ABSTRACT

It is difficult to identify direct causal relationships between school-based professional learning initiatives and changes in the participating teachers’ competencies or their students’ learning outcomes. This paper contributes a novel approach to examining the impact of such school-based professional learning by integrating the constructs of complex systems and agentic practice into how the processes in curriculum re-design contribute to professional learning outcomes. The paper first presents an integrated multilayered conceptual framework that combines perspectives on complex systems and agentic practices. Next, it outlines the main levels and aspects of the complex system that need to be considered when examining school-based professional learning initiatives. Then, using a case from a multi-school professional development initiative illustrates how this framework was applied to examine the impact of a professional learning initiative focused on a collaborative science curriculum redesign to support English Language Learners (ELLs). Analysing the agentic practices that emerged within and across different complex system levels provides a comprehensive insight into how the system, constraints or amplifies particular practices.

1. Introduction

Professional learning initiatives to support teachers in improving their classroom practices are only sometimes successful, and it is often unclear why. Effective professional learning usually occurs when teachers refine their knowledge and adjust the suggested approaches to meet their students’ specific contexts and needs (Reid and Kleinhenz Citation2015). So, rather than considering effective professional learning as a simple causal relationship between inputs and outputs, we suggest that teachers’ professional learning should be considered from the perspective of complex systems (Opfer and Pedder Citation2011, Strom and Viesca Citation2021). From this perspective, three main aspects should be considered in examining teachers’ professional learning.

First, rather than considering a possible direct causal relationship between planned professional development initiatives and a narrow set of professional learning outcomes, we should look for multiple components and various dynamics contributing to the professional learning outcomes (Opfer and Pedder Citation2011). Professional learning outcomes cannot be attributed to one simple causal relationship; the interactions among the participants, joint curriculum materials and the available resources within a particular context create feedback loops that result in observable outcomes (Shaked and Schechter Citation2016, Daly et al. Citation2020).

Next, we should consider the processes involved in and resulting from the teachers’ professional learning. The importance of teachers’ active role in their professional learning is well-established (Kauppinen et al. Citation2020). Learning, the simultaneous transformation of the knower and the knowledge arises in a particular context from synergistic interactions between different entities or groups of entities, such as the teachers or the students (Levy and Wilensky Citation2008). These interactions may occur in different parts of the system. They are non-linear and bring diverse viewpoints to address the school-based problem (Ell Citation2019).

Finally, is the consideration of teachers’ active roles in their professional learning. Rather than viewing the school as uniform and consistent, a complex systems perspective suggests we should consider it a set of nested systems and subsystems (Strom and Viesca Citation2021). These subsystems are physically and temporarily located in different spaces; the professional community where teachers interact with each other occurs in the staffrooms and other staff-only spaces (e.g. staff intranet, staff meetings), while the teaching/learning space in the classroom/lesson is where teachers can enact new approaches and receive feedback from the students’ activities (Pietarinen et al. Citation2016). Students’ activities are particularly important to consider in the current context of effective science instruction, which positions students as active contributors to knowledge construction (Miller Citation2009, Miller et al. Citation2018). While we acknowledge that each school fits within the wider context of its community and state educational authority, in this paper, we limit our discussions to two subsystems within the wider system of the school, (i) the professional community of teachers and (ii) the teaching/learning space where teachers and the students interact. The interactions within and between the system and these subsystems are dynamic. A change in one subsystem may impact the other subsystems and the system. Examining changes in the patterns of interactions within and between the subsystems may provide insights into the quality of professional learning, which we conceive as an emergent phenomenon (Ell Citation2019).

To examine these interactions, we combine a complex systems perspective with the construct of Agency. This paper defines agency as ‘the capacity of actors to make practical and normative judgements among possible alternative trajectories of action, in response to the emerging demands, dilemmas, and ambiguities of presently evolving situations’ (Biesta and Tedder Citation2007, p. 136). Practices that are enabled by and emerge from this capacity, enacted in specific contexts, are called agentic practices. This definition frames agentic practices as an emergent phenomenon that results from the interplay of the individual’s capacities and the conditions within their context, which may constrain or support their actions (Fu and Clarke Citation2019). Agentic practices are distinct from routine practices, which are enacted without judgement.

In the section below, we present the integrated conceptual framework that combines the constructs of complex systems and agentic practices and outlines the main levels of the complex system and the kinds of agency that need to be considered when examining school-based professional learning initiatives. Then, we use a case from a school-based professional learning initiative to illustrate how this framework could be applied and what kinds of insights this framework reveals into the emerging agentic practices that characterise this impact.

2. Conceptual framework

2.1. Professional learning from a complex systems perspective

One challenge in implementing effective professional learning is that teachers must translate the knowledge gained during professional learning sessions into their classroom practice (Markauskaite, Goodyear, & Sutherland Citation2021). Studies focused on improving teachers’ use of existing instructional materials in their classrooms have reported mixed success (e.g. Buxton et al. Citation2015, Lyon et al. Citation2018). Rather than looking for direct causal relationships between a professional learning initiative, changes in teachers’ competencies or students’ learning outcomes, a complex systems approach considers how the components interact, contributing to the overall system’s performance (Shaked and Schechter Citation2019). A complex systems perspective recognises that the outcomes cannot be explained by considering the individual components but emerge from the interactions, adaptation, and feedback among multiple components, leading to self-assembly and unpredictable outcomes. The processes are identified as emergence (Ell Citation2019).

