ABSTRACT

Previous studies have examined influencing factors on community participation in tourism, however, the application of social identity theory to the study of community participation in tourism has been under-researched. This study examines the influence of social identity of migratory village residents on community participation in tourism based on a structural equation modeling approach. Deploying a survey on 364 residents in Simatai new village in China, the findings show that residents’ community identity, regional identity, and occupational identity have a significant positive impact on their attitude toward supporting tourism and community participation in tourism. Residents’ support for tourism has a mediating effect between social identity and community participation. Accordingly, it is suggested that local governments should pay more attention to the construction of the community and carry out ongoing tourism education programs for residents, which ensures their recognition and support for the community and the development of tourism, and promotes community participation in tourism.

摘要

之前的研究探讨了社区参与旅游的影响因素,但对社会认同理论在社区参与旅游研究中的应用还很缺乏。本研究基于结构方程模型方法,探讨了迁移型村落居民的社会认同和其参与旅游之间的关系。通过对中国司马台新村的364名居民进行调查,结果表明居民的社区认同、地域认同和职业认同对其支持旅游和参与旅游有显著的正向影响。此外,居民支持旅游的态度在社会认同和社区参与之间具有中介效应。因此建议地方政府应多关注社区的建设,持续开展居民旅游教育项目,确保居民对社区和旅游发展的认可和支持,促进社区参与旅游。

1. Introduction

The construction of new rural communities has accelerated over the past few years as China’s tourism industry continues to grow. This is primarily reflected in the community’s internal and external spatial patterns as well as its production and lifestyle, of which migratory villages are the most typical (Jia et al., Citation2020). As a new type of community living form, migratory villages relocate and merge existing surrounding villages based on tourism resources and build new villages by means of village relocation. The term ‘migratory villages’ has not yet been discussed, but from practical experience, the development model of ‘migratory villages’ is widely used, Simatai new village is a typical example. Academia currently uses concepts such as scenic-reliant villages (Wei et al., Citation2018) and rural tourism commoditization (Li et al., Citation2022) to describe this phenomenon, but none of them reflects the characteristics of changes in settlement space. Therefore, this paper uses the term ‘migratory villages’ to describe this phenomenon. Different from traditional villages, residents of these migratory villages generally live in scenic spots or nearby villages, and their lives, employment, and other aspects are closely related to tourism development. The development of tourism has increased residents’ income, and a large number of residents have participated in tourism services and related activities, changing their way of livelihood. The development of migratory villages has transformed from agriculture to tourism, and their dependence on tourism has increased significantly. Since the active support of local communities plays a crucial role in the successful development of tourism and in the improvement of residents’ quality of life (Boley & Strzelecka, Citation2016; Fan et al., Citation2021; Ramkissoon, Citation2023), there is a need to understand residents’ attitudes and their participation in tourism in order to facilitate the sustainable development of tourism in migratory villages (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012; Obradović & Stojanović, Citation2022; Tosun et al., Citation2021).

Compared with the original residence, the spatial layout, community settlement, and employment of residents in the migratory villages have all changed, mainly reflected in the transformation of villages from natural scattering to centralized construction, from traditional rural communities to tourism service communities, and the residents have also transformed from farmers to tourism workers (Li et al., Citation2021). In these villages, more and more rural spaces are being used for recreation and entertainment, the influx of tourists and the arrival of foreign investors has also changed the pattern of social relations in the village from ‘the pattern of difference sequence’ to ‘the pattern of pluralism’ (Li et al., Citation2021). The village has gradually evolved from a traditional ‘rural society’ based on blood ties to a tourism service-oriented community based on economic interests driven by tourism (Xi et al., Citation2014). The diversification from agriculture to tourism is a fundamental change in many ways, which has brought a huge impact on residents’ identity and local affiliation (Brandth & Haugen, Citation2011; Wang et al., Citation2021). Given that a person’s identity will affect their actions and behaviors (Hagger et al., Citation2007; Mannetti et al., Citation2004), whether the residents’ identity has a significant impact on their participation in tourism is particularly important. It is well-recognized in the field of sociology that identity plays an important role and has also been used to explain organizational behavior (Ahearne et al., Citation2005; Dutton et al., Citation1994). We propose that residents’ identity affects their attitudes toward tourism development and their behavior in participating in tourism. This is the key question that this study seeks to examine.

Numerous studies have been conducted on the factors that influence community participation in tourism (Wondirad & Ewnetu, Citation2019). However, most of these concern residents’ perceptions of tourism, their ability to participate, their sense of community belonging, and the government management system (Jamal & Getz, Citation1995; Marzuki et al., Citation2012; Saufi et al., Citation2013; Tosun, Citation2000; Yang et al., Citation2008), existing studies have not yet focused on the impact of residents’ identity on their participation in tourism, especially when tourism development has brought about the development and transformation of communities and changes in settlement patterns (Xu et al., Citation2015). This study aims to fill this gap by examining the relationship between residents’ identity in migratory villages and their participation in tourism. Therefore, this paper is to explore the impact and mechanism of the social identity of residents in migrating villages on community participation in tourism, using Simatai new village as an example to build a social identity-community participation model drawing on social identity theory. At a theoretical level, this study will contribute a new perspective to the study of community participation in tourism. At an applied level, it will help policymakers in migratory villages understand the issues affecting residents’ participation in tourism to inform and improve development and policy decisions.

The structure of this paper is as follows. The literature review will be conducted to discuss the theoretical basis for social identity, tourism support, and community participation in tourism. Accordingly, seven research hypotheses are proposed. A method for testing the hypotheses will then be described. Following the analysis of data, implications, and limitations are discussed.

2. Literature review and hypotheses

2.1 Community participation in tourism

Community participation means that residents truly actively and consciously participate in the process of tourism decision-making, tourism management, and tourism planning, to promote the sustainable development of tourism and the community (Bao & Sun, Citation2006; Tosun, Citation1999). In Tourism: A Community Approach, Murphy (Citation1985) first proposed the concept of community participation and advocated the study of tourism from a community perspective. The WTO, WTTC, and Earth Council released ‘About the 21st Century Agenda of Tourism – Realize Sustainable Development Adapting to the Environment’ in 1997, clearly stating that an important aspect of sustainable tourism development is community participation (Zhifei & Qin, Citation2010), which indicates the importance of community participation in tourism and reflects that community participation is an important factor affecting sustainable tourism development.

Existing literature suggests that a number of factors influence community participation in tourism. Identifying these factors can help to deepen the understanding of community participation and promote the development of sustainable tourism. Previous research demonstrates that factors such as lack of expertise due to low literacy level, poor interaction among stakeholders, limited access to benefits, and lack of support from other actors hinder active community participation (Du et al., Citation2012; Gohori & van der Merwe, Citation2021; Hung et al., Citation2011; Jepson et al., Citation2014; Nurlena & Musadad, Citation2021), however, few have explored the impact on community participation in tourism from an identity perspective.

In the tourism literature, different forms of community participation have been recognized. Arnstein (Citation1969) first proposed the classic and influential eight-step ladder of citizen participation, divided into three groups, namely manipulative participation, citizen tokenism, and citizen power. Likewise, Pretty (Citation1995) outlined different types of participation, ranging from manipulative participation, passive participation, to self-mobilization. Based on the research of Arnstein (Citation1969) and Pretty (Citation1995), Tosun (Citation2006) developed a typology of community participation in tourism, which includes three integrated forms of participation: spontaneous participation, induced participation, and coercive participation. While in this study, the type of community participation in this study is more inclined to induced participation. As community development relies heavily on business-led tourism projects, government agencies, and tourism developers dominated tourism planning and development, even though many residents participate in and benefit from them. They consulted the community on tourism development, yet only a few resident representatives participated in the decision-making process, and most residents were excluded from the decision-making.

