Abstract

This large-scale statistical study tests the validity of two factors that explain why social entrepreneurs measure their social impact as addressed by qualitative case based research. For this purpose, data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2015-survey is used to test the significance of the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ dichotomy. Based on the results of a fixed-effects logistic regression analysis, this paper finds validation for both factors. Hence, the empirical setup allows for generalising the findings to a broader scope. Regarding ‘measuring to prove’, this paper finds that social entrepreneurs who receive funding from the government are more likely to measure their social impact compared to receiving funds from other sources. Regarding ‘measuring to improve’, this paper finds that social impact measurement is more likely among social entrepreneurs who innovate and prioritise their social mission. In addition, the ‘measuring to improve’ factor seems to be a stronger predictor for measuring social impact than the ‘measuring to prove’ factor. This paper may guide the actions of funders , policy makers and scholars who are engaged in the field of social entrepreneurship, generally, and social impact measurement, specifically.

Introduction

Amplified by an increased attention towards the welfare or well-being in communities, the range of social entrepreneurship includes different organisational forms in which individual or groups of social entrepreneurs aim to enhance the quality of life around the world (Peredo and McLean Citation2006; Zahra et al. Citation2008).Footnote1 These social entrepreneurs are ‘one species in the genus of [the] entrepreneur’ (Dees Citation1998, 2) and part of their legitimacy consists of addressing unmet social needs (cf. Dart Citation2004). Setting aside all good intentions, some scholars warn for an over-optimistic expectation of the impact generated by social entrepreneurs (e.g., Bacq, Hartog, and Hoogendoorn Citation2016; Andersson and Ford Citation2015). Hence, an emerging theme in social entrepreneurship research is social impact measurement (Arvidson et al. Citation2013; Nicholls Citation2009) and of particular interest is whether social entrepreneurs ‘walk their talk’ (Grieco Citation2018, Maas and Grieco Citation2017).

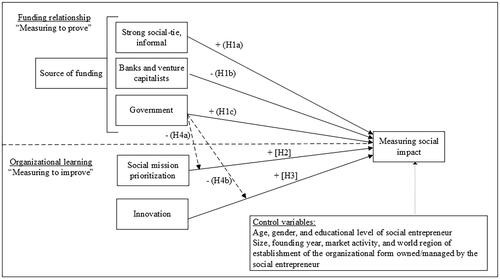

Qualititave and case-study research show the significance of the dichotomy between two important factors for social impact measurment by social entrepreneurs. First, there is an externally driven motivation for social entrepreneurs to demonstrate their legitimacy to key stakeholders, such as funders (Lall Citation2019). This ‘measuring to prove’ factor has close connections with the accountability literature on social entrepreneurship (Nicholls Citation2009; Ebrahim Citation2003; Citation2005; Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair Citation2014). However, the heterogeneity in funding resources available to social entrepreneurs may affect them differently in whether, how and what they are held accountable for (Smith and Stevens Citation2010; Lall Citation2019). Nevertheless, some scholars argue that too much accountability can hinder social entrepreneurs in achieving their social mission (Ebrahim Citation2005; Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair Citation2014). Second, social entrepreneurs may be motivated to evaluate their organisational practices as a way of ‘measuring to improve’ (Campbell, Lambright, and Bronstein Citation2012; Lall Citation2017), i.e. to establish a learning cycle within the organisation. Contrary to the ‘measuring to prove’ factor, the ‘measuring to improve’ factor addresses an internal motivation of social entrepreneurs for keeping track of achieving their social mission (Ormiston Citation2019; Nicholls Citation2009; Lall Citation2017).

While some exceptions in the scholarly quantitative research on social impact exist (see Lall Citation2017; Maas and Grieco Citation2017), the current knowledge is mainly based on qualitative case-study research (see for example Lall Citation2019; Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011; Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015; Chmelik, Musteen, and Ahsan Citation2016; Grimes Citation2010; Fowler, Coffey, and Dixon-Fowler Citation2019; Carman and Fredericks Citation2010; Barraket and Yousefpour Citation2013). Other approaches have led to valuable insights into conceptualizations of social impact (Rawhouser, Cummings, and Newbert Citation2019). Although qualitative research has provided detailed and meaningful insights in what motivates the practice of social impact measurement, it remains largely unanswered whether such findings can be generalised to a broader scope. Subsequently, Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair (Citation2014) called for more research on the factors that relate to the adoption of performance measurement in social enterprises. Therefore, the aim of this paper is to contribute to the field of social entrepreneurship, generally, and social impact measurement, specifically, by extending the limited body of quantitative research. It aims to validate the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors through a large N statistical analysis.Footnote2 As social entrepreneurs may monitor their social mission for multiple reasons at the same time (Nicholls Citation2009), another contribution of this paper lies in the ability to test the two important factors simultaneously by using large-scale survey data from the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor [GEM] 2015 edition. Related to this contribution, this paper is one of the first large-scale quantitative studies that explores to what extent the two most relevant factors for measuring social impact are related to each other. Furthermore, it explores how different sources of funding may affect social impact measurement. Consequently, the research question asks to what extent the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors drive the practice of social impact measurement and to what extent these relate to each other. A fixed-effects logistic regression analysis is used to answer the research question.

The design of the paper is as follows: First, a brief overview of what social impact entails is provided. Second, a theoretical framework regarding social impact measurement related to the ‘proving’ and ‘improving’ factors, as identified by the qualitative academic literature, is introduced. Third, the data and methods that are used for testing the hypotheses are explained. Following the results, the implications of this paper are discussed for practitioners, funders and scholars in the field of social entrepreneurship.

Theoretical Framework

Working Definition on Social Impact and Its Measurement

The significance of social entrepreneurial activity relates to enriching human existence around the globe (Zahra et al. Citation2008) as social entrepreneurs provide services or goods with or for their target population in a variety of industries (Saebi, Foss, and Linder Citation2019). Hence, the mission of social entrepreneurs relates to creating social impact. The related beneficial consequences are specifically enjoyed by the recipients of the activity or broadly by society and the environment (Stephan et al. Citation2016). Examples of social impact may include: successfully alleviating poverty with work integration activities (Chan, Ryan, and Quarter Citation2017); providing citizens in remote rural areas access to electricity by installing solar panels (Becker, Kunze, and Vancea Citation2017); empowering women with martial arts training (Hayhurst Citation2014); enhancing people’s life-satisfaction (Sarracino and Fumarco Citation2020).Footnote3 In general, it can be said that social entrepreneurs contribute to the accomplishment of the Sustainable Development Goals (Rahdari, Sepasi, and Moradi Citation2016) because they are engaged in providing food, water, shelter, education, and medical services to those in need where markets and institutions fail (Certo and Miller Citation2008; Mair and Marti Citation2009). In line with Stephan et al. (Citation2016), in this paper social impact is defined as the social value generated by social entrepreneurs that are enjoyed by either their target group or by society or the environment in a broad sense.Footnote4 While this definition is considered rather inclusive, it captures important dimensions of the practice as identified by the literature (Rawhouser, Cummings, and Newbert Citation2019). Measuring social impact may relate to the effort to monitor the achievement of either an individual program or its overall mission and goals (Rawhouser, Cummings, and Newbert Citation2019; Campbell, Lambright, and Bronstein Citation2012). Similar in that it captures the progress of achieving social goals, other scholars use the term ‘social performance measurement’ to encompass the broad range of these practices. These may include impact evaluation, outcome measurement, and program monitoring (Lall Citation2017; Ebrahim and Rangan Citation2014; Nicholls Citation2009). This paper uses a broad definition of social impact measurement as it refers to any activity performed by social entrepreneurs to monitor any progress of achieving their social mission.

