ABSTRACT

Secure attachment has broad and long-lasting benefits for the development and wellbeing of a child. Conversely, disorganized attachment is associated with social, emotional, and behavioral problems in children, and later psychopathology. Children with a developmental delay or disability (DD) may be at greater risk of insecure or disorganized attachment than children without DD. This systematic review aims to (1) synthesize the available evidence worldwide regarding attachment and children with DD and (2) to examine the effectiveness of interventions employed to prevent or address attachment insecurity for this population. Peer reviewed articles with four-fold attachment classification data or attachment interventions for children with DD were included in the review. Seventeen databases were searched for studies published in English from January 1980 to January 2019. The systematic review protocol was registered a priori with PROSPERO (CRD42018117574). Twenty-three articles met the inclusion criteria, nine containing strange situation procedure (SSP) data and 14 relating to interventions. Meta-analysis was conducted with data from six of the SSP articles (n = 215). The remaining articles were reviewed narratively. Results indicate that children with DD are significantly less likely to develop a secure attachment and significantly more likely to develop a disorganized attachment than children without DD. Emerging research indicates promise that early intervention may be effective in improving attachment security.

Introduction

Parent–child attachment is the enduring affectionate bond between a child and their parent or caregiver (Bowlby, Citation1982a). Attachment behaviors such as crying, reaching out, or clinging to a primary carer when in need of protection or comfort are thought to have evolved primarily as survival mechanisms (Bowlby, Citation1982a). These behaviors adjust over time as an infant matures and the attachment relationship forms, influenced by the child’s expectations of their carer’s behavior based on previous experience (Bowlby, Citation1982a). Children learn to regulate their behavior and emotions and develop their sense of self-worth through their attachment relationships, using their attachment figure as a secure base from which to explore and play (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Citation1978; Bowlby, Citation1982a). The quality of parent–child attachment relationships theoretically creates a template that will shape the foundation of future relationships across the lifespan (Bowlby, Citation1982b). Empirically, secure attachment is associated with positive long-term outcomes such as language proficiency (Belsky & Fearon, Citation2002), social skills (Groh et al., Citation2014), executive function (Bernier, Carlson, Deschenes, & Matte-Gagne, Citation2012), and emotional wellbeing (Sroufe, Citation2005). Conversely, insecure and more so, disorganized attachment is associated with a higher likelihood of behavioral issues (Fearon, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van Ijzendoorn, Lapsley, & Roisman, Citation2010), poorer physical health (Puig, Englund, Simpson, & Collins, Citation2013), and later psychopathology (Carlson, Citation1998).

There is evidence to suggest that children with a developmental delay or established disability (DD) are less likely to develop a secure attachment and may be more likely to develop a disorganized attachment, which impacts negatively on their development than typically developing children (van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermanskranenburg, Citation1999). Early Childhood Intervention (ECI) professionals work with infants and young children with DD and their families to optimize wellbeing, participation, and development, and so have both cause and opportunity to support the development of secure attachment and thus positive development. There is evidence that intervention can support the development of secure attachment and prevent disorganized attachment in typically developing children (Facompré, Bernard, & Waters, Citation2018). The following systematic review aims to explore the evidence regarding the attachment security of children with DD, the interventions that have been employed to address attachment in this population, and the implications of the findings for ECI.

Attachment quality

The “gold standard” (Cassidy, Jones, & Shaver, Citation2013, 1415), in valid and reliable clinical assessment of attachment security known as the strange situation procedure (SSP) can be used to identify the four main categories of attachment quality – secure (B), insecure-avoidant (A), insecure-ambivalent (C), and insecure-disorganized (D). The SSP is a dyadic measure, categorizing the quality of attachment security a child has with a parent or caregiver, rather than measuring or pathologizing an innate characteristic of the child (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Citation1978). Trained observers rate the responses of children to a series of orchestrated separations and reunions with their caregivers (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Citation1978). Secure attachment (B) is associated with sensitive and responsive caregiving and may be indicated by the child showing some distress when their caregiver leaves them, seeking reunion upon their return, and readily settling (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Citation1978). Insecure-avoidant attachment (A) is associated with low parental sensitivity and overly stimulating, invasive, or controlling caregiver behavior (Fearon & Belsky, Citation2016) and may be indicated by a child’s muted reaction to their caregiver leaving and not seeking reunion upon their return (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Citation1978). Insecure-ambivalent attachment (C) is associated with under-involved or inconsistent caregiver responsiveness (Fearon & Belsky, Citation2016) and may be indicated by the child becoming quite distressed when their caregiver leaves; but as the name suggests, they may show an ambivalent response upon the caregiver’s return, perhaps seeking reunion but displaying anger toward the caregiver and having difficulty settling (Ainsworth, Blehar, Waters, & Wall, Citation1978). Insecure-disorganized (D) attachment (Main & Solomon, Citation1986) may be indicated by a child’s “conflicted, disoriented, or fearful behavior” (Granqvist et al., Citation2017, p. 4) toward their caregiver in the SSP; for example, freezing or fleeing when their parent returns to them. Children who have experienced abuse and neglect have four times the likelihood of developing a disorganized attachment (Madigan et al., Citation2006). Disorganized attachment can also be associated with a caregiver’s unresolved trauma or grief or the child experiencing frequent or prolonged separations from their caregiver (Granqvist et al., Citation2017). The association between caregiver sensitivity and quality of attachment is weak to moderate (Fearon & Belsky, Citation2016). Various hypotheses have been put forward regarding additional variables that may influence attachment quality including other parenting behaviors, broader influences such as marital satisfaction and social support or that some children may be more susceptible to parenting behaviors than others (Fearon & Belsky, Citation2016). The average classification rates for non-clinical, middle-class populations in the USA, aged up to 24 months (n = 2,104), were found as follows: (A) insecure-avoidant, 15%; (B) secure, 62%; (C) insecure-ambivalent, 9%; and (D) insecure-disorganized, 15% (van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermanskranenburg, Citation1999).

Attachment in children with disabilities

There is a growing body of research indicating that attachment plays an important role in the development of children with DD as it does with all children. Research conducted with children with severe disabilities using sensor socks to measure biological responses found that the children demonstrated preferential relationships with their parents over a stranger (Vandesande, Bosmans, Schuengel, & Maes, Citation2019). Furthermore, it was demonstrated that this relationship served a regulatory function, that is, it reduced their responses to stressors and provided comfort (Vandesande, Bosmans, Schuengel, & Maes, Citation2019).

Unfortunately, though children with DD do form attachments, a meta-analysis conducted over 20 years ago indicated that they may have an increased risk of these attachments being insecure or disorganized (van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermanskranenburg, Citation1999). There are a range of possible explanations for this increased risk. Children with DD may be delayed in the development of their attachment behaviors, and their ability to signal their needs may be impaired, making it more difficult for their parents to interpret and respond to their needs in an attuned way (Howe, Citation2006). Children with Down syndrome, for example, while found to display the same organization of emotional responses as typically developing children during the SSP, did so with reduced intensity, showed less distress and recovered more quickly (Vaughn et al., Citation1994). The lack of eye contact and reciprocal smiling from a visually impaired infant or their tendency to go still and quiet as their parent enters the room may lead to misunderstandings, impacting the parent’s feelings and influencing the bi-directional process of attachment forming (Howe, Citation2006; van den Broek et al., Citation2017). Similarly, the impact of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) on social communication skills may have the potential to influence the development of the attachment relationship (Grzadzinski, Luyster, Gunn Spencer, & Lord, Citation2014). A recent study found that children with a high risk of ASD were more than seven times as likely to be later diagnosed with ASD if they had an insecure attachment, raising further questions about the interplay between attachment security and ASD symptomology (Martin, Haltigan, Ekas, Prince, & Messinger, Citation2020).

