Abstract

This article examines the concept of parental engagement in young people’s learning, as it relates to practice within Catholic schools. This examination will utilise the lens of Catholic Social Teaching, and church teaching more widely, to amplify the importance of supporting parents to engage with their children’s learning in Catholic schools. The paper proposes a new conceptualisation of the influences that impact on parents’ engagement with learning and concludes with a call for further training for teachers.

Introduction

This article will examine the concept of parental engagement in young people’s learning, as it relates to practice within Catholic schools. This examination will utilise the lens of Catholic Social Teaching, and church teaching more widely, to amplify the importance of supporting parents to engage with their children’s learning in Catholic schools. The paper proposes a new conceptualisation of the influences that impact on parents’ engagement with learning.Footnote1

What is parental engagement?

The value of parental engagement with young people’s learning is well enough known in the literature that a lengthy justification of interest in the subject is not needed (See Boonk et al. Citation2018 for an extended literature review). Parental engagement with young people’s learning has been shown to have beneficial effects on academic achievement, attendance at school, engagement with reading, etc. (Fan et al. Citation2017; Jeynes Citation2012; Jeynes Citation2014; Jeynes Citation2018; Salvatierra and Cabello Citation2022; Yu et al. Citation2022; Zwierzchowska-Dod Citation2022). Importantly for a discussion of this concept in Catholic schools, this engagement may be of more benefit to those children who are generally not well served by our current schooling system.Footnote2

Clarity, however, is needed around precisely what is meant by the term, ‘parental engagement in learning.’ The effective forms of parent engagement take place in the home learning environment, are not focused on homework completions or supporting the school, but rather focus on parental support for learning (rather than schooling) (Goodall Citation2017b). Mayer et al. (Citation2015) provide a useful distinction between parental involvement and parental engagement, suggesting that the first is a matter of ‘doing to’ parents rather than ‘doing with’ which is exemplified by the latter term (4). Goodall and Montgomery have provided a continuum which moves from parental involvement in schooling (in which agency and power resides with school staff) (Goodall Citation2017a) through to parental engagement with learning, wherein parents (broadly defined) are actively supporting their children’s learning, outside of the confines of the school (Goodall and Montgomery Citation2014). It is this engagement with learning, which takes place in the realm of the family rather than the school, that has the greatest impact on young people’s outcomes, and may, when enacted well, provide even greater support for children and young people who are traditionally less well served by the schooling system (Anguiano, Thomas, and Proehl Citation2020; Blitz et al. Citation2013; Field Citation2010; Redding, Langdon, and Meyer Citation2004).

Parental engagement through the lens of Catholic social teaching

The social teaching of the Catholic Church encompasses a wide body of work, which, broadly, relates to how the Church and Church members should act in the world. This set of teachings comprises work on subjects as diverse as capital punishment (Catechism of the Catholic Church Citation1994) to environmental issues (Francis Citation2015). Eick and Ryan characterise Catholic Social Teaching (CST) as a ‘religious response to social injustices’ (Citation2014, 32).

Scanlan (Citation2008) summarises Catholic social teaching as having three major themes, which are interrelated and build one upon the other. The first and foundational theme is that of the value of the human person. This is then followed by the value of the common good – a value which flows logically from the first as the common good is that which best supports the valuable individuals within it. Due to the fallen nature of humanity, these associations of persons often foster (if not embody) injustice and a lack of equity between members. This obviously mitigates against the first tenet, which highlights not only the value ascribed to each individual but also that this value inheres in all humans, without exception. Therefore, the third tenet of Catholic social teaching is a preferential ‘option for the marginalised’ (p.31), that is, giving special preference to those who suffer most from the societies of humans. Relating this to education, Gravissimum Educationis (Citation1965) enjoins the faithful to ‘spare no sacrifice in helping Catholic schools … especially in caring for the needs of those who are poor in the goods of this world or who are deprived of the assistance and affection of a family or who are strangers to the gift of faith’ (9).

These three elements are intended to operate within the overall society of humans, which is itself composed of groups and associations. Holyk-Casey, in relating this to education and schooling, suggests that the primary themes from SCT which impact on staff relationships with parents are seeing parents as the primary educators of young people, creating a mutual, trusting relationship with parents, developing community, ‘embracing diversity and working toward social justice in low SES Schools’ (Citation2012, 3). This highlights the value of all the individuals involved and centres the relationships around the good of the young person (arguably the most vulnerable, least agentic member of the group). All of these elements will be discussed below.

The option for the poor and the marginalised

Catholic schools have a clear obligation to serve those who are most disadvantaged in society (McKinney and Hill Citation2010). Children who are from marginalised groups, from low SES backgrounds, often do less well in the current systems than their more advantaged peers (Mayer et al. Citation2019; Tessier Citation2018; Wang and Wu Citation2023). In some countries, Catholic schools have traditionally been located in areas of deprivation – in this sense, they fulfil the obligation on a group level, providing high quality education in economically challenged areas; there is some evidence that the presence of a Catholic school has beneficial effects for the entire community (Anguiano, Thomas, and Proehl Citation2020). McKinney and Hill (Citation2010) suggest that this option for the poor is a ‘commitment to oppose structural injustice’ (164); providing high quality education in such areas is one way of addressing societal inequity. More specifically related to parental engagement, supporting parents to engage with young people’s learning may well have a greater impact for children at risk of underachievement in the current system (Boonk et al. Citation2018).

