ABSTRACT

This paper introduces the concept of ‘object habits’ for diversifying the scope of museum histories. The term is shorthand referring to an area’s customs relating to objects, taking into account factors that influence the types of things chosen, motivations for collecting, modes of acquisition, temporal variations in procurement, styles of engagements with artefacts or specimens, their treatment, documentation and representation, as well as attitudes to their presentation and reception. These customs emerge not only within the museum or out in the field, but significantly between the two, within the full agency of the world. The articles in this special issue explore the potential of ‘object habits’ in relation to the history of museums and collections across a selection of disciplines and a range of object types, including ancient artefacts, natural history specimens, archival documents, and photographic evidence.

For many subjects fieldwork is central to their identity, and the objects procured during such activities are fundamental to the production of disciplinary knowledge. The material results of archaeological, anthropological, paleontological, and natural historical enquiry are commonly encountered in museums, with their transmission to those spaces usually being narrated in public displays (if at all) as linear, passive, and inevitable. In museological discourse approaches to such histories are more critical, yet they still tend either to privilege the agencies of particular collectors—be they fieldworkers, patrons, or indigenous peoples—or to over-emphasise the role of institutional and intellectual cultures in framing the meanings of objects.Footnote1 The point of departure for this special issue is the contention that acquisition of material in the field and its accommodation within museums owe as much to wider social attitudes, circumstances, and customs towards things as they do to the agency of collectors, intellectual debates, or museum politics. Crucially, such attitudes may be highly variable both at any one historical moment and over time.

The crucial importance of this wider context has been thrown into relief by the research project ‘Artefacts of Excavation’, which is exploring the scale, scope, and significance of the distribution of artefacts from British fieldwork in Egypt to institutions across the world from 1880 onward. Out of this large study we briefly survey here a few historical aspects of the British collection of Egyptian antiquities in order to illustrate the potential of an object habit approach to museum histories. In particular, the model valuably frames investigation into shifts in attitudes towards collections and acquisitions, which were keenly sought in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, yet after the Second World War were increasingly viewed as dispensable. Such changes were not driven solely by museum practices or disciplinary developments, but by wider concerns.

There is no single, uniform object habit, and in April 2016 we convened a conference at University College London to explore the potential of this idea in relation to a range of subjects and museum contexts. Revised versions of six papers from the conference are published in this special issue, together with a new framing paper by Libonati. The articles present historically rich accounts of museum collections that were formed through expeditions serving disciplines from archaeology to palaeontology and that encompassed developing research questions and techniques. We suggest that these contributions show how museum histories need not just chronicle discoveries or provide uncritical biographies of field collectors. These histories leave complex legacies that museums need to confront in the present as object habits continue to shift. Museums have a responsibility to understand the multiplicity of traditions of practices towards things and to reflect critically on their implications.

1. The object habit

The ‘material turn’ across the social sciences and humanities has saturated discussions with a variety of perspectives on materiality, the nature of things, and relationships formed with and among them.Footnote2 Study of the formation of collections and museums in particular has benefited from two decades of scholarship building upon conceptions of object biographiesFootnote3 and resulting in productive analytical frameworks such as the relational museumFootnote4 or, following Bruno Latour’s Actor-Network-Theory (ANT),Footnote5 the idea of museum assemblages.Footnote6 These agendas have brought into relief the shifting value of artefacts throughout their life-courses and have highlighted how museums operate within extensive socio-material networks that link collecting in the field with the museum. Despite this wealth of studies, we perceive two reasons for introducing another concept into this theoretical arena. First, the term ‘object habit’ can usefully open up what may tend towards rather circumscribed and inward-looking areas of enquiry that are isolated from parallel and contingent phenomena in the wider world. Second, the idea of object habits can foreground the materiality of things—in the widest sense—against the grain of studies that are frequently more attentive to social relationships forged during processes of collecting than to the material prerequisites of those relationships.

The idea that disciplines and museums make their objects, and in the process ‘make themselves’, has been explored through case studies demonstrating that an ethnographic thing, archaeological object, or natural history specimen is not what it is simply because it was found in a particular fieldwork setting, but by virtue of how it is detached from that setting and informed by museum practices.Footnote7 In this regard the work of Michel Foucault has been especially dominant in Museum Studies, casting museums as institutions of the Enlightenment whose authority to acquire and display things was intimately linked to imperialism and capitalism, and which deployed ordered knowledge within institutionally controlled spaces.Footnote8 Yet as John MacKenzie rightly cautioned, museums function in the real world; we should not claim too much for them.Footnote9 Similarly, Anthony Shelton has argued that collections are not simply paradigmatic representations subject to particular disciplinary constraints.Footnote10 Over-determined, top-down accounts of the power of museums to shape identities as ‘purveyors of ideology and of a downward spread of knowledge to the public’ are apt to overlook other forces that resist, disrupt, or instigate museum trends.Footnote11 This is not to say that museums did not act as sites for shaping behaviours and consciousness, but that factors beyond issues of power conditioned visitors’ and museums curators’ attitudes to things and that these factors need evaluation.

