Abstract

In this paper, a teacher educator discusses her experience of professional learning through self-study. The author found the transition between being a classroom teacher and teacher educator challenging, as has been noted in recent literature. Thus, she decided to embark on a self-study, which was focused on the enhancement of her teaching so that she was not merely transmitting knowledge to her students about the teaching of literacy. Data was gathered using a range of qualitative methods including reflective journals, peer observations, and student focus groups. Themes emerged from the data relating to the importance of activating prior knowledge in learning, the necessity of creating dynamic lecturing spaces and the need to share learning while learning in a university lecture hall. As a self-study, this paper is highly contextual but is intended to provide valuable insights into teaching and learning in higher education.

Introduction

Until recently, the professional development of teacher educators stood at the periphery of educational research (Berry Citation2009). The dearth of research in this area is related to the lack of recognition that teaching about teaching is a form of specialised expertise which cannot be assumed (Murray and Male Citation2005). Teaching about teaching is markedly different from teaching in many ways and thus requires some form of professional development if one is to transition successfully from classroom teacher to teacher educator (Berry Citation2008, Ritter Citation2017). S-STEP (self-study of teaching and teacher education practices) is a research methodology that could ‘potentially have the greatest impact on teacher education and transformation of practice’ (Tidwell et al. Citation2009, p. 53). Self-study involves the intentional, systematic reflection on one’s practice in order to develop and improve it (Loughran Citation2007). It has evolved from recent research which emphasised the understanding that teaching is a discipline rather than simply a means to transmit knowledge from teacher to learner (King et al. Citation2019; Loughran & Russell, Citation2007). I embarked on this self-study out my own ‘felt need’ (Elliot Citation1991, p. 53) to problematise and deconstruct my teaching with a view to enhance my practice, in order to construct a pedagogy of teacher education that would go beyond simply transmitting best classroom practices to my student teachers (Bullock Citation2009). In this paper, I share my learning journey that I experienced as a result of my self-study with the intention of making my ‘private struggle’ of teaching teachers of literacy public (Berry Citation2008, p. 9) for the benefit of my students, my own practice and other teacher educators.

Context for the research

My ‘ontogenesis’ (Wertsch Citation1985) as a teacher educator, along with other varied professional experiences, led me to regularly note that, despite the enthusiasm that I had for my teaching, I felt that I had a tendency to transmit information rather than transform my student’s understanding of teaching methodologies. At the start of this study I had been lecturing both in Ireland and in New York for over seven years. I was also an experienced primary school teacher with a decade of teaching experience at that level. I had taken up a new position at the university a few months prior to beginning the study and I felt that I wanted to improve my practice and strengthen student engagement, particularly when teaching larger groups. I was working in a large education department within a university in the Republic Ireland where student groups ranged from ten to four hundred and fifty. The larger group sizes were a particular concern at the outset of the study as engagement can be challenging in such a setting. Working with large numbers also encouraged and sustained the ‘pedagogy of presentation’ (Berry Citation2008) that I hoped to overcome through self-study. This teaching context had led me to identify two key research questions:

How am I teaching?

How can I improve my teaching?

Self-study was deemed an appropriate lens in which to explore these research questions as it has been used by other university lecturers in similar contexts successfully in the past (see for example Berry Citation2008, Bullock Citation2009).

Discussion of the literature

This study aimed to enhance my teaching as a teacher educator through self-study. According to Loughran and Russell (Citation2007, p.223), ‘teacher educators must deliberately and carefully craft their teaching in ways that are explicit for themselves and their students of teaching. However, this can be complex, as according to Korthagen et al. (Citation2001, p. 22), “what seems obvious to the teacher educator is not so to the student teacher. What to us seems directly applicable in practice, seems to be too abstract, too theoretical and too far off for someone else”. Therefore, thought must be given to students’ perceptual lens which may be quite different to that of their teacher educator.

As a core subject at both primary and secondary school level, pre-service teachers have experienced a long ‘apprenticeship of observation’ (Lortie, Citation1975) with literacy as pupils. Notions of ‘teaching as transmission’ in relation to literacy can mask its incredible complexity (Loughran & Russell, Citation2007, p.217). Their untrained eye as a young pupil would not have unpacked the skilful planning, responsiveness and adaptation aligned with theory that created effective literacy learning experiences. Instead, they may have developed a notion that teaching literacy is straightforward process. Unfortunately, ‘there is never a simple teaching recipe that works’ (Loughran & Russell, Citation2007, p.221), as teaching is ultimately complex and multi-faceted in nature (Jackson Citation1968).

In addition, despite significant advances in literacy policy and pedagogy, implementation in classrooms is slow and as a result, student teachers encounter research-based best practice in literacy methods class that they have never experienced as pupils. This creates a cognitive dissonance that can be difficult to overcome (Festinger Citation1957). Thus, opportunities to explore and refine their perceptions and beliefs through reflection is an essential component of effective teacher preparation (Korthagen et al. Citation2001). In order to achieve conceptual change, teacher educators need to challenge students’ existing beliefs and take ownership of new learning within a positive supporting environment (Grierson Citation2010). Therefore, students should be encouraged to draw on their existing knowledge in order to explore how new learning might fit with prior experiences and current expectations. Teaching teachers needs to be an interactive, reflective process that enables pre-service teachers to think deeply about instructional methodologies and teaching decisions. Indeed, ‘adults do not learn from experience, they learn from processing experience’ Arin-Krupp, (1995, in Garmston and Wellman Citation1999). Challenging students’ beliefs can have a significant effect on learning as Kegan and Lahey contend (1984, in Drago-Severson Citation2004) ‘people do not grow by having their realities only confirmed. They grow by having them challenged as well, and being supported to listen to, rather than defend against, that challenge’ (p.226). It is through the active construction and re-construction of one’s beliefs that teachers are enabled to take ownership of new knowledge and new practices (Dewey Citation1963). Therefore, a teacher preparation programme in literacy should attempt to adhere to Vygotskian principles (Vygotsky Citation1978) with regard to the principle of taking the pre-service teacher from the known to the unknown with careful scaffolding while also allowing the learner to actively construct their own knowledge (Bruner Citation1986).

