Abstract

Our multi-disciplinary research team explored the experiences and concerns of Latino/a students and their parents related to being welcomed and included in Catholic high schools in a United States diocese. We collected both qualitative and quantitative data in order to create a fuller picture of Latino/a experiences in these high schools. We make recommendations based on our findings to advance the scholarship on best practices for including students of new demographic groups in Catholic high schools with a specific focus on welcoming and including Latino and Latina students in Catholic high schools.

Introduction

Why are so few Latino/aFootnote1 students enrolled in our Catholic high schools? This was the question that was brought to us by our community partner, a Catholic diocese in the United States of America. As we began to review the existing literature and the research already completed on Latino/a enrolment and participation in Catholic schools, we realised that the proposed study was definitely needed, not only to assist our community partner, but also to contribute to the developing body of research on how to invite more Latino/a participation in Catholic education in the United States.

Literature review

While controversial among both scholars and practitioners, evidence continues to emerge of a Catholic school advantage for racially and socio-economically diverse students in United States PK-12 schools (Corpora and Fraga Citation2016). In a recent study, Fleming et al. (Citation2018) discovered that minority students and students from low-income households who had attended Catholic high schools had higher levels of success in a four-year public university than students who attended other types of high schools. The data for this study were drawn from ‘the educational performance of students at a large public university [in the United States] who entered as freshmen between the fall of 2000 and the fall of 2008. The entire dataset includes 45,728 students’ (p. 2 and p. 9).

The researchers who conducted this study were cognizant of the age-old controversy that surrounds research suggesting that there is a Catholic school advantage for particular groups of students. Therefore, Fleming et al. controlled for a possible selection bias in school enrolment choices by including a number of student variables in their regression analysis, for example, household income, race, sex, and United States college entrance exam score.Footnote2 Even with these controlling variables factored into their regression analysis, the researchers still discovered that graduates of Catholic high schools had an advantage over graduates of other types of high schools in cumulative college grade point average, likelihood of graduating from college, and likelihood of graduating from college in four years. Therefore, the research by Fleming et al. (Citation2018) indicates that Catholic schools are exactly the right schools for students from different cultural groups, including Latino/a students, who need a leg up as they rise to adulthood.

Statistics on Latino/a church and school participation

Latino/a stakeholders, once a numerical minority in the Catholic Church in the United States, are on the way to becoming a numerical majority in the Church (Ospino and Weitzel-O’Neill Citation2016). For example, in a study of religious identity in the United States, researchers noted that 52% of Catholics under the age of 30 were Latino/a (Cox and Jones Citation2017). Latinos are now seen as the future strength and hope of the Catholic Church in the United States (Crary Citation2020; Ospino Citation2017; Paulson Citation2014).

Despite the rapid growth of the Latino/a population in the United States Catholic Church, Latino/a students are under-represented in Catholic schools in the United States. According to the National Center for Education Statistics (Citation2021), just 301,090 Hispanic school-age-students were enrolled in Catholic schools in the fall of 2019, making up 17.3% of the student population in Catholic schools. At the same time, 14 million Hispanic students were enrolled in public schools and made up 28% of the public-school student population.

Welcoming Latino/a students in Catholic schools

It takes a conscious and sustained effort by school stakeholders to ensure that a new demographic group will feel welcome within a school community (Arellanes Citation2020; Mears Citation2020). School personnel need to learn about the importance of understanding a new culture and inviting a new group of students and families to share their culture with the school community (Arellanes Citation2020; Lichon et al. Citation2020). A big step in the learning process occurs when school staff and leaders welcome cultural diversity and bilingualism in their school as a resource and an advantage rather than perceiving a new culture and a new language as a problem (Nieto Citation2010).

Effective cultural inclusion is driven by the motivation of stakeholders to make inclusion happen (Arellanes Citation2020; Mears Citation2020). Professional development for staff and instruction for students can be developed that enables everyone in a school to see the value of different cultures and languages as a way to understand more fully what it means to be human (Lichon et al. Citation2020; Mears Citation2020). Finding ways to discover student and family talents and strengths and then inviting them to share these strengths with the school community is one example of how to work towards an inclusive school culture (González et al. Citation2005). By acknowledging that a new demographic group brings new gifts and talents to a school community, students from a new culture perceive that they are bringing something of value into the school (Mears Citation2020).

