ABSTRACT

Dual language education programs are highly beneficial for literacy and academic language development with all students, especially those who are English learners. School districts nation-wide are attempting to expand K-12 dual language programs, yet teaching and learning for biliteracy development are highly complex processes, especially with middle level learners. Furthermore, there is a severe shortage of dual language teachers, posing great difficulties to efforts to expand programs, especially in middle and secondary schools. This qualitative case study focuses on two middle level teachers’ perspectives regarding the distinct qualities of biliteracy development via the science curriculum and the unique sociocultural aspects of language learning in middle school. The study and its findings also provide insight into how the distinctive qualities of dual language learning in content-based middle level classrooms might influence middle level teacher education programs.

The linguistic and cultural benefits of dual language learning in K-12 classrooms are numerous as researchers have identified academic, cognitive, socio-cultural, and economic advantages that bilingual and biliterate students have over their monolingual peers (August, Spencer, Fenner, & Kozik, Citation2012; Barac, Bialystok, Castro, & Sanchez, Citation2014; Thomas & Collier, Citation2012). Dual language programs are especially promising for language-minority students (Collier & Thomas, Citation2009; de Jong, Citation2004). English learners (ELs) in dual language programs master academic English skills better than traditional English as a second language (ESL) programs, even though only half or less of the instruction is delivered in English (August & Shanahan, Citation2010; Collier & Thomas, Citation2009; Lindholm-Leary, Citation2001). Improving student outcomes is particularly important in the middle grades, when the achievement gap widens as ELs and many other adolescents continue to read below grade level (Honigsfeld & Dove, Citation2013; Manning & Bucher, Citation2012). Moreover, young adolescent ELs have distinct developmental learning needs (National Middle School Association [NMSA], Citation2010), and they must learn extensive academic language and meet increased cognitive demands in content-based language learning (Gottlieb & Ernst-Slavit, Citation2014; Wong-Fillmore & Fillmore, Citation2012).

Despite the benefits of dual language education for young adolescents and the importance of high quality middle level education for language learning (Gottlieb & Ernst-Slavit, Citation2014), the majority of the dual language programs in the United States are at the elementary level (Center for Applied Linguistics [CAL], Citation2012; de Jong & Bearse, Citation2014; Migration Policy Institute, Citation2015). One potential reason for the decline in dual language programs beyond elementary school is the national shortage of dual language teachers, especially at the middle and secondary school levels, making it very difficult for states to expand or even sustain dual language programs (Thomas & Collier, Citation2014). Another potential reason is the shortage of teacher preparation programs for K-12 dual language teachers resulting in a nearly empty pipeline of new dual language teachers (Lachance, Citation2015; Loeb, Soland, & Fox, Citation2014).

The purpose of this interpretive case study (Yin, Citation2014) was to closely examine dual language learning in the unique setting of one North Carolina middle level school. Specifically, the study examined middle level biliteracy development in the context of language-rich science classrooms (Association for Middle Level Education [AMLE], Citation2012; Ford & Peat, Citation1988). The study focused on two middle level teachers’ perspectives regarding the distinct qualities of biliteracy development via the science curriculum combined with the unique sociocultural aspects of language learning in the middle grades (Jackson & Davis, Citation2000; van Lier, Citation2004). In addition, the study explored how these distinctive qualities of dual language learning in middle level classrooms might shape curricula in teacher education programs (Howell, Carpenter, & Jones, Citation2013, Citation2016; Miller et al., Citation2016; NMSA, Citation2010).

Review of Relevant Literature

A review of literature related to dual language learning in the context of middle level schools provides the background and rationale for the study. The review focuses on three topical areas of related literature: the many benefits of dual language programs for both language-minority and language-majority students, adolescent ELs in the middle grades who have highly complex needs related to biliteracy and academic language development, and current works on the national shortage of dual language teachers for the middle grades.

The Benefits of Additive Biliteracy

Dual language educational programs are shaped by additive biliteracy, the theory that multilingualism is beneficial for all learners (de Jong, Citation2004; García, Citation2009; Lindholm-Leary, Citation2012). Additive biliteracy aims to have all students attain biliteracy, unlike transitional programs that aim to turn off native languages when the target level of English is reached (García, Citation2009). A core principle of dual language programs is that both language-majority and language-minority students learn content concepts together through language acquisition principles, resulting in demonstrated academic proficiency in both languages (Bickle, Hakuta, & Billings, Citation2004; Collier & Thomas, Citation2007; Lindholm-Leary, Citation2012). Thus, teachers in dual language programs must understand the cognitive, linguistic, and cultural advantages of teaching language-minority and language-majority students together in a K–12 classroom (Echevarria, Vogt, & Short, Citation2016; Hakuta, Citation2011; Grojean & Li, Citation2013). Ideally, teachers, principals, and parents of biliterate students share the perspective that dual language education is advantageous for academic achievement and increased metacognition (García, Citation2009; Grosjean, Citation2010; Lopez, Citation2010; Thomas & Collier, Citation2012, Citation2014). Researchers also substantiate the pedagogical and linguistic nuances that explain biliterate students’ significantly increased academic achievement and help make the case for expanding dual language programs (Escamilla et al., Citation2013; Valentino & Reardon, Citation2015). The benefits of additive biliteracy extend to all learners, including language-minority students, and justify the expansion of dual language programs in K–12 classrooms.

