ABSTRACT

The purpose of this paper is to further advance the discussion regarding Local Authorities and approaches to facilitate sustainable planning for tourism. Building on previous research into tourism planning at local level in Ireland, this study employed qualitative semi-structured interviews with every senior planner in Ireland’s 28 Local Authorities to identify the degree to which evidence-informed planning for tourism is encouraged. Findings point to a tendency from senior planners to rely on existing legislative procedures to measure tourism activity. Despite the legal responsibilities Local Authorities have to sustainably plan for tourism, together with substantial advancements in the development of procedures for facilitating evidence-informed planning for tourism. The absence of sufficient monitoring of several key tourism impacts at destination level by this study, questions the ability of senior planners in Ireland to plan sustainably for tourism and protect the tourism product going forward.

Introduction

Planning together with the development of policy can have a significant influence on how tourism develops, and how its benefits and impacts are distributed (Dredge & Jamal, Citation2015; Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2007; Hall & Jenkins, Citation1995; Liasidou, Citation2019; Ruhanen, Citation2010; Shao et al., Citation2020). It was Dwyer and Edwards (Citation2010) who warned that poorly planned tourism can leave permanent footprints on the physical, social, cultural, and economic environments of destinations. Therefore, it is of little surprise that the UNWTO (Citation2004) continues to promote the relationship between sustainability and tourism planning, which, according to Dredge and Jenkins (Citation2011), continues to garner increased attention within academic circles. It is this assessment, and the several studies that continue to emphasise the importance of applying sustainability within the tourism planning process (Bramwell & Lane, Citation2010; Connell et al., Citation2009; Hall, Citation2008; Matiku et al., Citation2020). Yet few have provided insights into approaches practised by Local Authorities when embracing sustainable planning for tourism (Dodds & Butler, Citation2010; Maxim, Citation2013; McLoughlin & Hanrahan, Citation2016, Citation2019). This paper addresses this gap in knowledge by building on previous research in Ireland to determine whether Local Authorities in Ireland are facilitating an evidence-informed approach to tourism planning at destination level.

Planning is about setting and meeting objectives, and in tourism planning is an essential activity to achieve its sustainable development. Ivars (Citation2004), in his analysis on tourism planning in Spain, discussed four broad approaches of tourism planning. For example, the earlier approaches to tourism planning (i.e. boosterism) generally reflect an uncomplicated view of tourism, while strategic planning has moved from the business environment to regional and urban planning in the 1980s (Ivars, Citation2004). Hall (Citation2008) considers that the focus and methods of tourism planning have not remained constant but have evolved to meet the new demands that have been placed on the tourism industry. This assertation is also reflected by Costa (Citation2019) who emphasises that future planning at destination level should address issues around embodying not only management approaches, but also planning considerations and local economic concerns. McLoughlin et al. (Citation2018, p. 87), in fact, suggests that evidence-informed planning for tourism is the way forward to help ensure the future sustainability of tourism. However, considering that the application of tourism indicator systems, as noted by McLoughlin and Hanrahan (Citation2019), suffers from a lack of enthusiasm among Local Authorities, despite their legal responsibility for managing and developing tourism at the destination level throughout Ireland. It is against this background, that this study will examine whether senior planners in each of Irelands Local Authorities are measuring and monitoring tourism activity through specific measures to facilitate an evidence-informed approach to tourism planning.

Literature review

Planning is an essential element of successful tourism development and management (Hall, Citation2005, Citation2007). According to Sharpley (Citation2008), effective planning should ensure that

Tourism is developed according to broader economic and social development goals that it is developed sustainably, and that appropriate mechanisms and processes are in place to ensure that tourism development is managed, promoted and monitored. (Citation2008, p. 15)

For Page and Dowling (Citation2002), the need for Local Authority involvement in tourism planning is partly driven by the necessity for the development of tourism policy. This view is similarly shared by Dredge and Jenkins (Citation2007) who note how it is Local Authorities who control most of the development planning aspects associated with tourism. In the context of this study, under the Planning and Development Act (2015), Local Authorities in Ireland are legally required to develop County Development Plans (CDPs). As these plans are the main instrument for the regulation and control of local development, Local Authorities must include planning policies for the development of tourism (DEHLG, Citation2007). However, McLoughlin and Hanrahan (Citation2019) warn that without an evidence-informed approach to tourism planning, policymakers would be unable to anticipate future planning needs. Thus, they potentially damage the future long-term sustainability of the tourism product.

