ABSTRACT

Gender diverse people experience significantly high levels of mental health difficulties, face significant barriers accessing mental healthcare, and often report negative experiences with mental health professionals. At the same time, healthcare professionals describe feeling deskilled when providing care for gender diverse adults. This paper aims to systematically review research into mental health professionals’ experiences of providing care for gender diverse individuals, and the kind of research methods employed in these investigations. PubMed, SCOPUS, psycARTICLES, and psychINFO were searched, as well citation and reference lists of relevant articles. From 268 search results, 12 articles were deemed relevant to be included in the review. The studies used quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. Each article was evaluated against established quality guidelines. All studies were likely to have been affected by social desirability bias, and had limited exploration of participants’ contexts, or social discourse. The quality of the articles varied. Clinicians reported having minimal training about gender diversity, and they tended to be less competent working with gender diverse clients compared to LGB clients. Participants described uncertainty working with gender diverse clients, and all the studies identified the need for improved training for mental health professionals working with gender diverse adults.

Introduction

Gender diverse people experience significantly high levels of mental health difficulties. The Trans Mental Health Study (McNeil et al., Citation2012; n = 889), reported that 48% of trans people in Britain reported having attempted suicide at least once in their lifetime, and 84% had thought about it. 55% reported being diagnosed with depression at some point in their lives. In addition, the survey reported that 63% had experienced one or more negative interactions in general mental health services. Similarly, in the USA, Reisner et al. (Citation2015) reported that transgender youth, sampled from an urban community health centre, had significantly more mental health difficulties compared to cisgender matched controls.

Gender diverse people may require support from mental health services as a result of questioning their gender (Ellis et al., Citation2015), or the minority stress (Meyer, Citation1995) they may experience as a result of moving through the world as a gender diverse person. Meyer (Citation1995) describes minority stress as conflict with the social environment experienced by minority group members related to the juxtaposition of minority and dominant values. For example, the stress related to presenting as gender diverse in a social environment which values gender normativity. Equally, gender diverse people may require mental healthcare for issues completely unrelated to their gender identity, or as a requirement to be granted gender-affirming care (Ellis et al., Citation2015; Schulz, Citation2018)

People with non-binary identities experience specific challenges which may contribute to their experiences of mental health difficulties. Vincent (Citation2016) describes how discourses in both medical contexts and queer communities often work to delegitimise non-binary identities, and Crissman et al. (Citation2019) suggest that non-binary individuals may experience poorer mental health because of the widespread assumption of gender binaries in healthcare research, provision, and institutions.

Research suggests that there are significant difficulties and barriers faced by trans people attempting to receive adequate trans-related (e.g. prescription of hormones), and non-trans-specific (e.g. primary care) physical healthcare (Kosenko et al., Citation2013; Pearce, Citation2018; Roller et al., Citation2015). Several studies have reported that gender diverse people with other marginalised intersecting identities (e.g. Bowleg, Citation2012) have even poorer experiences of healthcare. For example, in their study of trans people of colour in Chicago, Howard et al. (Citation2019) reported that most of their participants believed they would have more positive experiences of healthcare if they were cisgender or white. Similarly, Shires and Jaffee (Citation2015) reported that ‘female-to-male’ transgender individuals in the USA who were Native American, multiracial or had lower incomes were more likely to experience discrimination in a healthcare setting.

There has been a smaller amount of research into gender diverse people’s experiences of accessing mental health services. Ellis et al. (Citation2015) analysed survey data from 621, trans people about their experiences accessing mental health services in the UK, for reasons other than trans-related care. Around a third of the respondents reported being dissatisfied or very dissatisfied with the care they received. They reported experiences such as their clinician not being educated on trans topics, and their gender identity not being seen as genuine, but seen as a symptom of mental illness. Around a third of respondents reported having worries about accessing mental health services due to their trans history. Many reported worries that any difficulty they present with would be interpreted as due to them being, trans.

Similarly, trans people in Australia have also expressed dissatisfaction with the mental health care they have received. Riggs et al. (Citation2014) analysed survey responses from 188 gender diverse Australians, who were asked about their healthcare experiences with psychiatrists, GPs and surgeons. They found that although some medical professionals provided healthcare to gender diverse clients adequately, others fell short of meeting their clients’ needs. The survey respondents described issues such as misgendering, the need to educate their clinicians, and experiencing discriminatory comments.

Research suggests that previous bad experiences, fear of treatment (e.g. ‘I didn’t know what would happen to me’), and stigma can prevent gender diverse people seeking mental health services when they require them (e.g. Shipherd et al., Citation2010). In her study, Pearce (Citation2018) describes the mistrust gender diverse people might have towards mental health providers, such as fearing that disclosure of mental health difficulties may negatively impact on their access to physical interventions. However, one person in Pearce’s study was quoted saying that blanket statements about mental health professionals being untrustworthy could also be harmful. Although gender diverse people commonly have difficult experiences with mental health professionals, some also have positive and supportive experiences. For example, Sallans (Citation2016), a transgender man, described an experience with a therapist who was nonjudgmental, open, humble, and a good source of support during his transition. In addition, all the transgender participants in Benson’s (Citation2013) study expressed a belief that mental health services can be helpful if the clinicians are informed about transgender issues.

