Abstract

How are social entrepreneurs different from commercial entrepreneurs? This study sheds light on this issue by applying the perspective of entrepreneurial cognition and by arguing that social entrepreneurs are even more susceptible to cognitive biases than commercial entrepreneurs. The empirical study of 205 Swiss entrepreneurs could confirm that social entrepreneurs tend to be more overconfident and prone to escalation of commitment than commercial entrepreneurs, while the study found no differences for illusion of control. The findings indicate that cognitive biases are an important puzzle piece to understand the differences between social and commercial entrepreneurs.

Introduction

When comparing social entrepreneurial and commercial entrepreneurial ventures, we encounter a striking puzzle: Social entrepreneurs are found to very persistently following their ideas, despite the success of their ventures being even more uncertain than the ventures of commercial entrepreneurs (Miller et al. Citation2012; Calic and Mosakowski Citation2016). Social entrepreneurs establish ventures primarily to meet social objectives rather than generate personal financial profit (Renko Citation2013). By combining social and commercial value creation, social entrepreneurs thereby face several challenges such as accountability to different stakeholders or ambiguity in performance measures due to the focus on dual goals (Mair, Mayer, and Lutz Citation2015). These challenges add to the challenges of being an entrepreneur per se. This research suggests cognitive biases as the important puzzle piece that explains why social entrepreneurs persist in their entrepreneurial endeavours despite facing these obstacles – and therein differ from commercial entrepreneurs.

Research has investigated how social entrepreneurs differ from commercial entrepreneurs (e.g. Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015; Dacin, Dacin, and Tracey Citation2011). Authors argue that the individual social entrepreneur takes a special role in social entrepreneurship as the intrinsic social motivation makes them pursue social entrepreneurial opportunities (Miller et al. Citation2012; Patzelt and Shepherd Citation2011). However, commercial entrepreneurs are also usually highly motivated to pursue their ideas (Uy, Foo, and Ilies Citation2015). Current social entrepreneurship literature studies personality traits to differentiate social entrepreneurs from commercial entrepreneurs (e.g. Nga and Shamuganathan Citation2010; Cohen, Kaspi-Baruch, and Katz Citation2019). However, the personality trait approach could only demonstrate limited success to explain differences between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs (Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002). Hence, the factors that differentiate social from commercial entrepreneurs require further theorising and empirical testing.

Entrepreneurship research recently turned towards a cognitive approach to understand entrepreneurs–and specifically to the promising lens of entrepreneurial bias (Zhang and Cueto Citation2017). The cognitive approach states that distinctive thinking and behaviours of entrepreneurial action result from unique individual cognitions (Holcomb et al. Citation2009). In this line of research, studies demonstrate that entrepreneurs are more likely than non-entrepreneurs to be prone to certain cognitive biases in their decision making (Forbes Citation2005; Mitchell et al. Citation2007). Because venture creation is related to high failure, cognitive biases could explain why entrepreneurs enter markets and pursue their ideas despite the low prospects of success (Barbosa, Fayolle, and Smith Citation2019).

Cognitive biases vary with the uncertainty and complexity of the environment (Simon, Houghton, and Aquino Citation2000) and the nature of the venture (Simon and Houghton Citation2002); the more uncertain the environment, the more likely can cognitive biases be observed. Because social entrepreneurship is an even more uncertain and complex endeavour than commercial entrepreneurship, social entrepreneurs’ enhanced susceptibility to cognitive biases can be the missing link to understand how social and commercial entrepreneurs differ. In this respect, Dacin, Dacin, and Tracey (Citation2011) also called for more research that connects entrepreneurial cognition and social entrepreneurship: ‘It would be interesting to compare the heuristics used in a social entrepreneurship context with those used in other entrepreneurial contexts […].’ (Dacin, Dacin, and Tracey Citation2011, 1210).

Therefore, this research applies the cognitive biases lens to social entrepreneurship and asks: Do social entrepreneurs differ from commercial entrepreneurs in showing stronger cognitive biases? This study focuses on the cognitive biases of overconfidence, escalation of commitment and illusion of control. These are among the most widely researched cognitive biases in entrepreneurship (Zhang and Cueto Citation2017; Cossette Citation2014), but to the best of the authors’ knowledge have never been studied in the context of social entrepreneurship.

Using primary data of a sample of 205 Swiss entrepreneurs, this study finds that social entrepreneurs are more prone to overconfidence and escalation of commitment than commercial entrepreneurs – but not to illusion of control. This study provides an important puzzle piece to social entrepreneurship literature by going beyond the study of motivation and by revealing differences in cognitive biases. The findings have implications for practice, as the cognitive biases have been found to have important behavioural implications (e.g. for risk-taking) and performance consequences (Zhang and Cueto Citation2017).

Theory and hypotheses development

Social and commercial entrepreneurs

Social entrepreneurship is presented as a promising market-based approach that can address grand societal problems (Saebi, Foss, and Linder Citation2019). While its definitions are manifold, the core of social entrepreneurship refers to a pro-active conduct that relates to opportunity recognition and opportunity exploitation (i.e. the development of new products, services, or business models) that target social value creation or social change (Hietschold et al. Citation2019). This focus on social value creation or social change is what differentiates social from commercial entrepreneurship. Consequently, social entrepreneurs have been defined as ‘individuals who establish enterprises primarily to meet social objectives rather than generate personal financial profit’ (Renko Citation2013, 1045).

Scholars study differences in personality characteristics between social and commercial entrepreneurs. For example, research found social entrepreneurs to be particularly optimistic (Gabarret, Vedel, and Decaillon Citation2017), committed (Miller et al. Citation2012), emotional (Miller et al. Citation2012; Ruskin, Seymour, and Webster Citation2016) and altruistic (Ruskin, Seymour, and Webster Citation2016). However, the value of the trait approach in understanding social entrepreneurs and difference between entrepreneurs is still debated (Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002). Using a cognitive lens might help to shed further light onto this discussion. Social entrepreneurial ventures face several challenges due to their dual mission, such as resource constraints (Austin, Stevenson, and Wei‐Skillern Citation2006), stakeholder legitimacy problems and unclear performance measurement (Renko Citation2013). The cognitive approach can be a promising lens to understand why individuals pursue such ventures and how they cope with the resulting challenges.

Entrepreneurial cognition

Social cognition scholars suggest that individual differences in beliefs, attitudes and personality can bias cognitive processing and behavioural outcomes (Arora, Haynie, and Laurence Citation2013). Thus, studying entrepreneurial cognition enables us to understand how entrepreneurs think and why they act in certain ways (Mitchell et al. Citation2002; Mitchell et al. Citation2007). Cognitive biases are a promising lens within entrepreneurial cognition research (Zhang and Cueto Citation2017). Biases ‘are cognitive mechanisms that assist people in fast decision making’ (Frese and Gielnik Citation2014, 424) and as such include mental short-cuts or rules-of-thumb. Consequently, these thought processes can involve erroneous inferences or deviations from a rational norm (Shepherd, Williams, and Patzelt Citation2015; Artinger et al. Citation2015).