McLaughlin (Citation2005) suggests that the goals of Catholic schools (in Australia, but these apply more widely) can be summed up as providing quality education, a nurturing community and ‘liberation from forms of oppression’ (230). Indeed, the quality of teaching seems to be one of the main reasons parents choose to send their children to Catholic schools (McLaughlin Citation2005). This goal, in addition to the impact that Catholic schools can have not only on individual students but also on communities, demonstrates one way Catholic schools fulfil the option to support the poor, the vulnerable and the marginalised.

Supporting parents to support young people who are at risk of underachieving can help schools fulfil all three elements of Catholic Social Teaching: the individual children are of value, the common good (society) benefits from greater educational success for a wider group of young people and finally, such support could be seen as fulfilling the need for preferential treatment of marginalised people in society, as parental support for learning has been shown to support children from less advantaged backgrounds.

The value of the family in Catholic thought

Catholic teaching has long been clear on the value ascribed to the family in the upbringing of children. Parents are to be recognised as ‘the primary and principle educators’ of children, and, in fulfilling that function, the family requires the ‘help of the whole community’ (Gravissimum Educationis Citation1965, 3), including support from civil society as well as schools. The education provided by parents/families is envisioned as wide ranging; the family is seen as the ‘first, and fundamental school of social living’ and parents are the ‘natural and irreplaceable agents in the education of their children’ (Congregation for Catholic Education Citation1982, 34). In this vein, it is worth quoting the Code of Canon Law:

Parents must cooperate closely with the teachers of the schools to which they entrust their children to be educated; moreover, teachers in fulfilling their duty are to collaborate very closely with parents, who are to be heard willingly and for whom associations or meetings are to be established and highly esteemed. (Law Citation1983, 796, 3; emphasis added)

The Catholic school advantage

One of the ways this option for the marginalised can be seen is in the general discussion of the advantage students gain by attending a Catholic school. (See Fusco Citation2005 for a history of research on the advantages of attending a Catholic school).

For many years, authors have investigated the Catholic School Advantage (abbreviated the CSA), (Morgan Citation2001). Although there are discussions in the literature about the nature and exact proportion of this advantage (Cardak and Vecci Citation2013; Freeman and Berends Citation2016), there is still an overall agreement that attending a faith based school in general (Jeynes Citation2005) and a Catholic school in particular, can support the achievement of students, including minority urban young people (Freeman and Berends Citation2016) and those experiencing poverty (Morgan Citation2001). Fleming, Lavertu, and Crawford (Citation2018) concluded that attending a Catholic high school had beneficial effects on grade point averages for most students but that the impact was greater (0.17 points higher than similar students in other schools) for non-white students than for white students (0.9 points higher).

There are various explanations for the Catholic School Advantage (CSA), which include a more academic curriculum, differences in enrolment, mutual trust between families and schools, a culture of positive behaviour and high expectations of students (Anguiano, Thomas, and Proehl Citation2020), parental choice, attracting students who have the capability for high achievement, a culture of motivation and hard work, and an emphasis on community (Freeman and Berends Citation2016). Many of these elements also support familial engagement in both the life of the school itself and a more wide-ranging engagement in learning. Morris (Citation2010) suggests that in relation to Catholic schools in England, one explanation for the higher percentages of pupils who have good or excellent attitudes to schooling, may be ‘socio-cultural processes connected with the nature of the institution’s ethos,’ which then impacts on the ‘educational stances’ adopted in the school (88). Overall, Freeman and Berends (Citation2016), sum up the situation stating, ‘ … the CAS persists, because Catholic schools are more successful than public [meaning state] schools are educating students of differing social backgrounds’ (24).

One element which seems to support the Catholic school advantage is the community nature of such schools. They are often closely and clearly embedded within a parish or religious order, and one of the benefits of Catholic schools for young people seems to be that they see teachers as community role models (Anguiano, Thomas, and Proehl Citation2020).

Decades ago, Coleman proposed an explanation for the CSA which may be of particular importance in relation to parental engagement. Coleman (Citation1988) suggested that for children and young people who might not otherwise achieve in the system, a Catholic school, and in particular the community in and around such schools, might supply the ‘social capital’ which the student might otherwise lack.

In bringing this argument to the present day, it is important to reframe it away from a deficit view of the family or the individual student (e.g. that the student ‘lacks’ social capital) to a way of understanding the issue as a systemic one, in which certain types of social and cultural capital are expected and valued over others, by the schooling system as a whole, and the staff within that system (Cushing Citation2022; Garcia and Guerra Citation2004; Goodall Citation2019; Irizarry Citation2009; Salkind Citation2008; Sharma Citation2018).

In analysing data from a national sample of school inspections, Morris (Citation2010) found that while Catholic primary schools were judged to have good relationships with parents slightly more often than other schools, this gap widened significantly in the secondary phase, with Catholic schools being 12% more likely to have excellent or very good links with parents. As parental/school relationships are at the heart of an effective partnership (Goodall Citation2017b), this might argue that Catholic schools should find supporting parental engagement easier than other schools might do. The importance of this relationship has been clearly shown in Church documents, ‘The success of the educational path depends primarily on the principle of mutual cooperation, first and foremost between parents and teachers’ (Congregation for Catholic Education Citation2022, 16). In working out how such relationships are to be structured, it is useful to take into account three ideas. The first is the principle of subsidiarity in Catholic Social Teaching; the second is the necessity of trust in such relationships, and the third is the need to avoid a deficit conception of families.