From a systems perspective, the emergent phenomenon of teachers’ professional learning is multicausal, multilayered and multidimensional. Actions occur within different subsystems; over time, these actions can impact the subsystem and the system (Strom and Viesca Citation2021). Therefore, we must consider feedback. This feedback could be either reinforcing (sometimes called ‘positive’) or balancing (sometimes called ‘negative’). Reinforcing feedback amplifies path-dependent behaviours (e.g. the more teachers work collaboratively, the more they learn from each other); balancing feedback, on the other hand, restores equilibrium (e.g. the more time teachers spend working collaboratively, the less time they have for individual professional learning). From this perspective, teachers’ professional learning is self-assembled and adaptive. Thus, the outcomes cannot be attributed to one simple causal relationship; an individual’s actions and the reaction of others create feedback loops that contribute to the emergent outcomes over time (Shaked and Schechter Citation2016, Daly et al. Citation2020). Therefore, there are no simple direct causal relationships between specific professional development actions to explain the outcomes of a professional learning initiative; multiple participant interactions within and between the subsystems contribute to the outcomes.

At the smallest level, individual entities, the teacher, a combination of personal factors must be considered. These factors include the teacher’s motivation, dispositions and beliefs, particularly the extent to which beliefs match the proposed changes in pedagogy, their risk-taking capacity, and their perceptions of the extent to which the school culture supports changes in practice (Postholm Citation2012, Le Fevre Citation2014, Buxton et al. Citation2015, Chaaban Citation2017).

Teachers rarely work alone but in formal and informal groups (Strom and Viesca Citation2021). Interactions between teachers form a mid-level subsystem within the complex system of the school. At this level, Professional Learning Communities (PLCs) are the core mechanism to support teachers’ professional development. PLCs take various forms. They can be defined as groups of teachers who share a common vision to improve teaching, work collaboratively to find solutions and use changes in students’ learning to judge the effectiveness of their actions (Dogan et al. Citation2016). PLCs are most effective when: (i) they are supported by school leadership to focus on an authentic issue (Dobbs et al. Citation2016); and (ii) the members are willing to collaborate and learn from and with each other (Schneider et al. Citation2012). PLCs are critical for a professional learning initiative, collaborative curriculum planning and redesign (Voogt et al. Citation2015). In this approach, teams of teachers revise and adapt curriculum materials to meet the demands of their context. Through the processes of the curriculum redesign, the relationships among the teachers are enhanced, the teachers’ knowledge and skills are recognised, and teachers are given the autonomy to make decisions that will impact their learning and the learning of their students (Kelly et al. Citation2019).

At the school level, in a complex system, a culture supporting pedagogy changes has been recognised as a key school-based factor associated with changes in teachers’ practices. Leaders who promote and maintain positive and constructive relationships among teachers and provide sufficient time and support for teachers to collaboratively plan and reflect on the impact of their changes on their students’ learning are more likely to observe changes in their teachers’ pedagogical approaches (Darling-Hammond and Richardson Citation2009, Capps et al. Citation2012, Postholm Citation2012, Whitworth and Chui Citation2015). While there is no consistency in the time needed for a change in practice, it is generally recognised that extended periods are more likely to lead to substantive change in teachers’ practices, e.g. two hours per week for two years (Postholm Citation2012). Shorter interventions are more likely to support teachers’ knowledge development but are less likely to change their classroom approaches (Capps et al. Citation2012).

Overall, the complex systems perspective described above provides a non-reductionist framework to examine the impact of school-based professional learning, considering multiple factors and emerging processes simultaneously (Shaked and Schechter Citation2019).

2.2. Agencies and emerging agentic practices in professional teacher learning

As the outcomes of school-based professional learning arise from the interactions among the participants, then the constructs of agencies and agentic practices offer a basis to examine the process of professional teacher learning and the emerging outcomes. Agentic decisions are made when actors judge past actions and routines, modifying previous decisions to address the emerging demands and challenges in the present and evolving situations (Biesta and Tedder Citation2007). Agency is expressed through and within an environment. The resources, contextual and structural factors all impact the expression of agency (Priestley et al. Citation2015). Agency is not one homogeneous construct. Rather, each participant is positioned in relation to other participants and disciplinary fields within their situated environment, and their practices involve a dance of various kinds of agencies (Pickering Citation1995, Greeno Citation2006).

Five main aspects of agency need to be considered. First is bounded agency (Evans Citation2007), defined as the interactions between actors’ perceptions of available affordances in their context and their imagined future. Perceptions of the bounded agency are based on actors’ prior experiences and how these experiences impact their interpretation of the context (Fox et al. Citation2010), their sense of control, and their relationships with other participants (Evans Citation2007). For example, teachers’ bounded agency can be enhanced or diminished by the school leadership. Similarly, the teachers’ prior experiences in the teaching/learning space can contribute to their willingness to experiment with new teaching methods (Pietarinen et al. Citation2016).

Next is the teachers’ professional agency, a participant’s capacity to prepare for the intentional and responsible management of new learning and enact it personally and within the school community (Pietarinen et al. Citation2016). Professional agency, the key to teachers’ classroom practices, is multidimensional, including their relationships with others and personal qualities such as motivation and beliefs (Biesta et al. Citation2015, Garner and Kaplan Citation2021). Teachers must consider themselves active learners contributing to their success, seeking support, and reflecting on their actions. The contexts in which they work can impact the extent to which teachers’ professional agency is enacted (Pietarinen et al. Citation2016). From the perspective of the school as a system, structures and resources that support teacher collaboration promote and maintain positive and constructive relationships among the teachers and provide teachers with sufficient time and support to plan and reflect on the impact of their changes collaboratively have been associated with the demonstration of teachers’ professional agency (Darling-Hammond and Richardson Citation2009, Capps et al. Citation2012, Postholm Citation2012, Whitworth and Chui Citation2015).

Teachers’ professional agency needs to be considered in relation to student agency. The student’s prior knowledge, experiences and behaviours impact how a professional learning initiative changes their learning and improves outcomes. Student agency is ‘the intention and capability to take action concerning one’s learning… to change the trajectory of their and their peers’ learning’ (Clarke et al. Citation2016, p. 30). Students’ classroom behaviours are a part of their agency. Students can support or undermine teachers’ efforts to change their learning in the classroom. Current views of effective science instruction position students as active learners contributing to knowledge construction and taking significant epistemic agency (Miller Citation2009, Miller et al. Citation2018). This view of effective education may contrast with students’ beliefs about the role of themselves and the teacher, impacting their behaviours in the classroom. For example, before arriving in Australia, many English language learners have experienced disrupted education or very different pedagogical approaches to their education. These prior experiences contribute to student agency. Similarly, as the students’ agency can impact teachers’ professional agency, the teachers’ professional agency can enhance or reduce students’ agency. Teachers’ decision-making in the selection and implementation of activities and the organisation of their classrooms all impact the extent to which students engage in science practices.

