?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Despite substantial cross-national interest in remedial programming as a way to support low-achieving students, evidence of its effectiveness is rare, particularly in low-income and/or crisis-affected contexts. In this article, we present experimental evidence of the impact of a remedial tutoring program on academic outcomes from a two-level randomized trial of two treatments in Niger: school randomization testing the impact of skill-targeted SEL activities and within-school student-level randomization testing the impact of access to remedial tutoring. We find that tutoring for 4 h per week improves students’ literacy and Math outcomes, and the addition of skill-targeted SEL activities positively impacts school grades above and beyond access to tutoring alone. These findings suggest the potential value of remedial tutoring to supplement formal schooling in low-income and/or conflict-affected contexts. They also suggest increased attention to implementation strategies, as access alone was insufficient for students to attain grade-level competencies.

Worldwide, hundreds of millions of children leave primary school without the most foundational of academic skills, functionally illiterate and unable to complete basic arithmetic tasks (Filmer et al., Citation2018). In response, there has been substantial cross-national interest in both increasing instructional time and/or providing more targeted academic support to students within and outside the formal schooling system. For example, a recent UNICEF-UNESCO-World Bank survey of Ministries reports that a majority of the 118 countries surveyed intend to implement remedial programming in the 2020–2021 school year (UNESCO, Citation2020).

Yet the remediation of students–generally defined as a short-term increase in instructional time or targeted academic support to students whose proficiencies in content or skill are below expected levels for grade–has historically proven challenging for governments (AEWG, Citation2017; Schwartz, Citation2012). This challenge is especially acute in low-income countries, where poverty, malnutrition, and hazardous environments can impair healthy physical and mental development of children, and where families’ and communities’ competing economic demands impede children’s school attendance rates. Within low-income contexts, students in regions affected by conflict and crisis face even more hurdles to learning, including exposure to violence, increased “daily stressors” of internal displacement or resettlement, safety constraints getting to and from school, and the potential developmental effects associated with persistent, toxic stress (Dryden-Peterson, Citation2010; Miller & Rasmussen, Citation2010).

This article employs a two-level randomized design of non-comparable treatment groups to test experimental impacts on academic outcomes of a remedial tutoring program—specifically, Tutoring in a Healing Classroom (HCT). Given emerging evidence that HCT was effective at raising student outcomes in other contexts (Aber et al., Citation2021), it was considered unethical to withhold treatment from schools. HCT incorporates foundational social-emotional principles into classroom practices and is implemented by a non-governmental organization (NGO) in collaboration with a ministry of education. As governments are increasingly called upon to integrate previously parallel education programming between the formal and non-formal sectors (Mendenhall et al., Citation2017), a remedial model that aims to increase retention in, and derive increased benefits from, the formal school system can provide governments with a pragmatic intermediary stage of shared responsibility with NGOs prior to the full provision of quality education services by government for crisis-affected and/or low-income countries.

Remedial Education in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMIC)

Two primary methods currently exist to increase proficiency of low-achieving students in the low and middle-income countries: supplemental education and accelerated learning programs. Whereas accelerated learning programs condense school curricula into a shorter timeframe that run separate from formal school (often with the aim of reintegration into formal schooling), supplemental education programs—such as remedial—run concurrent with, and aim to support retention in, formal education (AEWG, Citation2017).

Rigorous evidence suggests that provision of remedial educational programming can improve learning in middle-income countries (Banerjee et al., Citation2007; Saavedra et al., Citation2019), offering a promise of increasing academic outcomes for millions of children. However, evidence on remedial programming to date is limited in low-income contexts and nearly absent in areas also affected by crisis or conflict despite the fact that children who live in such contexts are most likely to require such services (Schwartz, Citation2012). Indeed, governments of low-income countries often struggle technically, institutionally, and financially to provide universal quality education, let alone supplemental academic programming.

Two recent reviews of research in LMICs support the potential of remedial programming. Ganimian and Murnane (Citation2016) find that both increasing academic time and targeting low-achieving students for increased academic support can be effective at raising student achievement, particularly for low-achieving students. McEwan (Citation2015) finds that interventions that incorporate instructional materials, teacher training, or targeted learning produce average effect sizes in the range of 0.08–0.12.

Various models of remedial programs exist, including provision of programming during the school day (“pull-out”) and those that provide additional instruction before or after formal school hours. An example of a successful pull-out model is “Balsakhi” or “friend of the child,” a widely-implemented NGO-led program in India. Banerjee and co-authors’ (2007) multi-year evaluation of Balakshi–where academically struggling students in municipal schools were tutored during school hours by young women from the local community–has demonstrated average test score increases of 0.14 standard deviations in the first year, doubling to 0.28 in the second year. A similar government-led program in Ghana also increased student test scores for students in grades 2 and 3 by 0.14 standard deviations (Duflo et al., Citation2020). While the results are promising, pull-out programs remove students from their normal classroom instruction and take away the opportunity for children to learn alongside their grade-level peers.

Instead, providing additional instruction time outside of the formal school day may be more effective and sustainable. Two remedial programs implementing this model in Latin America and one in Africa have shown promise in raising student outcomes: (1) a science tutoring program in Peru targeted at low-achieving third graders, (2) the support of a “Mobile Pedagogical Tutor”—recent college graduates with short-term training in math and literacy tutoring—in Mexico, and (3) an assistant-led remedial after-school program in Ghana for students in grades 2 and 3 (Agostinelli et al., Citation2018; Duflo et al., Citation2020; Saavedra et al., Citation2019). All studies found positive impacts on student academic outcomes (0.12 standard deviations in science in Peru; 0.15 in math and 0.23 in literacy in Mexico; 0.15 in foundational test score questions in Ghana). However, two of the interventions may have unintentionally exacerbated existing achievement gaps. In Peru, boys benefited nearly twice as much from the program as girls (0.22 standard deviations and non-significant, respectively) and neither program demonstrated benefits for the lowest-achieving students. By contrast, girls benefited more than boys in both remedial interventions implemented in Ghana (0.10 standard deviations). While such results are promising, only the intervention in Ghana provided evidence of reaching the most marginalized populations (i.e. girls and low-achieving students). Given the high proportion of vulnerable students in low-income and conflict-afflicted regions–inclusive of displaced groups such as refugees– it’s important to understand more about the potential heterogeneity of program effects of remedial programming and how they may affect disadvantaged students.

Indeed, there are many unique challenges to low-income and conflict-affected regions that may inhibit the implementation or effectiveness of remedial programming. As mentioned above, governments in regions affected by conflict and crisis often shoulder a disproportionately large burden of schooling vulnerable populations of refugees and displaced persons (Dryden-Peterson, Citation2010; Schwartz, Citation2012). In many cases, the state is struggling to provide basic education services to an influx of displaced students even prior to attempts to provide supplementary educational programs. In Niger, for example, attacks by the extremist group Boko Haram in late 2014 caused an estimated 30,000 refugees per month to enter from neighboring Nigeria, further straining already under-resourced economic and academic systems (Meier, Citation2017). In such cases, humanitarian crises and/or longstanding development challenges may impede quality implementation by governments in these contexts. Instead, service provision of supplemental programming by non-state actors like NGOs may present a more feasible and impactful method of providing additional educational support in the short-term.

Second, high-quality provision of services is only half of the learning equation. Contexts of crisis and conflict are often marked by a highly mobile population, household economic stressors, and unpredictable security threats (Human Rights Watch, Citation2016). Such factors can limit student attendance, ultimately decreasing the dosage of programming that students receive (Tubbs Dolan et al., Citation2022). It is not clear whether these programs would continue to produce impacts at de facto decreased dosages seen in low-income and crisis contexts.

