ABSTRACT

While Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) has a positive influence on transactional outcomes following a service failure in the hospitality industry, little is known about its influence on consumer forgiveness, particularly relating to individual differences in subjective interpretations and perceptions. We investigate how different subjective interpretations (abstract and concrete mind-sets, i.e. construal level) and perceptions (i.e. warmth and competence) shape the effects of CSR on consumer forgiveness. Through three studies involving different service scenarios, we find that CSR effectively induces consumer forgiveness, with a stronger effect observed among those with an abstract mind-set (i.e. high-level construal) due to their warmth judgment. These findings underscore the importance of CSR in influencing consumer forgiveness and mitigating the negative outcomes of service failure, especially in situations where recovery with compensation is not feasible.

摘要

虽然企业社会责任 (CSR) 对酒店业服务失败后的交易结果有积极影响, 但人们对其对消费者宽恕的影响知之甚少, 尤其是与主观解释和感知的个体差异有关. 我们研究了不同的主观解释 (抽象和具体的心态, 即解释水平) 和感知 (即温情和能力) 如何影响企业社会责任对消费者宽恕的影响. 通过三项涉及不同服务场景的研究, 我们发现企业社会责任有效地诱导了消费者的宽恕, 在那些具有抽象思维 (即高级解释) 的人中, 由于他们的温情判断, 观察到了更强的效果. 这些发现强调了企业社会责任在影响消费者原谅和减轻服务失败的负面后果方面的重要性, 尤其是在不可行的情况下.

Introduction

A service failure refers to a mistake or an issue that occurs during a service encounter, causing a disruption in satisfying customer needs (Koc, Citation2017). Service failures can be categorized into two types: outcome failures, which refers to the service outcome received by customers (e.g., unavailable service) and process failures, which defines the manner of service delivery (e.g., unexpected behaviors of service employees) (Smith et al., Citation1999). In the hospitality industry where there are frequent interactions between service employees and customers, service failures can significantly affect consumer-brand relationship (Byun & Jang, Citation2019). Hospitality firms are particularly concerned about service failures as they can lead to customer dissatisfaction, avoidance, revenge, and unkindness toward them (Alnawas et al., Citation2023; Luo & Mattila, Citation2020). Studies indicate that as high as 91% of dissatisfied customers switch to other brands (TARP, Citation2007), yet many firms remain unaware of their dissatisfied customers since they may not complain or report their dissatisfaction (Kim et al., Citation2010). These negative consequences pose a significant threat to the survival of businesses in the hospitality and tourism sector without effective service recovery measures (Koc, Citation2017). Thus, service research in hospitality and tourism has mainly focused on how recoveries reduce tourists’ anger, revenge, customer switching and avoidance (Mody et al., Citation2020; Sarkar et al., Citation2021). However, previous research has largely ignored service failure from the perspective of the pre-recovery phase (Van Vaerenbergh et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, there is a call to bring new perspectives to service failure research by borrowing theories and concepts in other disciplines, such as organizational behavior and consumer behavior (Koc, Citation2019). Thus, we integrate different theories to the perspective of the pre-recovery phase, where recovery with compensation is not feasible, and suggest a possible link between corporate social responsibility (CSR) and consumer forgiveness.

Previous research has suggested that a firm’s favorable image may reduce the negative feeling and behavioral intention of consumers who experience transgressions. Similar to the reduction of negative motivations among consumers when the transgressing celebrity is perceived as having positive attributes, such as being socially desirable, attractive, or exhibiting less guilt (Rifon et al., Citation2023), firms can cultivate a positive brand image by improving warranty actions, such as engaging in prosocial activities to enhance consumer forgiveness (Wei et al., Citation2020). Consumer forgiveness, characterized as a prosocial change toward a transgressor despite having a hurtful experience (McCullough et al., Citation2000), explains how customer satisfaction can persist despite experiencing service failure, but only when firms have effective recovery measures (Jin et al., Citation2020). However, the extent to which customers will forgive a firm in the absence of adequate service recovery measures such as compensation or apologies, has not been fully investigated (Harrison-Walker, Citation2019; Rasouli et al., Citation2022).

We posit that a customer’s positive perception toward the transgressing firm with a CSR program may help induce forgiveness, even without service recovery. CSR encompasses society’s expectations of organizations to fulfill economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic responsibilities at any given time (Carroll, Citation2016). Prior hospitality research has found that CSR initiatives positively influence consumer perceptions of hotels and restaurants (Srivastava & Singh, Citation2021; Sung & Lee, Citation2023). Although CSR can enhance consumer evaluations even without any compensation, research suggests its impact on transactional outcomes, such as customer satisfaction, is often contingent upon the consumer’s favorable characteristics (Alhouti et al., Citation2021) or additional actions beyond CSR activities, such as interactive engagement on social media (Z. Chen & Hang, Citation2021), fostering a sense of belonging (Bolton & Mattila, Citation2015) or promoting altruistic values (Ahmad et al., Citation2023). Therefore, merely engaging in CSR may not suffice to mitigate the effects of negative events. However, forgiveness theory in social psychology (Worthington et al., Citation2006) suggests that customers may shift their attention from self-interest to goodwill, even amid feelings of hurt and anger following a service failure (Yang & Hu, Citation2021). Therefore, we argue that CSR involvement is sufficient to evoke consumer forgiveness. Individuals who value warmth-based virtues or have a desire to be kind to the transgressor are likely to exhibit mercy and grace (Worthington et al., Citation2006). Similarly, awareness of the transgressing service provider’s CSR efforts may prompt consumers to reframe their perspective, focusing on the positive impact of the firm’s CSR effort rather than dwelling on the service failure. This shift in focus may enhance customer forgiveness, manifesting as increased benevolence, reduced avoidance, and reduced desire for revenge against the service provider.

How do customers change from dwelling on their negative service experience to focusing on others’ perspective, and to be more forgiving? This important question can be explained by considering customers’ perceived warmth and competence, which are influenced by individual differences (i.e., construal level). Drawing insights from social psychology (Aaker et al., Citation2012), we propose that social perceptions, warmth and competence, may be useful in establishing the relationship between a transgressing hospitality firm’s CSR initiatives and consumer forgiveness. Building on construal level theory, individuals with abstract mind-sets tend to think broadly, potentially encompassing the firm’s CSR efforts rather than being fixated on the service failure (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). Conversely, individuals with concrete mind-sets tend to be narrow-minded, may focus on the negative service failure experience. Thus, in the event of service failure, motivating customers to have more abstract mind-sets may help to increase their tendency to forgive the firm. In summary, this study offers a comprehensive investigation on how CSR may facilitate consumer forgiveness in mitigating negative events within the hospitality industry, particularly in scenarios where service recovery is not possible.

Not all hospitality service providers can rectify service failures, especially when customers refrain from lodging complaints (Van Vaerenbergh & Orsingher, Citation2016; Van Vaerenbergh et al., Citation2019). This study seeks to determine when, how and under what conditions consumers are motivated to forgive a socially responsible service provider, thereby making several contributions to the hospitality literature. First, this research demonstrates the effectiveness of a service provider’s CSR activities in magnifying consumer forgiveness. Second, this study shows the mediating role of customer perceptions of warmth and competence underlying these effects. Third, the research offers a novel approach to establish the boundary conditions of construal levels (i.e., abstract or concrete mind-sets) when interpreting information about a company’s CSR effort and their impact on consumer forgiveness. In the subsequent sections, we provide the theoretical background for the hypotheses, detail the research methodology, and present the empirical findings.

