ABSTRACT

The baffling growth in the number of participants in sport events calls for an explanation. Sport event organizers, working on an increasingly competitive market, need to know what factors are important to satisfy the participants and enhance their well-being. Satisfaction is a central concept in consumer behaviour research together with experiences. Subjective well-being (SWB), also referred to as happiness, has made a more recent entry into consumer behaviour research but is gradually gaining recognition as an important concept. The objective of this study is to find out how SWB fits into the framework of consumer behaviour and whether SWB can be explained by satisfaction with the event experience in the context of participatory sport events. It is proposed that satisfaction is better aligned with theories about happiness by distinguishing between hedonic satisfaction and eudaimonic satisfaction. A survey of 7552 participants at five sport events was used to select a subsample of 192 participants, which provides data for testing an SEM model. The model consists of six constructs: Service quality, fun, flow (as components of the event experience), hedonic satisfaction, eudaimonic satisfaction and the dependent construct SWB. The results reveal a good fit of the model. Service quality and fun affect hedonic satisfaction whereas eudaimonic satisfaction is influenced by flow. SWB is explained by hedonic satisfaction, which acts as a fully mediating variable for eudaimonic satisfaction. The conclusions centre on the introduction of two new types of satisfaction consistent with the two facets of happiness and implications for event management.

Introduction

The tremendous growth of demanding participation sport events creates a curiosity to understand and explain the phenomenon. This study starts from the assumption that the event experience makes participants happy and increases their subjective well-being (e.g. Kuykendall, Tay, & Ng, Citation2015). The curiosity is therefore transformed into: ‘What aspects of a sport event experience influence participants’ happiness?’ An answer to this research question is also useful to advice organizers of participatory sport events how to best satisfy their customers and enhance their well-being.

Consumer behaviour research provides a framework for addressing both these challenges. The development of consumer behaviour research in a service context can during the latest five decades be followed through a sequential series of focal areas. Satisfaction (Oliver, Citation1980) was followed by a focus on Service Quality (Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, Citation1985) in its turn followed by a focus on the Experience factor (e.g. O'Sullivan and Spangler, Citation1998). Presently Happiness, or Subjective Well – Being (SWB), is a concept in focus for efforts in consumer behaviour research although still mainly by tapping knowledge from psychological research.

Philosophers in Ancient Greece regarded happiness as a central issue and based discourses on happiness as the ultimate goal of human life. Today, research often refers to the concept Subjective Well-Being (SWB) emanating from Positive Psychology in the 1970s (Diener, Citation1984). SWB is assumed to indicate happiness of the respondent or rather perceived happiness i.e. Subjective Well-Being. The concept is based on a subjective assessment and on the ontological point of view that a ‘definition’ of happiness must rest entirely with the respondent. The dominating empirical approach is to measure SWB by answers to the question ‘Taking all things together, how happy would you say you are?’ measured on a scale from 0 to 10 and to use this measure as the major outcome variable. Since it is assumed that this measure of SWB is of extreme importance to the respondent and that achieving happiness is one of the ultimate goals of life, social research ought to focus on finding factors that influence SWB and make people happy or unhappy.

Recent research has investigated the relationship between leisure engagement, the amount of time individuals participate in leisure activities and subjective happiness (Kuykendall et al., Citation2015). The results indicate that positive experiences are important (Sato, Jordan, & Funk, Citation2014). A study on more than 11,000 individuals showed that leisure engagement and SWB are associated (Kuykendall et al., Citation2015), which suggests that leisure is potentially important for enhancing SWB. Richards (Citation2014) noted that research about events and SWB mainly has been pursued within a cultural event context and that more research is needed in a sport event context and thus one objective with this paper is to contribute to closing this gap.

The objective of this study is to describe and discuss the impact that consumer behaviour concepts have on an explanation of the happiness of participants in sport events.

Literature

Happiness

Lyubomirsky, Sheldon, and Schkade (Citation2005) investigate factors that positively influence the SWB and in a paper entitled ‘Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change’ they suggest three categories of factors. First, they argue that happiness largely – around 50% – is part of our personality and inherent in our genes, which determines the set point describing a long-term stability in happiness, which cannot be influenced. Other dominant factors that determine happiness and SWB in a long-term perspective are called circumstantial factors including demographic factors such as the nation where you live, ethnicity, gender, and age. Personal history is also part of circumstantial factors in terms of, e.g. marital status, health, occupational status, childhood traumas and religion (for a review, see Diener, Suh, Lucas, and Smith, Citation1999). It has been suggested that circumstantial factors account for another tenth of the explanation of personal happiness. Finally, the third category of factors influencing SWB is called intentional activity factors, which thus may explain the remaining approximate 40% of the variation in happiness (Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005). This is the category most relevant for this study and includes both behavioural activity, such as relaxing on a beach or exercising regularly, cognitive activity, such as listening to your favourite music or recognizing with pride that you are in a good physical shape, and volitional activity, such as striving to achieve goals.

One may find the two examples above of behavioural activities contradicting (i.e. relaxing on a beach versus exercising regularly). The examples illustrate two competing perspectives among Greek philosophers. Aristippus (fourth century BC) claimed that pleasurable experiences and avoidance of pain are the sources of happiness. This is today referred to as hedonic happiness and has been related to ‘positive affect’ (Diener, Citation1984; Lyubomirsky, Citation2001) with a positive influence on SWB. The frequency of ‘positive affect’ seems to have more impact than the intensity of positive affect (Diener et al., Citation1999). Absence of ‘negative affect’ also increases SWB thus supporting the hedonic view of happiness formation.

