ABSTRACT

Cyber security has become one of the biggest priorities for businesses and governments. Streamlining and strengthening strategic leadership are key aspects in making sure the cyber security vision is achieved. The strategic leadership of cyber security implies identifying and setting goals based on the protection of the digital operating environment. Furthermore, it implies coordinating actions and preparedness as well as managing extensive disruptions. The aim of this article is to define what is strategic leadership of cyber security and how it is implemented as part of the comprehensive security model in Finland. In terms of effective strategic leadership of cyber security, it is vital to identify structures that can respond to the operative requirements set by the environment. As a basis for national security development and preparedness, it is necessary to have a clear strategy level leadership model for crises management in disturbances in normal and in emergency conditions. In order to ensure cyber security and achieve the set strategic goals, society must be able to engage different parties and reconcile resources and courses of action as efficiently as possible. Cyber capability must be developed in the entire society, which calls for strategic coordination, management and executive capability.

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

Cyber security is an elemental part of society’s comprehensive security, and the cyber security operating model is in keeping with the principles and practices specified in Finland´s Security Strategy for Society (Citation2017b). Cybersecurity has become a focal point for conflicting domestic and international interests, and increasingly for the projection of state power (Limnéll, Citation2016). The challenges of cyber security management are particularly prominent at the level of strategic leadership.

Cybersecurity is a foundational element underpinning the achievement of socio-economic objectives of modern economies. Digitalization and information societies are ever evolving, and new cyber threats continue to be devised. In this progress, cyber security must form an integral and indivisible part of the nation’s security process. Countries need to be aware of their current capability level in cyber security and at the same time identify areas where cybersecurity needs to be enhanced. It can be said that cyber security is a constant “arms race” between countries, but also between the security community and the hostile hackers. Cybersecurity is a complex challenge that encompasses multiple different governance, policy, operational, technical and legal aspects (ITU, Citation2018; Lehto & Limnéll, Citation2016).

Cyber-attacks, malware, denial of service attacks and different forms of influencing through information are becoming ever more prolific. The reliable operation of telecommunications, information systems and communications are an essential precondition for modern society’s undisrupted functioning, security and citizens’ livelihoods. This is also about maintaining citizens’ trust in a well-functioning society. The development of business continuity management accounts for a large proportion of the security of supply work carried out in the information society sector. Due to this development, improved preparedness for maintaining the functioning of society’s vital information technology systems and structures in the face of cyber threats and incidents is also needed in normal conditions. In particular, it should be noted that Finnish society’s and companies’ dependence on the cyber environment will grow further in the years to come (Lehto et al., Citation2018).

The transformational power of ICTs and the Internet as catalysts for economic growth and social development are at a critical point where citizens’ and national trust and confidence in the use of ICTs are being eroded by cyber-insecurity. To fully realize the potential of technology, states must align their national economic visions with their national security priorities. Setting out the vision, objectives and priorities enables governments to look at cybersecurity holistically across their national digital ecosystem, instead of at a particular sector, objective, or in response to a specific risk – it allows them to be strategic (ITU, Citation2018).

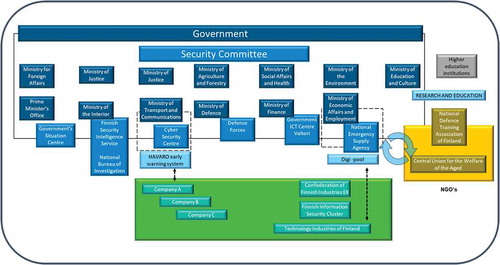

The national strategic leadership of cyber security consists of two entities: managing cyber security preparedness and managing serious and extensive incidents in normal and emergency conditions. The Security Strategy for Society 2017 discusses a general functional model for leadership and incident management, which describes the relationships between the government’s top management on the one hand, and local and regional level management on the other (). Today the Prime Minister’s Office has an important role in coordinating the authorities’ activities and supporting the Government’s decision-making (Security committee, Citation2017a).

1.2. Objectives of the research

This article is based on a research we made for the Prime Minister’s Office in 2017–2018 (Lehto et al., Citation2018). In terms of Cyber Security Strategy implementation and the commitment of different branches of administration, the situation in Finland was different from what it was as the first Cyber Security Strategy was prepared in 2013. The branches of administration had widely recognized the significance of cyber security in their everyday work. While their views of cyber security differed around the time the 2013 strategy was drafted, the world has changed rapidly since its publication.