Agency at all complex system levels has two aspects: epistemic and relational. Epistemic agency refers to agentic activities involving knowledge and knowing (Damsa et al. Citation2010). As they describe, ‘agency can be considered epistemic when it expresses learners’ intentional, goal-directed, and sustained involvement in knowledge-driven, object-oriented, collaborative activities.’ (p. 149). In science classrooms, students’ epistemic agency is primarily concerned with making sense of complex scientific phenomena and addressing issues and problems they might face. Students’ epistemic agency is advanced when: (i) the instruction builds on students’ knowledge, (ii) they are actively engaged in developing their knowledge, and (iii) they perceive the relevance of the knowledge they produce (Miller et al. Citation2018). Teachers’ epistemic agency is primarily concerned with their willingness to ‘engage in knowledge-related practices and innovation in authentic classroom teaching context’ (Markauskaite, Goodyear, & Sutherland Citation2021, p. 2). Such agency is considered an important part of teachers’ professional expertise and strongly relates to their prior experiences and current context.

Relational agency is defined as the capacity to coordinate thoughts and actions with other participants by recognising the resources and motivations others bring to the problem, acting on these insights to expand the initial interpretation of the problem, and finally working with others to develop a coordinated solution (Edwards Citation2011). Participants learn from each other through their relational agency as they address an authentic issue or problem (Dobbs et al. Citation2016). Teacher and successful student engagement in collaborative activities interrelated to each other’s knowledge, motivations and intentions rely on their relational agency. Interactions between relational agencies of individual participants result in the collective agency.

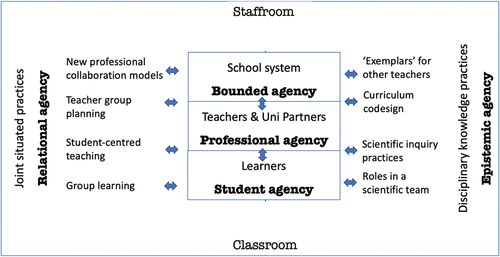

provides a schematic representation of the relationships between the different agencies described above. Each agency is enacted in specific contexts from which new practices emerge. Examining the emergence of new agentic practices resulting from a school-based professional learning initiative can provide insight into the impact of this initiative on the entire system. Therefore, integrating complex systems and agentic practice constructs provides an innovative way to examine curriculum re-design processes.

3. Aims and background

In the rest of the paper, we illustrate how the above framework can be applied to examine the impact of a school-based professional learning initiative. Our chosen case came from a professional learning initiative based on a collaborative curriculum design approach (Voogt et al. Citation2015) focusing on redesigning the science curriculum to support English Language Learners (ELLs). Our main research questions are:

What agentic practices emerge within a collaborative curriculum redesign?

How do the agentic practices within and between the subsystems in a school contribute to the outcomes of a professional learning initiative?

To answer these research questions, we selected a case from a professional learning initiative in one Australian state focused on a collaborative science curriculum redesign to support English Language Learners (ELLs). In this professional development, a group of schoolteachers transformed part of a school-based Science program to enhance ELL students’ language development through their engagement in science practices. Therefore, before presenting the case, we review the challenges of supporting ELLs in science classrooms that teachers commonly face.

3.1. Background: the challenge of supporting ELLs in science

Like many other English-speaking countries, Australia has seen marked increases in students for whom English is an additional language. Research indicates that it usually takes five to seven years for ELLs to develop the language they need to succeed in school (Cummins Citation1989). To fully participate in the discourse of science classrooms, ELL students need to move beyond colloquial or social language to develop academic language proficiency (Ardasheva et al. Citation2016, MacSwan Citation2020).

A lack of linguistic skills limits students’ engagement in science practices in science classes. To engage in these practices, students must move beyond everyday language (i.e. the ability to communicate with others in a social setting) to use the appropriate academic discourses (Ardasheva et al. Citation2016). However, many secondary science teachers lack professional knowledge to support ELL students’ language development (Buxton et al. Citation2013).

The achievements of ELL students in science are limited without appropriate opportunities to develop their abilities to use the academic discourse of science (Lee et al. Citation2019). Developing this ability is especially challenging for students in secondary or high schools. First, at this stage in their education, science concepts become more abstract. The scientific discourse needed to engage with these concepts becomes more specialised and academically complex (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2018). Next, specific disciplinary academic language is used in reading and expected in writing (Hand et al. Citation2010). Finally, academic science language is intertwined with cognitive skills associated with discipline-specific discourses, such as linking cause and effect. These cognitive skills underpin two important outcomes of science education, constructing scientific explanations and drawing evidence-based conclusions (Buxton et al. Citation2013, Miller et al. Citation2018). Thus, professional learning initiatives are needed to enhance the teaching of ELL students in science. The professional learning initiative examined in this paper addressed the above problem.

4. A case study

4.1. The professional learning initiative

The chosen case was a part of a professional learning project funded by a state Department of Education in Australia, targeted at experienced science and ELL teachers working in eight lower socioeconomic status (SES) schools. The professional learning program used a collaborative curriculum redesign approach. At eight schools, teams consisting of a specialist ELL language teacher, a science teacher and a headteacher science were required to develop a modified version of an existing program and implement and evaluate their modification of an existing science school program.