Measuring Social Impact to Prove

The process of monitoring the accomplishment of the organisational goals is important for social entrepreneurs as a way to prove their value to a variety of stakeholders, including their beneficiaries and financial funders (Nicholls Citation2009; Smith and Stevens Citation2010; Austin, Stevenson, and Wei‐Skillern Citation2006; Barraket and Yousefpour Citation2013; Campbell and Lambright Citation2016).Footnote5 The interests of their stakeholders may influence the achievement of their social mission (Ebrahim, Battilana, and Mair Citation2014; Ramus and Vaccaro Citation2017). While impact measurement may be motivated to celebrate the reached achievements together with the beneficiaries they serve (Barraket and Yousefpour Citation2013), it may also be used to satisfy current or attract potential new funders (Ormiston Citation2019; Ormiston et al. Citation2015; Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011). These investments may come from a variety of informal and formal sources and may include donations, grants, volunteers, earned income, and tax breaks (Nicholls Citation2010). Satisfying current funders however fits within the paradigm of ‘measuring to prove’ (Lall Citation2017; Liket and Maas Citation2015; Rawhouser, Cummings, and Newbert Citation2019). For example, there is a need for delivering prove of the effectiveness in achieving the social mission for social entrepreneurs who are being funded by a grant or who work under a government contract (Campbell and Lambright Citation2016; Lall Citation2019). However, the need to measure social impact may depend on the type and primary interest of the financial funder: ‘finance’ or ‘impact’ first (Glänzel and Scheuerle Citation2016). In addition, the social tie between funder and social entrepreneur may influence if and how the social impact is being measured (Smith and Stevens Citation2010).

Social entrepreneurs behave in ways that are regulated by norms and values that are acquired by the socialisation of the environment around them (Brieger et al. Citation2019). This socialisation can be linked to what Smith and Stevens (Citation2010) address as the structural embeddedness of social entrepreneurship. In case of strong social, or embedded ties (Smith and Stevens Citation2010), the relationship between the social entrepreneur and their funder is built upon some form of trust and reciprocity (Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015) that can act as a mechanism that influences their relationship (cf. Uzzi Citation1997; Granovetter Citation1985). Strong social ties are often based on substantial communication and interaction (Uzzi Citation1997; Jack Citation2005). When the social distance between the social entrepreneur and the funder is small – let’s say that they both engage in the same geographical locality – the funder is more likely to see the social impact at first hand or hears from the social entrepreneur as a result of their frequent social interaction (Smith and Stevens Citation2010). This suggests that because of the strong social tie relationship, a social entrepreneur would be more likely to have an incentive to measure their social impact. Moreover, funders from within their social network are likely to affiliate with their social mission (Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015). Therefore, it is expected that social entrepreneurs, who receive funding from their informal network, will be more likely to measure their social impact (H1a).

Next to the assumed effect of informal strong social-ties and following Smith and Stevens (Citation2010) proposition on the ‘arm’s-length ties’ effect on social impact measurement, it is expected that a larger (social) distance between the funder and social entrepreneur leads to more formal pressure to report information on the achievement of the social mission.Footnote6 As embeddedness affects individual motives, behaviours and decision-making (Granovetter Citation1985), the institutions that provide financial resources to social entrepreneurs likely provide an answer on why social entrepreneurs measure their social impact (Nicholls Citation2009). In this paper, it is theorised that funding from formal sources has differential effects and follows a more accountability practice. Formal funders may actually demand impact reports to assess whether their investment contributes to social impact (Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015; Lall Citation2019). However, the practice takes a symbolic role when social entrepreneurs primarily measure to satisfy the needs of their funders (Nicholls Citation2009). In addition, social entrepreneurs who do not value the importance of impact measurement are now likely being pressured to implement the practice (Grieco Citation2018; Nicholls Citation2009; Ebrahim and Rangan Citation2014; Lall Citation2019). This could take a heavy burden on the organisation, as impact measurement is a resource demanding activity (Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011). The social entrepreneur and funder might also prioritise different types of impact to measure (Barraket and Yousefpour Citation2013; Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015). Either way, it is expected that the result is obligatory and therefore a demand from formal funders (Bryson and Buttle Citation2005). Furthermore, formal funders who prioritise the financial returns might require different impact reports than formal funders who sympathise with the social mission of the social enterprise. Related to a focus on the financial returns of investment, banks and venture capital can be an important formal funding source for social entrepreneurs (Bryson and Buttle Citation2005). However, compared to commercial entrepreneurs, social entrepreneurs may face more difficulty to secure traditional banks loans or venture capital because they generate less cash flow (Dees Citation1998). As a way to become more financially attractive to those formal funders, social entrepreneurs may prioritise the financial sustainability because a poor financial performance is more ‘punished’ than a poor social performance (Austin, Stevenson, and Wei‐Skillern Citation2006). Therefore, it is expected that social entrepreneurs who receive funding from formal actors embedded in the financial economy, such as private financial institutions, are less likely to measure their social impact (H1b).

Another type of formal funders, such as social venture capitalists or government institutions, require evidence on social returns as part of their ‘impact first’ investment orientation (Glänzel and Scheuerle Citation2016; Lall Citation2019). Research on how social entrepreneurship relates to institutional configurations shows evidence for an institutional support mechanism. For example, governments may support social entrepreneurs with direct funding such as providing grants and subsidies available to them (Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015; Nicholls Citation2010). Moreover, public sector grants and contracts are a major source of income for social entrepreneurs (Nicholls Citation2010). Therefore, the expectation is that social entrepreneurs who receive funding from formal actors embedded in the public sector, such as the government, are more likely to measure their social impact (H1c). The idea follows the expectation that financially embedded funders are more interested in the financial return on investment, while governments are more likely to be interested in the social return on investment, because they also benefit from the accomplishment of the social mission by social entrepreneurs. However, contrary to H1a, governments’ pressure to monitor the social mission may be based on rule and authority that are part of the ‘arm’s-length’ tie (see Smith and Stevens Citation2010).

Measuring to Improve

Whereas ‘measuring to prove’ is externally motivated, the motivation to measure social impact may depart from the social entrepreneur’s self-interest. For example, a desire to improve upon their own business practices may invoke an internal need (Carman and Fredericks Citation2010; Lall Citation2019). After all, some social impact measurement tools, and particularly the Social Return on Investment, have been developed as a learning and management tool for organisations (Arvidson et al. Citation2013). The ‘measuring to improve’ factor addresses organisational learning as a benefit of evaluation to help improve services (Barraket and Yousefpour Citation2013; Campbell and Lambright Citation2016; Salazar, Husted, and Biehl Citation2012). It is then part of an internal command and control structure that aims for a more efficient and effective way of fulfilling the organisation’s aim (Nicholls and Cho Citation2006; Campbell and Lambright Citation2016). Adding to the (internal) importance of social impact measurement, some scholars argue that it is actually an essential prerequisite of the creation of social impact (Maas and Grieco Citation2017; Liket and Maas Citation2016; Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011).

