ABSTRACT

Numerous socio-demographic and psychographic factors affect food waste behavior of consumers at home and away. Although the effect of religiosity has been recognized, it remains only marginally investigated, especially in the context of food consumption outside the home. Previous quantitative studies have only established positive correlation between religiosity and food waste reduction intentions in households. This paper provides a qualitative perspective on the role of religiosity in food waste behavior at home and away by undertaking in-depth semi-structured interviews with Islam followers (n = 22) and religious leaders (n = 4). Unlike previous studies, the paper demonstrates limited association between religiosity and wasteless behavior. Consumers do not always associate wasted food with a sinful act. Social and cultural norms outweigh the positive effect of religious values and prompt wasteful behavior, especially when eating out. The paper argues that religious leaders should play a more pro-active role in encouraging wasteless behavior at home and away.

许多社会人口和心理因素影响着消费者在家内外的食物浪费行为. 尽管宗教信仰的影响已经得到了承认,但它仍然只有少量的研究,尤其是在家庭以外的食物消费方面. 之前的定量研究只建立了宗教信仰与家庭减少食物浪费意图之间的正相关关系. 本文通过对伊斯兰信徒(n=22)和宗教领袖(n=4)进行深入的半结构式访谈,从定性的角度探讨了宗教信仰在家庭内外食物浪费行为中的作用. 与之前的研究不同,这篇论文证明了宗教信仰与无浪费行为之间的关联有限。消费者并不总是把浪费食物与罪恶行为联系在一起. 社会和文化规范超过了宗教价值观的积极影响和迅速的浪费行为,尤其是在外出就餐时. 论文认为,宗教领袖应该在鼓励国内外无浪费行为方面发挥更积极的作用.

Introduction

The United Nations Environment Program has recognized food waste (FW) as a major societal challenge calling for urgent measures to prevent its occurrence (UNEP, Citation2021). The preventative measures should target consumer behavior that contributes significantly to FW generation at home and away (Filimonau et al., Citation2020a). Scholarly research can inform the design of preventative measures by revealing the antecedents of FW behavior in various contexts of food consumption (Aschemann-Witzel et al., Citation2015).

The antecedents of FW behavior deserve particular attention in the context of food consumption away from the home as large amounts of food are wasted in hospitality and foodservice operations (Filimonau & De Coteau, Citation2019). Consumers do not finish their meals and produce leftovers (Massow & McAdams, Citation2016) which account for 30–34% of total FW generated in hospitality and foodservice provision (Filimonau et al., Citation2020b). This highlights consumer behavior as key for FW prevention in the context of out-of-home food consumption (Stöckli et al., Citation2018b). Preventative measures should discourage wasteful and encourage wasteless behavior of hospitality and foodservice customers (Hamerman et al., Citation2018).

Multiple socio-demographic and psychographic factors contribute to FW behavior away from the home (Filimonau et al., Citation2020a). Vizzoto et al. (Citation2021) have established correlation between gender and plate waste in the context of out-of-home food consumption in Italy. Talwar et al. (Citation2021a) have pinpointed personal pro-environmental norms as predictors of consumer intention to re-use meal leftovers in US restaurants. However, the number of empirical investigations on the antecedents of waste(full/less) consumer behavior in hospitality and foodservice provision remains scarce (Talwar et al., Citation2021b). This hampers an understanding of the role played by various socio-demographic and psychographic variables in FW generation and prevention away from the home (Stöckli et al., Citation2018a). The under-developed research agenda underlines the need for dedicated studies looking at specific factors and evaluating their effect on waste(full/less) behavior of hospitality and foodservice customers (Chen & Jai, Citation2018).

Religion represents an important factor in consumer behavior research (Mathras et al., Citation2016). While being a critical socio-demographic characteristic of consumer populations in terms of their beliefs, religion is also an important psychographic feature (Arli et al., Citation2019). Religion can affect consumer values, opinions, and attitudes, but also influence consumer lifestyles (Arli & Tjiptono, Citation2014). For example, when speaking of food consumption, religion defines what followers of specific religion (do not) eat, such as Halal or Kosher food (Minton et al., Citation2019). Better understanding of religion as a factor in food consumption behavior at home and away can facilitate the development of more effective marketing and management practices (Suki & Suki, Citation2015). For example, the growth in Halal certified restaurants in USA/Europe is a result of increased awareness among hospitality and foodservice administrations of consumer needs and expectations facilitated by their religious beliefs (Wilkins et al., Citation2019).

Religion can serve an important antecedent of waste(full/less) consumer behavior (Yetkin Özbük et al., Citation2022). Most religions define food as a God’s blessing and discourage its wastage (Elhoushy & Jang, Citation2021). Religions encourage consumers to share surplus food as sharing indicates kindness and promotes equality (Minton et al., Citation2020). This notwithstanding, the role of religious beliefs in shaping consumer FW behavior remains under-researched (Porpino, Citation2016). Although a handful of studies have targeted the role of religion in FW generation and prevention (Abdelradi, Citation2018; Aleshaiwi & Harries, Citation2021; Revilla & Salet, Citation2018), the focus has been on food consumption in households. The study by Elshaer et al. (Citation2021) stands out due to its survey of restaurant guests. However, it has examined the effect of religion on consumer FW behavior in general, rather than in the context of eating out. To the best of authors’ knowledge, no research has specifically considered the role of religion in waste(full/less) consumer behavior away from the home.

This study aims to partially fill the gap in knowledge on personal religious beliefs as a driver of FW generation and prevention in the context of out-of-home food consumption. The research questions, which the study has set to answer are as follows: (1) ‘To what extent do personal religious beliefs represent a powerful antecedent of wasteless consumer behaviour when cooking at home and when eating out?’ and (2) ‘What are the (other) determinants of waste(full/less) consumer behaviour regarding food and how can wasteless consumer behaviour be reinforced?’

The answers to these questions will be sought in the context of Iraq, a country in the Middle East whose society exhibits high religiosity levels. According to the US Department of State (Citation2019), 97% of Iraqis follow Islam with 55–60% belonging to the Shia and approximately 40% to the Sunni confessions. Concurrently, Iraq has a rapidly evolving market of out-of-home food consumption driven by postwar economic recovery (Muhialdin et al., Citation2021). As demonstrated by other rapidly developing economies (Wang et al., Citation2018), the evolution of eating out accelerates wastage of food in hospitality and foodservice provision. This calls for the design of preventative measures underpinned by scholarly research. The next section provides further background to this study to set the scene for subsequent data collection and analysis.

Literature review

Religion, religious values, and religiosity

Religiosity is defined as ‘a belief in God accompanied by a commitment to follow principles believed to be set forth by God’ (McDaniel & Burnett, Citation1990, p. 110) or as ‘the degree in which an individual adheres to [their] religious values, beliefs, and practices, and uses these in daily living’ (Worthington et al., Citation2003, p. 85). Religiosity is sometimes separated from the related term ‘spirituality’ which is defined as ‘an individual’s personal belief in religious teachings or intrinsic commitment to one’s faith’ (Good & Willoughby, Citation2006, p. 41). However, some sources do not make this separation explicit but distinguish between intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity instead (Wang et al., Citation2019). Intrinsic religiosity overlaps, in this case, with the concept of spirituality as it describes the situations whereby a believer ‘lives [their] religion’ as opposed to the situations whereby a believer ‘uses [their] religion’ (Allport, Citation1950, p. 434). In other words, intrinsic religiosity alongside spirituality implies that believers follow religious values and integrate these values into every aspect of their lives (Allport & Ross, Citation1967). In contrast, people adopt extrinsic religiosity to showcase to the others how religious they are even though, in reality, they do not strictly adhere to the religious values they choose to follow (Donahue, Citation1985). Extrinsic religiosity has a more utilitarian and symbolic rather than spiritual and personal meaning (Madni et al., Citation2016). For example, people with extrinsic religiosity visit church or mosque for praying and make public donations in order to get noticed (Mokhlis, Citation2009). In contrast, people with intrinsic religiosity can pray at home and donate money even if this donation becomes publicly unnoticed.