The research highlights potential inadequacies in the interactions between healthcare providers and gender diverse people. Despite this, there is limited research exploring clinicians’ experiences of supporting gender diverse individuals. Snelgrove et al. (Citation2012) and Poteat et al. (Citation2013) both interviewed clinicians (e.g. physicians, nurses, endocrinologists) to explore the barriers and stigma transgender patients in North America face when accessing healthcare services. All but one of the clinicians interviewed in these studies were physical healthcare providers. Clinicians in these studies spoke of feeling deskilled, and one participant was quoted as ‘not knowing where to go or who to talk to’ (Snelgrove et al., Citation2012, p. 4).

A handful of studies have investigated the attitudes of mental health professionals towards gender diverse people. Kanamori and Cornelius-White (Citation2017) reported that counsellors in the USA tended to have positive attitudes towards transgender clients, and Riggs and Sion (Citation2017) reported that cisgender male psychologists and psychology trainees in Australia expressed more negative attitudes towards transgender people than cisgender females. Ali et al. (Citation2016) reported that psychiatrists and psychiatry residents in Canada expressed less negative attitudes towards transgender people than those expressed by the general population. However, these studies do not provide any information about clinicians’ experiences or actions when providing mental healthcare, and are highly subject to social desirability bias: participants may give socially desirable responses instead of choosing responses that are reflective of their true feelings (Grimm, Citation2010).

This paper will systematically review research into mental health professionals’ experiences of providing care for gender diverse individuals, and the kind of research methods employed in these investigations. A quality assessment and critique of the current literature will be included.

Methodology

The systematic review of literature followed PRISMA guidelines as recommended by Moher et al. (Citation2009). The review was conducted by the first author, who sought consultation around language, theory, technique, and synthesis from the second and third authors. The authors are confident that no other systematic review has been published on mental health professionals’ experiences of providing care for gender diverse individuals.

Search strategy

A systematic literature review was conducted, aiming to answer the research question ‘How do mental health professionals describe their experiences of providing care for gender diverse clients? presents the terms used to search for literature in this area. The terms were separated into two concepts, Concept 1 relating to Mental Health Professionals, and Concept 2 relating to Gender diversity. The ‘AND’ function was used to combine search results for these two concepts.

Table 1. Search terms.

The Mental Health Professionals concept was searched for within the title of research papers only, to ensure that Mental Health Professionals were the subject of the research. When searching for this concept within the abstract or keywords, many thousands of articles were found where mental health service users were the subject of the research. The Gender Diversity concept was searched for in the title, abstract, and keywords of research articles in order to capture any reference to working with gender diverse people.

These search terms were used to search PubMed, SCOPUS, psycARTICLES, and psychINFO. The search terms ‘mental health nurse*’, counsellor, ‘gender dysphoria’ and ‘gender identity disorder’ were added after initial searches using PubMed, and reviewing relevant papers. The search term ‘gender identity’ was removed as it generated many irrelevant papers about gender differences between therapists. The search term psychotherapist* was added after further searches using SCOPUS. No further limitations were made to the searches regarding earliest date of publication.

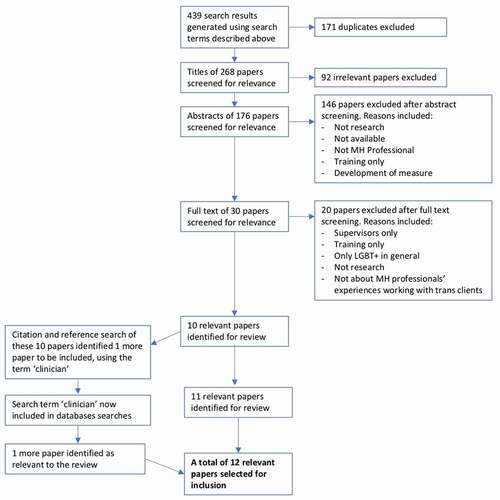

On 3 November 2019, the search demonstrated in generated 17 results in PubMed, 143 results in SCOPUS, 15 results in psycARTICLES, and 264 results in psycINFO. Altogether this totalled 439 search results. After excluding duplicates (171), 268 results remained. The titles of these 268 papers were screened for relevance. Irrelevant papers were screened outFootnote1 if the papers focused on: children or young people only (64); physical health or physical interventions only (7); sexuality rather than gender (17); studied career counsellors (2); or the papers were not about gender diverse individuals at all (4). Papers were included at this stage if they referred to Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) individuals in general. 92 papers were excluded after the titles were screened, leaving 176 papers for further screening.

The abstracts of these 176 papers were then screened for relevance. Again, papers were screened out for the exclusion reasons outlined above (49). Papers were also excluded at this stage if they were: a book, chapter, commentary or review which did not include primary research (66); were not available in English (8); focused on training only (6); did not study mental health professionals (4); were not about professionals’ experiences of providing mental health care (3); a specific clinical example (1); a paper about differential diagnosis (1); doctoral dissertations unavailable to read (7); or related to the development of a self-report measure (1). Following the screening of abstracts, 146 papers were excluded, with 30 papers remaining to be examined further.