Last, early life experiences of vulnerable student populations—inclusive of extreme poverty, violence, or abuse—can profoundly impact cognitive and social-emotional development (Kim et al., Citation2020; Reed et al., Citation2012). Academically, such students may require different or additional support in order to successfully deploy attention or process new information at the same level as their peers. Socially, students who have experienced trauma are more likely to struggle to regulate their emotions or to establish relationships with peers and/or adults (Hart, Citation2009). These differences likely necessitate an academic approach that prioritizes learning within a safe, predictable, and supportive classroom environment, and may even necessitate activities that target specific foundational social-emotional skills with explicit instruction.

Social Emotional Support to Improve Learning Outcomes

The existing evidence on remedial programming also overlooks the role of social-emotional support as a way to improve academic outcomes. Social-emotional skills are broadly-defined as the “social, emotional, behavioral, and character skills required to succeed in schooling, the workplace, relationships, and citizenship” and can be grouped into domains of cognitive, emotional, and interpersonal skills (Jones et al., Citation2017, p. 12). A growing body of research, mostly from high-income countries, indicates that supporting social-emotional skills can contribute to increased academic outcomes (e.g., Durlak et al., Citation2011; Heckman & Rubinstein, Citation2001). A focus on social and emotional learning (SEL) competencies is theorized to produce more supportive learning environments, higher academic engagement, better emotional regulation, and more pro-social behavior, which in turn leads to a reduction in disruptive classroom behavior for individual students and among peers, contributing to improved academic success (CASEL, Citation2015). There are several methods of incorporating SEL strategies into the classroom, including: (1) infusing SEL principles and practices into classroom management and positive pedagogy—referred to here as “climate-targeted” SEL—designed to provide a safe and supportive classroom climate that creates optimal conditions for the development of social and emotional competence (CASEL, Citation2021) and (2) providing explicit “skill-targeted” training to children on how to process, integrate, and appropriately apply specific social and emotional skills in real-world situations (Durlak et al., Citation2011).

Despite the substantive evidence of the importance of social-emotional skills for student educational and labor market outcomes in high-income countries (Carneiro et al., Citation2007; Heckman & Rubinstein, Citation2001; Taylor et al., Citation2017), little rigorous evidence confirms their importance in low-income countries, particularly in Sub-Saharan Africa. Social-emotional skills may be especially critical in conflict-affected settings where many children suffer from exposure to violence, internal displacement and/or forced migration, in addition to milder daily stressors of living in a low-resourced, unsafe, and uncertain environment (Reed et al., Citation2012); conversely, the volume and severity of environmental stressors may overwhelm any potential benefit of SEL. What is known is that positive relationships with adults, safe and predictable environments, social problem solving skills, and positive self-concept have been demonstrated to strengthen student resilience and to buffer them against the detrimental effects of contextual risks, supporting children to better engage in academics (Cowen et al., Citation1996; Shanks & Robinson, Citation2013; Starkey et al., Citation2019).

Despite the potential that an SEL-infused remedial program could support low-performing children to reach their expected academic milestones–a potential that remains highly relevant for educators and policy makers facing billions of students with learning loss–it is uncertain whether positive effects found in high and middle-income countries would extend to low-income and conflict-affected contexts, with unique and complex challenges.

Tutoring in a Healing Classroom (HCT) Intervention

Learning in a Healing Classroom is an SEL-infused curricular approach for basic education programming developed by the International Rescue Committee. It focuses on improvement in children’s math and literacy skills while providing foundational social-emotional support, such as a safe and supportive classroom environment, for primary school-aged children in conflict- and crisis-affected settings. Foundational SEL principles are exhibited through positive classroom practices, e.g., classroom management, establishment of classroom culture, and positive pedagogy. In a formal school setting, Learning in a Healing Classroom led to significant improvements in children’s academic outcomes and perceptions of the safety and supportiveness of school environments in a cluster-randomized control trial in the Democratic Republic of Congo (Aber et al., Citation2017; Torrente et al., Citation2019); HCT does not explicitly target, nor have they shown impacts on, children’s SEL skills. This study extends the evidence of effectiveness of the Learning in a Healing Classroom approach by testing whether it can address the needs of a low-income, conflict-affected population through a non-formal, tutoring format (Tutoring in a Healing Classroom, HCT).

In Niger, IRC adapted the Learning in a Healing Classroom formal school approach to a tutoring program (HCT) for second to fourth grade children attending public schools who demonstrated below grade-level literacy and numeracy competencies. The tutoring program was implemented by 90 IRC-trained public school teachers who provided literacy and Mathematics lessons in a safe and supportive environment 3 days per week after school, for a total of four additional hours weekly. Tutoring teachers received 5 days of in-service training on literacy and numeracy curricula infused with universal SEL principles, ongoing support in the form of monthly peer support groups (Teacher Learning Circles), and aligned one-on-one pedagogical coaching by the regional ministry of education.

HCT+ Act Intervention: HCT with Brain Games and Mindfulness

In this study, a version of HCT (HCT+ Act) was tested that incorporates the addition of two types of skill-targeted SEL activities to the foundational SEL practices implemented in HCT: Brain Games activities, focused on promoting children’s executive functions; and Mindfulness activities, focused on improving emotion and stress regulation. These explicitly-taught, skill-targeted SEL activities were implemented three times per tutoring session: at the beginning, end, and during the transition from literacy to math instruction (total 30 min per day, 90 min per week). In the HCT condition, these subject transitions were teacher-supervised breaks. Mindfulness activities were the focus of targeted SEL activities during the first half of the tutoring sessions (11 weeks; November 2016–March 2017), while Brain Games activities were the focus of the targeted SEL activities during the second half (11 weeks; March 2017–June 2017). Students in both HCT and HCT+ Act received the same academic curriculum.

Mindfulness activities entailed breathing techniques, attention to sensory stimulation, and attention to the present environment and consisted of three types: (1) Discovering, focusing on body and emotion awareness; (2) Experimenting, focusing on students’ understanding of how different movements and sensations change how they feel; and (3) Accepting, focusing on more complex activities that required students to be still for longer periods of time and aware of their surroundings. Teachers were free to choose which of the 23 Mindfulness activities they implemented on any given day.

Activities were designed to improve children’s skills to regulate their physiological responses to the chronic and/or toxic stress associated with exposure to conflict, internal displacement and/or forced migration. Increasing evidence suggests Mindfulness practices can help to mitigate risks associated with physiological stress responses in both adult and school-aged populations in western contexts (Zenner et al., Citation2014). In addition to decreasing stress reactivity–thereby increasing cognitive bandwidth for learning–there is evidence that mindfulness practices can increase attentional capacity (Jha et al., Citation2007; Tang et al., Citation2007) as well as length of attention span (Sauer et al., Citation2012).

Brain Games (Jones & Bouffard, Citation2012) activities included short game-like activities designed to help students build and practice three “brain powers” of executive function: (1) Focus Power (flexibility of attention deployment), (2) Remember Power (working memory), and (3) Stop & Think Power (inhibitory control). Each game was designed to follow a similar structure: explanation of purpose, introduction of the brain power of the day, game instructions with demonstration, game play, and post-game talk. Again, teachers were free to choose which of 20 Brain Games activities they implemented on any given day.

Executive function has a robust correlational relationship with academic outcomes. For example, executive function (a combination of working memory, flexibility of attention deployment and inhibitory control) is predictive of future academic achievement in early primary grades, controlling for current academic competence (Blair & Razza, Citation2007; Kim et al., Citation2020). In addition, improvement in executive function has been demonstrated to improve standardized math scores (Holmes et al., Citation2010; Roberts et al., Citation2011). Yet experiences of early childhood adversity–such as low parental education, poverty, and residential mobility–have been shown in high-income settings to impede children’s development of executive function (Blair, Citation2010; Finch & Obradović, Citation2017; Hackman et al., Citation2015; Lawson et al., Citation2018; Roy et al., Citation2014). Specifically targeting this set of skills through specific activities may buffer against such risks and increase students’ chances of academic success.

