ABSTRACT

Coverage of reading and reading instruction in initial teacher education is highly contested, with the “reading wars” representing decades of debate concerning approaches that should be promoted to teachers-in-training. Empirical evidence strongly endorses explicit and systematic teaching of code-based skills as a starting point, together with strong coverage of vocabulary, syntax, fluency, comprehension, and background knowledge. However, most faculties of education in Australia and other English-speaking industrialised nations have persisted in promoting “balanced literacy” and postmodern constructs, such as “multiple literacies”. We describe the development, delivery, and evaluation of three online short-course programmes for primary and secondary teachers on the science of language and reading and report on feedback from a sample of 945 participants. Quantitative and qualitative data show that participants (the largest subgroup being teachers) attach a high value to this knowledge and its practical applications. Implications for initial teacher education, education policy-makers, and school leaders are considered.

Introduction

There are few areas in the early years of children’s schooling that are simultaneously strongly foundational and highly contested, but reading instruction unfortunately qualifies for this problematic dual status. Since the turn of the twentieth century, three national inquiries, one each in the US (National Reading Panel, Citation2000), Australia (National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy, Citation2005) and the UK Independent Review of the Teaching of Early Reading (Rose, Citation2006), have roundly supported the explicit and systematic teaching of word decoding as a core pillar of initial reading instruction in the first three years of school. This is particularly important in the context of English, which has a relatively dense orthography. Orthographies are the writing systems attached to individual spoken languages, and vary qualitatively (logographic, syllabary, alphabetic) and with respect to complexity. English is a morpho-phonemic language (Moats, Citation2020) which means its writing system encodes both sound (through phonemes) and meaning (through morphemes). Because of its two-thousand-year history of rich borrowings of vocabulary and associated spellings from a wide range of other languages (Horobin, Citation2016), modern English has only a semi-transparent orthography. Some words, such as “mat” are easily decoded by the novice with only rudimentary knowledge of phoneme-grapheme correspondences, while other equally common words, such as “beach” are not. Challenges rapidly increase when children are exposed to the written form of common spoken words, such as “night”, “rough” and “change”, and then again, as they move through the school years and need to be able to decode longer, polysyllabic/polymorphemic words, such as “incontrovertibly” and “unreconditioned”.

As a result of a confluence of complex historical and political events, the dominant reading instruction pedagogy in recent decades in English-speaking nations has been balanced literacy (BL) (Seidenberg, Citation2017; Snow, Citation2020; Spear-Swerling, Citation2018), which has well-documented deficiencies stemming from its weak emphasis on explicit teaching of the English writing code and its eclectic rather than systematic preparation of teachers for instruction which is explicit and follows a scope and sequence (Seidenberg, Citation2017; Snow, Citation2020). BL is impossible to operationally define, because, as one proponent explained, it entails “A bricolage of pedagogies, approaches, and resources” (Cozmescu, Citation2008, p. 6). In defending BL as the dominant pedagogy in Australia, one education academic noted that literacy is “not just about learning to read in the early years” (Riddle, Citation2015). Truisms such as this have not assisted teachers with everyday classroom practice and maintain an unhelpful lack of focus on reading as a discrete, biologically secondary skill (Geary & Berch, Citation2016) that needs to be taught. As noted by Spear-Swerling, BL differs from structured literacy (SL) instruction across at least seven dimensions of teaching, ranging from how decoding is taught, to how more macro aspects of language and literacy, such as sentence structure, paragraphs, and discourse are taught. A key influence on BL is the teachings of the late Kenneth Goodman (e.g. Citation1967, Citation2014), whose theorising about “whole language” has had a pervasive influence on English-speaking education systems over the last 50 years (Seidenberg, Citation2017). Notably, Castles et al., in their landmark (Citation2018) “Ending the reading wars” paper, argued that “it would be valuable to reclaim a term, such as balanced instruction and recast it in a more nuanced way that is informed by a deep understanding of how reading develops (p. 39). Unfortunately, six years on, this has not occurred, though there is evidence in Australia of a shift towards more explicit reading instruction in some jurisdictions.1