The full text of these 30 papers were read and screened for relevance. Papers were excluded from the systematic review if the research was: with supervisors rather than clinicians (1); about LGBT people in general, without specific findings related to gender diverse peopleFootnote2 (7); focused on staff training (1); a commentary (1); not about mental health care (1); a specific clinical example (1); or not about professionals’ experiences working with gender diverse clients (2). Six papers were excluded which only measured mental health professionals’ self-reported attitudes towards gender diverse individuals, without reporting any other experiences, or actions related to their work.

Following this final screening, 20 papers were excluded, leaving 10 relevant papers to be reviewed. After an extensive citation and reference search of these 10 papers, one additional paper was found to be relevant to the review. This paper used the word ‘clinician’ to refer to mental health professionals, which had previously not been included in the searches. One more search was conducted in each of the databases using the word ‘clinician’ and the Gender Diversity concept, which identified one more paper relevant to the review. Therefore, the total number of papers included in the review was 12. See for a flowchart demonstrating the process described above.

Synthesis strategy

The papers selected were organised into three groups, determined by their methodology. The findings for each group were initially synthesised separately, and the quality of the methodologies used by the studies in each group were evaluated. The similarities and differences between the findings from different studies were explored. The findings across all the groups were then drawn together, and the research evidence as a whole was critiqued. This process maps on to processes of Narrative Synthesis for studies with heterogenous methodologies, described by Ryan (Citation2013).

Findings

summarises the 12 papers selected for inclusion in the systematic review. The 12 journal articles can be separated into three groups, those which used quantitative methods (e.g. novel and standardised self-report measures), those which used qualitative methods (e.g. semi-structured interviews, reflective journals), and those which used mixed methods (e.g. surveys with both open and closed questions). Each journal article was subject to a quality check, following the criteria outlined by Elliott et al. (Citation1999). The outcomes of these quality checks can be found in Appendix A. These quality guidelines were selected because the authors pull together criteria for both quantitative and qualitative research, both of which are necessary for the articles included in the present systematic review.

Table 2. Article summaries.

Group 1: quantitative research articles

Four of the research articles reviewed used only quantitative methods to research mental health professionals’ work with gender diverse adults (Dispenza & O’Hara, Citation2016; Johnson & Federman, Citation2014; Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). All four studies involved mental health professionals completing questionnaires (either online or paper), which generated scores related to their self-reported attitudes, comfort and confidence working with gender diverse clients, as well as their clinical knowledge, assessed by the researchers. These scores were considered measures of the clinicians’ ‘competence’.

Riggs and Bartholomaeus (Citation2016a; n = 304) and Dispenza and O’Hara (Citation2016, n = 102) both sampled from a range of mental health professionals (e.g. counsellors, social workers). Whereas Riggs and Bartholomaeus (Citation2016b; n = 96) surveyed mental health nurses specifically, and Johnson and Federman (Citation2014) surveyed 384 American Clinical Psychologists who provided psychological therapy to LGBT veterans. All the articles in this group were deemed good quality according to the guidelines shared by both quantitative and qualitative research (Appendix A).

Overall, these four studies reported that more ‘competent’ clinicians appeared to be those that were generally more experienced (Dispenza & O’Hara, Citation2016), and those that were specifically more experienced working with gender diverse clients (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). Clinicians reported having minimal training in the area (Johnson & Federman, Citation2014; Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016b), however more training was linked to greater ‘competency’ (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016b). Younger psychologists, sexual, ethnic and racial minorities, older nurses, and female clinicians seemed to be more competent (Dispenza & O’Hara, Citation2016; Johnson & Federman, Citation2014; Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016a, Citation2016b), whereas psychiatrists, and those who reported themselves more religious, tended to be less ‘competent’ working with gender diverse clients (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016a, Citation2016b). All authors in this group suggest that mental health professionals would benefit from further training to support gender diverse clients.

All four studies are strengthened by their relatively large sample sizes, however the majority of the samples were mostly white, female, and cisgender. All the participants in Dispenza and O’Hara (Citation2016) study had attended a multicultural counselling conference, therefore were likely to have particular values or experiences which may not be generalisable to all mental health professionals. The study by Johnson and Federman (Citation2014) provides a useful snapshot of clinicians’ attitudes, knowledge, practice and self-reported competence working with LGBT veterans at a particular point in American history, shortly after the ‘Don’t ask don’t tell’ bill was repealed. However, clinicians’ attitudes, competences and experiences related to working with transgender clients may have changed since this time, as the Trump administration banned transgender individuals from serving in the military from 2019. The research mostly focused on attitudes and experiences working with LGB clients, rather than gender diverse clients, and no information was gathered regarding the participants’ ethnicity.

All four studies in this group measured participants’ attitudes towards gender diverse clients. Although research demonstrates the potential harm caused by clinicians who hold negative attitudes towards gender diverse clients (e.g. Nadal, Skolnik & Wong, Citation2012), the strength of the association between attitudes and behaviour is complex, and can be influenced by other factors such as context and time (e.g. Ajzen & Fishbein, Citation1977).

