ABSTRACT

Creative tourism has recently emerged as an important area of tourism development, particularly in the Global North. In the Global South, studies of the profile of creative tourists and their motives for partaking in creative tourism are limited. This paper investigates creative tourism demand among South African millennials, analysing what motivates their participation and developing a descriptive consumer profile. CHAID analysis was used for segmentation, revealing a group with a high participation intention and a second group with a low probability of creative tourism participation. Creative tourism intentions were linked to knowledge acquisition, skills and escape motivations, and demographic characteristics including relationship status and gender. Respondents were more likely to participate in domestic rather than international creative tourism, indicating the potential for creative tourism development in South Africa. The findings could help managers and policymakers meet the needs of creative tourists, addressing shortfalls in product development, experience design and marketing.

Introduction

The proliferation of mass tourism has led to many tourists engaging in creative tourism in the search for more authentic experiences that avoid the ‘serial reproduction of culture’ (Richards & Wilson, Citation2006, p. 1210). Tourism researchers had observed this change, leading Richards (Citation2011, p. 1225) to note the ‘creative turn’ during the 1990s, when tourism researchers started exploring the interconnection between tourism and creativity as a reaction to mass cultural tourism. Carvalho et al. (Citation2016, p. 1075) described this shift of interest away from cultural tourism and towards creative tourism as a ‘paradigm shift’ in the global tourism landscape. Indeed, creative tourism is seen to be ‘cool’ and offers the opportunity to engage with different facets of both heritage and contemporary culture, including the creation of visual arts, cooking, fashion design, creative writing and many other activities (Richards, Citation2011, p. 1225; Richards & Marques, Citation2012; Kostopoulou, Citation2013). The creative turn also hints at a new profile of tourists who can be drawn on for economic development opportunities in locations that may not have tourist products considered iconic by the mass tourism market (Duxbury & Richards, Citation2019).

Most research on creative tourism has focused on Eurasia (Richards, Citation2018), and studies of the profile and motivations of creative tourists remain limited in their geographical scope (see Ali et al., Citation2016; Chang et al., Citation2014). There is, however, reason to suppose that creative tourism has considerable development potential in emerging economies. Creative tourism is argued to diversify and preserve cultures, contributing to employment and developing creative industries (Marujo et al., Citation2019a), and requires less investment in tangible structures (Blapp & Mitas, Citation2018). South Africa is an emerging country seen as diverse and culturally rich, which has potential to develop its intangible heritage for tourism. But because of the gaps in its current offerings and widely held stereotypes that hinder the promotion of its indigenous cultures at an international level, its potential to develop its creative know-how, and local heritage, is inadequate (Bessone & Spencer, Citation2017).

South Africa's National Department of Tourism believes that the heritage and cultural resources of South Africa have development potential, and they highlight the need for targeted and authentic offering (Jessa, Citation2015). Internationally, the interest in creative tourism is growing, and many tourists are looking for a more engaging experience of creative industries and the local culture (Bessone & Spencer, Citation2017). Therefore, understanding the role of place, profile, and motivation in creative tourism is vital to South Africa's tourism industry.

Tan et al. (Citation2013) argue that it is easier to establish a supply of creative tourism products than it is to construct demand for it. Thus, we argue that there is a need first to understand the motivation for participating in creative tourism and then to establish a profile of potential creative tourists from the general populace that could indicate the level of supply needed (Hung et al., Citation2016). Studies on developing creative tourism experiences have mainly taken a supply-side view, with limited focus on the demand side (Tan et al., Citation2014).

One group of potential creative tourists worthy of investigation are millennials (individuals born between 1980–1996), who are of particular interest to the global tourism economy. Millennials value a work/life balance, have diverse needs, are keen on connectivity in terms of technology, show interest in social responsibility, and are ‘avid travellers’ (Richards & Morrill, Citation2020, p. 127). In South Africa, millennials are a unique cohort, given that they are the first generation that had not grown up (entirely) under apartheid (1948–1994). They now form one of the largest groups in the economically active population, and they are now becoming the parents of the so-called Generation Z. They are thus experiencing levels of political, social and economic representation that previous generations had not. Therefore, constructing the profile, and understanding the needs and motivations of potential millennial travellers, could go some way to realise the consumption potential of creative tourism products in South Africa.

The overall objective of the paper is, therefore, to investigate creative tourism demand among South African millennials. To do this, the paper investigates the motivations of South African millennials interested in engaging in creative tourism activities, builds a profile of potential millennial creative tourists based on their motivations and demographic characteristics and ascertains whether the profiles of potential international and domestic South African millennial creative tourists differ from each other.

The structure of the paper unfolds as follows. A literature review considers what creative tourism is, who creative tourists are, and notes on demand for creative tourism in South Africa. After this, the methods applied are described, and the results of the analysis are presented. The paper is then completed with a discussion of the results, the theoretical and practical implications, and the conclusion.

What is creative tourism?

Creative tourism is defined by Duxbury et al. (Citation2019, p. 295) as ‘sustainable small-scale tourism that provides a genuine visitor experience by combining an immersion in local culture with a learning and creative process.’ Cultural and creative tourists can engage in similar activities during a holiday, but as Remoaldo et al. (Citation2020a) demonstrate, creative tourists are particularly concerned with developing their knowledge and creative skills, to be involved in co-creative activities and to interact with the local community. Cultural tourists in general tend to engage in more passive activities, such as sightseeing or museum visits (Richards & Wilson, Citation2006). Creative tourists are a ‘heterogeneous group of co-producers … ’ (Tan et al., Citation2014, p. 248) who share the critical importance of co-production and the motivation to search for authenticity and attain enhanced cultural capital (Carvalho et al., Citation2016). Richards and van der Ark (Citation2013) found that younger tourists tended to be more interested in contemporary art and architecture and in engaging in creativity, while mature tourists visited monuments and museums. In respect of gender, Remoaldo et al. (Citation2020b, p. 13) found that women were much more optimistic about the ‘intention’ and ‘overall satisfaction’ of creative tourism activities and were keener to take part in creative activities related to culture and heritage.