Moreover, the measurement of community participation has been well discussed in tourism literature. Tourism scholars examined community participation from community empowerment, decision-making, community knowledge about tourism, tourism training, etc (Fong & Lo, Citation2015; Hou & Huang, Citation2010; Shani & Pizam, Citation2012; Tosun, Citation2000). The selection of these indicators is contextually relevant to each tourism destination and depends on the social and cultural background of the local community and the level of tourism development within the region (Brunt & Courtney, Citation1999; Mowforth & Munt, Citation2008). Therefore, based on the above literature and the background of this study, community participation in tourism in this study mainly involves residents’ awareness of participation, participation in decision-making and opinion, and participation in tourism training.

2.2 Social identity

People typically identify the groups they belong to based on their gender, religion, political affiliation, nationality, membership, etc. However, the extent to which they identify determines whether they will engage in intergroup behavior (Hogg & Reid, Citation2006). Social identity theory (Tajfel, Citation1978, Citation1981; Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979) examines the important connection between individuals and groups and explains why people seek to identify with and be part of a group. Tajfel (Citation1981, p. 255) believes that social identity ‘is an individual’s recognition that he belongs to a specific group, and also recognizes the emotional and value meaning of being a member of the group’. Individuals’ self-concept incorporates the social identity from a social group and the affective and evaluative meanings associated with that membership once they have internalized membership in that group. In addition, identity is seen as a ‘dynamic structure that responds to changes in long-term intergroup relations and immediate interaction contexts, and elaborates on the underlying social cognitive mechanisms’ (Hogg et al., Citation1995, p. 266). Tajfel and Turner (Citation1979) argue that individuals may behave in a variety of ways, but common intragroup behaviors connect individuals to the social structures in which they live. Thus, social identity theory appears to be a suitable framework for understanding collective behavior in the tourism context (Chen et al., Citation2018).

Research on social identity in the context of tourism involves many relevant groups in the tourism industry, mainly focusing on the identity of community residents (Chen et al., Citation2018; Esteban & Macarena, Citation2007; Palmer et al., Citation2013; Ye et al., Citation2014) and tourists (Boone et al., Citation2013; Gieling & Ong, Citation2016; Shipway & Jones, Citation2007). The types of communities studied are mainly concentrated in cities, heritage sites, islands, and tourism towns, and there are few studies on migratory villages, which provides an opportunity for the current research.

Currently, there are also numerous studies on social identity measurement, and the research dimensions mainly involve cognitive, affective, evaluative, community identity, cultural identity, occupational identity, regional identity, etc. Ellemers et al. (Citation1999) and Palmer et al. (Citation2013) divided social identity into the cognitive, affective, and evaluation dimensions of social identity. Nunkoo and Gursoy (Citation2012) studied social identity from the dimensions of occupational identity, environmental identity, and gender identity. Sinclair-Maragh and Gursoy (Citation2017), on the other hand, used three dimensions of gender identity, cultural identity, and occupational identity to measure residents’ identity.

Since migratory villages are a special form of organization, for the residents, when they move into a new community, they must face changes in living environment, occupational types, and social atmosphere, and need to establish their identity with the new area. Therefore, in this study, social identity is divided into three dimensions: community identity, regional identity, and occupational identity. These measures of social identity are reasonable as everyone possesses many identities and belongs to various groups divided by variables such as race, religion, age, and class (Stryker & Burke, Citation2000).

2.2.1 Community identity

Community identity refers to residents’ sense of identification with their community (Puddifoot, Citation1995), and it is also a dynamic reflection of residents’ perception of the natural and social environment of the community. According to social identity theory, the identity of social actors will be activated when there is a change in the social environment (Owens et al., Citation2010). It is important to examine community identity in this study because the new community after the relocation is very different from the original traditional community in terms of the community landscape setting, infrastructure, and social environment (Guo et al., Citation2020; Wei et al., Citation2018). Whether residents are satisfied and recognized by the new community is one of the main concerns after relocation, so it is necessary to know more about residents’ community identity.

Extant literature has been conducted to explore the measurement of community identity. Lalli (Citation1992) suggested that community identity includes five dimensions, namely external evaluation, continuity with personal past, general attachment, familiarity, and commitment. Puddifoot (Citation1995) classified community identity into 14 dimensions such as ‘evaluation of community quality of life’ and ‘evaluation of community functioning.’ While Ziqiang and Xihuan (Citation2015) defined community identity in terms of two dimensions: functional identity and emotional identity. Since migratory villages are newly built communities, residents are more concerned with aspects such as the function of the community, the quality of life in the community, and neighborhood relationships, thus this study will also measure community identity from community satisfaction, convenience, neighborhood relations, and community attention.

Previous research has shown that community identity is a shaping factor in residents’ attitudes and behaviors (Kitnuntaviwat & Tang, Citation2008; Wang & Chen, Citation2015). The stronger the residents’ sense of identity with the community, the greater their confidence and expectations for the development of the community. The corresponding tendency to support the development of tourism and participate in tourism will be more obvious (Su et al., Citation2019). De Bres and Davis (Citation2001) found that community identity has a positive effect on the promotion of festival tourism. Xu et al. (Citation2015) proposed that community identity positively influences community participation in tourism development, and it has been verified. Therefore, it is argued that community identity will help residents to support tourism and participate in the development of tourism. Based on this, this paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H1a:

Community identity has a positive impact on tourism support.

H1b:

Community identity has a positive impact on community participation.

2.2.2 Regional identity

Regional identity refers to the self-identification of the relationship between groups and fixed places (Paasi, Citation2002). To a certain extent, regional identity is an explanation of the institutionalization process of regions, and it is a process of forming boundaries, symbols, and institutions in various fields (Paasi, Citation2003). In geography, regional identity is often regarded as people’s feeling of a place and belonging to it (Millard & Christensen, Citation2004). This is an inherent criterion for residents to support local development. According to social identity theory, people put themselves into various social categories through self-definition based on their sense of belonging (Tajfel & Turner, Citation1979). Correspondingly, the perceived overlap between regional characteristics and residents’ self-concept would enhance their self-esteem and increases residents’ regional identity accordingly (Semian & Chromý, Citation2014).

In this study, it is also crucial to pay attention to regional identity, as it provides the basis of residents’ identities in the context of regional transformation. This is especially the case for migratory villages, because tourism development inevitably causes changes in the natural, human, and economic environment of the entire region. Farmers’ land was centrally reclaimed, and rural spaces are increasingly being used for recreation, leisure, and tourism activities, which has challenged traditional notions of the countryside. At the same time, tourism development has led to rural gentrification, blurring the lines between urban and rural landscapes (Hines, Citation2010). Such changes may result in a sense of alienation from the region and a loss of an important aspect of rural life: a sense of belonging to one’s own region (Xue et al., Citation2017). Regional identity in this study refers to the regional consciousness (Paasi, Citation2002), which refers to the expression of a sense of belonging to a region and the perception of differences between a particular region and other regions (the relationship between ‘us’ and ‘them’). In this paper, we analyze residents’ regional identity through their willingness to settle and their sense of belonging to the local area (Wenhong & Kaichun, Citation2009).

One’s emotions toward regions influence one’s attitude and way of life (Guo et al., Citation2018). The more residents identify with the region, the more they will consider the goals and success of the region as their own and actively contribute to local development (Zhang et al., Citation2017). Meanwhile, the meanings that people associate with a region can add to regional pride and distinctiveness (Ramkissoon, Citation2022a). Gu and Ryan (Citation2008) suggest that if residents feel a sense of belonging and pride in their region, they will support tourism activities and contribute to the promotion of tourism. A lack of regional identity, however, can have the opposite effect, including hindering tourism development and damaging tourist behavior (Key & Pillai, Citation2006). Therefore, in a tourism community, the higher the regional identity of the community residents, the more they support the development of local tourism, and accordingly, the higher their motivation to participate in tourism development. Based on this, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H2a:

Regional identity has a positive impact on tourism support.