Johnson and Federman (Citation2014) and Dispenza and O’Hara (Citation2016) included measures of clinicians’ self-reported competency, however the validity of these measurements is likely to be affected by social desirability, and the clinicians’ desire to be seen as competent. They may also perceive themselves as more competent than gender diverse clients might perceive them to be. However, all four studies also assessed the participants’ clinical knowledge, which may be a more objective measurement of the clinicians’ ‘competency’, as the participants would not be able to achieve high scores unless they had an understanding of best practice. Riggs and Bartholomaeus (Citation2016a) was the only study to include separate measurements of clinician ‘Comfort’ and ‘Confidence’ working with gender diverse clients, which add a useful subjective dimension to their findings.

All the described quantitative measures of competence, knowledge, attitudes and skills related to working with gender diverse clients are limited. The questionnaires make assumptions about the knowledge and skills required to support gender diverse clients, and rate the responses against these criteria. In addition, they treat gender diverse people as a homogenous group, not capturing the nuanced and diverse experiences of gender diverse people who might be seeking mental health support. Although the findings provide a snapshot of competency across a large sample of clinicians, the quantitative results lack richness and detail about how clinicians feel about their work with gender diverse clients, their confidence in different aspects of their work, and what contexts enable them to work more or less effectively with this group of clients.

Group 2: qualitative research articles

Four studies in the systematic review used qualitative research methods to better understand mental health professionals’ work with gender diverse clients. Israel et al. (Citation2008) gathered data from 14 psychotherapists working with LGBT clients in general, Salpietro et al. (Citation2019; n = 12) and Lutz (Citation2013; n = 6) interviewed counsellors/therapists about their work with transgender clients specifically, and Rutter et al. (Citation2010) analysed the reflective journal entries of two student counsellors who worked with one gender diverse couple. See for the qualitative analysis used in each study.

Rutter et al. (Citation2010) identified themes around the trainees not knowing where to go next in therapy, and all four studies identified the need for improving training programmes for working with gender diverse clients. Three studies mentioned the importance of generic therapeutic skills, such as therapeutic alliance and advocacy, when working with gender diverse clients (Israel et al., Citation2008; Lutz, Citation2013; Salpietro et al., Citation2019). Two studies also mentioned skills specific to working with gender diverse clients, such as the therapist’s response to the client’s gender, or hesitancy around discussing issues of sexual intimacy in a gender diverse couple (Israel et al., Citation2008; Rutter et al., Citation2010). The participants in Salpietro et al.’s study spoke of the ‘essential knowledge’ needed to work with gender diverse clients, such as awareness of gender concepts and transitioning. Lutz (Citation2013) and Salpietro et al. (Citation2019) describe how this knowledge often came from clinicians’ personal experiences, or through keeping themselves informed, rather than formal training. Participants in Israel et al.’s (Citation2008) study described therapy as less helpful for LGBT clients with more marginalised or discriminated identities, such as those with transgender identities, LGBT people of colour, or those with limited access to resources.

According to the guidelines suggested by Elliott et al. (Citation1999), the research conducted by Salpietro et al. (Citation2019) was of the highest quality: the authors clearly outlined their own theoretical orientations and assumptions, described several credibility checks, and presented their findings coherently and with resonance. Their particular qualitative methodology required researchers to ‘bracket’ off their assumptions. Although the authors describe measures they took in order to do this, it could be argued that in qualitative analysis, their assumptions can never be removed entirely. Israel et al.’s (Citation2008) study was assessed as good quality: the sample was well situated, and the authors described some credibility checks. However, the researchers did not state any of their own assumptions, did not provide any direct quotes from the interviews, and the themes were difficult for the reader to synthesise, due to them being presented in long lists with percentages. In addition, the research focused mostly on LGB issues, with limited findings about work with gender diverse clients.

Rutter et al.’s (Citation2010) study was assessed as poor against the guidelines especially pertinent to qualitative research. The paper did well to situate the sample, and described some credibility checks. However, the researchers’ assumptions and orientations were not stated, did not include any direct quotes, and only one theme was well discussed. At times, the authors could have been more respectful towards the trainees regarding their competence. Lutz’s (Citation2013) study was also assessed as poor quality. Lutz aimed to assess the therapists’ competency in supporting gender diverse individuals. The research does this with more nuance and richness than the quantitative research above. However, the qualitative analysis is limited in depth and quality, reading more like survey results than a phenomenological analysis. Lutz also provided no demographic information about the participants.

Rutter et al. (Citation2010) described a useful and detailed analysis of the work and reflections of two co-therapists working with a queer couple, rather than reporting general themes identified within a group of people. However, the findings were specific to the two white, heterosexual, cisgender trainee counsellors. Similarly, the majority of Salpietro et al.’s (Citation2019) participants were female, white and cisgender. A strength of the research by Israel et al. (Citation2008) is that the sample was relatively diverse, in terms of the gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, location, education, and fields of practice of the therapists. However, all four studies collected data from counsellors or therapists, excluding any other kind of mental health professional. They also included limited discussion about the social and historical contexts the mental health professionals find themselves in.

