Abstract

The purpose of this study was to follow the learning trajectory of a beginning teacher attempting to implement active learning instructional methods in a middle grades classroom. The study utilized a qualitative case study methodological approach with the researcher in the role of participant observer. Three research questions were explored: the challenges the teacher faced, the supports that enabled the teacher to implement active learning, and the students’ response to active learning instructional approaches. Data collection occurred over nine months and included teacher interviews, videos of lessons, a researcher log, and student questionnaires. Data analysis revealed the importance of modeling, supportive mentors, management strategies, reflection, and resources for novice teachers to experience success in the implementation of active learning.

Introduction

In effective middle level schools, “students and teachers are engaged in active, purposeful learning” (National Middle School Association [NMSA], Citation2010, p. 14). Active instructional methods are one way for middle grades teachers to get students more engaged (Downer, Rimm-Kaufman, & Pianta, Citation2007; Harbour, Evanovich, Sweigart, & Hughes, Citation2015; Yair, Citation2000), and high levels of student engagement can lead to positive outcomes including increased academic achievement (Dotterer & Lowe, Citation2011; Valentine & Collins, Citation2011; Wang & Holcombe, Citation2010). Middle grades teachers need both the confidence and the skill to implement an active learning approach in their classrooms, and it is particularly imperative for beginning teachers to experience success with this type of instruction.

The purpose of this case study was to follow the learning trajectory of a beginning teacher who was attempting to implement active learning instructional methods in a middle grades classroom. The following research questions framed the study:

What challenges might a beginning teacher experience in implementing active learning instructional practices?

What kinds of support may help a beginning teacher overcome those challenges and effectively implement active learning instructional practices?

How do middle grades students perceive active learning instructional strategies?

An Active Learning Framework

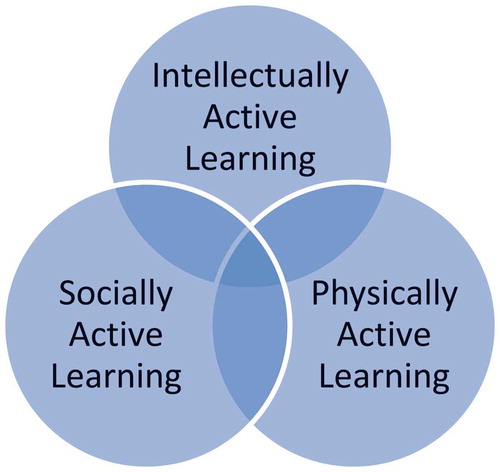

One of the earliest champions of active learning, John Dewey (Citation1924), advocated for students to be involved in experiential learning that engaged their hands and minds. He also suggested that learning activities should be social and that learners should use what they learn to achieve social ends (Dewey, Citation1897). In middle grades classrooms, young adolescents learn through experiences with the intellectual, social, and physical environments (Edwards, Citation2015a; Nesin, Citation2012). Edwards (Citation2015a) proposed an Active Learning Framework middle grades educators can use to plan instruction that is intellectually active, socially active, and physically active. While any given instructional strategy may overlap two or more of these dimensions, all three dimensions should be included in instruction (see ).

Intellectually Active Learning

It is important for students to intellectually engage with the content and not passively receive information. Intellectually active learning requires students to move beyond memorization or basic understanding and to use higher levels of thinking such as analysis, synthesis, or critical thinking (Anderson & Krathwohl, Citation2001). Young adolescents have an intense curiosity about the world around them, and instructional strategies such as problem solving, inquiry, and projects that capitalize on that curiosity can effectively increase student learning (Association for Middle Level Education [AMLE], Citation2012; Nesin, Citation2012).

Socially Active Learning

Young adolescents are peer-oriented, and allowing middle grades students to be socially active in the classroom may enhance their learning (Brighton, Citation2007). According to Vygotsky, knowledge is socially constructed (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, Citation2003), and this idea is applicable to young adolescents and can be incorporated in the classroom through partner work, small group activities, group projects, and whole class discussions.

Physically Active Learning

Young adolescents are active and energetic, therefore physical movement in the classroom is important (Nesin, Citation2012). Randler and Hulde (Citation2007) found that students in the middle grades were more engaged when they participated in experiential learning. As middle grades students enter puberty and develop physically, aspects of their body (e.g., the endocrine system) have yet to stabilize (Brighton, Citation2007). Teachers can enhance learning experiences for young adolescents who are still developing by allowing physical movement.