The professional learning initiative was largely school-based, heavily relying on the expertise within the schools to provide the professional knowledge to support students’ language development through their science instruction. It was organised into two components and lasted five months. External professional development facilitators led formal sessions (3 days in total) from the department and science and ELL educators from a collaborating university. They introduced key ideas that teachers should consider in the curriculum redesign. School-based meetings of the team of teachers at the school were allocated for working on curriculum redesign and implementation. Science and ELL teacher educators attended these school meetings from the collaborating university on two or three occasions. These meetings focused on how the ideas introduced in the formal sessions could be developed within the school context (Sutherland Citation2021).

4.2. Research design

A case study methodology was used to examine the impact of the professional learning initiative as this methodology can provide detailed insights into participants’ understanding of a phenomenon and allow the possible interactions among the different aspects of agency to be examined (Bleijenbergh Citation2010, Harrison Citation2017). To illustrate our approach, we have chosen to present a case study school. The school selection was purposeful: the school provided the richest data set, and all participating teachers worked together throughout the intervention. The data, collected from multiple sources over five months, included (i) the individual teachers’ expressions of interest to participate in the professional learning initiative, (ii) the recording of the teachers’ informal and formal presentations, and (iii) the resources they used with their students, (iv) their prompted group reflective interviews on three of these resources, and (iv) individual interviews with each teacher.

Following the transcriptions of the recordings of the interviews, the research team read the transcripts and identified the salient episodes indicative of the participants’ agentic behaviours, their reasons for making particular agentic decisions and contributing factors within the wider context of the school. Thematic analysis was used to classify the identified episodes based on the different layers of agency (bounded, professional, and student) and two dimensions (epistemic and relational). The main indicators of bounded agency were how the participants’ prior experiences impacted their actions and reactions during the intervention; professional agency usually featured the teachers’ decisions and actions in changing their routine practices; students’ agency usually involved considerations of the student’s engagement with the changes in the organisation of learning. Relational agency included references to interaction, collaboration and joint work. The epistemic agency featured references to teachers’ engagement in professional teacher knowledge practices and facilitation of students’ engagement in science practices. presents examples of each theme.

Table 1. Coding for agentic practices.

The first author did the initial analysis, created a pool of quotes and created initial narratives describing the case. The second and third authors then reviewed and refined the interpretations until a shared agreement was reached. Pseudonyms were used for the school and the individual participants.

5. Results: emerging agentic practices

The results are organised into two sections to describe school-based teacher professional learning as a complex system and show emerging agentic practices. The first section describes the system’s main agents and other elements and their features. Particularly those features that contributed to productive outcomes. Then the next section presents the teachers’ reflections on the collaborative curriculum design and our interpretation of the emerging practices from the complex systems and agency perspectives. This text is organised to show interactions between agencies and feedback loops contributing to the emerging outcomes.

5.1. School context, participants and enabling conditions

The school, Castle Rock High School, is a co-educational school in a suburb of a city. Almost all students (93%) at this school were identified as having a language background other than English, and 68% of students reported family incomes in the bottom quarter of the socioeconomic status. From a systems perspective, the culture in the school promoted teachers’ professional learning to improve the quality of the pedagogy directed towards student success.

There were two groups of participants: the students and the three teachers, the Head of the Science Department, Priya, the ELL specialist teacher, Jake, and the science teacher, Roberto. In their expression of interest, the teachers stated that collaboration to support ELL pedagogy was their main aim for the project. They also wanted to be able to share their insights with other teachers. These statements suggested that these teachers already had a sense of professional agency at the beginning of the project.

All 28 students in the selected class had been identified as needing additional support to develop their language. Most students had been in this mainstream class for two school terms (twenty weeks); two had recently transferred from an Intensive Language Centre. There was a range in the students’ language proficiencies: two students were assessed to have very low levels of English (being able to read and write simple texts), and eight were assessed to be able to read and understand texts at the literal meaning. Overall, there were six language groups within the class. Most students spoke either Dari or Arabic, but two did not share a language background with the other students. The school widely acknowledged that this was not easy to teach the class. At the beginning of the project, the student agency did not support a quality learning environment, as the teachers reported that some students were displaying problematic behaviours.

The headteacher, Priya, provided the leadership for the project. This was Priya’s second year as the Head Teacher of Science. She perceived her role in the project as providing support, encouragement, and direction. Her agentic practices were primarily directed towards the relational aspects.

pretty much looking at the project from the outside and providing my support instead of being in the classroom as much and being hands-on with the kids (Head Teacher Science, Priya, Informal presentation to peers)

Nevertheless, her agentic practices had visible epistemic features. She was an advocate of applied, focus on real-world challenges, teaching:

Most of the programs that we have at this school - is not very contextual, and we are moving towards doing that because it provides a lot more engaging field for the students. It provides them a relationship to the real world and to problems that they might experience in the world. … .

The idea that we’re. presenting problems to students - I think that is a powerful way of teaching because most of the time, if you go back to the traditional style of teaching, what you do is you present a concept, but then the application is tagged at the end (Individual Interview)

Priya’s emphasis on engaging students through meaningful problems at a level of school programs reflected her enactment of the bounded agency and her commitment to enhancing students’ agency through their engagement in meaningful epistemic practices that she brought to the project.

Priya selected Roberto to participate in the project as she hoped this initiative would support the development of his professional agency towards enhancing students’ epistemic agency.

To experience using good pedagogy and to have successes with that, and I think this project was a really good base for him [Roberto] to actually use those pedagogies and to try and see how powerful they can be (Head Teacher, Priya, Individual Interview).

The science teacher, Roberto, had been teaching for four years. Based on his prior professional learning and school experiences, he stated that he could use his ‘communication skills and different key parts in ELL [pedagogy] and particularly mode continuum’ in their brainstorming to prepare for the different activities within the unit. When commenting on how the project had contributed to developing his professional knowledge, he responded with insights showing that this intervention changed his perception of how Science could be taught to all students and enhanced his professional agency in relational (e.g. recognising students’ needs) and epistemic (e.g. how to support students) terms.