Subsidiarity: the value of the home learning environment

The principle of subsidiarity is enshrined in Catholic Social Teaching (Aroney Citation2014; McIlroy Citation2003). We read in Familiaris Consortio (John Paul II Citation1982, 23), that the principle of subsidiarity must operate in relation to interactions with families as well as in other spheres such as business and law. It is worth noting that the family, no matter how large or small, constitutes a true ‘institution’ as understood by the principle of subsidiarity, is attested in Catholic Social Teaching (Encyclical Citation1891). Church teaching highlights the family as a natural and true ‘society’ (Encyclical Citation1891, 12) which, I would suggest, must be considered as the first locus of learning, supported not only by schools but any other organisation/institution which provides education.

Centissiumus Annus (John Paul II Citation1991, 48) points out that higher order communities should not take to themselves the functions of lower, or interfere with their internal life, but should instead support lower order organisation as needed (Aroney Citation2014). The pope’s writing about subsidiarity here is less forceful than one of his predecessors, as Pius XI called it a ‘grave evil’ and ‘injustice’ for a larger organisation to ‘arrogate to itself functions which can be performed efficiently by smaller and lower bodies’ (Aroney Citation2014; Pius XI Citation1931, 79). This of course calls for judgement on the part of ‘the higher organisation’ or, more accurately, those within that organisation as to whether or not the smaller group is able to perform its functions efficiently. If we take this at face value, then the school should not interfere in the workings of the family, but rather offer support as needed.

When we look further back into Catholic teaching, Aroney (Citation2014) points out that Aquinas clearly understood that individuals might be members of several societies which might be considered as nested one within, or at least, overlapping, with another – a family, a guild, a state and a nation, for example. This is an important element of the discussion of subsidiarity between the school and the family, as it highlights that these are not dichotomous institutions, but rather overlapping, connected organisations, finding, in the case of the family and the school, the point of mutual connection and contact as the learning of the young person.

However, there is another element of the concept of subsidiarity which must be acknowledged – not only does the concept demand that ‘lower’ institutions retain an appropriate level of freedom, but it also requires that these lower institutions have a right to support from higher bodies. To relate this to the topic in hand, not only should families be free from unwarranted interference from schools, but families also have every right to expect appropriate support from schools, (as well as parishes, diocese, etc.), as ‘higher institutions’. The Congregation for Catholic Education has called for ‘healthy cooperation’ between bodies at all levels in support of schools (2022, 15). This would seem to suggest that families should be able to expect appropriate support to engage with young people’s learning. ‘Appropriate’ here would also require knowledge of families on the part of school staff.

Importance of relationships: not institutions but communities

As far as Catholic schools are concerned, the conciliar declaration represents a turning point, since, in line with the ecclesiology of Lumen Gentium [14], it considers the school not so much as an institution but as a community. (Congregation for Catholic Education Citation2022, 16)

The school must be a community whose values are communicated through the interpersonal and sincere relationships of its members and through both individual and corporative adherence to the outlook on life that permeates the school. (The Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education Citation1977, 31)

While I have, so far, conceived of families and schools as institutions in relation to the concept of subsidiarity, it is also entirely appropriate to consider them as communities, a concept which can be defined as a group who are bound by mutual social relation, (rather than bounded for example by a physical locality) (Bradshaw Citation2008). The social relation here centres around the child or young person; parents and school staff may relate to the young person differently, but all relate to a desire for the best outcome for that person.

Trust is the foundation of partnership working and is founded on, in this instance, a mutual desire to support the learning of the young person they have in common. This is ‘learning’ in the widest sense, to take in academic socialisation, faith and social learning. This mutual trust is bi-or-multidirectional; parents trust school staff to care for and educate their children, and indeed, are often said to ‘entrust’ their children to the care of the school and its staff. However, trust must also flow from school staff to parents and families. In relation to families’ engagement in learning, this mutual trust requires school staff to understand and support parents’ interactions with their children’s learning outside of school. Parents should be approached by school staff as valuable partners in their students’ learning journeys.

It is precisely in recognising the primacy of parents in the learning and education of their children that the imperative of the other elements arise. That is, in not only understanding but embedding the concept of families as first educators, arises the necessity to therefore create the trusting relationships which are the foundation of authentic community and partnerships, which then works toward the accomplishment of social justice, within and without the confines of both school and family (as both subsist within larger organisations, such as cities, states and nations). This then returns us to the concept of parental engagement in learning rather than involvement in schooling. This engagement requires school staff to work with (rather than on, cf the concept suggested by Manzom (Manzon et al. Citation2015) above).

As noted above, the community element of Catholic schools may be one of the factors which contributes to the value such schools appear to add to young people’s learning. This is one of the ‘communities’ around the learner, a larger one, composed of the bonds which exist between different groups, including school staff and families, but also extending more widely to encompass for example, the parish or other aligned groups.