This research project prepared proposals for measures related to the management of society’s and public administration’s cyber security, measuring the state of cyber security and preparedness, and managing extensive disruptions in the cyber environment.

Key research questions examined were the following:

What is strategic leadership of cyber security and how is it implemented in the responsibility model for comprehensive security?

How can a general incident management model be implemented during extensive cyber security disruptions?

How should the strategic leadership of cyber security be organized?

How is the management of cyber security in central government structured?

1.3. Data and methodology

Highly versatile and extensive material was collected for the study. Key data consisted of different security-related strategies and instructions, existing research information, and interviews with public sector actors and experts of the field. The research project interviewed 40 employees in managerial roles and officers responsible for information/cyber security in private and public organizations. The interviews were conducted as semi-structured thematic interviews and the interviewees were promised full anonymity.

The interviews were transcribed and clustered under different themes like strategic leadership of cyber security and strategic leadership model of cyber security. Based on the interviews, document analysis and international comparison data, an analyzed data set was created, on which the observations, proposals and models presented in this report are based. The interviewees represented the following organizations illustrated in the .

Table 1. Organizations from which data were collected

Finland’s Cyber Security Strategy (Citation2013) and its Implementation Programme 2017–2020, the Security Strategy for Society (Citation2017a), a report titled Central Government Communications in Incidents and Emergencies (Citation2013), the Guidelines for developing Finnish legislation on conducting intelligence – A report of the Working Group (Citation2015) and the National Audit Office’s performance audit report titled Cyber Protection Arrangements (Citation2017) were used in the research project. Key documents also included other central government strategies (Information Security Strategy for Finland, 2016 and others), previous studies and reports as well as international cyber security indicators.

The article asks (and answers) how the strategic leadership of cyber security must be organized based on research we made. Our research provides proposals for managing strategic cyber security in society and public administration, for managing large disruptions in the cyber operating environment. This article is constructed in the following way. After an introduction we present in the second chapter strategic leadership of cyber security included definitions, an analysis based on research, and development. In the following chapter we present five different models for the strategic leadership of cyber security. In the fourth chapter we present the solution to a new strategic cyber security management model in Finland made in October 2019. Finally, we discuss our models and the solution made by the Finnish Government.

2. Strategic leadership of cyber security

2.1. Definitions of strategic leadership of cyber security

It must be noted that strategic leadership is not an unambiguous term (Juuti & Luoma, Citation2009). It may be defined and understood in many ways. Additionally, the “boundaries” between strategic and operative management are not always clear in all situations of cyber security management, and in some instances, they are difficult to separate (while this may even be unnecessary). Different definitions of strategic leadership and the difficulty of separating strategic and operative activities also emerged, among other things, in the context of the interviews conducted for this study and the reference countries selected for the international comparison. For example, strategic leadership of cyber security was described as follows in the interviews: ”Strategic leadership means leading a phenomenon at the highest level, making an effort to define long-term visions and objectives as comprehensively as possible”.

Cyber security is an aspect of society’s and companies’ security, which is highly important when considering an organization’s strategic goals in an increasingly digital society. In the source documents of the study, strategic leadership of cyber security was often described as securing the central government’s capabilities and vital functions, also allowing the private and the NGO (non-governmental organization) to build their activities on well-functioning and secure information networks. Based on these documents, the most important task of the strategic leadership of cyber security is defined as creating a vision and a national mentality which are recognized at all levels of actors participating in cyber security work and which direct the actions in both normal and emergency conditions (Lehto & Limnéll, Citation2016).

According to International Telecommunication Union (ITU) recommendation the cyber security should be set at the highest level of the government, which will then be responsible for assigning relevant roles and responsibilities and allocating sufficient human and financial resources. Cybersecurity should be promoted and sustained at the highest levels of government (ITU, Citation2018).

According to the experts interviewed for the research project strategic leadership comprises long-term implementation of Finland’s Cyber Security Strategy and Finnish cyber security. Strategic leadership brings society toward the selected vision. The task of implementing strategic leadership is based on identifying and setting objectives derived from securing the digital operating environment.

