Abstract

Social entrepreneurship research has increasingly adopted quantitative methodologies, reflecting the field’s evolution into mainstream academia. However, there remains a noted deficiency in rigorous hypothesis testing. Furthermore, instances abound that conventional entrepreneurship and management research often employ control variables in hypothesis testing without clear theoretical grounding or sufficient justifications, often relying on precedent. This study investigates how social entrepreneurship researchers incorporate and report control variables in their studies. A thorough examination of 78 empirical studies published from 2010 to 2023 in the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship and the Social Enterprise Journal reveals several key insights. The findings indicate that only about 60% of social entrepreneurship research integrates control variables, with a mere 34% providing a justification for their inclusion. Only 22% present a theoretically or empirically substantiated rationale, while a substantial 85% lack any justification for their chosen measurements. Furthermore, over 75% of studies do not specify the anticipated relationship between control and dependent variables. To enhance methodological rigour in social entrepreneurship research, this study provides critical recommendations for both researchers and reviewers through a decision tree. It emphasises the importance of grounding the application of control variables in robust theoretical and empirical foundations, rather than simply following precedent.

Introduction

Social entrepreneurship has emerged as a crucial research area for both firms and scholars (Kannampuzha and Hockerts Citation2019). It has now reached a level of maturity (de Bruin and Teasdale Citation2019; Gupta et al. Citation2020; Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2018) and is acknowledged as a mainstream field (Williams et al. Citation2023). Consequently, recent social entrepreneurship scholarship has seen a shift towards quantitative approaches for theory testing, alongside the dominant qualitative theory-building approaches (Hota, Subramanian, and Narayanamurthy Citation2020). This shift is evident in the increasing accumulation and application of extensive quantitative datasets to study social entrepreneurial phenomena (e.g. Lee et al. Citation2022; Coskun, Monroe-White, and Kerlin Citation2019; Ayob Citation2018; Pandey et al. Citation2017; Bacq, Hartog, and Hoogendoorn Citation2013; Searing et al. Citation2022; Gras and Lumpkin Citation2012; Hechavarría et al. Citation2023), as well as the utilisation of advanced multivariate analytical approaches like regression and structural equation modelling (e.g. Cheah, Loh, and Gunasekaran Citation2023; Kruse et al. Citation2023; Lee and Kelly Citation2019; Gras and Lumpkin Citation2012; Pandey et al. Citation2017).

With the rise of social entrepreneurship phenomena and the adoption of quantitative approach-based research comes a need for a better understanding of the application of quantitative methods. In empirical theory testing, it is crucial to pinpoint and isolate variables that predict the dependent variable while also managing extraneous factors that affect the relationship (Curado et al. Citation2023; Becker Citation2005; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016). Ruling out threats to valid inferences to determine to what extent the independent variables behave as hypothesised becomes a crucial element in empirical research. For this purpose, the widespread approach in nonexperimental research in management and entrepreneurship research is the use of control variables (Bernerth et al. Citation2018; Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018; Schjoedt and Bird Citation2014; Curado et al. Citation2023). While the inclusion of control variables in testing hypotheses is recommended, the application of this practice should follow a rationale and a rigorous approach. Ad-hoc approaches can reduce the statistical power of the model and lead to incorrect findings (Becker Citation2005; Carlson and Wu Citation2012; Kalnins Citation2018).

While numerous valuable articles in management (e.g. Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Becker Citation2005; Becker et al. Citation2016; Carlson and Wu Citation2012), marketing (e.g. Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018), leadership (e.g. Bernerth et al. Citation2018), operations management (e.g. Curado et al. Citation2023), international business (e.g. Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018), and applied psychology (e.g. Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016; Sturman, Sturman, and Sturman Citation2022) research have underscored the flawed application of control variables and provided valuable guidance on correct approaches (e.g. Sturman, Sturman, and Sturman Citation2022; Becker Citation2005; Bernerth et al. Citation2018; Carlson and Wu Citation2012), limited progress has been made in how organisational researchers handle control variables (Becker et al. Citation2016; Li Citation2021; Curado et al. Citation2023). Instances abound where control variables are employed without clear theoretical grounding and adequate justifications, but rather are simply following precedent set by previous researchers (Becker Citation2005; Spector and Brannick Citation2011). Control variables are sometimes reported with minimal or no information on their measurements (Curado et al. Citation2023; Becker Citation2005; Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012), and suboptimal reporting practices are observed following data analysis (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018; Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018). This is concerning because the use of control variables has the potential to alter or even reverse conclusions, implying that flawed inputs lead to flawed outputs (Curado et al. Citation2023; Li Citation2021; Becker et al. Citation2016). Therefore, this study specifically focuses on control variable utilisation in social entrepreneurship research, and poses the question: How have social entrepreneurship researchers employed and reported control variables in their studies?

This study conducts a comprehensive analysis of control variables use and reporting practices in social entrepreneurship research based on empirical studies published in the Social Enterprise Journal and the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. This comprehensive review addresses several previously unanswered questions regarding the level of adherence to best practices in the use and reporting of control variables by social entrepreneurship researchers. It delves into crucial aspects such as the rationale behind the selection of specific control variables; scrutinises the approaches taken to ensure validity and reliability of the measurements of these variables; and emphasises the importance of transparently and meaningfully presenting the results. By so doing, this study makes a significant contribution to the methodological advancement of social entrepreneurship literature by providing recommendations to enhance the rigour of empirical testing and the precision in reporting results.

To the author’s knowledge, this represents the first detailed review of the utilisation and reporting of control variables in social entrepreneurship research. While there are numerous reviews and research agendas within the social entrepreneurship literature, they typically consist of systematic literature reviews that focus on conceptualising specific thematic areas, suggesting theory-building, or providing analyses that explain the evolution of the field or a concept (e.g. bibliometric analyses) (e.g. bibliometric analyses) (e.g. Hietschold et al. Citation2023; Teasdale et al. Citation2023; Gupta et al. Citation2020; Weerakoon Citation2021; Kaushik et al. Citation2023; Hota, Subramanian, and Narayanamurthy Citation2020; Saebi, Foss, and Linder Citation2019; Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2018; Hussain, Di Pietro, and Rosati Citation2023; Bhardwaj, Weerawardena, and Srivastava Citation2023). Although these reviews make an invaluable contribution to social entrepreneurship research, it is challenging to find an in-depth review on control variable use in the field of social entrepreneurship research.

This analysis is complemented by a set of best-practice recommendations presented in a decision-tree approach, which serve as a valuable resource not only for authors but also for journal editors, reviewers, and a discerning scientific readership. These recommendations aim to enhance the transparency and appropriateness of practices related to control variable usage in social entrepreneurship research. This endeavour is particularly timely, as numerous scholars advocate for quantitative studies with multivariate analysis in the realm of social entrepreneurship (Gupta et al. Citation2020; Short, Moss, and Lumpkin Citation2009; Urbano et al. Citation2017). Yet, there exists a noted deficiency in rigorous hypothesis testing within this field (Kannampuzha and Hockerts Citation2019; Urbano et al. Citation2017). Moreover, empirical work illustrating the significance of control variables is notably absent in the broader business field (Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016; Li Citation2021).

This paper is structured as follows. First, a discussion of control variable use in theory testing research is presented. This is followed by a detailed account of the methodological approach of the study. Results are presented next with a detailed discussion of the findings. The conclusion remarks are made outlining the implications and limitations of the study.

