ABSTRACT

A systemic and integral approach to ‘organisational resilience’ is important if infrastructure providers are going to advance business strategies which contribute to the sustainable development of their regions. What is required is an understanding of resilience which links the development of people as learning agents with sustainable professional practices at all levels of an organisation, including its external partners, its customers and its community. This can then drive business transformation which empowers both a sustainability and a commercial value creation logic. This paper contributes to type resilience discussion by exploring the conceptual space between the notion of learning for resilient agency and the technical resilience required for sustainability in infrastructure services. We do this through a case-study of a water utility in New South Wales, Australia, which has constructed an integral model of resilience as a ‘working theory of change’. Particular attention is paid to the interface between the human systems and the technical systems as a critical ‘missing link’ in the resilience discourse.

1. Introduction

Resilience is a transdisciplinary and complex term which has been applied in the diverse fields of the human, social, natural and engineering sciences. There have been various efforts to integrate these applications, particularly in the context of organisational, community and critical infrastructure resilience where there is a need to make connections between technical, human, social and ecological interests in order to co-ordinate a holistic response to challenges such as earthquakes, flooding, fires or longer term risks such as climate change (e.g. Kozine and Anderson Citation2015; Bruneau et al. Citation2003). As Masterton et al. (Citation2017) argue, ‘national economic growth, social inclusion, environmental health, and community cohesion are dependent of a complex, interconnected and dynamic system of infrastructure. The failure of this system can have catastrophic consequences for wellbeing and resilience’ (Masterton et al. Citation2017: 1)

The purpose of such efforts at integration is to maintain and increase the resilience capacity and capability of a complex system to respond to, and recover effectively from, adverse events and to anticipate and to avoid adversity over the longer term in the context of contemporary socio-political, digital and ecological changes. At the heart of this resilience challenge is the claim that all technical and organisational systems are dependent on human systems and thus on the capability of human beings – as individuals, teams and leaders – to make decisions which are aligned with the requirements of resilience for the whole system in which they operate. This in turn requires individuals to be capable of systems thinking – and the participatory, collaborative and ethical values and processes which underpin it, including a shared impelling purpose, seeing appropriate layers, making interdependent connections, identifying change processes and practicing evolutionary learning (Blockley and Godfrey Citation2017:33).

In this paper we explore the concept of resilience and its practical implications for both human, technical and natural systems with a particular focus on the interface between human and technical systems. We argue that a ‘learning’ interface is a critical ‘missing link’ in the resilience discourse. By learning we mean the process – or journey – through which human beings move from a desire, or purpose to an outcome which fulfils that desire or achieves that purpose. The metaphor of a ‘learning journey’ is useful in theorising and explaining the learning interfaces in complex systems, since it carries with it concepts of change, direction, agency, collaboration and purpose.

We report on a pragmatic and constructivist Case Study of a water utility on the East Coast of Australia which has developed an integral model of resilience as a working theory of change to drive its long-term business strategy. Its desired change was from State A, a traditional business model focusing on the effective and efficient provision of water services to State B, a dynamic, sustainability focused business model through which the organisation would become a ‘valued partner in delivering the aspirations of the region’.

Research into human resilience grew from an original focus in developmental and psychological literature stemming from the works of Garmezy (Citation1971) to include a diverse set of domains including psychological and physical health, education, disasters, organisations, engineering and communities (Lozupone et al. Citation2012; Norris et al. Citation2008; Bonanno Citation2005; Fletcher and Sarkar Citation2013; Rutter Citation1985; Wang, Geneva, and Walberg Citation2015; Wang, Haertel, and Walberg Citation1997; Condly Citation2016; Downey Citation2008; Dalziell and Mcmanus Citation2008; Shin, Taylor, and Seo Citation2012; Fisher and Sonn Citation2002). The concept is based on the recognition that there is wide heterogeneity in human responses to environmental shocks, stresses and adversities: some individuals and communities have a better outcome than others who experience comparable levels of shock, risk or adversity (Rutter Citation2012). Coming from an engineering perspective Norris et al. (Citation2008) concluded that resilience can best be defined as ‘a process linking a set of adaptive capacities to a positive trajectory of functioning and adaptation after a disturbance.’ (Citation2008:131)

Resilience has thus become an increasingly significant and polyvalent term which is used across domains and disciplines in research, policy and practice. It describes the emergent property of some systems which enable them to withstand and/or adapt positively to a range of disruptive events and processes. The literature suggests that resilience is both a ‘process’ as well as an ‘outcome’ of human endeavour – a verb and a noun – and it manifests in personal, social, technical and natural systems. It is a complex and dynamic quality that needs to be apprehended and developed from a trans-disciplinary perspective (Rutter Citation2012; Luthar and Brown Citation2007; Luthar, Sawyer, and Brown Citation2006).

However, even when the focus is on the interdependencies of resilience dimensions in a complex system, such as a city or a community subject to earthquakes, the links between human resilience and the technical, organisational, social and economic (TOSE) dimensions of resilience have not been fully attended to (Bruneau et al. Citation2003; Cimellaro et al. Citation2016). Scholars such as Cimarello et at al (ibid) discuss social-cultural capital as the seventh dimension of resilience in the PEOPLES framework and Norris et al (Citation2008) theorise population wellness, quality of life and psychological wellness as key concepts in community resilience as a set of networked adaptive capacities – however, the actual interface between the human being as intelligent, evolutionary learner and decision-maker and the complex systems in which they operate is left open.

Three of the outstanding challenges in the field of resilience studies are to develop an empirical understanding of those human learning qualities which enable an individual or a team (i) to become jointly and severally resilient and (ii) to behave in a way that leads to the resilient design, delivery, maintenance and decommissioning of the organisational, social or technical systems which they are responsible for and (iii) to behave sustainably in relation to the natural world. This is particularly important in the context of the challenges of climate change and the unprecedented need for behaviour change at scale, both from communities and users of services as well as from corporate organisations. This challenge is radically exacerbated by digitisation which now enables large amounts of complex information to be transmitted in real time – requiring human beings to be able to synthesise, critique, identify, select, re-construct and respond to that information in a way that adds resilience value to the system.

2. Resilience emerges at the interface between systems

The future is intensely digital and intensely human and there are rapidly increasing interdependencies between engineered and human systems as well as between natural and human systems (Woods Citation2015). Contemporary analytics tools and methods now mean that questions posed earlier about the multi-levelled, dynamic and multi-faceted nature of resilience (positive adaptation at cellular and neural levels) can now be modelled enabling the exploration of patterns and relationships between variables, both prospectively and retrospectively (Masten Citation2007). It is now possible to explore resilience as a holistic or a systems concept – an emergent property which arises from the interactions of the many different parts of a system and is significantly influenced by human agency and learning.

It is no longer sensible, for example, to explore the challenge of climate change without accounting for the impact of human behaviour on the world’s natural systems. At the same time, all technical systems are embedded in both human systems and in natural systems – they are designed, created, built, maintained and disposed of by humans, in particular places in the natural world. Thus an integral and transdisciplinary understanding and mobilisation of both personal, social and technical resilience and the impact of human behaviour on the resilience of the natural world is important for successful engineering resilience. In this study we use the term learning infrastructure to describe the human, organisational and digital arrangements which influence the ways in which humans make decisions about the technical business practices of their organisation, community or region. Technical practices refer to the ways in which a water utility company goes about its business, which includes but is not limited to purely engineering solutions (Crick Citation2017).

The critical interface between human systems and technical systems is the conceptual focus for this paper and the space for the articulation and design of a learning infrastructure. Living beings operate around points of critical activity at the boundaries of distinct systems – and the nature of activity at these critical transition points is sometimes called ‘criticality’ or ‘critical activity’ and whilst this has been explored to some extent in biological and cognitive systems there is no well-grounded theory about what general principles might influence this behaviour in living complex adaptive systems (Aguilera and Bedia Citation2018). Aguilera and Bedia (ibid) suggest that for embodied agents this may happen through learning – responding to information whilst interacting with their environment. Learning for resilient agency is suggested as such a critical human property which will influence how individual human agents absorb data and information within their context and interact with it and each other in order to adapt and change towards a desired outcome. As an agents’ cognitive capability becomes increasingly sophisticated i.e. they become self-aware, and interact through language, the range and type of possibilities for social emergence increases, the dimensions of phase space are non-constant because agents define and redefine the phase space as a function of their reflexive distinctions and the dimensions of the phase space are derived through the self-distinguishing characteristics of the agents and are influenced by their distinctive behaviour (Goldspink and Kay Citation2009).