It is also important to consider that our intended pedagogy can often be distorted by students’ prior experiences and beliefs. Our teaching can be misinterpreted as we can ‘not be sure that one’s actions will convey the meaning they were intended to have for students’ (Kelchtermans Citation2005, p. 998). Indeed, Berry (Citation2009) highlights the challenge presented to university lecturers in sharing knowledge about teaching with students, as it cannot be simply transferred or transmitted, but must be explicitly demonstrated and transformed by the learner (Loughran & Russell, Citation2007). According to Freire (Citation1972), ‘to learn is to construct, to reconstruct, to observe with a view to changing’. Jonassen and Rohrer-Murphy (Citation1999) agree that conscious learning comes from activity. While hands-on tasks are an obvious manifestation of active learning, a lecture can also be active in nature if presented appropriately so that the learner can actively construct and reconstruct knowledge while listening. The use of peer discussion and personal response systems can help to effectively engage large groups in the lecture hall (Ashwin et al. Citation2015). Jeanne (Citation1990) recommends starting each session with a recap, a short quiz or a discussion on prior knowledge in order to enrich the learning experience. Scaffolding learning (Vygotsky Citation1978) through asking questions related to problems, case studies or examples can help the learner process the material in an individualised manner which can then be further unpacked as a group. These formative assessment tools might enable the learning to become more visible (Hattie Citation2012) as it provides feedback to the lecturer on the depth of students understanding, while also allowing for authentic opportunities for students to rehearse knowledge and skills, support and scaffolding from the teacher and responsive feedback (McDowell et al. Citation2010).

While subject expertise is essential in teaching teachers (Ashwin et al. Citation2015), Rowland, S (Citation2005) also emphasises the need for a lecturer to love their subject, while McArthur (Citation2009), contends that a love of sharing one’s subject knowledge is also critical. This disposition helps to communicate to students that the knowledge ‘matters’ (Andrews et al. Citation1996). Indeed, Knowles (Citation1988), emphasises that adult learners need to know the intent and goal behind what they are learning and this is a central tenet of andragogy. However, it is important to consider that the students on a teacher preparation programme exist within a complex ecological system (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979). While being enthusiastic and energetic as a lecturer is important in inspiring learners, it is necessary to balance this ‘excited engagement’ with the understanding that it is not always true that ‘through some sort of pedagogic osmosis’, the students ‘will absorb our level of interest’ (Brookfield Citation2017, p. 41). Motivating students, is desirable but it is also essential to understand that other factors, such as personal histories, experiences, and beliefs might affect learning and that the lecturer is not always the direct cause of disengagement of behalf of the learner (Brookfield Citation2017). Indeed, according to Brookfield (Citation2017), the ‘assumption that teachers can create motivated students by the power of their charismatic energy is deeply harmful’ (p.44) as it places ‘all the responsibility for creating a motivated learner’ on ‘the teacher’s shoulders’ (p.42). When we consider Plato's (Citation1970) notion that one cannot change someone’s ingrained behaviour, though reflection on this behaviour might be possible; it is important to recognise the limitations of one’s teaching.

Rodgers (Citation1994) emphasises the importance of a positive climate or rapport in effective learning situations in developing students’ engagement. Anxiety around achievement and knowledge and comfort within the lecturing space may impact students’ ability to ask or answer questions in the classroom (Hargreaves Citation2015). Failure to partake in questioning or an absence of opportunities to do so, can lead to disengagement (Ashton and Stone Citation2018). Therefore, a classroom culture of knowledge exchange needs to be established in order to promote learning.

Ensuring a positive and effective learning environment can be challenging in a large lecturing space with a large group of students. Teacher education is complex as teaching teachers involves more than simply telling which is unfortunate as it is a ‘powerfully seductive notion that can be extremely difficult to resist’ (Berry Citation2008, p. 34) as a university lecturer placed behind a lectern in a tiered lecture theatre. Indeed, Louie et al (Citation2002), has highlighted the dissonance between a lecturer’s ‘cognitive sense of good teaching strategies’ and one’s ‘emotional tie to lecturing’ (p.203). A ‘pedagogy of presentation’ (Berry Citation2008) will not allow students to access the tacit decisions involved in teaching which are the bedrock of understanding how teaching ‘works’. Therefore, in the lecture environment, it might be helpful to consider Hebb’s (Citation1959) theory of associative learning, which points to the usefulness of metaphors, stories and analogies to engage learners and to assist them in making meaningful connections between prior knowledge and new learning. According to Rodgers and Freiberg (Citation1994), sharing stories and personal experiences can humanise your lecture and help to develop rapport with your learners. When creating presentations for a large group lecture, it should have a clear and logical structure, to enable understanding (Smith Citation1999). Visual imagery can support explanations of content (Sadoski and Paivio Citation2001), particularly for visual learners. Miller’s (Citation1956) work on mental processes should also contribute to the learning process. Miller (Citation1956) revealed that humans have a limit on how much information they can process at any one time. He found that generally, seven pieces of information can be held in working memory at a time and this has implications to the amount of content a lecturer should cover and also how that content might be presented. Miller’s theory laid the foundation for subsequent work on cognitive load theory (Sweller et al. Citation1998) which delineated the usefulness of sharing worked examples with learners rather than expecting problem solving when the material to be learned is very unfamiliar. Cognitive load theory may assist a lecturer in making decisions about how information might be presented.

