ABSTRACT

This paper looks at an aspect of the ‘object habit’ by considering the motivations behind an ancient technical text, Pliny the Elder’s Natural History. The text is an ‘encyclopaedia’ of knowledge covering a vast range of subjects and approaches by studying objects including things found in nature and worked by man. For Pliny, these phenomena shared enough to be considered together while presenting an inventory of the resources in the Roman world and thus controlled by the emperor Titus (AD 79–81), to whom the work is addressed. The collection of knowledge for Pliny is a political act. The Natural History’s collapse of distinctions between objects, animate or inanimate, worked by man or in a natural state, as well as its insistence on political motivations for collecting objects and knowledge, serve as starting place for considering the ‘object habit’ and the impact of politics on collecting. Two examples are discussed: a Benin ‘bronze’ at a Cambridge college, and three giraffes gifted to the superpowers of nineteenth-century Europe.

The term ‘object habit’ describes the phenomenon and associated practices of collecting objects for social, cultural or historical reasons, allowing the object itself to remain fixed, but for the meanings, receptions and relationships of that object for audience(s) to shift over time and space.Footnote1 The term allows for discussion of issues relevant to the collection of and attitudes towards objects in a holistic manner across disciplines. Although contemporary theorists who contribute to ‘object studies’ are well known and their ideas are used in many disciplines, certain classical antecedents that also dealt with objects were equally influential in the concept of the ‘object habit’.

Over the past two decades classical scholars have become increasingly interested in critically examining ancient technical texts. In particular, they have been reassessing the usefulness of Pliny the Elder’s contribution and the subsequent receptions of his Naturalis Historiae (hereafter referred to as Natural History), a 37 book compendium covering astronomy, geography, ethnography, anthropology, human physiology, zoology, botany, agriculture, horticulture, medicine, pharmacology, mining, mineralogy, sculpture, painting, and precious stones. It is a study in objects found in the natural world including things found in nature and worked by humans, but the text does not differentiate between Praxiteles’ Apollo Sauroktonos,Footnote2 an Egyptian centaur preserved in honey,Footnote3 or a certain type of magpie.Footnote4 Pliny’s universalist approach to objects, documenting both the banal and the fantastical (mirabilia), is necessary to the ideological goals of the text: what is known is entirely dependent on Roman power and control over the physical world.

This paper discusses the influence the Natural History had on the conception of the term ‘object habit’, namely, an attitude towards collecting and collating objects and the reception of those objects as markers of imperial power and political influence. The term will then be discussed more fully through analysis of two examples: a Benin ‘bronze’ at a Cambridge college, and three giraffes gifted to the superpowers of nineteenth-century Europe.

1. Pliny the Elder’s encyclopaedia: a compiler of objects

Pliny the Elder (AD 23/24–August 25 AD 79) was a wealthy and well-connected man of the equestrian class who served as an officer in the Roman military and a procurator (provincial treasury officer) before returning to Italy as an advisor to the emperor and a fleet commander in the Bay of Naples.Footnote5 Encyclopaedias, despite the term’s derivation from Greek enkyklios paideia, were a Roman invention and endeavour, the first of them being written by M. Terentius Varro in the first century BC. But Varro’s Disciplinae and the later Artes of A. Cornelius Celsus are didactic manuals, whereas the Natural History differs as an inquiry into nature.Footnote6 Pliny’s compilation is the result of a prodigious work ethic and complex multi-tasking, with the help of slaves who simultaneously read to him and copied for him material that was included in the work. Thus the Natural History is not the result of direct scientific observation but the work of an armchair intellectual who compiles material and is ignorant of or uninterested in the original author’s intent.Footnote7 Pliny borrowed heavily from the works of Aristotle (including his taxonomies) and Theophrastus, despite his stated scepticism about theorising Greeks.Footnote8 It is a text that reveals more about Roman ideology than empirical knowledge; the text itself is a cultural artefact, and should be considered more literary than scientific.Footnote9

It is, however, a book with a purpose, which is to show the breadth and strength of the material resources of Emperor Titus and, by extension, Rome. Pliny’s work is both an act of conquestFootnote10 that serves as a model for how to demonstrate (in this case Roman) superiority and imperialismFootnote11 and a system for marshalling and classifying things.Footnote12 The text’s character as an inventory collates and collects objects from the periphery of the Empire to bring to the centre and be controlled by Rome. Pliny’s attention towards objects, such as an obelisk transported to Rome, illustrates the mastery of Roman engineering and transportation, as well as control over Egypt.Footnote13 Pliny’s imperial emphasis is mirrored in the ideology of the State. The Temple of PeaceFootnote14 was a building funded by the spoils of the Jewish War and publically displayed objects plundered from Greece, Egypt, and Asia Minor.Footnote15 The dedication of the Natural History to Emperor Titus was not just a nod to patronage or a politically convenient gesture for the author but recognition of the emperor’s status as the arbitrator of knowledge: emperors collected, controlled, and decided what was and was not true.Footnote16