It is notable that until recently, BL has maintained its foothold in initial teacher education (ITE) in spite of running counter to the recommendations of three national inquiries mentioned above and not aligning with decades of reading science evidence on optimal instruction (Buckingham & Meeks, Citation2019; Buckingham et al., Citation2013; Rayner et al., Citation2001; Seidenberg et al., Citation2020). As a consequence, teacher knowledge of core linguistic constructs pertaining to reading and reading instruction remains weak, as evidenced by a tranche of international studies in the second decade of this century (e.g. Binks-Cantrell et al., Citation2012; Fielding-Barnsley, Citation2010; Meeks et al., Citation2016; Stark et al., Citation2015; Tetley & Jones, Citation2014; Washburn & Mulcahy, Citation2014). Against this background of weak translation of knowledge into practice, there has, however, been a pleasing groundswell of momentum towards understanding and applying the evolving body of knowledge commonly referred to as the “science of reading” (SoR) in the last decade. This momentum is largely coming from teachers and schools themselves, with many ITE providers continuing to rail against the adoption of “bottom up” skill-based approaches to early reading instruction (e.g. Cambourne, Citation2006; Ewing, Citation2018; Gardner, Citation2019; Henderson & Exley, Citation2012; Riddle, Citation2015), though not offering rationales that are based on testable cognitive psychology models of the reading process and how best to teach it. The focus of BL curricula has been the “what” and not the “how” of literacy pedagogy, with a high premium placed on teacher autonomy (in line with Goodman’s, Citation1967 views), rather than on low-variance instruction and high levels of teacher knowledge about the linguistic and cognitive underpinnings of early reading and reading instruction (Moats, Citation2014; Seidenberg, Citation2017; Snow, Citation2020). It is pleasing, therefore, that national regulatory bodies, such as the Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership (AITSL) have amended their course accreditation guidelines to mandate minimum course content on reading instruction, including the requirement that “Early reading instruction should address evidence-based practice in the following elements: phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, comprehension and oral language” (AITSL, Citation2020, p. 53). Notably, however, the document is not prescriptive about what constitutes “evidence-based practice”, nor on how such elements should be presented to ITE students, or on how they should be supported to teach initial reading at classroom level. It was noted in the 2021 Next Steps Report arising from the Quality Initial Teacher Education Review that “Concerns were raised that the content of some ITE programmes is not based on the latest research and evidence shown to have the greatest impact on school student outcomes. These concerns are longstanding and have been raised in previous reviews” (p. 39). Subsequently, in 2023, the Strong Beginnings Report of the Teacher Expert Education Panel recommended the implementation of an independent verification process to ensure that the 2020 AITSL standards are in fact translated into practice across institutions. The Strong Beginnings Report also recommended that ITE programmes consistently and coherently cover the following four core content domains: the brain and learning; effective pedagogical practices; classroom management, and responsive teaching.

Within this broader policy context, the School of Education at La Trobe University, Victoria, Australia is undergoing a pedagogical transformation that has commenced with reading instruction and is now extending to other curriculum domains, in the broader context of the science of learning. Specifically, our establishment of the Science of Language and Reading (SOLAR) Lab in 2020, has provided a platform to upskill practising teachers (and allied health professionals, literacy coordinators, and school leaders) on the evolving body of knowledge collectively known as the SoR and to refresh reading instruction content in our pre-service programmes. The SoR has been defined by The Reading League (Citation2021) as:

… . a vast, interdisciplinary body of scientifically-based research about reading and issues related to reading and writing. This research has been conducted over the last five decades across the world, and it is derived from thousands of studies conducted in multiple languages. The science of reading has culminated in a preponderance of evidence to inform how proficient reading and writing develop; why some have difficulty; and how we can most effectively assess and teach and, therefore, improve student outcomes through prevention of and intervention for reading difficulties.

In 2020, we (authors 1 and 2) created three fully online short courses to bring the SoR directly to teachers, via flexible and accessible learning. By flexible, we refer to the fact that participants can engage with the short courses synchronously or asynchronously (or via a self-directed hybrid approach). A detailed description of the programmes is provided below. Our pilot evaluations of the first three short courses yielded a number of strongly worded comments about the perceived disjuncture between the content of the short courses and actual policy and practice, as auspiced by various education sectors in Australia, for example:

I am bitterly disappointed that the [department] and its associated institutions, e.g., [redacted], plus regional staff have not embraced this research and disseminated it to schools. It is an appalling situation and the quality of the lives of so many children/adults will be forever disadvantaged by lacklustre, poorly researched practices.

