Abstract

This study recognizes that a pervasive, binary view of gender does not capture everyone in the United Kingdom (UK) (for example, lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and others (LGBTQ+); non-binary; gender-diverse communities). The study sought to develop new understandings regarding what might be relevant in considering how gender is viewed by young people in the UK. A three-round online Delphi methodology was employed with a panel of young people, aged 16–25 years, who recognized that current models of gender do not represent everyone. The panel rated a series of statements related to the way in which gender is viewed and contributed their own statements. A consensus level of 70% agreement was set to include statements in a final framework. The panel reached consensus on a collection of statements which were used to inform new guiding frames of gender to capture diverse possibilities. The framework presents a perspective which allows multiple constructions of gender to co-exist, considers that constructions may change through time, and shares how language can act as a supportive tool. The framework is discussed in relation to the existing evidence base and can be used to communicate the panel’s core messages about gender possibilities in the UK.

Introduction

West and Zimmerman’s (Citation1987) influential paper examines how people are held accountable to ‘do gender’ in everyday interactions. ‘Doing gender’ requires individuals to dress, behave, and interact in social worlds through ways that express their assigned sex (Lorber, Citation1994; West & Zimmerman, Citation1987). When people ‘do gender’, they construct an array of social differences between male and female categories; differences that West and Zimmerman (Citation1987) suggest are artificial. These assumptions form the foundations of hetero- and cis-normativity: the privileging of social and cultural inequalities which derive from the maintenance of an essentialist, binary model of gender (Bauer et al., Citation2009; Butler, Citation2007). Theorists suggest that hetero- and cis-normativity are entrenched in social worlds: taught and reinforced as early as birth and are socially maintained within family environments and schools (Donelson & Rogers, Citation2004; McGuire et al., Citation2016).

This paper aims to offer considerations toward a new theory of gender based on these societal assumptions. Firstly, the paper reviews literature on Western normative school environments and contemporary models of gender, before it reports on methods used in a Delphi study with a panel of UK-based young people. It then examines the findings, presenting key lessons that the panel wish for others to know about gender.

Normative Western school environments

In comparison to their peers, young people whose lived experience challenges Western societies’ hetero- and cis-normative assumptions (such as LGBTQ + communities) experience discrimination, lower academic achievement, and negative impacts on their psychological wellbeing (Bradlow et al., Citation2017; Kosciw et al., Citation2020). Specifically, those who identify as transgender, or gender-diverse, can feel particularly unsafe within these environments, reporting higher levels of discrimination and victimization than their cisgender peers (Day et al., Citation2018; Toomey et al., Citation2012).

Research is beginning to show how Western school environments may reinforce the gender binary through institutionalized hetero- and cis- normativity. Gender-segregated practices, such as administrative procedures, bathrooms, and sports (Bragg et al., Citation2018; McBride, Citation2021; Smith et al., Citation2014), impact on gender-diverse youth; for example, young people in Bragg et al.’s (Citation2018) research reported on hearing gendered assumptions such as ‘girls couldn’t throw’ (p. 430). Yet not everyone accepts these Western cis-normative standards, and research suggests that young people and their parents/carers are advocating for change, especially where school policies to support these populations are non-existent, or where they are available, appear individualistic or tokenistic (Bower-Brown et al., Citation2023; Davy & Cordoba, Citation2020). Bragg et al. (Citation2018) reports the views of young people who noticed teachers challenging gendered assumptions but, sometimes, how these may be received by further discrimination:

And then there’s some boys that go ‘oh here she goes again about girls being equal to boys’ and it’s like, well we should be equal to boys because it isn’t fair that boys see themselves as being higher than girls (p. 430).

Although it is critical to implement policies to facilitate the inclusion and belonging of gender-diverse populations (McGowan et al., Citation2022), it remains evident that for some young people, whose lived experience challenges hetero- and cis-normative structures, they remain unavoidably counter-normative within school environments (Austin, Citation2016; Bragg et al., Citation2018).

A perpetual, binary model of gender

Difficulties for young people navigating Western normative school environments can be linked to the prominence of hetero- and cis-normativity, pulling individuals to enact essentialist gender choices (Bragg et al., Citation2018). In a review, Hyde et al. (Citation2019) note that the binary model of gender fundamentally misrepresents psychological and biological systems of those who identify as gender diverse. These findings are well rooted within the thinking of contemporary feminist theorists, who argue that when individuals are governed by normative narratives, their lives are compared against a ‘top-down’ binary model of gender that fails to represent everyone in society (Butler, Citation2007; Renold, Citation2000). Although international alternatives to these gender models do exist (UNESCO, Citation2019), this paper will explore gender through a Western lens to understand its relevance to UK-based young people.

Contemporary models of gender

Following critiques of cis-normativity, new models of gender have begun to challenge binary structures and aim to represent more diverse identities and experiences. Lev (Citation2004) approached gender through a constructivist frame to develop the four components of sexual identity model (2004, see Jourian, Citation2015 for a summary). The model represents four distinct components: biological sex, gender identity, gender-role expression, and sexual orientation. Lev (Citation2004) suggests these four components exist on independent continuums and can change throughout the individual’s lifespan.

