ABSTRACT

Recent decades have seen a significant rise in interest in spirituality in different mental health contexts. A comprehensive systematic review by Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (2019) shows that a gap exists between professionals and service users in the value they place on spirituality. The aim of this article is to synthesize existing literature on how people with mental health issues experience spirituality as a resource. A systematic literature search was performed in four international databases between January 2019 and October 2022. Nine studies were selected. This synthesis resulted in three themes, longing for connection, the need for vital relationships, and searching for a new meaning.

Introduction

Spirituality is a globally acknowledged, yet complex, concept that has attracted increasing attention over recent decades (Cook, Citation2020; Koenig, Citation2009; Swinton, Citation2001; Verghese, Citation2008). However there exists no universal definition (Bonelli & Koenig, Citation2013; Koenig, Citation2013; Koslander, Rönning, Magnusson, & Wiklund Gustin, Citation2021; Sperry & Shafranske, Citation2005). Spirituality comes from the term spirit, and has been described as a vital essence and a powerful source to meaning and purpose in life, which is closely connected to the body, expressed through emotions, feelings, behavior, and relationships (Benner, Citation2011; Cook, Citation2020; Koenig, Citation2009; Miller & Thoresen, Citation2003). Spirituality is usually defined as a meaningful system which helps a person to find values, aims and connections in life (Cook, Citation2004, Citation2020; Koenig, Citation2009; Swinton, Citation2020a).

The concept of spirituality is expressed in both secular and religious traditions, which suggests that humans can be religious but not aware of their personal spirituality, or spiritual but not religious (Elkins, Hedstrom, Hughes, Leaf, & Saunders, Citation1988; Helminiak, Citation2001; Koenig, Citation2009; Moberg, Citation2002). Some scholars view spirituality as a human phenomenon, a natural part of life, independent of personal religion or belief in God (Helminiak, Citation2001), while others emphasize a humanistic and phenomenological perspective on spirituality outside traditional religion. Such a perspective highlights spirituality as a dimension of human experience that relates to values, attitudes, emotions, and beliefs. Spirituality is also expressed as a way of being and experiencing through awareness of a transcendent dimension characterized by values in regard to self, others, nature, life and what humans consider to be “the ultimate” (Elkins, Hedstrom, Hughes, Leaf, & Saunders, Citation1988; Miller & Thoresen, Citation2003).

Swinton (Citation2020b) offers three different lenses through which spirituality might be “experienced,” as opposed to defined. These are a religious lens, a biological lens, and a generic lens, which views spirituality as personal and diverse processes. Spirituality refers to ideas, concepts, attitudes, and behaviors that derive from a person’s interpretation of their experiences of the spirit (Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams, & Slade, Citation2011). Researchers in mental health have refined the multiple aspects of spirituality as three key elements: meaning, connection and transcendence (Murgia, Notarnicola, Rocco, & Stievano, Citation2020; Weathers, McCarthy, & Coffey, Citation2016).

The recovery approach in mental health identifies spirituality as a vital element in enabling clients to rebuild a meaningful life by finding motivational and hopeful strategies (Allott et al., Citation2020; Cook, Citation2020; Koenig, Citation2009; Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams, & Slade, Citation2011). There is an increasing recognition that, irrespective of their personal viewpoint on spirituality, staff have a duty to clients to take this aspect of their lives seriously (Clarke, Citation2010; Cook & Grimwade, Citation2021). In the context of acute mental health care, this means to no longer dismiss the spiritual content of psychotic communication as merely “illness,” but a framework to understand the experiences of the client (Clarke, Citation2010).

This article emphasizes the paradigm shift of recent decades, viewing mental health issues in a holistic framework, highlighting the spiritual domain as of crucial importance of those struggling with mental health difficulties. In mental health care, research is producing evidence that it is important to develop new, more respectful and less stigmatizing ways of helping clients. The research points to a new and more creative conceptualization and attitude which can pave the way for a new and broader understanding of how to enable helpful relationships in in- and out-patient facilities. Attitudes in mental health care have changed toward greater acceptance of the spiritual and religious concerns of patients, underlining the importance of spirituality as an essential element of life (Koenig, Koenig, King, & Carson, Citation2012). To suggest that human beings have a spirit presupposes that they are creatures who require more than basic needs to achieve health and well-being, and that issues of meaning, hope, purpose, and transcendence are not secondary to care but in fact a fundamental part of it (Frankl, Citation1984). If human beings are whole persons and if mental health issues affect every aspect of the person, spiritual care on its own will not be enough. Yet neither will pharmacological or psychotherapeutic interventions be sufficient to meet the needs of the whole person (Clarke, Citation2010). What will be required is a multidisciplinary approach that uses constructive dialogue to develop ways of caring that acknowledge and reach out to the whole person, including those more mysterious and less tangible aspects that emerge from reflection on the human spirit (Swinton, Citation2001).

An important development in mental health has been to focus on the lived experiences and personal stories of clients to promote holistic and person-centered care (Cook, Powell, & Sims, Citation2016; Leamy, Bird, Le Boutillier, Williams, & Slade, Citation2011; Slade et al., Citation2012). Study findings also underline the need for incorporating people`s spiritual experiences as vital themes during treatment and hospitalization (Grimwade & Cook, Citation2019; Koslander, Rönning, Magnusson, & Wiklund Gustin, Citation2021). Within the recovery approach, aspects like meaning, hope, connection, and identity are vital and viewed as key concepts in understanding and finding motivation to cope with mental health difficulties (Cook, Citation2020; Koenig, Citation2013; Pargament, Citation2013). The systematic review by Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) indicates the importance of mental health professionals being prepared to support the spiritual dimension in holistic terms, underlining the need for future research on spirituality. The present systematic review is an important contribution to the subject, providing evidence of the significant role spirituality plays in the lives of mental health clients. The systematic review by Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) provided guidelines for the search in this synthesis. The aim of the present synthesis was to examine recently published qualitative literature focusing on the first-person perspective on spirituality as a resource in mental health. In this sense, this synthesis is an extension of the systematic review by Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019).

