ABSTRACT

We aimed to identify targets for neuropalliative care interventions in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease by examining characteristics of patients and sources of distress and support among former caregivers. We identified caregivers of decedents with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease from the University of California San Francisco Rapidly Progressive Dementia research database. We purposively recruited 12 caregivers for in-depth interviews and extracted associated patient data. We analysed interviews using the constant comparison method and chart data using descriptive statistics. Patients had a median age of 70 (range: 60–86) years and disease duration of 14.5 months (range 4–41 months). Caregivers were interviewed a median of 22 (range 11–39) months after patient death and had a median age of 59 (range 45–73) years. Three major sources of distress included (1) the unique nature of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease; (2) clinical care issues such as difficult diagnostic process, lack of expertise in sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, gaps in clinical systems, and difficulties with end-of-life care; and (3) caregiving issues, including escalating responsibilities, intensifying stress, declining caregiver well-being, and care needs surpassing resources. Two sources of support were (1) clinical care, including guidance from providers about what to expect and supportive relationships; and (2) caregiving supports, including connection to persons with experience managing Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, instrumental support, and social/emotional support. The challenges and supports described by caregivers align with neuropalliative approaches and can be used to develop interventions to address needs of persons with sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and their caregivers.

Introduction:

Prion diseases such as sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease (sCJD) are rare but devastating in their rapid progression to serious disability, profoundly impacting patients and their family caregivers [Citation1]. sCJD is the most common form of human prion disease, with about 400 cases of sCJD in the USA annually [Citation2]. Prion diseases develop when a cellular protein in the nervous system is misfolded and aggregates. Prion diseases occur through multiple mechanisms – spontaneously (e.g., sCJD); genetically, through autosomal dominant mutations in the prion protein gene (PRNP); and acquired/infectious, such as through exposure to contaminated surgical equipment used previously on a person who unknowingly had CJD. Persons with sCJD and their caregivers experience a high burden of suffering due to the patient’s rapid loss of cognition, coordination, control of motor function and general bodily-function [Citation3]. In about 90% of persons with sCJD, death typically occurs within one year (4.4 to 14 months) of symptom onset [Citation4,Citation5], with a correct and clear diagnosis often coming about 2/3 of the way through the disease course [Citation6]. This leaves persons with sCJD and caregivers little time to prepare for end-of-life care. Given the current lack of disease-altering treatments for sCJD, appropriate care focuses on symptom management and promoting quality of life for both persons with sCJD and their caregivers [Citation7,Citation8].

Neuropalliative care is an emerging subspeciality and an interdisciplinary approach to reducing suffering and improving quality of life for persons with neurological illnesses and caregivers [Citation9,Citation10]. Palliative care approaches include symptom management, emotional and spiritual support, and guidance about treatment decisions. There is international consensus around the importance of palliative care for persons with longer-course dementia syndromes [Citation11]. Little is known, however, about utilizing palliative care to address needs in rapidly progressing dementias (RPDs), with limited literature on palliative care in prion disease [Citation8,Citation12–14]. In sCJD, management is difficult because the rapid decline results in the degree and type of symptoms occurring within a few months of onset that are comparable to advanced stages of other neurodegenerative dementias that progress over many years [Citation7,Citation8,Citation15,Citation16], Caregivers and families typically need help managing distress about treatment decisions, especially those with implications for life-extension (e.g. tube feeding) [Citation8,Citation12,Citation14,Citation17]. We are only aware of one study, by Ford et al. (2018), that has specifically focused on caregivers’ struggles to manage symptoms of persons with sCJD [Citation7].

We aimed to expand on Ford et al.’s work by using a mixed methods study informed by a palliative care framework [Citation18] to comprehensively explore a range of both challenges and sources of support among caregivers of persons who died from sCJD. To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth description of palliative care needs associated with sCJD. Our findings highlight opportunities to add palliative care approaches and tools into regular neurology care for prion disease, and opportunities to improve prion-specific care among palliative care and hospice clinicians. These insights may be applicable to other rare diseases or to longer-course neurodegenerative diseases as well.