Theoretical background

CSR and consumer responses

Previous hospitality and tourism research has demonstrated that socially responsible firms tend to elicit positive responses from consumers, such as intention to stay at hotels (Hsieh et al., Citation2021), willingness to share hospitality providers’ posts (Garcia De Los Salmones et al., Citation2021), positive evaluations of their experiences (Girardin et al., Citation2021), perceived reputation (Azimi et al., Citation2024), repurchase intention (Huang et al., Citation2023), and green word-of-mouth behavior (Nosrati et al., Citation2024). However, these positive responses are contingent upon consumers’ support for the firm’s CSR initiatives (Raza et al., Citation2023) and may vary depending on consumer characteristics (Shin & Hwang, Citation2023), such as consumers’ perceived values (Ahmad et al., Citation2023). For example, the impact of CSR strategies on diners’ emotional attachment and their willingness to pay premium prices at restaurants depends on their perception of the seriousness of environmental issues and ascription of responsibility (Suttikun & Mahasuweerachai, Citation2023). Moreover, consumers’ identification with the company is only likely to occur when they recognize the company’s CSR effort (Xie et al., Citation2015).

However, the benefits of a company’s socially responsible behavior are not always assured. In some cases, CSR initiatives may prove ineffective or may even backfire. Consumers may question the authenticity of the firm’s CSR efforts (Fatma & Khan, Citation2022) and corporate charitable giving may negatively influence hospitality firms’ corporate performance when reaching its optimal point, whereby the charitable giving expenses and/or agency cost exceed the benefits gained (M. H. Chen & Lin, Citation2015). These mixed findings highlight the need for further investigation into the relationship between CSR initiatives and consumer responses.

Nevertheless, in the context of negative events, such as service failures, past research suggests that CSR may increase consumers’ positive responses. For example, CSR efforts contribute to customer satisfaction and trust when a service failure is followed by recovery (Albus & Ro, Citation2017). Consumers are more likely to resist negative information about a socially responsible company when they are aware of environmental and philanthropic CSR practices, thereby increasing their trust (Chuah et al., Citation2022). In conclusion, these findings suggest that to some extent consumers may respond positively to a company’s CSR even when negative events happen.

Although extensive research has investigated the positive effects of CSR, the underlying process, particularly concerning consumer forgiveness toward a prosocial company that has transgressed, remains unclear (Kim & Park, Citation2020). In the absence of service recovery, service failures may reduce customers’ perception of justice, potentially leading to unforgiveness. However, forgiveness theory suggests individuals may be more inclined to forgive offenders when they prioritize moral values, even without receiving compensation or apology (Worthington et al., Citation2006). Similarly, customers may value the benevolence of a socially responsible hospitality firm even when experiencing service failure, placing less emphasis on the notion of fairness. Thus, we expect that CSR is likely to influence consumer forgiveness following a service failure.

CSR and consumer forgiveness

Forgiveness theory suggests that individuals tend to forgive a transgressor by focusing on one of the two virtues (i.e., moral qualities): conscientiousness-based virtue, for example, justice, responsibility, and self-control, or warmth-based virtue, for example, empathy, gratitude, and love (Worthington et al., Citation2006). Those inclined toward conscientiousness-based virtue typically seek to assign blame on the transgressor (Worthington, Citation2009) and may forgive them once the perceived injustice is rectified, such as receiving a compensation (Lucas et al., Citation2018). Similarly, consumers driven by conscientiousness-based virtue may expect service recovery as a precursor to forgiving a hospitality firm after a service failure (Rasouli et al., Citation2022; Yani de Soriano et al., Citation2019). Notably, greater perceived injustice reduces customer satisfaction (Balaji et al., Citation2017) and increases anger (Min & Kim, Citation2019) in a service encounter.

In contrast, warmth-based virtue, which are moral values that focus on kindness, offer a different perspective that remains relatively unexplored in the hospitality context. Individuals who value warmth-based virtue, tend toward mercy and grace, and have a desire to be kind to the transgressor (Worthington et al., Citation2006). Unlike those driven by conscientiousness-based virtue, forgiveness is unconditional for those who value warmth-based virtue. Therefore, customers who value the benevolence of the socially responsible service provider may forgive a transgressing hospitality firm despite the absence of service recovery.

Research indicates that consumers who value firms’ kindness, perceive socially responsible companies as more ethical (Cuesta-Valiño et al., Citation2019) and warmer (Bhattacharya et al., Citation2021). Moreover, under certain situational conditions, kindness may be elicited by psychosocial factors such as context, mood, reciprocity, and type of relationship (Worthington et al., Citation2006). Previous experimental research has successfully manipulated CSR as a situational factor, demonstrating its positive influence on customer responses (Chernev & Blair, Citation2015).

In summary, we postulate that customers may forgive a hospitality firm for its service failure due to their inherent kindness, particularly when they are aware of its CSR efforts. When individuals forgive, they reduce avoidance and revenge motivations, but increase benevolence toward the transgressor (McCullough et al., Citation2007). Accordingly, the following hypothesis is proposed.

H1:

In the event of service failure, consumers are more likely to forgive companies engaged in CSR, leading to (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence.

The mediating role of perceived warmth and perceived competence

It has been noted in social psychology literature that offended parties are more inclined to forgive transgressors if they perceive them positively, such as viewing them as socially desirable or attractive (Lee et al., Citation2015). As a result, offenders are often perceived as less guilty (Hornsey et al., Citation2020). However, while perceived social desirability and attractiveness play a significant role in personal relationships, their relevance in the context of customer-firm interactions is questionable.

Perceived warmth and perceived competence may serve as more pertinent social perceptions in explaining how CSR contributes to consumer forgiveness. CSR efforts may signal the company’s genuine intention for societal wellbeing, aligning with consumers’ warmth judgments such as kindness, generosity, helpfulness, sincerity, and morality (Xie et al., Citation2015). Previous studies suggest that perceived warmth and competence explain 82% of the variance in individual’s perceptions of daily social behaviors (Cuddy et al., Citation2008), including positive perceptions toward green hotels (Gao & Mattila, Citation2014) and positive service evaluations of hospitality service robots (Shan et al., Citation2024).

Furthermore, CSR activities aimed at ensuring ethical workplace conduct (Ferrell et al., Citation2019) or developing strategic solutions for a green environment (Úbeda-García et al., Citation2021) may signal the company’s competency. For instance, Starbucks reduced water consumption by 26.5% through technological innovations, showing its competency in implementing green initiatives (Starbucks, Citationn.d.). Hotels’ efforts to adopt more sustainable business practices (e.g., the InterContinental Hotel Group, Hilton Worldwide, and Marriott International) help increase their competitiveness (Wang et al., Citation2024).

In general, warm individuals are perceived as approachable, while competent individuals as admirable, making both warm and competent individuals likeable (Fiske et al., Citation2007). Consumers generally favor companies perceived as either competent or warm (Aaker et al., Citation2012). Importantly, research in social psychology suggests that people tend to show greater forgiveness and less desire for revenge toward a transgressor who is perceived as likeable or of good character (McCullough, Citation2001). In the context of service failure, CSR can buffer negative perceptions by bolstering the company’s image as warm or competent (Antonetti et al., Citation2021). Previous service research also finds that both perceived warmth and competence are relevant in events of service failure involving prosocial companies (Alhouti et al., Citation2021; Bolton & Mattila, Citation2015). Thus, we postulate that consumer judgments of warmth or competence toward socially responsible firms will further enhance consumer forgiveness.

More formally, the following hypotheses are proposed. In the event of a service failure:

H2:

The effect of CSR on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence will be mediated by perceived warmth.

H3:

The effect of CSR on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence will be mediated by perceived competence.

The moderating role of construal level

When interpreting an object, event, or information, individuals can be classified as either abstract (i.e., high-level construal) or concrete (i.e., low-level construal) thinkers (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). High-level construal involves a focus on broad concepts and less attention to specific details, leading to a general understanding of actions or events. In contrast, low-level construal entails a focus on specific details leading to more contextual understanding. This theory has been successfully applied in studies of consumer perceptions and decision making (Ding et al., Citation2021).

