Abstract

This article explores how international-mindedness is defined and cultivated in the International Baccalaureate (IB) Middle Years Program (MYP) schools in different regions of the world as young adolescents face their main developmental task of identity development. An online survey that contained demographic and open-ended questions was administered to MYP students. Mixed methods design and data analysis provided insight into the ways international-mindedness is experienced and developed within the IB community. Open-ended responses were analyzed using thematic analysis from which a grounded theory emerged. The most frequently mentioned themes in defining international-mindedness were understanding, awareness, and acceptance of different others. Respondents emphasized that family and school experiences were the main factors that influenced their international-mindedness with travel being frequently mentioned in both. Factors, such as make-up of participants’ families, their history of moving internationally, and the advice and modeling provided by parents and extended family as well as school experiences (e.g., field trips, debates, multicultural classrooms, curriculum focus) significantly contributed to their high self-ranked stance on the developmental continuum of international-mindedness. Consistency in responses across the regions demonstrate a paradigmatic understanding of international-mindedness among the respondents.

Introduction

Globalization requires special attention to global competency (e.g., Boix Mansilla, Citation2016; Mansilla, Jackson, & Jacobs, Citation2013), which is important to develop in the middle grades when students further develop reflectivity, self-awareness, and critical thinking and construct their identities in relation to a broader world (e.g., Andrews & Conk, Citation2012; Johnson et al., Citation2011; Wigfield et al., Citation2005a, Citation2005b). This article focuses on how young adolescent students define and perceive the development of international-mindedness as part of their cultural identity and what significant factors contribute to the development of international-mindedness among students in the International Baccalaureate (IB) Middle Years Programme (MYP).

A global network of the IB schools has been conceptualizing and developing international-mindedness “to develop inquiring, knowledgeable and caring young people who help to create a better and more peaceful world through intercultural understanding and respect” (International Baccalaureate Organization, Citation2020, n.p.). The concept of international-mindedness was introduced in IB schools in the 1960s as one of the major attributes of a learner in a complex and ever-changing world. Since then, it has become an integral part of IB pedagogies (e.g., Barratt Hacking et al., Citation2017, Citation2018; Muller, Citation2012; Singh & Qi, Citation2013). Over time, the concept of international-mindedness has evolved as the organization has sought to refine and enhance its approach to education (Beek, Citation2019), which will be further discussed in the article.

Though international-mindedness is being developed at all IB grade levels, this article acknowledges the crucial importance of the middle grades in students’ development (Feinstein & Bynner, Citation2004) and, thus, focuses on how international-mindedness is being developed in the MYP. Through personal accounts of young adolescents and teachers from around the world, the study identified factors that enhance international-mindedness in the MYP and the ways in which international-mindedness is being developed and implemented. The article concludes with a discussion of tensions in developing adolescents’ identity that include international-mindedness and suggestions for middle grades educators and teacher trainers based on best practices in IB schools. Findings from this article offer insights into how the concept of international-mindedness assists students and their teachers in developing important characteristics of a global citizen. Accordingly, the research questions that guided this inquiry were: How do young adolescents in the IB MYP define international-mindedness and perceive their level of international-mindedness as part of their identity? and What factors do IB MYP students perceive to support the development of IM as part of their cultural identity?

Literature Review

This section discusses theories underlying the investigation of the development of international-mindedness in the middle grades through the lens of identity formation. Further, it examines the concept of international-mindedness and its significance in the IB’s philosophy, and a recent shift in its perception. Thus, this literature review provides a contextual and conceptual framework that demonstrates the need for the study to be focused on this specific age group and grounds the study in the pertinent knowledge bases (Rocco & Plakhotnik, Citation2009).

Crucial Years for Identity Formation

Adolescence is the unique time in human development in which identity construction is the central developmental task (Erikson, Citation1968; Marcia, Citation1980; Phinney, Citation1993). The identity construction process during adolescence is defined by an increased capacity for abstract thought and motivational abilities (Doremus-Fitzwater et al., Citation2010; Luna et al., Citation2004); exploration of and experimentation with identity; orientation toward peers rather than adults; heightened search for autonomy and self-reliance; focus on dating and sexual relationships; and growing awareness of individual abilities and achievements (Eccles et al., Citation1983; Hill, Citation2012). Additionally, greater variability in development than during childhood occurs when adolescents become especially sensitive to issues of gender and ethnicity (Paulson et al., Citation1998).

All these intensified processes occur as the brain takes an immense leap in its development. The contributions to brain research demonstrate that the adolescent’s brain is different from both the child’s brain and the adult’s brain in morphology and function (Blakemore, Citation2012; Doremus-Fitzwater et al., Citation2010; Gogtay & Thompson, Citation2010; Paus, Citation2005; Schmithorst & Yuan, Citation2010; Wahlstrom et al., Citation2010) and in brain activity (Feinberg & Campbell, Citation2012; Ochsner et al., Citation2012; Romeo, Citation2010; Segalowitz et al., Citation2010; Wahlstrom et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, these differences are consistent with the findings of behavioral scientists (Blakemore, Citation2008; Dahl, Citation2004; Gogtay & Thompson, Citation2010). Gotgay and Thompson also observed that early adolescence is a time of considerable brain plasticity, which implies contextual dependability of brain structure and function that is connected to differences in experience (Steinberg, Citation2010). This finding is critical to this study in that it highlights adolescents’ experiences as important contexts for development. Research confirms that all aspects of identity formation follow steep developmental trajectories in adolescence. Not only is the physiology of the young adolescent undergoing unprecedented change, but young adolescents also experience tremendous change in social experiences.

Important for this study are the findings from the research of the development of cultural (Arnett Jensen, Citation2003; Jensen et al., Citation2011; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, Citation2007) and ethnic identity (French et al., Citation2006; Phinney & Ong, Citation2007) in early adolescence. Findings from these lines of research align with findings from brain research in highlighting the significance of school context and the correlating variability in developmental trajectories among racial and ethnic groups during early and middle adolescence. Globalization processes offer adolescents more opportunities to interact with people in different parts of the world, and researchers (Arnett Jensen, Citation2003; Jensen et al., Citation2011; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, Citation2007) have found that adolescents increasingly form multicultural identities when they grow up exposed to diverse cultural beliefs, practices, and behaviors that they experience either first-hand or virtually. Their developmental paths take different trajectories depending on the particular cultures involved.