By relying upon Zahra et al. (Citation2009, 522) definition of social entrepreneurship, two components are likely associated with the ‘measuring to improve’ factor. These are the importance of the social mission and innovation. Additionally, these components are related to each other in that the organisational strategy – i.e. innovation – plays an important role in how the social mission – i.e. the desire to create social impact – is achieved (Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011). As social impact may follow from the achievement of the social mission (Dees Citation1998), scholars used the relative importance of the social and economic mission to identify different organisational forms of social entrepreneurship (see for example Lepoutre et al. Citation2013; Peredo and McLean Citation2006). Moreover, the importance of these missions are reflected in the organisation’s goals, values, and identity (Stevens, Moray, and Bruneel Citation2015). Consequently, social and economic goals of social entrepreneurs are relative to each other and suggest that a higher attention towards the social mission is linked to a lower attention towards the economic mission and vice versa (Stevens, Moray, and Bruneel Citation2015). Subsequently, the prioritisation of the social mission captures the commitment to the social mission (Bosma et al. Citation2016). Accordingly, social entrepreneurs who prioritise their social mission are more likely to measure their social impact (H2).

Another important component is innovation. Social entrepreneurs often rely on an innovative strategy to achieve their social mission (Peredo and McLean Citation2006; Defourny and Nyssens Citation2017; Alvord, Brown, and Letts Citation2004). Moreover, practitioners, scholars and policy-makers argue that innovative social entrepreneurs bring forward the approaches and solutions to pressing social problems (Bosma et al. Citation2016). Social entrepreneurship literature refers to innovation as the creation of new types of organisations or managing existing organisations in an innovative way (Zahra et al. Citation2009). Following the ‘Social Enterprise’ or ‘Earned-Income’ school of thought on social entrepreneurship, the inclusion of an innovative income strategy in support of their mission transformed traditional non-profit organisations in income generating organisational forms of social entrepreneurship (Dees and Anderson Citation2006; Fitzgerald and Shepherd Citation2018; Defourny and Nyssens Citation2010). In addition, the ‘Social Innovation’ school of thought stresses that social entrepreneurs display innovative solutions to address social (or societal) challenges (Dees and Anderson Citation2006; Defourny and Nyssens Citation2010). While innovative strategies have led to new organisational forms of social entrepreneurship, these also include providing new products or services to customers or producing these products or services in a new way (Bosma et al. Citation2016; Lepoutre et al. Citation2013). Research by Maas and Grieco (Citation2017) shows that innovative social entrepreneurs, in particular who provided products or services that were new to the market or produced these in a novel way, were more likely to measure their impact. As innovation is an important component within the domain of social entrepreneurship (Dees and Anderson Citation2006), it is expected that social entrepreneurs, who are innovative in fulfilling their aim, are more likely to measure their social impact (H3).

The Interdependency between ‘Measuring to Prove’ and ‘Measuring to Improve’

While the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors have been identified by mainly qualitative case-study research (e.g. Lall Citation2019, Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011), the quantitative research interest in its interdependency lags behind. Qualitative research studies have shown that social entrepreneurs identify the significance of both factors simultaneously. For example, social impact measurement is driven both by funder demands and by an internal motivation to verify that their organisation is responsive to their clients (Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015; Lall Citation2019). This suggests that an external need to prove and an internal need to improve may simultaneously drive the organisational practice of social impact measurement. Consequently, this begs the question of how these two factors relate to each other. Moreover, it is important to study this relationship because the true essence of value creation lies at the interdependencies of external and internal motivations (Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011). While existing studies focus on only direct effects (see Maas and Grieco Citation2017; Lall Citation2017), this paper aims to contribute to the existing literature on social impact measurement by exploring how the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors influence each other. Evidence for an interdependency between the two factors has been put forward in qualitative work by Ebrahim (Citation2005), who found that a crowding-out effect of funder demands for information likely occurs at the expense of attention to longer-term processes of organisational learning.

As mentioned before, ‘arm’s-length tie’ funders – i.e. the government – may oblige social entrepreneurs to measure social impact as part of authoritarian position as a result of providing funding. Accordingly, formal funders with an interest in ‘impact first’ may require social impact reports rather than formal funders embedded in the private financial sector. Consequently, government funding negatively influences the effect of the relative importance of the social mission (H4a) and innovation (H4b) on social impact measurement. In other words, these moderation hypotheses test whether the significance of the ‘measuring to improve’ factor decreases when social entrepreneurs receive funding from the government. For the visualisation of the hypotheses, see .

Data and Methods

Data

Data from the second global and harmonised assessment of social entrepreneurial activity, the ‘Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Adult Population Survey’ [GEM APS] of 2015, is used for the statistical analysis.Footnote7 The GEM APS 2015 surveyed individuals from more than 50 countries to gain a deeper understanding of their (social) entrepreneurial attitudes, activity and aspirations. The respondents were randomly selected and the questions were asked via face-to-face or telephone interviews (Bosma et al. Citation2016). The sample of this study was restricted to operational social entrepreneurs only, who were identified as individuals who are starting or currently leading any kind of activity, organisation or initiative that has a particularly social, environmental or community objective (Bosma et al. Citation2016). Consequently, the recoding process led to a final sample size of 2525 social entrepreneurs from 36 countries (see Appendix A). shows the descriptive statistics on all variables of interest.

Table 1. Descriptive information on variables of interest (N = 2525).

Dependent Variable: Effort in Measuring Social Impact

Social entrepreneurs may use a variety of tools to monitor the success of their organisation in achieving its social mission (Nicholls Citation2009; Grieco, Michelini, and Iasevoli Citation2015). This quantitative study focuses on whether or not social entrepreneurs use any of these tools. Therefore, the dependent variable was measured with information on statement: ‘My organization puts substantial effort in measuring its social or environmental impact’. The original answer categories range from (1) ‘strongly disagree’ to (5) ‘strongly agree’ with a middle category (3) representing ‘neither disagree nor agree’. The statement identifies whether the focus lies on monitoring the success of the social or environmental mission and not on the financial performance of the organisation. Although the statement refers to social or environmental impact, this paper uses the ‘social impact’ terminology. The dependent variable was rescaled into two categories by creating a dummy code for the combined answer categories (4) ‘agree’ and (5) ‘strongly agree’.Footnote8

Explanatory Variables: Operationalising the ‘Measuring to Prove’ and ‘Measuring to Improve’ Motivations

The explanatory variables measure the relevant set of internal and external factors for social impact measurement as identified before. For testing the generalisability of the ‘measuring to prove’ factor, information on the funding source of the social entrepreneur was used. The GEM APS 2015 asks: ‘Have you (or expect to) received money – loans or ownership investments – from any of the following to start this activity, organization or initiative’. Respondents could select multiple funding options. In accordance with the hypotheses, three non-mutually exclusive membership dummies were created. First, for ‘informal source’, the categories ‘friends or neighbors’, ‘family members’, and ‘employer or work colleagues’ were combined because these typically refer to stronger social ties. Second, for ‘formal financial source’, the categories ‘banks or other financial institutions’ and ‘private investors or venture capital’ were combined. Third, a dummy variable was created for ‘government source’ and measures whether funding was received from ‘government programs, donations or grants’. Social entrepreneurs who did not receive any funding were assigned a 0 on the three funding variables. Conversely, social entrepreneurs who received funding from all sources were assigned a 1 on the three funding variables.