Aristoteles challenged Aristippus already during the fourth century BC and regarded a hedonic life-style to be vulgar. He argued that happiness is to be found in virtue, development and self-realization. Fromm (Citation1980), in a similar vein of thought, contrasted momentary pleasure (hedonism) against realizing needs that are conducive to human growth and producing well-being and happiness. This view of happiness is today known as eudaimonic happiness.

The hedonic and the eudaimonic views of happiness can be regarded as two facets of happiness. Both views have also been supported by empirical evidence. Waterman, Schwartz, and Conti (Citation2008) provide convincing empirical evidence that the two conceptions are interdependent. They further suggest that when an individual is experiencing success in realizing personal potentials, this will give rise to both eudaimonic and hedonic happiness.

Lately, research on consumer behaviour has started to focus on the effect of experiences on happiness. Empirical studies support the notion that purchases can explain happiness (Nicolao, Irwin, & Goodman, Citation2009; Van Boven, Citation2005; Van Boven & Gilovich, Citation2003). Desmeules (Citation2002) states that consumer happiness ‘represents pleasures individuals draw from exchanging their money for goods and services’ (p. 4). In leisure studies, active sport participation is described to evoke emotional reactions relating to a meaningful life with effects on happiness (Bailey & Fernando, Citation2012; Brown, Frankel, & Fennell, Citation1991; DeLeire & Kalil, Citation2010).

Satisfaction of needs

Satisfaction may be conceptualized as a post-purchase evaluation describing how much a consumer likes or dislikes a product after having experienced it (Woodside, Frey, & Daly, Citation1989). Similarly, Swan and Combs (Citation1976) conceptualize satisfaction a post-purchase attitude, which is determined by cognitive and affective aspects of the service encounter (Bagozzi, Gopinath, & Nyer, Citation1999; Giese & Cote, Citation2000; Oliver, Rust, & Varki, Citation1997). Plutchik (Citation1980) emphasized the role of emotions (joy, acceptance, fear, surprise, sadness, disgust, anger, and anticipation) as predictors of satisfaction. Consumer satisfaction may, therefore, refer to the cognitive–affective state resulting from experiences. Satisfaction is likely to determine the extent to which the experience contributes to happiness and satisfaction of event experiences influence a person’s subjective well-being (Sirgy & Samli, Citation1995).

In this study satisfaction with participatory sport events will be defined based on Theodorakis, Kaplanidou, and Karabaxoglou (Citation2015) as ‘The pleasurable fulfilment of needs in response to participation in, as well as services provided at, the sport event.’

This definition is based on the fulfilment of personal needs which have been further elaborated in classical studies of personality (Maslow, Citation1943; Murray, Citation1938). Personal basic and psychological needs such as food, rest, social company and social status have been referred to as deficiency needs implying that fulfilment produces much satisfaction when the needs have been unmet for a long period. On the contrary, when deficiency needs are satisfied, more experiences of this type will not have much effect on satisfaction.

Growth needs, in contrast, are related to a desire to grow and achieve. The satisfaction of growth needs might be defined as the degree to which experiences meet personal growth needs. Growth needs are similar to the concept n(Ach) – the need for achievement – which, some decades ago, played an important role in the studies of personality (e.g. McClelland, Citation1967). Contrary to deficiency needs, growth needs do not decrease when personal goals are met. New and more challenging goals will be formulated as soon as previous achievement goals are met.

Hedonic satisfaction and eudaimonic satisfaction

Based on the distinction between two facets of happiness (e.g. Hedonism and Eudaimonia), we propose two types of satisfaction with the activity performed i.e. hedonic satisfaction and eudaimonic satisfaction. This study consequently posits that hedonic satisfaction is based on positive affect that accompanies participation as well as a feeling of having the resources and opportunities that the individual requires (Kraut, Citation1979) in order to fulfil basic and psychological needs. We, therefore, define hedonic satisfaction as the pleasurable fulfilment of ‘deficiency’ needs in response to the participation in the sport event and the consumption of services provided during the event.

Eudaimonic satisfaction is based on the individual’s satisfaction from developing his/her potentials and moving towards self-realization (Waterman, Citation1993). We define eudaimonic satisfaction as the fulfilment of ‘growth’ needs in response to the participation in the sport event and the consumption of services provided during the event.

While representing different facets, empirical studies have clearly shown that the two types of happiness are interrelated and that they form parts of SWB (e.g. Waterman et al., Citation2008). Philosophers have suggested Eudaimonia as sufficient, but not necessary, for hedonic happiness (Telfer, Citation1980). From this perspective, activities generating Eudaimonia but no hedonic happiness, is a null set, i.e. not theoretically possible (Waterman et al., Citation2008). We thus propose that there is a positive effect from eudaimonic satisfaction on hedonic satisfaction and that hedonic satisfaction is fully mediating the effect of eudaimonic satisfaction on SWB.

H1: There is positive effect from eudaimonic satisfaction on hedonic satisfaction

H2: There is a positive effect from hedonic satisfaction on SWB (happiness)

The event experience

Bitner (Citation1990) describes experiences as ‘servicescapes’ which trigger specific cognitive, emotional, and physiological aspects. In a similar vein, Morgan (Citation2008) refers to event experiences as ‘a space and time away from everyday life in which intense extraordinary experiences can be created and shared’ (Morgan, Citation2008, p. 81). Event experiences are thus different from mundane and everyday life experiences as they are out-of-the-ordinary and are characterized by liminality, communitas, and sacredness (Tumbat & Belk, Citation2013).