The Natural History survived as a whole—whereas only sections of other similar works are extant—because its taxonomies and comprehensive subject matter continued in popularity throughout the Middle Ages and Renaissance as an authority,Footnote17 retaining its status as an examplar for other similar works into the eighteenth century.Footnote18 Eva Schulz’s study of museological treatises of the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries shows that the universal approach to cataloguing found in Pliny was so embedded as a system for ordering objects that its underlying architecture remained in place as collecting shifted from focusing on acquisition to serving as a basis of knowledge production and sharing.Footnote19 Likewise the sixteenth-century Kunst and Wunderkammen also embraced a universal approach to the collecting and display of objects,Footnote20 before more subject specific collecting habits emerged in the seventeenth century.Footnote21 In the age of scientific observation, when there was a realisation that some of the assertions in the Natural History were hokum, the text was still used as the control against which direct observation could be tested.Footnote22 In the nineteenth century, scholarly circles may have disavowed Pliny as fanciful,Footnote23 but he was also portrayed as an empiricist and observer of natural phenomena, while the romantic image of Pliny and the eruption of Vesuvius was the subject of numerous paintings.Footnote24 Ironically, considering the criticism his work would later receive, he died during the eruption in AD 79 because he wanted to observe the event from as close as possible.Footnote25

The Natural History’s endurance and influence as a scientific text and its ideological treatment of objects as markers of Empire—whether they were masterpieces of Greek sculpture or a camelopard (giraffe)Footnote26—resonated with themes this issue of Museum History Journal is exploring about the development of field-collecting across disciplines and the perception of objects as zeitgeists changed. Likewise, the text’s treatment of all items as ‘objects’, whether occurring in nature or worked out of something that occurs in nature, allows for a natural specimen and an archaeological artefact to be considered within the same category and in a multi-disciplinary manner.Footnote27 This attitude towards objects without distinction between something that is made and something that exists has resonances with modern object theorists, such as Martin Heidegger and Walter Benjamin, whose work informed the development of the concept of the ‘object habit’.

2. The object habit: a very human problem

The object habit has three important aspects: foremost, the ‘object’ itself; second, the audience;Footnote28 and third, time. The thinking behind the term was inspired by the ‘epigraphic habit’, a concept developed by Ramsay MacMullen that explains the increase in inscriptions in the first and second centuries AD and expands an inscription’s relevance beyond the content of the letters carved on the stone to seeing such objects as the products of negotiation between maker, patron, and audience(s), indicative of larger socio-cultural trends.Footnote29 Inscriptions have the ability ‘to speak’ to those questions, whereas not all objects can tell us why they were commissioned and created, or what they were intended for. Inscriptions also come from a specific time, were displayed in specific places, and were crafted in a similar ways, whereas an ‘object habit’ needed to consider attitudes that could be applied to all types of objects and were created or existed in a wide variety of times.

The object habit goes further, using the precedent of the Natural History to collapse distinctions between types of objects; and by ignoring whether the item was made (a statue) or exists in its natural state (an orchid or a skeleton of a gorilla) the approach can consider objects from different categories as part of collecting practice. However, the object remains static, its thingness in a fixed state, even though the kind of object it is can be changed by how it is regarded.Footnote30 The object habit looks at the social-cultural relationships and constructions that are imposed and inscribed upon an ‘object’ by an audience and that transform over time—whether it is a posy of flowers, a dodo specimen, or the statue of David with or without a fig-leaf in the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The audience shifts constantly. It is always human, but objects do not need a physical human presence to have meaning, especially since they are sometimes created for an imagined audience that is intended to project meaning onto them.Footnote31 For instance, grave goods are necessarily objects because they are culturally constructed as useful for the deceased’s afterlife and might serve as status-markers as an indication of their societal place both in their current and afterlife.Footnote32 The intended audience in the afterlife can only conform to the system that created the objects, not to the myriad of other audiences that might exist.Footnote33 Jonathan Meades pointedly expresses the primacy of the object and the subjectivity of the audience in his film on objects and architecture produced in Mussolini’s fascist Italy:

inanimate objects do not contain the spirit of the doctrine or gods or saints they are associated with. There is no such thing as spirit, save in the mind of the deluded. And the attribution to inanimate objects of humours or moral qualities is half-witted, yet it is apparently an irresistible human urge.Footnote34

For Meades, objects are composed of materials, not imbued with a political ideology. Audiences create categories, curate, and order objects; they inscribe meaning.