Challenges to Implementing Active Learning

While active learning is an important aspect of instruction in the middle grades (AMLE, Citation2012), there is disconnect in practice because a traditional, passive approach to teaching and learning is still prevalent in many middle level schools (McEwin & Greene, Citation2010). Many teachers lament the challenges of implementing active learning instructional strategies (Wood, Citation2004). Edwards (Citation2015b) studied nine middle grades teachers who successfully implemented active learning as a regular approach in their classrooms. The teachers shared common challenges in implementation, such as challenges related to the system, challenges related to students, challenges related to content, and challenges within the teachers. These teachers were able to overcome these challenges because they had three common characteristics: they were tenacious, they were student-focused, and they were willing to experiment. The nine teachers in the study were veteran teachers, but it is important to also consider what challenges a beginning teacher interested in implementing active learning instructional methodologies might face and what is necessary to help him or her overcome those challenges.

Methodology

I used a case study design for this research study. Case studies can be helpful in representing a typical situation, which in this case was the seventh-grade classroom of a beginning middle grades teacher. Yin (Citation2009) suggested that case studies are useful when the researcher wants to consider the contextual conditions and understand their impact on the phenomenon. By selecting one classroom, it was possible for me to describe the challenges a typical beginning teacher may face in implementing active learning and also explore what supports might help a beginning teacher. According to Baxter and Jack (Citation2008), an advantage of the case study approach is the close collaboration between the researcher and the participants, which allows them to tell their story while taking the context into account. As a result, the case study approach enabled me to better understand the reality of the participants.

Participants

The teacher in the seventh grade language arts classroom was Tiffany Johnson (pseudonym), who had just begun her first year of teaching. She previously served as a substitute teacher in a variety of middle schools during the one and a half years since she graduated from the middle grades education program at the local university.

There were 29 seventh-grade students in this second period classroom. Of the 29 students, 17 were boys and 12 were girls. Thirteen of the students were African-American, 12 of the students were Caucasian, two of the students were Hispanic, and two identified as multi-racial. It was a regular language arts class, and no students were identified as having special needs.

Setting

Carswell Middle School (pseudonym) was located near an army base in a suburban setting. This was the second year in a new building and the first year of the new principal who had just been promoted after being an assistant principal at another middle school in the district. The school population was growing quickly (1,044 students at the time of the study) due to expansion on the army base, and the typical class in the school had more than 30 students. School-wide standardized test results indicated that 47% of the students scored at the proficient level or higher on the state language arts assessment (Columbia County Board of Education, Citation2016), and 36 % of the students in the school were on free or reduced lunch (Georgia Department of Education, Citation2016).

Position of the Researcher

In this case study, I was the researcher and took on the role of participant observer. To become fully immersed in the challenges of implementing active learning in a middle grades classroom, I posited that it was important for me to do more than observe. Therefore, I co-taught with Tiffany Johnson, the beginning teacher, during second period for one day a week. Yin (Citation2009) argued that a distinctive advantage to becoming a participant observer is that it allows the researcher to “perceive reality from the viewpoint of someone inside the case study rather than external to it” (p. 112). To really understand how to support beginning teachers’ implementation of active learning, it was important for me to understand their perceived realities.

I endeavored to participate in the planning and instruction with Tiffany, but the extent of our collaborative planning was limited due to Tiffany being unavailable to meet. Often, some planning occurred via e-mail, and I primarily assisted with instruction in the classroom.

It is also important to note that Tiffany and I had a previously developed relationship. Tiffany was a former student in two of my teacher education courses. Admittedly, this relationship presented limitations to the study because I was moving from a position of power as instructor over Tiffany to a position of colleague and assistant. This previous relationship may have impacted the results of the study, but I selected this teacher primarily on the basis of her stated beliefs in favor of active learning.

Data Collection

A variety of data were collected during the study, including interviews, videos, a student questionnaire, and researcher log entries. Each source of data contributed to my understanding of the beginning teacher’s implementation of active learning instructional strategies.

I conducted two semi-structured interviews with Tiffany, one during the summer before the school year began and one in March. Both interviews lasted about 45 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim. The interview protocol consisted of a series of open-ended questions about active learning as an instructional approach. I asked the teacher about her beliefs related to active learning, the challenges with implementing active learning, and the supports she finds helpful.

Every lesson the teacher and I co-taught was video recorded. The camera was set in a corner of the room and remained stationary, and the videos were only viewed by me during the study.

At the end of the first semester, I asked the students to complete a written, anonymous questionnaire. The questionnaire consisted of open-ended questions about their preferences regarding various active learning strategies. For example, one question asked, “Do you like small group discussions and do you believe they help you learn? Why or why not?”

I maintained a research log throughout the study. The log contained both descriptive field notes of observed events as well as reflections and insights. The log served several purposes: to record observations not otherwise contained in the data, to record questions for further exploration, and to record my personal experience in co-teaching using active learning instructional methodologies.