In many cases, tourists and destination residents are unaware of what creative tourism entails (Remoaldo, Citation2022). This lack of awareness could explain why a vast array of creative activities could be positioned under the banner of ‘creative tourism’, which makes profile development difficult (Remoaldo et al., Citation2020a). The profile of creative tourists also depends on the location of the tourism product (rural or urban), and the locality also influences the level of participation (Li & Kovacs, Citation2022; Markwick, Citation2018; Richards, Citation2020). Invariably, the diverse motivations of creative tourists will imply diverse creative experiences, even at the same destination (Chen & Chou, Citation2019).

Thus, establishing a profile of creative tourists depends on a multitude of factors, such as the many forms of creativity and the interchange between ‘organisations, cultural elements/assets, technologies, spaces/territories, customer profiles, and business strategies for generating tourism creative services’ (Marujo et al., Citation2019a, p. 692). To gain a greater understanding of these different factors, the following section considers the key profiles of creative tourists in the literature. As Marujo et al. (Citation2019b) claim, understanding the profile of creative tourists can assist stakeholders in developing destinations suited to market needs.

Who is the creative tourist?

Because of the relatively recent emergence of creative tourism as a field of study (Richards & Marques, Citation2012), the number of studies and profiles of creative tourists developed is lower than for cultural tourists – although the literature is growing. Raymond (Citation2003) developed a segmented profile of creative tourists in New Zealand as ‘the baby boomers and newly retired’, ‘those under 30, often students, backpackers, perhaps visiting New Zealand on a ‘gap year’’ and ‘New Zealanders themselves of all ages who are interested to learn more about different aspects of their country’s culture’. Tan et al. (Citation2014, p. 248) developed five distinct groups of creative tourists: ‘novelty seekers’, ‘knowledge and skills learners’, ‘those who are aware of their travel partner’s growth’, and ‘those who are aware of green issues’ and ‘relax and leisure types’. Carvalho et al. (Citation2016, p. 1076), in their study of the Algarve in Portugal, describe a creative tourist as an individual who comes from a ‘high social class’, ‘has achieved minimum one tertiary qualification’ and is ‘highly motivated’ to take part in learning activities based on the endemic culture of the destination. Creative tourists are often employed in the creative industries or are academics. A recent study of creative tourist profiles by Remoaldo et al. (Citation2020a, p. 2) describes creative tourists as an inter-generational cohort in search of ‘authenticity, exclusivity, improving skills and desiring contact with the local community’, with segments developed around three aspects: ‘novelty seekers’, ‘knowledge and skills learners’ and ‘leisure and creative seekers’. In Hong Kong, Chan and Liu (Citation2022, p. 223) found that tourists could be categorised experientially as those seeking ‘esthetics’, ‘involvement’, and ‘education’. The diversity of creative tourist profiles makes generalised segmentation challenging, given the overlapping characteristics of many creative tourist segments. Arguably there is a need for a broader geographical understanding of creative tourist profiles before a more concrete framing of the creative tourist can be established.

Creative tourism demand among South African millennials

The influence of millennials on global tourism has become a popular topic of investigation (Monaco, Citation2018). Indeed, numerous studies have shown that millennials can transform the tourism industry because of their desire for authentic experiences, altruistic intentions, and use of Web 2.0 technologies (Días et al., Citation2022; Du et al., Citation2020; Veiga et al., Citation2017). Their persistent connectivity allows millennials to share their touristic experiences on a peer-to-peer basis on social media, thus creating an instant and widespread marketing platform for destinations, stimulating the rapid growth of destinations (Liu et al., Citation2019). This rapid growth underlines the importance of intimately understanding the profile and motivations of millennial tourists to benefit tourist businesses (Cavagnaro et al., Citation2018). However, tourists’ ‘revolving needs, expectations and requirements’ will change over time, requiring ongoing re-assessment to optimise future business functionality (Sigala & Leslie, Citation2005, p. 174; Suhartanto et al., Citation2020, p. 870).

Research on creative tourism in South Africa is limited, albeit growing. Topics covered in creative tourism research in South Africa specifically focus on creative tourism as an economic development tool in select small towns, cities and townships (Booyens & Rogerson, Citation2019; Drummond et al., Citation2021).

However, no previous studies have focused on South African tourists’ motivations to participate in creative tourism. Thus far, the only investigation that has attempted to establish a profile of creative tourists is that by Wessels and Douglas (Citation2020). They found that international females with postgraduate degrees regarded creative tourism activities as more important than other tourists. Understanding the profile and motivations of millennial tourists in South Africa is undoubtedly relevant because they make-up over a quarter of the country’s population (StatsSA, Citation2019) and present significant opportunities for domestic and international markets in creative tourism.

A key point is that previous research on profiles and motivations of creative tourists is based primarily on participants in creative tourism rather than the general population, making it difficult to assess overall demand. This paper attempts to assess creative tourism demand among South African millennials by investigating their motivations for engaging in creative tourism activities and by building a profile of potential creative tourists based on their motivations and demographic characteristics. Furthermore, we attempt to ascertain whether the profiles of potential international and domestic creative tourists differ from each other.

Methods

Data were collected by a South African research company using an online panel of 40,000 individuals during September 2020. The company uses online and offline methods to attract panellists (mail banner advertisements, media, print and advertising), thereby maximising the demographic diversity of the panel. Respondent recruitment can include specific requirements, for example, population group, age, education level and relationship status. In our study, panel members aged between 24 and 39 with a tertiary qualification (or studying for a tertiary qualification) were requested to participate by completing an online questionnaire hosted on the company’s server. Using a panel sample has become more common in tourism studies because of its affordability of data collection and the efficiency with which the sample can be reached (Suess et al., Citation2020). According to Woosnam et al. (Citation2021), using an online panel as a sampling approach is an acceptable and reliable data collection method when the inclusion coverage is comprehensive (for example, making use of a national panel) and when well-detailed criteria are used (Vehovar et al., Citation2016).