Theoretical background

Control variables

Control variables in quantitative studies serve as additional factors included in a statistical model to address potential influences on the relationship between the independent and dependent variables under investigation. A critical requirement for causally interpreting observed relationships is to eliminate alternative explanations to the observed relationships (Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018). Therefore, control variables play a crucial role in enabling researchers to isolate and quantify the specific effect of the independent variable on the dependent variable. They do this by accounting for factors that might otherwise distort the relationship between the main variables or that are extraneous to the direct effect (Carlson and Wu Citation2012; Spector and Brannick Citation2011). This helps researchers to dismiss alternative explanations for empirical findings. This, in turn, allows for the provision of more precise and meaningful insights regarding predictor variables (or sets of predictors) and their relationship with dependent variables (Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016; Sturman, Sturman, and Sturman Citation2022; Curado et al. Citation2023; Becker Citation2005). Moreover, the inclusion of control variables enhances the accuracy of coefficient estimations during testing, as they account for statistical noise in the dependent variable (Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018).

Research in control variables use

Control variable utilisation in organisational research has been extensively examined in several comprehensive review studies spanning multiple disciplines. These include marketing (e.g. Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018), management (e.g. Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Carlson and Wu Citation2012), international business (e.g. Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018), operations management (e.g. Curado et al. Citation2023), and leadership (e.g. Bernerth et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, selected works in the field of organisational research offer valuable recommendations on the effective use of control variables (e.g. Becker Citation2005; Becker et al. Citation2016; Spector and Brannick Citation2011). These reviews highlight several key observations regarding the utilisation of control variables in organisational research. Specifically, they note instances where control variables are employed without clear theoretical grounding and adequate justifications (Becker Citation2005; Spector and Brannick Citation2011). Furthermore, there is a tendency for control variables to be reported with limited or no information on their measurements (Curado et al. Citation2023; Becker Citation2005; Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012), as well as suboptimal reporting practices following data analysis (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018; Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018).

Despite increased attention in mainstream management literature, accompanied by methodological guidance (e.g. Becker Citation2005; Carlson and Wu Citation2012; Sturman, Sturman, and Sturman Citation2022; Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012), there has been limited progress in how organisational researchers handle control variables (Becker et al. Citation2016; Li Citation2021; Curado et al. Citation2023). Scholars often assume that including statistical controls leads to more accurate estimates of predictor-criterion relationships and eliminates alternative explanations (Becker et al. Citation2016; Carlson and Wu Citation2012). However, this is not always the case, as improper use of control variables in hypothesis testing can result in inaccurate findings and conclusions about the phenomenon being studied (Carlson and Wu Citation2012; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016; Li Citation2021).

Furthermore, merely including control variables based on prior research is inappropriate, particularly in the context of multiple regression analysis. Researchers ‘must explicitly specify the intended control effect, as partialling out shared variance between control variables and independent variables can lead to ambiguous interpretations of regression coefficients’ (Curado et al. Citation2023, 4). Additionally, while an excessive number of control variables reduces the explained variance in outcome associated with predictors, insufficient controls in a model can open the door to alternative explanations for tested relationships (Becker Citation2005; Spector and Brannick Citation2011; Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018).

Social entrepreneurship research and control variable use

Although social entrepreneurs and social entrepreneurial organisations engage in entrepreneurship activities similar to their counterparts in commercial entrepreneurship, opportunity identification and realisation are based on a social problem and the social mission is central in this endeavour (Saebi, Foss, and Linder Citation2019). For social entrepreneurship ‘to have economic meaning, it must address a space in which profit is deemed possible but insufficient to motivate entrepreneurial action unless supplemented by moral or social incentives’ (McMullen and Warnick Citation2016, 200). Thus, social entrepreneurship is a unique phenomenon (Dacin, Dacin, and Tracey Citation2011) calling for new perspectives and careful use of research methods in extant research.

Over the past decade, the field of social entrepreneurship scholarship has seen a notable surge in debate concerning its definition, theoretical framework, and methodological approaches (Bhardwaj, Weerawardena, and Srivastava Citation2023). Most of the studies in social entrepreneurship research takes qualitative approaches (Gupta et al. Citation2020). However, many reviews in social entrepreneurship adopt a systematic literature review approach (Bansal, Garg, and Sharma Citation2019), offering insights into trends and the evolution of research in the field, with occasional references to methodological aspects (e.g. Gupta et al. Citation2020; Hota, Subramanian, and Narayanamurthy Citation2020; Sassmannshausen and Volkmann Citation2018; Hossain, Saleh, and Drennan Citation2017; Saebi, Foss, and Linder Citation2019; Kaushik et al. Citation2023). While these reviews have played an influential and invaluable role in advancing the social entrepreneurship field, there is an urgent need to emphasise methodological progress. Context, for instance, has been assumed to be a pivotal element in theorising about social entrepreneurship, and control variables can be viewed as the contextual factors that delineate the nature of organisations. They represent an integral aspect of knowledge generation for quantitative scholars (Chandra and Kerlin Citation2021). Further, the field is maturing (Williams et al. Citation2023) and the trends indicate the use of larger datasets to analyse various aspects related to social entrepreneurship phenomena employing quantitative approaches (Kannampuzha and Hockerts Citation2019).

Therefore, while there has been significant conceptual work and research agendas aimed at enhancing theoretical foundations, there remains a notable gap in comprehensive methodological reviews, particularly regarding the inclusion of control variables. Further, given the burgeoning prominence of social entrepreneurship phenomena, there is a renewed imperative for scholars in this domain to focus on methodological advancement. This is crucial for updating and clarifying the boundary conditions of social entrepreneurship in relation to other domains, such as business, development, environmentalism, contexts of poverty, and organisational hybridity (Williams et al. Citation2023). Additionally, Short, Moss, and Lumpkin (Citation2009) have pointed out that social entrepreneurship research often lacks formal hypotheses and rigorous methods, advocating for the incorporation of quantitative techniques like multivariate analysis in future studies. Therefore, following extant research (e.g. Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016), this study reviews articles published in the Social Enterprise Journal and the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship to examine the use and reporting of control variables in social entrepreneurship research.

Methodology

Article selection

To evaluate the appropriateness of control variable use and reporting practices in social entrepreneurship research, articles were gathered from the Social Enterprise Journal and the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship spanning from 2010 to 2023. These journals were chosen for their prominence in the field of social entrepreneurship research. The Social Enterprise Journal holds an h-Index of 14 and is ranked in the Q1 category of Scimago Journal Ranking, with an SJR (Scimago Journal Rank) of 0.64. Similarly, the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship features an h-Index of 35 and is also categorised in the Q1 bracket of Scimago Journal Ranking, with an SJR of 0.81 for the year 2022.

The article search was conducted using the search tags ‘Social Enterprise Journal*’ OR ‘Journal of Social Entrepreneurship*’ in the source title of the Scopus database, resulting in 504 publications (e.g. Bernerth et al. Citation2018). Among these, there were 172 publications in the Social Enterprise Journal, comprising 159 articles, seven reviews, and six editorials. In the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, there were 332 references, which included 296 articles, 23 reviews, 10 editorials, and three errata. Following the approach outlined by Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll (Citation2012), reviews, editorials, and errata were excluded from the sample. This process yielded a total of 455 articles. Abstracts of these references were reviewed to identify quantitative studies, resulting in only 90 quantitative studies.

The methodology sections of these 90 references were further examined to identify studies that primarily focused on hypothesis testing, as the emphasis here is on studies utilising control variables. Subsequently, 12 quantitative studies (i.e., Talmage, Bell, and Dragomir Citation2019; Faludi Citation2023; Parente, Lopes, and Marcos Citation2014; Erpf, Ripper, and Castignetti Citation2019; Kusa and Dębkowska Citation2022; Graikioti, Sdrali, and Klimi Kaminari Citation2022; Capella-Peris et al. Citation2020; Lortie et al. Citation2021; Manohar Citation2022; Mamabolo and Myres Citation2020; Jilinskaya-Pandey and Wade Citation2019; Jenner and Oprescu Citation2016; Bargsted et al. Citation2013) were removed from the sample as they did not involve hypothesis testing. They were either using statistical approaches to develop a measurement scale or conducting exploratory analyses. The final sample included 78 articles comprising 24 articles from the Social Enterprise Journal and 54 articles from the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship.