Ospino and Weitzel-O’Neill conducted a survey of Catholic high school staff in the United States to explore the steps the schools had taken to intentionally welcome Latino/a students and families (N = 656 schools, response rate = 44%). School leaders reported displaying culturally diverse and inclusive symbols (25%), posting signs in Spanish and English (21%), including Spanish in school liturgies (36%), and integrating Latino/a culture in school liturgies (60%). School leaders also noted that they had developed specialised programmes for students who spoke Spanish at home (58%). Ospino and Weitzel-O’Neill noted that increasing the number of Latino/a staff members in a school can be another way to enhance Latino/a student and family feelings of welcome and inclusion. At the same time, Ospino and Weitzel-O’Neill (Citation2016) discovered that only 7% of Catholic school teachers who responded to their survey self-identified as Hispanic, and only 14% of principals self-identified as Hispanic. In a more recent census of Catholic dioceses, Smith and Huber (Citation2022) found that the percentage of teachers in Catholic schools who were Hispanic remained low: 9.6% of Catholic elementary school teachers were Hispanic and 9.1% of Catholic secondary school teachers were Hispanic compared to the 17.3% of students in Catholic schools who were Hispanic (National Center for Education Statistics Citation2021).

Corpora and Fraga (Citation2016) shared additional recommendations for ways that Catholic schools could be more welcoming and inclusive of Latino/a students and their families. Their recommendations included having a fluent Spanish speaker in the main office and developing trusting relationships with key leaders in the local Latino/a community.

Language as a bridge and barrier to school/family relationships

Positive relationships between school staff and families can help to support student success in school (Arellanes Citation2020; Lichon et al. Citation2020; Ospino and Weitzel-O’Neill Citation2016). Bilingual staff members can play an important role in developing positive relationships between the school and families (Arellanes Citation2020; Lichon et al. Citation2020). However, language barriers between families and school personnel were noted as being problematic in the national survey of Catholic school staff conducted by Ospino and Weitzel-O’Neill (Citation2016). Similarly, Valdés (Citation1996) noted that families whose first language was Spanish tended not to participate in school meetings and activities if school personnel did not engage parents in Spanish.

Need for this study

While the literature and studies we reviewed indicated that Catholic schools would be ideal places for Latino/a students to learn and grow, additional research we reviewed demonstrated that the number of Latino/a students attending Catholic schools was low compared to the number of Latino/a students attending public schools in the United States. Therefore, in addition to addressing specific concerns of our community partner around the welcome and inclusion of Latino/a students in their Catholic high schools, we also were interested more generally in understanding the institutional and social structures that would encourage Latino/a enrolment in schools that would likely be beneficial for them and their communities.

Research questions

We developed two research questions to guide our investigation of Latino/a student experiences in the eight Catholic high schools that participated in our study.

(Question 1) What are the experiences of Latino/a students in the eight Catholic high schools being studied?

(Question 2) What action steps, if any, could be taken by educators to better welcome and include Latino/a students in Catholic high schools?

Data collection and findings

As researchers invited to explore the experiences of Latino/a students in eight Catholic high schools in one diocese, we wanted to use a methodology that would be rigorous yet sensitive to the experiences of our participants. For these reasons, we decided to use a mixed methods exploratory sequential research design. The qualitative data collection strategies we used allowed us to listen carefully to the voices of participants in our study. The quantitative data collection strategy we used allowed us to increase the sample size of our participants and to use triangulationFootnote3 to evaluate the accuracy of our findings. The sequential design allowed us to develop valid items based on the qualitative portion of our study that we used with participants in the quantitative portion of our study.

The interdisciplinary nature of our research team, with faculty from the departments of education and cultural anthropology, provided a collaborative multidimensional approach that allowed us to see the key aspects of this study from a variety of angles and points of view. By including the assistant superintendentFootnote4 from our community partner on our research team, as well as a student completing a degree at our university, we broadened the perspective of our team even further. We ensured that we followed ethical guidelines in our methods through use of the human subjects research review process at our university.

The experiences of Latino/a students in the Catholic schools we studied were documented using a two-stage process. An explanation of the two stages of our study and related findings follow.