Construal level theory posits that the level of abstraction (low or high) depends on the psychological distance of an action or event (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). Psychological distance refers to the perceived distance from an individual’s direct experience, including temporal, spatial, social, or hypothetical aspects. Specifically, psychologically distant events may include a remote location (i.e., distant spatial distance) (Tversky, Citation2003); a future event (i.e., distant temporal distance) (Liberman et al., Citation2002); an interaction with strangers (i.e., distant social distance) (Wong & Wyer, Citation2016); and a situation with a low probability of happening (i.e., distant hypothetical distance) (Trope & Liberman, Citation2010). Greater distance from an event leads to a more abstract mind-set (Trope et al., Citation2007). Research has shown that different levels of construal result in distinct focus, preferences, and actions (Fujita et al., Citation2006). For instance, individuals with a high-level construal prefer abstract features, while those with a low-level construal prioritize concrete features (Trope & Liberman, Citation2000). Furthermore, consumers tend to have a greater purchase intention when they view the hotel ad that is consistent with their construal level (Dogan & Erdogan, Citation2020).

In the service context, individuals with a high-level construal evaluate a service based on intangible attributes (i.e., abstract features) whereas those with low-level construal focus on tangible attributes (i.e., concrete features) (Ding & Keh, Citation2017). Following a service failure, customers with a high-level construal may focus on abstract aspects, such as a company’s CSR activities, which are distant from the customers, for example, community service in rural areas. Conversely those with a low-level construal may focus on concrete aspects, such as the service failure itself, as it is a close and direct experience. As previously discussed, when customers place greater emphasis on CSR, their perception of warmth and competence toward a prosocial company may be activated. However, if customers only remember the company’s service failure, they may perceive the prosocial company as neither warm nor competent. Further, greater warmth and competence will engender consumer forgiveness. Thus, we expect individuals with greater high-level construal (abstract mind-set) will be more inclined to forgive after a service failure when considering the service provider’s CSR engagement.

Construal level theory has been applied to consumer studies within the context of CSR. For example, research suggests consumers’ construal level can influence their interpretation of a firm’s CSR message (Line et al., Citation2016; Zhang, Citation2014). Specifically, consumers tend to have positive brand evaluations and greater purchase intentions when they perceive congruence between a firm’s CSR message and their construal level (Zhu et al., Citation2017). This demonstrates the relevance of construal level theory in understanding how CSR initiatives influence forgiveness. Past research shows that construal level (high or low) can be primed through their interpretation of situational factors (e.g., object, event, or information) (Ding & Keh, Citation2017). Similarly, a firm’s CSR communication may easily prime customers at a service encounter, leading them to process the event using a more abstract or concrete mind-set.

In summary, it is hypothesized that in the event of a service failure:

H4:

Consumers with a high construal level will perceive a company engaged in CSR as being warmer than those with a low construal level.

H5:

Consumers with a high construal level will perceive a company engaged in CSR as being more competent than those with a low construal level.

H6:

Perceived warmth mediates the interaction effect of CSR and construal level on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence toward the company.

H7:

Perceived competence mediates the interaction effect of CSR and construal level on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence toward the company.

Experiments: studies 1–3

The research hypotheses were examined using three experimental studies. Two pretests were conducted to choose suitable CSR activities and service failure scenarios.

Using Carroll’s (Citation2016) definition of CSR, we focused on society-oriented responsibilities, including ethical (i.e., embrace activities, norms, standards and practices that are not confined by law) and philanthropic responsibilities (i.e., business’s voluntary activities, such as donations and employee volunteerism). Economic (i.e., gaining profit by producing products and services) and legal (i.e., operates according to laws and regulations) responsibilities are not the emphasis in the present study, as our theoretical foundation is based on forgiveness theory (Worthington et al., Citation2006), which is centered around the business’s interest in contributing to societal well-being. In other words, consumer forgiveness is fostered through warmth-based virtue, with the perception that the firm’s CSR motive is genuine and society-centered. Customers will not readily support a firm’s CSR if they perceive the purpose of its CSR is profit driven (Chernev & Blair, Citation2015). Therefore, in the pretest, the activities rated with higher scores on both society-centered motive for CSR (4-item, 7-point Likert-type scale) and importance (1 = Not at all important, 7 = Very important) were used as stimuli in the experiments.

Further, the service failure with moderately severe scenarios (problem, inconvenience, irritation; 1 = minor, 7=major), realistic (1 = not realistic at all, 7 = very realistic), and not difficult to imagine (1 = very difficult, 7 = not difficult at all) were chosen. In addition, we enhanced the external validity of the study by testing the two main types of service scenarios (i.e., outcome failure and process failure) (Smith et al., Citation1999). Specifically, in our study, inattentive staff and errors made by service staff in the service encounter are process failures, while outcome failure includes unavailable service.

Study 1: main and mediating effects

The objectives of Study 1 are to examine the main effects of CSR on consumer forgiveness (avoidance, revenge, and benevolence) and the mediating effects of warmth and competence on the relationships between CSR and consumer forgiveness.

We test the following hypotheses (see ):

H1:

In the event of service failure, consumers are more likely to forgive companies engaged in CSR, leading to (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence.

H2:

The effect of CSR on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence will be mediated by perceived warmth.

H3:

The effect of CSR on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence will be mediated by perceived competence.

Method

Study 1 employed a between-participants design (CSR: available vs. none), where a total of 78 participants (41.8% female, Median age = 30–39 years) who resided in the United Kingdom were recruited through the Prolific online panel. They were paid £0.50 for their participation. Experimental design accepts small sample size, in fact at least 15 participants in each group (control and treatment conditions) is sufficient (Cohen et al., Citation2017).

Only participants who had visited a restaurant in the past 6 months were randomly assigned to one of the two conditions. All participants first read a short introduction about a restaurant with a fictitious brand. In the CSR conditions, participants read about the restaurant’s CSR activity, emphasizing efforts made in reducing waste, whereas in the control condition no information about CSR was given. All participants were then asked to imagine themselves in a described service failure scenario (i.e., an inattentive service staff who made a few mistakes, including forgetting about the beverages) (Appendix 2).

Following that, participants evaluated the extent to which they forgive the restaurant on a 17-item Likert-type scale (McCullough et al., Citation1997) (Appendix 1). They responded to manipulation check questions, including ease of the role-play (1 = very difficult, 7 = not difficult at all), realism of the scenario (1 = not realistic at all, 7 = very realistic), perceived failure severity and perceived company’s CSR motive (only for CSR condition; Bolton & Mattila, Citation2015). They also reported their warmth (warm, kind and generous) and competence (competent, effective, and efficient), using seven-point scales (1 = not at all, and 7 = very much) (Aaker et al., Citation2010).

Results

Manipulation checks

All participants recalled that the service failure involved inattentive service staff. They perceived that the scenario was not hard to imagine (M = 5.92, SD = 1.34), realistic (M = 5.28, SD = 1.62), and moderately severe (α = .81, M = 5.47, SD = 1.11). In the CSR condition, participants successfully recalled reducing waste. They also perceived the company’s motive for CSR as neutral (M = 4.37, SD = .94), indicating the company’s prosocial behavior is neither other-centered (i.e., truly genuine) nor profit-centered.

Consumer forgiveness

A one-way ANOVA demonstrated that perceived failure severity is not significant between the control (M = 4.25, SD = 1.63) and CSR conditions (M = 4.11, SD = 1.65), F(1,77)=.26, p = 0.71). Thus, perceived failure severity was not entered as a covariate.

To test H1a–H1c, a MANOVA was conducted with CSR as the independent variable and avoidance, revenge, and benevolence as dependent variables. A significant main effect of CSR was found on avoidance (MCTRL = 3.62 vs. MCSR = 2.43, F(1, 77) = 7.60, p < 0.01), revenge (MCTRL = 2.71 vs. MCSR = 1.76, F(1, 77) = 8.81, p < 0.01) and benevolence (MCTRL = 4.35 vs. MCSR = 5.20, F(1, 77) = 4.11, p = 0.05). Thus, H1a, H1b, and H1c were supported.