Evidence-informed planning for tourism

Head (Citation2008) discussed how evidence has become central to the design, implementation and evaluation of policies and programmes. From a tourism perspective McCole and Joppe (Citation2014) argue that gathering data on tourist activity is important for not only its future sustainability, but also how the destination is managed. Taking the connection between Local Authorities and tourism planning, recent studies have argued that the absence of data on tourism activity deprives Local Authorities of the opportunity to get ahead of challenges that tourism may present (Maguire & McLoughlin, Citation2019; McLoughlin et al., Citation2018). However, it was Torres-Delgado and Palomeque (Citation2014) who highlight a potential problem here in that there is no universally accepted method for evaluating tourism sustainability. Therefore, by building upon previous research by McLoughlin and Hanrahan (Citation2019), this study will address the concerns raised by Torres-Delgado and Palomeque (Citation2014) and examine what approaches Local Authorities in Ireland are utilising to help facilitate evidence informed planning for tourism. The authors will examine if senior planners are accumulating research on tourism activity, together with the ongoing measuring and monitoring of impacts as part of the tourism planning process.

Measuring impacts

When it comes to measuring the impacts of tourism, Modica et al. (Citation2018) posed the question whether sustainability in tourism can actually be measured at local level. Issues around its complexity have also been noted by Torres-Delgado and Palomeque (Citation2014) which can make it difficult to develop a sound method. Mowforth and Munt (Citation2016) in their discussions on tourism and sustainability did identify tourism indicator systems as one of their tools of sustainability that can be used to measure the impacts of tourism in the planning process. As such, a number of different means have been developed to help facilitate such a transition. Jiricka et al. (Citation2014), for example, discussed the role of the VV-TOMM (Tourism Optimisation Management Model) and its ability to balance visitor numbers and the welfare of the local environment and population. More recently, Torres-Delgado and Palomeque (Citation2018) proposed the ISOST index as a tool for studying sustainable tourism. Also, the European Commission (EC) has long committed itself to promoting the ongoing measurement of tourism impacts across Europe through its development of both Eurostat and the European Tourism Indicator System (ETIS). While the above indicator systems and their on-going development accordingly can help promote more sustainable forms of tourism (Blancas et al., Citation2015), they can also help to stimulate the competitiveness of the sector (Font et al., Citation2021). But despite such advancements in these indicator systems and the on-going work and support of the United Nations (UNWTO) statistics division, McLoughlin and Hanrahan (Citation2019) found little support for such tools by policymakers in Ireland. Therefore, this study will determine if Local Authorities in Ireland are actively measuring impacts as part of the tourism planning process.

Strategic environmental assessments (SEAs) have been identified as a tool to help evaluate the impact of tourism within national parks in Canada (Noble, Citation2003). Furthermore, their use became more widespread following the introduction of the European SEA Directive (2001/42/EC), where Kuo et al. (Citation2005) discuss how they can facilitate early considerations of potential impacts in the strategic decision-making process. Across Europe, Lemos et al. (Citation2012) point to the fact that SEAs have been extensively applied to spatial and land use plans which encompass tourism-related sections. Therefore, it could be argued that SEAs can help alleviate the potential negative impact tourism development may have on the natural environment, while providing policymakers with sound, evidenced, and environmentally sustainable planning policies. However, with the symbolic relationship between tourism arrivals and economic impacts (Mason, Citation2016) destinations have to tackle many social and cultural challenges (McLoughlin et al., Citation2020). Yet, SEAs are limited to measuring the impacts of developments on the environment. They fail to provide an accurate picture when it comes to the wider sustainability of tourism at destination level (McLoughlin, Citation2017). Therefore, it is necessary for this study to determine if senior planners are monitoring the economic and social cultural impacts from tourism in conjunction with SEA assessments at destination level.

Monitoring impacts of tourism

To help guarantee tourism’s long-term sustainability, there is a need for the continued monitoring of its impacts at destination level (Ivars-Baidal et al., Citation2021; Rio & Nunes, Citation2012). As noted by both Cernat and Gourdon (Citation2012) and Mason (Citation2016), studies assessing tourism activities often deal with the relationship between tourism and foreign exchange earnings, generation of income, employment, and regional and local development (Pratt & Alizadeh, Citation2018). With Cooper et al. (Citation2008) arguing that such a relationship is often assessed on the number of arrivals, receipt per tourist, and average length of stay. However, given the challenges, destinations are going to face as a result of COVID-19 pandemic with a report by the Norwegian tourism organization NHO Reiseliv (Citation2020) warning that tourism will be hit particularly hard in comparison to other economic sectors. The UNWTO (Citation2020) has projected a 20–30% decline in 2020 international arrivals, which could potentially translate into losses of tourism receipts in the region of US$300–450 billion. Therefore, it is imperative that policymakers establish how significant tourism is to destination economies to determine its dependency and to develop polices and strategies for the future. Therefore, this study will aim to determine whether Ireland’s Local Authorities are monitoring impacts such as expenditure of tourists, their overall length of stay, together with occupancy rates in commercial accommodation and employment figures. As these data have been considered essential components of any sustainable planning approach to tourism (McLoughlin et al., Citation2020; McLoughlin & Hanrahan, Citation2019; Twining-Ward & Butler, Citation2002; Volo, Citation2015), this on-going monitoring can, therefore, allow policymakers to track the contribution of tourism towards economic sustainability. But, help support local tourism enterprises thorough sharing data on visitor spending patterns.