3. Learning and innovation are drivers of resilience

Bersin et al. (Citation2017) study of human capital trends identifies the need for a radically new set of digital business and working skills for the organisation of the future, and the most important of these trends is the agility of organisations to replace structural and siloed hierarchies with networks to provide ‘always on’ learning experiences that enable employees to learn what they need to, when they need to, quickly and easily on the job (Bersin, Citation2017). Deloitte describe these and other changes as ‘seismic’ in the world of business and refer to them as constituting a ‘paradigm shift’ brought about by the digitisation of the Fourth Industrial Revolution (Schwab Citation2017). The sort of learning required in this context is highly personalised, digitally enabled, self-directed, problem focused and applied, and it is popularly referred to as Learning 4.0 (Fisk Citation2014). When combined with the World Economic Forum’s identification of complex problem solving, critical thinking and creativity as amongst the top ten most desirable skills for the future workforce (World Economic Forum Citation2016) it is clear that the human-technical interface and the need for an integrated understanding of resilience as the ability of a system to learn its way forwards in a positive trajectory of change, is of pressing importance. Conversely, the success of a business strategy to achieve the resilience of, say, an infrastructure service is dependent upon the ability of the people within that organisation to develop the personal qualities and characteristics of adaptive, agile learners and the cognitive, affective and volitional capabilities to generate new knowledge on the job, which is framed by systems thinking approach in problem identification, problem structuring, ideation, solution selection, implementation and evolutionary learning throughout the project lifecycle.

4. Learning infrastructures

Rayner and Van Decker (Citation2011) suggest that business processes are not only carriers of the operational business but also of its changes – and how those changes take place depends on the response of users, in our words, their capacity for learning on the job. They say: ‘in systems of differentiation and innovation, process agility may be key to achieving business value, so any assessment of these applications should include the way in which the process model can be adapted by users (Citation2011:6).

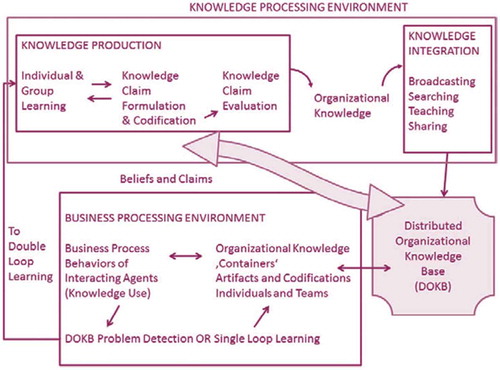

Stary (Citation2014) develops this and argues that Knowledge Management and Knowledge Life Cycle models are key elements of business processes which are unique to an organisation and create opportunities for competitive advantage and business transformation through knowledge co-generation. They enable a company to intelligently plan for and facilitate improvements and also new knowledge co-generation. He utilises Firestone’s (Citation2003), Firestone and Mcelroy (Citation2005)) Knowledge Lifecyle Model as an exemplar and this is presented in below:

Stary (ibid) draws effectively on this model to explain how a dynamic digital knowledge-base in an organisation can facilitate and enhance both single loop learning and double loop learning (Bateson Citation1972). Single loop learning leads to new knowledge and know how generated in operational business processes, such as learning how to identify and solve problems, or implement and improve, while pursuing business as usual. Double loop learning leads to new knowledge which is innovative and transformative – and it happens when people reflexively identify business challenges, step back from business as usual, problematise, re-conceptualise, ideate, prototype and test and thus ‘learn their way forwards’ to a novel solution, which fuels the business transformation process (Argyris and Schon Citation1978). In the case of an organisation intent on becoming resilient, this process of learning to do things differently is critical.

Stary rightly argues that coupling the knowledge processing environment (double loop learning) with the business processing environment (single loop learning) is key to successful organisational learning and requires a dynamic digital knowledge base. In our view, this is a key aspect of a critical resilience interface. He highlights the exchange patterns amongst stakeholders and the management of values in such a ‘coupled’ organisation, referring to organisational structures as ‘social inter-actors’ and ‘observable patterns of behaviour’. He proposes that the Knowledge Lifecycle model is exemplary because (i) it carries substantial values which can lead to profound change (Senge et al. Citation1999; Golden Citation2004; Peschl Citation2019, Citation2007) (ii) it recognises complexity in systems and (iii) encourages ‘phronesis’ – which is context sensitive practical wisdom (Nonaka et al. Citation2014) as opposed to solely episteme – context independent knowledge or techne – the practical skill required to do something.

In our view, Stary’s analysis focuses on only one aspect of the learning infrastructure challenge – that is the effective encounter by individuals and teams with the data, information and relationships relevant to solving problems that matter and the sort of values networks and digital infrastructure which enables that. This is necessary but not sufficient to drive the sort of profound changes required by the sustainability agenda. Such digital knowledge capabilities are only useful in so far as they are used effectively by human beings: individuals and teams do not engage in the inevitable discomfort of learning and therefore personal behaviour change unless they have a reason to do so. A sense of personal purpose and the agency to pursue and achieve that purpose is a pre-requisite for doing things differently and for sustainable behaviour change. In an organisation, personal purpose and agency aligned with an impelling transformative business purpose is key to significant organisational change, such as that required for a business to become intentionally resilient.

Human resilience is thus about (i) agency and shared purpose as well as (ii) an effective encounter with the data, information and relationships relevant to solving problems which enable that purpose to be achieved. These two foci are critical for understanding the interface between human and technical systems. In simple terms, it is about being resilient and about resilient behaviour focused on a shared and impelling purpose.

For an individual, resilience is about positive adaptation to risk, uncertainty and challenge – reflexively responding by seeking to understand the situation, identifying a way forwards as a purpose and intentionally navigating towards that chosen outcome. Risk, uncertainty and challenge can be framed as an opportunity for change, for growth, mastery, autonomy and meaning making rather than passively ‘doing what has always been done’. This reflective agency is achieved through self-directed learning which requires particular habits of mind and is sometimes described as ‘learning power’.

Drawing on Seigel’s approach to interpersonal neurobiology (Citation2012) we have previously described the development of learning power as

‘the embodied and relational process through which we regulate the flow of energy and information over time in order to achieve a particular purpose’ (Citation2015:121)