Although religiosity sounds similar to religion, the concepts differ. Religiosity represents a subset of religion or its logical product (Wang et al., Citation2019). Religion is positioned at a higher, macro level as it encourages individuals to follow its (religious) values and incorporate these values in daily activities that are undertaken at a lower, micro level of individual behavior (Madni et al., Citation2016). Religiosity represents a degree to which an individual has committed to follow a specific religion (Choi, Citation2010) and the level of personal religious commitment is defined by extrinsic and intrinsic religiosity. Religiosity is, thus, a qualitative and quantitative measure of religion; its qualitative dimension is exemplified by the extent to which believers choose to follow religious values while its quantitative dimension is exhibited by the number of religious followers (Worthington et al., Citation2003).

Individuals refer to religious leaders if they need guidance on how to follow religious values, rules and prescriptions (Anshel & Smith, Citation2014). Such religious leaders are represented by priests in Christianity, imams/ulamas in Islam or rabbis in Judaism, for example. Religious leaders explain religion’s postulates, provide interpretations of religious texts, offer spiritual compassion in a time of crisis and deliver various religious services to believers (Hirono & Blake, Citation2017). Religious leaders play an important societal role, especially in small and remote communities whereby they provide often the only means of education and sympathy. As recently argued by Koehrsen (Citation2021), religious leaders can even contribute to solving global environmental problems, such as climate change, by promoting environmental concern among the communities they serve. Thus, religious leaders represent an important stakeholder that has the power to guide individuals on how to behave in different life situations, including the need to conserve the environment (Boettcher, Citation2022).

Religiosity and FW

Food plays an important role in many religions as it provides a means of satisfying hunger and celebrating special occasions (Awan et al., Citation2015). Food is also a crucial marker of religious beliefs prescribing consumption of specific foodstuffs in particular times (Aktas et al., Citation2018). For example, halal food is a marker of Islam while kosher food represents Judaism (Cohen, Citation2021). Likewise, food consumption during Ramadan follows a dedicated pattern which distinguishes Islam believers from others (Trepanowski & Bloomer, Citation2010). As a result, religiosity represents an integral element of food-related research, which has been undertaken from the anthropological (Muhialdin et al., Citation2021), psychological (Cohen, Citation2021), nutritional (Alonso et al., Citation2018) and gastronomic (Battour & Ismail, Citation2016) perspectives.

Recently, the interplay between religiosity and food has also been studied from the sustainability viewpoint (Capone et al., Citation2014). This line of research has emerged because of public and political appreciation of the growing environmental externalities of global food consumption (Filimonau et al., Citation2020a). This appreciation has recognized the critical role played by religiosity in shaping patterns of consumer behavior at home and away (Elhoushy, Citation2020).

FW is a major environmental externality of food consumption at home and away (UNEP, Citation2021). FW occurs because of various reasons driven by the factors which can be controlled by consumers but also by the factors which can rest outside their direct control. For example, large amounts of food are wasted in households because of over-buying and poor meal planning (Yetkin Özbük et al., Citation2022) that is, factors that consumers are directly responsible for. Concurrently, FW can be generated at home because of spoilage driven, for instance, by a faulted fridge or chiller (Schanes et al., Citation2018). Technical faults cannot be directly controlled by consumers. As for food consumption outside the home, FW can occur on customer plates because of over-ordering, especially during social events (Filimonau et al., Citation2022). This wastage is usually under direct control of consumers. Concurrently, there are factors in food consumption away from the home, which customers are not accountable for. For example, portion size is defined by a provider of foodservice, and this size is not always communicated to restaurant guests effectively (McAdams et al., Citation2019). Hence, plate leftovers can occur because of excessive meals and the responsibility for this FW should be allocated to a foodservice provider rather than a consumer. Both controllable and uncontrollable FW generated at home and away should be reduced to enable global progress toward the goal of sustainability.

Given the manifold detrimental implications of FW for the global environment and society, it is important to understand its position in religious interpretations. Most religions explicitly prohibit FW: for example, it is considered ‘Haram’ (or ‘forbidden’) in Islam while the principle of Bal Tashchit commands not to destroy edible food in Judaism (Yetkin Özbük et al., Citation2022). Despite religions prescribe not to waste food, some believers do not follow this prescription, especially in the context of out-of-home food consumption. For example, a review by El Bilali and Ben Hassen (Citation2020) has established that significant amounts of food are wasted in the countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council even though the local populations are characterized by high levels of religiosity. This calls for a better understanding of the reasons behind such wasteful behavior and how these reasons link to the religious beliefs of consumers.

A handful of studies have examined the interplay between religiosity and FW behavior. Employing a survey method and using the prism of theory of planned behavior Elhoushy and Jang (Citation2021) and Elshaer et al. (Citation2021) have looked at the relationship between religious beliefs and FW reduction intentions of consumers in Egypt and Saudi Arabia, respectively. Elhoushy and Jang (Citation2021) have found that religiosity encourages FW reduction by affecting personal and pro-environmental norms. Similarly, Elshaer et al. (Citation2021) have shown that religiosity discourages FW generation by enhancing subjective norms and attitudes to reduce FW. Through a series of experiments conducted with US consumers, Minton et al. (Citation2020) have established that higher religiosity levels correlate with FW reduction intentions. Lastly, Chammas and Yehya (Citation2020) have investigated meal management practices in rural Lebanese households. They have found that religious beliefs encourage FW avoidance and frugality among women responsible for household cooking.

While the above studies are seminal and provide valuable insights into the role played by religiosity in FW reduction intentions, the findings can be improved with more nuanced research. First, the above investigations have revealed that religiosity exerts stronger influence on personal norms and attitudes rather than behavioral intentions to reduce FW. This calls for a better understanding of the factors contributing to the gap between personal norms alongside attitudes and wasteful consumer behavior. The survey method employed by most studies, due to its structured nature, does not facilitate such in-depth analysis. Second, previous investigations have not explicitly distinguished between intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity of consumers. Yet, these could have served as important predictors of FW behavior and explain the discrepancy between personal norms and FW reduction intentions. Lastly, previous studies have been concerned with food consumption in general, making no explicit differentiation between cooking at home and dining out, or focused on households. No research has been undertaken on the interplay between religiosity and FW behavior within the context of food consumption away from the home. Yet, such research can provide an interesting perspective and add to the growing body of sustainability, hospitality, and consumer behavior knowledge.

FW and its interpretation in Islam

Studies have pinpointed that Islam prohibits FW by presenting it as Haram (Aleshaiwi & Harries, Citation2021; Elhoushy & Jang, Citation2021; Yetkin Özbük et al., Citation2022). No dedicated research has, however, been undertaken to identify specific texts within the main Islam textbooks whereby FW behavior is showcased as sinful behavior. This current study has identified such texts and provided their interpretation. These texts can be used in future projects on FW and Islamic beliefs. For example, with appropriate adaptations, the texts can be employed as survey items or inform the design of interview protocols.

Supplementary Material (Appendix 1) contains quotes from the Quran and Hadith, which are concerned with FW. These quotes were first identified by the research team and then presented to the religious leaders (see explanations below) to confirm correctness of interpretation. The quotes prove that FW is explicitly seen as Haram in Islam, thus requiring all followers to act on its prevention. As this prevention does not always happen an analysis of the reasons why Muslims do not adhere to the religious prescriptions on FW, especially when eating out, is necessitated. The next section explains the research design that has been adopted to shed light on this topic.