Distance between intent and reality: schools and parental engagement

Research has frequently found a gap between the importance ascribed to parental engagement with learning and the actions needed to support that engagement Goodall et al. (Citation2022a); (Hornby and Blackwell Citation2018; Hornby and Lafaele Citation2011; Willemse et al. Citation2017, Citation2018). As long ago as 1994, Arthur pointed out that the Church rhetoric around the importance of families in relation to Catholic schools was often not worked out in practice (Arthur Citation1994). Although these remarked were based on Catholic schools in England and Wales, further research (Willemse et al. Citation2017, Citation2018) would suggest that the issue is more widespread. This disjunction between intention and action is well-known in the realms of parental engagement.

This discrepancy between what is mandated and what takes place may have a number of explanations – I would suggest that any, or perhaps all of these may be at work in any given school – they act as intertwined influences.

Scanlan (Citation2008) suggests that there exists a ‘grammar of Catholic schooling’ which might be interpreted simply as ‘the way things are done here’. This suggests that the understanding of how things work in a given organisation functions in much the same way as grammar does for language. Cyr, Weiner, and Woulfin (Citation2022) suggest the term ‘logics’ to cover the same general idea – the underpinning assumptions and beliefs that feed into not only action but the understandings on which those actions are based. This grammar, or logic, or perhaps habitual way of doing things is not perhaps an explanation for how the status quo, that is a distance between an appropriate valuing of and support for parental engagement with learning, and reality, has come to be, but it is a very good explanation for why there has been a lack of change, even as understandings of these concepts outside of schools have moved on (Goodall et al. Citation2022a).

Scanlan argues that the grammar of Catholic schooling allows those working within the system to ignore the disconnect between espoused and lived values (Goodall et al. Citation2022a) – in Scanlan’s case, between Catholic social teaching and creeping elitism in Catholic schools. In our case, this would refer to the discrepancy between the declarations of the importance of parental engagement with learning (on the part of the school staff) and the imperative to involve families in learning (in Church documents) and the lived reality of the lack of partnership between schools and families (Goodall Citation2017b).

Scanlan (Citation2008) also applies the Foucauldian concept of discourse (Foucault Citation1972) which suggests that the very reality of ‘that which can be thought’ is to some extent at least, dictated to individuals by the societies and cultures in which they live. This would align to the Bronfenbrennian ecological concept of the influences around the child (Boulanger Citation2019; Bronfenbrenner Citation1979, Citation1986); the ‘discourse’ within a school will impact on staff who interact with both the child and their family.

An ecological view of parental engagement in Catholic schools

The ecological view of influences surrounding children proposed by Bronfenbrenner (Citation1986) provides a useful framework for understanding the interplay of these different communities on children’s learning and development. Children and young people (and indeed, all people) are ‘nested’ within concentric (and overlapping (Epstein et al. Citation2002)) circles of influence, which begin with the individual and move outward to encompass first (within Bronfenbrenner’s scheme) family, school church, health support providers and peers. We may align these influences to the ‘forces’ which Hiatt-Michael (Citation2008) holds impact on parental engagement – families’ cultural beliefs, their social structures and economic and political influences.

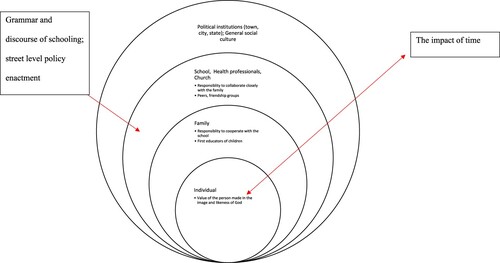

If we align this to the principles of subsidiarity, and the principles of Catholic social teaching, we arrive at a slightly different diagram than usually accompanies Bronfenbrenner’s thesis, with a greater number of circles, depicting the different levels not only of influence on the child but also on the ‘order’ of the institutions or communities involved. This conceptualisation would place the family in its own circle, directly beyond that of the individual, as having as it were the next higher ‘order’ of influence, agency and authority over the individual of the first circle, as depicted in .

Also shown in this diagram are the additional elements: the influence of the ‘grammar’ of schools, and the impact that ‘street level bureaucrats’ (Weatherley and Lipsky Citation1977) have on the everyday enactment of policy. While these ideas might be presumed to be present, the diagram highlights the impact that these elements have in relation to parental engagement in learning, and the support that schools are able to offer to this engagement.

It is important to note, as pointed out by Manzon et al. (Citation2015) that these circles around the child are all linked and are impacted by ‘reciprocal influences’ operating on all levels (p.12). From our point of view, this reinforces the notion that schools and families do not operate independently of one another (even if it would appear that they do so in some instances), as the child or young person who is impacted by their influences, will always remain as a point of contact and connection. Manzon et al. (Citation2015) also point out that these interactions between groups show a shared responsibility between/among them for the development of the young person. This again aligns to the concept of subsidiarity which calls for an appropriate interplay between organisations, with the higher offering support to the lower as needed. Indeed, a more accurate representation of these influences would require three dimensional globes interacting with each other.

The diagram also contains an arrow representing the temporal element involved in how these influences around the child play out. Parental engagement in learning changes as young people grow up, not only in relation to the subject matter learning but also because of the changes in the child themselves, such as growing independence and individual agency, and the resulting changes in the relationships between the child and the parties involved (Jeynes Citation2014).