Thus, the process of developing a cultural identity becomes more complex as a new task for adolescents emerges—navigating multiple cultural identities (Jensen et al., Citation2011). People may develop an intercultural identity (e.g., Kim, Citation2018; Tian & Lowe, Citation2014) or a multicultural identity (e.g., Benet-Martínez & Hong, Citation2014; Moore & Barker, Citation2012) as elements of cultural identity, or they may develop a new, more complex identity in which the participants define themselves as world citizens and are able to interact appropriately and effectively in many countries or regions with representatives of different cultures. These definitions provide us with a helpful description of what international-mindedness means.

International Baccalaureate as a Context for Developing International Mindedness

International Baccalaureate Organization (IBO) in its documents demonstrates a strong commitment to developing international-mindedness as a part of its philosophy that permeates “values, attitudes, knowledge, understanding and skills” (Singh & Qi, Citation2013, p. viii) expressed through (a) multilingualism, (b) intercultural understanding, and (c) global engagement. Four programs—Primary Years Program (PYP), Middles Years Program (MYP), Diploma Program (DP), and Career-related Program (CP)—serve students aged 3–19, challenge them to excel in their studies, and encourage both personal and academic success.

Due to the unique IBO structure that, as of February 2021, involves 1.4 million students in 5,400 schools in 158 countries, many schools serve an extremely diverse population of students, including children of expatriates and diplomats (International Baccalaureate Organization [IBO], Citation2021). Therefore, international-mindedness is not only embedded in the IBO philosophy that is reflected in its academic curriculum, but also serves as a formal and informal context for collaboration within IBO community as well as extending to families and communities as articulated by Singh and Qi (Citation2013).

Singh and Qi’s (Citation2013) identified five key concepts that give shape to the meaning and development of international-mindedness in IB.

Planetary intellectual conversations: affect the transcontinental, transnational sharing, borrowing and use of resource portfolios that include institutional developments, key ideas and technological discoveries.

Pedagogies of intellectual equality: start with the presupposition of “intellectual equality” between Western and non-Western students, and between Western and non-Western intellectual cultures, then set out to do what it takes to verify this premise.

Planetary education: involves (re)imagining the planet in its entirety, wherein there are no “others” — no “them” — only “we-humans” (Bilewicz & Bilewicz, Citation2012, p. 333) who are committed to redressing the impacts of “we-humans” on the world as a whole.

Post-monolingual language learning: works to pull multilingualism free of the dominance of monolingualism through teaching for transfer based on the cross-sociolinguistic similarities between students’ first language and the target language.

Bringing forward non-Western knowledge: works to verify the presupposition that Western and non-Western students can use the linguistic resources of Western and non-Western intellectual cultures to further IM, and in particular planetary education. (p. xii)

These concepts helped frame the analysis of data in this study and provide a broader meaning to MYP students’ perceptions.

Defining International-Mindedness

Defining the concept of international-mindedness has proven to be challenging for many educators and researchers (e.g., Harwood & Bailey, Citation2012). There are multiple varying definitions that tend to stress different aspects of the concept and relate it to notions such as internationalism or cosmopolitanism (Haywood, Citation2007, Citation2015) or analyze it in terms of specific regional contexts (Baker & Kanan, Citation2005; Lai et al., Citation2014; Metli et al., Citation2018; Tamatea, Citation2008). Most of the definitions emphasize the importance of action. The following definitions present ways in which researchers reflect the IB population’s perception of international-mindedness:

Definition 1:

[International-mindedness] embraces knowledge about global issues and their interdependence, cultural differences, and critical thinking skills to analyze and propose solutions. International mindedness is also a value proposition: it is about putting the knowledge and skills to work in order to make the world better place through empathy, compassion and openness – to the variety of ways of thinking which enrich and complicate our planet (Hill, Citation2012, p. 246).

Definition 2:

[International-mindedness] is an understanding that individuals can improve the state of the world through understanding of global realities, and the accompanying acceptance of the responsibility to take action to do so (Muller, Citation2012, p. 26).

Definition 3:

[International-mindedness is] an outlook of being globally engaged through intercultural understanding that compels individuals to work toward peace, equality, and sustainability (Beek, Citation2019, p. 22).

These three definitions reflect the current tendency to embrace international-mindedness’s traditional definition, but also move toward aligning it with more recent global developments toward “peace, equality, and sustainability” (Beek, Citation2019, p. 22). Traditionally, international-mindedness has been defined by IB as a unity of multilingualism, intercultural understanding, and global engagement (Sriprakash et al., Citation2014). Hill’s (Citation2012) and Muller’s (Citation2012) definitions underscore these features (except for multilingualism) as part of an active stance (i.e., working to make the world a better place and taking action on it). However, a new approach is emerging based on the principles that incorporate the most recent foci in globalization—sustainabledevelopment, awareness of global issues, international cooperation, and understandings between individuals (Wright & Buchanan, Citation2017). The influence of this new approach is evident in the definition by Beek (Citation2019). These definitions serve as a baseline when analyzing voices of IB students to examine how they understand international-mindedness and what factors help them develop it. The history of the concept is comprehensively analyzed by Hayden and Thompson (Citation2013).

In sum, development of international-mindedness in this study is viewed as part of the construction of the cultural identity. The Eriksonian approach positions the problem of identity development as the most important task to solve in adolescence and, thus, justifies the focus of this study on the development of adolescents’ identity. Identity negotiation theory (Ting-Toomey, Citation2005), which will be discussed next, offers a framework to explain the complexity of identity development, especially in increasingly globalized world that adds different facets to cultural identity such as multicultural and intercultural. Experiencing and effectively communicating in different (including international) contexts support the development of a complex multifaceted identity that is able to thrive in the ever-expanding world. Language reflects developmental processes in identity construction and represents their multifaceted nature, thus, serving as an illuminating tool in analyzing identity formation. International-mindedness as a part of multifaceted cultural identity that IB aims at developing in order to respond to the needs of globalization, serves as a quintessential concept that permeates the IB philosophy of education as reflected in the Learner Profile attributes (IBO, Citation2013) and other documents of the organization.