The aim of this article is thus to synthesize existing literature and gain insight into published qualitative research that promotes the subjective voices of spiritual experiences of people with mental health issues. The research question is: How can spirituality be experienced as a resource in mental health care?

There exists no universal definition of the term spirituality (Koenig, Citation2013), which makes it complicated to perform database searches. To address the broad scope in this synthesis, terms such as spiritual/spirituality, religion/religious, faith/belief systems, and existential were included in the database searches.

Methods

A synthesis of qualitative studies aims to provide a coherent overview of the literature on a chosen topic that is both faithful to the primary studies and distinct in offering a more comprehensive interpretation (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2002). A synthesis goes beyond the primary studies and represents a stage of interpretation whereby reviewers generate new interpretative constructs. Here, the thematic synthesis approach (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) is used, which is specifically designed for bringing together and integrating the findings of qualitative systematic reviews. The reporting of this synthesis adheres to the “enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research” (ENTREQ) statement (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, Citation2012). A review protocol was pre-registered in OSF (open science framework).

The search involved a preplanned sensitive search strategy that combined search terms relating to the experiences of patients and clients in the context of mental health. The objective was to search for all available studies in each database. In close collaboration with a university librarian, the first author conducted a comprehensive systematic search, using four international multidisciplinary databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Scopus and Atla.) Following the SPIDER structure, keywords such as mental health care/mental health patients, spirituality/spiritual perspectives/experiences, and recovery were included. Suitable synonyms and subject headings were entered individually and in combination, in full spelling and truncated. The searches were limited to qualitative studies.

Newman and Gough (Citation2020) highlight the importance of reviewers including studies in a systematic and transparent way. Inclusion and exclusion criteria ensure the transparency of the selection processes. These criteria are shaped by the review question. Please see . This synthesis of qualitative studies included studies published from January 2019 to October 2022. This eligibility criterion was based on the comprehensive qualitative systematic review exploring the experiences of spirituality among adults with mental health difficulties, which was the first of its kind (Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, & Slade, Citation2019). This systematic review searched for studies published between 2000 and 2018, in seven electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, AMED, ASSIA, Cinahl, Atla, and Web of Science).

Table 1. Eligibility criteria.

Data sources

A systematic search was conducted in four interdisciplinary international databases. The databases selected are considered fruitful for investigation of human phenomena in medical and psychological fields, and for searches for peer-reviewed articles. Two librarians were consulted for help and advice, and for the choice of the databases. The databases selected were Scopus, MEDLINE, PsycINFO and Atla. Cinahl could have been considered relevant, but its tendency to focus on nursing was viewed as of less relevance. Scopus is a comprehensive, important multidisciplinary database that contains information about peer-reviewed literature. Scopus is a citation and abstract database with direct links to full text. It covers a wide variety of subjects in e.g., medicine, social sciences, and humanities. MEDLINE is the National Library of Medicine’s premier bibliographic database, containing more than 29 million references to journal articles in life sciences with a focus on biomedicine. A distinctive feature of MEDLINE is that the records are indexed with the National Library of Medicine’s Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). PsycINFO has been the most trusted index of psychological science in the world. With more than five million interdisciplinary bibliographic records, the database provides targeted discovery across the full spectrum of behavioral and social sciences. The researchers wanted to examine peer-reviewed articles in these fields to gain insight into the experienced lifeworld of people diagnosed with mental health issues. This highlights the combination of two different views: the traditional medical perspective, which is often associated with the field of psychiatry, and the subjective lifeworld approach, which is usually associated with the phenomenological tradition. We wanted to search for qualitative articles based on the first-person perspective of mental health clients in the fields of psychology and psychiatry. The Atla Religion Database is the premier index of articles, reviews, and essays in all fields of religion and theology, and offers significant breadth and depth in the subject areas and languages covered. We performed a search in Atla to explore studies in the field of theology and religion. However, no references were considered relevant.

The references selected were as follows:

Scopus: 319 references screened

MEDLINE: 1215 references screened

PsycINFO: 97 references screened

Atla RDB: 0 references

The database searches were conducted with librarians on 13–14 (PsychINFO) and 20 (Scopus and MEDLINE) October 2022. Due to the differences in the construction of each database, the search strings were identified in unique ways. Searching gray literature was considered irrelevant, because we were only interested in peer-reviewed articles.

Attachment 1

The SPIDER tool

Attachment 2

Electronic search strategies:

Search string, Scopus, 20 October 2022

319 references

Delimitations: English, 2019–2022, NOT cancer patients*

Search string, PsycINFO, 13 and 14 October 2022

97 references

APA PsycINFO <2002 to October Week 3 2022>

exp Affective Disorders/ 122964

exp Schizophrenia/ 57609

exp Psychosis/ 74692

exp Psychiatric Patients/ 7783

exp Bipolar Disorder/ 24771

exp Anxiety Disorders/ 38196

exp Personality Disorders/ 19241

exp Mental Disorders/ 643920

exp major depression/ 115716

(trauma and stressor related disorder).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] 35