Another element highlighted in the diagrams is that policy is often created at a distance from those who will put that policy into practice; it might be difficult, for example, to imagine a wider difference in experience and circumstance than that between the workings of the second Vatican Council and an inner city Catholic school teachers. Policies, however well intentioned, need to be put into practice by those on the ground (indeed, aptly described as ‘practitioners’); the term ‘street level bureaucrats’ has been suggested as an appropriate term for those who daily make policy into practice (Weatherley and Lipsky Citation1977) thus, while the Council fathers of members of a sacred Congregation may decree that Catholic schools should embody and foster community, it is the individual school leaders, staff and families who must actually create and nurture those communities on a daily basis.

Ressler (Citation2020) points out that parental engagement programmes in the past have concentrated on parents, seeing them as individual actors, who are entirely responsible for their engagement with learning (or lack of it) – this can lead to what Dahlstedt and Fejes (Citation2014) have termed the ‘responsiblisation of parents’, seeing parents as solely responsible for their children’s outcomes. Ressler points out that this view dismisses the influence of ‘overlapping ecological contexts that surround the family, school and community’ (pg. 4). The diagram offered in attempts to fill this lacuna. Research on Catholic schools often seems to focus on parental involvement which is school based, and school focused, rather than on parental engagement with learning, which is focused on the learning of the young person (Vera et al. Citation2017). Instead, interventions, events, and work overall to support parental engagement in learning must take into account the views and actions of all the actors involved: parents, school staff and the young people, themselves (Goodall Citation2022).

Acknowledging the primacy of the family in children’s learning should not lead to deficit judgements of parents by school staff, as can sometimes be the case (Eick and Ryan Citation2014). The support due to the ‘lower’ institution from the ‘higher’ must always be acknowledged and enacted by schools in relation to families (and, of course, by larger systems such as local authorities, districts, and dioceses in relation to families and toward the individual school).

Yet in enacting these policies (which were themselves impacted by external influences in that creation), staff and families are working within all the influences shown on the diagram (and arguably a great many more, as each situation will have a unique combination of influences). Proclamation of policy is far easier than enactment.

Avoiding deficit views of families

While there is not room here for an in-depth treatment of the basis for and impact of deficit views of the family (Baum and Swick Citation2008; Berkowitz et al. Citation2017; Gorski Citation2008, Citation2016, Citation2012), the fact that staff may hold such beliefs seems well-established in the literature. Deficit views often seem to arise from a difference in backgrounds and social and cultural capital between families and teachers; they may be pertinent in schools which serve marginalised communities (Baum and Swick Citation2008; Bryan et al. Citation2021), which, as we have seen, can form part of Catholic schools’ proper response to the option for the poor.

Further, we have seen that this concept of subsidiarity calls for judgement, particularly of the ‘higher’ or larger group (the school) that the ‘lower’ or smaller groups (the family) is able to fulfil its obligations in regard to any joint action (such as the education of young people). Deficit views of families, which underestimate the value that parents and other can bring to young people’s learning (and indeed, schooling) are likely to undermine the possibility of true partnerships between families and schools, as staff may not acknowledge, or give due weight to, the value that parents and families can bring to young people’s learning.

The value of the family as the first and best teachers of their children is enshrined in Church teaching and canon law – this should, logically speaking, negate any possibility of a deficit view of parents/parental engagement in Catholic schools. Yet this deficit view clearly continues to exist (Eick and Ryan Citation2014). This is hardly surprising; schools, including Catholic schools, are enmeshed in the societies within which they operate, even as such schools are called to challenge that society and its values.

Moving forward: a need for training

If the ‘grammar’ and ‘discourse’ of a given school – or indeed, given school system (Harris and Jones Citation2019) is one of school focused parental involvement, and of deficit discourses around parents in general, it will be very difficult (but not impossible) for staff and indeed families to imagine how things could be different.Footnote3 School staff and the families they support need to operate in the real, rather than an idealised world.

Eick and Ryan (Citation2014) have highlighted the particular disparity between the multicultural nature of many Catholic schools and the educational experience, background and indeed, comfort zone of preservice teachers in their teaching preparation programme. Research has consistently shown the propensity of involved parents in schools (if not in learning) to mirror the social and cultural capital of school staff (Anderson and Minke Citation2007; Berkowitz et al. Citation2017). Eick and Ryan sound a call for ‘teacher Education programmes at Catholic institutions’ to ‘help pre-service teachers to develop a critical social consciousness informed by Catholic social teaching (27).

I would suggest that this critical consciousness must be expanded to (if not founded upon) an understanding of the value and place of the family in relation to the learning of young people. Movements toward amore appropriate relationship between staff and families in Catholic schools must not only reference but rely upon concepts such as Freire’s critical pedagogy (Freire Citation1970), which prompts teachers to consider (and challenge) the structures of power in the systems within which they work. These elements of power play out very often in the relationships between school staff and families (Berkowitz et al. Citation2017; Bryan et al. Citation2021; Childers-McKee and Hytten Citation2015) allowing the system to keep parents at a distance and, in defiance of the principle of subsidiarity, abrogate to themselves that which rightly belongs to the family as a ‘lower’ institution.

Research has consistently shown an appetite among teachers for more training and support around parents’ engagement in learning (cf Goodall et al. Citation2022b); if we wish to support staff in Catholic schools to carry out the mandates of CST within their own settings, we must give them the knowledge, experience and expertise to do so.