Data collection

The authors, title, journal name, and publication year of each article were initially recorded in a spreadsheet. Subsequently, a coding scheme with specific assessment criteria was formulated. This scheme served as a guide for data collection, aligning with the recommendations outlined in the extant literature (Bernerth et al. Citation2018; Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018; Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012). A subset of 15 articles (comprising 5 from the Social Enterprise Journal and 10 from the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship) were initially scrutinised to determine sub-categories for each criterion. For assessing control variable use, the coding scheme encompassed details such as the types of control variables employed, the rationale for their inclusion, the clarity of the measurements, and the underlying basis for these measurements. Concerning the reporting of control variables, distinct sections were considered: one for control variables, another for the portrayal of the relationships between control variables and independent as well as dependent variables, a section for reporting descriptive statistics, and finally, an evaluation of how the outcomes related to control variables were integrated into the analysis and discussion sections. These specific criteria, along with their respective sub-categories, were recorded in an Excel spreadsheet.

The methodology section of each article was thoroughly scrutinised regarding these criteria, and data were meticulously recorded based on the initially identified sub-categories. As the analysis progressed, new sub-categories emerged for certain criteria. For example, in relation to the reporting of descriptive statistics, the initial sub-categories encompassed scenarios where there was no information on descriptive statistics, cases where only the mean and standard deviation were reported, and instances where all the mean, standard deviation, and correlation were reported. However, as the examination advanced, it was observed that some authors exclusively provided frequencies of the control variables under descriptive statistics without mean, standard deviation, and correlations. To account for this practice, a new sub-category was incorporated into the coding scheme. Another instance arose when recording data on the level of justification for the inclusion of control variables. It became evident that some authors offered justification for only a subset of variables while leaving the rest without explicit clarification. To address this variation in practice, a new sub-category was introduced into the coding scheme.

In addition to the main criteria, data were also recorded on the type of data (i.e., primary, or secondary), the level of analysis (i.e., individual, organisational, and country level), and the dependent variable studied in each article within the sample. Once the data recording process was completed, the file was exported to the SPSS data editor to proceed with the data analysis.

Measures

Author names and title – Recorded as they appear on the publication. Journal – a dummy code was used to identify the two journals: 1 = Social Enterprise Journal and 2 = Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. Control variables used – Recorded the names as appeared on the article.

The use of control variables:

The inclusion of a basis for control variables and the type of justification provided – The best practices suggest that authors should provide a justification for the inclusion of control variables (Becker Citation2005; Spector and Brannick Citation2011). If a justification was provided, it was coded as ‘1’ and if not, ‘0’. The type of the justification provided was coded as follows. If no rationale is provided, it was coded as ‘0’. An example for this would be the control variables employed were age, gender, nationality, level of education, work experience, and length of social entrepreneurial involvement without more being said. This variable was coded ‘1’ if authors mentioned or indicated that it was encouraged by previous studies’ use. For instance, Cavazos-Arroyo and Puente-Diaz (Citation2023, 130) write the variables for trust, pricing and selling capabilities were: firm age, firm size and firm activity (Kemper et al., Citation2011). Another example for this would be based on the previous SEI studies (Bacq and Alt Citation2018; Hockerts Citation2018), the study controlled for the effect of gender (male, female), age […] (Cheah, Loh, and Gunasekaran Citation2023, 8).

If authors provided a rationale based on their own beliefs without citing or linking to a specific theory, it was assigned the code ‘2’. An example of this would be it is likely that firms with high levels of revenue will be able to support a higher number of employees in general and Indigenous employees in particular. As such we controlled for firm revenue in our analyses (Evans, Robinson, and Williamson Citation2021, 13). Preliminary investigations on the sample to develop the coding scheme revealed that some authors provided either empirical findings-based or theoretical justifications for only a subset of control variables, while leaving others without a clear explanation. In such cases, it was considered as a partial justification and assigned the code ‘3’. A response was coded ‘4’ if a full theoretical explanation or prior empirical evidence was provided. For instance, an example for the latter would be what was written in Lough and McBride (Citation2013, 227–228) because previous research suggests that the duration of international service may affect a variety of end-results (Lough Citation2012; Sherraden, Lough, and McBride Citation2008), a variable measuring the total number of weeks the volunteer served abroad is included as a control variable.

Measurements of control variables – Provision of measurements for control variables is essential to ensure the replicability and the validity of a study (Becker Citation2005; Carlson and Wu Citation2012). Hence, clarity of the measurements provided was coded as follows: if the authors did not provide any information about measurements, it was coded as ‘0’. If authors named the variables used for control, it was coded as ‘1’. If control variables were named and measurements were given, that was coded as ‘2’.

Basis of control variable measurements - Further, reasons for measuring a control variable in such a way that explained in the article were also examined and coded following the best practices stipulated in Becker (Citation2005). Thus, if no justification was provided for measurements, it was coded as ‘0’. If authors had followed predicated use, it was coded as ‘1’. An example for this would be based on the information given by the B Impact Assessment as well as Dun & Bradstreet, and consistent with previous studies drawing on Certified B Corporations (e.g. Winkler, Brown, and Finegold Citation2019; Gazzola et al. Citation2019), a dichotomous variable was created to control for whether or not the firm sells a product or service (Fernhaber and Hawash Citation2021, 9). When authors provided a rational justification, it was coded as ‘2’. For instance, Lee et al. (Citation2022, 351)’ explanation is an example for this purpose. They write: given the lack of a direct measure of government expenditure on social welfare, we use the Heritage Foundation’s index of Government Size as a proxy for government expenditure on social welfare (Stephan, Uhlaner and Stride Citation2015). If authors justified the measurements based on statistical measures such as factor analysis or any other method related to reliability and validity (Becker Citation2005), this was considered as psychometric measure-based justification and coded as ‘3’. An example for this would be we used the log of both the GNI and country populations as control variables for all analyses. As per Keene (Citation1995), the log transformation was used to remedy the violations of some statistical assumptions because of the size of these constructs (Roy, Brumagim, and Goll Citation2014, 50).

Reporting of control variables:

A separate section for control variables – The best practices for control variables reporting suggest that the inclusion of a separate section for control variables indicate a higher attention to these variables (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Becker Citation2005). Thus, if a section was devoted for control variables with a sub-heading, it was coded as ‘1’ and if there wasn’t, a ‘0’ was assigned.

Clarification of the relationships between controls and dependent variables – Prediction of the relationship between any control variables and dependent variables is essential to understanding the potential impact of inclusion. Thus, ‘0’ was coded if there is no explanation was provided in the methods section about the relationships, and ‘1’ was assigned if an explanation was provided with citations (e.g. Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018).

Descriptive statistics of control variables – Extant literature strongly recommends listing of control variables in descriptive statistics (i.e., mean and standard deviation) and the provision of correlations among the control variables and study variables in the correlation table (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Sturman, Sturman, and Sturman Citation2022; Becker Citation2005) as they indicate the key properties of the sample and association between variables (Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018). However, some authors provided only frequencies of the control variables. Therefore, ‘0’ was assigned if no descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies, mean, standard deviation, and correlations) were given in results section and ‘1’ was assigned if only the frequencies were provided for control variables. There were instances where the authors reported only the mean and standard deviations of control variables and such situations were coded as ‘2’. If mean, standard deviations, and correlations were reported for all the control variables, it was coded as ‘3’.

Results section addressed the controls – Reporting the results of the control variables and incorporating them in the analysis to derive findings is an important methodological practice (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012). Thus, a code of ‘0’ was assigned if control variables were not discussed other than including in the outputs in the results section. This variable was assigned with ‘1’ if authors discussed the relationships of control variables with the dependent variable in the results/analysis section.