There is emerging evidence to suggest that when a child has DD, the parent’s resolution to the diagnosis may be a significant influence on their child’s attachment security (Barnett et al., Citation2006). Strong feelings arising from the birth or diagnosis of a child with DD can be challenging to resolve and these feelings may impact the attachment relationship due to the effects on parental sensitivity (Feniger-Schaal & Oppenheim, Citation2013). Poverty, stress, and mental health issues have been demonstrated to increase the likelihood of insecure attachment (Anderson, Gooze, Lemeshow, & Whitaker, Citation2012; Atkinson et al., Citation2000; van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermanskranenburg, Citation1999). The additional stressors for a parent or carer involved in caring for a child with a disability such as the search for information and services, financial strain, and the possibility of social isolation, can all impact a parent’s ability to provide attuned and responsive caregiving (Guralnick, Citation2005); and children with DD are more likely to experience abuse and neglect than children without DD (Maclean et al., Citation2017). Finally, there is evidence that suggested children with a disability have differential susceptibility to the effects of early parenting, that is, parenting behaviors were even more important to children with DD than children without DD (Innocenti, Roggman, & Cook, Citation2013).

Children learn from their relationships and everyday experiences and need to practice the skills they are learning to build competency (Dunst, Citation2007). Children with DD require more time to learn and practice skills and more praise and encouragement from adults to enable them to make the most of their learning opportunities (Odom & Wolery, Citation2003). Problems in attachment can lead to parents having less interaction with their child and providing less stimulation (Malekpour, Citation2007). ECI professionals should therefore have the development of positive and responsive parent–child relationships as a “major focus” (Moore, Citation2012, p. 6).

Aims and hypothesis

Over 20 years ago, van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, and Bakermanskranenburg (Citation1999) conducted a meta-analysis regarding disorganized attachment and found lower security and higher disorganization for children with DD. Unfortunately, the findings were not discussed in detail as children with DD were only a small part of the sample analyzed (van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermanskranenburg, Citation1999). Teague, Gray, Tonge, and Newman (Citation2017) and Rutgers, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, and van Berckelaer-Onnes (Citation2004) conducted systematic reviews that looked at attachment patterns of children with ASD. Teague, Gray, Tonge, and Newman (Citation2017) found that 47% of children with ASD had secure attachments, whereas Rutgers, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, and van Berckelaer-Onnes (Citation2004) found that 53% were secure. Additionally, Hamadi and Fletcher (Citation2021) reviewed studies of attachment quality for children and adults with intellectual disability and found a higher prevalence of insecure and disorganized attachment. From the evidence of these reviews, it is hypothesized that children with DD are less likely to form a secure attachment and more likely to form a disorganized attachment than children without DD.

There have been two meta-analyses regarding interventions to improve attachment security. However, one excluded children with DD (Facompré, Bernard, & Waters, Citation2018) and the other included only two papers involving children with DD out of 70 studies (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, Citation2003). The authors of the present review hypothesize that intervention can improve the attachment security of children with DD.

The following systematic review seeks to update the meta-analysis of 1999 in relation to children with DD and to additionally explore the evidence regarding attachment interventions with this population. Consequently, the present systematic review aims to answer the following questions:

Research Question 1. (RQ1) - What is the available evidence regarding the attachment quality of children with DD?

Research Question 2. (RQ2) - What is the available evidence regarding the effectiveness of interventions used to improve the attachment security of children with DD?

The implications for the ECI sector of the findings will be discussed.

Method

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA-P) procedures and methods (Moher et al., Citation2015) were used in this systematic review. The review aimed to synthesize the evidence available regarding attachment quality of children with a disability or developmental delay, and the interventions to improve attachment security with this population.

Article search

Prior to the commencement of the study, the parameters were established using PICOS (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, & Altman, Citation2009) and the systematic review protocol was registered a priori with PROSPERO (CRD42018117574). The electronic search strategy was developed in consultation with a specialist research librarian and included an extensive array of terms used for disability or developmental delay AND attachment AND child. The strategy aimed to locate both published and unpublished studies. Studies published since January 1980 were included as Main & Solomon published their first paper on disorganized attachment (D) in 1986, so this would safely capture any studies including category D. Databases searched were as follows: Australia and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (anzctr.org.au/), CINAHL (EBSCO), ClinicalTrials.gov (clinicaltrials.gov/), Cochrane Library, Embase (Ovid), FAMILY (informit), Medline (1996-Ovid), PsychINFO 1987 (Ovid), PubMed, OpenGrey (opengrey.cu/), OTseeker, PEDro, PsychBITE, SCOPUS (Elsevier), Sociology database (PROQUEST), SpeechBITE (speechbite.com), and WorldCat (limited to theses) (www.worldcat.org/). The search was conducted in January 2019.

Handsearching was conducted using the reference lists of selected studies, reviews, and studies on known interventions. Handsearching elicited a further 23 studies.

Study selection and data extraction

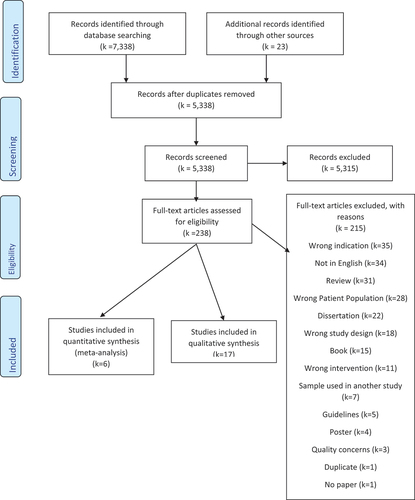

See for details of study selection. From the electronic search, 7,338 citations were exported into EndNoteX8, an electronic program used to manage references. Two thousand twenty-three duplicate papers were detected and deleted. The remaining 5,315 citations were then exported into Covidence, an electronic program to manage systematic reviews. Two authors with different disciplinary backgrounds (SA and MF), independently scanned all the titles and abstracts to determine which were relevant or irrelevant. Any disagreements were discussed, and a mutual decision made. A third author, (ML) was available to resolve any disputes but was not required. Both the first and second authors then independently examined all the full texts for the 238 articles deemed relevant from the electronic search and hand search, meeting to discuss any disagreements, again resolving without the need for the third author.

Tailor-made data extract templates were used as different templates were required for the SSP articles than for the intervention articles. Cochrane’s risk-of-bias tool was employed as articles were examined for quality and risk of bias including examination of interrater reliability, blinding, and use of validated measures (Higgins et al., Citation2011). The final selection consisted of nine SSP studies and 14 intervention articles.

Of the nine SSP articles included, only six presented the data in a comparable format enabling meta-analysis. The data extracted from the remaining six articles is presented in , and the other three have been included for discussion. For studies where the SSP was repeated on the same children when they were older, only the data from the first assessment was used as (1) to avoid using multiple data from the same samples, (2) the first measure is likely to be a larger sample size, and (3) there is a possibility of the second measure being influenced by the first (van IJzendoorn, Goldberg, Kroonenberg, & Frenkel, Citation1992).

Table 1. Evidence table – selected articles.

Study parameters

Inclusion/exclusion criteria were as follows:

Population: (RQ1 and RQ2) Children with a disability or developmental delay aged from birth to 7-years old, of any race or gender, and their parents or caregivers. Substantial functional limitations must be identified that require extended and coordinated services (National Disability Insurance Agency, Citation2019). Children at risk of DD, for example, due to poverty, prematurity, or prenatal exposure to drugs of addiction, were excluded. Children with a delay that may be addressed with a single service response, for example, speech therapy, were also excluded from this study.

Intervention: (RQ2) Any individual or group-based intervention that aimed to improve attachment, bonding, parent–child interactions, parent–child relationships, or key factors thus far thought to foster secure attachment, namely parental sensitivity, reflectiveness, or responsiveness.

Comparator: (RQ1) SSP studies were included whether they had a comparator or not. (RQ2) Quantitative intervention studies required a comparator.

Outcomes: (RQ1)—Owing to available evidence that suggested that the reduced likelihood of children with DD developing a secure attachment was due to the increased risk of disorganized attachment, only SSP studies that reported on disorganized attachment, that is, used the four-fold approach to classification were included. (RQ2)—For intervention studies, outcomes can be assessed by any means but must have reported findings on either attachment, parent–child relationships, parent–child interactions, bonding, parental reflective functioning, parental responsiveness, or child attachment behaviors.