Material and methods

Due to the exploratory nature of this study, a qualitative research design was adopted. Qualitative research aims to answer the questions ‘why’ and ‘how,’ thus offering scope for more nuanced examination and interpretation (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2012). Previous investigations on religiosity and FW have been underpinned by quantitative research methods with the related drawback of limited interpretative power. The survey questions are static in that they are designed to shed light on a very specific point and cannot be changed at short notice (Hennink et al., Citation2011). In contrast, qualitative research provides the opportunity to look deeper into a problem under scrutiny as its design is flexible and can be easily adjusted in line with emerging research needs (Silverman, Citation2013). For example, qualitative studies enable investigators to ask additional and/or follow-up questions, thus obtaining detailed answers and clarifications (Cresswell John, Citation2007).

Qualitative research design is suitable for this project given it seeks to address such complex research question as the role of religion in FW behavior. As shown by Aleshaiwi and Harries (Citation2021), answering this, rather sensitive, question may require a reflection on personal feelings and emotions. This is exactly what qualitative research is about as it enables study informants to self-reflect and speak freely and in detail (Adams et al., Citation2007) on the issues of high societal (i.e., FW) and personal (i.e., religion) importance.

Data were collected via semi-structured interviews conducted with Islam followers in Iraq. Study informants were recruited by purposive sampling. This recruitment method, despite the known drawback of non-representativeness (Cresswell John, Citation2007), is suitable for exploratory investigations. This is because exploratory research aims at providing an initial understanding of the issue in focus and outlining the main categories or themes of interest, rather than identifying and (re-)confirming the relationships between previously established variables (Silverman, Citation2013).

Although population representativeness is of less relevance for sampling in exploratory investigations (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2012), this study set to recruit informants in line with the main religious features of Muslims in Iraq. First, the study sought to capture opinions of the followers of the main Islamic confessions, that is, Shia and Sunni. Second, the study aimed at accounting for the different levels of religiosity among the Iraqi Muslims. To this end, study informants were recruited from three categories of believers: (1) Low religious commitment; described as irregular mosque attendance and basic knowledge of the main religious texts, such as the Quran and Hadith; (2) Medium religious commitment; described as regular mosque attendance and intermediate knowledge of the main religious texts; and (3) High religious commitment; described as frequent mosque attendance and advanced knowledge of the main religious texts. Prior to interviews, each study informant was asked to self-declare the level of personal religiosity and identify themselves with one of the three categories described above.

An interview protocol was developed of the material extracted from the literature review, interviews with Iraqi religious leaders (see explanations below) and analysis of the main religious texts (see Appendix 1). The ideas for the main interview questions were taken from Aleshaiwi and Harries (Citation2021), Elhoushy and Jang (Citation2021), and Minton et al. (Citation2019) and Yetkin Özbük et al., Citation2022). The interview questions revolved around the topics of (1) general FW awareness; (2a) FW behavior at home; and (2b) away from the home, including the (2c) factors contributing to FW generation and (2d) measures applied to avoid FW, if any, in each food consumption context. The interview questions also aimed at shedding light on (3) perception of FW as Haram; and (4) the role of various actors, such as policy-makers and hospitality and foodservice industry professionals, in encouraging wasteless consumer behavior in Iraq. As suggested by Hennink et al. (Citation2011), the interview protocol was constantly refined and updated in line with the new material extracted from each subsequent interview. The protocol was developed in English, that is, the language of the literature review. It was back translated in Arabic (Brislin, Citation1970), peer reviewed for quality by three independent academics majoring in religious studies, psychology, and consumer behavior research, and piloted with five volunteers. A copy of the interview protocol is provided in Supplementary Material (Appendix 2).

Interviews were conducted by a team of academics with expertise and experience in semi-structured interview design and administration. Before actual interviews, the team was briefed on FW and religiosity by academics majoring in the respective fields. This was to ensure they understood the subject matter in question, thus enabling the ‘immersion’ in the topic of field research (Rubin & Rubin, Citation2012).

Interviews were held face-to-face in different localities of Iraq in March–June 2021. In total, 22 interviews were conducted () and sample size was determined by perceived data saturation. Although data saturation is no longer deemed critical for qualitative research in social sciences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021), Thomson (2010 as cited in Marshall et al., Citation2013) recommends a range of 10–30 interviews, which this current study fits. On average, interviews lasted 53 minutes; they were digitally recorded for subsequent transcription, professionally transcribed verbatim and translated in English.

Table 1. Profile of the study informants (=22).

Importantly, to gain a first-hand understanding of how FW is interpreted by Islam, but also to obtain a perspective on the issue in focus from another key stakeholder, the project incorporated interviews with religious leaders in Iraq. To this end, two Shia and two Sunni ulamas were interviewed at the very start of the project. The interview protocols for the religious leaders were designed around the questions on (1) how Islam interprets FW and wasteful behavior; (2) why Muslims do not always follow the religious prescriptions on FW and its prevention; and (3) what ulamas, together with other actors, such as policy-makers and industry professionals, can do to discourage FW behavior at home and away. The material obtained from the semi-structured interviews with ulamas was used to inform the design of the interview protocol for Islam followers, as per above. The interviews with ulamas lasted, on average, 43 minutes and followed the same administrative procedure as in the case of interviews with Islam followers.

The project was subjected to research ethics clearance by the home institution of one of the research leads. In line with this clearance, prior to interviews, the informants were provided with detailed explanations of the study’s purpose and given an opportunity to ask clarifying questions. To overcome the potential effect of social desirability bias, full confidentiality and anonymity was guaranteed as suggested by Chung and Monroe (Citation2003). The informants were given freedom to stop the interview and withdraw the data at any time. No financial incentives were provided for participation.

The interview transcripts were analyzed thematically following a six-stage process outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2013). The transcripts were first read multiple times by two members of the research team. Coding was applied independently. Patterns in meanings were searched in an iterative process (Berg, Citation2009). Themes were identified and related back to the literature. The results of thematic analysis were cross-compared, and any inconsistencies identified were discussed and resolved. The guidelines by Schutz (Citation1972) on logical consistency and subjective interpretation were followed throughout the process of thematic analysis for data trustworthiness. Thematic analysis was facilitated by NVivo qualitative data analysis computer software (version 12).

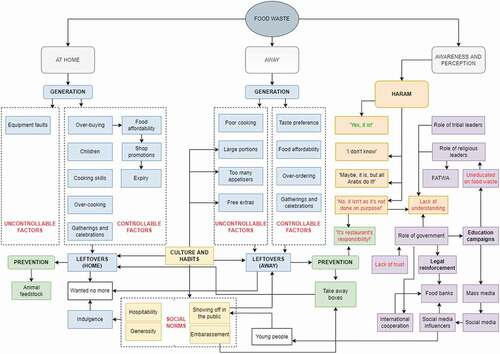

To ensure validity of thematic analysis, in line with the guidelines by Burnard (Citation1991), the final coding structure of the data was presented to three volunteers from the study informants. The coding structure was explained, and confirmation was sought on whether the interpretation was meaningful. The final coding structure of the thematic analysis is provided in . The next sections present the study’s findings and discuss its implications.

