?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

In this study, the gender representation of keynote speakers at conferences before and during the Covid-19 pandemic is investigated. Data is based on 162 academic conferences in tourism and related fields during the period 2019 to mid-2022. These conferences have 546 keynote speakers of which 4 per cent are representing low- or middle-income countries and slightly more than a third are women. Results based on Fractional Logit estimations reveal that the opportunity to attend conferences online during the pandemic does not significantly increase the proportion of women among keynote speakers. The proportion of female keynote speakers is unevenly distributed across the original regions for the scheduled conferences or the hosting institutions. It is highest for conferences organised in Australia/New Zealand and lowest in Asia. Conferences that span over several days have a relatively larger offer of female keynote speakers than shorter ones.

Introduction

Being selected as a keynote speaker at a conference is an important step in the academic career, something that not only expands the academic network but also paves the way for promotion, honour and recognition (Sharpe et al., Citation2020). Despite this, there is a certain lack of diversity within numerous fields, relating to for instance geography, business representations and gender, although data and literature on the two former aspects are sparse (Chen & Tham, Citation2019; Freire et al., Citation2021; Khoo-Lattimore et al., Citation2019; Larson et al., Citation2020; Le et al., Citation2021; Walters, Citation2018).

During the pandemic, many academic conferences change to a virtual format (Roos et al., Citation2020). In some cases, there are also offers of hybrid attendance (both virtual and face-to-face). Virtual conferences have several advantages over face-to-face events. They are more easily accessible to researchers independent of where they are based and how their private and work commitments are organised (Estien et al., Citation2021; Roos et al., Citation2020). These conferences are also inclusive as there is no travel required and the participation costs are commonly lower than for live meetings. This facilitates the attendance of underrepresented groups such as researchers from developing countries, students or those who are less mobile for other reasons (Estien et al., Citation2021; Fraser et al., Citation2017; van Ewijk & Hoekman, Citation2021).

The aim of this study is to analyse the gender representation of keynote speakers at conferences before and during the Covid-19 pandemic. Data is based on 162 academic conferences in tourism, hospitality and related fields taking place or being planned to appear during the period 2019 to the first six months of 2022. These conferences have 546 academic keynote speakers of which 4 per cent are representing low- or middle-income countries (World Bank definition) and slightly more than a third are women. Due to the small number of keynote speakers outside the group of high-income countries (mainly North America, United States and Oceania) the analysis focuses on the gender representation.

There is an ongoing discussion on gender balance in tourism as well as in event research (Alarcón & Cole, Citation2019; Chambers et al., Citation2017; Correia & Dolnicar, Citation2021; Dashper, Citation2018; Eger et al., Citation2021; Khoo-Lattimore et al., Citation2019; Morgan & Pritchard, Citation2019; Thomas, Citation2017; Werner, Citation2021). Edelheim et al. (Citation2018) advocate more keynote speakers with diverse backgrounds. Studies show that there are also gender imbalances in research collaborations (Nunkoo et al., Citation2020), self-citation practices (Nunkoo et al., Citation2019), and in the composition of editorial boards (Lockstone-Binney et al., Citation2021; Munar et al., Citation2015; Pritchard & Morgan, Citation2017). Walters (Citation2018) finds a statistically significant underrepresentation of women among keynote speakers and honorary committee members with a proportion of 30 per cent based on 53 international academic tourism conferences in 2017. Khoo-Lattimore et al. (Citation2019) report similar findings for the United Nations World Trade Organisation (UNWTO) conferences.

This study contributes a novel analysis of how the proportion of female keynote speakers evolves in connection with the provision of online conferences during the Covid-19 pandemic, when typical conference characteristics are controlled for (location of the organiser, duration and kind of host). The analysis also adds to the growing literature on gender, tourism studies and sustainable tourism development (Alarcón & Cole, Citation2019; Eger et al., Citation2021). Gender equality is one of the Sustainable Development Goals of the United Nations (SDG5), addressing empowerment of women, training opportunities for female community members, opportunities for women to participate in tourism and the employment of women in tourism enterprises (Rasoolimanesh et al., Citation2020). Nunkoo et al. (Citation2021) point out that the SDG 5 is one of the most studied goals in the literature on tourism sustainability.

As opposed to most other studies that commonly use descriptive statistics or bivariate tests, a multivariate model is derived and formulated to explain the representation of female keynote speakers. The approach employs a Fractional Logit model that takes into account the boundaries between zero and one for the proportion of female keynote speakers.