The purpose of this paper, therefore, is to describe the response of one university to a policy and practice problem facing primary teachers: their inadequate preparation for classroom reading instruction. To do this, we describe the development of online short courses, including the content of the programmes, their delivery mode, and the way in which they have been received by participants, through analysis of both quantitative and qualitative feedback. In so-doing, we address a significant knowledge-gap with respect to teacher voice on reading instruction and teachers’ openness to moving away from BL if they are provided with the necessary foundational knowledge as a starting point. At the time of writing, we have delivered a total of 13 instances of these programmes and just on 10,000 participants have completed one or more courses. We report here on data collected since our adoption of formal centralised university evaluation processes that are used across undergraduate, postgraduate and short-course (non-award) programmes. The evaluation reported here spans 10 short course instances, from October 2021 to September 2023. This research project was approved by the La Trobe University Human Ethics Committee (Approval HEC 21409).

Method

We describe a mixed-methods descriptive study using both quantitative and qualitative data in order to assess the acceptability to end-users in schools of online short course professional learning on the science of language and reading. Quantitative data were analysed descriptively, and a deductive content analytic approach, based on Elo and Kyngäs (Citation2008), was used to code and categorise the free-text comments. Deductive content analysis is suitable for open-ended responses to survey questions as a means of providing a condensed description of the data and is often used within mixed methods approaches (Thompson et al., Citation2022). The third author performed the initial coding manually and categorised the responses according to shared characteristics. Trustworthiness was established by having the first author independently re-code according to the established categories, and author two verified these coding decisions.

About the short courses

Topics for the three short course programmes were selected on the basis of our work with schools and knowledge of commonly sought-after professional learning topics by teachers. They are not intended to be exhaustive but are aimed at covering key theoretical frameworks that have been shown to be under-represented or absent in Australian ITE programmes (Buckingham & Meeks, Citation2019; Weadman et al., Citation2021) and practical considerations that can equip teachers and other practitioners who are shifting their practice away from BL. The first two courses were particularly designed with primary (elementary) teachers in mind but are also open to secondary teachers.

Each session topic is addressed via a 60–70-minute online Zoom™ webinar (not meeting) presentation by one of the SOLAR Lab team and participants have access to the PowerPoint slides five days ahead of the teaching week. During the webinar presentation, participants are encouraged to post comments and questions via the Q&A function, and to upvote comments/questions posted by others. They can also interact with each other via the “chat” function. At the conclusion of the webinar, the SOLAR Lab team member who was not presenting, hosts a real-time discussion with the presenter, of 20–30 minutes’ duration, that draws on the Q&A contributions, starting with those that were most upvoted.

There are no pre-requisites, and the courses can be completed in any combination and sequence. A 10% discount is offered to schools that enrol 10 or more staff (or their entire staff, in the case of small schools) given the importance of supporting the process of whole-school curriculum change (Hunter & Haywood, Citation2023; Hunter et al., Citation2022). Course content and delivery approach are outlined briefly below.

Introduction to the science of language and reading

This course is run over four weeks, and the following topics are covered:

Oral language foundations as the basis for learning to read.

The Simple View of Reading and how it informs and supports classroom practice with respect to decoding and language comprehension.

An introduction to linguistics for reading instruction: letters vs sounds, phonemes, graphemes, digraphs, consonants, vowels, the schwa vowel, stress in words, morphology and etymology.

An overview of different types of phonics instruction.

The Science of language and reading: intermediate

This course is run over five weeks, and the following topics are covered:

Oral language: A deeper dive. Vocabulary across the tiers, discourse genres, inferencing and metalanguage.

Cognitive Load Theory, explicit instruction, and leveraging neuroscience research in the classroom.

Progress monitoring in reading: Making the most of Multi-Tiered Systems of Support.

Developmental Language Disorder: The most common disorder you’ve never heard of.

Learning Difficulties: Early identification and intervention to close the achievement gap.

The Science of language and reading: the secondary school perspective

This course is run over four weeks, and the following topics are covered:

What is reading? Unpacking what the reading process is and why it is challenging for some students.

