Abstract

The place of Church school headteachers as spiritual leaders of the school community is rarely highlighted. This article investigates how 13 Church primary school headteachers (Catholic Church of England, and Methodist) interpret this role. It draws on the Faith in the Nexus research which investigated how church primary schools nurtured pupils’ spiritual development and facilitated faith activity in the home. The head teacher interviews revealed several recurring themes, such as empowering children, collective worship, relationships with church and parents, and the visibility of faith in school. This research brings together a comparison of leadership approaches from Catholic and Anglican headteachers. Evidence of differences emerged; Catholic headteachers tended to use ‘overtly religious’ language while many Anglican headteachers employed a more ‘secular’ language to express their vision of spiritual leadership. A comparison with Shaw’s (Citation2015, 2017) model of ‘ethotic leadership’, highlighted much in common. The headteachers’ ethos was pupil-centric and shaped by a focus on the spiritual development of the child. An adaptation of Shaw’s model is offered which places the child at the centre.

1. Introduction

More than one third of the UK’s state-funded schools are faith-based schools and almost 30% of primary school children in Britain attend a school with a religious character, most of these schools are Church schools founded by one of the Christian denominationsFootnote1 (Long and Danechi Citation2019). A Church school is defined as a school with a church foundation, not all pupils will necessarily identify as Christian. There are various types of Church schools in England, some of which have faith, as expressed in initiation rites or church attendance, as an admission criterion. There are further distinctions on governance, whether schools are voluntary aided (VA), where the Church has a substantial influence in the running of the school or voluntary controlled (VC), where the church has more limited formal influence in the running of the school. In addition, Academy schools are schools run by the Church or a diocesan sponsored multi-academy trust, or a local or national non-faith based multi academy trust (Long and Danechi Citation2019).

Aside from their main task of providing an academic education for children, these schools offer an environment to nurture spiritual development, in a society where only a tiny minority attends church services regularly (Woodhead, Citation2012). The 2001 Dearing Report and the 2016 Vision for Education stressed that for the Church of England, the Church schools’ key role is to stand ‘at the centre of the Church’s mission to the nation’ (General Synod Citation2001, xi, Johnson Citation2003, 473–474; Church of England Citation2016, 2). The Roman Catholic Church regards its involvement in education as a vital part of the mission of the Church (Catholic Education Service Citation2014, 1). However, the Roman Catholic Church’s formulation of the purpose of Church schools differs from that of the Church of England as for the Catholic Church focus is on maintaining a distinctly Catholic identity of Church schools and providing education for Catholic children.

Existing studies of Church schools often focus on one specific denomination, Catholic (Grace, Citation2009; Whittle Citation2018; Casson Citation2018) or Anglican (Chadwick Citation2001; Jelfs Citation2010; Worsley Citation2012). The Faith in the Nexus research (Casson et al. Citation2020) is unique and significant in that it enables a comparison of leadership approaches from church primary headteachers within the two discrete traditions. Building on previous research, this article investigates how Church school headteachers perceive their own and their school’s role regarding the spiritual development of children. The three main questions underpinning this research are as follows: How do headteachers perceive and portray their own and their school’s role in facilitating children’s exploration of faith? How do headteachers describe their own and their school’s relationship with their faith community? What discourse do headteachers employ to express their vision for a school culture that fosters spiritual growth?

Church schools, and therefore their headteachers, face significant challenges in contemporary, increasingly secular, British society. One strand of research has made a significant contribution towards understanding the context of Church schools and the role and attitudes of the headteachers (Johnson Citation2002; Johnson and McCreery Citation1999; Johnson, McCreery, and Castelli Citation2000; Fincham Citation2010; Lumb Citation2014; Wilkin, Citation2014). These studies illuminate the challenges Anglican and Catholic schools face concerning the spiritual development of pupils in today’s multi-faith and largely secular society, providing valuable insights in understanding the Church schools’ and the headteachers’ role in this endeavour. Fincham (Citation2010) focuses on the challenges Catholic headteachers are faced with in England, while Lumb (Citation2014) addresses the specific difficulties Church of England schools face in the field of tension between the requirements of the Church (cf. SIAMS) and the State (cf. Ofsted). Shaw (Citation2015) analysed the leadership of voluntary aided schools (Jewish, Catholic, and Anglican) from the perspective of headteachers. He developed an ‘ethotic leadership’ model, identifying leadership styles informed by a personal faith journey, and developed in interaction with key stakeholders, underpinned by vision, values, and influence (Citation2017, 101). This will be explored in greater detail in section 2 of this paper and will be critically evaluated and developed further in section 4. The following section will address the context and challenges faced by Church schools.