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. First, the respondents’ demographic characteristics were measured, including age, gender, relationship status, whether respondents had children, population group, geographical location and educational level. Before continuing with the rest of the questionnaire, respondents were sensitised to the definition of creative tourism, using Richards and Raymond's (Citation2000, p. 18) definition: ‘tourism which offers tourists the opportunity to develop their creative potential through active participation in courses and learning experiences which are characteristic of the destination where they are undertaken’. To familiarise respondents further with the definition, they were given a list of typical creative tourism experiences. Then, respondents were asked, ‘how likely are you to engage in creative tourism activities while at destinations in South Africa/how likely are you to engage in creative tourism activities while at other international destinations?’ on a five-point Likert scale ranging from ‘highly unlikely’ (1) to ‘highly likely’ (5). Last, to measure their motivations for participating in creative tourism, a new scale was developed consisting of 22 items (see Table 2 for the items) derived from previous studies. The first 12 items in the scale (see Table 2) were taken from Ali et al. (Citation2016) and the last ten items from Tan et al. (Citation2014). Since both these studies used actual creative tourism experiences and motivations, the items used in this study were adapted to reflect potential motivations for participating in creative tourism. The questions were answered using a five-point Likert – scale in which 1 = ‘strongly disagree’ and 5 = ‘strongly agree’.

SPSS Statistics 21 software was used to analyse the data. Frequency distributions were used to characterise millennials regarding their socio-demographics and the likelihood of engaging in domestic or international creative tourism activities. An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was used to identify the dimensions of participants’ motivation to engage in creative tourism activities. The potential creative tourists were segmented to ascertain whether the profiles differed for domestic and international creative tourism activities, using chi-square automatic interaction detection (CHAID). This classification model builds structures based on associations between independent (also known as predictor) and dependent variables (Rokach & Maimon, Citation2008). McCarty and Hastak (Citation2007) argue that CHAID is a more sophisticated market segmentation technique than other multivariate analysis methods. CHAID allows for the identification of the variables that significantly differentiate the segments, but it also indicates their importance in the segmentation process. According to Pitombo et al. (Citation2017), the outcome of a CHAID is a diagram that looks like a tree with a root node that is divided into branches, causing homogeneous terminal leaf nodes that cannot be divided further. The terminal nodes signify distinct segments. The CHAID technique has been used successfully and has been confirmed as a valuable method in advancing the segmentation methodology (Chen, Citation2003; van Middlekoop et al., Citation2003), while Hsu and Kang (Citation2007) and Ceylan et al. (Citation2020) contend that CHAID analysis is still an underutilised and underexplored method in tourism studies.

Results

Demographic characteristics

In total, 1,530 completed questionnaires were collected. Most of the respondents were Black Africans (66.5%), and almost an equal number of males (48.8%) and females (51.2%). Respondents with a tertiary certificate or diploma qualification accounted for 57% of the sample (). Respondents predominantly residing in the Gauteng (44.6%) province were single (64.8%), and almost two-thirds of the respondents had children (62.1%) (). The average age of the respondents was 29 years.

Table 1. Demographic profile of respondents and their likelihood of engaging in creative tourism activities.

shows that respondents were more likely to engage in domestic creative tourism activities than in international creative tourism activities. When comparing our sample with the general profile of South African millennials, 50.7% of the South African millennial population are male, and 49.3% are female. Among three generations (Gen X, Millennials and Born Free Millennials, a specific group in South Africa born after the fall of apartheid in 1994), millennials are the most highly educated (StatsSA, Citation2018). According to Statistics South Africa's Mid-Year Population Report, there are approximately 15.6 million millennials in South Africa, constituting 26.6% of the population (StatsSA, Citation2019).

Validity and reliability assessment

Because the motivation scale used in our study was developed from two previous scales (Ali et al., Citation2016; Tan et al., Citation2014), it was subjected to EFA using principal axis factoring with Promax rotation. The results of the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) measure of sample adequacy (.946) and Bartlett’s test of sphericity (18695.737, p < 0.001) showed that the data was suitable for EFA (Field, Citation2013, pp. 684–686; Pallant, Citation2013, p. 199). Extracted factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 were retained for further analysis (Pallant, Citation2013, p. 191). Four factors were extracted based on the eigenvalue (>1) criterion that together explained 63.5% of the total variance in the data. After inspecting the items that loaded onto each factor, the four factors were labelled as ‘to gain knowledge and skills’, ‘unique and once-in-a-lifetime experience’, ‘to earn respect’, and ‘escape’. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient values were used to evaluate the internal consistency (reliability) of the motivation factors; they surpassed the value of 0.7, thus signifying that the scale used to measure creative tourism motivations was reliable (Hair et al., Citation2014, p. 166). These four factors mirror those found by Ali et al. (Citation2016). The escape and respect items in their study were loaded onto one factor, labelled ‘escape and recognition’. Our unique and once-in-a-lifetime factor is like their ‘unique involvement’ factor, and our knowledge and skills match their ‘learning’ factor. From the mean scores in , it is clear that the factor with which most respondents agreed was ‘unique and once-in-a-lifetime experience’, followed by ‘to gain knowledge and skills’.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis.

CHAID results for South African creative tourism activities

For both the CHAID analyses, the dependent variable ‘likelihood of engaging in creative tourism activities in South Africa/likelihood of engaging in international creative tourism activities’ was categorised into two groups: group 1 respondents, who were neutral, unlikely, or highly unlikely to engage in creative tourism; and group 2 respondents, who were likely or highly likely to engage in creative tourism in South Africa/internationally. The independent variables included the socio-demographic items shown in (except for age – since all respondents are millennials) and the creative tourism motivation factors identified in the EFA.