Language-Minority Students in the Middle Grades

ELs represent nearly 10% of K–12 students in U.S. schools (Migration Policy Institute, Citation2015). Within this student population, there are also considerable academic gaps, indicating the need for further attention to their specialized needs (Calderón, Citation2007; Honigsfeld & Dove, Citation2013). What makes the circumstances with middle level ELs significantly difficult is that these students are faced with increased complexities of reading and writing to learn content-based concepts, which is almost the inversion of language learning and beginning to read in elementary school (Escamilla et al., Citation2013; McKenna & Robinson, Citation1990). Curricular standards and exposure to dense texts in the middle grades require students acquire reading fluency across the content areas, maneuvering through multiple registers (Gottleib & Ernst-Slavit, Citation2014). Additionally, there are digital literacies integrated into language learning in the middle grades. Students must use metacognition to be proficient in accessing Internet information to perform in content-based instruction. As Calderón’s (Citation2007) explained:

Content area literacy for ELs refers to reading and writing to learn concepts from textbooks, novels, magazines, e-mail, electronic messaging, Internet materials, or Internet sites so they can keep up with their subject matter and pass the high-stakes tests. It also means learning to read these texts critically, forming opinions, and responding appropriately orally and in writing. It means keeping up with all subjects and daily course work. It also means being part of the culture of the Internet in order to access information, evaluate contents quickly, and synthesize information for various classes. (p. 47)

Cultural pressures associated with language-minority middle level students also contribute to academic struggles. As young adolescents are developing identity, many middle level students grapple with blending traditional home languages and cultures with the academic languages and cultures of schooling. Middle level language learners often express feelings of alienation or complete disregard from adults and even some language-majority peers (Hernandez, Citation2015). However, middle level dual language-minority and dual language-majority students are somewhat different. While these students also need special attention to provide developmentally appropriate structures to recognize and appreciate the values of additive biliteracy, dual language gives equity and status to both language groups (Ball, Citation2010; Brisk & Proctor, Citation2012; Duncan & Gil, Citation2014; Hakuta, Citation2011).

The National Dual Language Teacher Shortage

While research confirms dual language programs support academic growth with all students, there remains a national concern regarding the availability of qualified teachers who are prepared for the unique requirements of dual language teaching (CAL, Citation2012; Liebtag & Haugen, Citation2015; Thomas & Collier, Citation2014). Numerous states across the U.S., including North Carolina, aim to expand dual language programs and simply cannot find sufficient dual language teachers from their local areas, regions, and often nation-wide (Office of English Language Acquisition [OELA] Report, Citation2015). Dual language teacher shortages often result in states continuously being forced to use alternative licensure options (CAL, Citation2012). Therefore, state education agencies repeatedly look to other countries to fill dual language teacher vacancies as best they can (Associated Press, Citation2008; DeFour, Citation2012; McKay, Citation2011; Modern Language Association of America, Citation2007; Rhodes & Pufahl, Citation2009).

While there are cultural and linguistic benefits to having native-speaking language teachers in U.S. dual language classrooms, there are also noted challenges associated with this dependence on temporary international faculty (Hutchison, Citation2005; Kissau, Yon, & Algozzine, Citation2011). In some cases, international teachers do not adapt to their post in the U.S., resulting in declined program enrollment or program elimination (Haley & Farro, Citation2011). While dual language program administrators may support program expansion, they are challenged to find resources to provide adequate professional development for visiting dual language teachers, and they are frequently dismayed when visiting bilingual teachers they have supported return to their countries earlier than planned due to maladjustment (Thomas & Collier, Citation2014).

Theoretical Frame

Set in North Carolina, this case study with dual language science teachers was framed by the theoretical constructs that support specialized dual language teaching and learning with additive biliteracy development. Highly qualified middle level dual language teachers must operationalize additive bilingual education theory and guide academic language development in two languages (Collier, Citation1992; García, Citation2009; Guerrero, Citation1997; Wong-Filmore, Citation2014). Two interconnected concepts within the framework that supported this investigation of middle level dual language teachers’ perspectives were (a) the complexities of content-based additive biliteracy in middle level dual language education, and (b) the importance of sociocultural theory in informing work with young adolescent language learners.

Complex Content-Based Additive Biliteracy

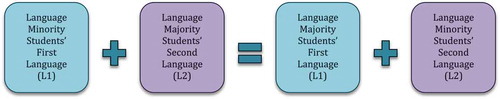

Historically, patterns for most bilingual education programs in the U.S. were transitional (García, Citation2009), meaning that language-minority students were expected to develop knowledge and language according to monolingual dominant-language norms (August & Hakuta, Citation1997; Ovando & Collier, Citation1998; Wong-Filmore, Citation2014). In contrast, this study reflects more recent practices that support the acquisition and preservation of students’ bilingualism and the development of biliteracy in both majority and home languages (see ). The configuration affords language-minority students with equal and equitable language status, honoring both languages.

Figure 1. Additive biliteracy for value added status with language-minority and language-majority students’ first and second languages.

This study examined the need for middle level dual language teachers to consider content-based biliteracy with the affirmation that both first languages (L1) and second languages (L2) are honored, addressed, and authentically connected to students’ classroom experiences, particularly in science class (García, Citation2009). Guerrero’s (Citation1997) historical research on the importance of contextualized, cognitively demanding learning experiences for Spanish academic language proficiency helped underpin this study. It stands to reason that additive biliteracy in the context of dual language in a science classroom obliges teachers to understand subject matter while simultaneously attending to the significance of native language functions, pragmatic conventions, and sociocultural layers of academic discourse development in both Spanish and English via the language of science.

Sociocultural Theory, Language, Culture, and Identity

Vygotskian sociocultural theory has informed the field of language education for several decades (van Lier, Citation2004; Vygotsky, Citation1978). An integral element in sociocultural theory is the notion that language learning with higher order cognition is developed through interaction. Students working together in varying contexts is considered essential for cognitive, metacognitive, and linguistic advancements (Cummins, Citation2014; Manning & Bucher, Citation2012). Similarly, middle level students’ learning and language development requires specialized scaffolding, which should include significant peer interaction with structured language functions (Gibbons, Citation2015; World-class Instructional Design & Assessment [WIDA], Citation2012). In the case of science and other content-based dual language instruction with middle level students, collaboration and dynamic activities within students’ zones of proximal development (ZPD) are key points to support increased language demands associated with middle level classrooms. Based on their human development, young adolescents are entirely capable of complex analytic thinking, yet they need specialized support to process and accommodate peers’ cultural and linguistic needs for successful language learning (Calderón, Citation2007; Lindholm-Leary, Citation2012).