Conceptual background

The opportunity to hold keynote speeches at prestigious international academic events is important for several aspects of the professional development and advancement (Sharpe et al., Citation2020). Main speakers at academic conferences also serve as highly visible role models for early career researchers (Farr et al., Citation2017). Keynote speakers are considered the most important element behind the choice of an academic conference, followed by the location of the venue (Borghans et al., Citation2010). Despite the importance of the role as keynote speaker, literature indicates a lack of diversity in several academic fields, where the aspect of gender is particularly highlighted (Freire et al., Citation2021; Kalejta & Palmenberg, Citation2017; Larson et al., Citation2020).

Tourism-related conferences are no exception to the lack of diversity (Khoo-Lattimore et al., Citation2019; Munar et al., Citation2015; Walters, Citation2018). Munar et al. (Citation2015) calculate the share of women in the category ‘conference leadership’ to 24 per cent in 2013, which includes keynote speakers, invited speakers and members of expert panels based on information from the website of the Association for Tourism and Leisure Education (ATLAS). A more recent study finds that the proportion of female keynote speakers in the field is 30 per cent (Walters, Citation2018). Khoo-Lattimore et al. (Citation2019), who investigate gender parity of speakers at UNWTO conferences, report a similar proportion.

Presently, medicine and science are among the fields where the discussion of the representation of women among keynote speakers is intensive. Although there is an increase over time (Kalejta & Palmenberg, Citation2017; Larson et al., Citation2020), several studies point to a persistently low representation even in comparison with the underlying labour force (Larson et al., Citation2020). The proportions range from seven to 25 per cent (Davic et al., Citation2021; Gerull et al., Citation2020; Larson et al., Citation2020; Santosa et al., Citation2019; Sharpe et al., Citation2020; Talwar et al., Citation2021).

A somewhat higher representation (36–52 per cent) is demonstrated for invited female speakers at the Society for Personality and Social Psychology symposia as reported by Johnson et al. (Citation2017), who also note that the higher figures relate to academic rank. At ecology conferences, between 15 and 35 per cent of distinguished speakers are women, which is significantly lower than the percentage of female graduate students in the field (Farr et al., Citation2017). Few conferences have achieved parity, except for an example relating to ecology and conservation, where 47 per cent of the plenary or keynote speakers are female (Tulloch, Citation2020).

It is important to reflect upon the issue of equality versus equity. If fewer women are active within the field because of systemic factors that for different reasons inhibit their participation, reaching equality is not equivalent to reaching equity (Le et al., Citation2021). Varied representation as keynote speakers of certain groups is not necessarily systemic but may also relate to individual behaviour. Schroeder et al. (Citation2013), for instance, suggest that a lower representation of women is partly due to their higher probability to decline an invitation for a keynote speech, possibly related to several reasons including a lack of self-confidence. In an analysis of a sample of symposia on evolutionary biology, 50 per cent of the women decline an invitation to speak, compared to 26 per cent of the men (Schroeder et al., Citation2013). Invitations to hold a keynote speech at a virtual conference may be easier to accept since it does not include travel and the time commitment may be smaller. This argument is supported by the fact that the number of participants in online conferences during the Covid-19 pandemic is significantly higher than at the same conference held face-to-face (Ahn et al., Citation2021).

Few studies examine factors underlying the representations of different groups as keynote speakers at academic conferences. One exception is Freire et al. (Citation2021) who construct a diversity index based on geography, gender and business participation at artificial intelligence (AI) conferences. Their calculations reveal large imbalances of gender and geography, the latter case relating to speakers from low-income countries. Another factor highlighted in the literature is the presence of a woman on the committee that selects speakers. Casadevall and Handelsman (Citation2014) find that the proportion of women invited to speak depends on whether meetings are convened by men or women. Meetings with at least one woman on the leadership team have 18-percentage points higher proportion of invited female speakers. Kalejta and Palmenberg (Citation2017) suggest that the presence of a woman on the speaker selection panel or as colloquium chairs correlates with better parity.

Several conclusions can be reached from the available literature. With few exceptions, the representation of women as keynote speakers is low. However, research on this topic is mainly undertaken within the field of science, leaving the status in social sciences somewhat unclear. There are also numerous conference-related factors that are neglected in literature such as the location (country) of the organiser, whether it is hosted by an association and the duration of the event. These are aspects that will be controlled for in present analysis. Data on tourism and hospitality and related conferences is chosen for the analysis since this field has an underlying core of active researchers close to equity (Munar et al., Citation2015). Dashper et al. (Citation2020) conclude that tourism academia is considered female-dominated in terms of student numbers and relatively equal in terms of numerical gender representation among academic staff.

