ABSTRACT

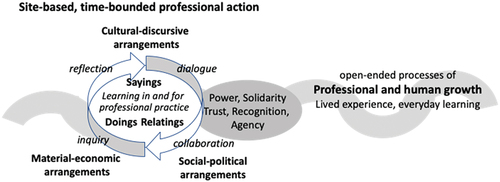

Based on an overview of the existing literature, this paper aims to provide a holistic and coherent conceptualisation and understanding of the complexity of educators’ professional learning. First, the way in which professional development, professional learning and everyday learning have been configured in contemporary research is combined with an initial practice theory perspective. Consequently, we conceptualise professional learning as learning in and for professional practice. Subsequently, the theory of practice architectures, a practice theory developed in educational settings, is presented. Based on the authors’ previous work, aspects of relatings, that is, the social space in which educators relate to each other in the mediums of power and solidarity, are highlighted. These include power, trust, recognition and agency. The paper ends by presenting a framework for understanding the complexity of learning in and for professional practice, consisting of two complementary perspectives: a site-based and time-bounded focus on professional action and an open-ended process of educators’ professional and human growth. Brought together these perspectives enable an understanding of the complexity of professional learning in terms of praxis development.

Introduction

Education supports human growth and development and is not limited to the acquisition of knowledge and skills. Similarly, professional learning is about personal growth and the development of morally committed professional actions. Education happens in intersubjective spaces, in which the persons involved encounter one another, engage with each other, learn and grow as human beings in a mutual relationship (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, p. 5). The same is true for professional learning. Our aim in this article is to provide a holistic and coherent conceptualisation and understanding of educators’ professional learning – a framework for understanding professional learning in terms of praxis development. Praxis refers to morally committed professional actions (Kemmis and Smith Citation2008, p. 4). As praxis, professional learning should model and foster a good life (in the Aristotelian sense), both for those involved in it as well as for humankind. This means enhancing possibilities to live well in a world worth living in (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, pp. 25–26).

This article builds on our previous work, based on an overview of research on professional learning conducted in an international PEP (Pedagogy, Education and Praxis) network. Informed by the theory of practice architectures, a review of empirical studies on professional learning underlined the importance of relatings, that is, the social space in which educators relate to each other in the mediums of power and solidarity (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Professional learning was found to be worthwhile when educators had the agency to act based on their professional values, ethics, experience and competencies. The social-political arrangements furthering agency were based on mutual trust and recognition. Meanwhile, professional learning was built on exploring, articulating and strengthening professional practices using collegial dialogues, collaboration and collective inquiry, organised in the form of research circles, action research and mentoring (Olin et al. Citation2020, pp. 155–158).

A multitude of adjacent and overlapping concepts are used for delineating and defining the complex phenomenon of professional learning (Kennedy Citation2014, Aharonian Citation2021, Mockler Citation2022). Research on educators’ learning and development has often been conducted in individual contexts, using models that are relevant to the specific context. Our aim is to provide a coherent framework for conceptualising and understanding professional learning from a practice perspective and relate it to educators’ learning in the light of their work as a whole. The framework is informed by and builds on the theory of practice architectures. The theory of practice architectures is a site-based practice theory with a focus on the arrangements in a site that enable and constrain particular practices (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, pp. 31–40). We use the theory of practice architectures and focus particularly on social-political arrangements, that is, the intersubjective and relational aspects of professional learning. These arrangements include power, solidarity, trust, recognition and agency. Further, based on research on professional learning, the framework recognises two interconnected aspects of time: time as a resource and an open-ended flow (Bergson Citation2001, Blue Citation2019). The framework does not focus on policy and learning outcomes as conditions for professional learning, however we do relate to both when theorising about how learning and development practices evolve and are supported or constrained by them.

This article proceeds in the following way. We begin with an overview of existing literature related to educators’ professional learning, drawing on reviews of research in the field and on frameworks developed in relation to professional learning and development. Next, we briefly present the theory of practice architectures and the five presuppositions for using the framework. Specific concepts from the theory are highlighted, which we draw these together to outline our framework for theorising about professional learning, with a focus on professional learning in and for practice.

We use the term ‘educators’ to refer to all practitioners who support the learning of others. This includes teachers, leaders in various positions in education, trainers, academics and those with a role of supporting the learning of others in the workplace.

Review of the research on professional learning

Until the turn of the millennium, the concept of professional learning was widely used to communicate an active and expansive notion, encompassing a wide range of practices and processes through which educators can reflect on, refine and expand their professional practice and deepen their commitment to development. Characteristic of this research in the 1980s and 1990s (Day Citation1999, Villegas-Reimers Citation2003, Mockler Citation2013) was situational, contextual and ecological perspectives and understandings of professional learning, with an interest in educators’ personal and professional growth. During the last two decades, the discourse has been, with some exceptions, a narrower one, in which the concept of professional development has been viewed in an individualistic, decontextualised and outcome-driven deficit way, and educators have been construed as lacking professional competencies to improve the learning outcomes of their students (Hardy Citation2010, Aharonian Citation2021; Sancar et al. Citation2021, Mockler Citation2022). Theoretically, research on professional learning has mainly relied on simplistic path models, aimed at identifying the efficient process or contextual variables to be used for causal explanations and measuring the effects or outcomes of a certain kind of professional learning activity (Opfer and Pedder Citation2011, Boylan et al. Citation2018). Thus, the relationship between professional learning practices and the intended improvement of teaching practices has been approached in a linear, dualistic and transactional manner (Strom et al. Citation2021, pp. 199–200). Research on professional learning or development in educational settings has often been conducted without clear definitions or operationalisations of the concepts in use. This has resulted in conceptual ambiguity and inappropriate understanding of the prerequisites, characteristics and features of the complex phenomenon under study.

Further, the quest for effective professional development has sprung from the establishment of quality requirements, professional standards and audit systems (Webster-Wright Citation2009; Zehetmeier et al. Citation2015, pp. 162–163, Mockler Citation2022). Still, it seems that the outcomes of this learning outcome-oriented body of research on professional learning have not been able to provide policymakers and educational administrators with accurate and generalisable knowledge on how to promote and support educators’ professional learning (Muijs et al. Citation2014, p. 249, Sancar et al. Citation2021, p. 2). Research has often been limited to the micro context, where classroom activities or face-to-face instructional practices between educators and students are handled as closed systems or decontextualised social entities (Boylan et al. Citation2018, pp. 122–128). As a result, the power of the multitude of contexts of teaching and learning practices, as well as the ubiquity of interactions, are ignored.