H2b:

Regional identity has a positive impact on community participation.

2.2.3 Occupational identity

Occupational identity refers to a person’s sense of identity closely related to their occupation (Carroll & Lee, Citation1990). This study intends to examine the association between the occupational identity of residents and their support for tourism development. In migratory villages, tourism, as the leading industry, has changed residents’ employment structure, and the occupation of residents has changed from farmers to tourism practitioners, which may greatly affect the identity of local residents (Xue et al., Citation2017). And this identity with the occupation has been found to be a determinant of tourism attitudes (Nunkoo et al., Citation2010). Therefore, exploring the impact of residents’ occupational identity on their support and participation in tourism will provide valuable insights for similar villages that rely on tourism for economically sustainable development.

Occupation is one of the important conditions for the residents of migratory villages to ensure their survival and development. Occupation not only brings economic income to community residents and meets their living needs, but also helps community residents improve their personal qualities and provides conditions and opportunities for them to integrate into the new community in terms of economy and society. At the same time, residents’ occupational identity affects not only their occupational choices and behaviors but also their lives in the community and the development of the community. Therefore, in tourism communities, residents’ occupational identity affects their attitudes and behaviors toward tourism development (Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012; Petrzelka et al., Citation2006). Based on this, this paper proposes the following hypotheses:

H3a:

Occupational identity has a positive impact on tourism support.

H3b:

Occupational identity has a positive impact on community participation.

2.2.4 Tourism support

Tourism support is generally understood as residents’ attitudes toward tourism development (Gursoy et al., Citation2002) and is one of the sustainability indicators for tourism destinations. Lepp (Citation2007) argued that residents’ attitudes toward tourism can be crucial to tourism’s appropriateness and positive attitudes toward tourism could contribute to pro-tourism behavior. Therefore if community residents have supportive attitudes toward tourism development, it will facilitate their participation in tourism (Fallon & Kriwoken, Citation2003; Gursoy & Rutherford, Citation2004). Correspondingly, residents who benefit economically from tourism have a more satisfied overall quality of life (Han et al., Citation2023) and are more likely to hold favorable attitudes toward tourism (Deccio & Baloglu, Citation2002; McGehee & Andereck, Citation2004), which will also lead to their support for tourism development (Yu et al., Citation2011). Previous studies have analyzed tourism support attitudes from the perspective of local tourism development and individual and community benefits (Lankford, Citation1994; Wang et al., Citation2006). Building on existing studies, this paper will measure support for tourism in terms of tourism benefits and concern for local tourism development.

In the literature on the relationship between residents’ attitudes toward tourism development and their participation behaviors, residents’ attitudes toward tourism development have often been used to analyze and infer residents’ behavioral responses, which in turn reveal the relationship between residents’ attitudes and participation behavior in tourism destination communities. Cheng et al. (Citation2019) took five ecotourism communities in Taiwan as examples to explore the relationship between residents’ attitudes and community participation, and found that residents who support sustainable tourism development will be active in community tourism affairs. Nugroho and Numata (Citation2022) found that community participation in tourism activities is related to residents’ support for tourism development and proposed that residents with a supportive attitude toward tourism development are more involved in tourism activities. Andereck and Vogt (Citation2000) and Andriotis (Citation2005) confirmed that the extent of community participation in tourism would depend on residents’ attitudes. According to Martín et al. (Citation2018), if residents have positive attitudes toward tourism, then they will actively participate in community tourism activities. In line with this, our study postulates that residents’ support for tourism will lead to more active participation in tourism. Thus, we introduce the variable of attitudinal support and postulate that:

H4:

Tourism support has a positive impact on community participation.

2.2.5 Proposed conceptual model

The conceptual framework depicted in illustrates the relationships between the main structures to be studied. According to social identity theory, an individual’s identity influences behavior through attitudes (Sparks & Shepherd, Citation1992), however, it also suggests that it can directly impact behavior, unmediated by attitudes (Leary & Jones, Citation1993; Leary et al., Citation1986). Therefore, this study draws on social identity theory to develop a conceptual framework for the relationship between identity, attitude, and behavior to analyze and explain the impact of social identity on community participation. It also proposes a spontaneous path for residents to directly influence their participation in tourism (behavior) based on community identity, regional identity, and occupational identity, as well as a relatively deliberate path through an intermediary that supports tourism (attitude). This suggests that one’s attitudes may not always mediate the impact of social identity on participation. Taking this into account, we propose that the impacts of social identity are not only on community participation but also on attitudes toward tourism support should be studied.

3. Methodology

3.1 Study area

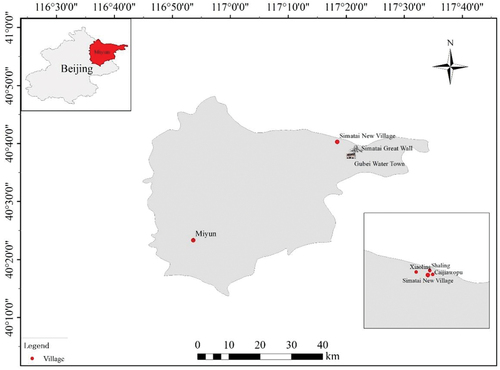

Simatai new village is a typical migratory village, which is located in the northeast of Miyun County, 120 kilometers from downtown Beijing, China, backed by the Simatai Great Wall, with beautiful natural scenery and rich tourism resources. Its predecessor was Simatai Village, with a total of 8 working units, of which 1–5 working units are located at the foot of the Great Wall, and 6–8 working units are located about 3 kilometers away from the Simatai Great Wall. In 1989, with the development of tourism on the Simatai Great Wall, the residents of Simatai Village were no longer limited to land cultivation and migrant work and began to engage in tourism-related activities in the Great Wall scenic area during their slack farming season. Among these residents, most of them are residents of working units 1, 2, and 3 who live at the foot of the Great Wall. Other residents, who live far away from the scenic spots, still focus on farming and working outside the village. At that time, the residents mainly sold local specialties and opened restaurants and farmhouses in the Great Wall scenic area. By 2009, there were 73 tourist reception households in Simatai Village, and 462 residents engaged in tourism-related work, receiving a total of about 70,000 visitors, with an annual per capita income of about 9,700 Chinese yuan.

In 2010, this area introduced the tourism construction project of Miyun Gubei Water Town. Under the guidance of the government and the assistance of enterprises, the former Simatai village working units 1–5 were relocated to the site of working units 6–8, and the new Simatai village was built centrally. The new village is divided into three natural villages, namely Xiaoling, Shaoling, and Caijiawopu (see ), and the overall relocation was completed at the end of 2012. After construction, the new village mainly relies on the Simatai Great Wall and Gubei Water Town scenic spot to develop tourism, and residents are mainly engaged in tourism, mainly operating guesthouses, providing accommodation and catering for tourists, while a small number of residents work in scenic spots and visitor service centers. At the same time, Simatai new village also set up a tourism development cooperative, which unified the management of the village’s guesthouses, unified reception standards, accommodation prices, and service items. In 2019, the village achieved a total economic income of 27 million Chinese yuan and realized an annual per capita income of about 30,000 Chinese yuan. At present, Simatai new village has 238 guesthouses with 1,240 rooms, which can receive 2,600 people at the same time.