Secondly, strategic leadership reconciles, coordinates and ensures participation in cooperation between different actors in cyber security activities and preparedness. As cyber security is an extensive societal phenomenon which connects a great number of different actors, the coordination of cooperation is stressed both in normal and emergency conditions and during incidents. Sufficient preconditions for making decisions and clearly defined powers are stressed in the activities.

Thirdly, as cyber security is a strategic issue for Finnish society, the strategic leadership of cyber security takes place in close interaction with both political decision-making and operative activities. Strategic leadership is also associated with strengthening Finland’s cyber security identity, both nationally and internationally. The cyber security identity is also associated with seeing to national cyber self-sufficiency regarding both product and service solutions and expertise and research in Finland. Domestic and international communications play an important role in creating a Finnish cyber security identity and credibility based on trust. Several international indicators are specifically geared to measuring cyber security identity and capability. One of the goals of strategic leadership thus is the continuous monitoring of the status of national cyber capability (as a whole) to understand its current level and to improve the capability.

Fourthly, strategic leadership creates coherence and continuity for Finland’s collaborative efforts at both the national and international level. Strategic leadership gathers all available resources together in order to achieve the set targets.

So in a state level should identify a dedicated national-competent cybersecurity authority – a leader (whether an individual or an entity) who is elevated and strongly anchored at the highest level of government to provide direction, to coordinate action, and to monitor the implementation of the cyber security strategy. Such a national competent cybersecurity authority should also act as management entity to define and clarify roles, responsibilities, processes, decision rights, and the tasks required to ensure effective implementation of the cyber security strategy. This includes establishing performance targets for various ministerial or governmental departments, institutions, or individuals responsible for specific aspects of the cyber security strategy and subsequent development program, coordinating activities and preparedness, and extensive leadership in incident management. This approach may require additional policy or legal structures to empower them to perform their missions. Given the fact that cybersecurity intersects many different issue areas, it is important to ensure that the national-competent authority can involve and direct relevant stakeholders (ITU, Citation2018).

As a basis for assessing management models, below illustrates the operating environment. As public, private and NGO actors have been used organizations, functions and associations identified in Finland’s Cyber Security Strategy and its Implementation Programme.

2.2. Strategic leadership of cyber security – an analysis based on research

According to our 2016–2017 research, comprehensive cybersecurity covering and integrating the various cybersecurity functions of society, the vagueness and lack of strategic cyber security leadership were strongly highlighted in the research. In conclusion of the research, clarifying and reinforcing strategic leadership is crucial to ensuring Finland’s vision for cyber security (Lehto et al., Citation2017).

The challenges of cyber security management are particularly prominent at the level of strategic leadership. The challenges of the current state are reflected in the views brought up in several of the interviews conducted for the study concerning (1) clear and concrete proposals for strategic leadership structures of cyber security, and (2) the need to discuss the importance of this issue and the required measures with integrity and avoiding any ambiguity. According to the experts interviewed for the research project two basic problems have been identified at the level of strategic leadership:

The number of actors is large, and for this reason, the strategic leadership of cyber security is fragmented and lacks clear leadership. The ministries carry out the strategic leadership of cyber security independently in their own sectors, and consequently overall strategic leadership is lacking, and the activities are to a great extent siloed in the various administrative branches.

No effective cooperation structure exists at the level of strategic leadership of cyber security. This is partly linked to the first problem. The ministries look at cyber security on the basis of their own needs, losing sight of the wider societal perspective, and the aforementioned objectives defined for strategic leadership are not achieved.

The interviews conducted for the study indicate that the strategic leadership of cyber security must be recognizable to avoid a situation where administrative branches have no leadership and the requisite measures cannot be carried out. In the current situation, strategic leadership is expected to take care of itself, even if this is not necessarily the case. In the current state, interdependencies between different actors in society have not been described. Once the relationships between organizations and functions have been described, the impacts decisions will have on societal functions can be anticipated. Experts believe that research to study the interdependences is needed as soon as possible. Identifying the cooperation partners, actors producing information and the entire cyber observation system would be important first steps toward a genuine cross-cutting security strategy for entire society. The interviews conducted for the study indicate that discretion will be needed concerning a body/function that takes care of coordination across organizational boundaries to ensure that its actual role does not remain illusory and that it does not add to the workload unnecessarily.