(Affective Disorder* or Schizophrenia or Psychosis or Psychoses or Psychotic or Psychiatric Patient* or Bipolar Disorder* or Anxiety Disorder* or Personality Disorder* or Mental Disorder* or major depression or mental health disorder* or mental illness or Psychiatric disorder*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] 390201

exp Spirituality/ 17399

exp Faith/or exp Faith Healing/ 4163

exp religious experiences/ 867

(spiritual* or transcenden* or faith* or belief* or belief system*).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] 156173

exp Religious Beliefs/ 28601

exp Existentialism/ 1953

exp Mysticism/ 694

exp Asceticism/ 60

(“religious belief*” or existential* or mystic* or Ascetic* or self-transformation or self transformation).mp. [mp=title, abstract, heading word, table of contents, key concepts, original title, tests & measures, mesh word] 22552

12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 or 17 or 18 or 19 or 20 176,358

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 10 or 11 717,652

exp Hospitalized Patients/ 7833

(Hospitalized Patient* or inpatient*).mp. 38061

23 or 24 38,061

22 and 25 22,568

21 and 26 618

limit 27 to (English and yr=“2019-Current”) 97

Search string, MEDLINE, 20 October 2022

1209 references

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process, In-Data-Review & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions <1946 to October 19, 2022>

exp Affective Disorders/ 133532

exp Schizophrenia/ 113159

exp Psychosis/ 57209

exp Bipolar Disorder/ 44304

exp Anxiety Disorders/ 88018

exp Personality Disorders/ 44355

exp Mental Disorders/ 1395748

(trauma and stressor related disorder).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] 24

(Affective Disorder* or Schizophrenia or Psychosis or Psychoses or Psychotic or Psychiatric Patient* or Bipolar Disorder* or Anxiety Disorder* or Personality Disorder* or Mental Disorder* or major depression or mental health disorder* or mental illness or Psychiatric disorder* or Psychiatric Patient* or major depression or Hospitali?ed Patient* or inpatient*).mp. 725284

exp Spirituality/ 8813

exp Faith/or exp Faith Healing/ 602

(spiritual* or transcenden* or faith* or belief*or belief system* or religious experien* or Asceticism or Ascetic*).mp. 141200

exp Religious Beliefs/ 65746

exp Existentialism/ 1968

exp Mysticism/ 434

(“religious belief*” or existential* or mystic* or Ascetic* or self-transformation or self transformation).mp. [mp=title, book title, abstract, original title, name of substance word, subject heading word, floating sub-heading word, keyword heading word, organism supplementary concept word, protocol supplementary concept word, rare disease supplementary concept word, unique identifier, synonyms] 12449

exp Inpatients/ 27967

Depressive Disorder, Major/ 36630

Psychotic Disorders/ 51022

1 or 2 or 3 or 4 or 5 or 6 or 7 or 8 or 9 or 17 or 18 or 19 1,635,755

10 or 11 or 12 or 13 or 14 or 15 or 16 195,272

20 and 21 24,975

limit 22 to (yr=“2019 -Current” and English) 4950

limit 23 to “qualitative (maximizes specificity)” 848

(qualitative stud* or qualitative research or interview*).mp. 506938

22 and 25 4144

limit 26 to (yr=“2019 -Current” and English) 979

24 or 27 1208

After four database searches were completed, six folders were created in the EndNote library, three for the first author and three for the third author (MEDLINE, Scopus and PsycINFO). Subsequently, two more folders were created in Rayyan, one for each researcher (779 references and 775 references). A complete screening was made of the references and the findings were divided between “included,” “maybe” and “excluded.” The next step was to obtain full text versions of the articles via Google Scholar. The articles that seemed to be relevant to the research question and the inclusion and exclusion criteria were printed and screened.

Study screening

To ensure relevant literature in appropriate settings, studies conducted in Global North contexts were included. It is acknowledged that findings from non-Western mental health systems do not transfer well to European settings. Studies from “low-outcome countries” were thus excluded. The patients in the included studies were 18–64 years old and were thus “adults” in health care settings. Studies on psychopathological delusions or obsessions as spiritual experiences (e.g., psychotic symptoms) were excluded. We also excluded studies reporting spiritual experiences as seen from the professional perspective or from educational contexts. Two mixed methods studies were included, but only the qualitative part. Studies written in other languages than English or Scandinavian were excluded due to the lack of resources for translation.

Screening process

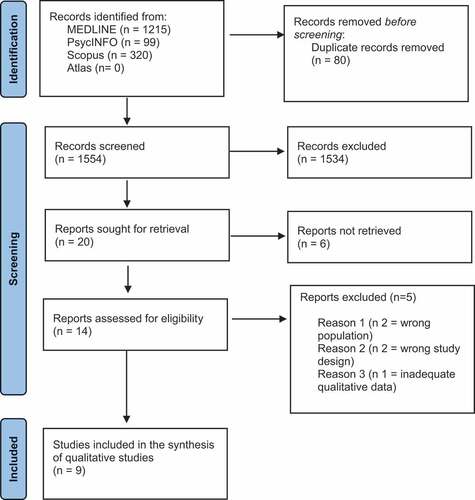

Initially, 1634 references were screened via the database search. Duplicates, literature reviews, book chapters and master`s theses were excluded. The first author and the third author reviewed independently the abstracts according to the selection criteria. Disagreement was solved by face-to-face discussions. Finally, the full text of 14 studies was read by the entire team of three researchers. They then selected nine peer-reviewed journal articles for a quality appraisal. Five studies were excluded. Please see .

Quality appraisal

The researchers independently conducted a quality appraisal of the nine studies using the CASP (critical appraisal skills program) checklist. The CASP is a clear and straightforward checklist comprising ten questions relating to the design of the studies. Any ambiguities regarding the quality of the studies were discussed within the research team until agreement was reached. No studies were excluded (defined as more than six out of ten yeses on the checklist), leaving nine studies for the final thematic synthesis, see the PRISMA flowchart.