A good example of an alternative to such museum histories is the work of Glenn Penny, who has analysed the rise of ethnographic collections in Germany, demonstrating how a variety of pressures—from the market, entertainment industry, professionalisation, and the demands of a socially diverse audience—shaped museum practices and ideologies.Footnote12 In his history, rather than museums being the instigators of nationalist or imperial collecting practices, external attitudes are seen to have largely led museums and ethnographers to abandon Humboldtian liberal and cosmological aspirations for their collections, not least because visual displays proved difficult to control. Historically-rich understandings of the ‘coming into being’ of museums such as Penny’s form one goal of an object-habit study.Footnote13

In the ambition to situate museums in the full agency of the world, the idea of ‘object habits’ has the benefit of offering a heuristic anchor. It can encourage us to keep the artefact or specimen in focus as we tack back and forth between the museum and the field. Models such as the ‘relational museum’, developed at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, while helpful for examining how museums draw particular sets of relationships between people and things into themselves, can lead to narratives that are more people-centred than object-centred.Footnote14 There is no doubt that, as Chris Gosden and Chantal Knowles note, ‘there is a series of continuous social relations surrounding the object connecting “field” and “museum”’, but this is a material as well as a social phenomenon.Footnote15 A more object-centred approach to museum histories can be found in the work of historians such as Stephen Conn, who has looked beyond museum object practices towards social attitudes to things in settings like the American home, which also impinged upon institutional and intellectual rhetoric.Footnote16

Thus, the object habit encompasses the wider phenomenon and associated practices of collecting material culture and specimens out of ethnographic, cultural, and historical interest. The term is appropriated from the ‘epigraphic habit’, a movement by ancient historians to transcend texts and consider the historical, cultural, and social factors that led to their production.Footnote17 By adopting the framework of the ‘epigraphic habit’ classical scholars have been able to foreground a large range of influences which led to the creation of an inscribed thing, considering the different audiences which produced the texts—the commissioners, the commemorated, and the different communities that might encounter the text. The concept of the object habit does the same sort of work. It maintains the integrity of the object while allowing audiences, including acquirers and curators, to shift over time and space, permitting analyses of different and competing conceptions of a thing to exist simultaneously.

The term ‘object habit’ is a shorthand for an area’s customs relating to objects, taking into account factors that influence the types of things chosen, temporal variations in procurement, styles of engagement with artefacts or specimens, their treatment, documentation and representation, as well as attitudes to their presentation and reception. These customs emerge not just within the museum or out in the field, but between the two and affected by the full agency of the world. The idea of object habits encourages exploration of a multiplicity of intersecting factors that might enable, condition, and constrain what gets collected, from where, when, and why.

2. Artefacts of excavation: a case study

The public, in subscribing to the Egypt Exploration Fund, appreciated the fact that they were making a good investment for the British Museum and for our provincial collections.Footnote18

Distribution of excavation material by previous generations of Egyptologists has always struck me as a monstrous practice.Footnote19

The well-documented nineteenth-century spread of museums across the UK, spurred by industrialisation and imperial expansion, provided the political impetus, the financial resources, and the transport infrastructures through which objects and specimens from across the Empire percolated to the all corners of the United Kingdom, as well to other countries in Europe, America, Africa, and Australasia. The establishment of the EEF in 1882 was co-incident with these domestic transformations and international shifts in power. Notably, the very same month that the EEF’s foundation was announced in the national press, British and French warships approached Egypt, and a few months later the British navy began to bombard Alexandria, in a violent harbinger of the veiled protectorate that dominated Egypt for decades. Scientific authority over Egyptian antiquities went hand in hand with colonial control of Egypt, tempered by nationalistic tensions between the French, who remained in charge of the Antiquities Service, and British scholars who eagerly sought influence over it (while British diplomats like Evelyn Baring did not).Footnote23 Intellectually, much emphasis has been placed on the collecting practices of the archaeologist W. M. Flinders Petrie (1853–1942), who stepped into this fray. Petrie is frequently credited as being the ‘father of scientific archaeology in Egypt’, and his attention to acquiring unassuming artefacts for archaeological inference and typological classification has long been recounted and lauded in museum text panels. All of these factors, however, were the means rather than the ends for acquiring Egyptian objects.

