ABSTRACT

Since its emergence in the latter half of the twentieth century, public history has engendered ongoing transformations in the creation and dissemination of knowledge. Its aims, as well as efforts undertaken as part of its praxis, are reminders that collaborative engagements with individuals and communities can simultaneously serve to commemorate, educate and empower. Recent scholarship that examines pop-up events underscores both their significance to public history and the innovative potential they represent in celebrating LGBT+ lives and experiences. In particular, the extent to which they encourage considerations of space that are more attentive to localities and pluralities is indicative of the disruptive significance of small-scale events. Among other possibilities that lend themselves to expanding the reach of public history, particularly by adopting new modes of interpretation that place a premium on active engagement, creative arts programming provides a pathway to stimulating interest in exploring and understanding the past.

The work of OUTing the Past, a UK-based organisation, effectively reflects aspirations associated with public history, with the logistical benefits of pop-up events and the contributions of creative productions finding purchase in its programming. Documenting the commitments it makes to re/centring history and the frameworks it has strategically developed in realising these provides the impetus for this critical study of a multifaceted approach to promoting small-scale LGBT+ celebrations.

While early instances of collective action motivated people to take to the streets, Pride events have evolved over the years in ways that lay claim to large portions of urban and cultural landscapes. Today such celebrations are associated with multi-day events in cities around the world and have become destinations for queer tourism. Their increased scope and presence, as welcomed as this might be in resisting marginalisation and enhancing solidarity, has been accompanied by critical examinations of the various – and contested – forms of commodification, commemoration, and homonormalisation/nationalism accompanying their expansion.Footnote1 OUTing the Past (OTP), a not-for-profit organisation that coordinates various events in the UK and elsewhere, strategically pursues alternatives to large-scale gatherings by promoting local embeddedness and relevance when engaging audiences in the examination of LGBT+ histories.Footnote2 The public presentations and performances it facilitates typically take place in museums, libraries, galleries, community centres and specifically selected venues – spaces in which participants might better appreciate that remembering is essential to celebrating.Footnote3

The scale of events supported by OTP is not indicative of a lack of ambition; rather it reflects a commitment to activism and serving the needs of local audiences, attributes that inspired and have sustained efforts in public history. Indeed, Lara Kelland (Citation2018) reminds readers that grassroots agency in the service of uncovering the LGBT+ past played a significant role in the emergence of public history. The disruptive impulses that continue to shape it include sanctioning new sites of knowledge production, which helped to take history out of the formal confines of the academy, and simultaneously fostering new arrangements for sharing and disseminating this knowledge. These retain their salience in the context of large-scale celebrations insofar as commercial, promotional and logistical imperatives have reimposed structures against which interests in better appreciating the queer past continue to assert themselves.

Pop-up events have been one of the various means by which public historians have highlighted the interests and served the needs of particular communities (Kelland, Citation2018, p. 378). The spatial and temporal flexibility they represent fosters a freshness that can benefit audiences, providers and organisers. Of equal importance, their ability to re/centre meaningful engagements on localities and pluralities has been leveraged for a wide range of community-based activities that value specificity or granularity. In these regards, the transformative potential of pop-ups shares significant similarities to the work of OTP, which intentionally aims to prioritise the active, collaborative and nuanced participation of stakeholders rather than the kind of passive or consumptive atmosphere that can pervade large-scale Pride events.

This paper begins focusing on the work of OTP with a brief account of its origins, which serves to contextualise its mission to address ‘silence and denial by promoting … rich and fascinating insights into past attitudes and behaviours related to sexuality and gender’ (OUTing the Past, Citationn.d.). In addition to its historically relevant content, the overview also details the model that the organisation has developed over the years to deliver the longest-standing element of its programming: LGBT+ History Month. Aligning with several key tenets of public history, the infrastructure that OTP provides emphasises connectivity and participation by empowering local sites to curate programmes that best reflect their communities, as well as their particular commitments to social change and civic engagement. The paper continues with a section that considers the implementation of these strategies and incorporates testimonials from local event coordinators, some of which specifically address engaging queer youth. It also reflects on inherent challenges in critically examining OTP’s cohesive and collaborative, yet intentionally diffuse and transferrable, model for celebration and commemoration.

Heritage premières, new plays based on original historical research, have become an innovative and transformative component of programming that OTP has coordinated in the UK in recent years. Staged with the involvement of local organisations and audience members, forms of engagement that reinforce associations with public history praxis, these performances encourage a variety of interpretive perspectives by intentionally adopting creative ways for reflecting on past lives and experiences. Further developing themes of participation and re/connection, the final section of this paper considers another element of OTP’s endeavours by focusing on its efforts to employ theatre and dramaturgy as ways of extending the reach and scope of LGBT+ history. At the same time, the synergies created by and through its heritage premières underscore commitments to intimacy and provide opportunities for transgenerational understanding through the work of creatively completing and staging the past.

OUTing the Past in historical context

The emphasis that OUTing the Past places on efforts to expand understanding through public engagements with queer history makes it natural to begin by briefly recounting the organisation’s lineage. Indeed, the spirit of activism that inspired early Pride events permeates both the heritage and ethos of OTP, and Sue Sanders (Citation2020, p. 47) traces its origins to the emergence in 1974 of a small number of union activists from around the UK who collectively identified as the Gay Teachers Group. The transformation from a social to a politically active group was largely a response to the firing of one of its members after being outed. The Gay Teachers Group soon became Schools OUT UK and adopted a mission of combatting homophobia. Sanders took on a leadership role in the 1990s and remains chair of the charity to this day.