Group 3: mixed methods research articles

The final four research articles included in this systematic review used a combination of quantitative and qualitative methods to research mental health professionals’ work with gender diverse clients. Whitman and Han (Citation2017) surveyed 53 mental health professionals (e.g. psychiatrists, counsellors) about their work with gender diverse clients, and O’Hara et al. (Citation2013) surveyed 87 trainee counsellors who provided counselling for gender diverse clients. Kawano et al. (Citation2018) surveyed 361 dance/movement therapists about their work with LGBT clients, and Dentato et al. (Citation2018) surveyed social work students and alumni of a drug and alcohol counselling module, as well as providers of this service, about working with LGBT clients (n = 63).

Similar to the quantitative studies above, all four studies in this group used questionnaire measures to investigate professionals’ attitudes and actions (Kawano et al., Citation2018), ‘competence’ (Dentato et al., Citation2018; O’Hara et al., Citation2013; Whitman & Han, Citation2017), and ‘preparedness’ (Dentato et al., Citation2018; O’Hara et al., Citation2013) for working with LGBT or gender diverse clients. Two studies included qualitative elements to the questionnaires which were also analysed (Kawano et al., Citation2018; Whitman & Han, Citation2017). One study conducted two focus groups (O’Hara et al., Citation2013; n = 7), and another study conducted interviews (Dentato et al., Citation2018; n = 3) alongside the questionnaire. See for the qualitative analysis used in each study.

Altogether, studies in the mixed methods group reported that those with more personal and professional contact with gender diverse individuals were more competent at working with this group of clients (O’Hara et al., Citation2013). Whitman and Han (Citation2017) also reported that trainee clinicians were significantly more competent than licenced clinicians. The clinicians interviewed in O’Hara et al.’s (Citation2013) and Dentato et al.’s (Citation2018) studies mentioned difficulties with terminology, knowledge presented through the media, uncertainties around how to work with gender diverse clients, and the limitations of their own training course to prepare them for this work. Whitman and Han identified themes in participants’ problematic responses such as targeting a client’s gender identity as an intervention for therapy, or imposing a religious/spiritual orientation onto a person’s formulation. All authors made suggestions for improving current training programmes for working with gender diverse clients.

Both Dentato et al. (Citation2018) and Kawano et al. (Citation2018) investigated competencies and preparedness for working with LGBT clients in general, and reported a specific gap in clinicians’ competencies working with gender diverse clients compared to LGB clients. Although Kawano et al. reported that therapists generally described affirmative practices, with good intentions, and half of Dentato et al.’s (Citation2018) participants considered themselves competent to work with gender diverse clients, Whitman and Han (Citation2017) reported disparities between clinicians’ self-rated competence, and researcher-assessed competence working with gender diverse clients, thus questioning the validity of clinicians’ self-reports in the other studies.

The mixed methods approach used by the studies in this group allows for broad, rich and triangulated data. All four studies used the qualitative data to add depth to their quantitative findings and were assessed as good quality against the guidelines shared by both qualitative and quantitative approaches (Elliott et al., Citation1999). However, it is perhaps expected that qualitative research in a mixed methods approach would not be of such high quality as in qualitative-only research. All but one of the studies (O’Hara et al., Citation2013) in this group were assessed to be of poor quality against the guidelines especially pertinent for qualitative research, as the majority of studies did not state their assumptions, did not describe any credibility checks, and had limited resonance. The studies in this group also tended to lack the depth of the quantitative-only and qualitative-only studies, often only presenting descriptive statistics or simple correlations in the quantitative sections, and limited thematic analysis in the qualitative sections.

Kawano et al.’s (Citation2018) study was heavily dependent on therapists’ self-reported attitudes and actions when working with LGBT clients, therefore the results may have been more affected by social desirability. Whitman and Han (Citation2017) attempted to overcome this issue in their study by using a social desirability questionnaire, and a multi-dimensional assessment of competency, which included a ‘knowledge assessment’ and clinical vignettes. Participants’ responses were rated by independent observers. The multi-dimensional approach to investigate clinician competency greatly improved the validity of this research.

The samples in all four studies were predominantly white, female, and heterosexual. Kawano et al. (Citation2018) sampled from a wide geographical area, whereas O’Hara et al. (Citation2013) and Dentato et al. (Citation2018) only sampled from a single university or training course, respectively, limiting their generalisability to other contexts. However, Dentato et al.’s (Citation2018) focus on one training programme allowed the researchers to identify strengths and limitations of a concrete example of training, make real-life changes as a result of the research, and make suggestions on how other training programme might follow suit. Finally, Kawano et al. (Citation2018) and Dentato et al. (Citation2018) mostly reported findings related to working with LGB clients, only minimally describing clinicians’ experiences with gender diverse people specifically.

Discussion

The studies in this review reported that clinicians with more training and experience with gender diverse clients were more competent working with this group, although most participants reported minimal training in the area. Younger psychologists, trainees, sexual, ethnic and racial minorities, older nurses, and female clinicians tended to be more competent, whereas psychiatrists, and those who reported themselves as more religious, tended to be less competent. The studies which investigated LGBT people in general reported that clinicians seemed to be less competent in working with gender diverse clients compared to LGB clients.

All the studies identified the need for improved training for mental health professionals working with gender diverse clients. Participants described their uncertainty working with gender diverse clients, and the importance of generic therapeutic skills such as therapeutic alliance and advocacy when working with this group. Some studies mentioned specific skills and knowledge required for working with gender diverse clients such as the therapist’s response to the client’s gender identity, and awareness of gender concepts. Other studies reported some of the stigmatising beliefs or practices described by clinicians such as imposing religious or moral views onto a client’s formulation, or seeing their gender identity as a target for intervention in therapy.