Discussion section addressed the controls – Discussion of results of the control variables along with implications of the study in the discussion section as it relates to the interpretation of reliability, generalisability, and replicability of the study (Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018). Thus, ‘0’ was assigned if control variables results had not discussed in the discussion section. If the authors had explicitly discussed and integrated the results of the control variables in the discussion section, it was coded as ‘1’. For instance, Ayob (Citation2018) justified using income group as a country-level control and dropping of few other variables as controls in methods section. In their results and discussion section they discuss the findings related to control variables and make conclusions as follows: Although our estimation has lack of controls, it is important to highlight the strong correlations between GDP and ethnic diversity (0.604), generalised trust (0.808), as well as inter-religious trust (0.542) at a 0.01 significant level. Superficially, we would say that ethnic groups in high-income economies are more homogenous, and trust has been strongly developed there (Ayob Citation2018, 7).

Data analysis

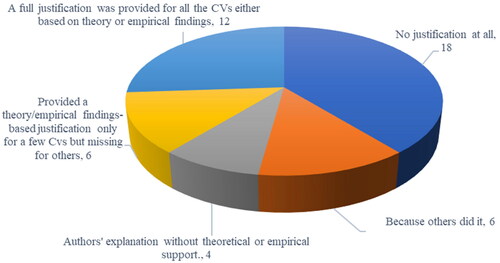

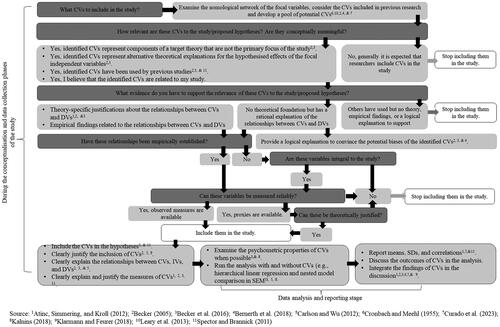

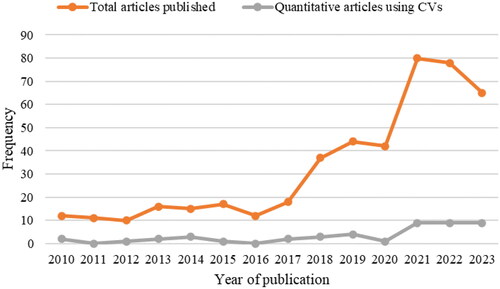

The data analysis primarily employed descriptive approaches, including frequencies and percentages, given the exploratory nature of the research question. Additionally, graphical techniques such as cross tabulation, tabulation (refer to ), and graphs (see and ) were utilised to effectively illustrate variations in the study variables. Comparisons were drawn to similar studies in other disciplines for further contextualisation and insight (e.g. Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Nielsen and Raswant Citation2018; Curado et al. Citation2023; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016) in the discussion section to make conclusions and derive implications for future research. This approach enabled the development of the decision tree of utilising and reporting control variables ().

Figure 1. Total social entrepreneurship articles published vs quantitative articles using CVs (2010–2023).

Table 1. Dependent variables studied in social entrepreneurship research.

Table 2. Top 10 control variables used in the studies.

Table 3. Reporting of control variables in the social entrepreneurship research.

Findings

Profile of the studies in the sample

shows the growth of social entrepreneurship publications and the quantitative studies that used control variables in the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship and Social Enterprise Journal since 2010–2013.

Compared to the total number of outputs each year, studies utilising control variables in quantitative research form a relatively small proportion. This aligns with findings in previous reviews by Short, Moss, and Lumpkin (Citation2009), Gupta et al. (Citation2020), and Klarin and Suseno (Citation2023). Out of the initial pool of 78 quantitative studies identified, only 46 (59%) incorporated control variables in testing proposed hypotheses or models. Among these, 14 articles were sourced from the Social Enterprise Journal and 32 from the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship (refer to Appendix). Approximately 46% of these articles examined phenomena at the individual level, focusing on social entrepreneurs or workers in social enterprises. The remaining 54% delved into macro-level factors, including organisational, regional, or country-level variables.

The status of dependent variables studied in these articles is detailed in . In total, 28 distinct dependent variables were analysed across the 46 articles. The most prevalent among them is ‘social entrepreneurial intention’, investigated in 24% of the studies. Organisational performance (e.g. social enterprise performance, economic and social performance) was the focus of four studies (9%). Social entrepreneurship itself was a subject in three studies (6.5%), while another six studies examined social entrepreneurial engagement, organisational impact (e.g. social impact), and social venture financing each receiving attention in two studies (13% each). Additionally, 22 other dependent variables were explored in the realm of social entrepreneurship research (see ).

Most of the studies (78%) used regression models as the analytical method while 20% of the studies used structural equation modelling. Moreover, out of those 38 studies that used regression models, 23 studies used linear regression models (60%) and 10 used logistic regression models (26%).

The use of control variables in social entrepreneurship research

A total of 213 control variables were found in the studied sample. Out of the 46 articles in the sample, ten utilised four control variables (22%), seven articles incorporated five control variables (15%) and another six articles used three control variables (13%). Additionally, six articles (13%) relied on only one control variable. Notably, there were four articles that employed at least ten control variables (9%), with the highest count being 14 variables included in the model.

Control variables used

The top 10 control variables utilised in these articles are detailed in , along with a few examples of the dependent variables investigated in the studies.

Notably, approximately 46% of the studies incorporated respondent’s age and gender as control variables in their tested models. Additionally, the respondent’s education level emerged as a prominent individual-level control. At the organisational level, firm age and firm size were the most frequently used control variables in the studied sample. Furthermore, 29 studies included both continuous and categorical variables (63%), while 12 studies exclusively employed categorical variables (26%). Notably, only five studies solely used continuous variables (11%).

Justification for the inclusion of control variables

Out of the studied sample, 28 articles (61%) offered some form of justification for including control variables in their models. Interestingly, there was a slight variation in this practice between the two journals. Specifically, 64% of the articles from the Social Enterprise Journal in the sample provided a justification, while for the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, it was 59%.

The level of justification provided

exhibits the levels of justification provided for the inclusion of control variables.

Nearly 39% of the social entrepreneurship studies that incorporated control variables to test hypotheses did not offer a justification for including these variables. However, around 34% of the articles have provided some kind of justification. Only 12 studies (26%) provided a detailed theoretical explanation for the inclusion of control variables while another six studies (13%) included control variables just because others did it. Interestingly, four studies (8%) depended on the author’s own justification without a theoretical or empirical support. Looking at it from another angle, it’s worth noting that out of the total, 20 studies (43%) didn’t include any citations. Interestingly, among those that did include control variables without providing a justification or explanation, only one study cited the variables that were added.

Information about measurements of control variables

Approximately 56.5% of the social entrepreneurship studies in the sample explicitly identified the included control variables and provided details about their measurements. Surprisingly, nearly 15% of the articles lacked any information regarding the measurements of their control variables. What’s interesting is that almost 91% of the articles did not offer any justification for the specific measurements of their control variables. Nevertheless, 2 studies adopted the predicated approach (4%), 1 study followed the rational approach in measuring control variables (2.2%), while another followed the psychometric approach (2.2%).

The reporting of control variables in social entrepreneurship research

Reporting of control variables was explored in terms of five areas: inclusion of a separate section on control variables, explanation of relationships of control variables to independent and dependent variables, reporting of descriptive statistics of control variables, and discussion of control variables in the results and discussions sections. These results are summarised in .

A separate section for control variables

Overall, only 50% of the articles in the sample included a separate section to report the control variables used in the study. There is a substantial difference in this practice between the two journals. While only 14% of the articles in the Social Enterprise Journal included a dedicated section, this figure was significantly higher at 66% for the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship.