Identity Negotiation Theory

Identity negotiation theory (Ting-Toomey, Citation2005) explains the identity construction process through developmental stages of identity formation that are achieved through experience and communication. In a nutshell, the theory assumes that human beings in all cultures desire both positive group-based and person-based identities in any type of communicative situation. To achieve that, their identity formation goes through several stages: (a) pre-encounter, (b) encounter, (c) immersion-emersion, and (d) internalization-commitment (Helms, Citation1993). The assumptions of the theory emphasize that:

mindful intercultural communication has three components: knowledge, mindfulness, and identity negotiation skills; that mindfulintercultural communication refers to the appropriate, effective and satisfactory management of desired shared identity meanings and shared identity goals in an intercultural episode; and that competent identity negotiation outcomes include the feelings of being understood, respected, and affirmatively valued. (Ting-Toomey, Citation2005, p. 226)

It is important to consider that both culture-general and culture-specific knowledge can enhance our positive attitudes and constructive interaction skills in dealing with people who are culturally different. Ting-Toomey (Citation2005) defined an intercultural identity negotiation competence that develops when participants are mindful of what is going on in their “thinking, feeling, and experiencing” (p. 226), which involves shifting of perspective.

To conclude, developing an intercultural identity has become a more complex process; it is no longer a question of becoming an adult member of one culture but instead it is figuring out how to negotiate different cultures. We no longer have the Eriksonian task of identity formation that focuses on the process of developing one’s identity within their own cultural community; today, the construction of a cultural identity involves effective communication and collaboration with multiple cultural communities. Important to underscore for this study that “language constitutes a key part of one’s (multi)cultural identity” (Jensen, Citation2011, p. 64) and not only influences the cultural identity development of many adolescents (Jensen, Citation2011), but also reflects the developmental processes that occur as a result of globalization.

Methods

The present study employed a mixed-methods design to generate grounded theory about how young adolescents in the IB MYP conceptualize international-mindedness and perceive themselves as being international-minded. The study also explored factors MYP students identify as influential in developing international-mindedness.

Data Collection

This study was a part of a larger international project involving the whole IB population of students and educators across all the programs on all the continents initiated in 2015. An online survey with demographic and open-ended questions was administered randomly to IB students (n = 667), educators (n = 615), and alumni (n = 554) using three versions of the survey to capture these groups’ common and specific experiences(see Appendix A). The responses of alumni and students related primarily to their experiences as IB students, while educators mainly talked about their experiences working for IB. The overall response rate for students and educators was 69% and 61%, respectively. The sample was drawn from IB schools in all regions, including South, Central, and North America, Europe, Middle East, Africa, Asia, and Australia. Students and teachers in schools that expressed interest in participating received an individual link to the survey, and parental consent was acquired for all students who agreed to participate. Links were distributed on a rolling schedule to schools and contacts in all IB regions, and data was collected for seven months. Participants were offered the choice of taking the survey in English, Spanish, or French; Spanish and French responses were translated into English for analysis.

The focus of this study was students aged 12–16 in the MYP. Responses from the MYP students (n = 136) were extracted from the larger data set and analyzed. The MYP student responses represented 20. 5% of all participating students. Most students who responded to the survey were female, identified as White, and completed the survey in English).

Data Analysis

Data were analyzed with a qualitative coding process (Saldaña, Citation2009) that yielded a hierarchy of 129 themes including 28 main themes and 101 subthemes. Examples of key themes included Acceptance of Different Others, Developing Awareness, Grasping Multiple Perspectives, Moving/Living Away from Home, Traveling when Young, and Diverse Student/Educator Population. The themes were further refined and organized into larger groups through axial coding and thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014; Nowell et al., Citation2017). Patterns and comparisons among themes were explored through the use of matrices and queries created with NVivo 10 software tools (Bruckner, Citation2016). Secondary analysis was performed with the data from the MYP using manual open, axial, and theoretical coding of the responses by following the four steps in the process of analysis and theory-building: (a) comparing incidents applicable to each category, (b) integrating categories and their properties, (c) delimiting the theory, and (d) writing the theory (Glaser & Strauss, Citation2017).

Findings

The report of findings begins with MYP students’ perceptions of international-mindedness and a thematic analysis of international-mindedness definitions they provided. Next, the major factors that contribute to the development of international-mindedness are identified. Finally, challenges to developing IM evident in the data are reported.

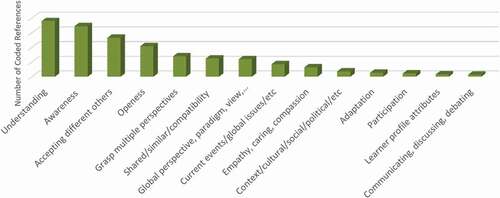

Student Perceptions and Definitions of International-Mindedness

IB students self-assessed the degree to which they believed they were internationally minded on a scale of 1 (not internationally minded) to 10 (highly internationally minded). Eighty-six percent of MYP students rated their level of international-mindedness between 7 and 10; most rated themselves at 8. Their constructed definitions stem from their experiences with international-mindedness and serve as evidence of their understanding of international-mindedness. Student definitions of international-mindedness contain many common ideas that they express in longer descriptions or short and concise statements (see ). Their definitions are grounded in their self-perception of learner identity, and many of them align themselves with the IB Learner Profile.

MYP students often expressed knowledge of and passion about being internationally minded. For example, one student stated:

An internationally minded learner is above all a competent communicator, open-minded and knowledgeable. However, these qualities cannot be achieved without the remaining seven attributes, which fall into the two categories of cognitive competence (inquirers, thinkers and reflective practitioners), and disposition (principled, caring, risk-takers, and balanced). (MYP student, Iran)Footnote1

Others defined international-mindedness in more globally-oriented and culture-general terms (i.e., looking broadly at the world without defining specific personal connections) and related IM to the peaceful future in the world as suggested by Singh and Qi’s (Citation2013) concept of planetary intellectual conversations. For example,

International mindedness is a programme, which helps us to maintain a better relation between other people throughout the world. It is a programme, which is there for a successful and peaceful future. This makes the world equal and happy. (MYP student, India)

Other young adolescents were more culture-specific (i.e., their personal culture) and defined international-mindedness coming from their inner self. For example, a student wrote, “[It is] being open minded about other cultures and willing to learn about the world” (MYP student, New Zealand). Some related international-mindedness to being understanding and respectful, though clearly separating “exotic cultures” from their own: “[It is] when one is open-minded about the variety of cultures around them. International-mindedness is understanding, respecting, and appreciating the diverse and exotic cultures, values, perspectives around them” (MYP student, Oman).

Many MYP students stressed knowledge of the world, the characteristic that Ting-Toomey (Citation2005) acknowledges as an important component of being able to negotiate your identity. A student wrote, “Having a well-rounded opinion on global situations. Being open minded. Not discriminating, and treating all nationalities and ethnicities the same” (MYP student, United Kingdom).

