Abstract

This article examines the institutional genealogy of Israeli colonial governance (ICG) and the accompanying patterns of Palestinian resistance in the occupied West Bank and Gaza Strip. It argues that ICG has experienced three phases, each marked by a particular form of direct or indirect colonial rule. Each of these colonial rule forms has been resisted through a distinct pattern of centralized or decentralized collective political agency. I argue that both the form and governing logic of ICG are determined not only by colonialist aims, but also by their interplay with the Palestinian resistance.

In the summer of 1976 Ahmed Qatamesh disappeared and over time seemed to have been forgotten. Then, in 1992, after hiding for sixteen years in the city of Al-Bireh, the Israeli army arrested him. In the summer of 2021, Muntaser al-Shalabi disappeared after carrying out a shooting attack against at an Israeli security checkpoint south of Nablus but was arrested less than four days later near Ramallah. Qatamesh, who in 1976 was a field leader in the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP), disappeared during a phase marked by direct Israeli military rule over the Palestinian territories occupied in 1967 (oPt), while Shalabi, who had spent most of his life in the United States and had no known political affiliation, disappeared during a phase marked by what has come to be known as ‘job sharing’ between the Palestinian National Authority (PNA) and Israel. How did the situation in the occupied Palestinian territories change between 1976 and 1992?

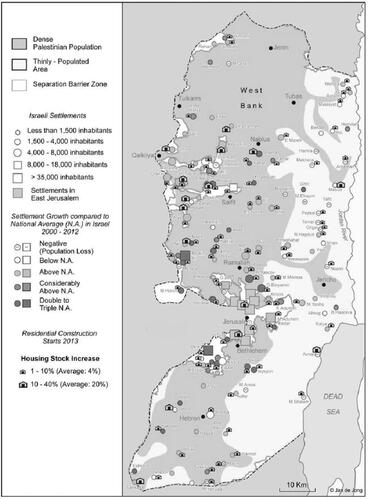

This article traces the metamorphosis of the Israeli Colonial Governance (ICG) over the major population centers in the oPt, and the accompanying shifts in the general pattern of Palestinian resistance. By major population centers, I mean densely populated areas, including the Gaza Strip, and about one-fifth of the West Bank (as illustrated by the map). However, the study’s spatial scope excludes East Jerusalem, which retained a special status throughout the time period of the research.

Map 1. The West Bank in 2014

Source: Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs ‘PASSIA’)

Based on the literature on both governanceFootnote1 and settler-colonialism,Footnote2 Colonial Governance may be defined as the set of interconnected formal and informal institutional systems adopted by a settler-colonial power with the aim of maximizing its control over the indigenous population while minimizing its responsibility for them. Achievement of this aim requires the existence of sustainable violent structures intended to subdue the native population’s political agency. By general pattern of resistance, I mean the prevailing expression of the collective political agency which challenges the ICG.

Several theoretical frameworks have been employed to understand the position of the native political institutions and elites in the Israeli system of settler colonialist rule. Such frameworks include Dependency Theories, Regime ChangeFootnote3 and Historical Structural Development,Footnote4 as well as a wide range of literature on settler-colonialism. For example, Lorenzo Veracini views the PNA from the perspective of the functional roles of indigenous political structures, carries out Diplomatic Transfer, that is, a partial process of decolonization of quasi-sovereign entities in which indigenous people are separated from settler-colonial communities.Footnote5 Mahmoud Mamdani, by contrast, argues that the settlers’ national sovereignty must produce institutional colonial solutions based on indirect rule. He draws lessons from several cases, the most important being South Africa, which shed light on the Palestinian case.Footnote6

Despite the importance of such conceptual frameworks in providing a macro-understanding of how settler-colonial regimes operate, and the place of the indigenous population’s political institutions therein, they overlook the relationship between settler-colonialism and indigenous collective agency.Footnote7 According to Veracini, settler-colonialism is a zero-sum game: Unless it succeeds, it fails. Theorists of Comparative Colonialism, on the other hand, remain captive to comparisons with settler-colonial models, such as that of South Africa, which had no access to the technological revolution since 2000.