Entrepreneurs who operate in an uncertain, unpredictable and complex environment where they lack adequate historical information, market information and organisational routines but need to make quick decisions have been shown to be particularly affected by these biases in their decision making (Shepherd, Williams, and Patzelt Citation2015; Zhang and Cueto Citation2017; Busenitz and Barney Citation1997; Baron Citation1998; Lowe and Ziedonis Citation2006). Entrepreneurs unintentionally simplify their information processing to reduce uncertainty (Simon, Houghton, and Aquino Citation2000), because deliberate and comprehensive decision making is often not possible (Holcomb et al. Citation2009). The cognitive biases affect individual perceptions and contribute to the entrepreneur’s positive evaluation of entrepreneurial opportunities and actions (Simon and Houghton Citation2002; De Carolis, Litzky, and Eddleston Citation2009).

Overconfidence, escalation of commitment and illusion of control are among the most important, and consequently, most researched biases in entrepreneurship (Zhang and Cueto Citation2017; Cossette Citation2014). The literature review (see Supplemental Appendix A1) shows that many articles about these biases focus on the difference between entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs, the conditions under which the biases arise and the outcomes of the biases. However, no research the authors know of to date investigates cognitive biases in social entrepreneurship. In the following, the article argues why social entrepreneurs are more prone to these three specific biases than commercial entrepreneurs.

Overconfidence

Overconfidence is the most often researched cognitive bias in entrepreneurship (Cossette Citation2014). It refers to the tendency to overestimate one’s abilities and the correctness of one’s decision when facing non-trivial issues (Barbosa, Fayolle, and Smith Citation2019; Frese and Gielnik Citation2014). It further expresses individuals’ failures to realise the limit of their knowledge (Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002) and is a measure for the extent that individuals ‘do not know what they do not know’ (Forbes Citation2005, 624). Overconfidence allows entrepreneurs to pursue an idea despite uncertainties in the decision-making situation and encourages them to take actions before uncertainties are resolved (Busenitz and Barney Citation1997). It further enables entrepreneurs to persist in challenging tasks (Hayward, Shepherd, and Griffin Citation2006).

The decision contexts in which overconfidence becomes most evident reflect potentially larger losses than gains, involve ambiguous information and low base rates of success. Entrepreneurs are particularly prone to display overconfidence because they face situations with large losses (e.g. personal funds) but also potential gains and low base rates of success of new ventures (Simon and Shrader Citation2012). Overconfident individuals can function better in entrepreneurial settings because they are not overwhelmed with the challenges (Busenitz Citation1999).

While previous research shows that entrepreneurs are more prone to overconfidence than other individuals (Busenitz and Barney Citation1997; Forbes Citation2005; Lee, Hwang, and Chen Citation2017), this study expects social entrepreneurs to be even more overconfident. One of the most persistently identified characteristics of social entrepreneurs is their intrinsic social motivation (e.g. Renko Citation2013); they firmly belief in the need to ‘do good’ and to tackle social and environmental problems. Because individuals who take on the challenges of social entrepreneurship strongly believe that they are pursuing what is right (Sundaramurthy, Musteen, and Randel Citation2013), they might tend to overestimate their abilities in developing and steering a social entrepreneurial venture and might more likely ignore information undermining their mission.

Moreover, and in line with the argument that ‘entrepreneurship attracts a certain kind of people, specifically, people who are less formal and rational in their thinking’ (Forbes Citation2005, 624), social entrepreneurship is even more prone to attract such people, because the context of social entrepreneurship is even more challenging and based on higher uncertainty of a successful outcome (Miller et al. Citation2012). While a rational evaluation of the odds will make individuals rather shed away from pursuing social entrepreneurial ventures, it will more likely be considered a viable option for individuals who tend to overestimate their abilities and prospects.

Social entrepreneurial ventures have even lower base rates of success than commercial ventures because they pursue the seemingly contradictory goals of social and financial value creation and operate in an uncertain context due to the different interests of their main stakeholders (Miller et al. Citation2012; Calic and Mosakowski Citation2016). Losses thereby not only relate to losing the venture and the funds invested in it, but also relate to not being able to address the social problem and to help beneficiaries whom the social entrepreneur feels obliged to help (Ruskin, Seymour, and Webster Citation2016). To persist in this challenging context, social entrepreneurs need to be overconfident in order to not be overwhelmed and to build entrepreneurial resilience. Previous social entrepreneurship literature found that social entrepreneurs are indeed overly optimistic (Gabarret, Vedel, and Decaillon Citation2017), which can be seen as an indication that they are also more overconfident.

Hypothesis 1: Social entrepreneurs tend to be more overconfident than commercial entrepreneurs.

Escalation of commitment

Escalation of commitment describes the tendency to continue investing time, effort or money into a failing course of action (Baron Citation1998; Wong, Yik, and Kwong Citation2006). The reasons for individuals’ escalation of commitment include a feeling of responsibility for their past decisions, sunk costs of high (monetary) efforts that have already been invested, psychological commitment to the course of action and fear of losing face in case of failure. Moreover, individuals’ desire to justify the initial decision, specifically initiated through the reception of negative feedback related to the current course of action, triggers a self-justification process that helps individuals make the initial decision appear more rational to themselves (Baron Citation1998; McCarthy, David Schoorman, and Cooper Citation1993; Markovitch et al. Citation2014).

Entrepreneurs are more prone to escalation of commitment because they feel personally responsible for all aspects of their venture and they are much more psychologically committed to their venture than others (McCarthy, David Schoorman, and Cooper Citation1993). Moreover, when individuals are socially and emotionally involved in projects, they are less likely to evaluate the projects objectively (Sleesman et al. Citation2018; Devigne, Manigart, and Wright Citation2016). Finally, escalation of commitment is more likely when the subjective expected utility is higher (Yang, Liu, et al. Citation2015).

While previous research shows that escalation of commitment is high among entrepreneurs (McCarthy, David Schoorman, and Cooper Citation1993; Baron Citation1998; Yang, Liu, et al. Citation2015), this study considers it even higher among social entrepreneurs. Individuals who decide to become social entrepreneurs tend to be empathic and altruistic (Miller et al. Citation2012; Ruskin, Seymour, and Webster Citation2016) as well as often locally embedded, which leads them to be particularly committed and emotionally involved in their venture and with their beneficiaries. Their intrinsic social motivation and belief in a good cause makes them psychologically committed to the course of action (Miller et al. Citation2012); consequently, they are willing to invest more and they will more vigorously defend their decisions, especially in cases of failure.

Prior research argues that escalation of commitment can vary across industry contexts. For example, escalation of commitment can be higher when outcomes are intangible and projects volatile to changes such as in the case of the software industry (Sleesman et al. Citation2018). This study expects that individuals in the context of social entrepreneurship are also more susceptible to escalation of commitment than in other contexts. Social entrepreneurs have a high personal responsibility for their venture and for their stakeholder who can be needy beneficiaries and who suffer substantial losses if the venture fails. Credibility is highly important for social entrepreneurs (Waddock and Post Citation1991) and social entrepreneurs can also be particularly prone to the fear of losing face because they do not want to admit failure in front of their many stakeholders such as their beneficiaries who might have put a lot of hope in the social entrepreneur.