Current Study

This study is designed to add to the nascent evidence base of the effectiveness of remedial programming, inclusive of SEL practices in LMIC and explore potential variation in impact. Specifically, we test the following questions: (1) Do students with access to either an SEL-infused tutoring program (HCT) or an SEL-infused tutoring program with added skill-targeted SEL activities (HCT+ Act) perform better on academic skills (literacy, numeracy, and school grades) compared to a business as usual control?; and (2) Do students with access to an SEL-infused tutoring program with added skill-targeted SEL activities (HCT+ Act) perform better in academic skills (literacy, numeracy skills, school grades) compared to students with access to the base tutoring program (HCT) alone? (3) Do the impacts of HCT and HCT+ Act vary by children’s gender, refugee status, grades, and baseline literacy and numeracy skills?

This study was designed and registered as a school-randomized study to test the impact of adding skill-targeted SEL activities tutoring programming on a smaller sample (N = 1,800). However, substantially more students qualified for tutoring than could be served based on available funding. We randomly-selected qualified students for available slots in order to equitably distribute access, which created a no-treatment control group from students who qualified for tutoring services but were not selected to receive them. In order to leverage additional learning opportunities from this treatment contrast without increasing data collection costs, we utilized available administrative data as outcome measures: the program screening tool, Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), and public school grades.

Methods

Context

Niger is a landlocked nation in West Africa of approximately 10.1 million people, ranking 189th out of 189 countries on the human development index in 2018, a composite index of life expectancy, education, and income per capita indicators (UNDP, Citation2019). Primary school is compulsory, with 28-h school weeks and enrollment rates of approximately 70%. Despite relatively high enrollment, however, the vast majority of students (86%) are non-proficient in both math and literacy assessments as of 2010 (Ministère de l’Enseignement Primaire, Citation2013). These results placed Nigerien primary students last in basic reading and math outcomes among 10 Francophone sub-Saharan African countries (PASEC, Citation2015, Citation2016).

In 2008, the insurgent group known as Boko Haram began conducting violent attacks in Northern Nigeria, subsequently increasing geographic spread of the attacks throughout the Lake Chad basin and across the Nigerien border into Diffa. The Diffa region—located in the southeasternmost part of Niger with a population of approximately 670,000 persons—has historically been one of the poorest, with corresponding low schooling outcomes (Chekaraou & Goza, Citation2015).

Ethics and Institutional Review

Research contained within this study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both New York University (IRB-FY2016-1174) and the International Rescue Committee (IRB #: 00009752). Local approval was sought from the Niger Ethics review board. Written consent was required of teachers. Children 12 and over were asked to provide written assent, whereas children under 12 were asked to provide verbal assent.

Sample

Research Sites

The current study includes second- through fourth-grade students from 30 public schools in the towns of Diffa and Maine-Soroa, both located in the Diffa department of Niger. The schools were selected from a list of 75 potential sites using the following criteria: (1) security clearance (2) distance from NGO Office <40 km (3) sufficient teachers and students, defined as a minimum of eight teachers and 120 enrolled students (4) serves at least three primary grades, as some schools did not serve the full range of elementary grade levels.

Of the 30 schools selected, 20 schools were traditional French-only schools and the other 10 schools were French-Arabic schools; French-Arabic schools had a religious focus, with instructional emphasis on Arabic (in addition to French), in order to read the Koran. Eighteen schools were located in the town of Diffa, and 12 schools were located in Maine-Soroa. The student composition of the schools varied widely, reflecting the ongoing refugee crisis and ethnic/linguistic diversity of the Diffa region. Specifically, schools ranged from 10% to 42% of refugee or internally displaced students, 0–85% Kanuri speakers, and 0–48% Hausa speakers, and 2–95% Fulfulde speakers, with smaller percentages of the student body speaking other home languages. The majority of second to fourth grade students in our sample struggled academically, with 75–100% of students unable to read Grade One level texts in French and 61–98% of students unable to solve simple subtraction problems in the screening tests (see for the school characteristics by treatment condition.)

Table 1. Control and treatment schools characteristics.

Student Sample

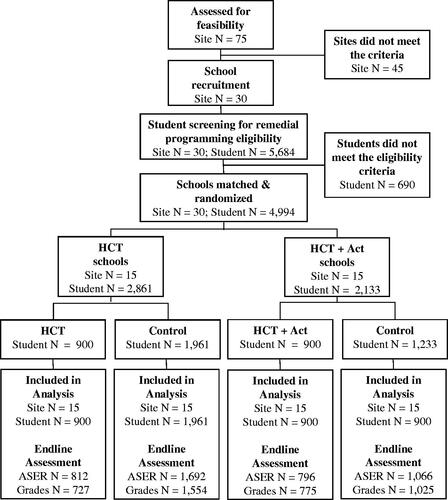

All 4,994 second to fourth grade students in participating schools who met the eligibility criteria are included in the current study (53% girls, 23% refugees). Of all participants, 43% were second graders, 33% were third graders, and the remaining 24% were fourth graders (see ). Differences of participation by grade level are due to differential school enrollment rates (i.e., lower grades have more enrolled students) and a higher probability of upper-grade students passing the academic screening test (therefore not meeting the eligibility criteria for tutoring program; see student screening section for further details).

Table 2. Baseline and endline descriptive statistics by treatment condition, and adjusted differences at baseline between groups.

Randomization

To minimize between-school contamination and maximize within-school treatment contrast of students, treatment conditions (HCT, HCT+ Act, control) were assigned at two levels: school and student, each described below.

School Randomization

To maximize the statistical power with a fixed number of schools, schools were matched on baseline characteristics and randomly assigned to either the HCT or HCT+ Act condition via matched-sample cluster-randomization (MSCR) design. MSCR increases power, statistical efficacy, and robustness of causal impact estimates by reducing the heterogeneity within pairs and between treatment conditions (Imai et al., Citation2009). Schools were matched on a vector of pre-randomization characteristics: school characteristics—such as number of classrooms and teachers–and student-level demographics–such as refugee status, home language, and baseline math and literacy levels. (For a full list of pre-randomization characteristics, see .)

Using the characteristics listed above, optimal nonbipartite matching (Zhang & Small, Citation2009) procedure was conducted using the nbpMatching package for R (Lu et al., Citation2011). Optimal nonbiparitite matching procedure uses mahalanobis distance scores between all possible pairs of clusters given all covariates to produce the set of best-matched pairs with the minimum total multidimensional distance within pairs. Within each pair, one school was randomly assigned to the HCT condition, and the other was assigned to the HCT+ Act condition. The overall characteristics of HCT and HCT+ Act schools were highly comparable ().

Student Eligibility and Randomization

Eligibility for tutoring was based on student performance in math and French literacy on the screening test, adapted from the assessment used for the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER: Banerji et al., Citation2013). The screening test was administered by trained teachers in November of the 2016–2017 school year. All students in grades two through four in the participating schools (N = 5,684; 39% second graders, 34% third graders, 27% fourth graders) were assessed. ASER French literacy and math are graded on a scale from zero to four, each of which represent a specific level of math or literacy competency (e.g. can recognize letters, can add numbers; see data section for additional information on levels). The HCT curriculum was developed to target the “emerging” level of math and literacy skills, defined as a score of two or lower on math and literacy. By these criteria, students eligible for remediation were neither able to read a short paragraph nor able to solve simple subtraction problems.