Recent scholarship, however, has become aware that exclusively focusing on settler colonialism without ‘engagement with the indigenous can (re)produce another form of “elimination of the Indigenous.”’Footnote8 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury, for example, argues that viewing settler-colonialism not as a structure, nor as an event, but rather as a process, enables ‘simultaneous tracing of both settlement practices and resistance by the indigenous.’Footnote9 In line with these contributions, this study argues that institutional analysis, which expands the concept of ‘institution’ to include informal structures,Footnote10 makes it possible to examine settler-colonial regimes’ interactions with institutional patterns of resistance against them while, at the same time, not ignoring the effects of context.Footnote11

In understanding the metamorphosis of ICG, this study also draws on the literature of origins of direct and indirect rule. Colonial authorities decide to govern through indirect rule depending on many factors, such as the threat of local rebellion (as the case of colonial Mexico)Footnote12, difficult accessibility to the local populations (as the case of colonial rule in African countries)Footnote13 and the degree of political institutionalization among native populations (as the case of British colonies).Footnote14

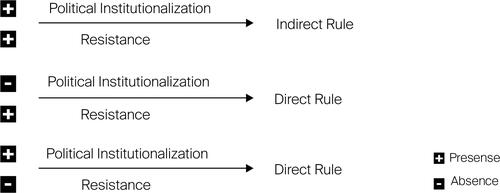

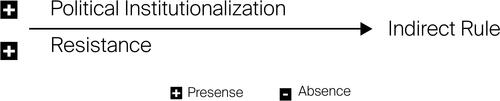

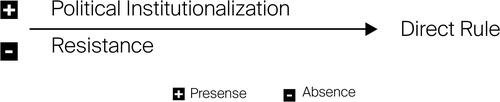

With regard to the case of oPt, this study stresses two basic conditions which both must be met by the ruled in order for their relationship to the ruler to be one of indirect rule. The first condition is an advanced degree of native political institutionalization that is able to monopolize the collective political agency of the native population.Footnote15 The second is that the political institution of the ruled possesses bargaining power, that is, the ability to resist the ruler’s strategies, whether by resorting to violence, or by revolting against the relationship with the ruler.Footnote16 shows the probabilities resulting from the combination of the two conditions, or the absence of one of them.

Both conditions are indispensable for any indirect rule. The absence of the first would mean the impossibility of finding a party with which to negotiate since no one could claim the collective political agency of the population being governed.Footnote17 The presence of the second condition, i.e. the ability of the ruled to resist, is what prompts the ruler to share governance with the ruled, and accordingly, to adopt the formula of indirect rule rather than direct rule.Footnote18 Nevertheless, it should be emphasized that the presence of these two conditions does not lead to any form of sovereign self-rule, which requires other conditions that this study does not purport to address.

The study shows that in the field of spatio-temporal research, ICG has passed through three successive phases, each of which was marked by a dominant pattern of resistance. During the first phase (1967–1994), which will be discussed first, the oPt were ruled directly via colonial military and security apparatuses that lacked the political institutional access to control the Palestinian population. A situation resulted in a pattern of Palestinian resistance of a semi-formal institutional form, represented by the Palestinian organizations that, due to their decentralized nature, posed a dilemma for the ICG.

The second section addresses the second phase (1994–2005), which began with the establishment of Yasser Arafat’s PNA, the Palestinian population centers were ruled indirectly through a relatively well developed and centralized institutional political structure embodied in the PNA, which enjoyed limited self-rule and a near-total monopoly of the collective political agency. This form of governance gave Arafat’s PNA the ability to resist, which prompted Israel in 2002 to launch a military invasion which destroyed, then restructured it in the West Bank. However, this strategy had limited efficacy in Gaza, where the Palestinian organizations were able to endure.

The third section addresses the third phase (2005–), which began with the rise of Mahmoud Abbas to the presidency of the PNA. In this period, Israel utilized high-tech surveillance to integrate the PNA into ICG, depriving it of any bargaining power, which marked a return to direct rule in the West Bank. Meanwhile, the Gaza Strip, where Hamas had accumulated combat capabilities, remained under a form of indirect rule which continues to this day. Consequently, while the dominant pattern of resistance in Gaza can be considered a continuity of the previous phase, ICG in the West Bank, produced a new pattern of anti- institutionalized resistance which manifested itself in the emergence of what could be termed ‘junior leaders,’ who revolted against both the ICG and the idea of political institutionalization.