Complementing her commitment to Schools OUT UK, Sanders was involved in developing and providing resources that could be used in schools as well as delivering equality training workshops. She recounts her early engagements as being galvanised by two disparate but significant events in modern British history associated with institutionalising injustices: the enactment of Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988 and the 1999 release of MacPherson Report into the death of the Black teenager Stephen Lawrence (Sanders, Citation2020, pp. 47–49). In particular, Section 28 prohibited schools, as well as local councils, from ‘promoting the teaching of the acceptability of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’ (National Archives, Citationn.d.). Responding to the homophobia that underpinned and attended the imposition of Section 28 was a call to many, and the activism imbuing early Pride marches in the UK has a direct relationship to efforts that led to repealing the law in 2003.

Sanders’ efforts in confronting and combating homophobia merged with an increased institutional openness to acknowledging and addressing discrimination that followed the release of the MacPherson Report. In particular, she acknowledges the importance that Black lesbian feminists had on the trainings she was then developing and facilitating (Sanders, Citation2020, p. 49), which made clear to her the need to reclaim lesbian histories that had long been hidden. At the same time, Sanders recognized the power associated with the emergence of Black History Month in the US in the 1970s and worked within a network of fellow activists who were subsequently inspired to establish October as a time to both celebrate and focus attention on Black British history. Sanders and her Schools OUT UK co-chair, Paul Patrick, were also encouraged by queer activism in the US in the 1990s that was laying claim to October as a time to celebrate LGBT+ history and dedicated themselves to creating a similar space in the UK. Attentive to the pedagogical relevance of their efforts, as well as the academic calendars followed by the schools they sought to transform, they settled on February as the month that best provided that space, and the first LGBT+ History Month took place in 2005. Today, OTP works in partnership with Schools OUT UK, though it now plays a more direct role in coordinating and delivering events.Footnote4

Programming LGBT+ History Month

The programming specifically associated with LGBT+ History Month developed organically and in response to the voluntary and grassroots nature of both Schools OUT UK and OUTing the Past. Over time, however, a productive model for events emerged that is both collaborative and distributive. As a first step in one thread of programme development, a call for contributions is typically disseminated in August using established lists and networks associated with those working in the heritage sector as well as outreach that leverages OTP’s website and social media. The call and the submission form that accompanies it are designed to encourage a broad range of participation, from academics and heritage professionals, to those engaged in community-level projects, to amateur historians, to others who offer unique testimonials that can provide new information or readings on the queer past. A key guideline informs both the solicitation and review processes: proposed presentations should showcase an evidence-based engagement with the past that draws upon archival resources, ephemeral materials, or personal oral testimonies. Submissions are reviewed by OTP’s Academic Advisory Panel as a way of ensuring that proposals align with its mission to ‘popularize the study, and hence a fuller understanding, of past attitudes towards sex and gender diversity … among the general public’ (OUTing the Past, Citationn.d.). The proposal review process results in a ‘gazette’ of presentations that is formally adopted and circulated by OTP.

Alongside the work of developing the gazette, organisations and venues are invited to apply to host an event as part of the LGBT+ History Month programme. Selected venues, which are termed ‘hubs’, undertake a number of tasks to ensure a consistent standard of programme delivery, including accessibility, the provision of dedicated space for presentations, the ability to accommodate presenters, a commitment to partner with OTP in terms of scheduling and promoting the event and an acknowledged awareness of OTP’s mission to increase the public’s awareness and engagement with LGBT+ history. Beyond addressing shared aspects of hosting an event, each hub selects presentations from the gazette produced by OTP to develop a programme that best reflects its organisational aims, interests and undertakings. For many organisations partnering with OTP represented their first efforts to showcase LGBT+ history, thereby enabling them to deepen their connections with local queer communities and patrons. Hubs in the UK collaborating with OTP in recent years span a variety of venues, from well-known sites such as Royal Museums Greenwich, National Museums Liverpool, Ulster Museum and the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust, to local support organisations such as the Leicester LGBT Centre and the Belfast-based Cara-Friend. Further, the transportability of the OTP model has led to events that have taken place in the Republic of Ireland, Norway, Sweden, and the US in recent years.

Scholars have critically examined the extent to which large-scale Pride events, since their emergence in connection with queer activism, have become ‘fixed’ or normalizing spaces (Da Costa, Citation2020; McCartan, Citation2017; Nyugen, Citation2020; Stillwagon & Ghaziani, Citation2019). While reinscribing certain aspects of fixity in focusing part of its attention on the UK during a specific period of time identified as ‘history month’, the efforts of OTP, as well as its model for undertaking these, represent disruptive impulses. For one, these seek to re/centre the significance of history and testimonials of lived experiences as the responsive impetus for reflecting on both the reasons and the reticence for taking part in public celebrations of queerness. Additionally, the collaborative yet diffuse model transparently embraces the power of networking. It encourages the kind of shared authority that Cantwell et al. (Citation2019) acknowledge as a practice fundamental to public history but that large-scale events complicate with their tendency toward simultaneously consolidating and obscuring oversight. While not fully leveraging the ephemeral and transient potential of queer pop-up events that have recently received greater attention (Stillwagon & Ghaziani, Citation2019), occupying the liminal spaces that exist between local, regional, and more broadly conceived frameworks for the production and dissemination of historical knowledge is central to the work of OTP. Further, the provision of potential presentations through its gazette is undertaken in the spirit of promoting the agency of hub coordinators and can serve as a partial remedy to, in the words of Stillwagon and Ghaziani (Citation2019, p. 878), ‘reproducing exclusive organisational strategies’.