In conjunction with Vygotskian sociocultural theory, van Lier (Citation2004) maintains that students’ self-concepts of identity greatly impact the learning and thinking processes. Students see themselves in one fashion, forming an internal sense of self. On the other hand, students are also considering the external sense of self, simultaneously giving merit to others’ opinions of how they are seen (Ryan & Shim, Citation2008). As young adolescent learners pass through this significant period in their human development, the notion of self, both internal and external, is quite intensified (Purkey, Citation1970). Uniquely, middle level learners are also advantaged with having amplified imaginations and higher levels of abstract thinking (Joseph, Citation2010). For dual language learning, middle level students’ intellectual development and broad spectrum of thinking serves to fundamentally support biliteracy development in ways that differ from elementary school settings (Molle, Sato, Boals, & Hedgspeth, Citation2015; Moore & Schleppegrell, Citation2014). With this in mind, middle level dual language teachers can tap into their students’ abstract, intellectual strengths to solidify collaboration among culturally and linguistically diverse students (Cummins, Citation2014; Klassen & Krawchuk, Citation2009).

Research Methods

The researcher conducted a qualitative, interpretive case study (Erickson, Citation1986; Merriam, Citation1998; Yin, Citation2014) with two dual language middle level science teachers in one North Carolina district. Specifically, the study focused on the distinct qualities of biliteracy development with middle level learners via the middle level science curriculum and how these qualities might potentially shape dual language teacher preparation. Three dimensions of the Center for Applied Linguistics Guiding Principles for Dual Language Education research (Howard, Sugarman, Christian, Lindholh-Leary, & Rogers, Citation2017) informed the study’s purpose and research questions:

What are the necessary considerations for middle level dual language teachers with regard to additive biliteracy development via the science curriculum?

How are the sociocultural aspects of dual language learning unique in the middle grades?

What recommendations do middle level dual language teachers have for teacher preparation programs regarding the uniqueness of content-based dual language learning?

Context

The study was situated in North Carolina where the state education agency was strategically aiming to expand the existing 120 dual language programs (State Board of Education, North Carolina [NCSBE], Citation2013). Specifically, the interpretive case study took place in the second semester of the school year to examine dual language middle level teachers’ perspectives regarding the uniqueness of dual language learning via the science curriculum, as well as the sociocultural connections with young adolescents. The study’s design and duration were selected based on Merriam’s (Citation1998) interpretive model in order for the researcher to “gather as much information about the problem as possible” (p. 38). The intent of the data collection and analysis was to develop a categorical continuum that captured a different approach to the task; in this case, specialized dual language teacher preparation for middle level programs. Furthermore, the focus on middle level dual language programs was strategic given the national shortage of secondary dual language programs. The participants’ district had difficulty finding ways to increase programs in both number and vertical span given that North Carolina has a bilingual endorsement for high school graduates (Public Schools of North Carolina [NCDPI], Citation2015a, Citation2015b). The single case (Yin, Citation2014) included two teacher participants who worked in dual language programs with English and Spanish speaking students. While other partner languages were available in North Carolina’s dual language programs, this study focused on language-minority students and language-majority students in Spanish/English program settings.

North Carolina Specifics

Of the state’s approximate 1.5 million K-12 students in public schools, nearly 100,000 are classified as ELs according to federal guidelines for basic Language Assistance Program services (NCDPI, Citation2016). With these learners in mind, as well as native speakers of English, North Carolina includes dual language and immersion programs in formalized state K-12 standard courses of study for curriculum and instruction (NCDPI, Citation2015a). In January of 2013, The North Carolina State Board of Education (NCSBE) released the document Preparing Students for the World: Final Report of the State Board of Education’s Task Force on Global Education. This call for action was to ensure that all North Carolina public school graduates are globally prepared for the 21st century (NCSBE, Citation2013). Specifically included in the report was the strategic expansion of dual language programs state-wide, already at 120 in 2016–17 (NCDPI, Citation2016). Additionally, North Carolina mirrors the national scope of K-12 dual language programs with most at the elementary level. Therefore, the study’s contextual focus within a middle level program further supported the specialized nature of preparing dual language teachers while working with young adolescents.

Participants

While North Carolina had 120 dual language programs, only 15 included middle schools and only seven districts offered programs in Spanish and English to include language-minority and language-majority students (NCDPI, Citation2016). Personal recruitment (Merriam, Citation1998) resulted in a participant group consisting of two dual language middle level teachers. Participants represented middle level teachers who were in a district attempting to increase secondary dual language programs in size and scope. Subsequently, the study participants worked in a small congregate of middle level schools with dual language programs, giving additional concentration to the interpretive single case so that specific, essential details regarding middle grades nuances might emerge (Merriam, Citation1998; Yin, Citation2014). The participating teachers had a minimum of 5 years experience in K-12 education and met the North Carolina state-required credentials to teach in dual language. This is significant, because the U.S. Department of Education Office of English Language Acquisition (OELA) reported that only half of the states offering dual language programs have established certification requirements for dual language teachers (OELA, Citation2015). In addition, both participants taught middle level science in Spanish. One was a native Spanish speaker and the other participant’s first language was English. Additional participant features were revealed in the demographic portions of the data (Seidman, Citation2013). Both participants self-identified that they volunteered to teach in dual language settings. An important aspect from the participant interviews was that while they each had teaching experiences in other grade levels, they repeatedly mentioned middle level students and a culture of interaction with young adolescent learners (NMSA, Citation2010). While they both experienced students’ learning via interaction in other grade levels, they also identified nuances with regard to students’ collaborative learning unique to middle level dual language.

Francheska

One of the two dual language teacher participants was a visiting teacher who was originally from South America. She was educated in an English-speaking immersion school in Venezuela prior to her arrival and came to North Carolina specifically to teach in the K-12 setting. Additionally, she had extensive experience in teaching science at the post-secondary level in her home country. As she transitioned to teaching into the K-12 environment, she taught high school in another southeastern state before her appointment in the dual language program at the middle school in North Carolina where this study is set. She also had extensive experience instructing science labs, and she identified herself as someone who “loves to teach using hands-on techniques.” The seventh and eighth grade science classes she instructed in the study’s site were all delivered in Spanish. Specifically, her class groups were comprized of about approximately 60% native Spanish speakers (NSS) and 40% native Englsih speakers (NES). An important detail Francheska revealed in her interview was the emphasis she gave to understanding the diversity within her Spanish speaking students. She explained that they were from various Central American countries with a range of literacy levels in Spanish. Likewise, many of the NSS are second and third-generation immigrants who may speak Spanish at home but have never been to school outside the district.