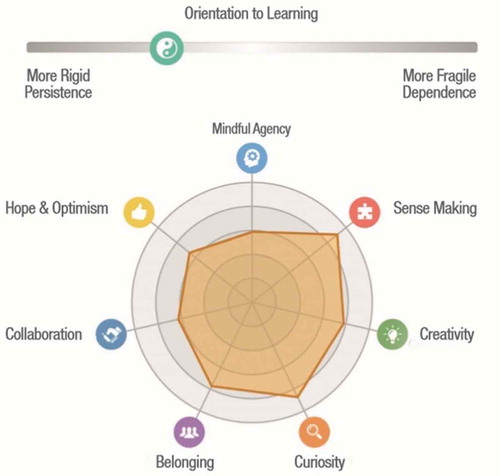

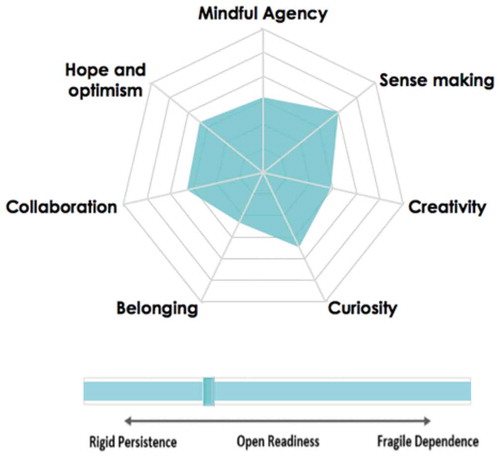

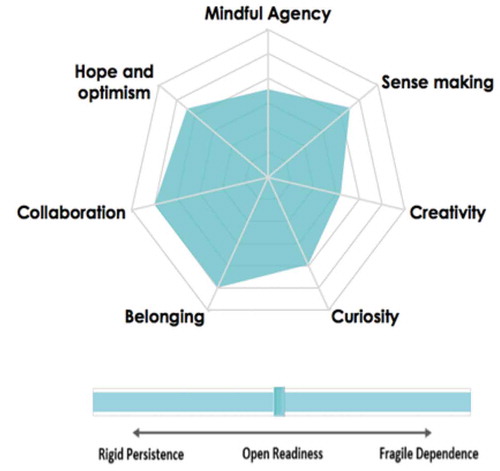

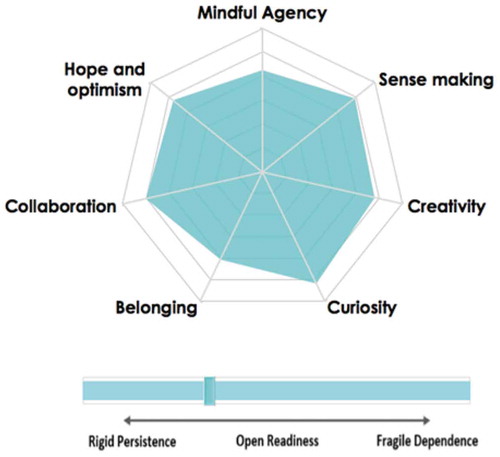

The evidence, based on successive analyses suggests that there are eight dimensions of learning power which are holistic personal qualities through which people develop resilience: Mindful Agency, Creativity, Curiosity, Sense Making, Hope and Optimism, Belonging, Collaboration and Openness to Learning. These qualities are innate, and they are learnable – we can develop them or ignore them. They are sensitive to context and a necessary, but not sufficient, part of a learning journey designed to support innovation and complex problem solving. They are a key to learning-to-learn and to developing personal resilience in the face of challenge, risk and uncertainty. A description of each learning power dimension is presented in . (Crick et al. Citation2013; Buckingham; Shum and Deakin Crick Citation2012; Lucas et al., Citation2013; Buckingham Shum and Deakin Crick Citation2016; Deakin Crick et al. 2015b, Citation2015; Deakin Crick and Buckingham Shum 2014; Deakin Crick, Stringer, and Ren Citation2014; Deakin Crick Citation2014; Godfrey, Deakin Crick, and Huang Citation2014).

The dimensions of learning power are measured through a self-report questionnaireFootnote1 and the data can be used for immediate feedback for self-diagnosis and the development of strategies for change in the context of specific problem-solving learning journeys. The data derived from the survey questions is an individual’s perception of their typical affect, cognition and behaviour in learning contexts and learning power is described as a cluster of values, attitudes and dispositions rather than explicit knowledge. These operate at the interface of the internal subjective world of tacit subjective knowledge since they provide a framework for self-reflection, and the external world of explicit knowledge since they provide meaningful tools for constructing new knowledge and developing thinking and learning capabilities.

The tool was designed to stimulate self-directed change through providing personal insight, supported by peer or expert learning conversations which focus on enabling the coachee to exercise self-leadership in terms of their own sense of purpose and agency and work towards achieving new knowledge through an innovative learning journey. The feedback of personal data to the individual is immediate and contextual and it is represented in such a way that the individual is encouraged to interpret the data for themselves and to take purposeful action for themselves – rather to label and compare themselves to others (see ) . Coaching relationships provide the most effective vehicle for reflection and action – learning power is embedded in relationships reflected in the eight dimensions and these interactions are also a critical context for change.

The data can also be aggregated and anonymised so that a team can explore its corporate learning power and the implications that has for its success. At a leadership level, data can be aggregated across groups, providing an ‘average’ score for a group – or a set of groups – and a learning quotient for the whole organisation can be identified and used for leadership decision making in terms of cultural and values change.Footnote2 The aggregated scores reflect a dynamic fractal learning capability of the organisation – with the individual agent as the ‘unit of change’.

An integrated business model for resilience needs to account for each individual in the organisation developing the personal capacity for resilient agency as well as the application of that capacity to the development of resilient professional practices, referred to as ‘being’ resilient and ‘doing’ resilience. Both are required in order to develop a resilient organisation, which, by definition, is an organisation that is capable of learning – that has the adaptive capacity to change productively and effectively at every level in response to risk, uncertainty and challenge.

5. Research Design and Approach: the water utility case study

A case study approach was selected as a pragmatic means of exploring the application of learning power to cultural change in a water utility. To explore learning as a phenomenon, it is necessary to conduct research in the context in which that learning is taking place. This is inevitably ‘messy’ and constrained by business imperatives, for example, in this case study in year two the region went into severe drought and this took priority over research. Research in human resilience requires a plural approach to data – since human learning journeys include empirical analytical rationality, interpretive rationality as well as emancipatory rationality (Habermas Citation1973) and data collection and analysis needs to be fit for purpose in order to reflect and study these and the relationships between them.

Thus a pragmatic and constructivist (Baxter Magolda Citation2004) approach to the case study research enabled an enquiry over a period of two years which observed the development of the organisation’s working theory of change and key processes which it identified as important for achieving its desired outcome. The focus was on the ways in which individuals, teams and leadership could develop personal resilience and drive changes which were designed to contribute to the delivery of the new business resilience strategy within their designated area of responsibility.

5.1. The Water Utility

Hunter Water Corporation is a medium sized water utility in the Hunter Region in NSW, Australia which was at an important time in its water planning. Without intervention, population growth forecasts indicated that a major augmentation to supply was likely to be required within the next two decades, even without drought conditions. To deliver a large new source in twenty years it would need to commence approval processes within five years, limiting its opportunities to embrace new technology and deliver more innovative solutions.

Hunter Water set itself an aspirational goal to add ten years to this decision-making timeframe. This would enlarge the window of opportunity to enable the positive impacts which could flow from technological disruption, off-setting the need for a major new source or limiting its size and cost. Technology was changing so rapidly that there was the potential for major changes in how water and wastewater services were delivered at house, community and regional level within a few years. However, Hunter Water was concerned that even if technology advances would be fast enough to make a significant impact on the need for large scale supply infrastructure, they may not be fast enough to allow the community and decision makers to be confident in their performance in the time available for decisions to be made. Large scale infrastructure developments require many years of planning, design, community engagement and approval process, hence the need to grow the window for decision-making. As was often said at Hunter Water at the time ‘we don’t want to find that if only we had waited a few years, we might not have needed to build that new supply infrastructure’.

In order to extend the current five-year window of opportunity by enough years that decisions to commence approval processes would not be taken without allowing time to understand whether positive disruption could overcome the need for major augmentation, at least for the foreseeable future, Hunter Water was developing an integrated water conservation strategy which included more than tripling the rate of investment in leakage reduction, reconsidering the value of benefits in the assessment of water recycling and efficiency schemes which used to be considered uneconomic, working collaboratively with the community to encourage behaviour change in water conservation and building trust in the organisation’s future investment strategies.

Water planning approaches needed to be transformed from the traditional ‘whole of life cost’ basis, which almost always favoured large, centralised infrastructure solutions, to a more adaptive approach in which an appreciation of the value of keeping options open and thereby avoiding the risk of path dependency created by building large, long life assets was introduced. This would require a significant shift in the culture of the organisation, away from a risk reduction, conservative and compliant mind set to one which valued resilience, opportunity, innovation and adaptability – in other words it needed to become a learning organisation. This culture change would not only be required to change the way in which Hunter Water planned its asset investments, but in how it engaged with its communities and partnered with other organisations to enable a systems approach to infrastructure planning and service delivery.

5.2. Resilience at the core: learning with staff, partners and community

Hunter Water’s planning for meeting supply and demand requirements was consistent with its wider approach to achieve water resilience. Infrastructure planning in the water industry has traditionally focused on the robustness of solutions to manage uncertainty and minimise risk. Hunter Water challenged this approach through understanding resilience as a combination of robustness and adaptability – with adaptability understood as learning-for-resilient-agency. Its Water Resilience Programme was designed to remain open to technology and innovations, investing incrementally rather than in early specification of large scale solutions. At the heart of this strategy was a new approach to communicating and engaging with the community where an understanding of how people learn, and therefore change behaviour, was built into the campaign. Under a ‘Love Water’ banner, which aimed to emphasise such learning dimensions as belonging, hope and optimism, rather than predecessor campaigns focused on explaining the water use rules, Hunter Water’s extensive and integrated campaign encouraged curiosity and focused on the positive achievements we can all make together. Such a flexible and resilient learning approach works with learning design principles applied to staff, partners and community and not only works for supply and demand but also for resilience to extreme weather events, climatic changes, and other natural hazards.

Having identified learning-for-resilient-agency as a core capability which needed to be enhanced at all levels across the business, Hunter Water went about (i) capturing baseline data about the ‘learning quotient’ of the organisation and on the basis of that evidence (ii) designing learning processes into business as usual practices for staff, partners and the community which would increase the organisation’s adaptive learning capacity and influence outcomes. In this report we present baseline data about employee engagement, employee learning power and organisational resilience which informed the development of the model and early findings which begin to indicate the success of this strategy. We argue for learning-for-resilient-agency as a driver of individual and organisational adaptation and change – and a key element in a wholistic approach to the development of reseilinece in a complex system.