2. Context and challenges

Beyond the common challenges which all schools in England and their leaders face today, such as assessment pressures and socio-economic problems of pupils, Church schools find themselves in a quite distinct context. Two of the main aspects that characterise the situation of Church schools in England are an increasingly secular society and the dual system of church and state (Grace Citation2000; Johnson Citation2003).

2.1. Decline of Church membership

One of the most remarkable aspects of Church schools in the UK today is that while church membership has declined steadily over the last decades, Church schools remain popular. For example, there are 1660 Catholic primary schools in EnglandFootnote2 and 4,644 Church of England primary schools, which make up a quarter of all primary schools in England.Footnote3 There are multiple consequences for Church schools of this disparity between declining church membership and the continued popularity of Church schooling. One impact is that Church school parents are not necessarily involved with a Christian community or parish in other ways (Rymarz and Belmonte, Citation2019). Elshof (Citation2019), in his study of parental expectations of Catholic schools in the Netherlands, attests that only a minority of the Catholic school parents were involved with the Church. Even though they might not be personally involved with a faith community, those parents, nevertheless, have chosen to send their child to a Church school. Moreover, Church school headteachers may find themselves in a situation in wider society where the very notion of a school that has ties to religion is contested. Therefore, they must navigate their daily tasks within the ‘dynamic interaction between secular and religious influences’ (Rymarz and Belmonte, 2019, p. 126). This interaction between the secular and the religious becomes even more explicit regarding the demands and expectations placed on a Church school in the dual system of church and state, as will be explored in section 2.2. The decline of church membership and religious practice in society also encompasses teachers. Teachers and even headteachers working in Church schools are not necessarily church community members or share the same vision. It is significant that while headteachers in Roman Catholic Church schools must be practising Christians within their faith community, the Church of England does not have the exact requirement for its headteachers (Fincham Citation2010, 65).

The decline of a ‘thick-Christian culture’ (to adapt Casson’s phrase of the ‘thick-Catholic culture’, Citation2018, 59–60) represents a challenge to Church school headteachers on many levels regarding relationships with wider society, their pupils, and the pupils’ parents as well as regarding their relationship to church and faith/religious practice.

2.2. Dual system of Church and state

Schools in England are not only exposed to underlying societal expectations and assumptions, but they are also required to meet explicitly defined standards regarding the education of children. The Office for Standards in Education (Ofsted) provides specific guidelines for the nation’s schools. Its School Inspection Handbook clearly states that inspectors will focus primarily on the quality of education. However, in the case of Church schools, the schools have parallel responsibilities towards the state and the church which can lead to tensions (Lumb Citation2014). The SIAMSFootnote4 inspections and the diocesan Roman Catholic inspections, which take place according to section 48 of the 2005 Education Act,Footnote5 concentrate on the Christian distinctiveness of Church schools and emphasise the religious and spiritual element of Church school education. In contrast, children’s spirituality is not one of the main concerns of the Ofsted inspections. The handbook only briefly mentions children’s spiritual development in the section on ‘Pupils’ wider development’, which says: ‘Inspectors will consider … whether the school’s work to enhance pupils’ spiritual, moral, social, and cultural development is of a high quality.’ (Ofsted Citation2021). Church school (head)teachers must negotiate the demands of both the Ofsted inspections, with their focus on academic performance, as well as ecclesiastical inspections, with their emphasis on Christian values and spirituality.

How headteachers perceive their leadership in the context of differing demands and their interaction with various stakeholders has been analysed by Shaw (Citation2015, Citation2017) in his work on leadership in voluntary aided schools. The following section briefly outlines his research and introduces his model of ‘ethotic leadership’.

3. Shaw’s model of ‘ethotic leadership’

In his research, Shaw (Citation2015, Citation2017) investigated 450 voluntary aided schools across England exploring headteachers’ perception of their leadership roles, the mixed-methods research included qualitative and quantitative surveys in Jewish, Catholic and Church of England schools. The study differed from others insofar as it was not restricted to Christian schools but included Jewish schools. It focused solely on voluntary aided schools (not including academies or voluntary controlled schools).