Hypothesis 2: Social entrepreneurs tend more to escalation of commitment than commercial entrepreneurs.

Illusion of control

Illusion of control describes the tendency of individuals to overestimate the extent to which an outcome is under the control of their personal skills in situations where chance plays a role and skill is not necessarily the decisive factor for the outcome (Das and Teng Citation1999; Simon and Houghton Citation2002). Illusion of control differs from overconfidence in so far as overconfidence refers to overestimating one’s knowledge about information whereas illusion of control refers to overestimating one’s abilities to predict and cope with future outcomes (Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002; Simon, Houghton, and Aquino Citation2000). Illusion of control arises because a feeling of competence results from being able to control the environment and because skill and chance are often closely intertwined (Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002). Illusion of control gives a sense of certainty in uncertain situations because individuals convince themselves that they can control outcomes (De Carolis, Litzky, and Eddleston Citation2009).

Entrepreneurs are prone to illusion of control and by believing that they can control the outcome (e.g. venture success), they evaluate risks of the situation in a more positive light (e.g. success rates) (De Carolis, Litzky, and Eddleston Citation2009; Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002). Illusion of control can lead entrepreneurs to consider a limited number of alternatives in decision making so that their decision-making quality is finally lower (Carr and Blettner Citation2010).

While previous research shows that illusion of control relates to entrepreneurship in general (Simon, Houghton, and Aquino Citation2000), the authors believe that social entrepreneurship particularly attracts individuals who have a tendency to overestimate their control over outcomes. Research shows that perceived behavioural control, including aspects like controllability, entrepreneurial self-efficacy, and risk-taking self-efficacy, all of which can be considered an indication for illusion of control, has a positive effect on social entrepreneurial intentions (Kruse et al. Citation2019; Yang, Meyskens, et al. Citation2015). Individuals who benefit from a sense of certainty in uncertain environments are more likely to take on the challenge of pursuing social and economic goals at the same time. Moreover, social entrepreneurs need to believe in human agency to address grand societal problems such as poverty (Kury Citation2014). The complexity of and interrelation among the sustainable development goals (SDGs) illustrate the difficulty to control and predict actual interventions aimed at ‘doing good’ (George et al. Citation2016). Having an illusion of control enables individuals to consider themselves competent enough to address such large-scale problems.

Hypothesis 3: Social entrepreneurs tend more to illusion of control than commercial entrepreneurs.

Methodology

Sample and data

To test the hypotheses, this study gathered primary data through an online survey among Swiss entrepreneurs in summer 2019. Switzerland is an adequate country context for the study because it has a favourable entrepreneurship ecosystem (ranked second in the world according to the Global Entrepreneurship Index 2018Footnote1) and fosters social entrepreneurship through different organisation such as the SEIF foundationFootnote2 or the Schwab foundation,Footnote3 thus, assuring the presence of a broad number of different types of entrepreneurs. The authors contacted entrepreneurs of firms that were listed on large Swiss entrepreneurship platforms such as start-up.ch, membership lists from the impact hubs, lists of university spin-off such as those from Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule Zurich (ETH) or the Ecole Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), award lists such as those from the SEIF foundation award, Schwab foundation award or Swiss Tech Award, and venture capitalists’ investments lists such as those from Venture Kick or Credit Swiss Entrepreneur Capital AG. These broad data collection sources enabled us to contact entrepreneurs in general and social entrepreneurs in particular.

The authors contacted 2038 entrepreneurs and received 220 completed survey responses. The response rate was 10.8%Footnote4. This study assured with two questions that only nascent entrepreneurs (‘Are you currently trying to start your own business/to become self-employed?’) and active entrepreneurs (‘Are you already running your own business/are you already self-employed?’) responded (questions adopted from the Global University Entrepreneurial Spirit Students’ Survey, GUESSSFootnote5). The 15 respondents who did not fulfil this criterion were removed, providing us with a final sample size of 205 respondents.

Variables and measures

Dependent variable

This study identifies social entrepreneurs through a binary variable which was adopted from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM)Footnote6:

Are you, alone or with others, currently trying to start or currently owning and managing any kind of activity, organization or initiative that has a particularly social, environmental or community objective? This might include providing services or training to socially deprived or disabled persons, using profits for socially-oriented purposes, organizing self-help groups for community action, etc.

Respondents indicating ‘no’ were defined as commercial entrepreneurs and respondents who answered with ‘yes’ were defined as social entrepreneurs (Lepoutre et al. Citation2013). This approach is applied in other publications that study social entrepreneurship (Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015; Estrin, Mickiewicz, and Stephan Citation2013).

Independent variables

To measure overconfidence, this study used the approved approach of Busenitz and Barney (Citation1997). For a series of five questions with two answers whereof only one answer was objectively correct, respondents indicated whether they believe answer A or B is correct and provided on a scale from 50% (total guess) to 100% (total confident) their level of confidence for each answer. The authors updated the questions and/or adapted them to the Swiss context, asking participants e.g. ‘What is the average percentage of marriages in Switzerland that become divorced over time’. Following Busenitz and Barney (Citation1997), responses on the levels of confidence were grouped into one of six probability categories: 0.50–0.59, 0.60–0.69, 0.70–0.79, 0.80–0.89, 0.90–0.99 or 1.00. For each respondent, the authors calculated the mean probability score and subtracted the percentage of correct answers from this score. A positive score indicates overconfidence (higher mean level of confidence than percentage of correct answers) whereas a negative score indicates underconfidence (lower mean level of confidence than percentage of correct answers).

To measure escalation of commitment, this study relied on a widely applied scenario-based approach called the ‘blank radar plane’ case (Wong, Yik, and Kwong Citation2006). Respondents read a scenario where they were put into the position of a manager who had to decide if a project, in which he/she already invested a substantial amount of money and which turned out to be on a failing course of action, should be continued to receive investment or not. Participants indicated their willingness to continue investment in the project on a scale from 0% (absolutely no) to 100% (absolutely yes). A higher level of willingness to continue the project indicates a higher level of escalation of commitment.

To measure illusion of control, this study relied on the three-item scale used by Keh, Der Foo, and Lim (Citation2002). The scale measures the perception of the respondent’s ability to predict uncontrollable outcomes and the respondent’s belief that their skills are better than those of others (Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002). A sample item reads: ‘I can accurately forecast the total demand for my business’ (α = .69). For all scales, please see Supplemental Appendix A2.