Two of the research articles included in this review were conducted in Australia (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016a, Citation2016b), and the rest were conducted in the USA. The specific healthcare systems, social and historical contexts of these two countries makes it difficult to draw conclusions about mental health professionals working in other countries.

Several of the studies across the groups described how it is likely that their sample over-represented people who might have more experience or interest in working with gender diverse clients, as those are the people who would be more likely to volunteer to take part in the research (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, Citation2016a). The studies may be missing the responses and experiences of clinicians who feel less comfortable working with gender diverse clients, or have more stigmatising views.

Many of the studies also reported samples which were majority cisgender, female, heterosexual, and white, potentially excluding the experiences of mental health professionals outside of this demographic. However, this is perhaps expected and representative, given the demographics of the mental health workforce in Australia and the USA. The majority of psychologists and mental health nurses in Australia are female (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2017). In the USA, the majority of psychologists are female (American Psychological Association, Citation2015) and white (Lin et al., Citation2018), as well as the majority of counsellors (Data USA, Citation2017) and mental health social workers (Data USA, Citation2018). At the time of writing, information about the sexual and gender diversity of the mental health workforce in these countries could not be found, nor could information about the ethnic diversity of mental health professionals in Australia, perhaps indicating a lack of institutional interest. It is also important to note that participants may not feel comfortable disclosing their sexual or gender diversity in research studies, or national surveys.

In their study, Salpietro et al. (Citation2019) describe a theme related to the societal challenges and inadequacies of healthcare for gender diverse clients, and O’Hara et al. (Citation2013) briefly mention representations of, trans identities in the media. However, other than these two examples, the studies in this review are limited in their discussions of the contexts in which healthcare providers find themselves, and the role of discourse in shaping their views, experiences and work.

The majority of the studies sampled groups of therapists or counsellors. One study researched mental health nurses, and another a group of social workers, whereas only three studies included a range of mental health professionals in their samples. Although it is important for research to investigate the specific challenges related to working with gender diverse clients in each discipline, the professions do not work in isolation. Mental health professionals often work in multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs), in a range of different contexts (e.g. inpatient, community). Therefore, a sample which attempts to capture this diversity may paint a richer picture than a homogenous group from a single profession.

This review included the few LGBT papers which reported specific findings about mental health professionals’ work with gender diverse clients. The majority of papers with this broader focus were excluded from the review as they only reported findings related to LGB clients, or LGBT clients in general. However, even the LGBT papers included in this review mostly reported findings related to clinicians’ work with lesbian and gay clients. This reflects a historical gap in the literature related to work with transgender (and bisexual) clients (Israel et al., Citation2008). Of the 12 studies included in this review, 7 of them focused on mental health professionals’ work with gender diverse clients specifically, and 5 focused on work with LGBT clients in general. The trans-specific papers make up the majority of the papers from 2014, however between 2008 and 2014, the majority of papers investigated clinicians’ work with LGBT clients in general. The recent increase in research articles focusing specifically on mental health professionals’ work with gender diverse clients coincides with the general increase and visibility of gender diverse identities in recent years (Barker, Citation2017; Steinmetz, Citation2014).

Although some studies attempted to overcome limitations of social desirability (e.g. Dispenza & O’Hara, Citation2016; Whitman & Han, Citation2017), all the findings in this review were to some extent influenced by how the participants wished to be perceived. It is important to note the operations of power which may be enacted in the research studies, and the potential feared outcomes for the participants if they were to disclose discriminatory views or practices to the researchers. This is likely to be an issue for all research which asks mental health professionals about their practice.

Further research could contribute to the literature by studying the experiences of mental health professional outside the USA and Australia, and continuing to investigate their experiences working with gender diverse individuals specifically, as opposed to LGBT individuals in general. Research could also pay more attention to the contexts mental health professionals work in, and the social discourses which shape their experiences. Finally, as gender diverse young people also experience higher rates of mental health difficulties compared to their cisgender counterparts (e.g. Newcomb et al., Citation2020), a corresponding systematic review of mental health professionals’ experiences providing mental healthcare to gender diverse youth would be a useful contribution to the literature.

In conclusion, 12 research articles were identified which investigated mental health professionals’ experiences working with gender diverse clients. These articles used a range of quantitative, qualitative and mixed methods approaches. The clinicians reported having minimal training about gender diversity, and younger psychologists, trainees, sexual, ethnic and racial minorities, older nurses, and female clinicians tended to be more competent. Clinicians tended to be less competent working with gender diverse clients compared to LGB clients. Participants described uncertainty working with gender diverse clients, the importance of generic therapeutic skills, as well as specific knowledge required for working with gender diverse clients. All the studies identified the need for improved training for mental health professionals working with gender diverse clients. The studies may over-represent the views of professionals who have more experience or interest in working with gender diverse clients, and the majority of participants were white, female and heterosexual. All studies were also likely to have been affected by social desirability bias, and had limited exploration of participants’ contexts, or social discourse.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Lauren Canvin

Lauren Canvin is a Clinical Psychologist, having completed doctoral training at the University of Hertfordshire, specialising in gender identity.