Reporting of relationships of control variables to independent and dependent variables

Regarding the reporting of how control variables are related to independent variables and dependent variables, nearly 67% of the sampled articles omitted any discussion concerning these relationships in the methodology (). A mere 33% provided a comprehensive explanation for all control variables in the methods section. In the Social Enterprise Journal, a substantial 79% of articles failed to elucidate these relationships, while this figure was slightly lower at 63% for the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship. It was interesting to note that nearly 43% of those who included a separate section to discuss control variables in methodology did not explain or predict their relationships to dependent variables. Yet only one study that did not have a dedicated section for control variables fully explained and predicted the potential associations with dependent variables.

Reporting of descriptive statistics

In terms of reporting descriptive statistics in the results section, overall, only 54% of the studies included all means, standard deviations, and correlations for the control variables. Approximately 20% of the studies did not provide any of this information, while nearly 17% reported only the frequencies related to the control variables. Notably, there were substantial differences observed between the journals. For instance, around 7% of the articles in the Social Enterprise Journal did not offer any descriptive statistics for control variables, while this figure was notably higher at 25% for the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship (). Conversely, a significant 66% of the articles in the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship provided all the necessary means, standard deviations, and correlations for control variables, whereas only 29% of the studies in the Social Enterprise Journal included this information.

Incorporation of control variable results in analysis and discussion sections

It was discovered that only about 54% of the studies talked about the results of control variables in their analysis. Furthermore, indicating a poor methodological practice, a mere 9% of the total studies discussed the findings of control variables in the discussion section. This pattern was consistent across both journals.

Discussion

This study aimed to address the question, ‘How have social entrepreneurship researchers used and reported control variables in social entrepreneurship research’? The analysis, based on quantitative studies (i.e., theory/hypotheses testing) published in the Social Enterprise Journal and the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, revealed several key findings.

Regarding the use of control variables in social entrepreneurship research, results found that (1) approximately 59% of the studies incorporated control variables in theory testing. Respondent’s age, gender, education, firm age, and firm size are prominently featured. Among those using control variables, (2) only 34% provided some form of justification for their inclusion in the model; (3) a mere 22% grounded their justification in relevant theories; (4) only 57% clearly specified and provided measurements for control variables; and (5) an overwhelming 85% did not offer any justification for the measurements used.

These findings suggest that the use of control variables in testing social entrepreneurship theories is a widely acknowledged practice, aligning closely with the approach in management research, which was reported at 67% (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012). Notably, age and gender are prominent control variables in social entrepreneurship research, in line with practices in applied psychology (Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016) and leadership research (Bernerth et al. Citation2018). This popularity may arise from the practicality of data collection (Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016). However, scholars should exercise caution when selecting control variables like age in entrepreneurship research, ensuring there is always a strong theoretical rationale for their inclusion. Control variables will only be benefited if they are correlated with the hypothesised variables but undue addition may lead to multicollinearity subsequently committing Type 1 errors among focal variables rather than isolating their true effects (Kalnins Citation2018). Further, the mainstream entrepreneurship literature indicates that explicit theoretical explanations for the relationship between an entrepreneur’s age and their success are infrequent, often fragmented, and existing perspectives are characterised by simplicity, ambiguity, and occasional contradiction (e.g. Zhang and Acs Citation2018). Despite this, the basis for including control variables in the models exhibited suboptimal methodological practices. Nearly 39% of the studies did not provide any justification at all, which stands in stark contrast to practices in other disciplines like management research, where this figure is reported to be 18% (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012). Becker (Citation2005) noted that researchers often fail to offer a robust explanation for including control variables. One possible reason for this could be the limited number of articles that have strongly emphasised the importance of justifying the choice of control variables (Li Citation2021).

Furthermore, this study revealed that only 22% of the examined studies furnished a theoretical rationale for incorporating control variables. This aligns with the observations made by Bernerth et al. (Citation2018) in the realm of leadership research, Curado et al. (Citation2023) in operations management research, and Bernerth and Aguinis (Citation2016) in applied psychology research, where most studies included control variables based on prior research. Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll (Citation2012) found that 48% of management researchers grounded their use of control variables in either theoretical foundations or empirical evidence, which bears some resemblance to the 41% observed in social entrepreneurship research. In another instance of suboptimal methodology, nearly 43% of social entrepreneurship studies failed to provide citations for the inclusion of control variables, a notable departure from the field of management research, where this figure was approximately 27% (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012). Ensuring clarity in the measurement of control variables constitutes a critical methodological aspect, but only 57% of the studies met this criterion. This finding diverges significantly from the landscape in management research, where only 3.6% did not offer clear names and measurements for their control variables (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012).

However, what this indicates is that social entrepreneurship researchers often incorporate control variables based on prior literature without a deep understanding of the underlying rationale. This ‘isomorphic’ practice, as noted by Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll (Citation2012), raises concerns because, without theoretical guidance, the use of control variables may alter or even reverse conclusions, suggesting that flawed inputs lead to flawed outputs (Curado et al. Citation2023; Li Citation2021; Becker et al. Citation2016). Application of such control variables without a theoretical or strong practical justification is problematic as social entrepreneurship is a heterogeneous phenomenon and for instance, social entrepreneurial organisations tend to indicate notable differences due to factors such as types of government, stages of economic development, the role of civil society, and historical macro-institutional processes of the ecosystem that they operate (Kerlin et al. Citation2021; Dacin, Dacin, and Tracey Citation2011; de Bruin and Teasdale Citation2019). This tendency of using control variables following others may stem from a set of widespread assumptions among scholars such as that extraneous variables can distort the relationships between focal variables and the absence of control variables might lead to spurious connections between independent and dependent variables. Consequently, scholars may assume that the inclusion of multiple control variables is a safer and statistically relevant practice (Carlson and Wu Citation2012; Becker Citation2005). Yet, quantitative method experts argue that including control variables can lead to a reduction in available degrees of freedom and statistical power, subsequently limiting the amount of variance that can be explained in the outcomes of interest (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Becker Citation2005; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016; Li Citation2021).

In relation to reporting practices of control variable use, it was found that (1) only 26% of the studies elucidated how the control variables related to the dependent variables of interest; (2) about 54% of the studies presented main descriptive statistics (means, standard deviations, and correlations) for control variables; (3) similarly, only 54% included a discussion of descriptive statistics in the results section; (4) merely 9% of the studies discussed the results of control variables in the discussion section of the manuscript; and (5) there were notable differences between the two journals regarding the inclusion of justification for the incorporation of control variables and the reporting of descriptive statistics related to these variables. The results for clarification of the relationship between the dependent variables and control variables were disappointing as nearly two-thirds of studies have not followed this best practice which is a similar trend to that of management (e.g. Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012) and operations management research (e.g. Curado et al. Citation2023). This outcome was expected, as most studies did not establish a theoretical foundation for including control variables in the model. Some authors mention and detail the measurements of control variables in the methodology section but fail to address their outcomes in the results and discussion sections. This highlights a significant concern arising from the absence of theoretical justifications for the relationships between control variables and dependent variables.

Based on these results, this study offers a crucial set of recommendations in the form of a decision tree () building on extant research (e.g. Curado et al. Citation2023; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016).

Recommendation 1: Social entrepreneurship researchers should ensure that their selection of control variables aligns with the theoretical framework guiding the variables under study (Carlson and Wu Citation2012; Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012). This pivotal decision-making process should occur at the outset during the conceptualisation phase of the study (Becker Citation2005; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016). It entails a careful examination of both the theoretical foundations of the key variables being investigated and the available empirical evidence, while also considering their logical relevance and appropriateness within the research context (Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018).