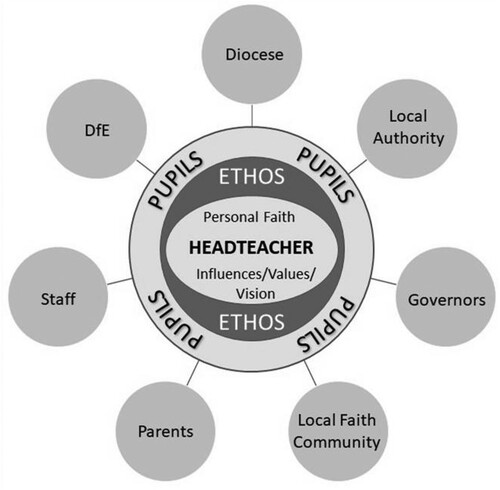

Shaw’s research showed a wide variety between the individual voluntary aided schools and further diversity in headteachers’ perceptions of their leadership role. Nevertheless, Shaw was able to identify a common leadership style between these leaders of Church schools and Jewish schools, which he named ‘ethotic leadership’. Ethotic refers to the influence on the shaping of leadership of the distinctive ethos that Shaw identified in the voluntary aided schools. The ‘ethotic leadership’ model depicts the headteacher as operating based on an underlying ethos, informed, or strengthened by their personal faith and demonstrating leadership characterised by vision, values, and influence (Shaw Citation2017, 101). From this individual position, the headteacher interacts with various stakeholders. The eight stakeholders identified by Shaw are: the pupils, parents, staff, the local faith community, governors, the local authority, the diocese, and the Department of Education.

Shaw’s model is insightful and valuable precisely because it considers the various stakeholders with which Church school headteachers interact. It illustrates that the headteacher does not operate and shape a school culture in a vacuum but is integrated in a network of agents. The Church school leadership model that Shaw developed earlier in the research process was augmented by the level of ‘ethos’ to form the final version of his ‘ethotic leadership’ model. He argued that this was ‘due to the significant role of the special ethos which envelops the headteachers of these schools and created by the combined efforts of the headteachers and the eight stakeholder groups with whom they interact’ (Shaw Citation2015, 156) ().

Figure 1. Shaw’s model of ‘ethotic leadership’ (Citation2015, 157).

In the next section an explanation of the Faith in the Nexus study methodology, is followed by a discussion of the findings. Common themes are identified in the interview material, alongside two basic strategies the Church school headteachers pursued. Section 5 brings Shaw’s model of ‘ethotic leadership’ into conversation with the results from the research study. Furthermore, based on the findings of this study, an amended model of ‘ethotic leadership’ will be proposed.

4. The research study

The Faith in the Nexus study (Casson et al. Citation2020), an interdenominational research project conducted in Church of England (and Methodist) and Catholic primary schools across England between 2018 and 2019, was carried out by the National Institute for Christian Education Research (NICER) based at Canterbury Christ Church University. The research focused on Church schools and children’s spiritual development, specifically the school’s role in facilitating children’s exploration of faith in the homeFootnote6The research analysis underlying this paper focused on the headteachers as they have a crucial role in shaping a specific school’s policy and thus potentially have a significant impact on individual children’s academic and spiritual development (Johnson, McCreery, and Castelli Citation2000, 393, 395–396; Fincham Citation2010, 69–73).

4.1. Methodology and research design

The Faith in the Nexus research (Casson et al. Citation2020) adopted a multi-site case study approach. The case study approach (Merriam Citation1998; Yin Citation2009), frequently used in qualitative research, is of value in educational research as it enables exploration of schooling in context. The sample was chosen through an appeal to Anglican and Catholic diocesan directors of education. Church primary schools who replied to the request, were sent further information about the nature of the research. A critical factor in the research design was that the researcher would work in partnership with the school. To this end the researcher visited each school to have a pre-research interview with the head teacher, explaining the nature of research in partnership. Head teachers acted as gatekeepers to other members of the school. Altogether, 20 church primary schools from across England were involved in the research (see ). All the schools were anonymised and given pseudonyms in publication. The university ethics committee scrutinised and approved the research application.

Table 1. School information.

The research employed a mixed-methods approach; qualitative semi-structured interviews were followed by a quantitative survey, which gave the research internal rigour and validity (Bryman Citation2004, 448). Semi-structured interviews enable the interviewees to share their stories (Cisneros-Puebla, Faux, and Mey Citation2004), allow interviewees to reflect, return to previous answers, to explore issues in depth. The interviewee has more control, than in fully structured interviews and the process appears more natural, more like a conversation. The research data collection took place in 2018–2019 (pre-Covid). Four hundred fifty four individuals (headteachers, parents, pupils, and other stakeholders, such as staff, governors, and clergy) participated in the semi-structured interviews. The online survey was completed by around 1000 persons (730 pupils and 272 adults). This article draws on semi-structured interviews with thirteen of the headteachers of three Catholic primary schools, seven Anglican voluntary aided schools, two academies and one voluntary controlled school. Seven of the twenty headteachers either chose not to participate in an interview or were unavailable at the time of the research.

Headteachers were prompted to elaborate on what happened in school to support children’s exploration of faith in the home. The interview questions did not explicitly ask headteachers about their leadership styles as it aimed to elicit a richer picture of Church school life that might have an impact on children’s spiritual development. Furthermore, this open approach allowed the headteachers to elaborate on what they perceived as important while avoiding the danger of eliciting pre-formulated answers to present headteachers themselves and their leadership style in a favourable light.