Findings

FW at home

Most study informants admitted wasting excessive quantities of food at home. This wastage was driven by a range of (un)controllable factors. Equipment failures due to, for instance, sudden power cuts represented the major factor beyond an individual’s control. Among the controllable factors over-buying driven by food affordability and shop promotions was dominant as well as the influence of children with their varied food preferences. Cooking mistakes represented another important factor alongside over-cooking. Over-cooking was particularly pronounced during (family and friends) gatherings, such as religious celebrations, weddings, and funerals. Social events generated the largest quantities of FW. The need to look after guests well, thus showcasing hospitality and generosity, to avoid social contempt or despise was cited as the main reason for staging wasteful social events:

‘It [FW] is so much; I think we waste 25-30% of the food we purchase. When family and friends come over, I’d say we waste up to 50%. We always over-cook because we’re worried of our guests gossiping about our poor hospitality. I think this is in our culture, no one wants to look like a ‘cheap’ person’ (C2)

Most food wasted by the study informants at home was represented by surplus meals, or so-called leftovers, produced due to over-cooking. Although some families chilled these leftovers for future consumption, most leftovers remained unconsumed and were eventually disposed of. The study informants referred to the leftovers as ‘unwanted’ because the family would crave for fresh, more indulgent food on the following day. The leftovers were labeled as ‘old food’ with perceived poor freshness. Some study informants even called the leftovers ‘unsafe’ expressing concern of the potential impact of preserved surplus food on health. As many Iraqi women stayed at home, they would cook fresh food for their family every single day, thus exacerbating the ‘unwantedness’ of leftovers.

Most study informants admitted doing little to nothing to prevent FW occurrence in households. Very few attempted to cook on demand but referred to this practice as rather ad hoc and ‘occasional.’ Some tried to recover value from wasted food by using it as animal feedstock for poultry, for example. The majority simply binned wasted food, including the leftovers.

In summary, the interviews revealed the important role of cultural habits and social norms in driving FW at home. The fear of public accusation of frugality/thriftiness and the routine of cooking fresh food from the new represented the main causes of why excessive meal leftovers were generated but rarely consumed. The negative effect of cultural and social norms on FW generation will be discussed in more detail in the next sub-section.

FW away from the home

Most study informants admitted wasting significant quantities of food when eating out. Similar to the household context, the drivers of this wastage were categorized as (un)controllable. However, dissimilar to the case of FW generation at home, there were more factors in food wastage beyond consumer’s control and their effect was stronger in the context of dining out.

Poor cooking was something that the study informants could not control in restaurants, that is, the quality of dishes was dependent on the skill of chefs. The largest effect was, however, exerted by such uncontrollable factors as large meal portions with free extras, usually in the form of appetizers and drinks. These factors were especially pronounced in ‘eastern’ Iraqi restaurants specializing in serving dishes from national cuisine. According to the study informants, large portions were in part attributed to cultural traditions as ‘eastern’ restaurants in Iraq took pride in providing generous portions of food to reflect ‘eastern’ hospitality. Large portions resulted in excessive leftovers:

‘There’re different reasons [for why food remains uneaten in restaurants]. First, because of the large size of the dishes and the crazy number of side dishes which are impossible to finish. It’s the culture of foodservice in Iraq. One main dish comes with 12-15 sides, it’s unreasonable. They serve the sides before the food and make the customer full. When the main dish comes, the customer will eat the meat first and waste the others, like bread and rice. We say “The eye should be saturated before the stomach” …’ (C13)

The controllable drivers of FW in Iraqi restaurants were represented by taste preferences and perceived food affordability. However, the largest effect was exerted by over-ordering, especially during social events. Younger consumers would order excessive amounts of food in order to show off in the public. Parallels could be drawn between the controllable factors in FW generation at home and away, that is, cultural and social norms prompted the Iraqis to order more food than required. Most of this food would remain uneaten:

‘The Iraqi culture and generosity are a problem; we think that by serving large amounts of food we will honour the person who we’ve invited for lunch or to an event’ (C12)

‘Celebrations, like weddings and funerals, they are very wasteful. In these celebrations we try to impress people and there is no common sense. The Iraqis like to show our generosity and wealth. I can tell you this is the culture in the country not only in this city. For example, recently I’ve attended the funeral. They slaughtered 750 sheep in one day to feed the village people. 70% was then thrown in the garbage’ (C1)

Over-ordering and oversized dishes in Iraqi restaurants generated excessive quantities of leftovers. When prompted on the need to prevent the occurrence of these leftovers, most study informants rejected their responsibility for prevention. Foodservice providers were expected to reduce the amounts of wasted food as they were blamed for serving large portions. Most Iraqis did not recognize their role in FW prevention when eating out. Some study informants requested the leftovers to be packed and taken away. However, the majority refrained from this practice in the public, especially when attending social events, due to embarrassment. This indicated the negative effect of social norms on wasteless consumer behavior when eating out in Iraq.

Another problem with taking leftovers home was in their perceived ‘unwantedness,’ as discussed earlier. Similar to the home context, the Iraqis would often refuse consuming restaurant take-aways on the following day with these leftovers eventually going to waste. Instead of prevention, leftovers taken home would simply transfer the problem of FW from restaurants to households:

‘I sometimes take restaurant leftovers home. The problem is that we don’t eat the same food on next day in most of the cases as we, as normal people, will desire other, fresher food. The old restaurant food can’t be kept for long in the fridge, so it’ll be eventually disposed of without eating’ (C19)

In summary, cultural and social norms represent a major driver of FW in Iraq when eating out. Interestingly, there is a clear overlap between the realms of food consumption at home and away. The concept of ‘unwanted’ leftovers persists in both realms and transfers the FW challenge from restaurants to households. Cultural and social norms often come in conflict with religious values as explained in the next sub-section.

FW as Haram

The study informants had different opinions on whether FW away from the home should be categorized as Haram. Some were affirmative that FW was prohibited by Islam regardless of the context of food consumption, i.e. ‘The Quran has a clear instruction on that not to waste, but maybe only 50% of the Muslim know that and care about’ (C2). Some were uncertain, that is, ‘I’m honestly not sure. I think it [FW] is hated but it’s not the level of Haram’ (C9). Some study informants were categorical in that FW generation away from the home should not be considered Haram as they did not waste food on purpose, that is, ‘It’s not Haram since it’s beyond our control’ (C14). These study informants blamed foodservice providers for not following the religious prescriptions, thus transferring responsibility for wasted food onto restaurateurs. Lastly, some admitted that FW might have been forbidden by the religious values, but they would still waste food regardless as ‘this is what the other Iraqis do,’ that is, ‘Oh, well, what to do, maybe it’s Haram, but many people waste food because personal comfort and social reputation are more important’ (C16).

The last quote indicates that cultural and social norms clash with religiosity when it comes to the problem of FW generation away from the home. When probed, many study informants agreed that the Iraqis were more concerned of their social status than religious beliefs. This suggests that many Iraqis have extrinsic religiosity as, despite practicing Islam, they do not adhere to its prescriptions. Extrinsic religiosity may therefore represent an important inhibitor of FW prevention when eating out. Measures need to be undertaken to reduce the effect of extrinsic religiosity. Ideally, these measures should be concerned with converting extrinsic religiosity into intrinsic. This is when the religious beliefs can potentially outweigh the negative influence of cultural and social norms on FW behavior:

‘Social life is more important for the Iraqi people compared to the religion; we’re more concerned about how to satisfy our friends … Culture is another reason why we waste food and it’s far from religion today. Some people forget what Islam is about. They pretend to follow the religion, but they don’t even differentiate between Halal and Haram. They follow desires only and the majority lose control when eating, forget about the religion … That’s why we say, “Customs and traditions prevail over the religion” ‘ (Ulama)

Extrinsic religiosity may also partially explain limited understanding of the concept of Haram among the Iraqis. Interestingly, no association was established between the levels of religious commitment of the study informants and their knowledge of FW as Haram. FW was not considered forbidden equally among the high and low committed individuals. This suggests that public awareness of FW in general, and FW as a sinful act, should be enhanced among the Iraqi Muslims regardless of their religiosity levels.

