?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The study examines seven key dimensions of online customer engagement behaviour and uses these to build ideal and baseline profiles. This ensures verbal and statistical correspondence. This approach allows identification of critical customer engagement behaviour to invest in and which one to invest in for maintenance. The study finds that deviating from the critical behaviours has negative implications for the spreading of positive word of mouth and brand loyalty. The findings and the methodological procedures are of interest to hospitality managers and academics. Data for the study was obtained from 326 customers at various hotels in Mauritius. The configural conceptual framework was tested using profile deviation to assure verbal and statistical correspondence leading to clear actionable recommendations for managers. The analysis goes beyond the approach in extant research by examining both the global and disaggregated impacts on PWOM and brand loyalty. The theoretical and managerial implications of the study are further discussed.

摘要

鉴于当今消费者在网上影响同行的机会前所未有,企业必须通过识别最有可能表现出预期结果的消费者来最大限度地提高在线关系营销的有效性. 因此,本研究考察了七种在线行为概况及其与两个关键变量的相互关系:积极的口碑(PWOM)和品牌忠诚度. 它构建了一个理想的消费者档案,并使用档案偏差分析来评估不遵守该基准的影响. 鉴于在线反馈在服务业的强大影响力,以及旅游业和酒店业的高度竞争性,我们利用从毛里求斯326名酒店客人那里收集的数据,对酒店业进行了研究. 我们的研究结果表明,在入住期间使用社交媒体、参与评论分享网站TripAdvisor、使用社交媒体娱乐和生成内容的消费者最有可能传播PWOM或表现出品牌忠诚度,而偏离理想的个人资料对这两个变量都有负面影响. 因此,该分析通过指出行为档案对PWOM和品牌忠诚度的全球和分类影响来扩展知识,为管理者提供清晰、可行的建议,并对理论做出有用贡献.

Introduction

The huge growth in the popularity of social media and other online platforms has revolutionized consumer-brand relationships, enabling not just new marketing avenues for businesses but unparalleled opportunities for consumers to influence their peers. This new online landscape of user-generated content, peer endorsement, and feedback has dramatically changed the way consumers make purchases (Chanchaichujit et al., Citation2018; Ebrahimi et al., Citation2023; Kitsios et al., Citation2022). The service sector offers a prime example of a context in which consumers’ reliance on online reviews, real-time feedback and multi-media content has expanded rapidly, highlighting the need for hospitality and tourism enterprises to harness beneficial online behaviors to maximum effect (Pan et al., Citation2022).

Prior studies have often defined social customer relationship management (SCRM) as a process whereby social media platforms are used to deliver customer relationship management strategy (Aldaihani & Ali, Citation2018; Dewnarain et al., Citation2021). However, given the advent of Web 2.0, with its interactivity, user-generated content, expanding social media versatility, and dedicated review sites, it is no longer helpful to view SCRM through such a narrow prism. For example, service users can not only access marketing information such as 360-degree views of their hotel room, but can post real-time content describing their actual experiences, including on hugely influential review-sharing sites such as TripAdvisor.

Given the power and permanence of this online consumer influence, it is essential for brands to move beyond targeting internet users as a single, amorphous entity, recognizing instead that consumers with differing online behavioral profiles may respond to brands in varying ways. Understanding the evolving nature of digital consumers is also crucial for managers wishing to tackle uncertainties in their environment head-on (S. Dewnarain, Ramkissoon, & Mavondo, Citation2019; Dewnarain et al., Citation2021; Ramkissoon, Citation2021a, Citation2022, Citation2023a; Ramkissoon & Mavondo, Citation2023). Prior studies have already offered useful classifications of social media users (e.g., Kozinets, Citation1999, Citation2002) and identified key types of online behaviors (e.g., Frost et al., Citation2019; Mkono & Tribe, Citation2017; Riskos et al., Citation2021; Strauss & Frost, Citation2014).

However, little attention has been paid to understanding which online behavioral profiles are most strongly associated with achieving the desired outcomes of relationship marketing. Creevey et al. (Citation2019) highlight the need for further research on customer engagement behaviors on social media platforms pre-, during and post-purchase, so companies can reap augmented benefits in the form of word of mouth and loyalty. Vivek et al. (Citation2012)findings on the outcomes of customer engagement are not generalizable as the study used a qualitative approach and a small sample. Moreover, in the service sector context, the literature offers little research on the ideal hotel guest profile based on online consumer engagement behavior (Chathoth et al., Citation2016; Shoukat & Ramkissoon, Citation2022), while existing hospitality studies on the impact of social media typically focus on the pre-trip stage and online responses on hotel pages (Sánchez-Casado et al., Citation2019). Research exploring customers’ online engagement behavior with hotels’ brand content during the purchase stage is also still in its infancy (Creevey et al., Citation2019; De Vries & Carlson, Citation2014; Kitsios et al., Citation2022). Having a holistic view of the whole consumption process is essential to allow efficient profiling and to create customer delight. On the other hand, a fragmented view can only prove detrimental to marketing initiatives (Bai, Citation2022).

Given these gaps in knowledge, this research develops and tests a model that explores the interrelationships between specific online behavioral profiles and two key variables, positive word of mouth (PWOM) and brand loyalty, providing unique insights into which consumer types are likely to be the most beneficial focus of SCRM. Our study breaks significant new theoretical ground by integrating fit/configuration theory with a profile deviation analysis. Moreover, reflecting the realities of the digital age, it moves away from the traditional focus on organizations as units of analysis, concentrating instead on the behavioral profiles of individuals (Hollebeek, Citation2011; Hollebeek et al., Citation2019; Sarkar et al., Citation2022), thereby offering a fresh approach to studying SCRM by exploring the customers’ role in achieving the desired relationship outcomes. Finally, we believe our study is the first of its kind in this context to cover the entire purchase cycle, analyzing online behaviors pre-, during, and post-trip.

The study addresses four questions: (a) what is the profile of customers who will pass on PWOM?; (b) what is the profile of customers who will become loyal to the brand?; (c) what, if any, is the impact of deviating from these ideal profiles?; and (d) which online behaviors are most critical to minimizing deviation from these ideal profiles? To answer these questions, we first sought to identify an ideal customer profile by exploring a series of seven online consumer engagement behaviors and their interrelationship with the two selected variables, PWOM and brand loyalty. We then conducted a profile deviation analysis to explore the impact of non-adherence to this benchmark, by measuring the fit between the seven behavioral profiles and the enhancement of PWOM and brand loyalty. Given the particular significance of online feedback in the service sector, and the highly competitive nature of tourism and hospitality, the study was conducted in the context of the hospitality industry, specifically the hotel sector in Mauritius. In addition to its theoretical contributions, our detailed exploration has enabled identification of the most efficacious targeting of resources and the best communication channels through which marketing managers can reach their target markets, offering a route to maximizing marketing effectiveness and thus ultimately to profitability.