Characteristics of the primary studies

This thematic synthesis is based on nine primary studies conducted in Australia, Canada, Egypt, the Netherlands, Scandinavia, and the USA, between 2019 and 2022. The characteristics of the studies included after screening (year of publication, country, population, number of participants, data collection, methodology, analysis, and research question) are presented in . The studies included spiritual experiences from 127 participants from in-patient and out-patient settings. All the participants had experience of mental health problems and mental health care treatment programs and/or hospitalization.

Table 2. Overview of included primary studies.

Thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) was used in this qualitative review. Thematic synthesis consists of three stages: line-by-line coding of the text, development of descriptive themes, and development of analytical themes (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). In each of the included studies, the results were extracted electronically and entered into the NVivo 12 software. The results were then coded line-by-line and converted into descriptive themes in NVivo 12 by the first author. As a first step, comparisons within and across studies were made based on preexisting concepts, while new concepts were created as descriptive themes. The descriptive themes remained close to the primary results, mainly inductively. The three authors were all involved in the final development of the analytical themes. These themes represented a stage of interpretation in which the reviewers generated new interpretive constructs. The research question was kept in mind throughout the process to guide the analysis, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. To address reflexivity and enhance the credibility and trustworthiness of the research, an audit trail and a reflexive journal were kept throughout the research process. See for the development of analytical themes.

Table 3. The thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008): development of analytical themes.

Results

The aim was to synthesize existing literature on how people living with mental health issues experience spirituality and to achieve a richer conceptual understanding of spirituality as experienced as a resource by in- and out-patients in mental health facilities. The main findings that emerged from the analysis of the included studies covered three broad themes: (1) Longing for connection, (2) The need for vital relationships, and (3) Searching for a new meaning.

Longing for connection

This theme refers to spiritual rituals and religious activities which participants utilized for support for their mental health issues. It covers experiences related to spiritual connectedness to a higher power, which gave participants guidance, feelings of support and a sense of belonging. Some participants expressed the importance of “giving my sadness over to the Lord” which felt like “a weight lifted off my shoulders” (Lee, Eads, Yates, & Liu, Citation2021, p. 547), “everything will fall onto God`s shoulder” (Chan, Lau, & Wong, Citation2020, p. 105), and “being a believer calmed me down” (Ibrahim et al., Citation2022, p. 3), all of which underline the need for a “place” to go to find inner peace, strength and understanding of one`s experiences (Jordan, Malla, & Iyer, Citation2020; Lee, Eads, Yates, & Liu, Citation2021). Participants considered their spiritual faith and religious belief to be nourishing resources for personal healing processes and a source of wisdom and knowledge (Chan, Lau, & Wong, Citation2020; Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019; Jordan, Malla, & Iyer, Citation2020; Koslander, Rönning, Magnusson, & Wiklund Gustin, Citation2021; Lee, Eads, Yates, & Liu, Citation2021; van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Schaap-Jonker, Hennipman-Herweijer, Anbeek, & Braam, Citation2019). Longing for connection highlights individual spiritual explanatory frameworks that helped participants to get a hold on their lives when experiencing mental health issues. A relationship to a Christian God or spiritual other was of crucial importance to cope.

The need for vital relationships

This theme consists of two sub-themes. First, “experiences of spiritual isolation and emptiness,” which refers to “ignored individuality” (Damsgaard, Overgaard, & Birkelund, Citation2021, p. 11) and fear of “an extra diagnosis” (van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Schaap-Jonker, Hennipman-Herweijer, Anbeek, & Braam, Citation2019, p. 45), which led to “extreme loneliness and isolation” (Damsgaard, Overgaard, & Birkelund, Citation2021, p. 11) and doubting “Am I real?” (Koslander, Rönning, Magnusson, & Wiklund Gustin, Citation2021, p. 515) during treatment. Further, this sub-theme concerns the feeling of being afflicted by a dark force under hospitalization, which underlines participants’ spiritual experiences of being neglected, misunderstood or pathologized by professionals (Damsgaard, Overgaard, & Birkelund, Citation2021; Koslander, Rönning, Magnusson, & Wiklund Gustin, Citation2021). The statements show the importance of professionals addressing a holistic perspective when engaging with in- and out-patients, and the importance of being aware of the different ways people connect with spirituality. Some experiences related to severe mental health issues may intersect with spirituality. This can result in challenging experiences or prevent the person from connecting with spirituality. Professionals must therefore be aware of such issues and interact carefully in a holistic way. Secondly, “spiritual activities as calming resources” refer to the importance of including activities that foster inner peace and resources to manage a stressful mind. Several studies show what practitioners could do to facilitate calming activities during treatment. This theme covers activities like “praying with a nurse” (van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Schaap-Jonker, Hennipman-Herweijer, Anbeek, & Braam, Citation2019, p. 45),“lighting a candle” (Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019, p. 350), “practicing meditation and yoga” (Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019, p. 349), “doing artwork” (Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019, p. 348), “find artistic expressions and communicate to others” (Koslander, Rönning, Magnusson, & Wiklund Gustin, Citation2021, p. 516), “go for a walk with someone” (Damsgaard, Overgaard, & Birkelund, Citation2021, p. 11), “getting in natural environment is great, you can smell and hear different things” (Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019, p. 347), “listening to music” (Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019, p. 350), and “engage in spiritual communities” (Jordan, Malla, & Iyer, Citation2020, p. 8; van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, Schaap-Jonker, Hennipman-Herweijer, Anbeek, & Braam, Citation2019, p. 45). This theme includes a variety of activities that helped participants to cope with their mental health difficulties when hospitalized and under treatment. The theme refers to the importance of professionals engaging in and facilitating relationships in holistic ways.