Some advantages associated with OTP’s model for coordinating LGBT+ History Month became apparent in response to the Covid-19 pandemic that began in 2020, which must be acknowledged as defining the current parameters of commemorations and celebrations of any kind. In particular, and building on efforts to archive video recordings of presentations made in 2019, the scale of hub events combined with the connective activism that sustains the work of OTP allowed for an obvious pivot to online delivery that didn’t unduly dilute programmatic intentions. In some ways, adopting a virtual platform seems an inevitable endpoint for attempts to break away from the prescriptive constraints associated with large-scale events that are typically imposed by the demands of both time and space. Even so, trade-offs come with providing new possibilities for engagement that might better accommodate a range of circumstances by relying exclusively on those mediated by technology, the costs of which extend to limiting queer collective agency. Though beyond the scope of this paper to consider in detail, the participatory hybridity accelerated by responses to the global pandemic is, in many ways, as exciting a prospect as physically coming together once again to share and rejoice in the kind of immediacy that is at the heart of small-scale events.

Significant aspects of programming LGBT+ History Month

Both pop-up events and programmes that support the presentation of public history are particularly salient to encouraging new formations of queer space and engagements with the past (Ferentinos, Citation2019; Ghaziani, Citation2019; Nyugen, Citation2020; Stillwagon & Ghaziani, Citation2019). Against a backdrop of innovative re/negotiations that emphasise geographical and participatory pluralities, survey responses provided by hub coordinators associated with LGBT+ History Month in 2021 speak to a more diffuse – yet fundamentally recognisable – sense of commemoration. The most commonly shared comments reflect the extent to which the collaborative OTP model effectively integrates with organisational missions related to outreach, programming and inclusion. At the same time, the partnering relationship offers strategic advantages in connecting local programming to a framework that affords broader reach and recognition. John Donegan of Leeds Museums and Galleries underscores the significance of these intertwined strands: ‘I think since we've been running [OTP] events, our communities find it easier to believe in us. It helps that this isn't just a single (however important) thing, but is representative of our whole approach to inclusion and engagement, programming and storytelling’ (personal communication, June 1, 2021). The connectivity represented by the OTP model features prominently in the response provided by Melissa Hawker, Learning Officer at the Ancient House and Lynn Museum in Norfolk: ‘It is very important for us as a small museum in a small town to demonstrate that LGBT+ history is everywhere, not just in large towns and cities. These small events have [a] massive impact in terms of making audiences feel represented and included’ (personal communication, June 8, 2021).

According to survey responses, the gazette of presentations offered by OTP serves as a resource for coordinators who hope to address particular topics in the absence of local contacts who can speak to them. The respondent from Stockport Libraries sees this as a strength of the OTP model: ‘It is great to have a wide variety of speakers covering so many topics. This allows you and your partners to choose talks that you hope are most relevant and of interest to your audience’ (personal communication, June 1, 2021). In the opinion of the respondent from the National Gallery of Ireland, the gazette ‘takes the pressure off smaller institutions that may not have the resources or connections to access such a broad range of speakers’ (personal communication, June 8, 2021). The survey response received from Derby Museum amplifies the benefits of the information provided by OTP: ‘The [gazette] process means there are vetted, trusted presenters to choose from, something that would be very difficult to develop and resource ourselves. It is important to work with the … [OTP] … team as this gives confidence that we are creating something that is sensitive and appropriate, but also pushing boundaries’ (personal communication, June 9, 2021). While not without challenges, some of which are considered below, the gazette of presentations has the potential to foster the development of local voices – whether within or outside of the OTP model. This possibility is clearly expressed by Hawker in one of her survey responses: ‘I think that we … worked with a number of fantastic people on our projects, and they too would have made great speakers at our [hub] event. If we had been involved earlier, we could have encouraged them to apply and be part of the gazette’ (personal communication, June 8, 2021). Hawker’s enthusiasm notwithstanding, the flexibility of the OTP model extends to hubs developing programmes that feature speakers identified by event coordinators in addition to those whose presentations are included in the gazette.

Providing a gazette of presentations also serves ends related to both programmatic nuance and afterlife. The extent to which pop-up events challenge assumptions regarding a diminished need for queer spaces and the ‘declining centrality of sexual orientation’ (Stillwagon & Ghaziani, Citation2019, p. 875) is reflected in the ongoing work by heritage organisations to make meaningful connections with LGBT+ individuals and communities. Opportunities to expose and embrace aspects of cultural significance are acts of resistance to assimilationist tendencies, and events that specifically highlight queer history represent interventions that can simultaneously compliment these efforts and respond to a loss of detail that arises ‘when queer experiences become part of a larger narrative’ (Ferentinos, Citation2019, p. 26). John Donegan expresses his appreciation of the OTP model for allowing Leeds Museum and Galleries to centre history as an explicitly vital part of its programming. He also underscores the utility of the gazette to sustaining a ‘queer throughout the year’ approach to coordinating events by linking the institution to individuals who can contribute a range of historical perspectives and expertise (personal communication, June 1, 2021). For partners like Donegan, this feature of the OTP model has the potential to disrupt a kind of chrononormativity that might otherwise relegate queer programming to particular times of the year.