Literature review

Social media and social customers

Companies’ increasing use of social media to engage with customers requires them to constantly review their profile mix and maintain their relevance (Gu et al., Citation2022). The importance of this shift has been heightened by the identification of the social customer (also referred to as a social capital seeker), a person who blends the characteristics of a traditional and a cyber customer, since they use online and offline channels interchangeably to purchase products and services (Aydin, Citation2020). In hospitality, social customers prefer to consult trusted peers on social media channels, rather than travel agencies, when going through the decision-making process and purchase journey (Santini et al., Citation2020). These travelers want to be perceived as having similar experiences to those of other people in their networks, since experience increasingly represents an important economic offering, adding value to the product and service (Li et al., Citation2021; Sánchez-Casado et al., Citation2019; Zhong et al., Citation2017). Online interactions thus play an important role in shaping the perceptions of hospitality consumers when it comes to finalizing purchases, since social media users, like customers in general, are willing to try new experiences that may boost their social capital (Gu et al., Citation2022; Majeed & Ramkissoon, Citation2022; Nekmahmud et al., Citation2022). However, little attention has been paid to understanding which key customer engagement behaviors lead to repeat purchase or brand advocacy in the hospitality industry (Wong, Citation2023). This topic warrants further investigation, especially since studies in related fields have found a marked attitude-behavior gap among social customers (Bozkurt et al., Citation2020) and hotel customers (Creevey et al., Citation2019) when it comes to converting positive attitudes into purchases, which in turn hinders profitability (Li et al., Citation2021; Santini et al., Citation2020). Even well-formulated digital marketing plans may not guarantee customer conversion, which is necessary to sustain business growth (Makhafola & Anning-Dorson, Citation2022), highlighting the importance of understanding the interrelationships between online behavioral profiles and outcomes.

Configuration theory and fit theory

Over the past 20 years, configuration theory has been employed by management to gauge complex “multidimensional phenomena implied in fit or congruence relations in ways that are more consistent with the holistic framing of strategic management and marketing strategy than traditional approaches like interactions or contingency theory” (Malhotra et al., Citation2013, p. 1339). These conventional approaches often lead to inconsistency in research findings, as they fail to establish a strong link between theory building and theory testing. Business scholars have traditionally used a number of seemingly interchangeable terms such as “match,” “congruence,” “alignment” and “fit” to study these multidimensional phenomena (Drazin & Van de Ven, Citation1985). As noted by Venkatraman (Citation1989, Citation2007), researchers perceive the configuration model as an interaction, selection or systems approach to fit, but rarely operationalize it as such. Applying configuration fit to customers in a hotel context leads to a holistic or ideal hotel guest profile, which may lead to superior decisions in customer targeting. This systems approach views fit as the multidimensional consistency of a consumer relative to an ideal or benchmark consumer. Fit measurement thus implies assessing the deviations of a real customer from one or more types of ideal customers, with the ideal types represented by multivariate profiles that provide the correspondence between the verbal descriptions of the ideal types and the measures used to assess real organizations (Doty et al., Citation1993).

Some earlier research (e.g., Doty et al., Citation1993; Venkatraman & Prescott, Citation1990) suggests that fit should be conceptualized and assessed in terms of profile deviation. Vorhies and Morgan (Citation2003, p. 102) define profile deviation as an approach that views “fit between organization and strategy in terms of the degree to which the organizational characteristics of a business differ from those of a specified profile identified as ideal for implementing a particular strategy.”

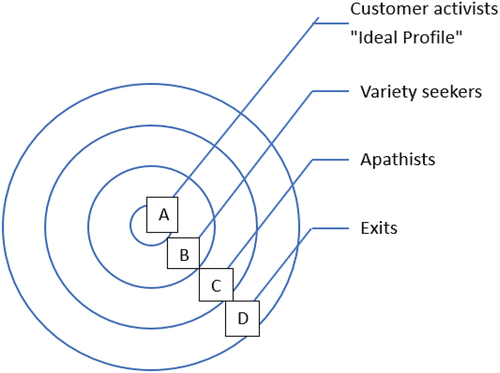

Fit theory states that superior effectiveness arises from matching or aligning several characteristics to give the best configuration. In organizational research, this implies aligning strategy, structure, and organizational processes (So et al., Citation2021; Venkatraman & Prescott, Citation1990). The theory predicts that the closer an organization is to attracting the ideal type of customer, the more effective it will be. As illustrated in , the most valued customers, i.e., those with the ideal profile, are those who will spread PWOM and will remain loyal to the brand. Next are the variety seekers, who are less likely than the first group to spread PWOM and more likely to try other brands, so their brand loyalty is lower. The third group comprises consumers who are apathetic, with a consequent drop in PWOM and brand loyalty. Finally, the group of customers least likely to spread PWOM, least likely to be loyal, and most likely to exit the brand altogether, deviate most significantly from the ideal profile. It should be noted that the ideal profile is a specific empirically developed profile that represents the best customer.

Fit theory has been used in recruitment by profiling the most effective employees and comparing applicants with them: those with the smallest deviation from the ideal are selected since their effectiveness is expected to be highest. In situations where the ideal profile is not theoretically available, this can be empirically derived by looking at the profile of the most effective organizations or individuals, and then benchmarking the rest against these (Venkatraman & Prescott, Citation1990; Vorhies & Morgan, Citation2005).

