469

- Ahmad, N., & Zeeshan Younas, M. (2021). A blessing in disguise?: Assessing the impact of 2010–2011 floods on trust in Pakistan. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 28:20 28(20), 25419–25431. doi:10.1007/s11356-020-12332-4

- Balahur, A., Turchi Fondazione, M., & Kessler, B. (2013). Improving sentiment analysis in twitter using multilingual machine translated data. Proceedings of Recent Advances in Natural Language Processing, 7–13.

- Billon, P. L., & Waizenegger, A. (2007). Peace in the wake of disaster? Secessionist conflicts and the 2004 Indian Ocean Tsunami. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 32(3), 411–427. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2007.00257.x

- Bozdağ, Ç. (2019). Bottom-up nationalism and discrimination on social media: An analysis of the citizenship debate about refugees in Turkey. European Journal of Cultural Studies, 23(5), 712–730. doi:10.1177/1367549419869354

- Çirakoğlu, O. C., Demirutku, K., & Karakaya, O. (2021). The mediating role of perceived threat in the relationship between casual contact and attitudes towards Syrian Refugees in Turkey. Journal of Refugee Studies, 34(3), 2984–2999. doi:10.1093/jrs/fez118

- Coninck, D. D., Ogan, C., & D’haenens, L. (2021). Can ‘the other’ Ever become ‘one of us’? Comparing Turkish and European attitudes toward Refugees: A five-country study. International Communication Gazette, 83(3), 217–237. doi:10.1177/1748048519895376

- Crawley, H., Mcmahon, S., & Jones, K. (2016). Victims and Villains: Migrant voices in the British Media. Coventry: Centre for Trust, Peace and Social Relations, Coventry University.

- DataReportal. (2022). Digital 2022: Turkey. DataReportal – Global Digital Insights, February 15, 2022 https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-turkey

- Dempster, H., & Hargrave, K. (2017). Understanding public attitudes towards refugees and Migrants. London: Chatham House & ODI Forum on Refugee and Migration Policy Initiative.

- Dushime, C. E., & Hashemipour, S. (2020). The psychological effect of the COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey and the world at the context of political psychology. Eurasian Journal of Researches in Social and Economics, 7(6), 75–86.

- Erdogan, M. (2020). Syrians Barometer 2019: A framework for achieving social cohesion with Syrians in Turkey. Ankara: Orion Kitabevi.

- Erdogan-Ozturk, Y., & Isik-Guler, H. (2020). Discourses of exclusion on Twitter in the Turkish context: #ülkemdesuriyeliistemiyorum (#idontwantsyriansinmycountry). Discourse, Context & Media, 36(August), 100400. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2020.100400

- Erdoğan, E., & Uyan Semerci, P. (2018). Turkish perceptions of Syrian refugees-2017. Ankara: German Marshall Fund Discussion on Turkish Perceptions of Syrian Refugees.

- Erdoğdu, S. (2018). Syrian refugees in Turkey and trade union responses. Globalizations, 15(6), 838–853. doi:10.1080/14747731.2018.1474038

- Esses, V. M., Medianu, S., & Lawson, A. S. (2013). Uncertainty, threat, and the role of the media in promoting the dehumanization of immigrants and refugees. The Journal of Social Issues, 69(3), 518–536. doi:10.1111/josi.12027

- Frydenlund, E., Yilmaz Sener, M., Gore, R., Christine Boshuijzen-Van, B., Bozdag, E., & De Kock, C. (2019). Characterizing the mobile phone use patterns of refugee-hosting provinces in Turkey. In A. A. Salah, A. Pentland, B. Lepri, & E. Letouzé (Eds.), Guide to mobile data analytics in refugee scenarios (pp. 417–431). New York: Springer.

- Girgin, S. Z. S., & Turna Cebeci, G. (2017). The effects of an immigration policy on the economic integration of migrants and on natives’ attitudes: The case of Syrian Refugees in Turkey. International Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 11(4), 1065–1071.

- Google. n.d. “COVID-19 community mobility reports.” Accessed November 11, 2020. https://www.google.com/covid19/mobility/.

- Hangartner, D., Dinas, E., Marbach, M., Matakos, K., & Xefteris, D. (2019). Does exposure to the refugee crisis make natives more hostile? The American Political Science Review, 113(2), 442–455. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000813

- Hatipoglu, E., Zeki Gokce, O., Arin, I., & Saygin, Y. (2018). Automated text analysis and international relations: The introduction and application of a novel technique for Twitter. All Azimuth, 1–22. doi:10.20991/allazimuth.476852

- Jens, H., & Hopkins, D. J. (2014). Public attitudes toward immigration. Annual Review of Political Science, 17(1), 225–249. doi:10.1146/annurev-polisci-102512-194818

- Kanas, A., Scheepers, P., & Sterkens, C. (2015). Interreligious contact, perceived group threat, and perceived discrimination: Predicting negative attitudes among religious minorities and Majorities in Indonesia. Social Psychology Quarterly, 78(2), 102–126. doi:10.1177/0190272514564790

- Kenworthy, J. B., Turner, R. N., Hewstone, M., & Voci, A. (2008). Intergroup contact: When does it work, and why? In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick, & L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice: Fifty years after allport (pp. 278–292). Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Kluge, H. H. P., Jakab, Z., Bartovic, J., D’anna, V., & Severoni, S. (2020). Refugee and migrant health in the COVID-19 response. The Lancet, 395(10232), 1237–1239. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30791-1

- Koeze, E., & Popper, N. 2020. “The virus changed the way we internet.” The New York Times, April 7, 2020.