Time is the third analytical component in the object habit because it acknowledges that the meaning of an object can change or be redeployed during its existence as an ‘object’ while also acknowledging that it can have multiple and divergent vectors of meaning at the same time, in the same place, and with the same set of determining factors in relation to an audience. Since an audience constructs meaning, an object such as a broken pot can end up in the dump in one time period but in another time be fetishised and feted in a museum vitrine, and then at another point, lie in the back of a museum cupboard, and again at yet another time be deaccessioned or circulated to another institution or subject.Footnote35 Time takes into account the reception of an object as long as it exists as matter, but allows for more vectors of reception than Walter Benjamin’s ‘has-been’ and ‘not yet’ while keeping his emphasis on the historical.Footnote36 In this way, the life of an object and its continued reception over time allow for oscillations and slippages of meaning and importance, acknowledging that the ‘object’ may be static in itself but its audience reception(s) may not be.

3. Attitudes to Empire: an okukor in a Cambridge college

The Natural History’s interest in objects for ideological and imperial purposes resonated with one aspect of the ‘object habit’ concerning collecting practices from the eighteenth century to the present. An example of such an object is the Benin ‘bronze’ okukor (cockerel) most recently located in the hall at Jesus College, University of Cambridge. The intricate brass sculpture was made in Benin (modern-day Nigeria) from metal brought to the kingdom by European traders in the form of manillas or metal bracelets (so originally the object was created from other objects) to exchange as currency for commodities including ivory and for slaves.Footnote37 The okukor was created as a decoration for the ancestral altar for a queen mother, a reference to her honorific title ‘the cock that crows at the heart of the harem’ and her role organising and controlling the royal harem.Footnote38 Already at the point of its creation there was a rich narrative of which the object formed a part, including the history and legacy of African empire-building in West Africa, trade and European state formation in the early modern period, and power-structures among women in West Africa, amongst just a few examples in which this object existed in the political, cultural, and symbolic system of the Kingdom of Benin. In the okukor’s display life in the kingdom, the Oba (king), the queen mother, a woman of the harem, and a palace servant might have different receptions of such an object.

In 1897, the okukor came to England as a result of the Benin Punitive Expedition. Earlier in the year, the ruler, the Oba Ovanramwen had tried to postpone a trade meeting because he was occupied with an important state ceremony that honoured the ancestors. The just-arrived Acting Council General nevertheless continued towards Benin City, clearly holding the opinion that Britannia’s needs were more important, and was ambushed on the road. As a result, seven of the nine Englishmen were killed, along with most of the 200 Africans travelling with them.Footnote39 As punishment the British annihilated the kingdom, killed thousands, set the city on fire, and looted the palace, with participating individuals being permitted to keep booty for themselves, while the British Foreign Office was allowed to sell off the objects.Footnote40

The reception of the Benin ‘bronzes’ is more complex in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century because it is conditional on the legitimacy of the colonial narrative being upheld, and the dissemination of the massacre and the objects by popular, scientific, archaeological and ethnographic publications. Annie Coombes argued that these widely circulated photographs and narratives in British publications impacted on later receptions and displays of the material culture from Benin.Footnote41 The British portrayed the people as ‘savages’ but had to acknowledge the intricacy and technical skill of the objects the Benin produced as artistically worthy of display in museums. This disjunction between the actual object and a narrative that the political authority wants to project to a public audience impacts on the display in the museum. British ethnographers resolved the incompatibility between their view of the Benin and of the objects by suggesting the ‘bronzes’ were not made by the Benin,Footnote42 but others took a different view. The German ethnographer Felix von Luschan, acting on behalf of the Berlin Museum of Ethnography, acquired 580 objects from the Foreign Office auction.Footnote43 While Augustus Pitt-Rivers arranged the Benin material in the Pitt Rivers Museum ‘chronologically’, with what he viewed as the most technologically and culturally sophisticated as the latest items so as to impose an evolution onto the objects,Footnote44 von Luschan organised objects geographically to allow for independent empirical observations across all cultures.Footnote45 Unlike his British ethnographer contemporaries, von Luschan published and thought of the bronzes as art work, especially in his 1919 book Die Altertümer von Benin where he compared the bronzes to Renaissance masterworks in bronze like Cellini’s Perseus with the Head of Medusa (1554), paving the way for later receptions of the material as fine art.Footnote46 The differences between the British and German responses to the same objects at the same time show just how much circumstances impact on presentation and reception of objects in museum contexts. British ethnographic museums, such as the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford or the Horniman Museum in London, bought material from Benin, demonstrating that non-Western objects collected by expeditions that were military, zoological, ethnographic, or paleontological in purpose impacted on both the institutions these objects were allowed to be part of and the categories to which such objects were assigned.

The okukor was given to Jesus College by George William Neville,Footnote47 a member of the British force whose son attended the college in the 1930s, as a tribute to the cockerel on the college crest. It is likely that other agendas were intended, including celebration of British military superiority and imperialism. The original meaning and the cultural contexts for which the okukor was created as an object for an audience were completely written over, and it was received more as a mascot for a college in an elite British university rather than a commemorative artefact with historical and cultural significance. This rupture in what the object means to two different audiences and their understanding of the status of the object is integral to the object habit: the integrity of the object remains but other meanings are foisted upon it by audiences from different cultures at different moments in time.