What is writing? Unpacking the writing process and why it is challenging for some students.

Building vocabulary skills for success across the curriculum.

Managing cognitive load and behavioural/emotional responses when working with struggling secondary students.

Each short course is hosted on the university’s Learning Management System ((LMS); “Moodle”). The LMS site opens five days ahead of the course commencing and each week (topic) has its own page, which becomes visible to participants on the Thursday before a course week. The LMS page for each week/topic contains background text explaining the topic and its importance, as well as links to open-access web-based resources (articles and videos) that align with current scientific understandings about the science of language, reading, and learning. These pages are reviewed and updated as necessary prior to the commencement of each programme. An information technology (IT) staff member is online for each session, to ensure that any IT issues with the platform are resolved efficiently. PowerPoint presentations are delivered with live captioning enabled and a full transcript of each session is uploaded following the session, along with a link to the recording.

Participants have access to the LMS site for a further month after the short course has concluded. They also have access to an online Discussion Forum for each topic and comments/questions that cannot be responded to in real time after each presentation are added by the presenters to this as new threads, with a response provided by one of the course presenters. Participants are also encouraged to start their own discussion forum threads for issues and questions related to the topic of a given week. We inform participants that we are not affiliated with any particular commercial programmes and provide links regarding (for example) systematic synthetic phonics programmes that we consider to be evidence informed. We also note that we cannot respond to questions about individual students.

After each session, participants are invited to complete a short (5-item) online optional multiple-choice quiz, (a) to enhance engagement in the course content, (b) so they can check their own understanding of new content (Cook & Babon, Citation2017), and (c) so that they can see review and checking of recently taught material being modelled in practice and can consider how this might be used in their own classrooms, as a way integrating learning and assessment (Wiliam, Citation2011). Participants receive a La Trobe University (School of Education) Certificate of Completion at the conclusion of the short course. Participation in a SOLAR Lab short course contributes to the professional learning requirements for both teachers and allied health professionals.

ithin a week of the conclusion of their short course, participants receive an email from the university central student administration team, inviting them to complete a brief, anonymous survey concerning their experience of the professional learning and its perceived value with respect to their classroom practice, allied health role, and/or leadership portfolio, and informing them that the data will be used for quality assurance and research purposes. Participants are asked to indicate on a 5-point scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Undecided, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree), the extent to which they concur with the statements in the box below. Participants are also given the option of providing free-text responses after each item.

1. The course was as described.

2. The course was relevant to my needs.

3. The quality of teaching was good.

4. The eLearning platform was easy to use.

5. The course was good value for money.

6. The enrolment process was straightforward.

7. Overall, I was satisfied with the quality of this course.

It is worth noting by way of context, that these courses were introduced during the global COVID-19 pandemic, so for much of their first two calendar years, lockdowns were in place and remote learning was mandated by most but not all Australian jurisdictions for at least some of this time.

Participants

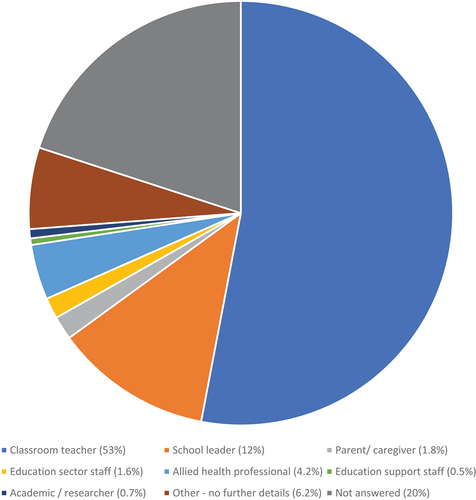

The breakdown by self-identified role is shown in . As can be seen, a total of two-thirds (65%) identified as classroom teachers (53%) or school leaders (12%), and the next largest group was allied health professionals (4.2%). Notably, 1.8% were parents/caregivers. Participants have come from all eight Australian states and territories and also from overseas (including New Zealand, Great Britain, Ireland, Fiji, and Papua New Guinea).