For many students, being internationally minded means seeing themselves as a part of the global community. One MYP student shared that IM refers to “the way in which we see ourselves in a worldwide community of different cultures, beliefs and values” (MYP student, Australia).

MYP students seem to perceive international-mindedness as a learner attribute that is demonstrated in being open-minded, respectful, curious, knowledgeable, and understanding of other cultures, and they tend to identify themselves as a part of the worldwide community. However, their accounts do not seem to include a need for acting upon their beliefs and values, which is predictable as at this age they engage in developing their values and attitudes in preparation to act on them in the future (Roberts et al., Citation1999).

Factors Contributing to International-Mindedness

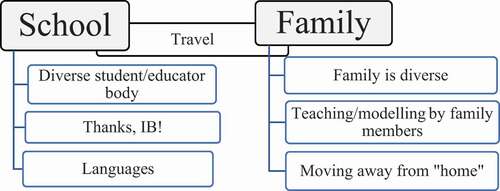

Among the factors students reported contribute to their development of international-mindedness, school and family factors stand out as most influential. Travel appears as a theme under both family and school as one of the leading factors and is treated separately in this report. These three major groups of factors—travel, school factors, and family factors—are discussed in the upcoming sections.

Travel

Travel was the most frequently mentioned experience strongly associated with the development of international-mindedness. In fact, travel was present as a theme in responses to multiple survey questions including those about family and school. Participating students reflected on their experiences traveling with parents, their history of moving to different locations (usually internationally), and their travels abroad to visit family and friends. Students shared their experiences traveling through exchange programs and field trips and communicating virtually with other IB schools from different parts of the world. In responses to the survey question asking for recommendations on further development of international-mindedness, traveling to take part in IB exchanges, service trips, interscholastic competitions, and other travel opportunities was the most frequently appearing theme.

School

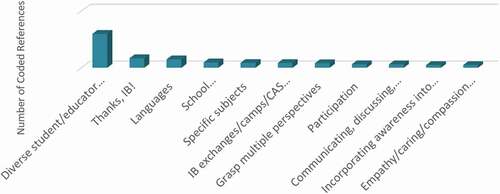

The responses provided plentiful data confirming the influence of school experiences for developing international-mindedness (see ). Because of the breadth of content in responses to the question about school influence, only most frequently mentioned themes are chosen for discussion—diverse student/educator body, curriculum/extracurricular activities, and learning other languages.

Primarily, the responses underscored the diversity in IB schools as an asset related to international-mindedness development. In most IB schools, students and teachers come from all over the world, allowing them to engage in Singh and Qi’s (Citation2013) notion of planetary education. One student highlighted this unique environment, noting that IB schools have “students and teachers from all over the world, global curriculum, [and] overseas camps” (MYP student, Indonesia).

The diversity of IB teachers is a unique feature of the schools’ network. As students mentioned, their experiences are shaped by the worldview that teachers hold. Teachers who participated in the survey for the larger data set from which this study is derived tended to rate themselves as being internationally minded. On a scale of 1 (lowest) to 10 (highest), 86.4% of educators rated themselves between 7 and 10 for international-mindedness. Some of them jokingly put 11, meaning that they are more internationally minded than the offered scale could measure.

Students’ responses related to curriculum and extracurricular activities were included in the theme, Thanks, IB! Not only did students note how a multi-cultural environment influenced international-mindedness development, they also discussed how pedagogy and structure of the curriculum contributed to the process. A unique vehicle for incorporating international-mindedness development is the IB subject area curricula that are developed and updated every seven years based on the newest findings in educational research. Often, curricula in IB schools are integrated, as is described by a young adolescent from Peru in the following example:

In my school, we have two events in the month of November: “Art for your senses” and “Techno-sciences” […]. Arts for your senses include courses in English, communication, and art, while “Techno-sciences” includes mathematics, science and computers. In a full day of classes, the works we do during the year of these subjects are exhibited throughout the school, projects are prepared, tested, games and others are presented, like a fair. It is a very fun day in which we have the opportunity to be both exhibitors and the public. Another activity that takes place in the month of July is the Day of the Fatherland, commemorating Peruvian independence. We are participants of artistic and cultural performances in relation to the country, as well as a parade. In addition, as part of thehHistory course (upper level), bimonthly, we organize a cultural sharing by classrooms, according to the topic that we have dealt with throughout the period. For example, if we study the Mexican Revolution, we would present about issues related to it, while sharing typical food of the place that we ourselves bring. (MYP student, Peru [translated from Spanish])

Many students mentioned an event called Model United Nations (MUN) as an important factor in international-mindedness development, as well as other school-organized events (e.g., charity events, bake sales, sports events, open day, community day). For example, a student shared:

School events that contributed to becoming internationally minded are MUN[…] which took place in my previous school. To add on what helped me become internationally minded are school events such as plays, beginning of the year welcoming events. These types of events helped me become internationally minded because you talk a lot and meet new people from your school which come from different countries and cultures. This makes you learn a lot about not only the person you are talking to but also about their traditions, cultures, countries and more. (MYP student, Morocco)

Teachers immerse students in the teaching/learning of different cultures in a variety of subject areas and school events, giving them opportunities to practice the skill of looking at international issues from multiple perspectives, a key quality of internationally minded people. By participating in these consistent and interrelated opportunities, young adolescents learn formally and informally about different cultures and enhance their intercultural communication skills.

IB students benefit from learning several languages, both formally in the classroom and informally from their friends and environments through a process Singh and Qi (Citation2013) called post-monolingual language learning. Language classes—and multilingualism itself—are also highlighted as effective means for developing international-mindedness in a school environment. Young adolescents’ orientation to peers, expressed in the need to create a strong bond no matter what your first language is, seems to be impactful in developing international-mindedness. For example, one student reflected:

My school is very diverse; this has helped. I get to meet new people from different countries and we get to meet, talk and develop bonds, which do lead to sharing culture in forms of food mainly. Another great experience was an interschool cricket tournament. Our team consisted of many countries and many of us has not even spoken to each other before. But during practices and matches we developed a bond, as we spent a lot of time together, which slowly over those three months made me appreciate the other person’s culture. (MYP student, India)

This situation put students from many countries together on one team that allowed them to interact and share. Although the student seemed to enjoy the process, he/she noticed that it takes a long time to create a bond.Another student noted how common classroom experiences like learning a foreignlanguage bring students closer to peers from other cultures. The student commented, “I’ve learned a second language and I am learning with people from other countries and cultures” (MYP student, Slovakia).