Study design: (RQ1 and RQ2)—All studies were peer-reviewed, journal publications in English. (RQ1)—The SSP was validated on children without DD. There is a risk of behaviors such as stereotypies, tics, and mistimed movements, common to children with neurological disorders, being misinterpreted as disorganized attachment. Guidelines developed to assist SSP coders avoid this risk, state that a determination of disorganized attachment should only be made for children in populations at risk of neurological disorders, without the inclusion of any of the “dual indices” detailed within (Pipp-Siegel, Siegel, & Dean, Citation1999). As such only SSP studies that employed these guidelines, or some similar overt strategy were included. (RQ2)—For quantitative intervention studies, only randomized control trials (RCTs) or quasi-RCTs were included. Qualitative intervention studies were also included if they provided insight into the feasibility or acceptability of implementing attachment interventions in the context of ECI. Using the JBI Levels of Evidence, levels 1 to 4 were included if meeting the inclusion criteria set out here (The Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2013). The levels of evidence for each study are recorded in .

Exclusions

Regarding RQ1, several papers that were included in the reviews by Rutgers, Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, and van Berckelaer-Onnes (Citation2004), Teague, Gray, Tonge, and Newman (Citation2017) and van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, and Bakermanskranenburg (Citation1999) were not included in the current review because either they were from conference presentations, books, or personal communications; the sample was children with illnesses rather than disabilities; they did not include the D category; or the study sample was already used in a study that had been included. In total, across RQ1 and RQ2, 215 exclusions from the 238 relevant articles were made for (1) “Wrong Indication” (35 articles) – this related to RQ1 only and meant that attachment was not assessed using the SSP or that the D category was not included; (2) “Not in English” (34 articles); (3) “Review” - the article was a literature review or systematic review (31 articles); (4) “Wrong Patient Population” - did not include children with DD (28 articles); (5) “Dissertations” (22 articles); (6) “Wrong Study Design”- quantitative studies that were not RCT or quasi-RCT, for example, intervention studies that did not include a comparison group (18 articles); (7) “Books” (15); (8) “Wrong Intervention” - for example, the intervention was designed to remediate behavior or autism rather than any of the aims outlined in the inclusion criteria (11); (9) “Sample used in another study” - the sample was used in another study that was included (7 articles); (10) Guidelines (5 articles); (11) Poster (4 articles); (12) “Quality concerns” (3 articles); (13) “Duplicate” - one further duplicate was located; and (14) “No paper” - one article was unable to be located despite assistance from university librarians. See for details.

Of the nine selected SSP studies, four used the Pipp-Siegel guidelines, whereas four employed other overt strategies to ensure that children were not inappropriately categorized as having disorganized attachment (D) such as excluding stereotypies from being considered as possible indicators of disorganization and taking baseline behavior into account. One study included that did not take such measures involved children with hearing rather than neurological impairments. All included studies contained details regarding both chronological and developmental age. All children had a minimum developmental age of 12 months and sufficient ambulatory skills to independently locomote in the SSP.

Data analysis

RQ1

– Part A – Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis was undertaken with data from six of the SSP studies (see ). The proportions of attachment types A, B, C, and D, based on the data in , were synthesized with a random effects meta-analysis. Incorporating random effects is important for more accurately assessing uncertainty in synthesized results. The estimates for the attachment-type proportions were calculated assuming a binomial distribution, using the Clopper–Pearson method for calculating the confidence intervals (Nyaga, Arbyn, & Aerts, Citation2014). Estimation of heterogeneity between study estimates was assessed with the usual assumption that the true attachment-type proportion is randomly and normally distributed between the different studies (DerSimonian & Laird, Citation1986). The contributory weight of a study to the meta-analysis was estimated using the well-known inverse variance method, that is, the lower the variance for an included study’s estimate, the higher the weight that study has in the meta-analysis (Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, Citation2017). Using this approach, forest plots were produced to illustrate how the various studies may have contributed to the synthesized result. As some of the studies to be synthesized had a zero prevalence, a transformation of the study proportions was required using the mathematical arcsine function. In particular, the Freeman–Tukey double arcsine transformation (FTT) was used for its superior variance stabilizing properties especially in the situation where proportions are close to 0 or 1 (Nyaga, Arbyn, & Aerts, Citation2014). In the studies synthesized here, there was one study with a zero prevalence for attachment type A and two studies with a zero prevalence for attachment type C. However, there has been some evidence to suggest that, in the circumstances of many orders of magnitude of differences in study sample sizes, the FTT may give misleading results (Schwarzer, Chemaitelly, Abu-raddad, & Rücker, Citation2019). Although, the data used in this meta-analysis did not suffer from this problem, recommendations of Veroniki et al. for a sensitivity analysis were followed (Veroniki et al., Citation2015, Citation2016).

To this aim, the meta-analysis was conducted with four different methods and four different methods of estimating between study heterogeneity. Firstly, three different transforms were applied to the data-FTT, logit, and arcsine (Barendregt, Doi, Lee, Norman, & Vos, Citation2013). With each of the three transforms, three different methods were used to estimate between-study heterogeneity, the popular DerSimonian and Laird method, restricted maximum likelihood (REML), and the Hunter–Schmidt method (Veroniki et al., Citation2015). Further, the general linear mixed methods model (GLMM) was used with its well-known and inherent method of estimating between-study heterogeneity (Schwarzer, Chemaitelly, Abu-raddad, & Rücker, Citation2019). For this sensitivity analysis, the 10 results were compared to their overall mean (Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, Citation2017; Thompson & Higgins, Citation2002).

In synthesizing results from other studies, it is important to assess heterogeneity between studies. If studies are severely heterogeneous, then synthesizing their results is not meaningful. Heterogeneity is defined in the usual way as variations in effect sizes between studies that are beyond sampling variability. Heterogeneity may occur when the true effects in each study are different possibly due to such factors as clinical or methodological approaches or a combination of both (Deeks, Higgins, & Altman, Citation2017; Thompson & Higgins, Citation2002). Statistical level of significance was set at p = 0.05. All analyses are carried out with Stata16 (StataCorp, Citation2017).

RQ1

– Part B – Narrative synthesis

Data in three further SSP studies were not directly comparable. Two of these studies reported data for force classified A, B, and C categories, additionally noting that the number of children classified as D (Lederberg & Mobley, Citation1990; Willemsen-Swinkels, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Buitelaar, van Ijzendoorn, & van Engeland, Citation2000). A third study distinguished between children they assessed as having disorganized attachment due to relational issues from those with disorganized attachment due to autism (Rozga et al., Citation2017). The data from these three studies were excluded from the meta-analysis but reviewed narratively.

RQ2

The studies included were highly heterogeneous in all aspects so were reviewed narratively. Levels of certainty regarding net benefit were assessed in accordance with the United States Preventative Task Force (USPSTF) definitions (United States Preventative Task Force UPSTF, Citation2012).

Results

RQ1

– Part A – Meta-analysis

presents data from the children with DD within the six SSP studies used in the meta-analysis. In total, data included 215 children from the USA, Israel, and the Netherlands. Children were ethnically diverse, and the gender split was 34% (73) female and 66% (142) male. Regarding DD, 80 of the children had ASD, 52 had a nonspecific intellectual disability, 39 had a neurological condition such as cerebral palsy or epilepsy, 30 had Down syndrome, and 14 had pervasive developmental disorder (PDD). Overall, 42.3% of the children were classified as having secure attachment (B), 15.3% (A) insecure-avoidant, 13.5% (C) insecure-ambivalent and 28.8% were classified insecure-disorganized (D).

Compared to the overall mean of the 10 results, the logit transform tended to have estimates of prevalence that were approximately .01 to .02 greater in absolute terms and up to .03 greater for attachment type C. The FFT and GLMM results were the nearest to the overall mean with magnitudes of absolute differences generally about .006 or lower, up to at most of about .01. Among the 10 different methods, there was little difference between the estimation of between study heterogeneity. The results from this sensitivity analysis gave us confidence to rely on FTT because of its possibly superior variance stabilization property in the presence of studies with zero proportions.