Having considered the literature in relation to the discipline of teaching, I became even more aware of the challenges facing teacher educators. Despite large classes, significant volumes of content and the sheer complexity of the teaching matter, it was essential that I motivate, engage and involve my students in active learning that would enable them to understand how to teach literacy effectively in the primary school. It was clear that I needed to really teach, and not merely transmit information. Therefore, self-study appeared essential to my professional development so that I would come to understand how to enhance my teaching of teachers.

Methodology

This study employed a self-study approach (Zeichner Citation2007). The purpose of using this methodology in this study was to enable deep reflection on the process of teaching teachers through a ‘clear and explicit focus on the self-in-practice’ (Fletcher et al. Citation2016, p. 303). It builds on Schön’s (Citation1983) important work on the reflective practitioner; which generated interest in the notion of ‘knowing-in-action’; the tacit knowledge that is implicit in teaching which is essential for a deep understanding of pedagogy for pre-service teachers. Self-study is deemed an appropriate methodology for this study as it focuses on the ‘concerns of teaching and the development of knowledge about practice and the development of learning’ (Berry Citation2008, p. 6). This self-study aimed to capture the ‘dilemmas, frustrations and moments of success’ (Fletcher et al. Citation2016) which might serve to expand the knowledge base in relation to teacher education practices. The self-study was socially and contextually located within an institute of Education in a university located in the Republic of Ireland. It conducted over two semesters in the academic year 2018/19. At that time I was teaching core literacy modules on a Masters’ Programme in literacy, a Professional Master in Education Programme (PMEP), and a Batchelor of Education programme (B.Ed). Student cohorts ranged from 10 students on the Masters’ programme, 70 on the PMEP and 450 on the B.Ed. programme.

S-STEP methodology generally uses multiple qualitative methods to collect relevant data to allow for sustained, careful inquiry that is trustworthy (Berry Citation2008). In this study, the following research tools (see below) were used in order to enable me to ‘stand in and outside’ myself (Brookfield Citation2017, p. 17):

an autobiographical account of my experiences as a teacher and a learner.

the use of critical friends in peer observations of teaching

My reflective journal

Student focus groups

Table 1. Data collection methods/codes.

An autobiography was used as a baseline to uncover influences on my teaching beliefs, philosophy, and assumptions about literacy teaching and learning (Berry Citation2008). This tool allowed me to analyse my current practices, assumptions, experiences, and philosophy prior to collecting other data through the use of concrete examples that led to insights that could serve as a lens to focus on potential changes to practice (Bullough and Gitlin Citation2001). According to Brookfield (Citation2017), ‘unexamined common sense … is a notoriously unreliable guide to action’. Therefore, thoroughly investigating one’s assumptions at the outset of a self-study is advisable (Berry Citation2008).

As interactivity has been regarded as a ‘core feature’ (Fletcher et al. Citation2016, p. 303) of self-study methodology, structured conversations with critical friends enabled me to explore the foundations of beliefs and practices in a more objective manner while also exploring any contradictions and limitations inherent in practice. Critical friends were used throughout the data collection process to provide alternative interpretations of data and to challenge assumptions while developing shared understandings (Vanassche and Kelchtermans Citation2015). The critical friends used in this study ranged from a mentor from another department assigned to me as part of a newly appointed staff mentoring programme within the university, a colleague who taught similar modules in literacy, and a member of the teaching enhancement unit within the university. These critical friends were invited to observe my teaching and then discuss their observations. Brookfield (Citation2017) recommends using structured conversations with colleagues in self-study as they often give an insight into what part of our practice needs closer scrutiny, may confirm or negate our current assumptions about practice, increase our awareness of tacit knowledge that was not made explicit or suggest new possibilities for teaching and learning.

Reflective journal writing is an important reflective tool as it allows for an exploration of experience that is outside the experience (Kamler Citation2001). The articulation of beliefs and practices in a journal acted as the foundation for structured conversations with critical friends throughout the self-study process. The journal aimed to capture both ‘reflection-in-action’ and ‘reflection-on-action’ (Schön Citation1983), taking account of adaptations made during teaching, while also reflecting on the insights gained from the process at a later time . I gathered a number of artefacts from each class, including students’ work, response logs, exit slips and evaluations to aid my reflection. I developed a journal prompt template based on the aspects of my practice I wished to explore (see ).

Table 2. Examples of journal prompts.

Student focus groups were used to investigate the students’ experiences of being taught how to teach literacy (Berry Citation2008). An open invitation was issued to all students taught by the researcher in the first semester of the academic year 2018–19 and two focus groups were conducted in the second semester. Ethical clearance was granted by the university ethical review board. Verbal and written consent to record and use the interviews was obtained and all participants were assured of anonymity.