Lev’s (Citation2004) model allows representation for those whose experiences may not fit traditional binary models of gender. Strengths of the model are in its conception from the narratives of gender diverse people and how it directly challenges cisnormativity as an environmental problem, rather than individuals (Jourian, Citation2015). The model also celebrates self-determination: individuals are permitted agency to construct their own identities. Its utility has been adapted within contemporary interpretations that are accessible to young people, such as the Genderbread Person (Killermann, Citation2017) and the Gender Unicorn (Trans Student Educational Resources, Citation2015). These adaptions are iterative and continue to develop Lev’s (Citation2004) original model. For example, in the fourth iteration of Killermann’s (Citation2017) Genderbread Person, ‘biological sex’ is represented as ‘sex assigned at birth’ and ‘anatomical sex’. These revisions allow space for new constructions to capture a developing gender language accurately.

However, these models are not without their limitations. Jourian (Citation2015) highlights how Lev’s (Citation2004) model still privileges the binary within its fixed constructs, which exist on a continuum between two stable opposites (e.g. ‘man’ and ‘masculine’ on one end; ‘woman’ and ‘feminine’ on the other). These critiques may also be applied to more contemporary adaptions: the latest versions of the Genderbread Person (Killermann, Citation2017) and Gender Unicorn (Trans Student Educational Resources, Citation2015) reflect current constructs in wide use (e.g. ‘woman-ness’ is used to move away from the fixedness of the ‘woman’) but are still rooted within binary, fixed qualities. Therefore, there is a need to reconstruct our models of gender to move beyond innate binary assumptions, especially given the increasing numbers in Western societies who are beginning to challenge cis-normativity by identifying their gender as outside of the binary (Dargie et al., Citation2014; Thorne et al., Citation2019; Vijlbrief et al., Citation2020).

Jourian (Citation2015) created a dynamic model, which expands language and allows a breadth of gender possibilities to be represented beyond the binary (see Jourian, Citation2015, for examples). However, the researcher reflects on the complexity of their model for a lay audience and the need for testing with populations it seeks to represent. The language also does not appear to derive from communities themselves.

Rationale for current study

The extent to which these emerging models of gender provide a valid alternative to traditional binary models and are supportive of young people in affirming their identities, is unclear. Although Lev (Citation2004) consulted with gender-diverse communities, this must be recognized in the early millennial context and, since then, constructions related to gender have emerged and evolved (e.g. more young people now identify outside of the gender binary). Therefore, there is scope to build a framework of gender from the ‘ground-up’, with young people themselves, to represent the diverse possibilities, and to complement existing research that asks young people about gender construction (Jackson et al., Citation2022; Smith et al., Citation2014).

Young people have also begun constructing new possibilities for themselves and since Lev’s (Citation2004) original conceptions, the internet has emerged as a platform for young people to seek and understand their own experiences, establish belonging with others, and allow experimentation toward new constructions of gender possibilities (Bradlow et al., Citation2017; Bragg et al., Citation2018; Darwin, Citation2017; Vijlbrief et al., Citation2020). Despite this observed level of creativity in online spaces, its potential is yet to be fully captured within empirical research. Sargeant et al. (Citation2022) further suggests that young people have become their own ‘agents of change’: they have developed new ways to recognize themselves in the absence of research and policy. This is linked to Brown’s (Citation1989) normative creativity: the notion that those perceived as ‘deviations from the norms’ engage in a level of creative necessity to construct their truths where no clear guidelines exist. Therefore, it is possible to consider gender as an ever-evolving construct that could be explored with young people who are already at the helm of its development.

Method

Design and procedure

The current study employed a modified online three-round Delphi approach (Keeney et al., Citation2011). Delphi is an iterative methodology, which consists of questionnaires (known as ‘rounds’), to build consensus on a topic of interest with panel members (Jago et al., Citation2020; Powell, Citation2003). After each round, feedback regarding the overall results is shared with panel members, as well as subsequent opportunities to amend their responses whilst considering other panelists’ views. Typically, questionnaires are sent out until consensus is achieved (Niederberger & Spranger, Citation2020). Delphi’s use is well documented, having recently benefited the creation of evidence-informed guidelines and competency frameworks across educational psychology; for example, gathering young people’s perspectives on mental health provision (Jago et al., Citation2020), defining key features Educational Psychologist (EP) practice such as cultural responsivity (Sakata, Citation2021) and the quality of dynamic assessment tools (Green & Birch, Citation2019). The current study sought to employ Delphi to co-construct possibilities of gender with young people.

Delphi panelists are expected to have more expertise on topics under investigation than the general population and have experience concerning the target issue (Hsu & Sandford, Citation2007). For the current study, panelists (aged 16–25) were required to believe that existing models of gender fail to represent everyone. A number of advantages to this approach were identified: it would encourage young people from around the UK to contribute their perspectives and capture their possible prior experiences of using the internet to co-construct their identities, enable panelists to provide their views anonymously, avoid power balance effects which may occur in face-to-face approaches (Jago, Citation2019; Sakata, Citation2021) and it was felt that anonymity would keep community members safe, allowing them to fully explore gender possibilities without judgment.