Searching for a new meaning

This theme covers statements linked to meaning making. “The need for giving back” (Lee, Eads, Yates, & Liu, Citation2021, p. 547), “being something for others” (Jordan, Malla, & Iyer, Citation2020, p. 8), “have compassion for others” (Ibrahim et al., Citation2022) and “doing some charity” (Chan, Lau, & Wong, Citation2020, p. 106) refer to acts of meaningfulness that helped participants to feel useful and have a new purpose in life (SChan, Lau, & Wong, Citation2020; Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019). To share one`s own life story in order to support others was underlined as helpful and meaningful. This indicates the importance of supporting others’ recovery when struggling with mental health issues and helping others toward understanding and explanation, which was lacking during hospitalization (Chan, Lau, & Wong, Citation2020; Ibrahim et al., Citation2022; Jones, Sutton, & Isaacs, Citation2019; Jordan, Malla, & Iyer, Citation2019). Experiences related to severe mental health disorders such as psychosis were seen as positive experiences that could provide meaningful information and a new understanding of oneself which could enable a person to help others to understand their psychotic experiences in order to recover. This indicates the importance of coming to a personal understanding of the anomalous experiences in the context of one`s psychological life and narrative (Jordan, Malla, & Iyer, Citation2019; Lee, Eads, Yates, & Liu, Citation2021). This theme covers the need for performing meaningful actions and creating a framework for life that could lead to insight, new understanding, hope, and new opportunities.

Discussion

The aim in this synthesis is to gain insight into published qualitative research that promotes the subjective voices of the spiritual experiences of people with mental health issues.

The three themes presented are summarized in the overall concept of “a sense of belonging.” The three perspectives will now be discussed in light of this concept. The first perspective concerns relationships that enhance connectedness to a larger whole. The second perspective concerns relationships with other people in holistic terms. The third perspective concerns the need to find a new meaning in life; firstly, to find acceptance for the severe mental health experiences, and secondly to be able to help others and contribute to their recovery by offering companionship.

A sense of belonging can be expressed in many ways and is linked to an experience of meaningfulness. Meaning is a basic universal need in all humans, while a lack of meaning is associated with feelings of emptiness and isolation (Frankl, Citation1984; Yalom, Citation1980). Every human being has personal sources of meaningfulness (Frankl, Citation1984), which in the context of mental health care refers to the importance of professionals facilitating relationships that can contribute to meaning making. Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) found that meaning making was one of the most prevalent themes in their study, which indicates an association between spirituality and recovery. Recovery is often defined in relation to finding meaning (Anthony, Citation1993). A sense of belonging refers to different ways people utilized personal strategies to find meaning in life, acceptance of their mental health difficulties, and strengths to hold on to as resources.

Relationships with a higher power and belief systems that underpin experiences of belonging to a larger whole support direction in life and something to hold on to. Several studies indicated that such relationships counteracted experiences of rejection, isolation, and stigmatization. The concept of faith was a resource, which refers to a form of generalized trust that facilitated openness to experiences. Spiritual practices help people strengthen their connection with spiritual lives and divine relations. Such practices are underlined as the most crucial relationship for coping with mental health issues (Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, & Slade, Citation2019). Coping was also a prevalent theme in the review of Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019), which refers to a variety of helpful spiritual practices including personal relationships to a higher power. Spiritual relationships emphasize and facilitate the development of a fundamental sense of connectedness that exists at a universal level. A sense of belonging is linked to a person’s orientation and represents the availability of a direction or purpose such as knowing the way one`s life should take, and serves as a compass for a person struggling with mental health issues (Schnell, Citation2020). Such spiritual relationships were of crucial importance in several of the studies, which is in line with the review of Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019).

Fallot (Citation2007) links belonging to finding acceptance in divine relationships. Relationships with a higher power or belief systems that underpin a sense of belonging represent resources of orientation to enhance meaningfulness. Schnell (Citation2020) exemplifies perceiving oneself as part of a larger whole and having a place in this world as responses to existential isolation (Yalom, Citation1980), and links such examples to belonging as a source of meaning. Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) emphasize spiritual relationships with God or a higher power as resources that enhance a sense of comfort, reassurance, guidance and support, which will show a positive outcome when rooted in divine relationships.

Meaningfulness is the most important dimension of a sense of coherence and refers to the extent to which a person feels that life make sense emotionally (Antonovsky, Citation1979). To help mental health clients, professionals need to facilitate and acknowledge spiritual activities that nourish a sense of belonging and provide direction when life is difficult to grasp. Meaningfulness depends on active involvement, which arises from subjective qualities of engagement and action (Schnell, Citation2020). The review of Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) points to meaning making as ways people utilized spiritual beliefs to make sense of their mental health difficulties, which coincides with the emphasis in this synthesis on such actions as resources that counteract emptiness and lack of meaning.

The above perspectives demonstrate the importance of professionals facilitating and engaging in vital relationships in holistic terms, as covered in the second theme of this synthesis. Such relationships refer to holistic care and the need for professionals to engage in the spiritual domain. Several studies indicated the need for patients to feel free to share their spiritual experiences as a key area of exploration and reflection. Such relationships counteract feelings of existential isolation (Yalom, Citation1980), as seen in several studies. The review by Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) demonstrates how people find it difficult to share spiritual experiences with professionals. Participants express frustration at contradictory explanatory frameworks and the lack of integration of their spiritual experiences when trying to make sense of their mental health difficulties. Such contradictory explanatory frameworks from professionals cause feelings of emptiness and loneliness. These perspectives call for an active focus by mental health professionals and the importance of viewing personal life stories as open systems in active interaction with the environment (Antonovsky, Citation1987). Buber (Citation1992) states that humans cannot exist without relationships and emphasizes the importance of reciprocity. In order to enable meaningful relationships, professionals must strive to be sensitive listeners (Peplau, Citation1992), which stresses a focus on the whole lived experience of mental health clients (Greenson, Citation1960; Heidegger, Citation1977, Citation1993). Also included in these perspectives is the concept of sensing, which refers to letting oneself be touched, and through being touched one can become more open to emotional possibilities (Eriksson, Citation2010; Martinsen, Citation2015). This provides access to the world and to our historical existence in its relational context (Martinsen, Citation2015). Factors such as positive regard, warmth, congruence, and empathy are essential elements in caring relationships, in which the client can feel accepted as a person of worth and feel free to express him/herself without rejection. These elements refer to relationships that may be shared intersubjectively (Schibbye, Citation2009) and may lead the person to a sense of belonging and successful coping (Antonovsky, Citation1987). The review of Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) found that genuine reciprocal relationships were essential and affected recovery processes in hospital settings.