Event experiences can be defined by varying levels of cognitive, conative, and affective aspects. O'Sullivan and Spangler (Citation1998) describe experiences as having different levels of physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual activity. Christou, Sharpley, and Farmaki (Citation2018) and Wood and Kenyon (Citation2018) identified a link between emotions and satisfaction. Lazarus (Citation1991) supports these findings by concluding that positive emotional experiences increase the likeliness that people perceive their lives as positive and desirable.

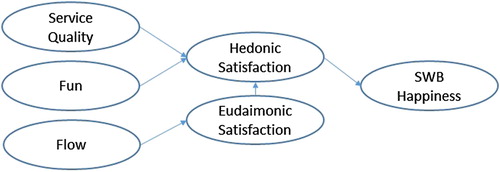

De Geus, Richards, and Toepoel (Citation2016) developed a four-dimensional scale to comprehend event experiences, which may be used to predict satisfaction. The scale was developed in a cultural event context and comprised of affective engagement, cognitive engagement, physical engagement and experiencing novelty. The first three dimensions are generic to experiences, whereas novelty relates specifically to event experiences (De Geus et al., Citation2016). Armbrecht (Citation2019) developed a scale for event quality, based on existing validated scales. The scale was developed in a sport event context and integrates both the quality of experiences and service quality. Starting with six dimensions (service quality, immersion, surprise/novelty, participation, fun, interaction/social and hedonism) four dimensions turned out to be reliable measures of the quality of event experiences. These were: service quality, immersion, fun and hedonism. In this study of sport event participants, the focus will be on three dimensions of the event experience: service quality, fun and flow (immersion). The hedonic dimension is dropped because hedonic satisfaction will be hypothesized as an effect of the event experience ().

Service Quality: Service quality (SQ) is a main aspect when assessing the quality of services (Oh & Kim, Citation2017). The concept was developed in line with the expectancy-disconfirmation theory (Parasuraman et al., Citation1985) and constitutes an evaluation method of consumers’ experience of a service (Theodorakis et al., Citation2015) including a number of service attributes (Brady, Cronin, & Brand, Citation2002; Parasuraman, Zeithaml, & Berry, Citation1988). Service quality consists of five dimensions: tangibles (appearance of physical facilities, equipment, personnel, etc.), reliability (performing the promised service dependably and accurately), responsiveness (willingness to help customers and provide prompt service), assurance (knowledge and courtesy of employees and their ability to convey trust and confidence), and empathy (caring, individualized attention the firm provides its customers) (Parasuraman et al., Citation1988). Service quality constitutes an evaluation of the superiority or inferiority of a service and numerous applications of service-quality scales exist (e.g. Kelley & Turley, Citation2001; Theodorakis et al., Citation2015; Tkaczynski & Stokes, Citation2010; Westerbeek & Shilbury, Citation2003). The relationship between service quality and satisfaction has been extensively researched and has been established (Cole & Illum, Citation2006; Lee & Beeler, Citation2006; Murray & Howat, Citation2002). Cronin and Taylor (Citation1992) offer theoretical justification and empirical proof supporting service quality being a predictor of satisfaction. The framework suggests that higher service quality leads to higher satisfaction. The quality–satisfaction ordering is also supported for events and festivals (Baker & Crompton, Citation2000). Service quality is suggested as an explanatory factor behind hedonic satisfaction.

H3: There is a positive effect from service quality on hedonic satisfaction

Fun: Chen and Chen (Citation2010) propose to conceptualize experience quality based on Otto and Ritchie (Citation1996), encompassing consumers’ affective responses to desired psychological states of mind. Fun refers to the value dimensions proposed by Holbrook (Citation1999) and signifies a dimension of enjoyment during the consumption process. Holbrook (Citation1999) also discusses the play as a supporting component to fun. Deighton and Grayson (Citation1995) conceptualize play as specific rules for consumption, which participants have agreed upon, and which in turn allow for more fun during consumption. Fun, signifying the happiness and enjoyment derived from an experience is suggested as a positive explanatory factor behind hedonic satisfaction.

H4: There is a positive effect from fun on hedonic satisfaction

Flow describes a positive experience, often in relation to physical activities, after completing an activity, which provided a challenge optimally balanced against skills possessed. Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1997) argued that if an activity is too challenging it becomes stressful but if it is too easy, it becomes boring. Flow is also characterized by a high degree of involvement and immersion in the activity performed. A third characteristic of flow is that it makes the activity enjoyable and intrinsically motivating without any need for an external reward.

Flow refers to a state of mind where the individual is fully involved (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation1996). This state of mind leads to consumers forgetting space and time (Pine & Gilmore, Citation1999), resulting in a feeling of detachment and loss of reality. We propose that Flow has a positive influence on eudaimonic satisfaction through involving and immersive activities.

H5: There is a positive effect from Flow on eudaimonic satisfaction

The conceptual model

The concepts and their hypothesized relationships may be visualized in a conceptual model. summarizes and presents the concepts and hypotheses, where hedonic satisfaction, eudaimonic satisfaction and happiness (SWB) of participants in demanding sports events are explained by service quality, fun and flow. Age, sex, nationality, seriousness (of the participant in sporting) and number of past events participated in will be introduced as control variables in the analysis of the structural model.