In terms of effective strategic leadership of cyber security, it is vital to identify structures that can respond to the operative requirements set by the environment. Typical features of the cyber environment are an accelerating rate of change, a phenomenon-based approach, complexity and, in part, unpredictability. The interviewees stressed that the pre-sent model of strategic leadership is unable to respond to the ever-faster rate of change. The loop formed by gathering information on which decisions are based, making the decision and implementing it is currently too slow. ”As the vulnerability of society increases it is necessary to be able to rapidly start managing sudden disturbances in the cyber domain”. According to the interviewees, the present model does not respond fast enough to incidents.

According to the experts interviewed for the study, a precondition for the current role of the Prime Minister’s Office is that existing forms and practices of cooperation for responding to an urgent crisis in the cyber environment have been negotiated. It is almost never possible to negotiate on measures in urgent crisis situations, and a mandate and operating models tested as part of the preparedness process should exist for taking action. The Finnish Communications Regulatory Authority’s National Cyber Security Center has established methods for managing incidents together with private sector actors. Rather than on authority, this procedure is based on cooperation, in which the Cyber Security Center serves as the contact point.

The interviews conducted for the study indicate that strategic leadership is based on building and maintaining trust. Even today, deep trust and doing things together are the basis for thwarting cyber threats. Fundamental trust has enabled exceptionally good cooperation between different actors in Finnish society, and this cooperation has long traditions in Finland. The National Cyber Security Center is a good example of how trust achieves more than obligation. So far, keeping the cyber environment safe has been based on identifying key actors and conducting negotiations between them, rather than cyber security management structures. The interviewees even questioned the strategic leadership of cyber security due to factors stemming from the operating environment. A systematic action model, but the issue of the strategic leadership of government cyber security was found challenging.

According to the experts interviewed for the study, a strategic leadership model of cyber security should be created, as currently there is no strategic leadership of cyber security.

2.3. Strategic leadership of cyber security development

New technologies challenge the current legislation and raise ethical questions concerning such issues as cyberattack capability, autonomous vehicles, artificial intelligence and augmented reality. The advancing technologies mean that the cyber environment is in constant flux which, according to the interviewed experts, hampers the creation of permanent and straightforward operating models. Diversification of activities, group processes and a correct type of balance between the mechanical and organic nature of activities are means for managing this complexity.

Based on the interviews, research literature and an analysis of the reference countries, successful strategic leadership of cyber security requires:

Effective legislation,

Sufficient powers,

Links to political decision-making,

Capabilities and expertise, and

Financial resources.

The interviewees identified leadership capability as a success factor in the strategic leadership of cyber security. The experts referred to historical cases where decisions were made on the wrong grounds without understanding their impacts on our society. Strategic leadership should facilitate interaction between the state’s political leadership and, on the other hand, those responsible for operative activities, ensuring that both parties understand each other and that their actions are coherent.

3. Models for the strategic leadership of cyber security

Alternative models for the strategic leadership of cyber security in Finland were produced in the research. The five models presented below are based on the views of personnel with managerial roles and experts of the field in the interviews conducted for the study, international evaluations of reference countries, views presented in the research literature/documents as well as assessments made by the authors.

Five models for the strategic leadership of cyber security are presented:

The present model

A national cyber security manager

A national cyber security unit

A strengthened National Cyber Security Center

A Cyber Security Agency.

3.1. Present model

In the present model, cyber security is managed as part of seeing society’s vital functions, and no separate strategic leadership or management process is created for it.

The strengths of this model include its familiarity (management of cyber security is integrated in existing arrangements for incident management) and minor need for rearrangements in the administration. The Finnish (cyber) security actors are relatively familiar with each other, which facilitates information exchanges and smooth cooperation, even if no unambiguous line of command related to cyber security has been defined. This model is underpinned by the current legislation.