Increasingly tourism destinations have to tackle many social and cultural challenges (Chettiparamb & Kokkranikal, Citation2012; Kakoudakis & McCabe, Citation2018; Luonila et al., Citation2020; McLoughlin et al., Citation2020). Scholars have pointed to overcrowding in tourist destinations and its relationship with environmental destruction (Mazanec et al., Citation2007; Santana-Jiménez & Hernández, Citation2011). But as discussed by Gössling et al. (Citation2020), within the space of a few months, the global tourism system moved from over-tourism (Dodds & Butler, Citation2019; Seraphin et al., Citation2018) to non-tourism. In light of this changing nature of tourism, it is necessary to continually monitor how tourism is impacting local community. Tourism can be largely dependent on history and culture (Walton, Citation2013), and with three out of five (64%) overseas holidaymaker’s pointing to Ireland’s history and culture as a crucially important factor in their choice to visit (Fáilte Ireland, Citation2013). Kim et al. (Citation2013, p. 538) argues, however, that tourism can be seen as a ‘culture exploiter’. And when reflecting on the connection between tourism and heritage, Sasaki (Citation2004) and Alberti and Giusti (Citation2012) further discuss how regions are building their competitiveness by leveraging their cultural heritage. Regardless of whether tourism has helped accelerate the disruption of traditional cultural structures and behavioural patterns (e.g. Kousis, Citation1989) or has, in fact, contributed to the revitalisation of cultures (e.g. Wang et al., Citation2009), it is imperative that such impacts are the subject of on-going monitoring by policymakers.

Needham and Szuster (Citation2011), in their study on tourism and recreation management strategies in Hawaii, discussed how tourism activity can often have a profound effect on the natural environment. This connection between tourism, its impacts and the environment has been at the centre of several theoretical discussions (e.g. Buckley, Citation2011; Davenport & Davenport, Citation2006; Geneletti & Dawa, Citation2009; Han, Citation2021; Holden, Citation2008; Li et al., Citation2014; Persson, Citation2015). Yet, evidence-informed planning for tourism should not be viewed as a panacea for poor development (McLoughlin & Maguire, Citation2022; Torres-Delgado & Palomeque, Citation2018). Concerns continue to be raised around the impact of transport, waste treatment and energy use (McLoughlin et al., Citation2020). In Ireland and similar destinations across Europe, Local Authorities have a statutory obligation to plan and maintain the natural environment which tourists can put a high value upon. Consequently, with the frequent monitoring of such issues as part of the tourism planning process, policymakers could be in a position to establish many of the root causes of negative environmental impacts from tourism and help protect the natural environment going forward.

Materials and methods

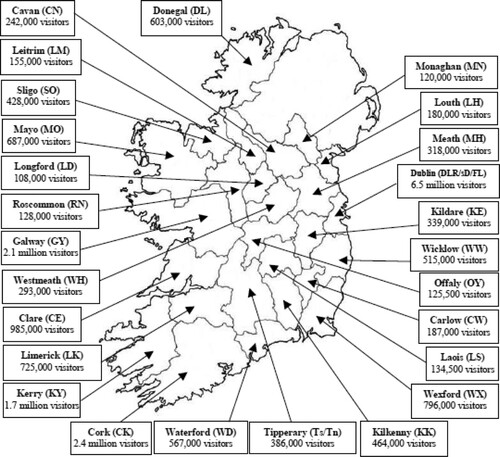

The aim of this study is to access the degree to which Local Authorities are adopting an evidence-informed approach when it comes to tourism planning. This research was conducted in the Republic of Ireland where local government functions in Ireland are exercised by Local Authorities (see ).

Figure 1. Map of Irelands local authorities. Source: Fáilte Ireland (2016). Key: Local authorities are abbreviated by the first and last letter DL = Donegal Number of visitors comprises domestic and international arrivals to the specific County for the year 2016.

Local Authorities were selected for this study as they have the legal power to reject or grant planning permission for all tourism development projects and their associated infrastructure. Local Authorities are also legally obliged to make CDPs which contain the tourism polices for the destination. highlights how the twenty-eight Local Authorities varied on monitoring the different categories. For example, the first and last letter of County Mayo is abbreviated by ‘MO’.

The principle qualitative fieldwork within this study was attained by conducting semi-structured interviews with all senior planners in Ireland’s twenty-eight Local Authorities as qualitative research is suited to situations where there is little known about the topic (Jennings, Citation2010). Moreover, according to Wilson and Hollinshead (Citation2015) qualitative inquiry approaches continue to make significant contributions to tourism studies as they contribute considerable depth to tourism research (Botterill, Citation2001). This was, of course, beneficial for this study as research into evidence-informed planning in Ireland is limited (McLoughlin & Hanrahan, Citation2019). A questionnaire, which comprised open-ended and probing questions, was developed as part of a wider study on tourism planning in Ireland. These questions () were based on the theoretical framework established by McLoughlin and Hanrahan (Citation2019) with the monitoring criteria reflecting the key indicators of the European Tourism Indicator System for Sustainable Destination Management (see Appendix 1).