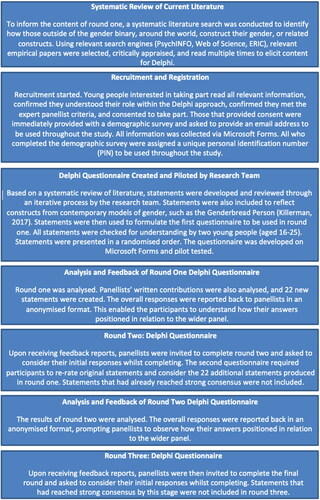

Items in the first round were identified via a systematic review of relevant literature, which answered the question, ‘How do those outside of the gender binary, around the world, construct their gender or related constructs?’ Findings from the systematic review were synthesized to form an initial set of gender statements which addressed the question of how gender was viewed which meant that the panelists started from a ‘common base’ of knowledge (Jago et al., Citation2020; Keeney et al., Citation2011) in relation to the question: ‘Which of these are important to the way in which gender is viewed?’ Beginning with statements based on conceptualizations by those with genders outside of the binary (e.g. non-binary; genderqueer), whose own lived experiences challenge dominant binary assumptions was also considered a useful starting point for panel discussion. All statements were checked for readability by two young people and changes made accordingly. Panelists rated all statements using a four-point Likert scale (‘very important’, ‘important’, ‘slightly important’, and ‘not at all important’ to be included in a new theory of gender). Some definitions were provided for key terms (see Appendix). Panelists were also provided with the opportunity to generate their own statements to be included in subsequent rounds. Upon completion of all three rounds of Delphi, panelists were paid a £10 Amazon voucher. The Delphi stages are summarized in .

Participants

The quality of a Delphi study is contingent on the definition and selection of expert panelists (Kennedy, Citation2000). Close attention was paid to the identification of panelists through purposive selection criteria (Jorm, Citation2015; Powell, Citation2003).

Young people were invited to register their interest in the current study if they confirmed they met the following expert panelist criteria: 1) willing and motivated to contribute their expertise toward identifying components to inform a new theory of gender 2) have experienced their own personal discomfort, or are aware of the discomfort experienced by others, within current models of gender 3) indicated that they understood the purpose and aims of the study and their individual contribution within Delphi. Particular attention was also given in recruitment materials for the participation of underrepresented groups (e.g. ethnic minority communities; religious minority communities; LGBTQIA+ communities; people with disabilities). The researcher made it clear that the study was inclusive: the team were keen to hear from anyone who met the expert panelist criteria and wished to take part, whether LGBTQIA+ identified or not, as laid out in criterion (2) above.

To support interested young people in understanding Delphi, written explanations were provided and an optional video, created by the researcher, was offered. To help ensure young people felt safe in engaging with this study, all aims of the project were clear and the researcher disclosed their own identities and reasons for being interested in this research.

Schools, colleges, and further education settings across the UK were contacted with information about the study and asked to share an information flyer with young people who may be interested in taking part. UK-based youth and charity organizations were also approached to support recruitment. The information flyer was also made available for online distribution and circulated via advertisements on social media platforms (e.g. Twitter and Facebook). Educational professionals in the UK were welcomed to share knowledge of the study, which lead to a ‘snowballing effect’.

In total, 47 young people registered their interest to take part by completing informed consent forms and providing demographic information. Due to the high levels of commitment required to participate in Delphi (Keeney et al., Citation2011), some attrition was expected between initial recruitment and individual rounds. The first round was completed by 35 young people. In the current study, 31 panelists completed round two and 26 panelists completed round three between November 2021 and February 2022 (see for demographic information). Participants were asked to describe their identities in their own words, recognizing the diversity of the population (Jones et al., Citation2019) and the importance of self-determination (Vincent, Citation2018) (see for further demographic data). All data was collected via Microsoft Forms. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University of Southampton’s Ethics and Research Governance (approval number 66939).

Table 1. Participants’ demographic information.

Table 2. Participants’ self-constructed identities.

Analysis

A feedback report was produced for each panelist for every completed round. These reports reminded panelists of their individual ratings for each item and allowed comparison to the wider panel. Additional items, generated by the panelists themselves, were included if they described a concept or idea that had not been previously represented.

Data frequencies and descriptive statistics were conducted to identify consensus levels on each item. There is no definitive way of defining consensus for Delphi studies: Keeney et al. (Citation2011) report this can range between 51% and 100%. For this study, consensus was set at 70%, based on a review of the literature conducted by Green and Birch (Citation2019).

Delphi researchers have also collapsed categories based on the levels of importance (Green & Birch, Citation2019; Phillips et al., Citation2014; Sawford et al., Citation2014). Therefore, consensus was approached in the following way:

Strong consensus: If 70% or more panelists rated an item as ‘very important’ this was viewed as strong consensus. Equally, strong consensus was considered for statements that were not important to the ways in which gender should be viewed if 70% or more panelists rated a statement as ‘not at all important’.

Consensus: If 70% of panelists rated a statement as ‘very important’ or ‘important’, then it was considered that consensus had been reached.

Results

provides a summary of the overall results of this Delphi study. Overall, a total of 105 statements were generated, 83 from the systematic literature search and 22 from the panelists’ own conceptualizations.

Table 3. Summary of the total number of statements included in this Delphi study.