For testing the generalisability of the ‘measuring to improve’ motivation, information on the importance of the social mission and innovativeness of the social entrepreneur were used. The former is measured with information on the statement: ‘For my organization, generating value to society and the environment is more important than generating financial value for the company’. Hence, this captures the commitment to the social mission (Bosma et al. Citation2016). The latter is measured with information on ‘My organization offers products or services that are new to the market’ and ‘My organization offers a new way of producing a product or service’. These are valid indicators of social entrepreneurs’ level of innovation (see Lepoutre et al. Citation2013). The answer categories of the three above mentioned items range from (1) ‘strongly disagree’ to (5) ‘strongly agree’. In line with the hypotheses, the corresponding variables were dichotomised by creating a dummy for the combined answer categories (4) ‘agree’ and (5) ‘strongly agree’. With regard to the measurement of innovation, the two binary innovation items were summed up which resulted in a scale ranging from 0 to 2.Footnote9 All variables in the analysis are measured form the perspective of the social entrepreneur. displays the Pearson bi-variate correlation coefficients between the variables of interest.

Table 2. Bivariate correlations between the variables of interest (N = 2525).

Control Variables

To control for possible confounding factors, essential variables were introduced in the model that are linked to social impact measurement by the literature (see for example Maas and Grieco Citation2017; Lall Citation2017). As such, the world region in which the social entrepreneur operates was controlled because context may affect the practice of measuring social impact (Smith and Stevens Citation2010).Footnote10 In addition, the size (sum of employees and owners in the organisation), age (year in which the organisation was found) and market activity (whether the organisation operates in the market by producing goods and services) of the organisation they own or manage were controlled for. Other control variables include the socio-demographic characteristics of the social entrepreneur, such as age in years (16–65), educational level (lower, middle, higher), and gender (man or woman) as these are related to social entrepreneurship in general (see for example Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015; Brieger et al. Citation2021).

Methods

This paper aims to generalise the qualitative case-based research findings on social impact measurement to a broader scope. Given the focus on the question whether social entrepreneurs measure their social impact because of either or both funder demands and internal motivations, a fixed-effects logistic regression is used. This method allows predicting membership in the target group (measuring social impact) from scores on the explanatory variables. In other words, this statistical test provides the likelihood for social entrepreneurs to measure social impact as a result of the explanatory variables. Moreover, the GEM 2015 report advises to derive patterns to see how different groups of countries can be characterised in terms of social entrepreneurship (Bosma et al. Citation2016). Although it is possible to compare data across countries, ‘the act of social entrepreneurship is still a rare phenomenon, therefore, the results can have a relatively large level of statistical uncertainty’ (Bosma et al. Citation2016, 9). In addition, while respondents in the sample nest within countries, there is only a small number of respondents in some of the countries (see Appendix A). The fixed-effects logistic regression can overcome this statistical limitation by controlling for the international region of establishment (see also Maas and Grieco Citation2017). The logistic regression tables ( and ) display logit coefficients which are linearly related to the scores on the quantitative predictor variables (Pampel Citation2000).Footnote11 Therefore, positive logit coefficients indicate a positive effect and negative logit coefficients indicate a negative effect on the dependent variable.

Results

presents the results of the fixed-effects logistic regression on whether or not social entrepreneurs measure their social impact. The constant-only model (Model 0) shows a logit coefficient of .612 with a −2 log likelihood [LL] of 3277.47 for the base-line model fit. The corresponding odds ratio is 1.84, implying that the probability of a social entrepreneur to measure social impact is 65% on average. Throughout all models, there is an observed increased model fit due to a reduction in the −2 LL and an increase in the explained variance.Footnote12 This implies that the models with the included covariates have a better fit compared to the previous more parsimonious models.

Table 3. Logistic regression on social impact measurement by social entrepreneurs (N = 2525, logit coefficients).

Measuring to Prove and Measuring to Improve

shows the results for testing hypotheses 1a–1c. Model 1 shows the results of the control variables. Model 2 and 6 include additional information on the effect of funding on measuring social impact by social entrepreneurs. While receiving funding from government sources significantly affects the dependent variable, informal and formal financial funding sources are not statistically significant predictors in both Model 2 and 6. As the ‘measuring to improve’ variables are also included in Model 6, a slight decrease in the effect of receiving government funding can be observed. However, the effect of government funding remains significant (b = .354, p < .01). Based on these results, hypothesis 1c is accepted and hypotheses 1a and 1 b are rejected. In addition, adding the different funding sources in Model 2 leads to an increase of .94% point in the explained variance compared to Model 1.

The variables related to the ‘measuring to improve’ factor are included in Models 3–6. Subsequently, these variables appear to be a stronger predictor of the dependent variable compared to the ‘measuring to prove’ variables. Moreover, they explain an additional 10.85% point compared to Model 1. This implies that organisational learning, as a likely motivation for measuring social impact, is a stronger predictor than receiving funding. Model 6 shows that social entrepreneurs who prioritise their social mission are more likely to measure their social impact than social entrepreneurs for whom the financial performance is just as or even more important (b = 1.241, p < .001). Furthermore, social entrepreneurs who sell a new product or service on the market and/or produce these in a new way were more likely to measure their social impact (b = .727, p < .001). Aligning the social mission with an innovative strategy appears to be highly associated with measuring social impact across the sample. Consequently, hypotheses 2 and 3 are accepted.

Moderating Effect of ‘Measuring to Prove’ on ‘Measuring to Improve’

shows three logistic regression models that include the moderation effects to test hypotheses 4a and 4b.Footnote13 The effect of prioritising the social mission on measuring social impact is weaker among those social entrepreneurs who also receive government funding (see Model 7). In addition, the absolute level of innovation becomes a weaker predictor (see Model 8). Including both moderators at the same time as displayed in Model 9, the moderation effects cannot be generalised to the population, as the results are not significant at the p-level of .05. In sum, the results of the moderation analyses show that government funding ‘crowds-out’ the importance of the ‘measuring to improve’ motivation. However, the results are not statistically significant and therefore hypotheses 4a and 4b are rejected.

Table 4. Moderation test of ‘measuring to improve’ on ‘measuring to prove’ (N = 2525, logit coefficients).

The results of the analyses suggest that a systematic difference between the likelihood of measuring social impact between social mission prioritising and innovative social entrepreneurs exists. This is in line with the ‘measuring to improve’ motivation. In addition, accountability does not appear to all funding sources. Evidence for the ‘measuring to prove’ motivation was found for social entrepreneurs who receive funding from the government. Furthermore, by statistically controlling for all other variables, no significant statistical evidence was found that receiving government funding influences the strength of the ‘measuring to improve’ motivation in predicting social impact measurement. Taking into account both motivations, as addressed in Model 6 of , the variance in social impact measurement is partly explained with 16.58%.