The model’s weakness lies in its uncertain ability to respond sufficiently fast to large-scale cyber-attacks or incidents and to produce anticipatory strategic analysis data essential for preparing for ever changing cyber threats. The present management structure cannot be considered optimal in terms of the coordination of preparedness, identification of strategic goals or strengthening of the national cyber security identity. The present model does not provide sufficient guidance for the cyber security preparedness of the administrative sectors, businesses and the NGO, or produce sufficiently centralized capabilities for strategic analysis to support the production of situational awareness. In the present model, shortcomings are associated with the identification and development of national cyber self-sufficiency. No close link between political decision-making and strategic leadership of cyber security, which was stressed in international comparisons, is manifested clearly.

3.2. A national cyber security director

In this model, the role of the top director of cyber security is set up in the Prime Minister’s Office or, alternatively, a ministry or an organization with a key role in cyber security.

A key strength of this model is a clear chain of command in cyber security work: the ap-pointed cyber security manager would coordinate, lead or support cyber security work in all situations. Management would also take place close to political decision-making and steering. In this model, however, a single person would be appointed to direct an area with no dedicated resource allocation.

In this situation, management across administrative boundaries would be challenging, as resource allocations and management systems would be specific to each administrative sector. As another weakness of the model may be considered the concentration of disproportionately great power and responsibility to a single person. As strategic leadership com-prises an extensive set of tasks, the possibilities of a single person carrying out all the specified tasks may be questioned. If the cyber security manager’s role is limited to lose coordination, the management of both preparedness and incident response will remain cursory. In a rapidly escalating incident, fast and effective links should be in place between the strategic leadership and operative actors, and each party should have clear-cut powers.

3.3. A national cyber security unit

The model of a national cyber security unit is like the national cyber director model. A separate cyber security unit subordinate to the cyber security director would be set up with capabilities for directing, developing and supporting national cyber preparedness and for promoting the realization of the national cyber security vision in a broader sense.

The strengths of the cyber security unit would include its placement close to political decision-making and its ability to direct and develop cyber security activities cross-administratively. From the point of view of management, this can be considered a relatively agile and centralized model, in which the manager is supported by his or her own unit in per-forming a large range of tasks. In reference countries, corresponding units are placed either in the prime minister’s office or the ministry with general responsibility for security and jus-tice, or similar tasks are handled by the organization that has the overall responsibility for the coordination of national security activities. In this model, the management of cyber security is partly integrated with existing arrangements for incident management, and transition to it would thus result in limited needs to rearrange the administration. This would reduce the workload and ambiguities created by changing the arrangements for comprehensive security.

3.4. A strengthened cyber security center

In this model, the National Cyber Security Center would be placed under the steering of a cyber security manager, and its operative competence and powers would be complemented with capabilities for strategic analysis. The Center’s situational picture function would be reinforced with strategic analysis capabilities with the aim of producing situational awareness in support of strategic decision-making. The Center would be co-located with the cyber security manager, and it would work in close cooperation with the Government’s Situation Center. The Situation Center would continue to perform the task of providing a situation-al picture for the entire Government and all administrative sectors.

The strengths of this model include the proximity of strategic and operative actions, a clear line of command and a straightforward approach, which would translate as agility in deploying capabilities, thus serving the maintenance of strategic stability while enabling action in unexpected situations. Transition to this model would require limited changes to existing comprehensive security arrangements, including more specific arrangements for cross-administrative cooperation as the Cyber Security Center takes on its new role. Significant additional resources would also have to be allocated to the Cyber Security Center.

The weaknesses of this model would include a fragmentation of cyber security functions and the fact that various functions would remain in different administrative sectors. It is also likely to take time before the Cyber Security Center’s reference groups (current and future ones) adapt to its new role.

3.5. A Cyber Security Agency

This model is based on setting up a Cyber Security Agency, which would handle the strategic leadership of cyber security and cyber security functions.

In the agency model, key cyber resources of the central government can be combined into an effective whole, through which the efficiency of both cross-administrative cooperation and collaboration with businesses can be improved. This model would provide an improved ability to respond to changes in customer needs and the operating environment, develop and strengthen the strategic steering of cyber security, and obtain synergy benefits. It can also improve the productivity and, more particularly, the impact of the administration through more diverse and effective resource use.

The weakness of this model is the partial transfer of cyber security functions away from the administrative sectors, with the resulting losses of knowledge of and expertise in the sectors’ special features. To create the Agency, broad-based reforms of the existing administrative structures, modifications to the line of command and responsibilities, and adequate resource allocation would be needed. Administrative friction would undermine the efficiency of the activities during a transition period until the new operating model becomes established.