The selection of Simatai new village as the research object is mainly based on the following factors: firstly, Simatai new village was rated as one of the key rural tourism villages in China, which is a typical representative of the overall relocation village in the process of tourism development. Secondly, the comprehensive development of tourism in Simatai new village has caused various social, economic, and environmental changes, which have had a certain impact on the identity of residents. Therefore, it presents an ideal setting to examine whether and how these changes in identity affect community participation in tourism development.

3.2 Questionnaire design

This quantitative study employed a questionnaire that consisted of two main parts, the first part was about the demographic characteristics of the respondents in the case sites, and the second part was about community participation, tourism support, community identity, regional identity, and occupational identity in the case sites, using a five-point Likert scale.

Community participation, tourism support, community identity, regional identity, and occupational identity, as structural variables, cannot be measured directly and need to set corresponding observed variables. Therefore, after summarizing the relevant literature on social identity and community participation, five groups of observed variables and 18 measurement indicators were selected. The community participation measure was based on Feng and Sha (Citation2007), Hou and Huang (Citation2010), and Fong and Lo (Citation2015), and five measures were selected. The community identity measure, which draws on Puddifoot (Citation1995) and Ziqiang and Xihuan (Citation2015), was designed with four measures. The tourism support measure referred to the research results of Nunkoo et al. (Citation2010) and Wang and Lu (Citation2014), and set four measures. The regional identity measurement index was based on the research results of Wenhong and Kaichun (Citation2009) and Li (Citation2013), and selected two measurement items. The occupational identity measure was developed by Blau (Citation1985) and Goulet and Singh (Citation2002), and three indicators were designed.

3.3 Data collection and analysis

To determine whether a questionnaire instrument is suitable for the task it is designed for, it should be tested with at least 20 participants (Parfitt, Citation2013). Thus, a pilot survey was conducted. The questionnaires were randomly distributed door-to-door in three villages, Xiaoling, Shaling, and Caijiawopu to ensure appropriate geographical representation, and 52 valid responses were obtained by on-site collection, and then an analysis of the reliability and validity of the questionnaire data was conducted. During the exploratory factor analysis of social identity, one ‘occupational identity’ item was removed from the questionnaire due to its low factor loadings. Therefore, when conducting the formal survey, there were 18 items in total in the questionnaire.

According to Hair et al. (Citation2006), it is recommended that the sample size should range between 100 and 400. This is because a sample that is too small may lead to convergence issues and inaccurate explanations, while a larger sample may result in overly sensitive maximum likelihood estimations and poor results. Meanwhile combined with the recommendation made by Thompson (Citation2000), the sample size should be at least 10 times the number of variables, since there were 18 indicators in this study, the minimum sample size was 180 (10 × 18 items).

In this study, the population size was the number of households in Simatai new village, which was 502. To ensure the representativeness of the research sample, questionnaires were distributed at least once to every two households. The formal survey was conducted among community residents who were over 18 years or older and were able to answer the questions effectively. During the survey, if there were more than one adult family member present, family members were free to choose a volunteer from within the family to answer the questionnaire. Consistent with the previous studies, the purpose of the study and anonymity of the survey were stated at the beginning in order to reduce the impact of social desirability bias on the survey. A total of 364 valid responses were received in the survey, which fulfilled the recommended minimum sample size for sampling adequacy.

As the tourism industry in Gubei Water Town has been greatly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic since early 2020, it has almost come to a standstill and the number of tourists received in Simatai New Village has also been drastically affected. Based on this, the data in this paper are still representative.

Structural equation modeling can indirectly measure quantitative relationships between latent variables and multiple explicit variables that are difficult to measure directly, as well as internal quantitative relationships, through observable explicit variables (Schreiber et al., Citation2006). It is also a multivariate data analysis method that integrates path analysis and factor analysis, and is widely used in the field of community tourism research (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Erul & Woosnam, Citation2022; Palmer et al., Citation2013). The paths in the structural equation model can clearly show the degree of relationship between latent and explicit variables, revealing the deeper issues and patterns hidden by the overall apparent relationships. In this regard, the paper conducts a confirmatory factor analysis using AMOS 24.0 based on an exploratory factor analysis using SPSS 20.0, in an attempt to deeply analyze the influence of social identity of migratory village residents on community participation in tourism.

3.4 Sample characteristics

The basic information of the respondents mainly includes gender, age, education level, average annual family income, work before relocation and current work. Briefly, 53.6% of the respondents were male; 24.2% were aged between 36 and 50 years, and 53.6% were aged between 51 and 65 years; 20.6% had completed high school education, and 72.2% had achieved only a junior high school or primary school education; 56% were relocated residents; 50.8% were engaged in agricultural cultivation before relocation, and only 20% worked in tourism-related jobs. Among the respondents, 72.3% of their household income now mainly comes from tourism, and 98.3% of the residents are currently employed in the tourism industry.

4. Results

4.1 Exploratory factor analysis and ANOVA

First, SPSS20.0 software was used to test the reliability and validity of the samples in this study. After testing, Cronbach’s α coefficient of the total scale was 0.851, which indicated that the reliability of the sample data was higher. KMO value and Bartlett spherical test were used to analyze the validity of the sample data. The KMO value was 0.833 and the approximate chi-square value of Bartlett test was 3114.626. The Bartlett spherical test was passed (p < 0.05), so the sample data was suitable for factor analysis.

The exploratory factor analysis was carried out by principal component analysis. The results showed that the factor load of 18 indexes was more than 0.5 and all the measured indexes converged into five principal component factors. The cumulative interpretation rate was 72.019, exceeding the minimum standard 60% variance contribution rate, so the five factors extracted by exploratory factor analysis were reasonable (see ).

Table 1. Results of exploratory factor analysis.

In order to analyze the factors that affect community participation in tourism in migratory villages, this paper adopts the independent sample T test and one-way ANOVA to study the influence of individual differences of residents on social identity, tourism support, and community participation. Firstly, descriptive statistical analysis was carried out on the three dimensions of community participation, tourism support, and social identity. The results showed that the total degree of community participation was not high (mean 3.23), and the average score of community participation was mostly distributed in the range of 2.4 to 4.2, indicating that the degree of residents’ participation varies greatly. The average score of tourism support was 3.68, which identified that residents’ support for tourism development was average. In terms of social identity, community identity (mean 3.92), regional identity (mean 3.60) and occupational identity (mean 3.45) were all generals. In general, residents have relatively low social identity.

Then, the common factors ‘community participation,’ ‘tourism support,’ ‘community identity,’ ‘regional identity,’ and ‘occupational identity’ were used as dependent variables to measure. The results showed that there was no significant difference in the means of the test samples when ‘sex,’ ‘age’ and ‘family income’ were taken as factor variables. When ‘education level’ was used as a factor variable, there were significant differences between ‘community identity’ and ‘regional identity.’ As shown in , the residents with higher education levels had a higher degree of community identity and regional identity.

Table 2. ANOVA for comparison of social identity and community participation for residents with different levels of education.

When ‘whether you are local or not’ was used as a factor variable, there were significant differences in ‘community identity,’ ‘occupational identity’ and ‘regional identity’ respectively. As shown in , among the perception of occupational identity, the relocated residents have the highest degree of identity, while in the perception of community identity and regional identity, the residents who had moved back had the highest level of identity.

Table 3. ANOVA for comparison of social identity and community participation for different kinds of residents.

When ‘work before relocation’ was used as a factor variable, there were significant differences in ‘community participation,’ ‘tourism support’ and ‘occupational identity.’ The results in show that residents who worked in tourism-related jobs before relocation had higher mean scores for community participation, tourism support, and occupational identity than those who worked in agricultural farming and other occupations, this is because previous tourism industry experience helped residents better understand and recognize tourism and thus actively participate in tourism.

