ABSTRACT

Social entrepreneurs develop important innovative solutions for complex societal challenges. This exploratory article provides a typology of different approaches by which social entrepreneurs develop such innovations. This typology is based on their engagement in anticipation, reflexivity, stakeholder inclusion and deliberation, responsiveness and knowledge management, during the development of their innovation. Following from quantitative analyses of data from self-assessment questionnaires and subsequent contextualization, the findings reveal four distinctive ways to successfully develop innovative solutions for societal problems. This article therefore contributes to our understanding of the innovation process by which social entrepreneurs develop social innovations.

Introduction

Societies all over the world are facing major societal challenges, such as climate change, socio-economic inequalities or ageing populations. Social entrepreneurs take it on themselves to develop innovative solutions for such societal challenges (Dees Citation2007), in particular those that governments, for-profit and non-profit organizations fail to address (properly) (Sud, VanSandt, and Baugous Citation2009). This problem-solving role in society is recognized by governments, who therefore stimulate social entrepreneurship and innovation, especially in times of general retrenchment (Mueller et al. Citation2015; Shaw and de Bruin Citation2013). Supporting organizations such as Ashoka and the Skoll foundation have also created platforms for social entrepreneurship to stimulate their problem-solving role in society. Moreover, the academic community has studied this phenomenon with increasing interest, with the result that the current state of social entrepreneurship research has progressed beyond infancy into a mature stage (Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2016).

Even though social entrepreneurship research has matured, there are still many gaps in our knowledge. Previous research focused predominantly on defining, conceptualizing, and describing the phenomenon of social entrepreneurship (Granados et al. Citation2011; Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2016; Zahra et al. Citation2009). However, even though social entrepreneurs are characterized as innovative individuals (Zahra et al. Citation2009), the actual innovation process is still an understudied theme in social entrepreneurship (Chalmers and Balan-Vnuk Citation2013). Exploring how social entrepreneurs manage to develop their innovations is therefore expected to advance the field (Doherty, Haugh, and Lyon Citation2014; Phillips et al. Citation2015). For example, empirical research by Waddock and Steckler (Citation2016) revealed that only half of the social entrepreneurs engage in action guided by a clear vision, which conflicts with the image of social entrepreneurs as visionary change agents. Furthermore, the development of innovation in social enterprises is likely to take place in multi-stakeholder environments that may support or inhibit the success of the innovation (Newth and Woods Citation2014), even though social entrepreneurs are frequently portrayed as heroic lone entrepreneurs (Dufays and Huybrechts Citation2014). On the one hand, stakeholders may support the innovation process as they can provide new knowledge and insights (Kong Citation2010) and ultimately legitimacy for the innovation (Newth and Woods Citation2014); on the other hand, they may also have different, sometimes opposing, values and opinions regarding the innovation (Cho Citation2006) and thus be a source of resistance (Newth and Woods Citation2014). It is therefore vital for social enterprises to be open to their external environment to develop successful innovations, while at the same time making sure that the development process is controlled and efficient, and facilitates better decision-making (Kong Citation2010). Exploring how social entrepreneurs develop their innovations in multi-stakeholder environment will therefore be a welcome contribution to social entrepreneurship research.

Following on from the knowledge gaps stipulated above, the aim of this article is to answer the following research question: what are the different approaches adopted by social entrepreneurs to translate their initial ideas into innovative solutions that (help to) address societal problems? Hence, this article focuses on the process of developing social innovations in the context of social entrepreneurship. The concept of responsible innovation is used in this article as a theoretical lens with which to analyze the process of how successfully social entrepreneurs translate their initial ideas for innovation into final innovation outcomes. The main idea behind responsible innovation is that one can steer innovations in desirable directions by engaging in anticipatory governance of innovation based on deliberative forms of stakeholder engagement (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017; Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). Hence, the framework of responsible innovation consists of several dimensions that make it particularly suitable to study the innovation process in social enterprises. First and foremost, stakeholder engagement and stakeholder deliberation are central in the framework of responsible innovation (Blok, Hoffmans, and Wubben Citation2015). Social entrepreneurship is also a political phenomenon, and entrepreneurs need to understand the values that are at play in their work that need to be aligned with the social objectives. Delineating these social ends requires public participation and deliberation (Cho Citation2006). Responsible innovation provides a framework to explore the multi-stakeholder environment in which social entrepreneurs develop their innovative solutions. Second, it covers the role of anticipation in the development of innovations and can therefore build upon the work of Waddock and Steckler (Citation2016). Third, it also draws attention to firm-internal processes such as reflexivity of the organization (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013) and knowledge management of information flows inside and outside the company (Lubberink et al. Citation2017b), which are vital for successful social innovations in social enterprises (Kong Citation2010). Ultimately, it is about being responsive to the new insights, knowledge and (changing) stakeholder needs and values, which may require an adjustment of the innovation (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013).

The social entrepreneurs in this article are elected Ashoka fellows who developed and implemented innovative solutions for problems that have a profound impact on society (Ashoka Citation2011) and can be regarded as well-established and successful social entrepreneurs (Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas Citation2012). The mixed methodology used in this study combines quantitative and qualitative approaches. The findings depend predominantly on the quantitative research, whereas subsequent contextualization required qualitative content analyses. The quantitative approach is based on a self-assessment of responsible governance of innovation provided by 42 Ashoka social entrepreneurs. The qualitative approach involves analyses of the profile descriptions of each of these 42 social entrepreneurs, which serves to contextualize the results obtained from the quantitative self-assessment. In this article, four typologies are proposed; this will help to unpack the heterogeneity found in social entrepreneurship, and is a common procedure in the research field (e.g. Chandra and Shang Citation2017; Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas Citation2012; Waddock and Steckler Citation2016; Zahra et al. Citation2009).

This article contributes to the literature on social entrepreneurship as it provides typologies of innovation processes in which different dimensions of managing the innovation process may be more or less present and in different combinations, thereby being responsive to the expected heterogeneity of the phenomenon. The use of responsible innovation as a framework for investigating innovation processes sheds light on a wide array of different dimensions that are vital for innovation in social enterprises. The context of social entrepreneurship is complex and diverse, and has a profound impact on the enactment thereof (De Bruin and Lewis Citation2015). Consequently, ‘a breakthrough would then allow incorporation of contextual variables or even contextualisation of empirical social entrepreneurship research in a second step’ (Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2016, 10). The current article aims to achieve this by complementing the quantitative analyses of questionnaire data about the innovation process with qualitative data from the profile descriptions.

This paper begins with an overview of the concept of social entrepreneurship and its sub-concept social innovation. This is complemented with the theoretical dimensions of the concept of responsible innovation and why it is a relevant lens through which to assess how social entrepreneurs develop their innovative solutions for societal problems. It will then go on to the materials and methods used to identify the different approaches for translating initial ideas for innovation into final innovation outcomes. The results section presents the findings of the research, focusing on the different typologies of innovation processes that are identified. The paper concludes with the implications of these different approaches to innovation for the field of social entrepreneurship, and compares its findings with insights from previous empirical investigations of social entrepreneurship.