Results

Quantitative feedback

Analysis is derived from evaluation invitations delivered to 4379 participants and is based on an overall mean response rate across the targeted short courses of 21.3% (range = 14.3−34.6%), yielding 945 responses. This compares to a university-wide mean response rate for the same period of 23.4% (range = 17.6−34.6%).

summarises median scores and ranges on each feedback dimension, aggregated for each short course programme. As can be seen from the scores in this table, in spite of the full range of response options being covered, each short course has been extremely favourably received by participants.

Table 1. Quantitative feedback from 945 participants across 10 SOLAR Lab short courses.

Qualitative feedback

Overall, 85% of the participants provided free-text comments about aspects of the short courses that they enjoyed, and 51.1% provided suggestions for improvements. Notably, 119 respondents (12.5%) wrote some version of “there is nothing to improve” and a further 345 respondents (36.4%) wrote “n/a” (not applicable) in response to the item asking for suggested improvements. Free-text responses have been reviewed and analysed by the teaching team and are presented here as key themes emerging from this process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006).

Some dimensions (e.g. the optional self-assessment quizzes) did not feature strongly in the feedback, and when they did, opinion was evenly divided: some found them to be at the right level of complexity, and others found them too difficult. Time of day for the live sessions was also a matter on which views were evenly divided, with some participants indicating that this worked well for them, and others stating that it was personally inconvenient, though in most cases these latter respondents noted that being able to access recordings was appreciated. Two participants suggested that it would be beneficial to convert the short courses into a Graduate Certificate offering.

summarises the key themes emerging from participants’ free-text responses about aspects they enjoyed and includes representative quotes. As can be seen, these aggregated around the quality of the presenters’ knowledge and presentation styles, the quality and relevance of the content, the usefulness and applicability of the resources, the flexibility of the online platform, and the inclusive, respectful style adopted by the presenters.

Table 2. Positive aspects of the short coursers: Key themes and exemplar quotes.

summarises key themes emerging from participants’ free-text responses about suggestions for improvements and includes representative quotes. As can be seen, these aggregated around a sense that some sessions were too rushed, the view that the sessions could have been longer and/or the short course delivered over six rather than four weeks, and technology issues in accessing and using the Learning Management System. One participant (0.1%) commented that the content was “too basic”.

Table 3. Suggestions for improvements: Key themes and exemplar quotes.

Discussion

The La Trobe University School of Education online fully flexible short courses concerning the science of language and reading have been well subscribed and equally well received by teachers and allied health professionals and uptake continues to be strong. The courses appear to tap a zeitgeist with respect to teachers’ appetite for robust linguistic and cognitive psychology knowledge about reading and writing and applying this for instructional practice-change. The short courses pre-dated but fully align with recommendations of the most recent reviews into ITE in Australia (Next Steps, Citation2021; Strong Beginnings, Citation2023), and are consistent with other changes at a national level in Australia in recent years, for example, the revised definition of “decoding” in the Australian Curriculum (now “A process of efficient word recognition in which readers use knowledge of the relationship between letters and sounds to work out how to say and read written words”) and the removal of three cueing and predictable texts from the Australian Curriculum Version 9.0 (Citationn.d.). In spite of these national changes, wide jurisdictional differences persist across the three education sectors (government, Catholic and independent) in Australia’s eight states and territories with respect to the type of reading instruction that is endorsed (and in some cases, mandated). For example, at January 2024, this statement appears on the Victorian Department of Education website (Citation2019), date-stamped November 2023:

As noted by Wyse (Citation2010), literacy teaching involves the use of texts “to locate teaching about the smaller units of language including letters and phonemes … [This] contributes to contexts that are meaningful to children and enables them to better understand the reading process, including the application of key reading skills” (pp. 144–5)

The same web-page includes (at January 2024) the assertion that: “As with all literacy learning, phonics instruction should take place within a meaningful, communicative, rich pedagogy, and within genuine literacy events (Hornsby & Wilson, Citation2011, p. presence of these statements exemplifies the persistently strong pull of context as a means of teaching word identification, and consequently, the continued dominance of BL in many Australian jurisdictions. Accordingly, teachers need to be resourceful and discerning in accessing reliable information about the science of language and reading and assessing its theoretical foundations. Our findings suggest that teachers will respond favourably to the workforce implications of new graduates being better prepared for classroom reading instruction and to their own ongoing professional learning aligning with evidence-based principles and practices.