Data Analysis

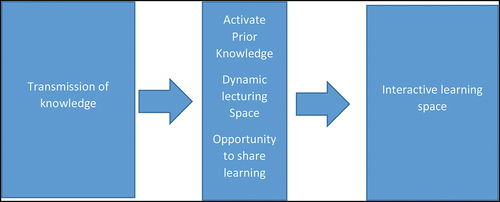

This study employed inductive, thematic analysis methods in which emergent patterns and themes were identified (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Triangulation across the different data sources ensured the trustworthiness of the data within a self-study. I began by analysing my autobiography, searching for the significance in each point in relation to my assumptions and experiences in relation to teaching and learning. From there, I began to code each thought/insight from my reflective journal notes and observation notes provided by my critical friends. Using a ‘constant comparative approach’ (Miles and Huberman Citation1994), the themes began to emerge (Bryman Citation2004). The themes included the importance of prior knowledge and experiences, dynamic lecturing spaces and opportunities to share understandings. I then sought to explore these themes in more detail in the student focus groups. These themes illustrate the movement from a transmission approach to a more interactive learning space and can be seen in below.

Findings and discussion

The importance of activating prior knowledge

This self-study sought to investigate my practice as a teacher educator. The first theme that emerged from the data focused the importance of prior knowledge and experiences in relation to teaching and learning. I came to realise that a dissonance existed between my beliefs, dispositions and expectations towards literacy teaching and learning and that of my students. At the beginning of the study, I conducted an autobiographical account of my own experiences as a teacher and learner of literacy. It revealed some assumptions that I held about my students that potentially limited my teaching in a number of ways (Berry Citation2009; Keltchermans, 2005). I assumed that the students were simply ‘younger versions of myself’ (Trumbull Citation2004, p. 1221) as I had completed the same degree programme that I currently teach. However, my autobiography revealed that I had exceptionally positive experiences with literacy in my home as a child, as my parents were very eager to establish a joyful connection to reading and writing from an early age. Indeed, I noted that ‘a favourite game we played when I was eight or nine years of age was library. We spent hours creating tickets for all our books and categorising them in different ways’ (A, p.1). Reflecting on my own experiences highlighted that ‘not all students will have grown up in houses that valued literacy so much. They may have had negative experiences or a lack of experiences’ (A, p.1). Therefore, I entered the semester mindful of the potential dissonance between my own experience of literacy learning and that of my students and the effect that this could have on the dynamics of teaching and learning (Berry Citation2008). Indeed, the student focus groups illustrated my concerns, for example, one student remarked ‘I was afraid to say I liked reading. I used to be made go to the library and be embarrassed’ (FG1, p.4). Another stated that ‘reading was just a task to be done’ (FG2, p.5). Hence, my perception of literacy could potentially be markedly different from that of my students which can make teaching and learning more challenging. My reflective journal highlighted an increased effort to include opportunities to ‘unpack’ the students’ prior knowledge and experiences in relation to the different topics under study with a view to exploring their ‘apprenticeship of observation’ (Lortie, 1978). I noted that this exploration was ‘informative’ as it ‘provided me with an insight into their experiences’ when we discussed positive and negative memories of becoming literate in school (RJ, W1). Drawing on their past experiences also provided a springboard for discussion around the implementation of new methodologies as we moved through the semester, challenging their existing beliefs (Grierson Citation2010). It proved to be a powerful way to encourage the students to try new methodologies rather than to regress and simply teach the way they were taught themselves on placement (Festinger Citation1957).

My autobiography also reminded me that I was always an extremely enthusiastic student. I enjoyed attending literacy lectures while at college and was extremely eager to learn about teaching literacy (A, p.5). On reflection, it became apparent that not all of my students shared this vision (similar to the experience of Berry’s 2009 self-study). I noted regularly in my reflective journal that many students struggled to stay engaged. Their previous experiences learning literacy may have influenced this disengagement. However, in week four I began to accept that some aspects of student engagement are beyond the lecturer’s control (Plato Citation1970, Brookfield Citation2017), when I recorded in my reflective journal that ‘on the way to the workshop in the elevator with a group of students who didn’t realise that I would be teaching the workshop- one commented, “Oh, I am so not in the mood for this class, I’m really hungry”. It didn’t bode well for the class’ (RJ, W4). Therefore, the disconnect between my vision related to literacy learning was often at odds with the expectations and dispositions of my students.