Table 1. Towards evidence-informed planning for tourism.

The authors determined that senior planners would be in the best position to provide the relevant information on the subject of evidence-informed planning for tourism as they are responsible for developing their respective CDPs. The questionnaire was piloted on one particular senior planner and their tourism development officer. This was done to maintain credibility as advised by Berg (Citation2007). Interviews took place over three months in 2016. All Local Authorities responded to the questionnaires (yielding a response rate of 100%).

Data were analysed by means of audio recordings (with the free and informed consent of the interviewees) and transcribed after each session with the researcher documenting the key issues. A coding scheme was developed in a formal and systematic manner where quotes with similar themes were identified, otherwise known as data transformation (Devine & Devine, Citation2011; Saunders et al., Citation2000). Acknowledging Durbarry’s (Citation2017) ethical principles, all references to a particular Local Authority were removed from planner responses to ensure the anonymity and confidentiality of the respondent. The authors then employed a thematic analysis with the help of the NVivo 10 software package to identify themes and ideas evident from the discussions with senior planners.

Results and discussion

Building on Costa’s (Citation2019) key considerations for future tourism planning, McLoughlin et al. (Citation2020) argue that future planning requires significant levels of information to preserve the environmental, economic, and socio-cultural sustainability of the destination. From the discussions with Ireland’s Local Authorities, it was found that a majority of senior planners conducted rather basic levels of tourism research. Such findings are at odds with what Mangion (Citation2011) suggests as the need for high-quality research when it comes to evidence-based policymaking

Yes, we would conduct a limited amount of tourism research. This would all depend on different things like the scope of the study and so forth. (Planner 20)

Yes, we do. The usual stuff, surveys etc. (Planner 23)

Yes, this research consisted of surveys, questionnaires and case studies. (Planner 10)

The EC (Citation2016) points to the importance of collecting data on a broad range of issues relevant to tourism that could help policymakers build an accurate picture of what is going on. Despite a legal requirement under the Planning and Development (Strategic Environmental Assessment) Regulations 2004, findings from this study seem to corroborate the views previously discussed by Noble (Citation2003) that SEAs remain an extensive tool in the tourism planning process:

Yes, we are legally required to measure environmental impacts through the SEA Directive and the economic and social impacts of tourism were taken into consideration in the LECP development process. (Planner 7)

We would have measured the economic and social impact of tourism when developing our LECP. (Planner 26)

Research by Inskeep (Citation1994) discusses the various categories of data that are required by policymakers when formulating a tourism plan. However, from discussions with senior planners, findings in tend to support McLoughlin and Hanrahan’s (Citation2019) observation that Local Authorities in Ireland tend to rely on limited data when it comes to monitoring tourism in their destination. Furthermore, this study has found a number of senior planners were openly dismissive of such an undertaking as part of the tourism planning process:

No, we don’t monitor specific impacts of tourism. (Planner 14)

We wouldn’t specially monitor the impacts of tourism. (Planner 3)

Table 2. Local authority monitoring of tourism impacts.

Despite what has been considered previously by McCole and Joppe (Citation2014), it is clear from this study is that the vast majority of Local Authorities in Ireland do not benefit from or gathering quality data on tourism activity. The absence of sufficient data has been raised previously by Scott and Becken (Citation2010) when they discussed how the lack of information on climate change, carbon footprint and waste management can impede upon the progress towards greater sustainability in tourism. The authors here suggest that Local Authorities in Ireland could follow the recommendation by Mariani et al. (Citation2018) who approves the usefulness of data sources generated towards business insights and the role such data can play when it comes to tourism planning. Therefore, there is no reason to suggest that policymakers and destination managers could embrace the various sources of big data to help move towards evidence-informed planning for tourism. Such an approach, according to Pan and Yang (Citation2017), has provided a significant amount of real-time data on tourism activity. For example, Xiang (Citation2010) examined online search queries, De Montjoye et al. (Citation2015) discussed the relationship between credit card transaction data, Huertas and Marine-Roig (Citation2016) studied social media information with Hardy et al. (Citation2017) exploring cell phone roaming records.

Rio and Nunes (Citation2012), in their study on monitoring and evaluation tools for tourism destinations, note how many of these monitoring tools are often excessively complex to apply. Similarly, McLoughlin and Hanrahan (Citation2019 also found issues, such as training and resources available as hindrances, when it comes to the application for such tools. Yet, aside from the previously mentioned ETIS, Rio and Nunes (Citation2012) developed and tested a tool in the Ukraine to monitor and evaluate tourism destinations which, according to the authors, was well suited when limited technical and economic resources are available, while several studies have applied the ETIS at destination level and have generated significant data on tourism related activity such as visitation patterns and tourist profiles (Dincă et al., Citation2017), average daily spend of domestic and overseas visitors (McLoughlin et al., Citation2020), local resident satisfaction (Foroni et al., Citation2019) and carbon footprint of travellers (McLoughlin et al., Citation2018). Previous research has found that the use of indicator systems among Local Authorities in Ireland continues to be overlooked (McLoughlin & Hanrahan, Citation2019). Such a lack of adoption is not only depriving policymaker’s quality data on tourism activity, and as previously noted by Blancas et al. (Citation2015) but also helping to stimulate the competitiveness of the sector. But this, together with the limited measuring and monitoring of tourism impacts illustrated by this study, is hindering the move towards evidence-informed planning for tourism at destination level.