Declaration of competing interest

There are competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgements

With acknowledgement to the Catholic School Parents Queensland staff and members, who sponsored the work which led to this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Janet Goodall

Janet Goodall is a professor in the Department of Education and Childhood studies. She is the Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences Lead for Post Graduate Research Students. Having first studied theology and obtained a licentiate in Sacred Theology, her research now is primarily about parents' engagement in young people's learning. She has worked with numerous schools, governments, and governmental bodies to support parental engagement, and lectured and written widely on the subject.

Notes

1 While this article concentrates on practice within Catholic schools, the concepts can be more widely applied, by Catholic families and staff in any giving schooling system.

2 I have chosen this formation of the issue following the work of Ladson-Bilings, who suggests a move from the term ‘achievement gap’ – which focuses on individual children’ to ‘educational debt’, which is focused on a society which does not equally support the learning of all children. I wish to highlight the systemic issues in current schooling which mitigate against achievement for many students Ladson-Billings, G. (Citation2006). From the achievement gap to the education debt: Understanding achievement in US schools. Educational Researcher, 35(7), 3–12.

3 As Kuhn Kuhn, T. (Citation1996). The structure of scientific revolutions. The University of Chicago Press. Shows, however, it is certainly possible for individuals to think outside the accepted schema – the author was referring to scientific understanding of the world but the concept applies in all areas of life, particularly for those who are also called to bring forth for a new heaven on earth [check quotation].

References

- Anderson, K. J., and K. M. Minke. 2007. “Parent Involvement in Education: Toward an Understanding of Parents’ Decision Making.” The Journal of Educational Research 100 (5): 311–323.

- Anguiano, R., S. Thomas, and R. Proehl. 2020. “Family Engagement in a Catholic School: What Can Urban Schools Learn?” School Community Journal 30 (1): 209–241.

- Aroney, N. 2014. “Subsidiarity in the Writings of Aristotle and Aquinas.” Global Perspectives on Subsidiarity, 9–27.

- Arthur, J. 1994. “Parental Involvement in Catholic Schools: A Case of Increasing Conflict.” British Journal of Educational Studies 42 (2): 174–190.

- Baum, A. C., and K. J. Swick. 2008. “Dispositions Toward Families and Family Involvement: Supporting Preservice Teacher Development.” Early Childhood Education Journal 35 (6): 579–584.

- Berkowitz, R., R. A. Astor, D. Pineda, K. T. DePedro, E. L. Weiss, and R. Benbenishty. 2017. “Parental Involvement and Perceptions of School Climate in California.” Urban Education 37 0042085916685764.

- Blitz, L. V., L. Kida, M. Gresham, and L. R. Bronstein. 2013. “Prevention Through Collaboration: Family Engagement with Rural Schools and Families Living in Poverty.” Families in Society 94 (3): 157–165.

- Boonk, L., H. J. M. Gijselaers, H. Ritzen, and S. Brand-Gruwel. 2018. “A Review of the Relationship Between Parental Involvement Indicators and Academic Achievement.” Educational Research Review 24: 10–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001.

- Boulanger, D. 2019. “Bronfenbrenner’s Model as a Basis for Compensatory Intervention in School-Family Relationship: Exploring Metatheoretical Foundations.” Psychology & Society 11 (1): 212–230.

- Bradshaw, T. K. 2008. “The Post-Place Community: Contributions to the Debate About the Definition of Community.” Community Development 39 (1): 5–16.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1979. The Ecology of Human Development: Experiments by Nature and Design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. 1986. “Ecology of the Family as a Context for Human Development: Research Perspectives.” Developmental Psychology 22 (6): 723–742.

- Bryan, J., L. M. Henry, A. D. Daniels, M. Edwin, and D. M. Griffin. 2021. “Infusing an Antiracist Framework Into School-Family-Community Partnerships.” In Antiracist Counseling in Schools and Communities, 2–2. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association Press. https://imis.counseling.org/store/detail.aspx

- Cardak, B. A., and J. Vecci. 2013. “Catholic School Effectiveness in Australia: A Reassessment Using Selection on Observed and Unobserved Variables.” Economics of Education Review 37: 34–45.

- Catechism of the Catholic Church. 1994. Geoffrey Chapman.

- Childers-McKee, C. D., and K. Hytten. 2015. “Critical Race Feminism and the Complex Challenges of Educational Reform.” The Urban Review 47 (3): 393–412.

- Coleman, J. S. 1988. “‘Social Capital’ and Schools.” The Education Digest 53 (8): 6.

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 1982. Lay Catholics in Schools.

- Congregation for Catholic Education. 2022. The Identity of the Catholic School for a Culture of Dialogue. Vatican City: Libreria Editrice Vaticana: Vatican City.

- Cushing, I. 2022. “Word Rich or Word Poor? Deficit Discourses, Raciolinguistic Ideologies and the Resurgence of the ‘Word Gap’ in England’s Education Policy.” Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 1–27. Advanced Online Publication.

- Cyr, D., J. Weiner, and S. Woulfin. 2022. “Logics and the Orbit of Parent Engagement.” School Community Journal 32 (1): 9–38.

- Dahlstedt, M., and A. Fejes. 2014. “Family Makeover: Coaching, Confession and Parental Responsibilisation.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 22 (2): 169–188.

- Gravissimum Educationis. 1965. “Declaration on Christian Education.” Vatican Council II: The Conciliar and PostConciliar Documents, 725–738.

- Eick, C. M., and P. A. Ryan. 2014. “Principles of Catholic Social Teaching, Critical Pedagogy, and the Theory of Intersectionality: An Integrated Framework to Examine the Roles of Social Status in the Formation of Catholic Teachers.” Journal of Catholic Education 18 (1): 26–61.