Few studies use multivariate models to examine gender imbalances for presenters at academic conferences or keynote speakers. Exceptions include Nobles et al. (Citation2021) and Arora et al. (Citation2020). The former investigates the representation of women among keynote speakers using log-binomial models where attendee characteristics and conference year are controlled for. Their estimation results reveal that women are less likely than men to give an invited symposium talk among all participants with accepted abstracts. In the latter analysis, factors associated with the proportion of female speakers at conferences are explored (without distinguishing between keynote speakers). Significant factors include the proportion of women on the planning committee and the region. Compared to the United States, the rate of female speakers is 28 per cent lower in Europe.

During the course of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020 and 2021, many countries still had international travel restrictions and bans on public events. Several organisers of online conferences report a huge increase in attendance (for instance the Tourman conference with 1000 participants).Footnote1 Literature suggests that enabling a wider range of participants and accessibility are among the main effects of virtual events, benefiting both those from developing countries and early career researchers (Estien et al., Citation2021; Fraser et al., Citation2017; Roos et al., Citation2020; van Ewijk & Hoekman, Citation2021). Scholars who are not so mobile for family or other reasons are also likely to benefit. Thus, the representation of female keynote speakers is expected to increase during the pandemic when conference-specific factors are controlled for. A major underlying reason for this is the easy access to virtual conferences. This leads to the first hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1: The proportion of female keynote speakers is significantly higher for online conferences, ceteris paribus.

Location of the planned conference or the location of the organising committee or institute is another factor that might influence the proportion or number of female keynote speakers. Gender equality varies across countries, even if the measurement is controversial, as shown in the case of the UNDP Gender Development Index (Permanyer, Citation2013). Zhang and Zhang (Citation2020) point out that gender equality in Asia is generally low also in developed countries such as South Korea and Japan, and in the Middle East it is even lower. This leads to the second hypothesis:

Hypothesis 2: The proportion of female keynote speakers is significantly related to the location of the planned conferences or its organising institution.

In principle, virtual conferences can be organised and hosted from any location. Yet, the country location of the originally planned venue or the host could still affect the proportion of female keynote speakers. A possible explanation behind this is that the gender structure in academia exhibit variation across country groups. For this reason, the country groups in which the conference is planned or organised are included in the empirical model as an important aspect of the proportion of female keynote speakers.

There are also indications that academic field of the conference is of relevance for the distribution of keynote speakers. Because of this, sub-groups of the overall field of tourism and hospitality may benefit from being treated separately. Another important aspect is whether the conference is organised by an association, these may have statutes to ensure gender diversity. The American Economic Association, for instance, recently amended the definition of diversity in its ‘Code of Professional Conduct’ to include those that have been underrepresented in the past.Footnote2 A final aspect considered is the length of the conference. When a conference is running over several days it may have more diverse topics that also attract a broader variety of participants and stakeholders including gender.

Empirical approach

Given the theoretical considerations outlined in the conceptual background, the representation of female keynote speakers is specified as follows:

(1)

(1) where i denotes the conference,

is the constant and

is the error term. Variable

reflects the proportion of female (academic) keynote speakers. Dummy variables Online and Hybrid are equal to one if the conference has the respective format and zero otherwise. The reference category for these two dummy variables is in-person conferences (which mainly occur before March 2020). Location is a set of dummy variables for the region where the conference is planned, hosted or organised with Europe as the reference category. Duration measures the length of the conference in number of days, Field is equal to one if the conference is within the main area of tourism and hospitality and zero otherwise and Association is a dummy variable indicating if the conference is hosted by an academic association.

The dependent variable, the proportion of female keynote speakers is bounded between zero and one. A standard ordinary least squares estimator is not suitable for cases where the dependent variable is restricted to the unit interval, as it may produce fitted values that exceed the lower or upper bounds (Papke & Wooldridge, Citation1996). A common method to circumvent this problem is to estimate the Fractional Logit model (Papke & Wooldridge, Citation1996). This estimation method specifies a functional form for the conditional mean of the proportion so that the predicted values appear within the interval of 0–1 and is estimated by Maximum Likelihood (Papke & Wooldridge, Citation1996). In this application, approximately one-fourth of conferences has no female keynote speaker.