Conclusion and recommendations

Tourism as an industry continues to respond to many of the global events that tend to occur outside of its control (Burnett & Johnson, Citation2020). This highlights the need for destinations to move towards an evidence-informed approach to tourism planning. However, despite their responsibilities (Aronsson, Citation2000) and their role in the planning process (Dredge & Jenkins, Citation2007), the low adoption of research by Local Authorities in Ireland on visitation patterns or the on-going measuring and monitoring of tourism impacts has raised questions of their ability to maintain the tourism product. Findings from this research suggest the need for the development of a checklist to help policymakers at local level to monitor tourism’s impact over time. Future research could address the need for such a checklist that could allow for clear accountability and transparency in the data collection process at destination level.

While there is a drive towards the sustainable management of tourism destinations, this study bridges a gap in knowledge by providing baseline findings on the degree to which Local Authorities are incorporating evidence into the tourism planning process. However, this research was conducted at a time when Local Authorities in Ireland are struggling to provide public services due to serious lack of resources. It was, therefore, not surprising to find a lack of enthusiasm among senior planners towards collecting data on tourism activity. In terms of future avenues for research, it would be noteworthy to examine the degree of knowledge among policymakers in Local Authorities on the array of recognised tourism indicators. Such findings could help give a clear indication if evidence-informed planning has become a fundamental characteristic of destination management.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge all the senior planners who devoted their time to participate in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alberti, F. G., & Giusti, J. D. (2012). Cultural heritage, tourism and regional competitiveness: The motor valley cluster. City, Culture and Society, 3(4), 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ccs.2012.11.003

- Aronsson, L. (2000). The development of sustainable tourism. Continuum.

- Ashworth, G. J., & Page, S. J. (2011). Urban tourism research: Recent progress and current paradoxes. Tourism Management, 32(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.02.002

- Berg, B. L. (2007). Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. (6th ed). Pearson Education.

- Blancas, F. J., Lozano-Oyola, M., & González, M. (2015). A European sustainable tourism labels proposal using a composite indicator. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 54, 39–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2015.05.001

- Botterill, D. (2001). The epistemology of a Set of tourism studies. Leisure Studies, 20(3), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614360127084

- Bramwell, B. (2011). Governance, the state and sustainable tourism: A political economy approach. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 19(4-5), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2011.576765

- Bramwell, B., & Lane, B. (2010). Sustainable tourism and the evolving roles of government planning. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580903338790

- Buckley, R. (2011). Tourism and the environment. Annual Review of Environment and Resources, 36(1), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-environ-041210-132637

- Burnett, M., & Johnson, T. (2020). Brexit anticipated economic shock on Ireland’s planning for hospitality and tourism: Resilience, volatility, and exposure. Tourism Review, 75(3), 595–606. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-04-2019-0118

- Can, A. S., Alaeddinoglu, F., & Turker, N. (2014). Local authorities’ participation in the tourism planning process. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 10(41), 190–212.

- Cernat, L., & Gourdon, J. (2012). Paths to success: Benchmarking cross-country Sustainable tourism. Tourism Management, 33(5), 1044–1056. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2011.12.007

- Charlton, C., & Essex, S. (1996). The involvement of district councils in tourism in england and wales. Geoforum, 27(2), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/0016-7185(96)00011-5

- Chettiparamb, A., & Kokkranikal, J. (2012). Responsible tourism and sustainability: The case of kumarakom in kerala, India. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 4(3), 302–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2012.711088

- Connell, J., Page, S., & Bentley, T. (2009). Towards sustainable tourism planning in New Zealand: Monitoring local government planning under the resource management Act. Tourism Management, 30(6), 867–877. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2008.12.001

- Cooper, C., Fletcher, J., Fyall, A., Gilbert, D., & Wanhill, S. (2008). Tourism: Principles and practice (4th ed). Financial Times Prentice Hall.

- Costa, C. (2019). Tourism planning: A perspective paper. Tourism Review, 75(1), 198–202. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-09-2019-0394

- Davenport, J., & Davenport, J. (2006). The impact of tourism and personal leisure transport on coastal environments: A review. Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science, 67(1-2), 280–292. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecss.2005.11.026

- De Montjoye, Y. A., Radaelli, L., & Singh, V. K. (2015). Unique in the shopping mall: On the reidentifiability of credit card metadata. Science, 347(6221), 536–539. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1256297

- Department of Environment Heritage and Local Government (DEHLG). (2007). Development plans: guidelines for planning authorities. DECLG.