To test H2a–H2c and H3a–H3c, mediation analysis (Hayes, Citation2018; Model 4, bootstrap sample n = 5,000) was performed. Warmth and competence were entered as mediators for the mediation analyses. The results showed significant indirect effects of CSR on avoidance through warmth (b=–.23, 95% CI = [−.55, −.02]) and competence (b = –.25, 95% CI = [−.48, −.05]) (see ). However, the indirect effects of CSR on revenge through warmth (b = .02, 95% CI = [−.10, .16]) and competence (b = -.02, 95% CI = [−.18, .13]) were not significant (). Furthermore, significant mediating effects of warmth (b = .20, 95% CI = [.01, .43]) and competence (b = .20, 95% CI = [.03, .40]) on the relationships between CSR and benevolence were found (). Therefore, warmth and competence mediated the relationship between CSR and avoidance as well as between CSR and benevolence but did not mediate the effect of CSR on revenge, which supports H2a, H2c, H3a and H3c, but rejects H2b and H3b.

Figure 2. Mediating effects on avoidance.

Discussion

The findings lend support to the proposition that acts of CSR can strengthen consumer forgiveness for customers who experience service failure with no recovery, by reducing their intentions to avoid and seek revenge against the hospitality provider and instead, by increasing their motivation to be benevolent. Moreover, it demonstrates that perceived warmth and competence explain how CSR strengthens consumer forgiveness, in terms of reducing avoidance and increasing benevolence.

Notably, it suggests that consumers’ revenge does not rely on the perception of companies’ warmth and competence, indicating other underlying mechanisms in explaining how CSR affects revenge. Desire for revenge is associated with both cognition and emotion (Bernhardt, Citation2020). Thus, attribution of blame (a form of cognition) and anger (a form of emotion) may trigger one to seek revenge when the transgressor is judged to be responsible for the offense (Obeidat et al., Citation2018).

Study 2: moderating effect of construal level

Study 2 aims to examine the moderating effect of construal level for the effect of CSR on perceived warmth and competence. A different type of hospitality service, service failure and CSR contribution were used in Study 2. Additionally, a vignette was used to demonstrate the company’s CSR activity to increase scenario realism.

The two hypotheses are as follows (see ):

H4:

Consumers with a high construal level will perceive a company engaged in CSR as being warmer than those with a low construal level.

H5:

Consumers with a high construal level will perceive a company engaged in CSR as being more competent than those with a low construal level.

Method

Study 2 employed a 2 (CSR: available vs. none) x 2 (construal level: high vs. low) between-subjects factorial design. Using the Prolific online panel, a total of 140 participants (52.5% female, Median age = 30–39 years) who resided in the United Kingdom were recruited and paid £1 for their participation.

Participants who had flown in the past 12 months were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions. The participants were informed that they had to complete two unrelated, separate tasks on consumer decision making. This is to prevent obtrusiveness of the first task involving the manipulation of construal level on the subsequent task, which required participants to evaluate the service delivery of an airline company.

The first task is related to the priming of the construal level (Fujita et al., Citation2006). Categorization in multiple, narrower, and concrete elements (i.e., subordinate categorization) is associated with low-level construals, whereas categorization in fewer, wider, and abstract elements (i.e., superordinate categorization) direct people to high-level construals (Liberman et al., Citation2002). Thus, engaging in these psychological processes should procedurally prime participants to high- and low-level construals. Specifically, participants were presented with 40 nouns (e.g., singer, king, pasta, bag, and soap). Participants under the high-level construal condition were asked to create superordinate category labels based on the question, “___ is an example of what?” For low-level construal, participants were instructed to generate subordinate exemplars by answering the question, “An example of ___ is what?”

Participants were then presented with CSR information (under the CSR condition) vs. corporate information (under the control condition) in the subsequent task (Appendix 3). Participants under the CSR condition also read an excerpt of the airline’s initiatives in reducing water consumption. A fictitious name “Lavene Airway” was used to prevent any bias due to brand familiarity.

All participants were asked to read a passage, then to imagine themselves in a described service failure scenario (i.e., a flight delay) (Appendix 3). Finally, participants submitted their evaluations using the same measures in Study 1.

Results

Preliminary analysis

All participants were able to recall the described service failure scenario, indicating the manipulation is successful (i.e., flight delay). The participants perceived that the scenario was not hard to imagine (M = 5.96, SD = 1.42), realistic (M = 5.85, SD = 1.09), and moderately severe (α =.76, M = 5.56, SD = 1.09). Participants in the CSR condition successfully recalled that the program was about reducing water consumption. They also perceived the company’s motive for CSR as neutral (M = 4.19, SD = 1.04), neither other-centered nor profit- centered.

We used Fujita et al. (Citation2006)’s method to check the manipulation of construal level, where two judges without prior knowledge of the study analyzed the participants’ responses based on the abstractness of responses to the category versus exemplar task. Judges coded a response with a score of −1 when the response met the criterion “[participant’s response] is an example of [word provided],” and a score of + 1 when the response fulfilled the condition “[word provided] is an example of [participant’s response].” A response was coded as 0 when the response fit neither criterion. Construal level index was formed by summing the scores of 40 items, ranging from −40 to + 40. A lower score signals lower construal levels. Finally, the ratings by the two judges were averaged together for a single index of abstractness. As predicted, participants who were assigned the category task significantly generated more abstract responses than those who were assigned the exemplar task (M = 34.2 vs.M = −35.6, p < 0.001).

A two-way ANOVA revealed a non-significant main effect of CSR (F(2, 136) =.66, p = 0.52), non-significant main effect of construal level (F(1, 136) = 2.44, p = 0.12), and non-significant interaction effect of CSR and construal level (F(2, 136) =.57, p = 0.57) on message credibility. These results show that neither CSR nor construal level influenced the participants’ perceived message credibility.

Warmth and competence

A moderation analysis (Hayes, Citation2018; Model 1, bootstrap sample n = 5,000) was performed to test H5 and H6. The results revealed a significant interaction effect of CSR and construal level on warmth (b = .64, p < 0.05) (), and a significant interaction effect of CSR and construal level on competence (b = .76, p < 0.05) (). Among those who saw the excerpt of the CSR report, the high-level construal participants reported greater perceived warmth (MhighCL = 3.61, b = .88, p < 0.01) and competence (MhighCL = 3.37, b = .85, p < 0.01) than low-level construal participants’ perceived warmth (MlowCL = 2.99, b = .24, p = 0.33) and competence (MlowCL = 2.64, b =.09, p = 0.73). As predicted, construal level moderated consumers’ perceived warmth and competence toward a firm’s CSR, thus supporting H4 and H5.

Discussion

Study 2 affirmed the interaction effect of CSR and construal level on perceived warmth and competence. Consumers with high construal perceive socially responsible firms as warmer and more competent than those with low construal level.

Study 3: moderated mediation model

The objective of Study 3 is to test the interaction effect of CSR and construal level on consumer forgiveness via perceived warmth and competence, with different hospitality service, service failure and CSR contribution.

We test the following hypotheses (see ):

H6:

Perceived warmth mediates the interaction effect of CSR and construal level on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence toward the company.

H7:

Perceived competence mediates the interaction effect of CSR and construal level on consumers’ (a) reduced avoidance, (b) reduced revenge, and (c) increased benevolence toward the company.

Method

Study 3 employed a 2 (CSR: available vs. none) x 2 (construal level: high vs. low) between-subjects factorial design. A total of 159 participants (52.5% female, Median age = 30–39 years) who resided in the United Kingdom were recruited from Prolific online panel. They were paid £0.70 for their participation. Participants who had visited a retailer in the past 6 months were randomly assigned to one of the four conditions.

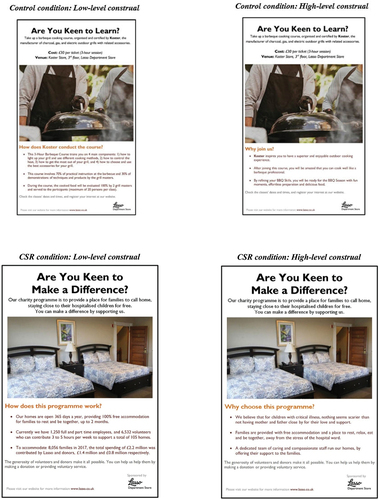

An advertisement was created for each condition, which consists of a pairing of CSR vs. control with high vs. low construal level. A fictitious name “Lasso Department Store” was used. The four advertisements (Appendix 4) include a barbeque cooking class for the no-CSR condition and a children charity program for the CSR condition. Construal level was operationalized using “why” messages to generate an abstract mind-set (e.g., why program was chosen?) and “how” messages for a concrete mind-set (e.g., how does this program work?) from the advertisement (White et al., Citation2011). A pretest (n = 120) indicated that the four pieces of information were perceived as equally comprehensible, credible, and helpful (p > 0.10). A one-way ANOVA analysis showed that participants who read the “why” message significantly generated more abstract responses than those who read the “how” message (M’why’ = 1.9 vs. M’how’ = -2.1, p < 0.05).