Table 4. ANOVA for comparison of social identity and community participation for residents of different occupations before relocation.

4.2 Validation factor analysis

Based on exploratory factor analysis to test the intrinsic structural fitness of the hypothesis model, the results showed that Cronbach’s α coefficients of factors ranged from 0.807 to 0.881, indicating high reliability within the scale. Meanwhile, a measure of the internal reliability of the model is the combined reliability (CR) of latent variables, therefore, by calculating the combined reliability of latent variables of the model, it was found that the combined reliability of 5 latent variables was between 0.870 and 0.904, all of which were greater than 0.6, showing that the internal consistency of variables was very ideal. As can be seen from , the average variance extraction (AVE) was greater than 0.5, which indicates that the observed variables had better explanatory power to the latent variables.

Table 5. The results of the validation factor analysis.

4.3 Structural model testing

The proposed conceptual model was estimated using a structural equation model. An examination of the fitness index showed that the structural model had a good fit (χ2/df = 1.142, GFI = 0.961, RMSEA = 0.020, AGFI = 0.945, NFI = 0.957, IFI = 0.994, CFI = 0.993) and was therefore considered suitable for testing the hypothesized relationship.

In order to test the hypothesis, this study adopted the maximum likelihood estimation method (ML) for parameter estimation. All path coefficients were significant, suggesting that all variables had predictive power. presented the results of hypothesis testing. In terms of the effect of social identity on tourism support, community identity, regional identity, and occupational identity all had significant effects on tourism support, that is hypotheses H1a, H2a, and H3a were supported. As far as the influence of social identity on community participation, community identity, geographic identity, and occupational identity all significantly affected community participation, indicating that hypotheses H1b, H2b, and H3b were supported. Regarding the effect of tourism support on community participation, the effect of tourism support on community participation was significant, which means that hypothesis H4 was supported.

Table 6. Results of structural equation model analysis.

4.4 Mediation test

Drawing on the findings of Shrout and Bolger (Citation2002), the mediating effect of tourism support was examined using the Bootstrap method. As shown in , the upper and lower limits of the 95% confidence intervals for all three paths did not appear to be 0, which indicated that there was a mediating effect of tourism support between social identity (community identity, occupational identity, and regional identity) and community participation.

Table 7. Results of SEM analysis on mediating effect.

5. Discussion

This study expands our understanding of the effect of social identity on community participation in tourism. While previous studies on the factors influencing community participation in tourism have focused on the effects of community participation capacity, power relations, and management system, this study revealed that social identity can play a role in encouraging community participation in tourism. Especially in migratory villages, residents lose the land resources they used to rely on for survival and lose their acquired labor skills, forcing them to find alternative livelihoods. A large number of residents generally give priority to economic, and material benefits out of survival rationality and participate in tourism services and related work. However, residents have different perceptions and identifications of the spatial, social, and economic reconfiguration of villages caused by tourism development, and their motivation and depth of participation in tourism also vary.

It is essential to understand the demographic characteristics of residents for tourism development in order to develop policies and strategies that improve the welfare of the residents (Martínez‐Garcia et al., Citation2017) and further gain residents’ support for tourism development (Choi & Murray, Citation2010; Martínez‐Garcia et al., Citation2017). This study supported the previous literature (Sharma & Gursoy, Citation2015; Xu et al., Citation2016) and confirmed that demographic characteristics are important internal factors influencing the differences in community participation, tourism support, and social identity among residents of migratory village communities. Results showed that residents who were previously engaged in tourism-related industries had the highest level of support and participation in tourism, indicating that individuals whose livelihoods are directly linked to tourism are more likely to endorse tourism-related jobs and support local tourism development than those who were not dependent on tourism (McGehee & Andereck, Citation2004; Yu et al., Citation2011). While residents with higher education levels are more identified with their communities and regions. Education plays a key role in transmitting knowledge and cultivating values, and it is also an important factor affecting residents’ identities. Residents with higher levels of education are more able to view changes in their communities and regions more dialectically, and they are more aware of the possible benefits of change. Moreover, the relocated residents have the highest occupational identity, while the residents who moved back have higher community identity and regional identity. This may be because the relocated residents lived close to the Simatai Great Wall before the relocation, and some of them were engaged in tourism and had a more comprehensive understanding of tourism, as verified by previous studies (Deccio & Baloglu, Citation2002). The residents who moved back have always lived in this area and were more familiar with it, although the community has been rebuilt, they still recognized the community and the local area.

Most importantly, the study confirms that residents’ social identity in Simatai new village positively influences tourism support and community participation. Specifically, residents’ community identity positively influences their support for tourism and participation in tourism. This finding echoes Wang et al. (Citation2014) and Palmer et al. (Citation2013) that a strong sense of community identity inspires positive attitudes toward tourists and their support for local tourism development, while the strength of community identity is positively correlated with the extent to which individuals participate in tourism-related activities in their communities, residents with higher levels of community identity are more willing to integrate into the tourism development process and participate in related tourism activities. Residents’ regional identity positively influences tourism support and community participation in tourism. This indicates that the higher residents’ regional identity, the more they support tourism development and the more actively they participate in tourism. In line with this, previous research has shown that residents are more likely to support tourism when they identify with their region and tourism resources (Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012; Wang & Chen, Citation2015). This study also finds that occupational identity has a significant positive impact on tourism support and community participation in tourism. Residents with high occupational identity are more supportive of tourism and active participation in tourism-related activities, which is contradictory to the findings of previous studies conducted in different contexts (Mason & Cheyne, Citation2000; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012). The reason for this is that the pillar industry of Simatai new village is tourism, and there is no other industry to rely on, thus the development of tourism will not lead to the decline of traditional industries and will not negatively affect the traditional employment patterns of the community (Mbaiwa, Citation2011). Tourism has created jobs and income for residents, who provide accommodation and catering services directly to tourists, and in some cases work in related jobs in scenic areas. These benefits are positively recognized by residents, further enhancing their support for and participation in tourism. As confirmed by the literature (Brooks, Citation2010; Deccio & Baloglu, Citation2002; Lankford, Citation1994), residents who receive more benefits tend to support tourism development more.

Furthermore, tourism support also significantly impacts community participation in tourism. It can be said that when residents support the development of tourism, they actively participate in tourism, which is also consistent with the research conclusions of related scholars (Andriotis, Citation2005; Martín et al., Citation2018; Nugroho & Numata, Citation2022). Meanwhile, tourism support plays a mediating role in the process of residents’ social identity affecting community participation, indicating that the impact of a person’s social identity on their participation in tourism is mediated by his attitude toward tourism support, which is in line with the social identity theory that people’s identities will affect their attitudes and behaviors within social structures (Stets & Biga, Citation2003; Stryker & Burke, Citation2000). While previous research has emphasized the importance of residents’ attitudes toward supporting tourism in community participation (Martín et al., Citation2018; Nugroho & Numata, Citation2022), It has not been studied the impact of residents’ attitudes toward tourism on social identity and community participation. The results of this study demonstrate the role and importance of tourism support in social identity and community participation in tourism.

6. Conclusion and implication

It is essential for tourism planners to recognize the dynamics of residents’ social identities and how it affects residents’ support and participation in tourism. Premised on social identity theory, this study investigated three dimensions of residents’ social identities since they link to residents’ support and participation in tourism, which are community, geographic, and occupational identity. Seven hypotheses are proposed based on the literature review, and the structural equation model results show support for all hypotheses. These are important findings for tourism policy and planning decisions, especially considering migratory villages such as Simatai new village depend on tourism for their economic prosperity. Residents’ social identity determines the extent to which they participate in tourism for the sustainable development of community tourism.