Mary Anne

The second dual language teacher participant was a native English speaker from the midwestern United States. She attended teacher preparation programs in the midwest and the southeastern United States with a focus on Spanish and elementery education methodologies. She also completed graduate work in bilingual education in the midwest and worked in a transitional bilingual program before teaching in North Carolina. In contrast to Francheska, her L2 learning occurred via intensive study-abroad experiences and self-selected language immersion experiences. She identified herself as a lover of science and studied science in Spanish. She spent a large portion of the interview expressing her views on the differences between learning another language and learning content in another language. Her emphasis on interactive academic vocabulary development from her own experiences as a second-language learner greatly shaped her lesson design and delivery processes. She recalled having to take notes quickly in a second language and not fully processing everything stated in teacher-centered lectures. Similar to Francheska, Mary Anne described her sixth and seventh grade classes as having approximately 55% native Spanish-speaking and 45% native English-speaking students, with the native Spanish-speaking students possessing varied ranges in Spanish literacy. Likewise, Mary Anne also explained the importance of knowing which native Spanish speakers were second and third generation immigrants who spoke some Spanish at home.

Data Sources

The single-case study occurred in actual dual language school settings that reflected the communities where the school research sites were situated (Yin, Citation2014). The single case design was strengthened by the researcher’s fostered relationships (Stringer, Citation2014) with the district, school administrators, and teachers. For data triangulation (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008), multiple sources of on-site evidence were examined in the context where the data were collected. In a strategic attempt to minimize the participants’ interruptions from their teaching as required by the district, data collection was expedited within a one-month period in the second half of the school year. The data sources from both participants were face-to-face interviews, artifacts and documents, and records of participant observations in the school settings. Data collection resulted in more than 50 pages of coded data for analysis (Saldaña, Citation2016).

Interviews

Semi-structured, audio-recorded interviews were conducted in two on-site sessions with both participants. Each on-site interview ranged from 70 to 90 minutes in duration. Interview recordings for each participant were transcribed, resulting in data transcriptions of 22–28 pages per participant. The semi-structured interview protocol (Seidman, Citation2013) was based on the tenets of the CAL Guiding Principles for Dual Language Education to explore current dual language teachers’ perspectives on biliteracy via dual language learning and recommendations for dual language teacher preparation. The interview transcripts were merged with additional data sources for coding and further analysis (Saldaña, Citation2016).

Artifacts and Documentation

Artifacts and documentation from the school setting that provided details about dual language learners were examined, coded, and analyzed. Photographs of classroom configurations and classroom walls along with school improvement plan documents were utilized. Specifically, these data sources were included in both the first-cycle coding process for initial descriptive coding and the second-cycle coding for patterns. Coding the study’s photographs encompassed analytic memos that conceptually connected photographic data instances (Miles, Huberman, & Saldaña, Citation2014). Additionally, both participants shared dual language curricular materials—classroom language supports used with their team of science teachers and their students—and identified science-based details from in-house adaptation of dual language materials. Some artifacts were teacher-generated while others were supporting documents from site-based textbook adoptions. Artifacts and documents also included text examples, assessment examples, classroom rubrics, and language supports from the science curriculum in both Spanish and English.

Participant Observations

Triangulated data sources also included two 70–90 minute on-site observations with both participants. The purpose of the face-to-face observations was two-fold: (a) to view the teachers in the context of their own science language-rich environments and (b) to capture relevant understandings of the participants as they were in the actual context of the schools in which they worked.

In both teachers’ classrooms, the observations took place during the school day while students were in school. Both participants self-selected the time of the observations based on their individual schedules and time constraints. Because the purpose of this study was to focus on teachers’ perspectives, the researcher did not interact with the students. Anecdotal records, including additional photographs without students from hallways, teachers’ classrooms, and the teachers’ resource room were kept to capture myriad language and science details (e.g., teacher resource kits to complete lab experiments and children’s literature kits aligned with content-based topics, including those applicable to science lessons). Some anecdotal notes included details regarding curricular materials, ancillary language supports specific to science, and other visible resources for literacy in both Spanish and English. The on-site observations provided a familiar environment for the teachers, allowing for research observations while the participants accessed their own lexical schema in Spanish and English with their students from the middle level perspective (Merriam, Citation1998).

Data Analysis

Data sources were analyzed via first cycle coding for initial descriptive markers and topic inventories. Subsequent data analysis focused on marker grouping via second cycle coding for emergent explanatory, thematic patterns (Miles et al., Citation2014). With multiple, contextualized and triangulated data sources representing cultural and social aspects in patterns of dual language learning, numerous details for in-depth descriptions emerged for interpretation (Wolcott, Citation2001). The data analysis, intending to discover nuances in dual language middle level science, also revealed details associated with teacher shortages and the unique nature of working with young adolescents (AMLE, Citation2012). Data analysis via open-ended coding with all data sources (Saldaña, Citation2016) resulted in preliminary data categories. Further data analysis for refinement included categorical culling, grouping, and re-coding processes leading to more precise emergent data patterns with distinct code markers. The thematic and categorical structures from coding each participant’s triagulated data led to meaningful data categories and sub-categories, summarizing the holistic data set to respond to the research questions (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008).

Findings

The analysis resulted in the emergence of two over-arching data categories attached to one predominant thematic axis: preparing teachers for dual language classrooms (Saldaña, Citation2016; Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008). The overarching data categories were: (a) unique dual language pedagogies in middle level science, and (b) recommendations for specialized dual language teacher preparation. Both categories had corresponding code markers, supporting the streamlining of codes-to-assertions in the data set (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2008; Saldaña, Citation2016). The code markers and frequencies for the first category were graphed, revealing a construct that suggested the participants found each of the marked codes as important ().