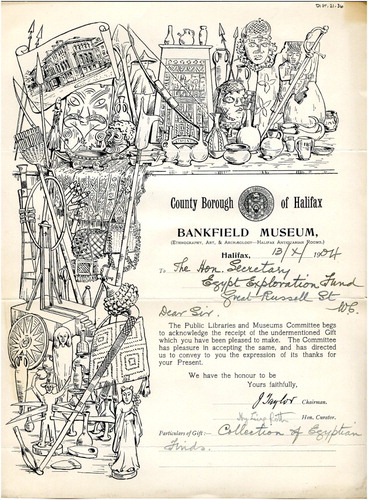

Between 1883 and 1915, the EEF dispatched excavated finds to around seventy-three UK institutions, from large national museums like the British Museum to provincial organisations such as Truro Museum in Cornwall and Bankfield Museum in Halifax (). Beneficiaries included public libraries, as well as private schools like Eton and Harrow in England. Rather than simply addressing why Egyptian antiquities in a generic sense were so widely sought, it is informative to consider the specific character of the artefacts that were being offered by the EEF to these museums. Strikingly, the lists of antiquities dispatched to the UK’s museums principally document masses of unprepossessing things—scraps of bronze-work, undecorated pottery vessels, and fragmentary implements—as opposed to the unique works of art or impressive monuments that the ‘heroic’ archaeology of the earlier nineteenth century had supplied to places like the British Museum.Footnote24 In part, this is due to the opportunistic nature of collecting in Egypt because antiquities laws more readily identified the unique and colossal, rather than small and incidental, as subject to state control. Once in Britain, it could be argued that the imposition of classificatory schemes within galleries to educate the public led to an appreciation of the value of these ‘minor antiquities’. Such an explanation might fit with narratives of development of museums at this time which, as several scholars have noted, was predicated upon an ‘epistemology of things’.Footnote25 In this framework, knowledge about the world could be conveyed by assembling and mobilising ‘material facts’ within dense, typological displays, most famously embodied first in London’s South Kensington Museum (now the Victoria and Albert) and then in the University of Oxford’s Pitt Rivers Museum. Yet the impact of these initiatives, as well as the emphasis that was placed on the power of objects to achieve these aims, were not just representational: objects arguably held a more privileged ontological status for many people in the long Victorian period than was the case in subsequent generations. The explanatory potential of this hypothesis becomes clearer when a trajectory of several decades of object habits is examined.

Figure 1. 1904 certificate of thanks from Bankfield Museum for objects presented by the Egypt Exploration Fund. The vignettes illustrate the dense universalist displays of world culture towards which UK municipal museums aspired in the early twentieth century. Courtesy of the Egypt Exploration Society, Lucy Gura archive, DIST.21.36.

In the case of collecting Egypt, religious convictions provided a significant driving force behind the hunt for antiquities in the Victorian period.Footnote26 In this framework artefacts were not merely illustrations of the reality of the Bible: for many they made religious knowledge immediate. Take for instance the establishment in the late 1880s of the Sunday-School Teachers’ Institute on London’s Fleet Street, which acquired small trinkets like faience rings from the EEF’s 1884–86 Delta fieldwork for its museum in Serjeants’ Inn.Footnote27 Its curator, Reverend J. G. Kitchin, passionately advocated ‘object-lessons by which God revealed Himself and His thoughts to man’, within which artefacts and specimens were ‘like pictures in which God desired the people to see many important truths’.Footnote28 The promise of object revelations of this sort similarly motivated occult engagements with antiquities, with organisations such as the Hermetic Order Golden Dawn relying heavily upon encounters with museum antiquities.Footnote29 Meanwhile, the idea of ‘object lessons’ referred to by Kitchin had become a mainstay of Victorian educationalist reform, with tangible goods considered vital pedagogical tools. Schools across the UK consequently scrambled to accumulate commonplace things to use in the classroom, also attempting to create makeshift museum-like storage for them.Footnote30 For the independently wealthy Eton and Harrow, this was not a problem: they had their own private museums furnished with genuine ancient finds procured through the EEF.

It is possible to compare these diverse museum objects habits with those evident in the late Victorian home. As Deborah Cohen, for example, has observed, eclectic ensembles of exotic objects cluttered British interiors.Footnote31 The domestic scene itself was increasingly ‘museum-like’, as conveyed in Victorian literature and its illustrations, all redolent with descriptions of ‘bric-à-brac’ worlds.Footnote32 The rise of antiques as an element of home decoration, Cohen argues, was more than simply a way to signal status; it also provided the prospect of a moral reshaping in which the secular was infused with the sacred.Footnote33 The Victorian culture of heirlooms and relics was another strand, in which things were cherished for their potential to store memories and evoke stories.Footnote34 For those of means, genuine Egyptian antiquities could be deployed in these schemas, and their popularity is evident from programme of the Burlington Fine Art Club’s 1895 Exhibition of the Art of Ancient Egypt. Out of thirty-six contributors acknowledged in the catalogue, only five were museums. The remaining donors were private individuals, many of whom were involved with the EEF as sponsors, committee members, or excavation participants. These catalogues are also a reminder of the roles of amateurs in shaping popular perceptions of collections from outside the museum.