Phase I: Pre-Oslo Colonial Governance and Its Resistance

By the eve of the outbreak of the First Intifada in 1987, the Palestinian population of the oPt had grown to 1.5 million people. Two-thirds lived in East Jerusalem and the cities, villages and camps of the West Bank, linked together by a backward network of roads. The remaining third lived in the Gaza Strip, which looked more like a series of huge camps that had swallowed up the pre-Nakba city.Footnote19

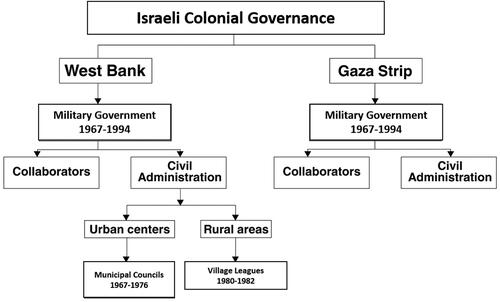

Although the Israeli occupation of 1967 had united these population centers under a single military government, they were—until the early 1980s—not unified on the levels of political elites and socio-economic development, or even on colonial administrative strategies. The Israeli colonial administration was known at the time as the Israeli Civil Administration (ICD). As shown in , Israel occupied the West Bank, which since 1948–49 had been governed by a centralized system administered from Amman, Jordan, and relied for control over the population centers on a broad network of structures, traditional loyalties, and municipal and local councils. Israel also occupied the Gaza Strip in 1967, which at the time was a large refugee camp that lacked traditional structures (these having collapsed with the Nakba and forced displacement), and thus since 1948 had been ruled by Egypt via an independent military government at the administrative level.Footnote20

The ICD was established immediately after the 1967 War. It exercised direct rule over Palestinian population centers in the oPt. However, given the difficulty of imposing direct rule over a group so different from itself ethnically, linguistically and culturally, it strove to develop ICG [ICD?] into an indirect governing apparatus through attempts to separate military action from civil action.Footnote21 For this reason, ICG was characterized from its establishment by an administrative decentralization which assumed that every population group was distinguished from every other by its residents, its elite, and its political culture. Such conception was influenced by an Orientalist conception that refused to consider the Palestinian people as a single nation, but rather as different population groups that could be ruled through traditional and clientelistic structures.Footnote22 Until the mid-1980s, Israel spared no effort to perpetuate and reproduce this situation by severing all possible links with the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in exile, by supporting weak traditional local structures inherited from the era of Jordanian rule in the West Bank, as well as by supporting Islamist networks ideologically opposed to the PLO in Gaza.

This policy began in the West Bank when Israel decided to invest in Palestinian elites affiliated with the Jordanian government, and specifically, to support pro-Jordanian mayors and allow them limited forms of political activity in various urban centers (with the exception of East Jerusalem). Although this policy achieved limited success in the 1972 municipal elections, it failed in the 1976 elections, in which symbols of the Jordanian government were defeated. A new generation of mayors who were more independent and closer to the PLO arose. As a result, the occupation authorities cracked down on and boycotted the new mayors, many of whom were dismissed, and one of whom even endured an attempt on his life.Footnote23

In the early 1980s, Israel attempted to exploit rural-urban social divisions by creating a parallel, traditional rural elite known as ‘Village Leagues’ to counter the rebellion of urban elites, based on the fact that peasants represented 70% of the West Bank population. League representatives were given the ability to mediate with the ICD to obtain permits and licenses. However, the project, which reached its climax under the leadership of then-Defense Minister Ariel Sharon in 1981–82, quickly failed due to the hostility in Palestinian society and Jordan’s decision in March 1982 to consider ‘membership in the Village Leagues to be grand treason.’Footnote24

Meanwhile, in Gaza, Israel implicitly relied on the networks and institutions of the Palestinian Muslim Brotherhood (MB), granting a legal margin to what was known as the Islamic Center to carry out its charitable and social activities on the assumption that such support might help to contain the influence of the PLO organizations. This contributed to strengthening the MB, which took control over an Islamic university with 5,000 students, and 40% of the Gazan mosques.Footnote25 However, by the mid-1980s it had become clear that the Israeli strategy had been a grave error. In practice, it had produced Hamas, an Islamic organization more radical than the PLO organizations. Thus, Israel concluded that would not be possible to exercise indirect rule over any of the major population centers in the West Bank and Gaza Strip.