Overall, participants described a multitude of specific instances when they experienced the process of becoming more internationally minded during multiple school events, through curriculum, and having teachers and peers who originated from many different countries. They also affirmed the cumulative impact of such experiences as they contribute to the development of international-mindedness.

Family

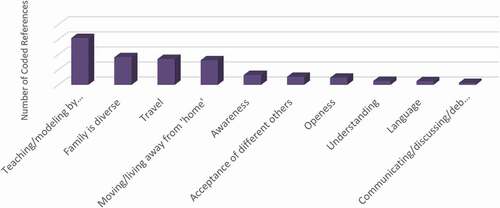

MYP students emphasized that family experiences, such as make-up of their families, their history of moving internationally, and the advice and modeling provided by parents and extended family were major factors in developing international-mindedness (see ).

One student shared:

First of all, my family background helped me so much, I’ve learned caring for different people and cultures, and not only thinking about myself, from my parents and grandparents and their knowledge and education has had a lot of effect. Also travelling to different countries has helped me so much, and I’ve learned different things from them. (MYP student, Iran)

Other students mention staying in touch with their family roots through travel. For example, one student noted:

My family loves to travel, and so I have been lucky enough to visit places such as England, Scotland, Amsterdam, Canada, Italy, and many of the States. My mom’s side of the family is also very in touch with their Polish roots, so I have grown up with some Polish customs and traditions. These experiences have led to the expansion and development of my international mindedness. (MYP student, USA)

MYP students also shared how their families help them better understand what is going on in the world. A student wrote:

The fact that my grandfather is Palestinian, connected to the current situation in that country, generated more awareness of what is happening in other places; it makes us part of the global situation and gives us the ability to reflect upon the fact that just because it does not happen here, it doesn’t mean it’s not happening. (MYP student, Colombia)

These examples highlight rich family contributions to IM development through teaching, modeling, sharing opinions, traveling together, discussing their heritage, and celebrating family members’ traditions. However, some participant responses revealed how and why their families tended to discourage an international-mindedness approach to life. The following subthemes were noted among participants who reported their families had little or no influence on their development of international-mindedness because they acted as ethnocentric, closed-minded, or prejudiced. Interestingly enough, while family stance aimed at hindering or preventing international-mindedness development, a subset of respondents specified that these qualities provided them with motivation for developing a more open, accepting, and globally informed perspective and thus indirectly moved them toward international-mindedness. For example,

[My] Family background had little to no effect on my international mindedness, in fact, i often find myself strongly disagreeing with most of my parent’s opinions. In terms of life experience, I think that school and social media were two of the main factors of how i see the world today. Being in an international school, i was constantly and from a very young age, surrounded by students and faculty with backgrounds and ethnics different to my own, regardless of where i was in the world. This meant i was always learning and growing because of the people around me. (Diploma Program and former MYP student, United Arab Emirates)

Some participants noted that they grew up in isolated, homogenous, insular, or mono-cultural environments, often in rural areas, small towns, or villages. They related these environments to a lack of potential or support for the development of international-mindedness. Some families never traveled and/or had no interest in or no resources for traveling, which, according to participants, limited their IM development. Others noted that lack of diversity in their extended families were not contributing factors, frequently citing “traditional” or “conservative” values as the cause. A number of participants described feelings of resentment toward their families concerning these limitations, saying this drove them to seek out a more international-mindedness lifestyle for themselves.

To summarize, according to the participating students’ reports, nuclear and extended families were perceived as having a strong influence—both positive and negative—on the students’ formation of international-mindedness. The family factor was construed based on the major categories such as make-up of their families, their history of moving internationally, and teaching/modeling by family members. Responses that claimed no influence or a negative influence on international-mindedness development were just a few exceptions that stood out from the patterns of overwhelmingly strong positive accounts.

Challenges to Cultivating International-Mindedness

The overwhelming majority of responses assigned high value to the development of international-mindedness and described positive experiences and conducive environments for its development, especially highlighting schools’ and families’ support. However, a few comments reflected problematic perceptions and experiences with international-mindedness. These comments are important to consider because of their ability to point out areas that require attention. Challenges mentioned include absence of impact or little impact when participants did not feel their IB experiences helped them in developing international-mindedness. Some described limitations in their IB experience that detracted from their international-mindedness development. For example, a few students pointed out that the presence of a diverse student population in an international school does not automatically yield the development of an international approach; rather, the school must work more at inspiring students in this area. Along with these general considerations about the international-mindedness process as a whole, some students pointed to specific issues they wished to highlight. In particular, they expressed concern about tokenistic aspects in the development of international-mindedness that they observed at their IB schools and suggest getting students to engage with global issues on a less superficial level. Western bias in the curriculum is also mentioned as a feature that does not contribute to developing international-mindedness. Another issue related to non-diverse schools that tend to be mono-cultural, which stems from their geographic location and student populations they serve. These schools might need to put more effort in developing international-mindedness. Though negative comments and stories make up only a small fraction of the sample studied, they provide a valuable reminder that prejudicial behaviors and attitudes are yet observable in some schools.

Participating students and educators offered their recommendations for meeting the challenges of international-mindedness development, including descriptions of effective practices. For example, a teacher from Australia offered a success story in finding a way to get beyond the overly Westernized curriculum approaches (see Singh and Qi’s (Citation2013) concept of Bringing Forward Non-Western Knowledge):

Using Skype to build relationships between a Hawaiian indigenous school and an Australian Aboriginal school. The focus was to enable students from limited backgrounds to develop an understanding of another culture that is relatable to students so that they developed a better understanding of the similarities across Indigenous cultures around the world. Through the sharing of experiences students were empowered to believe that they can actually effect change in their own circumstances through their own choices. (IB educator, Australia)

Another effective way to meet international-mindedness development challenges is to infuse international-mindedness in real life experiences that are based on authenticity and agency. Notably, one educator from Peru commented, “The best way to accept the International Mindedness is living with it.”

The main school and family factors discussed above are echoed in the many recommendations for improving international-mindedness development in IB, which include establishing and extending programs to enhance international travel for students and educators, ensuring a diverse student and teacher population at IB schools, developing a digital network to connect IB students and classrooms around the globe, and redoubling efforts to incorporate international-mindedness into the classroom so that understanding, awareness, and acceptance of others continues to grow. To further develop and assess the degree of students’ international-mindedness, educators need to create opportunities for students to practice and act on their beliefs.