Trustworthiness

Using a case study approach with the researcher in the role of participant observer provided me a richness of understanding and the ability to explore implementation of active learning through the perceived reality of a beginning teacher. However, the choice of this methodology increases the need for me to establish credibility and trustworthiness of the data. I utilized multiple methods suggested by Baxter and Jack (Citation2008) and Harding (Citation2013) to promote data credibility and trustworthiness.

Using a case study approach allowed me to explore active learning from multiple perspectives (the teacher, colleagues, administrators, and students).

Intense exposure within the context over a prolonged period of time enhanced the credibility of the data.

I conducted member checks at three points. After each interview, I sent the teacher the transcript, and asked if it represented her views and if she would like to add to or take away anything. Additionally, I asked the teacher to read this written report and determine if it accurately represented her experiences as a beginning teacher implementing active learning instructional methods.

I used triangulation of multiple sources of data (interviews, observations, researcher log), and I actively looked for data that might not fit the patterns or could provide alternative explanations.

Data Analysis

I initially coded the data according to the three research questions: challenges, supports, and student responses. This holistic method of immersion was a first approach to understanding the overall contents and possible categories that might develop. During this process, I also wrote theoretical memos that recorded impressions and observations about patterns in the data.

I then analyzed the data using the constant comparative method (Charmaz, Citation2006; Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967), a systematic approach that employs various levels of coding to theorize a phenomenon being studied. I conducted open coding with both descriptive codes and emic codes, or keywords of the participants themselves, such as “learn without realizing it.” Then, I proceeded through a process of axial coding, which involved exploring the open codes within the sections that were initially coded for each research question. This resulted in categories related to each research question (Grbich, Citation2013).

Results

Challenges

To address the first research question, it was important to explore the challenges that Tiffany faced as she attempted to implement active learning. Like many first-year teachers, Tiffany felt overwhelmed by her new responsibilities and struggled in a variety of areas. I attempted to focus on the challenges that were directly related to her implementation of active learning instruction.

Negative colleagues

Tiffany’s greatest source of discouragement in implementing active learning instruction came from negative colleagues. When Tiffany was hired to teach at the school, the principal told her that he strategically placed her on a team of three veteran teachers because they “tend to be complainers,” and she had such a positive attitude. He had hoped that she would be a good influence. Before school started, Tiffany expressed her concern about this team assignment. “I’m like a chameleon,” she said. “I become like whoever I am around. I hope this doesn’t change me for the worse.”

The team teachers discouraged her from incorporating active learning in both overt and subtle ways. For example, Tiffany reported that the behavior of the students on the team was “getting a little crazy” just before Christmas break. The inappropriate behavior was happening in all four classrooms, in the hallway, and in the cafeteria. The other teachers on the team attributed this to Tiffany’s instructional approaches and suggested the students were leaving Tiffany’s class a little too excited due to her active learning methodologies, and they suggested she change her teaching approach.

Tiffany also described another teacher in the hallway who would stop by her room and “poke fun at her.” He would make comments such as, “Oh it must be nice to play games every day. What game are you playing today?” When Tiffany started explaining what they were learning his typical response was, “Oh, whatever. You pretend it’s learning.”

Tiffany lamented more than once that she wished she could find a colleague who was willing to do active learning with her. She referred to the chameleon analogy again. “It is hard to find a positive person and I unfortunately am a chameleon and I become what I’m around.”

Colleagues with different philosophies

The school had arranged structures for teacher support that required Tiffany to plan with other teachers. One of Tiffany’s classes was an inclusion class with six students who had special needs. A veteran special education teacher was also assigned to the classroom to co-teach with Tiffany. Therefore, Tiffany and the special education teacher collaboratively planned lessons that they designed to meet the needs of all the students. In addition, Tiffany planned with the other two language arts teachers on her grade level. Normally, collaborating with all of these experts would be ideal for a beginning teacher, and this collaboration was certainly established to support her. However, the three colleagues (the special education teacher and two language arts teachers) had philosophies of teaching and learning that differed significantly from Tiffany’s. These three teachers believed strongly in a behavioristic approach to teaching and were not interested in incorporating active learning into their instruction.

A manifestation of this philosophical difference occurred at the end of the first quarter. The school administration encouraged teachers to have students complete one project per quarter. When Tiffany met with the other two language arts teachers, she proposed a choice board for the project. The other two teachers rejected her proposal and expressed concern that it would take too long to grade. Instead, the teachers decided to give their students a packet of 75 questions about the novel they had read that quarter, and the students spent three days in class answering those questions individually.

Another example occurred with the inclusion teacher who co-taught in Tiffany’s first-period class. Tiffany had prepared an activity in which students must get out of their seats to retrieve plastic eggs containing questions. Tiffany had purposely selected the activity to allow physical movement because she believed this was important for young adolescents. The inclusion teacher did not think the activity was a good selection and wanted to remove the physical movement portion. Tiffany reported feeling berated by the inclusion teacher during this conversation.