Theoretical framework

Social entrepreneurship and innovation

Previous social entrepreneurship research revolved primarily around its definition and conceptualization (Granados et al. Citation2011; Kraus et al. Citation2014; Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2016). However, even though there is no consensus yet about the definition of social entrepreneurship (Choi and Majumdar Citation2014), a definition should logically draw upon entrepreneurial processes that require opportunity exploitation and resource (re)combination processes (Newth and Woods Citation2014). The following definition of social entrepreneurship by Peredo and McLean (Citation2006) is therefore deemed suitable as a working definition of social entrepreneurship:

Social entrepreneurship is exercised where some person or group: (1) aim(s) at creating social value, either exclusively or at least in some prominent way; (2) show(s) a capacity to recognize and take advantage of opportunities to create that value (“envision”); (3) employ(s) innovation, ranging from outright invention to adapting someone else's novelty, in creating and/or distributing social value; (4) is/are willing to accept an above-average degree of risk in creating and disseminating social value; and (5) is/are unusually resourceful in being relatively undaunted by scarce assets in pursuing their social venture (Citation2006, 64).

Social entrepreneurship research has predominantly focused on more general studies that describe or define social entrepreneurship (Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2016). However, in-depth investigations should also take place regarding the sub-concepts of social entrepreneurship (Choi and Majumdar Citation2014). Several articles have been published in which parts of the social entrepreneurship phenomenon are investigated in more detail, but which also include a description of the apparent heterogeneity within these sub-parts. For example, Chandra and Shang (Citation2017) explored how combinations of social skills and the social position may have enabled the founders to pursue their social entrepreneurship career. Hence, they focused on the social entrepreneur and more specifically the biographical antecedents that enable them to combine dual identities. Likewise, the empirical study by Waddock and Steckler (Citation2016) describes three types of social entrepreneurs when exploring how vision, intention and action relate to each other. Visionaries indeed have a clear vision that guides their entrepreneurial action. However, inadvertent wayfinders start to act and often cannot really formulate a clear vision, while for the emergent wayfinders the vision only crystallizes after they have made sense of their actions. Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas (Citation2012) explored how social entrepreneurs are able to create social change to resolve societal problems. Their empirical study identified four different types of social change-making processes that relied on the creation and leveraging of either political, social, economic or human capital. In other words, they investigated the social innovation outcomes and the associated social change, but did not focus on the process by which these social innovations emerged from initial ideas. And, finally, Zahra et al. (Citation2009) conceptualized three types of social entrepreneurs by building on different notions of entrepreneurship, which come from the works of, respectively, Hayek, Kirzner and Schumpeter. The typologies differ, for example, in their search processes, the impact on the social system and resource (re)combination processes. Social bricoleurs discover and respond to local and small-scale social needs. Social constructionists discover and exploit opportunities to respond to underserved clients to subsequently introduce innovations to broader social systems; they mend the social fabric where it is torn, whereas social engineers discover systemic problems that require revolutionary change; they overthrow dated systems to replace them with novel better ones. To conclude, different attempts have been made to do justice to the heterogeneity that can be found in the social entrepreneurship process and its related sub-concepts (e.g. the person, entrepreneurial vision and innovation outcomes).

This article focuses on one of the sub-concepts in social entrepreneurship, namely their innovations that (help to) solve a societal problem or pressing social need. While social entrepreneurs are described as innovative individuals, they do not always develop novel solutions for societal problems. For example, a social entrepreneur could start a work integration social enterprise and be innovative in marketing the products that it aims to sell. Yet, it does not mean that the solution for a societal problem is based on a novel idea or approach. This article focuses on the innovation processes of social entrepreneurs who have turned novel ideas into innovative solutions that (help to) solve societal problems or pressing social needs. Such innovations are often, but not always, accompanied by necessary social change and are therefore also called social innovations. The concept of social innovation is discussed in the following section.

Social innovation

There have been discussions about the definition and conceptualization of social innovation (e.g. Bacq and Janssen Citation2011; Huybrechts and Nicholls Citation2012). This was primarily due to two different dominant views as to what social innovation entails, which focused either on social relations or social impact. Recently, there has been a de-contestation of social innovation with the convergence of these two approaches to social innovation (Ayob, Teasdale, and Fagan Citation2016). This convergence is evident in the definition provided by Murray, Caulier-Grice, and Mulgan (Citation2010) who define social innovations as

innovations that are social both in their ends and in their means. Specifically, we define social innovations as new ideas (products, services and models) that simultaneously meet social needs and create new social relationships or collaborations. In other words, they are innovations that are both good for society and enhance society's capacity to act (3).

Phillips et al. (Citation2015) reviewed the literature to identify the linkages between social innovation and social entrepreneurship. Social innovation and social entrepreneurship both aim to pursue a social objective or mission, and involve a problem-solving opportunity to meet a social need. However, social innovation also implies that the innovation is accompanied by changes in the social system. While this may indeed be the case for some social entrepreneurs (e.g. social engineers), it is not necessarily true of all social entrepreneurs. Furthermore, social innovation is not confined to social entrepreneurship; for-profit or non-profit enterprises as well as governmental organizations can also develop and implement innovative ideas that create change for the benefit of society. And even though social innovation and social entrepreneurship are both about pursuing a social objective, their processes are portrayed differently in the literature. Social entrepreneurship research often depicts the lone visionary who aims to create social change, whereas the focus on social innovation is on the collective and dynamic interplay of actors who together aim to create social change (Phillips et al. Citation2015).

The social innovation outcomes can manifest as products, production processes, technologies, services, interventions, business models or a combination of all of these, thereby differing in the extent of formalization (Choi and Majumdar Citation2015). However, the innovative solution may also induce or require social change processes, especially in cases where social entrepreneurs need to challenge the social systems that created the problems they address. In those cases, social entrepreneurs turn into institutional entrepreneurs and act as change agents in society (Westley et al. Citation2014). This understanding resonates with the social constructionists who aim to mend social fabrics, or social engineers who introduce effective new social systems to replace former systems that are ill-equipped to address social needs (Zahra et al. Citation2009). Hence, social entrepreneurship can be advanced by looking into the concept of social innovation, while doing justice to the collective nature of social innovation processes (Phillips et al. Citation2015).

Studying the innovation processes in social entrepreneurship is thus expected to benefit from stakeholder, relational and network perspectives (Shaw and de Bruin Citation2013; Smith, Gonin, and Besharov Citation2013). Social innovations are implicitly and explicitly formed by the expectations and demands of stakeholders, which makes it essential to have a thorough understanding of the social issue at hand and how the innovation can be developed (Newth and Woods Citation2014). However, this can be challenging in social systems where stakeholders have different (sometimes conflicting) expectations, beliefs and logics (Smith, Gonin, and Besharov Citation2013). The stakeholders who are needed to provide legitimacy for the innovation can therefore also be a source of resistance (Newth and Woods Citation2014). Social entrepreneurs are aware of this and may use different rhetorical strategies to persuade stakeholders of the legitimacy of their organization and their innovative ideas (Ruebottom Citation2013). However, one could question whether such innovations are ‘social’ since they are not the result of a public political process. In fact, it is then merely the entrepreneur's conception of ‘the good’ that he/she aims to pursue (Cho Citation2006). Social enterprises must therefore not only develop innovations whose implications are aligned with the social mission of the firm, but also take into account the different, sometimes opposing, views of their stakeholders.

This article aims to explore how social entrepreneurs advance from their initial ideas for innovation to the final innovative solutions, while managing their stakeholder network and their own social mission. It thereby responds to Phillips et al. (Citation2015) to include the collective nature of social innovation when studying the development of innovations in social entrepreneurship. The framework of responsible innovation serves as a research lens through which to explore the development of innovations by social entrepreneurs, and is therefore elaborated upon in the next section.