Positive word of mouth and its online manifestations

Grewal et al. (Citation2003, p. 187) defined word of mouth (WOM) as the “act of exchanging marketing information among consumers through face-to-face communication”. However, as the digital revolution took hold, face-to-face contact was no longer critical, and the concept of electronic word of mouth (eWOM) emerged. As noted by Dwyer (Citation2007), eWOM is not limited to social media channels, but extends to a range of tools that facilitate online communication and allow customers to have access to unbiased product reviews. Unlike traditional WOM, eWOM thus catalyzes the sharing of experiences not just with close friends but with remote contacts via the internet. It is now recognized as a vital source of information that impacts consumers’ product and brand choices by influencing the purchase decision-making process. Moreover, eWOM contributes to the dimension of trust (Ramkissoon, Citation2021b, Citation2023b), which validates the use of consumption-related advice provided by diverse internet users (Bai, Citation2022). As Weitzl and Einwiller (Citation2018) argue, service providers and practitioners cannot afford to discount the mounting importance of eWOM based on social networking interactions. However, Shoukat and Ramkissoon (Citation2022) highlight that the extant literature focuses mainly on the outcomes of eWOM in the form of sales, with a dearth of information on the factors that influence consumer WOM behavior in a computer-mediated environment strongly dominated by social networking sites.

Many studies posit that customer engagement acts as a key driver for PWOM and relationship building (e.g., S. Dewnarain, Ramkissoon, & Mavondo, Citation2019; Vivek et al., Citation2012; Weitzl & Einwiller, Citation2018). This is further sustained by the fact that customer engagement promotes non-transactional behaviors such as co-creation, which is a key social relationship benefit essential for customer retention. Customer brand loyalty is often reflected in the way customers share their opinions and feelings about the brand (Bozkurt et al., Citation2020; Rosenbaum & Massiah, Citation2007). A customer who is empowered and has a strong voice online, usually conveyed in the form of reviews, is also someone who will exhibit a high level of brand loyalty. Companies that nurture social interactions online tend to develop stronger social relationships that fuel eWOM. Customer online behavior in the form of eWOM is considered as a voluntary act (Gu et al., Citation2022). A customer’s attitudinal behavior (positive or negative) toward a brand determines whether the customer will end his/her relationship with the brand or will develop a higher level of commitment to the brand and hence, act as influencers (see Hirschman’s (Citation1970) model of voice, exit and loyalty). However, despite the wealth of knowledge regarding customer engagement and its consequences, few researchers have engaged with the question of which specific types of underlying behaviors are linked to positive outcomes.

Brand loyalty

Jacoby et al. (Citation1978, p. 80) described brand loyalty as “the biased behavioral response expressed over time by some decision-making unit, with respect to one or more alternative brands out of set of such brands, as a function of evaluative psychological processes.” This definition highlights both the behavioral and cognitive components of loyalty. Previous studies conducted on brand loyalty indicate that customer engagement shares a positive linear relationship with customer loyalty (Patterson et al., Citation2006; Zhong et al., Citation2017). This notion is further supported in service-based firms such as the hospitality sector by the fact that appropriate levels of customer-perceived activity and a lowered level of customer boredom in service delivery results in customer satisfaction which favorably influence loyalty ratings. In contrast, So et al. (Citation2021) argue that different customer segments exhibit different levels of brand engagement. For instance, although a person enjoys watching television, this activity results in fatigue after a certain time, and leads to disengagement.

According to Vivek et al. (Citation2012), customer engagement differs from brand loyalty in the sense that it does not involve making comparative evaluation of brands nor does it entail any form of behavioral decision-making pertaining to repeat purchase. However, the crux of the matter here is that an engaged individual establishes a connection with the brand which evolves with time and reinforces the psychological processes and consequently augments the likelihood of developing brand loyalty. This aligns with the concept of hierarchy of effects by Oliver (Citation1999). As per this concept, customers initially process information to form beliefs, and those beliefs are then employed to form attitudes which consolidate behavioral decisions. “An engaged consumer is likely to transition faster on the belief-attitude-behavior continuum” (Vivek et al., Citation2012, p. 136). Thus, while customer engagement plays an important role in strengthening brand loyalty, businesses need to avoid investing resources in activities that lead to customer tedium, focusing instead on nurturing the attitudes of key customer segments based on their online behaviors, and this topic lacks specific exploration (Kandampully et al., Citation2018).

Key online behavioral profiles

Prior studies have proposed a number of online behavioral classifications based on users’ conduct and motivations (Cannon & Rucker, Citation2022; Goldsmith et al., Citation2022). Seven profile types – content generators, social connectors, egocentrics, information seekers, bored users, relaxation/entertainment seekers and new product/update seekers – were selected for inclusion in our study, since they can be argued to have particular significance in understanding which groups of online consumers are most or least likely to constitute ideal or sub-optimal guest profiles (Bai, Citation2022; Kandampully et al., Citation2018). They are explored in more depth in the following sections.

Content generators

Social networking sites depend on content creation (Strauss & Frost, Citation2014; Sung et al., Citation2023). The creation of new content keeps users’ profiles active and is also considered the highest form of user engagement. Kozinets (Citation1999, Citation2002) places online content generators into four groups, depending on their consumption interests and level of involvement with online communities: tourists, who generally pose casual questions and do not forge strong social ties with the community; minglers, who nurture strong social ties but display minimal consumption interests; devotees, who are strongly interested in consumption but not in connecting to community groups; and insiders, who are engaged in both consumption activities and the fostering of strong relationships with other users. Khataei et al. (Citation2021), in their exploration of how the generation of persuasive contents can influence other users’ attitude and behaviors, highlight the need to understand how user-generated content impacts the user’s profile, and how social media feedback on a brand can persuade other customers to make purchases.

Social connectors

Connecting to other users is a fundamental part of maintaining an online presence (Bozkurt et al., Citation2020). As well as nurturing relationships with people in their existing circle, social connectors constantly expand their network – and thus its social capital value – by making new connections. In the digital age, consumers have numerous inexpensive and convenient ways to interact with each other, such as e-mails, text messages, and Facebook posts (Strauss & Frost, Citation2014), enabling new connections with people and businesses that can be carried offline into the physical world. Today, there is a seamless integration between online and offline channels. For example, social media platforms may act as an initial contact point, before the interaction moves to a conversation on WhatsApp, and finally to an actual purchase. Post consumption, many consumers also use social media platforms to provide feedback. While some people connect with companies because they are genuinely interested in the brand, others may connect for product reviews and rankings, or simply to obtain information about discounts and exclusive offers (Bai, Citation2022; Frost et al., Citation2019).

Egocentrics

Egocentrics, also known as status-seekers, are driven by the need to become influencers. Given this motivation, it is crucial to understand the composition of their networks (e.g., whether they predominantly comprise family members or friends), and whether they can actually persuade others and themselves to be loyal to a specific brand, or instead display brand-switching behaviors. Building on Kozinets (Citation1999, Citation2002) classifications of content generators as tourists, minglers, devotees, and insiders, it is critical to establish whether egocentrics can successfully take on the role of insiders and help companies optimize behavioral outcomes in the form of PWOM and brand loyalty (Dewnarain et al., Citation2021), given their strong desire to influence other internet users.

