ABSTRACT

Public discourse frequently cites the damaging activities of large organisations on global environmental issues, but smaller organisations are rarely, if ever, featured. Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) make up 99% of all businesses in the EU, cumulatively causing more industrial pollution and producing more waste than larger businesses. However, large companies are more likely to address sustainability issues than smaller ones. SMEs need help to change. In a collaborative approach, an online sustainability framework was developed to overcome the barriers contributing to the slow uptake in environmental management in SMEs. The views of owner-managers were incorporated throughout the development process. Best practice environmental tools and training were identified, which were designed in an SME-friendly way and made available online. This paper describes the development of the pilot Sustainability and Eco-Innovation (SEco) toolkit, followed by an analysis of its use. This research finds that a self-led toolkit was not enough to nudge SMEs to address environmental issues, despite being approved by owner-managers at each step.

1. Introduction

Business needs to be part of the solution to reverse the effects of environmental damage and climate change (Heltberg, Siegel, and Jorgensen Citation2009; Sullivan and Gouldson Citation2017). It has been shown that sustainability improvements can play a significant role in slowing down and limiting the damage (United Nations Citation2010; IPCC Citation2018). Firms need to be more accountable and they need to address the vital changes needed to drive improvement (Murray Citation2018; Laurent et al. Citation2019). On a positive note, sustainability is progressing in large corporations and is fast becoming part of their value creation and linked to greater economic revenues (Murray Citation2018; Laurent et al. Citation2019). It was thought that sustainability activities in large companies would lead to smaller organisations becoming greener – particularly those positioned in the supply chains of larger companies (Burke and Gaughran Citation2007; Humes Citation2011; Charlo, Moya, and Muñoz Citation2015). However, there is little evidence of this happening to date. There has also been little public drive for SMEs to become greener (Hoskin Citation2011; Mitchell et al. Citation2011) with headline news on environmental damage typically featuring big companies, but as environmentally conscious consumers are growing in numbers (Scott Citation2019) this may change.

SMEs cumulatively contribute to more environmental damage and produce more waste than all larger organisations combinedFootnote1 (Constantinos et al. Citation2010). SMEs need to be innovative and sustainable to remain competitive but, they are less likely than larger organisations to make transformational changes due to a shortage of resources and limited influence in their supply chain (Côté, Booth, and Louis Citation2006; Constantinos et al. Citation2010; Freel Citation2000; Bititci, Maguire, and Gregory Citation2010). A focus on sustainability through eco-innovation is an appropriate approach for SMEs (Carrillo-Hermosilla, Del Río, and Totti Citation2010; Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014). Research has shown that SMEs who engage in low-risk, eco-innovation practices (e.g. better energy management) engage in further opportunities for improvement (Klewitz and Hansen Citation2011; Demirel and Danisman Ozturk Citation2019).

SMEs can be difficult to engage with on environmental issues (Côté, Booth, and Louis Citation2006; Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014) and this is an under-researched area (Demirel and Ozturk Citation2019; Hampton Citation2018). Business support agencies are having limited success in assisting SMEs with environmental management, nonetheless they are unlikely to make much progress alone (Seidel et al. Citation2009; Hoskin Citation2011; Demirel and Ozturk Citation2019). Some supports are available, but most SMEs are slow to see the importance of sustainability to their business (Mitchell, O’Dowd, and Dimache Citation2010; Demirel and Ozturk Citation2019). The bespoke services that SMEs need have not been forthcoming (Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014).

The FutureSME project was set up in an attempt to address this issue. A European FP7 project; involving a 26-partner consortium, 13 of which were manufacturing SMEs, the aim of the project was to develop sustainable production models. With the purpose of reaching a wide audience of SMEs throughout Europe, an online self-led approach was chosen for the pilot toolkit (rather than an advisor-led approach).

This paper discusses the design and development of an online business sustainability methodology for SMEs, created as part of the Future SME project to prompt eco-innovation. It was carried out in three steps:

(1) A background investigation into

● barriers contributing to the slow uptake of environmental practices in SMEs

● suitable tools to support sustainability improvements in manufacturing SMEs

(2) The development of a self-led pilot sustainability and eco innovation (SEco) framework appropriate for a wide range of manufacturing SMEs

(3) Tracking the use of the online framework.

2. Background

Despite the increasing awareness of environmental problemsFootnote2 (Abramovici, Bellalouna, and Goebel Citation2010; Neely Citation2009; Westkämper, Alting, and Arndt Citation2000), most SMEs are still not engaging in actions to improve environmental performance (Dimache, O’Dowd and Mitchell Citation2009, Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014; Demirel and Ozturk Citation2019). A company is more likely to be sustainable if it is a larger firm (Uhlaner et al. Citation2010). This is possibly because SMEs encounter many difficulties when compared to larger enterprises generally, such as their administrative burden (which can be up to ten times as costly), financial issues, limited resources, access to appropriate information and deficiencies in skills (Mitchell Citation2015, 15–17).