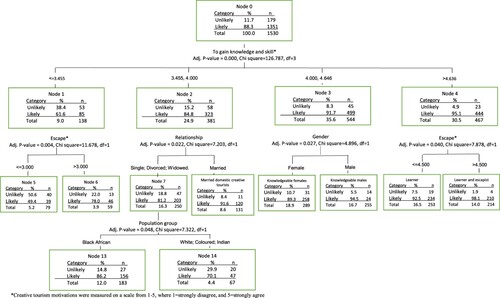

The resultant model has four levels and 14 nodes for South African creative tourism activities. Nine were terminal nodes (5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 14) with group sizes ranging from 59 to 289 (see ). The final tree had an estimated risk of 0.116, which for categorical dependent variables is the proportion of cases incorrectly classified with a standard error of 0.008. Thus, the overall percentage of correct classification was 88.4%, which is considered good (Agapito et al., Citation2011). The best predictor of whether respondents will engage in domestic creative tourism activities was the ‘to gain knowledge and skills’ motivational factor (p-value = 0.000 and chi-square = 126.787).

Figure 1. CHAID analysis for millennial South African consumers likely to participate in domestic creative tourism activities. *Creative tourism motivations were measured on a scale from 1–5, where 1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree.

Participants with a score of < = 3.455 for the factor ‘to gain knowledge and skills’ were included in node 1 of the left branch. This node was further split by the ‘escape’ factor, which resulted in node 5 (with a score of < = 3.0) and node 6 (those that had a score >3.0). No further splits were generated from nodes 5 and 6.

Node 2, the second branch from the left, included participants who scored between 3.455 and 4.0 for the factor ‘to gain knowledge and skills’. Node 2 was split by the relationship variable, resulting in nodes 7 (single and divorced individuals) and 8 (Married and other couples). Node 7 was further split by population group into nodes 13 and 14. Node 13 included Black African respondents. In contrast, node 14 included Coloured (people of mixed-race origin), Indian, and White respondents. Nodes 8, 13 and 14 were terminal. Node 8 (n = 131, 91.6% indicated that they were likely to engage in South African creative tourism activities) made up 8.3% of the total sample and was a terminal node.

Node 3, the second branch from the right, included participants who scored between 4.0 and 4.636 for the factor ‘to gain knowledge and skills’ (n = 544, 91.7% likelihood to engage in South African creative tourism activities). This node was split by the gender variable, which resulted in nodes 9 (females: n = 289; 89.3% likelihood to engage in South African creative tourism activities) and 10 (males: n = 255, 94.5% likelihood to engage in South African creative tourism activities). Males who agreed that knowledge and skills are a motivator were slightly more likely to engage in domestic creative tourism activities than females. Both nodes were terminal. Node 9 comprised 18.9% of the total sample, and node 10, 16.7% of the total sample.

Node 4, the right branch, consisted of participants who had a score of >4.636 for the factor ‘to gain knowledge and skills’ (n = 467; 95.1% likelihood to engage in South African creative tourism activities). This node was further split by the ‘escape’ factor, which produced two terminal nodes, nodes 11 and 12. Node 11 (n = 253; 92.5% likelihood to engage in South African creative tourism activities) included those with a score of < = 4.5, and node 12 (n = 214; 98.1% likelihood to engage in South African creative tourism activities) included those with a score of >4.5.

The sample proportion of respondents likely to engage in domestic creative tourism activities was 88.3%, as indicated in node 0. Five final segments (nodes 8, 9, 10, 11, and 12) showed higher proportions, depicted at the end of the next section. Based on their characteristics, node 8 was labelled ‘Married domestic creative tourists’, node 9 ‘Knowledgeable females’, node 10 ‘Knowledgeable males’, node 11 ‘Learner’, and node 12 ‘Learner and escapist’.

shows the gain index for each of these segments. These segments represent an above-average likelihood of engaging in domestic creative tourism activities. For instance, the gain index for the ‘Learner and escapist’ segment is 111.1%, meaning that the likelihood of this group participating in domestic creative tourism activities is 1.11 times greater than the average.

Table 3. Gain index for South African creative tourism activities.

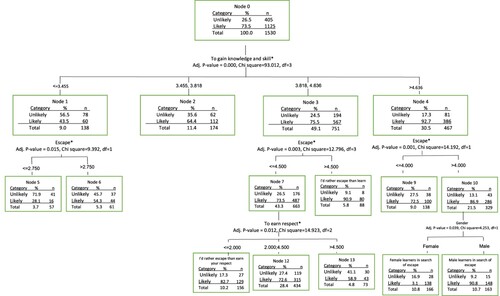

CHAID results for international creative tourism activities

Four variables significantly differentiated the segments in the following order of importance: to gain knowledge and skills, escape, to earn respect, and gender (see ). The results indicated an excellent predictive power since the overall percentage of correctly classified cases was 75.2%. The final tree had an estimated risk of 0.248, which for categorical dependent variables is the proportion of cases incorrectly classified, with a standard error of 0.011.

Figure 2. CHAID analysis for millennial South African consumers likely to participate in international creative tourism activities. *Creative tourism motivations were measured on a scale from 1–5, where 1 = strongly disagree, and 5 = strongly agree.

The model comprised four main branches derived from the root node, with four levels and 15 nodes. Ten were terminal nodes (2, 5, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14, and 15), with group sizes ranging from 57 to 434 (see ). The best predictor of whether respondents would engage in international creative tourism activities was based on the ‘to gain knowledge and skills’ motivational factor (p-value = 0.000 and chi-square = 93.012).

Beginning with node 1, the left branch included respondents with a score of < = 3.455 for the factor ‘to gain knowledge and skills’. This node was further split by the ‘escape’ motivation factor, which resulted in nodes 5 (those who had a score of < = 2.750) and 6 (those who had a score >2.750). No further split was generated from nodes 5 and 6. Node 2, the second branch from the left, included participants scoring between 3.455 and 3.818 for the ‘knowledge and skills’ factor. Node 2 was terminal.

Node 3, the second node from the right, included participants with scores of 3.818 and 4.636 for the ‘knowledge and skills’ factor. This node was split by the factor ‘escape’ into nodes 7 and 8. Node 8 (n = 88, 90.9% likelihood to engage in international creative tourism activities) was a terminal node. Node 7, with a score of < = 4.5 for the factor ‘escape’, was further split by the factor ‘to earn respect’ into nodes 11, 12, and 13. Node 11 (n = 156, 82.7% showed a likelihood to engage in international creative tourism activities) included those participants with a score of < = 2.0 for the factor ‘to earn respect’, and node 12 included those with a score between 2.0 and 4.5. Node 13 consisted of those with a score of >4.5. These three nodes were all terminal nodes.