The two dominant historical and cultural narratives that can be attached to the okukor lay dormant until 2016, when the sculpture was recognised as being displayed in a space not intended by the culture which made it as a commemoration of an ancestor. This ignited new competing political narratives for the object focusing on the colonial legacy and the repatriation of objects, and these sparked international press coverage and predictable opposing opinions.Footnote48 Since the early 1980s Nigeria had been making forceful arguments for the restitution of Benin objects held in major institutions like the British Museum.Footnote49 For a certain section of the audience the okukor became a marker for colonialism and the brutal tactics employed by the British, for others these were objects acquired under the British Empire and should not be viewed as ‘objects of apology’ to be repatriated to their home countries, whereas for others the narrative focused on the Cambridge students, rebuking them for their sensitive millennial views. The okukor will likely be returned to Nigeria but not to its original context and function as a commemorative statue, instead to a museum and another set of audiences.

4. Animals as objects: a wonderment and a diplomatic gesture

Less conventional items that were also treated as objects, both in the Natural History and in the history of collecting, are live animals. The collecting of live animalsFootnote50 has a historical precedent and is cross-cultural, with animals exchanged as tribute and gifts, collected in menageries, and used as spectacles in China, Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Rome, and South America, in a practice that continues to the present day (e.g. panda diplomacy).Footnote51 The designation of live animals as objects presents a quandary: unlike other objects, which are either manufactured or are from nature, an animal has a moment when its state changes from alive to dead. As a live object it is displayed in a private collection or in a public zoological park, while as a dead object it can be stuffed and mounted as an exhibit, perhaps changed into another object like a purse or a rug, or it can simply be discarded because its purpose was only to exist in life, so that it has no further use-value and is designated as ephemeral.

The long tradition of giving animals as tribute, including animals that have intrinsic value as food, is documented in artwork as a standard trope for power and domination.Footnote52 However, an animal that cannot be eaten and is only valuable because it is a spectacle is a different thing when it appears, particularly when it is in public, as a pure signifier of political power. One of the first recorded exchanges of exotic animals involved Tiglath-Pileser I, the Assyrian king ca. 1100 BC, who was presented with a crocodile and a female ape possibly from Egypt.Footnote53 But one animal, the giraffe,Footnote54 seems to have a long legacy of being a prestige diplomatic gift and as such an object that reflected cultural and political power.Footnote55

Giraffes were recorded as tribute in ancient Egyptian tomb and temple decoration, but the first public display of the live animal recorded in a text was in the Grand Procession of Ptolemy II in 275 BC, as a sign of the scope of power the king possessed.Footnote56 The animals chosen ranged from elephants—a prized military weapon—to a wide variety of African and European exotic animals, demonstrating the ruler’s tremendous resources and reach.Footnote57 The giraffe’s first attested appearance in Europe was in Julius Caesar’s triumphal display after the conquest of Egypt, a choice that must have been inspired by the animal’s previous appearance in the Ptolemaic procession.Footnote58 Following the precedent of rulers of Rome, a menagerie was an essential marker of power for medieval and early modern European rulers, and exotic animals such as lions, elephants, and rhinoceroses were a currency exchanged among monarchs for their private menageries.Footnote59 Although lacking in utility, the extraordinary appearance of the giraffe and its relative docility meant that it became a prime prestige diplomatic gift. Documented exchanges of giraffes from rulers of Egypt include one in the eleventh century, when the Byzantine emperor Constantinus IX received one for his menagerie and displayed it in the theatre.Footnote60 In the thirteenth century, the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II acquired one for his Palermo zoo.Footnote61 Further east, one was sent in 1404 to Tamerlane at Samarkand, and another a decade later to the imperial court in China.Footnote62 Particularly notable were Lorenzo de’ Medici’s negotiations in 1486 with the Sultan of Egypt and his broken promise to make a gift of the exotic animal to Anne de Beaujeu, the daughter of Louis XI of France, once the animal’s reception as a prestige item had been exhausted in Florence.Footnote63 The unusual animal is suitable as a prestige object across cultures and periods; its inherent qualities as an object do not change, and audiences always received it favourably.