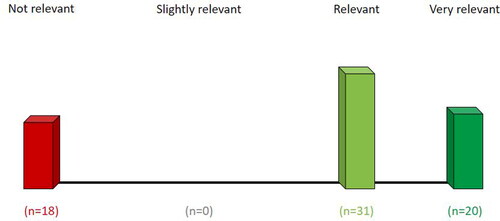

All statements were rated by the Delphi panel. Consensus was achieved for 69 statements. In our quest to create a wider framework, statements that achieved consensus via panelists’ individual ratings of importance are presented in terms of concluding relevance. Therefore, all 69 statements should be collectively considered to the ways in which the panel wish gender to be viewed. A visual representation is represented within .

Of the 69 statements, 20 reached via strong consensus were deemed very relevant () and 18 reached via strong consensus were deemed not relevant () to the ways in which gender is viewed. 31 statements reached via consensus were deemed relevant () to the ways in which gender is viewed. The statements are recorded in their entirety to allow the panel’s views to be fully represented. In , , , and 7 the ‘*’ symbol represents a statement that was contributed by the panelists themselves. Statements that did not reach consensus can be found in .

Table 4. Very relevant to the way in which gender should be viewed.

Table 5. Not relevant to the way in which gender could be viewed.

Table 6. Relevant to the way in which gender should be viewed.

Table 7. Delphi statements that did not reach consensus.

Discussion

This study asked young people in the UK what they felt is important about gender possibilities. Delphi methodology, a consensus building tool, allowed young people to construct new guiding frames of gender which may represent those whose lived experiences challenge hetero- and cis-normative assumptions.

The panelists’ response to a 105-statement Delphi study identified 51 items that were collectively deemed relevant or very relevant to the ways in which gender is viewed. A further 18 items were also collectively identified as not relevant. Whilst this study is relatively small scale, exploratory, and cannot be viewed as the ‘correct answer’ (p. 1013, Hasson et al., Citation2000), the framework generated by the panel represents what may be relevant for wider populations to consider in terms of how gender is conceived. The following section will discuss key lessons the expert panel felt relevant to know about gender, how constructions align with current knowledge, and identify ways forward to develop this field further.

Gender can transcend essentialism and determinism

In this study, some statements that achieved strong consensus related to what panelists’ thought was not relevant to the ways in which gender should be viewed. All 18 statements achieved a strong consensus during round one (e.g. ‘Gender is exclusively male and female’; ‘A person’s experience of their gender is fixed and cannot change’). These results suggest the panel agree that essentialist and biologically determined understandings fail to capture the breadth of gender possibilities (e.g. ‘A person should express their gender in line with the gender they have been assigned at birth’).

At present, there are difficult conversations in the UK taking place regarding how we understand gender (Sargeant et al., Citation2022). In the UK media, perspectives are increasingly positioned via two opposites, juxtaposing essentialism and biological determinism against the diverse gender possibilities with which some identify (Faye, Citation2021). These juxtapositions seem to have been captured within Delphi: the panelists do not see essentialist, determined models of gender as representing the diverse possibilities of what gender could be. Instead, the panel arrived at a strong consensus that it is very relevant to know that, for some, it is possible to transcend essentialism (e.g. ‘A person may identify as having a specific, further gender outside of the binary’) and biological determinism (‘A person’s gender identity can differ from their birth-assigned gender or sex’).

Gender can exist outside or within binary constructs

To support their desire to transcend biological determinism, the panel further communicated that it is very relevant to understand that ‘sex and gender are two separate constructs’. The panel made several suggestions which relate to moving away from essentialist models of gender. Statements that reached strong consensus related to deconstructing the gender binary (e.g. ‘A person can identify as neither male or female’). The panel made their opinion clear that it is very relevant to understand that ‘ideas and systems of classification related to male and female are outdated’. The panel’s perspective supports research that is starting to notice individuals identifying against, or even deconstructing, pervasive Western systems that promote two binary genders (Dargie et al., Citation2014; Thorne et al., Citation2019; Vijlbrief et al., Citation2020).

However, the panel also strongly agreed that binary models may represent some, whilst also signaling that wider gender constructions can also co-exist (e.g. ‘Gender identity can be fluid for some and static for others’; ‘Some transgender people identify with binary genders’). Through a positivist lens, this could be interpreted as contradiction where the panel have also supported statements which seem to indicate a deconstruction of the gender binary. However, this should be considered within the constructivist approach of the methodology: Delphi has allowed the panel freedom to co-create gender possibilities which represent diverse populations, moving away from approaches that seek to uncover universal truths (Semp, Citation2011). In the current study, the panel have indicated a possibility that multiple gender truths can exist: it is possible for some to identify with a binary gender, whereas for others, they should be allowed self-determination to construct a gender identity that may sit beyond the confines of dimorphism.

Gender identities can fluctuate through time and social worlds

Related to their ideals of fluidity, the panel arrived at a strong consensus that an individual’s gender may change through their histories and experiences (e.g. ‘Gender identity is fluid and can fluctuate over time’). This is well supported by recent literature, which has started to dissect the gender binary’s fixed qualities and alternatively suggest that, for some, identity discovery requires high levels of reflection (Bradford et al., Citation2019) and may even occur after identifying as gender-diverse (Whittle et al., Citation2007). The panel’s perspective holds important implications for governing models and structures as society may need to permit space for individuals to engage in a level of creative freedom to discover identities. These identities may fluctuate within a contained range of time (Horowit-Hendler, Citation2020), but may alternatively fluctuate across the lifespan (Bradford et al., Citation2019; Stachowiak, Citation2017).