Eighty-eight percent of all screened students performed at a Level 2 or below (96% of second graders, 85% of third graders, and 79% of fourth graders), qualifying them for tutoring eligibility. Due to the large number of students who met this eligibility criteria (N = 4,994), a total of 1,800 students (90 classrooms across 30 schools, 20 students per classroom) were selected. The student sampling prioritized selecting an equal number of eligible students from each grade level, when possible. This was a programmatic decision to (a) ensure a relatively homogeneous tutoring classroom composition in age and grade level (e.g., three tutoring classes, one at each grade level) as much as possible; and (b) prioritize children in older grades (i.e., those in more urgent need for tutoring support, given grade and proficiency levels). To do so, first, each school was assigned a sample size ranging from 20 to 120 students (that would compose 1–6 tutoring classrooms) depending on the school size, consisting of equal numbers of students from each grade level (6–40 students per grade in each school). All eligible students were assigned a random number; and the students with the random number ranked higher than or equal to the assigned sample size per school and grade, within each grade level in each school, were assigned to the tutoring classes. Students who met tutoring eligibility requirements but were not selected via lottery (n = 3,194) served as a control group attending their business-as-usual public school classes without the opportunity to attend tutoring. Students who did not meet eligibility criteria were excluded from the sample.

For program delivery reasons, 445 students from the control condition were randomized to a waitlist–and randomized by order within the waitlist–to replace treatment students who either never attended or dropped out of the tutoring program. Student replacement of dropout students was desired by the program implementers and its funders to ensure the program reached the maximum number of eligible children. Of these waitlisted students, 190 attended at least one tutoring session, resulting in 4% average attendance rate to tutoring in the control group; these waitlist-turned-treatment students are included in the control group for all calculations to ensure robust causal estimates. In order to better understand the effect of the treatment itself, we then report the LATE to estimate effects on students who complied with treatment assignment.

Research design and sample flowchart is presented in .

Measures

French Literacy and Numeracy

Students’ French literacy and numeracy skills were assessed by trained teachers at the beginning (November) and the end (June) of the school year 2016–2017, using assessments adapted from the Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), a widely-used tool to assess children’s basic literacy and numeracy levels in early grades (Banerji et al., Citation2013). Originally developed in India, ASER has been tested and validated with test-retest, inter-rater reliability, and correlational evidence of validity (Vagh, Citation2009). Short assessment time and ease of administration allows large-scale evaluation of students’ abilities in low-resource settings. IRC adapted the ASER to align with the cultural and linguistic context as well as the Nigerien public-school curriculum. The ASER French Literacy administered in Niger consists of five levels: Beginner (0: cannot recognize letters), Level 1 (1: letter recognition), Level 2 (2: word recognition), Level 3 (short paragraph reading, grade 1 level text), and Level 4 (longer paragraph reading, grade 2 level text). The ASER Math assessment also consists of 5 levels: beginner (0: cannot identify numbers), Level 1 (1: 1- to 3-digit number recognition), Level 2 (2: addition), Level 3 (3: subtraction), Level 4 (4: multiplication).

School Grades

Students’ public-school grade averages for school year 2016–2017 were collected at the end of the academic year. Grade averages range from zero to 10 and include: Reading, Math, Writing, Dictation, Social studies, science, and Drawing/Art.

Covariates

In addition to gender and grade level, students’ age and home language (Fulfulde, Hausa, Kanuri, other) were included in the model to reflect and adjust for the wide range of age, linguistic, and cultural variability in each grade level. School characteristics used in the school matching process were contained within school fixed effects and therefore omitted from the models.

Analytic Strategy

Attrition and Missing Data

Of the 4,994 students who participated in the baseline ASER data collection, 4,366 (87%) students participated in endline ASER assessment and 4,081 (82%) students’ school grades were collected from the administrative data. The follow-up rate was 79–90% (missing rate 10–21%) across different outcomes and treatment conditions (); the largest differential missing rate at the endline between groups for which we tested the treatment contrast is 5%, between HCT (19%) and HCT+ Act (14%) group for school grades, and considered low differential attrition under conservative assumptions (What Works Clearinghouse, Citation2020).

Students who were missing endline ASER scores (n = 628) were less likely to be female (odds ratio (OR) = 0.76, SE = 0.09, p < .05) and more likely to be refugees (OR = 1.62, SE = 0.19, p < .001); and scored lower in the baseline ASER scores for both French reading (b = −0.07, SE = 0.02, p < .01) and math (b = −0.10, SE = 0.05, p < .05), but were not statistically different in their age, grade level, or mother tongue. Students with missing records of school grades were also less likely to be female (OR) = 0.81, SE = 0.74, p < .05) and more likely to be refugees (OR = 1.47, SE = 0.14, p < .001) but were not statistically different in other baseline characteristics or ASER scores.

To account for missing information in the post-test academic outcomes and include the full intent-to-treat sample in the analysis, we conducted multiple imputation. Using MI package (Gelman et al., Citation2015) in R, 10 datasets were imputed using chained models. For each chain of models, 50 iterations were used to obtain robust diagnostics and robust pooled estimates. These models had good convergence for the means.

Analysis

We first estimate intent-to-treat (ITT) effects for HCT and HCT+ Act (within school, between child) and addition of SEL activities (between school) programs on three academic outcomes: French literacy, math, and school grade averages. Then, we report local average treatment effects (LATE) of HCT and HCT+ Act using student attendance rates and explore heterogeneity of impact estimates by grade level, gender, baseline academic performance, and refugee status. In all models, cluster-robust standard errors were used to account for within-school correlations across students in outcomes. Impact estimates were pooled across 10 imputed datasets using Rubin’s rule. The p values for the impact estimates across all outcomes and treatment contrasts were adjusted for Type I error common in multiple hypothesis testing, by controlling the sharpened false discovery rate (Benjamini et al., Citation2006). FDR-adjusted q values are interpreted as statistically significant findings. We report both the impact estimate in the original scale of the outcomes as well as standardized effect sizes adjusted for school and child level variance (dwt), Calculated using the following equation from Hedges (Citation2009):

Where b represents the unstandardized regression coefficient of the impact (e.g., coefficient of impact indicator for the HCT programming), and the two terms of the denominator represent variances at the school and child levels, respectively, adjusted school-pair fixed effects but without covariate adjustment.

Intent-to-Treat HCT Impacts

The average ITT effects of HCT and of HCT+ Act programs were estimated as the average of within-school differences in student outcomes between students who were offered tutoring programming and the students in the business-as-usual control group in each of the treatment arms (15 HCT schools and 15 HCT+ Act schools). Specifically, the ITT effects of the HCT and HCT+ Act for the students assigned to the tutoring program () was estimated by fitting the model:

(1)

(1)

Where Yij is the outcome of student i in school j, δj is a separate intercept (or fixed effect) for each school, Y(t−1)ij is the baseline score of the outcome (omitted for school grades), T is the treatment status of the students (HCT or HCT+ Act versus business-as-usual control), and εij is an idiosyncratic error term for each of the students. We report the unadjusted estimates without student covariates, as well as estimates from the model with student-level characteristics as covariates (baseline scores of ASER literacy and Math tests, gender, age, grade level, refugee status, and mother tongue).

The average ITT effects of additional SEL activities was estimated as the average of between-school differences in student outcomes among the students offered tutoring-only programming (in HCT schools) compared to students with tutoring and skill-targeted SEL activities (in HCT+ Act schools) (School N = 30, Student N = 1,800). For each academic outcome, we fit the model with school-pair fixed effects:

(2)

(2)

Where Yij is the outcome of student i in school matched-pair j, δj is a separate intercept (or fixed effect) for each school pair, Y(t−1)ij is the baseline score of the outcome (omitted for school grades), SEL is the treatment status of the school (HCT+ Act versus HCT only), and εij is an idiosyncratic error term for each of the students.