Control variables

As the decision to become a social (vs. commercial) entrepreneur as well as the susceptibility for cognitive biases can depend on multiple factors, this study included several control variables. On the individual level, this study included age, gender (coded ‘1’ male and ‘2’ female), education (classification of the Swiss education system)Footnote7 (Nicolás, Rubio, and Fernández-Laviada Citation2018), prior social experience (Hockerts Citation2017), positive and negative affect (Gasper and Bramesfeld Citation2006), ambiguity tolerance (Herman et al. Citation2010), holistic reasoning (Choi et al. Citation2003), and the Big 5 personality traits (Gosling, Rentfrow, and Swann Citation2003). Prior research found, for example, that younger entrepreneurs are more susceptible to biases (Forbes Citation2005) and negative affect can correlate with escalation of commitment (Wong, Yik, and Kwong Citation2006). Moreover, prior social experience can have a strong influence on social entrepreneurial intent (Hockerts Citation2017). Finally, certain Big 5 personality traits (Nga and Shamuganathan Citation2010; Cohen, Kaspi-Baruch, and Katz Citation2019), but also integrative thinking (Maak, Pless, and Voegtlin Citation2016) or holistic reasoning (Muñoz and Dimov Citation2015) might be stronger in social entrepreneurs.

On the firm level, this study included whether the firm generates income (GEM, Lepoutre et al. Citation2013), its number of employees, firm foundation year and firm innovativeness (Wang Citation2008). For example, entrepreneurs in smaller and younger firms are more likely to be susceptible to biases (Forbes Citation2005). Moreover, an innovative organisational environment fosters innovative employee (eco-)initiatives (Ramus and Steger Citation2000).

On the environmental level, this study included different industry sectors as dummies (General Classification of Economic Activities (NOGA 38)),Footnote8 environmental hostility (Zahra and Garvis Citation2000), bridging social capital (discussion network size, Greve and Salaff (Citation2003)) and bonding social capital (self-employed parents, Davidsson and Honig (Citation2003)). Social capital can shape an entrepreneur’s cognitive characteristics (De Carolis, Litzky, and Eddleston Citation2009) and environmental complexity could relate to overconfidence (Hayward, Shepherd, and Griffin Citation2006; Simon and Shrader Citation2012). Likewise, some industry sectors are more likely to enable social entrepreneurship than others (Sieger et al. Citation2016).

Results

Descriptive statistics

shows the descriptive statistics and correlations for the full sample (n = 205) of social and commercial entrepreneurs. The sample is distributed equally among social entrepreneurs (n = 101) and commercial entrepreneurs (n = 104). Entrepreneurs are on average 43 years (SD = 10.52) old. 87.3% of the entrepreneurs are male, reflecting unequal gender ratios in entrepreneurship in general. Furthermore, the entrepreneurs are well educated with 13.7% having a bachelor degree, 43.9% a master degree and 33.2% a doctoral degree as their highest qualification. Not included in the table for space reasons is the control variable ‘industry’, which is a categorical variable with 39 categories. The largest industry sector in which the entrepreneurs operate is ‘IT and other information services’ (26.8%), followed by ‘Other services’ (9.3%), ‘Financial and insurance activities’ (6.8%), and ‘Human health services’ (6.8%). The ventures are relatively small and have on average 14 employees. Only two firms have more than 100 employees. Finally, 88 of the 101 social entrepreneurs indicated to generate income with their organisational activities, pointing to a majority of social ventures that follow a hybrid approach of social and economic value creation.

Table 1. Summary statistics and correlation matrix.

shows significant correlations between being a social entrepreneur and overconfidence (r = .140, p = .045), and escalation of commitment (r = .166, p = .018), but not between being a social entrepreneur and illusion of control (r = .114, p = .103).

Hypotheses testing

This study used two different data analysis procedures to test the hypotheses. First, the authors calculated a t-test for group differences between social and commercial entrepreneurs related to the biases. Second, the authors performed a logistic regression analysis where they first included only the control variables (Model 1), then successively added the biases (Model 2–4) and finally included all biases (Model 5). Other authors, such as Busenitz and Barney (Citation1997) and Koellinger, Minniti, and Schade (Citation2007) also use different types of populations as a (binary) dependent variable when studying biases.

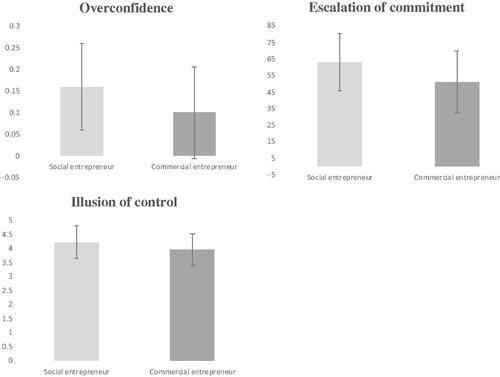

The results of the t-tests demonstrate that social entrepreneurs have significantly higher levels of overconfidence (t = −2.018, p = .045) and escalation of commitment (t = −2.385, p = .018), but not illusion of control (t = −1.639, p = .103) when compared to commercial entrepreneurs (see and ).

Figure 1. Mean differences in cognitive biases between social entrepreneurs and commercial entrepreneurs. Note: Bars indicate mean values and lines indicate standard deviations.

Table 2. Mean differences between social entrepreneurs and commercial entrepreneurs.

presents the results of the logistic regression analysis. The unstandardised regression coefficients are positive and significant for overconfidence (Model 2, B = 2.02, p = .051) and escalation of commitment (Model 3, B = .013, p = .048), but not for illusion of control (Model 3, B = .14, p = .472). Likewise, the joint integration of all cognitive biases as independent variables in one model (Model 5) shows positive and significant coefficients for overconfidence (B = 2.48, p = .024) and escalation of commitment (B = .015, p = .026), but not for illusion of control (B = .16, p = .425). To test for multicollinearity issues, this study calculated the variance inflation factors (VIFs). All VIFs were below three and are therefore below the critical threshold of 10 (Hechavarría et al. Citation2018) (results available from the authors; for the robustness tests, see Appendix).

Table 3. Logistic regression analysis for the effects of cognitive biases on the likelihood of being a social entrepreneur (n = 185).

The results of the t-test and the logistic regression analysis consistently support hypothesis 1 and hypothesis 2, but not hypothesis 3.

Discussion

This paper introduces cognitive biases into social entrepreneurship research and sheds light on relevant differences between social and commercial entrepreneurs. The results show that social entrepreneurs tend to be more overconfident and prone to escalation of commitment than commercial entrepreneurs. However, this study could not confirm that social entrepreneurs are more prone to illusion of control. A possible explanation for the non-significant result is that both social and commercial entrepreneurs know that the decision to start a venture and its success do not solely depend on the agency of the individual entrepreneur. Specifically, in the Swiss context, entrepreneurship depends on networks and political support – and this is important for both social and commercial entrepreneurship.