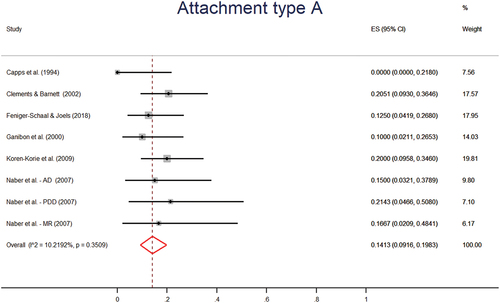

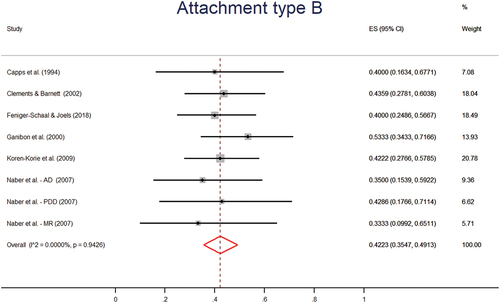

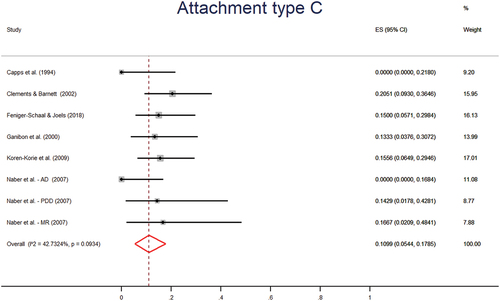

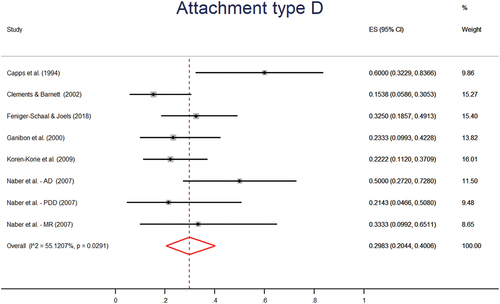

The results of the meta-analysis using FTT and the DerSimonian and Laird (Citation1986) method for estimating between-study heterogeneity are presented in . The synthesized proportions for attachment types A-D, along with their 95% confidence intervals, are estimated as approximately (A) 0.14 (0.09, 0.20), (B) 0.42 (0.35, 0.49), (C) 0.11 (0.05, 0.18), and (D) 0.30 (0.20, 0.40). Between-study heterogeneity was very low for studies estimating proportions of attachment types A and B and moderate for attachment types C and D but statistically significant only for attachment type D, p = 0.03. Variability in the included studies’ proportions due to between-study heterogeneity was estimated at 10.22%, 0.00%, 42.73%, and 55.12% for attachments A, B, C, and D, respectively. This indicates that the included studies were sufficiently similar to make their synthesis meaningful for each attachment type.

Table 2. Attachment-type proportion estimates from Table 1 data using a random effect meta-analysis.

display the forest plots for each attachment type. The red dotted line denotes the estimated synthesized proportion from combining the included studies. The width of the red diamond denotes the width of the 95% CI for the synthesized proportion. For each included study, its found proportion is denoted by a dot that is surrounded by a grayed rectangle, which represents the weight of the study in the meta-analysis. The thin line protruding from the dot is the 95% CI for the particular study’s found proportion. This information is also displayed in columns at the right of the forest plot.

The proportions found in the previous meta-analysis (van Ijzendoorn, Schuengel, & Bakermanskranenburg, Citation1999) were statistically tested against what was found with the data presented here. Attachment type B associated with a proportion of 0.62 and attachment type D with 0.15, were tested against 0.4223 and 0.2983, respectively, using a two-sided test of difference in proportions. These differences were statistically significant at the 0.05 level with associated p values of 0.0001 and 0.0011, respectively.

RQ1 –

Part B – Narrative synthesis

The studies not included in the meta-analysis due to the data not being set out in a comparable manner also supported this finding of comparatively low rates of secure attachment and high rates of disorganized attachment for children with DD. Lederberg and Mobley (Citation1990) compared hearing impaired children to hearing children, both with hearing mothers. They reported that 10 of the 41 (24.4%) hearing impaired children were classified as D, compared to four of 41 (10%) hearing children but the results were non-significant (Lederberg & Mobley, Citation1990). Rozga et al. (Citation2017) studied 30 preschool children with ASD and found that 57% experienced disorganized attachment due to autism, 17% were relationally disorganized and 23% were secure (Rozga et al., Citation2017). In the Willemsen-Swinkels, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Buitelaar, van Ijzendoorn, and van Engeland (Citation2000) study, seven of 13 children (53.8%) with PDD and an intellectual disability were classified as D. This compared to three of 18 (16.7%) who had PDD but no intellectual disability and two of 19 (10.5%) of non-clinical control children.

Overall, the data examined in this systematic review indicate that children with DD are at significantly greater risk of forming a disorganized attachment and that fewer than half will develop a secure attachment.

RQ2 – Narrative synthesis

presents data from the studies meeting the inclusion criteria for this part of the systematic review. Though some interventions employ a mix of techniques, the common elements used across the included studies could arguably be grouped as cognitive, behavioral, and physical interventions.

Cognitive: Cognitive intervention elements of programs attempted to get the parent to reflect on the child’s view of the world and see the child or infant as a person with skills, traits, needs, and intentions, to develop the parent’s sensitivity, insightfulness, and reflective functioning. Studies included with such cognitive elements included Circle of Security (CoS) (Fardoulys & Coyne, Citation2016a), parent-infant psychotherapy (PIP) (Acquarone, Citation1995), and the unbranded intervention studied by Brisch, Bechinger, Betzler, and Heinemann (Citation2003). The CoS and PIP studies were case studies with one or two dyads participating so no generalizations can be made. However, both studies found that a shift in the mother’s understanding of the child’s inner world could shift the child to a more secure relationship (Acquarone, Citation1995; Fardoulys & Coyne, Citation2016b). The Brisch, Bechinger, Betzler, and Heinemann (Citation2003) study (n = 87) randomly assigned infants to experimental or control groups after preterm delivery. It evolved that the percentage of children with neurological impairment was very uneven between the two groups, complicating comparison (Brisch, Bechinger, Betzler, & Heinemann, Citation2003). Brisch, Bechinger, Betzler, and Heinemann (Citation2003) found that in the control group there was a high correlation between neurological impairment and insecure attachment as measured by the SSP, whereas the group receiving the intervention did not show this association. This finding indicated that the intervention, which involved a parent group, individual psychotherapy, sensitivity training for a day and a one-off home visit from a nurse and psychotherapist, may have prevented insecure attachment in neurologically impaired infants. However, as the intervention had a multi-method approach, no conclusions could be drawn regarding the effectiveness of any one element of the intervention such as the cognitive component.

Behavioral: Behavioral interventions involved coaching parents regarding parent–child interactions to improve parental responsiveness. Often these behavioral interventions involved showing the parent video of themselves interacting with their child. Examples of these interventions included focused playtime intervention (FPI) (Siller, Swanson, Gerber, Hutman, & Sigman, Citation2014), PLAY Project Home Consultations Intervention Program (PLAY) (Solomon, Van Egeren, Mahoney, Quon Huber, & Zimmerman, Citation2014), relationship focused intervention (RFI) (Kim & Mahoney, Citation2005), and the variations of the video-feedback intervention to promote positive parenting (VIPP) (Platje, Sterkenburg, Overbeek, Kef, & Schuengel, Citation2018; Poslawsky et al., Citation2015). The authors of the FPI study (n = 70) described it as a parent education program (Siller, Swanson, Gerber, Hutman, & Sigman, Citation2014) but as FPI involved video feedback of parent–child interactions with the aim of improving parental responsiveness, it was considered to fit in this group of coaching interventions. Small-to-medium effect sizes were found in the FPI study for parent-reported, child attachment behaviors over the 12-week (one 90-min home training session per week) intervention for children with ASD (Siller, Swanson, Gerber, Hutman, & Sigman, Citation2014). Additionally, the children in the control group showed an increase in avoidant behaviors over time indicating that parent–child interactions may worsen over time without intervention (Siller, Swanson, Gerber, Hutman, & Sigman, Citation2014). The PLAY intervention (n = 125) involved a year of monthly coaching of parents of children with ASD and found substantial improvements in parent–child interactions as measured by the interactional dimensions of the Maternal Behavior Rating Scale and the Child Behavior Rating Scale (Solomon, Van Egeren, Mahoney, Quon Huber, & Zimmerman, Citation2014). The VIPP variants, VIPP-V (n = 77) and VIPP-AUTI (n=78), both aimed to improve parent–child interactions and found an increase in parental efficacy but not in parental sensitivity (Platje, Sterkenburg, Overbeek, Kef, & Schuengel, Citation2018; Poslawsky et al., Citation2015). The ASD version also found similarly to studies on the use of VIPP with other populations, a moderate effect size for reduction in parental intrusiveness (Poslawsky et al., Citation2015). Additionally, Poslawsky et al. (Citation2015) found that those in the experimental group were more than twice as likely to significantly reduce in autism symptomology than those in the control group. The Seifer study (n = 40) similarly found that their intervention, which consisted of brief weekly coaching for a maximum of six sessions, found moderate effect sizes for increased parental responsiveness and reduced intrusiveness 8 months later (Seifer, Clark, & Sameroff, Citation1991). Finally, the intent of RFI was to enhance parental responsiveness and they succeeded in their aim in the included study (n = 18), once again with a moderate effect size (Kim & Mahoney, Citation2005). Kim and Mahoney (Citation2005) also found an 18% increase in children’s interactive behaviors but this was not statistically significant.