Responsible innovation

Responsible innovation is a new and emerging concept developed by researchers and policy-makers with the aim of stimulating anticipatory governance of innovation based on deliberative forms of stakeholder engagement. It considers the development of innovations as a political process as the implications of the innovation may have a profound impact on the public. The development of responsible innovations is therefore only considered as ‘responsible’ when the innovation process is based on public participation and deliberation (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013), which is not necessarily the case in social innovation (Lubberink et al. Citation2017a)Footnote1 or social entrepreneurship (Cho Citation2006).

Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) developed an influential framework consisting of four dimensions that can be used heuristically to accomplish responsible governance of innovation. These four dimensions are anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion and responsiveness. This is an influential framework within the field of responsible innovation as these dimensions recur throughout the works of scholars researching responsible innovation (Burget, Bardone, and Pedaste Citation2017). However, the framework by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) is based on discussions that primarily took place among scientists regarding ‘good science’ and ‘good technology’. This resulted in findings focusing primarily on responsible research and technological development. The applicability of the current concept of responsible innovation in the business context is therefore questionable (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015). For example, including stakeholders at the start and deliberating with them about the innovation is at odds with the notion that innovations are based on information asymmetries in the market that are recognized by the entrepreneur. Sharing information with stakeholders to deliberate about the innovation can therefore challenge the entrepreneur's source of competitive advantage (Blok and Lemmens Citation2015).

In response to the issues raised, Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b) reviewed empirical evidence from social, sustainable and responsible innovation practices and processes in the business context to give practical substance to the framework proposed by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013). This resulted in an adjusted framework for responsible innovation that can be used for further operationalization and assessment of responsible innovation in the business context. Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b) proposed that inclusion and deliberation are two distinctive dimensions of responsible innovation, and further identified knowledge management as an additional dimension of responsible innovation in the business context. Based on the framework by Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten (Citation2013) and complemented by the findings by Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b), the following dimensions are used as a lens for understanding the development of innovation in social enterprises.

Anticipation revolves around opening up innovation to multiple views that help to foresee any ‘known, likely, plausible and possible implications of the innovation that is to be developed’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1570). Foresight-enhancing activities do not focus on predicting futures, instead it aims to increase resilience and adaptivity. Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b) suggest innovators to engage in multiple activities to better understand the innovation context and the needs of the stakeholder environment, which can subsequently be translated in a plan for development. Furthermore, innovations in general, and systems-changing innovations in particular, can benefit from generating multiple scenarios how the development of innovations could lead to its successful implementation (Lubberink et al. Citation2017b). Reflexivity is about critically scrutinizing one's own ‘activities, commitments and assumptions, and being aware of the limits of knowledge and the fact that [one's reality] may not be universally held’ (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013, 1571). Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b) argue that reflexivity revolves around role of the firm itself in developing the innovation. Reflexive innovators reflect on whether their innovation leads to the desired innovation outcome, and whether the decision-making is in line with their norms, values and beliefs. Furthermore, having a diverse group of employees who share their views on the development of the innovation is an indicator of enhanced reflexivity (Lubberink et al. Citation2017b). In addition, innovators need to blur the lines between their role responsibility and their wider moral responsibilities (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). However, social entrepreneurs are by nature aware of their moral responsibilities as they have a normative orientation that focuses on their social role in addition to being an economic agent (Moss et al. Citation2011). Inclusion is the actual involvement of stakeholders and the wider public with dialogue or other attempts that can help to steer an innovation in the desired direction. The stakeholder network is ideally composed of stakeholders who can provide the necessary resources (i.e. organizational and know-how), respect each other's roles and are committed throughout the process of developing the innovation (Lubberink et al. Citation2017b). Deliberation is about the openness and quality of the discussion. It involves an exchange of views and opinions among stakeholders and between stakeholders and the social entrepreneur(s). Ideally, deliberation facilitates awareness and reconciliation of different stakeholder interests. Providing relevant information to form an opinion, and being open about how decisions are made fosters deliberation, and hence decision-making. Sometimes, stakeholders have actual decision-making power when it comes to the steering of the innovation process and desired outcomes (Lubberink et al. Citation2017b). Responsiveness is about acting on the insights obtained when engaging in the aforementioned dimensions, which implies having the capacity to develop the innovation in response to the values of stakeholders, the wider public and changing circumstances (Stilgoe, Owen, and Macnaghten Citation2013). Furthermore, it is about actually adjusting courses of action and responding to new knowledge, perspectives, views and norms that emerge during innovation. This article looked at actual responsive behaviour (i.e. the actual changes in the innovation process, innovation outcome, required adaptation of the stakeholders) or the capacity to adjust if it were deemed necessary. Consequently, knowledge management is a dimension that Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b) added to the framework. Derived from knowledge-based dynamic capabilities (Denford Citation2013), it covers actions to overcome practical knowledge gaps that can arise with innovation: for instance, creating knowledge within the firm, creating knowledge with other external actors, or obtaining knowledge from external sources, and subsequently integrating it into the innovation process (Lubberink et al. Citation2017b).

The framework of responsible innovation is expected to shed light on how social entrepreneurs develop their innovative solutions for societal problems. For example, the dimension of anticipation may shed light on the role of foresight and strategic planning, which Weerawardena and Mort (Citation2006) regard as vital, while Waddock and Steckler (Citation2016) showed that this may differ between social entrepreneurs; whereas stakeholder inclusion and stakeholder deliberation will provide insights into the collective nature of innovation in social entrepreneurship, an area still understudied in its field (Phillips et al. Citation2015).

Because the dimensions and key activities developed by Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b) are developed based on empirical studies in the business context and can serve as the basis for further operationalization, they are most suitable to be used as input for the self-assessment questionnaire on responsible innovation in the business context. Therefore, this article assesses the implementation of anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, deliberation, responsiveness and knowledge management to develop innovative solutions for societal problems by social entrepreneurs.

Materials and methods

This research aims to explore different typologies of innovation processes by social entrepreneurs. Using quantitative research methods, it was possible to identify the different approaches adopted by social enterprises to develop innovative solutions for societal problems. Subsequent qualitative content analyses took place to contextualize the different approaches, resulting in a mixed-methodological design. The quantitative research methods are based on data obtained from questionnaires sent to Ashoka fellows who founded their social ventures in the United States, Canada and Europe.Footnote2

Ashoka fellows are visionaries who develop innovative solutions that fundamentally change how society operates. They find what is not working and address the problem by changing the system, spreading the solution, and persuading entire societies to take new leaps (Ashoka Citation2011, 11).

All information that Ashoka generates during this selection process is comprised into a profile description of each of their fellows, the latter are publicly available on their website (www.ashoka.org). These profile descriptions contain extensive information about the problem addressed, the new innovative solution(s), the strategy for how the innovation will solve the problem, and his/her biographical information. Consequently, these profile descriptions have previously been used for social entrepreneurship research (Chandra and Shang Citation2017; Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas Citation2012; Meyskens et al. Citation2010). However, these studies focused in this respective order on biographical antecedents, social change processes, and resource (re)combinations in the entrepreneurship process. This article required information that was not available on the profile description since it focuses on the innovation process. This information was obtained with self-assessment questionnaires. The profile descriptions therefore provide complementary data, which is used to contextualize the findings from quantitative analyses.

The quantitative research is based on questionnaires that are sent to social entrepreneurs (n ≈ 270).Footnote3 The questionnaire covers all dimensions of the innovation process as proposed by Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b). Each dimension is measured by several items, i.e. questions or statements, which can be answered using a 7-point Likert scale. These items are inspired by the key activities and strategies proposed for each dimension in the refined framework by Lubberink et al. (Citation2017b). The questionnaire was refined based on feedback from scientists with expertise in responsible innovation and entrepreneurship and social entrepreneurs, followed by a final version based on feedback from a methodologist whose expertise lies in questionnaire development. The questionnaire measures the extent to which social entrepreneurs engage in responsible innovation dimensions during the innovation process. Additional questions were added to measure contextual factors that could not be obtained from the Ashoka profile descriptions. The complete questionnaire can be found in Appendix 1.