As a teacher educator, I have a deep knowledge of literacy practices, enjoying early success as a literacy teacher in primary school classrooms where I spent over a decade. I also had spent almost a decade teaching at university level. On examining my reflective journals, it became apparent that aspects of literacy teaching and learning that I assumed were common knowledge were in fact very new to my students (Korthagen et al. Citation2001). In the course of the self-study, I also noted that I didn’t naturally include opportunities for students to share their prior knowledge or experiences during lectures, for example in week four, I noted ‘I did not ask if they knew any of the phonic terminology, or if they had seen phonics taught in classrooms which may have helped to cement their knowledge’ (RJ, W4). I had always assumed that I did include this important element in my teaching, but analysis of my teaching through reflection revealed that it only happened when I explicitly planned to do so, highlighting the importance of deliberate explicit teaching) Therefore, during the self-study, I began to explore how I could include the activation of prior knowledge during lectures (Ashwin et al. Citation2015). This made a significant impact on my teaching, and on student engagement. I began to use mentimetre.com (a large group response system) to ascertain experiences and knowledge in larger lectures. I also provided more opportunities for pair and group discussion to ground the topic before exploring new territory, often giving the students large post-its to record their thoughts in relation to prior knowledge and experiences at different junctures (Ashwin et al. Citation2015). This made learning more visible (Hattie Citation2012) and allowed me to respond to students’ needs in a more effective manner (McDowell et al. Citation2010). Indeed, a critical friend who observed a lecture in the second half of the semester commented, ‘I really liked the question you asked them at the outset. The students had no problem engaging with that discussion with peers … encouraging the students to draw from their own experience is excellent practice in helping them bring their past into the learning’ (PO2). Indeed, the student focus groups revealed how ‘new’ so much of the material that we covered in the module was to them (Korthagen et al. Citation2001), reporting that ‘comprehension strategies like predicting, connecting … I don’t ever remember learning all that’ and ‘phonics … why wasn’t this around when I was small?’ (FG1). An awareness of the ‘newness’ of the methodologies explored in the module led me to consider how they were presented visually on slides. I reduced the number of slides and ensured that individual slides were not content heavy in my lectures (Smith Citation1999). I divided each lecture into smaller manageable ‘chunks’ of information (Miller Citation1956) and used visuals to a much greater extent that I had in previous iterations of the modules (Sadoski and Paivio Citation2001). One critical friend who was unfamiliar with my subject area commented on the clarity of my lecture slides, which had been revised in light of my reflective journal.

In this way, the self-study encouraged me to think more about the learners in the lecture hall in relation to their perceptions, experiences and evolving beliefs about literacy teaching and learning. Prior to the self-study, I would have assumed that I did already take account of this, but careful reflection revealed that my assumptions about my teaching and my learners were not always true.

Creating dynamic lecturing spaces

Despite years spent as a primary school teacher, where I modelled processes explicitly throughout the day, my reflective journal revealed a reluctance to do so in a university setting as recommended by Gambrell et al. (Citation2015). For example, I reflected that there was ‘simply too much telling and not enough showing in this week’s workshops’ (RJ, W3) which impacted on student engagement (Loughran Citation2007). Therefore, I made a particular effort to model methodologies explicitly and scaffold learning (Vygotsky Citation1978) when a critical friend observed me. For example, in our post-observation conversation, I admitted ‘last year, I didn’t bring the puppet, I just showed the picture’ when she complimented me on the explicit modelling I had done with a puppet in the tiered lecture theatre. I also noted the change in my practice in a workshop in week 2 ‘I think I did a good job of modelling in the workshop. I actually did the activities with the students rather than just telling them about it. I made sure to bring markers, acetates, post-its and puppets to role-play the methodologies properly and I think it made a difference to the students’ engagement’ (RJ, W2). I took time to demonstrate each step and to articulate the thinking behind them. A pop-quiz the following week revealed that the students were able to recall many of the specific examples demonstrated, and I noted that ‘clearly the specific examples demonstrated “live” with actual texts made an impact’ (RJ, W3). Indeed, end of semester evaluations revealed that students appreciated the interactive modelling and rated me highly as a professor as a result (Berry Citation2008).

During the self-study, I also began to realise that modelling can take many forms. While I initially focussed on my in-class demonstrations of methodologies, I soon realised that lesson plan exemplars were also considered a form of modelling and were highly prized by students, and related to cognitive load theory (Sweller et al. Citation1998) as they were presented as a worked example for the students. In week four, I noted that a session on lesson planning ‘...was the session that made the most sense to them so far this semester, probably because it was focused on planning and teaching’ (RJ, W4). This may be related to adult learners' need to see the intent and goal of what they are learning, as lesson plans would be recognised as an ‘endpoint’ by students (Knowles Citation1988). While I felt that the students needed ‘a wide range of exemplars to really help them feel prepared’ (RJ, W9), this realisation came too close to the end of the semester and was re-iterated in student evaluations of the module.

The use of story-telling is another useful method for demonstrating theory in an engaging manner (Hebb Citation1959). In my reflective journal, I noted that the students responded well to stories from the classroom and my critical friends complimented me on the use of stories throughout the lectures. I began to reflect on how I could use story in different ways across topics. I had a very large group lecture on planning (four hundred and fifty students) which is a rather ‘dry’ topic. I decided to structure the lecture by telling the ‘story’ of an imaginary class and how particular lessons were suited to their needs. I did the same with a large group lecture on language acquisition theory, sharing stories about teaching young English language learners and their experiences learning to be literate. Having taught both these lectures in the past in a much more traditional manner, I reflected that they ‘were much more engaging and satisfying to teach through story’ (RJ, W10) as they made the learning more real to the students (Rodgers and Freiberg Citation1994).

My tendency to tell the students rather than demonstrate a methodology is perhaps linked to the amount of content that I would try to cover during each session and across the module. As early as week one, I noted my tendency to ‘over plan’, ‘perhaps not taking account for the need to stop for discussion or demonstration’. Indeed, by week four I noted ‘It got me thinking about the overall structure of our modules … how do we get depth rather than breadth?’ (RJ, W4). While developing a sound knowledge base in literacy methodologies is important (Gambrell et al. Citation2015), taking time to deliberately model practices and having students reflect on those practices is more effective than simply covering content (Loughran Citation1996). Thus, I adjusted the amount of content so that the learning experience was more engaging and easier for my students to understand.