Focus group and interview qualitative data collection

Following recommendations for research aimed at promoting social justice, we first conducted focus groups and interviews in order to prioritise participant voices (Fassinger and Morrow Citation2013). We developed a sampling frame in order to include students and parents from all eight participating schools, to balance male and female participants, and to select participants who had a mix of positive and negative experiences in the schools. Our stakeholder partner (assistant superintendent working with Latino students and families) assisted us with the purposeful sampling process by recruiting students and parents to participate in focus groups through email invitations, telephone invitations, and face-to-face meetings using a script. The script was translated into Spanish and used with parents whose first language was Spanish.

Focus group and interview questions were developed by the members of our research team in collaboration with our community partner (). The members of our research team all had experience teaching and leading in P-12 Catholic schools, and some members of our research team also had experience working with Latino/a students. These factors enabled us to develop valid focus group and interview questions, while also ensuring that each question was open-ended to allow us to hear the voices and experiences of our participants.

Table 1. Focus group questions used in this study with Latino/a students.

Table 2. Focus group questions used in this study with Latino/a parents.

Table 3. Structured interview questions used with Latino/a students in this study.

Participants all gathered in one location over the course of a week in spring 2021 to participate in focus groups. Focus groups were 60–90 min in duration. Three Latino/a student focus groups were each facilitated by two members of our research team in English (total student N = 17). Two Latino/a parent focus groups were each facilitated by two members of our research team in Spanish (total parent N = 9). We used audio recording devices to preserve the data from the focus groups.

Researchers facilitating the focus groups selected six Latino/a students to participate in individual structured interviews to further explore their experiences. Students were selected based upon the quality of their participation in the focus groups and the variety of experiences that they shared in the focus groups. We also interviewed one student who wanted to participate in our research study but was not comfortable participating in a focus group. The interviews were 45–60 min in duration and audio recordings were created during the sessions.

Transcripts of focus groups and interviews were created from audio recordings using Trint, an online application, and transcripts were translated from Spanish to English when necessary. A member of our research team reviewed each transcript while listening to the audio recording to correct any inaccuracies in mechanical transcription or researcher translation from Spanish to English. The corrected transcripts were analysed using the Grounded Theory approach (Glaser Citation1992) and NVivo software. This analysis resulted in the formulation of codes to represent topics consistently discussed in the focus groups and interviews.

Individual codes were organised into themed groups. The themes were validated when the researcher who organised the themes sought consensus on the themes from the other members of the research team who had conducted the focus groups and interviews.

Focus group and interview qualitative findings

Five themes emerged from the focus group and interview data (). First, Latino/a students consistently noted that they needed more help and guidance throughout their first year of high school. Second, Latino/a students shared that they appreciated it when school personnel took the initiative and ‘checked-in’ with them. As a result of these check-ins, faculty learned of student concerns and were able to assist students and students felt cared for and respected. Third, both students and parents stated that it was helpful when there was a Spanish speaker on the school staff who could communicate with parents in Spanish. Students felt that parents whose first language was Spanish were unable to fully understand their experiences in school without the assistance of a Spanish-speaking staff member.

Table 4. Principal themes identified in focus group and interview data.

The fourth theme that emerged from focus groups and interviews was that Latino/a students heard other students and some teachers in their schools make culturally insensitive comments. While these comments were not necessarily directed to the Latino/a students, these insensitive comments did make the Latino/a students feel less welcome and less integrated in their schools. The fifth and final theme based on focus group and interview data was that culturally focused student groups, activities, and events at the schools aided the Latino/a students in feeling welcomed and integrated within their schools.

Group concept mapping quantitative data collection

Based on the five consistent themes and associated codes identified within the focus group and interview data, we developed 32 statements that represented the themes (). These statements were entered into the cloud-based Group Wisdom application that supports the group concept mapping research methodology. Students sorted and rated the statements and Group Wisdom generated point maps based on student data that we used for data analysis. One of the distinct advantages of the group concept mapping research methodology is that it emphasises collaborative and participatory research practices and prioritises participants’ shared perceptions and ideas in order to inform changes in structures and practices (Kane and Trochum Citation2007).

Table 5. Group concept mapping statements developed based on focus group and interview data.

Data was collected in the late fall of 2021 by providing all the Latino/a students in the schools participating in this study with an opportunity to complete the group concept mapping activities (N = 340 Latino/a students in all eight schools). Students received an invitation email with a web link inviting them to participate in the activities. Emails were either sent to the students directly by our research team or via the principal of their school. When students began the online activity, they were asked to answer demographic questions. Next, students were asked to sort the 32 statements in Group Wisdom into groups by theme. Once statements were sorted, students rated the statements.