4. The solution to a new strategic cyber security management model in Finland

According to our cyber security report 2017, Finland is currently lacking a long-term political will and management model for building the country into a cyber secure digital society. As a result, the administrative branches operate in their siloes and define their objectives and operating models based on their own needs and capabilities. Studies and reports have found that the country’s ability to defeat serious and extensive attacks is today weak due to shortcomings in the observation capability and situational awareness and a lack of clear national management model (Lehto et al., Citation2017).

In its plenary session on 3 October 2019, the Government adopted a resolution on Finland’s cyber security strategy. The Finnish Cyber Security Strategy 2019 sets out the key national objectives for the development of the cyber environment and the safeguarding of related vital functions (Security Committee, Citation2019).

In the new strategy the three strategic guidelines are the following: international cooperation, better coordination of cyber security management, planning and preparedness, and developing cyber security competence. The programme will concretize national cyber security policies and clarify the overall picture of cyber security projects, research and development programmes (Security Committee, Citation2019).

According the new strategy the implementation programmes of the 2013 cyber security strategy have been based solely on proposals from actors committed to its development and the partly sectoral work of the competent authorities. Effective cyber security planning requires that the necessary financial resources and cooperation are considered with sufficient precision in each administrative branch. This will be improved by a cyber security development programme extending beyond government terms. The programme will concretize national cyber security policies and clarify the overall picture of cyber security projects, research and development programmes (Security Committee, Citation2019).

The post of Cyber Security Director will be established at the Ministry of Transport and Communications to coordinate the national development of cyber security. The role of the Cyber Security Director is to ensure the coordination of the development, planning and preparedness of cyber security in society. The setting up of this post does not change the cyber security related responsibilities and powers of the ministries and competent authorities. The Cyber Security Director also acts as an adviser to the central government in cyber security related matters. Under his or her leadership, the overall picture and development programme of cyber security will be developed, drawing on the expertise of ministries, the Security Committee and cyber security actors (Security Committee, Citation2019).

The strategy further emphasizes the importance of comprehensive cooperation – Public-Private-Partnership. Cyber security preparedness requires cooperation among various actors in society, the central government and the business community as well as skills strengthening in different sectors. Interdependencies in the digital operating environment require a comprehensive architecture that takes cyber security into account (Security Committee, Citation2019).

The new strategy expands the cyber security perspective by describing the expansion of the threat environment also to the evolving and changing threats that may endanger the vital functions of society, in particular cybercrime, espionage, state intelligence and various forms of hybrid influencing.

5. Conclusion and discussion

Every organization needs information about the environment and its events as well as their impact on the organization’s functions. In order to make the right decisions, decision-makers need to know the basis and consequences of their decisions, how others will react to them and what risks are involved. All decision-makers must therefore possess sufficient situational awareness and understanding, which is instrumental in timely decision-making and operations. Situational awareness and understanding require co-operation and competence which enable decision-makers to comprehensively monitor the operating environment, to compile, analyze and disseminate information, to identify research needs and to manage networks.

With the national level strategic cyber security leadership buy-in, it will be easier to institutionalize the idea that cybersecurity is a priority for the whole society and enable efficient use of national resources (NARUC, Citation2018).

In the research, the management models proposed by the research project have been described at the level of principle. Our proposed models contain risks, the number and impacts of which are comparative to the scale of the change. The risks may lead to inappropriate solutions when arranging the operations. According to the experts, one perspective to leadership is that the highest level in the national management of cyber security, or strategic leadership, should be assigned to a ministry that has genuine capabilities for leading the activities.

According to our research, a need to centralize the management of Finnish cyber security to the Prime Minister’s Office emerged, in particular (Lehto et al., Citation2017). According to the experts interviewed for the study, due to its direct dialogical connections and role as a function supporting top-level government, the Prime Minister’s Office is better placed to assume strategic leadership than other branches of government or organizations. This model is also linked to EU level cyber security models that the Prime Minister’s Office reconciles with national models. The cyber security work at the Prime Minister’s Office has close links to the Government’s work in this area. The Government serves all branches of administration equally and coordinates their cooperation. Models and practices planned for the Prime Minister’s Office are relatively like those planned for the Government. However, the Prime Minister’s Office has no direct authority over the different ministries, and proposed measures are thus implemented through advice and instructions.