Although Tiffany was not encouraged by colleagues to do active learning, she was encouraged to do so by the school administration. She stated, “The principal wants us to do active learning, but for some reason we have a lot of traditional teaching going on.” Tiffany felt that she was going against the grain among her school faculty, and this was difficult for her as a new teacher. There was, perhaps, unintentional or inadvertent pressure to conform to a traditional model of teaching. Tiffany commented one day, “I feel myself getting sucked in to that mindset and way of teaching.”

Logistics

Another challenge that Tiffany faced was planning the logistics of the activities. Tiffany was not a naturally organized person and would often not think through the logistics of implementing an activity with 30 students. Tiffany reported, “[I get] so caught up in planning the activity that I don’t take time to think through the logistics.” As the year progressed, Tiffany began to realize, “The thing with active learning, you can put it together but you really have to work it out before they do it.” For example, one day she planned a carousel activity involving chart paper placed around the room. She later realized that as the day progressed, the requirement that teachers step into the hallway during class changes would prevent her from changing the chart paper between classes. She had not thought through a solution to this ahead of time, and the result was unnecessary off-task time that she could have avoided.

Tiffany also struggled with building individual accountability into group activities. She felt that it was likely that some students were “flying under the radar and getting away with not thinking.” She observed that when she was working with one group of students, the other groups were sometimes off-task. She also often neglected to get individual formative assessment data on days that she planned small group activities. During one class observation, Tiffany had the students in groups of six, but she gave each group one dry-erase board to write answers. This resulted in only one or two students in each group being on-task during the activity.

Lack of planning time

The primary reason for not thinking through logistics was a lack of adequate planning time. Tiffany rarely had any time for planning built into the work day. Her planning periods were regularly filled with RTI meetings, 504 plan meetings, IEP meetings, team meetings, mandatory professional development sessions, parent conferences, and administrative meetings. The school system had a county-wide initiative to incorporate writing across the curriculum, and teachers regularly met with instructional coaches during their planning periods to analyze student writing samples. Tiffany attempted to compensate for this by doing her grading and planning on evenings and weekends, but she found it difficult as a mother of two daughters. She was simply overwhelmed.

Supports

Tiffany had firm beliefs about the importance of active learning for her students. As a beginning teacher, she needed support as she endeavored to enact her beliefs in the classroom. I attempted to focus on these supports so I could answer the second research question. Five methods of support enabled Tiffany to bypass the obstacles: seeing it with her own eyes, supportive mentors, management strategies, reflection, and resources.

Seeing it with her own eyes

Tiffany often referred to the importance of seeing the impact of active learning on the students. She frequently made comments like, “If I can keep them engaged and I can keep them active then the behavior issues are going to come down and they are going to learn because they want to be in the room,” and, “I saw how into it those kids were.” I found it significant that Tiffany experienced the impact of active learning on the level of engagement and learning in her students.

It was also important for Tiffany to see active learning strategies modeled. She often wanted more than just a description; she wanted to see it in action. She made comments that every time she saw me implement a strategy, she felt confident doing the same strategy with her other classes. I was the only person Tiffany knew in the school who modeled active learning instructional strategies. She suggested, “I feel sure, I am one of those people when I find out that somebody’s doing it I’ll probably be in their room all the time.”

Supportive mentors

Ironically, while negative pressure from colleagues was Tiffany’s biggest challenge in implementing active learning, her biggest support came from positive colleagues. First, Tiffany had met another language arts teacher at a school across the district where she had previously worked as a substitute teacher. She had kept in touch with that teacher and had come to rely on her for advice and instructional strategies. They occasionally met on weekends to plan together. Even though Tiffany was unable to find a language arts teacher at her current school who shared her philosophy of active learning, she was encouraged by this teacher at a different school. Tiffany suggested, “I think that’s what it comes down to—if you have somebody you can bounce ideas off of that aren’t just going to criticize you, even though they may not be on your hallway or even in your school.”

Second, Tiffany had support from the school administration. The administrative team at her school encouraged her to continue using active learning and noted that she kept the students engaged during their observations of her classroom. She noticed that the principal even made it a point to peek into her room and see what she was doing even when he was not doing one of the mandatory observations. Tiffany said that it meant so much to her that the administrators made comments about the students wanting to learn and participate. This reinforced her determination to implement active learning. As Tiffany stated, “I really am doing exactly what I’m supposed to be doing.”

I also played a role in supporting Tiffany, offering both emotional support and demonstrating active learning strategies. After lamenting about pressure from colleagues not to implement active learning, Tiffany commented one day, “Thank you for helping me reset my mind!”