An example of how the giraffe acts as an object is the 1826 gifting of three giraffes by Egypt’s not very popular pasha, Muhammad Ali, to King George IV (1762–1830) in Britain, King Charles X (1757–1836) in France, and Emperor Franz II (1768–1835) in Austria: the rulers of the three most powerful nations in western Europe. The gifts were intended to pacify European nations as the Ottoman Empire was attempting to stifle a Greek uprising.Footnote64 Two of the Sudanese giraffes were captured together, and the British and French consuls Henry Salt and Bernardino Drovetti, rival procurers of artefacts for national collections, had to choose between them. The giraffes not only became objects of celebrity for a short period but they also inspired giraffomania in Europe: a plethora of objects was created in homage to the extraordinary creatures, and the animals inspired operettas, festivals, fashionable colours and hairstyles, pastries, songs, skits, and turns of phrase.Footnote65 The era of mass-production and print replication allowed for the dissemination of the giraffe as a fashionable object, to circulate freely, to be replicated, and to be alluded to.

The English and Viennese giraffes did not survive for long, and their usefulness for the ‘object habit’ is limited because it is not possible to measure audience reception over time. The Viennese giraffe, having been seriously injured on its journey over the Alps, lived for only eight months. George IV kept the English giraffe in seclusion at Windsor in the menagerie which he had developed into the largest in the country after his ascent to the throne.Footnote66 Although the giraffe lived only two more years, it was the subject of political cartoons that mocked the reclusive king and his mistress: sometimes its exotic figure was depicted as a replacement for the king, while ‘scientific’ studies concluded that the giraffe’s tongue was black to protect it from sunburn and that it preferred licking the hand of a lady to that of a gentleman.Footnote67 Simultaneously, there were multiple receptions of the giraffe by different audiences, from the irreverent to the serious.

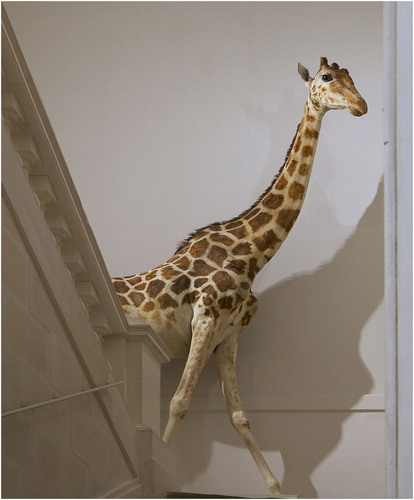

The French giraffe (see ) was transformed into an even greater celebrity through being displayed conspicuously. After landing in Marseilles she walked the 880 kilometres to Paris, with crowds of people lining the road to see the spectacle of her,Footnote68 sometimes clad in a special made coat bearing the French royal fleur de lys on one side and the arms of Muhammad Ali on the other,Footnote69 thereby signifying exactly her purpose as a diplomatic object. In July and August of 1827, 100,000 people, an eighth of the population of Paris, visited the Jardin du Roi to see the giraffe.Footnote70 Three years later Balzac would write: ‘the giraffe is no longer visited except by the backward provincial, the idle nanny and the simple and naive conscript.’Footnote71 The novelty of its existence had been displaced by the arrival of the Native American Osage delegates from Louisiana, who were similarly used as a spectacle, a reminder that emerging imperialist powers could treat humans as objects in the same way. The French giraffe lived for more than 17 years in relative obscurity in the menagerie, no less a wondrous creature and still an absolute rarity, just no longer of intense interest to a wider audience.

Figure 1. The French giraffe in a stairwell in the Muséum d’histoire naturelle de La Rochelle. Creative Commons public domain licence CC0 1.0.

The French giraffe exemplifies how an ‘object habit’ can be transformed by a fickle audience and fashionable preferences. The object can have a pointed political message attached to a gift exchange that is erased over time as politics and culture change. By the death of the French giraffe in 1845, Charles X had died in exile, there was a new citizen-king Louis-Philippe, and France was a few years off establishing a Second Republic. All three animals were redeployed as specimens, they were dissected, their hides were taxidermied, and their skeletons were cleaned and articulated. In the transformation from live curiosities to dead ones, the giraffes were both scientific objects and objects of spectacle, changing in significance to audiences, as giraffes became more prevalent in zoological collections that were publically accessible. The Viennese giraffe’s skeleton was housed in the College of Veterinary Medicine and its stuffed hide displayed as a specimen in the Natural History Museum in Vienna. The British giraffe was similarly prepared, with an emphasis on anatomical dissection, and both the skeleton and the hide, rearticulated over a wooden frame, stayed at the London zoo as examples of the species. These objects are now lost, not significant enough to be valued or kept because of their historic importance. The French giraffe was dissected into constituent parts, with her soft organs removed for preservation in formaldehyde, her skeleton donated to the Faculty of Sciences at the University of Caen, and her taxidermied skin displayed in the foyer of the museum of her former home, the now newly renamed Jardin des Plantes. Whereas the giraffe’s skeleton was incinerated in a bombing in World War II, her skin still exists tucked in a stairwell at La Rochelle’s Natural History Museum, having been transferred from Verdun.Footnote72 Although the history of the French giraffe had been forgotten for many decades, a resurgence of interest has come from popular books and an animation loosely based on the story. Audiences are more likely to be interested in her importance in national cultural history than as an example of a giraffe specimen.