Opportunities to articulate learning

In the first few weeks of the self-study, I began to note an absence of assessment of learning in my lectures. As early as week one, I noted that ‘I am worried about cognitive closure, I should have had an exit card or something instead of me talking and summarising key points’ (RJ, W1). I also noted that we tended to complete activities without examining why we did them, ‘I don’t think I gave enough thought to helping students think about implementation. I didn’t ask them what the activity meant for school placement, I didn’t ask them “so what?” about creating literacy metaphors. I need to do this more’ (RJ, W1). Therefore, I began to analyse how I could ensure students were understanding module content. Using interactive pop quizzes, video viewing guides, interactive report instruments (such as mentimetre.com) and critical incident questionnaires (Ashwin et al. Citation2015) I gained more of an insight into how my students were learning. However, they did not always reveal straightforward results. Indeed, I noted in my research journal that ‘you can’t please everyone all of the time’(RJ3, p.1) as having used a critical incident questionnaire (Brookfield Citation2017) with an Masters’ level class; ‘I was surprised to discover several contradictions in their responses’ in relation to the different learning experiences within the session (discussion, videos, audio recordings, pair work and modelling by the lecturer) as ‘some found the video helpful but others didn’t feel like it assisted their learning, most liked pair-work but one reported feeling uncomfortable during the process’. In every class, I offered the students a chance to ask questions but my reflective journal revealed a difficulty with this: ‘They didn’t ask questions. Does this mean they are totally confused or that it is clear to them? I should have used a response system to verify that’ (RJ, W4). It may have been possible that they had many questions but were anxious about responding due to the large class size which might not be a comfortable learning environment for many students (Hargreaves Citation2015) which can contribute to disengagement (Ashton and Stone Citation2018). In order to develop a culture of knowledge exchange within the group, I began to use mentimetre.com in lectures. This did promote question asking, but it had mixed results as while the students did ask a good deal of useful questions, some of the questions were not helpful. Unfortunately, this tool provides anonymous responses and relies on a mature audience. However, I did find some of the questions to be quite unexpected and they highlighted the difference between my ‘frame’ of reference and the students’ ‘re-framing’ (Schon, 1987) of the information. For example, they often asked about minute points of practice that I would have regarded as trivial which illustrated their need for the tacit knowledge of teaching that I had forgotten to make explicit. This heightened my sense of the learner’s needs and allowed me to adapt my teaching in a meaningful and effective manner.

My developing awareness of the need to ‘check in’ with my students' learning of particular content or their overall learning experience, led to a conscious effort to ‘spot check’ (RJ, W2) after every ‘seven plus or minus 2ʹ chunks of learning (Miller Citation1956). I also started to begin each lecture with a discussion of learning outcomes which I returned to at the end of class. I set an expectation that they should be able to answer these questions at the end of class, as I noted in my reflective journal that I tended to simply ‘remind them of what they learned’ due to ‘being under time pressure or perhaps because I don’t trust my teaching enough that the students would be able to feedback what they learned with confidence’ (RJ, w3). I would then re-visit the learning outcomes at the end of the lecture and have the students articulate their learning. Indeed, in week three, I noted ‘This week, I hope to be very conscious of making students accountable for their learning. I will make sure to allocate at least five minutes at the end of class to do a proper closure’ (RJ, W3). The use of exit slips at the end of class was informative. While it revealed the students learning, it also highlighted some misunderstandings and allowed me to discuss the misconceptions in the following week. For example, we completed an activity designed to enable teachers to analyse a child’s reading strategies when we explored word identification. Some of the exit slips revealed that some students thought that the activity was designed for children and not the teacher. If exit slips had not been used at this point, this misunderstanding could have led to further learning difficulties for those students (Kelchtermans Citation2005). Therefore, exit slips were a powerful means of assessing learning and for planning for future instruction (McDowell et al. Citation2010). I also noted that paying careful attention to any written work during class, could be helpful in encouraging questions from the students, particularly those that were very shy about speaking in class (Hargreaves Citation2015): ‘The students are extremely quiet and terrified to answer. I felt like they were learning nothing, however, when I looked at their notes on the writing samples, they knew more than I realised. I should have paid closer attention to what they were writing so that I could have phrased my questions in a certain way to help them feel like answering’ (RJ, W4). I noted that the students seemed more comfortable engaging in small group discussion in my reflective journal so I began to use this strategy more often in class. In the focus groups, a student commented on its effectiveness, stating ‘when we did a speaking partner, like you’d go back over it with your speaking partner and that was really helpful’ (FG1).

Observations by critical friends made me more conscious of the need to ‘check in’ with the students. In a post-observation conversation during cycle one, I noted ‘I was conscious that you would be watching, so I refined and changed things … for example the number of interactions that I had with the students to check their learning, there were points were I could have just gone through the slides but I didn’t because I was conscious of the amount of teacher/student talk as it is on my reflective template’ (PO1).

Therefore, the use of multiple tools to aid critical reflection on practice helped to develop my awareness of how and when I assessed my students learning. It also made me more conscious of how I organised information so that it was easier for the students to keep track of their learning.