6. Baseline Data Collection

In order to address this shift of culture an extended problem structuring period followed on from the organisation’s new statement of purpose, with participation from across the business. The problem being addressed was that although the company was a trusted and efficient deliverer of water services it was also seen as ‘compliant’, risk averse, and fear-based in its approach to innovation and change – and this was identified as a critical risk factor for the renewed organisational purpose.

Data were gathered from three surveys, focus groups, interviews and professional dialogue. An employee engagement survey was completed which measured employees’ passion and progress and it was offered to the entire organisation with a 85% completion rate. The second data set was a baseline ‘learning power’ survey taken at the same time of a representative sample of 10% of the employees in the organisation, which captured data about ‘learning power’ and the orientation of individuals towards the new learning opportunities embedded in the risk, uncertainty and challenges of water services in their region. The third data set was an opportunity sample of the resilient organisation survey (Chang et al. Citation2010; Seville et al. Citation2008) which assessed the degree to which people perceive the company to be engaging in behaviours which lead to resilience practices at an organisational level.

6.1. Engagement Survey

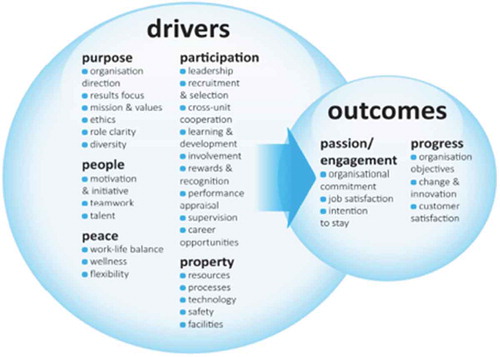

The Voice Project used a 102 item self-report questionnaire to measures 31 variables. These constitute two overarching outcome measures (passion and progress) and five ‘driver’ measures (purpose, property, participation, people, peace). Together these have been demonstrated to be correlated with organisational performance (turnover, profit, goal attainment etc.) (LANGFORD Citation2009). The outcome variables are defined as:

Employees perceptions of their passion for the organisation – the feelings, commitment to and alignment with their organisation.

Employees perceptions of the progress in the organisation – the sense of optimism that they have about the organisations ability to make progress towards its purpose

The remaining five variables are used to indicate the priorities for the organisation to focus on in order to increase passion and/or a sense of progress. For clarity – the lower order variables which constitute passion are ‘organisational commitment’ ‘job satisfaction’ ‘intention to stay’ and those which constitute progress are ‘organisation objectives’ ‘change and innovation’ and ‘customer satisfaction’, see . It is worth noting that the data which demonstrated relationships between these variables and performance are correlation analyses, not predictive analyses.

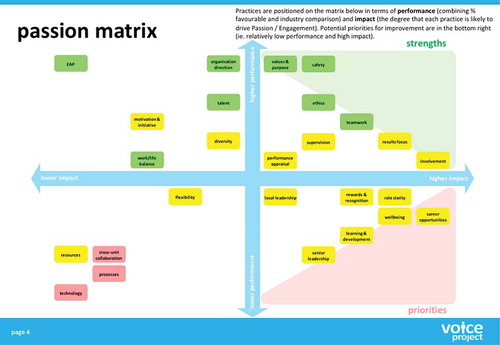

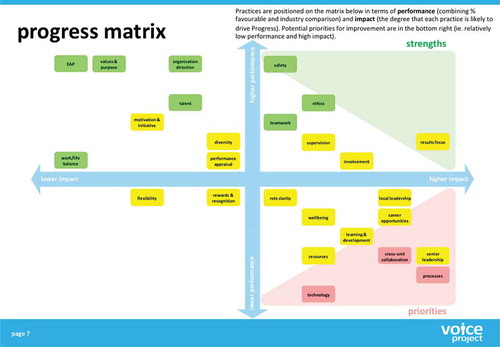

Results show that 80% of employees at this data point reported ‘passion’ and 54% reported ‘progress’. These are reported on separately, in matrices which load the lower order variables onto the passion and progress scores, suggesting priorities for increasing passion and progress. The matrix was organised by a performance axis (the average score on that variable) and an impact axis – the hypothesised impact of that variable on the outcome measure.

As can be seen in , on the passion matrix, the following variables are those which scored the lowest (less than 50% agree, or strongly agree) and which are presumed to have the greatest impact on employee passion: Senior Leadership; Learning and Development; Wellbeing; Career Opportunities and Role Clarity. They thus indicate a focus for action. What is interesting in these results is that although there are high scores for variables such as organisational direction and values and purpose there are still low scores on variables which reflect individuals’ alignment between themselves as employees and the (new) organisational purpose. This suggests a gap between the espoused direction and the capacity of people and teams across the organisation to ‘deliver’ it. That gap represents the critical interface between the human and the technical systems.

On the progress matrix () the following variables scored the lowest (less than 50% agree or strongly agree) and are those which were presumed to have the greatest impact on employees’ sense of progress – their capacity to do the job: Technology; Cross Unit Collaboration; Processes; Senior Leadership; Resources; Career Opportunities and Learning and Development. The items in appendix one (LANGFORD Citation2009) indicate the actual questions asked which resulted in the low score on these variables.

The overall score on ‘change and innovation’ which contributed to the overall progress score and provided evidence of people’s perceptions of how well the organisation manages change and innovation was 32%. This data also highlights the key interface between human and technical systems – and the role that organisational arrangements play in driving progress to close that gap.

6.2. Learning power survey

The learning power survey was a 49 item questionnaire which assessed the respondents perceptions of themselves on the eight dimensions of learning power described above (Crick et al. Citation2016; Deakin Crick and Yu Citation2008 – see Appendix 3 for details). These scales assess an individual’s perception of their cognitive, affective and behavioural approach to new learning opportunities – or situations of uncertainty, risk and challenge. In other words, the extent to which an individual or a team is ready, able and willing to move into uncertainty, risk and challenge, engage in problem structuring and solution selection fit for the newly defined, shared purpose.

A stratified sample of 10% of the population and was identified, and within those strata, employees were randomly selected. This sample is representative of the population and may be generalised. The mean score on each learning power dimension of this sample on this dimension are presented in below. What can be seen from this table is that Mindful Agency and Creativity were the lowest mean scores, whilst Sense Making, Collaboration, Curiosity and Hope and Optimism are the highest. The score on Orientation to Learning indicates a general openness-to-learning with a tendency towards rigid persistence (see Deakin Crick et al. Citation2015 for fuller discussion). The data was returned to each individual in this sample, who then engaged in peer led coaching triads to support change in the context of specific teams and projects.

Table 1. Dimensions of learning power

A cluster analysis was performed on the data set, revealing three distinct clusters, or groups of employees (see for the number of cases in each cluster and for the final cluster centers). The largest cluster (approx. 40%) reported lower levels of learning power on all dimensions (), with particularly low sense of belonging in their learning. Their tendency was to be rigid and persistent in orientation-to-learning i.e. persisting in doing things in the same way. The next largest group were engaged relationally and were open but were passive – or dependent on external factors when facing new challenges (). The smallest group report high levels of learning power, persistence, but a lower sense of belonging ().

These findings suggested that the majority of people and teams in the organisation were passive in their orientation to learning at work – their willingness to engage in self-directed change focusing on achieving the new shared purpose. Some were engaged in the organisation and others did not experience a sense of belonging or collaboration. Interestingly of the group that were ready, open and willing to move into the unknown – there was wide variation in their sense of belonging – possibly because of ‘being outliers’ in their approach.

6.3. The resilient organisation survey

The Resilient Organisation Survey identifies resilience as the ability of an organisation to survive a crisis and thrive in a world of uncertainty. This Resilience Benchmark Tool was designed to help measure the resilience at an organisational level, to enable it to monitor progress over time, and to compare resilience strengths and weaknesses against other organisations within the sector or of a similar size.Footnote3 The dimensions of organisational resilience that it measures are in three categories of organisational attributes: leadership and culture; networks and partnerships and change readiness. These measure scales capturing information about employee perceptions of the following variables: employee engagement, situational awareness, decision-making, innovation and creativity, effective partnerships, leveraging knowledge, breaking silos, internal resources, unity of purpose, proactive posture, planning strategies and stress testing plans. Fuller descriptions of these and the definitions of the scales of each category are presented in Appendix 3.