When probed on the role of various actors in enhancing public awareness of FW, most study informants spoke about religious leaders, such as ulamas. These actors have the power to influence the followers’ attitudes and behaviors and ulamas were encouraged to raise the issue of FW in public prayers. Some study informants even spoke about the fatwas [religious rulings] on FW, which could be issued by ulamas to emphasize the need to save food from waste, at home and away:

‘The religious leaders are very important, and they can make change. I think if they could combine the Solat al-Jumaat [Friday prayer] with the Khutbah [primary formal occasion for public preaching in Islam], they’d change the behaviour of people by explaining that FW is a sin in Islam’ (C6)

However, the interviews with some study informants and ulamas revealed that not all religious leaders in Iraq were educated on the issue of FW. This suggests the need to raise awareness of ulamas as well as the public. The national government was seen instrumental in the design of educational campaigns on FW prevention. These campaigns could be broadcast on mass media, especially social media, thus increasing their appeal to the different categories of consumers. The idea of engaging social media influencers was discussed to make educational campaigns more appealing for younger consumers.

The role of government was also seen critical in learning from international experience in FW prevention. This experience was particularly needed in Iraq in the context of food banks and FW recycling. Some study informants and ulamas spoke about food banks to fight food poverty but claimed the Iraqi government did nothing to redistribute surplus food from restaurants and supermarkets to people in need.

However, many study informants also spoke about the lack of trust they had in the ability of the national government to design and execute meaningful societal changes in Iraq. This lack of trust occurred in the aftermath of the recent military conflicts experienced by the Iraqi population. Hence, the study informants argued about the need to combine efforts of the national government and religious leaders. Such combined approach could exert a stronger effect as it would target Muslims with high and low levels of religious beliefs, but also Muslims with intrinsic and extrinsic religiosity.

Lastly, the study informants spoke about the need to engage tribal leaders in the design and administration of public awareness raising campaigns on FW prevention in Iraq. Tribal leaders have the power to issue local rulings and these rulings could concern FW when eating out. However, many tribal leaders, like religious leaders, may have limited knowledge of the FW issue themselves. This suggests that educational campaigns of the national government should also target tribal leaders:

‘Our traditions are deeply embedded in the tribal culture, such as generosity and hospitality. If the invited people leave the table and it’s still full of food, this shows that we are masters, and we respect our guests. So, tribal leaders can play a role in changing people’s attitudes. It’ll not be a quick process to change people’s minds, but tribal leaders are as important as anyone else’ (C17)

Discussion and conclusions

Theoretical implications

This study makes a three-fold contribution to theory. First, unlike previous, quantitative investigations that have established correlation between religiosity and consumer intentions to prevent FW (Elhoushy & Jang, Citation2021; Elshaer et al., Citation2021; Minton et al., Citation2020), this qualitative study has showcased limited effect of religiosity on wasteless consumer behavior at home and away. Although the major Islam textbooks prescribe FW as Haram, Muslims are not always aware of this prescription and, therefore, waste a lot of food. Further, even if Islam followers associate Haram with FW, they do not necessarily exhibit wasteless behavior. This is a result of the influence exerted by the (1) type of religiosity, that is, intrinsic versus extrinsic; and (2) cultural, social, and habitual factors in food consumption.

Similar to Elshaer et al. (Citation2021) who first established this phenomenon among Muslims in Saudi Arabia, this current study has demonstrated that many Iraqi Muslims showcase extrinsic religiosity. Extrinsic religiosity implies that the individuals do not ‘live the religion’ (Allport, Citation1950, p. 434) which results in wasteful consumer behavior. Besides, cultural habits and social expectations of being a good host prompt the Iraqi Muslim to over-order food in restaurants, thus generating wastage. This suggests that cultural traits, social norms and habits inhibit the religious beliefs of many Islam followers, especially in the case of individuals with extrinsic religiosity. This also indicates that many Iraqi Muslims prefer choosing the cultural traits promoting indulgence (=hospitality) rather than the cultural traits imposing restrictions (=religious beliefs), which is similar to the propositions by Minton et al. (Citation2020). This finding implies that high religiosity levels of populations cannot be considered the default or sufficiently good predictors of wasteless consumer behavior. The role of other socio-demographic, psychographic and, particularly, cultural and social factors should be acknowledged, and their exact effect should be carefully investigated.

Second, this study adds to the literature on the role of social norms in FW behavior away from the home. Previous investigations have considered social norms as predictors of positive, that is, toward FW prevention, behavioral patterns when eating out (Coşkun & Özbük, Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020; Stöckli et al., Citation2018a). In other words, previous investigations have argued that hospitality and foodservice consumers are more likely to save food from waste if they know that wasting food represents a socially undesirable act. This current study demonstrates, however, that social norms can also exert a negative effect on FW behavior. The social norm which requires the Iraqis to be generous hosts prompts over-ordering, especially during social events, with subsequent wastage.

This finding adds to the body of knowledge which has recently highlighted the need to better understand possible negative effect of social norms on consumer intention to take food leftovers home (Hamerman et al., Citation2018; Sirieix et al., Citation2017; Talwar et al., Citation2021a). This current study showcases how negative social norms can contribute to FW generation before food is even ordered, that is, ex-ante a foodservice event, as opposed to during or after (ex post) foodservice provision. Further, this current study has also indicated that, for many Iraqi Muslims, restaurant food leftovers become unwanted before they even get generated, thus resulting in consumer unwillingness to take these leftovers home. Ex post negative social norms can partially explain why the leftovers are unwanted. This adds empirical evidence to the finding by Aleshaiwi and Harries (Citation2021) who first revealed the phenomenon of unwanted food leftovers in Saudi Arabia albeit in the context of household food consumption. It is unclear if this phenomenon is only related to the culture of the Middle East and future research should therefore test the effect of unwanted restaurant food leftovers and the psychographic factors behind consumer perception of their ‘unwantedness’ in other socio-economic contexts.

Lastly, this current study has demonstrated that extrinsic religiosity reinforces the negative effect of cultural and social norms on FW behavior away from the home. This means that the individuals who choose to ‘use the religion’ (Allport, Citation1950, p. 434) are more likely to exhibit wasteful consumer behavior in presence of negative cultural and social norms. This is particularly pronounced, for example, in the case of religious gatherings and celebrations when over-ordering is not only culturally encouraged and socially accepted, but even socially expected in order to ‘show off.’ This has been previously demonstrated during major religious festivals in Iraq (Abdulredha et al., Citation2018) and this current study provides a theoretical explanation to such wasteful behavior of some Islam followers.

This finding suggests that campaigns to raise public awareness of FW in Iraq (see next sub-section) should first target the individuals with extrinsic religiosity. The individuals with intrinsic religiosity may have more power to withstand the negative effect of cultural and social norms. Future research should, however, examine how far the power of intrinsic religiosity can stretch and at what stage social norms and cultural traits over-take the religious values. Interventions will need to be designed by various actors to counteract or, at least, delay the effect of social norms and cultural traits on FW behavior of Islam followers.