According Government resolution in October 2019 the post of Cyber Security Director will be established at the Ministry of Transport and Communications to coordinate the national cyber security development. A cyber security development programme will be built under the leadership of the director. The management of incidents affecting the cyber environment and cooperation at the operational level will be developed between cyber security actors. In the management of incidents, a general incident management model will be used and, where necessary, the meeting of the heads of preparedness will be used.

The new Finland’s cyber security strategy is based on the general principles of Finland’s cyber security strategy of 2013. The need to update the cyber security strategy has been influenced by significant changes in the operating environment and identified development needs in the work at the national level.

The key question is whether management should be centralised to a single actor or decentralised to several operators. A lack of sufficiently strong and goal-oriented strategic leadership has already hampered the progress of the Cyber Security Strategy Implementation Programme. Solutions for the challenge formed by global cyber security have sought within individual branches of administration, and a national view of the goals is thus lacking. The chosen model can lead to siloed activities, overlooking of interdependencies and lack of coordination. Coherence of activities and a shared situational picture may remain incomplete. The success of the chosen model depends on whether the current operating culture changes.

References

- ITU. (2018). Guide to developing a national cybersecurity strategy - strategic engagement in cybersecurity. Geneva, Switzerland: International Telecommunication Union.

- Juuti, P., & Luoma, M. (2009). Strateginen johtaminen. Kustannusyhtiö Otava. ISBN-13: 9789511236399.

- Lehto, M., & Limnéll, J. (2016, July 7–8). Cyber security capability and case Finland. In Proceedings of the 15th European Conference on Cyber Warfare and Security (ECCWS) (pp. 182–190).

- Lehto, M., Limnéll, J., Innola, E., Pöyhönen, J., Rusi, T., & Salminen, M. (2017). Finland’s cyber security: The present state, vision and the actions needed to achieve the vision. Publications of the Government´s analysis, assessment and research activities 30/2017. ISBN 978-952-287-368-2.

- Lehto, M., Limnéll, J., Kokkomäki, T., Pöyhönen, J., & Salminen, M. (2018, March). Strategic leadership of cyber security in Finland. Publications of the Government´s analysis, assessment and research activities 28/2018. ISBN 978-952-287-532-7 (verkkoj.).

- Limnéll, J. (2016, March). Developing a proportionate response to a cyber attack. Aalto University Publication series: Science + Technology.

- Ministry of Defence. (2015, January 14). Guidelines for developing Finnish legislation on conducting intelligence. A report of the Working Group. https://www.defmin.fi/files/3016/Suomalaisen_tiedustelulainsaadannon_suuntaviivoja.pdf

- NARUC. (2018, October 30). Cybersecurity strategy development guide. Cadmus Group LLC.

- National Audit Office. (2017). Cyber protection arrangements, performance audit report 16/2017. National Audit Office, Helsinki. https://www.vtv.fi/files/5862/16_2017_Kybersuojauksen_jarjestaminen.pdf

- Prime Minister’s Office (2013). Central Government Communications in Incidents and Emergencies, Prime Minister’s Office, Helsinki, 978-952-287-037-7

- Security committee. (2013, January 24). Finland’s cyber security strategy and its background dossier. Ministry of Defence, Helsinki. http://turvallisuuskomitea.fi/index.php/fi/component/k2/14-suomen-kyberturvallisuusstrategia

- Security committee. (2017a, November, 2). Security strategy for society, government resolution. Ministry of Defence, Helsinki. https://turvallisuuskomitea.fi/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/YTS_2017_english.pdf

- Security committee. (2017b). Finland’s cyber security strategy implementation programme 2017–2020. Ministry of Defence, Helsinki. https://www.turvallisuuskomitea.fi/index.php/fi/mcdc/126-suomen-kyberturvallisuusstrategian-toimeenpano-ohjelma-2017-2020

- Security Committee. (2019, October 3). Finland’s cyber security strategy 2019, government resolution. Ministry of Defence, Helsinki. https://turvallisuuskomitea.fi/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Kyberturvallisuusstrategia_A4_ENG_WEB_031019.pdf