An invitational sample of 124 employees was selected. The data was collected online, anonymously. The mean scores of each of the scales are presented in below.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of learning power data

Table 3. Final cluster centres table

Table 4. Number of cases in each cluster

As can be seen from above the lowest mean scores were on the Leadership Scale, Breaking Silos, Internal Resources, Leveraging Knowledge and Stress Testing Plans – this suggests that these areas are the most significantly in need of change.

Table 5. Descriptive Statistics of Resilient Organisation Survey

6.4. Synthesis of Findings from survey data

The data from the three surveys presented a pattern and some key themes which iteratively informed the development of the dynamic business model. The strength of the organisation at the point of these baseline surveys was in the unity of purpose and shared understanding and a degree of optimism about the organisation’s new vision. However, overall the practicality about how to go about achieving that vision was not clear and there was a general ‘passivity’ amongst the sample population as well as a lack of ‘joined up thinking’ across traditional business structures.

The personal learning power data suggested that the majority of individuals in the organisation were not resilient agents of their own learning and work narratives – the biggest concern focuses on the low score of (i) mindful agency – the capacity to identify purpose and take initiative to solve problems, and (ii) creativity – the ability to think outside the box, experiment and take risks, drawing on imagination and intuition. The data suggested that whilst there was a good degree of hope and optimism, there were significant numbers of people who did not have a sense of belonging in their approach to innovation and change – interestingly both the cluster that was less engaged in its learning and the cluster that was most engaged. There is a substantial sample of employees who are probably engaged but are passive in relation to change.

The Engagement survey shows that whilst ‘passion’ was generally high, people’s sense of their ability to make progress at work was low – particularly their views about the organisation’s ability to handle change and innovation. The variables which contribute to the development of these two employee engagement factors are also variables which are important in driving the learning culture change. For example, there were low scores on learning and development, cross unit collaboration, career development and leadership. The resilience surveys suggested that leveraging knowledge, breaking down silos, leadership, innovation and creativity and stress-testing of processes were all areas for development.

The data suggested some common themes. Firstly, there was widespread support for the new strategy. Staff across the organisation were enthusiastic about its purpose and supportive of its underlying values – particularly its wider contribution to the region and the ecosystem. It was understood at all levels of the organisation.

Secondly, there was substantial evidence that the new strategy represented a very different mindset or ‘way of going about things’ from what was previously the norm. The changes required of individuals and the ways in which they think and learn together were significant. At the heart of this change was a shift from a ‘top down’ culture, to a networked culture where every member of the organisation would feel able to participate and not be afraid to ‘put themselves and their ideas out there’, risking failure as well as success.

Part of this new mindset was the requirement for participation and collaboration by everyone in the strategic direction of the company – and the willingness to take responsibility for learning and change at every level. This is described as ‘resilient agency’ – each individual develops the personal capacity to be resilient and proactive, rather than dependent on other people, or custom and practice, in order to know how to go about their job. The learning power data in particular suggested that this was a key issue.

Third, the challenge for staff, as evident in all of the data sets, was about the ‘how’ and the ‘what’ rather than the ‘why’. There were ‘blocking factors’ identified, such as the historical tendency for the organisation to operate in silos, the pacing of the change strategies and the challenge for leaders in managing the tension between overall change targets (framed by external factors) and the capacity for teams to keep up.

The ‘what’ of the new strategy was a challenge to the organisation. Despite the leadership team continually reinforcing the fact that the ‘what’ was unknown to start with, and the organisation as a whole needed to ‘learn its way forwards into the unknown’ there was a frequent desire expressed through the data for people to be ‘told what to do’.

7. The integrated Model of Resilience

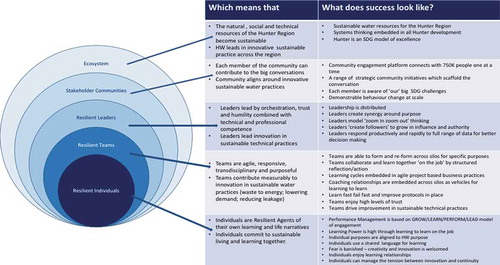

The analysis of the challenge led to an integrated model of resilience which is visually represented through an ‘inside out’ systems model (Sillitto H, Citation2015) locating the organisation in its social and natural environment, identifying different organisational layers whilst recognising the individual at each level as the core ‘unit of change’. Each of these layers is an ‘interacting’ part of the system and at each level attention is focused on the integral development of resilient people (being) as a pre-requisite for the delivery of resilient professional practices (doing), framed around the core, shared, organisational purpose: ‘to enable the sustainable growth of the region, and the life our communities desire, with high quality, affordable services’. The explanations about what this means in practice, and what success might look like formed the beginning of the development of the dynamic business model. The working theory of change is thus: that the organisation will realise its vision for resilience and sustainability through self-directed learning and the development of robust and sustainable practices at every level of the organisation and its community. below presents this visually with practical explanations about what this means for each level.

This model was developed over 15 months of organisational learning, including the analysis of data, consultation, collective struggle (Whalan Citation2012), informed professional experience and challenge from an external Advisory Group. The starting point was the combined risk appetite of the Board, a new CEO and a new direction, expressed in a vision statement that the organisation aspired to ‘be a valued partner in delivering the aspirations of the region’.

8. Change Strategies

The case study reported here is work in progress. Across the business there were exploratory, well-resourced change initiatives – frequently involving external stakeholders including universities – to develop new ways of thinking and prototype new practices in water conservation. These change strategies were defined and developed collaboratively, through workshops, networked teams and through the leadership programme. They were explicitly encouraged a Board level as well as by the executive leadership and they informed the development of a new performance management framework. Key intiatives included:

A leadership programme for successive cohorts of leaders (<85) which integrated learning by doing with leadership development and resulted in a formal presentation by each participant of an innovative business proposition which would contribute measurably to the new strategy and the evidence to support it, together with a recorded ‘narrative of personal change’.

Support for Learning Journeys and the development of learning power through self-directed learning and innovation and the development of learning relationships for all staff, supported through peer coaching relationships.

A community engagement strategy branded under a ‘Love Water’ banner – instead of a rules based approach – as a vehicle for inviting wider learning conversations with the community about water conservation.

An integrated digital utility strategy aimed at using digitisation and technology to scaffold and augment the development of resilient people, an engaged community and resilient water and waste practices.

Key partnerships with service providers and partners in the wider community framed around learning design principles.

Water Conservation initiatives and Wastewater initiatives.

9. Early Findings

Space does not permit a full exploration of the business modelling, its metrics and outcomes. However in year two, the early findings are promising. The engagement survey data in year two showed significant positive change on key variables. For example it showed significant increase on the following variables:

Cross Unit Collaboration +12%

Change and Innovation +11%

Local Leadership take responsibility for their own actions + 10%

Good Use of Technology +10%

A sub group (n = 22) of the baseline learning power sample undertook a second learning power profile in year two and the data was collected as a ‘post test’ sample.

A paired samples T-test was conducted to evaluate the impact of the learning power interventions on staff’s reported scores on each learning power dimension. There was a significant increase in scores on:

Mindful Agency from Time 1 (M =.60, SD = 13) to Time 2 (M = .72, SD = 13), t = −4.2, p = <0005;

Sense Making from Time 1 (M = .75, SD = 11) to Time 2 (M = .83, SD = 11), t = −4.7, p = <0005;

Creativity from time 1 (M = .57, SD = 17) to Time 2 (M = .65, SD = 20), t = −2.4, p = <05;

Collaboration from time 1 (M = .68, SD = 19) to Time 2 (M = .75, SD = 15), t = −2.7, p = <05;

Openness to Learning from time 1 (M = .38, SD = 13) to Time 2 (M = .31, SD = 09), t = 2.3, p = <05; and

Hope and Optimism Time 1 (M = .68, SD = 15) to Time 2 (M = .79, SD = 15), t = −3.1, p = <005.

The change in openness to learning represented a reduction in ‘rigid persistence and a greater openness to new ideas. The Belonging and Curiosity dimensions also increased but did not reach statistical significance.

The changes in the individuals who participated in the leadership group were also significant.

At total of 86 people had completed both a pre and a post test – between 2017 and 2019 and these two data points ‘bookended’ a learning journey change project which was undertaken by those individuals on the leadership programme.