There are some exceptions to the atheoretical handling of professional learning described above. Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011) use a complexity and systems theory framework with three nested and reciprocal subsystems (the individual teacher, the school and the learning activity system) in reviewing the literature on professional learning practices. Their conceptualisation of professional learning as a complex system recognises the interplay between various interconnected processes, mechanisms, elements and actions, whose interrelationships vary in scale and intensity depending on the situation and the context. Wenger (Citation1998, Citation2000) offers a coherent theory of learning as a social process, happening in communities of practice. The focus of this theory is on the relationship between individuals and the collective in terms of participation and identity formation.

Key categories and associated elements identified in the literature

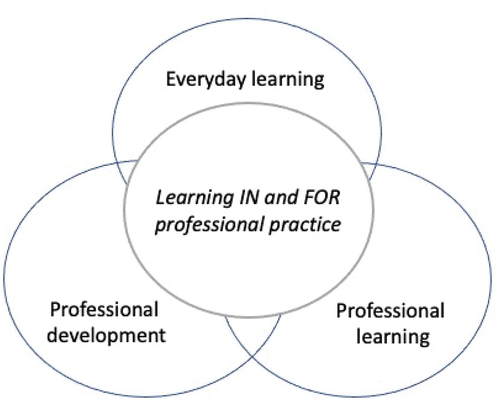

Our ambition to manage the complexity and ambiguity of professional learning led us to study and make meaning of reviews on various aspects, elements and contexts of professional learning. Overviews and literature reviews from the last decade have tended to result in an enumeration of categories and elements of professional learning ().

Table 1. Categories and elements of professional learning.

The extent to which models or overviews of professional learning rely on explicit learning theories vary (Boylan et al. Citation2018, pp. 129–130). In referring to explicit learning theories, the authors of the reviews listed above relate to cognitivist-constructivist (Villegas-Reimers Citation2003, Desimone Citation2009) socio-constructivist (DeLuca et al. Citation2015, Hallinger and Kulophas Citation2020) or social-cultural (Postholm Citation2012) learning theories.

Learning in and for professional practice

In the following, we begin to take adopt a practice theory viewpoint on professional learning. We do this with reference to the existing research and the central concepts relevant for a comprehensive understanding of professional learning. We will use learning in and for professional practice to encompass and assemble various conceptualisations, perspectives and focuses related to professional learning. In the literature, professional learning is described in a highly versatile manner, with reference to ‘forms’, ‘activities’ and ‘processes’ of learning, often intertwined with various ‘aims for’ and ‘outcomes’ of learning. The terms used are seldom defined and handled in a consistent manner. According to our understanding, they relate to phenomena that are anchored in, related to and aim at affecting educators’ professional practice. We consider professional practice as an open, dynamic and multifaceted phenomenon, affected by various interconnected practices. We define our understanding of ‘practice’ more explicitly later in this article.

From a practice theory perspective, learning is conceptualised as an ontological transformation of practices and understood both as ‘coming to participate differently in practice’ and ‘coming to practice differently’ (Kemmis Citation2021, p. 10). Educators’ learning ‘arises from, represents, recalls, anticipates and returns to its use in practices’ (Kemmis and Edward-Groves Citation2018, p. 120). Learning involves more than just the acquisition of knowledge and skills; it refers to the transformation or altered reproduction of a practice (Kemmis Citation2021, p. 11). Further, learning is manifested in three complementary ways: as being stirred or initiated into, as knowing how to go on in and as distancing oneself reflectively from a professional practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014Olin et al. Citation2020, p. 158, Rönnerman Citation2012).

Beyond the most used concepts, professional learning and (continuing) professional development, the concept of learning in and for professional practice has been applied to informal, workplace, incidental, authentic and everyday learning. These terms refer to educators as lifelong learners, with an inherent orientation to and interest in learning, an integral aspect of both developing as professionals and growing as human beings. The potential for learning is continuously present in human practice, both in educators’ work and in their personal lives beyond work.

Professional development

Most research on professional development (PD) or continuous professional development (CPD) has focused on training and programmes with predetermined aims, contents and structures, often only loosely coupled with the specific local contexts and sites. Studies using these terms concern context-specific initiatives, particular models or characteristics of effective PD or CPD as well as the impact of policies focusing on them (Kennedy Citation2014). Professional development relies on actions and processes that are structured and managed with regard to time, space, resources and support. It focuses on and is designed for updating educators’ capabilities and competences regarding specific aspects of their work, such as subjects or content knowledge, pedagogical skills or school-related themes. When organised in an expedient manner, professional development enables educators to respond to changes by providing them with the means to manage designated professional tasks and responsibilities. Professional development activities are often arranged as momentary or recurring training days/hours or workshops (Webster-Wright Citation2009, Hardy Citation2010).

Professional development is concordant with education development and educational reform. Within neoliberal educational policy contexts, it is driven by quality and performativity within frameworks of standards or professional regulation. As it is tightly coupled with learning outcomes and student performance, professional development relies on process – product logics and complies with the ideal of causality. Due to the lack of sensitivity to the characteristics of, and needs within, local contexts, professional development can become loosely coupled to individual professional practices at individual educational sites (Boylan et al. Citation2018, Mockler Citation2022). Still, some conceptualisations of professional development policies rely on democratic and collective perspectives on teacher professionalism and development, where educators are acknowledged as change agents advocating for social justice, and professional development is organised as coaching or mentoring or in terms of inquiry-based models (Kennedy Citation2014, pp. 694–695).

Professional learning

Professional learning is often anchored in a professional practice and focused on professional growth in relation to the specific occupational context. As mentioned above, Opfer and Pedder (Citation2011) highlight the situatedness and context dependence of professional learning. Clarke and Hollingsworth (Citation2002), employing a psychological learning theory of professional growth, argue for a non-linear structure of professional learning. They identify four interconnected domains: the domain of practice, the domain of consequences, the personal domain and the external domain. Professional learning extends beyond cognitive aspects to the practicing of the vocation. Further, professional learning in communities of practice emphasises the social and collaborative aspects of learning and development. Learning by practising together with others (Wenger Citation1998, Citation2000) builds on apprenticeship and has been expanded to, and applied within, various professional and organisational contexts. Professional learning has been conceptualised as a path to mastery built on participation, engagement, imagination and alignment. Norwegian educational researcher Løvlie (Citation1973) established the concept ‘practical knowledge regime’ as a conceptualisation of teachers’ reflective and development-oriented stance towards their professional practice. It was further developed by Handal and Lauvås (Citation2000) in the form of ‘practical professional theory’.