Beyond commenting on its collaborative and cohesive intentions, survey responses surfaced two particular benefits of the OTP model that are worthy of specific consideration in terms of highlighting aspects of public history reflected by event programming. Exploring each of these entailed interviewing the relevant hub coordinators as a way of expanding on their survey responses.

Centring the significance of local sites

Cognisant of their once comparatively radical potential as sites for individual and collective empowerment (Bruce, Citation2016; Peterson et al., Citation2018), Pride celebrations have increasingly come to rely on urban centres to provide the venues, amenities and leisure infrastructure that support event tourism in an age of neoliberal commodification (Adam, Citation2009; Johnston, Citation2007). The alternatives and anonymity such destinations provide will certainly be welcomed by many; for some, however, taking part in such large-scale events entails what might be termed ‘dislocation by design’. Concerns regarding assimilation (Taylor, Citation2014) can be extended to many of the groups and organisations that take part – and particularly those outside of the corporate sphere – insofar as they can be relegated to competing for the attention of revellers as a parade float or to setting up a stall as part of a fringe ‘marketplace’. Again, there are undoubtedly benefits that come with visibility and outreach, but they are mediated by the ever-more-commercialised logistics and dynamics associated with large-scale events. In particular, and among other relevant considerations not addressed herein, groups and organisations can too easily find themselves serving the event by enriching the scope of the celebrations rather than the event effectively serving to enhance or further their ongoing work.

The model adopted by OTP for its LGBT+ History Month events centres activities on particular venues in their capacity as programme curators and hosts. This feature is one that gives shape to the efforts of hub coordinators like Debbie Challis at the Library of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Central to her thinking is programming that leverages content associated with the gazette of presentations so as to encourage public engagements with the archival collection held by the library. While the academic setting is – or can be perceived to be – at some remove from local audiences and its collections may not directly reflect their particular concerns, challenges acknowledged by Challis, together they offer a space for building stronger connections with the public as well as for showcasing specific content associated with themes that resonate more broadly.Footnote5 In these regards, partnering with OTP is considered one of several pathways for fostering interest in the collection. Underscoring multidirectional possibilities for growth, Challis also admits that, for her, greater familiarity with the content and relevance of the library archive to understanding the queer past is an added benefit of the networking inherent in the OTP model. Finally, she welcomes the interactions that can emerge at small-scale events owing to audience participation that is motivated more by pursuing and sharing individual interests than by spending time and socialising with friends (personal interview, June 8, 2021).

Melissa Hawker (personal interview, June 24, 2021) articulates a different benefit of prioritising local agency and heritage through her participation as an OTP hub coordinator. Her ongoing association with the Ancient House Teenage History Club, which will shortly be discussed in greater detail, included taking the group to London Pride in 2019, during which they raised the profile of their work on exploring the queer history of Norfolk at a pop-up exhibition in Trafalgar Square. They followed this by contributing to Pride events around their county. As gratifying as those efforts were for the club, Hawker relates that hosting an OTP hub event became an imperative for the group based on those experiences and their growing confidence. According to her, the club members ‘really enjoyed London Pride … [and] were really glad they went … but really liked the local [events] … because they were telling local stories’. Moreover, it was their 2021 hub event that Hawker maintains attracted significant local attention:

Lots of my colleagues from other parts of Norfolk County Council suddenly woke up to the fact that the teenagers have been doing a lot of this work. Because they saw the [LGBT+ History Month] advertising, they came to see the presentations and they were like ‘Oh, actually, this is good stuff’. … There are kudos and branding that’s part of this national festival with multiple hubs, and you’re one of them. You name-check a few that are high profile and suddenly your event gets taken more seriously. You can say ‘Oh, this is the same thing that [took place in London] last week’, and they're like ‘Oh, we better take this seriously’.

Empowering and amplifying intergenerational engagements with queer history

Norfolk’s Ancient House Teenage History Club reflects the intergenerational potential associated with the OTP model. According to Hawker, who oversees the group’s activities, members of the club became interested in queer history as they developed a play set in the late Victorian period and featuring a homosexual relationship. She recalls that they were ‘livid’ to learn that sex between men was illegal at the time and that change wouldn’t come until 1967 (personal interview, June 24, 2021). Hawker used materials made available by Schools OUT UK to help educate the group on LGBT+ history and, so, was made aware of events coordinated by OTP. At the same time she was helping the group to develop its commitment to exploring local heritage and providing resources to its community. According to Hawker, ‘the club mounted an exhibition … at the [Ancient House] Museum with objects and text panels, which they curated themselves [and] wrote themselves. They did the whole thing’. They also programmed family-friendly events and a comedy night at which club members performed as queer historical characters. Supplementing Hawker’s reflections, the club has documented and archived much of the work discussed herein on their Ancient House Queer History YouTube playlist (Ancient House Museum of Thetford Life, Citationn.d.).

With considerable accomplishments behind them, the confidence of the club members continued to grow, and they were ready to take their commitment to LGBT+ history to another level. They were accepted to host an OTP History Month event in 2021, and Hawker reports that they embraced this opportunity to address their particular concerns with a ‘We can do this!’ attitude (personal interview, June 24, 2021). A key aspect of their efforts was one of ownership, which the OTP model and gazette of presentations helped them to exercise to a great extent in approaching their role and work as hosts. In particular, the club reviewed past hub programmes and identified themes that they wanted to amplify through the one they curated. This included highlighting intersectionality – particularly regarding race and ability. Section 28 was another topic that club members wanted to feature, which allowed them to reflect on the afterlife of the act repealed in 2003, insofar as it might continue to bear on the present-day experiences of LGBT+ youth in schools. Hawker recounts that a sense of youthful resilience informed the club’s programming considerations; they sought to ensure that difficult topics would be addressed without the programme becoming ‘too depressing’. The club solidified its sense of ownership by facilitating the (online) event logistics on the day, when members took responsibility for introducing presenters and moderating sessions.