Conclusion and Implications

Key Findings

The research question of this paper asked how and to what extent different factors motivate social entrepreneurs to measure social impact. This paper reveals that a substantial proportion of social entrepreneurs (about 65%) put effort in measuring their social impact in any way.Footnote15 By means of a large N statistical analysis, the findings of this paper contribute to the field of social entrepreneurship, generally, and social impact measurement, specifically.

From the eyes of the beholders – the social entrepreneurs – social impact measurement is motivated by both funding obligations and organisational learning. This corresponds with the transdisciplinary aspect of the practice as it involves elements of both accountability and organisational strategy (Ormiston Citation2019). As social entrepreneurship is structurally embedded (Smith and Stevens Citation2010), this research has differentiated between the likely sources of funding. No evidence was found that social entrepreneurs are more likely to measure their social impact when they receive funding from within their informal network. This is probably because the informal network funders trust the social entrepreneur to ‘do good' and formal evaluation would not be necessary (Smith and Stevens Citation2010; Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015). Furthermore, whereas funders who are embedded in the financial sector do not significantly affect social entrepreneurs, social entrepreneurs are more likely to measure their social impact if they receive funding from publicly embedded actors. It may be that governments base their funding upon rule and authority and hence require social entrepreneurs to provide information on their achieved social mission in a formal way. Direct government investments stimulate the social enterprise sector by providing access to financial resources and networks (Fowler, Coffey, and Dixon-Fowler Citation2019). It further facilitates an increased social orientation of entrepreneurs (Brieger et al. Citation2019). Consequently, measuring to prove social impact may hold only for institutions embedded in the public domain.

Concerning this paper’s findings related to the ‘measuring to improve’ motivation, social impact is more likely to occur when social entrepreneurs prioritise the social mission relative to their financial performance and when they are more innovative with regard to their products or services. This also suggests that a ‘warm glow’ of social entrepreneurship (see Bacq, Hartog, and Hoogendoorn Citation2016; Maas and Grieco Citation2017), where there is no formal need for impact verification, is not present among this paper’s sample of social entrepreneurs who operate in various regions in the world. Rather, social entrepreneurs seem to do ‘walk their talk’ as they put substantial effort in measuring their social impact. Moreover, taking into account both the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ motivations likely captures a more complete view of different factors behind measuring social impact. While funder demands may cause a decreased attention towards the social mission (Ebrahim Citation2005), this paper did not find a significant interplay between the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors.

Limitations

A number of limitations also mark this paper, which have to be discussed. Related to measurement concerns, the understanding of social entrepreneurship may vary between different contexts (Mair Citation2010). Therefore, it is important to note the geographical dispersion of the respondents in this study. However, the GEM data provides a valid assessment of global social entrepreneurial activity (Bosma et al. Citation2016). Moreover, there is a widespread consensus about the meaning of social entrepreneurship within the academic community (Alegre, Kislenko, and Berbegal-Mirabent Citation2017). Related to methodological concerns, this cross-sectional study cannot detect causal mechanisms and may cause concerns about the one-directional hypotheses. Furthermore, this paper focussed on two significant motivations for measuring social impact, while social entrepreneurs may be motivated by other concerns. For example, social impact reports can be used to attract funding or encourage morale among stakeholders, staff and volunteers (e.g. Barraket and Yoesefpour Citation2013; Ormiston Citation2019). Important to note is that the values and philosophies of social entrepreneurs may guide them in identifying and selecting appropriate funders (Onishi et al. Citation2018; Pandey et al. Citation2017). Another component that may influence the main motivation for social impact measurement is the stage of the relationship between funder and social entrepreneur (see Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015; Lall Citation2019). However, in line with the literature on social impact measurement and regardless of the between country variation, the results show that widely used tools serve the ‘measuring to improve’ (Arvidson et al. Citation2013; Nicholls and Cho Citation2006; Campbell and Lambright Citation2016) and ‘measuring to prove’ need (see Nicholls Citation2009) across the world.

Several other data restrictions prevent a more in-depth study of social impact measurement and the influence of the significant motivations. While there are numerous social impact measurement tools (see Grieco, Michelini, and Iasevoli Citation2015), it could not be assessed how these specifically influence the resources, time and effort needed for social entrepreneurs to use. In addition, the type of social relationship between the social entrepreneur and funder in terms of assumed strong or weak social ties could only be gauged. Social capital literature on social ties usually takes the frequency of social contact to indicate the type of social tie (e.g. Vervoort Citation2012). Furthermore, the actual formal requirements of receiving government funding – other than that the social entrepreneur indicated they received it – could not be assessed. Specific formal obligations or agreements between social entrepreneur and funder could influence what type of impact should be measured and how this should be done. Despite these limitations, the results of this research can be used as a starting point for future research.

Implications

Case based research and theory show the relevance of the dichotomy between ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors. The large N statistical test applied in this study provides evidence for the theoretical assumptions and shows that the qualitative case based findings can be generalised to a broader scope. Therefore, the results may provide valuable insights for social entrepreneurship scholars and funders related to social entrepreneurs.

With regard to social entrepreneurship scholars, the analyses show that, ceteris paribus, both the ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors influence the effort placed in measuring social impact. This paper extends the current knowledge by studying whether social entrepreneurs measure their social impact around the world using the unique, large-scale and cross-national GEM 2015 survey data. This GEM version includes information on the effort social entrepreneurs take to measure the social or environmental impact. Hence, the interest lies in the non-economic impact, rather than any impact along social, environmental or economic objectives as assessed in the GEM 2009 version.Footnote14 Although exceptions exist (see Maas and Grieco Citation2017; Lall Citation2017), the majority of empirical research on this topic is based on small sample case studies, often restricted to one or two different contexts (e.g.Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011; Ormiston Citation2019; Phillips and Johnson Citation2021). While the qualitative work of scholars have also revealed the significance of both factors (see Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015; Lall Citation2019), the contribution of this quantitative study is that such findings can be generalised to a broader scope. However, it appears that accountability by measuring social impact is different towards different type of funders. The results show that measuring social impact is an organisational practice that is primarily motivated to improve services and operations. In addition, the organisational practice of impact measurement is not socially but rather institutionally embedded in the public domain.

The findings of this paper may encourage a dialogue between stakeholders, i.e. between social entrepreneurs and their funders. Concerning policy makers and grant providers, social entrepreneurs tend to measure social impact when dependent upon government funding. However, governmental funders should also acknowledge the relevance of organisational learning as a motivation as this is beneficial to the organisational effectiveness and hence the social impact reached. As the latter is a shared goal for governments and social entrepreneurs, governments could play an additional stimulus in achieving social impact (Lall Citation2019; Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015). Concerning banks and venture capitalists, it appears that their funding does not influence social entrepreneurs’ effort to measure the non-financial impact. In relation to contributing to the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals, these funding agencies could also include some need for social impact monitoring from their investees. These funding agencies have the potential to make a difference with their amount of invested capital. Instead of emphasising a financial return on investment, banks could include clauses in their investment deals that refer to social impact. The challenge for funders after all lies in encouraging social entrepreneurs to recognise and learn from success as well as from failure (Ebrahim Citation2005).