Panelists also indicated their view of gender being recognized as a product of social worlds and experiences. The panel communicated it relevant to understand how ‘gender identity can fluctuate over contexts and social environments’, consider that ‘the way we experience gender can be influenced by other factors (e.g. ethnicity, disability, and age)’, and ‘can change as a result of external pressures (e.g. parents and teachers)’. The panel’s opinion perhaps represents a poignant finding: some may actively alter their truths to some people or situations so that they may fit or feel safe within systems that favor binary gender choices (Tan & Weisbart, Citation2022). The findings of the current study stand in solidarity with implications made within this emerging evidence base: hetero- and cis-normative structures should be questioned to ensure individuals whose experiences challenge these assumptions can present comfortably as their true selves.

At present, models such as the Genderbread Person (Killermann, Citation2017) and Gender Unicorn (Trans Student Educational Resources, Citation2015) do not incorporate identity fluctuation over time or social contexts. The panel also noted it is very relevant to understand that ‘society’s understanding of gender can change over time’, which perhaps alludes to the developing constructions of gender diversity since the new millennium, or possibly reflects their recent identity explorations. These are interesting implications, possibly suggesting new dimensions for contemporary models of gender.

Gender can exist on a continuum

Many statements that the panel considered relevant related to continua frameworks for gender (e.g. ‘A person can be more or less masculine, or more or less feminine’). The panelists’ opinion seems to provide strength to models such as Genderbread Person (Killermann, Citation2017) and Gender Unicorn (Trans Student Educational Resources, Citation2015) in the way they represent continua aspects of gender. The combination, or lack of masculinity/femininity is also accurately reflected in these models (e.g. ‘The way a person expresses themselves can combine/possess neither masculine and feminine elements’).

Language can act as a tool to interpret and construct gender

The final idea expressed relates to interpretations and constructions of language and labels. The panel suggested that it is very relevant that ‘non-binary is an umbrella term to capture a range of identities and experiences’, a theme which is also emerging within contemporary literature (Thorne et al., Citation2019). The panel also indicated it is relevant to allow individuals autonomy to communicate gender (e.g. ‘What a term means to one individual may mean something different to another’). The panel’s perspective is well supported by other exploratory approaches, where gender-diverse young people have communicated it is important to recognize discrepancies between gender terms and how these may hold different meanings and interpretations across individuals (Bradford et al., Citation2019; Vijlbrief et al., Citation2020).

Although this idea echoes the difficulties wider society is experiencing in its search for a universal definition of gender, perhaps what panelists are suggesting is that society should relish a level of discomfort caused by multiple interpretations offered in gender terminology. Greater societal acceptance of diversity could allow individuals the autonomy to self-define their own gender possibilities. This aligns very closely to Wagaman’s (Citation2016) application of counternarratives: the production of alternative narratives by marginalized populations to grant a level of autonomy. Although originally conceived as a critical race theory, Wagaman (Citation2016) delivers a compelling argument to suggest that young people should be supported to discover their own discourses, allowing them to construct their own identities. The employment of counternarratives has been recently observed in some gender-diverse populations, such as non-binary identified young people (Vijlbrief et al., Citation2020).

To further build on the notion of counternarratives, it seems that the panelists engaged with this to a degree themselves, when invited to suggest their own statements. A high proportion of those considered relevant relate to pronoun use and, interestingly, how these are understood by others within social interactions (e.g. ‘pronouns are an important and affirming expressive marker’; ‘not every non-binary person uses they/them pronouns’; ‘pronouns are not indicative of gender’). Further, the panel suggested it is very relevant to understand that ‘gender and pronouns are not always connected’. It is possible that the panel have identified a misconception associated with pronoun use: they may be interpreted as representing a person’s gender identity, but this may not always be accurate. This aligns with Matsuno and Budge (Citation2017) review of the literature on non-binary/genderqueer identities: some use a combination of different pronouns, some avoid pronoun use altogether, and some employ pronouns that align closest to their gender identity at that given time. Therefore, it seems relevant to avoid assumptions associated with an individual’s choice of pronouns and inferences toward their gender identity; like consideration on counternarratives, these young people must be allowed space to construct their own linguistic markers of gender.

Strengths and limitations

The originality and utility of this study is a clear strength. This study contributes a first consensus model, and a first with UK participants, to the emerging wider work across the West that attends to young people’s perspectives on gender to present an initial framework of shared understandings. This study also contributes to the existing, longer recognized non-binary models of gender operant in many other countries, particularly in pre-colonial contexts and still today (for example, Two-Spirit). An online methodology was employed, which enabled recruitment across the UK. The low rate of attrition, in comparison to other Delphi studies, may represent the panel’s interest in the activism and importance of this research: to afford marginalized populations an opportunity to validate their experiences and co-create shared understandings to help inform change.

The study also valued self-definition and heterogeneity within populations: allowing individuals to communicate identities in their own words (Jones et al., Citation2019; Vincent, Citation2018). Deliberate attempts to avoid segregating experiences via identities were avoided via a recruitment strategy which required individuals to self-identify with expert criteria. These considerations are understood within intersectionality (Crenshaw, Citation1992), acknowledging the complexities of how an individual’s multiple identities intersect to create unique experiences and responses to the social worlds around them. Delphi created a shift in power dynamics as it was possible to privilege voices that are not always represented (Wagaman, Citation2016).