- Department of Housing Planning and Local Government (DHPLG). (2017). “Local Government”. http://www.housing.gov.ie/local-government/local-government

- Devine, A., & Devine, F. (2011). Planning and developing tourism within a public sector quagmire: Lessons from and for small countries. Tourism Management, 32(6), 1253–1261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.11.004

- Dincă, G., Foris, D., & Demeter, T. (2017). Identifying brasov county’s touristic visitors’ profile using European tourism indicators system. Journal of Smart Economic Growth, 2(2), 71–81.

- Dodds, R., & Butler, R. (2019). Overtourism: Issues, realities and solutions. De Gruyter.

- Dodds, R., & Butler, R. W. (2010). Barriers to implementing sustainable tourism policy in mass tourism destinations. Tourismos: An International Multidisciplinary Journal of Tourism, 5(1), 35–53.

- Dredge, D. (2001). Local government tourism planning and policymaking in New South Wales: Institutional development and historical legacies. Current Issues in Tourism, 4(24), 355–338. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500108667893

- Dredge, D. (2006). Networks, conflict and collaborative communities. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 14(6), 562–581. https://doi.org/10.2167/jost567.0

- Dredge, D., & Jamal, T. (2015). Progress in tourism planning and policy: A post-structural perspective on knowledge production. Tourism Management, 51, 285–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.06.002

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2007). Tourism planning and policy. John Wiley.

- Dredge, D., & Jenkins, J. (2011). Stories of practice: Tourism policy and planning. Ashgate.

- Durbarry, R. (2017). Research methods for tourism students. Routledge.

- Dwyer, L., & Edwards, D. (2010). Understanding the sustainable development of tourism: Sustainable tourism planning. Goodfellow Publishers.

- European Commission (EC). (2016). European tourism indicator system for the sustainable management of destinations. http://ec.europa.eu/growth/sectors/tourism/offer/sustainable/indicators/index_en.htm

- Fáilte Ireland. (2013). Culture and heritage tourism: An emerging economic engine. Press Releases 25th of April 2013. http://www.failteireland.ie/News-Features/News-Library/Culture-and-heritage-tourism%E2%80%A6an-emerging-economic.aspx

- Font, X., Torres-Delgado, A., Crabolu, G., Palomo Martinez, J., Kantenbacher, J., & Miller, G. (2021). The impact of sustainable tourism indicators on destination competitiveness: The European tourism indicator system. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1910281

- Foroni, I., Modica, P., & Zenga, M. (2019). Residents’ satisfaction with tourism and the European tourism indicator system in South Sardinia. Sustainability, 11(8), 2243. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11082243

- Geneletti, D., & Dawa, D. (2009). Environmental impact assessment of mountain tourism in developing regions: A study in Ladakh, Indian Himalaya. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 29(4), 229–242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2009.01.003

- Gössling, S., Scott, D., & Hall, C. M. (2020). Pandemics, tourism, and global change: A rapid assessment of COVID-19. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(1), 1–20.

- Gunn, C. A. (1988). Tourism planning. Taylor and Francis.

- Hall, C. M. (2005). Tourism: Rethinking the social science of mobility. Prentice.

- Hall, C. M. (2007). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships. Prentice Hall.

- Hall, C. M. (2008). Tourism planning: Policies, processes and relationships (2nd ed). Pearson Education.

- Hall, C. M., & Jenkins, J. M. (1995). Tourism and public policy. Routledge.

- Han, H. (2021). Consumer behaviour and environmental sustainability in tourism and hospitality: A review of theories, concepts, and latest research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 29(7), 1021–1042.

- Hardy, A., Hyslop, S., Booth, K., Robards, B., Aryal, J., Gretzel, U., & Eccleston, R. (2017). Tracking tourists’ travel with smartphone-based GPS technology: A methodological discussion. Information Technology & Tourism, 17(3), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-017-0086-3

- Head, B. W. (2008). Three lenses of evidence-based policy. Australian Journal of Public Administration, 67(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8500.2007.00564.x

- Holden, A. (2008). Environment and tourism. Routledge.

- Huertas, A., & Marine-Roig, E. (2016). User reactions to destination brand contents in social media. Information Technology & Tourism, 15(4), 291–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40558-015-0045-9

- Inskeep, E. (1994). Tourism planning: An integrated and sustainable development approach. Van Nostrand Reinhold.

- Ivars-Baidal, J. A., Vera-Rebollo, J. F., Perles-Ribes, J., Femenia-Serra, F., & Celdrán-Bernabeu, M. A. (2021). Sustainable tourism indicators: What’s new within the smart city/destination approach? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 0, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1876075

- Ivars, J. (2004). Regional tourism planning in Spain: Evolution and perspectives. Annals of Tourism Research, 31(2), 313–333. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2003.12.001

- Jennings, G. (2010). Tourism research (2nd ed). Wiley and Sons.