Interview questions included, for example, ‘What does faith mean in the context of this school?’, ‘What have you put in place in this school that encourages a child to explore that faith, spiritual dimension of life?’, ‘Which of those words (faith/spiritual) would you choose to use and what does it mean to you?’, ‘How would somebody coming into this school as a stranger know that it was a Church school?’ and ‘What is your (school’s) relationship with the church – how do you establish and maintain it?’. Interviews were recorded, transcribed, and coded with the data analysis software NVivo 11. A thematic analysis of the interviews (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) illuminated common themes and critical differences.

The following section discusses the analysis of the headteacher interviews, identifying some common themes and features in the language used by the headteachers, such as explicit reference to religious language or the church. Furthermore, the findings will be interpreted regarding Shaw’s model of ‘ethotic leadership’.

4.2. Discussion

4.2.1. Recurring themes

The interviews displayed some recurring themes as to what headteachers consider as important in their schools regarding the spiritual development of children. The most common themes are explored below:

4.2.2. Empowering children

Several headteachers explicitly stressed the importance of enabling children to be active themselves and explore faith and spirituality. This included giving children the opportunity to be educated about faith, to make decisions themselves and be allowed to shape spiritual elements of school life. This responsibility was reflected on by the headteacher of School 4 (CE/Ac) who said:

I think that having the responsibility within the Spiritual Council and the other elements as well, we have a Sports Council and School Council and various other chances for the children to share their ideas and take responsibility, … I think that has a very positive impact on them as individuals as well.

4.2.3. Collective worship, prayer, and reflection

The importance of collective worship, prayer and reflection was a further theme identified in the headteacher interviews. These are vital elements of daily life in the Church schools. The Anglican headteacher of School 4 expressed this very concisely: ‘It’s worship, and worship and worship. […] so, we worship, every day at the start’. While worship, prayer and reflection are an essential part of Church school culture, there was also significant variation between the various schools, particularly in the language used by the headteachers. The headteacher of a Catholic primary (School 1) stressed the importance of prayer in her school in these words:

And I think if we are a worshipping prayerful faith community where a faith is at the centre of what we do, and it guides our decision making. It just is everywhere. It’s in all the relationships, how we focus on forgiveness and understanding. We do pray. We pray a lot

4.2.4. Relationship with the local clergy and faith community

While some headteachers in the research project portrayed their (local) church community as vital for their school culture, other headteachers did not talk about their own or their school’s relationship with the local and wider church community. Many of the Church school headteachers interviewed also viewed the relationship with local clergy as particularly important regarding Church school life. Several of them reported a very positive and active relationship with their local priest or canon. In some schools the incumbent of the local church was almost a staple of school life. This involvement with the Church school often went well beyond delivering religious services. For example, the headteacher of a Catholic school (7) mentioned that their local priest was ‘often on the playground … just to talk to the parents and listen to the parents.’ While many schools had a very uncomplicated relationship with the local church, not all headteachers described the same positive experience. Some schools no longer had a local church community with which to engage. However, this did not prevent them from finding creative solutions to become involved with the wider faith community. After the church building connected to one Catholic primary (School 12) was closed, the headteacher decided to connect with a community of religious sisters nearby to enable the children to be involved with an active faith community. At the time of the interview, there was a positive and dynamic relationship between the school and the religious sisters, who acted as prayer partners for the children.

However, some other schools’ headteachers did not mention the local church community throughout their interview. This points to a significant variation concerning the relationship between Church schools and the local church community. The nature of this relationship affected how strongly headteachers perceive themselves and their schools as a part of their church community. Interestingly other factors such as size of school and the socio-economic context did not seem to show a clear picture regarding the relationship between the school community and church.

4.2.5. Relationships with the parents

A positive and engaging relationship between the Church school and the pupils’ parents and carers emerged as one pillar of a Church school culture that facilitated children’s spiritual development. One way in which this was achieved was by actively inviting parents and carers to participate in worship services within the school or local church. Inviting the parents to worship with the school community benefitted the children and the parents as well. This was highlighted, for example, by the headteacher of a Catholic primary (School 1), who said:

And I think that really, we celebrate it and we’re very happy they come. We open up our Liturgy, we open up loads and loads of opportunities for them to come and experience a positive faith.