Results

Eight of 12 persons who died from sCJD had participated in a 2-day clinical research visit and 4 with limited contact with the RPD study team had been admitted to the UCSF inpatient neurology service (). Median age at first UCSF visit was 70 years old (range 60–86). All patients met UCSF, European 2009, and European 2017 diagnostic criteria for probable sCJD and included of a variety of molecular subtypes [Citation15,Citation19,Citation20]. The median disease duration was 14.5 months (range 4–41); onset to UCSF visit was 8 months (range 1–25); and first UCSF visit to death was 2.5 months (range 0–26), indicating participants were a median of ¾ through their disease course at their visit. Of the 8 research patients, median assessments scores were consistent with moderate to severe dementia and moderate dependence for activities of daily living (ADLs); although less quantitative data was available on the four inpatients, they were typically more impaired (e.g. median time from diagnosis to death was 1 month [range 0–4) for those admitted to inpatient services versus 5 months (range 1–27) for research visit participants).

Table 1. Patient and caregiver characteristics

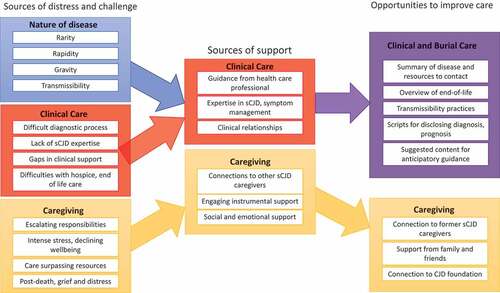

Caregivers were interviewed a median of 22 months (range 11–39) after the death of the patient and had a median age of 59 (range 45–73; ). Three-quarters were the patient’s spouse; half self-identified as female (50%); most had a college degree or post-graduate education (75%). Below we summarize themes within the challenges, supports, and recommendations shared by caregivers (), providing examples in the text as well as in .

Table 2. Sources of challenge and distress related to the nature of sCJD; quotes from interviews with bereaved caregivers (n = 12)

Table 3. Sources of challenge and distress related to clinical care

Table 4. Sources of challenge and distress related to caregiving

Table 5. Sources of support and amelioration related to clinical care

Table 6. Sources of support and amelioration related to caregiving

Figure 1. Summary of findings and implications for intervention targets.

Sources of challenge and distress

We identified 3 major categories of challenges and distress – nature of disease, clinical care, caregiving.

Nature of sCJD

Distinguishing features of sCJD – its rarity, rapidity, potential transmissibility, and gravity – consistently appeared across respondents’ narratives as independent challenges and as compounding factors (). sCJD’s rarity meant caregivers encountered a lack of information, expertise, treatment options, and trials, causing protracted diagnostic journeys and inappropriate care.

Challenges related to the rapidity of the disease included the pace of functional decline: ‘you suddenly find that at every plateau you upgrade your skills to deal with that plateau and when they fall off that plateau with another function going, it is like you’re not expecting it’ (c4). One caregiver described their father using a cane for only 10 days before requiring a walker, and then moving to a wheelchair in two months (c7). Caregivers also described correspondingly rapid changes to family and social systems, such as their need to quickly take on legal and medical decision-making responsibilities (c2).

Challenges related to the gravity of the disease included loss of almost all ADLs, difficult behavioural symptoms (e.g., hallucinations, panic/fear, wandering: ‘all of a sudden she got really hallucinating and being really afraid of things and it just started snowballing from there’ (c6)) and assured fatality.

A few caregivers described challenges related to transmissibility: the potential that prions, the misfolded proteins causing sCJD, could be transmitted to others. Some believed that their loved one was treated differently, or rejected from facilities, because of transmissibility concerns. One caregiver said that a funeral director said: ‘Oh, you have Creutzfeldt, well we’ll come get her but we’re going to direct bury her because we can’t embalm her’ (c6), contrary to the family’s wishes and accepted medical practice [Citation21–23].