Meaningfulness also concerns activities that help mental health clients to perceive some of their problems as worthy of commitment and engagement (Antonovsky, Citation1987). This refers to activities that enhance a calm mind and a feeling of connectedness to oneself. The studies indicated that self-care practices, such as creative activities, being in nature, practicing yoga/meditation, praying, and reading religious texts were effective in calming the mind. This concurs with the review of Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019), which highlights positive outcomes such as a peaceful mind and enhanced courage when meaningful activities are performed during treatment. The need for vital relationships in holistic terms refers to the need for sharing one’s world view and faith, in religious or secular terms, and the need to practice activities that enhance a sense of belonging.

Searching for new meaning refers primarily to the client’s need to examine and reflect on spiritual experiences with professionals. Such processes are referred to as meaning making and were of crucial importance in the included studies. Coming to an understanding of emotional, psychological, spiritual, or practical issues alters the experience of anomalies as part of one’s whole life experience. Seeing traumatic events and anomalous experiences as learning experiences was helpful and led to a sense of meaningfulness. Such processes could foster an approach of acceptance. The dimension of acceptance was cited as a helpful factor in several studies in this synthesis. This can be understood as a factor in gaining an understanding of mental health difficulties and clarity through the development of a personal explanatory framework that enhanced acceptance. Key explanatory frameworks concern spiritual/religious versus medical/clinical perspectives, which may lack integration and lead to conflicting understanding and further difficulties in acceptance of clients (Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, & Slade, Citation2019). Such perspectives show the complexity of approaching spirituality and mental health problems and call for clinicians to be aware and careful in dealing with this issue.

Resonance refers to “a true experience” involving a moment of losing control (Rosa, Citation2016). In this sense, resonance implies becoming vulnerable, which coincides with the above perspectives. Emancipation is an important element in the concept of resonance and refers to people’s needs to be able to discern and develop their own voices in a personal meaning making process. This underlines the need for professionals to help clients find meaning in spiritual experiences. Such meaning making processes are linked to coping (Schnell, Citation2020), and clarify belonging as a highly subjective concept that should be viewed as an active achievement in meaning making. Such processes cannot arise from reflection alone but are qualities of subjective engagement in meaningful relationships.

Seikkula and Arnkil (Citation2013) underline how meaningful relationships are based on mutual respect for the equal worth of all human beings and the uniqueness of each individual. Seikkula and Arnkil (Citation2013) presuppose an authentic attitude from the perspectives of the professional and the client. Such engagement involves interpersonal contact, which can enhance resonance as a meaningful experience. Longing for a new meaning is also linked to autonomy, which involves having possibilities, control, and dignity. In this way, autonomy is linked to resonance and underlines the importance of mental health professionals facilitating relationships of quality that allow people to find their own voice and a new meaning in life. The individual`s sense of regaining autonomy is encompassed by being resourceful and was found through support and encouragement from contact with others such as professionals in several of the studies. This demonstrates the importance of having someone alongside who can provide hope and motivation. It outlines a personal path of growth and healing charted by individuals for themselves. Doing something for others integrated the experiences related to the mental health issues into a changed framework of understanding that allowed difficult experiences to become part of everyday life. Resonance refers to encountering the world in such a way that we feel truly touched by someone we meet (Rosa, Citation2016). This underlines a feeling of self-efficacy and positive individual consequences, which give relevance to this encounter (Schnell, Citation2020). Significance refers to the perception of resonance to our actions and gives personal meaning to individual actions (Schnell, Citation2020), which indicates a way of transforming ourselves in the sense of co-production (Rosa, Citation2016). Of particular importance in the studies were like-minded others, with whom one could experience resonance and acceptance of one’s feeling of struggling as a coping capacity. The perspectives mentioned here provide possibilities to lead the individual to meaningfulness, and a coherent view of self and the life world.

Limitations and strengths

Systematic reviews of qualitative studies are an emerging methodology aiming to gain a broader understanding of particular phenomena. The literature review of Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) was the first systematic review investigating spirituality from the first-person perspective of people who have experienced mental health issues, which guided the present qualitative synthesis.

There are diverse understandings of the concept of spirituality in the field of mental health, and the many definitions complicated the search. The search strings represent a broad approach in the understanding of different concepts related to spirituality.

In general, qualitative systematic reviews are criticized for de-contextualizing findings. To address this issue, the well-known method of thematic synthesis of qualitative studies of Thomas and Harden (Citation2008) was followed. The ENTREQ statement (Tong, Flemming, McInnes, Oliver, & Craig, Citation2012) was followed to ensure the structure of this synthesis. While it only included studies from 2019, the literature review of Milner, Crawford, Edgley, Hare-Duke, and Slade (Citation2019) laid the foundation for the search strings and studies published in later years (2019–2022).

The analysis was based on primary studies involving different types of qualitative approaches in different mental health care contexts. This heterogeneity was anticipated, but it can be challenging when data are interpreted from different countries, settings, and contexts. However, we see heterogeneity as a possible source of insight. Despite their differences, the primary studies were similar in reporting subjective experiences related to spirituality, from in- and out-patient perspectives. The spiritual experiences were thus viewed from an “acute” perspective and an out-patient perspective. This shows a broad understanding of the concept of spirituality.