Figure 2. Pattern code markers for unique dual language learner pedagogies in middle school science.

Dual Language Pedagogies in Middle Level Science

Both participants described several important aspects of dual language learning in the context of middle level science. The five categorical code markers shown in indicated the unique pedagogical characteristics of middle level dual language learning in science class. Second-cycle data coding patterns revealed conceptual overlaps related to middle level students’ communication patterns while they worked collaboratively to learn science through both English and Spanish. Both teacher participants emphasized the important ways sociocultural interactions supported science learning in both English and Spanish.

Both teachers emphasized references to the processes of learning academic language in two languages while using Spanish for their science instruction. A guiding principle of dual language education is that teachers preserve the selected language of instruction for the duration of the subject area to strengthen academic language development; in this case, science in Spanish (Howard et al., Citation2018). Yet, to balance the needs of both language groups during instruction, teachers may permit students to self-select and interchange languages for peer-to-peer communication during collaborative activities. When students return to the language of the formalized instruction, bilinguals are able to express ideas demonstrating higher levels of divergent thinking and problem-solving (García, Citation2009). In this study, the data analysis code marker with the highest incidence frequency was “Students’ collective negotiation of meaning in either English or Spanish.” The amplified code marker aligns with the conceptual perspectives on second language acquisition and sociocultural nuances for academic language development in both languages (Calderón, Slavin, & Sánchez, Citation2011; Gottleib & Ernst-Slavit, Citation2014; Guerrero, Citation1997, Citation2012; WIDA, Citation2007).

Academic language development with peers is fundamental for students’ success, and it is even more important in dual language education (Collier & Thomas, Citation2007). Particular aspects of explicit instruction for middle level language learners in the literature generally relate to grammar, semantics, communicative language forms and the role of translation in the process (Calderón, Citation2007; Krashen, Citation1985; Reyes & Kleyn, Citation2010; WIDA, Citation2012). However, the data suggest another key component of dual language biliteracy appears to connect to young adolescents’ interactions that focus on academic language development in both students’ L1 and L2. Francheska expressed her ideas regarding specific aspects of the format of her classroom that supported academic language and biliteracy development. She said:

In my science classroom, I am always a facilitator of hands-on learning. I don’t lecture to the kids. It’s rare, very rare. I make them do the talking. That’s how they will learn science and Spanish. We discuss things, they [students] discuss them. … We practice writing with each other, in English and in Spanish, as often as possible. When the students collaborate, they help each other with sentence structures, the variations from one language to another, and how the writing relates to the science [content] they are learning.

On a similar note, Mary Anne discussed the sociocultural aspects of middle level dual language learning, as well as the diversity in her classroom.

Our students come from very different backgrounds sometimes. We might have a student who was a refugee or from an immigrant family where their parents didn’t really have much schooling. In any situation, the students really support each other, not just with science learning, but emotionally too. We [teachers at our school] love this about dual language in middle school. When students need extra support, they work well together.

Preparing Middle Level Dual Language Teachers

The study’s findings also included aspects regarding the need to prepare middle level teachers in dual language methodologies that are theoretically framed by additive biliteracy and address the complex linguistic and sociocultural constructs of Spanish and English (Calderón et al., Citation2011; Escamilla et al., Citation2013; García, Citation2009; Guerrero, Citation1997; NMSA, Citation2010). Participants made recommendations about teacher preparation, ensuring candidates’ readiness to teach young adolescents in two languages (Flores, Sheets, & Clark, Citation2011; Reyes & Kleyn, Citation2010). Patterns in the data also focused on the need for specific coursework for dual language teacher preparation with specific course content.

Categorical code markers (Saldaña, Citation2016) from the interview data for recommendations regarding middle level dual language teacher preparation included: (a) biliteracy development and second language acquisition, (b) developing materials for middle level content learning, (c) dual language methodologies to support students’ interaction (in L1 and L2), and (d) extensive clinicals and specialized internships. These findings support the well-established, specialized needs associated with middle level teacher preparation (NMSA, Citation2010; Vars, Citation1969) with specific methodologies and practicing in clinical settings that facilitate its learning with their students (Clarke, Triggs, & Nielsen, Citation2014; Howell et al., Citation2016; Howell et al., Citation2013; Powell, Citation2011). Francheska highlighted some of the key aspects of middle level dual language teacher preparation:

Dual language teaching methods in middle school need to get teachers ready for kids working together all the time. These kids [dual language learners] need to practice the language and their science all the time. They can’t do it alone—they need to cooperate and practice together. They need to read in Spanish, about science and this is really hard. Teachers need to know how to help them, when to translate, when not to translate, how to teach the kids not to translate word for word but total concepts, and how to have the kids negotiate meanings with each other. And the writing in middle school is different. Teachers need to know how to get the kids to support each other when they write in English and Spanish. Student teachers [for middle school dual language] need to practice this a lot to be here.

Mary Anne noted:

We need more dual language teachers. There simply aren’t enough and there are not many, if any viable options at the university level for teachers to be prepared for dual language. Most of the dual language teachers I know have all learned on the job while teaching in the classroom. There is so much more differentiation required in dual language and so many more things that need focus for understanding Spanish, English, and the content, it’s all very specialized. If we are ever going to have more middle school programs and, more programs for high school, we simply need more trained teachers [in dual language].

Summary

Both teachers expressed ideas and thoughts regarding the uniqueness of middle level dual language learning in their science classes. In addition, they both expressed clear recommendations for dual language teacher preparation to address the specialized needs for middle level dual language teaching and the need for more teachers to expand existing dual language programs and establish new ones (Howell et al., Citation2013; AMLE, Citation2012). The findings were also noteworthy because they connected to the existing additive bilingual research and to concepts related to the sociocultural aspects of young adolescents’ learning (Manning & Bucher, Citation2012; Powell, Citation2011).