Clinical care

Caregivers reported many challenges and sources of distress related to clinical care, clinicians, or health systems (). Almost all experienced extensive challenges in obtaining a diagnosis, often attributed sCJD’s rarity. Caregivers evinced frustration at doctors’ dismissal of early symptoms and at making multiple clinic trips in pursuit of a diagnosis. Clinicians’ ack of sensitivity in disclosing this terminal diagnosis caused distress: ‘it didn’t seem like there was a lot of concern on their end’ (c10). The lack of clear prognostic information to inform planning also was a common problem.

Caregivers conveyed distress at many clinicians’ lack of expertise in sCJD: ‘I don’t think we ever saw anybody [prior to UCSF] … who had any idea about what this disease was or how it progressed or how to deal with someone that had it’ (c10). Caregivers suggested this led to unsuitable care, including inappropriate or harmful medication or care plans ill-suited to an RPD.

Gaps in clinical support were a challenge. Particularly in hospitals or facilities, caregivers felt they needed someone present to help or advocate for the patient: ‘We were there 24/7 because … [staff] probably wouldn’t have come around or known that he wet the bed’ (c2). Caregivers were extremely distressed if clinicians no longer helped them (‘abandoned’ them; c12) after suspected diagnosis or enrolling patients in hospice.

Caregivers described distress at end-of-life care and post-death support. Hospice sometimes delayed enrolment because they did not understand how rapid the decline would be in sCJD. Though predominantly perceived as helpful, as detailed below, hospice care was also insufficient: ‘[The hospice nurse] was really great, but she was spread so thin … and could not come regularly’ (c4). Hospice staff did not always know or learn about sCJD, sometimes misinterpreting symptoms, such as treating myoclonus, pyramidal or extrapyramidal symptoms as pain and managing the patient more like ‘somebody with cancer’ (c7). Challenges did not end upon the patient’s death – delays and administrative hurdles with body handling, funeral home and autopsy arrangements, pathological and genetic results were common issues.

Caregiving

Caregiving challenges spanned the disease course and post-death (). Respondents described difficulty accepting the diagnosis or prognosis of sCJD, which sometimes interfered with fulfiling caregiving or decision-making roles. Caregivers took on new roles as advocates and decision-makers: ‘I found it very difficult having no knowledge of this and trying to get educated on it in a short period of time’ (c5). Caregiving intensified quickly, often involving major lifestyle changes. Several respondents took leaves from work and/or moved in with their loved one. ADL help was hard on both parties, from patients not accepting help, to the new caregiving role preventing them to simply ‘be’ with their loved one.

Caregivers experienced intense stress and sacrificed their own wellbeing to care for the person with sCJD ‘I really could not believe that … I didn’t have either a nervous breakdown, a heart attack or something, because the level of stress’ (c2). Respondents expressed sadness or anger at the many losses experienced by the patient and worried about their suffering.

Caregivers struggled as care needs of the patient surpassed available resources, eventually recognizing their own limits: ‘I finally brought somebody in to help me because I couldn’t do it anymore on my own’ (c3). Obtaining professional caregiving was challenging due to the high cost or limited availability, with some facilities unwilling to care for someone with CJD. Caregivers had limited means for other support: ‘I wasn’t able to afford on a cash basis somebody to come twice a day seven days a week to take care of his incontinence and so I had to do it myself still in spite of hospice coming … It’s not comprehensive enough’ (c4).

Caregivers experienced ongoing grief, fatigue, and distress after the patient died: ‘it took me a good year to kind of recover from the emotional and physical toll that it took on me’ (c4). One compared her experience to post-traumatic stress disorder, noting that aspects of it still ‘haunted’ her (c9). Reflecting on the caregiving experience, many expressed sadness or cried during the interview.

Sources of support and amelioration

We identified 2 major categories of support – clinical care and caregiving.

Clinical care

Despite challenges, many respondents also experienced clinicians and clinical care as sources of support (). Caregivers appreciated clinician guidance about diagnosis, prognosis, or referrals. Anticipatory guidance was particularly helpful: to understand the patient’s disease trajectory, ‘[the doctor] told me to focus on the rate of change of various phases, … [if] it’s accelerating or he’s moving to another function loss that is your sign that he’s moving forward. But if he stabilizes somehow … that may not be sign that’s [he’s] ready to go. That really helped me’ (c4). Guidance about when to seek additional help and the expected disease course, including how to recognize signs of imminent death, helped caregivers feel prepared, take breaks, and feel less guilt.