Practical implications – hospitality and foodservice providers

Hospitality and foodservice providers represent a crucial actor in preventing FW generation away from the home in Iraq. The findings of this study suggest that, to prevent FW, hospitality and foodservice administrations should reduce size of meals they currently offer. Many study informants spoke about excessive restaurant meals as one of the uncontrollable drivers of leftovers. Consumers exert limited or no control over this driver, thus pinpointing the importance of corrective action from hospitality and foodservice providers. Evidence from other markets of out-of-home food consumption (Ge et al., Citation2018; Wansink & van Ittersum, Citation2013) demonstrates that portion size reduction, when coupled with an appropriate reduction in meal price, can prevent leftovers in restaurants while maintaining customer satisfaction. In Iraq, however, this intervention will only be successful if applied by most hospitality and foodservice operators at once. If portion size is only reduced by a small number of restaurants, such intervention can simply disadvantage these restaurants in the highly competitive market. The Iraqis, who are culturally accustomed to large portions, may boycott the hospitality and foodservice operators which have committed to offering smaller meals to prevent leftovers. Hence, future research should identify the drivers of intra-sectoral shift toward reduced portions in Iraq. This research should target managers of different types of hospitality and foodservice enterprises and examine the effect of such factor as governmental (dis)incentives.

Further, to make portion size reductions successful in Iraq, hospitality and foodservice operators should make an explicit reference to personal disbenefits of over-ordering. When communicating the need to reduce portion size to customers, the emphasis should be given to personal health issues, such as obesity, as opposed to societal and environmental issues, such as FW. Research shows that consumers tend to prioritize personal over societal well-being (Cohen & Kantenbacher, Citation2020). Given that some study informants spoke about growing health concerns among the (especially rich and educated) Iraqis, the reference to the positive health implications of ordering less food may become more persuasive.

If hospitality and foodservice operators fail to successfully implement portion size reduction and/or convince consumers of the health disbenefits of over-ordering, then they should concentrate on rescuing leftovers. Unfinished meals can be taken by guests home but this rescuing method will not necessarily succeed in Iraq due to the effect of negative social norms as discussed earlier. In line with this effect, the Iraqis do not ask for take-away boxes in fear of ‘losing face’ as suggested by Filimonau et al. (Citation2020b). To reduce the effect of negative social norms, hospitality and foodservice providers in Iraq should make it normal practice for staff to offer take-away boxes to guests pro-actively. Staff can even be trained in consumer psychology to identify the most appropriate moments during foodservice provision when take-away boxes can be offered. Alternatively, as mentioned by some study informants, customers can be given an option to self-pack meal leftovers. Importantly, in the case of gatherings and celebrations, take-away boxes should be offered at the end of foodservice, that is, when most guests have gone, to avoid embarrassment. Not only will the proactive offer of take-away boxes reduce FW, but it can also increase customer satisfaction, especially among the individuals with intrinsic religiosity and high FW awareness, thus, potentially, enhancing guest loyalty.

Importantly, the option of take-away boxes in Iraqi restaurants will only appeal to consumers who are comfortable with eating leftovers on the following day. Alternative strategies should be designed to reduce leftovers among those customers who perceive (home or restaurant) food leftovers as ‘unwanted’ as discussed earlier. Such strategies can be exemplified by incentives for clean plates as suggested by (Katare et al., Citation2019). Future research should test the potential effect of such incentives in the Iraqi context, preferably via experimental investigations.

Practical implications – other actors

The national government represents another crucial actor to prevent FW in Iraq, at home and away. Although some study informants, rather understandably, spoke about the lack of trust they had in governmental institutions, the majority acknowledged the need to engage government in FW prevention. The Iraqi government should foremost aim to educate citizens and increase public awareness of the FW challenge among restaurant guests, but also hospitality and foodservice administrations, religious and tribal leaders. The topic of FW should be integrated into school and University curricula. It should also be broadcast on the main media, especially social media platforms as these have the power to influence FW behavior of younger generations (Narvanen et al., Citation2018). To increase awareness of foodservice operators and religious leaders, ad hoc training courses and master classes on FW prevention should be organized. This finding is in line with research by Pinto et al. (Citation2018) that have long emphasized the importance of public and industry education as a cornerstone of FW prevention. The unique contribution of the current study is in that it has showcased the need to educate religious and tribal leaders as these have the power to influence consumer behavior in societies with high levels of religiosity and tribalism.

Government should also design measures to reinforce FW-related legislation in Iraq. The lack of effective legal framework on solid waste treatment hampers FW management, especially in developing countries (Eriksson et al., Citation2020), thus calling for urgent policy interference. Government should also study the international experience in FW prevention and recycling to apply it, with appropriate adaptations, in the Iraqi context. In particular, the international experience in food rescue should be examined (see, for example, Hecht & Neff, Citation2019) to design a nation-wide chain of food banks and/or surplus food redistribution centers in Iraq. Not only will this policy intervention reduce FW occurring because of over-production in restaurants, but it can also alleviate poverty, which represents a critical challenge in postwar Iraq. Future research on the feasibility of food banks in Iraq is, however, required. This research should explore if the concept of ‘unwanted’ leftovers established in this current study can negatively influence perceptions of prospective food bank users. If people in need also perceive food leftovers as ‘unwanted,’ then the idea of food banks may become unsuccessful in Iraq. In-depth investigation of this topic is necessitated.

The unique finding of this study is in highlighting the critical role of religious leaders in FW prevention in Iraq. Religious leaders can become a mouthpiece of governmental campaigns to raise public awareness of FW by promoting the need for wasteless behavior to the Islam followers. In the Arab world, religious leaders can also issue a ruling (=fatwa) to prescribe FW prevention in local communities. The religious individuals may obey to this ruling, especially if they exhibit intrinsic religiosity and/or high levels of religious commitment. Religious leaders can also inspire hospitality and foodservice administrations to invest in FW prevention. This will create a multiplying effect whereby governmental efforts to prevent FW are coupled with efforts of religious leaders.

Lastly, tribal leaders have been identified as important actors to prevent FW in Iraq. Given that the Iraqi society is conservative and follows the rules of tribes, tribal leaders can exert a positive effect on wasteless consumer behavior by emphasizing the need for FW prevention. Tribal leaders can also require local hospitality and foodservice administrations to rescue surplus food for the poor. The maximum effect will be achieved when tribal leaders combine their efforts with other actors, that is, the Iraqi government, hospitality and foodservice administrations and religious leaders, as discussed above.

Limitations and future research directions

The key limitation of the current study is its qualitative nature. Small samples of exploratory, qualitative research prevent generalizability of results. This highlights the need for a follow-up, confirmatory investigation which should be grounded on the preliminary findings of the current project. A quantitative, confirmatory study can be undertaken in Iraq or other countries with large populations of Islam followers. Such studies can differentiate between the various interpretations of Islam, such as ‘liberal’ or ‘progressive’ in Turkey or Iran and ‘conservative’ in Afghanistan and Saudi Arabia. Future research should examine perceptions of a larger sample of religious leaders, in Iraq and beyond, on the role they can/should play in FW prevention at home and away. Such research can incorporate perspectives of non-Islamic religious leaders, such as priests in Christianity and rabbis in Judaism. Perceptions of other relevant actors, such as managers of hospitality and foodservice enterprises, tribal leaders and policy-makers in Iraq on FW prevention should also be explored. Lastly, this qualitative research should be replicated in societies with other religions which consider FW sinful, such as Christianity, Judaism, and Hinduism.