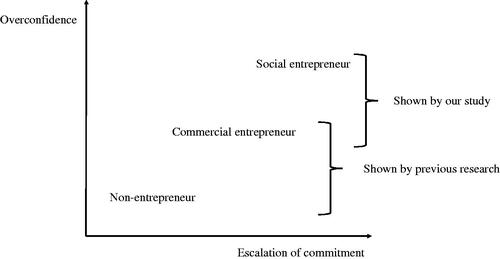

The findings inform theory related to social entrepreneurial venture foundation and success. The results indicate that it is not only care and concern for others or the environment (Patzelt and Shepherd Citation2011), but also the belief in the self (overconfidence) and their project (expressed via an increasing escalation of commitment) that distinguish social from commercial entrepreneurs. While previous research debated whether social entrepreneurship conceptually differs from commercial entrepreneurship (Dacin, Tina Dacin, and Matear Citation2010) and which the differentiating characteristics are (Nga, Hwee, and Shamuganathan Citation2010; Cohen, Kaspi-Baruch, and Katz Citation2019), the personality trait approach is not conclusive (Keh, Der Foo, and Lim Citation2002). This study introduces cognitive biases as a missing link in this debate. More specifically, this study shows that it is the cognition of entrepreneurs that differs, beyond their motivation and related personality traits. Previous research on entrepreneurial cognition demonstrated that entrepreneurs are more prone to show cognitive biases when compared to non-entrepreneurs. This study shows now that susceptibility to cognitive biases among entrepreneurs is not uniform and that different types of entrepreneurs vary in cognitive biases (see ), underscoring the relevance of investigating differences among entrepreneurs.

Figure 2. Differences in cognitive biases between social entrepreneurs, commercial entrepreneurs and non-entrepreneurs.

The greater susceptibility of social entrepreneurs to these biases might be one reason why individuals enter social entrepreneurship but often fail, as the biases have been associated with higher chances for market entry but at the same time lower performance outcomes (Hayward, Shepherd, and Griffin Citation2006; Gudmundsson and Lechner Citation2013; Koellinger, Minniti, and Schade Citation2007). In general, the cognitive biases of overconfidence and escalation of commitment have been found to have both negative and positive consequences (see Supplemental Appendix A1); for instance, overconfident entrepreneurs more likely invest insufficient resources in their ventures (Hayward, Shepherd, and Griffin Citation2006), but the positive emotions triggered through overconfidence also enhance entrepreneurial resilience (Hayward et al. Citation2010). Knowing that social entrepreneurial decision-making is specifically affected by these biases can help to create awareness and avoid the potentially negative consequences. This could for example inform (social) entrepreneurial training in incubators.

The results of our study also contribute to the literature on cognitive biases in general. The findings that social entrepreneurs are more prone to overconfidence and escalation of commitment indicate that there is a link between cognitive biases and individuals’ motivation. More specifically, a social motivation relates to cognitive biases because individuals strongly believe in the cause and want to succeed in ‘doing good’ despite the odds. Similar to stronger loss than gain-frames that individuals often hold (Kahneman, Slovic, and Tversky Citation1982; Kahneman Citation2011) it might be that a ‘doing good’-frame makes individuals more prone to cognitive biases. Future research could investigate in more detail the interaction between a social motivation and cognitive biases and try to see if both are related to certain personality characteristics. In addition, the results indicate that the biases of overconfidence and escalation of commitment relate to each other in the context of social entrepreneurship (Sleesman et al. Citation2018). Because both biases describe an exaggerated belief in personal aspects (i.e. the self in the case of overconfidence and the project in the case of escalation of commitment), they might also relate to each other in other, more generic contexts. The authors would encourage future research to study the interrelation between these cognitive biases more generally.

While the study presents the first results on differences in cognitive biases between social and commercial entrepreneurs, this study can make no causal inferences and future research might want to test cognitive biases among social entrepreneurs using experimental or longitudinal designs. Literature suggests that cognitive biases are both, part of individuals’ personality and influenced by the context (Barbosa, Fayolle, and Smith Citation2019). This means that individuals self-select into entrepreneurship because of these specific traits, but also develop cognitive biases as a response to the uncertain environment that rewards entrepreneurs with a particular way of thinking (Forbes Citation2005; Grégoire, Corbett, and McMullen Citation2011). Previous research did not conclude yet whether self-selection based on personal inclinations or adaptation to the uncertain context cause stronger cognitive biases in entrepreneurs (Forbes Citation2005; Grégoire, Corbett, and McMullen Citation2011). In the sample, the authors find no mean difference in cognitive biases between nascent entrepreneurs who have not yet been overly exposed to the context and active entrepreneurs, lending some support to the trait-like nature of these cognitive biases. The study also controlled for several environmental influences and tested for reverse causality (see robustness test in the Appendix). The authors would encourage future research to investigate in more detail the influence of individual experiences and the context in shaping the cognitive biases of social entrepreneurs over time.

Moreover, this study defines and operationalises social entrepreneurs according to their focus on social value creation when establishing ventures. Our sample characteristics further show that most of the ventures follow a hybrid approach of social and commercial value creation. Other authors differentiate social entrepreneurs from commercial entrepreneurs according to their pro-social motivation, the social sector in which they operate or the non-profit character of the organisation (Dacin, Tina Dacin, and Matear Citation2010; Lautermann Citation2013). Each of these definitions has advantaged but also conceptual shortcomings, for example, social and economic value creation are closely intertwined, the measurement of social value is conceptually and empirically complex and the motivation and firm focus can change over time. In this study, entrepreneurs self-assessed whether their venture focuses on social value creation. While entrepreneurs themselves might have the best insights into their ventures to correctly assess their strategic focus, entrepreneurs could also give socially desirable answers. This study limited this potential bias by including third party assessments in the sample selection. The authors specifically contacted also entrepreneurs where third parties such as the SEIF or Schwab foundations assessed the ventures explicitly as social ventures. However, the authors would encourage future research to test the results using different definitions of social entrepreneurship and external evaluations to categorise entrepreneurial ventures.

Finally, future research might want to explore in more detail if it is the strength of the social motivation or the anticipation of the complexity of dealing with social and economic goals (hybridity) that makes social entrepreneurs more prone to cognitive biases. Cognitive biases might depend on where on the hybrid spectrum a social venture is located and future research could study if cognitive biases are more prevalent when entrepreneurs set out to establish ventures that try to balance social and economic goals or when the social purpose dominates over the economic goals.

Overall, the authors hope that the results will stimulate further research on the cognition of social entrepreneurs.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (24.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23 KB)Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the feedback of Philipp Sieger. We also thank Diana Baumann, Silvia Barri, Kaj Reinthaler and Nico Kernen for their help in contacting the firms during data collection.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Gobal Entrepreneurship Index 2018: https://thegedi.org/global-entrepreneurship-and-development-index/

2 SEIF foundation: https://seif.org/en/impact-entrepreneurs/

3 Schwab foundation: https://www.cinfo.ch/de/schwab-foundation-social-entrepreneurship

4 Small response rates below 25% are not uncommon in entrepreneurship research (e.g., Yu, Wiklund, and Pérez-Luño Citation2021; Moore, McIntyre, and Lanivich Citation2019).

References

- Arora, Punit, J. Michael Haynie, and Gregory A. Laurence. 2013. “Counterfactual Thinking and Entrepreneurial Self–Efficacy: The Moderating Role of Self–Esteem and Dispositional Affect.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (2): 359–385. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00472.x.