Local Average Treatment Effects of HCT and HCT+ Act

In addition, we used students’ attendance rates for the tutoring programs to estimate the local average treatment effect (LATE) of HCT and HCT+ Act programming as compared to the control group in the same schools. In these models, random treatment assignment was used as an instrumental variable to estimate the impacts of attending the HCT program in the HCT schools and impacts of attending the HCT+ Act program in the HCT+ Act schools. We estimate the dose-response relationship between attendance rate and student outcomes (μ) using:

(3)

(3)

Where Yij is the outcome of student i in school j, δj is a separate intercept (or fixed effect) for each school, Y(t−1)ij is the baseline score of the outcome (omitted for school grades), Attij is the student’s % attendance to the tutoring program (HCT or HCT+ Act), and εij is an idiosyncratic error term for each of the students. Since program attendance may be endogenous to expected gain from the program, we instrument for Attij with the randomized offer of tutoring services by regressing it on the random assignment to HCT programs or control as well as school fixed effects.

To estimate the variation in impacts of HCT and SEL by gender, grade level, baseline ASER score, and refugee status, an interaction term of the treatment and each student characteristic was added. For example, to test the impact variation across gender, we estimated the following equation:

(4)

(4)

Where oij is the outcome of student i in school j or school matched-pair j. Similar to the ITT effect models, student-specific covariates, and school-pair fixed effects (δj), and student level error terms. εij were included in the model.

Robustness Check

Various alternative model specifications were tested to check the robustness of the findings. The findings were consistent with little variation in effect sizes across multi-level models, models with additional school quality information (student-to-classroom ratio, student-to-teacher ratio, % of classrooms with permanent structure, school-average teacher attendance to the regular schooling), and multivariate models accounting for the covariance across the three outcomes (results are available upon request). We present the results from the most parsimonious and easily interpretable models as final here.

Results

Internal Validity

Balance at Baseline

presents student characteristics by treatment condition. We assess statistical significance of baseline differences by estimating mean difference in each of the baseline variables using school-pair fixed effects models with robust standard errors for school-level clustering. The first two columns of the table present the means and standard deviations of the full sample. The next columns, labeled (1)–(4) represent treatment and business-as-usual control group means and standard deviations for schools assigned to HCT and HCT+ Act conditions. The following columns show baseline differences for each treatment contrast. Students were approximately evenly distributed across control and (any) HCT conditions in gender and mother tongue. However, due to NGO preferences to select even numbers of students in each tutoring classroom despite grade level (and age) imbalance in the public school, there were statistically significant baseline differences in students’ age and grade level between the groups who were randomized to any tutoring programming (HCT or HCT+ Act) compared to eligible students in the same schools who were not. The treatment group had a larger proportion of older students in higher grade levels. In addition, in the schools assigned to the HCT+ Act condition, the treatment group (students offered HCT+ Act programming) had fewer refugee students than the control group in the same schools. Because refugees and lower grade-level students were less likely to be proficient (and therefore more likely to qualify for tutoring), as well as younger, it resulted in the imbalances captured in . The comparison between the students offered tutoring services in the HCT and HCT+ Act schools show no difference in baseline characteristics with the exception of refugee status: the HCT+ Act group had a smaller proportion of refugee students compared to the HCT group. We address these imbalances and associated potential selection bias by (a) including these variables in the model as covariates, and (b) using the imputed dataset and analyzing the full sample that was randomized to conditions (What Works Clearinghouse, Citation2020). In addition, we examine potential impact variation by grade and refugee status (in addition to gender and baseline ASER scores) to identify any unique patterns of impacts that are potentially attributed to selection bias.

Compliance

Among students who were randomized to HCT or HCT+ Act treatment conditions (N = 1,800), 85% of students (N = 1,530) attended at least one tutoring session; the average attendance rate of the intent-to-treat sample was 64% (SD = 31%), with an average of 76% among compliers (defined as those who attended at least one session) and a range of 0–100%.

Given the unpredictability of security in the region, the mobility of the population, seasonal migration, and intermittent teacher strikes, inconsistent attendance is not surprising. Several factors likely played a role, including the refugee crisis, the significant proportion of students (36%) with nomadic and seminomadic tribal backgrounds (i.e., Fulani/Fulfulde-speakers), and labor demands on children’s time. In addition, some tutoring sessions held on Sundays overlapped with Koranic school, despite efforts to avoid scheduling conflicts with religious services. In addition, some resource-constrained schools struggled to systematically promote the program to students and parents, as well as to enroll students.

ITT Impacts of HCT and HCT+ Act Programs

Intent-to-treat impact estimates and effect sizes of the HCT and HCT+ Act programs are summarized in .

Table 3. HCT and HCT + Act program impacts on ASER French, Math, and average school marks.

Average Treatment Effects of HCT and HCT+ Act Program

Assignment to 22 weeks of either tutoring program—HCT or HCT+ Act—had positive, small-to-medium sized impacts on children’s academic outcomes. Specifically, children in the HCT program scored 0.22 of an ASER level (dwt = 0.22) higher in French literacy and 0.30 of an ASER level (dwt = 0.24) higher in math compared to control group students in the same school in unadjusted models (0.19 (dwt = 0.26) and 0.27 (dwt = 0.22), respectively in the covariate-adjusted models). However, assignment to HCT did not significantly impact students’ school grades.

In HCT+ Act schools, students assigned to the treatment scored 0.24 higher of an ASER level (dwt = 0.26) in French literacy and 0.35 of an ASER level (dwt = 0.28) higher in math in the unadjusted models (0.21 (dwt = 0.23) and 0.30 (dwt = 0.25), respectively, in covariate-adjusted models). Controlling for baseline covariates, including ASER baseline literacy and math scores, we also find a positive impact of HCT+ Act on school grades; HCT+ Act students received an average of 0.29 of a point higher school grades (dwt = 0.16) than control group students in the same schools.

Impacts of HCT+ Act Compared to HCT

The addition of skill-targeted SEL activities to the tutoring program had positive impacts on students’ school grades () above and beyond access to HCT alone. Students who were offered the additional SEL programming, where skill-targeted SEL activities (Mindfulness, Brain Games) were implemented during subject transitions of the “base” HCT programming, received 0.42-point higher school grades on average (dwt = 0.25) at the end of the school year (0.38 point (dwt = 0.21) higher when adjusting for baseline covariates). However, there was no detectable differences between HCT+ Act and HCT in students’ French literacy or math scores.

Table 4. SEL activities impacts on ASER French, Math, and average school marks.

These findings are robust across various alternative model specifications, including multi-level modeling, models with additional school characteristics as covariates (student-to-classroom ratio, student-to-teacher ratio, % of classrooms with permanent structure, school-average teacher attendance to the regular schooling), and multi-variate models accounting for the covariance across the three outcomes. We present the results from the most parsimonious and easily interpretable models as final here.

Local Average Treatment Effects of HCT Programs

The IV results suggest that higher attendance in the HCT program led to a significant gain in students’ French literacy and math performance, with effect sizes (dwt) ranging 0.39–0.45 for literacy and 0.43–0.38 for math, with and without covariate adjustment (). However, attendance to the HCT program did not have an effect on students’ school grades.

Table 5. Local average treatment effects of HCT and HCT + Act.

Attendance to the HCT+ Act program (with the addition of skill-targeted SEL activities) led to significant improvement in not only French literacy by 0.35 and 0.38 (effect sizes 0.38 and 0.43) and math by 0.50 and 0.52 on the ASER test (effect sizes 0.46 and 0.40) with or without covariate adjustment, but also in school grades by 0.47 point (effect size = 0.38) when baseline covariates are considered.