Note on contributions

Viachaslau Filimonau Conceptualization, Data analysis, Writing – original draft

Hana Kadum Conceptualization, Project administration, Data collection, Writing - review and editing

Nameer K. Mohammed Conceptualization, Project administration, Data collection, Writing - review and editing

Hussein Algboory Conceptualization, Project administration, Data collection, Writing - review and editing

Jamal M. Qasem Conceptualization, Project administration, Data collection, Writing - review and editing

Vladimir A. Ermolaev Data analysis, Writing - review and editing

Belal J. Muhialdin Conceptualization, Project administration, Data curation, Resources, Validation, Writing - review and editing

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (37.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Raw data can be requested by email from the corresponding author of this study.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2022.2080145

References

- Abdelradi, F. (2018). Food waste behaviour at the household level: A conceptual framework. Waste Management, 71, 485–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2017.10.001

- Abdulredha, M., Al Khaddar, R., Jordan, D., Kot, P., Abdulridha, A., & Hashim, K. (2018). Estimating solid waste generation by hospitality industry during major festivals: A quantification model based on multiple regression. Waste Management, 77, 388–400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.04.025

- Adams, J., Khan, H. T. A., Reaside, R., & White, D. (2007). Research methods for graduate business and social science students. Sage.

- Aktas, E., Sahin, H., Topaloglu, Z., Oledinma, A., Huda, A. K. S., Irani, Z., Sharif, A. M., van’t Wout, T., & Kamrava, M. (2018). A consumer behavioural approach to food waste. Journal of Enterprise Information Management, 31(5), 658–673. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEIM-03-2018-0051

- Aleshaiwi, A., & Harries, T. (2021). A step in the journey to food waste: How and why mealtime surpluses become unwanted. Appetite, 158, 105040. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.105040

- Allport, G. W. (1950). The individual and his religion: A psychological interpretation. Macmillan.

- Allport, G. W., & Ross, J. M. (1967). Personal religious orientation and prejudice. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 5(4), 432–443. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0021212

- Alonso, B. E., Cocks, L., & Swinnen, J. (2018). Culture and Food Security. Global Food Security, 17, 113–127. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3052252

- Anshel, M. H., & Smith, M. (2014). The role of religious leaders in promoting healthy habits in religious institutions. Journal of Religion and Health, 53(4), 1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-013-9702-5

- Arli, D., & Tjiptono, F. (2014). The end of religion? Examining the role of religiousness, materialism, and long-term orientation on consumer ethics in Indonesia. Journal of Business Ethics, 123(3), 385–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1846-4

- Arli, D., Tkaczynski, A., & Anandya, D. (2019). Are religious consumers more ethical and less Machiavellian? A segmentation study of Millennials. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 43(3), 263–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12507

- Aschemann-Witzel, J., de Hooge, I., Amani, P., Bech-Larsen, T., & Oostindjer, M. (2015). Consumer-related food waste: Causes and potential for action. Sustainability, 7(6), 6457–6477. https://doi.org/10.3390/su7066457

- Awan, H. M., Siddiquei, A. N., & Haider, Z. (2015). Factors affecting Halal purchase intention-evidence from Pakistan’s Halal food sector. Management Research Review, 38(6), 640–660. https://doi.org/10.1108/MRR-01-2014-0022

- Battour, M., & Ismail, M. N. (2016). Halal tourism: Concepts, practises, challenges and future. Tourism Management Perspectives, 19, 150–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2015.12.008

- Berg, B. L. (2009). Qualitative research methods for the social science. Pearson Education.

- Boettcher, M. (2022). A leap of Green faith: The religious discourse of socio-ecological care as an earth system governmentality. Journal of Environmental Policy & Planning, 24(1), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/1523908X.2021.1956310

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2013). Successful qualitative research. A practical guide for beginners. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-Translation for Cross-Cultural Research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910457000100301

- Burnard, P. (1991). A method of analysing interview transcripts in qualitative research. Nurse Education Today, 11(6), 461–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/0260-6917(91)90009-Y

- Capone, R., Bilali, H. E., Debs, P., Gianluigi, C., & Noureddin, D. (2014). Food system sustainability and food security: Connecting the dots. Journal of Food Security, 2(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.12691/jfs-2-1-2

- Chammas, G., & Yehya, N. A. (2020). Lebanese meal management practices and cultural constructions of food waste. Appetite, 155, 104803. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104803

- Chen, H. S., & Jai, T.-M. (2018). Waste less, enjoy more: Forming a messaging campaign and reducing FW in restaurants. Journal of Quality Assurance in Hospitality and Tourism, 19(4), 495–520. https://doi.org/10.1080/1528008X.2018.1483282

- Choi, Y. (2010). Religion, religiosity, and South Korean consumer switching behaviors. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 9(3), 157–171. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.292

- Chung, J., & Monroe, G. S. (2003). Exploring social desirability bias. Journal of Business Ethics, 44(4), 291–302. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1023648703356

- Cohen, S. A., & Kantenbacher, J. (2020). Flying less: Personal health and environmental co-benefits. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(2), 316–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1585442

- Cohen, A. B. (2021). You can learn a lot about religion from food. Current Opinion in Psychology, 40, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2020.07.032

- Coşkun, A., & Özbük, R. M. Y. (2020). What influences consumer food waste behavior in restaurants? An application of the extended theory of planned behavior. Waste Management, 117, 170–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2020.08.011

- Cresswell John, W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Lincoln: Sage Publications.

- Donahue, M. J. (1985). Intrinsic and extrinsic religiousness: Review and meta analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48(2), 400–419. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.48.2.400

- El Bilali, H., & Ben Hassen, T. (2020). Food waste in the countries of the gulf cooperation council: A Systematic Review. Foods, 9(4), 463. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9040463

- Elhoushy, S. (2020). Consumers’ sustainable food choices: Antecedents and motivational imbalance. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 89, 102554. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102554

- Elhoushy, S., & Jang, S. (2021). Religiosity and food waste reduction intentions: A conceptual model. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 45(2), 287–302. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcs.12624

- Elshaer, I., Sobaih, A. E. E., Alyahya, M., & Elnasr, A. A. (2021). The impact of religiosity and food consumption culture on FW Intention in Saudi Arabia. Sustainability, 13(11), 6473. https://doi.org/10.3390/su13116473

- Eriksson, M., Giovannini, S., & Ghosh, R. K. (2020). Is there a need for greater integration and shift in policy to tackle food waste? Insights from a review of European Union legislations. SN Applied Sciences, 2(8), 1347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42452-020-3147-8

- Filimonau, V., & De Coteau, D. (2019). Food waste management in hospitality operations: A critical review. Tourism Management, 71, 234–245. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.10.009

- Filimonau, V., Matute, J., Kubal-Czerwinska, M., Krzesiwo, K., & Mika, M. (2020a). The determinants of consumer engagement in restaurant food waste mitigation in Poland: An exploratory study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 247, 119105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119105

- Filimonau, V., Zhang, H., & Wang, L. (2020b). Food waste management in Shanghai full-service restaurants: A senior managers’ perspective. Journal of Cleaner Production, 258, 120975. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.120975

- Filimonau, V., Matyakubov, U., Allonazarov, O., & Ermolaev, V. A. (2022). Food waste and its management in restaurants of a transition economy: An exploratory study of Uzbekistan. Sustainable Production and Consumption, 29, 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spc.2021.09.018

- Ge, L., Almanza, B., Behnke, C., & Tang, C.-H. (2018). Will reduced portion size compromise restaurant customer’s value perception? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 70, 130–138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2017.10.026

- Good, M., & Willoughby, T. (2006). The role of spirituality versus religiosity in adolescent psychosocial adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35(1), 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-9018-1

- Hamerman, E. J., Rudell, F., & Martins, C. M. (2018). Factors that predict taking restaurant leftovers: Strategies for reducing food waste. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 17(1), 94–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/cb.1700

- Hecht, A. A., & Neff, R. A. (2019). Food Rescue Intervention Evaluations: A Systematic Review. Sustainability, 11(23), 6718. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11236718

- Hennink, M., Hutter, I., & Bailey, A. (2011). Qualitative Research Methods. Sage.