The Israeli assumption about the political and social fragmentation experienced by the Palestinians of the oPt was essentially correct. However, it was entirely wrong about the possibility of sustaining this state of division. Israel discovered too late that its intelligence lacked a research department to study societal transformations, and that most of its estimates were based either on mere impressions, or on assessments from traditional, uneducated middle elites.Footnote26 What these assessments failed to foresee was that Palestinian population centers would undergo a process of regeneration whereby the 1980s would witness the emergence of a new generation more mobilized, better educated, and more closely connected to the idea of an organized Palestinian nationalism as put forward by the PLO in the Diaspora.Footnote27

Ironically, Israel’s own settler-colonial policies had been largely responsible for this shift. With the rise of the Likud government to power in 1977, the oPt witnessed an increase of de-development policies resulting from Israel’s rapidly accelerating integration strategies. This included the impoverishment and dispossession of the Palestinian labor force that was stripped of work in the local agricultural sector—which at that time constituted the mainstay of the local economy—and forced into cheap wage labor. This paralleled accelerated settlement expansion, with the resultant confiscation of lands and natural resources, and the construction of a network of roads that reflected an ongoing planning which was biased in favor of Jewish settlements at the expense of Palestinian transportation needs. As a result, residents of rural areas, cities and camps alike began to sense the danger of the Zionist project more acutely than ever before.Footnote28

All of this was accompanied by a severe economic crisis which led to a contraction in the Israeli economy. The crisis inevitably impacted the living conditions of Palestinians, of whom more than 120,000 worked in Israeli industrial, agricultural, construction and services sectors, and many were dismissed from their jobs.Footnote29 The crisis also affected Jordan and the Gulf states, which had been a major source of remittances from Palestinian migrant labor.Footnote30 The restrictions imposed by Arab countries on Palestinian immigration for fear of emptying the occupied lands drove the number of young people in the population to over 70%. This resulted in a steady increase in the number of universities and colleges being established to compensate for the difficulty young people were facing in enrolling in educational institutions in Arab countries. Consequently, there was a notable increase in the annual graduation rate from private universities and colleges, fewer than one-fifth of whom were able to find work.Footnote31 Thus, the rising education rate, high levels of marginalization and impoverishment, and a growing national consciousness produced a dangerous social mix that need only a spark to set it ablaze.

The Rise of Palestinian Organizations

On December 8, 1987, an Israeli truck rammed into a group of Palestinian workers in the Jabalia refugee camp north of Gaza City, killing four of them. Their funeral the following day turned into a massive demonstration and led to clashes with the occupation forces in which stones and Molotov cocktails were thrown. This was followed by a series of demonstrations of the same kind which spread throughout the oPt. The Israeli security services initially had expected the demonstrations to be a passing incident, like the protests that had erupted following the announcement of the New Civil Administration in 1981–1982. The earlier protests, led by university students and backed by elected Palestinian mayors, had reached their climax in the last week of March,Footnote32 but had stopped as a result of repression and policies of collective punishment.Footnote33 This time, by contrast, the protests expanded to include all Palestinian population centers and continued without interruption.

Between 1985 and 1987, the number of demonstrations increased by 3,000%, while the number of attacks on Israeli targets went from 351 in 1983Footnote34 to more than 5,000 in each year of the First Intifada.Footnote35 Forty percent of all adults in the oPt have been detained for at least one night.Footnote36 This time, the policy of the iron fist and the collective punishments that Israel imposed on certain towns or cities following the outbreak of popular protests, or the launching of military operations in these locations, did not succeed in containing the uprising. On the contrary, they merely served to increase popular resentment, and created an environment ripe for political mobilization which generated new forms of informal mass organization.

The outbreak of the First Intifada undermined the dominant perception of Israeli policy. The fact that it had not been anticipated was viewed as an ‘intelligence failure’, one reason for which was that the process of collecting intelligence data had relied on a separate database for each Palestinian city and village.Footnote37 The database, which had been constructed based on local networks of collaborators and ICD employees, was founded on an ideological conception that refused to recognize the various Palestinian population centers as a single people. As a result, ICG lacked mechanisms for analyzing overall political developments in the oPt, assuming that they did not constitute a single political unit.Footnote38

The administrative decentralization which the ICG attempted to impose in order to smother collective political agency produced a decentralized pattern of resistance. Palestinian population centers witnessed the formation of resistance organizations (tanzimat), semi-official mass structures which were independent of one another,Footnote39 and which demonstrated efficiency by communicating with youths in the camps and villages.Footnote40 In so doing, these organizations provided new frameworks for the mobilization and organization of broad social segments outside the urban centers which, until recently, had monopolized politics. The widespread Israeli arrests within its ranks helped to make prison an effective space for national, security and organizational education for thousands of their members.Footnote41