Qualitative comments indicate both a high level of engagement with the content and enthusiasm about its immediate classroom relevance, suggesting strong support for this information being embedded into initial teaching degrees, in line with the AITSL (Citation2020) revised standards and stakeholder input to the 2021 Next Steps (QITE) report and recommendations of the Strong Beginnings (Citation2023) report. The vast majority (84.6%) provided affirming free-text feedback, and a considerably smaller percentage (51.1%) made free-text suggestions for improvements. We note the importance of more clearly flagging with prospective participants that these short courses have a focus on theory, because this has been inadequately covered in teacher pre-service education for many years (Buckingham & Meeks, Citation2019; Moats, Citation2014; Strong Beginnings, Citation2023). As short courses, there are unavoidable limitations on the breadth of content that can be covered, and we consider solid theoretical understandings to be an important basis on which teachers can modify their reading instruction practice. Extensive Australian evidence indicates that teacher knowledge about core linguistic constructs that support explicit reading instruction is lacking (Fielding-Barnsley, Citation2010; Stark et al., Citation2015; Tetley & Jones, Citation2014). Applying the maxim that “programs don’t teach children to read, teachers do”, this suggests that teachers who undertake training in the delivery of a systematic synthetic phonics programme will be better positioned to understand its logic and adjust their teaching in response to the needs of their learners, if they have a solid grasp of linguistic and cognitive principles underpinning the reading process and optimal reading instruction.

Fine-tuning adjustments continue to be made to ensure a positive experience for participants, both with respect to the content and the practical ease with which they use the LMS site. These include encouraging judicious use of the chat function and ongoing refinements of the registration and log-in processes at university level – the latter being matters that are not directly under our control.

In order to address participants’ evident thirst for further knowledge concerning the science of language and reading, the first two authors have developed a Language and Literacy specialisation in the La Trobe Master of Education programme. This was offered for the first time in 2022, with 30 enrolments and saw a more than four-fold increase to 130 enrolments in 2023. In 2024, the four core Language and Literacy subjects will be offered as a Graduate Certificate in Education specialisation, which will also be an exit-option from the Master of Education. Finally, we have dramatically overhauled the reading instruction content of subjects (units) in our pre-service (undergraduate and postgraduate) programmes. While La Trobe University ITE students will continue to learn about BL, they will have a thorough knowledge of contemporary evidence on the SoR and its classroom application via explicit instruction approaches that draw on strong knowledge of the nature of the English writing system (e.g. Such, Citation2021).

Limitations

Our evaluation is based on an overall response rate of 21.3%, which is close to the university average, but still means it is a potentially biased sample. Qualitative comments have been collected only via free-text options, and it may be beneficial in the future to invite participation in focus group or one-to-one interviews, to gain a deeper understanding of the impact of the short courses on participant knowledge and practice.

Because this was the first step in formally researching participant feedback on the online short courses, we decided against seeking Human Ethics Committee approval to collect additional demographic data outsdide the business-as-usual evaluation platform, and examine responses as a function of participant role (for example, teacher, school leader, allied health professional), school sector (government, Catholic, independent), state/territory of residence, or years of classroom experience. We recommend that future researchers consider including some or all of these demographic characteristics but note that some respondents may find items about these dimensions intrusive and decline to participate as a consequence.

Summary and conclusions

The teaching of reading has been a fiercely contested topic for many decades, with universities and education jurisdictions being allowed a high degree of autonomy with respect to the pedagogical decisions made about the what and how of reading instruction. Some pockets of jurisdictional change are occurring in Australia and in many respects, this seems to be driven from bottom-up advocacy for change by classroom teachers. La Trobe University’s first three online short courses addressing the professional learning needs of both primary and secondary teachers have been well-received and are contributing to an upskilling of Australian teachers on the science of language and reading. The adoption of low variance curriculum delivery at sector and school levels will be important in redressing ongoing discrepancies in student performance in Australia (Hunter & Haywood, Citation2023; Hunter et al., Citation2022). In the short-to-medium term, therefore, this needs to be embedded in all ITE programmes, in line with the recommendations of the Strong Beginnings Report (Citation2023). In this way, valuable teacher professional learning time can be devoted to refinements in teaching, rather than delivering content that was absent from the initial degrees, in spite of its existence in peer-reviewed literature and government reviews over several decades.