Jos Twist

Jos Twist is a specialist Clinical Psychologist in gender identity for children, young people, adults and their families.

Wendy Solomons

Wendy Solomons is a Clinical Psychologist, and the Academic Lead on the Doctoral Programme in Clinical Psychology at the University of Hertfordshire.

Notes

1. Some papers were screened out for more than one reason.

2. Research which sampled LGBT people in general were only included in the review if they reported findings specific to working with gender diverse clients.

References

- Ajzen, I., & Fishbein, M. (1977). Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin, 84(5), 888–918.

- Ali, N., Fleisher, W., & Erickson, J. (2016). Psychiatrists’ and psychiatry residents’ attitudes toward transgender people. Academic Psychiatry, 40(2), 268–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-015-0308-y

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Demographics of the U.S. psychology workforce: Findings from the American community survey. [PDF]. https://www.apa.org/workforce/publications/13-demographics/report.pdf

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2017). Mental health workforce. [PDF]. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/30b7f40d-fc89-42da-b5c4-43647e7aa940/Mental-Health-Workforce-2017.pdf.aspx

- Barker, M. J. (2017, December 27). 2017 review: The transgender moral panic. Rewriting the rules. https://www.rewriting-the-rules.com/gender/2017-review-transgender-moral-panic/

- Benson, K. E. (2013). Seeking support: Transgender client experiences with mental health services. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 25(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952833.2013.755081

- Bidell, M. P. (2005). The sexual orientation counselor competency scale: Assessing attitudes, skills, and knowledge, of counselors working with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Counselor Education and Supervision, 44(4), 267–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2005.tb01755.x

- Bowleg, L. (2012). The problem with the phrase women and minorities: Intersectionality—an important theoretical framework for public health. American Journal of Public Health, 102(7), 1267–1273. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750

- Crissman, H. P., Stroumsa, D., Kobernik, E. K., & Berger, M. B. (2019). Gender and frequent mental distress: Comparing transgender and non-transgender individuals’ self-rated mental health. Journal of Women’s Health, 28(2), 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7411

- DataUSA. (2017). Counsellors. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/counselors#demographics

- DataUSA. (2018). Mental health and substance abuse social workers. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/mental-health-and-substance-abuse-social-workers#demographics

- Dentato, M. P., Kelly, B. L., Lloyd, M. R., & Busch, N. (2018). Preparing social workers for practice with LGBT populations affected by substance use: Perceptions from students, alumni, and service providers. Social Work Education, 37(3), 294–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2017.1406467

- Dispenza, F., & O’Hara, C. (2016). Correlates of transgender and gender nonconforming counseling competencies among psychologists and mental health practitioners. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 156. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000151

- Elliott, R., Fischer, C. T., & Rennie, D. L. (1999). Evolving guidelines for publication of qualitative research studies in psychology and related fields. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 38(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466599162782

- Ellis, S. J., Bailey, L., & McNeil, J. (2015). Trans people’s experiences of mental health and gender identity services: A UK study. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 19(1), 4–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2014.960990

- Emerson, R., Fretz, R., & Shaw, L. (1995). Writing ethnographic fieldnotes. The University of Chicago Press.

- Grimm, P. (2010). Social desirability bias. In J. N. Sheth & N. K. Malhotra (Eds.), Wiley International Encyclopedia of Marketing. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Howard, S. D., Lee, K. L., Nathan, A. G., Wenger, H. C., Chin, M. H., & Cook, S. C. (2019). Healthcare experiences of transgender people of color. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 34(10), 2068–2074. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05179-0

- Israel, T., Gorcheva, R., Walther, W. A., Sulzner, J. M., & Cohen, J. (2008). Therapists’ helpful and unhelpful situations with LGBT clients: An exploratory study. Professional Psychology, Research and Practice, 39(3), 361. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.39.3.361

- Johnson, L., & Federman, E. J. (2014). Training, experience, and attitudes of VA psychologists regarding LGBT issues: Relation to practice and competence. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 1(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000019

- Kanamori, Y., & Cornelius-White, J. H. (2017). Counselors’ and counseling students’ attitudes toward transgender persons. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 11(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2017.1273163

- Kawano, T., Cruz, R. F., & Tan, X. (2018). Dance/movement therapists’ attitudes and actions regarding LGBTQI and gender nonconforming communities. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 40(2), 202–223. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10465-018-9283-7

- Kosenko, K., Rintamaki, L., Raney, S., & Maness, K. (2013). Transgender patient perceptions of stigma in health care contexts. Medical Care, 51(9), 819–822. https://doi.org/10.1097/MLR.0b013e31829fa90d

- Lin, L., Stamm, K., & Christidis, P. (2018, February). How diverse is the psychology workforce? News from APA’s center for workforce studies. Monitor on Psychology, 49(2), 19. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2018/02/datapoint

- Lutz, J. C. (2013). Assessing clinical competency among clinicians who work with transgender clients. Doctoral dissertation, The Chicago School of Professional Psychology.