Data and descriptive statistics

Information on academic conferences in tourism and related fields originates from the Association for Tourism and Leisure Educational Research (http://www.atlas-euro.org/events.aspx) and from conference announcements in TRINet (Tourism Research Information Network). In cases when information is no longer available on the conference or association website, the Wayback Machine (http://web.archive.org/) is consulted. Non-English language conferences are excluded. There are 339 conferences held or planned to be held during the period January 2019 to June 2022. Of these, 94 are cancelled or postponed and there is no information on the status for a further 14 conferences. A smaller group of academic conferences lacks keynote speakers, leaving 81 conferences organised on location (in-person), 7 in hybrid format and 74 online in the dataset.

A keynote speaker session is defined either as one labelled keynote lecture or as an invited session that all conference participants can attend without conflicting concurrent sessions (see Larson et al., Citation2020). Recognition awards and speeches as well as panel discussions are not defined as keynote sessions. Data on all academic keynote speakers, including their names, are collected from the digitally displayed conference programmes. Gender is determined by the first name of the speaker, including a double check via web search for the academic affiliation. In addition to this, information on gender is verified by the use of the software GenderChecker https://genderchecker.com/pages/search-engine.

Both the absolute number and the proportion of female keynote speakers are calculated. An association label is given to conferences that appear repeatedly over time. Kind of conference is identified through keywords (tourism, hospitality, recreation, sustainability, human geography, sport). The field ‘tourism and hospitality’ is coded 1 if tourism or hospitality is in the title of the conference. The distinction between fully or partly virtual is also made based on information from the website. Before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic all conferences were held in-person.

Conferences that do not publish their programmes are excluded from the dataset. Facts on the start date, the number of days, main topic and the location of the organiser or scheduled conference can be found on the website of each conference. Location is measured as a set of dummy variables based on the country in which the conference or organising institution is located. The 162 conferences in the dataset encompass 546 academic keynote speakers of which 204 are women (37.4 per cent). This is slightly higher than the 30 per cent earlier reported in the literature (Khoo-Lattimore et al., Citation2019; Walters, Citation2018). In comparison with other academic fields the proportion of women is substantially higher. The range in medicine varies between 7 and 25 per cent (Kalejta & Palmenberg, Citation2017; Larson et al., Citation2020; Talwar et al., Citation2021).

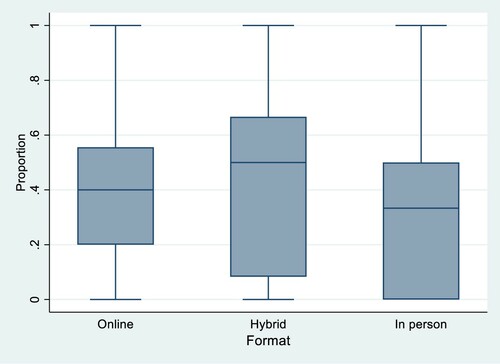

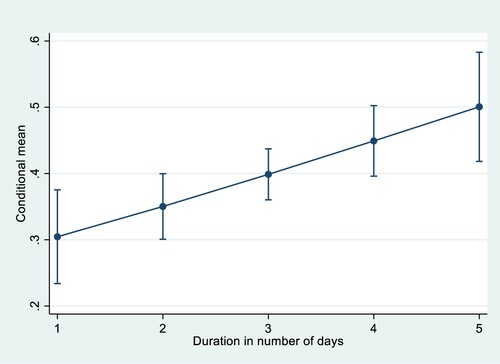

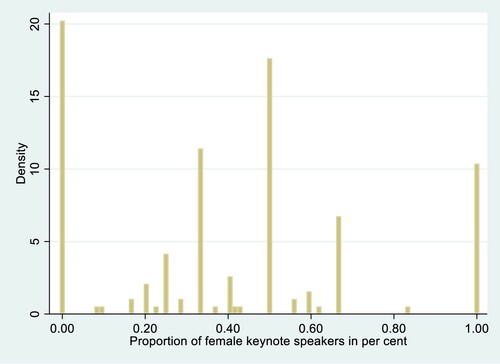

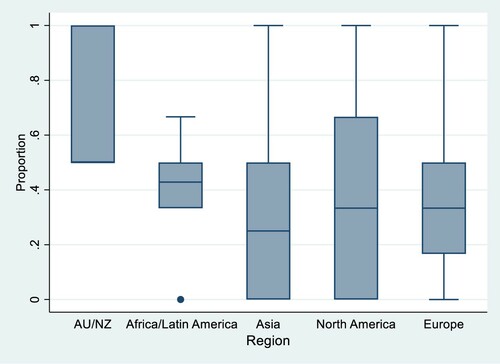

The proportion of female keynote speakers shows a high degree of variation with a clustering at the values zero and one (). This illustrates the limited boundaries of the dependent variable. Longer conferences have a larger proportion of female keynote speakers as do those hosted from Australia or New Zealand (64.3 per cent), while conferences organised from Asia show the lowest representation (26 per cent) (; ). Measured as the median, the span between host locations is slightly smaller (ranging between 25 and 50 per cent).