Tiffany made it a point to look for people who were positive about her approaches to instruction. While she was discouraged regularly by negative colleagues, she found support even from irregular interactions with positive colleagues who, she believed, tried to help her figure out a way to make active learning work. In Tiffany’s mind, “To me, support comes from whoever has your back.”

Management strategies

Beginning teachers often have difficulty with classroom management, but this was not the case for Tiffany. The fact that she effectively used several management techniques to facilitate active learning made it easier for her to get her students actively engaged. Tiffany took a relationship-driven approach to management and explained that once she developed true relationships with students she “could make sure active learning is taking place.” She believed that “if you’re going to do active learning, show them some mercy.” Sometimes students got too excited during activities, and she just said, “I know you’re excited, just hang on,” rather than administering punitive consequences. She was comfortable with allowing movement in her classroom. For example, she had a stool in the back of the room so that students who wanted to move around could choose to sit on the stool.

Tiffany consistently used three management techniques to promote active learning. First, she had a basket of “squishy” creatures in her closet that students had given her. Whenever she wanted students to take turns or speak one at a time, she brought out a squishy. Only the person holding the squishy was allowed to speak. Once the speaker finished speaking, he or she tossed the squishy to someone else. Tiffany reported that students who were normally reluctant to participate would be motivated to do so just so they could hold and toss the squishy.

A second technique that Tiffany consistently implemented during active learning times involved slowly writing the title of the novel the class was currently reading on the board. If the students got too loud while doing an activity, Tiffany began spelling the one-word title. When the students calmed down and got quiet, she would stop where she was in the middle of the word. Later in the class period, if the students got too loud again, she would begin spelling the word where she left off. As long as she did not get to the end of the title before the end of the period, everything was fine. The students knew that if Tiffany reached the end of the title before the end of the period, she would stop the activity and require them to do “boring worksheets” instead. The students tended to cooperate so they could participate in activities they found enjoyable.

The third technique was a method of last resort for Tiffany that she used sparingly, and I only witnessed it once. If an individual student was off-task, she would redirect the student once with a verbal warning. If the student did not get on-task and stay on-task, she would remove the student from the activity, and require him or her to work alone or complete an alternate worksheet on the same content.

Reflection

Tiffany had a natural tendency to reflect on her practice and to act upon her reflections, and this process enabled her to implement active learning effectively. Tiffany engaged in what Schon (Citation1987) called reflection in action and reflection on action. Reflection in action occurs when the teacher consciously looks at a problem in the midst of the situation and considers possibilities in light of the practice in place. This occurs during a time in “which we can still make a difference to the situation at hand—our thinking serves to reshape what we are doing while we are doing it” (Schon, Citation1987, p. 26). Tiffany was comfortable reflecting on and acknowledging the logistical problems in front of her students. She summarized her beliefs about reflection in action in the following statement.

To me, try it and if it doesn’t work, admit it to them. Because one of the things that we’re supposed to do is to teach the kids if something doesn’t work, that’s not a reason to stop. It’s a reason to say what can I change, how do I make it better, how can I be successful?

She decided that her ability to reflect was beneficial to her, and when she saw something was not working, she “tweaked it along the way.” The “tweaking” involved making organizational and logistical changes to activities so they flowed more smoothly in later class periods.

In addition to reflection in action, Schon (Citation1987) suggested that teachers should also engage in reflection on action. Reflection on action is a reflective conversation with the materials and the situation that allows the teacher to frame and reframe problems in light of information she gains from the setting in which she works. While Tiffany often regretted not thinking through the logistics of an activity before she implemented it, she readily fixed the problems before the next class. She stated, “So, when something didn’t work, by the next period it worked. Because I figured out what worked or what didn’t work; to make some little changes along the way.”

Resources

Tiffany believed that a key to her successful implementation of an active learning instructional approach was having enough resources for ideas. While she did not have the time that she wished to explore resources that might be out there, she highly valued resources that others who also believed in active learning shared with her. For example, she described a meeting with the teacher in the other school who was mentoring her in using active learning.

What I like, when I met with my friend this weekend she had three books and I ordered them all on Amazon right there when she showed me. Because she flipped and she goes, okay I have tried all of these and she starred all the ones that worked and I quickly just looked at those and I was like, I can make that work, I can do that. So, I made a little note, so that when that book comes in I know these have been used, they were successful, try these first.

Student Response

To examine the third research question, I explored students’ perceptions of active learning instructional practices. I analyzed student questionnaires (self-report), teacher interviews (self-report), and the researcher log to answer this question. Overall, the students responded positively to Tiffany’s active learning instructional approach. They were clear that they preferred activities to worksheets. In particular, Tiffany believed she saw increased levels of engagement and fewer behavior problems when she used active learning strategies versus traditional methods.