4.2.6. Intentional visibility of faith in the school building

Another prominent feature that emerged from headteachers’ interviews about leading Church schools was the physical presence and visibility of faith or religious symbols in the school building. Of interest is that there was little explicit reference to the visibility of faith being modelled by the headteacher. Although deeper analysis of data revealed that some headteacher’s did have something akin to a ‘a sacramental vision of leadership’ as discussed in Lydon (Citation2011). This was not made as explicitly visible, as were the symbols in the building. Headteachers intentionally displayed Christian symbols from the entrance hall onwards. As the headteacher of School 16 (CE/VA) pointed out:

Well, hopefully as soon as you walk into our school you will see physical visual things that indicate we’re a Church school.

And children are given leaves, there’s a tree of return in the hall and all the children are familiar with that. That’s a school-wide initiative and the children are given leaves demonstrating the fruit of the Spirit. There’s a very clear distinction between ‘This shows the fruit of the Spirit' and academic rewards for stars and certificates for academic achievement. So, the children are very much aware that this is for their spiritual development.

4.2.7. (Christian) values and ethos

The headteacher interviews have shown that a pivotal aspect of Church school culture, encompassing all the recurring themes discussed above, is the orientation towards (not necessarily explicitly Christian) values and ethos. However, the values were often highlighted as Christian by the school and rooted in Biblical, or Church tradition. Ethos permeates the leadership of the headteachers, their management of the school and day-to-day school life. The headteacher of one school (School 17; CE and M-VA) described how in seeking to improve the school further, the leadership team decided to focus on a particular set of values and make them explicit in school life. Twelve values were identified that are rooted in the Biblical tradition and are now

lived every day and […] in [their] language every day […]. It’s the ethos, the language that is lived through and through

The importance of a pervading ethos that shapes a school culture and headteacher leadership has also been described by Shaw in his model of ‘ethotic leadership’ (2015 and 2017). It will be discussed again in section 5 of this article.

4.2.8. Language matters – ‘overtly religious’ language vs. more ‘secular’ language

A particular striking feature of the headteacher interviews was the varying degree of ‘overt religiosity’ of the language used. Some headteachers repeatedly used Christian vocabulary while others used a more ‘secular’ – possibly more inclusive – language. There were noticeable differences in the vocabulary used in the interviews. Some headteachers (for example, School 1, 7, 8) frequently used words that can be considered markers of ‘religious language’, such as Christian, Catholic, church, prayer, faith, parish, worship. Schools 1 and 7 were Catholic and School 8 was an urban Church of England voluntary aided school.

In contrast, a smaller number of headteachers (School 4 and 17) in the sample made only sparse use of these ‘overtly religious’ terms and used more ‘secular’, less ‘religious’ words instead. This became apparent, e.g. in the use of words like reflection, quiet and values. The reason attention was paid to these words is that it became evident that whereas some head teachers repeatedly mentioned ‘prayer’ as an essential part of school life (as well as ‘prayer time’, ‘prayer space’, etc.) others referred to more religiously neutral practices happening in their school which were ‘reflection space’ or ‘reflection time’ as well as ‘quiet space’ and ‘quiet time.’ The term ‘values’ is also not tied up with the Christian tradition.

As was already mentioned above, some schools’ headteachers very explicitly put an emphasis on prayer as part of their schools’ culture.

We do pray. We pray a lot. […] We have a lot of prayer activity going on which is some of it, optional and some of it given. (School 1, Ca-VA)

I think it probably is the reflection areas and the garden that has the strongest influence on them developing their spirituality and supporting their reflection.

4.2.9. Excursus: catholic and Church of England schools – differences

Differences can be seen emerging from the above analysis between Catholic schools and Church of England schools. The former was more homogenous than the latter in terms of the language used in the interviews. The headteachers of the Catholic schools invariably used overtly religious language, regardless of the socio-economic background of the schools’ intake, while the headteachers of the Church of England schools used a wider variety of language. Interestingly, the headteachers of Catholic schools stressed the schools’ identity as ‘Catholic’. For example, in the interview with the headteacher of School 1, the term ‘Catholic’ appeared fourteen times while the term ‘Christian’ was not used at all. Interestingly, in the three interviews with the headteachers of the Catholic schools, the term ‘Christian’ was mentioned only once. There are many contributing factors that can illuminate these differences. One factor is the underlying different approaches to the mission of a Church school, the Church of England’s vision of Church schools serving the local community, compared to Catholic schools for Catholic children. Another area which is indeed worthy of further research is the personal faith journey of the headteacher, Catholic headteachers are required to be practising Catholics, there is no equivalent expectation for Anglican heads. While some of the Anglican heads such as the head of School 8 openly shared their expression of faith and sense of a Christian vocation, several others did not. Further exploration is needed into how this personal faith journey shapes the Christian ethos, or the distinctively Christian vision of a Church school. Within the Catholic tradition, there is an understanding that a teacher’s ministry is modelled on that of Christ (Congregation for Catholic Education Citation1977). There is a need for empirical research into how that is expressed within a Catholic primary school. This leads into the third factor identified in the analysis, the nature of the school community. The language used in the context of a Catholic or Church of England school which has a majority of active Christian parents and pupils, will differ from a Church school which may serve a predominately non-Christian community. The difference in language highlighted in this analysis requires further research to illuminate the causes and the influence of overtly religious language on the school ethos.