Recommendation 2: To incorporate control variables into the theoretical model, it is advised to explore the nomological network of the study’s core concepts. This network reveals connections between key concepts, potential moderators, mediators, and contextual factors, guiding the selection of relevant control variables. These variables, correlated with both independent and dependent variables, need to be controlled for to prevent distortion of the true relationship. Establishing a scientifically valid construct necessitates its presence in the nomological network (Cronbach and Meehl Citation1955). However, researchers often overlook this, leaving construct relationships unclear (Leary et al. Citation2013). A well-designed nomological network prevents excessive control, ensuring that control variables are rooted in conceptual comprehension (Carlson and Wu Citation2012). It pinpoints crucial variables, diminishing complexity and multicollinearity while heightening statistical power (Becker et al. Citation2016). This method not only encourages the justification for the theoretical model but also enhances the construct’s validity in the study of social entrepreneurship.

Recommendation 3: Once a pool of potential control variables has been identified, it is crucial to ask a series of questions (refer to ) to determine their relevance and suitability for the study. Effective control variables should either ‘represent components of the target theory that are not the primary focus of the study or offer alternative theoretical explanations for the expected effects of the primary independent variables’ (Becker et al. Citation2016, 159). It is not advisable to include control variables solely based on prior research, as this may result in over-controlling in regression models if the covariance between the control variable and dependent variable does not reflect a contaminant in the dependent variable (Curado et al. Citation2023). In cases where there is no established theoretical background, but a strong logical justification exists for a control variable, it is recommended to provide a detailed explanation of how it could introduce bias into the model (Becker Citation2005; Becker et al. Citation2016). This ensures transparency in the research process and helps readers understand the rationale behind including such control variables. Furthermore, the inclusion of control variables in the hypotheses in the theory development section (e.g. theoretical background and hypotheses development) would establish a strong alignment between theory development and subsequent analysis. This establishes a more substantial and essential theoretical basis for a study.

Recommendation 4: Social entrepreneurship researchers are advised to incorporate control variables that are both theoretically significant and reliably measurable, thereby minimising the reliance on proxies in their studies. As illustrated in , the next step is for the researcher to ascertain whether the relationships between the identified control variables and the dependent variables have been empirically validated (Carlson and Wu Citation2012). If not, it becomes crucial to evaluate whether these control variables are essential to the study. If they are deemed integral, the subsequent decision involves determining their reliability in measurement. As recommended by the methods literature (e.g. Becker et al. Citation2016; Spector and Brannick Citation2011), researchers should prioritise the use of directly observable measures for control variables whenever feasible, while minimising reliance on proxies. Proxies may exhibit covariance with the dependent variable, but they are not rooted in theory and do not provide a direct explanation for the relationship between a meaningful control variable and the dependent variable (Kalnins Citation2018). For instance, Estrin, Mickiewicz, and Stephan (Citation2016) used ‘entrepreneurship experience’ as a proxy for human capital while Roy, Brumagim, and Goll (Citation2014) used ‘the number of social entrepreneurs in a country’ as a proxy for prevalence of social entrepreneurship phenomenon. In such scenarios, it becomes challenging for a researcher to accurately gauge the strength of the relationship between the proxy and the genuine control variable of interest (Becker et al. Citation2016). Consequently, this could lead to a different outcome compared to what would have been obtained if a more meaningful control variable had been employed (Carlson and Wu Citation2012).

Recommendation 5: Regarding the reporting of control variables in a study, it is advisable to incorporate a distinct section within the methodology. This section should provide a clear definition and rationale for the inclusion or exclusion of control variables. For example, Ayob (Citation2018, 5) provided a strong justification for excluding a set of control variables as follows: …Our attempt to include country-level controls previously studied leads to statistical deficiency for two reasons: (1) most of the institutional controls are strongly correlated, thus potentially cause multicollinearity. […] Due to a small number of countries for analysis, these controls were dropped because they would have impeded our estimation. Further, this section should clearly explain the relationships between control variables and dependent variables based on theoretical and empirical support (Atinc, Simmering, and Kroll Citation2012; Bernerth and Aguinis Citation2016; Carlson and Wu Citation2012). It is imperative to provide a well-defined explanation of measures along with the rationale behind their selection, supported by relevant literature. Failure to support or validate a theoretical prediction, particularly within a comprehensive network of interconnected concepts, can serve as compelling evidence for potential theory falsification. (Popper Citation2005; Hagger, Gucciardi, and Chatzisarantis Citation2017).

Recommendation 6: It is advisable to handle control variables with the same level of scrutiny as other focal variables in the study. Therefore, evaluating their psychometric properties would improve the reliability and validity of the study variables. The practice of social entrepreneurship may have significant variations across different contexts (see de Bruin and Teasdale Citation2019; Newth and Woods Citation2014; Sengupta and Sahay Citation2017). Therefore, sometimes control variables may exhibit different psychometric properties in different contexts. Checking these properties will enable researchers to adapt or modify measurement instruments to better suit the specific context. Researchers should test hypotheses and present results both with and without control variables. In line with this practice, employing advanced techniques such as hierarchical linear regression and nested model comparisons in Structural Equation Modelling is recommended. This approach allows researchers to discern the influence of the control variables in the study.

Recommendation 7: In terms of reporting results, social entrepreneurship researchers should include means, standard deviations, and correlations for control variables alongside the study variables () (Becker Citation2005; Klarmann and Feurer Citation2018). Moreover, it is crucial to analyse the results of control variables in the analysis or findings section and integrate these outcomes into the discussion section. This practice ensures the reliability, validity, and generalisability of the study findings.

Finally, an important implication for social entrepreneurship research reviewers and editors is that they should request and challenge the authors to provide clear rationale for the inclusion of control variables in the manuscripts ensuring rigour in the empirical study. Reviewers can also encourage authors to follow best practices of control variable use in the studies. Hence, this detailed review of control variables utilisation and reporting practices contributes to enhancing overall methodological rigour and precision in social entrepreneurship research.

Limitations of the study

Like any study, this one has its limitations. While it focused on two prominent journals in the social entrepreneurship field, the Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, and the Social Enterprise Journal, covering the period from 2010 to 2023, there are numerous other journals that publish social entrepreneurship research (e.g. Non-profit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, Journal of Business Ethics, and Voluntas). Future research on control variables could expand the sample size to include articles from these sources. Additionally, while this study examined the reporting of control variables, it did not analyse how the inclusion of control variables may have influenced study results or conclusions. This could be an area for exploration in future research.

Conclusions

This study aimed to investigate the utilisation and reporting practices of control variables in social entrepreneurship research. The findings reveal that while control variable usage is common, only a minority of social entrepreneurship studies incorporate control variables with strong theoretical or empirical foundations and provide clear measurements. Moreover, the results suggest that in most studies, the consideration of control variables occurs late in the research process, rather than being integrated from the conceptualisation stage. Additionally, most studies fail to discuss control variable results in the findings and discussion sections. This study highlights the significance of treating control variables as diligently as focal variables during the study’s conceptualisation phase, emphasising the inclusion of theoretically meaningful control variables. As a step towards enhancing the rigour of social entrepreneurship research, this study offers a set of recommendations organised within a decision-tree structure based on a detailed review of social entrepreneurship literature. These recommendations are intended to guide social entrepreneurship researchers, reviewers, and journal editors in promoting the thoughtful selection of control variables based on theoretical foundations and conducting comprehensive and judicious analyses with careful interpretation of results.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alarifi, G., P. Robson, and E. Kromidha. 2019. “The Manifestation of Entrepreneurial Orientation in the Social Entrepreneurship Context.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (3): 307–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541015

- Alnahedh, M., and N. Alabduljader. 2021. “Do Human Rights Violations Elicit or Impede Social Entrepreneurship?” Social Enterprise Journal 17 (3): 361–378. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-07-2020-0055

- Aloulou, W. J., and E. A. Algarni. 2022. “Determinants of Social Entrepreneurial Intention: Empirical Evidence from the Saudi Context.” Social Enterprise Journal 18 (4): 605–625. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-11-2021-0086