In order to explore whether there was an increase in learning power across time, a paired samples T-test was conducted. The analysis below shows that there has been a statistically significant increase on six out of the eight dimensions of learning power. Curiosity increased but the change did not reach statistical significance. The orientation to learning dimension changed towards the Rigid Persistence end of the scale, but remaining within the mid-range. This this change also reached statistical significance.

Mindful Agency from Time 1 (M = .60, SD = 12) to Time 2 (M = .71, SD = 13), t = −4.2, p = <0005;

Sense Making from Time 1 (M = .73, SD = 12) to Time 2 (M = .81, SD = 11), t = −5., p = <0005;

Creatvity from time 1 (M = .60, SD = 15) to Time 2 (M = .67, SD = .16), t = −3.9, p = <0005;

Collaboration from time 1 (M = .71, SD = 20) to Time 2 (M = .77, SD = 15), t = −3.1, p = <005;

Belonging from time 1 (M = 59, SD = 26) to Time 2 (M = 76, SD = 20), t = −6, p = 0005;

Openness to Learning from time 1 (M = .35, SD = 13) to Time 2 (M = .30, SD = 12), t = 5.8, p = <0005; and

Hope and Optimism Time 1 (M = .68, SD = 14) to Time 2 (M = .79, SD = .12), t = −4.6, p = <0005.

The data indicates that there is a greater degree of collective learning power within the organisation in August 2019 than there was in October 2017. This means people are more likely to be open to the challenges of risk and uncertainty, to ‘think outside the box’, to collaborate and make sense of the complexity of the business and its aspirations.

The original baseline data point suggesting a general ‘passivity’ within the work force – this data suggests that there is now a significantly higher degree of ‘agency’ and ‘self-leadership’ within business. The change on ‘belonging’ has the widest standard deviation around the mean for both time and time two, indicating the greatest variation. However the increased sense of ‘belonging’ to the organisation over time indicates, plus the reduced standard deviation in time two, suggest that more people now identify with the strategic direction of the organisation and have colleagues with whom they are able to talk things through. In the baseline data set, people who were active learners also indicated a challenge in feeling they ‘belonged’.

The Love Water campaign was highly successful in engaging the wider community in the challenge of water conservation. Evidence for this includes an exponential increase on visits to the website, particularly the water usage calculator, and significant media interest and take up of the approach.

From a technical perspective, there are early signs that behaviour change is contributing to the reduction in water consumption. When climate considerations are removed, early modelling suggests that consumers are using 4% less water than they otherwise would have been. In addition to this, there has been a significant increase in the use of new technology in active leak detection and customer engagement, with leakage reduced by nearly 20% in two years.

10. Discussion

Three key issues emerged from the data analysis as critical success factors in the development of the learning infrastructure, each of which operates at the interface of human and technical systems.

The first was the capacity of each individual to engage in change and to take responsibility for the alignment of their own agency and purpose with that of the new organisational purpose, learning on the job and making a measurable contribution towards the new direction. This task was not simple and required focused attention to personal, interpersonal and organisational structural factors at all levels – for example in team culture; in levels of trust between people and in a willingness to move from a dependency culture to one in which individuals and teams were prepared to experiment and ‘step up’ and lead, both themselves and their teams. The development of learning relationships was key to this.

The second was the capacity of the organisation to dynamically leverage new knowledge and professional practices and progressively integrate them into business strategy in a dynamic knowledge processing environment which was both visible and responsive. Replacing the traditional ‘lessons learned’ approach with the need for knowledge curation, to augment discovery, accelerate learning and amplify expertise was evident within the organisation but it also needed to happen across the boundaries of the organisation to include external partners and sometimes the general public. The early findings of the ‘Love Water’ campaign suggested that there is a link between the development of an agile, dynamic learning organisation and behaviour change at scale in the community evidenced in the 4% reduction in water use.

Third, there was a structural challenge of working across traditional silos to create a more agile and networked ‘organisation of the future’, including the capacity for decision making which enabled focus and meaningful prioritisation at all levels. Each part of the organisation needed to focus on the purpose of any project or process in order to understand the range of stakeholder viewpoints and user needs and find ways to include those internal and external stakeholders in improvement or change.

The challenge of measurement and evaluation remains a significant one. The overall success of the new business strategy should be measured with metrics which are fit for purpose. In this case the overall purpose is on the organisation enabling the sustainable growth of the region, and the life our communities desire, with high quality, affordable services’. The measurement of this complex outcome is a challenge – the sustainability logic requires something more than solely a focus on commercial profit whilst the business model identifies interacting processes which are human, organisational, technical, social and ecological. The Water Resilience team and the climate adaptation team in the business developed a parallel and compatible hierarchical process model as a leadership and evaluation tool, a description of which is beyond the scope of this paper. However it overlaps with this model and the two can be combined to represent the whole of the system.

What is clear from the integrated model of resilience developed by the organisation and the subsequent combined hierarchical process model is that any evaluation or measurement model also needs to account for the complexity of the processes involved – and the emergent interactions between them. Each of the third level processes co-influenced the others as well as being hypothesised as contributing up the hierarchy to impact on the overall purpose. For example individual employees openness to learning and innovation impacts directly on strategies to improve the water resilience of the region – with some individuals having more influence than others. Furthermore, any measurements ideally need to be able to account for the levels of uncertainty involved, for example in the range of relevant data types (quantitative, qualitative and narrative) and their relative contribution to performance as well as the degree of confidence that can be attributed to each data point (Hall, Blockley, and Davis Citation1998). The data analysis and visualisation for such a complex measurement model, that can account for the intrinsic uncertainty, is a further challenge which has begun to be addressed in some contexts (Barr Citation2014) through approaches to hierarchical process modelling.

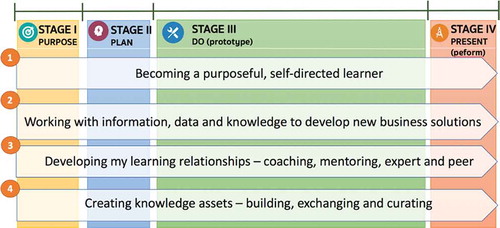

To build on Stary’s model – which focuses on an organisation’s knowledge generation processes, we present a model of Work Integrated Learning Design (WILD) which complements this from the viewpoint of the learning individual or teams who are navigating the process of change. It overlays four flows of human learning processes onto a learning journey framework – i.e. a project which moves reflexively from the articulation of purpose, through problem structuring and planning, prototyping and testing to the arrival at the presentation of ‘new knowledge’ as practical wisdom (Nonaka Citation2014). The processes are (i) developing learning power for self-leadership and personal resilience (ii) implementing and embedding learning relationships (iii) working with data and information to generate new knowledge and (iv) harnessing, curating and sharing collective intelligence. The WILD model is presented in .

Work Integrated Learning Design: flows of personal learning in the context of learning journey projects

11. Strengths and limitations of the study

This study is an initial foray into the field of organisational learning tuned to the development of human resilient agency and as such it offers a novel approach which has merit for further study. It is offered as a partial conceptual and theoretical contribution to the development of an integral model of resilience, with some initial empirical data to support it. Collecting, curating and rendering meaningful data in an accessible form for leaders which is capable of guiding leadership decisions and evaluating success towards an overall reseilince outcome for a business and its community in real time, is a challenge and one which is beginning to be addressed by scholars such as Masterton et al (Citation2017), Norris (Citation2008) and Nonaka (Citation2014) and practitioners such as Field and Look (Field, Look, and Lindsay Citation2017). This study addresses a hitherto overlooked element of such a model.

Scaling this sort of research in order to empirically demonstrate its value to the development of resilience in a whole region would take considerable time, resource and a transdisciplinary approach which is difficult in the contemporary academic/industry context. However, sub processes and mini-case studies such as this one, can begin to build towards such a field of study. There are opportunities emerging in response to the climate crisis which offer new case study application opportunities, such as the need for nature-based solutions for cities, or systems approaches to natural hazards such as flooding, which may make such user-led research more feasible.

Locating such a research agenda in human living systems – organisations and the communities they serve – means that the research will be subject to the vagaries of human systems and is likely to require sustained commitment from a new type of learning professional – located inside and outside of the organisation. The production of data in real time on human processes requires a digital system based on a single view of the learner – or customer – and a dynamic knowledge base requires a digital capability which is integrated with a single view of the learner – or customer – so that the data serves the learning agenda. Efforts are being made to integrate geo-spatial and technical data across regions with modelling efforts tuned to more rapid learning and resilience. Not only does this require people to understand and respond to that data rapidly (i.e. be able to learn and generate new knowledge) but it offers new possibilities for understanding the role of human beings in complex systems as agents of change. For this study, although the surveys were administered on line, the data were collected and curated ‘manually’ and this was a significant limitation.