- McNeil, J., Bailey, L., Ellis, S., Morton, J., & Regan, M. (2012). Trans mental health study [PDF]. Scottish Trans Alliance. https://www.scottishtrans.org/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/trans_mh_study.pdf

- Meyer, I. H. (1995). Minority stress and mental health in gay men. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36(1), 38–56. https://doi.org/10.2307/2137286

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Nadal, K. L., Skolnik, A., & Wong, Y. (2012). Interpersonal and systemic microaggressions toward transgender people: Implications for counseling. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 6, 55–82.

- Newcomb, M. E., Hill, R., Buehler, K., Ryan, D. T., Whitton, S. W., & Mustanski, B. (2020). High burden of mental health problems, substance use, violence, and related psychosocial factors in transgender, non-binary, and gender diverse youth and young adults. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 49(2), 645–659. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-019-01533-9

- O’Hara, C., Dispenza, F., Brack, G., & Blood, R. A. (2013). The preparedness of counselors in training to work with transgender clients: A mixed methods investigation. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 7(3), 236–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2013.812929

- Pearce, R. (2018). Understanding trans health: Discourse, power and possibility. Policy Press.

- Poteat, T., German, D., & Kerrigan, D. (2013). Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Social Science & Medicine, 84, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.02.019

- Rehbein, R. N. (2012). Transition in conceptualizing the transgender experience: A measure of counselor attitudes. (Unpublished master’s thesis). Eastern Illinois University

- Reisner, S. L., Vetters, R., Leclerc, M., Zaslow, S., Wolfrum, S., Shumer, D., & Mimiaga, M. J. (2015). Mental health of transgender youth in care at an adolescent urban community health center: A matched retrospective cohort study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 56(3), 274–279. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.10.264

- Riggs, D. W., & Bartholomaeus, C. (2016a). Australian mental health professionals’ competencies for working with, trans clients: A comparative study. Psychology & Sexuality, 7(3), 225–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/19419899.2016.1189452

- Riggs, D. W., & Bartholomaeus, C. (2016b). Australian mental health nurses and transgender clients: Attitudes and knowledge. Journal of Research in Nursing, 21(3), 212–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987115624483

- Riggs, D. W., Coleman, K., & Due, C. (2014). Healthcare experiences of gender diverse Australians: A mixed-methods, self-report survey. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 230–236. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-230

- Riggs, D. W., & Sion, R. (2017). Gender differences in cisgender psychologists’ and trainees’ attitudes toward transgender people. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 18(2), 187–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000047

- Roller, C. G., Sedlak, C., & Draucker, C. B. (2015). Navigating the system: How transgender individuals engage in health care services. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 47(5), 417–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnu.12160

- Rutter, P. A., Leech, N. N., Anderson, M., & Saunders, D. (2010). Couples counseling for a transgender-lesbian couple: Student counselors’ comfort and discomfort with sexuality counseling topics. Journal of GLBT Family Studies, 6(1), 68–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/15504280903472816

- Ryan, R. (2013). Cochrane consumers communication review group: Data synthesis and analysis. Cochrane Consumers Communication Review Group. https://cccrg.cochrane.org/sites/cccrg.cochrane.org/files/public/uploads/AnalysisRestyled.pdf

- Sallans, R. K. (2016). Lessons from a transgender patient for health care professionals. AMA Journal of Ethics, 18(11), 1139–1146. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2016.18.11.mnar1-1611

- Salpietro, L., Ausloos, C., & Clark, M. (2019). Cisgender professional counselors’ experiences with trans* clients. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 13(3), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2019.1627975

- Schulz, S. L. (2018). The informed consent model of transgender care: An alternative to the diagnosis of gender dysphoria. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 58(1), 72–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167817745217

- Shipherd, J. C., Green, K. E., & Abramovitz, S. (2010). Transgender clients: Identifying and minimizing barriers to mental health treatment. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 14(2), 94–108. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359701003622875

- Shires, D. A., & Jaffee, K. (2015). Factors associated with health care discrimination experiences among a national sample of female-to-male transgender individuals. Health & Social Work, 40(2), 134–141. https://doi.org/10.1093/hsw/hlv025

- Snelgrove, J. W., Jasudavisius, A. M., Rowe, B. W., Head, E. M., & Bauer, G. R. (2012). “Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: A qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC Health Services Research, 12(1), 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-12-110

- Steinmetz, K. (2014). The transgender tipping point. Time Magazine, 183(22), 38–46. https://time.com/135480/transgender-tipping-point/

- Sue, D., & Sue, D. (2008). Counseling the Culturally Diverse Theory and Practice (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Vincent, B. W. (2016). Non-binary gender identity negotiations: Interactions with queer communities and medical practice. PhD thesis, University of Leeds.

- Walch, S. E., Ngamake, S. T., Francisco, J., Stitt, R. L., & Shingler, K. A. (2012). The attitudes toward transgendered individuals scale: Psychometric properties. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 41(5), 1283–1291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-012-9995-6

- Whitman, C. N., & Han, H. (2017). Clinician competencies: Strengths and limitations for work with transgender and gender non-conforming (TGNC) clients. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(2), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1080/15532739.2016.1249818

Appendix A.

Quality Checks for Articles Reviewed

Guidelines Shared by Both Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches

Guidelines Especially Pertinent to Qualitative Research