This article investigated social entrepreneurs who were elected as Ashoka fellows in 2010 or more recently. This was taken as a cut-off date to reduce the recall bias of respondents, as the ability to accurately remember previous events diminishes with time. Additionally, it was decided to ask questions about facts and behaviours rather than beliefs or intentions (Golden Citation1992). The fellows were invited to complete the questionnaire by email, and received reminders by email and follow-up phone calls with the request to fill in the questionnaire. The quantitative data were obtained between April and July 2016.

The clustering method was based on the average scores for all six responsible innovation dimensionsFootnote4 collectively. The quantitative data analysis involved an average-linkage hierarchical cluster analysis, as it takes into account the cluster structure and is a relatively robust hierarchical clustering method (Everitt et al. Citation2011b). This method also yielded clusters that were significantly distinctive from each other either on the average implementation of all dimensions, or they had significantly higher or lower scores for one or more dimensions of the responsible innovation framework. The hierarchical clustering method that was employed in this article did not create equal-sized clusters, as opposed to Ward's method. This also fits with the purpose of this article to explore different types of innovation processes, which may not take place in comparable cluster sizes. The optimum number of clusters was derived by interpreting the dendogram and the proposed clusters. Since this is inherently a matter of subjectivity, Everitt et al. (Citation2011a) suggest complementing this with statistical techniques, as in stopping rules that help to determine the optimum number of clusters present in the data. Milligan and Cooper (Citation1985) conducted a simulated experiment and found that the pseudo-F index (Calinski and Harabasz Citation1974) and the Je(2)/Je(1) index (Duda and Hart Citation1973) are the most effective stopping rules. Stata, the software for statistical analyses, was used to run these two stopping rules.Footnote5

There were 42 participants who completed the questionnaire, which represents a response rate of 15.5%. However, one respondent had too many missing values to be included in further analyses. Two respondents were assigned to their own individual cluster, independent of the number of clusters chosen. Since their scores on the responsible innovation dimensions were unique, the decision was made to exclude them from further analysis. This resulted in 39 respondents for the final cluster solution.

The qualitative study involves content analyses of profile descriptionsFootnote6 (obtained from the Ashoka website) of the 39 social entrepreneurs who completed the questionnaire. The results served to contextualize the findings obtained after quantitative analyses of the questionnaire data. All social phenomena take place in specific contexts that influence particular forms of behaviour (Zahra, Wright, and Abdelgawad Citation2014). Contextualization aims to map out the micro-processes and contingencies that affect the social phenomenon under study, for example the development and implementation of innovations (Garud, Gehman, and Giuliani Citation2014; Shaw and de Bruin Citation2013). Furthermore, contextualization helps to describe phenomena in detail, to generate multiple explanations for the phenomenon and to clarify relationships between contextual factors and the phenomenon under study (Rousseau and Fried Citation2001). The contextual factors that are integrated in this study come from Mair, Battilana, and Cardenas (Citation2012). Based on profile descriptions of Ashoka fellows and entrepreneurs of the Schwab foundation, they inductively developed coding schemes to categorize the problem addressed, the target constituencies, the actions taken and the justification for the solution. Their focus on the problem addressed and the solution proposed is complementary to the focus of this article, which is the process dimension of developing innovations. Since their coding schemes are thoroughly tested, they are therefore used for deductive coding of the profile descriptions of the respondents in this article.

Control variables

There were four control variables that could not be obtained from the profile descriptions. These were therefore integrated in the questionnaire. First, previous entrepreneurial experience is added as a control variable because Baron and Ensley (Citation2006) found that experienced entrepreneurs generate business ideas that are clearer and more focused on financial viability than novice entrepreneurs who focus on the uniqueness of their ideas and follow gut feeling. Second, the need for economic return so that the innovation can be(come) self-sustaining is added as a control variable because Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair (Citation2014) found different governance challenges regarding mission drift and accountability. These differences were observed between social enterprises that depend on the economic value generated by their social innovations versus social enterprises that support their social innovations with other innovations in their portfolio. The third control variable follows a similar line of thought, as the percentage of firm revenues that come from direct sales of their services or products is also controlled for. Organizations reporting that less than 5% of their revenues come from direct sales are not expected to adopt market logic in their decision-making (Lepoutre et al. Citation2011). The need for social innovations to generate demand affects the design of the innovation (Newth and Woods Citation2014). Fourth, the level of experienced uncertainty of the innovator regarding the future implications of their innovation is added as a control variable because matters of responsibility are more problematic and ambiguous for innovators who are more uncertain about the future implications of current actions (Pandza and Ellwood Citation2013).

Results

Descriptive results

provides an overview of the summary statistics for the variables of this study. The Cronbach's alphas are acceptable when they are above 0.7 for narrow constructs and between 0.55 and 0.7 for moderately broad constructs (Van de Ven and Ferry Citation1980). The alpha coefficients of anticipation, inclusion and deliberation exceed 0.70. Therefore, these scales are sufficiently reliable for data analysis purposes. The scales for reflexivity, responsiveness and knowledge management range between 0.58 and 0.61 and are acceptable for moderately broad constructs.Footnote7 Knowledge management and reflexivity are measured by only three items which can explain their lower Cronbach's α. The lower Cronbach's α for responsiveness can be explained by the fact that it is measured by quite diverse items. The scores of each cluster on the individual items that measure each construct of responsible innovation can be found in the Online Supplementary File. displays the intercorrelations among the variables of this study. The correlations between the variables used in this study range between 0.02 and 0.593. Based on the correlations, it can be assumed that multicollinearity is not a problem in the database used for this study.

Table 1. Summary statistics for the research variables.

The cluster analysis was based on the researchers’ interpretation of the dendogram and cluster typologies. The latter involves looking at whether the clusters differ significantly with regard to the average scores on all clusters, or one or more of the average scores on the dimensions. The results of the cluster analysis of the six responsible innovation dimensions suggested that the five-cluster solution best fits the data. This was complemented with two stopping rules in Stata; the Calinski–Harabasz pseudo-F index confirmed the number of clusters while the Duda–Hart index was inconclusive.

There is one cluster that consists of only two respondents, who provided extremely low scores for all responsible innovation dimensions. One respondent stated that the questions were less applicable to her case since the work was more instinctive and unplanned, especially in the beginning. This cluster is omitted from the results due to the small sample size (n = 2) and the uniquely low scores, which allows a more detailed description of the typologies of the remaining four clusters. Based on an exploratory quantitative analysis of significant differences between the clusters, it was possible to identify and describe the variables that discriminate the respective typology from one or more of the other typologies.