The partnership established between the Ancient House Teenage History Club, Hawker and OTP speaks to fostering intergenerational conversations, activism and agency. It represents one possible intervention that museums can undertake in relation to youth programming and promoting new modes of interpretation that align with public history praxis (Ferentinos, Citation2019, pp. 32–33). Moreover, the model adopted by OTP empowers their participation by providing resources while giving significant latitude to hosts in pursuing their organisational or programmatic priorities. The networking that is essential to the distributive yet collaborative model also serves to encourage a sense that museums and heritage sites are vitally important to the work of creating spaces for queer youth to pursue their interests in exploring the past as well as to communicate their perspectives on contemporary concerns.

Challenges

Some of the challenges faced by OUTing the Past are familiar to many small non-for-profit volunteer organisations, while others are specific to its model for programming LGBT+ History Month. While commitment typically overcomes fatigue, OTP staff shoulder significant levels of responsibility alongside other personal and professional obligations. Even so, sharing coordination and energy with hub partners helps in managing workloads. Venues can also adjust to various schedules by taking time off from hosting events, which helps to alleviate burn-out. Participatory flexibility extends to presenters as well. Though some individuals have had several presentations featured in gazettes in recent years, there is a significant degree of turnover in proposals received. Even so, feedback from hub partners indicates that streamlining and simplifying the application process might effectively increase participation by making it easier to both reach and receive proposals from potential presenters.

Several logistical concerns relate, in varying degrees, to negotiating aspects of shared authority. For one, hub coordinators acknowledge that, in their efforts to address diversity through their history month programmes, they have found themselves unintentionally featuring the same presenters. Maintaining the autonomy of hubs in curating their programmes, therefore, provides a further impetus for increasing the range of identities, perspectives and communities reflected by OTP through its gazette of presentations. The reach of its responsibilities may extend in other directions as well. In particular, and while risk-sharing can foster experimentation, the OTP model tacitly aligns with institutional practices rather than explicitly encouraging provocations or critical interventions. Concerns related to ‘authorised heritage’ (Smith, Citation2006) are mediated to a considerable extent by the progressive impulses that encourage venues to host events; still the model is primarily dedicated to facilitating rather than interrogating the practices of its partners. Another programmatic arm of OTP is, however, positioned to do this work by coordinating an annual conference. The event, which seeks to engage academics, heritage professionals and activists, represents a response to a critique offered by Mills (Citation2006) regarding the scholarly integrity of the first LGBT+ History Month programme. Even so, concerns such as this, as well as informed discussions regarding best practices, might be effectively addressed by intentionally creating synergies between the public-facing and more academically-situated efforts of OTP in promoting queer history.Footnote6

OUTing the Past heritage premières

Heritage premières represent another way that OUTing the Past engages both local sites and audiences in re/connecting them to LGBT+ history. This section considers two particular productions that exemplify the significance of siting and staging in deploying strategies that, in their respective cases, call attention to absences and feature immersive dramaturgical techniques in the telling of hidden histories. As one possible response to the encouragements to public historians recently offered by Ferentinos (Citation2019), which highlight new modes of interpretation, this aspect of OTP programming underscores the use of the arts to create a speculative picture of the queer past as well as the benefits of involving young people in theatre making that attempts to bring it to life for contemporary audiences.

Locating a scandal: the first heritage première

To mark its tenth anniversary in 2015, OTP decided to create a city-based festival of popular history that it would programme in Manchester as part of LGBT+ History Month. Part of the vision was to dramatise for live performance a local history that had been forgotten as a way of reaching new audiences and engaging existing ones differently. The originator of the idea, Jeff Evans, was then undertaking doctoral research into criminal prosecutions for sex between men in Lancashire. As part of that work, Evans (Citation2016) re-examined accounts of a large police raid on an all-male fancy dress ball at the Temperance Hall in Manchester in 1880, at which the police alleged various forms of immoral and sexualised behaviour occurred. Brady and Hornby (Citation2015) dramatised the story into a trilogy of one act plays (The Raid, The Press and The Trial) under the collective title of A Very Victorian Scandal, each of which was staged at different non-theatrical locations (see ). Historical documentation of the arrests and trial formed a significant element of plays’ narratives, and the dramatic form licensed speculation about private sexual identities and hidden motivations for which there was no substantiating documentation. While a historian may vacillate over possible alternatives in the face of a lack of evidence, a dramatist must decide whether a character does or does not do something, is or is not something. Absences brimming with queer implications can be both filled and embodied. This ability to work from the historical record while creatively addressing queer absences is something that Ferentinos values as one of the contributions that the arts can make to public LGBT+ history (Citation2019, p. 31).

Figure 1. Dan Wallace as Kitty Heartstone (right), Gareth George as Henry Newman (left). The Midland Hotel appears in the background. Photo credit: Nicolas Chinardet.