2.1 Barriers contributing to the slow uptake of environmental practices in smes

The issue of sustainability in SMEs has been largely ignored until recently, with little research being conducted in the area (ACCA Citation2013; Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014; Demirel and Ozturk Citation2019). The lack of environmental improvements in SMEs may indicate that SMEs just don’t realise its potential or what to do to access the benefits (Stringer Citation2013; Demirel and Ozturk Citation2019). This slow uptake is a problem. SMEs need to be supported to become more sustainable (ECAP Citation2010; ACCA Citation2013) and these supports should be tailored for them (ECAP Citation2010; ACCA Citation2013). According to a recent study, current supports are inadequate and there is little evidence indicating their effectiveness (Romero-Martinez, Ortiz-de-Urbina-Cria, and Soriano Citation2010; Arbačiauskas et al. Citation2010; Uhlaner et al. Citation2010; Hampton Citation2018). This study has categorised evidence from the literature () into six main contributing factors as the main barriers to engagement:

A lack of awareness of the impact their actions have on the environment (ECAP Citation2010; NetRegs Citation2010; Wooi and Zailani Citation2010)

A lack of knowledge of sustainability including the legislation pertaining to environmental issues (Côté, Booth, and Louis Citation2006; ECAP Citation2010, Fernández-Viñé, Gómez-Navarro and Capuz-Rizo, Citation2010)

A shortage of resources, both financial and human resources, to address the issues (Fliess and Busquets Citation2006; Aragón-Correa et al. Citation2008)

The negative perception that there is no immediate benefit to their organisation (Wooi and Zailani Citation2010)

Insufficient supports and tools to affect change (Arbačiauskas et al. Citation2010; Romero-Martinez, Ortiz-de-Urbina-Cria, and Soriano Citation2010)

Limited research in SMEs and the environment (Labonne 2006, Daddia, Testaa and Iraldoa, Citation2010, ACCA Citation2013; Hampton Citation2018).

To create supports for SMEs, the factors affecting a broad range of SMEs including small and micro SMEs must be taken into consideration (Parker, Redmond, and Simpson Citation2009; ACCA Citation2013). lists the conceptual requirements for the Pilot Framework to overcome the barriers.

Table 1. Conceptual requirements for the pilot framework.

2.2 Suitable tools to support sustainability improvements in manufacturing smes

It has been shown that sustainable business practices and eco-innovationFootnote3 tactics could play a part in addressing the issue in SMEs (including product, process or organisational innovation) (ECAP Citation2010; Klewitz and Hansen Citation2011; Carrillo-Hermosilla, Del Río, and Totti Citation2010). SMEs need a different approach than those designed for larger enterprises to effect change (Côté, Booth, and Louis Citation2006; Seidel et al. Citation2009; ECAP Citation2010; Hampton Citation2018). There is evidence that low-risk changes can lead to radical innovation, such as the adoption of life-cycle thinking, or new manufacturing models (Klewitz and Hansen Citation2011; Demirel and Ozturk Citation2019). A response to a stimulus outside the company is the most likely driver of eco-innovation in SMEs, often from an actor in the value chain, e.g. a large customer (Seidel et al. Citation2009; Hoskin Citation2011; Klewitz and Hansen Citation2014). Other stimuli include NGO involvement, legislation and cost (Williamson, Lynch-Wood and Ramsay Citation2006, Klewitz and Hansen Citation2011; Hoskin Citation2011). See .

Eco-innovation can be described in terms of dimensions, which can involve incremental or radical change. The dimensions are categorised as: (1) design dimensions, (2) user dimensions, (3) product-service dimensions and (4) governance dimensions. Eco-innovations mainly include a mixture of these four dimensions. While the design dimension is the most significant in establishing the environmental impact, the other dimensions are more important for acceptance within its context (Carrillo-Hermosilla, Del Río, and Totti Citation2010).

An analysis of the literature examined the most suitable tools and training to equip SME owner-managers to improve environmental management practices. The most appropriate tools and methodologies that can help eco-innovations are outlined below and summarised in .

Table 2. Tools to support better environmental performance through eco-innovation.