- Jiricka, A., Salak, B., Arnberger, A., Eder, R., & Pröbstl-Haider, U. (2014). VV-TOMM: Capacity building in remote tourism territories through the first European transnational application of the tourism optimization management model. Sustainable Tourism VI, 187, 93. https://doi.org/10.2495/ST140081

- Kakoudakis, K. I., & McCabe, S. (2018). Social tourism as a modest, yet sustainable, development strategy: Policy recommendations for Greece. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 10(3), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1443938

- Kim, H., Cheng, C. K., & O’Leary, J. T. (2007). Understanding participation patterns and trends in tourism cultural attractions. Tourism Management, 28(5), 1366–1371. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2006.09.023

- Kim, K., Uysal, M., & Sirgy, M. J. (2013). How does tourism in a community impact the quality of life of community residents? Tourism Management, 36, 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2012.09.005

- Kousis, M. (1989). Tourism and the family in a rural cretan community. Annals of Tourism Research, 16(3), 318–332. https://doi.org/10.1016/0160-7383(89)90047-9

- Kuo, N. W., Hsiao, T. Y., & Yu, Y. H. (2005). A delphi–matrix approach to SEA and its application within the tourism sector in Taiwan. The Journal of Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 25(3), 259–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2004.09.007

- Lemos, C. C., Fischer, T. B., & Souza, M. P. (2012). Strategic environmental assessment in tourism planning — extent of application and quality of documentation. Environmental Impact Assessment Review, 35, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eiar.2011.11.007

- Li, G., Yang, X., Liu, Q., & Zheng, F. (2014). Destination Island effects: A theoretical framework for the environmental impact assessment of human tourism activities. Tourism Management Perspectives, 10, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2013.12.001

- Liasidou, S. (2019). Understanding tourism policy development: A documentary analysis. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 11(1), 70–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1465063

- Luonila, M., Kurlin, A., & Karttunen, S. (2020). Capturing societal impact: The case of state-funded festivals in Finland. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 0, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2020.1839474

- Maguire, K., & McLoughlin, E. (2019). An evidence informed approach to planning for event management in Ireland. Journal of Place Management and Development, 13(1), 47–72.

- Mangion, M. (2011). Evidence-based policymaking: Achieving destination competitiveness in Malta [Doctoral thesis]. University of Nottingham.

- Mariani, M., Baggio, R., Fuchs, M., & Höepken, W. (2018). Business intelligence and big data in hospitality and tourism: A systematic literature review. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 30(12), 3514–3554. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM0720170461

- Mason, P. (2016). Tourism impacts, planning and management (3rd ed). Routledge.

- Matiku, S. M., Zuwarimwe, J., & Tshipala, N. (2020). Sustainable tourism planning and management for sustainable livelihoods. Development Southern Africa, 524–538. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2020.1801386

- Maxim, C. (2013). Sustainable tourism planning by local authorities: An Investigation of the London Boroughs [Doctoral Research Thesis]. London Metropolitan University Cities Institute.

- Mazanec, J., Wöber, K., & Zins, A. (2007). Tourism destination competitiveness. From definition to explanation? Journal of Travel Research, 46(1), 86–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507302389

- McCole, D., & Joppe, M. (2014). The search for meaningful tourism indicators: The case of the international upper great lakes study. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 6(3), 248–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2013.877471

- McLoughlin, E. (2017). A longitudinal study on local authority sustainable planning for tourism in Ireland: A focus on tourism indicator systems [Doctoral Research Thesis]. Institute of Technology.

- McLoughlin, E., & Hanrahan, J. (2016). Local authority tourism planning in Ireland: An environmental perspective. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 8(1-3), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2015.1043918

- McLoughlin, E., & Hanrahan, J. (2019). Local authority sustainable planning for tourism. Lessons from Ireland. Tourism Review, 74(3), 327–348. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-12-2017-0198

- McLoughlin, E., Hanrahan, J., & Duddy, A. (2020). Application of the European Tourism Indicator System (ETIS) for Sustainable Destination Management. Lessons from county Clare, Ireland. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 14(2), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-12-2019-0230

- McLoughlin, E., Hanrahan, J., Duddy, A., & Duffy, S. (2018). European tourism indicator system for sustainable destination management in county Donegal Ireland. European Journal of Tourism Research, 20, 78–91.

- McLoughlin, E., & Maguire, K. (2022). Evidence informed planning for Tourism. In Buhalis, D (Ed), Encyclopedia of tourism management and marketing. Edward Elgar Publishing (In Press)

- Modica, P., Capocchi, A., Foroni, I., & Zenga, M. (2018). An assessment of the implementation of the European tourism indicator system for sustainable destinations in Italy. Sustainability, 10(9), 3160. https://doi.org/10.3390/su10093160

- Mowforth, M., & Munt, I. (2016). Tourism and sustainability: Development and new tourism in the third world (4th ed). Routledge.