So it has impacted my teaching in terms of I can see that the benefit is there. Not just for ELL students, but all students need some sort of support, particularly in this school where there is such variety in the capabilities of our students. So it really can help to support those students needing that scientific investigation knowledge and technical language (Roberto, Science Teacher, Individual Interview).

The ELL teacher, Jake, was experienced, having taught for eight years. He described himself as ‘relatively scientifically literate’ with sufficient knowledge to write the model answers and develop learning resources at the student’s language level. However, he acknowledged a limit to his scientific knowledge and expected his colleague Roberto to tweak the resources he developed to check the science content. This showed that Jake’s epistemic agency in science was limited, but he had relational agency to recognise Roberto’s expertise. Jake’s professional agency supported students’ learning and epistemic agency in science. He perceived that effective Science teaching should move students beyond rote recall rather than focusing on developing students’ technical language and their understanding and skills for the productive use of their knowledge.

I guess the whole point of [how to support ELL students learning] is… one, they get the technical language. Two, they understand the variables. Three, how we structure each component of the scientific investigation, which gives them that writing skill to use for a scientific report. Then, four, using those analysing skills to then evaluate the information of what they’ve just done in a way that they can put into the real world (Jake, ELL teacher, Focus Group Interview)

The school’s recognition of teachers’ effective collaboration for their professional learning and structured program enhanced teachers’ bounded agency. The time provided by the school allowed the ELL teacher, Jake, to reorganise his timetable so that there was sufficient for co-planning and co-teaching in the unit. The team met regularly before and for the ten weeks of the intervention; this planning time allowed them to develop a coherent lesson sequence.

Well, I guess I really appreciate the project in the sense that it gave structure to our team teaching. I mean, often, the team-teaching process could be a little bit - I mean, there is planning restrictions. Without this sort of structure, we often don’t get the chance to meet and plan and whatnot, … . so we had time to plan the project from the outset, from before the topic commenced with the kids, and we had this broad view of where we are going together which was great (ELL teacher Jake, Individual Interview).

6. Agentic decisions in collaborative curriculum redesign

The next topic in the school program, the Chemical Classification of Materials, was identified as challenging. It was mostly theoretical with limited reference to students’ everyday life, thus providing limited opportunities to support the students’ epistemic agency development. The idea of overheating a mobile phone was developed in a brainstorming session with the university partners. The teachers used this context to create an issue for their students; why the latest ‘iPear’ mobile phone model is overheating, and what they could recommend the company directors do to remedy the situation. This small curriculum transformation provided a mechanism to enhance the students’ epistemic agency as it positioned them as scientists addressing a possible problem with a familiar object.

We don’t want it just as a very tokenistic element at the end; we want it to be integrated throughout the curriculum throughout the term. So a lot of the resources where I could try to develop them with that in mind. We did a series of experiments to scaffold the report writing process related to different problems that we came up with related to phones (Jake, ELL teacher, Focus group).

There were three key aspects associated with the curriculum redesign. The first was teachers’ flexibility in choosing what to teach. This resulted in the team’s agentic decision that reducing some of the content covered would provide time for students’ development of their language and higher-order skills for student epistemic agency.

Some of the content we did have to let go in the sense that it wasn’t probably taught in as much detail as we would have if we just stood in front of the class and gave five worksheets out. In that sense, right? But having said that, the focus was on problem-solving and scientific thinking (Head Teacher Science, Priya, Informal presentation to peers).

The teachers’ next consideration was several effective epistemic decisions to embed the language support. The student’s educational backgrounds meant that the language and processes of the science practices, such as planning, conducting, and communicating fair test results, were identified as linguistically challenging and conceptually demanding. A series of activities based on problems with the ‘iPear’ gave the students multiple opportunities to develop their understanding of the processes of science.

For the first couple of … lessons, they had to be really well supported in terms of identifying those [variables]. They basically had to have it given to them. Gradually, as that went on, they were able to identify variables on their own, as well as the other – and construct tables when we get further through the process and graphs into the results (Jake, ELL teacher, Focus group Interview).

As the students’ language development increased in the second part of the unit, these science concepts and problem-solving were introduced.

Then we slowly introduced to the problem-solving aspect, also the resistance and heat of the wires. They were able to grasp that. I was quite impressed too. Particularly being, one an ELL class where they’re getting lots and lots of new words. But also the concept of what was happening in terms of the heat that’s being generated (Roberto, Science Teacher, Focus Group Interview).

Concurrently, group work and more hands-on activities were implemented.

While we were making up this unit, we thought we really needed to get students to make sure that they are taking responsibility for the various aspects of working together in a classroom (Head Teacher Priya, Informal Presentation to her peers)

The students’ groups were provided with a summary of the roles and responsibilities to be carried out by the different team members in a research team. Students were expected to swap roles at the end of each lesson, and a checklist was provided to support students’ reflection on developing their group work skills. The use of group work promoted student epistemic agency; it also appeared to have contributed to their language development.

I think that was a really important aspect and just building up those communication skills for the ELL students and, by way of doing so, improving their technical language (Science teacher, Roberto, Individual Interview)

The combination of group work and problem-solving as the basis for the organisation of the unit were recognised as having a positive impact on students’ language development and the emergence of new relational and epistemic student agentic practices. In the informal presentation midway through the project, the ELL teacher commented:

We saw them have probably more engagement through this project, more ownership, more opportunities for them to be active participants in the lesson and practise their communicative skills. … . It was really good to see them have lots of opportunities to revisit the experimental report writing process and to be able to see the progress they were making through those multiple visits was really good as well (Jake, ELL teacher, Informal Presentation).

The relational agency amongst the teachers appeared to be fundamental and was strengthened within this collaborative curriculum re-design. The Head Teacher, Priya, clearly articulated what she perceived as the importance of this collaboration.

Working together, I have felt that that was an area that we really needed to work on and to actually be able to see the importance of it, and sometimes working through it gives you that importance (Priya, Head Teacher Science, Individual interview)

All lessons were co-taught, allowing the teachers to monitor the student’s learning and adjust their approach, to match the changes in students’ behaviours.