Increased engagement

Tiffany often commented about the higher level of engagement from the students when she used active learning strategies. “They love it, they just love it. They love being active, they’re learning and they don’t even realize they’re learning,” she said. The more compelling comments came from the students themselves. The students definitely voiced that activities were more fun, but they also noted that they perceived their focus and learning increased when they were given opportunities to participate in active learning. The following comments are representative of feedback I received from students.

Student 1: I love to write but not seven pages. It is not fun nor is it keeping me hooked. I would usually drool on the paper, not write on it.

Student 5: I definitely hate worksheets where you have to answer so many questions so I would like it if we can stop doing those kinds of things.

Student 7: I don’t like activities where you use a workbook to find answers because it’s not about learning the material. To the student, it’s all about finding the answer to your question. You stop focusing on the words on the page. Therefore you don’t know what it’s trying to tell you. You only look for your answer and write it down. Then you move on.

Student 9: I want my teachers to do fun activities because I don’t want to do boring activities all period.

Improved behavior

All middle grades teachers know the challenge of managing student behavior so they can focus on learning. Tiffany believed that her students’ behavior actually improved when she had them doing activities.

So, if I can keep them active and I can keep them engaged, then there are less behavior problems because they are going to be more involved in the learning itself. If they are not active, then the ones who just need to get up and move and that’s why they can’t stop kicking the person in front of them, so they want to go and get water. I have a couple of students in every class that ask to go at the beginning of class and at the end of class. But on the days that we’re doing active learning, they don’t ask to leave the classroom.

The students acknowledged that they sometimes got off-task while working in groups. One admitted, “Sometimes people talk too much about other stuff.” Their comments supported Tiffany’s assertion that behavior and, therefore, learning improves when doing active learning. The following comments represent the feedback I received from students related to behavior.

Student 13: I don’t like just learning from a PowerPoint because it’s boring and some kids fall asleep.

Student 16: I like small groups because you can learn what other people think, and also you learn something from that person.

Student 24: I like group work because you don’t have to stay quiet while you’re working and you can also ask if someone got a different answer.

Discussion

Tiffany was motivated and committed to implementing active learning in her classroom, and found ways around the challenges she experienced. She faced obstacles that made it difficult to implement active learning: negative colleagues, colleagues with different perspectives, logistics, and lack of planning time. Because Tiffany was committed to having her students engaged in active learning, she found ways to bypass those obstacles: seeing it with her own eyes, supportive mentors, management strategies, reflection, and resources. depicts how Tiffany bypassed obstacles to get her students engaged in active learning.

Tiffany, like many novice teachers, experienced disconnect between what she learned in her teacher education program and what she experienced in her new school setting. It is common for administrators to encourage new teachers to rely on more experienced colleagues to assist them in the transition from student teacher to teacher. The influence of colleagues in the teacher socialization process can be helpful or disadvantageous. If the veteran colleagues are supportive of the active learning approaches a beginning teacher is attempting to implement, then having their support can be very productive. If the novice teacher cannot find colleagues with like-minded philosophies, then they may not be as successful in implementing active learning. Valencia, Place, Martin, and Grossman (Citation2006) examined four beginning teachers and found (among other factors) that the influence of colleagues impacted the beginning teachers’ ability to adapt curriculum materials to meet the needs of their students.

The culture of traditional instruction in a middle school is a powerful force. Experienced teachers, administrators, parents, and students have preconceived notions of how content should be taught, and these people have a significant influence over the novice teacher (Brown & Borko, Citation1992). If the novice teacher enters a school that supports different styles of teaching, the findings on teacher socialization are positive. Colleagues and administrators who do not support active learning approaches to teaching can be troublesome for a novice teacher in a traditional instructional culture because of the profound influences they exert on the new teacher. Sirotnik (Citation1983) suggested, “What we have seen and what we continue to see in the American classroom—the process of teaching and learning—appears to be one of the most consistent and persistent phenomena known in the social and behavioral sciences” (pp. 16–17).

Duffy (Citation2002) characterized a teacher’s vision as “a personal stance on teaching that rises from deep within the inner teacher and fuels independent thinking” (p. 334). We know from research that teachers who possess a clear vision are more likely to enact what they believe is best for their students (Duffy & Hoffman, Citation1999; Vaughn & Faircloth, Citation2011). Teachers who have vision reflect on their practice and evaluate the effectiveness of their instruction based on their students’ growth (Shulman & Shulman, Citation2004). A teacher (like Tiffany) who enacts active learning must first begin with a picture in her mind of a classroom with students engaged in active learning. That vision must rise out of a deeply held personal belief that active learning is what works for young adolescents. A clear belief in the importance of active learning is necessary for a teacher to have the fortitude to enact her vision in spite of constraints such as negative colleagues and a lack of planning time. Tiffany possessed a vision of active learning and never wavered in her belief that it was important for her students.