One of the limitations is that studies written in languages other than English or Scandinavian were excluded. Moreover, the relatively low number of included studies might be seen as a limitation. However, given the richness of the information obtained from each study, a larger sample could have prevented a broader and deeper analysis which could have threatened the interpretative validity of the results.

Conclusion

This qualitative synthesis offers important insight into spirituality as experienced from the subjective life world of people with mental health issues. “The new paradigm” underlines the concept of spirituality as an essential and resourceful part of holistic care in the field of mental health. This study has important implications for future practice and research.

Based on the study findings, the article highlights the need for professionals to engage in the spiritual domain in holistic terms, which implies an active focus on this complex phenomenon. This perspective underlines the need for professionals to have an open and accepting attitude toward the different ways mental health clients connect with spirituality. It is of crucial importance that professionals facilitate relationships that address subjective spiritual needs and engage in these needs to provide holistic care and recovery.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all the authors of articles used in this study. This study was funded by VID Specialized University, Oslo, Norway.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Allott, K., Steele, P., Boyer, F., de Winter, A., Bryce, S., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., & Phillips, L. (2020). Cognitive strengths-based assessment and intervention in first-episode psychosis: A complementary approach to addressing functional recovery? Clinical Psychology Review, 79, 101871. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2020.101871

- Anthony, W. A. (1993). Recovery from mental illness: The guiding vision of the mental health service system in the 1990s. Psychosocial Rehabilitation Journal, 16(4), 11. doi:10.1037/h0095655

- Antonovsky, A. (1979). Health, stress, and coping. New Perspectives on Mental and Physical Well-Being, 12–37.

- Antonovsky, A. (1987). Unraveling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. San Francisco, 175.

- Benner, D. G. P. (2011). Soulful spirituality: Becoming fully alive and deeply human. Brazos Press. ISBN: 1441214364.

- Bonelli, R. M., & Koenig, H. G. (2013). Mental disorders, religion and spirituality 1990 to 2010: A systematic evidence-based review. Journal of Religion & Health, 52(2), 657–673. doi:10.1007/s10943-013-9691-4

- Buber, M. (1992). On intersubjectivity and cultural creativity. University of Chicago Press. ISBN: 0226078078.

- Chan, S. L., Lau, P. L., & Wong, Y. J. (2020). ‘I am Still Able to Contribute to Someone Less Fortunate’: A Phenomenological Analysis of Young Adults’ Process of Personal Healing from Major Depression [Article]. International Journal for the Advancement of Counselling, 42(1), 97–111. doi:10.1007/s10447-019-09387-5

- Clarke, I. (2010). Psychosis and spirituality: Consolidating the new paradigm. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN: 0470970294.

- Cook, C. C. (2004). Addiction and spirituality. Addiction, 99(5), 539–551. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00715.x

- Cook, C. C. (2020). Religion and psychiatry: Research, prayer and clinical practice. BJPsych Advances, 26(5), 282–284. doi:10.1192/bja.2020.43

- Cook, C., & Grimwade, L. (2021). Spirituality and Mental Health. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists.

- Cook, C. C., Powell, A. S., & Sims, A. (2016). Spirituality and narrative in psychiatric practice: Stories of mind and Soul. RCPsych Publications London. ISBN: 1909726451.

- Damsgaard, J. B., Overgaard, C. L., & Birkelund, R. (2021). Personal recovery and depression, taking existential and social aspects into account: A struggle with institutional structures, loneliness and identity. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 67(1), 7–14. doi:10.1177/0020764020938812

- Elkins, D. N., Hedstrom, L. J., Hughes, L. L., Leaf, J. A., & Saunders, C. (1988). Toward a humanistic-phenomenological spirituality: Definition, description, and measurement. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 28(4), 5–18. doi:10.1177/0022167888284002

- Eriksson, K. (2010). Evidence: To see or not to see. Nursing Science Quarterly, 23(4), 275–279. doi:10.1177/0894318410380271

- Fallot, R. D. (2007). Spirituality and religion in recovery: Some current issues. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 30(4), 261. doi:10.2975/30.4.2007.261.270

- Frankl, V. (1984). Mans search for meaning Freeman, M. New York: Washington Square. Narrative foreclosure in later life: Possibilities and ….

- Greenson, R. (1960). Empathy and its vicissitudes. The International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 41(8), 418–424. doi:10.1177/104438946004100805

- Grimwade, L., & Cook, C. (2019). The clinician’s view of spirituality in mental health care. Chaplaincy and Spiritual Care in Mental Health Setting, 31–43.

- Heidegger, M. (1977). Basic writings: From Being and time (1927) to the task of thinking (1964). M. Niemeyer Tübingen.

- Heidegger, M. (1993). The Cambridge companion to Heidegger. Cambridge University Press. ISBN: 0521385970.