Caregivers valued clinicians’ expertise in sCJD, particularly early in the disease journey, when detailed explanations of the disease were helpful. Respondents appreciated expert management of medications and advice about behavioural adaptations to manage sCJD symptoms. Confirming the CJD as sporadic (not genetic) was a source of relief for nearly all.

Sensitive and supportive relationships with clinicians and researchers stood out, such as when clinicians responded quickly and thoroughly: ‘I could call her or text her anytime and she would be answering questions for me’ (c3). Clinicians and others with prion expertise helped caregivers prioritize self-care: ‘[Dr. III] himself …. advised me strongly to back off from [caregiving], that I would potentially cause harm to myself that could be damaging. So I really appreciated that advice’ (c4).

All caregivers reported engaging hospice, sometimes before the diagnosis of CJD. Though some caregivers expressed frustrations with hospice clinicians or the care model (especially lack of continuity), most found hospice helpful for providing hands-on ADL support, breaks, and comfort. They benefited from fast implementation and hospice staff’s expertise in recognizing imminent death and appreciated when hospice made effort to learn about sCJD and inquire about respondents’ knowledge as sCJD caregivers.

Caregiving

Finally, respondents identified sources that facilitated being a caregiver (). They emphasized the benefit of reading or hearing stories from, or connecting with other sCJD caregivers, via YouTube, Facebook, and the CJD Foundation: ‘all you want to do is talk to people that have been through it. Because you don’t know what to expect’ (c7).

Caregivers benefited from instrumental support (e.g. paid caregivers or facilities relieved caregiving burden): ‘I did all the heavy lifting at our house … When we transferred to the care facility, I felt lighter’ (c7). Friends or family also provided ADL, legal or financial help, such as documenting preferences or decision-makers while the patient was still able to make decisions. Many narratives indicated that socioeconomic resources were essential, such as being able to pay for caregiving, having access to state-funded care, and/or having jobs that permitted reduced schedules and lengthy leaves of absence.

Social and emotional support was beneficial. Much of this came from friends and family, e.g., keeping the patient company or reminding (and helping) the caregiver to take a break: ‘There wasn’t anything to do except support her and everybody was ready, willing and able to sign up’ (c5). Some caregivers benefitted resilience-bolstering activities, such as religious practice or exercise. Others found comfort in maintaining close connection to the person with sCJD; one caregiver did ‘spa days’ for his wife after she was bedbound (c12).

Caregiver recommendations or wishes

Caregivers also identified items that they thought would have been helpful to them or future sCJD caregivers. Though hypothetical, these insights may be useful for intervention development.

Regarding clinical care, some caregivers felt earlier accurate diagnosis and familiarity with sCJD among clinicians, hospice staff, and funeral home directors would have made the experience less difficult. Some recommended that clinics provide resources about expected symptoms and prognosis, what to take care of (e.g., advance care planning), resources (e.g., CJD Foundation, support groups, local hospice organizations), and contact information for expert advice about sCJD management to give facilities, hospices, and funeral homes.

Regarding caregiving, some respondents thought they would have benefited from more self-care and time connecting with the patient. When asked for recommendations for future sCJD caregivers, respondents echoed these themes: spend more meaningful time with the patient, have more patience with themselves and the patient, connect with other sCJD caregivers, and engage hospice care.

Discussion

This novel study provides an expanded understanding of challenges experienced by caregivers and persons with sCJD and identifies opportunities for improvement. Challenges primarily related to clinical care and caregiving and were exacerbated by the unique nature of sCJD. To our knowledge, this is the first in-depth description of palliative care needs of persons with sCJD. Ford et al. (2018) previously studied caregivers’ struggles to manage symptoms of patients with sCJD and found the most problematic to be mobility and coordination, mood and behaviour, personal care and continence, eating and swallowing, communication, and cognition and memory [Citation20 – 23, 7]. Caregivers in our study voiced similar challenges with symptoms, and described broader sources of distress and challenges. Caregivers framed changes in patient function within the larger context of major losses and changes to relationships, life plans, and family roles. We additionally asked about supports to identify factors that ameliorated caregivers’ difficulties. Supports were often the inverse of challenges, such as sensitive versus insensitive disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis.