HCT and HCT+ Act Impact Variation

Across all outcomes, the impacts of HCT and HCT+ Act programs, and additional impacts of HCT+ Act compared to HCT alone, did not vary significantly by students’ gender, grade level, refugee status, or baseline ASER French and Math scores, suggesting the positive impacts of HCT and HCT+ Act programs are consistent across all eligible children. See – for unadjusted and covariate adjusted estimates.

Discussion

This study evaluated the impact of an NGO-provided, remedial tutoring program–Tutoring in a Healing Classroom (HCT)–on academic outcomes and added impacts of Tutoring in a Healing Classroom + skill-targeted SEL activities (HCT+ Act) for public school students in the Diffa region of Niger. The evidence of effectiveness of this program provides support for the potential of remedial academic programming, in conjunction with formal schooling, as a feasible method of increasing student achievement in low-income and conflict-affected contexts. By providing an effective method of increasing student academic achievement through additional academic and social-emotional support (over and above regular, formal schooling) in low-income and conflict-affected contexts, this study extends the emerging evidence on viable policies and strategies to improve quality of education in conflict affected, sub-Saharan Africa. As an NGO-implemented program, it also highlights the potential of collaboration between government and non-governmental sectors to provide students with higher quality education.

After 22 weeks, we find that students who had access to 4 h of HCT programming alone per week (over and above access to 28 h of public schooling) showed significantly higher improvement in their French literacy and math performance, compared to students in the business-as-usual condition (28 h per week of public schooling only) in the same schools. In addition, the combination of HCT programming and skill-targeted SEL activities had positive impacts on all three measured academic outcomes—French literacy, math, and average school grades. Furthermore, we found these impacts were robust across subgroups of children (gender, grade, refugee status, etc.) and across different specifications of the model. This study adds to the current literature by providing clear evidence that SEL-infused remedial support can improve student learning outcomes in low-income, high-conflict regions. In addition, the treatment on the treated impacts on the academic outcomes revealed that children who attended at higher rates showed higher levels of literacy and numeracy competence, suggesting the impact of the HCT has a positive dose/response gradient.

Over and above the positive impacts of HCT, we observed additional impact of skill-targeted SEL activities (HCT+ Act)–specifically, Brain Games and Mindfulness, focused on executive function and stress regulation–on students’ public school grade averages but not on their French literacy and math performance. Given the same academic instruction (HCT) was provided in both tutoring conditions, along with the relatively small treatment contrast, it may not be surprising to see null effects on academic performance. However, the positive impacts of HCT+ Act on school grades is promising. Academic skills and grades are positively correlated, but are nonetheless independent constructs of educational progress (Bowers, Citation2011; Brennan et al., Citation2001). School grades often reflect not only students’ knowledge and skills but also the teacher’s assessment of students’ global functioning in school settings, including non-cognitive skills and attitudes, such as academic behavior, motivation, perseverance, study habits, and time management skills (Bowen et al., Citation2009; Brophy, Citation1983; Farrington et al., Citation2012; Smith, Citation2005). Because the remedial tutoring in this study was implemented in partnership with the Ministry of Education at public schools (outside of formal school hours), there is some overlap between students’ tutors and public school teachers. (Unfortunately, we were unable to measure the exact degree of overlap because of challenges with Niger’s administrative data systems.) This overlap is estimated to be small due to two primary factors: First, school directors nominated a pool of tutoring teachers from available teachers within their schools. In general, teachers perceived to be more skilled and/or better prepared are placed in older grades (i.e. 4th–6th), and were overrepresented in both nominations and tutors. Second, the public school grades are an average of 10 subjects, at least some of which are assigned by different teachers.

However, we acknowledge two potential threats to internal validity: First, tutoring teachers who received HCT and SEL activity trainings could have adopted and implemented the instructional and SEL practices they learned in the public school classroom teaching (within-school spillover). If this were the case, the potential spillover of teacher practice to control students would attenuate the impacts of the programming by improving control students’ outcomes. That is, our findings may be conservative estimates, and the true impact of the HCT and HCT+ Act programming may be larger than reported.

Second, students’ treatment condition was likely known by at least some teachers in the school, potentially influencing teachers’ perceptions of those students and therefore the school grades they assigned for students who attend tutoring classes. In this case, the impacts on school grades would likely be an overestimate or false positive impacts. However, we believe this concern is an unlikely threat, because we only see a within-school impact in the HCT+ Act treatment condition. If we thought that the identification of who was selected (or not) for tutoring changed teachers’ grades or expectations in ways that affected grades, we would expect to see the same effect in both HCT and HCT+ Act conditions. The null finding in school grades in the HCT schools suggest that the positive impact on school grades we found in within-school comparison in the HCT+ Act schools is not a product of teacher bias due to their knowledge of treatment status; instead it represents the true impact of added SEL activities. This interpretation is further supported by the findings from the between-school treatment contrast, HCT vs. HCT+ Act, where we find the positive impact of the added SEL activities on school grades again. Given this, we believe the impacts of SEL activities we found in school grades are robust estimates of real impact rather than a product of a teacher bias.

Last, we also note for this finding that the increased precision obtained by adding covariates makes the impact on grades more significant. Given the baseline imbalance by grade level, This could plausibly be due to imbalance in baseline covariates. However, we empirically tested the impact variation by grade level and do not observe a statistically significant difference. Therefore, we conclude the estimates reported are the most precise.

In addition to these limitations, we note that the HCT condition contained four additional hours of instruction per week compared to the public school only condition and may differ in important ways from other remedial tutoring programs. For example, HCT infuses academic instruction with climate-targeted social and emotional practices, and teachers are given ongoing professional development, which may not be provided in other remedial tutoring programs. Furthermore, with the exception of the addition of skill-targeted SEL activities—which allowed for 90 additional minutes per week of active student engagement with instructors—we cannot be sure which programmatic component, or combination thereof, produced the results of this study. We therefore caution that these results should not be extrapolated beyond HCT and/or HCT+ Act in Niger.

We also note that the SEL programming in Healing Classrooms was designed to be universal—that is, to be applicable for and implemented with all students—and thus to promote skills that can support students to navigate challenging emotions and/or environments. However, the programming was not designed to support children with major mental health challenges; more specialized screening practices and tiered mental health support would likely be needed to support those students.

Last, we find that there was no significant impact variation on students’ academic outcomes by gender, grade level, refugee status, or baseline ASER French and Math scores. We find this notable, given that prior studies on remedial learning have not demonstrated impact on the most marginalized populations such as girls and low-achieving students (Agostinelli et al., Citation2018; Saavedra et al., Citation2019). These findings suggest that HCT and HCT+ Act can be implemented without a prior expectation of disadvantaging certain groups of students.

Despite the promising impacts, however, the findings must be interpreted within the context of the goal of remedial education. While program impacts were sizable, with effect sizes comparable to those reported in singular studies (e.g., Agostinelli et al., Citation2018; Banerjee et al., Citation2007) and larger than those reported in meta-analyses (e.g. Ganimian & Murnane, Citation2016) the “average” child in both treatment conditions remained eligible for the remedial tutoring program (ASER scores less than or equal to Level 2) after 1 year of participation. Therefore, access to 4 h per week of additional academic support was not sufficient to help students “test out” of the eligibility criteria (i.e., reading a short paragraph in the language of instruction and solving simple subtraction problems).

It is also important to interpret the intent-to-treat estimates alongside the many program implementation challenges: an unpredictable security situation, population mobility, seasonal migration, and public school teacher strikes anecdotally contributed to less than desirable attendance rates at the tutoring sessions. In fact, local average treatment effects from this study suggest that had the treatment children received the full intended dosage, the average student would no longer be eligible for the tutoring program in math by the end of the school year. Given these contextual considerations, more intensive remedial academic programming, with effective implementation strategies that can help address barriers to attendance and participation, may be needed to help equip children with the knowledge and skills to learn their grade-appropriate curriculum in formal schooling classrooms.