Considering educators as reflective practitioners equipped with practical professional theories is consistent with inquiry-based forms of professional learning, such as action research (Noffke Citation2009, Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Within this collaborative inquiry and development-oriented research tradition, professional learning refers to problem and needs-based, dynamic and open-ended long-term learning activities. It builds on professional experiences and prior knowledge, refined by processes of experimentation and reflection. Professional learning is informed and formed by local conditions and designed based on the characteristics of the educational site at hand. It is anchored in participation and engagement, relying on interaction, dialogue and collaboration. Collaborative and collegial practices are formed and sustained to promote and maintain professional learning (Edwards-Groves et al. Citation2018, Olin, Citation2020).

Everyday learning

Learning is a constant in educators’ professional practices and integral to their personal lives. Everyday learning occurs in planned and unplanned, conscious and unconscious and intentional and unintentional ways in the multitude of practices in which educators are engaged, including non-professional ones. Sometimes conceptualised as informal or incidental learning, everyday learning occurs spontaneously, even unreflectively, through engagement in a wide range of work-related practices and beyond them. Everyday learning includes interacting with and learning from others, practicing and experimenting, reflecting in and on action as well as encountering difficulties (Marsick and Watkins Citation1990, p. 12, Kyndt et al. Citation2016). Solomon et al. (Citation2006) refer to hybrid spaces, that is, physical and social environments in which socialising and sharing experiences with colleagues (e.g. during a coffee break or when sharing transportation to work) generate new ways of working, learning and being. Aharonian’s (Citation2021) study on teacher learning focuses on liminal spaces, understood as an interface of learning related both to teachers´ professional practices and personal lives. Liminal spaces are characterised by transformative learning, involving reflective processes of refined and deepened understanding. Personal learning experiences, emanating from activities intended for personal pleasure and recreation in teachers’ personal lives, lead them to reflect on and become aware of, for example, difficulties in learning something new (playing piano), internal control and responsibility (engagement in community development) or becoming stronger (perseverance in yoga). This supported greater understanding of their students´ difficulties and ambitions related to learning. These personal and reflective learning experiences are enriching and lead to profound changes on both the personal and professional levels – in other words, human growth and development (Aharonian Citation2021, pp. 769–775).

Webster-Wright (Citation2009, pp. 715–716) emphasises authentic professional learning, referring to educators’ lived experiences as they continue to learn as professionals throughout their lives. Authentic learning is complex, diverse and messy, but at the same time, rich, dynamic and filled with learning opportunities. It is situated and embedded within a multitude of professional practices and contexts. Landscapes of experiences and knowledge blend with personal, ethical, intellectual and social dimensions of work and life. Embodied knowing in practice, learning through experience and reflective action are essential to authentic learning.

The distinction between formal and informal learning practices is often used to identify and describe specific aspects of learning in and for professional practice (Hoekstra et al. Citation2009, Kyndt et al. Citation2016). With reference to Colley et al. (Citation2003) review, we find this problematic and unfruitful. First, the terms formal and informal learning are often used without distinctive definitions or with considerable overlap. Second, the boundaries between the ‘forms’ of learning are dependent on contexts and purposes. Third, when it comes to general orientation or specific situations, Colley et al. (Citation2003) recommend examining dimensions of formality and informality and their interrelatedness.

below brings together the concepts and perspectives discussed above. We conceptualise the practice in focus as learning in and for professional practice. This framework will be further elaborated below in relation to the theory of practice architectures. We will then present the presuppositions underpinning our work and focus on and elaborate two specific aspects: time and momentous relational dimensions.

The theory of practice architectures

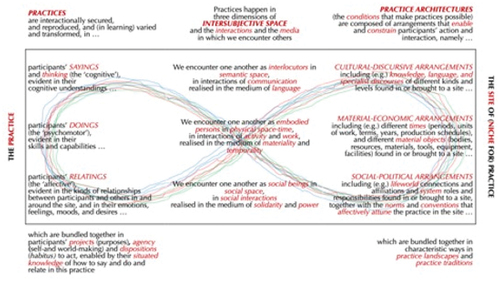

The practice turn in contemporary theory (Schatzki, Citation2001) represents a shift from theorising about the social (organisations, workplaces, schools, communities) to a focus on practices. In alignment with Lave (Citation2019), we argue that ‘it is not possible to discuss learning in practice without drawing directly or indirectly on its contextual character’ (p. 28). Practice has been defined in various ways by various practice theorists. In this article, we use the definition of practice adopted within the theory of practice architectures. We understand a practice as follows:

a form of human action in history, in which particular activities (doings) are comprehensible in terms of particular ideas and talk (sayings), and when the people involved are distributed in particular kinds of relationships (relatings), and when this combination of sayings, doings and relatings ‘hangs together’ in the project of the practice. (the ends and purposes that motivate the practice)

Thus, practices that support professional learning can be seen as forms of human action in which particular doings, sayings and relatings hang together in a particular project (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). The theory of practice architectures is a site-based, ontological theory that has a focus on practice. It is a theoretical, analytical and transformational resource for understanding and transforming practice (Mahon et al. Citation2017). The theory of practice architectures uses practice as the focus for investigating the social. In foregrounding practice, the theory acknowledges that ‘practice [is] a human and social activity with indissoluble moral, political and historical dimensions. Practice always forms and transforms the one who practices along with those who are also involved in and affected by the practice’ (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, p. 25). People change practices, and practices in turn change people.

The theory of practice architectures considers the actions that are undertaken in a practice: the doings, sayings and relatings. These actions are prefigured, but not predetermined, by the practice architectures that are present, or brought into, a site: the cultural-discursive, the material-economic and the social-political arrangements.

Cultural-discursive arrangements occur in the semantic dimension, and they enable and constrain the sayings in a practice, that is, those things that are said and thought about in relation to a particular practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). For instance, the cultural-discursive arrangements in a university science faculty staff room include language that is specific to science, while in an engineering workplace it includes engineering-specific language.