All participants read a written service scenario to imagine themselves in that specific scenario, describing stock unavailability and inattentive service personnel (Appendix 4). They responded to the same measures used in Study 2.

Results

Preliminary analysis

All participants were able to recall the described service failure scenario (i.e., unavailable stock and inattentive service personnel). The participants perceived that the scenario was not hard to imagine (M = 5.62, SD = 1.66), realistic (M = 4.76, SD = 1.52), and moderately severe (α = .85, M = 5.83, SD = 1.09). Participants in the CSR condition successfully recalled the CSR program (i.e., providing free accommodation to hospitalized children’s families). They also perceived the company’s motive for CSR as neutral (M = 4.31, SD = 1.17).

To check whether the message credibility of the four advertisements differed from each other, a two-way ANOVA was conducted. The results revealed a non-significant main effect of CSR (F(2, 153) = 1.01, p = 0.72), non-significant main effect of construal level (F(1, 153) = 3.26, p = 0.27) and non-significant interaction effect of CSR and construal level (F(2, 153)=.98, p = 0.65) on message credibility. These results indicated that neither CSR nor construal level influences message credibility.

Consumer forgiveness

To test H6a, H6b, H6c, H7a, H7b and H7c, six separate analyses (Hayes, Citation2018; Model 7, bootstrap sample n = 5,000) were conducted with warmth and competence as mediators and construal level as the moderator.

Avoidance

Results revealed a significant two-way interaction effect of CSR x construal level on warmth (MhighCL = 4.31 vs MlowCL = 3.16, b = .74, p < 0.05), but the main effect of CSR (b = .29, p=0.60) and main effect of construal (b = -.33, p = 0.54) were non-significant. The two-way interaction was mediated by warmth, but not competence (warmth ab= −.19, 95% CI = [−.56 to −.01]; competence ab=−.07, 95% CI = [−.36 to .07]) (). As predicted, construal level moderated consumers’ perceived warmth and subsequently reduced avoidance, which supports H6a and rejects H7a.

Figure 9. Moderated mediation model (DV = avoidance).Notes:Conditional effect of construal levelOn warmth:Low-level: 95% CI = -.55 to -.07;High-level: 95% CI = -.89 to -.09On competence:Low-level: 95% CI = -.44 to -.04;High-level: 95% CI = -.61 to -.05Moderated mediating effectWarmth: 95% CI = -.56 to -.01; Competence: 95% CI = -.36 to .07* p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01; ns = non-significantCoding: No-CSR = 1; CSR = 2; Low-level construal = 1; High-level construal = 2.

Revenge

The two-way interaction of CSR x construal level was not mediated by warmth and competence (warmth ab = −.10, 95% CI = [−.44 to .04]; competence ab= − .04, 95% CI = [−.35 to .04]; ), rejecting H6b and H7b. Follow-up mediation analyses (Hayes, Citation2018; Model 4) revealed the non-significant indirect effect of CSR on revenge through warmth (b = .09, 95% CI = [−.52, .19]) and through competence (b = -.13, 95% CI = [−.40, .07]). A one-way ANOVA showed that the main effect of CSR on revenge (MCTRL = 3.83 vs. MCSR = 3.14, F(1, 158) = 12.28, p < 0.001) was significant, indicating that CSR reduces revenge, without moderation of construal level and mediation of warmth and competence.

Figure 10. Moderated mediation model (DV = revenge).Notes:Conditional effect of construal levelOn warmth:Low-level: 95% CI = -.42 to .10; High-level: 95% CI = -.69 to .18.On competence:Low-level: 95% CI = -.37 to .06; High-level: 95% CI = -.54 to .08Moderated mediating effectWarmth: 95% CI = -.44 to .04; Competence: 95% CI = -.35 to .04* p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01; ns = non-significantCoding: No-CSR = 1; CSR = 2; Low-level construal = 1; High-level construal = 2.

Benevolence

The results revealed that the two-way interaction effect of CSR x construal level on warmth was significant (MhighCL = 4.31 vs MlowCL = 3.16, b = .74, p < 0.05), but the main effect of CSR (b = .29, p = 0.60) and the main effect of construal (b = -.33, p = 0.54) were non-significant. The two-way interaction was mediated by warmth, but not competence (warmth ab = .22, 95% CI = [.01 to .65]; competence ab = .02, 95% CI = [−.04 to .24]) (). The result supports H6c that construal level moderates perceived warmth and subsequently increases benevolence. However, it rejects H7c as construal level does not moderate the effect of CSR on benevolence via perceived competence.

Figure 11. Moderated mediation model (DV = benevolence).Notes:Conditional effect of construal levelOn warmth:Low-level: 95% CI = .08 to .62; High-level: 95% CI = .09 to 1.03.On competence:Low-level: 95% CI = -.09 to .29; High-level: 95% CI = -.12 to .40Moderated mediating effectWarmth: 95% CI = .01 to .65;Competence: 95% CI = -.04 to .24* p < .1; ** p < .05; *** p < .01; ns = non-significantCoding: No-CSR = 1; CSR = 2; Low-level construal = 1; High-level construal = 2.

Discussion

Study 3 demonstrates that perceived warmth, but not competence, mediate the interaction effect of CSR and construal level, by reducing avoidance and increasing benevolence. The result is consistent with past research demonstrating feelings of warmth fosters forgiveness (Bies et al., Citation2016). An individual’s warmth-based morality is stimulated before forgiving (Worthington et al., Citation2006), however, there is a possibility that individuals perceive a person as either warm or competent, but not both (Fiske et al., Citation2007). For example, rich people are perceived as more competent but less warm than poor people (Durante et al., Citation2017). Similarly, a warm firm can be perceived as kind and helpful but incompetent. Under a high construal level condition, perception of warmth would be intensified, avoiding the perception of competence. Thus, the mediation effect of competence is not salient when thinking abstractly (high level construal condition). When a company is perceived as warm, even though less competent, they would be more likely to be forgiven for their mistakes by customers with high-level construal.

Perceived warmth and competence do not mediate the interaction effect of CSR and construal level on revenge. Nevertheless, the main effect of CSR on revenge is significant. This result is consistent with Study 1’s findings, indicating that consumers reduce their revenge but not through their warmth and competence judgments.

Conclusions and implications

This research examines the effect of firms’ socially responsible activity on consumer forgiveness after a failed service delivery without service recovery. We found that CSR can positively influence consumer forgiveness, which leads to decreased avoidance and revenge, as well as increased benevolence toward the service provider. The tendency to forgive is due to the service provider’s CSR initiatives, which has led to their perceptions of warmth and competence toward it. CSR is most effective in enhancing consumer forgiveness when customers have an abstract mind-set (i.e., high-level construal) due to their warmth judgment toward the transgressing firm. Next, we highlight several theoretical implications to advance the service marketing literature as well as offer practical implications for hospitality businesses.

Theoretical contributions

From a theoretical standpoint, this study demonstrates that firms’ prosocial activities can, to a certain extent, motivate consumers to forgive moderate service failures ─ a significant finding, particularly against the conventional wisdom that consumer forgiveness hinges solely on service recovery (Pacheco et al., Citation2018). While a plethora of service research suggests that customers are more willing to forgive when offered service recovery options (Casidy & Shin, Citation2015; Joireman et al., Citation2013), our research shows that including CSR in a business strategy may replace service recovery, and more importantly, may act as an insurance against unforgiveness when service recovery is not feasible. Across different service providers and various forms of service failure (i.e., process and outcome failures), the results from our three studies consistently support the notion that a firm’s prosocial behavior can enhance consumers’ willingness to forgive in the event of service failure, leading to reduced avoidance and revenge seeking behaviors, and fosters more benevolence.