● Life Cycle Management (LCM) tools, to measure environmental impact of products, services and activities, which include:

○ Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for the most comprehensive and widely accepted environmental methodology measurement tool (Westkämper, Alting, and Arndt Citation2000; ISO Citation2006; UNEP Citation2012; Orangebox Citation2013; ADME Citation2014)

○ Life Cycle Costing (LCC) to evaluate the environmental cost of a product or service over its entire life (Norris Citation2001; Kloepffer Citation2008)

○ Carbon Footprinting as the most widely used sustainability measurement method (UNEP Citation2012; Cucek, Jirí Jaromír and Kravanja Citation2012)

● Design for Environment methods (DfE) to guide the design process towards more sustainable products, services and processes (Westkämper, Alting, and Arndt Citation2000; Allen et al. Citation2001; Tukker and Tischner Citation2006)

● Environmental Management Systems (EMS) to provide a framework to guide and implement best practice environmental management (ECAP Citation2010; EMAS Citation2013; EMAS-easy Citation2013)

● Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) assessment and reporting tools to create awareness of the benefits and gain a competitive advantage by articulating sustainable business practices (Russo and Tencati Citation2009; Blowfield and Murray Citation2011; Killian Citation2012)

● Product service systems (PSS) tools to explore new business models (Tukker and Tischner Citation2006, Dimache, Mitchell and O’Dowd Citation2009)

● Tools to audit and measure environmental indicators (waste, water and energy) (Deming Citation1986; Warr and Orsato Citation2008)

● Tools to support environmental legislation compliance (Predescu et al. Citation2010; ECAP Citation2010)

● Eco-Innovation and sustainability training to support all the above (McPhearson Citation2008; SIMPEL Citation2008).

3. Methodology

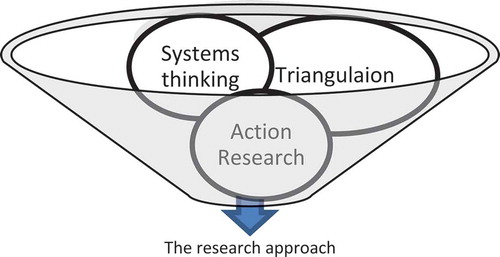

The research approach in this paper is influenced by the broad themes under investigation which span various fields (engineering, business and management). An interdisciplinary method is appropriate to examine the complex research problem. Three elements form the overall research approach (see ); Systems thinking views problems in the context of their internal and external environment and can capture interactions and feedback (Meadows Citation2009; Sterman Citation2002; Maani and Cavana Citation2007; Seidel Citation2011); An action research approach allows collaboration with members of the research setting (such as SME owner-managers) in the development of a solution; and triangulation involves several data collection methods to increase the validity of the process and the conclusions drawn.

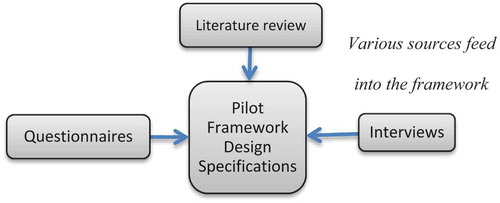

The specifications for the Pilot SEco Framework were drawn from several sources and methods. The triangulation approach () includes a review on environmental best practice in SMEs, followed by online questionnaires. Interviews with SME owner-managers made the quantitative questionnaire data more meaningful. A synthesis of the data was prepared using NVivo.

4. Development and testing of the seco pilot framework

The development process took place over four years. The views of SME owner-managers were considered throughout.

4.1 The development process – design specifications

The tool suitability analysis (in Section 2) contributed to the development of a one-stop-shop Pilot Framework to suit a broad range of manufacturing SMEs. The tables below illustrate a traceability matrix which correlates requirements against proposed design specifications, in this case the relationships to business benefits and eco-innovation dimensions. and lists the design specifications of the Tools and Training. The matrix defines the:

User requirement specification (URS) – the minimum specification description

Functional specification (FS) – guides the appropriate tool selection

Appropriate tools

Eco-innovation and/or business benefit mapped to the requirements

Eco-innovation dimension is categorised into design, user, governance and product service.

Table 3. Traceability matrix – design specification (tools).

Table 4. Traceability matrix – design specifications (training).

4.2 SME owner-managers contributing to the development process

Thirteen SME owner-mangers acted as ‘end-users’ in the development process. No appropriate environmental measurement methods were being used in the firms, even though many claimed to know their environmental impact. Feedback on the SEco Pilot Framework was gathered from them throughout. To gather initial views of SME owner-managers on issues, three surveys were conducted using questionnaires and interviews:

Survey #1 ‘Environmental challenges and opportunities for SMEs’ (see (Mitchell, O’Dowd, and Dimache Citation2010))

Survey #2 ‘An analysis of corporate social responsibility (CSR) in SMEs’ (see (S. Mitchell, A Sustainability and Eco-Innovation (SEco) Framework for Manufacturing SMEs. 2015)

Survey #3 ‘The issues of waste in European SMEs’: (see (Mitchell et al. Citation2011)).

In summary, these investigations found:

Despite reports of eco-efficient practices, environmental management is considered costly by the owner-managers

Compliance to legislation is seen as a burden and a future threat

There are no structures in place to monitor environmental costs

SMEs need to be ‘nudged’ towards good practices

Owner-managers have good intentions, but they are not always acted upon

Many owner-managers did not know where to start

Most of the SME owner-managers claimed to know their environmental impact, but there was no evidence to back up this claim.