In response to the findings and limitations of this paper, future research could focus on a feedback-loop mechanism in which social impact measurement could be used to obtain funding which in turn enhances organisational practice (see Ormiston and Seymour Citation2011). In addition, concerning social entrepreneurs’ contractual obligations towards funders, an interesting research avenue is to focus on how institutions – i.e. local governments or welfare state institutions in general – develop partnerships with social entrepreneurs to deliver social services (see Stephan, Uhlaner, and Stride Citation2015). Furthermore, future research might focus on power (dis)balances between funders and social entrepreneurs and how this influences the uptake of measurement tools as either an onbligation or a way to achieve the goals of both actors. In line with suggestions made by Rawhouser, Cummings, and Newbert (Citation2019), new data collection procedures are needed to design cross-sectional and quantitative panel data that can advance the field of social entrepreneurship and social impact research. As such, the antecedents, intricacies, and consequences of social impact measurement practices can be studied over time. Despite the possible shortcomings, this paper has provided a useful step in understanding the relevance of the significant ‘measuring to prove’ and ‘measuring to improve’ factors. Furthermore, this paper has provided a theoretical and empirical focus that might help to study the role of funders to enhance theorising about social entrepreneurship.

Acknowledgment

An earlier version of this paper has been presented at the 17th Annual Social Entrepreneurship Conference (Nov. 5, 2020) and Cultural Sociology Lowlands (Nov. 6, 2020). The authors thank the conference’s audience and assigned paper reviewers, and two anonymous reviewers of the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship for their helpful comments in constructing the final version of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 A broad view on social entrepreneurship includes organisational forms with an explicit or at least in some prominent way included social goal (Peredo and McLean Citation2006). Whereas social entrepreneurship refers to the activity social entrepreneurs are involved in, social enterprises refer to the organisational forms of social entrepreneurship (Defourny and Nyssens Citation2010, Citation2017).

2 This paper does not aim to examine the quality or activity of social impact measurement by social entrepreneurs, only whether these entrepreneurs report that they put substantial effort in measuring social impact.

3 It is important to acknowledge the diversity and extensive range of social entrepreneurship and its impact. The examples included do not show the full extent of impact generated on all fields.

4 Impact measurement in this sense does not differentiate between levels of impact nor by short-term or long-term effects.

5 These are also called ‘principal stakeholders’ (Freeman Citation2010).

6 Others speak of ‘asymmetric ties’ (see Nguyen, Szkudlarek, and Seymour Citation2015; Nicholls Citation2009).

7 The GEM 2015-survey uses a self-identification measure to assess social entrepreneurship. This measure is not without critique, as it might not measure ‘social entrepreneurship’ but rather any active involvement in addressing social or environmental needs (Bacq, Hartog, and Hoogendoorn Citation2013). Only respondents self-identifying as a social entrepreneur were asked the question to what extent they measure the social or environmental impact of their organisation. The GEM APS 2015 dataset was obtained from https://www.gemconsortium.org/data/sets?id=aps.

8 This recoding process is similar to the presentation of GEM 2015 data as shown in the international GEM 2015 report on social entrepreneurship (Bosma et al. Citation2016).

9 A 0 means that the social entrepreneur did not affirm to being innovative, a 1 means that the social entrepreneur affirmed to on one item, a 2 means that the social entrepreneur affirmed to the two items.

10 Based on the recognition that social impact measurement may vary across countries, a robustness test was performed by adding a dummy for each country or for the type of economy (factor-, efficiency-, and innovation-driven, see for example Lall (Citation2017)). However, these approaches yield the same conclusion as by including the world-region dummies. As this paper does not include hypotheses on contextual effects, the current statistical method should be appropriate.

11 The probability of measuring social impact by social entrepreneurs can be calculated based on the scores of the quantitative predictor variables. After transforming the logit coefficients to odds ratios by de-logarithmizing the logit coefficient (exp(logit)), apply the following equation: odds/(1 + odds) (see Warner Citation2012; Pampel Citation2000).

12 STATA version 16 package was used to analyse the data. STATA provides the McFadden R-square as its default pseudo R-square for logistic regression.

13 Because of the moderators included in , the coefficients of the logistic regression models cannot be interpreted as direct effects. For direct effect estimates, see .

14 Maas and Grieco (Citation2017) used GEM 2009 data and measured their dependent variable of ‘impact measurement’ with the item: ‘Are you indeed measuring or planning to measure the impact along these three categories?’. The three categories include financial, social and environmental objectives. This item does not differentiate between financial and non-financial impact measurement.

15 In contrast to other scholars who state that social entrepreneurs have a low implementation of social impact assessment (e.g. Phillips and Johnson Citation2021) this paper found a substantial high proportion of social entrepreneurs – particularly who fit within the ‘narrow’ definition of social entrepreneurship (Bosma et al. Citation2016) – engaged in social impact measurement across various world regions.

References

- Alegre, I., S. Kislenko, and J. Berbegal-Mirabent. 2017. “Organized Chaos: Mapping the Definitions of Social Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8 (2): 248–264. doi:10.1080/19420676.2017.1371631.

- Alvord, S. H., L. D. Brown, and C. W. Letts. 2004. “Social Entrepreneurship and Societal Transformation: An Exploratory Study.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 40 (3): 260–282. doi:10.1177/0021886304266847.

- Andersson, F. O., and M. Ford. 2015. “Reframing Social Entrepreneurship Impact: Productive, Unproductive and Destructive Outputs and Outcomes of the Milwaukee School Voucher Programme.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 6 (3): 299–319. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.981845.

- Arvidson, Malin, Fergus Lyon, Stephen McKay, and Domenico Moro. 2013. “Valuing the Social? The Nature and Controversies of Measuring Social Return on Investment (SROI).” Voluntary Sector Review 4 (1): 3–18. doi:10.1332/204080513X661554.

- Austin, J., H. Stevenson, and J. Wei‐Skillern. 2006. “Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Same, Different, or Both?” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 30 (1): 1–22. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2006.00107.x.

- Bacq, S., C. Hartog, and B. Hoogendoorn. 2013. “A Quantitative Comparison of Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Toward a More Nuanced Understanding of Social Entrepreneurship Organizations in Context.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 4 (1): 40–68. doi:10.1080/19420676.2012.758653.

- Bacq, S., C. Hartog, and B. Hoogendoorn. 2016. “Beyond the Moral Portrayal of Social Entrepreneurs: An Empirical Approach to Who They Are and What Drives Them.” Journal of Business Ethics 133 (4): 703–718. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2446-7.

- Barraket, J., and N. Yousefpour. 2013. “Evaluation and Social Impact Measurement Amongst Small to Medium Social Enterprises: Process, Purpose and Value.” Australian Journal of Public Administration 72 (4): 447–458. doi:10.1111/1467-8500.12042.

- Becker, S., C. Kunze, and M. Vancea. 2017. “Community Energy and Social Entrepreneurship: Addressing Purpose, Organisation and Embeddedness of Renewable Energy Projects.” Journal of Cleaner Production 147: 25–36. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2017.01.048.