Methods

The sample

This study is based on a subsample taken from a survey of 7554 participants in five types of sport events representing participants in a road cycling event (Vätternrundan, 30% of the sample); a Half Marathon (Göteborgsvarvet, 25%); a river swim (Vansbrosimmet, 18%); a cross-country run (Lidingöloppet, 17%) and a Nordic ski event (Engelbrektsloppet, 10%). Altogether more than 98,000 amateurs participated in these five events during 2016. The event organizers provided complete lists of e-mail addresses from which random samples of altogether 20,216 participants were generated using SPSS software to represent participants in the events. The surveys were mailed a week after the races and yielded 7554 responses, which is equivalent to an overall response rate of 36%. From this sample of 7554 responses, a subsample of 192 participants (i.e. 2.5%) was sampled randomly using SPSS software. This was done in order to obtain a sample size that is suitable for structural equations modelling (Hair, Black, Babin, & Anderson, Citation2010). describes the numbers, response rates as well as distribution between sports in the large 7554 sample as well as the numbers and distribution between sports in the 192 subsample. The distribution between sports is similar between the large 7554 sample and the small 192 subsample with a slight overrepresentation of Half Marathon and River swim and an underrepresentation of Road cycling in the subsample.

Table 1. Sample sizes and response rates for the survey of five participative sport events.

The missing data analysis indicated that a maximum of 2% missing data exists in the complete list of responses (7554 observations) as well as in the subsample of 192 observations (see Appendix 1). Therefore, no remedies were necessary to improve the quality of the data set.

Constructs and measurements

The constructs; flow (5 items) and fun (5 items) are based on Armbrecht (Citation2019). Service quality was measured using an eight-item scale, based on the previously developed SERVQUAL by Parasuraman et al. (Citation1985) and applied in an event context by Armbrecht (Citation2019). The scale is adapted from Cronin, Brady, and Hult (Citation2000) who studied the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioural intentions. Respondents were asked to state to what extent they agreed with statements measuring each construct. All items were measured on a nine-point scale ranging from (1) ‘strongly agree’ to (9) ‘strongly disagree’. The mid-point (5) was defined as a neutral point (’neither agree nor disagree’). For a complete list of items as well as descriptive statistics on kurtosis and skewness and standard deviations please see Appendix 1.

In the survey, respondents were first introduced to the purpose and aim of the study and at the end of the questionnaire, respondents were asked to answer a number of questions on socioeconomic characteristics including sex, age, number of events participated in during the last 12 months, nationality and seriousness (of the participant in sporting).

Analytical procedure

IBM SPSS Statistics 25 and IBM SPSS Amos 25 Graphics were used during the analysis. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) is performed to assess the reliability and validity of the model as well as its latent and manifest variables (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2006). Structural Equations Modelling is used to assess the causal relationships (Hair et al., Citation2010). The model fit is analysed by means of chi-square statistic (χ2), normed chi-square (χ2/df), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), incremental fit index (IFI), comparative fit index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) (Hair et al., Citation2010; Jaccard, Jaccard, & Wan, Citation1996). Cronbach's alpha is used to assess composite reliability of the latent constructs. Convergent and discriminant validity are assessed as proposed by Kline (Citation2005).

Results

The fit of the measurement model was satisfactory (χ2 = 365; df = 275; CFI = 0.980; RMSEA = 0.042, IFI = 0.980; TLI = 0.975). Overall, the model shows a high degree of validity and reliability in terms of standardized regression weights (above 0.5), variance extracted, and Cronbach’s Alpha, which is above 0.8 for all constructs (see further Appendix 3). A modest refinement of the model was achieved by using standardized residual covariances among some items. The practise of correlating residuals has been debated with arguments both for and against it (Bagozzi, Yi, & Phillips, Citation1991; Fornell, Citation1983; Gerbing & Anderson, Citation1984, Citation1988). If error terms are kept uncorrelated in the present study, this still yields acceptable fit indices: CMIN/DF = 2.045; CFI = 0.935; and RMSEA = 0.074.

Validity and reliability measures are provided in Appendices 2 and 3. Discriminant validity and convergent validity are addressed in Appendix 4 showing that convergent validity is acceptable. AVE exceed 0.5 for all but one construct, SatH, which has an AVE of 0.46 and is regarded borderline but acceptable. In two cases (hedonic satisfaction – fun; hedonic satisfaction – eudaimonic satisfaction), the square of the correlations are higher than the AVE. This is conceptually sound because the correlations represent dependency relationships proposed in the model. The correlational relationships are also in line with the findings by Waterman et al. (Citation2008).

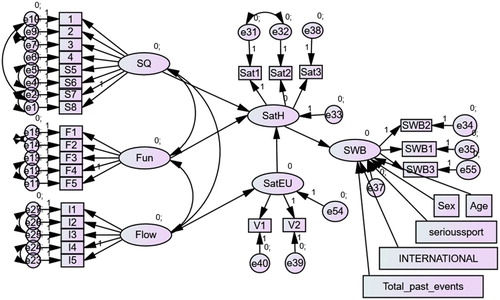

Using IBM SPSS Amos 25 Graphics the hypotheses were tested. In the model, all hypotheses are supported by 1%. The model illustrated in fits the data well with a chi-square of 539 and df = 385 (CFI = 0.967; RMSEA = 0.046, IFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.957).

Figure 2. A structural equations model explaining hedonic satisfaction, eudaimonic satisfaction and subjective well-being. Five control variables are used.

The results () show that fun has a strong positive effect on hedonic satisfaction whereas flow has a strong effect on eudaimonic satisfaction. The standardized regression coefficients ( in the column on the right side) indicate the relative importance of the fun component for hedonic satisfaction, which, in its turn, is a significant predictor of SWB. Flow is strongly affecting eudaimonic satisfaction, which, mediated by hedonic satisfaction positively affects happiness (SWB) and explains 9% of the variance in SWB. Service quality is significant but carries less weight in explaining hedonic satisfaction.