- Hirono, T., & Blake, M. E. (2017). The role of religious leaders in the restoration of hope following natural disasters. SAGE Open, 7(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017707003

- Katare, B., Wetzstein, M., & Jovanovic, N. (2019). Can economic incentive help in reducing food waste: Experimental evidence from a university dining hall. Applied Economics Letters, 26(17), 1448–1451. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504851.2019.1578856

- Kim, M. J., Hall, C. M., & Kim, D.-K. (2020). Predicting environmentally friendly eating out behavior by value-attitude-behavior theory: Does being vegetarian reduce food waste? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 28(6), 797–815. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1705461

- Koehrsen, J. (2021). Muslims and climate change: How Islam, Muslim organizations and religious leaders influence climate change perceptions and mitigation activities. WIREs Climate Change, 12(3), e702. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.702

- Madni, A. R., Hamid, N. A., & Rashid, S. M. (2016). An association between religiosity and consumer behavior: A conceptual piece. The Journal of Commerce, 8(3), 58–65. https://www.proquest.com/docview/1835824433?pq-origsite=gscholar&fromopenview=true

- Marshall, B., Cardon, P., Poddar, A., & Fontenot, R. (2013). Does sample size matter in qualitative research?: A review of qualitative interviews in IS research. Journal of Computer Information Systems, 54(1), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/08874417.2013.11645667

- Massow, M. V., & McAdams, B. (2016). Table scraps: An evaluation of plate waste in restaurants. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 18(5), 437–453. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020.2015.1093451

- Mathras, D., Cohen, A. B., Mandel, N., & Mick, D. G. (2016). The effects of religion on consumer behavior: A conceptual framework and research agenda. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 26(2), 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2015.08.001

- McAdams, B., von Massow, M., Gallant, M., & Hayhoe, M.-A. (2019). A cross industry evaluation of food waste in restaurants. Journal of Foodservice Business Research, 22(5), 449–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/15378020.2019.1637220

- McDaniel, S. W., & Burnett, J. J. (1990). Consumer religiosity and retail store evaluative criteria. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 18(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02726426

- Minton, E. A., Johnson, K. A., & Liu, R. L. (2019). Religiosity and special food consumption: The explanatory effects of moral priorities. Journal of Business Research, 95, 442–454. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.041

- Minton, E. A., Johnson, K. A., Vizcaino, M., & Wharton, C. (2020). Is it godly to waste food? How understanding consumers’ religion can help reduce consumer FW. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 54(4), 1246–1269. https://doi.org/10.1111/joca.12328

- Mokhlis, S. (2009). Relevancy and measurement of religiosity in consumer behavior research. International Business Research, 2(3), 75–84. https://doi.org/10.5539/ibr.v2n3p75

- Muhialdin, B. J., Filimonau, V., Qasem, J. M., & Algboory, H. (2021). Traditional foodstuffs and household food security in a time of crisis. Appetite, 165, 105298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105298

- Narvanen, E., Mesiranta, N., Sutinen, U.-M., & Mattila, M. (2018). Creativity, aesthetics and ethics of food waste in social media campaigns. Journal of Cleaner Production, 195, 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.05.202

- Pinto, R. S. , dos Santos Pinto, R. M. , Melo, F. F. S. , Campos, S. S. , & Cordovil, C. M. D. S. (2018). A simple awareness campaign to promote food waste reduction in a University canteen. Waste Management, 76, 28–38.

- Porpino, G. (2016). Household food waste behavior: Avenues for future research. Journal of the Association for Consumer Research, 1(1), 41–51. https://doi.org/10.1086/684528

- Revilla, B. P., & Salet, W. (2018). The social meaning and function of household food rituals in preventing FW. Journal of Cleaner Production, 198, 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.06.038

- Rubin, H. J., & Rubin, I. S. (2012). Qualitative interviewing: The art of hearing data. Sage.

- Schanes, K., Dobernig, K., & Gözet, B. (2018). Food waste matters-a systematic review of household food waste practices and their policy implications. Journal of Cleaner Production, 182, 978–991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2018.02.030

- Schutz, A. (1972). The problem of social reality (Collected Papers, Volume 1) M. Natanson (Ed.). The Hague: Marinus Nijhoff.

- Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook. SAGE.

- Sirieix, L., Lala, J., & Kocmanova, J. (2017). Understanding the antecedents of consumers’ attitudes towards doggy bags in restaurants: Concern about food waste, culture, norms and emotions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 34, 153–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.10.004

- Stöckli, S., Dorn, M., & Liechti, S. (2018a). Normative prompts reduce consumer food waste in restaurants. Waste Management, 77, 532–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wasman.2018.04.047

- Stöckli, S., Niklaus, E., & Dorn, M. (2018b). Call for testing interventions to prevent consumer food waste. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 136, 445–462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.03.029

- Suki, N. M., & Suki, N. M. (2015). Does religion influence consumers’ green food consumption? Some insights from Malaysia. Journal of Consumer Marketing, 32(7), 551–563. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCM-02-2014-0877

- Talwar, S., Kaur, P., Yadav, R., Bilgihan, A., & Dhir, A. (2021a). What drives diners’ eco-friendly behaviour? The moderating role of planning routine. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102678

- Talwar, S., Kaur, P., Okumus, B., Ahmed, U., & Dhir, A. (2021b). Food waste reduction and taking away leftovers: Interplay of food-ordering routine, planning routine, and motives. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 98, 103033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.103033

- Trepanowski, J. F., & Bloomer, R. J. (2010). The impact of religious fasting on human health. Nutrition Journal, 9(1), 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2891-9-57

- UNEP, 2021. UNEP FW Index Report 2021. Available from: https://www.unep.org/resources/report/unep-food-waste-index-report-2021 [Accessed 02 August 2021].

- US Department of State, 2019. 2019 report on international religious freedom: Iraq. Available from: https://www.state.gov/reports/2019-report-on-international-religious-freedom/iraq/ [Accessed 02 August 2021].

- Vizzoto, F., Tessitore, S., Testa, F., & Iraldo, F. (2021). Plate waste in foodservice outlets: Revealing customer profiles and their support for potentially contentious measures to reduce it in Italy. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 174, 105771. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2021.105771

- Wang, L., Xue, L., Li, Y., Liu, X., Cheng, S., & Liu, G. (2018). Horeca food waste and its ecological footprint in Lhasa, Tibet, China. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 136, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2018.04.001

- Wang, L., Wong, P. P. W., & Elangkovan, N. A. (2019). The influence of religiosity on consumer’s green purchase intention towards green hotel selection in China. Journal of China Tourism Research, 16(3), 319–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2019.1637318

- Wansink, B., & van Ittersum, K. (2013). Portion size me: Plate-size induced consumption norms and win-win solutions for reducing food intake and waste. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, 19(4), 320–332. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035053

- Wilkins, S., Butt, M. M., Shams, F., & Pérez, A. (2019). The acceptance of halal food in non-Muslim countries: Effects of religious identity, national identification, consumer ethnocentrism and consumer cosmopolitanism. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 10(4), 308–1331. https://doi.org/10.1108/JIMA-11-2017-0132

- Worthington, E. L., Wade, N. G., Hight, T. L., Ripley, J. S., McCullough, M. E., Berry, J. W., Schmitt, M. M., Bursley, K. H., & O'Connor, L. (2003). The religious commitment inventory–10: Development, refinement, and validation of a brief scale for research and counseling. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 50(1), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.50.1.84

- Yetkin Özbük, R. M., Coşkun, A., & Filimonau, V. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on food management in households of an emerging economy. In Socio-Economic Planning Sciences (in press). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2021.101094