Of the 340 students invited to participate in the group concept mapping activities, 37% (N = 125) responded to at least some of the demographic questions. The students self-identified as 78% female (N = 97), 20% male (N = 25), and 2% non-binary (N = 3). Students reported attending seven of the eight schools participating in this study, as students from one school did not participate in the second stage of our study.

Of the 340 students invited to participate in our study, an average of 62 or 18% of the Latino/a students rated statements. The range of students rating statements was between 37 and 69 across the 32 different statements. Latino/a students rated statements according to how true a statement was for their school and according to how important they thought it was for their school to address the topic, for example, students rated how important they thought it was for personnel in their schools to address culturally insensitive comments made by others at the schools.

Group concept mapping quantitative findings

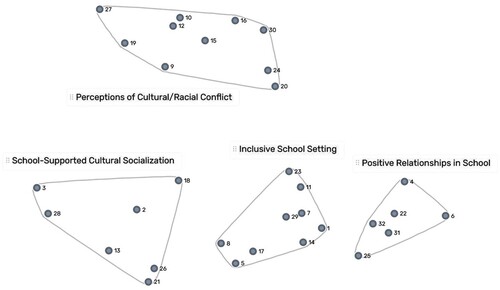

Group Wisdom’s statistical algorithm, multidimensional scaling, was used to create a two-dimensional point map depicting how students sorted the 32 statements related to perceptions of inclusion or exclusion in a school (). Points that are close together on the map indicate that students thought a group of statements were thematically related.

Figure 1. Point sorting map with cluster overlay. Notes: The numbered points on this map represent the 32 statements that Latino/a students sorted into groups. Group Wisdom Software, through the use of a statistical algorithm, produced the four clusters represented by the outlined shapes. Our research team named each cluster according to the themes of the statements in each cluster. Statement 20 was, ‘Teachers and administrators are sensitive to divisive topics’. Latino/a students included this statement with others in the cluster we named ‘Perceptions of Cultural/Racial Conflict’. All of the other statements in the conflict cluster represent subtle and more overt forms of conflictual behaviour, while statement 20 represents an awareness about what might lead to conflict.

Another analytical function within Group Wisdom, hierarchical clustering, enabled us to overlay shapes or cluster groups onto the point map. We created labels for the clusters based on a review of the statements that were now included within the clusters on the map. The clusters represent the variety of ways Latino students might perceive the atmosphere in a school, including perceptions of conflict and alienation and perceptions of harmony and inclusion.

At the top of is the themed cluster: Latino/a student perceptions of cultural and racial conflict in a school. The individual statements in this cluster focus on feeling alone, misunderstood, and excluded. The three themed clusters at the bottom of can be grouped under the general heading: Latino/a student perceptions of cultural and racial harmony in a school. The cluster at the top and the three clusters at the bottom of the point map in clearly represent two different types of school environments.

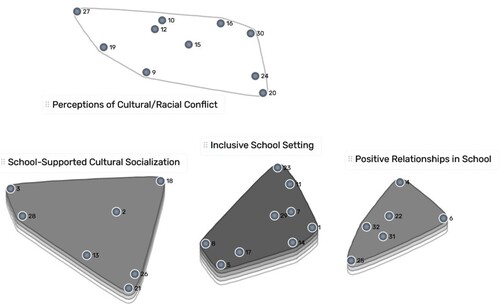

After Latino/a students had sorted the 32 statements, the students rated the statements. First, the students rated how true each statement was for their own school, sharing what the experience of Latino/a students was like in these schools. Students gave higher ratings to statements in the lower half of the point map (), as indicated by the number of layers in each cluster. A higher number of layers indicates higher ratings of the items in that cluster by students. The point map in , then, demonstrates that the students in this study thought their schools were less conflicted and more understanding and inclusive of different cultures and races.

Figure 2. Point rating map with cluster overlay: How true at my school. Notes: The numbered points in this figure represent the 32 statements that Latino/a students rated on a four-point scale (1-not true for my school – 4-very true for my school). The clusters represented by the shapes include statements with similar themes, and our research team named each cluster. The layers in the lower clusters indicate that Latino/a students rated topics in these themed clusters as truer of their schools than the cluster at the top of the figure, indicating that the Latino/a students in this study experienced their schools to be more supportive and less conflicted around culture and race. Layer Scale: one-layer (perceptions of cultural/racial conflict) = 2.24–2.41, three-layers (school-supported cultural socialisation and positive relationships in schools) = 2.60–2.76, four-layers (inclusive school setting) = 2.77–2.94.