Figure 1. Distribution of the proportion of female keynote speakers (2019:1–2022:6). Source: Websites of conferences; own calculations.

Figure 2. Evolution of the proportion of female keynote speakers across regions. Note: The whiskers of the box show the 75th percentile (upper hinge) and the 25th percentile (lower hinge) while the line in the middle of the box represents the median. The adjacent values (end and start line of the box) are the extreme values within a range of 1.5 inter-quartiles of the nearer quartile. Points outside the lines are outliers (Stata manual). Source: Websites of conferences and; own calculations.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

The Kruskal–Wallis test indicates that there are significant differences across conferences relating to the country of the organising institution (p-value = 0.022). Duration is significant at the 10 percent level (p-value = 0.071). A Box plot shows that there is no significant difference across kinds of conferences (p-value = 0.857, , ).

Empirical results and discussion

Results of the Fractional Logit model show that the duration of the conference and the country of the organising institution are highly significant for the proportion of female keynote speakers (). This implies that the longer the conference, the higher the proportion of women (see Figure A1, Appendix, for the marginal effects). Conferences organised by hosts in Australia or New Zealand have the highest proportion of female keynote speakers. The marginal effects reveal that the proportion is 17 percentage points higher than in the reference category Europe (p-value < 0.01). In contrast, conferences in Asia have the lowest representation of female keynote speakers, 17 percentage points below the reference category Europe (p-value < 0.01). North America also exhibits a proportion of female keynote speakers that are smaller than in Europe (−8 percentage points, p-value < 0.05). Academic field, hosted by an association and format of the conference are all variables not significantly different from zero at conventional levels. Thus, the baseline estimations do not indicate that the opportunity of virtual format relates to the proportion of female keynote speakers.

Table 2. Determinants of the proportion of female keynote speakers (Fractional Logit estimations).

As a first robustness check, the country group dummy variables are replaced by the Gender Inequality Index developed by the United Nations (UNDP, Citation2020). The purpose is to investigate whether systemic patterns better explain gender representation at academic conferences than country group dummy variables. There is a clear variation in the index across countries, where some northern and north-western European areas are the best performers. Estimation results reveal that the gender inequality index is not significant at conventional levels (p = 0.11). In a second robustness check the online and hybrid format variables are merged into one. This composite indicator is not significant at conventional levels (p-value = 0.42). A final robustness check investigates whether the share of female keynote speakers changes in the mature phase of the pandemic, with better planning opportunities for different formats. Unreported results show that the interaction term between the dummy variable for online conferences and the time dummy variable from 2021 onwards is not significantly different from zero (p-value = 0.840).

Overall, the results of the share equation model establish that location and duration are significant determinants of the proportion of female keynote speakers. However, the format of the conference is not significant. Thus, while the second hypothesis cannot be rejected, the same is not valid for the first.

Another finding of the study is that women appear as keynote speakers to a lesser degree (37 per cent) than their actual representation in the academic workforce, which is close to 50 per cent (Munar et al., Citation2015). This is striking and could indicate that there is a social order in certain academic societies that overrules other aspects such as equal gender representation (Walters, Citation2018). Gender representation has many faces in academic life, concerning not only keynote speakers but also other important aspects such as salary, promotion, scholarly recognition and editorial board memberships (Kalejta & Palmenberg, Citation2017). The representation of female keynote speakers resembles women with higher positions in tourism research in general. Munar et al. (Citation2015) examine the gender profile of the editorial boards of 189 tourism and hospitality journals and conclude that the overwhelming majority (70 per cent) of these positions are held by men. Similar results are found by Pritchard and Morgan (Citation2017) where 77 per cent of 677 editorial positions in the top 12 ranked tourism journals are held by men. More recently, Lockstone-Binney et al. (Citation2021) show that the proportion of women among editorial board members in tourism journals is 31 per cent.