Table 2. Maximum likelihood estimates generated by the structural equations model.

To ascertain that hedonic satisfaction is fully mediating the effect from eudaimonic satisfaction on SWB, the model in was modified by also including a direct effect from eudaimonic satisfaction on SWB, which turned out to be insignificant. The modified model also had a less satisfactory fit and the effect of hedonic satisfaction on SWB was weaker and significant only on 5% level in the modified model. All these differences support the conclusion that hedonic satisfaction is a fully mediating variable for eudaimonic satisfaction on SWB.

None of the five variables controlled for in the structural model were significant on a 1% level. Sex has a significant effect on SWB on a 5% level indicating, that females have higher SWB than men. A table with regression coefficients and significance levels is attached in Appendix 5.

Discussion

This study has addressed the research question: ‘What aspects of a sport event experience influence participants’ happiness?’ with the objective to describe and discuss the impact that consumer behaviour concepts have on explaining the happiness of participants in sport events.

Happiness has been operationalized by the concept of Subjective Well-Being (SWB) and particular emphasis has been given to the consumer behaviour concept satisfaction to explain SWB. Based on a long tradition of happiness research and the school of ‘Positive Psychology’ (Diener, Citation1984; Lyubomirsky, Citation2001), Hedonism and Eudaimonia are discussed as two facets of happiness.

It is proposed in this article that satisfaction meaningfully can be analysed in terms of two interdependent subconstructs: hedonic satisfaction and eudaimonic satisfaction. A model including these constructs is proposed and successfully tested against data from participants in sport events.

Hedonic satisfaction and eudaimonic satisfaction are strongly correlated which underlines that the two facets of happiness – hedonic and eudaimonic happiness – are related to each other and are both part of SWB experiences (e.g. Tomer, Citation2011).

Happiness is assumed to be a stable characteristic of the personality (Diener et al., Citation1999; Lykken & Tellegen, Citation1996; Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005). There is convincing empirical evidence that only a minor part can be impacted by intentional activity factors (Lyubomirsky, Citation2001; Lyubomirsky et al., Citation2005). Taking this into consideration, the model tested in this study is able to give a good explanation of important factors for sport event participants striving to become happier. Having fun has a strong positive effect on hedonic satisfaction as expected and ‘flow ‘, also as expected, strongly influences eudaimonic satisfaction. The standardized regression coefficients () indicate that fun has a stronger impact on hedonic satisfaction than service quality has. Service quality is significant but carries less weight in explaining hedonic satisfaction which may be related to the fact that most aspects of service quality are ‘hygiene factors’ which are expected from a well-organized event and only have an effect (a negative) on hedonic satisfaction if they are not present.

The importance of eudaimonic satisfaction for SWB is channelled via hedonic satisfaction (i.e. hedonic satisfaction is a fully mediating factor). This supports the philosophical notion that Eudaimonia is sufficient, but not necessary, for hedonic happiness (Telfer, Citation1980; Waterman et al., Citation2008). Philosophers and psychologists have also expressed this as activities generating Eudaimonia but no hedonic happiness is a null set, i.e. not theoretically possible (Waterman et al., Citation2008). Thus, activities that induce eudaimonic happiness will also induce hedonic happiness and, there are no activities that induce only eudaimonic happiness and not hedonic happiness.

These results also suggest the existence of a hierarchy whereby hedonic satisfaction is on a higher hierarchical level and embraces eudaimonic satisfaction. For some (e.g. achievement-oriented academics) this conclusion may seem counterintuitive which may be related to moral prejudices and a Lutheran leaning towards Aristoteles rather than towards Hedonism, but the results of this study are clear; even more so considering that the sample used for testing the model consists of sport event participants where one would expect the need for Eudaimonia to be stronger than the need for Hedonism.

We suggest that an explanation could be that sport event participants having attained personal goals and eudaimonic satisfaction will gain self-respect as well as respect from others. This will result in an increase in social status and thus hedonic satisfaction.

This view also has implications for strategies to increase happiness since hedonic satisfaction to a certain extent is bounded (too much food will give us an aching stomach and too much rest will make us bored). Eudaimonic satisfaction will thus introduce an unlimited opportunity to increase happiness by personal development, which, via self-respect and social status, also will have a positive effect on hedonic satisfaction as well as happiness and subjective well-being.

Conceptions of Hedonism and Eudaimonia have been discussed in different areas of economic theory. Some researchers propose that hedonic happiness is related to utilitarian, material, and tangible aspects of experiences (e.g. Tomer, Citation2011). We have proposed that hedonic satisfaction reflects the pleasurable fulfilment of deficiency needs including basic needs and thus utilitarian aspects relating ‘to usefulness, value, and wiseness of the behaviour as perceived by the consumer’ (Ahtola, Citation1985, p. 8). Hedonic satisfaction may however also be related to aesthetic and emotional feelings proposed by Holbrook and Hirschman (Citation1982).

The results of this study may have implications for marketing theory by adding ‘eudaimonic consumption’ - a concept currently evolving (e.g. Delmar, Sánchez-Martín, & Velázquez, Citation2018; Oliver & Raney, Citation2014) as a third concept beside the already existing concepts ‘utilitarian consumption’ and ‘hedonistic consumption’. The dimension of ‘eudaimonic consumption’ describes how growth needs, such as achievement and the realization of personal potentials, can be fulfilled by consumption. We suggest that this dimension applies to consumption of services, particularly experience consumption, but also to consumption of goods as for example when an amateur musician invests a large amount of money in the purchase of a new high-quality musical instrument with the objective to realize hisFootnote1 musical potential.