This study contributes to tourism theory by employing social identity theory to empirically demonstrate the role of the construct in community participation in tourism. Previous studies have examined the factors influencing community participation in tourism using different theories (Kunasekaran et al., Citation2022; Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2017), however, the role of residents’ social identity on community participation remains under-explored. The findings confirm the effectiveness and appropriateness of the framework of social identity theory in terms of residents’ attitudes and participation in tourism development in migratory villages, constituting an important theoretical contribution.

This study also shows that residents’ social identity promotes their support and participation in tourism development, and thus generates more sustainable social benefits (Han et al., Citation2023). This is well in line with the 2030 UN agenda for Sustainable Development (Ramkissoon, Citation2022b, Citation2023). In addition, this study demonstrates that although individuals’ identities are found to affect attitudes toward tourism, they have a stronger impact on participation, confirming that identity is a good determinant of behavior (Hagger et al., Citation2007; Nunkoo & Gursoy, Citation2012).

For migratory villages such as Simatai New Village, community participation in tourism development is the guarantee for residents to obtain a sustainable source of living, and residents’ support for tourism development can improve their overall quality of life (Ramkissoon, Citation2022a, Citation2023). From a practical perspective, the findings of this study suggest that to effectively encourage residents’ support and participation in tourism, the local government should approach strategic tourism planning from the perspective of residents’ community identity, regional identity, and occupational identity. Hence, the government and relevant departments need to consider enhancing the community’s cohesion, strengthening the infrastructure construction, and improving the community identity of the residents, so as to obtain the community’s support. At the same time, residents can carry out tourism-related educational projects, publicize and highlight the social and cultural benefits of tourism, and strengthen residents’ understanding and recognition of tourism. Training and educating residents to engage in tourism is an important source of local empowerment (Nunkoo & So, Citation2016), which in turn promotes community participation in tourism development.

Lastly, it is important to consider the limitations. This study used a quantitative approach to demonstrate the relationship between residents’ social identities, support, and participation in tourism, and lacked qualitative perspective to explain some of the relations revealed in the research. Qualitative methods are able to capture perceptual aspects and real-life events, helping to uncover nuances of social identity that quantitative data may not be able to effectively capture, thus deepening the understanding of residents’ perceptions of tourism (Nunkoo et al., Citation2013). Realizing these limitations, future research is encouraged to employ a mixed approach to further explore the links between social identity, tourism support, and engagement behaviors, as it can provide a richer perspective by combining quantitative data with qualitative insights. Furthermore, this study explored the relationship between social identity and community participation of residents in migratory villages through an empirical study, and has not provided a comprehensive interpretation of the tourism phenomenon of migratory villages, so it is suggested that this tourism phenomenon can be explored in depth in the future.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Yuan Qin

Yuan Qin is a Ph.D. student in the Department of Tourism at University of Otago, New Zealand. Her research interest is focused on tourism community development and destination management.

Julia N. Albrecht

Julia N. Albrecht is an Associate Professor in Tourism at the University of Otago, New Zealand. Her research interests include tourism destination management, visitor management, and nature-based tourism. Julia is a co-editor of the Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism.

Li Tao

Li Tao is Professor in the School of Resources, Environment and Tourism at Capital Normal University and the Dean of Capital Tourism Research Institute, Beijing, China. Her research interests include tourism destination planning and management, tourism development of linear cultural heritage, tourism community development and tourism impact studies.

References

- Ahearne, M., Bhattacharya, C. B., & Gruen, T. (2005). Antecedents and consequences of customer-company identification: Expanding the role of relationship marketing. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(3), 574–585. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.3.574

- Andereck, K. L., & Vogt, C. A. (2000). The relationship between residents attitudes toward tourism and tourism development options. Journal of Travel Research, 39(1), 27–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728750003900104

- Andriotis, K. (2005). Community groups’ perceptions of and preferences for tourism development: Evidence from crete. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 29(1), 67–90. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348004268196

- Arnstein, S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. Journal of the American Institute of Planners, 35(4), 216–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944366908977225

- Bao, J., & Sun, J. (2006). A contrastive study on the difference in community participation in tourism between China and the west. Acta Geologica Sinica‐Chinese Edition, 61(4), 413.

- Blau, G. J. (1985). The measurement and prediction of career commitment. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 58(4), 277–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1985.tb00201.x

- Boley, B. B., & Strzelecka, M. (2016). Towards a universal measure of “support for tourism”. Annals of Tourism Research, 61(C), 238–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.09.001

- Boone, K., Kline, C., Johnson, L., Milburn, L.-A., & Rieder, K. (2013). Development of visitor identity through study abroad in Ghana. Tourism Geographies, 15(3), 470–493. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2012.680979

- Brandth, B., & Haugen, M. S. (2011). Farm diversification into tourism–implications for social identity? Journal of Rural Studies, 27(1), 35–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2010.09.002

- Brooks, C. F. (2010). Toward ‘hybridised’faculty development for the twenty‐first century: Blending online communities of practice and face‐to‐face meetings in instructional and professional support programmes. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 47(3), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2010.498177

- Brunt, P., & Courtney, P. (1999). Host perceptions of sociocultural impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(3), 493–515. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00003-1

- Carroll, M. S., & Lee, R. G. (1990). Occupational community and identity among pacific northwestern loggers: Implications for adapting to economic changes. In R. G. Lee, D. R. Field, & W. R. Burch (Eds.), Community and forestry (pp. 141–155). Routledge.

- Cheng, T.-M., Wu, H. C., Wang, J. T.-M., & Wu, M.-R. (2019). Community participation as a mediating factor on residents’ attitudes towards sustainable tourism development and their personal environmentally responsible behaviour. Current Issues in Tourism, 22(14), 1764–1782. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1405383

- Chen, N., Hsu, C. H. C., & Li, X. (2018). Feeling superior or deprived? Attitudes and underlying mentalities of residents towards mainland Chinese tourists. Tourism Management, 66, 94–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2017.11.007

- Choi, H. C., & Murray, I. (2010). Resident attitudes toward sustainable community tourism. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(4), 575–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903524852

- De Bres, K., & Davis, J. (2001). Celebrating group and place identity: A case study of a new regional festival. Tourism Geographies, 3(3), 326–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616680110055439

- Deccio, C., & Baloglu, S. (2002). Nonhost community resident reactions to the 2002 Winter Olympics: The spillover impacts. Journal of Travel Research, 41(1), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287502041001006

- Du, Z., Su, Q., & Jiang, L. (2012). Mediate effects of community involvement influence on sense of community in tourism destination: A case study of Anji County in Zhejiang Province. Scientia Geographica Sinica, 32(3), 329–335. https://doi.org/10.13249/j.cnki.sgs.2012.03.012

- Dutton, J. E., Dukerich, J. M., & Harquail, C. V. (1994). Organizational images and member identification. Administrative Science Quarterly, 39(2), 239–263. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393235

- Ellemers, N., Kortekaas, P., & Ouwerkerk, J. W. (1999). Self-categorisation, commitment to the group and group self-esteem as related but distinct aspects of social identity. European Journal of Social Psychology, 29(2–3), 371–389. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199903/05)29:2/3<371:AID-EJSP932>3.0.CO;2-U

- Erul, E., & Woosnam, K. M. (2022). Explaining residents’ behavioral support for tourism through two theoretical frameworks. Journal of Travel Research, 61(2), 362–377. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287520987619

- Esteban, R. B., & Macarena, H. R. (2007). Identity and community—reflections on the development of mining heritage tourism in Southern Spain. Tourism Management, 28(3), 677–687. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.001

- Fallon, L. D., & Kriwoken, L. K. (2003). Community involvement in tourism infrastructure—the case of the Strahan Visitor Centre, Tasmania. Tourism Management, 24(3), 289–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(02)00072-9

- Fan, L.-N., Wu, M.-Y., Wall, G., & Zhou, Y. (2021). Community support for tourism in China’s Dong ethnic villages. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 19(3), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2019.1659283

- Feng, S., & Sha, R. (2007). Evaluation model of countryside tourism’s rural feature: A case study of Wuyuan in Jiangxi province. Geographical Research, 26(3), 616–624.