- Bosma, N., T. Schøtt, S. A. Terjesen, and P. Kew. 2016. “Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2015 to 2016: Special topic report on social entrepreneurship.” https://www.gemconsortium.org/report/gem-2015-report-on-social-entrepreneurship

- Brieger, S. A., A. Bäro, G. Criaco, and S. A. Terjesen. 2021. “Entrepreneurs’ Age, Institutions, and Social Value Creation Goals: A Multi-Country Study.” Small Business Economics 57 (1): 425–453. doi:10.1007/s11187-020-00317-z.

- Brieger, Steven A., Siri A. Terjesen, Diana M. Hechavarría, and Christian Welzel. 2019. “Prosociality in Business: A Human Empowerment Framework.” Journal of Business Ethics 159 (2): 361–380. 1-20. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-4045-5.

- Bryson, J. R., and M. Buttle. 2005. “Enabling Inclusion through Alternative Discursive Formations: The Regional Development of Community Development Loan Funds in the United Kingdom.” The Service Industries Journal 25 (2): 273–288. doi:10.1080/0264206042000305457.

- Campbell, D. A., and K. T. Lambright. 2016. “Program Performance and Multiple Constituency Theory.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 45 (1): 150–171. doi:10.1177/0899764014564578.

- Campbell, D. A., K. T. Lambright, and L. R. Bronstein. 2012. “In the Eyes of the Beholders: Feedback Motivations and Practices among Nonprofit Providers and Their Funders.” Public Performance & Management Review 36 (1): 7–30. doi:10.2753/PMR1530-9576360101.

- Carman, J. G., and K. A. Fredericks. 2010. “Evaluation Capacity and Nonprofit Organizations: Is the Glass Half-Empty or Half-Full?” American Journal of Evaluation 31 (1): 84–104. doi:10.1177/1098214009352361.

- Certo, S. T., and T. Miller. 2008. “Social Entrepreneurship: Key Issues and Concepts.” Business Horizons 51 (4): 267–271. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2008.02.009.

- Chan, A., S. Ryan, and J. Quarter. 2017. “Supported Social Enterprise: A Modified Social Welfare Organization.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 46 (2): 261–279. doi:10.1177/0899764016655620.

- Chmelik, E., M. Musteen, and M. Ahsan. 2016. “Measures of Performance in the Context of International Social Ventures: An Exploratory Study.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 7 (1): 74–100. doi:10.1080/19420676.2014.997781.

- Dart, R. 2004. “The Legitimacy of Social Enterprise.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 14 (4): 411–424. doi:10.1002/nml.43.

- Dees, J. G. 1998. The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. Kansas City, MO: Kauffman Center for Entrepreneurial Leadership.

- Dees, J. G., and B. B. Anderson. 2006. “Framing a Theory of Social Entrepreneurship: building on Two Schools of Practice and Thought.” Research on Social Entrepreneurship. ARNOVA Occasional Paper Series 1 (3): 39–66.

- Defourny, J., and M. Nyssens. 2010. “Conceptions of Social Enterprise and Social Entrepreneurship in Europe and the United States: Convergences and Divergences.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1 (1): 32–53. doi:10.1080/19420670903442053.

- Defourny, J., and M. Nyssens. 2017. “Fundamentals for an International Typology of Social Enterprise Models.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28 (6): 2469–2497. doi:10.1007/s11266-017-9884-7.

- Ebrahim, A. 2003. “Accountability in Practice: Mechanisms for NGOs.” World Development 31 (5): 813–829. doi:10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00014-7.

- Ebrahim, A. 2005. “Accountability Myopia: Losing Sight of Organizational Learning.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 34 (1): 56–87. doi:10.1177/0899764004269430.

- Ebrahim, A., J. Battilana, and J. Mair. 2014. “The Governance of Social Enterprises: Mission Drift and Accountability Challenges in Hybrid Organizations.” Research in Organizational Behavior 34: 81–100. doi:10.1016/j.riob.2014.09.001.

- Ebrahim, A., and V. K. Rangan. 2014. “What Impact? A Framework for Measuring the Scale and Scope of Social Performance.” California Management Review 56 (3): 118–141. doi:10.1525/cmr.2014.56.3.118.

- Fitzgerald, T., and D. Shepherd. 2018. “Emerging Structures for Social Enterprises within Nonprofits: An Institutional Logics Perspective.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 47 (3): 474–492. doi:10.1177/0899764018757024.

- Fowler, E. A., B. S. Coffey, and H. R. Dixon-Fowler. 2019. “Transforming Good Intentions into Social Impact: A Case on the Creation and Evolution of a Social Enterprise.” Journal of Business Ethics 159 (3): 665–678. doi:10.1007/s10551-017-3754-5.

- Freeman, R. E. 2010. Strategic Management: A Stakeholder Approach. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Glänzel, G., and T. Scheuerle. 2016. “Social Impact Investing in Germany: Current Impediments from Investors’ and Social Entrepreneurs’ Perspectives.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 27 (4): 1638–1668. doi:10.1007/s11266-015-9621-z.

- Granovetter, M. 1985. “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness.” American Journal of Sociology 91 (3): 481–510. doi:10.1086/228311.

- Grieco, C. 2018. “What Do Social Entrepreneurs Need to Walk Their Talk? Understanding the Attitude–Behavior Gap in Social Impact Assessment Practice.” Nonprofit Management and Leadership 29 (1): 105–122. doi:10.1002/nml.21310.

- Grieco, C., L. Michelini, and G. Iasevoli. 2015. “Measuring Value Creation in Social Enterprises: A Cluster Analysis of Social Impact Assessment Models.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 44 (6): 1173–1193. doi:10.1177/0899764014555986.

- Grimes, M. 2010. “Strategic Sensemaking within Funding Relationships: The Effects of Performance Measurement on Organizational Identity in the Social Sector.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 34 (4): 763–783. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6520.2010.00398.x.

- Hayhurst, L. M. C. 2014. “The ‘Girl Effect’ and Martial Arts: Social Entrepreneurship and Sport, Gender and Development in Uganda.” Gender, Place & Culture 21 (3): 297–315. doi:10.1080/0966369X.2013.802674.

- Jack, S. L. 2005. “The Role, Use and Activation of Strong and Weak Network Ties: A Qualitative Analysis.” Journal of Management Studies 42 (6): 1233–1259. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6486.2005.00540.x.

- Lall, S. 2017. “Measuring to Improve versus Measuring to Prove: Understanding the Adoption of Social Performance Measurement Practices in Nascent Social Enterprises.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 28 (6): 2633–2657. doi:10.1007/s11266-017-9898-1.

- Lall, S. 2019. “From Legitimacy to Learning: How Impact Measurement Perceptions and Practices Evolve in Social Enterprise–Social Finance Organization Relationships.” VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations 30 (3): 562–577. doi:10.1007/s11266-018-00081-5.

- Lepoutre, Jan, Rachida Justo, Siri Terjesen, and Niels Bosma. 2013. “Designing a Global Standardized Methodology for Measuring Social Entrepreneurship Activity: The Global Entrepreneurship Monitor Social Entrepreneurship Study.” Small Business Economics 40 (3): 693–714. doi:10.1007/s11187-011-9398-4.

- Liket, K., and K. Maas. 2016. “Strategic Philanthropy: Corporate Measurement of Philanthropic Impacts as a Requirement for a “Happy Marriage” of Business and Society.” Business & Society 55 (6): 889–921. doi:10.1177/0007650314565356.