4.3 Building the pilot framework and presentation of the individual elements

For the solution to be successful, the barriers to better practices need to be addressed. summarises how the conceptual requirements are met in the Framework.

Table 5. Conceptual requirements and where they are met in the development process.

The SEco Pilot Framework comprises seven tool and training categories listed in . Many of the elements were based on existing tools packaged in an SME-friendly manner. The tools are simple and downloadable. The training material supports the tools, and/or generates awareness.

Table 6. Summary of pilot framework specifications.

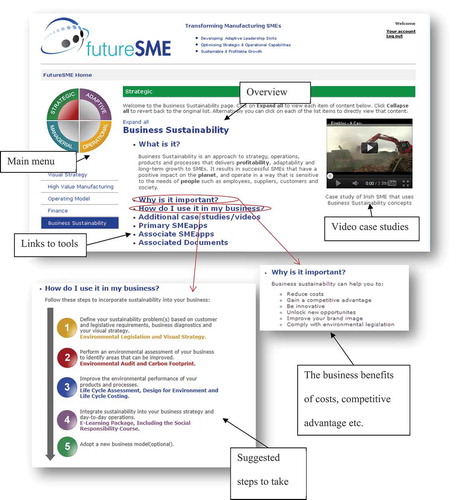

For the Framework to be attractive to SMEs, it highlights the business benefits through eco-innovation. To conceptualise this, the Framework is presented with four key facets: cutting costs, being compliant with legislation, gaining a competitive advantage and finding new business opportunities. maps this structure to the features, recommended tools and training and eco-innovation type to address sustainability. The Framework was presented online, see below () for a screenshot of the webpage.

Table 7. Framing the pilot framework to meet the needs of SMEs.

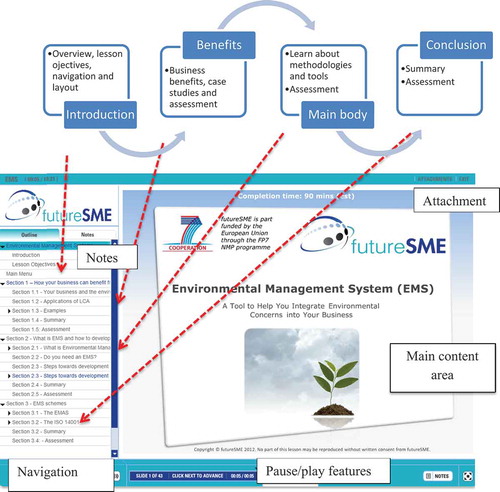

The training modules (eLearning) were created using an andragogic and a heutagogic approach. Common issues reported in relation to eLearning and SMEs were addressed (see ), such as cost, additional support, modified to their requirements and visibility of benefits. The common structure of lessons is illustrated in .

Table 8. How reported issues with eLearning in SMEs were addressed.

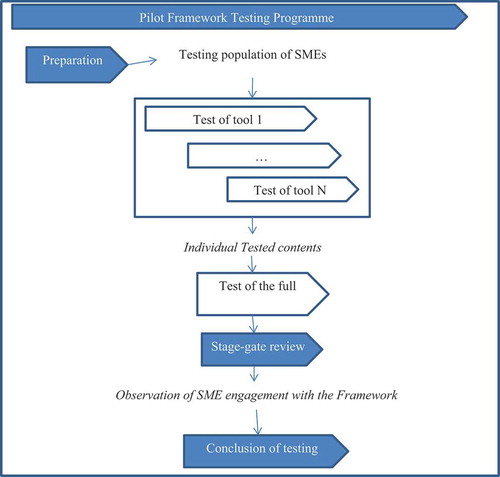

4.4 Testing the seco pilot framework

A three-step testing framework was designed, outlined in . Every eLearning module and tool within the Pilot Framework was tested by the SME end-user group. Overall, the tools were rated highly by the testers in relation to usability and appropriateness for SMEs, and the SEco Pilot Framework was approved by the end-user group. All SME end-users agreed that the SEco Pilot Framework was satisfactory at the time of testing.

The back-end analytics output from the web portal was used to assess user activity. An evaluation of each of these downloads identified that the tools were not being downloaded by the target audience – SMEs. Downloads were mainly from universities, large organisations and environmental consultancy organisations. Only 2% of downloads were from SME companies. None of the 13 SME owner-managers in the Future SME consortium had engaged any further with the SEco Pilot Framework. This was despite the positive feedback and their input during the development stage.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this research was to deepen the understanding of and to develop new insights into the practices of sustainability and eco-innovation in manufacturing SMEs. There is a strong and growing case for all business to embrace sustainability principles. While, SME owner-managers want to improve, there is little evidence that they are engaging. A Framework was developed and tested to overcome the barriers related to the slow uptake of good environmental practices. It is a one-stop-shop approach comprising of an online self-led environmental training programme and a set of environmental tools free of charge that could be accessed at any time. While there was engagement with the tool online from various organisations, there was very little activity by the target group – SMEs.