- Fong, S. F., & Lo, M. C. (2015). Community involvement and sustainable rural tourism development: Perspectives from the local communities. European Journal of Tourism Research, 11, 125–146. https://doi.org/10.54055/ejtr.v11i.198

- Gieling, J., & Ong, C.-E. (2016). Warfare tourism experiences and national identity: The case of airborne museum ‘Hartenstein’ in Oosterbeek, the Netherlands. Tourism Management, 57, 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.05.017

- Gohori, O., & van der Merwe, P. (2021). Barriers to community participation in Zimbabwe’s community-based tourism projects. Tourism Recreation Research, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2021.1989654

- Goulet, L. R., & Singh, P. (2002). Career commitment: A reexamination and an extension. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 61(1), 73–91. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.2001.1844

- Guo, A., Wang, S., Li, H., & Guo, Y. (2020). Influence mechanism of residents’ perception of tourism impacts on supporting tourism development: Intermediary role of community satisfaction and community identity. Tourism Tribune, 35(6), 96–108.

- Guo, Y., Zhang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2018). Influencing factors and mechanism of community resilience in tourism destinations. Geographical Research, 37(1), 133–144. https://doi.org/10.11821/dlyj201801010

- Gursoy, D., Jurowski, C., & Uysal, M. (2002). Resident attitudes - a structural modeling approach. Annals of Tourism Research, 29(1), 79–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(01)00028-7

- Gursoy, D., & Rutherford, D. G. (2004). Host attitudes toward tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(3), 495–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.08.008

- Gu, H., & Ryan, C. (2008). Place attachment, identity and community impacts of tourism—the case of a Beijing hutong. Tourism Management, 29(4), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2007.06.006

- Hagger, M. S., Anderson, M., Kyriakaki, M., & Darkings, S. (2007). Aspects of identity and their influence on intentional behavior: Comparing effects for three health behaviors. Personality & Individual Differences, 42(2), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.07.017

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R. L. (2006). Multivariate data analysis (6th ed.). Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Han, S., Ramkissoon, H., You, E., & Kim, M. J. (2023). Support of residents for sustainable tourism development in nature-based destinations: Applying theories of social exchange and bottom-up spillover. Journal of Outdoor Recreation and Tourism, 43, 100643. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jort.2023.100643

- Hines, J. D. (2010). Rural Gentrification as Permanent Tourism: The Creation of the ‘New’ West Archipelago as Postindustrial Cultural Space. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 28(3), 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1068/d3309

- Hogg, M. A., & Reid, S. A. (2006). Social identity, self-categorization, and the communication of group norms. Communication Theory, 16(1), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2006.00003.x

- Hogg, M. A., Terry, D. J., & White, K. M. (1995). A tale of two theories: A critical comparison of identity theory with social identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 58(4), 255–269. https://doi.org/10.2307/2787127

- Hou, G., & Huang, Z. (2010). Evaluation on tourism community participation level based on AHP method with entropy weight. Geographical Research, 29(10), 1802–1813.

- Hung, K., Sirakaya-Turk, E., & Ingram, L. J. (2011). Testing the efficacy of an integrative Model for community participation. Journal of Travel Research, 50(3), 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287510362781

- Jamal, T. B., & Getz, D. (1995). Collaboration theory and community tourism planning. Annals of Tourism Research, 22(1), 186–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(94)00067-3

- Jepson, A., Clarke, A., & Ragsdell, G. (2014). Investigating the application of the motivation-opportunity-ability model to reveal factors which facilitate or inhibit inclusive engagement within local community festivals. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 14(3), 331–348. https://doi.org/10.1080/15022250.2014.946230

- Jia, K., Qiao, W., Chai, Y., Feng, T., Wang, Y., & Ge, D. (2020). Spatial distribution characteristics of rural settlements under diversified rural production functions: A case of Taizhou, China. Habitat International, 102, 102201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.habitatint.2020.102201

- Key, C., & Pillai, V. K. (2006). Community participation and tourism attitudes in Belize. Interamerican Journal of Environment and Tourism, 2(2), 8–15.

- Kitnuntaviwat, V., & Tang, J. C. S. (2008). Residents’ attitudes, perception and support for sustainable tourism development. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 5(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530801936452

- Kunasekaran, P., Mostafa Rasoolimanesh, S., Wang, M., Ragavan, N. A., & Hamid, Z. A. (2022). Enhancing local community participation towards heritage tourism in Taiping, Malaysia: Application of the motivation-opportunity-ability (MOA) model. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 17(4), 465–484. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2022.2048839

- Lalli, M. (1992). Urban-related identity: Theory, measurement, and empirical findings. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 12(4), 285–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-4944(05)80078-7

- Lankford, S. V. (1994). Attitudes and perceptions toward tourism and rural regional development. Journal of Travel Research, 32(3), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/004728759403200306

- Leary, M. R., & Jones, J. L. (1993). The social psychology of tanning and sunscreen use: Self-presentational motives as a predictor of health Risk1. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 23(17), 1390–1406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.1993.tb01039.x

- Leary, M. R., Wheeler, D. S., & Jenkins, T. B. (1986). Aspects of identity and behavioral preference: Studies of occupational and recreational choice. Social Psychology Quarterly, 49(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786853

- Lepp, A. (2007). Residents’ attitudes towards tourism in Bigodi village, Uganda. Tourism Management, 28(3), 876–885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.03.004

- Li, H. (2013). Social Identification and Regional Difference of Tourist Immigrant in ZhouZhuang [ Doctoral dissertation, AnHui Normal University].

- Li, T., Lu, L., & Zhang, X. (2021). Research on the characteristics and mechanism of rural social re-structuring driven by tourism: A case study of Guzhu Village in Huzhou. Journal of Chinese Ecotourism, 11(3), 332–348.

- Li, T., Wang, L., Wang, Z., Tao, Z., & Liu, J. (2022). The different development and mechanism of community-oriented rural tourism and scenic-oriented rural tourism: Case studies on the typical villages in Zhejiang and Shanxi. Tourism Tribune, 37(3), 96–107. https://doi.org/10.31497/zrzyxb.20220809

- Mannetti, L., Pierro, A., & Livi, S. (2004). Recycling: Planned and self-expressive behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 24(2), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2004.01.002

- Martín, H. S., de Los Salmones Sánchez, M. M. G., & Herrero, Á. (2018). Residentsʼ attitudes and behavioural support for tourism in host communities. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 35(2), 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2017.1357518

- Martínez‐Garcia, E., Raya, J. M., & Majó, J. (2017). Differences in residents’ attitudes towards tourism among mass tourism destinations. International Journal of Tourism Research, 19(5), 535–545. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2126

- Marzuki, A., Hay, I., & James, J. (2012). Public participation shortcomings in tourism planning: The case of the Langkawi Islands, Malaysia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 20(4), 585–602. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.638384

- Mason, P., & Cheyne, J. (2000). Residents’ attitudes to proposed tourism development. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(2), 391–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00084-5

- Mbaiwa, J. E. (2011). Changes on traditional livelihood activities and lifestyles caused by tourism development in the Okavango Delta, Botswana. Tourism Management, 32(5), 1050–1060. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.09.002

- McGehee, N. G., & Andereck, K. L. (2004). Factors predicting rural residents’ support of tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 43(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287504268234

- Millard, J., & Christensen, A. L. (2004). Regional identity and the information (BISER Domain Report No. 4). Bonn, Germany: BISER.