The option of using the original Temperance Hall for the performance was impossible owing to the fact that the building had been demolished, with the site now part of a busy road interchange. The Court where the original trial took place was similarly lost. Responding to these absences led to the concept of ‘proximal equivalence’: in essence, identifying the nearest extant equivalent spaces in terms of social function. These needed to be proximally equivalent in a number of ways that were not necessarily complementary to the technical requirements of staging drama, but a venue was found for each part of the trilogy. The Raid was staged at Via, a large bar and restaurant that has long been a popular venue in Manchester’s Gay Village. Via was decorated using elements of deconsecrated churches, some of which were Victorian, and met various space requirements for the songs and dances that were part of the piece. The Press was staged at Manchester Central Library, whose windows offer a view of the Midland Hotel, a site referenced in the memoirs of the policeman who led the raid (see ). The Trial was staged in the People’s History Museum, where huge Victorian windows face the Manchester Justice Centre. Each site offered a different form of resonance with the historical events being performed within it. Moreover, using non-theatre spaces generated both significant numbers of attendees and new forms of engagement. Individually, each act of A Very Victorian Scandal was better attended than any other LGBT+ History Month event scheduled in 2015.

Providing feedback required by Arts Council England reporting, staff at each hosting space testified to the different audiences and to their keenness to continue to work in this way as a measure of the value they place on participating in new forms of historical engagement (personal communication, March 2015). Catherine O’Donnell, People’s History Museum’s Engagement & Events Officer, said:

The unique nature of the performance and its major billing in the festival brought new audiences to the museum. We feel that bringing a story that has been hidden from history to life in an engaging and innovative way, will broaden the appeal of LGBT history and therefore the value of the work goes beyond an artistic production.

The 50th anniversary

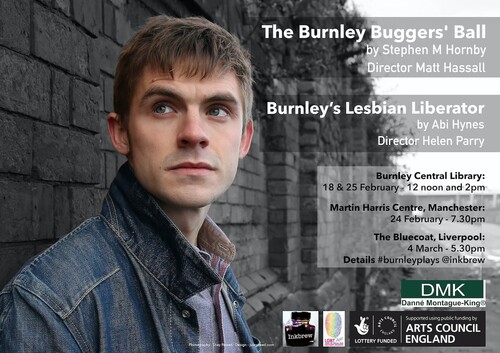

Ferentinos (Citation2019) opens her article in anticipation of the 50th anniversary of the Stonewall riots. In England and Wales, 2017 saw another 50th anniversary, that of the Sexual Offences Act 1967, which began the process of decriminalising male homosexual acts and was generating a not dissimilar wave of cultural production. OTP marked this milestone with a drama that showed ordinary people grappling with the impact and implications of partial decriminalisation (see ). Evans, by now OTP’s LGBT+ History Month coordinator, identified the event to be dramatised: on July 30, 1971, the first ever attempt to open what might now be called an LGBT+ centre, an ‘Esquire Club’ in the nomenclature of the time, ended with a large public meeting in the Burnley Central Library organised by the Campaign for Homosexual Equality (CHE). As Scott-Presland (Citation2015, pp. 217–225) documents and observes, the meeting itself did not succeed in founding a club, but an unexpected alternative victory was achieved. The meeting turned into a mass coming-out, possibly the first in the UK and certainly the first in the North of England. Allan Horsfall, one of the organisers of the meeting and a pioneering, life-long LGBT+ rights activist, described it as the most successful meeting the CHE ever had.

Contrasting the absence of sites associated with A Very Victorian Scandal, the Burnley Central Library was not only extant, but also largely structurally unchanged since the 1970s. The meeting room on the first floor, where the seminal ‘Homosexuals and Civil Liberty’ meeting took place, had been mothballed in 2015 owing to budget cuts, but the library staff offered to recommission the room for the project. Further, grainy copies of newspaper photographs of the original meeting survived (Scott-Presland, Citation2015). These images and the survival of the room itself offered the possibility of a heritage première with a new level of verisimilitude, matching the play chair-by-chair, jacket-by-jacket and cornice-by-cornice with the visual record of the original event. The meeting was also centred, inevitably, on people coming together in a public space, many of whom were perhaps as much viewers, at least for part of the time, as they were activists. The existence of a viable performance space at the original site, the nature of the originating event as one already incorporating an audience and the level of visual documentation invited an immersive dramaturgical response, one where the audience is not simply observing but is a participant within the world of the play. Moreover, immersive techniques could be used to place the audience in a political position, making choices that conflated actions in the past with a moment of decision in the present.

The Burnley Buggers’ Ball (Hornby, Citation2017; see ) used both elements of traditional spectatorial theatre and immersive techniques, with a clear split occurring in the middle of the performance.Footnote7 For the first half, the audience occupied two blocks of traverse seating, facing each other, while the play dramatised the weeks leading up to the meeting. At this point, the audience had to stand, pick up their chairs and reposition themselves to create an end-on space with a speaker’s podium, thus recreating the layout of the room for the original meeting. The actors welcomed the audience, announced that the meeting was about to start and took to the podium. This created three shifts: one temporal, one performative and one in the dynamic expectations of the audience. They find themselves in the meeting room in 1971 as events unfurl in real-time: speeches are made, vicars decry them from the floor and the London-based Gay Liberation Front (GLF) arrive to offer their solidarity (see ). The audience are immersed members of the gathering, encouraged to take sides, to heckle or to shout out their support. The spectatorial conventions of a silent theatre audience are rowdily eschewed, with some actors in the audience prompting them to respond. The play then recreates a unique moment from the meeting, a moment that invites the distinction between audience and performer to break down and overtly conflates the identity politics of the past into the present in an uncomfortable test of how far society has come.