Reflecting upon happiness research, one must critically discuss whether it is feasible and legitimate to describe what makes people happy. This may be more important when a statistical approach is used in this study. The fact that the European Union, as well as many nations, are collecting large amounts of data in this area, and using it as arguments in political discussions, increases the risk of negative consequences if methods are flawed.

In this study, the subjectivity of the concept happiness (SWB) is a fundamental ontological position. By this, we mean that happiness cannot be academically defined but must be defined subjectively by the respondent. There is no shortage of more elaborate, academically defined, multidimensional conceptualizations but as the number of dimensions increases, the pure subjective feeling of being more or less happy becomes blurred. When elaborate measurement scales are used, there will be an unavoidable introduction of assumed causes and effects of happiness. When assumed causes and effects of happiness are part of the definition and measurement of happiness, a strong bias will of course be introduced as well as a confusing mix of objectivity and subjectivity.

Conclusions

Within the framework of consumer behaviour research, this study has addressed the challenge of explaining how the event experience affects the subjective well-being of sport event participants. The concept ‘satisfaction’ is central in consumer behaviour research and has been elaborated into hedonic satisfaction and eudaimonic satisfaction in this study, in order to be better aligned with two facets of happiness much discussed in the school of positive psychology.

The dichotomy between Hedonism (a life with as much pleasure and as little effort as possible) and Eudaimonia (a life where you grow and develop your potential) has been a theme throughout history in philosophy, moral discourses and it still is in recent happiness research. However, empirical evidence (e.g. Waterman et al., Citation2008) rejects the view of a dichotomy and shows how these two facets of happiness are interrelated. The results of this study support the interdependence between hedonic and eudaimonic satisfaction. Both concepts contribute significantly to an explanation of happiness among sport event participants.

Theoretical implications

A major thrust of this study is the introduction of the two types of satisfaction and findings that hint at a hierarchical order between Hedonism and Eudaimonia whereby Eudaimonia is subordinate. In the model, eudaimonic satisfaction influences happiness (SWB) only through hedonic satisfaction which supports a philosophical statement that Eudaimonia is sufficient, but not necessary for hedonic happiness (Telfer, Citation1980), a statement which previously also has been elaborated empirically by Waterman et al. (Citation2008).

Managerial implications

The principal managerial contribution of this study is to demonstrate that assessing experiential outcomes solely in terms of satisfaction (unidimensional) is imprecise. The results highlight that managers need to consider that both eudaimonic and hedonic satisfaction support participants’ pursuit of happiness. Both types of satisfaction affect subjective well-being. Eudaimonic satisfaction is related to a desire to grow and achieve. As implied by ‘growth needs’, eudaimonic satisfaction does not decrease when personal goals are met. New and more challenging goals will be formulated as soon as previous goals are achieved.

Having achieved personal goals and eudaimonic satisfaction, individuals seek social contexts where they receive feedback on their achievements, which renders hedonic satisfaction. Hedonic satisfaction might thus be defined as the degree to which experiences meet personal basic and psychological needs such as food, social company and social status.

Hedonic satisfaction is bounded (excessive training and running are negative for the body as is too much food and too much sleep). These needs are also referred to as deficiency needs implying that hedonic satisfaction from fulfilment of needs increases when the needs have been unmet for a long period. However once needs are fulfilled, more experiences of this type will not have much effect on hedonic satisfaction. Social contexts present arenas where achievements are recognized by others, resulting in increased image and status leading to hedonic satisfaction. This suggests that event managers should work actively with social networks, social media and support the establishment of social worlds.

The model demonstrated positive effects of service quality and fun on hedonic satisfaction. Fun is the strongest factor to explain hedonic satisfaction, which, in its turn, has a significant positive impact on the happiness of the participants. From a managerial point of view, fun must therefore not be underestimated as a factor to enhance the well-being of participants. Eudaimonic satisfaction was, contrary to expectations, less important. This indicates that managers of participant sport events may gain advantages by somewhat repositioning the event design as well as the marketing communication from ‘achievement’ towards ‘enjoyment’.

Limitations and further research

Validated measures of the new concepts hedonic and eudaimonic satisfaction are missing. In this study, hedonic and eudaimonic satisfaction were measured by three and two items respectively. This is not ideal from a measurement perspective (Hair et al., Citation2010) and is a limitation of this study although the composite reliability of each of the factors was good (Cronbach’s alpha above 0.85). Future research should tell whether the concepts of hedonic satisfaction and eudaimonic satisfaction are fruitful contributions to consumer behaviour research. More studies are needed to assess their usefulness. Studies aiming at the development of validated scales for the two concepts would improve measurements and facilitate comparisons between future empirical studies.

The effects of three experiential factors were tested and found to have significant effects on satisfaction in this study. However, consumer behaviour research describes other aspects of experiences, which may carry relevance in understanding satisfaction. Aspects such as social and cultural factors and safety, destination image and event image are likely to affect the relationships between the experience and satisfaction. These should be considered and analysed in more detail, especially from a managerial point of view.

Future research might study eudaimonic and hedonic satisfaction in event participation and other leisure contexts. Marketing studies analysing utilitarian consumption of products and services together with hedonic consumption and eudaimonic consumption of products and services could reveal how the concepts are related to each other and how they affect SWB.