- Mowforth, M., & Munt, I. (2008). Tourism and sustainability: Development, globalisation and new tourism in the Third World. Routledge.

- Murphy, P. E. (1985). Tourism: A community approach. New York: Methuen. National Parks Today (1991): Green Guide for Tourism, 31, 224–238. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203068533

- Nugroho, P., & Numata, S. (2022). Resident support of community-based tourism development: Evidence from Gunung Ciremai National Park, Indonesia. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(11), 2510–2525.

- Nunkoo, R., & Gursoy, D. (2012). Residents’ support for tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 39(1), 243–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.05.006

- Nunkoo, R., Gursoy, D., & Juwaheer, T. D. (2010). Island residents’ identities and their support for tourism: An integration of two theories. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(5), 675–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003602341

- Nunkoo, R., Smith, S. L., & Ramkissoon, H. (2013). Residents’ attitudes to tourism: A longitudinal study of 140 articles from 1984 to 2010. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.673621

- Nunkoo, R., & So, K. K. F. (2016). Residents’ support for tourism. Journal of Travel Research, 55(7), 847–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287515592972

- Nurlena, N., & Musadad, M. (2021). Factors supporting the success of community-based tourism in ciletuh geopark. Journal of Business on Hospitality and Tourism, 7(3), 339–349. https://doi.org/10.22334/jbhost.v7i3.264

- Obradović, S., & Stojanović, V. (2022). Measuring residents’ attitude toward sustainable tourism development: a case study of the Gradac River gorge, Valjevo (Serbia). Tourism Recreation Research, 47(5–6), 499–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/02508281.2020.1870073

- Owens, T. J., Robinson, D. T., & Smith-Lovin, L. (2010). Three faces of identity. Annual Review of Sociology, 36(1), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.34.040507.134725

- Paasi, A. (2002). Bounded spaces in the mobile world: Deconstructing ‘regional identity’. Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, 93(2), 137–148. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9663.00190

- Paasi, A. (2003). Region and place: regional identity in question. Progress in Human Geography, 27(4), 475–485. https://doi.org/10.1191/0309132503ph439pr

- Palmer, A., Koenig-Lewis, N., & Medi Jones, L. E. (2013). The effects of residents’ social identity and involvement on their advocacy of incoming tourism. Tourism Management, 38, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.02.019

- Parfitt, J. (2013). Questionnaire design and sampling. In R. Flowerdew & D. M. Martin (Eds.), Methods in human geography (pp. 78–109). Routledge.

- Petrzelka, P., Krannich, R. S., & Brehm, J. M. (2006). Identification with resource-based occupations and desire for tourism: Are the two necessarily inconsistent? Society & Natural Resources, 19(8), 693–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920600801108

- Pretty, J. (1995). The many interpretations of participation. Focus, 16(4), 4–5.

- Puddifoot, J. E. (1995). Dimensions of community identity. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 5(5), 357–370. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2450050507

- Ramkissoon, H. (2022a). Cultural tourism impacts and place meanings: Focusing on the value of domestic tourism. In A. Stoffelen & D. Ioannides (Eds.), Handbook of Tourism Impacts: Social and Environmental Perspectives (pp. 75–87). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781800377684.00015

- Ramkissoon, H. (2022b). Perceived visitor impacts of cultural heritage tourism: The role of place attachment in memorable visitor experiences. In D. Agapito, R. Manuel Alector, & W. Kyle Maurice (Eds.),Handbook on the Tourist Experience: design, marketing and management. (pp. 166–175). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839109393.00019.

- Ramkissoon, H. (2023). Perceived social impacts of tourism and quality-of-life: A new conceptual model. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 31(2), 442–459. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1858091

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Jaafar, M., Ahmad, A. G., & Barghi, R. (2017). Community participation in World Heritage Site conservation and tourism development. Tourism Management, 58, 142–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2016.10.016

- Saufi, A., O’Brien, D., & Wilkins, H. (2013). Inhibitors to host community participation in sustainable tourism development in developing countries. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 22(5), 801–820. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2013.861468

- Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323–338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

- Semian, M., & Chromý, P. (2014). Regional identity as a driver or a barrier in the process of regional development: A comparison of selected European experience. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift - Norwegian Journal of Geography, 68(5), 263–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00291951.2014.961540

- Shani, A., & Pizam, A. (2012). Community participation in tourism planning and development. In M. Uysal, R. Perdue, & M. J. Sirgy (Eds.), Handbook of Tourism and Quality-Of-Life Research (pp. 547–564). Springer Dordrecht. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2288-0_32

- Sharma, B., & Gursoy, D. (2015). An examination of changes in residents’ perceptions of tourism impacts over time: The impact of residents’ socio-demographic characteristics. Asia Pacific Journal of Tourism Research, 20(12), 1332–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/10941665.2014.982665

- Shipway, R., & Jones, I. (2007). Running away from home: Understanding visitor experiences and behaviour at sport tourism events. International Journal of Tourism Research, 9(5), 373–383. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.641

- Shrout, P. E., & Bolger, N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7(4), 422. https://doi.org/10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422

- Sinclair-Maragh, G., & Gursoy, D. (2017). Residents’ identity and tourism development: The Jamaican perspective. International Journal of Tourism Sciences, 17(2), 107–125. https://doi.org/10.1080/15980634.2017.1313472

- Sparks, P., & Shepherd, R. (1992). Self-identity and the theory of planned behavior: Assesing the role of identification with“green consumerism”. Social Psychology Quarterly, 55(4), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.2307/2786955

- Stets, J. E., & Biga, C. F. (2003). Bringing identity theory into environmental sociology. Sociological Theory, 21(4), 398–423. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9558.2003.00196.x

- Stryker, S., & Burke, P. J. (2000). The past, present, and future of an identity theory. Social Psychology Quarterly, 63(4), 284–297. https://doi.org/10.2307/2695840

- Su, L., Huang, S., & Nejati, M. (2019). Perceived justice, community support, community identity and residents’ quality of life: Testing an integrative model. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Management, 41, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhtm.2019.08.004

- Tajfel, H. (1978). The social psychology of minorities. Minority Rights Group.

- Tajfel, H. (1981). Human groups and social categories. Cambridge university press.

- Tajfel, H., & Turner, J. C. (1979). An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. In W. G. Austin & S. Worchel (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup relations (pp. 33–47). Brooks/Cole.

- Thompson, B. (2000). Ten Commandments of structural equation modeling. US Dept of Education, Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) Project Directors’ Conference, 1998, Washington, DC, US; A previous version of this chapter was presented at the aforementioned conference and at the same annual conference held in 1999.

- Tosun, C. (1999). Towards a typology of community participation in the tourism development process. Anatolia, 10(2), 113–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.1999.9686975

- Tosun, C. (2000). Limits to community participation in the tourism development process in developing countries. Tourism Management, 21(6), 613–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0261-5177(00)00009-1

- Tosun, C. (2006). Expected nature of community participation in tourism development. Tourism Management, 27(3), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2004.12.004

- Tosun, C., Dedeoğlu, B. B., Çalışkan, C., & Karakuş, Y. (2021). Role of place image in support for tourism development: The mediating role of multi‐dimensional impacts. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(3), 268–286. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2405

- Wang, S., & Chen, J. S. (2015). The influence of place identity on perceived tourism impacts. Annals of Tourism Research, 52, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.02.016

- Wang, Y., & Lu, L. (2014). Community tourism support model and its application based on social exchange theory: Case studies of gateway communities of Huangshan Scenic Area. Acta Geographica Sinica, 69(10), 1557–1574.