Information seekers

In the social media context, it is important to understand the fine line between information seekers and the information being sought (Frost et al., Citation2019). The inability to understand this nuance can impact on relationship outcomes, since the online social system comes with inherent risks. In their study on the use of TripAdvisor, Mkono and Tribe (Citation2017) described information seekers as people interested in learning through information exchange, and explored why tourists or online users used third party channels to ask questions of others, rather than asking the brands directly: they concluded that one main reason was the credibility of WOM provided by ordinary users who, unlike employees, were not motivated by commercial or financial incentives.

Bored users

A divergence of attention often leads to a state of boredom (Ghosh et al., Citation2018; Khan, Citation2017; So et al., Citation2021). While it can be noted that some people go to social media sites when they are bored, these customers are more likely to be recovered or won over by a friend who shares relevant messages, rather than by a company using push strategy and channeling adverts to the bored customer. Bored customers’ online interactions can impact adversely on brand value (Riskos et al., Citation2021). Hence, it is significant to study whether bored users can be shifted from a dormant state to being brand advocates.

Relaxation/entertainment seekers

The majority of people who browse the internet and use social media sites do so for relaxation and entertainment purposes (Frost et al., Citation2019; Strauss & Frost, Citation2014), a trend likely to continue as internet-based film and television services, including catch-up viewing, expand. The online film-streaming firm Netflix relies heavily on the recommendation model, based on suggested content that has been viewed by others, and on the availability of online reviews. Hence, if numerous customers go online to watch videos and for entertainment purposes (Riskos et al., Citation2021), content relevance coupled with genuine reviews from other peers can have a significant impact on brand loyalty. In the absence of these options, users may simply ditch the brand. Studying the relationship between entertainment and behavioral outcomes is therefore important.

New product/update seekers

Customers seeking product information may wish to know about both updates and new offerings. According to Davis (Citation1989), information usefulness refers to the extent to which information helps consumers in finalizing purchase decision. The usefulness of content tends to determine consumer purchase and loyalty behaviors. Bobkowski’s (Citation2015) study, underpinned by information utility theory, further underscored that perceived information usefulness may directly affect information-sharing intentions in the form of positive eWOM. Irrespective of whether a company is endeavoring to boost sales by sharing information on new products, or trying to reconvert dormant customers into active ones by providing fresh contents that act as reminders, an understanding of customer profiling in this context is key to developing brand value in the long run (Keller & Swaminathan, Citation2020).

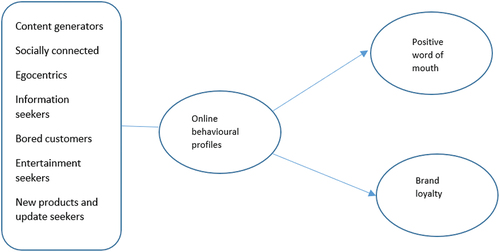

Hypothesis development

Irrespective of the initial reason for the connection with the brand, it is of the utmost importance for a company to understand what relationship outcomes it can expect from various customer segments (Bai, Citation2022; Kandampully et al., Citation2018). Previous studies have advocated the need for strategic marketers to understand the new consumer profiles that have emerged in the internet age, since failure to understand the constantly evolving behaviors of social customers may altogether result in “exit””, with high levels of brand switching (Chu & Kim, Citation2011; Hong et al., Citation2023). Despite the high level of interactions that take place on social networking sites, and the number of eWOM formats that have emerged (Kitsios et al., Citation2022; Makhafola & Anning-Dorson, Citation2022), little attention has been paid to establishing ideal online customer profiles that act as precursors to developing desired behaviors such as PWOM and brand loyalty. This study therefore seeks to identify the ideal or benchmark consumer profile based on online behaviors. Based on the literature review and the gaps in knowledge we identified, we developed our proposed conceptual model (shown in ), along with four hypotheses, to test the interrelationships between consumers’ online behavioral profiles, their engagement in PWOM, and their likelihood to exhibit brand loyalty. These hypotheses are as follows:

H1:

Deviation from the ideal profile in the seven selected online behaviors has a negative effect on positive word of mouth.

H2:

Deviation from the ideal profile in the seven selected online behaviors has a negative effect on brand loyalty.

H3:

Total deviation from the ideal profile of baseline consumers has a negative effect on positive word of mouth.

H4:

Total deviation from the ideal profile of baseline consumers has a negative effect on brand loyalty.

Methodology

Data collection

This study adopted a quantitative approach. A questionnaire survey method was used to identify social media engagement behaviors that are conducive to developing a positive word of mouth and brand loyalty. The study was conducted in the hospitality industry, since this is a competitive, volatile and complex sector in which customers are prone to switching brands in search of new experiences, and in which consumers can strongly influence their peers through their online activity. We adopted Khan (Citation2017) scale to measure the online consumer behaviors of tourists in our study. Khan (Citation2017) study investigated consumption process in the service sector but focused on only YouTube.

An a-priori sample size calculator was used to calculate the sample size (Soper, Citation2018). A total of 382 responses to the survey was generated, of which 326 were retained for further analysis following data cleansing. The results of the sample size calculation suggested a minimum sample size of 226 was required for the model structure and these 326 responses were therefore considered to be a representative sample of the population given that there are roughly 1 million tourists who travel to Mauritius every year (MTPA, Citation2022).

Data collection took place on the island of Mauritius, a developing state located approximately 1,200 km off the south-eastern coast of the African mainland, to the east of Madagascar. Alongside its image as a traditional resort destination, Mauritius is also a renowned destination for its natural and cultural assets (Nunkoo & Ramkissoon, Citation2016; Ramkissoon, Citation2016). The island is also famous for the film industry: the film Resort to Love was filmed entirely on the island (DefiMedia, Citation2021). The island’s hotels are constantly inspected to ensure quality (MTPA, Citation2019). Hospitality service providers are thus always under pressure to upgrade their facilities and to deliver on various service quality dimensions (e.g., reliability, empathy, tangibility, assurance, and responsiveness) so as to maintain their rating (S. Dewnarain, H. Ramkissoon, & T. F. Mavondo, Citation2019; Zeithaml et al., Citation2018).