Discussion and Implications for Practice

There was a general consensus among the participants that biliteracy and academic language development with young adolescent dual language learners is complex and contextual and requires specialized teaching methods (Calderón, Citation2007; Faulkner et al., Citation2017; García, Citation2009; Zadina, Citation2014). With the uniqueness of dual language in the middle grades in mind, the participants offered collaborative, creative ideas regarding cousework for dual language teacher preparation programs.

Teacher preparation for dual language should encompass coursework on second language acquisition and biliteracy with language minority and language majority students. The course content would further examine second language acquisition theory and principles through the lens of additive biliteracy and linguistic constructs with both languages. Candidates would explore how the two languages interact with one another in distinct ways with regard to discourse patterns and writing structures, as well as metalinguistic patterns with bilingual students (Beeman & Urow, Citation2013; Moore & Schleppegrell, Citation2014).

Specialized coursework might also include dual language teaching methods courses that emphasize the importance of scaffolded instruction in two languages with changed language supports based on whether students are L1 or L2 learners (Gibbons, Citation2015). A course on authentic assessment with dual language learners would also be useful, and aspects of student-centered measures for long-term assessment of language progression in two languages should be emphasized.

Additional implications include the need for increased clinical fieldwork and internships in well-established dual language classrooms. Revised coursework might include substantially deepened dual language teacher mentor relationships in middle level settings (Clarke et al., Citation2014; Flores et al., Citation2011; Howell et al., Citation2016). This holistic approach should include theory and application of standards-based dual language principles combined with specific middle level perspectives (Howard et al., Citation2017; Miller et al., Citation2016).

Another crucial discussion point is the connection between the findings of this study and the 16 characteristics of This We Believe (AMLE, Citation2012). Four of the characteristics can be sturdily cross-walked with the study’s outcomes: (a) students and teachers are engaged in active purposeful learning, (b) curriculum is challenging, exploratory, integrative, and relevant, (c) educators must use multiple learning and teaching approaches, and (d) leaders demonstrate courage and collaboration.

Conclusion

As states and districts continue to seek out well-prepared dual language teachers to sustain and expand dual language programs, it is increasingly important to find ways to address the national shortage of dual language teachers, especially in the middle grades (CAL, Citation2012; OELA, Citation2015). Teacher preparation programs are in a position to further develop program options for dual language teachers to expand dual language programs nation-wide. This study supports reconsidered approaches to teacher preparation, bearing in mind the uniqueness of working with middle level language learners. The participants expressed the complexities and the importance for middle level teachers to understand how to successfully facilitate academic language development in the context of content subjects, specifically science. Furthermore, the findings accentuate current and relevant research regarding dual language teaching and learning in middle level classrooms across the content areas (AMLE, Citation2012; Collier & Thomas, Citation2009; Hamayan, Genesee, & Cloud, Citation2013; Molle et al., Citation2015; Thomas & Collier, Citation2014). Teaching and learning in two languages with language-minority students and language-majority young adolescents require exceptional and distinct approaches that consider middle level learners. Teacher preparation programs may take heed to these important considerations to creatively facilitate the creation, maintenance, and expansion of middle level dual language education programs.

References

- Associated Press (2008, September 13). States hire foreign teachers to ease shortages. MSNBC News. Retrieved from http://www.msnbc.msn.com/id/26691720/.

- Association for Middle Level Education [AMLE]. (2012). Association for middle level education middle level teacher preparation standards with rubrics and supporting explanations. Westerville, OH: Author.

- August, D., & Hakuta, K. (Eds.). (1997). Improving schooling for language-minority children. A research agenda. Washington, DC: National Academy Press.

- August, D., & Shanahan, T. (2010). Effective literacy instruction for English learners. In California Department of Education (Ed.), Research on English language learners (pp. 209–249). Sacramento, CA: California Department of Education Press.

- August, D., Spencer, S., Fenner, D. S., & Kozik, P. (2012). The evaluation of educators in effective schools and classrooms for all learners. Washington, DC: American Federation of Teachers.

- Ball, J. (2010, February). Educational equity for children from diverse language backgrounds: Mother tongue-based bilingual or multilingual education in early years. Paper presented at the UNESCO International Symposium: Translation and Cultural Mediation, Paris, France. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0021/002122/212270e.pdf

- Barac, R., Bialystok, E., Castro, D. C., & Sanchez, M. (2014). The cognitive development of young dual language learners: A critical review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 29(4), 699–714. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2014.02.003

- Beeman, K., & Urow, C. (2013). Teaching for biliteracy: Strengthening bridges between languages. Philadelphia, PA: Calson, Inc.

- Bickle, K., Hakuta, K., & Billings, E. S. (2004). Trends in two-way immersion research. In J. A. Banks & C. A. McGee Banks (Eds.), Handbook of research on multicultural education (2nd ed., pp. 589–604). New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Brisk, M., & Proctor, P. (2012). Challenges and supports for English language learners in bilingual programs. Paper presented at the Understanding Language Conference, Stanford University, Stanford, CA. Retrieved from http://ell.stanford.edu/publication/challenges-and-supports-ells-bilingual-programs

- Calderón, M., Slavin, R., & Sánchez, M. (2011). Effective instruction for English learners. Future of Children, 21(1), 103–127. doi:10.1353/foc.2011.0007

- Calderón, M. E. (2007). Teaching reading to English language learners, grades 6–12: A framework for improving achievement in the content areas. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Center for Applied Linguistics [CAL]. (2012). Directory of two-way bilingual immerson programs in the U.S. Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/twi/directory.

- Clarke, A., Triggs, V., & Nielsen, W. (2014). Cooperating teacher participation in teacher education: A review of the literature. Review of Educational Research, 84, 163–202. doi:10.3102/0034654313499618

- Collier, V. P. (1992). A synthesis of stuides examining long-term language minority student data on academic achievement. Bilingual Research Journal, 16(1–2), 187–212. doi:10.1080/15235882.1992.10162633

- Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (2007). Predicting second language academic success in English using the Prism Model. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching, Part 1 (pp. 333–348). New York, NY: Springer.