Conclusions and implications

This self- study sought to explore how I might enhance my teaching of teachers. As the validity of a self-study is based on trustworthiness, these findings are shared as an exemplar-based validation by others who find themselves in similar contexts (Vanasshe & Kelchtermans, 2015). While its contextual nature may be a limitation of the study, its strength lies in its ability to illustrate the exploration of reflective practice in literacy teaching and learning in higher education in depth.

Despite its small scale, this self-study has a number of implications for theory and practice. Firstly, it explored the effect one’s assumptions about one’s students can have on the quality of teaching and learning. The data gathered illustrated the importance of knowing oneself as a teacher and a learner when working in a higher educational context. How a professor in higher education might perceive module content can be markedly different from how it might be identified by students. The tiered lecture hall can encourage a sense of being removed from the students, yet it is essential that professors take time to ‘stand in the shoes’ of their students in order to gain an understanding of their perceptual lens that has a significant effect on their learning. An awareness of the critical importance of the prior knowledge and experiences that our students bring to the lecture hall and allowing time and space to explore this before, during and after learning is critical to creating a positive learning experience for all.

Developing engaging lectures can be enhanced through reflective practice and feedback provided by critical friends in the form of peer observations. These practices are not as wide-spread as perhaps they should be in higher education and certainly self-study is still a relatively new research methodology that is yet to be disseminated broadly in academia.

This self-study also draws attention to the tendency to perhaps over-rely on summative assessment of learning practices in universities such as formal examinations or assignments. Only on careful reflection, did I come to acknowledge the lack of on-going formative assessment of learning in my practice which is concerning given my assumption that my students would implement this in their future classrooms.

Finally, the study also highlights the need to engage the student voice in learning. Data gathered through exit slips, reflection on evaluations and student focus groups illuminated important issues relating to student self-efficacy, their knowledge base and their ability to transform knowledge into practice. Developing an awareness of the student experience presents a powerful opportunity to enhance the teaching and learning environment in a variety of ways.

Change through self-study can be a slow, on-going process and change can be evolutionary rather than revolutionary (Fullan Citation2015). Simple answers are unlikely in the realm of self-studies as they represent an ‘indeterminate swampy zone’ (Schon, 1987, p3) of complexity. Indeed, my self-study has left me with more questions than answers but has deepened my self-awareness of the student learning experience and my own ‘self’ in practice which will undoubtedly improve the delivery of my literacy modules. Hopefully, others may have gleaned some valuable insights from my experience. Indeed, as Guilfoyle (Citation1995) contended: ‘teaching is a life-long process … one doesn’t eventually become a teacher; but instead moves in understanding teaching/learning through active involvement in the process’ (p.18).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Andrews, J., Garrison, D., and Magnusson, K., 1996. The teaching and learning transaction in higher education: a study of excellent professors and their students. Teaching in Higher Education, 1 (1), 81–103. doi:10.1080/1356251960010107

- Ashton, S. and Stone, R., 2018. An A-Z of creative teaching in higher education. London: Sage.

- Ashwin, P., et al., 2015. Reflective teaching in higher education. London: Bloomsbury.

- Berry, A., 2008. Tensions in teaching about teaching: understanding practice as a teacher educator. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Berry, A., 2009. Professional self-understanding as expertise in teaching about teaching. Teachers and teaching: Theory and Practice, 15 (2), 305–318. doi:10.1080/13540600902875365

- Braun, V. and Clarke, V., 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3 (2), 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bronfenbrenner, U., 1979. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Brookfield, S.D., 2017. Becoming a critically reflective teacher. 2nd. San Francisco CA: Jossey Bass.

- Bruner, J., 1986. Actual minds, possible worlds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bryman, A., 2004. Social research methods. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bullock, S.M., 2009. Learning to think like a teacher educator: making the substantive and syntactic structures of teaching explicit through self-study. Teachers and Teaching Theory and practice, 15 (2), 291–304.

- Bullough, R.V. and Gitlin, A.D., 2001. Becoming a student of teaching: linking knowledge production and practice. New York: Routledge.

- Dewey, J., 1963. Experience and education. New York: Collier Books.

- Drago-Severson, E., 2004. Helping teachers learn. CA: Corwin Press.

- Elliot, J., 1991. Action research for educational change. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Festinger, L., 1957. A theory of cognitive dissonance. New York: Harper & Row.

- Fletcher, T., Ní Chróinín, D., and O’Sullivan, M., 2016. A layered approach to critical friendship as a means to support pedagogical innovation in pre-service teacher education. Studying Teacher Education, 12 (3), 302–319. doi:10.1080/17425964.2016.1228049

- Freire, P., 1972. Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Herder & Herder.

- Fullan, M., 2015. The new meaning of educational change. 5th. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Gambrell, L.B., et al., 2015. Evidence-based best practices in comprehensive literacy instruction. In: L.B. Gambrell and L.M. Morrow, eds. Best practices in literacy instruction. 5th ed. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 3–36.

- Garmston, R. and Wellman, B., 1999. The adaptive school: a sourcebook for developing collaborative groups. El Dorado Hills, CA: Four Hats.

- Grierson, A.L., 2010. Changing conceptions of effective teacher education: the journey of a novice teacher educator. Studying Teacher Education, 6 (1), 3–15. doi:10.1080/17425961003668898

- Guilfoyle, K., 1995. Constructing the meaning of teacher educator: the struggle to learn the roles. Teacher Education Quarterly, 22 (3), 11–28.