Tiffany envisioned a classroom in which students were regularly engaged in active learning, but she also must believe that she was capable of bypassing the challenges that she faced in order to enact that vision. Scholars refer to that belief system as teacher self-efficacy. Tschannen-Moran and Hoy (Citation2001) defined teacher efficacy as a teacher’s “judgment of his or her capabilities to bring about desired outcomes of student engagement and learning” (p. 783). Teacher efficacy refers to the extent to which a teacher feels she has the power to implement the vision she has in her mind. While Tiffany’s vision of active learning was strong, her self-efficacy was not quite as strong, and she needed support. She relied on the language arts teacher she knew from another middle school, the supportive administrators, and me to encourage her in her vision and to keep her from becoming “like a chameleon” and thinking like the teachers around her. If beginning teachers enter a school culture that is entrenched with traditional, teacher-directed teaching, then support systems must be put into place to help those teachers maintain their beliefs that active learning is important for young adolescents. Just like Tiffany found it difficult to “go against the grain” of the colleagues around her, other beginning teachers are likely to face the same challenges to their beliefs.

Teacher agency is the notion that a teacher’s belief (in this case, a belief in active learning) is translated into action. Teacher agency is enacted when educators teach according to their beliefs and vision even in the midst of restrictive policies and other challenges (Vaughn & Faircloth, Citation2011). Teacher agency is evident when teachers initiate intentional action in order to enact a specific purpose in a thoughtful manner and with autonomy (Bandura, Citation2001; Epstein, Citation2007). Teachers with agency make decisions that are consistent with their convictions and their personal beliefs about what is best for their students (Duffy, Citation2002). Scholars have identified other characteristics of these teachers. They have a sense of perceived control (Zimmerman, Citation1995) and personal empowerment (Danielewicz, Citation2001), they are persistent (Bandura, Citation2001; Edwards, Citation2015b), they have initiative (Arendt, Citation1958; Bandura, Citation2001), and they are reflective (Dewey, Citation1933; Schon, Citation1987; Zeichner & Liston, Citation1996). These teachers are able to implement their vision in the face of challenges and are able to negotiate obstacles in order to achieve their goals (Vaughn, Citation2013).

Conclusion

Although AMLE recommends that educators engage young adolescent students in “active, purposeful learning” (NMSA, Citation2010, p. 14), many middle grades students still spend the majority of their time in school engaged in passive approaches to learning (McEwin & Greene, Citation2010; Musoleno & White, Citation2010; Wood, Citation2004). Because teacher quality is the crucial factor in the classroom (Cochran-Smith, Citation2003; Darling-Hammond, Citation2000), efforts to change the passive learning culture in classrooms must begin with an understanding of the challenges and opportunities teachers face as they implement active learning strategies. Tiffany’s case shows us how one novice teacher found supports that helped her overcome the challenges she faced while attempting to implement active learning instructional methods. Further research is needed to explore methods for supporting teachers, especially novice teachers, and increasing teacher efficacy as they attempt to implement active learning methods in middle grades classrooms.

References

- Anderson, L. W., & Krathwohl, D. R. (Eds.). (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives: Complete edition. New York, NY: Longman.

- Arendt, H. (1958). The human condition. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Association for Middle Level Education. (2012). This we believe in action: Implementing successful middle level schools. Westerville, OH: Author.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26.

- Baxter, P., & Jack, S. (2008). Qualitative case study methodology: Study design and implementation for novice researchers. The Qualitative Report, 13(4), 544–599.

- Bransford, J., Brown, A., & Cocking, R. (Eds.). (2003). How people learn: Brain, mind, experience, and school. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- Brighton, K. (2007). Coming of age: The education and development of young adolescents. Westerville, OH: National Middle School Association.

- Brown, C., & Borko, H. (1992). Becoming a mathematics teacher. In D. Grouws (Ed.), Handbook of research on mathematics teaching and learning (pp. 209–239). London: Macmillan Publishing.

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2003). The unforgiving complexity of teaching: Avoiding simplicity in the age of accountability. Journal of Teacher Education, 54(1), 3–5.

- Columbia County Board of Education. (2016). Georgia milestones assessments. Retrieved from http://www.ccboe.net/files/_KUJJ7_/0d40c1ee4d3f79aa3745a49013852ec4/[state]_Milestones_14-15_Combined_for_Website.pdf

- Danielewicz, J. (2001). Teaching selves: Identity, pedagogy, and teacher education. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement: A review of state policy evidence. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8(1), 1–44.

- Dewey, J. (1897). My pedagogic creed. School Journal, 54, 77–80.

- Dewey, J. (1924). Democracy in education. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Dewey, J. (1933). How we think. Chicago: Henry Regnery.