Cluster results

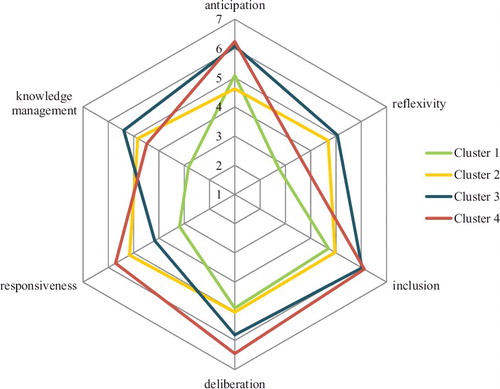

The overall mean scores on the dimensions of responsible innovation (see ), as well as the scores of the four clusters on the six dimensions (), show that anticipation, inclusion and deliberation are the most implemented dimensions of responsible innovation. This means that the social entrepreneurs in general engaged in anticipatory governance of innovation and employed deliberative forms of stakeholder engagement during the development of their innovation. Furthermore, a recurring subject in the profile descriptions is the sense of social entrepreneurs ‘making a difference’ in the world, which resulted in their entrepreneurial action. Often these social entrepreneurs had formative experiences during their childhood (e.g. family life, schooling or religion) or earlier professional life, which gave rise to this attitude. This observation supports the findings by Waddock and Steckler (Citation2016) after interviewing 23 social entrepreneurs about the pathways to their visions.

Table 2. The median scores of each cluster on the six dimensions of responsible innovation, and non-parametric tests for significant differences between the cluster scores.

However, there are also important differences that can be observed between the clusters. The results indicate that cluster one primarily engages in anticipation, inclusion and deliberation, while scoring relatively low on reflexivity, responsiveness and knowledge management. Cluster two scores relatively well on all dimensions of responsible innovation. Cluster three scores exceptionally well on anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion and knowledge management, but scores relatively low on responsiveness. Cluster four scores exceptionally well on anticipation, inclusion, deliberation and responsiveness, but relatively low on reflexivity. These differences between the clusters are tested with non-parametric tests (). The scores for each cluster are also graphically represented in .

Figure 1. Radar chart representing the average scores of the four clusters on each of the six dimensions of responsible innovation.

The differences between the clusters were controlled by percentage of income derived from the innovation, percentage of income from direct sales, certainty about the future implications of the innovation, and previous entrepreneurial experience. Separate univariate ANOVAs revealed that there are no significant differences in percentage of total income derived from the innovation between the clusters, F(3,27) = 0.333, p > 0.05. Also, separate univariate ANOVAs revealed that there are no significant differences in percentage of total income derived from direct sales between the clusters, F(3,28) = 0.856, p > 0.05. Furthermore, a Chi-square test was executed based on the dummy variable [operating without market thinking (direct sales < 5%) or with market thinking (direct sales > 5%)], and this test also confirmed that there was no significant association between cluster membership and the presence or absence of market thinking, χ2(3) = 2.085, p > 0.05. The Fisher's exact test confirms this result. Separate univariate ANOVAs revealed that there are no significant differences between the clusters regarding the level of certainty about the innovation's implications at the start of the innovation process, F(3,33) = 0.531, p > 0.05. The Chi-square test revealed that there was no significant association between cluster membership and the number of previous companies founded, χ2(6) = 6.355, p > 0.05. The Fisher's exact test confirms this result. Therefore, the identified cluster differences cannot be explained by any of the control variables.

Each of the four different cluster typologies is described individually in the remainder of the results section. These descriptions are based on the results from quantitative exploratory analysis, and include insights not only at the level of the dimensions but also at the level of the individual items measuring the dimensions. Furthermore, descriptions of the typologies aim to characterize the respective cluster of social enterprises compared to the others in the sample. The scores on each of these underlying items are graphically represented for each individual dimension, and can be found in the Online Supplementary Material.

The rushing social innovators

The social entrepreneurs in this innovation typology can be considered as the ‘rushing’ innovators. Their innovations ensue from anticipation as the development of their innovation is guided by a plan for development and they think of sufficient scenarios to implement the innovation. Yet, it is rare for these social entrepreneurs to take a reflexive stance while developing their innovation. They rarely assess whether the development of the innovation still leads to the desired innovation outcome, or whether the decision-making is still in line with their own norms, values and beliefs. In the cases of Ruvo, Jaar and Frehe, this can be explained by the fact that they were forced to work on a solution for a societal problem that they experienced themselves, before they were social entrepreneurs. Since their solution turned out to be effective in their particular case, they developed it into an innovation that can easily be scaled. The fact that they acted upon their idea of how to solve their own problem, and it was effective in their situation, could explain why they were less engaged in reflexivity during innovation.

The rushing entrepreneurs have relatively few contacts with stakeholders who will provide them with insights and/or opinions regarding the innovation in its developmental phase. The stakeholders who shared their insights most frequently were customers and suppliers, the people/community affected, and sometimes experts or consultants. Their stakeholder network only functions to a limited extent. Furthermore, their innovation process is less transparent than that of the other entrepreneurs. Stakeholders can only partly see how decisions are made and how they influence the development of the innovation. There are relatively few activities that encourage stakeholder dialogue, and the dialogues that do take place only partly help to address different stakeholder interests.

In the end, the innovation processes and outcomes do not differ from the initial idea of the social entrepreneurs. Furthermore, they had relatively the least capabilities in place to make adjustments, were it necessary. There are also relatively few activities to address the knowledge gaps regarding the process, outcome or impact of the innovation in this cluster. An overview of the characteristics of the ‘rushing’ social entrepreneurs and their enterprises, and a description of their innovations, can be found in . in Appendix 2 is a graphical representation of their scores on every dimension of responsible innovation compared to the mean scores of the other three typologies.

Table 3. Overview of the social entrepreneurs considered as ‘rushing’ entrepreneurs.

The wayfinding social innovators

The second typology of innovation management is based on social entrepreneurs who can be considered ‘wayfinding’ and perform relatively well on all dimensions. However, they are less engaged in following a clear plan to develop their innovation, nor do they think of sufficient scenarios for implementing the innovation, especially in contrast to the visionary entrepreneurs in the sample. Even though they are not visionary social entrepreneurs, they do take a reflexive stance during the development of their social innovation. They are most frequently assessing whether the decision-making is in line with their norms, values and beliefs. Furthermore, they often have people with different personal and professional backgrounds who share their perspectives on how to develop the innovation. Furthermore, there are quarterly evaluations on whether their innovation activities are leading to the desired innovation.

Like other social entrepreneurs, they most often engage with the community/people affected and customers/suppliers. Furthermore, NGOs and other (social) entrepreneurs share their insights and opinions regarding the innovation. However, the social entrepreneurs in this cluster are less satisfied regarding the overall functioning of the stakeholder network. The involved stakeholders lack the right expertise and know-how to contribute to the innovation. Furthermore, the stakeholders do not have the right organizational skills to contribute to the innovation, and have difficulty respecting each stakeholder's role in the development of the innovation. The stakeholders were also not involved throughout the whole process. In other words, the entrepreneurs develop their innovation in a resource-poor environment, and find it difficult to manage the stakeholders.

The stakeholders of these social entrepreneurs have relatively little decision-making power concerning the development of the innovation, and they cannot really see how decisions are made during innovation. However, the social entrepreneurs do make sure that stakeholders have all the information necessary to form an opinion about the innovation. And they organize sufficient activities to encourage dialogues between stakeholders to help address different stakeholder interests. Wayfinding entrepreneurs thus appear to be open to stakeholders, but like to stay in control of the innovation process.

The ‘wayfinding’ entrepreneurs are exceptionally responsive, because they end up with a vastly different innovation process from what they initially foresee. However, they are not the only responsive actors, as their stakeholder environment also needs to adjust to allow implementation of the innovation. When it comes to knowledge management, they are primarily looking to internalize knowledge from beyond their walls and they mainly develop knowledge together with external stakeholders. An overview of the characteristics of the ‘wayfinding’ social entrepreneurs and their enterprises, and a description of their innovations, can be found in . The radar chart in in Appendix 2 is a graphical representation of their scores on every dimension of responsible innovation compared to the mean scores of the other three typologies.