4.2.10. Headteacher’ strategic use of language

As the analysis of the interviews has shown, some headteachers use explicitly or overtly ‘religious’ language while others use a more ‘secular’ language. Based on this one can argue that the headteachers follow two basic (distinct) strategies, which are (a) emphasising Christian values and distinctiveness as a Christian school vs. (b) trying to be inclusive. However, the schools or the headteachers respectively do not necessarily follow one of the two strategies exclusively. On the contrary, in some interviews the tension between emphasising the Christian distinctiveness of the school and trying to be inclusive on the other hand became apparent. For example, the headteacher of one Anglican school made it very explicit in the interview that the school was a Church of England school and Christian. Nevertheless, she pointed out:

Well, on a personal level I think that you can be a very spiritual person without being religious. I am very, very keen that our children are given the information to make their own choice about it … we will not push Christianity down anyone’s throat. … We encourage children, up the older end of the school, to make their choices on that. (School 16 CE/VA)

While this headteacher (School 16 CE/VA) adopted a balanced approach between religious and more secular-inclusive language, headteachers of other schools can be counted more distinctly as either using ‘overtly religious’ or ‘more secular language’. One might think that these headteachers and their spiritual leadership is quite different from each other. However, coming back to Shaw’s model of ‘ethotic leadership’ there might be more convergence than becomes apparent at a cursory glance.

5. ‘Ethotic leadership’

As discussed in parts 4.2.8 and 4.2.9 above, there is vast variety in the language and attitudes Church school headteachers demonstrated in the interviews. While some of them used ‘overtly religious’ language and conveyed a powerful sense of mission, others hesitated to use any religious or Christian terms and were anxious that their schools should not be proselytising. It could be easy to dismiss the latter group of headteachers as un-Christian and question whether they are suitable leaders for Church schools. This misses the point. Those headteachers might not have explicitly used Christian vocabulary, but this is not to say that a robust ethos did not permeate their portrayal of what their school does for the children. It was interesting to note how ardently, using ‘secular’ language, they defended what were interpreted as central tenets of the Christian belief: to stand in for every person’s dignity and care for the most vulnerable. As the headteacher of School 6 (CE/Ac) made clear: ‘If we do anything, we do it because it’s good for our children.’ The headteacher of School 17 (CE and M-VA) also stressed the importance of a lived ethos:

It’s the ethos, the language that is lived through and through. The parents have noticed the difference at home. […] I will not accept anything less than what these children deserve. I won’t. And if you don’t like it go and work for somebody else who shares your values.

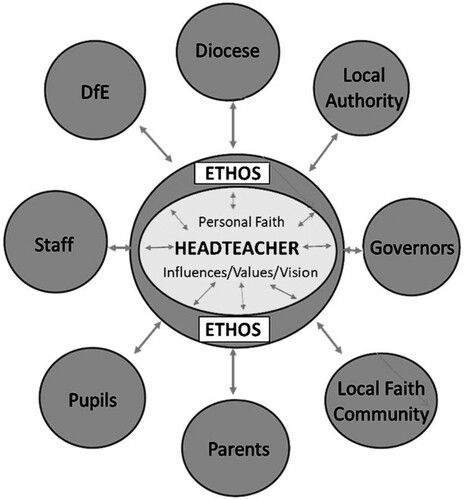

However, where this research differs from Shaw’s analysis is that for the Nexus headteachers it was overwhelmingly clear that the child was at the very centre of what they are doing and the motivation behind their actions. Across the different denominations as well as different school sizes, socio-economic contexts, etc. Church school headteachers stated explicitly that how they perform their Church school leadership was oriented towards what is best for the children. What became apparent in the analysis of the interviews was that pupils hold a stronger position; they are not just one among eight stakeholders with which the Church school headteacher interacts. Therefore, an amended version of Shaw’s model of ‘ethotic leadership’ is proposed that places another layer at the centre, surrounding the headteacher, to indicate that the ethos is based on what is good for the pupils. What became abundantly clear through this research and what is particularly insightful regarding Church school leadership is that even if Church school headteachers do not clothe what is happening in their schools in religious words, they nevertheless strive to create an environment that fosters the spiritual and religious growth of the children ().