Discussion

As young adolescents wrestle with their main developmental task of identity formation (Erikson, Citation1968), globalization that permeates society informs this process by construing identity as a multifaceted, cultural concept. Cultural aspects of identity formation include a young adolescent’s relationship to the world, often expressed in the notions of global competence (e.g., Andrews & Conk, Citation2012; Mansilla, Jackson, & Jacobs, Citation2013), global citizenship (e.g., de Andreotti, Citation2014; Davies, Citation2006), intercultural competence (e.g., Cushner, Citation2015), or international-mindedness (e.g., Castro et al., Citation2013; Singh & Qi, Citation2013; Wasner, Citation2016), to mention a few. This study attempted to capture how young adolescents in the IB MYP develop a sense of themselves in the world through the concept of intercultural-mindedness.

In their survey responses, MYP students shared thoughts about what international-mindedness means and offered recommendations for improving the process of developing international-mindedness in the MYP. Their responses reflect a high level of enthusiasm about their lived experiences. Common threads emerged from the numerous definitions, stories, and suggestions expressed by participants. Students’ patterns of defining international-mindedness and articulating main factors in its development were found to be consistent across all the regions, indicating a common paradigmatic understanding of international-mindedness existing in the IB community.

Before an adolescent identity expands to include intercultural and global facets, it begins developing in a family system where children both formally and informally learn from their immediate and extended family members the value systems and priorities that are important in their culture. This developmental process corresponds to the pre-encounter and encounter stages of identity construction (Ting-Toomey, Citation2005). This study confirmed a strong family influence on international-mindedness development as part of the adolescent identity.

Directions for Further Research

Interestingly, a few older adolescents in the IB Diploma Program indicated family had no impact or took a stance advocating against international-mindedness, and these respondents underscored school and peers’ support in helping them become internationally-minded. It would be interesting to further investigate the differences in appreciation of family influence by the age group, which was outside the scope of this study.

Jensen (Citation2011) examined the diverse cultural identities resulting from globalization, such as hybrid, marginalized, and bicultural identities. Future studies should explore what trajectories identity development takes beyond the MYP and what impact this stage of identity development has on its future outcomes. Especially important would be to compare identity development in middle level schools that embrace globalization, as IB schools do, and those that do not. As Arnett Jensen (Citation2003) noticed elsewhere, forming a cultural identity involves adopting the beliefs and practices—the custom complexities—of one or more cultural communities. How do adolescents go through this process? How do they develop knowledge and understanding for different communities? Do they act on the basis of familial and communal values, or their loyalty to spiritual beliefs, or their understandings of autonomy and independence? What do they internalize and what do they reject, and why? Such questions are also worthy of exploration.

Recently debates suggest variability in understanding international-mindedness in different schools and different countries, conceptualizing “international-mindedness as a benevolent form of character development” by some and “international-mindedness as an opportunistic form of social and global mobility” by others (Savva & Stanfield, Citation2018, p. 179). The debate highlights the capacity of international-mindedness to be reconfigured by different interest groups, which contributes toward the confusion in defining the concept (Skelton, Citation2015). The findings of this study speak to Savva and Stanfield’s concern by providing empirical data that challenges their supposition that schools’ interpretations of international-mindedness diverge from each other within the IB system of schools more than they converge. This study demonstrated quite the opposite.

With globalization, mass media provides open access to different worldviews that might create tensions between young adolescents and parents who adhere to traditional culture. Young adolescents may develop more egalitarian, independent, and agentic identities that contrast with parents’ perceptions of adolescents’ roles. Globalization and media make youths’ civic involvement possible; though, at the same time, it risks creating a tension between a civic (i.e., national) and global identity. Young adolescents in their identity construction process face challenges in resolving these tensions, among others. Developing IM in the IB MYP, as this study demonstrated, seems to provide a useful framework for students to resolve these challenges on their way to a comfortable, well-balanced, positive identity.

Conclusion

This study developed a grounded theory that includes two major categories—school and family—and multiple subcategories (see ) that interact to define the trajectories of MYP students’ identity construction in the global IB school network. Though the IB schools across the globe are more similar between themselves than with the schools belonging to the national educational systems, many practices of developing international-mindedness such as field trips, the use of technology to communicate with other schools in the world, creating an integrated curricula, and other supportive practices can be implemented in any other school.

The practices students perceived to be supportive of IM development can serve as an inspiration and provide a roadmap to applying them in other classrooms. Teacher trainers could develop modules that include tools for building integrated curricula permeated with multicultural contexts that extend beyond the academic time to include student action demonstrated in their service to the community and the world. More research needs to be done to identify regional similarities and differences in perceptions of IM by IB students and teachers. Such studies might investigate relationships between the concept of IM and related concepts of cosmopolitanism, cultural intelligence, global citizenship, global competence, global mindedness, intercultural understanding, multiliteracies, and world mindedness and explore how these concepts interrelate in national contexts.

Acknowledgments

The author performed this study while working at one of the IB Global Centres and is grateful to the International Baccalaureate Organization for making this research project possible. The author thanks Dr. Mary Beth Schaefer for her generous and insightful feedback on the development of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Countries listed are where the student resided at the time of the study, not the student’s nationality or country of origin.

References

- Andrews, P. G., & Conk, J. A. (2012). The world awaits: Building global competence in the middle grades. Middle School Journal, 44(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00940771.2012.11461840

- Arnett Jensen, L. (2003). Coming of age in a multicultural world: Globalization and adolescent cultural identity formation. Applied Developmental Science, 7(3), 189–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532480XADS0703_10

- Baker, A. M., & Kanan, H. M. (2005). International mindedness of native students as a function of the type of school attended and gender: The Qatari case. Journal of Research in International Education, 4(3), 333–349. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240905057813

- Barratt Hacking, E., Blackmore, C., Bullock, K., Bunnell, T., Donnelly, M., & Martin, S. (2017). The international mindedness journey: School practices for developing and assessing international mindedness across the IB continuum. International Baccalaureate Organization.