Conclusions

In this study, the gender representation of keynote speakers at conferences in the field of tourism and hospitality before and during the Covid-19 pandemic is investigated. Data on 162 conferences held or planned to be held from 2019 to June 2022, including 546 keynote speakers in tourism and related fields, are used for the analysis. The proportion of female keynote speakers is 37 per cent and does not increase markedly during the pandemic, even if virtual conferences might facilitate participation.

Estimations of a Fractional Logit model, where the bounded nature of the dependent variable is taken into account, reveal that location of the conference host and the duration of the event are significant determinants of the proportion of female keynote speakers, although the format is not. Thus, the results imply that virtual conferences in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic do not (yet) facilitate increased diversity of gender. In addition, results show that the proportion of female keynote speakers is highest for conferences held (in-person or virtually) in Australia/New Zealand and lowest in Asia. Conferences with a longer duration have a larger representation of female speakers.

This research contributes to existing knowledge on gender representation among keynote speakers. Previous research mainly focuses on the role of the gender composition of the organising committee or on how these changes over time-based on descriptive statistics. Present modelling includes additional conference characteristics (location, duration, type) that may influence gender representation.

Somewhat surprisingly, the facilitated participation through the online format, does not relate to the proportion of female keynote speakers. Possibly, this means that changes following the outbreak of a pandemic are not enough to eliminate existing social orders, for instance. Although they are not significantly related to gender in this study, associations may be crucial for increasing diversity in the future. Gender balance will likely attract more submissions and contributions from women. Associations should monitor and ensure gender equality among invited speakers, organisation committees and boards. Special attention could be put on speakers in regions where the proportion of female keynote speakers is significantly below average.

There are some limitations to this study. One is that information on the total number of participants in each conference is not available. It is equally difficult to gather information on the gender representation of the academic selection committee. Another limitation is that this study only focuses on the representation of one specific group. Initially, the idea was to cover several aspects of diversity, although data limitations did not allow that. It should also be noted that the sample size of 162 academic conferences and 546 keynote speakers does not allow for a detailed examination of cross-national differences in the gender representation. In addition, the time period analysed is quite short, three and a half years, thus it may be too early to detect a significant change in the proportion of keynote speakers in the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Future research should systematically monitor gender representation of keynote speakers and their causes. In addition, new conference-specific factors such as information on the gender representation of the selection committees should be added to the specification. A larger sample with other areas of social science (economics, business and management) is also required to estimate determinants of representation of female keynote speakers before and during the Covid-19 pandemic and to conduct a comparison between face-to-face and online conferences.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank the participants of the virtual Association for Tourism in Higher Education (ATHE) 2021 conference for helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Source: https://www.tourman.gr; accessed 2021, October 22.

2 Source: https://www.aeaweb.org/about-aea/code-of-conduct, accessed, 2021, October 22.

References

- Ahn, S. J. G., Levy, L., Eden, A., Won, A. S., MacIntyre, B., & Johnsen, K. (2021). IEEEVR2020: Exploring the first steps Toward standalone virtual conferences. Frontiers in Virtual Reality, 2(28). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/frvir.2021.648575

- Alarcón, D. M., & Cole, S. (2019). No sustainability for tourism without gender equality. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 903–919. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1588283

- Arora, A., Kaur, Y., Dossa, F., Nisenbaum, R., Little, D., & Baxter, N. N. (2020). Proportion of female speakers at academic medical conferences across multiple specialties and regions. JAMA Network Open, 3(9), e2018127–e2018127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.18127

- Borghans, L., Romans, M., & Sauermann, J. (2010). What makes a good conference? Analysing the preferences of labour economists. Labour Economics, 17(5), 868–874. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.labeco.2010.04.009

- Casadevall, A., & Handelsman, J. (2014). The presence of female conveners correlates with a higher proportion of female speakers at scientific symposia. MBio, 5(1), e00846–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1128/mBio.00846-13

- Chambers, D., Munar, A. M., Khoo-Lattimore, C., & Biran, A. (2017). Interrogating gender and the tourism academy through epistemological lens. Anatolia, 28(4), 501–513. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2017.1370775

- Chen, S. H., & Tham, A. (2019). Trends in tourism-related academic conferences: An examination of host locations, themes, gender representation, and costs. Event Management, 23(4-5), 733–751. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3727/152599519X15506259855670

- Correia, A., & Dolnicar, S. (2021). Women's voices in tourism research: Contributions to knowledge and letters to future generations. Brisbane: The University of Queensland. Retrieved October 22, 2021, from https://uq.pressbooks.pub/tourismknowledge. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14264/817f87d.