5. Conclusions

By using Pliny the Elder’s Natural History as an example of ancient technical thinking about objects, I have proposed a way to approach a broader philosophical basis and definition of the ‘object habit’ that collapses divisions between items worked and unworked, animated and unanimated. I only considered one aspect of an ‘object habit’, by concentrating on objects that were collected for a political agenda and discussing the changes that audience(s) and time impose upon an ‘object’ as political, cultural, and social systems and attitudes change, or as it is brought from the culture of the place where it was legible in a certain system to an entirely different one. The ‘object habit’ allows for a history, a prolonged ‘object biography’, where the afterlife(s) of the object and the reasons and receptions of its collection are equally important to its story.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes on contributor

Emma Libonati is the Research Associate on the Artefacts of Excavation Project. She is interested in the material culture of the Hellenistic and Roman Near East, in particular stone sculpture and its manufacture, the dissemination of Egyptian religion throughout the Mediterranean, and the history of archaeology. Her doctorate is on the stone and large-scale bronze sculptures recovered from the underwater excavations in Aboukir Bay in Egypt. She has been a postdoctoral fellow at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles, and a research assistant at King's College London on the digital resource The Art of Making in Antiquity: Stoneworking in the Roman World.

ORCID

Emma Libonati http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9908-7024

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. My thanks to John Baines and Alice Stevenson and to the editors of Museum History Journal for reading and commenting on earlier drafts of this paper.

2. Pliny, Natural History, 34.70. Pliny the Elder, Natural History, trans. by Harris Rackham (London: William Heinemann, 1983–1995).

3. Pliny, Natural History, 7.35.

4. Pliny, Natural History, 10.118.

5. See R. Syme, ‘Pliny the Procurator,’ Harvard Studies in Classical Philology 73 (1969), 201–36.

6. M. Beagon, Roman Nature: The Thought of Pliny the Elder (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1992), pp. 130–1, points out that the overarching theme of Nature in the Natural History owes a debt to Aristotle.

7. R. French, Ancient Natural History: Histories of Nature (London; New York: Routledge, 1994), pp. 218–22.

8. Beagon, Roman Nature, pp. 18–22.

9. G. E. R. Lloyd, Science, Folklore and Ideology: Studies in the Life Sciences in Ancient Greece (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), p. 136.

10. S. Carey, Pliny's Catalogue of Culture: Art and Empire in the Natural History (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), p. 34.

11. Carey, Pliny's Catalogue of Culture, pp. 32–40.

12. C. Lévi-Strauss, The Savage Mind/[La pensée sauvage] (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1966). M. Foucault, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (London: Tavistock Publications, 1970).

13. Pliny, Natural History, 34.14–15.

14. Pliny, Natural History, 36.102, considered the building to be one of the three most beautiful in Rome.

15. Pliny, Natural History, 12.94; 34.84; 35.102,109; 36.27, 58.

16. T. Murphy, Pliny The Elder's Natural History: The Empire in the Encyclopedia (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), pp. 197–201.

17. C. G. Nauert, Jr., ‘Humanists, Scientists, and Pliny: Changing Approaches to a Classical Author,’ American Historical Review, 84(1) (1979), 72–8.

18. E. Schulz, ‘Notes on the History of Collecting and of Museums: In the Light of Selected Literature of the Sixteenth to the Eighteenth Century,’ Journal of the History of Collections 2(2) (1990), 208. A. Doody, Pliny's Encyclopedia: The Reception of the Natural History (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010).

19. Schulz, ‘Notes on the History of Collecting and of Museums,’ pp. 205; 212.

20. Major collections like that of Ludovico Moscardo were divided into three broad groupings derived from the Natural History, keeping separate categories of antiquities; stones, minerals, and earth; and coral, shells, and animals. See: A. Shelton, ‘Cabinets of Transgression: Renaissance Collections and the Incorporation of the New World,’ in The Cultures of Collecting, ed. by J. Elsner and R. Cardinal (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994), p. 182.

21. See: S. Moser, Wondrous Curiosities: Ancient Egypt at the British Museum (London: University of Chicago Press, 2006), p. 12; and for general overview of early modern period collections in the West, pp. 11–32.

22. The errors of Pliny and his method were acknowledged early on, but that did not mean that the entire work was to be ignored. See A. Castiglioni, ‘The School of Ferrara and the Controversy on Pliny,’ in Science, Medicine, and History: Essays on the Evolution of Scientific Thought and Medical Practice Written in Honour of Charles Singer, ed. by E. A. Underwood (London; New York: Oxford University Press, 1953), vol. 1, pp. 269–79.

23. M. Beagon, ‘The Curious Eye of the Elder Pliny,’ in Pliny the Elder: Themes and Contexts, ed. by R. K. Gibson and R. Morello (Leiden: Brill, 2011), pp. 86–8, gives an example of a public disavowal of Pliny by a man with a taste for curiosities.