The DIRFloortime® intervention (n = 40) presented a blend of cognitive and behavioral approaches (Sealy & Glovinsky, Citation2016). With the help of video feedback, parents were coached in their interactions with their children with the aim of improving their reflective functioning, that is, developing parental understanding of their child’s needs and feelings. The study found a large and significant effect on parental reflective functioning following their 24 hr over 12-week intervention (Sealy & Glovinsky, Citation2016).

Physical: Physical interventions included Kangaroo Mother Care (KMC) which involved continuous skin-to-skin contact between pre-term infants and their parents and exclusive breast-feeding (Charpak et al., Citation2017), massage interventions (Cullen-Powell, Barlow, & Cushway, Citation2005; Hansen & Ulrey, Citation1988), and physical therapy (Chiarello & Palisano, Citation1998). The KMC study (n = 364) found 20 years later (n = 264) that parents in the experimental group were more child-oriented, protective, and nurturing (Charpak et al., Citation2017). Unfortunately, results for those participants who had a disability were not separated from those without a disability, which limits the relevance of the conclusions. One of the massage studies was an RCT (n = 19) which found that the experimental group made significantly greater gains in observed attachment-separation behaviors than the control group (Hansen & Ulrey, Citation1988). The other massage study, was a qualitative study (n = 15) and parents reported increased feelings of closeness to their child with ASD (Cullen-Powell, Barlow, & Cushway, Citation2005). Interestingly, though the study on the physical therapy intervention (n = 38) sought to improve parent–child relationships, the primary focus seemed to be on coaching mother’s physical positioning of their child and mothers in the experimental group became more directive following the intervention (Chiarello & Palisano, Citation1998).

Overall, the narrative synthesis of data pertaining to RQ2 found a range of small to large effect sizes of attachment interventions for children with DD. Owing primarily to the limited number and size of the studies, the level of certainty regarding the evidence for any one of these interventions was rated as low (United States Preventative Task Force UPSTF, Citation2012). The limited evidence available for cognitive interventions addressing parental insightfulness and reflective functioning indicated that it may be possible to prevent insecure attachment in neurologically impaired infants; however, more research is required to establish this. Evidence for behavioral interventions was moderate and indicated that video feedback and coaching were effective methods to improve parent–child interactions. Evidence for physical interventions was limited in number and quality and was assessed as low (United States Preventative Task Force UPSTF, Citation2012).

Discussion

RQ1

Though the data available on observations of children with DD in the SSP were still limited, the picture has become clearer that rates of attachment insecurity and disorganization are of concern. The present study highlighted some observations regarding reliability and validity of the SSP for children with DD; gender; functionality; ASD; and Socio-Economic Status (SES).

Reliability and validity: The reliability of using the SSP with children with DD became more apparent with a high degree of consistency found across study results. Validity was supported through similar associations being found in studies of children with DD as in typical populations, for example, security was correlated with maternal sensitivity and disorganization with heart rate variability (Naber, et al., Citation2007; Willemsen-Swinkels, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Buitelaar, van Ijzendoorn, & van Engeland, Citation2000). Furthermore, Capps, Sigman, and Mundy (Citation1994) and Koren-Karie, Oppenheim, Dolev, and Yirmiya (Citation2009) found that higher parental sensitivity provided the most supportive circumstances for secure attachment in children with autism, as was found with children with neurological disorders (Clements & Barnett, Citation2002), children with Down syndrome (Atkinson et al., Citation1999), and typically developing children (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, Citation2003).

Gender: Ganiban, Barnett, and Cicchetti (Citation2000) found that despite only a small majority of males in their study, 17 compared to 13 females, 89% of those classified as disorganized were male (Ganiban, Barnett, & Cicchetti, Citation2000). As more boys are diagnosed with disability than girls, particularly with some diagnoses such as ASD, there were many more males in the selected SSP studies than females, with only 34% female participants. A study involving high-risk dyads (n = 65) found gender differences in toddler behavior in response to both frightening and withdrawn maternal behavior (David & Lyons-ruth, Citation2005). The tendency for girls to show more affiliative behavior toward mothers who were showing frightening behavior to their child led David and Lyons-ruth (Citation2005) to suggest the possibility that girls may be less likely to be classified as disorganized than boys in similar relational circumstances.

Functionality: Rozga et al. (Citation2017) found that secure pre-schoolers with ASD had significantly higher language skills, were more empathic, and made more initiations to their parents (Rozga et al., Citation2017). Similarly, Willemsen-Swinkels, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Buitelaar, van Ijzendoorn, and van Engeland (Citation2000) found that insecure children with PDD showed fewer social initiatives and responses even when matched on chronological and mental age (Willemsen-Swinkels, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Buitelaar, van Ijzendoorn, & van Engeland, Citation2000). Naber, et al., Citation2007 and Willemsen-Swinkels, Bakermans-Kranenburg, Buitelaar, van Ijzendoorn, and van Engeland (Citation2000) found that intellectual disability in combination with ASD and PDD, respectively, was negatively associated with security, whereas Capps, Sigman, and Mundy (Citation1994) and Feniger-Schaal and Joels (Citation2018) found that intelligence was not associated with security.

ASD: Teague, Gray, Tonge, and Newman (Citation2017) found in their review of attachment research on children with ASD that children with more severe ASD symptoms were more likely to have insecure attachment and that children with ASD and an intellectual disability were more likely to be insecure than children with ASD and no intellectual disability (Teague, Gray, Tonge, & Newman, Citation2017). Furthermore, Teague, Gray, Tonge, and Newman (Citation2017) found that deficits in social communication did not prevent attachment from developing but rather influenced the quality of that attachment. ASD symptomology may impact the child’s ability to correctly interpret the parent’s behavior, communicate their needs, and for the parent to accurately interpret these needs (Howe, Citation2006). The creator of RFI noted that there was no empirical basis to suggest that the social-emotional difficulties experienced by children with ASD were caused by insecure attachment (Mahoney & Perales, Citation2003) and this finding was supported by the authors of the current review.

Socio-Economic Status: Though this review focused on patterns of attachment and interventions rather than causes, the comparison of data for children with DD to non-clinical, middle-class data raised additional issues. Socio-demographic stress has been found to negatively impact attachment security perhaps through impacts on parental sensitivity (Booth, Macdonald, & Youssef, Citation2018). As children with DD have been found to be more likely to live in poverty than children without DD (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2004; Emerson, Citation2004; Leonard et al., Citation2005; McLaughlin & Rank, Citation2018); it is possible that the differences in security and disorganization from non-clinical, middle-class samples related to socio-economic circumstances. However, interventions with children in low socio-economic (SES) circumstances have been demonstrated to reduce the likelihood of disorganized attachment (Bakermans-Kranenburg, van IJzendoorn, & Juffer, Citation2003; Facompré, Bernard, & Waters, Citation2018). Therefore, even if SES status rather than DD is the cause, the elevated rate of disorganized attachment among children accessing ECI can and should be addressed. As discussed, research suggests there are other key factors involved such as the emotional impact of the diagnosis on the parents and the state of their resolution to this (Feniger-Schaal & Oppenheim, Citation2013). Interestingly, the one sample in the current meta-analysis of SSP classifications that showed a typical rate of disorganized attachment included only middle-class families (Clements & Barnett, Citation2002). However, just 43.6% of the children were classified as having a secure attachment (Clements & Barnett, Citation2002) which is in keeping with the overall finding of 42.3%.