- Helminiak, D. A. (2001). Treating spiritual issues in secular psychotherapy. Counseling and Values, 45(3), 163–189. doi:10.1002/j.2161-007X.2001.tb00196.x

- Ibrahim, N., Ng, F., Selim, A., Ghallab, E., Ali, A., & Slade, M. (2022). Posttraumatic growth and recovery among a sample of Egyptian mental health service users: A phenomenological study. BMC Psychiatry, 22(1), 255. doi:10.1186/s12888-022-03919-x

- Jones, S., Sutton, K., & Isaacs, A. (2019). Concepts, Practices and Advantages of Spirituality Among People with a Chronic Mental Illness in Melbourne. Journal of Religion & Health, 58(1), 343–355. doi:10.1007/s10943-018-0673-4

- Jordan, G., Malla, A., & Iyer, S. N. (2019). “It’s Brought Me a Lot Closer to Who I Am”: A Mixed Methods Study of Posttraumatic Growth and Positive Change Following a First Episode of Psychosis. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10, 480. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00480

- Jordan, G., Malla, A., & Iyer, S. N. (2020). Perceived facilitators and predictors of positive change and posttraumatic growth following a first episode of psychosis: A mixed methods study using a convergent design. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 289. doi:10.1186/s12888-020-02693-y

- Koenig, H. G. (2009). Research on religion, spirituality, and mental health: A review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 54(5), 283–291. doi:10.1177/070674370905400502

- Koenig, H. G. (2013). Is religion good for your health?: The effects of religion on physical and mental health. Routledge. ISBN: 1315869969.

- Koenig, H., Koenig, H. G., King, D., & Carson, V. B. (2012). Handbook of religion and health. Oup Usa. ISBN: 0195335953.

- Koslander, T., Rönning, S., Magnusson, S., & Wiklund Gustin, L. (2021). A ‘near-life experience’: Lived experiences of spirituality from the perspective of people who have been subject to inpatient psychiatric care [Article]. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(2), 512–520. doi:10.1111/scs.12863

- Leamy, M., Bird, V., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Slade, M. (2011). Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: Systematic review and narrative synthesis. British Journal of Psychiatry, 199(6), 445–452. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.110.083733

- Lee, M. Y., Eads, R., Yates, N., & Liu, C. (2021). Lived Experiences of a Sustained Mental Health Recovery Process Without Ongoing Medication Use [Article]. Community Mental Health Journal, 57(3), 540–551. doi:10.1007/s10597-020-00680-x

- Martinsen, K. (2015). Sykeværelset–Sett fra sengen. Klinisk sygepleje, 29(4), 4–19. doi:10.18261/ISSN1903-2285-2015-04-02

- Miller, W. R., & Thoresen, C. E. (2003). Spirituality, religion, and health: An emerging research field. The American Psychologist, 58(1), 24. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.58.1.24

- Milner, K., Crawford, P., Edgley, A., Hare-Duke, L., & Slade, M. (2019). The experiences of spirituality among adults with mental health difficulties: A qualitative systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, e34. doi:10.1017/S2045796019000234

- Moberg, D. O. (2002). Assessing and measuring spirituality: Confronting dilemmas of universal and particular evaluative criteria. Journal of Adult Development, 9(1), 47–60. doi:10.1023/A:1013877201375

- Murgia, C., Notarnicola, I., Rocco, G., & Stievano, A. (2020). Spirituality in nursing: A concept analysis. Nursing Ethics, 27(5), 1327–1343. doi:10.1177/0969733020909534

- Newman, M., & Gough, D. (2020). Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application. Systematic Reviews in Educational Research: Methodology, Perspectives and Application, 3–22. ISSN: 3658276010.

- Pargament, K. I. (2013). Searching for the sacred: Toward a nonreductionistic theory of spirituality. ISSN:1433810794. doi:10.1037/14045-014.

- Peplau, H. E. (1992). Interpersonal relations: A theoretical framework for application in nursing practice. Nursing Science Quarterly, 5(1), 13–18. doi:10.1177/089431849200500106

- Rosa, H. (2016). Resonanz: Eine soziologie der weltbeziehung. Suhrkamp verlag. ISBN: 351874285X.

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2002). Finding the findings in qualitative studies. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 34(3), 213–219. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2002.00213.x

- Schibbye, A. -L. -L. (2009). Relasjoner: et dialektisk perspektiv på eksistensiell og psykodynamisk psykoterapi. Universitetsforlaget. ISBN: 8215015255.

- Schnell, T. (2020). The psychology of meaning in life. Routledge. ISBN: 0367823160.

- Seikkula, J., & Arnkil, T. E. (2013). Open dialogues and anticipations-Respecting otherness in the present moment. Thl. ISBN: 9523020226.

- Slade, M., Leamy, M., Bacon, F., Janosik, M., Le Boutillier, C., Williams, J., & Bird, V. (2012). International differences in understanding recovery: Systematic review. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 21(4), 353–364. doi:10.1017/S2045796012000133

- Sperry, L. E., & Shafranske, E. P. (2005). Spiritually oriented psychotherapy. American Psychological Association. ISBN: 1591471885.

- Swinton, J. (2001). Spirituality and mental health care: Rediscovering a’forgotten’dimension. ISBN: 1846422205.

- Swinton, J. (2020a). Finding Jesus in the storm: The spiritual lives of Christians with mental health challenges. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. ISBN: 1467460249.

- Swinton, J. (2020b). BASS ten years on: A personal reflection. Journal for the Study of Spirituality, 10(1), 6–14. doi:10.1080/20440243.2020.1728869

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Tong, A., Flemming, K., McInnes, E., Oliver, S., & Craig, J. (2012). Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 12(1), 1–8. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

- van Nieuw Amerongen-Meeuse, J. C., Schaap-Jonker, H., Hennipman-Herweijer, C., Anbeek, C., & Braam, A. W. (2019). Patients’ Needs of Religion/Spirituality Integration in Two Mental Health Clinics in the Netherlands. Needs of Religion/Spirituality Integration in Two Mental Health Clinics in the Netherlands: Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(1), 41–49. doi:10.1080/01612840.2018.1475522

- Verghese, A. (2008). Spirituality and mental health. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 50(4), 233. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.44742

- Weathers, E., McCarthy, G., & Coffey, A. (2016). Concept analysis of spirituality: An evolutionary approach. Nursing Forum, 51(2), 79–96. doi:10.1111/nuf.12128

- Yalom, I. (1980). Existential psychotherapy basic books. New York: Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data.