Table 4. Overview of the social entrepreneurs considered as ‘wayfinding’ entrepreneurs.

The ‘rigid visionary’ social innovators

The typology of social entrepreneurs that can be considered ‘rigid visionary’ is composed of social enterprises that engage in all dimensions of responsible innovation except for responsiveness. They can be considered as visionary entrepreneurs as they are highly engaged in anticipation. Illustrative cases involve social entrepreneurs who have actually experienced the neglected societal problem or pressing social need themselves or they have a family member or a friend who is confronted with inadequate social services. This type of social entrepreneur follows a plan for development and thinks of sufficient scenarios to implement the innovation. For example, Erit saw citizens abroad initiating activities to raise money for civil society organizations (CSOs). Inspired by this, they developed a social innovation to stimulate citizens in their homeland to start similar initiatives, as they knew that CSOs were struggling to make an impact. Another example is Kolo, who has designed her social innovation based on an already accepted principle in the health care context:

inspired by the concept of a storage container or pillbox used to facilitate medicine dosages […] his/her vision [is] a new type of “dosing” becomes commonplace […] [where] the “dosage boxes” for elderly patients can be filled with activities, not just drugs or medicine.

The rigid visionary social entrepreneurs are highly reflexive, as people with different professional backgrounds share their opinions on how to develop the innovation on an almost weekly basis. There are also weekly reflections on whether decision-making is in line with their norms, values and beliefs. Furthermore, they are most often evaluating whether the innovation activities are actually leading to the desired innovation. They persist in the belief that the development of their innovations is driven by their own norms, values and beliefs. For example, Abab is visually impaired and experienced marginalization as a member of an already marginalized community: ‘[his/her] passion for the rights of [the marginalised], and their inclusion and empowerment, was fuelled by moral outrage born from personal experience’. These rigid visionary social entrepreneurs also aim to make sure that their innovation stays close to their principles, as is the case with Krho, who is committed to making sure that: ‘all […] activities are based on three guiding principles to which all participating [organisations] must be firmly committed’.

The rigid visionary social entrepreneurs are highly engaged in stakeholder engagement, as the people/community affected, their supply-chain partners and NGOs provided them with insights on a weekly basis. They also had relatively frequent contacts with other entrepreneurs and financiers who offered their perspectives on the innovation. Not only are there frequent occasions for sharing insights, they also have a functioning stakeholder network with the right organizational skills, know-how and motivation to contribute to the innovation.

However, compared to negotiating visionaries, the stakeholders of these rigid visionary social entrepreneurs have relatively little decision-making power. Furthermore, they do not deviate from their initial plan, as their innovation process and the innovation outcome are similar to their initial plan. In fact, it is their stakeholders who have to adapt to the innovation to ensure that it is successfully implemented. Following on from this, one could argue that rigid visionary social entrepreneurs develop their innovations based on their own norms, values and beliefs, and they are committed to making sure that their innovation process and outcome live up to those norms, values and beliefs. However, this might be at the cost of possible adaptiveness of the innovation.

The social entrepreneurs following this approach to innovation are highly engaged in solving any knowledge gaps with regard to the process, outcome or the impact of the innovation. There are weekly activities leading to intra-firm knowledge generation and their staff members scan and bring in the necessary knowledge with the same frequency. There are also frequent activities for developing knowledge with external stakeholders or absorbing it from them. These social entrepreneurs can therefore be considered as ‘rigid visionaries’, since they focus on anticipation and reflexivity, and engage with stakeholders, but do not deviate from their initial ideas when it comes to the management of their innovation process and desired innovation outcome. An overview of the characteristics of the ‘rigid visionary’ social entrepreneurs and their enterprises, and a description of their innovations, can be found in . The radar chart in in Appendix 2 is a graphical representation of their scores on every dimension of responsible innovation compared to the mean scores of the other three typologies.

Table 5. Overview of the social entrepreneurs considered ‘rigid visionaries’.

The ‘negotiating’ visionary social innovators

These social entrepreneurs act as negotiators, as the development of their innovation is the result of the participation of stakeholders, who have actual decision-making power. They engage in most dimensions of responsible innovation but they pay less attention to reflexivity and knowledge management. The social entrepreneurs in this cluster can be considered as visionary entrepreneurs as they score very well on all elements of anticipation and also assess on a quarterly basis whether the innovation activities are actually leading to the desired innovation. The same holds for the frequency of people with different personal and professional backgrounds who share their opinion on the innovation. However, in comparison to the other social entrepreneurs, they rarely reflect on whether their decision-making is still in line with their own norms, values and beliefs.

The negotiating visionary social entrepreneurs have less frequent contact with stakeholders to share their opinion about the innovation, which holds especially true for the community/people affected. However, they are the only social entrepreneurs who have relatively frequent contact with research institutes to receive their insights. Even though the number of occasions where stakeholders share insights is limited, their stakeholder network does provide the right organizational skills, know-how and expertise. Their stakeholders respect each other's roles and are committed to contributing to the innovation. Furthermore, the negotiating entrepreneurs are the only social entrepreneurs who actually share decision-making power with their stakeholders to steer the innovation in the desired direction. These stakeholders can form their opinions based on complete information, and dialogues take place to help address different interests among stakeholders.

Furthermore, it seems that these social enterprises and the stakeholders are mutually responsive in this cluster because the processes and products of their innovations differ from their initial ideas, while at the same time the stakeholders have to adapt to the innovation to allow its implementation. Given that they reflect less on their own norms, values and beliefs, while sharing decision-making power with their stakeholders, it can be concluded that the innovation process and its outcome result from negotiation and co-creation with their stakeholders. Interestingly, even though these social entrepreneurs have relatively frequent contact with research institutes, they are relatively less engaged in acquiring the missing knowledge within the firm or developing knowledge with stakeholders. That said, their staff members often scan for external knowledge that can be internalized.

The profile descriptions of these types of social entrepreneurs were inconclusive in terms of why their processes and outputs differ from what these social entrepreneurs foresee at the start of the innovation process. However, one illustrative case is Nocl, who adjusted her focus from creating consumer awareness to changing business operations ‘as she discovered that informing consumers would not be enough to change the fishing industry’. Another illustrative case is Foha, who first acted on behalf of the Roma community (to contest their marginalization). After failing initially, she realized that ‘if the Roma were to succeed, it was going to be their self-organization skills and self-respect, which could only be achieved by experiencing change making first hand’. Sysu focused on a single aspect where the disabled faced a lack of opportunities [but] ‘as the years went by, she realized that her [social enterprise] had a role to play not just in the realm of international exchanges but more broadly in ensuring that [people] with disabilities affected international development agendas’. An overview of the characteristics of the ‘negotiating’ social entrepreneurs and their enterprises, and a description of their innovations, can be found in . The radar chart in in Appendix 2 is a graphical representation of their scores on every dimension of responsible innovation compared to the mean scores of the other three typologies.

Table 6. Overview of the social entrepreneurs considered ‘negotiating visionaries’.

Discussion and conclusion

The aim of this research was to identify different approaches adopted by social entrepreneurs to transform their initial ideas for innovation into final innovation outcomes. There are four different typologies for how social entrepreneurs manage to transform their initial ideas into innovative solutions that (help to) address societal problems. In general, it can be concluded that all four approaches to innovation are at least to some extent based on anticipatory governance of innovation and deliberative forms of stakeholder engagement. This also holds true for the rushing social entrepreneurs who engaged in anticipation, inclusion and deliberation but are less engaged in reflexivity, responsiveness and knowledge management.