- Needham, M. D., & Szuster, B. W. (2011). Situational influences on normative evaluations of coastal tourism and recreation management strategies in Hawaii. Tourism Management, 32(4), 732–740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.06.005

- NHO Reiseliv. (2020). Korona-analyse for reiselivet. Retrieved April 17, 2020, from https://www.nhoreiseliv.no/tall-ogfakta/reiselivets-status-korona

- Noble, B. F. (2003). Auditing strategic environmental assessment practice in Canada. Journal of Environmental Assessment Policy and Management, 5(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1464333203001310

- Nunkoo, R. (2015). Tourism development and trust in local government. Tourism Management, 46, 623–634. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.08.016

- Page, S. J., & Dowling, R. K. (2002). Ecotourism. Pearson Education Limited.

- Pan, B., & Yang, Y. (2017). Monitoring and forecasting tourist activities with big data. Management Science in Hospitality and Tourism: Theory, Practice, and Applications, 43–62.

- Persson, I. (2015). Second homes, legal framework, and planning practice according to environmental sustainability in coastal areas: The Swedish setting. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 7(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2014.933228

- Pratt, S., & Alizadeh, V. (2018). The economic impact of the lifting of sanctions on tourism in Iran: A computable general equilibrium analysis. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(11), 1221–1238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1307329

- Richards, G. (1992). The UK local authority tourism survey 1991. Centre for Leisure and tourism studies. University of North London.

- Rio, D., & Nunes, L. M. (2012). Monitoring and evaluation tool for tourism destinations. Tourism Management Perspectives, 4, 64–66. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2012.04.002

- Ruhanen, L. (2010). Where's the strategy in tourism strategic planning? Implications for sustainable tourism destination planning. Journal of Travel & Tourism Research, 10.

- Ruhanen, L. (2013). Local government: Facilitator or inhibitor of sustainable tourism development? Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 21(1), 80–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2012.680463

- Santana-Jiménez, Y., & Hernández, J. M. (2011). Estimating the effect of overcrowding on tourist attraction: The case of canary islands. Tourism Management, 32(2), 415–425. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2010.03.013

- Sasaki, M. (2004). Creativity and cities: The role of culture in urban regeneration. Quarterly Journal of Economic Research, 27(3), 29–35.

- Saunders, M., Lewis, P., & Thornhill, A. (2000). Research Methods for Business students. Pearson Education.

- Scott, D., & Becken, S. (2010). Adapting to climate change and climate policy: Progress, problems and potentials. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 18(3), 283–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669581003668540

- Seraphin, H., Sheeran, P., & Pilato, M. (2018). Over-tourism and the fall of venice as a destination. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 9, 374–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2018.01.011

- Shao, J., Bai, H., Shu, S., & Joppe, M. (2020). Planners’ perception of using virtual reality technology in tourism planning. E-review of Tourism Research, 17, 5.

- Sharpley, R. (2008). Planning for tourism: The case of dubai. Tourism and Hospitality Planning & Development, 5(1), 13–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/14790530801936429

- Torres-Delgado, A., & Palomeque, F. (2018). The ISOST index: A tool for studying sustainable tourism. Journal of Destination Marketing & Management, 8, 281–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdmm.2017.05.005

- Torres-Delgado, A., & Palomeque, F. L. (2014). Measuring sustainable tourism at the municipal level. Annals of Tourism Research, 49, 122–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2014.09.003

- Twining-Ward, L., & Butler, R. (2002). Implementing STD on a small island: Development and use of sustainable tourism development indicators in Samoa. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 10(5), 363–387. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669580208667174

- UNWTO. (2004). Indicators of sustainable development for tourism destinations: A guidebook. UNWTO.

- UNWTO. (2020). International tourist arrivals could fall by 20-30% in 2020. Retrieved April 27, 2020, from https://www.unwto.org/news/international-tourism-arrivals-could-fall-in-2020

- Uysal, M., Sirgy, M. J., Woo, E., & Kim, H. L. (2016). Quality of Life (QOL) and well being research in tourism. Tourism Management, 53, 244–261. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2015.07.013

- Volo, S. (2015). Indicator. In C. Cater, B. Garrod, & T. Low (Eds.), The encyclopedia of sustainable tourism (pp. 277–279). CABI.

- Walton, J. K. (2013). ‘Social tourism’ in Britain: History and prospects. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 5(1), 46–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2012.703377

- Wang, S., King, C., & Heo, J. (2009). Residents’ attitudes toward urban tourism development: A case study of indianapolis, U.S.A. Tourism Today, 9, 27–43.

- Wilson, E., & Hollinshead, K. (2015). Qualitative tourism research: Opportunities in the emergent soft sciences. Annals of Tourism Research, 54, 30–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.06.001

- Xiang, Z. (2010). Modelling the persuasive effects of search engine results. Information Technology & Tourism, 12(3), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.3727/109830511X12978702284408

Appendix 1

Theoretical framework to examine Local Authority tourism planning and the use of tourism indicator systems