Even though they [the students] may not get all the words – and you can always tell that some students may not be getting everything – but when we go back over them, we’re reinforcing; you can see that they are picking up individual words (Roberto, Science teacher, Individual Interview)

Finally, this initiative provided visible feedback at the school level of the system. First, it provided a specific example of a new teaching method for the other teachers, which, the headteacher Priya believed, impacted the other science teachers’ professional and bounded agency.

I think every time someone is heavily focusing on a particular area of teaching or a particular strategy or pedagogy, everyone around you gets motivated and inspired from that and starts reflecting on their practice as well. I think everyone in the staffroom has heard enough of Roberto and I talking about it – and everyone’s pretty much reflected on their teaching and maybe thought, oh, maybe I can do something like that, or maybe I can use this particular strategy … It allows for more professional dialogue within the faculty, and it provides for good examples of teaching as well (Priya, Head Teacher Science, Individual Interview).

Second, the project created a new professional collaboration model between ELL specialists and classroom teachers. Jake, the ELL teacher, believed that this led to more effective use of his time working with discipline specialists rather than what he termed the ‘hit and miss approach’ when there was no preplanning about the organisation of a lesson:

afforded a greater realisation of how the subject specialists and the ELL specialist can work together to tackle both the literacy needs as well as the content needs of the students and how work can be perhaps scaffolded to cater for some of those literacy needs (Jake, ELL teacher. Individual Interview)

Finally, when asked, ‘What did he do differently in this project?’ the science teacher Roberto responded.

R: I gave them more responsibility … . Which is very hard to do, but you have to in these particular projects where you’re relinquishing that control, but also in …

Facilitator [It is a bit terrifying, isn’t it].

R:It is, it is, and giving students autonomy. Yes, it was a very interesting moment for me, but we just decided to do it, and we did. So we gave them roles, we gave them responsibilities, and they met the challenge. I think that was really important.

His statement, ‘which is very hard to do’, highlights his perceptions of the risks of changing his previous teacher-centred approach to instruction. There appeared to be multiple interrelated causal factors contributing to him making this significant and unpredictable change in his teaching practice. First, the comment ‘we just decided … and we did it’ suggests that the relational agency between himself and Jake, the ELL teacher, enhanced through the project provided a level of support. Secondly was Roberto’s professional agency, where he tried out some language scaffolds with another less challenging class throughout the project. Next, being selected to participate in and throughout the project, the support from the headteacher enhanced his bounded agency. Finally, the changes in the classroom organisation enhanced the students’ agency, reducing classroom management issues.

Overall, the results show that the impact of this school-based professional learning program cannot be attributed to one specific cause or be measured by one specific outcome. Instead, decisions made by the individuals and the team of teachers produced multiple causal interactions leading to the changes in students and the teachers’ agentic practices within and across the levels of the complex system within the school.

7. Discussion and conclusions

It is hard to assess the impact of professional learning programs by examining direct relationships between specific features of program design and specific outcomes (Adams and Vescio Citation2015, Opfer and Pedder Citation2011). This paper brings a different perspective to this issue by proposing a framework that combines the constructs of complex systems and agentic practices. Rather than analysing direct causal links to explain the outcomes of a professional learning initiative, we consider teachers’ professional learning as a complex system that emerges from multiple activities and interactions within a particular context. The main premise of this framework is that teachers’ professional learning and practices are situated in a nested set of systems and subsystems (Pietarinen et al. Citation2016). The intentional actions and interactions among the participants occur in the different subsystems, and the outcomes of these interactions resonate across the system as a whole. The emergent phenomenon of teachers’ professional learning is multicausal, multilayered and multidimensional. Actions occur within and across the different subsystems; over time, these actions can impact the subsystems and the system (Strom and Viesca Citation2021). To examine the combinations contributing to the emergent phenomenon, the salient agentic practices in the system and the different subsystems need to be considered, as well as the feedback loops that strengthen or suppress changes in practices (Shaked and Schechter Citation2016, Daly et al. Citation2020). In this paper, we illustrated the usefulness of the agentic practices constructs by presenting a case study examining professional learning.

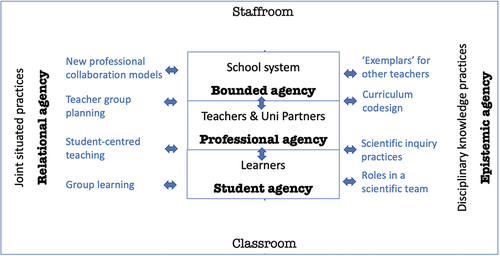

In the case study school, the emergent phenomena of the changes in the teachers’ professional learning and practices were evident in the changes in the classroom practices with a shift towards a more student-centred approach to learning based on inquiry-based instruction, the creation of a new model of professional learning and the creation of actionable knowledge of how to support ELLs in science across the school. depicts the emerging agentic practices in our analysed case. They are distributed across space (e.g. the staffroom and the classroom) and time, involving different agents. The impact of professional learning emerges from the agentic decisions within and between the levels of the system, (i) the learner, (ii) the teachers and university partners and (iii) the school system.

Figure 2. Emerging agentic practices in the school-based professional learning initiative: the analysis of the case.

In our analysis of this largely school-based professional development initiative, we considered the whole school to be the highest level of the system. At this level, the main affordance contributing to the emergent phenomenon was a culture that recognised and supported changes in pedagogical practices. The time provision enhanced the teachers’ bounded, relational and epistemic agency. From the relational perspective, the time enabled the teachers’ joint planning, resulting in a new model of professional collaboration within the school. From the epistemic perspective, giving teachers the authority to select and change the curriculum content and organise and assess the students’ learning resulted in a new professional knowledge practice evident in the curriculum co-design. At the school level, the outcomes of the team’s co-creation of knowledge served as an exemplar for other teachers. While previous research has shown that school cultures that support teacher collaboration are important in teachers’ professional learning (Darling-Hammond and Richardson Citation2009, Capps et al. Citation2012, Postholm Citation2012, Whitworth and Chui Citation2015), the application of a theoretical framework of complex systems and agentic practices provide nuanced and specific insights into how these factors result in new agentic practices that characterise the outcomes of a professional learning initiative.