Acknowledgments

Both authors have contributed equally in writing this article. Many thanks to Dr Erik Lundberg for his assistance in data collection.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In a previous version, one of the authors (quite hypocritically) wrote ‘her musical potential’ but later found out that Leon Armbrecht (the son of the other author) was considering purchasing a new piano that very day. Quite a fine coincidence! Therefore it now stands as ‘his musical potential’ to honour Leon and wish him all success.

References

- Ahtola, O. T. (1985). Hedonic and utilitarian aspects of consumer behavior: An attitudinal perspective. ACR North American Advances 12, 7–10.

- Armbrecht, J. (2019). An event quality scale for participatory running events. Event Management. doi: 10.3727/152599518X15403853721358

- Bagozzi, R. P., Gopinath, M., & Nyer, P. U. (1999). The role of emotions in marketing. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 27(2), 184–206. doi: 10.1177/0092070399272005

- Bagozzi, R. P., Yi, Y., & Phillips, L. W. (1991). Assessing construct validity in organizational research. Administrative Science Quarterly 36, 421–458.

- Bailey, A. W., & Fernando, I. K. (2012). Routine and project-based leisure, happiness, and meaning in life. Journal of Leisure Research, 44(2), 139–154.

- Baker, D. A., & Crompton, J. L. (2000). Quality, satisfaction and behavioral intentions. Annals of Tourism Research, 27(3), 785–804. doi: 10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00108-5

- Bitner, M. J. (1990). Evaluating service encounters: The effects of physical surroundings and employee responses. The Journal of Marketing 54, 69–82.

- Brady, M. K., Cronin J. J., Jr, & Brand, R. R. (2002). Performance-only measurement of service quality: A replication and extension. Journal of Business Research, 55(1), 17–31. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(00)00171-5

- Brown, B., Frankel, B., & Fennell, M. (1991). Happiness through leisure: The impact of type of leisure activity, age, gender and leisure satisfaction on psychological well-being. Journal of Applied Recreation Research, 16(4), 368–392.

- Chen, C.-F., & Chen, F.-S. (2010). Experience quality, perceived value, satisfaction and behavioral intentions for heritage tourists. Tourism Management, 31(1), 29–35. doi: 10.1016/j.tourman.2009.02.008

- Christou, P., Sharpley, R., & Farmaki, A. (2018). Exploring the emotional dimension of Visitors’ satisfaction at cultural events. Event Management, 22(2), 255–269. doi: 10.3727/152599518X15173355843389

- Cole, S. T., & Illum, S. F. (2006). Examining the mediating role of festival visitors’ satisfaction in the relationship between service quality and behavioral intentions. Journal of Vacation Marketing, 12(2), 160–173.

- Cronin, J. J., Jr, Brady, M. K., & Hult, G. T. M. (2000). Assessing the effects of quality, value, and customer satisfaction on consumer behavioral intentions in service environments. Journal of Retailing, 76(2), 193–218.

- Cronin, J. J., Jr, & Taylor, S. A. (1992). Measuring service quality: A reexamination and extension. The Journal of Marketing 56, 55–68.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1996). Creativity: Flow and the psychology of discovery and invention. New York, NY: Harper Collins.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1997). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. New York: Basic Books.

- De Geus, S. D., Richards, G., & Toepoel, V. (2016). Conceptualisation and operationalisation of event and festival experiences: Creation of an event experience scale. Scandinavian Journal of Hospitality and Tourism, 16(3), 274–296.

- Deighton, J., & Grayson, K. (1995). Marketing and seduction: Building exchange relationships by managing social consensus. Journal of Consumer Research, 21(4), 660–676.

- DeLeire, T., & Kalil, A. (2010). Does consumption buy happiness? Evidence from the United States. International Review of Economics, 57(2), 163–176.

- Delmar, J. L., Sánchez-Martín, M., & Velázquez, J. A. M. (2018). To be a fan is to be happier: Using the eudaimonic spectator questionnaire to measure eudaimonic motivations in Spanish fans. Journal of Happiness Studies, 19(1), 257–276.

- Desmeules, R. (2002). The impact of variety on consumer happiness: Marketing and the tyranny of freedom. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 12(1), 1–18.

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 542–575.

- Diener, E., Suh, E. M., Lucas, R. E., & Smith, H. L. (1999). Subjective well-being: Three decades of progress. Psychological Bulletin, 125(2), 276–302.

- Fornell, C. (1983). Issues in the application of covariance structure analysis: A comment. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(4), 443–448.

- Fromm, E. (1980). La revolución de la esperanza. Madrid: Fondo de cultura económica.

- Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1984). On the meaning of within-factor correlated measurement errors. Journal of Consumer Research, 11(1), 572–580.

- Gerbing, D. W., & Anderson, J. C. (1988). An updated paradigm for scale development incorporating unidimensionality and its assessment. Journal of Marketing Research 25, 186–192.

- Giese, J. L., & Cote, J. A. (2000). Defining consumer satisfaction. Academy of Marketing Science Review, 1(1), 1–3.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education.

- Holbrook, M. B. (1999). Consumer value: A framework for analysis and research. London: Routledge.

- Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140.

- Jaccard, J., Jaccard, J., & Wan, C. K. (1996). LISREL approaches to interaction effects in multiple regression. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Kelley, S. W., & Turley, L. W. (2001). Consumer perceptions of service quality attributes at sporting events. Journal of Business Research, 54(2), 161–166. doi: 10.1016/S0148-2963(99)00084-3

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Kraut, R. (1979). Two conceptions of happiness. The Philosophical Review, 88(2), 167–197.