- Collier, V. P., & Thomas, W. P. (2009). Educating English learners for a transformed world. Albuquerque, NM: Dual Language Education of New Mexico-Fuente Press.

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2008). Basics of qualitiatve research (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Cummins, J. (2014). Beyond language: Academic communication and student success. Linguistics and Education, 26, 145–154.

- de Jong, E. (2004). After exit: Academic achievement patterns of former English language learners. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 12, 50. doi:10.14507/epaa.v12n50.2004

- de Jong, E. J., & Bearse, C. I. (2014). Dual language programs as a strand within a secondary school: Dilemmas of school organization and the TWI mission. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 17(1), 15–31. doi:10.1080/13670050.2012.725709

- DeFour, M. (2012, September 23). Madison schools reaching overseas for bilingual teachers. Wisconson State Journal, Retreived from http://host.madison.com/news/local/education/local_schools/madison-schools-reaching-overseas-for-bilingual-teachers/article_39b8cae2-0586-11e2-b68b-0019bb2963f4.html

- Denzin, N., & Lincoln, Y. (Eds.). (2008). Collecting and interpreting qualitative materials (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Duncan, A., & Gil, L. S. (2014, February 19). English learners an asset for global, multilingual future. Retrieved from https://www.dailynews.com/2014/02/19/english-learners-an-asset-forglobal-multilingual-future-arne-duncan-and-libia-gil/

- Echevarria, J., Vogt, M. E., & Short, D. L. (2016). Making content comprehensible for English learners: The SIOP model (5th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

- Erickson, F. (1986). Qualitative methods in research on teaching. In M. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (3rd ed., pp. 119–161). New York, NY: MacMillan.

- Escamilla, K., Hopewell, S., Butvilofsky, S., Sparrow, W., Soltero-Gonzalez, L., Ruiz-Figueroa, O., & Escamilla, M. (2013). Biliteracy from the start. Philadelphia, PA: Calson.

- Faulkner, S. A., Cook, C. M., Thompson, N. L., Howell, P. B., Rintamaa, M. F., & Miller, N. C. (2017). Mapping the varied terrain of specialized middle level teacher preparation and licensure. Middle School Journal, 48(2), 8–13. doi:10.1080/00940771.2017.1272911

- Flores, B. B., Sheets, R. H., & Clark, E. R. (Eds.). (2011). Teacher preparation for bilingual student populations: Educar para transformar. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ford, A., & Peat, F. D. (1988). The role of language in science. Foundations of Physics, 18(12), 1233–1242. doi:10.1007/BF01889434

- García, O. (2009). Bilingual education in the 21st century: A global perspective. West Sussex, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gibbons, P. (2015). Scaffolding language scaffolding learning: Teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom (2nd ed.). Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Gottleib, M., & Ernst-Slavit, G. (2014). Academic language in diverse classrooms: Definintions and contexts. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Grosjean, F. (2010). Bilingual: Life and reality. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Grosjean, F., & Li, P. (2013). The psycholinguistics of bilingualism. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Guerrero, M. (1997). Spanish academic langauge proficiency; The base of bilingual education teachers in the U.S. Bilingual Research Journal, 21(1), 25–43. doi:10.1080/15235882.1997.10815602

- Hakuta, K. (2011). Educating language minority students and affirming their equal rights: Research and practical perspectives. Educational Researcher, 40(4), 163–174. doi:10.3102/0013189X11404943

- Haley, M., & Ferro, M. (2011). Understanding the perceptions of Arabic and Chinese teachers toward transitioning into U.S. School. Foreign Language Annals, 44, 289–307. doi:10.1111/j.1944-9720.2011.01136.x

- Hamayan, E., Genesee, F., & Cloud, N. (2013). Dual language instruction from a-z: Practical guidance for teachers and administrators. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- Hernandez, A. (2015). Language status in two-way bilingual immersion. Journal of Immersion and Content-based Instruction, 3(1), 102–126.

- Honigsfeld, A., & Dove, M. (2013). Common core for the not-so-common learner: English language arts strategies grades 6–12. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Howard, E. R., Lindholm-Learly, D., Rogers, D., Olague, N., Medina, J., Kennedy, B., Sugarman, J., & Christian, D. (2018). Guiding principles for dual language education (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Howard, E. R., Sugarman, J., Christian, D., Lindholh-Leary, K. J., & Rogers, D. (2017). Guiding principles for dual language education (3rd ed.). Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

- Howell, P., Carpenter, J., & Jones, J. (2013). School partnerships and clinical practices at the middle level. Middle School Journal, 44(4), 40–49. doi:10.1080/00940771.2013.11461863

- Howell, P., Carpenter, J., & Jones, J. (2016). Clinical preparation and partnerships at the middle level: Practices and possibilities. Charlotte, N.C.: Information Age Publications.

- Hutchinson, C. (2005). Teaching in America: A Cross-Culutral guide for international teachers and their employers. Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer.

- Jackson, A. W., & Davis, G. A. (2000). Turning points 2000: Educating adolescents in the 21st century. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Joseph, N. (2010). Metacognition needed: Teaching middle school and high school student to develop strategic learning skills. Preventing School Failure, 54(2), 99–103.

- Kissau, S., Yon, M., & Algozzine. (2011). The beliefs and behaviors of international and domestic foreign language teachers. Journal of the National Council of Less Commonly Taught Languages, 10, 21–56.

- Klassen, R. M., & Krawchuk, L. L. (2009). Collective motivation beliefs of early adolescents working in small groups. Journal of School Psychology, 47(2), 101–120.

- Krashen, S. (1985). The input hypothesis. Harlow, UK: Longman.

- Lachance, J., (2015, November). North Carolina teacher preparation: Transformations for dual language learning. Paper presented at La Cosecha Conference, Albuquerque, NM.