Nevertheless, some populations were underrepresented. Over 70% of panelists self-identified as ‘White’, and most as LGBTQ+. Further, no information was collected regarding socioeconomic status and how panelists heard about the study. It may have been possible that a majority responded to advertisement via social media channels, with technology access that may not be available to all. The researcher would have welcomed more young people from a variety of cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds to participate, including allies.

Statements were informed by a relevant systematic literature search, and included ideas represented within contemporary frameworks (Killermann, Citation2017; Trans Student Educational Resources, Citation2015).Yet, although this process resembles recent successful applications of Delphi (Jago et al., Citation2020; Sakata, Citation2021), employing an open-ended round one to ensure statements represent the panel could provide further agency and allow more relevance for the respondents (Green & Birch, Citation2019; Keeney et al., Citation2011). The fact that statements were generated from an international systematic search, which may not have specific relevance to a predominantly White, UK based population is relevant.

To support the panelists’ interpretation of statements, definitions of key terminology were offered. Through consultation with two young people (who checked the statements prior to data collection), it was felt that providing definitions may support panelists in their understanding of some constructions, without necessarily having direct personal experiences themselves. However, it may have been possible that panelists experienced challenges in interpreting some statements. Some may have been difficult for individuals to understand, or transfer to their own realities, without relevant conceptual frameworks or personal experiences (Bradford et al., Citation2019; Robinson, Citation2017). Further Delphi research could take final statements back to participants to check relevance.

Conclusion

Through their dedication and engagement, the panel have created an initial framework for us all to understand what they feel is relevant to the ways in which gender is viewed. Their framework can be used to communicate core messages about gender possibilities, whilst still recognizing levels of diversity and uniqueness that exists. The researcher hopes this Delphi study can be used as a positive example of an iterative methodology designed to work with marginalized populations, rather than for them.

The framework created by this study is positioned within a relative period of time, co-created when a conversation about how society understands gender in the UK remains divisive. The panel themselves have indicated that personal and societal understandings of gender have, and are still likely to, evolve. Language and constructions may continue to emerge as a breadth of new gender possibilities are navigated. Advocates cannot be complacent and must continue to challenge and re-define their own understandings, to learn with those whom current frameworks seek to represent. If positions continue to be adopted which promote these marginalized voices, it may be possible not only to advocate for change on behalf of those who are objectively oppressed within systems, but possibly liberate us all.

Acknowledgements

I wish to express my gratitude to any school, college, or organisation for your support in reaching the voices represented within this article. I would also like to express particular gratitude to the charity Mermaids for supporting the recruitment stages of this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in University of Southampton Institutional Repository at http://doi.org/10.5258/SOTON/D24 31, reference number 471487.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jamie Wilson

Dr Jamie Wilson (he/they) completed a Doctorate in Educational Psychology at the University of Southampton in November 2022. Jamie’s thesis employed two research enquiries, designed to attend to multiple representations of gender and additionally promote voices who are marginalized within wider Western societal assumptions. Jamie is particularly interested in social justice, inclusive practice, and personal construct psychology approaches toward work with children, young people, and the adults who support them. Jamie is currently employed as a local government Educational Psychologist within Hampshire and Isle of Wight Educational Psychology.

Cora Sargeant

Dr Sarah Wright (she/her) is the programme director of the initial training doctorate at the University of Southampton. She has an interest in gender and together with Cora Sargant runs the EP gender Research Group where we supervise trainees in the field of gender diversity (also LGBT + research more generally). She is currently employed as a local government Educational Psychologist within Hampshire and Isle of Wight Educational Psychology.

Natalie Jago

Dr Cora Sargeant (she/her) is a chartered Educational Psychologist and Senior Teaching Fellow at the University of Southampton, where she is the research coordinator of the initial training doctorate in Educational Psychology. Alongside Dr Wright, Cora runs the EP gender research group where we supervise doctoral trainees in the field of gender and relationship diversity.

Sarah Wright

Dr Natalie Jago (she/her) is a chartered Educational Psychologist and is currently employed as a local government Educational Psychologist within Hampshire and Isle of Wight Educational Psychology. Natalie has a passion for promoting the voices of children & young people and inclusive practice with particular interests in positive psychology, person-centred approaches and supporting the emotional wellbeing of children and young people in schools.

References

- Austin, A. (2016). “There I am”: A grounded theory study of young adults navigating a transgender or gender nonconforming identity within a context of oppression and invisibility. Sex Roles, 75(5–6), 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0600-7

- Bauer, G. R., Hammond, R., Travers, R., Kaay, M., Hohenadel, K. M., & Boyce, M. (2009). “I don’t think this Is theoretical; this is our lives”: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. The Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care: JANAC, 20(5), 348–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jana.2009.07.004

- Bower-Brown, S., Zadeh, S., & Jadva, V. (2023). Binary-trans, non-binary and gender-questioning adolescents’ experiences in UK schools. Journal of LGBT Youth, 20(1), 74–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2021.1873215

- Bradford, N. J., Rider, G. N., Catalpa, J. M., Morrow, Q. J., Berg, D. R., Spencer, K. G., & McGuire, J. K. (2019). Creating gender: A thematic analysis of genderqueer narratives. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 155–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2018.1474516