This evocative, object-filled world, which was made immediate in the dense displays of museum galleries, contrasts strongly with the trend towards rationalising and shedding collections several decades later. A report in the May 1952 edition of the UK’s Museum Journal lamented that ‘many museums are quietly destroying or dumping large mammals, are sending back ethnological collections to their countries of origin, and are speeding up the gradual disintegration of exotic insects’.Footnote35 The scale of these disposals led the Assistant Keeper of the Ashmolean Museum’s Antiquities Department, Donald B. Harden, to speak with concern at the 1955 Museums Association conference about ‘this whole-sale discarding of what is curious and foreign from some of our museums’.Footnote36 Edinburgh’s Royal Museum on Chambers Street is one example. It had enthusiastically sought Egyptian relics, going as far as sending a junior member of staff, Edwin Ward, to excavate with Flinders Petrie between 1905 and 1907 in order to secure material.Footnote37 Yet its disposal board, which had been in existence since 1910, became especially active in the 1950s as the post-war reinstallation of the galleries offered the opportunity to reduce ‘very considerably the amount of material to be displayed’.Footnote38 The Museum transferred Egyptian artefacts to institutions in Paisley, Durham, and Sydney, while other objects were sold and a small number destroyed. Norwich Castle Museum likewise departed from museum practices that were seen as out-dated, and in 1953 its Committee resolved that the collecting policy for archaeological and ethnographic material would be ‘confined to Norfolk with the addition of Lothingland in NE Suffolk’.Footnote39 Existing material unrelated to this new locally-focused policy were to be disposed of and ‘foreign archaeological material to be drastically reduced’, including finds received from British excavations in Egypt. Similar actions took place at Bankfield Museum, Greenock’s McLean Museum and Art Gallery, Reading Museum, and Shropshire Museum Services.Footnote40

In part this change can be attributed to Britain’s shift from an expansionist imperial empire to an actively decolonising nation, encouraging more parochial museum policies and emphasising local histories above engaging with global narratives.Footnote41 This decluttering, however, was not confined to museums: there were parallel trends in British homes. Second World War rationing and post-war austerity led to a distaste for ostentatious display and a simplification in British domestic interiors. Cohen notes that from the 1930s the rising middle class were increasingly home owners, leading to new strategies of uniformity and homogenisation of taste that reduced the vast array of furnishing choices once available to affluent Victorians.Footnote42 The plate glass and tubular steel of continental European modernism became more commonplace, spreading the influence of a movement that had eschewed ornamentation and clutter. The imposition by post-War designers of open-plan interiors, devoid of parlours and mantelpieces, left little space for curios, although people found other ways to display their possessions and mementos, if not on the scale of the previous century.Footnote43 The rise of home improvement, and the rhetoric of magazines such as Ideal Home, were echoed in new Museum Association diploma guidance, which advocated that professionals should ‘clear out the clutteration of your collections and make your museums bright and cheerful!’Footnote44 Rationalisation of collections was here as much a general shift in society as it was a result of the internal dynamics of museum practice.

How museums and their publics viewed Egyptian artefacts was therefore profoundly shaped by their experiences and attitudes to things in the world within which they were immersed. That world extended from the immediacy of domestic arrangements to the international stage of global geopolitics. These shaped object habits which shifted from strongly held beliefs of the innate power of things to communicate directly in the Victorian period, towards widespread doubts as to the value and purpose of dense clutters of unprepossessing relics in the post-Second World War period.

3. Exploring alternative object habits

Our discussion above may be valid for some institutions in the UK, but the multi-sited nature of our project needs to be sensitive to object habits of other locations and alternative scales of analysis. For the Object Habit conference we solicited papers examining more complex and varied histories that would exemplify how objects and collections instantiate different sorts of knowledge as they are dispersed outward from the field; how the nature and representation of the material itself affects its historical trajectory; how the material results of fieldwork are transformed or are emergent through curatorial practices; how they may reflect or reproduce national identities and imperial ideologies; how they may or may not remain connected with or relate back to the field; and what effect shifts in contemporary interests have upon the ways people relate to objects and their institutional histories.