Material-economic arrangements occur in the space/time dimension and enable and constrain the doings of a practice, that is, what is done and how it is done. They include the physical arrangements, the scheduling, the resources and the artefacts available at the site (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). For instance, the material-economic arrangements in a classroom might include chairs, tables, books, laptops and an electronic whiteboard as well as the scheduling of classes.

The social-political arrangements occur in the social dimension, and they enable and constrain the relatings in a practice, that is, the relationships between people. These arrangements include power and solidarity (Kemmis et al. Citation2014). Examples include the relationships of collegiality between educators.

provides a diagrammatic representation of the theory of practice architectures. The site of the practice is represented on the right of the diagram and is made up of the cultural-discursive, material-economic and social-political arrangements found or brought into a site. The practice is represented on the left and involves actions (doings, sayings and relatings). Individuals meet each other in the intersubjective spaces (the semantic, material and social). Research using the theory of practice architectures as the theoretical and/or analytical framework highlights the significance of social-political arrangements and relatings in the professional learning of educators (Edwards-Groves et al. Citation2016, Francisco et al. Citation2023).

Figure 2. The theory of practice architectures (adapted by Stephen Kemmis from figure 5.4 in Kemmis Citation2022, p. 97; used with permission).

Further, the social political arrangements and relatings are crucial for professional learning for praxis development. The concept of praxis is important as part of a broader understanding of the theory of practice architectures. Within this theory, praxis is understood in two ways, the first coming from a neo-Aristotelian tradition and the second from a Marxist tradition (Kemmis Citation2022). Praxis can be understood as acting for the good of each person and for humankind more broadly. It can also be understood as ‘history-making action’ (Kemmis Citation2022, p. 66). Framed by these understandings, at a broad level, we understand professional learning for praxis development as professional learning that enables educators to live well and to support the creation of a world worth living in for all (Reimer et al. Citation2023).

Presuppositions of the framework

In keeping with the theory of practice architectures, we take as a starting point the notion that learning in and for professional practice is a site-based practice enabled and constrained by the practice architectures at a site. Our first presupposition is that learning in and for practice is not entirely dependent on the dispositions and prior experiences of the individuals engaged in the practice at hand. By taking a practice approach, we foreground the practices and practice architectures that prefigure the actions of the people involved in the practice of learning in and for practice (Kemmis et al. Citation2014).

The second presupposition is related to the purpose of education. Drawing on Kemmis et al. (Citation2014, p. 27), we hold that education has a double purpose: ‘to prepare people to live well in a world worth living in’. Education prepares people for living a moral, ethical and satisfying life and enables people to create a world worth living in for themselves and for all humankind. Informed by the double purpose of education, our third presupposition is that learning in and for practice supports praxis development. We are not suggesting that all learning in and for practice is necessarily directly related to praxis development. Instead, we argue that learning in and for practice is intertwined with praxis development.

Our fourth presupposition is that learning in and for practice that supports praxis development is relational. It happens in intersubjective spaces. People are engaged with each other, and they learn, develop as professionals and grow as human beings through reciprocal relationships (Kemmis et al. Citation2014, p. 5). Learning in and for practice is enabled and constrained by the interrelationships of those engaged in the practice. In other words, it is collaborative.

Lastly, we argue that at each site, learning in and for practice is part of an ecology of practices (Kemmis et al. Citation2012). It is interrelated with other practices within the education complex, which may include teaching, learning, researching and leading. Which practices are interrelated at a particular site is an empirical question. In this article, we limit ourselves to a focus on learning in and for practice and maintain an awareness of its inter-relatedness with other practices in the education complex.

Time as a resource and open-ended flow

In our view, theorising about learning in and for professional practice requires recognising and building on two complementary aspects of time: time as a resource (an identifiable and observable material-economic arrangement) and time as an open-ended dimension of practices (a flow of actions, including past, present and future). In the literature on professional learning, time is mostly reconstructed as a material-economic arrangement. It is portrayed as a measurable and reified resource, to be used for professional activities and commitments. As a material-economic arrangement, time both enables and constrains various forms of professional learning. As noted by, for example, Bartlett (Citation2004) and Brante (Citation2009), educators’ work has become more complex, demanding and time intensive, resulting in role expansion, overwork and stress.

Researchers agree that purposive professional learning is dependent on time, both as a resource and possibility. Still, time is conceptualised in a variety of ways and referred to without further elucidation. According to Mockler (Citation2013, p. 36), educators need time to engage themselves in professional practices, in a way that allows them to refine, expand and transform these practices. Further, engagement in professional learning requires appointed time beyond teaching duties: time in the activity (e.g. one hour a week) as well as the duration of professional learning (e.g. one academic year) (Desimone Citation2009, p. 184). Time appointed needs to be organised in a manner that enables educators to prepare themselves mentally and plan the use of time in an expedient manner (Cordingley Citation2015, p. 243). To make the most of professional learning opportunities, timing is crucial. Educators need to be ready, focused and attentive (Cooper et al. Citation2020, pp. 569–570). Professional agency presupposes the freedom to decide and allocate time in a needs-based way (Kyndt et al. Citation2016, p. 1134). Finally, professional learning continues over time throughout educators’ professional lives (Sancar et al. Citation2021, p. 8). In sum, in the professional learning literature time has been considered in relation to the following: 1) time explicitly allocated to professional learning, 2) the timing of that allocation, 3) time set aside and used for professional learning, 4) the duration of professional learning and 5) timing in relation to the flow of professional lives.

Most of these ways of relating to time conceptualise it as a delimitable and measurable unit to be allocated and used as a resource. As Bergson (Citation2001) argues, time can be measured, somewhat objectively, in months and hours, but it also contains a succession with a before and after. In human experience time can be understood as a continuous open-ended flow. It has a duration that does not relate to succession, and it contains and consists of experiences of the past and the individual approach towards the future.

Time is central to practice-theoretical accounts of the social. Blue (Citation2019) distinguishes between time approaches, such as practices in time, time in practices and practices as time. Practices in time contain time as a scarce resource. Accordingly, practices must compete for time and space. Time in practice relates to practitioners’ experiences of time, for example, time shortages and the way in which time constrains and enables performances. Considering time as practice, Blue refers to Schatzki’s theory of the time-space of human activity. Schatzki (Citation2009) describes how a temporal experience of the past and ideas of the future define the present. Time-space activities interact in different projects through sets of doings and sayings that form social practices. Schatzki (Citation2010) considers time as the temporal process of social practices and argues that ‘a practice is defined as a temporal evolving, open-ended set of doings and sayings linked by practical understandings, rules, teleo-affective structures, and general understandings’ (p. 87).