- Encyclical, P. 1891. “Rerum Novarum.” Quadragesimo anno.

- Epstein, J. L., M. G. Sanders, B. S. Simon, K. C. Salinas, N. R. Jansorn, and F. L. Van Voorhis. 2002. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Fan, H., J. Xu, Z. Cai, J. He, and X. Fan. 2017. “Homework and Students’ Achievement in Math and Science: A 30-Year Meta-Analysis, 1986–2015.” Educational Research Review 20: 35–54.

- Field, F. 2010. The Foundation Years: Preventing Poor Children Becoming Poor Adults (403244 /1210).

- Fleming, D. J., S. Lavertu, and W. Crawford. 2018. “High School Options and Post-Secondary Student Success: The Catholic School Advantage.” Journal of Catholic Education 21 (2): 1–25.

- Foucault, M. 1972. The Archaeology of. Knowledge. London: Tavistock.

- Francis, P. 2015. Praise Be to You: Laudato Si': On Care for Our Common Home. Vatican City: Ignatius Press.

- Freeman, K. J., and M. Berends. 2016. “The Catholic School Advantage in a Changing Social Landscape: Consistency or Increasing Fragility?” Journal of School Choice 10 (1): 22–47.

- Freire, P. 1970. Pedagogy of the Oppressed.

- Fusco, J. S. 2005. “Exploring Values in Catholic Schools.” Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice 9 (1). Advanced Online Publication.

- Garcia, S. B., and P. L. Guerra. 2004. “Deconstructing Deficit Thinking: Working with Educators to Create More Equitable Learning Environments.” Education and Urban Society 36 (2): 150–168.

- Goodall, J. 2017a. “Learning-Centred Parental Engagement: Freire Reimagined.” Educational Review 70 (5): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1358697.

- Goodall, J. 2017b. Narrowing the Achievement Gap: Parental Engagement with Children’s Learning Creating A Learning-Centred Schooling System. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Goodall, J. 2019. “Parental Engagement and Deficit Discourses: Absolving the System and Solving Parents.” Educational Review 73 (1): 98–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1559801.

- Goodall, J. 2022. “A Framework for Family Engagement: Going Beyond the Epstein Framework.” Cylchgrawn Addysg Cymru / Wales Journal of Education 24(2), https://doi.org/10.16922/wje.24.2.5. Advanced Online Publication.

- Goodall, J., H. Lewis, Z. Clegg, I. Ramadan, M. Williams, A. Ylonen, S. Owen, D. Roberts, C. Hughes, and C. Wolfe. 2022a. “Defining Parental Engagement in ITE: From Relationships to Partnerships.” Wales Journal of Education 24.

- Goodall, J., H. Lewis, Z. Clegg, A. Ylonen, C. Wolfe, S. Owen, C. Hughes, M. Williams, D. Roberts, and I. Ramadan. 2022b. “Defining Parental Engagement in ITE: From Relationships to Partnerships.” Wales Journal of Education 24(2). Advanced Online Publication.

- Goodall, J., and C. Montgomery. 2014. “Parental Involvement to Parental Engagement: A Continuum.” Educational Review 66 (4): 399–410. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2013.781576.

- Gorski, P. 2008. “The Myth of the “Culture of Poverty”.” Educational Leadership 65 (7): 32–36.

- Gorski, P. C. 2012. “Perceiving the Problem of Poverty and Schooling: Deconstructing the Class Stereotypes That Mis-Shape Education Practice and Policy.” Equity & Excellence in Education 45 (2): 302–319.

- Gorski, P. 2016. “Rethinking the Role of “Culture” in Educational Equity: From Cultural Competence to Equity Literacy.” Multicultural Perspectives 18 (4): 221–226.

- Harris, A., and M. S. Jones. 2019. System Recall: Leading for Equity and Excellence in Education. Corwin.

- Hiatt-Michael, D. B. 2008. “Families, Their Children's Education, and the Public School: An Historical Review.” Marriage & Family Review 43 (1-2): 39–66.

- Holyk-Casey, K. 2012. A Qualitative Study of Three Urban Catholic High Schools: Investigating Parent and Principal Expectations and Realizations of Parental Involvement and the Parent-School Relationship. Loyola Marymount University.

- Hornby, G., and I. Blackwell. 2018. “Barriers to Parental Involvement in Education: An Update.” Educational Review 70 (1): 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1388612.

- Hornby, G., and R. Lafaele. 2011. “Barriers to Parental Involvement in Education: An Explanatory Model.” Educational Review 63 (1): 37–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2010.488049.

- Irizarry, J. 2009. Cultural Deficit Model. Education.com.

- Jeynes, W. 2005. “The Impact of Religious Schools on the Academic Achievement of Low-SES Students.” Journal of Empirical Theology 18 (1): 22–40.

- Jeynes, W. H. 2012. “A Meta-Analysis on the Effects and Contributions of Public, Public Charter, and Religious Schools on Student Outcomes.” Peabody Journal of Education 87 (3): 305–335.

- Jeynes, W. H. 2014. “Parental Involvement That Works … Because It's Age-Appropriate.” Kappa Delta Pi Record 50 (2): 85–88. https://doi.org/10.1080/00228958.2014.900852.