Data was collected from a diverse range of customers of 3-, 4- and 5-star hotels, which account for 93% of the island’s 114 hotels (MTPA, Citation2019). The surveys were conducted face-to-face, ensuring deeper insights than other methods. Data collection took place in the departure lounge of the Sir Seewoosagur Ramgoolam International airport. Since most of the island’s tourists are from Europe, the departure time of the main carriers was tracked to boost the efficiency of the data collection process (Dewnarain et al., Citation2021). Participants were first asked to confirm the name of the hotel where they had stayed, to ensure that only customers of 3-, 4 or 5-star hotels took part. It was also important to check if they were social media users, since we were studying how customers had interacted with hotels on social media platforms during the various phases of their purchase process and visit. Hence, a purposive sampling strategy was used to ensure that meaningful data was collected (Zickar & Keith, Citation2023).

Development of calibration and baseline samples

We tested the conceptual framework using profile deviation analysis (Doty et al., Citation1993). This required three essential steps (Venkatraman & Prescott, Citation1990): (i) identifying which customers were the best performers for PWOM or loyalty; (ii) describing their profile using the critical dimensions (seven variables); and (iii) testing the performance implications of deviations from the ideal profile. In this context, specifying the ideal (i.e., benchmark) profile is of major importance. This “calibration sample” of best-performing entities (Venkatraman & Prescott, Citation1990, p. 6) comprised the 5% of the sample with the highest scores on PWOM or brand loyalty. These were computed separately for PWOM and brand loyalty. The baseline samples were then developed by removing 5% of the respondents with the lowest scores on PWOM or brand loyalty. Tour samples – two calibration and two baseline – were thus obtained. The removal of the 3% lowest performers was undertaken to minimize the biasing effect of removing the top 5% (Venkatraman & Prescott, Citation1990). The calibration samples were used as the benchmark against which the baseline sample was compared.

Computing profile deviation

Using the 326 valid questionnaires obtained during the survey, we calculated both aggregate and disaggregated profile deviation variables based on the seven online behavioral profiles under exploration. Total profile deviation is the aggregated misalignment score of a respondent in online engagement behavior relative to the “calibration” or ideal sample mean. The misalignment variable was calculated as follows:

where xij corresponds to the score for respondent i in the respective baseline sample along the jth behavior; ideal is the mean for the ideal profile on the jth engagement behavior, and seven is the number of online behaviors in our model. This allowed the calculation of profile deviation scores between the non-ideal and ideal respondent for all seven behaviors.

In addition, the disaggregated profile deviation scores for each of the seven behaviors used in the total profile deviation were computed (Anisimova & Mavondo, Citation2010; So et al., Citation2021). The disaggregated profile deviation scores were computed as follows:

where j denotes the jth of the seven-profile deviation of each online behavior. This resulted in seven profile deviation variables based on the respective calibration and study samples used in the research. There is an alternative approach: to compute the profile deviation equivalent to total deviation by using the items of each online behavior.

Results

Analysis and results

Model 1 (as shown in above) was the result of entering the individual profile deviations as antecedents of PWOM. The results suggest that the hypotheses arising from Proposition 1 were largely not supported except for use of social media during the stay at the hospitality outlet (b = −0.237, tvalue = −4.195, p < .001); use of TripAdvisor (b = −0.193, t-value=- 3.304, p < .001, use of social media for entertainment (b = −0.164, tvalue = −3.065; p < .01). In Model 2 total profile deviation was entered alone and the finding support the hypothesis (b = −0.335, tvalue = −6.505, p < .001) (as shown in above).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the study calibration and baseline samples PWOM.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the calibration and baseline samples of brand loyalty.

In Model 3 for brand loyalty (as illustrated in above), we entered all seven online engagement behaviors, the only supported behaviors are use of social media during the visit (b = −0167, tvalue = −2.917, p < .05, and content generation (b = −0.146, tvalue = −2.481, p < .05). Finally, we entered the total deviation and H3 was supported (b = −0.143, tvalue = −2.644, p < .01).

Table 3. Regression table.

Discussion

The regression models for PWOM indicate that the variance explained by the deviation of the online behaviors is meaningful (17.7%), and by the total deviation (11.2%). On the other hand, the variances explained for brand loyalty are rather small (5.3% and 2%, respectively). There are several possible explanations for this. In a tourist destination, the chances of developing brand loyalty are low, given the variety-seeking behavior of customers. On the other hand, if the experience has been very satisfying, spreading PWOM is very likely. In addition, even a brand loyal customer may not return to the same hospitality outlet because it may not be close to the primary purpose of the visit, and because this may also depend on who is traveling with them. In addition, spreading PWOM may also serve another purpose, such as an individual wishing to demonstrate to friends and family that they had made a good decision in their choice of destination (Makhafola & Anning-Dorson, Citation2022).

From a resource deployment perspective, the findings suggest that incentivizing travelers who engage in social media during their stay, those who use TripAdvisor and those who use social media as entertainment, is a good investment. However, there may be interactions with other online behaviors that were not examined in this study.

Our findings align with those of Bozkurt et al. (Citation2020), who underscored that customers are more likely to recommend brands that display high level interactivity on social media sites. In exchange of monetary or non-monetary rewards, there is a propensity for customers to influence people in their social networks about the brand. However, to create more brand value for companies that promote high customer engagement, brand advocates willingly provide referrals (Goldsmith et al., Citation2022), as well as reviews that help firms improve their overall brand performance. When it comes to the hospitality industry – where brand switching behavior tends to be higher since customers are seeking new experiences most of the time – insights from actual travelers easily overweigh direct marketing messages from the brand.

Theoretical and managerial implications

This paper makes a number of useful contributions to both theory and practice.

Theoretical implications

Firstly, in terms of theoretical contributions, our study enriches the hospitality marketing and management literature by developing and testing a model that explores the interrelationship between seven selected online behavioral profiles, PWOM, and brand loyalty. The research is underpinned by configuration theory, which has rarely been studied in tourism marketing (e.g., Anisimova & Mavondo, Citation2010; Malhotra et al., Citation2013). In addition, by integrating this theory with profile deviation analysis, we provide new theoretical insights into the drivers of PWOM and brand loyalty, by studying the seven key consumer online behaviors and their relationships with these constructs. This paper is thus one of the few marketing studies to have employed fit theory along with a profile deviation approach, to illuminate how the individual online behavior of social capital seekers can be harnessed to amplify PWOM and brand loyalty. While fit/configuration theory is often used in recruiting employees in order to find the right fit for an organization, this paper demonstrates that it has additional relevance in fostering relationships with specific types of customer profiles (Santos et al., Citation2021). Similarly to recruitment, online engagement with customers is a costly process (Aydin, Citation2020). Relying on customer insights about amenities and overall experience post check-out will help neither in driving digitally savvy customers to hotels, nor in generating opportunities for existing clients to spend more on experiences while they are at the hotel (Santos et al., Citation2021). Hence, this paper breaks significant new ground by integrating fit/configuration theory and by using a profile deviation approach to address such issues.