Node 4, the right branch, consisted of participants with a score >4.636 for the ‘to gain knowledge and skills’ factor. Node 4 was split by the ‘escape’ factor into nodes 9 and 10. Node 9 was terminal and included participants with a < = 4.0 score for the ‘escape’ factor and a 72.5% likelihood of engaging in international creative tourism activities. Node 10 was further split by the gender variable into nodes 14 and 15. Node 14 (n = 166) included females with an 83.1% likelihood of participating in international creative tourism activities, and node 15 (n = 163) included males with a 90.8% likelihood of participating in international creative tourism activities.

The sample proportion of respondents likely to engage in international creative tourism activities was 73.5%, as indicated in node 0. Four final segments (nodes 8, 11, 14 and 15) showed higher proportions and are depicted in . Based on their characteristics, node 8 was labelled ‘I'd rather escape than learn’, node 11 ‘I'd rather escape than earn your respect’, node 14 ‘Female learners in search of escape’, and node 15 ‘Male learners in search of escape’.

presents the gain index for these segments. Four nodes with more than 100% gains regarding the ‘likely’ category of the dependent variable. It is clear that the gain index for both the ‘I’d rather escape than learn’ segment and the ‘Male learners in search of escape’ segment is 123.5% and 123.6%, respectively, signifying that the likelihood of engaging in international creative tourism activities for these segments is 1.23 times greater than the average.

Table 4. Gain index for international creative tourism activities.

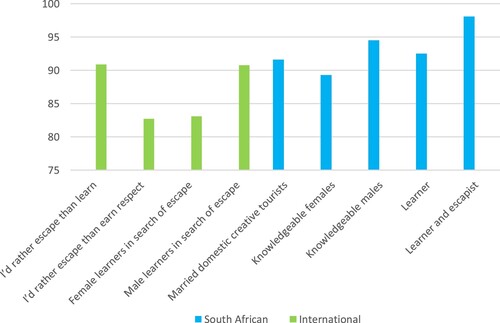

indicates that the two segments with the highest likelihood of engaging in domestic creative tourism activities were the ‘learner and escapist’ and the ‘knowledgeable males’ segments. Regarding international creative tourism activities, the ‘male learners in search of escape’ and the ‘I’d rather escape than learn’ segments showed the highest likelihood.

Figure 3. Segments showing the highest probability of engaging in South African and international creative tourism activities by Millennials.

The χ2 tests show significant statistical differences in categorical variables between the five domestic creative tourist segments and the four international creative tourists segments displayed in . In terms of the domestic segments, the tests show that ‘Married domestic creative tourists’, ‘Knowledgeable females’, ‘Knowledgeable males’, ‘Learner’, and ‘Learner and escapist’ display heterogeneity in terms of the following characteristics: gender (χ2 = 549.788; p < .001), level of education (χ2 = 30.245; p < .001), relationship status (χ2 = 222.615; p < .001), whether they have children (χ2 = 32.048; p < .001), and population group (χ2 = 29.931; p < .001). In terms of the international segments, the tests show that the ‘I'd rather escape than learn’, ‘I'd rather escape than earn your respect’, ‘Female learners in search of escape’, and ‘Male learners in search of escape’ are heterogeneous in terms of the following demographics: gender (χ2 = 332.302; p < .001), level of education (χ2 = 16.866; p < .05), and whether they have children (χ2 = 10.131; p < .001).

Discussion

Understanding the profile of tourists who potentially want to experience creative tourism can assist suppliers and destinations to become more attractive and improve their value proposition. Therefore, this paper aimed to investigate South African millennials’ motivations to engage in creative tourism activities and then built a profile of potential millennial creative tourists based on their motivations and demographic characteristics. It was also ascertained whether the profiles of potential international and domestic South African creative tourists differed from each other.

From the descriptive statistics, South African millennials were more likely to engage in domestic creative tourism activities than travelling internationally to partake in creative tourism. This result contrast with Ruhanen et al. (Citation2015), who found that cultural (creative) tourism is more appealing to international visitors than the domestic market. Indeed, this point could be explained in terms of the relative financial capabilities of individuals in South Africa and the insufficient means to travel long distances. An additional explanation could be the lack of disposable income of the younger populations in the sample. In South Africa, a ‘culture of travel’ has not been developed among Black Africans comparable to the Global North, and this is partly because of the restrictions on mobility and migration by the apartheid regime (Butler & Richardson, Citation2015). In addition, this group also suffers from economic disadvantage and may lack the means to travel, particularly internationally. Nonetheless, the millennial respondents showed a relatively high likelihood of participating in domestic and international creative tourism, which provides a different understanding than Vermeersch et al. (Citation2016), who argued that young adults are generally not interested in cultural (creative) tourism.

The results from the CHAID analysis for domestic creative tourism activities showed that four variables significantly differentiated the segments in the following order of importance: ‘knowledge and skills’, ‘escape’, and ‘relationship status’ and ‘gender’. Married couples in our sample were more likely than singles to engage in domestic creative tourism activities. Our results, therefore, differ from those of Marujo et al. (Citation2019b), who found that marital status does not influence creative tourism experience decisions. At the same time, males who showed a strong motivation for gaining knowledge and skills were slightly more likely to engage in domestic creative tourism activities than females were. Men tend to focus more on ‘doing’ and enjoying a learning experience (Remoaldo et al., Citation2020b). The node that showed the highest probability of engaging in domestic creative tourism activities was the ‘learner and escapist’ node, with a strong motivation for gaining ‘knowledge and skills’ and ‘escape’. For international creative tourism activities, four variables significantly differentiated the segments, with ‘to gain knowledge and skills’ being the most important predictor, followed by ‘escape’, ‘to earn respect’, and ‘gender’. Males in our sample were likelier to engage in international creative tourism activities than females. This result differs from Remoaldo et al.'s (Citation2020b, p. 13) finding that women were generally keener to participate in creative activities related to culture and heritage than men. The node with the highest probability of participating in international creative tourism activities was the ‘I’d rather escape than learn’ node, with a strong motivation for escape. The deduction is that domestic trips are more related to learning and international trips to ‘escape’. International travel takes individuals entirely out of their everyday environments, while domestic creative tourism provides skills focus, with a brief escape from the immediate everyday environment.