- Artinger, Florian, Malte Petersen, Gerd Gigerenzer, and Jürgen Weibler. 2015. “Heuristics as Adaptive Decision Strategies in Management.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 36 (S1): S33–S52. doi:10.1002/job.1950.

- Austin, James, Stevenson, Howard, and Jane Wei‐Skillern. 2006. “Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x.

- Barbosa, Saulo Dubard, Alain Fayolle, and Brett R. Smith. 2019. “Biased and Overconfident, Unbiased but Going for It: How Framing and Anchoring Affect the Decision to Start a New Venture.” Journal of Business Venturing 34 (3): 528–557. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.12.006.

- Baron, Robert A. 1998. “Cognitive Mechanisms in Entrepreneurship: Why and When Enterpreneurs Think Differently than Other People.” Journal of Business Venturing 13 (4): 275–294. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00031-1.

- Busenitz, Lowell W., and Jay B. Barney. 1997. “Differences between Entrepreneurs and Managers in Large Organizations: Biases and Heuristics in Strategic Decision-Making.” Journal of Business Venturing 12 (1): 9–30. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(96)00003-1.

- Busenitz, Lowell W. 1999. “Entrepreneurial Risk and Strategic Decision Making: It’s a Matter of Perspective.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 35 (3): 325–340. doi:10.1177/0021886399353005.

- Calic, Goran, and Elaine Mosakowski. 2016. “Kicking off Social Entrepreneurship: How a Sustainability Orientation Influences Crowdfunding Success.” Journal of Management Studies 53 (5): 738–767. doi:10.1111/joms.12201.

- Carr, Jon C., and Daniela P. Blettner. 2010. “Cognitive Control Bias and Decision-Making in Context: Implications for Entrepreneurial Founders of Small Firms.” Frontiers of Entrepreneurship Research 30 (6): 1–15.

- Choi, Incheol, Reeshad Dalal, Chu Kim-Prieto, and Hyekyung Park. 2003. “Culture and Judgement of Causal Relevance.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 84 (1): 46–59.

- Cohen, Hilla, Oshrit Kaspi-Baruch, and Hagai Katz. 2019. “The Social Entrepreneur Puzzle: The Background, Personality and Motivation of Israeli Social Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (2): 211–231. doi:10.1080/19420676.2018.1541010.

- Cossette, Pierre. 2014. “Heuristics and Cognitive Biases in Entrepreneurs: A Review of the Research.” Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship 27 (5): 471–496. doi:10.1080/08276331.2015.1105732.

- Dacin, M. Tina, Peter A. Dacin, and Paul Tracey. 2011. “Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1203–1213. doi:10.1287/orsc.1100.0620.

- Dacin, Peter A., M. Tina Dacin, and Margaret Matear. 2010. “Social Entrepreneurship: Why We Don't Need a New Theory and How we Move Forward from Here.” Academy of Management Perspectives 24 (3): 37–57.

- Das, T. K., and Bing‐Sheng Teng. 1999. “Cognitive Biases and Strategic Decision Processes: An Integrative Perspective.” Journal of Management Studies 36 (6): 757–778. doi:10.1111/1467-6486.00157.

- Davidsson, Per, and Benson Honig. 2003. “The Role of Social and Human Capital among Nascent Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Business Venturing 18 (3): 301–331. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6.

- De Carolis, Donna Marie, Barrie E. Litzky, and Kimberly A. Eddleston. 2009. “Why Networks Enhance the Progress of New Venture Creation: The Influence of Social Capital and Cognition.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33 (2): 527–545. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00302.x.

- Devigne, David, Sophie Manigart, and Mike Wright. 2016. “Escalation of Commitment in Venture Capital Decision Making: Differentiating between Domestic and International Investors.” Journal of Business Venturing 31 (3): 253–271. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.01.001.

- Estrin, Saul, Tomasz Mickiewicz, and Ute Stephan. 2013. “Entrepreneurship, Social Capital, and Institutions: Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship across Nations.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (3): 479–504. doi:10.1111/etap.12019.

- Forbes, Daniel P. 2005. “Are Some Entrepreneurs More Overconfident than Others?” Journal of Business Venturing 20 (5): 623–640. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2004.05.001.

- Frese, Michael, and Michael M. Gielnik. 2014. “The Psychology of Entrepreneurship.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1 (1): 413–438. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091326.

- Gabarret, Ines, Benjamin Vedel, and Julien Decaillon. 2017. “A Social Affair: identifying Motivation of Social Entrepreneurs.” International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business 31 (3): 399–415. doi:10.1504/IJESB.2017.084845.

- Gasper, Karen, and Kosha D. Bramesfeld. 2006. “Should I Follow My Feelings? How Individual Differences in following Feelings Influence Affective Well-Being, Experience, and Responsiveness.” Journal of Research in Personality 40 (6): 986–1014. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.10.001.

- George, Gerard, Jennifer Howard-Grenville, Aparna Joshi, and Laszlo Tihanyi. 2016. “Understanding and Tackling Societal Grand Challenges through Management Research.” Academy of Management Journal 59 (6): 1880–1895. doi:10.5465/amj.2016.4007.

- Gosling, Samuel D., Peter J. Rentfrow, and William B. Swann. 2003. “A Very Brief Measure of the Big-Five Personality Domains.” Journal of Research in Personality 37 (6): 504–528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1.

- Grégoire, Denis A., Andrew C. Corbett, and Jeffery S. McMullen. 2011. “The Cognitive Perspective in Entrepreneurship: An Agenda for Future Research.” Journal of Management Studies 48 (6): 1443–1477. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00922.x.

- Greve, Arent, and Janet W. Salaff. 2003. “Social Networks and Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 28 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/1540-8520.00029.

- Gudmundsson, Sveinn Vidar, and Christian Lechner. 2013. “Cognitive Biases, Organization, and Entrepreneurial Firm Survival.” European Management Journal 31 (3): 278–294. doi:10.1016/j.emj.2013.01.001.

- Hayward, Mathew L. A., Dean A. Shepherd, and Dale Griffin. 2006. “A Hubris Theory of Entrepreneurship.” Management Science 52 (2): 160–172. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1050.0483.

- Hayward, Mathew L. A., William R. Forster, Saras D. Sarasvathy, and Barbara L. Fredrickson. 2010. “Beyond Hubris: How Highly Confident Entrepreneurs Rebound to Venture Again.” Journal of Business Venturing 25 (6): 569–578. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.03.002.

- Hechavarría, Diana M., Siri A. Terjesen, Pekka Stenholm, Malin Brännback, and Stefan Lång. 2018. “More than Words: do Gendered Linguistic Structures Widen the Gender Gap in Entrepreneurial Activity?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 42 (5): 797–817. doi:10.1177/1042258718795350.