With reference to the theory of practice architectures, we follow the conceptualisation of time as a temporal aspect of practice. Kemmis (Citation2019) argues that practice happens in intersubjective space in terms of dialectic relationships of the particular action-in-history of an individual person’s practices and the local and larger histories. Learning transpires in the plenum of practices as temporal, evolving, open-ended sets of saying, doings and relatings, evolving as history-making actions. Learning implies an ontological transformation of practices, beyond the standard view of learning as the acquisition of knowledge. Knowledge arises from and evolves in particular cultural, material and social settings. This happeningness of learning – which can be recognised as a temporal experience – may be described as a flow in and for praxis development. Thus, learning as a flow happens in the emerging here-and-now situation (history-making actions), from the perspective of history (experiences and knowing) and in the vision of the future (for a world worth living in).

Relational aspects on learning in and for professional practice

In the following, we will elaborate on the intersubjective and relational aspects of learning in and for professional practice, conceptualised in the theory of practice architectures as relatings, enabled and constrained by social-political arrangements. This will be done with reference to our earlier work on professional learning (Olin et al. Citation2020) and in relation to Kennedy’s (Citation2005, Citation2014) continuum of models of continuing professional development. We focus on her transformative model, characterised by an awareness of power, with the purpose of recognising conditions for transformative practice (Kennedy Citation2005, pp. 246–247). The transformation of professional practices presumes professional autonomy and agency (Kennedy Citation2014, p. 693). Within the theory of practice architectures, social-political arrangements constrain and enable relationships between people. Intersubjective spaces are realised in the mediums of power and solidarity. In addition to power, we will attend to trust, recognition and agency, the first two of which relate to the solidarity aspect of social-political arrangements.

Power

Power has been addressed from a range of perspectives and in a range of fields. Here, we focus on the literature related to power that enables or constrains actions in education. As a result of her research over three years with four principals, Fennel (Citation1999, p. 33) identified positive and negative power. She found the following themes related to positive power: ‘trust, respect and honesty; confronting issues; conflict as positive; power as serenity; power as relationships; power by example; power as learning; power as nurturing; power as energy’. Drawing on the work of others, she identifies three types of power operating in the school: power over, which she identifies as negative, power through and power with. Smeed et al. (Citation2009) argue that power over, power through and power with can be seen as part of a continuum. Allen (Citation1998) identifies power over, power to and power with. Power over refers to one person having power over the actions of another or others. In turn, Allen defines power to as ‘the ability of an individual actor to attain an end or series of ends’ (p. 34). Power to is synonymous with empowerment.

The concept of power through draws on the work of Dunlap and Goldman (Citation1991) and relates to what they call facilitative power. Facilitative power involves creating conditions that support the development of others. Specifically, it involves the following: ensuring the availability of material resources for educational activities; selecting and managing people to collaborate for developmental purposes; providing feedback and suggestions; and providing networks for activities, creating links between groups and supporting the sharing of ideas (Dunlap and Goldman Citation1991, pp. 13–14). This type of power is relational, as it is generated by ‘work[ing] through others rather than to exercise power over them’ (Dunlap and Goldman Citation1991, p. 14).

Power with has been understood and configured in various ways. Allen (Citation1998, p. 36) connects it with solidarity, defining it as ‘the ability of a collectivity to act together for the attainment of a common or shared end or series of ends’. Fennel’s (Citation1999, p. 27) characterisation of power with comes from her use of the concept in relation to school principals. She identifies it as relational and democratic, including ‘power together, power in connection, relational power and mutual power’. Smeed et al. (Citation2009) argue, from a leadership perspective, that a power with approach nurtures a high degree of trust.

In the theory of practice architectures, social-political arrangements are realised in social space in the mediums of power and solidarity. Within the theory, power is understood as including power with, power over, power to and power through. Solidarity can also be understood as a form of power with.

Trust

Trust, and specifically relational trust, has been identified as an important component of successful professional learning (Francisco et al. Citation2023). Early work by Bryk and Schneider (Citation2002) identifies relational trust as ‘essential for meaningful school improvement’ (p. 41), informed by extensive qualitative and quantitative research. They outline the following components of relational trust: interpersonal respect, personal regard, others’ competence in their role and personal integrity. Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer (Citation2021) as well as Edwards-Groves et al. (Citation2016) have also explored the concept of relational trust. Based on empirical work related to middle leaders, they identify five dimensions of relational trust: interpersonal, interactional, intersubjective, intellectual and pragmatic. Interpersonal trust takes time to develop and involves mutual respect. Francisco et al. (Citation2023) report that all other forms of relational trust rely on a solid basis of interpersonal trust. Interactional trust relates to open and ongoing interactions within the group, where people feel listened to and are willing to consider alternative perspectives. Intersubjective trust is based in equality and emerges through shared activities and the development of a shared language. Intellectual trust can be seen as having a basis in professionalism. Edwards-Groves and Grootenboer (Citation2021) identify wisdom, expertise and self-confidence as aspects related to intellectual trust. Pragmatic trust makes activities and agendas possible, insofar as they are realistic and practical. Relational trust sits within the social dimension and is developed over time.

Recognition

Recognition is a fundamental dimension of human relationships and underpins the potential to build trustful partnerships (Edwards-Groves et al. Citation2016). Mutual recognition of each other’s knowledge and competences is a necessary condition in relationships aiming for change and sustainable transformation of practice. Sound communication in a professional community builds on an interconnection between learning, transformation and recognition, nurturing both the development of practices and professional growth (Groundwater-Smith et al. Citation2013). Research on learning communities (Stoll et al. Citation2006) tends to focus on the characteristics of effective collaborative learning while overlooking how social and relational architectures both nurture and constrain the development of such learning communities, for example, how recognition affects individuals, partners and their relatings.