The lack of voluntary uptake compelled the researchers to identify the gaps in the SEco Pilot Framework. The ongoing engagement over the four-year project gave some insight. For example, during the testing process, some SME owner-managers requested that elements of the Framework be demonstrated to them (rather than do it themselves). They were more interested in something that could relate directly to their business immediately with personal business advantages. The process had been simplified to suit any user with no prior knowledge of the area. However, some owner-managers did not want to spend the required short few minutes reading the instructions – time was precious to them and they wanted to get to the solution immediately. They wanted guidance from someone who knew about their business and was an expert in the area. They were not attracted by the self-led approach.

In conclusion, SME Owner-managers often simply do not know where to start with sustainability and eco-innovation. The online framework did not overcome the issues fully. Providing free learning and tools designed and approved by the end-user group at each step was not sufficient. A formal intervention methodology is needed to support SMEs to engage with sustainability and identify eco-innovation opportunities. The findings indicate that without further guidance and support, an online toolkit is not an effective approach to reach or convince resource-poor SMEs, who are not already influenced by the business benefits and lack the basic skills to start.

Supporting Materials

All the tools and training are available to download on www.futuresme.eu

eLearning Lessons can be accessed online using the links

Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) for SMEs here

Life Cycle Costing (LCC) for SMEs here

Design for the Environment (DfE) here

Product Service Systems (PSS) here

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) for SMEs here

Environmental Management Systems (EMS) for SMEs here

Environmental Legislation for SMEs here.

Acknowledgments

The research was carried out in the Galway-Mayo Institute of Technology as part of the FutureSME project funded by the European Union under the Seventh Framework Programme [Grant agreement ID: 214657].

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sinéad Mitchell

Dr. Sinéad Mitchell is a lecturer in Engineering and a member of the Ryan Institute at NUI Galway as a sustainability researcher. She has a rich industry background which helps the application of theory to practice. Principal research interests include sustainability in business, sustainable manufacturing, eco-innovation and the circular economy.

Paul O’Dowd

Dr Paul O’Dowd, has been a lecturer in the Mechanical & Industrial Engineering Department of GMIT since 1998, and has taught and supported undergraduate and postgraduate students at all levels from Certificate to PhD.

Aurora Dimache

Dr Aurora Dimache, is a lecturer and researcher at GMIT. She is also and environmental consultant and specialises in Life Cycle Assessment methodologies.

Notes

1. In Europe SMEs account for 64% of total industrial pollution and contribute approximately 60-70% of the total industrial waste .

2. Such as climate change, consumption of limited resources, legislative and customer pressure on manufacturers to reduce the impact of their products.

3. Eco-innovation can encompass ‘all innovations that have a beneficial effect on the environment, regardless of whether this effect was the main objective of the innovation’ (Carrillo-Hermosilla, Del Río, and Totti Citation2010).

References

- Abramovici, M., F. Bellalouna, and J. C. Goebel. 2010. “Towards Adaptable Industrial Product-Service Systems (IPS2) with an Adaptive Change Management.” Proceedings of the 2nd CIRP IPS2 Conference 2010, Linköping, Sweden. 467–474.

- “ADME (Agency for Environment and Energy Management, france).” Accessed July 10, 2014. http://2.adme.fr/servlet/KBaseShow?sort=−96&mcatid=22682

- ACCA. 2013. “Embedding Sustainability in SMEs.”Global: Association of Chartered Certified Accountants. Accessed January 18, 2013. http://www.accaglobal.com/content/dam/acca/global/PDF-technical/small-business/pol-tp-esis-v1.pdf

- Allen, D., D. Bauer, B. Bras, T. Gutowski, C. Murphy, T. Piwonka, P. Sheng, J. Sutherland, D. Thurston, and E. Wolff. 2001. “Environmentally Benign Manufacturing: Trends in Europe, Japan, and the USA.” Journal of Manufacturing Science and Engineering (ASME) 124: 908–920. doi:10.1115/1.1505855.

- Aragón-Correa, J. A., N. Hurtado-Torres, S. Sharma, and V. J. Garci-Morales. 2008. “Environmental Strategy and Performance in Small Firms: A Resource-based Perspective.” Journal of Environmental Management 86 (1): 88–103. doi:10.1016/j.jenvman.2006.11.022.

- Arbačiauskas, V., J. Gaižiūnienė, A. Laurinkevičiutė, and Ž. Sigita. 2010. “Sustainable Production through Innovation in Small and Meduim-sized Enterprises in the Baltic Sea Region.” Journal of Environmental Research, Engineering and Management 51 (1): 57–65.