Figure 3. Michael Justice as Allan Horsfall (left) faces Christopher Brown as Andrew Lumsden (right) with members of the Burnley Youth Theatre. Photo credit: Nicolas Chinardet.

The leader of the GLF storms the speakers’ platform and challenges the more conventional CHE meeting organisers. He stands before the audience and says, ‘We are talking as if there are two gay men in this room and five in the whole of Lancashire. I want you to stand. Stand up if you’re gay’ (Hornby, Citation2017). The actor makes it clear that he is directly addressing the immersed audience and ad libs several injunctions to stand, in response to which audiences at each performance behaved differently, some standing with more or less alacrity. The point of the moment, however, was not in how many people stood, but in placing each individual member of the audience in the position of deciding whether they would stand or not. This crucial immersive dramaturgical element attempts both to speak to the bravery of the men who did stand in 1971 and to act as a litmus paper for how much things had or had not changed by 2017 as the audience faced that same challenge.

Because of the potentially complex emotions that such techniques can engender, discussion sessions followed each performance in Burnley. These sessions, where audience members typically question actors and directors, instead took on the character of an open processing forum as Paul Fairweather, who chaired them, observes: ‘The feedback … was very moving, especially a sense expressed by some LGBT people who were born in Burnley, but who had left the town, that they now felt more connected with their birthplace’ (personal communication, March 2017). Rachel Hawthorn, Burnley Arts Engagement Officer, also spoke to the energising effect locally: ‘It's really important to uncover and celebrate these important pieces of LGBT history that took place here … Burnley residents have been inspired by the plays and the obvious artistic quality of the project’ (personal communication, March 2017). Staff who managed the library also saw the way in which the play engaged its audiences with a history that they were sometimes unfamiliar with. As Marian Taylor, Operational Library Manager, Lancashire County Council, observed: ‘The library [was] keen to host the plays due to their significance to Burnley and to the library itself … Many of the audience did not appreciate the significance of the events which occurred in their own hometown … ’ (personal communication, March 2017). In total 548 people saw the show across six performances, four of which were staged in the Burnley Central Library.

The continuing difficulties associated with identifying as LGBT+ were attested to by another element of the project. Specifically, members of the Burnley Youth Theatre took on roles as GLF activists in the performance, each having a few lines and licence to ad lib during the recreation of the meeting (see ). Ferentinos (Citation2019) singles out engaging young people with LGBT+ history as vitally important work. Indeed, reflecting on the past has the potential to take on a new significance in light of levels of self-harm, bullying and isolation that can affect young LGBT+ people. As Ferentinos (Citation2019, pp. 33-34) observes:

Learning that others in the past struggled with similar challenges and still prospered may literally save a life – either by demonstrating to someone who is struggling that they are not alone or by eroding the fear and ignorance that so often contributes to the miserable circumstances many LGBTQ youth face.

Our young people developed in confidence throughout the project and gained a lot of motivation for activism around LGBTQ+ issues. Most of the young people involved are now going on to perform their own LGBTQ+ piece … to over 1000 local young people through a schools tour … All the learning and development they have gained through being involved in this project will help them to tackle homophobia and LGBTQ+ issues through their work (personal communication, March 2017).

Meaningful connections with the past are among those that large-scale Pride events can strain, if not severe completely. Finding continued relevance in counteracting disassociations such as these, many of the practices associated with public history aim to foster robust forms of connectivity that serve both the creation and dissemination of knowledge. In particular, incorporating the active participation of various stakeholders and supporting particular audiences are essential aspects of these efforts. Pop-up events have also played an effective role in public history praxis, even as they have been adapted to other forms of community-building and celebration. Programming for LGBT+ History Month coordinated under the auspices of OUTing the Past leverages a collaborative model of engagement that prioritises the agency of local hosts in serving their communities, while offering some of the benefits of adopting a pop-up platform. Additionally, the heritage premières that OTP commissions and stages encourage new interpretative perspectives on the queer past through their dramaturgical practices. Together, these strands represent productive approaches to harnessing the reflective and transformative potential of small-scale events in re/making connections between celebrating and remembering.

Disclosure statement

Both authors are members of the OUTing the Past Academic Advisory Panel. K. G. Valente serves as Programme Coordinator for its academic conferences and is also a director of OUTing the Past Festival LTD, which was established to oversee finances associated with delivering the academic conferences it hosts. Stephen M. Hornby is Playwright in Residence to LGBT+ History Month. Funding for the theatrical productions discussed in this essay was provided by Arts Council England, Danne Montague-King, Schools OUT UK and private patronage.

Notes

1 Such themes have received scholarly attention from, among many others, Da Costa (Citation2020), Holmes (Citation2021), Johnston (Citation2007), Lamusse (Citation2016) and Waitt (Citation2008).

2 With the exception of quoted content, the incorporation of ‘LGBT+’ throughout rather than ‘LGBTQI+’ acknowledges the acronym currently adopted by OTP in relation to its various programming efforts.

3 Concerns related to the ways that Pride events have become increasingly detached from activism -- as well as the diminution of historical awareness that makes it easier to overlook such uncouplings -- were central to protests that attended celebrations in Manchester in 2021. Media reports by Maidment (Citation2021) and Pidd (Citation2021) communicate both sources of tension and the responses they engendered.