However, for forgiveness to occur, customers must perceive that these CSR activities are genuine and provide meaningful contributions to societal welfare, rather than merely profit-driven gestures (Chernev & Blair, Citation2015). Our results highlight the relevance of warmth-based forgiveness within the service failure context, aligning with forgiveness theories of warmth-based moralities (Worthington et al., Citation2006). By initiating a proactive recovery strategy through CSR initiatives rather than a reactive strategy, such as offering compensation after a service failure, can positively influence customers’ post-failure perceptions, expanding their zone of tolerance (Pereira & Añez, Citation2021).

Furthermore, our research delves into the underlying mechanism – warmth and competence – to explain how CSR affects consumer forgiveness based on construal levels during service failures. When construal levels are not salient, CSR induces forgiveness through perceived warmth and competence; when salient, however, high-level construal relies on perceived warmth in strengthening forgiveness. Notably, both warmth and competence perceptions of firms positively influence consumers’ attitudes and behaviors toward firms (Ivens et al., Citation2015), with warmth deemed more important than competence in consumer evaluation (Jeong & Kim, Citation2021). Our findings are consistent with this stream of research emphasizing the preference of warmth perceptual judgment (Fiske et al., Citation2007). Cultivating warmth toward one’s firm helps to mitigate the negative impact of service failure.

Specifically, this study reveals that under high-level construal, warmth evaluations outweigh competence evaluations in fostering consumer forgiveness. The adoption of a broader view (i.e., more general view) shifts the focus from the specific service failure to the firm’s broader contributions, which would include the firm’s CSR initiatives (if it has one), enhancing perceived warmth, and subsequently forgiveness. This resonates with previous service research where high construal level prompts evaluations of service firm based on the intangible attributes (i.e., decontextualized features, such as service responsiveness and reliability) rather than tangible attributes (i.e., contextualized features, such as the servicescape, furnishings, and amenities) (Ding & Keh, Citation2017).

Finally, to the best of our knowledge, our research represents one of the first applications of construal level theory within the hospitality industry service failure context. We highlight how construal levels influence consumers’ perceptions of warmth and forgiveness after a service failure, emphasizing the critical role of construal level in evaluating forgiveness in the absence of service recovery.

Managerial implications

The current research contributes to hospitality managerial practices by delving into the intersection of CSR and service failure management. While service recovery is recognized as an effective reactive strategy (i.e., initiated after a service failure) in dealing with service failures (Kobel & Groeppel-Klein, Citation2021), this study asserts that a company’s CSR initiatives can act as a proactive strategy (i.e., initiated before a service failure), particularly where service recovery is not feasible. Consequently, hospitality companies should invest in prosocial activities. Specifically, the study emphasizes the importance of philanthropic and ethical aspects in guiding managerial decisions regarding CSR involvement. Philanthropic endeavors can include charitable donations to various marginalized groups, such as orphanages, disability centers, and disaster relief. Ethical considerations emphasize responsible business conduct, driven by the firm’s moral values and not laws and regulations, with a focus on society’s wellbeing, such as minimizing the environmental impact of their business operations.

The study highlights the importance of customers’ perception of warmth over competence in influencing consumer forgiveness after service failure. Warmth toward the company may be cultivated by making customers feel special. Socially responsible companies are encouraged to express their appreciation and care toward their customers through gestures like personalized “thank you” notes or birthday gifts. Moreover, effective CSR communication should frame their messages to evoke warmth (Clark et al., Citation2019). For example, instead of just providing facts and figures, hospitality companies could leverage storytelling to convey the impact of its CSR initiatives.

The findings suggest that abstract information, focusing on the general benefits of the CSR program is more effective than providing concrete details (e.g., every single detail of the CSR program). By emphasizing the “why” rather than the “how” of CSR actions, companies can stimulate high-level, abstract thinking and mitigate skepticism toward their motives. Using the why (vs. how) message frame, focuses on reasons for taking an action, generating more abstract (vs concrete) mind-sets (White et al., Citation2011). Therefore, informing consumers about the general benefits of its CSR programs should lead them to think about why such CSR activities are beneficial. For example, McDonalds portrays itself as a good corporate citizen by using the tagline, “Charity, feed the mind and the soul” and Starbucks uses the tagline, “the earth really doesn’t need us” in their communication materials. With better communication, service firms may enjoy reciprocal benefits in the future, that is, increasing the possibility of consumer forgiveness, in the event of service failure.

Nevertheless, it is crucial to note that the positive impact of hospitality providers’ CSR involvement hinges on consumers perceiving the company’s engagement as genuinely sincere (Ellen et al., Citation2006). Effective communication plays a pivotal role here, and our findings suggest employing abstract information in CSR communication can help mitigate skepticism toward CSR programs. Providing excessive details about CSR activities may inadvertently create a perception of ulterior motives, detracting from the authenticity of the company’s CSR efforts. Thus, managers of hospitality companies are encouraged to use abstract information rather than concrete details in their CSR announcements to alleviate unnecessary skepticism about the firm’s CSR motives.

To ensure genuine engagement with CSR, hospitality managers should continuously reinforce their messages through strategic placement of CSR information in public spaces where service interaction occur (e.g., a restaurant’s dining table, a hotel room, and in front of the passenger seat of the plane). A simple headline may remind customers without being too excessive. For instance, Marriott International uses “Serve 360: Doing good in every direction,” while McDonald’s initiates “Change a little, Change a lot.”

Limitations and future research

While this research has provided insights into the role of CSR and forgiveness, some caution is needed when generalizing the findings and conclusions. First, although we used three experiments with different types of CSR activities and service failure scenarios, the results may not be generalized to include all CSR activities. In this research, we used Carroll’s (Citation2016) CSR categorization of activities, namely, ethical and philanthropic responsibilities. Ethical CSR scenarios included reducing waste and reducing water consumption, and philanthropic, was about providing free accommodation to the needy. Both ethical and philanthropic activities have been found to have positive impact on consumer responses through enhancing society-oriented value (Peloza & Shang, Citation2011). However, we did not include the economic (i.e., profit) dimension in Carroll’s (Citation2016). According to Golob et al. (Citation2008), self-transcendent consumers have greater expectations for both ethical and philanthropic dimensions, whereas self-enhancement consumers prefer the economic dimension. Therefore, future research could build on the present study by investigating whether different types of consumers (self-enhancing versus self-transcending) show varying levels of forgiveness in the service context when hospitality providers implement economic, ethical and philanthropic CSR programs.

Second, we investigated service failure scenarios that are moderately severe from the perception of customers (i.e., inattentive service staff, flight delay, unavailable service). Service research includes perceived severity to determine the extent of a customer’s perceived intensity toward a particular service problem (Joireman et al., Citation2013). Severe service failure prevents consumers from forgiving and increases the chances of switching to another service provider and spreading negative word of mouth (Tsarenko & Tojib, Citation2012). Based on our investigation, we can only conclude that customers tend to forgive prosocial hospitality firms in the context of moderately severe service failure, but not in the event of extremely severe failures.

Third, although this research operationalized construal levels using: 1) superordinate categorization and subordinate exemplars (Fujita et al., Citation2006), and 2) abstract “why” vs. concrete “how” messages (White et al., Citation2011), other operational definitions of construal level could be explored, such as various dimensions of psychological distance (i.e., temporal, spatial, social, and hypothetical distance) (Lynch & Zauberman, Citation2007). Prior consumer research demonstrated that operationalization of construal level in terms of psychological distance influences preferred attributes in service evaluation (Ding & Keh, Citation2017), recycling intentions and behaviors (White et al., Citation2011), and purchase intentions (Jin & He, Citation2013). One method of gaining a robust understanding of construal level application in services marketing is to operationalize construal levels differently, which could provide some evidence of generalizability across different operationalization of construal level.