The wayfinding social entrepreneurs engage in all dimensions of responsible innovation. However, their actions were less guided by a grand plan nor did they have alternative scenarios in place during the development of their social innovation, which is characteristic of effectuation in contrast to causation (Chandler et al. Citation2011; Sarasvathy Citation2001). Furthermore, wayfinding entrepreneurs are adaptive regarding their innovation process and subsequent outcomes, while ensuring that they stay in control of the decision-making during the innovation process. Focusing on adaptiveness and flexibility, while avoiding actions or relations that may lock them in, is one of the coping strategies in effectuation (Fisher Citation2012). Moreover, the eventual social innovation is different from what they initially foresaw, which is a typical result of applying effectuation in entrepreneurship (Chandler et al. Citation2011).

Bricolage is another strategy that can explain the emergence of entrepreneurship (Baker and Nelson Citation2005; Di Domenico, Haugh, and Tracey Citation2010) and social innovation (Goldstein, Hazy, and Silberstang Citation2010). It can be seen ‘as an alternative way to innovation rather than proceeding according to a grand plan’ (Goldstein, Hazy, and Silberstang Citation2010, 112), which is often applied in penurious environments (Baker and Nelson Citation2005; Fisher Citation2012). This is also the case for the innovations by wayfinders, who indicate that their stakeholder environment lacks multiple skills to contribute to their development. Although they do not operate according to a grand plan, they are highly reflexive regarding their innovation process, especially reflecting on whether the decision-making is in line with their own norms, values and beliefs. Bricolage revolves around resourcefulness, adaptiveness and recombining resources (Baker and Nelson Citation2005; Di Domenico, Haugh, and Tracey Citation2010). Knowledge sharing is essential in this, as the knowledge itself is recombined and can come from external actors, who might not be in a position to influence decisions (Goldstein, Hazy, and Silberstang Citation2010). Although the lack of a grand plan seems inconsistent with higher reflexivity, this does not have to be the case. ‘Bricolage is an emergent process that, in order to move ahead, needs to amplify weak feedback signals that indicate if the strategy for innovation is on or off target’ (Goldstein, Hazy, and Silberstang Citation2010, 112). It thus appears that the wayfinding entrepreneurs experienced a pathway of developmental emergence to vision, characterized as:

a ‘‘jigsaw puzzle’’ and eventually seeing the image emerge from this work as an “epiphany.” The entrepreneurial process of developmental vision begins with an aspiration to make the world better that seems to be operative through a set of values or beliefs that subsequently guides conscientious actions in this direction and ultimately results in the shaping of a vision (Waddock and Steckler Citation2016, 730).

The rigid visionary social entrepreneurs seem to have a clear plan for addressing a societal problem and make sure to stay close to their own norms and values that guide their decision-making. Since they also think of multiple scenarios to implement the innovation, it is fair to say that they engage in causation. They are engaging and deliberating with stakeholders. Yet they make sure that they remain in control of the development of the innovation. Consequently, the development and outcomes of their innovations are similar to their initial ideas. While some social entrepreneurs in this cluster function as illustrative cases, overall, the profile descriptions in this cluster were inconclusive as exceptions were encountered as well. However, one reason why these social entrepreneurs might prefer to pursue their own ideas, and aim to stay in control of their innovation, is because social innovation struggles against social and cultural inertia (Goldstein, Hazy, and Silberstang Citation2010). In that sense, the rigid visionary social entrepreneurs act more like ‘social engineers’ who ‘are usually driven by a missionary zeal and unbounded belief in the righteousness of their causes. Sometimes, it takes this dedication to transform a community or society’ (Zahra et al. Citation2009, 529). These social entrepreneurs might be walking the line between engaging with stakeholders to gain social and political legitimacy while making sure that their mission does not meet with resistance. This resistance can come from multiple forces that can be subtle and sometimes difficult to delineate, but are often formed by commonly held socio-cultural norms, conventions, and beliefs that differ from the ones held by the social innovator (Newth and Woods Citation2014).

The negotiating visionary social entrepreneurs have a clear plan about how to address the societal problem, and have thought of sufficient scenarios to implement the innovation. Hence, the social innovations of negotiating visionaries also appear to emerge from causation. This plan seems to be based on the principle of developing a solution together with other stakeholders, which may be more important than pursuing their own norms, values and beliefs for the social innovation. Moreover, they are the entrepreneurs who share actual decision-making power with the stakeholders involved. The findings suggest that the negotiating and rigid visionary entrepreneurs are more engaged in a deliberate vision pathway, i.e. a pathway in which visions precede clear intentions and subsequent actions (Waddock and Steckler Citation2016). However, in contrast to the rigid visionaries, who do not change or refine their visions and subsequent actions, the negotiating entrepreneurs are very responsive, as they ended up with different innovation processes and outcomes from those initially foreseen.

The procedural versus substantive approach to producing underlying norms, values and beliefs for innovation (Pellé Citation2016) can further help us to understand the results. The procedural approach implies that the underlying norms, values and beliefs that guide the innovation are actually the result of stakeholder deliberation. The procedural approach therefore appears to be closest to the development of social innovation by negotiating social entrepreneurs. The rigid social entrepreneurs, however, appear to be closer to a substantive approach as the underlying norms, values and beliefs that guide the innovation are predetermined. Furthermore, they do not deviate from their planned innovation process or the envisaged innovation outcome. These differences between social entrepreneurs were also found by Westley et al. (Citation2014), who identified social entrepreneurs who develop and scale their social innovations based on an inclusive and participatory process, whereby stakeholders have a direct voice regarding the social innovation, in contrast to social entrepreneurs who develop and scale their social innovations based on their own strong vision. The latter succeeded due to their consistency and drive without compromising their initially chosen vision and priorities (Westley et al. Citation2014). summarizes the key similarities and differences between the four identified approaches to develop innovative solutions for societal problems.

Table 7. Four typologies of developing innovative solutions for social problems by social entrepreneurs.

This article provides several contributions to the field of social innovation in social entrepreneurship. First of all, it discriminates between two types of visionary social entrepreneurs (i.e. the rigid and negotiating entrepreneurs), thereby adding to the typologies of Waddock and Steckler (Citation2016). Second, bricolage (Baker and Nelson Citation2005; Di Domenico, Haugh, and Tracey Citation2010) as well as effectuation (Sarasvathy Citation2001) provides partial explanations for wayfinding social entrepreneurs, which confirm the findings by Fisher (Citation2012) that these two different theories might not be mutually exclusive. The third contribution comes from the added value of responsible innovation when studying social innovations. The rigid social entrepreneurs seem to act as social engineers (Zahra et al. Citation2009) as they aim to stay in control of the innovation, do not deviate from their own norms, values and beliefs, and the social innovation process and outcome is similar to their initial idea. Such persistent social entrepreneurs may persuade their stakeholders to adopt the social innovations (Zahra et al. Citation2009), which may require the use of different rhetorical narratives for different stakeholders (Ruebottom Citation2013). However, since social innovations inherently have a profound impact on the public sphere, it can be argued that the development of these innovations should follow a public political process. Otherwise, it is merely the entrepreneurs’ conception of the ‘public good’ that they pursue (Cho Citation2006). However, responsible innovation aims to democratize the development of innovation (Owen, Macnaghten, and Stilgoe Citation2012; Von Schomberg Citation2013) by realizing anticipatory governance of innovation based on deliberative forms of stakeholder engagement. The framework of responsible innovation could therefore be an interesting avenue for future research to develop more responsible social innovations. Just as social innovation could advance the field of social entrepreneurship (Phillips et al. Citation2015), responsible innovation may advance social innovation and social entrepreneurship research. This article aims to function as a first step to introduce the concept of responsible innovation in social entrepreneurship research.