Each of the articles brought together here considers one or more aspects of the issues we touch upon. All papers examine the outward dispersal of artefacts and specimens primarily from sites of excavation, either from archaeological locations in Egypt (Gunning, Riggs) and the Near East (Maloigne, Robson), or from palaeontological fieldsites in Africa (Manias, Vennen and Tamborini), towards European or American museums. Relationships between the field and the museum feature in all the discussions, highlighting the contested terrain between these locales, as political (Gunning, Maloigne, Riggs, Libonati), social (Robson), and logistical (Manias, Vennen and Tamborini) factors affected the movement of objects from a fieldsite into collections and their subsequent reception. All examine the processes of knowledge construction through this trajectory, in analyses that are sensitive to broader historical factors that constrain and enable the formation of museum collections. The subjects of analysis are not limited to ancient artefacts (Gunning, Maloigne, Robson), fossils (Vennen and Tamborini), or live specimens (Libonati), but include material representations that were circulated to museums, such as photographs of Tutankhamun’s treasures (Riggs) and drawings of South African fossils (Manias). The materiality of things—including aesthetic and functional aspects—is a focus in several papers, which explore how characteristics such as size and weight (Vennen and Tamborini), decoration (Maloigne), or condition (Manias) bear upon museum collecting practices and receptions. The contingencies of material practices implicated in transporting and representing objects in and from the field also feature strongly in these accounts. This focus aligns with intellectual trends in museum anthropology that have sought to readdress the neglected role of material-institutional processes that condition access to fieldsites and the routes through which collections traverse to ‘centres of calculation’.Footnote45

The first paper, by Libonati, takes Pliny’s Naturalis Historiae as a deeper historical point of departure to develop one of the object habits that features particularly prominently in several papers in this special issue, namely that relating to the role of objects as tokens of imperial power and political ideology. Her two case studies— a Benin bronze okukor (cockerel) until recently kept in Jesus College, Cambridge, and live giraffes presented to France, Britain, and Austria by Egypt’s Muhammed Ali in 1826—stress three important aspects of object habits: the thing itself, audiences, and time. Subsequent papers variously explore, and place different emphasis on, the inter-relations and impacts of these three factors.

Tamborini and Vennen’s discussion of Berlin’s Museum für Naturkunde Tendaguru expedition (1909–1913) foregrounds the obstructive nature of the fossils and the fieldsite, which meant that the fieldwork was not incorporated into museum display until 1937. As a result the political context for the reception of the museum’s reconstruction of Brachiosaurus brancai differed markedly from that of its collection. Museum collecting here is first situated firmly within the brute facts of the real world—the friable and unwieldy fossils, the challenging terrain in which they were embedded, the problematic logistics of transport, and the physical difficulty of mounting the results in the museum. Their paper draws attention to the material culture of paleontological work as well as its discourses, allowing them to illustrate the crafting of a ‘natural history’ museum object from the field. Moreover, its transformation into a historical artefact at the point of display was contingent on imperial discourses of post-First World War German colonial revisionism, nostalgic for German colonial territories in East Africa.

Manias and Riggs both draw attention to the mechanisms of representing the material properties of objects found in the field to museum curators in the early twentieth century, through the media of drawing and photography respectively. In Manias’ review of Robert Broom’s exchanges with New York’s American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), illustrations were the means of negotiating between the needs of museum display, scientific theories, and fossils in the field. Colonial photographic practices, in Riggs’s account of Egyptological materials and Tutankhamun’s treasures, similarly fashion dispositions towards the products of fieldwork. Image records of things, Riggs emphasises, are expressly not neutral representations, an issue that is increasingly the subject of museological analysis.Footnote46 The aesthetic and technical differences among photographs; the contingencies of scheduling, lighting, and supplies; the priorities of different practitioners; and the influences of other visual practices: all these are factors that Riggs identifies as habits ripe for examination as they affect the ontological construction of archaeological and museum objects. Here too, the imperial context weighs heavily upon attitudes to things. The status of Tutankhamun’s treasures was called into question very quickly after discovery as the newly independent Egyptian government began to resist the colonial object habit of exporting finds to Europe or North America. Photographs, together with their circulation between the field and the museum, substituted for the original objects and were consequently thrust into alternative regimes of value and colonial dialogues.

The representational object habits to which Manias and Riggs draw attention not only shaped museums’ expectations and assumptions about fieldsites and their products, but in turn impacted upon how the things were perceived and emerged from the field itself. For instance, Manias notes how the disjunction between image and object led the AMNH to train Broom in excavation and instruct him in preparation techniques in the museum in order to improve his field collecting for them. Riggs draws attention to field archaeologists who recommended to museums that their in-house photography should be conducted by an archaeologist who possessed the appropriate knowledge of object requirements. Such examples underscore that there is not a simple linear trajectory from the field to the museum. Attitudes to things in one site of practice impinge upon the other.