When comparing the profiles of potential domestic and international creative tourists, we saw that the motivation factor ‘knowledge and skills’ was the most critical predictor that differentiated the segments in our sample for both domestic and international creative tourism. The transfer of knowledge that adds to the learning process of the tourist is the essence of creative tourism. Furthermore, there appears to be an emerging demand for active, authentic learning experiences that offer a chance for immersion into the local culture (Richards, Citation2020).

The variables that differentiated the segments were the same for international and domestic creative tourism except that, for domestic creative tourism, participants’ ‘relationship status’ played a role, whereas, in international creative tourism, the variable ‘respect’ played a role. Even though the factor ‘unique and once-in-a-lifetime experience’ had the highest mean score, it was not included in any of the CHAID analyses because it was not a significant predictor of the likelihood of domestic or international engagement in creative tourism activities. Perhaps in contrast to visiting a unique cultural heritage site, those respondents engaging in creative tourism see this as an experience that is more integrated into their everyday lives as one could practice creative skills at home, even though it has been learned abroad.

Theoretical contributions

This paper intended to clarify the profile of potential creative tourists, as Duxbury and Richards (Citation2019) called for since there is no clear definition of either at a domestic or international level. With the intent to create a profile of potential creative tourists, the study took demographic characteristics into account and the motivations that would encourage a millennial to engage in creative tourism. This study is the first to examine the creative tourism potential of millennials and the first study of creative tourism demand in South Africa. Whereas previous research used cluster analysis to profile creative tourists, ours used CHAID. Although cluster analysis has traditionally been used to study the segmentation of tourism markets, this paper has demonstrated the utility of the CHAID algorithm (Díaz-Pérez et al., Citation2021). According to Díaz-Pérez et al. (Citation2021), CHAID gives a deeper understanding of the segments than cluster analysis by providing additional levels of uniqueness and variation that could be useful to those marketing and managing creative tourism activities. While previous studies have used actual creative tourists as respondents, our study surveyed potential millennial creative tourists with a view to product development.

Managerial and policy implications

First, the importance of acquiring knowledge and skills when engaging in creative tourism activities was evident domestically and internationally. South African creative tourism attractions should focus on increasing visitors’ skills and providing a learning experience. Through active participation in learning experiences, managers should provide opportunities for tourists to develop their creative potential while at the same time ensuring knowledge acquisition by engaging with the local culture (Ali et al., Citation2016). Concrete examples of learning experiences include; making African arts and crafts and taking part in traditional cooking and traditional African beer brewing classes, taking African literature and philosophy courses, playing in African Jazz improvisation sessions and practising African martial arts. This indicates the potential for developing niche cultural and creative tourism products in areas beyond the beaten tourism track in South Africa. Second, millennials in our sample also engage in creative tourism to escape their daily routine. It is important, therefore, for creative tourism attractions to highlight perceived escape in every aspect of their products. Tourists should be engaged in activities that will allow them to escape their daily routines and to ‘play’ a different character from what they do in their daily lives. For example, providing tourists with an opportunity to wear traditional costumes or dress up as local inhabitants for the activities, they are performing (Ali et al., Citation2016).

Our results can hopefully assist creative tourism attractions in understanding the characteristics of different groups of creative tourists, enabling them to target and attract the right consumers by developing products that will satisfy their needs. This supports Marujo et al.’s (Citation2019b) notion that understanding the profile of creative tourists can assist stakeholders in developing destinations to be best suited for their market. Creative tourism activities should focus on the distinguishing characteristics of each segment when designing creative activities or targeting specific groups of tourists (Tan et al., Citation2014).

Limitations and directions for future research

Using a convenience sampling approach, the results cannot be generalised and do not represent the motivations of all millennials (in South Africa or worldwide), and may exclude those persons that may not be able to travel. It is also acknowledged that creative tourism activities are very much location specific. However, to get a general sense of creative tourism demand, this paper did not ask respondents to indicate their likelihood of engaging in specific creative tourism activities.

Nevertheless, this study contributes to our understanding of millennials as potential consumers of creative tourism experiences. Future studies on this topic could include the following:

An investigation into the specific creative tourism activities that millennials are interested in to assist in product development.

Studying and developing additional potential creative tourist profiles expanded to other age groups in South Africa.

The potential of creative tourism could also be studied in other African countries, especially those closer to core markets in the global North.

Conclusion

Much work will be necessary in the post-Covid-19 world to rebuild the tourism industries of the global South. Creative tourism activities could be an effective economic development tool (Duxbury & Campbell, Citation2011) and assist in cultural regeneration, skills development, providing economic and social development opportunities, improving product development (Spencer & Jessa, Citation2014). In conclusion, this study explains an essential stakeholder in creative tourism, the creative tourist, by segmenting them based on their motivations and demographics. This segmentation allows practitioners to scrutinise their offerings to focus on the right markets. Further, it might also assist policymakers and creative tourism attractions in creating a broad mix of experiences that satisfy the motivations of creative tourists (Tan et al., Citation2014).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Agapito, D., Valle, P., & Mendes, J. (2011). Tourist recommendation through destination image: A CHAID analysis. Tourism and Management Studies, 7, 33–42.