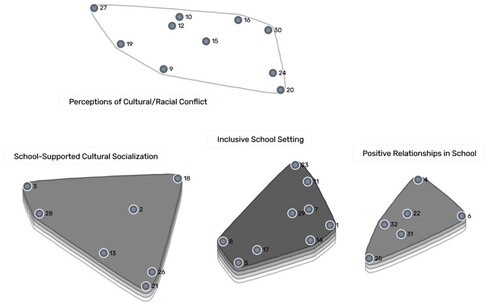

When Latino/a students rated the 32 statements according to which topics were most important for their schools to address, they again gave higher ratings to those items at the bottom of the point map (), focusing on enhancing already existing inclusive practices and relationships to build more cultural and racial harmony.

Figure 3. Point rating map with cluster overlay: How important to address at my school. Notes: The numbered points in this figure represent the 32 statements that Latino/a students rated on a four-point scale (1-not important to address at my school – 4-very important to address at my school). The clusters represented by the shapes include statements with similar themes, and our research team named each cluster. The layers in the lower clusters indicate that Latino/a students rated topics in these themed clusters as more important to be addressed than the cluster at the top of the figure, indicating that the Latino/a students in this study thought it was more important to enhance positive programmes and initiatives in the schools related to building inclusive community than it was to address subtle and somewhat overt forms of conflictual behaviour. Layer Scale: one-layer (perceptions of cultural/racial conflict) = 2.65–2.80, three-layers (school-supported cultural socialisation and positive relationships in schools) = 2.95–3.09, four-layers (inclusive school setting) = 3.10–3.23.

Mixed methods findings based on triangulation of data points

While the Latino/a student completion rate for the group concept mapping activities was low (18%, N = 62/340),Footnote5 their ratings provided important additional information about the experiences and hopes of Latino/a students in the Catholic high schools we studied. By triangulating data from the group concept mapping activities with data from the focus groups and interviews, we were able to determine which issues were consistently mentioned by Latino students and parents related to inclusion or exclusion in the Catholic high schools participating in our study ().

Table 6. Triangulation of data from group concept mapping, focus groups, and interviews.

The triangulated data indicate that school leaders ought to address these action steps to better welcome and include Latino/a students in their schools:

Prioritise strategies for effective communication with Latino/a parents including hiring bilingual personnel.

Prioritise programmes for students that emphasise the value of cultural differences.

Expand current retreat programming to emphasise welcome to the school and inclusion in the Christian community at the school.

Expand the integration of symbols and celebrations of diverse cultures within the school building and schedule.

Provide ongoing professional development for all school personnel on how to connect with and support Latino students.

Theme #1 from the focus groups and interviews was not validated by the Group Wisdom data (). In focus groups and interviews, students stated that they received a great deal of help during the initial weeks of the school year, but then they felt that help vanished while they continued to need help throughout their first year of high school to be successful. There are a number of reasons why Theme #1 from the focus groups and interviews was not validated in the online activity as an important theme for educators in the schools to address. For example, we reviewed the 32 statements we created based on the focus group and interview data and decided that a statement with a clearer focus on Theme #1 could have been included in the set of statements students rated (). Additionally, the difference between data sets may have resulted from the differing experiences and viewpoints of the participants in each stage of this study.

A common theme in all three clusters at the bottom of the rating map focused on what students thought was important to address at their schools was the theme of friendship (). Latino/a students consistently noted that friendships with Latino/a and non-Latino/a students were very important for developing a culture of inclusion. The theme of friendship as important for feeling welcomed and included at school did not surface as a key theme in focus groups and interviews, and therefore, was not validated through triangulation as a consistent theme present in all three data sets. We did ask questions related to friends and friendships in the focus group and interview questions, so this difference in data sets is most likely due to group differences.

Recommendations

Based on the triangulated findings of this mixed methods study, we recommend that Catholic school leaders seeking to make their schools more welcoming to Latino/a students and families explore how to add or expand the number of Spanish speakers on staff who can communicate with Latino/a parents. These same Spanish-speaking staff members may also be able to develop enduring relationships with the broader Latino/a community.