Taken together, the results of this impact evaluation suggest that a hybrid model that combines remedial programming delivered by NGOs and government-run formal schooling holds promise in low-income and conflict-affected countries to enhance students’ literacy, numeracy, school grades–and perhaps social-emotional learning–via SEL-infused programming. Such a model may: bolster government-provided education in times of crisis; target students with different academic or psychosocial needs; and/or serve as a short-term transitional model to government-run remedial programming for low-income and conflict-affected countries. However, the findings also suggest that such promise has not been fully realized. For such a program to successfully support academically-struggling students in their formal schooling, NGOs and donors should invest in testing different approaches to the program and implementation designs to identify which approaches can deliver not only statistically significant findings but also practically meaningful improvement in children’s learning outcomes. Ultimately, the responsibility and authority to educate children resides with the government. However, NGOs are well-positioned to temporarily assist and supplement public school education in situations where economic and security conditions may seriously constrain government’s ability to do so. If properly aligned at policy and curricular levels, governments and NGOs working together can enhance the learning and development of students prior to the existence of the necessary security and economic conditions required for governments to do so alone. Through these forms of programming, NGOs and international funders can help build the capacity of governments to provide quality education that promotes learning for all children.

This study also suggests several important areas for future research. First, the positive impacts of additional skill-targeted SEL activities on school grades suggest several potential mechanisms by which educational programming can improve students’ academic outcomes. For example, it is possible the impact of SEL activities on grades is because SEL activities improved children’s stress regulation and executive function, which in turn improved students’ classroom behaviors and academic engagement, resulting in higher average grades. However, we note here that this study does not have direct measures of SEL outcomes and thus, our design does not permit us to formally examine this hypothesis. Future studies examining mechanisms of the impact will provide valuable information for identifying targets of intervention and needs for additional support when such programs are implemented.

Second, the low attendance and resulting low dosage reported in our study is rather typical in studies in low-income and conflict-affected contexts (e.g., Banerji & Khemani, Citation2010; Tubbs Dolan et al., Citation2022). Identifying contextual and individual constraints on attending supplemental education programs and implementing and testing strategies to increase attendance will likely contribute to increasing effectiveness. Finally, replication studies of the effectiveness of supplemental education programs such as the HCT and HCT+ Act programs tested here in different contexts is needed to build a robust evidence base. The evidence generated from this study is limited to a unique country and region, with unique populations and histories. Future replication studies will strengthen the evidence for effective strategies to achieve the goal of providing quality education, as laid out in UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in low-income, conflict-affected contexts where already-fragile public schooling systems and under-prepared and supported teachers are overwhelmed by displaced populations. Future research may also explore how robust the programmatic model is to implementation by the government and under what conditions.

This study’s findings make a timely contribution to the emerging body of knowledge on the effectiveness of educational programs in humanitarian contexts, especially given the staggering increase of students whose learning has been interrupted—or further interrupted—due to the global pandemic caused by COVID-19. Beyond the pandemic, the study speaks to increased attention to issues of school quality over and above access and the recent doubling of men, women, and children suffering forced displacement (UNHCR, Citation2020). The Agency for Fundamental Rights (FRA) has warned that without access to education, among other supports, the global community risks losing an entire generation of human capital and potential to issues of poverty, exclusion, and displacement (FRA, 2019). The results reported in this article help inform the emerging global agenda on improving the quality of education in low-resource and conflict-affected countries to help ensure high-quality education for all.

Open Research Statements

Study and Analysis Plan Registration

The study and analysis plan are registered on the American Economic Association’s registry for randomized controlled trials: https://doi.org/10.1257/rct.2125

Data, Code, and Materials Transparency

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, via the dataverse link. The data are not publicly available due to the protection of participants that could compromise the safety of research participants. Data set may be requested from: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/TVXIEW

Design and Analysis Reporting Guidelines

This manuscript was not required to disclose use of reporting guidelines, as it was initially submitted prior to JREE mandating open research statements in April 2022.

Transparency Declaration

The lead author (the manuscript’s guarantor) affirms that the manuscript is an honest, accurate, and transparent account of the study being reported; that no important aspects of the study have been omitted; and that any discrepancies from the study as planned (and, if relevant, registered) have been explained.

Replication Statement

This manuscript reports an original study.

Open Scholarship

This article has earned the Center for Open Science badges for Preregistered through Open Practices Disclosure. The materials are openly accessible at https://www.socialscienceregistry.org/trials/2125.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (89.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The research reported here would not be possible without the dedication, commitment, and good will of key collaborating organizations and individuals. We wish to thank: The International Rescue Committee, especially its Education Unit and Research, Evaluation and Learning Unit in New York City, and education, research, and monitoring-and-evaluation staff in Niger. Jeannie Annan, Sarah Smith, Jennifer Sklar, Erick Ngoga, Autumn Brown, and Kiruba Murugaiah, played particularly integral roles. We also wish to thank colleagues at New York University’s research center, Global TIES for Children, especially our dedicated data team for their diligence and support and Alejandro Ganimian for his thoughtful review of a prior version of this article. Dubai Cares provided generous direct financial support for program and research in Niger, without which this article would not be possible. We’d especially like to thank the children of Diffa, along with their parents, teachers and communities, for allowing us to engage them in this work.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aber, J. L., Dolan, C. T., Kim, H. Y., & Brown, L. (2021). Children’s learning and development in conflict-and crisis-affected countries: Building a science for action. Development and Psychopathology, 33(2), 506–521. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579420001789

- Aber, J. L., Torrente, C., Starkey, L., Johnston, B., Seidman, E., Halpin, P., Shivshanker, A., Weisenhorn, N., Annan, J., & Wolf, S. (2017). Impacts after one year of “Healing Classroom” on children’s reading and math skills in DRC: Results from a cluster randomized trial. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 10(3), 507–529. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2016.1236160

- Accelerated Education Working Group (AEWG). (2017). The case for accelerated education. Education in Conflict and Crisis Network/USAID. Retrieved June 7, 2020, from https://www.eccnetwork.net/resources/case-accelerated-education.

- Agostinelli, F., Avitabile, C., Bobba, M., & Sanchez, A. (2018). The short-term effects of the mobile pedagogical tutors: Evidence from a randomized control trial in rural Mexico. Mimeo.

- Banerjee, A. V., Cole, S., Duflo, E., & Linden, L. (2007). Remedying education: Evidence from two randomized experiments in India. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 122(3), 1235–1264. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.122.3.1235

- Banerji, R., Bhattacharjea, S., & Wadhwa, W. (2013). The annual status of education report (ASER). Research in Comparative and International Education, 8(3), 387–396. https://doi.org/10.2304/rcie.2013.8.3.387

- Banerji, R., & Khemani, S. (2010). Pitfalls of participatory programs: Evidence from a randomized evaluation in education in India. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2(1), 1–30.

- Benjamini, Y., Krieger, A. M., & Yekutieli, D. (2006). Adaptive linear step-up procedures that control the false discovery rate. Biometrika, 93(3), 491–507. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/93.3.491

- Blair, C. (2010). Stress and the development of self-regulation in context. Child Development Perspectives, 4(3), 181–188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2010.00145.x

- Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78(2), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x

- Bowen, W. G., Chingos, M. M., & McPherson, M. S. (2009). Crossing the finish line: Completing college at America’s public universities. Princeton University Press.