- Ali, F., Ryu, K., & Hussain, K. (2016). Influence of experiences on memories, satisfaction and behavioral intentions: A study of creative tourism. Journal of Travel & Tourism Marketing, 33(1), 85–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/10548408.2015.1038418

- Bessone, G. I., & Spencer, J. P. (2017). Creative tourism as a strategy for regional development and cultural heritage promotion: Sojourning abroad and creativity enhancement. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences, 23(1), 1–13. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC-85b6a6a7a

- Blapp, M., & Mitas, O. (2018). Creative tourism in Balinese rural communities. Current Issues in Tourism, 21(11), 1285–1311. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2017.1358701

- Booyens, I., & Rogerson, C. M. (2019). Creative tourism: South African township explorations. Tourism Review, 74(2), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1108/TR-12-2017-0200

- Butler, G., & Richardson, S. (2015). Barriers to visiting South Africa’s national parks in the post-apartheid era: Black South African perspectives from Soweto. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 23(1), 146–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2014.940045

- Carvalho, R., Ferreira, A. M., & Figueira, L. M. (2016). Cultural and creative tourism in Portugal. Pasos, 14(5), 1075–1082. https://doi.org/10.25145/j.pasos.2016.14.071

- Cavagnaro, E., Staffieri, S., & Postma, A. (2018). Understanding millennial’ tourism experience: Values and meaning to travel as a key identifying target clusters for youth (sustainable). tourism. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0058

- Ceylan, D., Çizel, B., & Karakas, H. (2020). Destination image perception patterns of tourist typologies. International Journal of Tourism Research, 23(3), 401–416. https://doi.org/10.1002/jtr.2414

- Chan, C. S., Chang, T. C., & Liu, Y. (2022). Investigating creative experiences and environmental perception of creative tourism: The case of PMQ (Police Married Quarters) in Hong Kong. Journal of China Tourism Research, 18(2), 223–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388160.2020.1812459

- Chang, L.-L., Backman, K. F., & Huang, Y. C. (2014). Creative tourism: A preliminary examination of creative tourists’ motivation, experience, perceived value and revisit intention. International Journal of Culture, Tourism and Hospitality Research, 8(4), 401–419. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCTHR-04-2014-0032

- Chen, C.-F., & Chou, S.-H. (2019). Antecedents and consequences of perceived coolness for Generation Y in the context of creative tourism – a case study of the Pier 2 Art Center in Taiwan. Tourism Management, 72, 121–129. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2018.11.016

- Chen, J. S. (2003). Market segmentation by tourists’ sentiments. Annals of Tourism Research, 30(1), 178–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(02)00046-4

- Días, A., Melo, J., & Patuleia, M. (2022). Creative tourism and mobile apps: A comparative study of usability, functionality of travel apps. International Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Systems, 15(1), 17–29.

- Díaz-Pérez, F. M., Fyall, A., Fu, X., García-González, C. G., & Deel, G. (2021). Florida state parks: A CHAID approach to market segmentation. Anatolia, 32(2), 246–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/13032917.2020.1856158

- Drummond, J. H., Snowball, J., Antrobus, G., & Drummond, F. J. (2021). The role of cultural festivals in regional economic development: A case study of Mahika Mahikeng. In K. Scherf (Ed.), Creative tourism in smaller communities: Place, culture, and local representation (pp. 79–107). University of Calgary Press.

- Du, X., Liechty, T., Santos, C. A., & Park, J. (2020). I want to record and share my wonderful journey’: Chinese Millennials’ production and sharing of short-form travel videos on TikTok or Douyin. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(21), 3412–3424. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1810212

- Duxbury, N., & Campbell, H. (2011). Developing and revitalising rural communities through arts and culture. Small Cities Imprint, 3(1), 111–122.

- Duxbury, N., & Richards, G. (2019). Towards a research agenda for creative tourism: Developments, diversity, and dynamics. In N. Duxbury & G. Richards (Eds.), A research agenda for creative tourism (pp. 1–14). Edward Elgar.

- Duxbury, N., Silva, S., & de Castro, V. T. (2019). Creative tourism development in small cities and rural areas in Portugal: Insights from start-up activities. In D. A. Jelinčić, & Y. Mansfeld (Eds.), Creating and managing experiences in cultural tourism (pp. 291–304). World Scientific Publishing.

- Field, A. (2013). Discovering statistics using IBM SPSS statistics (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis. Pearson Education.

- Hsu, C. H. C., & Kang, S. K. (2007). CHAID-based segmentation: International visitors’ trip characteristics and perceptions. Journal of Travel Research, 46(2), 207–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287507299571

- Hung, W.-L., Lee, Y.-I., & Huang, P.-H. (2016). Creative experiences, memorability and revisit intention in creative tourism. Current Issues in Tourism, 19(8), 763–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2013.877422

- Jessa, S. (2015). Cultural heritage regeneration of District Six: A creative tourism approach. Master of technology: Tourism and hospitality management. Cape Peninsula University of Technology.

- Kostopoulou, S. (2013). On the revitalized waterfront: Creative milieu for creative tourism. Sustainability, 5(11), 4578–4593.

- Li, P. Q., & Kovacs, J. F. (2022). Creative tourism and creative spaces in China. Leisure Studies, 41(2), 180–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2021.1948596

- Liu, H., Wu, L., & Li, X. (2019). Social media envy: How experience sharing on social networks sites drives millennials’ aspirational tourism consumption. Journal of Travel Research, 58(3), 355–369. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287518761615

- Markwick, M. (2018). Valletta ECoC 2018 and cultural tourism development. Journal of Tourism and Cultural Change, 16(3), 286–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/14766825.2017.1293674

- Marujo, N., do Rosario Borger, M., & Serra, J. (2019a). Tourism, culture and creativity: The case of the CREATOUR project in the Alentejo/Portugal region. In Á. Rocha, A. Abreu, J. de Carvalho, D. Liberato, E. González, & P. Liberato (Eds.), Proceedings of ICOTTS 2019 (pp. 691–704). Springer.

- Marujo, N., Serra, J., & do Rosario Borger, M. (2019b). The creative tourist experience in the Alentejo region: A case study of the CREATOUR project in Portugal. In Á. Rocha, A. Abreu, J. de Carvalho, D. Liberato, E. González, & P. Liberato (Eds.), Proceedings of ICOTTS 2019 (pp. 705–714). Springer.