- Herman, Jeffrey L., Michael J. Stevens, Allan Bird, Mark Mendenhall, and Gary Oddou. 2010. “The Tolerance for Ambiguity Scale: Towards a More Refined Measure for International Management Research.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34 (1): 58–65. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.09.004.

- Hietschold, Nadine, Christian Voegtlin, Andreas Georg Scherer, and Joel Gehman. 2019. “What We Know and Don’t Know about Social Innovation: A Multi-Level Review and Research Agenda.” In Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings, edited by Guclu Atinc. Boston: Academy of Management.

- Hockerts, Kai. 2017. “Determinants of Social Entrepreneurial Intentions.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (1): 105–130. doi:10.1111/etap.12171.

- Holcomb, Tim R., R. Duane Ireland, R. Michael Holmes Jr, and Michael A. Hitt. 2009. “Architecture of Entrepreneurial Learning: Exploring the Link among Heuristics, Knowledge, and Action.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 33 (1): 167–192. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00285.x.

- Kahneman, Daniel, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky. 1982. Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kahneman, Daniel. 2011. Thinking, Fast and Slow. London: Penguin.

- Keh, Hean Tat., Maw Der Foo, and Boon Chong Lim. 2002. “Opportunity Evaluation under Risky Conditions: The Cognitive Processes of Entrepreneurs.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27 (2): 125–148. doi:10.1111/1540-8520.00003.

- Koellinger, Philipp, Maria Minniti, and Christian Schade. 2007. “I Think I Can, I Think I Can”: Overconfidence and Entrepreneurial Behavior.” Journal of Economic Psychology 28 (4): 502–527. doi:10.1016/j.joep.2006.11.002.

- Kruse, Philipp, Dominika Wach, Sílvia Costa, and Juan Antonio Moriano. 2019. “Values Matter, Don’t They?–Combining Theory of Planned Behavior and Personal Values as Predictors of Social Entrepreneurial Intention.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (1): 55–83. doi:10.1080/19420676.2018.1541003.

- Kury, Kenneth Wm. 2014. “A Developmental and Constructionist Perspective on Social Entrepreneur Mobilisation.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Venturing 6 (1): 22–36. doi:10.1504/IJEV.2014.059403.

- Lautermann, Christian. 2013. “The Ambiguities of (Social) Value Creation: Towards an Extended Understanding of Entrepreneurial Value Creation for Society.” Social Enterprise Journal 9 (2): 184–202. doi:10.1108/SEJ-01-2013-0009.

- Lee, Joon Mahn, Byoung‐Hyoun Hwang, and Hailiang Chen. 2017. “Are Founder CEOs More Overconfident than Professional CEOs? Evidence from S&P 1500 Companies.” Strategic Management Journal 38 (3): 751–769. doi:10.1002/smj.2519.

- Lepoutre, Jan, Rachida Justo, Siri Terjesen, and Niels Bosma. 2013. “Designing a Global Standardized Methodology for Measuring Social Entrepreneurship Activity: The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Social Entrepreneurship Study.” Small Business Economics 40 (3): 693–714. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9398-4.

- Lowe, Robert A., and Arvids A. Ziedonis. 2006. “Overoptimism and the Performance of Entrepreneurial Firms.” Management Science 52 (2): 173–186. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1050.0482.

- Maak, Thomas, Nicola M. Pless, and Christian Voegtlin. 2016. “Business Statesman or Shareholder Advocate? CEO Responsible Leadership Styles and the Micro‐Foundations of Political CSR.” Journal of Management Studies 53 (3): 463–493. doi:10.1111/joms.12195.

- Mair, Johanna, Judith Mayer, and Eva Lutz. 2015. “Navigating Institutional Plurality: Organizational Governance in Hybrid Organizations.” Organization Studies 36 (6): 713–739. doi:10.1177/0170840615580007.

- Markovitch, Dmitri G., Dongling Huang, Lois Peters, B. V. Phani, Deepu Philip, and William Tracy. 2014. “Escalation of Commitment in Entrepreneurship-Minded Groups.” International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research 20 (4): 302–323. doi:10.1108/IJEBR-08-2013-0127.

- McCarthy, Anne M., F. David Schoorman, and Arnold C. Cooper. 1993. “Reinvestment Decisions by Entrepreneurs: Rational Decision-Making or Escalation of Commitment?” Journal of Business Venturing 8 (1): 9–24. doi:10.1016/0883-9026(93)90008-S.

- Miller, Toyah L., Matthew G. Grimes, Jeffery S. McMullen, and Timothy J. Vogus. 2012. “Venturing for Others with Heart and Head: How Compassion Encourages Social Entrepreneurship.” Academy of Management Review 37 (4): 616–640. doi:10.5465/amr.2010.0456.

- Mitchell, Ronald K., Lowell Busenitz, Theresa Lant, Patricia P. McDougall, Eric A. Morse, and J. Brock Smith. 2002. “Toward a Theory of Entrepreneurial Cognition: Rethinking the People Side of Entrepreneurship Research.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27 (2): 93–104. doi:10.1111/1540-8520.00001.

- Mitchell, Ronald K., Lowell W. Busenitz, Barbara Bird, Connie Marie Gaglio, Jeffery S. McMullen, Eric A. Morse, and J. Brock Smith. 2007. “The Central Question in Entrepreneurial Cognition Research 2007.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 31 (1): 1–27. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2007.00161.x.

- Moore, Curt B., Nancy H. McIntyre, and Stephen E. Lanivich. 2019. “ADHD-Related Neurodiversity and the Entrepreneurial Mindset.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 15 (1): 64–91.

- Muñoz, Pablo, and Dimo Dimov. 2015. “The Call of the Whole in Understanding the Development of Sustainable Ventures.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (4): 632–654. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.07.012.

- Nga, Joyce, Koe Hwee, and Gomathi Shamuganathan. 2010. “The Influence of Personality Traits and Demographic Factors on Social Entrepreneurship Start up Intentions.” Journal of Business Ethics 95 (2): 259–282.

- Nicolás, Catalina, Alicia Rubio, and Ana Fernández-Laviada. 2018. “Cognitive Determinants of Social Entrepreneurship: Variations according to the Degree of Economic Development.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9 (2): 154–168. doi:10.1080/19420676.2018.1452280.

- Patzelt, Holger, and Dean A. Shepherd. 2011. “Recognizing Opportunities for Sustainable Development.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 35 (4): 631–652. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00386.x.

- Ramus, Catherine A., and Ulrich Steger. 2000. “The Roles of Supervisory Support Behaviors and Environmental Policy in Employee “Ecoinitiatives” at Leading-Edge European Companies.” Academy of Management Journal 43 (4): 605–626.

- Renko, Maija. 2013. “Early Challenges of Nascent Social Entrepreneurs.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 37 (5): 1045–1069. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00522.x.

- Ruskin, Jennifer, Richard G. Seymour, and Cynthia M. Webster. 2016. “Why Create Value for Others? An Exploration of Social Entrepreneurial Motives.” Journal of Small Business Management 54 (4): 1015–1037. doi:10.1111/jsbm.12229.