Being recognised is a core human need. In Honneth’s (Citation1995) view, the struggle for recognition forms the basis for social interaction and collaborative action. Ways of recognising and relating to each other characterise the intersubjective spaces and form the practice architectures for what is possible to say, do and accomplish. However, to be able to recognise and value the contributions of others, educators must be able to recognise and value their own knowledge and competences. The simultaneous occurrence of self- and mutual recognition enables transformative practices. According to Honneth (Citation1995), mutual recognition builds internal self-confidence, self-respect and self-esteem in people, all of which are prerequisites for agency and being agentic in society. The experience of self-confidence in the realm of mutual recognition promotes a culture in which differences are recognised as strengths and human beings are regarded as equals. Differences become a source for learning, and mutual recognition enables risk-taking to transform practices (Edwards-Groves et al. Citation2016).

In a study on teachers’ and researchers’ collaborative learning in school development projects, Olin and Pörn (Citation2021) describe how the teachers came to recognise the importance of their knowledge to being recognised by the researchers as partners and valued contributors. In the initial stages of the collaboration, teachers avoided topics and actions that they did not feel knowledgeable about. Over time, they realised that their professional experiences and knowledge, which differed from those of the researchers, were necessary for reaching their common aims. Consequently, they became confident in bringing up new ideas and deepening their reasoning. Dialogues in which neither the teachers nor the researchers appeared to be knowledgeable nurtured mutual learning and knowledge creation, facilitating the transformation of their professional practices.

Agency

Professional agency has been conceptualised within various ontological, epistemological and methodological approaches. Agency is seldom included in models of professional learning, and at times it is only vaguely implied (Boylan et al. Citation2018). From an individualistic perspective, agency refers to educators’ power to act and choose their actions within their domain of expertise (Heikkilä Citation2022, p. 2). However, according to Emirbayer and Mische (Citation1998), such an individualistic view on agency based on instrumental rationality ignores norms, traditions and structures. Heikkilä (Citation2022, pp. 2–3) refers to recent research on agency based on a linguistic and post-structural approach, questioning whether subjects are autonomous beings capable of purposeful choices. In social theory, agency is understood as a complex social and interactive phenomenon, in which purposeful activity on the micro level is linked to social and political macro-level activities (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998).

Priestley et al. (Citation2015), using an ecological practice perspective, understand agency as emerging in the interplay of individual and environmental circumstances. Besides individuals and their capacity to act, they focus on contextual factors, such as culture, social relationships and material structures. Teachers’ actions are considered reflexive and creative, affected by the conditions and prerequisites in the situations in which the action takes place. Agency manifests as intentional action and is guided by a purpose or intention. Potential action alternatives are formulated thereafter. Priestley et al. (Citation2015, p. 23) find that teachers’ beliefs and knowledge, their striving, language and discourses, their relationships as well as the demand for performativity are formative of agency. Educators thus need to balance between the various dimensions of their professional practice and be conscious of the possibilities to act according to their professional judgement in a given situation.

In summary

A framework for theorising, analysing and enacting learning in and for professional practice needs to acknowledge the complexity and multidimensionality of education, educational change and school development and emphasise the intersubjective character of these human endeavours (see below). Learning in and for professional practice involves two intertwined time-spaces. It can be studied and understood as time-bounded, site-based professional action, to be observed and analysed in terms of interrelated sayings, doings and relatings, enabled and constrained by material-economic, cultural-discursive and social-political arrangements. Still, the time-bound, site-based professional learning practices both presuppose and cause various forms of open-ended processes of professional and human growth, both of an individual and intersubjective nature.

In times of multiple local and global challenges – crises – praxis development assumes a transformative agenda. In our experience, this calls for approaches like action research, which relies on a systematic and critically self-reflective collaborative professional inquiry, based on partnerships and communicative spaces between educators and professionals from various professional practices (Rönnerman et al. Citation2008, pp. 269–270, Kennedy, Citation2014, Petrie et al. Citation2020). This in turn presupposes awareness of and emphasis on relatings and social-political arrangements, further agency, trust and recognition, which are crucial aspects underpinning and promoting learning in and for professional practice.

Drawing on these presuppositions, we argue that professional learning for praxis development takes place in and for professional practices, which includes reflection, inquiry, dialogue and collaboration, as recognised and systematically used in action research. Learning in and for professional practice is influenced by agency, trust, recognition, power and solidarity. Human growth through lived experience is also influenced by agency, trust, recognition, power and solidarity. Further, these relational dimensions are binding elements across learning in and for professional practices and fundamental to human growth. Time as a resource and flow is essential as part of site-based practices – the happeningness – and time and flow are also inherent components of human growth.

There are different implications of the development of the framework. When it comes to research it provides means to study professional learning as it happens. The framework also provides conceptual opportunities to describe what happens when educators participate in learning practices. In this way, new knowledge arises, which goes beyond a mere characterisation of professional learning and involves ways of describing and explaining what happens that widen our knowledge of the phenomenon of professional learning for praxis development. Another implication, for policy developers is the possibility to consider different approaches to support teacher learning. The framework leads to research supporting a deeper knowledge of trust-based professionalism (Sahlberg Citation2007, pp. 151–153), which is based on loose standards, flexibility and intelligent accountability, accompanied by professional discretion and autonomy and allowing educators to make professional judgements in their professional practice based on local circumstances. For practice, the implications are parallel: to inform schools and educators about how different kinds of approaches to professional learning will influence their possibilities to learn and act in relation to different kind of goals and missions.

Agency, trust, recognition, power and solidarity are foundational for professional learning for praxis development. The theory of practice architectures holds that social-political arrangements enable and constrain the relatings in a practice. Social-political arrangements are realised in the mediums of power and solidarity. Power over can be a disruptive and negative arrangement, whereas power with, through and to can form a basis for teacher agency. Agency can be understood as the power to act, and agency in professional learning for praxis development is enabled and constrained through the practice architectures in the local site, including trust. Relational trust is an important component of collaborative professional learning for praxis development, involving interpersonal, interactional, intersubjective, intellectual, and pragmatic trust. Relational trust forms a sound basis for teacher agency related to educational knowing and acting. In the ongoing transition between being and becoming, mutual recognition lays the foundation for educators’ self-confidence, self-respect, and self-esteem, which are necessary to become an agent and to be agentic in society. Differences become a source for learning, and mutual recognition enables risk-taking when it comes to transforming practices. Educator praxis and professional learning that enables praxis development provide a foundation for transforming unjust, unsustainable or inequitable practices in education and in society more broadly. This in turn supports the dual purpose of education: to live well in a world worth living in.