- Liket, K. C., and K. Maas. 2015. “Nonprofit Organizational Effectiveness: Analysis of Best Practices.” Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 44 (2): 268–296. doi:10.1177/0899764013510064.

- Maas, K., and C. Grieco. 2017. “Distinguishing Game Changers from Boastful Charlatans: Which Social Enterprises Measure Their Impact?” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8 (1): 110–128. doi:10.1080/19420676.2017.1304435.

- Mair, J. 2010. “Social Entrepreneurship: Tacking Stock and Looking Ahead.” In Handbook of Research on Social Entrepreneurship, edited by A. Fayolle and H. Matlay, 15–28. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Mair, J., and I. Marti. 2009. “Entrepreneurship in and around Institutional Voids: A Case Study from Bangladesh.” Journal of Business Venturing 24 (5): 419–435. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.006.

- Nguyen, L., B. Szkudlarek, and R. G. Seymour. 2015. “Social Impact Measurement in Social Enterprises: An Interdependence Perspective.” Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences de L'Administration 32 (4): 224–237. doi:10.1002/cjas.1359.

- Nicholls, A. 2009. “We Do Good Things, Don’t We?’: ‘Blended Value Accounting’ in Social Entrepreneurship.” Accounting, Organizations and Society 34 (6–7): 755–769. doi:10.1016/j.aos.2009.04.008.

- Nicholls, A. 2010. “The Institutionalization of Social Investment: The Interplay of Investment Logics and Investor Rationalities.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 1 (1): 70–100. doi:10.1080/19420671003701257.

- Nicholls, A., and A. Cho. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship: The Structuration of a Field.” In Social Entrepreneruship: New Paradigms of Sustainable Social Change, A. Nicholls, 99–118. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Onishi, T., A. C. Burkemper, E. R. Micelotta, and W. J. Wales. 2018. “An Effectual Perspective on How Social Entrepreneurs Select, Combine, and Orchestrate Resources.” Academy of Management Proceedings 2018 (1): 18687–18686. doi:10.5465/AMBPP.2018.2.

- Ormiston, J. 2019. “Blending Practice Worlds: Impact Assessment as a Transdisciplinary Practice.” Business Ethics: A European Review 28 (4): 423–440. doi:10.1111/beer.12230.

- Ormiston, Jarrod, Kylie Charlton, M. Scott Donald, and Richard G. Seymour. 2015. “Overcoming the Challenges of Impact Investing: Insights from Leading Investors.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 6 (3): 352–378. doi:10.1080/19420676.2015.1049285.

- Ormiston, J., and R. Seymour. 2011. “Understanding Value Creation in Social Entrepreneurship: The Importance of Aligning Mission, Strategy and Impact Measurement.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 2 (2): 125–150. doi:10.1080/19420676.2011.606331.

- Pandey, S., S. Lall, S. K. Pandey, and S. Ahlawat. 2017. “The Appeal of Social Accelerators: What Do Social Entreprenurs Value?” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 8 (1): 88–109. doi:10.1080/19420676.2017.1299035.

- Pampel, F. C. 2000. Logistic Regression: A Primer. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Peredo, A. M., and M. McLean. 2006. “Social Entrepreneurship: A Critical Review of the Concept.” Journal of World Business 41 (1): 56–65. doi:10.1016/j.jwb.2005.10.007.

- Phillips, S. D., and B. Johnson. 2021. “Inching to Impact: The Demand Side of Social Impact Investing.” Journal of Business Ethics 168 (3): 615–629. 1-15. doi:10.1007/s10551-019-04241-5.

- Rahdari, A., S. Sepasi, and M. Moradi. 2016. “Achieving Sustainability through Schumpeterian Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Social Enterprises.” Journal of Cleaner Production 137: 347–360. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.159.

- Ramus, T., and A. Vaccaro. 2017. “Stakeholders Matter: How Social Enterprises Address Mission Drift.” Journal of Business Ethics 143 (2): 307–322. doi:10.1007/s10551-014-2353-y.

- Rawhouser, H., M. Cummings, and S. L. Newbert. 2019. “Social Impact Measurement: Current Approaches and Future Directions for Social Entrepreneurship Research.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 43 (1): 82–115. doi:10.1177/1042258717727718.

- Saebi, T., N. J. Foss, and S. Linder. 2019. “Social Entrepreneurship Research: Past Achievements and Future Promises.” Journal of Management 45 (1): 70–95. doi:10.1177/0149206318793196.

- Salazar, J., B. W. Husted, and M. Biehl. 2012. “Thoughts on the Evaluation of Corporate Social Performance through Projects.” Journal of Business Ethics 105 (2): 175–186. doi:10.1007/s10551-011-0957-z.

- Sarracino, F., and L. Fumarco. 2020. “Assessing the Non-Financial Outcomes of Social Enterprises in Luxembourg.” Journal of Business Ethics 165 (3): 425–451. 1-27. doi:10.1007/s10551-018-4086-9.

- Smith, B. R., and C. E. Stevens. 2010. “Different Types of Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Geography and Embeddedness on the Measurement and Scaling of Social Value.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 22 (6): 575–598. doi:10.1080/08985626.2010.488405.

- Stephan, Ute, Malcolm Patterson, Ciara Kelly, and Johanna Mair. 2016. “Organizations Driving Positive Social Change: A Review and an Integrative Framework of Change Processes.” Journal of Management 42 (5): 1250–1281. doi:10.1177/0149206316633268.

- Stephan, U., L. M. Uhlaner, and C. Stride. 2015. “Institutions and Social Entrepreneurship: The Role of Institutional Voids, Institutional Support, and Institutional Configurations.” Journal of International Business Studies 46 (3): 308–331. doi:10.1057/jibs.2014.38.

- Stevens, R., N. Moray, and J. Bruneel. 2015. “The Social and Economic Mission of Social Enterprises: Dimensions, Measurement, Validation, and Relation.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 39 (5): 1051–1082. doi:10.1111/etap.12091.

- Uzzi, B. 1997. “Social Structure and Competition in Interfirm Networks: The Paradox of Embeddedness.” Administrative Science Quarterly 42 (2): 417. 35-67. doi:10.2307/2393808.

- Vervoort, M. 2012. “Ethnic Concentration in the Neighbourhood and Ethnic Minorities’ Social Integration: Weak and Strong Social Ties Examined.” Urban Studies 49 (4): 897–915. doi:10.1177/0042098011408141.

- Warner, R. M. 2012. Applied Statistics: From Bivariate through Multivariate Techniques. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Zahra, Shaker A., Eric Gedajlovic, Donald O. Neubaum, and Joel M. Shulman. 2009. “A Typology of Social Entrepreneurs: Motives, Search Processes and Ethical Challenges.” Journal of Business Venturing 24 (5): 519–532. doi:10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.04.007.

- Zahra, Shaker A., Hans N. Rawhouser, Nachiket Bhawe, Donald O. Neubaum, and James C. Hayton. 2008. “Globalization of Social Entrepreneurship Opportunities.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 2 (2): 117–131. doi:10.1002/sej.43.

Appendix Table A1. Descriptive statistics on variables of interest by country.