- Averlill, S., and T. Hall. 2008. “eLearning in SMEs in Canada.” In SIMPEL - Improving eLearning Practices in SMEs, 81–85. Brussels: SIMPEL.

- Bititci, U., C. Maguire, and I. Gregory. 2010. Adaptive Capability. A Must for Manufacturing SMEs of the Future. Glasgow: FutureSME.

- Blowfield, M., and A. Murray. 2011. Corporate Resonsibility.” 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brezet, J. C., and C. G. Van Hemel. 1997. Ecodesign: A Promising Approach to Sustainable Production & Consumption. Delft: TU of Delft & UNEP.

- Burke, S., and W. F. Gaughran. 2007. “Developing a Framework for Sustainability Management in Engineering SMEs.” Robotics and Computer-integrated Manufacturing 23 (6): 696–703. doi:10.1016/j.rcim.2007.02.001.

- Carrillo-Hermosilla, J., P. Del Río, and K. Totti. 2010. “Diversity of Eco-innovations: Reflections from Selected Case Studies.” Journal of Cleaner Production 18: 1073–1083. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2010.02.014.

- Charlo, M. J., I. Moya, and A. M. Muñoz. 2015. “Sustainable Development and Corporate Financial Performance: A Study Based on the FTSE4GoodIBEX Index.” Business Strategy and the Environment (John Wiley & Sons) 24 (4): 277–288. doi:10.1002/bse.1824.

- Constantinos, C., S. Y. Sørensen, B. P. Larsen, and S. Alexopoulou. 2010. SMEs and the Environment in the European Union. Planet Sa Denmark: EC DG Enterprise and Industry.

- Côté, R., B. Booth, and B. Louis. 2006. “Eco-efficiency and SMEs in Nova Scotia, Canada.” Journal of Cleaner Production (Elsevier) 14 (6–7): 542–550. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2005.07.004.

- Cucek, L., J. Jaromír, and Z. Kravanja. 2012. “A Review of Footprint Analysis Tools for Monitoring Impacts on Sustainability.” Journal of Cleaner Production 34: 9–20. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2012.02.036.

- Daddia, T., F. Testaa, and F. Iraldoa. 2010. “A Cluster-based Approach as an Effective Way to Implement the Environmental Compliance Assistance Programme: Evidence from Some Good Practices.” Local Environment 15 (1): 73–82. doi:10.1080/13549830903406081.

- Deming, W. E. 1986. Out of a Crisis. Cambridge MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Advanced Engineering Study.

- Demirel, P., and G. D. Ozturk. 2019. “Eco-innovation and Firm Growth in the Circular Economy: Evidence from European SMEs.” Business Strategy and the Environment 2019: 1–11. doi:10.1002/bse.2336.

- Dimache, A., P. O'Dowd, and S. Mitchell. 2009. Threats and Opportunities from Environmental Regulations and Legislation. Galway: FutureSME.

- ECAP. 10 February 2010. “ECAP Seminar “The Green Recipe for Small Business. Brussels: EC.

- EMAS. 2013. “European Commission/Environment/EMAS.” December 19. Accessed January 10, 2014. http://ec.europa.eu/environment/emas/index_en.htm

- EMAS-easy. 2013. “EMAS “Easy” for Small and Medium Enterprises.” Online: EMAS easy. Accessed April 10, 2011. http://www.ecomapping.com/docs/emaseasy/EMAS_EASY_EN.pdf

- Engert, S., S. G. Akhmetova, and L. V. Nevskaya. 2008. “eLearning in Russian SMEs: The Experience of the Perm Region.” In SIMPEL - Improving eLearning Practices of SMEs, 87–91. Brussels: SIMPEL.

- Fernández-Viñé, M., T. G.-N. Blanca, and S. F. Capuz-Rizo. 2010. “Eco-efficiency in the SMEs of Venezuela. Current Status and Future Perspectives .” Journal of Cleaner Production 18 (8): 736–746. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2009.12.005.

- Fliess, B., and C. Busquets. 2006. “The Role of Trade Barriers in SME Internationalisaion.” OECD Trade Policy. OECD Publishing.

- Freel, M. S. 2000. “Barriers to Product Innovation in Small Manufacturing Firms.” International Small Business Journal (SAGE Journals online) 18 (2): 60–80.

- Fussler, C., and P. James. 1997. Driving Eco-Innovation: A Breakthrough Discipline for Innovation and Sustainability. London: Pitman Publishing.

- GHG Protocol. 2011. “Calculation Tools.” Accessed 2011. http://www.ghgprotocol.org/calculation-tools

- Hampton, S. 2018. “‘it’s the Soft Stuff That’s Hard’: Investigating the Role Played by Low Carbon Small- and Medium-sized Enterprise Advisors in Sustainability Transitions.” The Journal of the Local Economy Policy Unit 33 (4): 384–404. doi:10.1177/0269094218778526.