Fourth, one potential future research relates to the possibility that the effect of CSR may be attenuated for companies with a strong customer-firm relationship. Customers who have strong relationships with a company feel more betrayed after a service failure (Harmeling et al., Citation2015), which may turn the company’s best customers into its worst enemies (Sinha & Lu, Citation2016). Thus, future studies may include customer-firm relationship as a potential moderator.

Fifth, this research was conducted using respondents solely from the United Kingdom. However, it is important to recognize that in international contexts, cultural orientations may significantly influence how customers evaluate service encounters (Baker, Citation2017). Hence, it may be worthwhile including Hofstede’s cultural dimensions in future studies, for example, future research could investigate forgiveness, CSR and service failure by using Hofstede et al. (Citation2010) dimension of restraint and indulgence. Restraint cultures are cultures where positive emotions are less freely expressed and indulgent cultures tend to be more positive and emphasize individual happiness and well-being (MacLachlan, Citation2013). Customers from restraint cultures may evaluate a service more negatively due to their propensity to recall negative emotions stemming from their cynicism and pessimism (Koc, Citation2020). Conversely, customers from an indulgence culture, such as the United Kingdom may be more inclined to remember the positive emotions associated with a service experience because of their optimism.

Apart from being an indulgent culture, the United Kingdom is characterized as masculine rather than feminine (Hofstede et al., Citation2010). This cultural orientation may influence how customers perceive a firm’s CSR. Masculine cultures, which prioritize material gain and economic success, often exhibit a negative outlook on CSR, while feminine cultures, characterized by caring for others and sympathy, tend to support CSR initiatives (Kang et al., Citation2016). However, it is noteworthy that despite being masculine, this research found that the United Kingdom tends to be forgiving in the service failure context when hospitality firms engage in CSR activities. Despite the association of masculinity with assertiveness, individuals in masculine cultures respect the rights and dignity of others (Koc, Citation2010). Building on this observation, future studies could explore and compare the responses of hospitality customers from both masculine and feminine cultures toward similar CSR and failure scenarios.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aaker, J. L., Garbinsky, E. N., & Vohs, K. D. (2012). Cultivating admiration in brands: Warmth, competence, and landing in the “golden quadrant”. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 22(2), 191–194. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2011.11.012

- Aaker, J. L., Vohs, K. D., & Mogilner, C. (2010). Nonprofits are seen as warm and for-profits as competent: Firm stereotypes matter. Journal of Consumer Research, 37(2), 224–237. https://doi.org/10.1086/651566

- Ahmad, N., Ahmad, A., Lewandowska, A., & Han, H. (2023). From screen to service: How CSR messages on social media shape hotel consumer advocacy. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 33(3), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2023.2271448

- Albus, H., & Ro, H. (2017). Corporate social responsibility: The effect of green practices in a service recovery. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 41(1), 41–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348013515915

- Alhouti, S., Wright, S. A., & Baker, T. L. (2021). Customers need to relate: The conditional warm glow effect of CSR on negative customer experiences. Journal of Business Research, 124, 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.11.047

- Alnawas, I., Al Khateeb, A., Abu Farha, A., & Ndubisi, N. O. (2023). The effect of service failure severity on brand forgiveness: The moderating role of interpersonal attachment styles and thinking styles. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 35(5), 1691–1712. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2022-0290

- Antonetti, P., Crisafulli, B., & Maklan, S. (2021). When doing good will not save us: Revisiting the buffering effect of CSR following service failures. Psychology & Marketing, 38(9), 1608–1627. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21531

- Azimi, M., Sadeghvaziri, F., Ghaderi, Z., & Michael Hall, C. (2024). Corporate social responsibility and employer brand personality appeal: Approaches for human resources challenges in the hospitality sector. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 33(4), 443–469. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2023.2258865

- Baker, M. (2017). Service failures and recovery: Theories and models. In E. Koc (Ed.), Service failures and recovery in tourism and hospitality (pp. 27–41). CABI.

- Balaji, M. S., Roy, S. K., & Quazi, A. (2017). Customers’ emotion regulation strategies in service failure encounters. European Journal of Marketing, 51(5), 960–982. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-03-2015-0169

- Bernhardt, F. (2020). Forgiveness and revenge. In T. Szanto & H. Landweer (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of phenomenology of emotion (pp. 497–508). Routledge.

- Bhattacharya, A., Good, V., Sardashti, H., & Peloza, J. (2021). Beyond warm glow: The risk-mitigating effect of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Journal of Business Ethics, 171(2), 317–336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04445-0

- Bies, R. J., Barclay, L. J., Tripp, T. M., & Aquino, K. (2016). A systems perspective on forgiveness in organizations. The Academy of Management Annals, 10(1), 245–318. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2016.1120956

- Bolton, L. E., & Mattila, A. S. (2015). How does CSR affect consumer response to service failure in buyer–seller relationships? Journal of Retailing, 91(1), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2014.10.001

- Byun, J., & Jang, S. (2019). Can signaling impact customer satisfaction and behavioral intentions in times of service failure? Evidence from open versus closed kitchen restaurants. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(7), 785–806. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1567432

- Carroll, A. B. (2016). Carroll’s pyramid of CSR: Taking another look. International Journal of Corporate Social Responsibility, 1(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40991-016-0004-6

- Casidy, R., & Shin, H. (2015). The effects of harm directions and service recovery strategies on customer forgiveness and negative word-of-mouth intentions. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 27, 103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2015.07.012

- Chen, Z., & Hang, H. (2021). Corporate social responsibility in times of need: Community support during the COVID-19 pandemics. Tourism Management, 87, 104364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2021.104364

- Chen, M. H., & Lin, C. P. (2015). The impact of corporate charitable giving on hospitality firm performance: Doing well by doing good? International Journal of Hospitality Management, 47, 25–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2015.02.002

- Chernev, A., & Blair, S. (2015). Doing well by doing good: The benevolent halo of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Consumer Research, 41(6), 1412–1425. https://doi.org/10.1086/680089

- Chuah, S. H. W., Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Aw, E. C. X., & Tseng, M. L. (2022). Lord, please save me from my sins! Can CSR mitigate the negative impacts of sharing economy on consumer trust and corporate reputation? Tourism Management Perspectives, 41, 100938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2022.100938

- Clark, J. L., Green, M. C., Simons, J. J., & Shook, N. J. (2019). Narrative warmth and quantitative competence: Message type affects impressions of a speaker. PLOS ONE, 14(12), e0226713. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0226713

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research Methods in Education. Routledge.

- Cuddy, A. J., Fiske, S. T., & Glick, P. (2008). Warmth and competence as universal dimensions of social perception: The stereotype content model and the BIAS map. In M. P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (Vol. 40, pp. 61–149). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0

- Cuesta-Valiño, P., Rodriguez, P. G., & Nuñez-Barriopedro, E. (2019). The impact of corporate social responsibility on customer loyalty in hypermarkets: A new socially responsible strategy. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 26(4), 761–769. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1718

- Ding, Y., & Keh, H. T. (2017). Consumer reliance on intangible versus tangible attributes in service evaluation: The role of construal level. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45(6), 848–865. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-017-0527-8

- Ding, Y., Zhong, J., Guo, G., & Chen, F. (2021). The impact of reduced visibility caused by air pollution on construal level. Psychology & Marketing, 38(1), 129–141. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.21427

- Dogan, M., & Erdogan, B. Z. (2020). Effects of congruence between individuals’ and hotel commercials’ construal levels on purchase intentions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(8), 987–1007. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2020.1759172

- Durante, F., Tablante, C. B., & Fiske, S. T. (2017). Poor but warm, rich but cold (and competent): Social classes in the stereotype content model. Journal of Social Issues, 73(1), 138–157. https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12208

- Ellen, P. S., Webb, D. J., & Mohr, L. A. (2006). Building corporate associations: Consumer attributions for corporate socially responsible programs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 34(2), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092070305284976

- Fatma, M., & Khan, I. (2022). An investigation of consumer evaluation of authenticity of their company’s CSR engagement. Total Quality Management & Business Excellence, 33(1–2), 55–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14783363.2020.1791068