Moreover, while the marketing communications literature has generally concentrated on studying organizations as business units, this investigation centers on specific individual behavioral profiles (Hollebeek, Citation2011; Hollebeek et al., Citation2019; Khan, Citation2017). This shift away from focusing on organizations as units of analysis represents an important move forward, as the traditional approach is too restrictive in the digital era (Kabadayi et al., Citation2007; Vorhies & Morgan, Citation2003).

In addition, by covering the whole customer purchase cycle, i.e., by analyzing customers’ online engagement behaviors before, during, and after their trips, our paper provides a holistic view which we believe to be the first of its kind in this context. Finally, by illuminating which consumer profiles are more or less likely to result in desired behaviors, we believe our findings also contribute to consumer behavior theory, by offering insights into how to the attitude-behavior gap might be decreased by enabling better targeting of resources.

Managerial implications

In terms of managerial contributions, by offering insights into which types of online consumer behaviors predict PWOM and brand loyalty. Our findings allow managers to reach out to more profitable customer segments and allocate resources effectively. For example, they will be able to focus on more profitable target markets, reducing costs, and enhancing revenue by targeting those consumers who behavioral profiles suggest that they are the most likely to promote PWOM and enhance customer loyalty.

Practitioners should also be able to use the insights offered by this paper to incentivize ideal customers, such as those who are avid users of social media during their stay, those who engage with TripAdvisor, those who use social media as a form of entertainment, and those who generate new online content. For example, travelers fitting this profile could be incentivized by providing a free breakfast, sauna, or any other cost-effective means. The identification of such customers could be achieved by asking simple questions upon arrival, such as “to what extent will you use social media during your stay;” “to what extent do you use TripAdvisor when planning trips,” and “to what extent do you use social media as a form of entertainment,” which come directly from this study. Using the findings of this study, hospitality marketers will therefore be able to influence the buying and consumption behaviors of customers in real time. This is significant, since each critical incident or moment of truth offers hospitality employees an opportunity to outperform competitors and creates more delighted customers by designing more personalized customer experiences which enhance PWOM and brand loyalty.

Our study also proposes a series of microsegments based on online consumer engagement behaviors, which should be beneficial in curbing the marketing myopia that normally results when organizations fail to understand evolving customer needs and expectations. Finally, by examining seven key types of customer online engagement behaviors, our findings guide marketing managers on the best communication channels to reach their target markets.

Conclusions

This study, conducted in the hotel sector in Mauritius, has blended configuration theory and profile deviation analysis to explore which of seven selected online behavioral profiles are most likely to have beneficial effects on PWOM and brand loyalty. Our findings identify an ideal guest profile and suggest that deviations from this profile will have a negative impact on the two constructs. For example, our study suggests that hospitality consumers who use social media during their stay, engage with the review-sharing site TripAdvisor, use social media as a form of entertainment, and generate new content are most likely to spread PWOM or exhibit brand loyalty.

Our findings make significant theoretical contributions by integrating fit/configuration theory with profile deviation analysis to test the interrelationships between online profiles, PWOM and brand loyalty during the entire purchase cycle. We also focus primarily on customers rather than organizations as a means of studying SCRM outcomes. Our findings underscore the burgeoning importance of recognizing specific types of online customer engagement behaviors and their relationship with desired outcomes. They encourage marketing managers to move away from a model which treats all online consumer profiles as broadly equal. Our recommendations thus enable industry practitioners to boost their position in the highly competitive hospitality market.

Our study has certain limitations. For example, it examines only how effective engagement with ideal customer profiles can create value for service-based firms in the form of PWOM and brand loyalty. Future research could also explore how engagement between ideal customer profiles and employees could lead to service innovations (Li et al., Citation2021) or other desired outcomes. Finally, other types of online behavioral profiles could be considered, to test their impact on the ideal guest profile and the effects of deviating from it.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aldaihani, F. M. F., & Ali, N. A. B. (2018). Impact of social customer relationship management on customer satisfaction through customer empowerment: A study of Islamic banks in Kuwait. International Research Journal of Finance & Economics, 170, 41–53.

- Anisimova, T., & Mavondo, F. T. (2010). The performance implications of company‐salesperson corporate brand misalignment. European Journal of Marketing, 44(6), 771–795. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090561011032711

- Aydin, G. (2020). Social media engagement and organic post effectiveness: A roadmap for increasing the effectiveness of social media use in hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1588824

- Bai, L. (2022). Analysis of the change of artificial intelligence to online consumption patterns and consumption concepts. Soft Computing, 1–11.

- Bobkowski, P. S. (2015). Sharing the news: Effects of informational utility and opinion leadership on online news sharing. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 92(2), 320–345. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699015573194

- Bozkurt, S., Gligor, D. M., & Babin, B. J. (2020). The role of perceived firm social media interactivity in facilitating customer engagement behaviors. European Journal of Marketing, 55(4), 995–1022. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-07-2019-0613

- Cannon, C., & Rucker, D. D. (2022). Motives underlying human agency: How self-efficacy versus self-enhancement affect consumer behavior. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 101335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101335

- Chanchaichujit, K., Holmes, K., Dickinson, S., & Ramkissoon, H. (2018, June). An investigation of how user generated content influences place affect towards an unvisited destination. In 8th Advances in Hospitality and Tourism Marketing and Management Conference, Bangkok, Thailand (pp. 25–29).

- Chathoth, P. K., Ungson, G. R., Harrington, R. J., & Chan, E. S. (2016). Co-creation and higher order customer engagement in hospitality and tourism services: A critical review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(2), 222–245. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2014-0526

- Chu, S. C., & Kim, Y. (2011). Determinants of consumer engagement in electronic word-of-mouth (eWOM) in social networking sites. International Journal of Advertising, 30(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-30-1-047-075

- Creevey, D., Kidney, E., & Mehta, G. (2019). From dreaming to believing: A review of consumer engagement behaviours with brands’ social media content across the holiday travel process. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 36(6), 679–691.