6. Conclusion

This article examined the headteachers’ role as spiritual leader, within the wider research framework into the children’s spiritual development in the nexus of the school and the home. The aim was to learn more about the part a headteacher plays in shaping a Church school culture that allows for spiritual growth in children and facilitates children’s exploration of faith in the home. One aim of the research was to investigate how headteachers perceive their and their school’s relationship with the church and faith in general regarding the spiritual development of their pupils. This was done by analysing the language headteachers used to portray their own and their school’s role in facilitating children’s exploration of faith.

The analysis of the interviews has shown that there are two basic strategies in which Church school headteachers present what is happening in their schools regarding the spiritual development of children. Some headteachers emphasise the Christian distinctiveness of their schools while others are adopting a more ‘secular’ or humanist attitude, stressing inclusivity.

Regardless of the differences in style, all the headteachers interviewed showed a significant commitment to their pupils, to creating a surrounding for the children to prosper academically and spiritually, reflecting the holistic approach of both the Catholic and Church of England tradition. The research into Church school leadership showed that all the headteachers interviewed conveyed a powerful sense of ethos. The motivation behind their leadership is providing a beneficial environment for children that allows them to flourish. Based on the findings from the research study this article proposed an adapted version of Shaw’s model of ‘ethotic leadership’ that depicts the pupils not as one of eight stakeholders headteachers interact with but as being in the centre of the Church school headteachers’ leadership. This article has illuminated the centrality of the pupils in headteachers’ interpretation of the spiritual leadership of the Church school.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ursula Eisl

Ursula Eisl is doctoral research associate at the Chair of Dogmatics at the Faculty of Catholic Theology at the University of Würzburg (Germany). She studied Catholic Theology, English and history at the University of Salzburg (Austria), the University of East Anglia (UK), and Canterbury Christ Church University (UK) and is a qualified teacher. In 2021, she was research assistant at the NICER for the project ‘Lay Spiritual Leadership’.

Mary Woolley

Mary Woolley is a senior lecturer in education at Canterbury Christ Church University. After teaching history in Catholic schools in Birmingham and London her PhD explored 25 years of change in history education using an oral history approach. Recently Mary has been involved in research projects for NICER, particularly ‘Faith in the Nexus’ and ‘Beginning Teachers in Science Religion Encounters’.

Sabina Hulbert

Sabina Hulbert, previously a senior Research Fellow at NICER is now a Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for Health Services Studies at the University of Kent and a research adviser for the Research Design Service as part the NIHR Kent hub. She is working on the Health Behaviour of School Children study, an international longitudinal study sponsored by the WHO, monitoring health related indicators for children across the world.

Ann Casson

Ann Casson is Senior Research Fellow at the National Institute for Christian Education Research (NICER) at Canterbury Christ Church University. Prior to becoming a full-time researcher, she taught Religious Education in secondary schools in England. Ann is lead researcher on the Faith in the Nexus research project and Chaplains: Loss and Spiritual Resilience study.

Robert A. Bowie

Robert A. Bowie is Director of the National Institute for Christian Education Research (NICER) and Professor of Religion and Worldviews Education at Canterbury Christ Church University.

Notes

1 This research paper focuses on schools with a church foundation, subsequently the term ‘Church school’ will be used.

2 https://www.catholiceducation.org.uk/images/CensusDigestEngland2020.pdf (Accessed 19 July 2021).

3 https://www.churchofengland.org/about/education-and-schools/church-schools-and-academies (Accessed 19 July 2021).

4 SIAMS: https://www.churchofengland.org/about/education-and-schools/church-schools-and-academies/siams-school-inspections (Accessed 19 July 2021).

5 https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2005/18/section/48/enacted (Accessed 19 July 2021).

6 The report detailing the findings of the study is available online and can be retrieved from https://nicer.org.uk/faith-in-the-nexus (2020) (Accessed 30 March 2022).

References

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bryman, A. 2004. Social Research Methods. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Casson, A. 2018. “Catholic Identities in Catholic Schools: Fragmentation and Bricolage.” In Researching Catholic Education: Contemporary Perspectives, edited by S. Whittle, 57–70. Singapore: Springer.

- Casson, A., S. Hulbert, M. Woolley, and R. A. Bowie. 2020. Faith in the Nexus: Church schools and children’s exploration of faith in the home: A NICER research study of twenty church primary schools in England. PDF available at: March 30th, 2022.

- Catholic Education Service. 2014. Catholic Education in England and Wales. London: Catholic Education Service.

- Chadwick, P. 2001. “The Anglican Perspective on Church Schools.” Oxford Review of Education 27 (4): 475–487. doi:10.1080/03054980120086185

- Church of England. 2016. Church of England Vision for Education: Deeply Christian: Serving the Common Good. London: Church of England.