Acknowledgements

We thank short course participants for taking the time to respond to the evaluation form. We are grateful to the La Trobe University Data Analytics team for assistance on collecting and collating feedback from short course participants.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Literacy and Numeracy Education Expert Panel. (2024). Achieving equity and excellence through evidence-informed consistency – Final Report of the ACT Government’s Literacy and Numeracy Education Expert Panel. ACT Government. www.education.act.gov.au/literacyandnumeracyinquir.

- Vision for Instruction: Flourishing Learners position statement. (2024). https://www.macs.vic.edu.au/MelbourneArchdioceseCatholicSchools/media/Documentation/Documents/Vision-For-Instruction-Position-Statement.pdf

- Australian Curriculum. (n.d.). The Australian curriculum (Version 9.0). https://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/

- Australian Instutite for Teaching and Learning. (2020). Guidelines for the accreditation of initial teacher education on programs in Australia. AITSL.

- Binks-Cantrell, E., Washburn, E. K., Joshi, R. M., & Hougen, M. (2012). Peter effect in the preparation of reading teachers. Scientific Studies of Reading, 16(6), 526–536. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888438.2011.601434

- Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Buckingham, J. & Meeks, L. (2019). Shortchanged: Preparation to teach reading in initial teacher education. Five from Five. https://fivefromfive.com.au/publications/

- Buckingham, J., Wheldall, K., & Beaman-Wheldall, R. (2013). Why Jaydon can’t read: The triumph of ideology over evidence in teaching reading. Policy, 29(3), 21–32.

- Cambourne, B. L. (2006). Playing ‘Chinese whispers’ with the pedagogy of literacy. In R. Ewing (Ed.), Beyond the reading wars. A balanced approach to helping children learn to read (pp. 27–39). Primary English Teaching Association.

- Castles, A., Rastle, K., & Nation, K. (2018). Ending the reading wars: Reading acquisition from novice to expert. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 19(1), 5–51.

- Cook, B. R. & Babon, A. (2017). Active learning through online quizzes: Better learning and less (busy) work. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 41(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2016.1185772

- Cozmescu, H. (2008). Thinking balanced literacy planning. Practically Primary, 13(2), 6–10.

- Elo, S. & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Ewing, R. (2018). Exploding some of the myths about teaching children to read. A review of research on the role of phonics. NSW Teachers Federation.

- Fielding-Barnsley, R. (2010). Australian pre-service teachers’ knowledge of phonemic awareness and phonics in the process of learning to read. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 15(1), 99–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404150903524606

- Gardner, P. (2019). The GERM is spreading: Literacy in Australia. Education Journal Review, 26(2), 8–11. https://foundationforlearningandliteracy.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Gardner-P-2019-Literacy-Today-No.91-8-11-5.pdf

- Geary, D. C. & Berch, D. B. (2016). Evolution and children’s cognitive and academic development. In D. C. Geary & D. B. Berch (Eds.), Evolutionary perspectives on child development and education (pp. 217–250). Springer.

- Goodman, K. S. (1967). Reading: A psycholinguistic guessing game. Journal of the Reading Specialist, 6(4), 126–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388076709556976

- Goodman, K. S. (2014). What’s whole in whole language in the 21st century? Garn Press.

- Gough, P. B. & Tunmer, W. E. (1986). Decoding, reading, and reading disability. Remedial and Special Education, 7(1), 6–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/074193258600700104

- Henderson, R. & Exley, B. (2012). Planning for literacy learning. Teaching literacies in the middle years: Pedagogies and diversity, 18–56. https://eprints.qut.edu.au/50721/

- Hornsby, D. & Wilson, L. (2011). Teaching phonics in context. Pearson Australia.

- Horobin, S. (2016). How english became english: A short history of a global language. Oxford University Press.

- Hunter, J. & Haywood, A. (2023). How to implement a whole-school curriculum approach. A guide for principals. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/report/how-to-implement-a-whole-school-curriculum-approach/

- Hunter, J., Haywood, A., & Parkinson, N. (2022). Ending the lesson lottery. How to improve curriculum planning in schools. Grattan Institute.