Critical to the professional learning outcomes of this project was the agency enacted in the formal and informal meetings among the teachers (Brodie Citation2021). Through their interactions, the teachers built on each other’s knowledge to create appropriate modifications to the curriculum. These changes to the curriculum were implemented within the classroom, where new relational and epistemic practices: student-centred teaching and students’ engagement in scientific inquiry. From the relational perspective, the teachers’ recognition of the student’s needs and capacities and their decision to promote their students’ responsibility for their learning resulted in the adoption of group work. From the epistemic perspective, teachers’ decision to position students as a team of scientists resulted in more authentic epistemic practices at the student agency level. No changes would have been possible without the professional agency of the individual participants, the teachers, and the university partners.

An individual case study restricts the generalisation of these specific insights. Nevertheless, it illustrates the usefulness of the proposed framework as an analytical tool. Its main strength is that it provides insights into interconnections between different aspects that emerge from and contribute to the outcomes of the professional learning initiative.

Overall, the proposed innovative theoretical framework that combines complex systems and agentic practices provides a method of examining the complex interrelationships and practices emerging from the professional learning initiative. Applying this framework in a case study school illustrates how particular agentic practices arise within and across the levels of the system and how they contribute to the outcomes of a professional learning initiative. Finally, it clarifies why the synergistic interactions among these agentic practices need to be considered in understanding the outcomes of the professional learning initiatives.

Acknowledgement

This paper is based on the project Funded by the NSW Department of Education Equity Unit and Centre for Educational Statistics and Evaluation. We acknowledge the contributions of Elizabeth Campbell, Maya Cranitch, Nell Lynes, Michael Michell, Eveline Mouglalis, Gillian Pennington, Megan Pursche, Patricia Stockbridge, Gaby Stooke, and Margaret Turnbull, who contributed to the professional development program and data collection and gave feedback on early versions of the presented framework. We also want to acknowledge the contributions of all the teachers in this study and the reviewers who provided valuable feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adams, A. and Vescio, V., 2015. Tailored to Fit: Structure Professional Learning Communities to Meet Individual Needs. Journal of Staff Development, 36 (2), 26–28.

- Ardasheva, Y., Norton-Meier, L., and Hand, B., 2016. Negotiation, embeddedness, and non-threatening learning environments as themes of science and language convergence for English language learners. Studies in science education, 51 (2), 201–249. doi:10.1080/03057267.2015.1078019.

- Biesta, G.J.J., Priestley, M., and Robinson, S., 2015. The role of beliefs in teacher agency. Teachers & Teaching: Theory & Practice, 21, 624–640.

- Biesta, G. and Tedder, M., 2007. Agency and learning in the life course: towards an ecological perspective. Studies in education of adults, 39 (2), 132–149. doi:10.1080/02660830.2007.11661545.

- Bleijenbergh, I., 2010. Case selection. In: A.J. Mills, G. Durepos, and E. Wiebe, eds. Encyclopedia of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 64–63.

- Brodie, K., 2021. Teacher agency in professional learning communities. Professional development in education, 47 (4), 560–573. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1689523.

- Buxton, C., et al., 2013. Using educative assessments to support science teaching for middle school English-language learners. Journal of science teacher education, 24 (2), 347–366. doi:10.1007/s10972-012-9329-5.

- Buxton, C., et al., 2015. Teacher agency and professional learning: rethinking fidelity of implementation as multiplicities of enactment. Journal of research in science teaching, 52 (4), 489–502. doi:10.1002/tea.21223.

- Capps, D., Crawford, B.A., and Constas, M.A., 2012. A review of empirical literature on inquiry professional development: alignment with best practices and a critique of the findings. Journal of science teacher education, 23 (3), 291–318. doi:10.1007/s10972-012-9275-2.

- Chaaban, Y., 2017. Examining changes in beliefs and practices: English language teachers’ participation in the school-based support program. Professional development in education, 43 (4), 592–611. doi:10.1080/19415257.2016.1233508.

- Clarke, S.N., et al., 2016. Student agency to participate in dialogic science discussions. Learning, culture & social interaction, 10, 27–39. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2016.01.002.

- Cummins, J., 1989. Language and literacy acquisition in bilingual contexts. Journal of multilingual and multicultural development, 10 (1), 17–31. doi:10.1080/01434632.1989.9994360.

- Daly, C., Milton, E., and Langdon, F., 2020. How do ecological perspectives help understand schools as sites for teacher learning? Professional development in education, 46 (4), 652–663. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1787208.

- Damsa, C.I., et al., 2010. Shared epistemic agency: an empirical study of an emergent construct. Journal of the learning sciences, 19 (2), 143–186. doi:10.1080/10508401003708381.

- Darling-Hammond, L. and Richardson, N., 2009. Teacher learning. Educational leadership, 66 (5), 46–53.

- Dobbs, C., Ippolito, J., and Charner-Laird, M., 2016. Creative tensions turn the challenges of learning together into opportunities. Journal of staff development, 37 (6), 28–31.

- Dogan, S., Pringle, R., and Mesa, J., 2016. The impacts of professional learning communities on science teachers’ knowledge practices and students learning: a review. Professional development in education, 42 (4), 569–588. doi:10.1080/19415257.2015.1065899.

- Edwards, A., 2011. Building common knowledge at the boundaries between professional practices: relational agency and relational expertise in systems of distributed expertise. International journal of educational research, 50 (1), 33–39. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2011.04.007.