- Saebi, Tina, Nicolai J. Foss, and Stefan Linder. 2019. “Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Achievements and Future Promises.” Journal of Management 45 (1): 70–95. doi:10.1177/0149206318793196.

- Shepherd, Dean A., Trenton A. Williams, and Holger Patzelt. 2015. “Thinking about Entrepreneurial Decision Making: Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Management 41 (1): 11–46. doi:10.1177/0149206314541153.

- Sieger, Philipp, Marc Gruber, Emmanuelle Fauchart, and Thomas Zellweger. 2016. “Measuring the Social Identity of Entrepreneurs: Scale Development and International Validation.” Journal of Business Venturing 31 (5): 542–572. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.07.001.

- Simon, Mark, and Rodney C. Shrader. 2012. “Entrepreneurial Actions and Optimistic Overconfidence: The Role of Motivated Reasoning in New Product Introductions.” Journal of Business Venturing 27 (3): 291–309. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.04.003.

- Simon, Mark, and Susan M. Houghton. 2002. “The Relationship among Biases, Misperceptions, and the Introduction of Pioneering Products: Examining Differences in Venture Decision Contexts.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 27 (2): 105–124. doi:10.1111/1540-8520.00002.

- Simon, Mark, Susan M. Houghton, and Karl Aquino. 2000. “Cognitive Biases, Risk Perception, and Venture Formation: How Individuals Decide to Start Companies.” Journal of Business Venturing 15 (2): 113–134. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(98)00003-2.

- Sleesman, Dustin J., Anna C. Lennard, Gerry McNamara, and Donald E. Conlon. 2018. “Putting Escalation of Commitment in Context: A Multilevel Review and Analysis.” Academy of Management Annals 12 (1): 178–207. doi:10.5465/annals.2016.0046.

- Stephan, Ute, Lorraine M. Uhlaner, and Christopher Stride. 2015. “Institutions and Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Institutional Voids, Institutional Support, and Institutional Configurations.” Journal of International Business Studies 46 (3): 308–331. doi:10.1057/jibs.2014.38.

- Sundaramurthy, Chamu, Martina Musteen, and Amy E. Randel. 2013. “Social Value Creation: A Qualitative Study of Indian Social Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship 18 (02): 1350011. doi:10.1142/S1084946713500118.

- Uy, Marilyn A., Maw-Der Foo, and Remus Ilies. 2015. “Perceived Progress Variability and Entrepreneurial Effort Intensity: The Moderating Role of Venture Goal Commitment.” Journal of Business Venturing 30 (3): 375–389. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2014.02.001.

- Waddock, Sandra A., and James E. Post. 1991. “Social Entrepreneurs and Catalytic Change.” Public Administration Review 51 (5): 393–401. doi:10.2307/976408.

- Wang, Catherine L. 2008. “Entrepreneurial Orientation, Learning Orientation, and Firm Performance.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 32 (4): 635–657. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2008.00246.x.

- Wong, Kin Fai Ellick, Michelle Yik, and Jessica Y. Y. Kwong. 2006. “Understanding the Emotional Aspects of Escalation of Commitment: The Role of Negative Affect.” The Journal of Applied Psychology 91 (2): 282–297. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.91.2.282.

- Yang, Jun, Yiran Liu, Yuli Zhang, Hao Chen, and Fang Niu. 2015. “Escalation Bias among Technology Entrepreneurs: The Moderating Effects of Motivation and Mental Budgeting.” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 27 (6): 693–708. doi:10.1080/09537325.2015.1034674.

- Yang, Rui, Moriah Meyskens, Congcong Zheng, and Lingyan Hu. 2015. “Social Entrepreneurial Intentions: China versus the USA–Is There a Difference?” The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation 16 (4): 253–267. doi:10.5367/ijei.2015.0199.

- Yu, Wei, Johan Wiklund, and Ana Pérez-Luño. 2021. “ADHD Symptoms, Entrepreneurial Orientation (EO), and Firm Performance.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice in Practice 45 (1): 92–117. doi:10.1177/1042258719892987.

- Zahra, Shaker A., and Dennis M. Garvis. 2000. “International Corporate Entrepreneurship and Firm Performance: The Moderating Effect of International Environmental Hostility.” Journal of Business Venturing 15 (5-6): 469–492. doi:10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00036-1.

- Zhang, Stephen X., and Javier Cueto. 2017. “The Study of Bias in Entrepreneurship.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 41 (3): 419–454. doi:10.1111/etap.12212.

Appendix

Robustness Tests

The results (Model 5) do not change substantially if the study includes only such founders whose firms generate income or if the study reduces the control variables to a minimum (age, gender, education, prior social experience, number of employees, firm foundation year).

Furthermore, greater risk propensity could be a reason why individuals could become social entrepreneurs and risk perception could mediate the relationship between biases and becoming a social entrepreneur. The authors therefore included risk propensity (Simon, Houghton, and Aquino Citation2000) as control variable in the logistic regression model (Model 5): the significance of the independent variables’ coefficients remained although risk propensity significantly influenced the dependent variable. Moreover, this study tested whether the biases influence risk propensity and included risk propensity as a dependent variable in a linear regression model (same controls and biases included in linear regression model as in logistic regression models) as well as risk propensity as a mediator between the biases as independent variables and social entrepreneur as dependent variable in a mediation model (short set of controls as above and biases included in mediation models); the biases did not significantly influence risk propensity and the indirect effect of the mediator was not significant. The authors can therefore exclude the possibility that risk propensity is a decisive mediating variable.

This study also tested a reverse causality approach. Specifically, this study followed authors such as Forbes (Citation2005); Lee, Hwang, and Chen (Citation2017); Simon and Shrader (Citation2012) and calculated linear regression models where each bias represents the dependent variable and the variable social entrepreneur the independent variable (same controls and other biases included in this linear regression model as in logistic regression models). This study found that the unstandardised coefficient for the independent variable social entrepreneur is positive and (marginally) significant for the models with overconfidence (B = .08, p = .047) and escalation of commitment (B = 12.30, p = .068), but not for illusion of control (B = .14, p = .524) as dependent variable. While these results are in line with those of the hypotheses testing (social entrepreneurs have higher levels of overconfidence and escalation of commitment but not illusion of control), the authors have to note that none of the models itself is significant (F = 1.121, p = .301; F = 1.218, p = .189; F = 1.329, p = .103).

Finally, this study tested with linear regression models whether being a social entrepreneur and being prone to biases influences the perceptional outcome variables employee growth, venture performance, social impact and lower life satisfaction. This study found some initial (marginally) significant support for social entrepreneurs perceiving to have higher employee growth, but lower venture performance and lower life satisfaction. Illusion of control tends to be positively related to venture performance, but negatively to social impact. Escalation of commitment tends to be positively related to venture performance and positively to life satisfaction. While these initial results require further studies, the authors can carefully conclude that there might be a tendency that the higher social entrepreneurial biases can lead to more optimistic (‘blinded’) outcome perceptions. Detailed results of the robustness tests are available from the authors.