- Dashper, K. (2018). Confident, focused and connected: The importance of mentoring for women’s career development in the events industry. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 10(2), 134–150. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1403162

- Dashper, K., Turner, J., & Wengel, Y. (2020). Gendering knowledge in tourism: Gender (in) equality initiatives in the tourism academy. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1834566

- Davic, A., Carey, E., Lambert, E., Luckingham, T., Mongiello, N., Peralta, R., … Maloney, L. M. (2021). Disparity in gender representation of speakers at national emergency medical services conferences: A current assessment and proposed path forward. Prehospital and Disaster Medicine, 36(4), 445–449. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S1049023X21000571

- Edelheim, J. R., Thomas, K., Åberg, K. G., & Phi, G. (2018). What do conferences do? What is academics’ intangible return on investment (ROI) from attending an academic tourism conference? Journal of Teaching in Travel & Tourism, 18(1), 94–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15313220.2017.1407517

- Eger, C., Munar, A. M., & Hsu, C. (2021). Gender and tourism sustainability. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.1963975

- Estien, C. O., Myron, E. B., Oldfield, C. A., & Alwin, A. (2021). Virtual scientific conferences: Benefits and how to support underrepresented students. The Bulletin of the Ecological Society of America, 102(2), e01859. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/bes2.1859

- Farr, C. M., Bombaci, S. P., Gallo, T., Mangan, A. M., Riedl, H. L., Stinson, L. T., Wilkins, K., Bennett, D. E., Nogeire-McRae, T., & Pejchar, L. (2017). Addressing the gender gap in distinguished speakers at professional ecology conferences. BioScience, 67(5), 464–468. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix013

- Fraser, H., Soanes, K., Jones, S. A., Jones, C. S., & Malishev, M. (2017). The value of virtual conferencing for ecology and conservation. Conservation Biology, 31(3), 540–546. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/cobi.12837

- Freire, A., Porcaro, L., & Gómez, E. (2021). Measuring diversity of artificial intelligence conferences. In: Proceedings of 2nd Workshop on Diversity in Artificial Intelligence (AIDBEI), PMLR 142:39-50.

- Gerull, K. M., Wahba, B. M., Goldin, L. M., McAllister, J., Wright, A., Cochran, A., & Salles, A. (2020). Representation of women in speaking roles at surgical conferences. The American Journal of Surgery, 220(1), 20–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2019.09.004

- Johnson, C. S., Smith, P. K., & Wang, C. (2017). Sage on the stage: Women’s representation at an academic conference. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 43(4), 493–507. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167216688213

- Kalejta, R. F., & Palmenberg, A. C. (2017). Gender parity trends for invited speakers at four prominent virology conference series. Journal of Virology, 91(16), e00739–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1128/JVI.00739-17

- Khoo-Lattimore, C., Yang, C., & Je, S. (2019). Assessing gender representation in knowledge production: A critical analysis of UNWTO's planned events. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 27(7), 920–938. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2019.1566347

- Larson, A. R., Sharkey, K. M., Poorman, J. A., Kan, C. K., Moeschler, S. M., Chandrabose, R., Marquez, C. M., Dodge, D. G., Silver, J. K., & Nazarian, R. M. (2020). Representation of women among invited speakers at medical specialty conferences. Journal of Women's Health, 29(4), 550–560. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.7723

- Le, T. T., Himmelstein, D. S., Hippen, A. A., Gazzara, M. R., & Greene, C. S. (2021). Analysis of scientific society honors reveals disparities. Cell Systems, 12(9), 900–906. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cels.2021.07.007

- Lockstone-Binney, L., Ong, F., & Mair, J. (2021). Examining the interlocking of tourism editorial boards. Tourism Management Perspectives, 38, 1–10. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2021.100829.

- Morgan, N., & Pritchard, A. (2019). Gender matters in hospitality (invited paper for ‘luminaries’ special issue of international journal of hospitality management). International Journal of Hospitality Management, 76, 38–44. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhm.2018.06.008

- Munar, A. M., Budeanu, A., Caton, K., & Chambers, D. (2015). The gender gap in the tourism academy: Statistics and indicators of gender equality. Retrieved December 2021, from https://research-api.cbs.dk/ws/portalfiles/portal/45082310/ana_maria_munar_the_gender_gap.pdf