- Davis, F. D. (1989). Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of IT. MIS Quarterly, 13(3), 319–342. https://doi.org/10.2307/249008

- DefiMedia. (2021). Resort to Love : tourné entièrement à Maurice, le film sera sur Netflix en juillet (Authors’ translation: Resort to Love: Filmed entirely in Mauritius, the film will be available on Netflix in July). https://defimedia.info/resort-love-tourne-entierement-maurice-le-film-sera-sur-netflix-en-juillet.

- De Vries, N. J., & Carlson, J. (2014). Examining the drivers and brand performance implications of customer engagement with brands in the social media environment. Journal of Brand Management, 21(6), 495–515. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2014.18

- Dewnarain, S., Ramkissoon, H., & Mavondo, F. (2019). Social customer relationship management: An integrated conceptual framework. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(2), 172–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2018.1516588

- Dewnarain, S., Ramkissoon, H., & Mavondo, F. (2021). Social customer relationship management: A customer perspective. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 30(6), 673–698. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2021.1884162

- Dewnarain, S., Ramkissoon, H., & Mavondo, T. F. (2019). Social customer relationship management in the hospitality industry. Journal of Hospitality, 1(1), 1–14.

- Doty, D. H., Glick, W. H., & Huber, G. P. (1993). Fit, equifinality, and organizational effectiveness: A test of two configurational theories. Academy of Management Journal, 36(6), 1196–1250. https://doi.org/10.2307/256810

- Drazin, R., & Van de Ven, A. H. (1985). Alternative forms of fit in contingency theory. Administrative Science Quarterly, 30(4), 514–539. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392695

- Dwyer, P. (2007). Measuring the value of electronic word of mouth and its impact in consumer communities. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 21(2), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1002/dir.20078

- Ebrahimi, P., Khajeheian, D., Soleimani, M., Gholampour, A., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2023). User engagement in social network platforms: What key strategic factors determine online consumer purchase behaviour? Economic Research-Ekonomska Istraživanja, 36(1), 2656–2687. https://doi.org/10.1080/1331677X.2022.2106264

- Frost, R., Fox, A. K., & Strauss, J. (2019). E-Marketing (8th ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315189017

- Ghosh, S., Bhattacharya, S., Gaurav, K., & Singh, Y. N. (2018). Going viral: The epidemiological strategy of referral marketing. Cornell University.

- Goldsmith, K., Roux, C., Tezer, A., & Cannon, C. (2022). De-stigmatizing the “win–win:” making sustainable consumption sustainable. Current Opinion in Psychology, 46, 101336. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2022.101336

- Grewal, D., Baker, J., Levy, M., & Voss, G. B. (2003). The effects of wait expectations and store atmosphere evaluations on patronage intentions in service-intensive retail stores. Journal of Retailing, 79(4), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2003.09.006

- Gu, Q., Li, M., & Huang, S. S. An exploratory investigation of technology-assisted dining experiences from the consumer perspective. (2022). International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(3), 1010–1029. (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-02-2022-0214

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

- Hollebeek, L. D. (2011). Demystifying customer brand engagement: Exploring the loyalty nexus. Journal of Marketing Management, 27(7–8), 785–807. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2010.500132

- Hollebeek, L. D., Srivastava, R. K., & Chen, T. (2019). SD logic–informed customer engagement: Integrative framework, revised fundamental propositions, and application to CRM. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 47(1), 161–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-016-0494-5

- Hong, V. T. T., Khalifa, G. S. A., Hossain, M. S., Trung, N. V. H., El-Aidie, S. A. M., Hewedi, M. M., & Ali, E. M. (2023). Determinants of customer engagement behaviour in hospitality industry: Evidence from Vietnam. International Journal of Business Environment, 14(1), 94–118. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJBE.2023.127695

- Jacoby, J., Chestnut, R. W., & Fisher, W. A. (1978). A behavioral process approach to information acquisition in nondurable purchasing. Journal of Marketing Research, 15(4), 532–544. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224377801500403

- Kabadayi, S., Eyuboglu, N., & Thomas, G. P. (2007). The performance implications of designing multiple channels to fit with strategy and environment. Journal of Marketing, 71(4), 195–211. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.71.4.195

- Kandampully, J., Zhang, T. C., & Jaakkola, E. (2018). Customer experience management in hospitality: A literature synthesis, new understanding and research agenda. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(1), 21–56. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-10-2015-0549

- Keller, K. L., & Swaminathan, V. (2020). Strategic brand management: Building, measuring and managing brand equity (5th ed.). Pearson Global.

- Khan, M. L. (2017). Social media engagement: What motivates user participation and consumption on YouTube? Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 236–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.024

- Khataei, S., Hine, M. J., & Ali, A. (2021). The design, development and validation of a persuasive content generator. Journal of International Technology and Information Management, 29(3), 46–80. https://doi.org/10.58729/1941-6679.1460

- Kitsios, F., Mitsopoulou, E., Moustaka, E., & Kamariotou, M. (2022). User-generated content behavior and digital tourism services: A SEM-neural network model for information trust in social networking sites. International Journal of Information Management Data Insights, 2(1), 100056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jjimei.2021.100056

- Kozinets, R. V. (1999). E-tribalized marketing? The strategic implications of virtual communities of consumption. European Management Journal, 17(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-2373(99)00004-3

- Kozinets, R. V. (2002). The field behind the screen: Using netnography for marketing research in online communities. Journal of Marketing Research, 39(1), 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.39.1.61.18935

- Li, B., Zhong, Y., Zhang, T., & Hua, N. (2021). Transcending the COVID-19 crisis: Business resilience and innovation of the restaurant industry in China. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 49, 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2021.08.024

- Majeed, S., & Ramkissoon, H. (2022). Social media and tourist behaviors: Post-COVID-19. In Dogan Gursoy & Rahul Pratap Singh handbook on tourism and social media (pp. 125–138). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800371415.00016

- Makhafola, K., & Anning-Dorson, T. (2022). Ithemba lila nyuka (hope is rising): Responding to customer emotions during uncertainties. In T. Anning-Dorson, R. E. Hinson, S. Coffie, G. Bosah, & I. K. Abdul-Hamid (Eds.), Marketing communications in emerging economies, Volume II (pp. 125–140). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Malhotra, A., Malhotra, C. K., & See, A. (2013). How to create brand engagement on Facebook. MIT Sloan Management Review, 54(2), 18–20.