- Jeynes, W. H. 2018. “A Practical Model for School Leaders to Encourage Parental Involvement and Parental Engagement.” School Leadership & Management 38 (2): 147–163.

- John Paul II. 1982. Apostolic Exhortation: Familiaris Consortio. Vatican City: St Paul Publications.

- John Paul II. 1991. Centesimus Annus.

- Kuhn, T. 1996. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Ladson-Billings, G. 2006. “From the Achievement Gap to the Education Debt: Understanding Achievement in US Schools.” Educational Researcher 35 (7): 3–12.

- Law, C. o. C. 1983. The Code of Canon Law in English Translation. The Canon Law Society of Great Britain and Ireland, The Canon Law Society of Australia And New Zealand. Retrieved 06.04.02 from www.deacons.net/Canon_Law/Default.htm.

- Manzon, M., R. N. Miller, H. Hong, and L. Y. L. Khong. 2015. Parent engagement in education NIE Working Paper Series No. 7.

- Mayer, S. E., A. Kalil, P. Oreopoulos, and S. Gallegos. 2019. “Using Behavioral Insights to Increase Parental Engagement.” Journal of Human Resources 54 (4): 900–925. https://doi.org/10.3368/jhr.54.4.0617.8835R.

- McIlroy, D. 2003. “Subsidiarity and Sphere Sovereignty: Christian Reflections on the Size, Shape and Scope of Government.” Law & Just.-Christian L. Rev. 151: 739–763.

- McKinney, S., and R. Hill. 2010. “Gospel, Poverty and Catholic Schools.” International Studies in Catholic Education 2 (2): 163–175.

- McLaughlin, D. 2005. “The Dialectic of Australian Catholic Education.” International Journal of Children's Spirituality 10 (2): 215–233.

- Morgan, S. L. 2001. “Counterfactuals, Causal Effect Heterogeneity, and the Catholic School Effect on Learning.” Sociology of Education 74 (4): 341–374.

- Morris, A. 2010. “Parents, Pupils and Their Catholic Schools: Evidence from School Inspections in England 2000–2005.” International Studies in Catholic Education 2 (1): 80–94.

- Pius XI. 1931. Quadragesimo anno. https://19310515_quadragesimo-anno.html.

- Redding, S., J. Langdon, and J. Meyer. 2004. The Effects of Comprehensive Parent Engagement on Student Learning Outcomes. San Diego: American Educational Research Association.

- Ressler, R. W. 2020. “What Village? Opportunities and Supports for Parental Involvement Outside of the Family Context.” Children and Youth Services Review 108: 1–7.

- The Sacred Congregation for Catholic Education. 1977. The Catholic School.

- Salkind, N. J. 2008. “Cultural Deficit Model.” In Encyclopedia of Educational Psychology, edited by Neil J. Salkind, Vol. 1, 217–217). Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963848.n60.

- Salvatierra, L., and V. M. Cabello. 2022. “Starting at Home: What Does the Literature Indicate About Parental Involvement in Early Childhood STEM Education?” Education Sciences 12 (3): 218.

- Scanlan, M. 2008. “The Grammar of Catholic Schooling and Radically “Catholic” Schools.” College of Education Faculty Research and Publications 109. https://epublications.marquette.edu/edu_fac/109.

- Sharma, M. 2018. “Seeping Deficit Thinking Assumptions Maintain the Neoliberal Education Agenda: Exploring Three Conceptual Frameworks of Deficit Thinking in Inner-City Schools.” Education and Urban Society 50 (2): 136–154.

- Tessier, R. 2018. Equity in Education: Breaking Down Barriers to Social Mobility.

- Vera, E. M., A. Heineke, A. L. Carr, D. Camacho, M. S. Israel, N. Goldberger, A. Clawson, and M. Hill. 2017. “Latino Parents of English Learners in Catholic Schools: Home vs. School Based Educational Involvement. Journal of Catholic Education 20 (2): 1–29.

- Wang, J., and Y. Wu. 2023. “Income Inequality, Cultural Capital, and High School Students’ Academic Achievement in OECD Countries: A Moderated Mediation Analysis.” The British Journal of Sociology 74 (2): 148–172.

- Weatherley, R., and M. Lipsky. 1977. “Street-Level Bureaucrats and Institutional Innovation: Implementing Special-Education Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 47 (2): 171–197.

- Willemse, T. M., E. J. de Bruïne, P. Griswold, J. D’Haem, L. Vloeberghs, and S. Van Eynde. 2017. “Teacher Candidates’ Opinions and Experiences as Input for Teacher Education Curriculum Development.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 49 (6): 782–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220272.2016.1278043.

- Willemse, T. M., I. Thompson, R. Vanderlinde, and T. Mutton. 2018. “Family-School Partnerships: A Challenge for Teacher Education.” Journal of Education for Teaching 44 (3): 252–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1465545.

- Yu, X., Y. Chen, C. Yang, X. Yang, X. Chen, and X. Dang. 2022. “How does Parental Involvement Matter for Children's Academic Achievement during School Closure in Primary School?” British Journal of Educational Psychology 92 (4): 1621–1637.

- Zwierzchowska-Dod, C. 2022. Books, Babies and Bonding: The Impact of Dolly Parton’s Imagination Library on Parental Engagement in Book-Sharing and on Child Development from 0–5 Years Old. Swansea: Swansea University.