- Heltberg, R., P. B. Siegel, and S. L. Jorgensen. 2009. “Addressing Human Vulnerability to Climate Change: Toward a `no-regrets’ Approach.” Global Environmental Change (Journal) 19 (1): 89–99. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.11.003.

- Hoskin, P. 2011. Why Business Needs to Green the Supply Chain, 16–18. Auckland: University of Auckland Business Review.

- Humes, E. 2011. Force of Nature: The Unlikely Story of Wal-Mart’s Green Revolution. New York: HarperBusiness.

- IPCC. 2018. Global Warming of 1.5°C. Geneva: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

- ISO. 2006. “ISO 14040:2006(E) Environmental Management, Life Cycle Assessment, Principles and Framework.” ISO14040 Second edition 2006-07-01. Geneva: ISO.

- Killian, S. 2012. Corporate Social Responsibility: A Guide with Irish Experiences. Limerick: Chartered Accountants Ireland.

- Klewitz, J., and E. Hansen. 2014. “Sustainability-oriented Innovation of SMEs: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Cleaner Production 65: 57–75. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2013.07.017.

- Klewitz, J., and E. G. Hansen. 2011. “Sustainability-oriented Innovation in SMEs: A Systematic Literature Review of Existing Practices and Actors Involved.” XXII International Society for Professional Innovation Management (ISPIM) Conference. Hamburg: ISPIM.

- Kloepffer, W. 2008. “Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment of Products.” International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 13 (2): 89–95. doi:10.1065/lca2008.02.376.

- Laurent, A., C. Molin, M. Owsianiak, P. Fantke, W. Dewulf, C. Herrmann, S. Kara, and M. Hauschild. 2019. “The Role of Life Cycle Engineering (LCE) in Meeting the Sustainable Development Goals Report from a Consultation of LCE Experts.” Journal of Cleaner Production 203: 378–382. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.05.129.

- Maani, K. E., and R. Y. Cavana. 2007. Systems Thinking and Modelling: Managing Change and Complexity. Auckland: Pearson Education New Zealand.

- McPhearson, M. 2008. “A Systematic Review of the Literature into the Use of eLearning in the Workplace.” In Improving eLearning Practices in SMEs, 11–31. Brussels: UNIVERSITAS-Gyor nonprofit Kft. Brussels: SIMPEL.

- Meadows, D. H. 2009. Thinking in Systems. A Primer. 2nd ed. Edited by Diana Wright. London: Earthscan.

- Mitchell, S. 2015. “A Sustainability and Eco-Innovation (Seco) Framework for Manufacturing SMEs.” PhD Thesis, GMIT, Galway.

- Mitchell, S., P. O’Dowd, and A. Dimache. 2010. “Environmental Challenges for European Manufacturing SMEs.” International Manufacturing Conference IMC27. Galway, Ireland: Proceedings of IMC27.

- Mitchell, S., P. O’Dowd, A. Dimache, and T. Roche. 2011. “The Issue of Waste in European Manufacturing SMEs.” 13th International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium. Cagliari: Proceedings from the 13th International Waste Management and Landfill Symposium.

- Murray, T. 2018. “IPCC Report Reveals Urgent Need for CEOs to Act on Climate.” Forbes. Washington, DC, 09 October. Accessed Jan 10, 2019. https://www.forbes.com/sites/edfenergyexchange/2018/10/09/ipcc-report-reveals-urgent-need-for-ceos-to-act-on-climate/#68a8bc143333

- Neely, A. 2009. “The Servitisation of Manufacturing.” ESRC seminar ‘The Servitisation of Manufacturing’ on 15th January 2009. Bedford: Cranfield University.

- NetRegs. 2010. “NetRegs SME Environment 2009.” netregs.gov.uk. 23 April. Accessed May 17, 2010. http://www.netregs.gov.uk/static/documents/NetRegs/NetRegs_SME_Environment_2009_UK_summary.pdf

- Norris, G. A. 2001. “Integrating Life Cycle Cost Analysis and LCA.” International Journal of Life Cycle Assessment 6 (2): 118–120.

- Orangebox. 2013. www.orangebox.com. Accessed Jan 25, 2013. http://www.orangebox.com/swf/nogreenbull.swf

- Parker, C. M., J. Redmond, and M. Simpson. 2009. “A Review of Interventions to Encourage SMEs to Make Environmental Improvements.” Journal of Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy 27 (2): 279–301. doi:10.1068/c0859b.

- PréConsultants. 2000. Eco-indicator 99, Manual for Designers: A Damage Oriented Method for Life Cycle Impact Assessment. The Hague, Netherlands. Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the Environment.

- Predescu, A., R. D. Vilag, G. H. Ionescu, and I. Predescu. 2010. “The Changes Brought by the Financial Crisis upon the Interaction between the European Union Budget and Small and Medium Sized Enterprises.” Studia Universitatis Babes Bolyai - Negotia 55 (2): 57–69.