12. Conclusions

In this paper we have argued that a systemic and integral approach to ‘organisational resilience’ is important if infrastructure providers are going to advance business strategies which contribute to the sustainable development of their regions and include their communities in sustainable behaviour change. Such an approach needs to account for the complexity of the construct and be capable of linking people with professional practices and the development and maintenance of technical resilience at all levels of an organisation, including its external partners, its customers and its community. By focusing on the interface between the human systems and the technical systems of the case-study organisation in the water industry we have argued for a learning infrastructure to inform a business strategy which empowers both a sustainability and a commercial value creation logic. This paper contributes to the discussion by exploring the conceptual and practical space between the notion of human resilience and the technical resilience required for sustainability in infrastructure services. Making learning visible and sustainable at the human-data interface is a critical success factor for achieving a radically different business strategy for water conservation and a more sustainable future for our communities. This learning approach represents an opportunity for framing a meaningful implementation of the UN sustainable development goals.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank colleagues at Hunter Water for their contribution to the ideas presented in this paper, Professors Pam Ryan and Suzanne Wilkinson and Dr Kylie McKenna for their contribution to data collection and the Learning Emergence Partnership for their critique and support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ruth Crick

Ruth Crick is Visiting Professor of Learning Analytics and Educational Leadership at the Connected Intelligence Centre and Institute for Sustainable Futures at the University of Technology Sydney, and was formerly at the University of Bristol, UK, where she held posts for 20 years in Education and Engineering. Following a career in school leadership, she developed a research portfolio focusing on self-directed learning and purpose-led change for individuals, teams and organisations. She is a Director of Jearni, based in the Bayes Centre for Data Science and Artificial Intelligence at the University of Edinburgh, Scotland.

Jim Bentley

Jim Bentley is Chief Executive Officer, Water, in the Department for Planning, Industry and Environment, New South Wales, Australia. He is Professor of Practice in Business and Law at the University of Newcastle, Australia and Visiting Professor in Engineering at University College London, UK. He was formerly Managing Director of Hunter Water Corporation, Newcastle, Australia. He is a senior executive with extensive global experience in infrastructure services, particularly in the water industry, working across both private and public sectors.

Notes

1. For detailed exposition of the structural equation model of the dimensions of learning power and their reliability and validity details which is beyond the scope of this paper please see (Deakin Crick et al. Citation2015) and related papers.

2. For details of learning infrastructure capable of this see www.jearni.co.

3. This questionnaire was developed by the Resilient Organisations Research Programme at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand.

References

- Aguilera, M., and M. G. Bedia. 2018. “Adaptation to Criticality through Organizational Invariance in Embodied Agents.” Scientific Reports 8 (1): 7723. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-25925-4.

- Argyris, C., and D. A. Schon. 1978. Organizational Learning: A Theory of Action Perspective. New York: Addison-Wesley.

- Barr, S. 2014. An Integrated Approach to Decision Support With Complex Problems of Management. PhD, University of Bristol.

- Bateson, G. 1972. Steps to an Ecology of Mind. San Fancisco: Chandler.

- Baxter Magolda, M. B. 2004. “Evolution of a Constructivist Conceptualization of Epistemological Reflection.” Educational Psychologist 39 (1): 31–42. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3901_4.

- Bersin, J. P., B. Schwartz, and J. Van De Vyver. 2017. “Rewriting the Rules for the Digital Age.” 2017 Deloitte Global Human Capital Trends. Westlake, Texas: Deloitte University Press.

- Blockley, D. 2017. Doing It Differently: Systems for Rethinking Infrastructure, Second Edition. London: Institution of Civil Engineers Publishing.

- Bonanno, G. 2005. “Resilience in the Face of Potential Trauma.” Current Directions in Psychological Science 14 (3): 135–138. doi:10.1111/j.0963-7214.2005.00347.x.

- Bruneau, M., S. E. Chang, R. T. Eguchi, G. C. Lee, T. D. O’Rourke, A. M. Reinhorn, M. Shinozuka, K. Tierney, W. A. Wallace, and D. Von Winterfeldt. 2003. “A Framework to Quantitatively Assess and Enhance the Seismic Resilience of Communities.” Earthquake Spectra 19 (4): 733–752. doi:10.1193/1.1623497.

- Buckingham Shum, S., and R. Deakin Crick. 2016. “Learning Analytics for 21st Century Competencies.” Journal of Learning Analytics 3 (2): 6–21. doi:10.18608/jla.2016.32.2.

- Chang, Y., S. Wilkinson, E. Seville, and R. Potangaroa. 2010. “Resourcing for a Resilient Post‐disaster Reconstruction Environment.” International Journal of Disaster Resilience in the Built Environment 1 (1): 65–83. doi:10.1108/17595901011026481.

- Cimellaro, G., C. Renschler, A. Reinhorn, and L. Arendt. 2016. “PEOPLES: A Framework for Evaluating Resilience.” Journal of Structural Engineering 142 (10): 04016063. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0001514.

- Condly, S. J. 2016. “Resilience in Children.” Urban Education 41 (3): 211–236. doi:10.1177/0042085906287902.

- Crick, R. 2017. “Learning Analytics: Layers, Loops and Processes in a Virtual Learning Infrastructure.” In Handbook of Learning Analytics & Educational Data Mining, edited by G. Siemens and C. Lang, 1st ed, pp. 291-307. SOLAR: Society of Learning Analytics Research.10.18608/hla17.025,This is an online networked organisation. ISBN: 978-0-9952408-0-3

- Deakin Crick, R. D., D. Haigney, S. Huang, T. Coburn, and C. Goldspink. 2013. “Learning Power in the Workplace: The Effective Lifelong Learning Inventory and Its Reliability and Validity and Implications for Learning and Development.” The International Journal of Human Resource Management 24 (11): 2255–2272. doi:10.1080/09585192.2012.725075.

- Deakin Crick, R., S. BARR, H. Green, and D. Pedder. 2016. “Evaluating the Wider Outcomes of Schools: Complex Systems Modelling for Leadership Decisioning.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 45 (4): 719–743. doi:10.1177/1741143215597233.

- Dalziell, E., and S. T. Mcmanus 2008. “Resilience, Vulnerability, and Adaptive Capacity: Implications for System Performance.” International Forum for Engineering Decision Making (IFED). Stoos, Switzerland.

- Deakin Crick, R. 2014. “Learning to Learn: A Complex Systems Perspective.” pp 66-86 In Learning to Learn International Perspectives from Theory and Practice, edited by R. Deakin Crick, C. Stringer, and K. Ren. London: Routledge.

- Deakin Crick, R., C. Stringer, and K. Ren. 2014. Learning to Learn International Perspectives from Theory and Practice. London: Routledge.

- Deakin Crick, R., and G. Yu. 2008. “Assessing Learning Dispositions: Is the Effective Lifelong Learning Inventory Valid and Reliable as a Measurement Tool?” Education Research 50 (4): 387–402. doi:10.1080/00131880802499886.

- Deakin Crick, R., S. Huang, Shafi, A. Ahmed, and C. Goldspink. 2015. “Developing Resilient Agency in Learning: The Internal Structure Of Learning Power.” British Journal Of Educational Studies, Routledge 63 (2): 121-160. doi:10.1080/00071005.2015.1006574.

- Downey, J. 2008. “Recommendations for Fostering Educational Resilience in the Classroom, Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth.” Preventing School Failure 53 (1): 56–64. doi:10.3200/PSFL.53.1.56-64.

- Field, C., R. Look, and T. Lindsay. 2017. A Comprehensive Approach to City and Building Resilience. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: AEI 2017 Conference. doi: 10.1061/9780784480502.062

- Firestone, J., and M. Mcelroy 2005. “Has Knowledge Management Been Done?” The Learning Organization, 12.

- Firestone, J. M. 2003. Key Issues in the New Knowledge Management. Boston, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Fisher, A. T., and C. C. Sonn. 2002. “Psychological Sense of Community in Australia and the Challenges of Change.” Journal of Community Psychology 30 (6): 597–609. doi:10.1002/jcop.10029.

- Fisk, P. 2014. GameChangers. New York: Wiley and Sons.

- Fletcher, D., and M. Sarkar. 2013. “Psychological Resilience.” European Psychologist 18 (1): 12–23. doi:10.1027/1016-9040/a000124.