- Meeks, L., Stephenson, J., Kemp, C., & Madelaine, A. (2016). How well prepared are pre-service teachers to teach early reading? A systematic review of the literature. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 21(2), 69–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2017.1287103

- Moats, L. (2014). What teachers don’t know and why they aren’t learning it: Addressing the need for content and pedagogy in teacher education. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 19(2), 75–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2014.941093

- Moats, L. C. (2020). Speech to print: Language essentials for teachers (3rd ed.). Brookes.

- National Inquiry into the Teaching of Literacy. (2005). Teaching Reading: Report and recommendations. Department of Education, Science and Training. https://research.acer.edu.au/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=tll_misc

- National Reading Panel. (2000). The national reading panel report. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. https://www.nichd.nih.gov/sites/default/files/publications/pubs/nrp/documents/report.pdf

- Next Steps: report of the quality initial teacher education review. (2021). Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/next-steps-report-quality-initial-teacher-education-review

- Rayner, K., Foorman, B. R., Perfetti, C. A., Pesetsky, D., & Seidenberg, M. S. (2001). How psychological science informs the teaching of reading. Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 2(2), 31–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.00004

- The Reading League. (2021). Science of reading: Defining guide. https://www.thereadingleague.org/what-is-the-science-of-reading/

- Riddle, S. (2015). A balanced approach is best for teaching kids how to read. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/a-balanced-approach-is-best-for-teaching-kids-how-to-read-37457

- Rose, J. (2006). Independent review of the teaching of early reading. Department for Education and Skills. https://dera.ioe.ac.uk/id/eprint/5551/2/report.pdf

- Seidenberg. (2017). Language at the speed of sight. How we read, why so many can’t, and what can be done about it. Basic Books.

- Seidenberg, M. S., Cooper Borkenhagen, M., & Kearns, D. M. (2020). Lost in translation? Challenges in connecting reading science and educational practice. Reading Research Quarterly, 55(S1), S119–S130. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.341

- Snow, P. (2020). Balanced literacy or systematic reading instruction? Perspectives on language and literacy. http://www.onlinedigeditions.com/publication/?i=655062&article_id=3634779&view=articleBrowser&ver=html5

- Spear-Swerling, L. (2018). Structured literacy and typical literacy practices: Understanding differences to create instructional opportunities. Teaching Exceptional Children, 51(3), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/0040059917750160

- Stark, H. L., Snow, P. C., Eadie, P. A., & Goldfeld, S. R. (2015). Language and reading instruction in early years’ classrooms: The knowledge and self-rated ability of Australian teachers. Annals of Dyslexia, 66(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11881-015-0112-0

- Strong Beginnings. (2023). Report of the teacher education expert panel. Australian Government. https://www.education.gov.au/quality-initial-teacher-education-review/resources/strong-beginnings-report-teacher-education-expert-panel

- Such, C. (2021). The art and science of teaching primary reading. Sage.

- Tetley, D. & Jones, C. (2014). Pre-service teachers’ knowledge of language concepts: Relationships to field experiences. Australian Journal of Learning Difficulties, 19(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/19404158.2014.891530

- Thompson, D., Deatrick, J. A., Knafl, K. A., Swallow, V. M., & Wu, Y. P. (2022). A pragmatic guide to qualitative analysis for pediatric researchers. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 47(9), 1019–1030. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsac040

- Victorian Department of Education Literacy Teaching Toolkit. (2019). https://www.education.vic.gov.au/school/teachers/teachingresources/discipline/english/literacy/readingviewing/Pages/litfocusphonics.aspx

- Washburn, E. K. & Mulcahy, C. A. (2014). Expanding preservice teachers’ knowledge of the English language: Recommendations for teacher educators. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 30(4), 328–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/10573569.2013.819180

- Weadman, T., Serry, T., & Snow, P. C. (2021). Australian early childhood teachers’ training in language and literacy: A nation-wide review of pre-service course content. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 46(2), 29–56. https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2021v46n2.3

- Wiliam, D. (2011). What is assessment for learning? Studies in Educational Evaluation, 37(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2011.03.001

- Wyse, D. (2010). Contextualised phonics teaching. In K. Hall, U. Goswami, C. Harrison, S. Ellis, & J. Soler (Eds.), Interdisciplinary perspectives on learning to read: Culture, cognition and pedagogy (pp. 130–148). Routledge.