- Romero-Martinez, A. M., M. Ortiz-de-Urbina-Cria, and D. R. Soriano. 2010. “Evaluating European Union Support for Innovation in Spanish Small and Medium Enterprises.” Service Industries Journal 30 (5): 671–683. doi:10.1080/02642060802253868.

- Russo, A., and A. Tencati. 2009. “Formal Vs. Informal CSR Strategies: Evidence from Italian Micro, Small, Medium-sized and Large Firms.” Journal of Business Ethics 85: 339–353. doi:10.1007/s10551-008-9736-x.

- Scott, M. 2019. Pressure From Above, Pressure From Below Compels Companies And Investors To Tackle Climate Change. 19 April.

- Seidel, M. 2011. “Towards Environmentally Sustainable Manufacturing: A Strategic Framework for Small and Medium Enterprises.” PhD Thesis. Auckland: University of Auckland.

- Seidel, M., R. Seidel, D. Tedford, R. Cross, L. Wait, and H. Enrico. 2009. “Overcoming Barriers to Implementing Environmentally Benign Manufacturing Practices: Strategic Tools for SMEs.” Environmental Quality Management Journal 18 (3): 37–55. doi:10.1002/tqem.20214.

- SIMPEL. 2008. “Strategies, Models and Guidelines to Use eLearning in SMEs.” In SIMPEL - Improving eLearing Practices in SMEs, 173–200. Brussels: UNIVERSITAS-Gyoer Nonprofit Kft.

- Sterman, J. D. 2002. “System Dynamics: Systems Thinking and Modeling for a Complex World.” Massachusetts Institute of Technology Engineering Systems Division ESD Internal Symposium. Cambridge Massachusetts (USA): MIT. Accessed 2013. http://esd.mit.edu/WPS/symposium2004/esd-wp-2003-01.13.pdf

- Stringer, L. 2013. “New Business Opportunities Driving Sustianability Amonst SMEs.” 3 JanuaryAccessed January 10, 2013. http://www.edie.net/news/news_story.asp?id+23779

- Sullivan, R., and A. Gouldson. 2017. “The Governance of Corporate Responses to Climate Change: An International Comparison.” Business Strategy and the Environment 26 (4): 413–425. doi:10.1002/bse.1925.

- Tischner, U., E. Schmincke, F. Rubik, and M. Prosler. 2000. How to Do EcoDesign? - A Guide for Environmentally and Economically Sound Design. Frankfurt, Germany: Art Books Intl Ltd.

- Tukker, A., and U. Tischner. 2006. New Business for Old Europe: Product-Service Development, Competitiveness and Sustainability. 1st ed. Sheffield, UK: Greenleaf Publishing Ltd.

- Uhlaner, L. M., M. M. Berent, R. J. M. Jeurissen, and G. de Wit. 2010. “Family Ownership, Innovation and Other Context Variables as Determinants of Sustainable Entrepreneurship in SMEs: An Empirical Research Study.” Zoetermeer, The Netherlands: EIM Research and Policy. Accessed May 17, 2010. http://www.ondernemerschap.nl/sys/cftags/assetnow/design/widgets/site/ctm_getFile.cfm?file=H201006.pdf&perId=552

- UNEP. 2012. Towards a Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment. Making Informed Choices on Products. New York: UNEP.

- United Nation. 2010. “UN Framework Convention on Climate Change.” UN. 30 March. Accessed April 21, 2010. http://unfccc.int/resource/docs/2009/cop15/eng/11.pdf

- van Hemel, C., and H. Brezet. 1996. “Ecodesign; a Promising Approach to Sustainable Production and Comsumption.” In Ecodesign; a Promising Approach to Sustainable Production and Comsumption, edited by H. Brezet, 59–68. Paris: UNEP/IE.

- Warr, B., and R. J. Orsato. 2008. Greening the Economy. New Energy for Business. Brussels: INSEAD Social Innovation Centre.

- Westkämper, E., L. Alting, and G. Arndt. 2000. “Life Cycle Management and Assessment: Approaches and Visions Towards Sustainable Manufacturing.” CIRP Annals Manufacturing Technology. Paris: CIRP Annals Manufacturing Technology (Conference Proceedings). 501–522. doi:10.1002/1097-0282(200012)54:7<501::AID-BIP30>3.0.CO;2-8.

- Williamson, D., G. Lynch-Wood, and J. Ramsay. 2006. “Drivers of Environmental Behaviour in Manufacturing SMEs and the Implications for CSR.” Journal of Business Ethics 67: 317–330.

- Wooi, G. C., and S. Zailani. 2010. “Green Supply Chain Initiatives: Investigation on the Barriers in the Context of SMEs in Malaysia.” International Business Management 4 (1): 20–27. doi:10.3923/ibm.2010.20.27.