- Atinc, Guclu, Marcia J. Simmering, and Mark J. Kroll. 2012. “Control Variable Use and Reporting in Macro and Micro Management Research.” Organizational Research Methods 15 (1): 57–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428110397773

- Ayob, A. H. 2018. “Diversity, Trust and Social Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2017.1399433

- Bacq, S., and Alt E. 2018. “Feeling Capable and Valued: A Prosocial Perspective on the Link Between Empathy and Social Entrepreneurial Intentions.” Journal of Business Venturing 33 (3): 333–350. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.01.004

- Bacq, Sophie, Chantal Hartog, and Brigitte Hoogendoorn. 2013. “A Quantitative Comparison of Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: Toward a More Nuanced Understanding of Social Entrepreneurship Organizations in Context.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 4 (1): 40–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2012.758653

- Baierl, R., D. Grichnik, M. Spörrle, and I. M. Welpe. 2014. “Antecedents of Social Entrepreneurial Intentions: The Role of an Individual’s General Social Appraisal.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 5 (2): 123–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2013.871324

- Bansal, Sanchita, Isha Garg, and Gagan Sharma. 2019. “Social Entrepreneurship as a Path for Social Change and Driver of Sustainable Development: A Systematic Review and Research Agenda.” Sustainability 11 (4): 1091. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11041091

- Bargsted, M., M. Picon, A. Salazar, and Y. Rojas. 2013. “Psychosocial Characterization of Social Entrepreneurs: A Comparative Study.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 4 (3): 331–346. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2013.820780

- Becker, Thomas E. 2005. “Potential Problems in the Statistical Control of Variables in Organizational Research: A Qualitative Analysis with Recommendations.” Organizational Research Methods 8 (3): 274–289. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428105278021

- Becker, Thomas E., Guclu Atinc, James A. Breaugh, Kevin D. Carlson, Jeffrey R. Edwards, and Paul E. Spector. 2016. “Statistical Control in Correlational Studies: 10 Essential Recommendations for Organizational Researchers.” Journal of Organizational Behavior 37 (2): 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2053

- Bernerth, Jeremy B., and Herman Aguinis. 2016. “A Critical Review and Best‐Practice Recommendations for Control Variable Usage.” Personnel Psychology 69 (1): 229–283. https://doi.org/10.1111/peps.12103

- Bernerth, Jeremy B., Michael S. Cole, Erik C. Taylor, and H. Jack Walker. 2018. “Control Variables in Leadership Research: A Qualitative and Quantitative Review.” Journal of Management 44 (1): 131–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317690586

- Bhardwaj, Rohit, Jay Weerawardena, and Saurabh Srivastava. 2023. “Advancing Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Morphological Analysis and Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 14: 1–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2023.2199748

- Bloom, P. N., and B. R. Smith. 2010. “Identifying the Drivers of Social Entrepreneurial Impact: Theoretical Development and an Exploratory Empirical Test of SCALERS.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1 (1): 126–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420670903458042

- Capella-Peris, C., J. Gil-Gómez, M. Martí-Puig, and P. Ruíz-Bernardo. 2020. “Development and Validation of a Scale to Assess Social Entrepreneurship Competency in Higher Education.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 11 (1): 23–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1545686

- Caringal-Go, J. F., and M. R. M. Hechanova. 2018. “Motivational Needs and Intent to Stay of Social Enterprise Workers.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9 (3): 200–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1468352

- Carlson, Kevin D., and Jinpei Wu. 2012. “The Illusion of Statistical Control: Control Variable Practice in Management Research.” Organizational Research Methods 15 (3): 413–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428111428817

- Cavazos-Arroyo, J., and R. Puente-Diaz. 2023. “The Effect of Network Capabilities, Trust and Pricing and Selling Capabilities on the Impact of Social Enterprise.” Social Enterprise Journal 19 (2): 123–143. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-02-2022-0020

- Chandra, Yanto, and Janelle A. Kerlin. 2021. “Social Entrepreneurship in Context: Pathways for New Contributions in the Field.” Social Enterprise Journal 14 (2): 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1080/17516234.2020.1845472

- Cheah, J. S. S., Q. Yeoh, and Y. Chandra. 2023. “The Influence of Causation, Entrepreneurial and Social Orientations on Social Enterprise Performance in the Nascent Ecology of Social Enterprise.” Social Enterprise Journal 19 (3): 308–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-11-2022-0102

- Cheah, J. S. S., S. Loh, and A. Gunasekaran. 2023. “Motivational Catalysts: The Dominant Role between Prosocial Personality and Social Entrepreneurial Intentions among University Students.” Social Enterprise Journal 19:1–20. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-04-2023-0036

- Coskun, M. E., T. Monroe-White, and J. Kerlin. 2019. “An Updated Quantitative Analysis of Kerlin’s Macro-Institutional Social Enterprise Framework.” Social Enterprise Journal 15 (1): 111–130. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-03-2018-0032

- Costa, M., and F. Delbono. 2023. “Regional Resilience and the Role of Cooperative Firms.” Social Enterprise Journal 19:1–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-07-2022-0064

- Cronbach, Lee J., and Paul E. Meehl. 1955. “Construct Validity in Psychological Tests.” Psychological Bulletin 52 (4): 281–302. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0040957

- Cunha, J., C. Ferreira, M. Araújo, and M. L. Nunes. 2022. “The Mediating Role of Entrepreneurial Intention between Creativity and Social Innovation Tendency.” Social Enterprise Journal 18 (2): 383–405. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-04-2021-0022

- Curado, Carla, Mírian Oliveira, Dara G. Schniederjans, and Eduardo Kunzel Teixeira. 2023. “Control Variable Use and Reporting in Operations Management: A Systematic Literature Review and Revisit.” Management Review Quarterly 73: 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-023-00348-2

- Dacin, M. Tina, Peter A. Dacin, and Paul Tracey. 2011. “Social Entrepreneurship: A Critique and Future Directions.” Organization Science 22 (5): 1203–1213. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0620

- de Bruin, Anne, and Simon Teasdale. 2019. “Exploring the Terrain of Social Entrepreneurship: New Directions, Paths Less Travelled.” In Research Agenda for Social Entrepreneurship, edited by Anne de Bruin and Simon Teasdale, 1–12. London, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing Ltd.

- Desa, G., I. M. Dunham, N. Jeong, S. Basu, and D. Kleinrichert. 2023. “Culture Matters: Antecedent Effects of Societal Culture on the Resource Mobilisation Strategies of Social Ventures.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 14: 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2023.2213734

- Duong, C. D. 2023. “Applying the Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory to Investigate Determinants of Students’ Social Entrepreneurship: Moderation Role of Perceived University Support.” Social Enterprise Journal 19 (2): 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-10-2022-0091

- Erpf, P., M. Gmür, and J. Baumann-Fuchs. 2022. “Does the Business Suit Fit? Drivers for Economic Performance in Social Enterprises.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2022.2090416

- Erpf, P., M. J. Ripper, and M. Castignetti. 2019. “Understanding Social Entrepreneurship Based on Self-Evaluations of Organizational Leaders–Insights from an International Survey.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (3): 288–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541014

- Estrin, Saul, Tomasz Mickiewicz, and Ute Stephan. 2016. “Human Capital in Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship.” Journal of Business Venturing 31 (4): 449–467. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.05.003

- Evans, M. M., J. A. Robinson, and I. O. Williamson. 2021. “The Effect of HRM Practices on Employment Outcomes in Indigenous Social Enterprises.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 12: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2021.2001360

- Faludi, J. 2023. “How to Create Social Value through Digital Social Innovation? Unlocking the Potential of the Social Value Creation of Digital Start-Ups.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 14 (1): 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2020.1823871