Acknowledgement

The authors want to thank the members of the Pedagogy, Education and Praxis -network subgroup in Professional Learning who participated in reflections and discussions on the aspects and perspectives of professional 560 learning and development while preparing this Special Issue.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Aharonian, A., 2021. Making it count: teacher learning in liminal spaces. Professional development in education, 47 (5), 763–779. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1667413.

- Allen, A., 1998. Rethinking power. Hypatia, 13 (1), 21–40. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1998.tb01350.x.

- Bartlett, L., 2004. Expanding teacher work roles: a resource for retention or a recipe for overwork? Journal of education policy, 19 (5), 565–582. doi:10.1080/0268093042000269144.

- Bergson, H., 2001. Time and free will: an essay on the immediate data of consciousness. transl. L. Pogson, originally published in 1913. London: G. Allen.

- Blue, S., 2019. Institutional rhythms: combining practice theory and rhythm analysis to conceptualise processes of institutionalization. Time & society, 28 (3), 922–950. doi:10.1177/0961463X17702165.

- Boylan, M., et al. 2018. Rethinking models of professional learning as tools: a conceptual analysis to inform research and practice. Professional development in education, 44 (1), 120–139. doi:10.1080/19415257.2017.1306789

- Brante, G., 2009. Multitasking and synchronous work: complexities in teacher work. Teaching and teacher education, 25 (3), 430–436. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.015.

- Bryk, A. and Schneider, B., 2002. Trust in schools: a core resource for improvement. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Clarke, D. and Hollingsworth, H., 2002. Elaborating a model of teacher professional growth. Teaching and teacher education, 18 (8), 947–967. doi:10.1016/S0742-051X(02)00053-7.

- Colley, H., Hodginson, P., and Malcolm, J., 2003. Informality and formality in learning. London: Learning and Skills Research Centre.

- Cooper, R., et al., 2020. Understanding teachers’ professional learning needs: what does it mean to teachers and how can it be supported? Teachers & teaching, 27 (7–8), 558–576. doi:10.1080/13540602.2021.1900810.

- Cordingley, P., 2015. The contribution of research to teachers’ professional learning and development. Oxford review of education, 41 (2), 234–252. doi:10.1080/03054985.2015.1020105.

- Day, C., 1999. Developing teachers: the challenges of lifelong learning. London: Routledge Falmer.

- DeLuca, C., et al., 2015. Collaborative inquiry as a professional learning structure for educators: a scoping review. Professional development in education, 41 (4), 640–670. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.933120.

- Desimone, L.M., 2009. Improving impact studies of teachers’ professional development: toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational researcher, 38 (3), 181–199. Available from. Accessed 25th of May, 2023. doi:10.3102/0013189X08331140

- Dunlap, D. and Goldman, P., 1991. Rethinking power in schools. Educational administration quarterly, 27 (1), 5–29. doi:10.1177/0013161X91027001002.

- Edwards-Groves, C., et al., 2018. Driving change from ‘the middle’: iddle leading for site based educational development. School leadership and anagement, 39 (3–4), 315–333. doi:10.1080/13632434.2018.1525700.

- Edwards-Groves, C. and Grootenboer, P., 2021. Conceptualising five dimensions of relational trust: implications for middle leadership. School leadership & management, 41 (3), 260–283. doi:10.1080/13632434.2021.1915761.

- Edwards-Groves, C., Grootenboer, P., and Rönnerman, K., 2016. Facilitating a culture of relational trust in school-based action research: recognising the role of middle leaders. Educational action research, 24 (3), 369–386. doi:10.1080/09650792.2015.1131175.

- Emirbayer, M. and Mische, A., 1998. What is agency? American journal of sociology, 103 (49), 962–1023. doi:10.1086/231294.

- Fennel, H., 1999. Power in the principalship: four women’s experiences. Journal of educational administration, 37 (1), 23–49. doi:10.1108/09578239910253926.

- Francisco, S., Forssten Seiser, A., and Grice, C., 2023. Professional learning that enables the development of critical praxis. Professional development in education, 49 (5), 938–952. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1879228.

- Groundwater-Smith, S., et al., 2013. Facilitating practitioner research. Developing transformational partnerships. London: Routledge.

- Hallinger, P. and Kulophas, D., 2020. The evolving knowledge base on leadership and teacher professional learning: a bibliometric analysis of the literature, 1960–2018. Professional development in education, 46 (4), 521–540. doi:10.1080/19415257.2019.1623287.

- Handal, G. and Lauvås, P., 2000. På egna villkor – en strategi för handledning. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Hardy, I., 2010. Critiquing teacher professional development: teacher learning within the field of teachers’ work. Critical studies in education, 51 (1), 71–84. doi:10.1080/17508480903450232.

- Heikkilä, M., 2022. Methodological insights on teachers’ professional agency in narratives. Professions & professionalism, 12 (3), 1–17. doi:10.7577/pp.5038.

- Hoekstra, A., et al., 2009. Experienced teachers’ informal workplace learning and perceptions of workplace conditions. Journal of workplace learning, 21 (4), 276–298. doi:10.1108/13665620910954193.

- Honneth, A., 1995. The struggle for recognition: the moral grammar of social conflicts. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Kemmis, S., et al. 2012. Ecologies of practices. In: P. Hager, A. Lee, and A. Reich, eds. Practice, learning and change: practice theory perspectives on professional learning. Dordrecht: Springer, 33–50.

- Kemmis, S., et al., 2014. Changing practices, changing education. Singapore: Springer.

- Kemmis, S., 2019. A practice sensibility: invitation to the theory of practice architectures. Singapore: Springer.

- Kemmis, S., 2021. A practice theory perspective on learning: beyond a ‘standard’ view. Studies in continuing education, 43 (3), 280–295. doi:10.1080/0158037X.2021.1920384.

- Kemmis, S., 2022. Transforming practices: changing the world with the theory of practice architectures. Singapore: Springer.

- Kemmis, S. and Edward-Groves, C., 2018. Understanding education: history, politics, and practice. Singapore: Springer.

- Kemmis, S., McTaggart, R., and Nixon, R., 2014. The action research planner. Singapore: Springer.

- Kemmis, S. and Smith, T.J., 2008. Praxis and praxis development. In: S. Kemmis and T.J. Smith, eds. Enabling praxis: challenges for education. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 3–14.

- Kennedy, A., 2005. Models of continuing professional development: a framework for analysis. Journal of In-service education, 31 (2), 235–250. doi:10.1080/13674580500200277.