24. V. C. Gardner Coates, K. Lapatin, J. L. Seydl, The Last Days of Pompeii: Decadence, Apocalypse, Resurrection (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2012), pp. 126–7: Jacob More, 1780. Mount Vesuvius in Eruption (Edinburgh: National Gallery of Scotland NG 290).

25. Pliny the Younger, Letters 6.16.37. Pliny the Elder did try to rescue people by ordering ships when he realized the extent of the disaster.

26. Pliny, Natural History, 8.27.

27. For actor–network theory or object-oriented ontology, see B. Latour, Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor–Network-Theory (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); G. Harman, Tool-being: Heidegger and the Metaphyics of Objects (Chicago: Open Court, 2002).

28. Critical to this is the work of W. Benjamin, Illuminations, trans. by H. Zohn (London: Fontana, 1992), p. 190: ‘experience of the aura thus rests on the transposition of a response common to human relationships to the relationship between the inanimate or natural object and man … To perceive the aura of an object means to invest it with the ability to look at us in return.’

29. R. MacMullen, ‘The Epigraphic Habit in the Roman Empire,’ American Journal of Philology 103(3) (1982), 233–46; J. Ma, Statues and Cities: Honorific Portraits and Civic Identity in the Hellenistic World (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), pp. 9–10.

30. G. Harman, Heidegger Explained: From Phenomenon to Thing (Chicago and La Salle: Open Court, 2007), pp. 129–31.

31. There is no need for a human Dasein to give meaning to the object for Heidegger. Benjamin needs a collector to bring the historical object to the collector's time and place.

32. For habitus see especially P. Bourdieu, Outline of a Theory of Practice (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977).

33. P. Bourdieu, ‘The Forms of Capital,’ in Handbook of Theory and Research for the Sociology of Capital, ed. by J. G. Richardson (New York: Greenwood Press, 1986), pp. 241–58.

34. Ben Building: Mussolini, Monuments and Modernism, BBC 4 documentary, writer J. Meades, 2016.

35. See A. Stevenson, J. Baines, E. Libonati this volume for further discussion. For object-biographies see: C. Gosden and Y. Marshall, ‘The Cultural Biography of Objects,’ World Archaeology, 31(2) (1999), 169–78; I. Kopytoff, ‘The Cultural Biography of Things: Commoditization as Process,’ in The Social Life of Things. Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. by A. Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 64–91; K. Hill, ed., Museums and Biographies: Stories, Objects, Identities (Woodbridge: Boydell Press, 2012).

36. W. Benjamin, The Arcades Project, trans. H. Eiland and K. McLaughlin (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1999), N.10a,3; p.475; N7,7; p. 470.

37. K. Ezra, Royal Art of Benin: The Perls Collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1992), p. 129.

38. Ezra, Royal Art of Benin, pp. 85–6.

39. Ezra, Royal Art of Benin, p. 16.

40. A. Coombes, Reinventing Africa: Museums, Material Culture and Popular Imagination in Late Victorian and Edwardian England (London: Yale University Press, 1994), pp. 9–11.

41. Coombes, Reinventing Africa, pp. 11–22.

42. Coombes, Reinventing Africa, pp. 23–6.

43. K. W. Gunsch, ‘Art and/or Ethnographica: The Reception of Benin Works from 1897–1935,’ African Arts, 46(4) (2013), 26–7. The bronzes were bought by the Ethnographic Museum because German Fine Art Museums were restricted financially and by a collection policy that did not recognise bronze objects as art.

44. Gunsch, ‘Art and/or Ethnographica,’ 26.

45. Gunsch, ‘Art and/or Ethnographica,’ 27.

46. Gunsch, ‘Art and/or Ethnographica,’ 28–30.

47. C. Freeman, ‘Cambridge under Pressure to Return Looted Benin Bronze Cockerel – But Won't Return it in Case it Gets Stolen Again,’ The Telegraph, 8 October 2016. <http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2016/10/08/cambridge-under-pressure-to-return-looted-benin-bronze/> (accessed 16 January 2017).

48. T. Jenkins, ‘Bloody Truth about the “Colonialist” Cockerel Cambridge Students Want Sent Back to Africa: It's Made from Melted-Down Money Africans Earned by Selling Slaves,’ Daily Mail, 10 March 2016, <http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3485000/Bloody-truth-colonialist-cockerel-Cambridge-students-want-sent-Africa-s-melted-money-AFRICANS-earned-selling-slaves.html#ixzz4Uof5YhAW> (accessed 4 January 2017). J. Jones, ‘The Cambridge Cockerel is no Cecil Rhodes Statue – It Should Be Treated as a Masterpiece’, The Guardian, 22 February 2016, <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/jonathanjonesblog/2016/feb/22/cambridge-cockerel-jesus-college-cecil-rhodes-nigeria> (accessed 16 January 2017).