- Ell, F., 2019. Complexity theory as a guide to qualitative methodology in teacher education Oxford research encyclopedias [online]. [Accessed 12 Feb 2022]. Available from: https://oxfordrecom.ezproxy.library.sydney.edu.au/education/view/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.001.0001/acrefore-9780190264093-e-523?print=pdf

- Evans, K., 2007. Concepts of bounded agency in education, work and the personal lives of young adults. International journal of psychology, 42 (2), 85–93. doi:10.1080/00207590600991237.

- Fox, A., Deaney, R., and Wilson, E., 2010. Examining beginning teachers’ perceptions of workplace support. Journal of workplace learning, 22 (4), 212–227. doi:10.1108/13665621011040671.

- Fu, G. and Clarke, A., 2019. Moving beyond the agency-structure dialectic in pre-collegiate science education: positionality, engagement, and emergence. Studies in science education, 55 (2), 215–256. doi:10.1080/03057267.2020.1735756.

- Garner, J.K. and Kaplan, A., 2021. A complex dynamic systems approach to the design and evaluation of teacher professional development. Professional development in education, 47 (2–3), 289–314. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1879231.

- Greeno, J.G., 2006. Learning in activity. In: R.K. Sawyer, ed. The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 79–96.

- Hand, B., et al., 2010. Connecting research in science literacy and classroom practice: a review of science teaching journals in Australia, the UK and the United States, 1998–2008. Studies in science education, 46 (1), 45–68. doi:10.1080/03057260903562342.

- Harrison, H., 2017. Case study research: foundations and methodological orientations. Forum: qualitative social research, 18 (1), 1438–5627. doi:10.17169/fqs-18.1.2655.

- Kauppinen, M., et al., 2020. Professional agency and its features in supporting teachers’ learning during an in-service education programme. European journal of teacher education, 43 (3), 384–404. doi:10.1080/02619768.2020.1746264.

- Kelly, N., et al., 2019. Co-design for curriculum planning: a model for professional development for high school teachers. Australian journal of teacher education, 44 (7), 84–107. doi:10.14221/ajte.2019v44n7.6.

- Lee, O., et al., 2019. Science and language integration with English learners: a conceptual framework guiding instructional materials development. Science education, 103 (2), 317–337. doi:10.1002/sce.21498.

- Le Fevre, D.M., 2014. Barriers to implementing pedagogical change: the role of teachers’ perceptions of risk. Teaching & teacher education, 38, 56–64. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2013.11.007

- Levy, S. and Wilensky, U., 2008. Inventing a “Mid Level” to make ends meet: reasoning between the levels of complexity. Cognition & instruction, 26 (1), 1–47. doi:10.1080/07370000701798479.

- Lyon, E.G., et al., 2018. Improving the preparation of novice secondary science teachers for English learners: a proof of concept study. Science education, 102 (6), 1288–1318. doi:10.1002/sce.21473.

- MacSwan, J., 2020. Academic English as standard language ideology: a renewed research agenda for asset-based language education. Language teaching research, 24 (1), 28–36. doi:10.1177/1362168818777540.

- Markauskaite, L., Goodyear, P., and Sutherland, L., 2021. Learning for knowledgeable action: The construction of actionable conceptualisations as a unit of analysis in researching professional learning. Learning, Culture & Social Interaction, 31, 100382. doi:10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100382

- Miller, E., 2009. Teaching refugee learners with interrupted education in science: vocabulary, literacy and pedagogy. International journal of science education, 31 (4), 571–592. doi:10.1080/09500690701744611.

- Miller, E., et al., 2018. Addressing the epistemic elephant in the room: epistemic agency and the next generation science standards. Journal of research in science teaching, 55 (7), 1053–1075. doi:10.1002/tea.21459.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2018. English learners in STEM subjects: transforming classrooms, schools, and lives. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. doi:10.17226/25182

- Opfer, V.D. and Pedder, D., 2011. Conceptualising teacher professional learning. Review of educational research, 81 (3), 376–407. doi:10.3102/0034654311413609.

- Pickering, A., 1995. The mangle of practice: time, agency, and science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Pietarinen, J., Pyhältö, K., and Soini, T., 2016. Teacher’s professional agency – a relational approach to teacher learning. Learning: Research and practice, 2 (2), 112–129. doi:10.1080/23735082.2016.1181196.

- Postholm, M.B., 2012. Teachers’ professional development: a theoretical review. Educational research, 54 (4), 405–429. doi:10.1080/00131881.2012.734725.

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S., 2015. Understanding teacher agency: what is it and why does it matter? In: J. Evers and R. Kneyber, eds. Flip the system: changing education from the ground up. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 19–35.

- Reid, K. and Kleinhenz, E., 2015. Supporting teacher development: a literature review. Canberra: Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade.

- Schneider, M., Huss-Lederman, S., and Sherlock, W., 2012. Charting new waters: collaborating for school improvement in U.S. high schools. TESOL journal, 3 (3), 373–401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/tesj.26.

- Shaked, H. and Schechter, C., 2016. Holistic school leadership: systems thinking as instructional leadership enabler. NASSP Bulletin, 100 (4), 177–202. doi:10.1177/0192636516683446.

- Shaked, H. and Schechter, C., 2019. Systems thinking for principals of learning-focused schools. Journal of school administration research and development, 4 (1), 18–23. doi:10.32674/jsard.v4i1.1939.

- Strom, K.J. and Viesca, K.M., 2021. Towards a complex framework of teacher learning-practice. Professional development in education, 47 (2), 209–224. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1827449.

- Sutherland, L., 2021. Science and Language, lessons from curriculum co-design. Teaching Science, 67 (4), 41–54.

- Voogt, J., et al., 2015. Collaborative design as a form of professional development. Instructional science, 43 (2), 259–282. doi:10.1007/s11251-014-9340-7.

- Whitworth, B.A. and Chui, J.L., 2015. Professional development and teacher change: the missing leadership link. Journal of science teacher education, 26 (2), 121–137. doi:10.1007/s10972-014-9411-2.