- Hargreaves, E., 2015. Pedagogy, fear and learning. In: D. Scott and E. Hargreaves, eds. The SAGE handbook of learning. London: Sage, 310–320.

- Hattie, J., 2012. Visible learning for teachers. London: Routledge.

- Hebb, D.O., 1959. A neuropsychological theory. In: S. Koch, ed.. Psychology: A study of a science. Vol. 1, pp. 622–643. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Jackson, P.W., Ed., 1968. Handbook of research on Curriculum: A project of the American educational research association. New York, NY: Macmillan Publishing Company.

- Jeanne, H., 1990. Enriching prior knowledge: enhancing mature literacy in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 61 (4), 425–447.

- Jonassen, D.H. and Rohrer-Murphy, L., 1999. Activity theory as a framework for designing constructivist learning environments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 47 (1), 61–79. doi:10.1007/BF02299477

- Kamler, B., 2001. Relocating the personal: A critical writing pedagogy. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

- Kelchtermans, G., 2005. Teachers’ emotions in educational reforms: self-understanding, vulnerable commitment and micropolitical literacy. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21 (8), 995–1006. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2005.06.009

- King, K., Logan, A., and Lohan, A., 2019. Self-study enabling understanding of the scholarship of teaching and learning: an exploration of collaboration among teacher educators for special and inclusive education. Studying Teacher Education, 15 (2), 118–138. doi:10.1080/17425964.2019.1587607

- Knowles, M., 1988. The modern practice of adult education. Cambridge: Cambridge Book Company.

- Korthagen, F.J., et al., 2001. Linking practice and theory: the pedagogy of realistic teacher education. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Lortie, D.C., 1975. Schoolteacher. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Loughran, J. & Russell, T (2007). Beginning to understand teaching as a discipline, Studying Teacher Education. 3(2), 217–227.

- Loughran, J.J., 1996. Developing reflective practice: learning about teaching and learning through modelling. London: Falmer Press.

- Loughran, J.J., 2007. Researching teacher education practices. Journal of teacher education, 58 (1), 12–20. doi:10.1177/0022487106296217

- Loughran, J.J. and Russell, T., 2007b. Beginning to understand teaching as a discipline. Studying Teacher Education, 3 (2), 217–227.

- Louie, B.Y., et al., 2002. Myths about teaching and the university professor: the power of unexamined beliefs. In: J. Loughran and T. Russell, eds.. Improving teacher education practices through self-study. London: Routledge Falmer Press, 193–207.

- McArthur, J., 2009. Diverse student voices in disciplinary discourses. In: C. Kreber, ed. The universe and its disciplines. New York, NY: Routledge, 119–128.

- McDowell, L., et al., 2010. Does assessment for learning make a difference? The development of a questionnaire to explore the student response. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 36 (7), 749–765. doi:10.1080/02602938.2010.488792

- Miles, M.B. and Huberman, A.M., 1994. Qualitative data analysis: an expanded sourcebook. London: Sage.

- Miller, G.A., 1956. The magical number seven, plus or minus two: some limits on our capacity for processing information. Psychological review, 63 (2), 81–97. doi:10.1037/h0043158

- Murray, J. and Male, T., 2005. Becoming a teacher educator: evidence from the field. Teaching and Teacher Education, 21 (2), 125–142. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2004.12.006

- Plato, 1970. The republic: the dialogues of Plato (trans./ed. B. Jowett). London: Sphere Books.

- Ritter, J.K., 2017. Those who do self-study, do self-study: but can they teach it? Studying Teacher Education, 13 (1), 20–35. doi:10.1080/17425964.2017.1286579

- Rodgers, C. and Freiberg, H.J., 1994. Freedom to learn. 3rd. Merrill: New York.

- Rowland, S, 2005. Intellectual love and the link between teaching and research. In: R. Barnett, ed.. Reshaping the university. Maidenhead: Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press, 92–101.

- Sadoski, M. and Paivio, A., 2001. A dual coding of reading and writing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Schön, D., 1983. The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action. London: TempleSmith.

- Smith, M.K. (1999). The cognitive orientation to learning. The encyclopaedia of informal education. Retrieved March 19th, 2019 from http://infed.org/mobi/the-cognitive-orientation-to-learning/.

- Sweller, J., Van Merriënboer, J., and Paas, F., 1998. Cognitive architecture and instructional design”. Educational psychology review, 10 (3), 251–296. doi:10.1023/A:1022193728205

- Tidwell, D.L., Heston, M.L., and Fitzgerald, L.M., Eds., 2009. Research methods for the self-study of practice. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Trumbull, D. 2004. Factors important for the scholarship of self-study of teacher and teacher education practices. In: J.J. Loughran, et al., eds. International handbook of self-study of teaching and teacher education practices. Dordrecht: Kluwer Publishing, Vol. 2, 1211–1230.

- Vanassche, E. and Kelchtermans, G., 2015. The state of the art in self-study of teacher education practices: A systematic literature review. Journal of Curriculum Studies, 47 (4), 508–528. doi:10.1080/00220272.2014.995712

- Vygotsky, L.S., 1978. Mind in Society: the development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Wertsch, J.V., 1985. Vygotsky and the social formation of mind (revised ed.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Zeichner, K., 2007. Accumulating knowledge across self-studies in teacher education. Journal of teacher education, 58 (1), 36–46. doi:10.1177/0022487106296219