RQ2

Regarding interventions, this systematic review found emerging evidence that interventions can improve attachment for children with DD. Many of the studies involved adaptions of mainstream interventions for specific disabilities such as ASD or vision impairment. As such, it may be that there will never be a one-size fits all solution, but rather effective elements or principles partnered with the differences of individuals, families, and knowledge of how some disabilities may impact interactions. Cognitive and behavioral interventions demonstrate the strongest evidence, warranting further research to clarify which elements of these interventions are most effective and with whom.

Implications for early childhood intervention

There are two main implications from these findings for ECI. First, the findings from the meta-analysis that fewer than half of the children with DD were classified as secure and that well over a quarter were classified as disorganized should raise concern. The aim of ECI is to enhance the development, wellbeing, and participation of children with DD (Early Childhood Intervention Australia, Citation2016); and insecure and disorganized attachment work against these aims. ECI professionals, have the opportunity to enhance parent–child attachment security thereby supporting positive emotional, behavioral, and mental health outcomes. Second, the findings from the systemic review regarding interventions indicate that ECI professionals seeking to improve parent–child interactions and attachment security should explore cognitive and behavioral strategies. Thus far the strongest evidence available supports approaches using coaching and video feedback. It is recommended that ECI professionals be supported to develop their capacity to promote sensitive and responsive caregiving and to identify when referrals for more intensive support are required.

Best practice in ECI requires an individualized family-centered approach in a child’s natural setting, their home, and their community (Early Childhood Intervention Australia, Citation2016). The majority of the studies included were manualised, center-based, group programs. More research is recommended to further explore attachment interventions and mediators of impacts for this population, to enable ECI professionals to provide individualized support for families within the context of best practice in ECI.

Limitations

The primary limitations of this systematic review relate to the exclusion criteria. One of those limits was not being able to include non-English papers and 34 papers were excluded for this reason. Given only a tiny fraction of the original electronic search (0.4%) were included; it may be that these papers would have been excluded for other reasons. Though the search included gray literature, only peer reviewed papers were included for analysis. Discussion was held among the authors regarding the various merits of a scoping review versus a systematic review, and though a scoping review may have provided a broader picture of available interventions, a systematic review was conducted to limit inclusions to articles with a higher standard of evidence. The downside of the tight inclusion criteria employed is that the number of papers is limited and many of the papers are over 10 years old. Given changes regarding conceptualization and diagnosis of disabilities over the years, this should be considered a limitation. Finally, there is a methodological limitation regarding the included SSP studies and the range in age of participants. Each of the included SSP studies was overt in relation to developmental age and addition to chronological age, but the variability within and between studies should be considered a limitation.

Conclusion

This systematic review was the first undertaken with the purpose of examining attachment research for the field of ECI. While revealing a paucity of data, the review of studies indicated that children with DD were significantly less likely to develop a secure attachment, as measured by the SSP, with around 42% developing a secure attachment compared to 62% or more in population samples. Children with DD were also significantly over-represented in the disorganized category with around 29% classified as disorganized compared to 15% in non-clinical middle-class samples. Given the associations between disorganized attachment and emotional, behavioral, and mental health problems, this over-representation is of considerable concern. Included intervention studies were grouped as cognitive, behavioral, or physical with some interventions spanning across two or more of these descriptors. Though all the included studies demonstrated some positive outcomes, more research is required to make recommendations to ECI professionals around which approaches may work best within the context of their work considering diagnoses, family differences and preferences, and other variances.

Disclosure statement

The authors report no external funding or other conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acquarone, S. (1995). Mens sana in corpore sano: Psychotherapy with a cerebral palsy child aged nine months. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy, 9(1), 41–57. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02668739500700051

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Bell, S. M., & Stayton, D. F. (1974). Infant-mother attachment and social development: Socialization as a product of reciprocal responsiveness to signals. In M. P. M. Richards (Ed.), The integration of a child into a social world (pp. 99–135). Cambridge University Press.

- Ainsworth, M., Blehar, M., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale, N.J.: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Anderson, S., Gooze, R., Lemeshow, S., & Whitaker, R. (2012). Quality of early maternal-child relationship and risk of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics, 129(1), 132. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0972

- Appelbaum, M., Batten, D. A., Belsky, J., Booth, C., Bradley, R., Brownell, C. A., & Weinraub, M. (1999). Child care and mother-child interaction in the first 3 years of life. Developmental Psychology, 35(6), 1399–1413.

- Atkinson, L., Chisholm, V., Scott, B., Goldberg, S., Vaughn, B., Blackwell, J., Tam, F., Dickens, S. (1999). Maternal sensitivity, child functional level, and attachment in Down syndrome. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(3), 45–66. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1540-5834.00033

- Atkinson, L., Paglia, A., Coolbear, J., Niccols, A., Parker, K., & Guger, S. (2000). Attachment security: A meta-analysis of maternal mental health correlates. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(8), 1019–1040. doi:10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00023-9

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2004). Children with disabilities in Australia. Retrieved 12/07/2018 from https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/disability/children-disabilities-australia/contents/highlights

- Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., van IJzendoorn, M., & Juffer, F. (2003). Less is more: Meta-analyses of sensitivity and attachment interventions in early childhood. Psychological Bulletin, 129(2), 195–215. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.129.2.195

- Barendregt, J., Doi, S., Lee, Y., Norman, R., & Vos, T. (2013). Meta-analysis of prevalence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(11), 974. doi:10.1136/jech-2013-203104

- Barnett, D., Clements, M., Kaplan-Estrin, M., Janisee, H., McCaskill, J., Schram, J., Butler, C., Schram, J.L. and Janisse, H.C. (2006). Maternal resolution of child diagnosis: Stability and relations with child attachment across the toddler to preschooler transition. Journal of Family Psychology, 20(1), 100. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.20.1.100

- Bayley, N. (1969). Bayley Scales of Infant Development. New York: Psychological Corp.

- Belsky, J., & Fearon, P. (2002). Infant-mother attachment security, contextual risk, and early development: A moderational analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 14(2), 293–310. doi:10.1017/S0954579402002067

- Bernier, A., Carlson, S., Deschenes, M., & Matte-Gagne, C. (2012). Social factors in the development of early executive functioning: A closer look at the caregiving environment. Developmental Science, 15(1), 12–24. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01093.x

- Booth, A., Macdonald, J., & Youssef, G. (2018). Contextual stress and maternal sensitivity: A meta-analytic review of stress associations with the Maternal Behavior Q-Sort in observational studies. Developmental Review, 48, 145–177. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2018.02.002

- Bowlby, J. (1982a). Attachment, 2ndVol. 1. New York: Basic Books. 1969

- Bowlby, J. (1982b). Loss, sadness and depression. (Vol. 3). New York: Basic Books. 1969

- Brisch, K., Bechinger, D., Betzler, S., & Heinemann, H. (2003). Early preventive attachment-oriented psychotherapeutic intervention program with parents of a very low birthweight premature infant: Results of attachment and neurological development. Attachment & Human Development, 5(2), 120–135. doi:10.1080/1461673031000108504

- Capps, L., Sigman, M., & Mundy, P. (1994). Attachment security in children with autism. Development and Psychopathology, 6(2), 249–261. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400004569

- Carlson, E. (1998). A prospective longitudinal study of attachment disorganization/disorientation. Child Development, 69(4), 1107–1128. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1998.tb06163.x

- Cassidy, J., Jones, J., & Shaver, P. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development & Psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 2), 1415–1434. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000692

- Charpak, N., Tessier, R., Ruiz, J., Hernandez, J., Uriza, F., Villegas, J., Maldonado, D., Nadeau, L., Mercier, C., Maheu, F., Marin, J. and Cortes, D., (2017). Twenty-year follow-up of Kangaroo Mother Care versus traditional care. Pediatrics, 139(1), 01. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2063