- McCarty, J. A., & Hastak, M. (2007). Segmentation approaches in data-mining: A comparison of RFM, CHAID, and logistic regression. Journal of Business Research, 60(6), 656–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.06.015

- Monaco, S. (2018). Tourism and the new generations: Emerging trends and social implications in Italy. Journal of Tourism Futures, 4(1), 7–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/JTF-12-2017-0053

- Pallant, J. (2013). SPSS survival manual: A step by step guide to data analysis using IBM SPSS (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Pitombo, C. S., de Souza, A. D., & Lindner, A. (2017). Comparing decision tree algorithms to estimate intercity trip distribution. Transportation Research Part C: Emerging Technologies, 77, 16–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trc.2017.01.009

- Raymond, C. (2003). Case study-creative tourism New Zealand. Creative Tourism New Zealand and Australia Council for the Arts.

- Remoaldo, P. (2022). Editorial for special issue: Trends in creative tourism. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(8), 1479–1481. https://doi.org/10.1177/10963480221074282

- Remoaldo, P., Ghanian, M., & Alves, J. (2020b). Exploring the experience of creative tourism in the northern region of Portugal – a gender perspective. Sustainability, 12(24), 10408. https://doi.org/10.3390/su122410408

- Remoaldo, P., Serra, J., Marujo, N., Alves, J., Gonçalves, A., Cabeça, S., & Duxbury, N. (2020a). Profiling of participants in creative tourism activities: Case studies from small and medium-sized cities and rural areas from Continental Portugal. Tourism Management Perspectives, 36, 100746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2020.100746

- Richards, G. (2011). Creativity and tourism: The state of the art. Annals of Tourism Research, 38(4), 1225–1253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2011.07.008

- Richards, G. (2018). Panorama of creative tourism around the world (Panorama do turismo criativo no mundo). Seminário Internacional de Turismo Criativo, Cais do Sertão. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329530470_Panorama_of_Creative_Tourism_Around_the_World_Panorama_do_turismo_criativo_no_mundo.

- Richards, G. (2020). Designing creative places: The role of creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 85, 102922. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2020.102922

- Richards, G., & Marques, L. (2012). Exploring creative tourism: Editors introduction. Journal of Tourism Consumption and Practice, 4(2), 1–11. http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/11687

- Richards, G., & Morrill, W. (2020). Motivations of global millennial travelers. Revista Brasileira de Pesquisa em Turismo, 14(1), 126–139. https://doi.org/10.7784/rbtur.v14i1.1883

- Richards, G., & Raymond, C. (2000). Creative tourism. ATLAS News, 23, 16–20.

- Richards, G., & van der Ark, L. A. (2013). Dimensions of cultural consumption among tourists: Multiple correspondence analysis. Tourism Management, 37, 71–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.01.007

- Richards, G., & Wilson, J. (2006). Developing creativity in tourists experiences: A solution to the serial reproduction of culture? Tourism Management, 27(6), 1209–1223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2005.06.002

- Rokach, L., & Maimon, O. Z. (2008). Data mining with decision trees: Theory and applications. World Scientific Publishing Co Pte Ltd.

- Ruhanen, L., Whitford, M., & McLennan, C. (2015). Indigenous tourism in Australia: Time for a reality check. Tourism Management, 48, 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2014.10.017

- Sigala, M., & Leslie, D. (2005). International cultural tourism: Management, implications and cases. Elsevier.

- Spencer, J. P., & Jessa, S. (2014). A creative tourism approach to the cultural-heritage regeneration of District Six, Cape Town. African Journal of Physical Health Education, Recreation and Dance, 20(4), 1455–1472. https://journals.co.za/doi/abs/10.10520/EJC166093

- StatsSA. (2018). Education series volume VI: Education and labour market outcomes in South Africa, 2018. http://www.statssa.gov.za/publications/92-01-06/92-01-062018.pdf.

- StatsSA. (2019). Mid-year population estimates. Statistical Release (P0302). Statistics South Africa. Republic of South Africa.

- Suess, C., Woosnam, K. M., & Erul, E. (2020). Stranger-danger? Understanding the moderating effects of children in the household on non-hosting residents’ emotional solidarity with Airbnb visitors, feeling safe, and support for Airbnb. Tourism Management, 77, 103952. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2019.103952

- Suhartanto, D., Brien, A., Primiana, I., Wibisono, N., & Triyuni, N. N. (2020). Tourist loyalty in creative tourism: The role of experience quality, value, satisfaction, and motivation. Current Issues in Tourism, 23(7), 867–879. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2019.1568400

- Tan, S.-K., Kung, S.-F., & Luh, D.-B. (2013). A model of ‘creative experience’ in creative tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 41, 153–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2012.12.002

- Tan, S.-K., Luh, D.-B., & Kung, S.-F. (2014). A taxonomy of creative tourists in creative tourism. Tourism Management, 42, 248–259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tourman.2013.11.008

- van Middlekoop, M., Borgers, A., & Timmermams, H. (2003). Inducing heuristic principle of tourist choice of travel mode: A rule-based approach. Journal of Travel Research, 42(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287503254116

- Vehovar, V., Toepoel, V., & Steinmetz, S. (2016). Non-probability sampling. In C. Wolf, D. Joye, T. W. Smith, & Y. Fu (Eds.), In the sage handbook of survey methods (pp. 329–345). Sage.

- Veiga, C., Santos, M. C., Águas, P., & Santos, J. A. C. (2017). Are millennials transforming global tourism? Challenges for destinations and companies. Worldwide Hospitality and Tourism Themes, 9(6), 603–616. https://doi.org/10.1108/WHATT-09-2017-0047

- Vermeersch, L., Sanders, D., & Willson, G. (2016). Generation Y: Indigenous tourism interests and environmental values. Journal of Ecotourism, 15(2), 184–198. https://doi.org/10.1080/14724049.2016.1165233

- Wessels, J. A., & Douglas, A. (2020). Exploring creative tourism potential in protected areas: The Kruger National Park case. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Research, 46(8), 1482–1499. https://doi.org/10.1177/1096348020983532

- Woosnam, K. M., Ribeiro, M. A., Denley, T. J., Hehir, C., & Boley, B. B. (2021). Psychological antecedents of intentions to participate in last chance tourism: Considering complementary theories. Journal of Travel Research, 61(6), 1342–1357. https://doi.org/10.1177/00472875211025097