4 The partnership that resulted from the emergence of OTP as a separate, not-for-profit enterprise allows Schools OUT UK to maintain a primary focus on developing LGBT-inclusive materials and lesson plans for teachers while continuing to promote pathways to new knowledge and wider audiences for LGBT+ history.

5 Among these, Challis notes holdings related to queer campaigning since the 1950s.

6 History Month programming, the heritage premières discussed in greater detail in the following section and the annual conference currently constitute the main ways that OTP encourages reflection on LGBT+ history across the year.

7 A recording of The Burnley Buggers’ Ball and another heritage première production can be found on the OTP YouTube channel (OTP Heritage Premiers, Citationn.d.).

References

- Adam, B. (2009). How might we create a collectivity that we would want to belong to? In D. M. Halperin, & V. Traub (Eds.), Gay shame (pp. 301–311). University of Chicago Press.

- Ancient House Museum of Thetford Life. (n.d.). Playlist [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved August 4, 2021 from https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCKWo8PNwK0pj-swIIebFBqw/playlists.

- Brady, R., & Hornby, S. M. (2015). A Very Victorian Scandal [Unpublished play].

- Bruce, K. M. (2016). Pride parades: How a parade changed the world. New York University Press.

- Cantwell, C. D., Hinds, S., & Carpenter, K. B. (2019). Over the rainbow: Public history as allyship in documenting Kansas City’s LGBTQ pas. The Public Historian, 41(2), 245–268. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.245

- Da Costa, J. C. R. (2020). Pride parades in queer times: Disrupting time, norms, and nationhood in Canada. Journal of Canadian Studies, 54(2-3), 434–458. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcs-2020-0045

- Evans, J. G. M. (2016). The criminal prosecution of intermale sex 1850- 1970: A Lancashire case study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Manchester Metropolitan University.

- Ferentinos, S. (2019). Ways of interpreting queer pasts. The Public Historian, 41(2), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.19

- Ghaziani, A. (2019). Cultural archipelagos: New directions in the study of sexuality and space. City & Community, 18(1), 4–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12381

- Holmes, A. (2021). Marching with Pride? Debates on uniformed police participating in vancouver’s LGBTQ Pride parade. Journal of Homosexuality, 68(8), 1320–1352. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2019.1696107

- Hornby, S. M. (2017). The Burnley Buggers’ Ball [Unpublished play].

- Johnston, L. (2007). Queering tourism: Paradoxical performances of gay Pride parades. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203963807.

- Kelland, L. (2018). Public history and queer memory. In D. Romesburg (Ed.), Routledge history of queer america (pp. 371–381). Routledge.

- Lamusse, T. (2016). Politics at pride? New Zealand Sociology, 31(6), 49–70. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/informit.507933240724129

- Maidment, A. (2021, August 16). ‘Pride is ours and we want to make it that way again’: The protesters aiming to reclaim the roots of Manchester Pride. Manchester Evening News. https://www.manchestereveningnews.co.uk/news/greater-manchester-news/pride-ours-want-make-way-21291884.

- McCartan, A. (2017). Glasgow’s queer battleground [Unpublished master’s thesis]. Brock University.

- Mills, R. (2006). Queer is here? Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender histories and public culture. History Workshop Journal, 62(1), 253–263. https://doi.org/10.1093/hwj/dbl006

- National Archives. (n.d.). Local Government Act 1988. Retrieved July 27, 2021, from https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1988/9/section/28/enacted.

- Nyugen, T. (2020). Pop-up or permanent? The case of the mardi gras museum. In J. G. Adair, & A. K. Levin (Eds.), Museums, sexuality, and gender activism (pp. 81–89). Routledge.

- OTP Heritage Premiers. (n.d.). Playlist [YouTube channel]. YouTube. Retrieved August 25, 2021 from https://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLHZcztkZbL1Sl8v4vBSvNcNTQ9TOUhciq.

- OUTing the Past. (n.d.). About Outing the Past. Retrieved August 25, 2021, from https://www.outingthepast.com/about-otp.

- Peterson, A., Wahlström, M., & Wennerhag, M. (2018). Pride parades and LGBT movements: Political participation in an international comparative perspective. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315474052.

- Pidd, H. (2021, August 13). Manchester Pride to launch review after row over funding cuts. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2021/aug/13/manchester-pride-to-launch-review-after-row-over-funding-cuts.

- Sanders, S. (2021). Growing up needing the past: An activist’s reflection on the history of LGBT+ History Month in the UK. SQS – Suomen Queer-Tutkimuksen Seuran Lehti, 14(1-2), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.23980/sqs.101453

- Scott-Presland, P. (2015). Amiable warriors: A history of the Campaign for Homosexual equality. Paradise Press.

- Smith, L. (2006). Uses of heritage. Routledge.

- Stillwagon, R., & Ghaziani, A. (2019). Queer pop-ups: A cultural innovation in urban life. City & Community, 18(3), 874–895. https://doi.org/10.1111/cico.12434

- Taylor, J. (2014). Festivalizing sexuality: Discourses of ‘pride,’ counter-discourses of ‘shame.’. In A. Bennett, J. Taylor, & I. Woodward (Eds.), The festivalization of culture (pp. 27–48). Ashgate.

- Waitt, G. (2008). Urban festivals: Geographies of hype, helplessness and hope. Geography Compass, 2(2), 513–537. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-8198.2007.00089.x

- Wallace, R. (2019). Gay life and liberation, a photographic record of 1970s belfast. The Public Historian, 41(2), 144-162. https://doi.org/10.1525/tph.2019.41.2.144