- Chiarello, L., & Palisano, R. (1998). Investigation of the effects of a model of physical therapy on mother-child interactions and the motor behaviors of children with motor delay. Physical Therapy, 78(2), 180–194. doi:10.1093/ptj/78.2.180

- Clements, M., & Barnett, D. (2002). Parenting and attachment among toddlers with congenital anomalies: Examining the Strange Situation and Attachment Q-sort. Infant Mental Health Journal, 23(6), 625–642. doi:10.1002/imhj.10040

- Cullen-Powell, L., Barlow, J., & Cushway, D. (2005). Exploring a massage intervention for parents and their children with autism: The implications for bonding and attachment. Journal of Child Health Care, 9(4), 245–255. doi:10.1177/1367493505056479

- David, D., & Lyons-ruth, K. (2005). Differential attachment responses of male and female infants to frightening maternal behavior: Tend or befriend versus fight or flight? Infant Mental Health Journal, 26(1), 1–18. doi:10.1002/imhj.20033

- Deeks, J., Higgins, J., & Altman, D. (2017). Analysing data and undertaking meta-analyses. In J. Higgins, R. Churchill, J. Chandler, & M. Cumpston (Eds.), Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions (version 5.2.0 (updated June 2017) ed.). Cochrane. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook

- DerSimonian, R., & Laird, N. (1986). Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clinical Trials, 7(3), 177–188. doi:10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2

- Dunst, C. (2007). Early intervention for infants and toddlers with developmental disabilities. In S. Odom, R. Horner, M. Snell, & J. Blacher (Eds.), Handbook of developmental disabilities (pp. 161-180). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Early Childhood Intervention Australia. (2016). National guidelines: Best practice in early childhood intervention. Retrieved 12/01/2017, from https://www.ecia.org.au/Resources/National-Guidelines-for-Best-Practice-in-ECI

- Emerson, E. (2004). Poverty and children with intellectual disabilities in the world’s richer countries. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 29(4), 319–338. doi:10.1080/13668250400014491

- Facompré, C., Bernard, K., & Waters, T. (2018). Effectiveness of interventions in preventing disorganized attachment: A meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 30(1), 1–11. doi:10.1017/S0954579417000426

- Fardoulys, C., & Coyne, J. (2016). Circle of Security intervention for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 37, 572–584. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1193

- Fardoulys, C., & Coyne, J. (2016a). Circle of Security intervention for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 37(4), 572–584. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1193

- Fardoulys, C., & Coyne, J. (2016b). Circle of Security intervention for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 37(4), 572–584. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1193

- Farran, D., Kasari, C., Comfort, M., & Jay, S. (1986). Parent/caregiver interaction scale. Unpublished manuscript, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Department of Child Development and Family Relations.

- Fearon, P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., van Ijzendoorn, M., Lapsley, A., & Roisman, G. (2010). The significance of insecure attachment and disorganization in the development of children’s externalizing behavior: A meta-analytic study. Child Development, 81(2), 435–456. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01405.x

- Fearon, P., & Belsky, J. (2016). Precursors of attachment security. In J. Cassidy & P. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment (Third) (pp. 291-313). New York: The Guilford Press.

- Feniger-Schaal, R., & Joels, T. (2018). Attachment quality of children with ID and its link to maternal sensitivity and structuring. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 76, 56–64. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.03.004

- Feniger-Schaal, R., & Oppenheim, D. (2013). Resolution of the diagnosis and maternal sensitivity among mothers of children with intellectual disability. Research in Developmental Disabilities: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 34(1), 306–313. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2012.08.007

- Ganiban, J., Barnett, D., & Cicchetti, D. (2000). Negative reactivity and attachment: Down syndrome’s contribution to the attachment-temperament debate. Development and Psychopathology, 12(1), 1–21. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0954579400001012

- Granqvist, P., Sroufe, A., Dozier, M., Hesse, E., Steele, M., Van Ijzendoorn, M., Duschinsky, R., Solomon, J., Schuengel, C., Fearon, P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. and Steele, H. (2017). Disorganized attachment in infancy: A review of the phenomenon and its implications for clinicians and policy-makers. Attachment & Human Development, 1–25. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1354040

- Groh, A., Fearon, P., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Van Ijzendoorn, M., Steele, R., & Roisman, G. (2014). The significance of attachment security for children’s social competence with peers: A meta-analytic study. Attachment & Human Development, 16(2), 103–136. doi:10.1080/14616734.2014.883636

- Grzadzinski, R., Luyster, R., Gunn Spencer, A., & Lord, C. (2014). Attachment in young children with autism spectrum disorders: An examination of separation and reunion behaviours with both mothers and fathers. Autism, 18(2), 85–96. doi:10.1177/1362361312467235

- Guralnick, M. (2005). An overview of the developmental systems model for early intervention. In Guralnick, Michael, (Ed.), The developmental systems approach to early intervention (pp. 3-28). Baltimore, MD London: H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Hamadi, L., & Fletcher, H. (2021). Are people with an intellectual disability at increased risk of attachment difficulties? A critical review. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 25(1), 114–130. doi:10.1177/1744629519864772

- Hansen, R., & Ulrey, G. (1988). Motorically impaired infants: Impact of a massage procedure on caregiver-infant interactions. Journal of the Multihandicapped Person, 1(1), 61–68. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF01110556

- Higgins, J., Altman, D., Gotzsche, P., Juni, P., Moher, D., Oxman, A., Group, C. S. M., Savović, J., Schulz, K.F., Weeks, L. and Sterne, J.A. (2011). The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 343 oct18 2, d5928–d5928. 10.1136/bmj.d5928

- Howe, D. (2006). Disabled children, parent-child interaction and attachment. Child Family Social Work, 11(2), 95–106. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00397.x

- Innocenti, M., Roggman, L., & Cook, G. (2013). Using the PICCOLO with parents of children with a disability. Infant Mental Health Journal, 34(4), 307–318. doi:10.1002/imhj.21394

- The Joanna Briggs Institute. (2013). JBI levels of evidence. https://jbi.global/sites/default/files/2019-05/JBI-Levels-of-evidence_2014_0.pdf

- Kim, J. M., & Mahoney, G. (2004). The effects of mother's style of interaction on children's engagement: Implications for using responsive interventions with parents. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 24(1), 31–38.

- Kim, J., & Mahoney, G. (2005). The effects of relationship focused intervention on Korean parents and their young children with disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 26(2), 117-130. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2004.08.001

- Koren-Karie, N., Oppenheim, D., Dolev, S., & Yirmiya, N. (2009). Mothers of securely attached children with autism spectrum disorder are more sensitive than mothers of insecurely attached children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 50(5), 643–650. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02043.x

- Lederberg, A., & Mobley, C. (1990). The effect of hearing impairment on the quality of attachment and mother-toddler interaction. Child Development, 61(5), 1596–1604. doi:10.2307/1130767

- Leonard, H., Petterson, B., De Klerk, N., Zubrick, S., Glasson, E., Sanders, R., & Bower, C. (2005). Association of sociodemographic characteristics of children with intellectual disability in Western Australia. Social Science & Medicine, 60(7), 1499–1513. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.014

- Maclean, M., Sims, S., Bower, C., Leonard, H., Stanley, F., & O’donnell, M. (2017). Maltreatment risk among children with disabilities. Pediatrics, 139(4), 1–12. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1817

- Madigan, S., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Van Ijzendoorn, M., Moran, G., Pederson, D., & Benoit, D. (2006). Unresolved states of mind, anomalous parental behavior, and disorganized attachment: A review and meta-analysis of a transmission gap. Attachment & Human Development, 8(2), 89–111. doi:10.1080/14616730600774458

- Mahoney, G., & Perales, F. (2003). Using Relationship-Focused Intervention to enhance the social-emotional functioning of young children with autism spectrum disorders. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(2), 74–86. doi:10.1177/02711214030230020301

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1986). Discovery of a new, insecure-disorganized/disoriented attachment pattern. In T. Brazelton & M. Yogman (Eds.), Affective Development in Infancy (pp. 95–124). Norwood, New Jersey: Ablex.