- Bradlow, J., Bartram, F., Guasp, A., & Jadva, V. (2017). School report: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bi and trans young people in Britain’s schools in 2017. Stonewall. https://www.stonewall.org.uk/system/files/the_school_report_2017.pdf

- Bragg, S., Renold, E., Ringrose, J., & Jackson, C. (2018). ‘More than boy, girl, male, female’: Exploring young people’s views on gender diversity within and beyond school contexts. Sex Education, 18(4), 420–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681811.2018.1439373

- Brown, L. (1989). New voices/new visions: Toward a lesbian and gay paradigm for psychology. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 13(4), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1989.tb01013.x

- Butler, J. (2007). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

- Crenshaw, K. W. (1992). Race, gender, and sexual harassment. Southern California Law Review, 65, 1467–1476. https://scholarship.law.columbia.edu/faculty_scholarship/2867

- Dargie, E., Blair, K. L., Pukall, C. F., & Coyle, S. M. (2014). Somewhere under the rainbow: Exploring the identities and experiences of trans persons. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(2), 60–74. https://doi.org/10.3138/cjhs.2378

- Darwin, H. (2017). Doing gender beyond the binary: A virtual ethnography. Symbolic Interaction, 40(3), 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.316

- Davy, Z., & Cordoba, S. (2020). School cultures and trans and gender-diverse children: Parents’ perspectives. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 16(4), 349–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/1550428X.2019.1647810

- Day, J. K., Perez-Brumer, A., & Russell, S. T. (2018). Safe schools? Transgender youth’s school experiences and perceptions of school climate. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47(8), 1731–1742. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-018-0866-x

- Donelson, R., & Rogers, T. (2004). Negotiating a research protocol for studying school-based gay and lesbian issues. Theory into Practice, 43(2), 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4302_6

- Faye, S. (2021). The transgender issue: An argument for social justice. Allen Lane.

- Green, R., & Birch, S. (2019). Ensuring quality in EPs’ use of dynamic assessment: A Delphi study. Educational Psychology in Practice, 35(1), 82–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2018.1538938

- Hasson, F., Keeney, S., & McKenna, H. (2000). Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32(4), 1008–1015. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.t01-1-01567.x

- Horowit-Hendler, S. (2020). Navigating the binary: Gender presentation of non-binary individuals [Doctoral thesis, State University of New York]. https://www.proquest.com/dissertations-theses/navigating-binary-gender-presentation-non/docview/2414442217/se-2

- Hsu, C.-C., & Sandford, B. A. (2007). The Delphi technique: Making sense of consensus. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 12, Article 10. https://doi.org/10.7275/pdz9-th90

- Hyde, J. S., Bigler, R. S., Joel, D., Tate, C. C., & van Anders, S. M. (2019). The future of sex and gender in psychology: Five challenges to the gender binary. The American Psychologist, 74(2), 171–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000307

- Jackson, E. F., Sheanoda, V., & Bussey, K. (2022). ‘I can construct it in my own way’: A critical qualitative examination of gender self-categorisation processes. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 46(3), 372–389. https://doi.org/10.1177/03616843221102787

- Jago, N., Wright, S., Hartwell, B. K., & Green, R. (2020). Mental health beyond the school gate: Young people’s perspectives of mental health support online, and in home, school and community contexts. Educational and Child Psychology, 37(3), 69–85. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2020.37.3.69

- Jago, N. (2019). Mental health beyond the school gate: Young people’s perspectives of mental health support online, and in home, school, and community contexts [Doctoral thesis, University of Southampton]. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/438079/1/28902351_Thesis_e_copy.pdf

- Jones, M. H., Hackel, T. S., Hershberger, M., & Goodrich, K. M. (2019). Queer youth in educational psychology research. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(13), 1797–1816. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1510262

- Jorm, A. F. (2015). Using the Delphi expert consensus method in mental health research. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 49(10), 887–897. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415600891

- Jourian, T. J. (2015). Queering constructs: Proposing a dynamic gender and sexuality model. The Educational Forum, 79(4), 459–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131725.2015.1068900

- Keeney, S., Hasson, F., & McKenna, H. (2011). The Delphi technique in nursing and health research. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Kennedy, H. P. (2000). A model of exemplary midwifery practice: Results of a Delphi study. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health, 45(1), 4–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1526-9523(99)00018-5

- Killermann, S. (2017). The Genderbread Person v4 [Image]. Retrieved February 2022, from https://www.genderbread.org/resource/genderbread-person-v4-0

- Kosciw, J. G., Clark, C. M., Truong, N. L., & Zongrone, A. D. (2020). The 2019 national school climate survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. A report from the GLSEN. GLSEN.

- Lev, A. I. (2004). Transgender emergence: Therapeutic guidelines for working with gender-variant people and their families. Routledge.

- Lorber, J. (1994). “Night to his day”: The social construction of gender. In J. Lorber (Ed.), Paradoxes of gender (pp. 13–36). Yale University Press.