- Cisneros-Puebla, C. A., R. Faux, and G. Mey. 2004. “Qualitative Researchers Stories Told, Stories Shared: The Storied Nature of Qualitative Research. An Introduction to the Special Issue: FQS Interviews.” Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research 5: 3. Art. 37. Accessed 1 December 2021. https://doi.org/10.17169/fqs-5.3.547. https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/547/1180.

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1977. The Catholic School. London: Catholic Truth Society.

- Elshof, T. 2019. “The Increasing Relevance of Catholic Schools: A Parental Perspective from the Secularised Netherlands.” International Journal for Education Law, and Policy 15: 67–76.

- Fincham, D. 2010. “Headteachers in Catholic Schools: Challenges of Leadership.” International Studies in Catholic Education 2 (1): 64–79. doi:10.1080/19422530903494843

- General Synod. 2001. The Way Ahead: Church Schools of England in the New Millennium, GS 1406. London: Church House Publishing.

- Grace, G. 2000. “Research and the Challenges of Contemporary School Leadership: The Contribution of Critical Scholarship.” British Journal of Educational Studies 48 (3): 231–247. doi:10.1111/1467-8527.00145

- Grace, G. 2009. “Faith School Leadership: A Neglected Sector of In-Service Education in the United Kingdom.” Professional Development in Education 35 (3): 485–494. doi:10.1080/13674580802532662

- Jelfs, H. 2010. “Christian Distinctiveness in Church of England Schools.” Journal of Beliefs & Values 31 (1): 29–38. doi:10.1080/13617671003666688

- Johnson, H. 2002. “Three Contrasting Approaches in English Church/Faith Schools: Perspectives from Headteachers.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 7 (2): 209–219. doi:10.1080/1364436022000009118

- Johnson, H. 2003. “Using a Catholic Model: The Consequences of the Changing Strategic Purpose of Anglican Faith Schools and the Contrasting Interpretations Within Liberalism.” School Leadership & Management 23 (4): 469–480. doi:10.1080/1363243032000150980

- Johnson, H., and E. McCreery. 1999. “The Church of England Head: The Responsibility for Spiritual Development and Transmission of Tradition in a Multi-Cultural Setting.” International Journal of Children’s Spirituality 4 (2): 165–177. doi:10.1080/1364436990040205

- Johnson, H., E. McCreery, and M. Castelli. 2000. “The Role of the Headteacher in Developing Children Holistically: Perspectives from Anglicans and Catholics.” Educational Management and Education 25 (4): 389–403.

- Long, R., and S. Danechi. 2019. Faith Schools in England: FAQs. Briefing Paper 06972 House of Commons Library. Accessed November 2021. https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/SN06972/SN06972.pdf.

- Lumb, A. 2014. “‘Prioritising Children’s Spirituality in the Context of Church of England Schools: Understanding the Tensions.” Journal of Education and Christian Belief 18 (1): 41–59. doi:10.1177/205699711401800106

- Lydon, J. 2011. The Contemporary Catholic Teacher: A Reappraisal of the Concept of Teaching as a Vocation in the Catholic Christian Context. Saarbrucken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Merriam, S. B. 1998. Qualitative Research and Case Study Applications in Education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ofsted. 2021. Guidance: School Inspection Handbook: Section 8. Accessed 19 July 2021. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/section-8-school-inspection-handbook-eif/school-inspection-handbook-section-8.

- Rymarz, R., and Belmonte, A. 2019. Examining School and Parish Interaction: Some Implications for Religious Education. Global Perspectives on Catholic Religious Education in Schools: Volume II: Learning and Leading in a Pluralist World, 125–135.

- Shaw, A. 2015. Leadership of Voluntary Aided Schools: An Analysis from the Perspective of Headteachers. Thesis: University of Derby. Accessed 14 June 2021. https://derby.openrepository.com/handle/10545/583617.

- Shaw, A. 2017. “Leading Voluntary-Aided Faith Schools in England: Perspectives from Catholic, Anglican, and Jewish Headteachers.” International Studies in Catholic Education 9 (1): 89–107. doi:10.1080/19422539.2017.1286913

- Wilkin, R. 2014. ‘Interpreting the tradition’: a research report. International Studies in Catholic Education, 6(2), 164-177.

- Whittle, S. 2018. Researching Catholic Education. Contemporary Perspectives. London: Springer

- Woodhead, L., & Catto, R. (Eds.). 2012. Religion and change in modern Britain (pp. 1-33). London: Routledge.

- Worsley, H., ed. 2012. Anglican Church School Education: Moving Beyond the First Two Hundred Years. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Yin, R. K. 2009. Case Study Research: Design and Method. London: Sage.