Second, we recommend that Catholic school leaders develop and implement programmes to enhance all students’ sense of the value that different cultural groups bring to Catholic schools. Developing an attitude of both respect and appreciation for cultures will increase cultural and racial harmony in schools and will also prepare graduates to live and work in a multi-cultural community.

Third, we recommend that Catholic schools build on current student activities, including retreat programmes, that promote social integration and retention of Latino/a students. Our finding that retreat experiences were helpful for Latino/a students to feel integrated within their schools is not a finding that we noticed in our literature review. Therefore, the value of retreat experiences for inclusion is a new best practice in how to welcome and integrate Latino/a students in Catholic high schools.

The students participating in this study interpreted active check-ins by educators as signs of care and concern for them and so our fourth recommendation is that Catholic schools build on current strengths to enhance administrator and educator connections with Latino/a students. Our finding that Latino/a students appreciate check-ins with them by administrators, counsellors, and teachers was not a best practice we identified in our literature review, and this finding is also a new best practice in how to welcome and include Latino/a students in Catholic schools.

Conclusions

The findings of this study confirm some findings of other studies related to the best ways to welcome and include Latino/a students and families in Catholic schools, especially the importance of having Spanish speakers on the school staff (Arellanes Citation2020; Corpora and Fraga Citation2016; Lichon et al. Citation2020; Ospino and Weitzel-O’Neill Citation2016; Valdés Citation1996). At the same time, our findings also point out new best practices that can inform how Catholic schools welcome and include Latino/a students and families. Looking toward possible future research in this area, we recommend three lines of inquiry.

First, we recommend that longitudinal studies be undertaken to gauge the impact of interventions on the experiences of Latino/a students and families. Second, we recommend further study on the role of retreats in assisting the integration of Latino/a students into the school community. Finally, we recommend further study on the effect of active educator check-ins on Latino/a students’ feelings of welcome and inclusion within Catholic schools.

In generations past, Catholic schools in the United States were effective in providing safe and culturally appropriate educational experiences for Catholic students and their families. Now, Latino/a students and their families are one of the new cultural groups that Catholic schools could serve. Active efforts must be taken to ensure that Catholic schools are responsive to the needs of this essential but often marginalised stakeholder group. By taking intentional research-based steps to attend to the integration of Latino/a students and families in Catholic schools, school leaders and teachers will make great strides in securing a bright future for Catholic education in the United States and will assist a new generation of culturally diverse students with becoming leaders in our Church, our nation, and in our world.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Thomas Simonds

Thomas Simonds, SJ, EdD is Professor of Education.

Carin Appleget

Carin Appleget, PhD is Assistant Professor of Education.

Timothy Cook

Timothy Cook, PhD is Professor of Education.

Ronald Fussell

Ronald Fussell, EdD is Associate Professor of Education.

Kelsey Philippe

Kelsey Philippe, BS, is now a graduate from Creighton University’s teacher education programme and was the study’s student researcher.

Alexander Rödlach

Alexander Rödlach, SVD, PhD is Professor of Medical Anthropology.

Renzo Rosales

Renzo Rosales, SJ, PhD is Assistant Professor of Cultural Anthropology.

Notes

1 Latino refers to anyone from Central America or the Caribbean and is a broader term as it groups people according to a geographic region of the world rather than according to a language group. The term Hispanic refers to a person who speaks Spanish or has a Spanish-speaking heritage. Therefore, we chose to use the broader term, Latino, in this article. We also chose to use Latino/a in this article instead of Latino or Latinx. We made this decision after discussion with Spanish-speaking members of our research team and our local community partner in order to follow the natural flow of the Spanish language and to emphasize that we are referring to both male and female students with roots in Central America and the Caribbean.

2 In the United States of America, high school students have traditionally taken a college entrance exam. Some colleges and universities have required the ACT, while others have required the SAT exam. In recent years, colleges and universities in the United States have begun making entrance exam scores optional.

3 Triangulation is a strategy used in qualitative and mixed methods research to evaluate the accuracy of the data. When we see three different data points converging on the same finding, then we can trust the conclusion with a higher degree of certainty. When describing validity, the image of darts all landing in the bullseye on a dartboard is often used. This same image is a helpful way to understand the concept of triangulation.