- Liebtag, E., & Haugen, C. (2015). Shortage of dual language teachers: Filling the gap. Retrieved from http://blogs.edweek.org/edweek/global_learning/2015/05/shortage_of_dual_language_teachers_filling_the_gap.html

- Lindholm-Leary, K. J. (2001). Dual language educaiton. Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

- Lindholm-Leary, K. J. (2012). Successes and challenges in dual language education. Education, Theory Into Practice, 51(4), 256–262. doi:10.1080/00405841.2012.726053

- Loeb, S., Soland, J., & Fox, L. (2014). Is a good teacher a good teacher for all? Comparing value-added of teachers with their English learners and non-English learners. Education Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 46, 457–475. doi:10.3102/0162373714527788

- Lopez, F. (2010). Identity and motivation among Hispanic ELLs. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 18, 16. doi:10.14507/epaa.v18n16.2010

- Manning, M. L., & Bucher, K. T. (2012). Teaching in middle school (4th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson Education.

- McKay, D. W. (2011). Dual language programs on the rise. Marvard Education Letter, 27(2). Retrieved from http://hepg.org/hel-home/issues/27_2/helarticle/dual-language-programs-on-the-rise

- McKenna, M. C., & Robinson, R. D. (1990). Content literacy: A definition and implications. Journal of Reading, 34(3),184–186.

- Merriam, S. (1998). Qualitiative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Migration Policy Institute. (2015). ELL fact sheet no. 5: States and districts with the highest number of English learners. Washington, DC: Author.

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Miller, N., Thompson, N., Cook, C., Howell, P., Faulkner, S., & Rintamaa, M. (2016, April). The complexities of middle level teacher certification: Status report and future directions. Poster session presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Educational Research Association, Washington, D.C.

- Modern Language Association of America. (2007). Foreign languages and higher education: New structures for a changed world. Profession, 234–245.

- Molle, D., Sato, E., Boals, T., & Hedgspeth, C. A. (2015). Multilingual learners and academic literacies: Sociocultural contexts of literacy development in adolescents. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Moore, J., & Schleppegrell, M. (2014). Using a functional linguistics metalanguage to support academic language development in the English Language Arts. Linguistics and Education, 26, 92–105. doi:10.1016/j.linged.2014.01.002.

- Morales, P. Z., & Aldana, U. (2010). Learning in two languages: Programs with political promise. In P. Gándara & M. Hopkins (Eds.), Forbidden language: English learners and restrictive language policies (pp. 159–174). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- National Middle School Association (NMSA). (2010). This we believe: Keys to educating young adolescents. Westerville, OH: Author.

- Ovando, C., & Collier, V. (1998). Bilingual and ESL classrooms: Teaching in multicultural contexts. Boston, MA: McGraw Hill.

- Powell, S. D. (2011). Introduction to middle school. Boston, MA: Pearson.

- Public Schools of North Carolina (NCDPI). (2015a). Dual language and immersion programs. Retrieved from http://wlnces.ncdpi.wikispaces.net/Dual+Language+%26+Immersion+Program.

- Public Schools of North Carolina (NCDPI). (2015b). Guidance for language instruction educational program (LIEP) services. Retrieved from http://eldnces.ncdpi.wikispaces.net/LEP+Coordinators.

- Public Schools of North Carolina (NCDPI). (2016). Dual language and immersion programs. Retrieved from http://wlnces.ncdpi.wikispaces.net/Dual+Language+%26+Immersion+Program.

- Purkey, W. W. (1970). Self-concept and school achievement. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill/Prentice Hall.

- Reyes, S. A., & Kleyn, T. (2010). Teaching in 2 languages: A guide for k-12 bilingual educators. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin.

- Rhodes, N., & Pufahl, I. (2009). Foreign language teaching in U.S. schools: Results of a national survey. Retrieved from http://www.cal.org/projects/Exec%20SumRosanna_111009.pdf.

- Ryan, A. M., & Shim, S. S. (2008). An exploration of young adolescents’ social achievement goals and social adjustment in middle school. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(3), 672–687.

- Saldaña, J. (2016). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Seidman, I. (2013). A guide for researchers in education and the social sciences (4th ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- The State Board of Education, North Carolina (NCSBE). (2013). Preparing students for the world: Final report of the State Board of Education’s task force on global education. Retrieved from http://www.ncpublicschools.org/curriculum/globaled/.

- Stringer, E. T. (2014). Action research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Thomas, W. P., & Collier, V. P. (2012). Dual language education for a transformed world. Albuquerque, NM: Fuente Press.

- Thomas, W. P., & Collier, V. P. (2014). Creating dual language schools for a transformed world: Administrators speak. Albuquerque, NM: Fuente Press.

- U.S. Department of Education Office of English Language Acquisition [OELA]. (2015). Dual language education programs: Current state policies and practices. Retrieved from http://www2.ed.gov/about/offices/list/oela/resources.html.

- van Lier, L. (2004). The ecology and semiotics of language learning: A sociocultural perspective. Dordrecht, NL: Kluwer Academic.

- Valentino, R. A., & Reardon, S. F. (2015). Effectiveness of four instructional programs designed to serve English language learners: Variation by ethnicity and initial English proficiency. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. Retrieved from https://cepa.stanford.edu/content/effectiveness-four-instructional-programs-designed-serve-english-language-learners

- Vars, G. F. (1969). Teacher preparation for the middle schools. High School Journal, 53(3), 172–177.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wolcott, H. F. (2001). Writing up qualitative research (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Wong-Fillmore, L. (2014). English language learners at the crossroads of education reform. TESOL Quarterly, 48(3), 624–632. doi:10.1002/tesq.174

- Wong-Fimmore, L., & Fillmore, C. J. (2012). What does text complexity mean for English learners and language minority students? Stanford University, Graduate School of Education, Understanding Language Project. Retrieved from www.ell.stanford.edu.

- World-class Instructional Design and Assessment [WIDA]. (2012). The 2012 amplification of the English language development standards, kindergarten to grade 12. Madison, WI: Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin on behalf of the WIDA Consortium.

- World-Class Instructional Design and Assessment [WIDA]. (2007). English language proficiency standards and resource guide, prekindergarten through grade 12. Madison, WI: Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin on behalf of the WIDA Consortium.

- Yin, R. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods (5th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: SAGE Publications.

- Zadina, J. N. (2014). Multiple pathways to the student brain. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.