- Fedele, A., and R. Miniaci. 2010. “Do Social Enterprises Finance Their Investments Differently from for-Profit Firms? The Case of Social Residential Services in Italy.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship, 1 (2): 174–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2010.511812

- Fernhaber, S. A., and R. Hawash. 2021. “Are Expectations for Businesses That ‘Do Good’ Too High? Trade-Offs between Social and Environmental Impact.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 12: 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2021.1874486

- Forster, F., and D. Grichnik. 2013. “Social Entrepreneurial Intention Formation of Corporate Volunteers.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 4 (2): 153–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2013.777358

- Garrido-Skurkowicz, N., R. Wittek, and C. La Roi. 2022. “Performance of Hybrid Organisations. Challenges and Opportunities for Social and Commercial Enterprises.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13: 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2022.2115529

- Gazzola, P., D. Grechi, P. Ossola, and E. Pavione. 2019. “CertifiedBenefit Corporations as a New Way to Make Sustainable Business: The Italian Example.” Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management 26 (6): 1435–1445. " https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1758

- Graikioti, S., D. Sdrali, and O. Klimi Kaminari. 2022. “Factors Determining the Sustainability of Social Cooperative Enterprises in the Greek Context.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13 (2): 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2020.1758197

- Gras, D., and G. T. Lumpkin. 2012. “Strategic Foci in Social and Commercial Entrepreneurship: A Comparative Analysis.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 3 (1): 6–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2012.660888

- Gupta, Parul, Sumedha Chauhan, Justin Paul, and Mahadeo P. Jaiswal. 2020. “Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Review and Future Research Agenda.” Journal of Business Research 113: 209–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.032

- Hagger, Martin S., Daniel F. Gucciardi, and Nikos L. D. Chatzisarantis. 2017. “On Nomological Validity and Auxiliary Assumptions: The Importance of Simultaneously Testing Effects in Social Cognitive Theories Applied to Health Behavior and Some Guidelines.” Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1933. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01933

- Hechavarría, Diana M., Steven A. Brieger, Ludvig Levasseur, and Siri A. Terjesen. 2023. “Cross‐Cultural Implications of Linguistic Future Time Reference and Institutional Uncertainty on Social Entrepreneurship.” Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal 17 (1): 61–94. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1450

- Hietschold, N., and C. Voegtlin. 2022. “Blinded by a Social Cause? Differences in Cognitive Biases between Social and Commercial Entrepreneurs.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13 (3): 431–452. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2021.1880466

- Hietschold, Nadine, Christian Voegtlin, Andreas Georg Scherer, and Joel Gehman. 2023. “Pathways to Social Value and Social Change: An Integrative Review of the Social Entrepreneurship Literature.” International Journal of Management Reviews 25 (3): 564–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12321

- Hockerts, K. 2018. “The Effect of Experiential Social Entrepreneurship Education on Intention Formation in Students.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 9 (3): 234–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1498377

- Hossain, Sayem, M. Abu Saleh, and Judy Drennan. 2017. “A Critical Appraisal of the Social Entrepreneurship Paradigm in an International Setting: A Proposed Conceptual Framework.” International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal 13 (2): 347–368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-016-0400-0

- Hota, Pradeep Kumar, Balaji Subramanian, and Gopalakrishnan Narayanamurthy. 2020. “Mapping the Intellectual Structure of Social Entrepreneurship Research: A Citation/co-Citation Analysis.” Journal of Business Ethics 166 (1): 89–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04129-4

- Humbert, A. L., and M. A. Roomi. 2018. ““Prone to “Care”?: Relating Motivations to Economic and Social Performance among Women Social Entrepreneurs in Europe.” Social Enterprise Journal 14 (3): 312–327. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-11-2017-0058

- Hussain, Nosheen, Francesca Di Pietro, and Pierangelo Rosati. 2023. “Crowdfunding for Social Entrepreneurship: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 14: 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2023.2236637

- Ip, C. Y., C. Liang, and C. P. Chou. 2022. “Determinants of Purchase Intentions for Social Enterprise Products: Online Consumers’ Perceptions of Two Agricultural Social Enterprises in Taiwan.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13: 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2022.2132276

- Jace, K., D. Koumanakos, and A. Tsagkanos. 2022. “Bankruptcy Prediction in Social Enterprises.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13 (2): 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2020.1763438

- Jenner, P., and F. Oprescu. 2016. “The Sectorial Trust of Social Enterprise: Friend or Foe?” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 7 (2): 236–261. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2016.1158732

- Jilinskaya-Pandey, M., and J. Wade. 2019. “Social Entrepreneur Quotient: An International Perspective on Social Entrepreneur Personalities.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (3): 265–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541013

- Kalnins, Arturs. 2018. “Multicollinearity: How Common Factors Cause Type 1 Errors in Multivariate Regression.” Strategic Management Journal 39 (8): 2362–2385. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2783

- Kannampuzha, Merie, and Kai Hockerts. 2019. “Organizational Social Entrepreneurship: Scale Development and Validation.” Social Enterprise Journal 15 (3): 290–319. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-06-2018-0047

- Kaushik, Vineet, Shobha Tewari, Sreevas Sahasranamam, and Pradeep Kumar Hota. 2023. “Towards a Precise Understanding of Social Entrepreneurship: An Integrated Bibliometric–Machine Learning Based Review and Research Agenda.” Technological Forecasting and Social Change 191: 122516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2023.122516

- Keene, O. N. 1995. “The Log Transformation is Special.” Statistics in Medicine 14 (8): 811–819. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.4780140810

- Kemper, J., Engelen, A., and Brettel, M. 2011. "How Top Management's Social Capital Fosters the Development of Specialized Marketing Capabilities: A Cross-Cultural Comparison". Journal of International Marketing 19 (3): 87–112. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.19.3.87

- Kerlin, Janelle A., Saurabh A. Lall, Shuyang Peng, and Tracy Shicun Cui. 2021. “Institutional Intermediaries as Legitimizing Agents for Social Enterprise in China and India.” Public Management Review 23 (5): 731–753. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2020.1865441

- Klarin, Anton, and Yuliani Suseno. 2023. “An Integrative Literature Review of Social Entrepreneurship Research: Mapping the Literature and Future Research Directions.” Business & Society 62 (3): 565–611. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503221101611

- Klarmann, Martin, and Sven Feurer. 2018. “Control Variables in Marketing Research.” Marketing ZFP 40 (2): 26–40. https://doi.org/10.15358/0344-1369-2018-2-26

- Ko, E. J., and K. Kim. 2020. “Connecting Founder Social Identity with Social Entrepreneurial Intentions.” Social Enterprise Journal 16 (4): 403–429. https://doi.org/10.1108/SEJ-02-2020-0012

- Kruse, P., D. Wach, S. Costa, and J. A. Moriano. 2019. “Values Matter, Don’t They?–Combining Theory of Planned Behavior and Personal Values as Predictors of Social Entrepreneurial Intention.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (1): 55–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541003

- Kruse, P., E. M. Chipeta, J. Surujlal, and J. Wegge. 2023. “Development and Validation of a New Social Entrepreneurial Intention Scale in South Africa and Germany.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 14: 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2023.2205419

- Kusa, R., and K. Dębkowska. 2022. “Identifying Internationalisation Profiles of Social Entrepreneurs Utilising Multidimensional Statistical Analysis.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 13 (1): 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2020.1751246

- Leary, Mark R., Kristine M. Kelly, Catherine A. Cottrell, and Lisa S. Schreindorfer. 2013. “Construct Validity of the Need to Belong Scale: Mapping the Nomological Network.” Journal of Personality Assessment 95 (6): 610–624. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.819511

- Lee, B., and L. Kelly. 2019. “Cultural Leadership Ideals and Social Entrepreneurship: An International Study.” Journal of Social Entrepreneurship 10 (1): 108–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/19420676.2018.1541005