- Nobles, C. J., Lu, Y. L., Andriessen, V. C., Bevan, S. S., Radoc, J. G., Alkhalaf, Z., & Schisterman, E. F. (2021). A data-based approach to evaluating representation by gender and affiliation in Key presentation formats at the annual meeting of the Society for epidemiologic research. American Journal of Epidemiology, 190(9), 1710–1720. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwab080

- Nunkoo, R., Hall, C. M., Rughoobur-Seetah, S., & Teeroovengadum, V. (2019). Citation practices in tourism research: Toward a gender conscientious engagement. Annals of Tourism Research, 79, 1–13. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2019.102755

- Nunkoo, R., Sharma, A., Rana, N. P., Dwivedi, Y. K., & Sunnassee, V. A. (2021). Advancing sustainable development goals through interdisciplinarity in sustainable tourism research. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2021.2004416

- Nunkoo, R., Thelwall, M., Ladsawut, J., & Goolaup, S. (2020). Three decades of tourism scholarship: Gender, collaboration and research methods. Tourism Management, 78, 1–11. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.104056

- Papke, L. E., & Wooldridge, J. M. (1996). Econometric methods for fractional response variables with an application to 401 (k) plan participation rates. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 11(6), 619–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1255(199611)11:6<619::AID-JAE418 > 3.0.CO;2-1

- Permanyer, I. (2013). A critical assessment of the UNDP’s gender inequality index. Feminist Economics, 19(2), 1–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2013.769687

- Pritchard, A., & Morgan, N. (2017). Tourism’s lost leaders: Analysing gender and performance. Annals of Tourism Research, 63, 34–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2016.12.011

- Rasoolimanesh, S. M., Ramakrishna, S., Hall, C. M., Esfandiar, K., & Seyfi, S. (2020). A systematic scoping review of sustainable tourism indicators in relation to the sustainable development goals. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1775621

- Roos, G., Oláh, J., Ingle, R., Kobayashi, R., & Feldt, M. (2020). Online conferences–towards a new (virtual) reality. Computational and Theoretical Chemistry, 1189, 1–6. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comptc.2020.112975

- Santosa, K. B., Larson, E. L., Vannucci, B., Lapidus, J. B., Gast, K. M., Sears, E. D., Waljee, J. F., Suiter, A. M., Sarli, C. C., Mackinnon, S. E., & Snyder-Warwick, A. K. (2019). Gender imbalance at academic plastic surgery meetings. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 143(6), 1798. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0000000000005672

- Schroeder, J., Dugdale, H. L., Radersma, R., Hinsch, M., Buehler, D. M., Saul, J., Porter, L., Liker, A., Cauwer, I., Johnson, P. J., Santure, A. W., Griffin, A. S., Bolund, E., Ross, L., Webb, T. J., Feulner, P. G. D., Winney, I., Szulkin, M., Komdeur, J., … Horrocks, N. P. (2013). Fewer invited talks by women in evolutionary biology symposia. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 26(9), 2063–2069. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jeb.12198

- Sharpe, E. E., Moeschler, S. M., O'Brien, E. K., Oxentenko, A. S., & Hayes, S. N. (2020). Representation of women among invited speakers for grand rounds. Journal of Women's Health, 29(10), 1268–1272. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2019.8011

- Talwar, R., Bernstein, A., Jones, A., Crook, J., Apolo, A. B., Taylor, J. M., Burke, L. M., Plimack, E. R., Porten, S. P., Greene, K. L., Psutka, S. P., & Smith, A. B. (2021). Assessing contemporary trends in female speakership within urologic oncology. Urology, 150, 41–46. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2020.08.006

- Thomas, R. (2017). A remarkable absence of women: A comment on the formation of the new events industry board. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 9(2), 201–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2016.1208189

- Tulloch, A. I. (2020). Improving sex and gender identity equity and inclusion at conservation and ecology conferences. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 4(10), 1311–1320. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-020-1255-x

- UNDP. (2020). Human development report, technical note 1. Human Development Index. http://hdr.undp.org/sites/default/files/hdr2020_technical_notes.pdf

- van Ewijk, S., & Hoekman, P. (2021). Emission reduction potentials for academic conference travel. Journal of Industrial Ecology, 25(3), 778–788. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jiec.13079

- Walters, T. (2018). Gender equality in academic tourism, hospitality, leisure and events conferences. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 10(1), 17–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2018.1403165

- Werner, K. (2021). The future is female, the future is diverse: Perceptions of young female talents on their future in the (German) event industry. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, early online . https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2021.1975289.

- Zhang, J., & Zhang, Y. (2020). Tourism and gender equality: An Asian perspective. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 103067. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.103067