Data on sources of distress and support in sCJD facilitates the development of neuropalliative tools and interventions. demonstrates how palliative care approaches might be integrated into neurology practice for sCJD and slower-progressing dementia syndromes. For example, neurology trainees can be taught to use serious illness communication strategies [Citation24] for sensitively disclosing a diagnosis of sCJD and asking if patients and caregivers want prognostic information or anticipatory guidance at this time [Citation25,Citation26]. Findings from this study can facilitate improving sCJD-specific care among hospice and palliative care clinicians. Neuropalliative-infused interventions for improving sCJD care will need to be refined with interdisciplinary multi-stakeholder input and tested for utility and effectiveness.

Table 7. Neuropalliative care intervention targets, and solutions, in sCJD

Evidence regarding neuropalliative care needs in sCJD may be applicable to other rare and rapidly progressive diseases with no cure, as well as longer-course neurodegenerative diseases. A recent systematic review of factors influencing the provision of palliative care to persons with advanced dementia report similar problems: difficulty managing symptoms, lack of continuity of care, and lack of clinician skill in palliative care (such as sensitive disclosure of information or providing anticipatory guidance) [Citation27]. A systematic review of integration of palliative care into dementia management highlights the importance of discussing disease trajectory and expectations and challenges from suboptimal symptom and medication management [Citation28]. These challenges appeared in our study as well. We are adapting the analytic approach of this sCJD study to our parallel efforts to identify neuropalliative intervention targets for longer-course dementia syndromes [Citation29–31].

Limitations of the study include a relatively small sample at one institution, albeit one that recruits study participants nationally (and even globally) for this rare disease. Demographics of participating caregivers suggest that they are well-resourced. Caregivers with fewer resources may encounter more, or more severe, challenges than documented here. Future research should engage larger, more socioeconomically- and globally-diverse populations, and other RPDs that may raise different caregiving challenges. Nevertheless, these novel findings provide foundational data for further research and intervention development.

In summary, this study drew on palliative care frameworks and mixed methods to yield a comprehensive description of challenges, supports, and opportunities to improve care for people with sCJD and their caregivers. Though sCJD is rare and rapidly progressing, the themes uncovered provide a framework for ongoing efforts to improve neuropalliative care for dementia care more broadly.

Methods:

Design: We conducted an exploratory mixed methods study [Citation32] to capture in-depth information about challenges and sources of support among persons with sCJD and their former caregivers. This study drew from interviews with former caregivers of people who died from sCJD and research chart data about the person with sCJD. It was approved by the University of California San Francisco (UCSF) Institutional Review Board and comports with the Consolidated Criteria For Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ; Appendix) [Citation33].

Participants and setting: We identified caregivers from the UCSF Memory and Ageing Center (MAC) RPD research programme database, which includes extensive information on individuals who consented to the ongoing use of their data from medical records and/or from research records through an IRB-approved study of RPDs [Citation34]. We purposively sampled caregivers of persons who died with sCJD at least 3 months but no more than 3 years previously to capture variation in degree of interaction with the UCSF MAC RPD research team and to capture variation in clinical presentation through sCJD molecular classification [Citation19,Citation35]. Of 23 candidate caregivers approached before recruitment closed due to COVID-19, 12 agreed to participate.

Data collection: Caregiver interview domains focused on key experiences along the patient’s disease trajectory; caregiver activities and quality of life; challenges and sources of distress; and things that did or could have helped them to care for the person with sCJD; and a demographic survey (Appendix). Phone-only interviews were conducted from September 2019 through March 2020 (median 88 minutes, range 41–161). Caregivers provided written consent and agreed to digital recording. Recordings were professionally transcribed.