- Forum, W. E. 2016. The Future of Jobs, Employment, Skills and Workforce Strategy for the Fourth Industrial Revolution, Global Challenge Insight Report. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

- Garmezy, N. 1971. “Vulnerability Research and the Issue of Primary Prevention.” The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 41 (1): 101–116. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.1971.tb01111.x.

- Godfrey, P., R. Deakin Crick, and S. Huang. 2014. “Systems Thinking, Systems Design and Learning Power in Engineering Education.” International Journal of Engineering Education 30: 112–127.

- Golden, B. 2004. Succeeding with Open Source. New York: Addison-Wesley Professional.

- Goldspink, C., and R. Kay. 2009. “Agent Cognitive Capability and Orders of Emergence.” In Agent-Based Societies: Social and Cultural Interactions, edited by G. Trajkovski and S. Collins, pp. 89-110. Hershey PA: Information Science Publishing.

- Habermas, J. 1973. Knowledge and Human Interests. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, J., D. Blockley, and J. Davis. 1998. “Uncertain Inference Using Interval Probability Theory.” International Journal of Approximate Reasoning 19 (3–4): 247–264. doi:10.1016/S0888-613X(98)10010-5.

- Kozine, I., and H. Anderson 2015. “Integration of Resilience Capabilities for Critical Infrastructures into the Emergence Management Set Up.” Annual European Safety and Reliability Conference ESREL, September, Zurich, Switzerland.

- LANGFORD, P. 2009. “Measuring organisational Climate and Employee Engagement: Evidence for a 7 Ps Model of Work Practices and Outcomes.” Australian Journal of Psychology 61 (4): 185–189. doi:10.1080/00049530802579481.

- Lozupone, C. A., J. I. Stombaugh, J. I. Gordon, J. K. Jansson, and R. Knight. 2012. “Diversity, Stability and Resilience of the Human Gut Microbiota.” Nature 489 (7415): 220–230. doi:10.1038/nature11550.

- Lucas, B., and G. Claxton. 2013. Expansive Education: Teaching Learners for the Real World. Victoria: ACER.

- Luthar, S. S., J. A. Sawyer, and P. J. Brown. 2006. “Conceptual Issues in Studies of Resilience: Past, Present, and Future Research.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1094 (1): 105–115. doi:10.1196/annals.1376.009.

- Luthar, S. S., and P. J. Brown. 2007. “Maximizing Resilience through Diverse Levels of Inquiry: Prevailing Paradigms, Possibilities, and Priorities for the Future.” Development and Psychopathology 19 (3): 931–955. doi:10.1017/S0954579407000454.

- Masten, A. 2007. “Resilience in Developing Systems: Progress and Promise as the Fourth Wave Rises.” Development and Psychopathology 19 (3): 921–930. doi:10.1017/S0954579407000442.

- Masterton, G., T. Findlay, M. Wright, and S. Smith 2017. “Infrastructure Performance Indicators - a New Approach Based on the Sustainable Development Goals.” International Symposia for Next Generation Infrastructure, 11th −13th September. London.

- MASTMASTERTON, G., T. FINDLAY, M. WRIGHT, and S SMITH, . 2017. Infrastructure Performance Indicators - a New Approach Based on The Sustainable Development Goals. London: International Symposia for Next Generation Infrastructure.

- Nonaka, I., M. Kodama, A. Hirose, and F. Kohlbacher. 2014. “Dynamic Fractal Organizations for Promoting Knowledge-based Transformation – A New Paradigm for Organizational Theory.” European Management Journal 32 (1): 137–146. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2013.02.003.

- Norris, F., S. P. Stevens, B. Pfefferbaum, K. F. Wyche, and R. L. Pfefferbaum. 2008. “Community Resilience as a Metaphor, Theory, Set of Capacities, and Strategy for Disaster Readiness.” American Journal of Community Psychology 41 (1–2): 127–150. doi:10.1007/s10464-007-9156-6.

- Peschl, M. 2007. “Triple-loop Learning as Foundation for Profound Change, Individual Cultivation, and Radical Innovation. Construction Processes Beond Scientific and Rational Knoweldge.” Constructivist Foundations 2: 136–145.

- Peschl, M. 2019. “Design and Innovation as Co-creating and Co-becoming with the Future.” Design Management Journal 14 (1): 4–14. doi:10.1111/dmj.12049.

- Rayner, N., and J. Van Decker. 2011. Use Gartner’s Pace Layers Model to Better Manage Your Financial Management Application Portfolio. Stanford, CA: Gartner Research.

- Rutter, M. 1985. “Resilience in the Face of Adversity. Protective Factors and Resistance to Psychiatric Disorder.” British Journal of Psychiatry 147 (6): 598–611. doi:10.1192/bjp.147.6.598.

- Rutter, M. 2012. “Resilience as a Dynamic Concept.” Development and Psychopathology 24 (2): 335–344. doi:10.1017/S0954579412000028.

- Schwab, K. 2017. The Fourth Industrial Revolution. Geneva, Switzerland: World Economic Forum.

- Senge, P., A. Kleiner, C. Roberts, R. Ross, G. Roth, and B. Smith. 1999. The Dance of Change: The Challenges of Sustaining Momentum in Learning Organizations. New York: Doubleday/Currency.

- Seville, E., D. Brunsdon, A. Dantas, J. Le Masurier, S. Wilkinson, and J. Vargo. 2008. “Organisational Resilience: Researching the Reality of New Zealand Organisations.” Journal of Business Continuity & Emergency Planning 2 (3): 258–266.

- Shin, J., M. Taylor, and M. Seo. 2012. “Resources for Change: The Relationships of Organizational Inducements and Psychological Resilience to Employees‘ Attitudes and Behaviors toward Organizational Change.” Academy of Management Journal 55 (3): 727–748. doi:10.5465/amj.2010.0325.

- Shum, B., and R. Deakin Crick 2012. “Learning Dispositions and Transferable Competencies: Pedagogy, Modelling and Learning Analytics.” Proc. 2nd International Conference on Learning Analytics & Knowledge. Vancouver, BC: ACM Press: NY.

- Siegel, D. 2012. The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are. New York: Guildford Press.

- Sillitto, H. 2015. Architecting Systems: Concepts, Principles and Practice. London: College Publications Systems Series.

- Stary, C. 2014. “Non-disruptive Knowledge and Business Processing in Knowledge Life Cycles – Aligning Value Network Analysis to Process Management.” Journal of Knowledge Management 18 (4): 651–686. doi:10.1108/JKM-10-2013-0377.

- Wang, M., H. Geneva, and H. Walberg. 2015. What Influences Learning? A Content Analysis of Review Literature. The Journal of Educational Research 84: 30–43

- Wang, M. C., G. D. Haertel, and H. J. Walberg 1997. “What Helps Students Learn? Spotlight on Student Success.” Spotlight on Student Success. Philadelphia: Laboratory for Student Success.

- Whalan, F. 2012. Collective Responsibility Redfining What Falls between the Cracks for School Reform. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- Woods, D. D. 2015. “Four Concepts for Resilience and the Implications for the Future of Resilience Engineering.” Reliability Engineering & System Safety 141: 5–9. doi:10.1016/j.ress.2015.03.018.

Appendix One

Passion Matrix

Senior leadership

I have confidence in the ability of senior management

Senior management are good role models for staff

Senior management keep people informed about what’s going on

Senior management listen to ther staff

Learning and development

When people start new jobs here they are given enough guidance and training

There is a commitment to onging training and development of staff

The training and development I have received has improvement my performance

Wellbeing

I am given enough time to do my job well

I feel in control and on top of things at work

I feel emotionally well at work

I am able to keep my job stress at an acceptable level

Career Opportunities

Enough time and effort is spent on career planning

I am given opportunities to develop skills needed for career progression

There are enough opporutnities for my career to progress in this organisation

Role Clarity

I understand my goals and objectives and what is required of me in my job

I understand how my job contributes to the overall success of this organisation

During my day to day duties I understand how well I am doing

Progress MatrixTechnology

The technology used in this organisation is kept up to date

This organisation makes good use of technology

Staff in this organisation have good skills at using the technology we have

Cross Unit Collaboration

There is good communication across all sections of this organisation

Knowledge and information are shared throughout this organisation

There is cooperation between different sections in this organisation

Processes

There are clear policies and procedures for how work is to be done

In this organisation it is clear who has responsibility for what

Our policies and procedures are efficient and well designed

Resources

I have access to the right equipment and resources to do my job well

I have access to all the information I need to do my job well

We can get access to additional resources when we need to