- Bowers, A. J. (2011). What’s in a grade? The multidimensional nature of what teacher-assigned grades assess in high school. Educational Research and Evaluation, 17(3), 141–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/13803611.2011.597112

- Brennan, R., Kim, J., Wenz-Gross, M., & Siperstein, G. (2001). The relative equitability of high-stakes testing versus teacher-assigned grades: An analysis of the Massachusetts Comprehensive Assessment System (MCAS). Harvard Educational Review, 71(2), 173–217. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.71.2.v51n6503372t4578

- Brophy, J. E. (1983). Research on the self-fulfilling prophecy and teacher expectations. Journal of Educational Psychology, 75(5), 631–661. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.75.5.631

- Carneiro, P., Crawford, C., & Goodman, A. (2007). The impact of early cognitive and non-cognitive skills on later outcomes. CEE DP 92. Centre for the Economics of Education (NJ1).

- CASEL. (2021). Evidence-based social and emotional learning programs: CASEL criteria updates and rationale. CASEL. https://casel.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/11_CASEL-Program-Criteria-Rationale.pdf

- Chekaraou, I., & Goza, N. A. (2015). Niger: Trends and futures. Education in West Africa, 29, 343.

- Collaborative for Social and Emotional Learning (CASEL). (2015). 2015 CASEL guide: Effective Social and emotional learning programs: Middle and high school edition. CASEL. http://secondaryguide.casel.org/casel-secondary-guide.pdf

- Cowen, E. L., Wyman, P. A., & Work, W. C. (1996). Resilience in highly stressed urban children: concepts and findings. Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 73(2), 267–284.

- Dryden-Peterson, S. (2010). Barriers to accessing primary education in conflict-affected fragile states: Literature review. International Save the Children Alliance.

- Duflo, A., Kiessel, J., & Lucas, A. (2020). Experimental evidence on alternative policies to increase learning at scale (No. w27298). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta‐analysis of school‐based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

- Farrington, C. A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Keyes, T. S., Johnson, D. W., & Beechum, N. O. (2012). Teaching adolescents to become learners: The role of noncognitive factors in shaping school performance--a critical literature review. Consortium on Chicago School Research.

- Filmer, D., Langthaler, M., Stehrer, R., & Vogel, T. (2018). Learning to realize education’s promise. In World development report. The World Bank.

- Finch, J. E., & Obradović, J. (2017). Unique effects of socioeconomic and emotional parental challenges on children’s executive functions. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 52, 126–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.07.004

- Fundamental Rights Report. (2019). European Union Agency for fundamental rights (FRA). FRA.

- Ganimian, A. J., & Murnane, R. J. (2016). Improving education in developing countries: Lessons from rigorous impact evaluations. Review of Educational Research, 86(3), 719–755. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654315627499

- Gelman, A., Hill, J., Su, Y. S., Yajima, M., Pittau, M., Goodrich, B., & Goodrich, M. B. (2015). Package ‘mi’. R CRAN.

- Hackman, D. A., Gallop, R., Evans, G. W., & Farah, M. J. (2015). Socioeconomic status and executive function: Developmental trajectories and mediation. Developmental Science, 18(5), 686–702. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12246

- Hart, R. (2009). Child refugees, trauma and education: Interactionist considerations on social and emotional needs and development. Educational Psychology in Practice, 25(4), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667360903315172

- Heckman, J. J., & Rubinstein, Y. (2001). The importance of noncognitive skills: Lessons from the GED testing program. American Economic Review, 91(2), 145–149. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.91.2.145

- Hedges, L. V. (2009). Effect sizes in nested designs. In The Handbook of Research Synthesis and Meta-Analysis, 2, 399–416.

- Holmes, J., Gathercole, S. E., & Dunning, D. L. (2010). Poor working memory: Impact and interventions. In Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 39, pp. 1–43). JAI.

- Human Rights Watch (2016). “Growing up without an education”: Barriers to education for Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. HRW.

- Imai, K., King, G., & Nall, C. (2009). The essential role of pair matching in cluster-randomized experiments, with application to the Mexican universal health insurance evaluation. Statistical Science, 24(1), 29–53. https://doi.org/10.1214/08-STS274

- Jha, A. P., Krompinger, J., & Baime, M. J. (2007). Mindfulness training modifies subsystems of attention. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 7(2), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.7.2.109

- Jones, S. M., & Bouffard, S. M. (2012). Social and emotional learning in schools: From programs to strategies and commentaries. Social Policy Report, 26(4), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2379-3988.2012.tb00073.x

- Jones, S., Brush, K., Bailey, R., Brion-Meisels, C., McIntyre, J., Kahn, J., Nelson, B., & Stickle, L. (2017). Navigating social and emotional learning from the inside out: Looking inside and across 25 leading SEL programs: A practical resource for schools and OST Providers (Elementary School Focus). Harvard Graduate School of Education. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/pages/navigating-social-and-emotional-learning-from-the-inside-out.aspx

- Kim, H. Y., Brown, L., Dolan, C. T., Sheridan, M., & Aber, J. L. (2020). Post-migration risks, developmental processes, and learning among Syrian refugee children in Lebanon. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 69, 101142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2020.101142

- Lawson, G. M., Hook, C. J., & Farah, M. J. (2018). A meta‐analysis of the relationship between socioeconomic status and executive function performance among children. Developmental Science, 21(2), e12529. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12529

- Lu, B., Greevy, R., Xu, X., & Beck, C. (2011). Optimal nonbipartite matching and its statistical applications. The American Statistician, 65(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.1198/tast.2011.08294

- McEwan, P. J. (2015). Improving learning in primary schools of developing countries: A meta-analysis of randomized experiments. Review of Educational Research, 85(3), 353–394. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314553127

- Meier, M. (2017). Adaptive humanitarian programming in Diffa. Humanitarian Exchange Magazine. Overseas Development Institute Humanitarian Practice Network. Retrieved September 4, 2019, from https://odihpn.org/magazine/adaptative-humanitarian-programming-in-diffa-niger/

- Mendenhall, M., Russell, S. G., & Buckner, E. (2017). Urban refugee education: Strengthening policies and practices for access, quality, and inclusion. Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Miller, K. E., & Rasmussen, A. (2010). War exposure, daily stressors, and mental health in conflict and post-conflict settings: Bridging the divide between trauma-focused and psychosocial frameworks. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 70(1), 7–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.09.029

- Ministere de l’Enseignement Primaire (2013). Programme Sectoriel de l’Education et de la Formation (2014–2024). Niamey.

- PASEC (2015). PASEC 2014 education system performance in Francophone sub-Saharan Africa. PASEC.

- PASEC (2016). PASEC 2014: Performances du système éducatif Nigérien. PASEC.

- Reed, R. V., Fazel, M., Jones, L., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in low-income and middle-income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379(9812), 250–265. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60050-0

- Roberts, G., Quach, J., Gold, L., Anderson, P., Rickards, F., Mensah, F., Ainley, J., Gathercole, S., & Wake, M. (2011). Can improving working memory prevent academic difficulties? A school based randomised controlled trial. BMC Pediatrics, 11(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-11-57

- Roy, A. L., McCoy, D. C., & Raver, C. C. (2014). Instability versus quality: Residential mobility, neighborhood poverty, and children’s self-regulation. Developmental Psychology, 50(7), 1891–1896. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036984

- Saavedra, J. E., Näslund-Hadley, E., & Alfonso, M. (2019). Remedial inquiry-based science education: Experimental evidence from Peru. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 41(4), 483–509. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373719867081

- Sauer, S., Lemke, J., Wittmann, M., Kohls, N., Mochty, U., & Walach, H. (2012). How long is now for mindfulness meditators? Personality and Individual Differences, 52(6), 750–754. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.12.026

- Schwartz, A. C. (2012). Remedial education programs to accelerate learning for all. World Bank.

- Shanks, T. R. W., & Robinson, C. (2013). Assets, economic opportunity and toxic stress: A framework for understanding child and educational outcomes. Economics of Education Review, 33, 154–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2012.11.002

- Smith, J. K. (2005). Reconsidering reliability in classroom assessment and grading. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 22(4), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2003.tb00141.x