We extracted demographic and clinical data on patients linked to recruited caregivers from the UCSF MAC RPD and UCSF MAC general research (‘LAVA’) databases. For patients who participated in a 2-day outpatient research visit, data included assessments of cognition [Citation36] [Citation37],, neuropsychiatric symptoms [Citation38],, function [Citation39] [Citation40],, and disease characteristics (). For inpatients who were only seen in the UCSF clinical wards (and did not participate in the more extensive 2-day research visit), more limited data was extracted from their EPIC electronic health record and (if available) RPD and LAVA databases. Sources of diagnostic information included brain tissue pathology, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers [Citation41], brain MRI summary, and prion protein gene (PRNP) analysis [Citation42] ().

Data management and analysis: Patient data were summarized using descriptive statistics. Caregiver data were summarized in structured case summaries that included emergent themes and interviewer reflections. We iteratively reviewed chart data, case summaries, and transcript excerpts throughout data collection to refine analytic approaches and identify preliminary themes.

We employed both deductive and inductive coding to identify themes. Deductive codes reflected concepts from the interview framework: challenges or sources of distress, sources of help, and caregiver recommendations for improvements. Inductive codes reflected meaningful concepts emerging from the interviews (e.g., disease rarity, rapidity, transmissibility). Three authors (KLH, SBG and CSR) iteratively refined codes by double-coding and discussing discrepancies until agreement had been met; KLH applied the updated codebook to all transcripts. Analysis was guided by the constant comparative method [Citation43], which uses iterative comparisons within and between analytic cases. The team maintained an audit trail of methodological and analytic decisions.

Author contributions

KLH: study conceptualization/design, data analysis and interpretation, drafting/revising manuscript for content, obtaining funding

SBG: study conceptualization/design, data acquisition, data interpretation and analysis, drafting/revising manuscript for content

ABS: study conceptualization/design, data interpretation and analysis, drafting/revising manuscript for content

JG: data acquisition, data interpretation/analysis, drafting/revising manuscript for content

MJT: data acquisition, data interpretation/analysis, revising manuscript for content

CSR: study conceptualization/design, data interpretation and analysis, drafting/revising manuscript for content

MDG: study conceptualization/design, data acquisition, data interpretation and analysis, drafting/revising manuscript for content

Sources of Support

Research reported in this publication was the Global Brain Health Institute (GBHI), Alzheimer’s Association, and Alzheimer’s Society Pilot Awards for Global Brain Health Leaders, as well as the National Institutes of Health (NIH), National Institute on Aging (NIA) grants R01-AG031189 (MDG), R56 AG055619 (MDG) and R01 AG062562 (MDG) and the Michael J. Homer Family Fund (MDG).

Additional funding supporting investigators’ time included the Atlantic Fellowship for Equity in Brain Health (KLH, ABS, JG), AHRQ T32HS022241(SBG), Maurange Fund, King Baudouin Foundation (JG), NIH/NIA K01AG059831 (KLH) and K01AG059840 (ABS), and California State Alzheimer’s Disease Program Grant 19-10,615 (ABS).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (40.2 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the patients, caregivers, and their families for participating in our research; referring physicians; the U.S. National Prion Disease Pathology Surveillance Center (NPDPSC) for PRNP analyses, prion typing and pathological analyses; the U.S. CJD Foundation (for supporting our patients and families). The authors thank Aili Golubjatnikov and Megan Casey for their assistance in identifying potential caregivers, and Nicole Boyd and Madina Halim for administrative help. All analyses, interpretations and conclusions reached through this project are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nakatani E, Kanatani Y, Kaneda H, et al. Specific clinical signs and symptoms are predictive of clinical course in sporadic Creutzfeldt−Jakob disease. Eur J Neurol. 2016;23:1455–1462.

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease fact sheet, Last updated May 9, 2018, Accessed on 2018, Accessed on May 9, 2018 May 9, 2018, Accessed on May 9, 2018, Accessed on May 9.

- Bechtel K, Geschwind MD. Ethics in prion disease. Prog Neurobiol. 2013;110:29–44.

- McQuain JA, Galicia-Castillo MC, Morris DA. Palliative care issues in Creutzfeldt: jakob Disease #389. J Palliat Med. 2020;23:424–426.