This study also has some limitations that need to be taken into account when interpreting the results. First of all, the sample size is relatively small for a cluster analysis and some dimensions have a lower scale reliability. Qualitative comparative analyses (QCA) is proposed as an alternative methodology for samples that are too small for complex quantitative analyses and too large for in-depth qualitative case studies. However, QCA is more suitable when testing relationships between dependent and independent variables and diminishes the richness of the data as it reduces variables to binary (or in some cases, three or four level) data. It is therefore not appropriate for exploratory study where researchers need to make use of the richness of the data. Nevertheless, there is no doubt that future studies in which anticipatory governance and deliberative forms of stakeholder engagement are empirically assessed could benefit from working with larger samples.

Another limitation is the fact that the concept of responsible innovation emerged from a predominantly European discourse, and is consequently based on liberal democratic values (Wong Citation2016). Which is why, among other reasons, the research lens of responsible research and innovation cannot be used one-on-one with innovation in the global south (Macnaghten et al. Citation2014). That is also why the deliberate decision was taken to include only social enterprises in this study that were founded in Europe, United States or Canada. However, this inherently means that results cannot be generalized beyond these geographical boundaries. The effective response rate is 15 percent; however, there did not seem to be a self-selection bias with regard to the type of social entrepreneur or their innovations. However, there is a lower response rate of social entrepreneurs active in the United States compared to their Canadian and European counterparts. This could be due to Ashoka's reputation in the United States, as these social entrepreneurs mentioned being contacted by researchers all too often.

Online_supplementary_file-1.docx

Download MS Word (107.4 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. In this article, the aim is to inform the reader why responsible innovation can serve as a suitable lens to study social innovations in social entrepreneurship. However, it is suggested to read Lubberink et al. (Citation2017a) for an extensive discussion about the differences and similarities between social innovation and responsible innovation, as a thorough discussion goes beyond the aim of this article.

2. The focus on the United States, Canada and Europe is because the framework of responsible innovation emerged from a European discourse and cannot be applied as an a-priori framework for innovation in the global South (Macnaghten et al. Citation2014).

3. These are the number of email recipients to whom the questionnaire was sent. However, some social enterprises were founded by two or more entrepreneurs. In other cases, other emails were suggested by the secretaries to get in direct contact with the founder. Therefore, the actual number of enterprises contacted was lower than 270.

4. The frequency of contacts with stakeholders is not included in the clustering method as it only gives information about the number of contacts with each type of stakeholder but does not give insights into the quality of the contacts. Hence, it is used as contextual information for the inclusion and deliberation dimensions.

5. The Calinski and Harabasz pseudo-F stopping rule index calculates the ratio of total variation between clusters versus total variation within a cluster. It provides values for the different cluster solutions in hierarchical clustering procedures. The optimum number of clusters is the highest value among the cluster solutions. The Je(2)/Je(1) index (Duda and Hart Citation1973) proposed a ratio criterion where Je(2) is the sum of the squared errors within a cluster when the data are broken into two clusters, and Je(1) provides the squared errors when there is one cluster. The rule for deciding the number of clusters is to determine the largest Je(2)/Je(1) value that corresponds to a low pseudo-T2 value and has a higher T2 value above and below it.

6. The profile descriptions contained on average 2,141 words, with 535 words standard deviation.

7. The Cronbach's alphas would experience a minor increase if items were excluded. However, the theoretical added value of the items is more important in this research than the scale reliability.

References

- Alvord, S. H., L. D. Brown, and C. W. Letts. 2004. “Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 40 (3): 260–282. doi:10.1177/0021886304266847.

- Ashoka. 2011. Everyone a Changemaker: 2011 Annual Report. Arlington, VA. https://www.ashoka.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/2011_annual_report.pdf

- Ayob, N., S. Teasdale, and K. Fagan. 2016. “How Social Innovation ‘Came to Be’: Tracing the Evolution of a Contested Concept.” Journal of Social Policy 45 (4): 635–653. doi:10.1017/S004727941600009X.

- Bacq, S., and F. Janssen. 2011. “The Multiple Faces of Social Entrepreneurship: A Review of Definitional Issues Based on Geographical and Thematic Criteria.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 23 (5–6): 373–403. doi:10.1080/08985626.2011.577242.

- Baker, T., and R. E. Nelson. 2005. “Creating Something from Nothing: Resource Construction Through Entrepreneurial Bricolage.” Administrative Science Quarterly 50 (3): 329–366. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329.

- Baron, R. A., and M. D. Ensley. 2006. “Opportunity Recognition as the Detection of Meaningful Patterns: Evidence from Comparisons of Novice and Experienced Entrepreneurs.” Management Science 52 (9): 1331–1344. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1060.0538.

- Blok, V., L. Hoffmans, and E. F. M. Wubben. 2015. “Stakeholder Engagement for Responsible Innovation in the Private Sector: Critical Issues and Management Practices.” Journal on Chain and Network Science 15 (2): 147–164. doi:10.3920/JCNS2015.x003.

- Blok, V., and P. Lemmens. 2015. “The Emerging Concept of Responsible Innovation. Three Reasons Why It is Questionable and Calls for a Radical Transformation of the Concept of Innovation.” In Responsible Innovation 2. 2nd ed., Vol. 2, edited by B.-J. Koops, J. van den Hoven, H. Romijn, T. Swierstra, and I. Oosterlaken, 19–35. Cham: Springer International.

- Burget, M., E. Bardone, and M. Pedaste. 2017. “Definitions and Conceptual Dimensions of Responsible Research and Innovation: A Literature Review.” Science and Engineering Ethics 23 (1): 1–19. doi:10.1007/s11948-016-9782-1.

- Calinski, T., and J. Harabasz. 1974. “A Dendrite Method for Cluster Analysis.” Communications in Statistics - Theory and Methods 3 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1080/03610927408827101.

- Chalmers, D. M., and E. Balan-Vnuk. 2013. “Innovating Not-for-Profit Social Ventures: Exploring the Microfoundations of Internal and External Absorptive Capacity Routines.” International Small Business Journal 31 (7): 785–810. doi:10.1177/0266242612465630.

- Chandler, G. N., D. R. DeTienne, A. McKelvie, and T. V. Mumford. 2011. “Causation and Effectuation Processes: A Validation Study.” Journal of Business Venturing 26 (3): 375–390. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.10.006.

- Chandra, Y., and L. Shang. 2017. “Unpacking the Biographical Antecedents of the Emergence of Social Enterprises: A Narrative Perspective.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28 (6): 2498–2529. doi:10.1007/s11266-017-9860-2.

- Cho, A. H. 2006. “Politics, Values and Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Appraisal.” In Social Entrepreneurship, edited by J. Mair, J. Robinson, and K. Hockerts, 34–56. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Choi, N., and S. Majumdar. 2014. “Social Entrepreneurship as an Essentially Contested Concept: Opening a New Avenue for Systematic Future Research.” Journal of Business Venturing 29 (3): 363–376. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.05.001.

- Choi, N., and S. Majumdar. 2015. “Social Innovation: Towards a Conceptualisation.” In Technology and Innovation for Social Change, edited by S. Majumdar, S. Guha, and N. Marakkath, 7–34. New Delhi: Springer India.