Other papers explore how narratives are built up around and adhere to objects as they travel from findspots towards new institutional settings. Robson, for example, widens the frame of analysis for the reception of archaeological discoveries from Nimrud by considering what surrounds and informs their presentation. This approach, adopted from Jim Secord’s method of considering the whole reading experience, is especially valuable for understanding how object habits outside the museum and the field are generated.Footnote47 For instance, by looking at images of Nimrud sculptures installed in the British Museum that were juxtaposed with images of the Dickensian London Christmas experience in The Illustrated London News, Robson illuminates the means by which British archaeologists and museum-goers domesticated the site and its objects. By further analysing the reception of fieldwork at Nimrud at fifty-year intervals between the 1840s and the present day, Robson identifies lingering ‘old object habits’ that hinder the development of fresh interpretive strategies for presenting museum histories.

Maloigne’s paper focuses on the object habits that overshadowed the British Museum’s acquisition of the second millennium bce statue of King Idrimi of Alalakh discovered in 1939. She situates this history within the protracted and complex transnational diplomatic negotiations that problematised the space between the field in Turkey and the British Museum in England. Different attitudes to the statue, from its being upheld as unique to dismissal of it as unexceptional, were affected by competing political, diplomatic, and intellectual positions. With Turkey’s Hatay Archaeological Museum, opened in 2014, able only to display a holographic replica of Idrimi, the legacy of old object habits is now forcibly juxtaposed with new ones.

Similar questions concerning the cultural authority over objects feature in several articles in this special issue. Gunning provocatively raises the history of the British Museum’s 1835 agreement to acquire Egyptian antiquities through Giovanni D’Athanasi as a means to challenge assertions of the rights of encyclopaedic museums in the present. Her paper narrates how nationalistic agencies were never simply backdrops to collecting policies: they led governments to become active players in the construction of the museum, narratives that are not transparent in current public discourse. Similarly, current conflicts in the Middle East have yet to be effectively addressed in museum displays, as Robson’s paper implies, and instead the same histories of celebrated individuals, such as Agatha Christie, continue to dominate the stories museums choose to tell about their collections. Such strategies, even if unconscious and implicit, propagate colonial and imperial attitudes to collections. Riggs equally problematises the photographic archive of the Tutankhamun excavation held today in Western repositories. Unable to acquire the artefacts from the tomb as British and American museums had expected, the significance of the photographs as authoritative objects of enquiry in their own right increased. Yet the colonial-era habits around those images endure in the archive, ‘obscuring the social and material practices through which photography operated between the field and the museum.’

4. Concluding remarks

There is an identifiable trend in recent histories that seeks to avoid teleological, hagiographic, or heroic accounts of museum development and instead aims provide more penetrating, grounded, and contingent narratives. One emergent focus in this vein is the role of colonial government agencies and rationalities in shaping museum and collecting histories.Footnote48 That theme is one that several contributors in this volume also prioritise. The lived reality of collecting in the full agency of the world, however, opens up the possibility of additionally situating these histories within a host of other trends in wider society. Extending the frame of analyses of collections further, as in Robson’s use of Secord, can provide other sorts of historical juxtapositions that may provide insights into how attitudes to objects form.

The potential of the object habit is not merely that it can encourage museum histories of greater texture and insight; it may also facilitate the integration of those histories into contemporary debates. The post-Second World War change in attitude to foreign objects in UK museums discussed above, for instance, has never been more prescient. Given Britain’s current climate of economic austerity, now compounded by Brexit, parochial attitudes to transnational acquisitions are once more strongly evident, exerting greater external pressures on the integrity of museum collections acquired in previous centuries. The widely condemned sale of the ancient Egyptian statue of Sekhemkha by Northampton Borough Council in 2014, where it had resided in the local museum since the late nineteenth century, is a case in point. The Council committed the rare monument to Christie’s auction block where it was sold to a private buyer for an exorbitant price. Egypt expressed outrage, as did many British cultural organisations. Northampton Museum was stripped of its professional accreditation as a result and although a temporary export bar was placed on the antiquity by the British Government, it was eventually shipped abroad and has disappeared from public view. The borough’s councillors claimed that the object was irrelevant to local communities, but social histories that demonstrate how entangled Egyptian things are with such towns would argue otherwise.Footnote49 The incident throws into relief a long-standing tension between two competing object habits; one cultural, the other commercial. These habits exert their influence and rationales from far beyond museums, revealing modernity’s unsettled attitudes to objects. Such customs are often so deeply embedded within the fabric of society that they can prove challenging to reconcile.