- Ferrell, O. C., Harrison, D. E., Ferrell, L., & Hair, J. F. (2019). Business ethics, corporate social responsibility, and brand attitudes: An exploratory study. Journal of Business Research, 95, 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.039

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.005

- Fujita, K., Trope, Y., Liberman, N., & Levin-Sagi, M. (2006). Construal levels and self-control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(3), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.3.351

- Gao, Y. L., & Mattila, A. S. (2014). Improving consumer satisfaction in green hotels: The roles of perceived warmth, perceived competence, and CSR motive. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 42, 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2014.06.003

- Garcia De Los Salmones, M. D. M., Herrero, A., & Martinez, P. (2021). CSR communication on Facebook: Attitude towards the company and intention to share. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(4), 1391–1411. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-09-2020-1054

- Girardin, F., Bezencon, V., & Lunardo, R. (2021). Dealing with poor online ratings in the hospitality service industry: The mitigating power of corporate social responsibility activities. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 63, 102676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102676

- Golob, U., Lah, M., & Jancic, Z. (2008). Value orientations and consumer expectations of corporate social responsibility. Journal of Marketing Communications, 14(2), 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527260701856525

- Harmeling, C. M., Palmatier, R. W., Houston, M. B., Arnold, M. J., & Samaha, S. A. (2015). Transformational relationship events. Journal of Marketing, 79(5), 39–62. https://doi.org/10.1509/jm.15.0105

- Harrison-Walker, L. J. (2019). The critical role of customer forgiveness in successful service recovery. Journal of Business Research, 95, 376–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.049

- Hayes, A. F. (2018). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: a regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford Publications.

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organizations: software of the mind (3rd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

- Hornsey, M. J., Wohl, M. J., Harris, E. A., Okimoto, T. G., Thai, M., & Wenzel, M. (2020). Embodied remorse: Physical displays of remorse increase positive responses to public apologies, but have negligible effects on forgiveness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 119(2), 367. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000208

- Hsieh, Y. J., Chen, Y. L., & Wang, Y. C. (2021). Government and social trust vs. hotel response efficacy: A protection motivation perspective on hotel stay intention during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 97, 102991. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102991

- Huang, S., Wang, X., & Qu, H. (2023). Impact of perceived corporate social responsibility on peer-to-peer accommodation consumers’ repurchase intention and switching intention. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 32(7), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2023.2214549

- Ivens, B. S., Leischnig, A., Muller, B., & Valta, K. (2015). On the role of brand stereotypes in shaping consumer response toward brands: An empirical examination of direct and mediating effects of warmth and competence. Psychology & Marketing, 32(8), 808–820. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.20820

- Jeong, H. J., & Kim, J. (2021). Human-like versus me-like brands in corporate social responsibility: The effectiveness of brand anthropomorphism on social perceptions and buying pleasure of brands. Journal of Brand Management, 28(1), 32–47. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41262-020-00212-8

- Jin, D., Di Pietro, R. B., & Fan, A. (2020). The impact of customer controllability and service recovery type on customer satisfaction and consequent behavior intentions. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 29(1), 65–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1602095

- Jin, L., & He, Y. (2013). Designing service guarantees with construal fit: Effects of temporal distance on consumer responses to service guarantees. Journal of Service Research, 16(2), 202–215. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670512468330

- Joireman, J., Grégoire, Y., Devezer, B., & Tripp, T. M. (2013). When do customers offer firms a “second chance” following a double deviation? The impact of inferred firm motives on customer revenge and reconciliation. Journal of Retailing, 89(3), 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2013.03.002

- Kang, K. H., Lee, S., & Yoo, C. (2016). The effect of national culture on corporate social responsibility in the hospitality and tourism industry. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 28(8), 1728–1758. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2014-0415

- Kim, J., & Park, T. (2020). How corporate social responsibility (CSR) saves a company: The role of gratitude in buffering vindictive consumer behavior from product failures. Journal of Business Research, 117, 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.024

- Kim, M. G., Wang, C., Mattila, A. S., & Baloglu, S. (2010). The relationship between consumer complaining behavior and service recovery: An integrative review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 22(7), 975–991. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596111011066635

- Kobel, S., & Groeppel-Klein, A. (2021). No laughing matter, or a secret weapon? Exploring the effect of humor in service failure situations. Journal of Business Research, 132, 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.034

- Koc, E. (2010). Services and conflict management: Cultural and European integration perspectives. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 34(1), 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.08.003

- Koc, E. (2017). Service failures and recovery in tourism and hospitality: A practical manual. CABI.

- Koc, E. (2019). Service failures and recovery in hospitality and tourism: A review of literature and recommendations for future research. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 28(5), 513–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2019.1537139

- Koc, E. (2020). Cross-cultural aspects of tourism and hospitality: a services marketing and management perspective. Routledge.

- Lee, J. S., Kwak, D. H., & Moore, D. (2015). Athletes’ transgressions and sponsor evaluations: A focus on consumers’ moral reasoning strategies. Journal of Sport Management, 29(6), 672–687. https://doi.org/10.1123/JSM.2015-0051

- Liberman, N., Sagristano, M. D., & Trope, Y. (2002). The effect of temporal distance on level of mental construal. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(6), 523–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1031(02)00535-8

- Line, N. D., Hanks, L., & Zhang, L. (2016). Sustainability communication: The effect of message construals on consumers’ attitudes towards green restaurants. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 57, 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2016.07.001

- Lucas, T., Strelan, P., Karremans, J. C., Sutton, R. M., Najmi, E., & Malik, Z. (2018). When does priming justice promote forgiveness? On the importance of distributive and procedural justice for self and others. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13(5), 471–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1303533

- Luo, A., & Mattila, A. S. (2020). Discrete emotional responses and face-to-face complaining: The joint effect of service failure type and culture. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 90, 102613. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2020.102613

- Lynch, J. G., Jr., & Zauberman, G. (2007). Construing consumer decision making. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 17(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1057-7408(07)70016-5

- MacLachlan, M. (2013). Indulgence vs. Restraint – the 6th dimension. Retrieved May 9, 2024. from https://www.communicaid.com/cross-cultural-training/blog/indulgence-vs-restraint/

- McCullough, M. E. (2001). Forgiveness: Who does it and how do they do it? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 10(6), 194–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00147

- McCullough, M. E., Bono, G., & Root, L. M. (2007). Rumination, emotion, and forgiveness: Three longitudinal studies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(3), 490–505. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.490

- McCullough, M. E., Pargament, K. I., & Thoresen, C. A. (2000). Forgiveness: Theory, research, and practice. Guilford Press.

- McCullough, M. E., Worthington, E. L., Jr., & Rachal, K. C. (1997). Interpersonal forgiving in close relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(6), 1586–1603. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1586

- Min, H. K., & Kim, H. J. (2019). When service failure is interpreted as discrimination: Emotion, power, and voice. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 82, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2019.03.017

- Mody, M. A., Lu, L., & Hanks, L. (2020). “It’s not worth the effort”! Examining service recovery in Airbnb and other homesharing platforms. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 32(9), 2991–3014. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-03-2020-0184

- Nosrati, S., Altinay, L., & Darvishmotevali, M. (2024). Multiple mediating effects in the association between hotels’ eco-label credibility and green WOM behavior. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/19368623.2024.2356524

- Obeidat, Z. M., Xiao, S. H., Al Qasem, Z., Dweeri, A., & Obeidat, A. (2018). Social media revenge: A typology of online consumer revenge. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 45, 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2018.09.010

- Pacheco, N. A., Pizzutti, C., Basso, K., & Van Vaerenbergh, Y. (2018). Trust recovery tactics after double deviation: Better sooner than later? Journal of Service Management, 30(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-02-2017-0056

- Peloza, J., & Shang, J. (2011). How can corporate social responsibility activities create value for stakeholders? A systematic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 39(1), 117–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-010-0213-6

- Pereira, E., & Añez, M. E. M. (2021). Why are you so tolerant? Towards the relationship between consumer expectations and level of involvement. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 60, 102467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2021.102467