- Malekpour, M. (2007). Effects of attachment on early and later development. The British Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 53(105), 81–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/096979507799103360

- Martin, K., Haltigan, J., Ekas, N., Prince, E., & Messinger, D. (2020). Attachment security differs by later autism spectrum disorder: A prospective study. Developmental Science, 23(5), e12953–e12953. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12953

- McLaughlin, M., & Rank, M. (2018). Estimating the economic cost of child poverty in the United States. Social Work Research, 42(2), 73–83. doi:10.1093/swr/svy007

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. The BMJ, 339(7716), b2535–b2535. doi:10.1136/bmj.b2535

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., & Petticrew, M., & … Stewart, L. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1–9. doi:10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Moore, T. (2012, August 9). Rethinking early childhood intervention services: Implications for policy and practice (Paper presentation) 10th Biennial National Conference of Early Childhood Intervention Australia, 1st Asia-Pacific Early Childhood Intervention Conference, Perth, Western Australia. www.rch.org.au/uploadedFiles/Main/Content/ccch/profdev/ECIA_National_Conference_2012.pdf

- Naber, F., Swinkels, S., Buitelaar, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Ijzendoorn, M., Dietz, C., van Daalen, H.E., Engelandvan Daalen, H.E. (2007). Attachment in toddlers with autism and other developmental disorders. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(6), 1123–1138. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0255-2

- National Disability Insurance Agency. (2019). Access to the NDIS - Early Intervention. Retrieved 01/03/2019 from https://www.ndis.gov.au/about-us/operational-guidelines/access-ndis-operational-guideline/access-ndis-early-intervention-requirements

- Nyaga, V., Arbyn, M., & Aerts, M. (2014). Metaprop: A Stata command to perform meta-analysis of binomial data. Archives of Public Health, 72(1), 72(1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/2049-3258-72-39

- Odom, S., & Wolery, M. (2003). A unified theory of practice in Early Intervention/Early Childhood Special Education: Evidence-based practices. The Journal of Special Education, 37(3), 164–173. doi:10.1177/00224669030370030601

- Pipp-Siegel, S., Siegel, C., & Dean, J. (1999). Neurological aspects of the disorganized/disoriented attachment classification system: Differentiating quality of the attachment relationship from neurological impairment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 64(3), 25–44. doi:10.1111/1540-5834.00032

- Platje, E., Sterkenburg, P., Overbeek, M., Kef, S., & Schuengel, C. (2018). The efficacy of VIPP-V parenting training for parents of young children with a visual or visual-and-intellectual disability: A randomized controlled trial. Attachment & Human Development, 20(5), 455–472. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2018.1428997

- Poslawsky, I., Naber, F., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Daalen, E., Engeland, H., & van IJzendoorn, M. (2015). Video-feedback Intervention to promote Positive Parenting adapted to autism (VIPP-AUTI): A randomised control trial. Autism, 19(5), 588–603. doi:10.1177/1362361314537124

- Puig, J., Englund, M., Simpson, J., & Collins, W. (2013). Predicting adult physical illness from infant attachment: A prospective longitudinal study. Health Psychology, 32(4), 409–417. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0028889

- Rozga, A., Hesse, E., Main, M., Duschinsky, R., Beckwith, L., & Sigman, M. (2017). A short-term longitudinal study of correlates and sequelae of attachment security in autism. Attachment & Human Development, 20(2), 160–180. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2017.1383489

- Rutgers, A., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., van IJzendoorn, M., & van Berckelaer-Onnes, I. (2004). Autism and attachment: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(6), 1123–1134. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.t01-1-00305.x

- Schwarzer, G., Chemaitelly, H., Abu-raddad, L., & Rücker, G. (2019). Seriously misleading results using inverse of Freeman-Tukey double arcsine transformation in meta-analysis of single proportions. Research Synthesis Methods, 10(3), 476–483. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1348

- Sealy, J., & Glovinsky, I. (2016). Strengthening the reflective functioning capacities of parents who have a child with a neurodevelopmental disability through a brief, relationship-focused intervention. Infant Mental Health Journal, 37(2), 115–124. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21557

- Seifer, R., Clark, G., & Sameroff, A. (1991). Positive effects of interaction coaching on infants with developmental disabilities and their mothers. American Journal of Mental Retardation: AJMR, 96(1), 1–11.

- Seifer, R., Clark, G. N., & Sameroff, A. J. (1991). Positive effects of interaction coaching on infants with developmental disabilities and their mothers. American Journal on Mental Retardation.

- Siller, M., Swanson, M., Gerber, A., Hutman, T., & Sigman, M. (2014). A parent-mediated intervention that targets responsive parental behaviors increases attachment behaviors in children with ASD: Results from a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(7), 1720–1732. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2049-2

- Solomon, R., Van Egeren, L., Mahoney, G., Quon Huber, M., & Zimmerman, P. (2014). PLAY Project Home Consultation intervention program for young children with autism spectrum disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 35(8), 475–485. doi:10.1097/dbp.0000000000000096

- Sroufe, L. (2005). Attachment and development: A prospective, longitudinal study from birth to adulthood. Attachment & Human Development, 7(4), 349–367. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616730500365928

- StataCorp. (2017). Stata Statistical Software: Release 15. In TX: StataCorp LLC.

- Teague, S., Gray, K., Tonge, B., & Newman, L. (2017). Attachment in children with autism spectrum disorder: A systematic review. Research in Autism Spectrum Disorders, 35, 35–50. doi:10.1016/j.rasd.2016.12.002

- Thompson, S., & Higgins, J. (2002). How should meta-regression analyses be undertaken and interpreted? Statistics in Medicine, 21(11), 1559–1573. doi:10.1002/sim.1187

- United States Preventative Task Force (UPSTF). (2012). Grade Definitions. Retrieved 20 January 2023 from https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf/methods-and-processes/grade-definitions

- Vandell, D. L. (1979). Effects of a playgroup experience on mother–son and father–son interaction. Developmental Psychology, 15(4), 379.

- van den Broek, E., van Eijden, A., Overbeek, M., Kef, S., Sterkenburg, P., & Schuengel, C. (2017). A systematic review of the literature on parenting of young children with visual impairments and the adaptions for Video-Feedback Intervention to Promote Positive Parenting (VIPP). Journal of Developmental and Physical Disabilities, 29(3), 503–545. doi:10.1007/s10882-016-9529-6

- Vandesande, S., Bosmans, G., Schuengel, C., & Maes, B. (2019). Young children with significant developmental delay differentiate home observed attachment behaviour towards their parents. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 32(1), 106. doi:10.1111/jar.12513

- van IJzendoorn, M., Goldberg, S., Kroonenberg, P., & Frenkel, O. (1992). The relative effects of maternal and child problems on the quality of attachment: A meta-analysis of attachment in clinical samples. Child Development, 63(4), 840–858. doi:10.2307/1131237

- van Ijzendoorn, M., Schuengel, C., & Bakermanskranenburg, M. (1999). Disorganized attachment in early childhood: Meta-analysis of precursors, concomitants, and sequelae. Developmental Psychopathology, 11(2), 225–250. doi:10.1017/S0954579499002035

- Vaughn, B., Goldberg, S., Atkinson, L., Marcovitch, S., MacGregor, D., & Seifer, R. (1994). Quality of toddler-mother attachment in children with Down syndrome: Limits to interpretation of Strange Situation behavior. Child Development, 65(1), 95–108. doi:10.2307/1131368

- Veroniki, A., Jackson, D., Viechtbauer, W., Bender, R., Bowden, J., Knapp, G., Higgins, J.P., Langan, D. and Salanti, G., (2016). Methods to estimate the between-study variance and its uncertainty in meta-analysis. Research Synthesis Methods, 7(1), 55–79. doi:10.1002/jrsm.1164

- Veroniki, A., Jackson, D., Viechtbauer, W., Bender, R., Knapp, G., Kuss, O., & Langan, D. (2015). Recommendations for quantifying the uncertainty in the summary intervention effect and estimating the between-study heterogeneity variance in random-effects meta-analysis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 25–27. https://core.ac.uk/reader/80809277

- Willemsen-Swinkels, S., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., Buitelaar, J., van Ijzendoorn, M., & van Engeland, H. (2000). Insecure and disorganised attachment in children with a Pervasive Developmental Disorder: Relationship with social interaction and heart rate. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 41(6), 759–767. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00663