- Matsuno, E., & Budge, S. L. (2017). Non-binary/genderqueer identities: A critical review of the literature. Current Sexual Health Reports, 9(3), 116–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11930-017-0111-8

- McBride, R. S. (2021). A literature review of the secondary school experiences of trans youth. Journal of LGBT Youth, 18(2), 103–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2020.1727815

- McGowan, A., Wright, S., & Sargeant, C. (2022). Living your truth: Views and experiences of transgender young people in secondary education. Educational and Child Psychology, 39(1), 27–43. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2022.39.1.27

- McGuire, J. K., Kuvalanka, K. A., Catalpa, J. M., & Toomey, R. B. (2016). Transfamily theory: How the presence of trans* family members informs gender development in families. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12125

- Niederberger, M., & Spranger, J. (2020). Delphi technique in health sciences: A map. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00457

- Phillips, A. C., Lewis, L. K., McEvoy, M. P., Galipeau, J., Glasziou, P., Hammick, M., Moher, D., Tilson, J. K., & Williams, M. T. (2014). A Delphi survey to determine how educational interventions for evidence-based practice should be reported: Stage 2 of the development of a reporting guideline. BMC Medical Education, 14(1), 159. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-14-159

- Powell, C. (2003). The Delphi technique: Myths and realities. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 41(4), 376–382. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02537.x

- Renold, E. (2000). “Coming out”: Gender, (hetero)sexuality and the primary school. Gender and Education, 12(3), 309–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/713668299

- Robinson, M. (2017). Two-Spirit and bisexual people: Different umbrella, same rain. Journal of Bisexuality, 17(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/15299716.2016.1261266

- Sakata, E. (2021). How can educational psychologists develop culturally responsive practice? A Delphi study [Doctoral thesis, University of Essex]. http://repository.essex.ac.uk/30973/1/E-Thesis%20SAKATA%201809033%20TV.pdf

- Sargeant, C., O’Hare, D., Cole, R., & Atkinson, C. (2022). Editorial. Educational and Child Psychology, 39(1), 4–10. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsecp.2022.39.1.4

- Sawford, K., Dhand, N. K., Toribio, J. A. L., & Taylor, M. R. (2014). The use of a modified Delphi approach to engage stakeholders in zoonotic disease research priority setting. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 182. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-182

- Semp, D. (2011). Questioning heteronormativity: Using queer theory to inform research and practice within public mental health services. Psychology and Sexuality, 2(1), 69–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2011.536317

- Smith, E., Jones, T., Ward, R., Dixon, J., Mitchell, A., & Hillier, L. (2014). From blues to rainbows: The mental health and well-being of gender diverse and transgender young people in Australia. The Australian Research Centre in Sex, Health, and Society.

- Stachowiak, D. M. (2017). Queering it up, strutting our threads, and baring our souls: Genderqueer individuals negotiating social and felt sense of gender. Journal of Gender Studies, 26(5), 532–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2016.1150817

- Tan, S., & Weisbart, C. (2022). Asian-Canadian trans youth: Identity development in a hetero-cis-normative white world. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 9(4), 488–499. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000512

- Thorne, N., Yip, A. K.-T., Bouman, W. P., Marshall, E., & Arcelus, J. (2019). The terminology of identities between, outside and beyond the gender binary – A systematic review. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(2–3), 138–154. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2019.1640654

- Toomey, R. B., McGuire, J. K., & Russell, S. T. (2012). Heteronormativity, school climates, and perceived safety for gender nonconforming peers. Journal of Adolescence, 35(1), 187–196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.03.001

- Trans Student Educational Resources. (2015). The gender unicorn [Image]. Retrieved February 2022, from https://transstudent.org/gender/

- UNESCO. (2019). Bringing it out in the open: Monitoring school violence based on sexual orientation, gender identity or gender expression in national and international surveys.

- Vijlbrief, A., Saharso, S., & Ghorashi, H. (2020). Transcending the gender binary: Gender non-binary young adults in Amsterdam. Journal of LGBT Youth, 17(1), 89–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2019.1660295

- Vincent, B. W. (2018). Studying trans: Recommendations for ethical recruitment and collaboration with transgender participants in academic research. Psychology & Sexuality, 9(2), 102–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2018.1434558

- Wagaman, M. A. (2016). Self-definition as resistance: Understanding identities among LGBTQ emerging adults. Journal of LGBT Youth, 13(3), 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/19361653.2016.1185760

- West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1(2), 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002

- Whittle, S., Turner, L., & Al-Alami, M. (2007). Engendered penalties: Transgender and transsexual people’s experiences of inequality and discrimination. https://www.ilga-europe.org/sites/default/files/trans_country_report_-_engenderedpenalties.pdf

Appendix

Definitions provided to panelists during Delphi study.

Gender: Often expressed in terms of masculinity and femininity, gender is largely culturally determined and is assumed from the sex assigned at birth [provided by Stonewall]

Sex: Assigned to a person based on primary sex characteristics (genitalia) and reproductive functions. Sometimes the terms ‘sex’ and ‘gender’ are interchanged to mean ‘male’ or ‘female’ [provided by Stonewall]

Binary: The classification of gender into two distinct, opposite forms of masculine and feminine [provided by Stonewall]

Physical markers: Biological characteristics (e.g. genital differences; chromosomal differences) [created by researchers, based upon systematic literature review]

Expressive markers: Social choices (e.g. use of make-up; hair style; language; tone of voice) [created by researchers, based upon systematic literature review]