49. Coombes, Reinventing Africa, p. 223.

50. It is clear that taxidermied animals were not as prestigious as live ones, although bones and hides were displayed in temple complexes throughout Greece, if one is to believe Pausanias. See A. Mayor, The First Fossil Hunters: Dinosaurs, Mammoths, and Myth in Greek and Roman Times (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011), pp. 260–81.

51. The Aztecs also used animals in gift-exchange. See historical overview: R. J. Hoage, A. Roskell and J. Mansour, ‘Menageries and Zoos to 1900,’ in New Worlds, New Animals: From Menagerie to Zoological Park in the Nineteenth Century, ed. by R. J. Hoage and W. Deiss (Baltimore; London: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996), pp. 8–18.

52. The giraffe as tribute item remains consistent from the Punt reliefs in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahri in Egypt to the black obelisk of Shalmaneser III from Nimrud in Iraq. After Nubia was defeated by the Caliphate in AD 652, it had to pay an annual tribute that included a giraffe. When the Mamluks annexed Sudan to Egypt in AD 1275, the Nubians were required to send annual tribute of animals including giraffes, panthers, and elephants. See B. Laufer, The Giraffe in History and Art (Chicago: Field Museum, 1928), p. 35.

53. A. Kuhrt, The Ancient Near East: c.3000–330 B.C. (London: Routledge, 1995), vol. 1, p. 361.

54. See Laufer, The Giraffe in History and Art, pp. 15–25 for the prevalence of the giraffe in Egyptian art.

55. There are rich debates among anthropologists questioning the division between ‘gift’ and a ‘commodity’. See: M. Mauss, The Gift: the Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, trans. by W. D. Halls (London: Cohen & West, 1954); A. Appadurai, ed., The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986); A. B. Weiner, Inalienable Possessions: the Paradox of Keeping-While-Giving (Berkeley; Oxford: University of California Press, 1992); D. Miller, Material Culture and Mass Consumption (Oxford: Blackwell, 1994); M. Douglas, ‘The Genuine Article,’ in The Socialness of Things: Essays on the Socio-Semiotics of Objects, ed. by S. H. Riggins (Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter, 1994), p. 16: ‘But the distinction between gift and commodity comes under the same umbrella. The direction to which this distinction leads us is not to different kinds of objects, but to different kinds of relations between persons.’

56. 200F–201C, trans. by E. E. Rice, The Grand Procession of Ptolemy Philadelphus (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983), pp. 17–9. Some animals may not have been sourced specially for the procession since there is a suggestion of a royal menagerie. Rice, pp. 86–7.

57. See T. R. Trautmann, Elephants and Kings: An Environmental History (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

58. Pliny, Natural History, 8.27.

59. C. Grigson, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016), p. 1, notes various gifts from monarchs received by Henry III during his reign in the thirteenth century.

60. Laufer, The Giraffe in History and Art, p. 66.

61. W. Blunt, The Ark in the Park: The Zoo in the Nineteenth Century (London: Book Club Associates, 1976), p. 73.

62. S. Wilson, ‘The Emperor's Giraffe,’ Natural History (December 1992), 22–5.

63. M. Belozerskaya, The Medici Giraffe and Other Tales of Exotic Animals and Power (New York: Little, Brown, 2006), pp. 87–129.

64. Weiner 1992 (see n. 55) argued that exchange/giving should be related to politics and the production of political hierarchies.

65. M. Allin, Zarafa: A Giraffe's True Story, from Deep in Africa to the Heart of Paris (New York: Delta, 1999), pp. 175–7. In France that year's winter flu was known as ‘Giraffe flu’, while the expression ‘peigner la girafe’ (‘combing the giraffe’) alludes to doing something lazily because the crowds attended the giraffe's grooming.

66. C. Grigson, Menagerie: The History of Exotic Animals in England, 1100–1837 (Oxford: Oxford University, 2016), p. 231.

67. Grigson, Menagerie, p. 238.

68. Allin, Zarafa, pp. 144–59.

69. H. J. Sharkey, ‘La Belle Africaine: The Sudanese Giraffe Who Went to France,’ Canadian Journal of African Studies/Revue Canadienne des études Africaines, 49(1) (2015), 46.

70. Allin, Zarafa, p. 181.

71. Quoted in Blunt (p. 79), Balzac writing in La Silhouette, 17 Juin 1830: ‘la girafe n’est plus visitée que par le provincial arriéré, la bonne d’enfant désœuvrée et le jean-jean simple et naïf.’

72. Allin, Zarafa, p. 195; Sharkey, ‘La Belle Africaine,’ pp. 5–6; pp. 23–4; Grigson, Menagerie, pp. 238–9; Blunt, The Ark in the Park, p. 76.