Finally, it is precisely because these histories connect the field with the museum that contemporary actions in one space can have consequences in the other. The sale of objects from museums, for instance, may fuel powerful market forces that incentivise illicit digging in source countries. Similarly, conflict, and environmental degradation all directly impact the integrity of fieldsites around the world. These conditions place greater responsibility on the stewards of collections to reveal the multi-layered, ongoing histories behind things from those places in ways that meaningfully connect past, present, and future. To do so entails ethical management of these collections and a critical awareness of the diversity of object habits that are brought to bear upon them. The challenge for museums is how to make these histories not only transparent, but also accountable.

Acknowledgements

We are enormously grateful to the Museum History Journal editorial board, particularly to Kate Hill and Jeffrey Abt, for their guidance and advice during the assembly and production of this issue.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributors

Alice Stevenson is senior lecturer in Museum Studies at University College London and co-PI on the AHRC project ‘Artefacts of Excavation: The international distribution of finds from British excavations in Egypt, 1880–1980’.

Emma Libonati is research associate on the project.

John Baines is professor of egyptology emeritus at the University of Oxford and co-PI on the project.

ORCID

Alice Stevenson http://orcid.org/0000-0002-6118-6086

Emma Libonati http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9908-7024

John Baines http://orcid.org/0000-0003-4543-9909

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Samuel J. M. M. Alberti, Nature and Culture, Objects Disciplines and the Manchester Museum (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), p. 1.

2. Summarised in Dan Hicks, ‘The Material-Cultural Turn: Event and Effect,’ in The Oxford Handbook of Material Culture Studies, ed. by Dan Hicks and Mary C. Beaudry (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 25–97.

3. Chris Gosden and Yvonne Marshall, ‘The Cultural Biography of Objects,’ World Archaeology, 31(2) (1999), 169–78; Jody Joy, ‘Reinvigorating Object Biography: Reproducing the Drama of Object Lives,’ World Archaeology, 41(4) (2009), 540–56; Ivor Kopytoff, ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process,’ in The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. by Arjun Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 64–91; Kate Hill, ed., Museums and Biographies: Stories, Objects, Identities (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012).

4. Chris Gosden and Frances Larson, Knowing Things: Exploring the Collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum 1884–1945 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007); Frances Larson, Alison Petch and David Zeitlyn, ‘Social Networks and the Creation of the Pitt Rivers Museum,’ Journal of Material Culture, 12(3) (2007), 211–39.

5. Bruno Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005).

6. Rodney Harrison, ‘Reassembling Ethnographic Museum Collections,’ in Reassembling the Collection: Ethnographic Museums and Indigenous Agency, ed. by Rodney Harrison, Sarah Byrne and Anne Clarke (Santa Fe: SAR Press, 2013), pp. 3–35.

7. Flora E. S. Kaplan, ed., Museums and the Making of Ourselves: The Role of Objects in National Identity (London and New York: Leicester University Press, 1996).

8. See for example Tony Bennett, The Birth of the Museum: History, Theory, Politics (London: Routledge, 1995); Annie Coombes, ‘Museums and the Formation of National and Cultural Identities,’ Oxford Art Journal, 11(2) (1988), 57–68; Kevin Hetherington, ‘Foucault and the Museum,’ in The International Handbook of Museum Studies 1: Museum Theory, ed. by Annie Witcomb and Kevin Message (Chichester: Wylie Blackwell, 2015), pp. 21–40; Eilean Hooper-Greenhill, Museums and the Shaping of Knowledge (London: Routledge, 1992); Susan M. Pearce, Museums, Objects and Collections: A Cultural Study (Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1992).

9. John M. MacKenzie, Museums and Empire. Natural History, Human Cultures and Colonial Identities (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), p. 8.

10. Anthony Shelton, ‘Museum Ethnography: An Imperial Science,’ in Cultural Encounters: Encountering Otherness, ed. by Elizabeth Hallam and Brian Street (London: Routledge, 2000), p. 186.

11. Kaplan, Museums and the Making of Ourselves, p. 3.

12. Glenn Penny, Objects of Culture: Ethnology and Ethnographic Museums in Imperial Germany (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001).

13. Lorraine Daston, ‘Introduction: The Coming into Being of Scientific Objects,’ in Biographies of Scientific Objects, ed. by Lorraine Daston (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999), pp. 1–14.

14. Gosden and Larson.

15. Chris Gosden and Chantal Knowles, Collecting Colonialism: Material Culture and Colonial Change (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001), pp. 4–5.

16. Stephen Conn, Museums and American Intellectual Life, 1876–1926 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

17. Ramsay MacMullen, ‘The Epigraphic Habit in the Roman World,’ American Journal of Philology, 103(2) (1982), 233–46.

18. Egypt Exploration Fund, Report of the Fifth Annual General Meeting (London: Egypt Exploration Fund, 1887), p. 15.

19. Letter from Laurence N. W. Flanagan, Curator Ulster Museum, to H. W. Fairman, Professor of Egyptology, 27 June1963, University of Liverpool Garstang Museum archives.