- Barratt Hacking, E., Blackmore, C., Bullock, K., Bunnell, T., Donnelly, M., & Martin, S. (2018). International mindedness in practice: The evidence from International Baccalaureate Schools. Journal of Research in International Education, 17(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240918764722

- Beek, A. E. (2019). An integral analysis of international mindedness. In V. B. Clarke (Ed.), Integral theory and transdisciplinary action research in education (pp. 65–86). IGI Global. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-5225-5873-6.ch004

- Benet-Martínez, V., & Hong, Y. Y. (Eds.). (2014). The Oxford handbook of multicultural identity. Oxford Library of Psychology.

- Bilewicz, M., & Bilewicz, A. (2012). Who defines humanity? Psychological and cultural obstacles to omniculturalism. Culture & Psychology, 18(3), 331–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1354067X12446234

- Blakemore, S. J. (2008). Development of the social brain during adolescence. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61(1), 40–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17470210701508715

- Blakemore, S. J. (2012). Imaging brain development: The adolescent brain. Neuroimage, 61(2), 397–406. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.11.080

- Boix Mansilla, V. (2016). How to be a global thinker. Educational Leadership, 74(4), 10–16. http://www.pz.harvard.edu/sites/default/files/Educational%20Leadership-The%20Global-Ready%20Student-How%20to%20Be%20a%20Global%20Thinker.pdf

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can “thematic analysis” offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Bruckner, K. (2016). Global definition of international mindedness within International Baccalaureate schools: A pitot study. [ Unpublished report]. International Baccalaureate Organization.

- Castro, P., Lundgren, U., & Woodin, J. (2013). Conceptualizing and assessing international mindedness (IM): An exploratory study. International Baccalaureate Organization.

- Cushner, K. (2015). Development and assessment of intercultural competence. In M. Hayden, J. Levy, & J. Thompson Eds., The SAGE handbook of research in international education (2nd ed., pp. 200–216). Sage. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473943506.n14

- Dahl, R. (2004). Adolescent brain development: A period of vulnerabilities and opportunities. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1021(1), 1–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1308.001

- Davies, L. (2006). Global citizenship: Abstraction or framework for action? Educational Review, 58(1), 5–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910500352523

- de Andreotti, V. O. (2014). Soft versus critical global citizenship education. In S. McCloskey (Ed.), Development education in policy and practice (pp. 21–31). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137324665_2

- Doremus-Fitzwater, T. L., Varlinskaya, E. I., & Spear, L. P. (2010). Motivational systems in adolescence: Possible implications for age differences in substance abuse and other risk-taking behaviors. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 114–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.008

- Eccles [Parsons], J., Adler, T. F., Futterman, R., Goff, S. B., Kaczala, C. M., Meece, J. L., & Midgley, C. (1983). Expectations, values and academic behaviors. In J. T. Spence (Ed.), Perspective 200 International Journal of Behavioral Development 35(3) on achievement and achievement motivation (pp. 75–146). W. H. Freeman.

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis (No. 7). WW Norton & Company.

- Feinberg, I., & Campbell, I. G. (2012). Longitudinal sleep EEG trajectories indicate complex patterns of adolescent brain maturation. American Journal of Physiology-Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology, 304(4), 296–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpregu.00422.2012

- Feinstein, L., & Bynner, J. (2004). The importance of cognitive development in middle childhood for adulthood socioeconomic status, mental health, and problem behavior. Child Development, 75(5), 1329–1339. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00743.x

- French, S. E., Seidman, E., Allen, L., & Aber, J. L. (2006). The development of ethnic identity during adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 42(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.1.1

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (2017). Discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Routledge.

- Gogtay, N., & Thompson, P. M. (2010). Mapping gray matter development: Implications for typical development and vulnerability to psychopathology. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.08.009

- Harwood, R., & Bailey, K. (2012). Defining and evaluating international-mindedness in a school context. International Schools Journal, 31(2), 77–86. https://education4internationmindedness-sais.weebly.com/uploads/3/1/3/4/31348255/april_2012_isj.pdf

- Hayden, M. & Thompson, J. (2013). International Schools: Antecedents, current issues and metaphors for the future. In R. Pearce (Ed.), International education and schools: Moving beyond the first 40 years (pp. 3–24). London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Haywood, T. (2007). A simple typology of international-mindedness and its implications for education. In M. C. Hayden, J. Levy, & J. J. Thompson Eds., The handbook of research in international education (1st ed., pp. 78–89). Sage Publications. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781848607866

- Haywood, T. (2015). International mindedness and its enemies. In M. Hayden, J. Levy, & J. Thompson Eds., The SAGE handbook of research in international education (2nd ed., pp. 45–58). Sage. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4135/9781473943506.n3

- Helms, J. E. (1993). Introduction: Review of racial identity terminology. In J. E. Helms (Ed.), Black and white racial identity: Theory research and practice (pp. 1–3). Praeger.

- Hill, I. (2012). Evolution of education for international mindedness. Journal of Research in International Education, 11(3), 245–261. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240912461990

- International Baccalaureate Organization. (2013). IB learner profile. http://www.ibo.org/contentassets/fd82f70643ef4086b7d3f292cc214962/learner-profile-en.pdf

- International Baccalaureate Organization. (2020). Mission. https://www.ibo.org/about-the-ib/mission/

- International Baccalaureate Organization. (2021). Facts and figures. https://www.ibo.org/about-the-ib/facts-and-figures/

- Jensen, L. A. (2011). Navigating local and global worlds: Opportunities and risks for adolescent cultural identity development. Psychological Studies, 56(1), 62–70. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s12646-011-0069-y

- Jensen, L. A., Arnett, J. J., & McKenzie, J. (2011). Globalization and cultural identity. In S. J. Schwartz, K. Luyckx, & V. L. Vignoles (Eds.), Handbook of identity theory and research (pp. 285–301). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-7988-9_13

- Johnson, P. R., Boyer, M. A., & Brown, S. W. (2011). Vital interests: Cultivating global competence in the international studies classroom. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 9(3–4), 503–519. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2011.605331

- Kim, Y. Y. (2018). Identity development: From cultural to intercultural. In H.B. Mokros Ed., Interaction and Identity, (4th ed., pp. 347–370). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351293525

- Lai, C., Shum, M. S., & Zhang, B. (2014). International mindedness in an Asian context: The case of the international baccalaureate in Hong Kong. Educational Research, 56(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2013.874159

- Luna, B., Garver, K. E., Urban, T. A., Lazar, N. A., & Sweeney, J. A. (2004). Maturation of cognitive processes from late childhood to adulthood. Child Development;, 75(5), 1357–1372. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00745.x

- Mansilla, V. B., Jackson, A., & Jacobs, I. H. (2013). Educating for global competence: Learning redefined for an interconnected world. Mastering Global Literacy, 5–27. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Oleksandr-Burov/publication/School_Students/links/5b3916a20f7e9b0df5e45341/Profile-Mathematical-Training-Particular-Qualities-Of-Intellect-Structure-Of-High-School-Students.pdf.