- Appleby BS, Yobs DR. Symptomatic treatment, care, and support of CJD patients. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;153:399–408.

- Paterson RW, Torres-Chae CC, Kuo AL, et al. Differential diagnosis of Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease. Arch Neurol. 2012;69:1578–1582.

- Ford L, Rudge P, and Robinson K, Collinge J, Gorham M, Mead Set al. The most problematic symptoms of prion disease – an analysis of carer experiences. Int Psychogeriatr. 2019;31(8):1181-1190. doi:10.1017/S1041610218001588.

- de Vries K, Sque M, Bryan K, et al. Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: need for mental health and palliative care team collaboration. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2003;9:512–520.

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Kluger B, Kelly AG, et al. Neuropalliative care: priorities to move the field forward. Neurology. 2018;91:217–226.

- Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Palliative care in neurology. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92:1592–1601.

- van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Cmpm H, et al.; European Association for Palliative Care (EAPC). White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European association for palliative care. Palliat Med. 2014;28:197–209.

- Bailey B, Aranda S, Quinn K, et al. Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: extending palliative care nursing knowledge. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2000;6:131–139.

- Das K, Davis R, Dutoit B, et al. Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease: a description of two cases. Int Psychogeriatr. 2012;24:1183–1185.

- Kranitz FJ, Simpson DM. Using non-pharmacological approaches for CJD patient and family support as provided by the CJD foundation and CJD insight. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2009;8:372–379.

- Geschwind MD. Prion diseases. Continuum (Minneap Minn). 2015;21:1612–1638.

- Mitchell SL, Teno JM, Kiely DK, et al. The clinical course of advanced dementia. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1529–1538.

- Appleby BS, Yobs DR. Symptomatic treatment, care, and support of CJD patients. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;153:399–408.

- National Coalition for Hospice and Palliative Care. 2018 . Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. 4th ed. Richmond, VA, USA.https://www.nationalcoalitionhpc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/NCHPC-NCPGuidelines_4thED_web_FINAL.pdf

- Parchi P, Giese A, Capellari S, et al. Classification of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease based on molecular and phenotypic analysis of 300 subjects. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:224–233.

- Collins SJ, Sanchez-Juan P, Masters CL, et al. Determinants of diagnostic investigation sensitivities across the clinical spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2006;129:2278–2287.

- Information for funeral and crematory practitioners | creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, classic (CJD) | prion disease | CDC, Last updated September 7, 2021, Accessed on September 7, 2021.

- Lewis M, Glisic K, Jordan D, et al. OVERVIEW FOR FUNERAL SERVICE PROFESSIONALS. 3.

- Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease foundation, funeral professionals, Last updated August 23, 2016, Accessed on August 23, 2016.

- Bernacki RE, Block SD; American College of Physicians High Value Care Task Force. Communication about serious illness care goals: a review and synthesis of best practices. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174:1994–2003.

- Creutzfeldt CJ, Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Neurologists as primary palliative care providers. Neurol Clin Pract. 2016;6:40–48.

- Back A. Mastering communication with seriously Ill patients: balancing honesty with empathy and hope. New York: Cambridge University Pres, Cambridge England; 2009.

- Mataqi M, Aslanpour Z. Factors influencing palliative care in advanced dementia: a systematic review. BMJ Support Palliat Care. 2020;10:145–156.

- Senderovich H, Retnasothie S. A systematic review of the integration of palliative care in dementia management. Palliat Support Care. 2020;18:495–506.

- Bernstein Sideman A, Harrison KL, Garrett SB, et al.; Dementia Palliative Care Writing Group, Ritchie CS. Practices, challenges, and opportunities when addressing the palliative care needs of people living with dementia: specialty memory care provider perspectives. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2021;7:e12144.

- Boyd ND, Naasan G, Harrison KL, et al. Characteristics of people with dementia lost to follow-up from a dementia care center. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2021;37. DOI:10.1002/gps.5628

- Naasan G, Boyd ND, and Harrison KL, et al. Group G dementia geriatric palliative care writing (2021) Advance directive and POLST documentation in decedents with dementia at a memory care center: the importance of early advanced care planning. Neurol Clin Pract. Feb 2022, 12(1): 4-21. DOI: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000001123 https://cp.neurology.org/content/12/1/14

- Rendle KA, Abramson CM, Garrett SB, et al. Beyond exploratory: a tailored framework for designing and assessing qualitative health research. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e030123.

- Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357.

- Takada LT, Kim M-O, Cleveland RW, et al. Genetic prion disease: experience of a rapidly progressive dementia center in the United States and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2017;174:36–69.

- Brown DR, Schmidt B, Kretzschmar HA. Role of microglia and host prion protein in neurotoxicity of a prion protein fragment. Nature. 1996;380:345–347.

- Lenore K, Meredith W. The mini-mental state examination (MMSE). J Gerontol Nurs. 1999;25:8–9.

- Morris JC. Clinical dementia rating: a reliable and valid diagnostic and staging measure for dementia of the Alzheimer type. Int Psychogeriatr. 1997;9(1):173–176. discussion 177-178.

- Yesavage JA, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1982;17:37–49.

- Thompson AGB, Lowe J, Fox Z, et al. The medical research council prion disease rating scale: a new outcome measure for prion disease therapeutic trials developed and validated using systematic observational studies. Brain. 2013;136:1116–1127.

- Hartigan I. A comparative review of the Katz ADL and the Barthel Index in assessing the activities of daily living of older people. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:204–212.

- Hermann P, Appleby B, Brandel J-P, et al. Biomarkers and diagnostic guidelines for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021;20:235–246.

- Kim M-O, Takada LT, Wong K, et al. Genetic PrP prion diseases. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2018;10:a033134.

- Boeije H. A purposeful approach to the constant comparative method in the analysis of qualitative Interviews. Qual Quantity. 2002;36:391–409.

- Cummings JL, Mega M, Gray K, et al. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: comprehensive assessment of psychopathology in dementia. Neurology. 1994;44:2308–2314.

- Forner SA, Takada LT, Bettcher BM, et al. Comparing CSF biomarkers and brain MRI in the diagnosis of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurol Clin Pract. 2015;5:116–125.

- Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES—A Six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–311.

- Bernacki R, Hutchings M, Vick J, et al. Development of the Serious Illness Care Program: a randomised controlled trial of a palliative care communication intervention. BMJ Open. 2015;5:e009032.

- Piers R, Albers G, Gilissen J, et al. Advance care planning in dementia: recommendations for healthcare professionals. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:88.

- Possin KL, Merrilees JJ, Dulaney S, et al. Effect of collaborative dementia care via telephone and internet on quality of life, caregiver well-being, and health care use: the care ecosystem randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179:1658.

- Rosa TD, Possin KL, Bernstein A, et al. Variations in costs of a collaborative care model for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67:2628–2633.

- Bernstein A, Merrilees J, Dulaney S, et al. Using care navigation to address caregiver burden in dementia: a qualitative case study analysis. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 2020;6:e12010.

- Bernstein A, Harrison KL, Dulaney S, et al. The role of care navigators working with people with dementia and their caregivers. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;71:45–55.

- van der Smissen D, Overbeek A, van Dulmen S, et al. The feasibility and effectiveness of web-based advance care planning programs: scoping review. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e15578.

- Sudore RL, Schillinger D, Katen MT, et al. Engaging Diverse English- and Spanish-Speaking Older Adults in Advance Care Planning: the PREPARE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:1616.

- Sudore RL, Boscardin J, Feuz MA, et al. Effect of the PREPARE website vs an easy-to-read advance directive on advance care planning documentation and engagement among veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:1102.

- Wolff JL, Roter DL, Boyd CM, et al. Patient-Family Agenda Setting for Primary Care Patients with Cognitive Impairment: the SAME Page Trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1478–1486.

- O’Shea B, Martin D, Brennan B, et al. Are we ready to “think ahead”? Acceptability study using an innovative end of life planning tool. Ir Med J. 2014;107:138–140.

- Mitchell SL, Shaffer ML, Cohen S, et al. An advance care planning video decision support tool for nursing home residents with advanced dementia: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2018;178:961–969.