20. Alice Stevenson, ‘Artefacts of Excavation: The Collection and Distribution of Egyptian Finds to Museums, 1880–1915,’ Journal of the History of Collections, 26(1) (2014), 89–102.

21. The exact number of destinations is revised progressively as institutions review their collections, identify errors, or confirm transmission to new locations.

22. Alice Stevenson, Emma Libonati and Alice Williams, ‘“A Selection of Minor Antiquities”: A Multi-Sited View on Collections from Excavations in Egypt,’ World Archaeology, 48(2) (2016), 282–95.

23. Elliot Colla, Conflicted Antiquities: Egyptology, Egyptomania, Egyptian Modernity (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2007).

24. Debbie Challis, From the Harpy Tomb to the Wonders of Ephesus: British Archaeologists in the Ottoman Empire 1840–1880 (London: Duckworth, 2008); Stephanie Moser, Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum (London and Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2006).

25. Anita Henare, Museums, Anthropology and Imperial Exchange (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006).

26. David Gange, Dialogues with the Dead: Egyptology in British Culture and Religion (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013).

27. Anon, ‘A Sunday-School Teachers’ Museum,’ Quiver, 28(301) (1893), 403.

28. J. G. Kitchin, Scripture Teaching, Illustrated by Models and Objects (London: Church of England Sunday School Institute, 1893), p. 3.

29. Caroline J. Tully, ‘Walk Like an Egyptian: Egypt as Authority in Aleister Crowley's Reception of the Book of Law,’ The Pomegranate: International Journal of Pagan Studies, 12(1) (2010), 20–47.

30. Martin Lawn, ‘A Pedagogy for the Public: The Place of Objects, Observation, Mechanical Production and Cupboards,’ Revista Linhas, 14(26) (2013), 244–64.

31. Deborah Cohen, Household Gods: The British and their Possessions (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2006).

32. Jonathon Shears and Jen Harrison, eds., Literary Bric-à-Brac and the Victorians: From Commodities to Oddities (London and New York: Routledge, 2013); Nicholas Daly, ‘The Obscure Object of Desire: Victorian Commodity Culture and Fictions of the Mummy,’ NOVEL: A Forum on Fiction, 28(1) (1994), 33.

33. Cohen, Household Gods, p. 13.

34. Deborah Lutz, Relics of Death in Victorian Literature and Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015).

35. David E. Owen, ‘The Changing Outlook,’ Museums Journal, 52(5) (1952), 51–53 (p. 53).

36. Donald B. Harden, ‘The Cult of the Known,’ Museums Journal, 55 (1955), 155.

37. Anon, ‘Royal Scottish Museum,’ Museums Journal, 6 (1906), 154–5.

38. Chantal Knowles, ‘Negative Space: Tracing Absent Images in the National Museums Scotland's Collections,’ in Uncertain Images: Museums and the Work of Photographs, ed. by Elizabeth Edwards and Sigrie Lien (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), pp. 73–91 (p. 76).

39. Museum Committee Minutes, January 1953 [folio 178], Norwich Record Office. With thanks to Faye Kalloniatis for drawing attention to this document.

40. Alice Stevenson, Scattered Finds: Archaeology, Egyptology and Museums (London: UCL Press, in preparation).

41. Chris Wingfield, ‘From Greater Britain to Little England: The Pitt Rivers Museum, the Museum of English Life, and Their Six Degrees of Separation,’ Museum History Journal, 4(2) (2011), 245–66.

42. Cohen, Household Gods, pp. 170–201.

43. Judy Attfield, ‘Bringing Modernity Home: Open Plan in the British Domestic Interior,’ in At Home: An Anthropology of Domestic Space, ed. by Irene Cieraad (New York: Syracuse University Press, 1999), pp. 73–82.

44. P. Storer Peberdy, Museums Journal, 55 (1955), 156.

45. See for example Tony Bennett, ‘Liberal Government and the Practical History of Anthropology,’ History and Anthropology, 25(2) (2014), 150–70 (p. 153).

46. Elizabeth Edwards, Raw Histories: Photography, Anthropology, and Museums (Oxford: Berg, 2001).

47. Jim Secord, Visions of Science: Books and Readers at the Dawn of the Victorian Age (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014).

48. Tony Bennett, Fiona Cameron, Néila Dias, Ben Dibley, Rodney Harrision, Ira Jacknis, and Conal McCarthy, Collecting, Ordering, Governing: Anthropology, Museums, and Liberal Government (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017).

49. Stephen Quirke and Alice Stevenson, ‘The Sekhemka Sale and Other Threats to Antiquities,’ British Archaeology, 145 (2015), 30–34.