- Kuykendall, L., Tay, L., & Ng, V. (2015). Leisure engagement and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 141(2), 364–403.

- Lazarus, R. S. (1991). Progress on a cognitive-motivational-relational theory of emotion. American Psychologist, 46(8), 819–834. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819

- Lee, J., & Beeler, C. (2006). The relationships among quality, satisfaction, and future Intention for first-time and repeat visitors in a festival setting. Event Management, 10(4), 197–208. doi: 10.3727/152599507783948684

- Lykken, D., & Tellegen, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7(3), 186–189.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56(3), 239–249.

- Lyubomirsky, S., Sheldon, K. M., & Schkade, D. (2005). Pursuing happiness: The architecture of sustainable change. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 111–131.

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396.

- McClelland, D. (1967). Achieving society (Vol. 92051). New York, NY: Simon.

- Morgan, M. (2008). What makes a good Festival? Understanding the event experience. Event Management, 12(2), 81–93. doi: 10.3727/152599509787992562

- Murray, D., & Howat, G. (2002). The relationships among service quality, value, satisfaction, and future intentions of customers at an Australian sports and leisure centre. Sport Management Review, 5(1), 25–43.

- Murray, H. A. (1938). Explorations in personality: A clinical and experimental study of fifty men of college age New York: Oxford University Press.

- Nicolao, L., Irwin, J. R., & Goodman, J. K. (2009). Happiness for sale: Do experiential purchases make consumers happier than material purchases? Journal of Consumer Research, 36(2), 188–198.

- Oh, H., & Kim, K. (2017). Customer satisfaction, service quality, and customer value: Years 2000-2015. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 29(1), 2–29.

- Oliver, M. B., & Raney, A. A. (2014). An introduction to the special issue: Expanding the boundaries of entertainment research. Journal of Communication, 64(3), 361–368.

- Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decisions. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460–469.

- Oliver, R. L., Rust, R. T., & Varki, S. (1997). Customer delight: Foundations, findings, and managerial insight. Journal of Retailing, 73(3), 311–336. doi: 10.1016/s0022-4359(97)90021-x

- O'Sullivan, E. L., & Spangler, K. J. (1998). Experience marketing: Strategies for the new Millennium. State College, PA: Venture Publishing Inc.

- Otto, J. E., & Ritchie, J. B. (1996). The service experience in tourism. Tourism Management, 17(3), 165–174.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1985). A conceptual model of service quality and its implications for future research. Journal of Marketing, 49(4), 41–50.

- Parasuraman, A., Zeithaml, V. A., & Berry, L. L. (1988). SERVQUAL: A multiple-item scale for measuring consumer Perceptions of service quality. Journal of Retailing, 64(1), 12–40.

- Pine, B. J., & Gilmore, J. H. (1999). The experience economy: Work is theatre & every business a stage. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School.

- Plutchik, R. (1980). Emotion, a psychoevolutionary synthesis. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Richards, G. (2014). Eventfulness and the quality of life. Tourism Today, 14(Fall), 23–36.

- Sato, M., Jordan, J. S., & Funk, D. C. (2014). The role of physically active leisure for enhancing quality of life. Leisure Sciences, 36(3), 293–313.

- Sirgy, M. J., & Samli, A. C. (1995). New dimensions in marketing/quality-of-life research. London: Quorum Books

- Swan, J. E., & Combs, L. J. (1976). Product performance and consumer satisfaction: A new concept. An empirical study examines the influence of physical and psychological dimensions of product performance on consumer satisfaction. Journal of Marketing, 40(2), 25–33.

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2006). Using multivariate statistics. Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

- Telfer, E. (1980). Happiness: An examination of a hedonistic and a eudaemonistic concept of happiness and of the relations between them. London: Macmillan.

- Theodorakis, N. D., Kaplanidou, K., & Karabaxoglou, I. (2015). Effect of event service quality and satisfaction on happiness among runners of a recurring sport event. Leisure Sciences, 37(1), 87–107.

- Tkaczynski, A., & Stokes, R. (2010). FESTPERF: A service quality measurement scale for festivals. Event Management, 14(1), 69–82.

- Tomer, J. F. (2011). Enduring happiness: Integrating the hedonic and eudaimonic approaches. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 40(5), 530–537. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2011.04.003

- Tumbat, G., & Belk, R. W. (2013). Co-construction and performancescapes. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 12(1), 49–59.

- Van Boven, L. (2005). Experientialism, materialism, and the pursuit of happiness. Review of General Psychology, 9(2), 132–142.

- Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2003). To do or to have? That is the question. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(6), 1193–1202.

- Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64(4), 678–691.

- Waterman, A. S., Schwartz, S. J., & Conti, R. (2008). The implications of two conceptions of happiness (hedonic enjoyment and eudaimonia) for the understanding of intrinsic motivation. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(1), 41–79.

- Westerbeek, H. M., & Shilbury, D. (2003). A conceptual model for sport services marketing research: Integrating quality, value and satisfaction. International Journal of Sports Marketing and Sponsorship, 5(1), 3–23.

- Wood, E. H., & Kenyon, A. J. (2018). Remembering together: The importance of shared emotional Memory in event experiences. Event Management, 22(2), 163–181. doi: 10.3727/152599518X15173355843325

- Woodside, A. G., Frey, L. L., & Daly, R. T. (1989). Linking sort/ice anlity, customer satisfaction, and behavioral intention. Journal of Health Care Marketing, 9(4), 5–17.