- Dotterer, A. M. & Lowe, K. (2011). Classroom context, school engagement, and academic achievement in early adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 1649–1660.

- Downer, J. T., Rimm-Kaufman, S. E., & Pianta, R. C. (2007). How do classroom conditions and children’s risk for school problems contribute to children’s behavioral engagement in learning? School Psychology Review, 36(3), 413–432.

- Duffy, G. (2002). Visioning and the development of outstanding teachers. Reading Research and Instruction, 41(4), 331–334.

- Duffy, G., & Hoffman, J. (1999). In pursuit of an illusion: The flawed search for a perfect method. Reading Teacher, 53, 10–17.

- Edwards, S. (2014). The middle school philosophy: Do we practice what we preach or do we preach something different? Current Issues in Middle Level Education, 19(1), 13–19.

- Edwards, S. (2015a). Active learning in the middle school classroom. Middle School Journal, 46(5), 26–32.

- Edwards, S. (2015b). Active learning in the middle grades classroom: Overcoming the barriers to implementation. Middle Grades Research Journal, 10(1), 65–81.

- Epstein, A. (2007). The intentional teacher. Washington, DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Georgia Department of Education. (2016). Free and reduced price meal eligibility. Retrieved from https://app3.doe.k12.[state].us/ows-bin/owa/fte_pack_frl001_public.entry_form

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

- Grbich, C. (2013). Qualitative data analysis: An introduction. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Harbour, K. E., Evanovich, L. L., Sweigart, C. A., & Hughes, L. E. (2015). A brief review of effective teaching practices that maximize student engagement. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 59(1), 5–13.

- Harding, J. (2013). Qualitative data analysis from start to finish. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- McEwin, C., & Greene, M. (2010). Results and recommendations from the 2009 national surveys of randomly selected and highly successful middle level schools. Middle School Journal, 42(1), 49–63.

- Musoleno, R., & White, G. (2010). Influences of high-stakes testing on middle school mission and practice. Research in Middle Level Education Online, 34(3), 1–10.

- National Middle School Association (NMSA). (2010). This we believe: Keys to educating young adolescents. Westerville, OH: Author.

- Nesin, G. (2012). Active learning. In Association for Middle Level Education (Ed.), This we believe in action: Implementing successful middle level schools (pp. 17–27). Westerville, OH: Association for Middle Level Education.

- Randler, C., & Hulde, M. (2007). Hands-on versus teacher-centered experiments in soil ecology. Research in Science & Technological Education, 25(3), 329–338.

- Schon, D. (1987). Educating the reflective practitioner: Toward a design for teaching and learning in the profession. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Shulman, L., & Shulman, J. (2004). How and what teachers learn: A shifting perspective. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 36, 257–271.

- Sirotnik, K. (1983). What you see is what you get: Consistency, persistency, and mediocrity in classrooms. Harvard Educational Review, 53, 16–31.

- Tschannen-Moran, M., & Hoy, A. (2001). Teacher efficacy: Capturing an elusive construct. Teaching and Teacher Education, 17(7), 783–805.

- Valencia, S. W., Place, N. A., Martin, S. D., & Grossman, P. L. (2006). Curriculum materials for elementary reading: Shackles and scaffolds for four beginning teachers. The Elementary School Journal, 107(1), 93–120.

- Valentine, J., & Collins, J. (April 2011). Student engagement and achievement on high-stakes tests: A HLM analysis across 68 middle schools. Paper presented at the annual conference of the American Educational Research Association, New Orleans, LA.

- Vaughn, M. (2013). Examining teacher agency: Why did Les leave the building? The New Educator, 9(2), 119–134.

- Vaughn, M., & Faircloth, B. (2011). Understanding teacher visioning and agency during literacy instruction. In P. Dunston & L. Gambrell (Eds.), 60th yearbook of the literacy research association (pp. 156–164). Oak Creek, WI: Literacy Research Association.

- Wang, M., & Holcombe, R. (2010). Adolescents’ perceptions of school environment, engagement, and academic achievement in middle school. American Educational Research Journal, 47(3), 633–662.

- Wood, G. (2004). A view from the field: NCLB’s effects on classrooms and schools. In D. Meier & G. Wood (Eds.), Many children left behind: How the no child left behind act is damaging our children and our schools (pp. 33–50). Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

- Yair, G. (2000). Not just about time: Instructional practices and productive time in school. Educational Administration Quarterly, 36(4), 485–512.

- Yin, R. (2009). Case study research: Design and methods, 4th ed. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Zeichner, K., & Liston, D. (1996). Reflective teaching: An introduction. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Zimmerman, M. (1995). Psychological empowerment: Issues and illustrations. American Journal of Community Psychology, 23, 581–599.