- Kraut, A. M. (2010). Immigration, ethnicity, and the pandemic. Public Health Reports, 125(3), 123–133. doi:10.1177/00333549101250S315

- Lee, J. (2020). Post-disaster trust in Japan: The social impact of the experiences and perceived risks of natural hazards. Environmental Hazards, 19(2), 171–186. doi:10.1080/17477891.2019.1664380

- Louis, W. R., Esses, V. M., & Lalonde, R. N. (2013). National identification, perceived threat, and dehumanization as antecedents of negative attitudes toward immigrants in Australia and Canada. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 43(SUPPL.2), E156–65. doi:10.1111/jasp.12044

- Menshikova, A., & van Tubergen, F. (2022). What drives anti-immigrant sentiments online? A novel approach using Twitter. European Sociological Review, 38(5), 694–706. doi:10.1093/esr/jcac006

- Mohammad, S. M., Salameh, M., & Kiritchenko, S. (2016). How translation alters sentiment. The Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research, 55(January), 95–130. doi:10.1613/jair.4787

- Ozduzen, O., Korkut, U., & Ozduzen, C. (2020). ‘Refugees are not welcome’: Digital Racism, online place-making and the evolving categorization of Syrians in Turkey. New Media & Society, 23(11), 3349–3369. doi:10.1177/1461444820956341

- Öztürk, N., & Ayvaz, S. (2018). Sentiment analysis on Twitter: A text mining approach to the Syrian Refugee Crisis. Telematics and Informatics, 35(1), 136–147. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2017.10.006

- Paluck, E. L., & Green, D. P. (2009). Prejudice reduction: What Works? A review and assessment of research and practice. Annual Review of Psychology, 60(1), 339–367. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163607

- Pérez-Escoda, A., Jiménez-Narros, C., Perlado-Lamo-de-Espinosa, M., & Miguel Pedrero-Esteban, L. (2020). Social networks’ engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic in Spain: Health media vs. Healthcare professionals. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5261. doi:10.3390/ijerph17145261

- Pierskalla, J., & Roth, B. 2020. COVID-19 and conflict: A literature review. Ohio

- Polat, R. K. (2018). Religious solidarity, historical mission and moral superiority: Construction of external and internal ‘others’ in AKP’s discourses on Syrian refugees in Turkey. Critical Discourse Studies, 15(5), 500–516. doi:10.1080/17405904.2018.1500925

- Qazi, U., Imran, M., & Ofli, F. (2020). GeoCoV19: A dataset of hundreds of millions of multilingual COVID-19 tweets with location information. SIGSPATIAL Special, 12(1), 6–15. doi:10.1145/3404820.3404823

- Refaee, E., & Rieser, V. 2015. “Benchmarking machine translated sentiment analysis for Arabic tweets.” Proceedings of NAACL-HLT 2015 Student Research Workshop, Denver, Colorado, United States, 71–78.

- Schlueter, E., & Davidov, E. (2013). Contextual sources of perceived group threat: Negative immigration-related news reports, immigrant group size and their interaction, Spain 1996–2007. European Sociological Review, 29(2), 179–191. doi:10.1093/esr/jcr054

- Secen, S. (2021). Explaining the politics of security: Syrian refugees in Turkey and Lebanon. Journal of Global Security Studies, 6(3), 39. doi:10.1093/jogss/ogaa039

- Şeker, D., Sırma, E. N. Ö., & Acar Erdoğan, A. (2020). Jobs at risk in Turkey: Identifying the impact of COVID-19. Washington, DC: World Bank Group: Social Protection & Jobs.

- Sunpuwan, M., & Niyomsilpa, S. (2012). Perception and misperception: Thai public opinions on refugees and migrants from Myanmar. Journal of Population and Social Studies, 21(1), 47–58.

- Tahiroglu, M. (2022). Göç Politikaları: Türkiye’deki Mülteciler ve 2023 Seçimleri. Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung (Blog) (Blog), 2022. https://tr.boell.org/tr/2022/09/20/goc-politikalari-turkiyedeki-multeciler-ve-2023-secimleri

- UNHCR. n.d. “Türkiye: Latest updates.” Global Focus. Accessed November 29, 2022. http://reporting.unhcr.org/turkey.

- Weber, H. (2019). Attitudes towards minorities in times of high immigration: A panel study among young adults in Germany. European Sociological Review, 35(2), 239–257. doi:10.1093/esr/jcy050

- Yigit, I. H., & Tatch, A. (2017). Syrian refugees and Americans: Perceptions, attitudes and insights. American Journal of Qualitative Research, 1(1), 13–31. doi:10.29333/ajqr/5789