- Mkono, M., & Tribe, J. (2017). Beyond reviewing: Uncovering the multiple roles of tourism social media users. Journal of Travel Research, 56(3), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287516636236

- MTPA. (2019). Mauritius Tourism Promotion Authority - Tourism growth accelerating. https://mauritiusdiscoverytours.com/mauritius-tourism-promotion-authority-tourism-growth-accelerating/.

- MTPA. (2022). Number of tourist arrivals to Mauritius from 2013 to 2023. Tourist arrivals Mauritius 2013-2023 | Statista. Statista.

- Nekmahmud, M., Naz, F., Ramkissoon, H., & Fekete-Farkas, M. (2022). Transforming consumers’ intention to purchase green products: Role of social media. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 185, 122067. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.122067

- Nunkoo, R., & Ramkissoon, H. (2016). Stakeholders’ views of enclave tourism: A grounded theory approach. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 40(5), 557–558. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013503997

- Oliver, R. L. (1999). Whence consumer loyalty? Journal of Marketing, 63(4_suppl1), 33–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/00222429990634s105

- Pan, H., Liu, Z., & Ha, H. Y. Perceived price and trustworthiness of online reviews: Different levels of promotion and customer type. (2022). International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 34(10), 3834–3854. (ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-12-2021-1524

- Patterson, N., Price, A. L., & Reich, D. (2006). Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genetics, 2(12), e190. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190

- Ramkissoon, H. (2016). Place satisfaction, place attachment and quality of life: Development of a conceptual framework for island destinations. Sustainable Island Tourism: Competitiveness and Quality of Life, 106–116.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2021a). Place affect interventions during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 726685.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2021b). Social bonding and public trust/distrust in COVID-19 vaccines. Sustainability, 13(18), 10248. https://doi.org/10.3390/su131810248

- Ramkissoon, H. (2022). Prosociality in times of separation and loss. Current Opinion in Psychology, 45, 101290.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2023a). An introductio to the Handbook of Tourism and Behaviour Change. Handbook of Tourism and Behaviour Change. Edward Elgard, Cheltenham.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2023b). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091

- Ramkissoon, H. & Mavondo, F. (Ed.). (2023). An introduction to gender and entrepreneurship in tourism. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgard.

- Riskos, K., Hatzithomas, L., Dekoulou, P., & Tsourvakas, G. (2021). The influence of entertainment, utility and pass time on consumer brand engagement for news media brands: A mediation model. Journal of Media Business Studies, 19(1), 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/16522354.2021.1887439

- Rosenbaum, M. S., & Massiah, C. A. (2007). When customers receive support from other customers: Exploring the influence of intercustomer social support on customer voluntary performance. Journal of Service Research, 9(3), 257–270. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670506295851

- Sánchez-Casado, N., Artal-Tur, A., & Tomaseti-Solano, E. (2019). Social media, customers’ experience, and hotel loyalty programs. Tourism Analysis, 24(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354219X15458295631918

- Santini, F., Ladeira, W. J., Pinto, D. C., Herter, M. M., Sampaio, C. H., & Babin, B. J. (2020). Customer engagement in social media: A framework and meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 48(6), 1211–1228. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-020-00731-5

- Santos, V., Ramos, P., Sousa, B., Almeida, N., & Valeri, M. (2021). Factors influencing touristic consumer behaviour. Journal of Organizational Change Management, 35(3), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOCM-02-2021-0032

- Sarkar, J. G., Sarkar, A., & Sreejesh, S. (2022). Developing responsible consumption behaviours through social media platforms: Sustainable brand practices as message cues. Information Technology & People.

- Shoukat, M. H., & Ramkissoon, H. (2022). Customer delight, engagement, experience, value co-creation, place identity, and revisit intention: A new conceptual framework. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 31(6), 757–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2022.2062692

- Soper, D. (2018), A-priori sample size calculator for structural equation models. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89[Online]

- So, K. K. F., Wei, W., & Martin, D. (2021). Understanding customer engagement and social media activities in tourism: A latent profile analysis and cross-validation. Journal of Business Research, 129, 474–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.05.054

- Strauss, J., & Frost, R. (2014). E-marketing. Routledge.

- Sung, K. S., Tao, C. W., & Slevitch, L. (2023). Do strategy and content matter? restaurant firms’ corporate social responsibility communication on twitter: A social network theory perspective. Tourism and Hospitality Research, 23(2), 200–212. https://doi.org/10.1177/14673584221103177

- Venkatraman, N. (1989). Strategic orientation of business enterprises: The construct, dimensionality, and measurement. Management Science, 35(8), 942–962. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.35.8.942

- Venkatraman, N., & Prescott, J. (1990). Environment-strategy coalignment: An empirical test of its performance implications. Strategic Management Journal, 11(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250110102

- Vivek, S. D., Beatty, S. E., & Morgan, R. M. (2012). Customer engagement: Exploring customer relationships beyond purchase. Journal of Marketing Theory & Practice, 20(2), 122–146. https://doi.org/10.2753/MTP1069-6679200201

- Vorhies, D. W., & Morgan, N. A. (2003). A configuration theory assessment of marketing organization fit with business strategy and its relationship with marketing performance. Journal of Marketing, 67(1), 100–115. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.67.1.100.18588

- Vorhies, D. W., & Morgan, N. A. (2005). Benchmarking marketing capabilities for sustainable competitive advantage. Journal of Marketing, 69(1), 80–94. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.1.80.55505

- Weitzl, W., & Einwiller, S. (2018). Consumer engagement in the digital era: Its nature, drivers, and outcomes. The Handbook of Communication Engagement, 453–473.

- Wong, A. (2023). How social capital builds online brand advocacy in luxury social media brand communities. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 70, 103143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2022.103143

- Zeithaml, V. A., Bitner, M. J., & Gremler, D. D. (2018). Services marketing: Customer focus across the firm (5th ed.). McGraw Hill Education.

- Zhong, Y. Y. S., Busser, J., & Baloglu, S. (2017). A model of memorable tourism experience: The effects on satisfaction, affective commitment, and storytelling. Tourism Analysis, 22(2), 201–217. https://doi.org/10.3727/108354217X14888192562366

- Zickar, M. J., & Keith, M. G. (2023). Innovations in sampling: Improving the appropriateness and quality of samples in organizational research. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 10(1), 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-120920-052946