- Marcia, J. E. (1980). Identity in adolescence. Handbook of Adolescent Psychology, 9(11), 159–187.

- Metli, A., Martin, R. A., & Lane, J. F. (2018). Forms of support and challenges to developing international-mindedness: A comparative case study within a national and an international school in Turkey. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 49(6), 1–19. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2018.1490889

- Moore, A. M., & Barker, G. G. (2012). Confused or multicultural: Third culture individuals’ cultural identity. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 36(4), 553–562. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2011.11.002

- Muller, G. C. (2012). Exploring characteristics of international schools that promote international-mindedness. [ Doctoral dissertation]. Columbia University.

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- Ochsner, K. N., Silvers, J. A., & Buhle, J. T. (2012). Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: A synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1251(1), E1. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.2012.06751.x

- Paulson, S. E., Marchant, G. J., & Rothlisberg, B. A. (1998). Early adolescents’ perceptions of patterns of parenting, teaching, and school atmosphere: Implications for achievement. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 18(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431698018001001

- Paus, T. (2005). Mapping brain maturation and cognitive development during adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 9(2), 60–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.008

- Phinney, J. S. (1993). A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. Ethnic Identity: Formation and Transmission among Hispanics and Other Minorities, 61, 79. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271

- Phinney, J. S., & Ong, A. D. (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271

- Roberts, R. E., Phinney, J. S., Masse, L. C., Chen, Y. R., Roberts, C. R., & Romero, A. (1999). The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19(3), 301–322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431699019003001

- Rocco, T. S., & Plakhotnik, M. S. (2009). Literature reviews, conceptual frameworks, and theoretical frameworks: Terms, functions, and distinctions. Human Resource Development Review, 8(1), 120–130. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484309332617

- Romeo, R. D. (2010). Adolescence: A central event in shaping stress reactivity. Developmental Psychobiology: The Journal of the International Society for Developmental Psychobiology, 52(3), 244–253. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdfdirect/10.1002/dev.20437

- Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage.

- Savva, M., & Stanfield, D. (2018). International-mindedness: Deviations, incongruities and other challenges facing the concept. Journal of Research in International Education, 17(2), 179–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240918793954

- Schmithorst, V. J., & Yuan, W. (2010). White matter development during adolescence as shown by diffusion MRI. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 16–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.06.005

- Segalowitz, S. J., Santesso, D. L., & Jetha, M. K. (2010). Electrophysiological changes during adolescence: A review. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 86–100. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.003

- Singh, M., & Qi, J. (2013). 21st century international-mindedness: An exploratory study of its conceptualization and assessment. International Baccalaureate Organization.

- Skelton, M. (2015). International-mindedness and the brain: The difficulties of ‘becoming. In M. Hayden, J. Levy, & J. Thompson (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of research in international education (2nd ed., pp. 379–389). Sage.

- Sriprakash, A., Singh, M., & Qi, J. (2014). A comparative study of international-mindedness in the Diploma Programme in Australia, China and India. International Baccalaureate Organization.

- Steinberg, L. (2010). Commentary: A behavioral scientist looks at the science of adolescent brain development. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.11.003

- Tamatea, L. (2008). A practical and reflexive liberal-humanist approach to international mindedness in international schools: Case studies from Malaysia and Brunei. Journal of Research in International Education, 7(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240907086888

- Tian, M., & Lowe, J. A. (2014). Intercultural identity and intercultural experiences of American students in China. Journal of Studies in International Education, 18(3), 281–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315313496582

- Ting-Toomey, S. (2005). Identity negotiation theory: Crossing cultural boundaries In W. B. Gudykunst, ed., Theorizing about Intercultural Communication, 211–233.

- Umaña-Taylor, A. J., & Updegraff, K. A. (2007). Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 30(4), 549–567. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002

- Wahlstrom, D., White, T., Collins, P. F., & Luciana, M. (2010). Developmental changes in dopamine neurotransmission in adolescence: Behavioral implications and issues in assessment. Brain and Cognition, 72(1), 146–159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2009.10.013

- Wasner, V. (2016). Critical service learning: A participatory pedagogical approach to global citizenship and international mindedness. Journal of Research in International Education, 15(3), 238–252. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240916669026

- Wigfield, A., Lutz, S. L., & Wagner, A. L. (2005a). What every middle school teacher should know. Heinemann.

- Wigfield, A., Lutz, S. L., & Wagner, A. L. (2005b). Early adolescents’ development across the middle school years: Implications for school counselors. Professional School Counseling, 9(2), 112–119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5330/prsc.9.2.2484n0j255vpm302

- Wright, K., & Buchanan, E. (2017). Education for international mindedness: Life history reflections on schooling and the shaping of a cosmopolitan outlook. Current Issues in Comparative Education, 20(1), 68–83.

Appendix A

Students’ Survey on International Mindedness

Demographics

Age

Gender

Ethnic background (list with clickable choices)

Years in IB programmes

Programme(s) attended (DP, IBCP, MYP, PYP)

Type of school (Public/charter/independent/private/primary/elementary/middle/secondary/high school/ through school (3–18 years)

Country of current residence

International Mindedness

How would you define international mindedness? (300-word box)

On the scale from 1 to 10, where 1 means not being internationally minded at all and 10 means being completely internationally minded, how internationally minded are you? (Tick one box)

Please describe a situation when you demonstrated your international mindedness as a student? (500-word box)

What contributed to you becoming internationally minded? (Rate each one from 0 (no influence) to 10 (highly significant influence)

• Family background (origin)

• Parents’ jobs

• Your personal life experiences

• Your study-related experiences

• School events (box to name them)

• International friends

• Community activities (box to name them)

• Travel

• Learning a second language

• Studying

• Other, please specify

12. How did your own family background and life experiences influence the development of your IM? (300-word box)

13. How did your educational experiences influence the development of your IM? (300-word box)

14. What would you think teachers should do to help students develop IM? (300-word box)

15. What would you recommend schools should do to develop IM in their students? (300-word box)