4 In the United States, public school systems are typically led by a superintendent of schools, who oversees all the schools within the system. Most Catholic (arch)dioceses have taken on a similar model, assigning a superintendent to attend to the needs of the Catholic schools in the system or diocese. An assistant superintendent supports the superintendent in a specific dimension of school system operations, in this case, Latino/a family outreach.

5 The Latino/a student completion rate varied across the 32 statements that were rated. The average completion rate was 62/340 or 18%. The range of completion was between 37 and 69 students.

References

- Arellanes, B. 2020. “The ‘Snap Minority’ 50 Years Later.” Momentum, Winter 2020. Accessed 7 August 2022. https://read.nxtbook.com/ncea/momentum/winter_2020/the_snap_minority_50_years_la.html.

- Corpora, F.V., and L.R. Fraga. 2016. “¿Es Su Escuela Nuestra Escuela? Latino Access to Catholic Schools.” Journal of Catholic Education 19 (2): 112–139. doi:10.15365/joce.1902062016.

- Cox, D., and R. Jones. 2017. America’s Changing Religious Identity. Washington, DC: Public Religion Research Institute.

- Crary, D. 2020. “US Hispanic Catholics Are Future, but Priest Numbers Dismal.” AP News, 14 March. Accessed 7 August 2022. https://apnews.com/article/0cd91a02ad1bfe947d77c3e1a2c313a8.

- Fassinger, R., and S.L. Morrow. 2013. “Toward Best Practices in Quantitative, Qualitative, and Mixed-Method Research: A Social Justice Perspective.” Journal for Social Action in Counseling & Psychology 5 (2): 69–83. doi:10.33043/JSACP.5.2.69-83.

- Fleming, D.J., S. Lavertu, and W. Crawford. 2018. “High School Options and Post-Secondary Student Success: The Catholic School Advantage.” Journal of Catholic Education 21 (2): 1–25. doi:10.15365/joce.2102012018.

- Glaser, B. 1992. Basics of Grounded Theory Analysis. Mill Valley: Sociology Press.

- González, N., L.C. Moll, and C. Amanti. 2005. Funds of Knowledge: Theorizing Practices in Households, Communities, and Classrooms. New York: Routledge.

- Kane, M., and W.K. Trochum. 2007. Concept Mapping for Planning and Evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Lichon, K., J. Dees, C. Roach, and I. Moreno. 2020. “Serving English Learners in Catholic Education.” Momentum, Winter 2020. Accessed 7 August 2022. https://read.nxtbook.com/ncea/momentum/winter_2020/serving_english_learners_in_c.html.

- Mears, K. 2020. “Catholic Schools Can Help Bridge the Racial Divide.” Momentum, Summer 2020. Accessed 7 August 2022. https://read.nxtbook.com/ncea/momentum/summer_2020/archives.html.

- National Center for Education Statistics. 2021. Digest of Education Statistics. Accessed 15 April 2022. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d21/tables/dt21_205.40.asp.

- Nieto, S. 2010. “Language, Diversity, and Learning: Lessons for Education in the 21st Century.” CAL Digest, August 2010, 1–4. Accessed 7 August 2022. https://eclass.upatras.gr/modules/document/file.php/PDE1439/language-diversity-and-learning.pdf.

- Ospino, H. 2017. “10 Ways Hispanics Are Redefining American Catholicism in the 21st Century.” America, 30 October. Accessed 7 August 2022. https://www.americamagazine.org/faith/2017/10/30/10-ways-hispanics-are-redefining-american-Catholicism-21st-century.

- Ospino, H., and P. Weitzel-O’Neill. 2016. Catholic Schools in an Increasingly Hispanic Church: A Summary Report of Findings from the National Survey of Catholic Schools Serving Hispanic Families. Chestnut Hill: Boston College.

- Paulson, M. 2014. Hispanic Growth Is Strength but Also Challenge for U.S. Catholic Church.” The New York Times, 5 May. Accessed 12 December 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/05/06/upshot/hispanic-growth-is-strength-but-also-challenge-for-Us-catholic-church.html.

- Smith, A., and S. Huber. 2022. United States Catholic Elementary and Secondary Schools 2021-2022. The Annual Statistical Report on Schools, Enrollment, and Staffing. Arlington: National Catholic Educational Association.

- Valdés, G. 1996. Con Respeto: Bridging the Distance Between Culturally Diverse Families and Schools. New York: Teachers College Press.