- Kennedy, A., 2014. Understanding continuing professional development: the need for theory to impact on policy and practice. Professional development in education, 40 (5), 688–697. doi:10.1080/19415257.2014.955122.

- Kyndt, E., et al., 2016. Teachers’ everyday professional development: mapping informal learning activities, antecedents, and learning outcomes. Review of educational research, 86 (4), 1111–1150. doi:10.3102/0034654315627864.

- Lave, J., 2019. Learning and everyday life: access, participation and changing practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Løvlie, L., 1973. Pedagogisk filosofi i vitenskapens tidsalder. In: E. Befring, ed. Pedagogisk periferi – noen sentrale problemer. Oslo: Gyldendal, 99–137.

- Mahon, K., et al. 2017. Introduction: practice theory and the theory of practice architectures. In: K. Mahon, S. Francisco, and S. Kemmis, eds. Exploring education and professional practice: through the lens of practice architectures. Singapore: Springer, 1–30.

- Marsick, V.J. and Watkins, K.E., 1990. Informal and incidental learning in the workplace. London: Routledge.

- Mockler, N., 2013. Teacher professional learning in a neoliberal age: audit, professionalism and identity. Australian journal of teacher education, 38 (10), 35–47. doi:10.14221/ajte.2013v38n10.8.

- Mockler, N., 2022. Teacher professional learning under audit: reconfiguring practice in an age of standards. Professional development in education, 48 (1), 166–180. doi:10.1080/19415257.2020.1720779.

- Muijs, D., et al. 2014. State of the art – teacher effectiveness and professional learning. School effectiveness and school improvement, 25 (2), 231–256. doi:10.1080/09243453.2014.885451

- Noffke, S., 2009. Revisiting the professional, personal, and political dimensions of action research. In: S. Noffke and B. Somekh, eds. The SAGE handbook of educational action research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 5–18.

- Olin, A., et al. 2020. Collaborative professional learning for changing educational practices. In: K. Mahon, C. Edwards-Groves, S. Francisco, M. Kaukko, S. Kemmis, and K. Petrie, eds. Pedagogy education and praxis in critical times. Singapore: Springer, 141–162.

- Olin, A. and Pörn, M., 2021. Teachers’ professional transformation in teacher-researcher collaborative didactic development projects in Sweden and Finland. Educational action research, 31 (4), 821–838. doi:10.1080/09650792.2021.2004904.

- Opfer, D.V. and Pedder, D., 2011. Conceptualizing teacher professional learning. Review of educational research, 81 (3), 376–407. doi:10.3102/0034654311413609.

- Petrie, K., Kemmis, S., and Edwards-Groves, C. 2020. Critical praxis for critical times. In: K. Mahon, ed. Pedagogy, education, and praxis in critical times. Singapore: Springer, 163–178.

- Ping, C., Schellings, G., and Beijaard, D., 2018. Teacher educators’ professional learning: a literature review. Teaching and teacher education, 75, 93–104. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.003

- Postholm, M.B., 2012. Teachers’ professional development: a theoretical review. Educational research, 54 (4), 405–429. doi:10.1080/00131881.2012.734725.

- Priestley, M., Biesta, G., and Robinson, S., 2015. Teacher agency an ecological approach. London: Bloomsbury.

- Reimer, K., et al., 2023. Living well in a world worth living in for all: current practices of social justice, sustainability and wellbeing. Singapore: Springer.

- Rönnerman, K., 2012. Vad är aktionsforskning? In: K. Rönnerman, ed. Aktionsforskning i praktiken – förskola och skola på vetenskaplig grund. Lund: Studentlitteratur, 21–40.

- Rönnerman, K., Salo, P., and Moxnes Furu, E., 2008. Conclusions and challenges: nurturing praxis. In: K. Rönnerman, E. Furu, and P. Salo, eds. Nurturing praxis – action research in partnerships between school and university in a Nordic light. Rotterdam: Sense Publishers, 267–280.

- Sahlberg, P., 2007. Education policies for raising student learning: the Finnish approach. Journal of education policy, 22 (2), 147–171. doi:10.1080/02680930601158919.

- Sancar, R., Atal, D., and Deryakulu, D., 2021. A new framework for teachers’ professional development. Teaching and teacher education, 101, 1–12. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2021.103305

- Schatzki, T.R., 2001. Introduction. In: T. Schatzki, K. Knorr-Cetina, and E. Savigny, eds. The practice turn in contemporary theory. London: Routledge, 10–23.

- Schatzki, T.R., 2009. Timespace and the organization of social life. In: E. Shove, F. Trentmann, and R. Wilk, eds. Time, consumption and everyday life: practice, materiality and culture. Oxford: Berg, 35–48.

- Schatzki, T.R., 2010. The timespace of human activity: on performance, society, and history as indeterminate teleological events. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Smeed, J., et al., 2009. Power over, with and through another look at micropolitics. Leading & managing, 15 (1), 26–41.

- Solomon, N., Boud, D., and Rooney, D., 2006. The in-between: exposing everyday learning at work. International journal of lifelong education, 25 (1), 3–13. doi:10.1080/02601370500309436.

- Stoll, L., et al., 2006. Professional learning communities: a review of the literature. Journal of educational change, 7 (4), 221–258. doi:10.1007/s10833-006-0001-8.

- Strom, K.J., Mills, T., and Abrams, L., 2021. Non-linear perspectives on teacher development: complexity in professional learning and practice. Professional development in education, 47 (2–3), 199–208. doi:10.1080/19415257.2021.1901005.

- Vangrieken, K., et al., 2017. Teacher communities as a context for professional development: a systematic review. Teaching and teacher education, 61, 47–59. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.001.

- Villegas-Reimers, E., 2003. Teacher professional development: an international review of the literature. Paris: International Institute for Educational Planning.

- Webster-Wright, A., 2009. Reframing professional development through understanding authentic professional learning. Review of educational research, 79 (2), 702–739. doi:10.3102/0034654308330970.

- Wenger, E., 1998. Communities of practice: learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E., 2000. Communities of practice and social learning systems. Organization, 7 (2), 225–246. doi:10.1177/135050840072002.

- Zehetmeier, S., et al., 2015. Researching the impact of teacher professional development programmes based on action research, constructivism, and systems theory. Educational action research, 23 (2), 162–177. doi:10.1080/09650792.2014.997261.