Despite these social structures’ extreme decentralization and their lack of horizontal institutional links, this did not prevent them from working in harmony, nor did they lack the means to communicate with the leadership of the PLO command in diaspora and to agree on the establishment of what was known as the Unified Leadership of the Intifada (UNLI). In fact, the decentralized nature of these structures held the secret to their agility, as each of these structures was too large to be ignored, yet too small for a central military bureaucracy to pursue. Thus, by the end of the first year of the Intifada, this vast network of these organizations constituted a complete political infrastructureFootnote42 which directed most of its operations towards paralyzing the ISGC by targeting its institutional channels both materially and symbolically. Materially through the physical liquidation of collaborator networksFootnote43, and symbolically through threats made by the UNLI, which resulted in successive waves of mass resignations among Arab ICD employees.Footnote44 As a result, the majority of Palestinian population centers became, in relation to the ICG, something on the order of ‘black holes’ managed by local popular committees.Footnote45

In light of the state of popular mobilization and the loss of institutional contact with Palestinian communities, a number of Palestinian activists disappeared during the First Intifada and remained missing for many years. Unlike the Palestinian revolutionaries of the 1930s who, in the context of their struggle against the British Mandate forces and Zionists, hid in mountains, caves and thickets, the revolutionaries of the First Intifada disappeared into the very centers of population, frequently hiding in ordinary houses. Their most common tactic was moving constantly from house to house under the protection of a tight-knit, politically mobilized community that was difficult to penetrate. One of the best-known stories preserved in popular memory is that of the 17-year disappearance of Ahmed Qatamesh, leader of the PFLP, with whom this study began.

The First Intifada aborted any possibility of exercising indirect rule over Palestinian communities in the oPt, and in the absence of a Palestinian political institution capable of monopolizing Palestinian collective agency (see ), Israel concluded that the only way to go on ruling would be through a military solution and violent repression.Footnote46 This included the escalation of orders to shoot and break bones. Under then-Israeli Defense Minister Yitzhak Rabin, commands were issued to beat stone-throwers with sticks and break their limbs. The Israeli army also began, for the first time, using advanced technological means, such as helicopters,Footnote47 and assigning plain clothes military units to track down and eliminate Palestinian activists.Footnote48 Another unprecedented measure was the deployment of large numbers of stationary and mobile checkpoints to carry out extensive searches and restrict Palestinians’ movements.Footnote49 Other violent practices included home demolitions, closures of schools and universities, the spreading of rumorsFootnote50 and curfew measures, which were implemented 1,600 times in 1988 alone.Footnote51

In its attempt to quell the First Intifada, Israel killed more than 1,000 Palestinians.Footnote52 However, this came at a significant economic and symbolic cost, a sharp division within Israeli society, global outrage, and an army that had been exhausted both physically and morally.Footnote53 However, despite its imposition of direct military rule, Israel was far from enjoying any stability. The First Intifada had produced a Palestinian society that was more unified and radical than ever before, and its final years witnessed the development of new forms of military resistance which were reinforced by Hamas’s establishment of a central military organization responsible for qualitative operations against Israeli army units.Footnote54 Direct rule, then, was not so much a solution for Israel as it was a dilemma. However, in September 1993, the PLO and the Israeli government signed the Oslo Accords, which came as a relief to Israel.

Phase II: Post-Oslo Colonial Governance and Its Resistance

With legitimacy and popular support, Arafat considered the inauguration of the PNA, immediately after signing the Oslo Accords, the first step on the path to self-determination and state-building. However, Arafat endeavors did not reflect only state-building processes, but also establishing a structure of resistance if Israel reneged on its implied acceptance of the principle of an independent Palestinian state. Arafat thus designed the structure of the PNA in a hybrid manner. It was a nucleus of a future state with a centralized structure, ministries, various government agencies, and a legislative council. On the other hand, its security apparatuses were similar in their overall structure to the forces of the Fatah movement and the PLO in Lebanon. They were centralized and decentralized at the same time. Decentralized in light of their members’ varying social backgrounds, its institutional dispersion, their functional overlap, and their informal communication system, and centralized at the level of each individual security apparatus, and with their institutional relationship exclusively and personally with Arafat.Footnote55

The Palestinian security services were established in accordance with Article VIII of the Oslo Accords, which stipulated the need to restore ‘public order and internal security’ in the oPt through a robust police force. The Cairo Agreement (1994) set their number at 9,000, including 7,000 returnees from the Diaspora and 2,000 locals; and they were to consist of four agencies. The Taba interim agreement (1995) added two other agencies, increased their forces to 30,000, including 12,000 returnees and expanded their areas of control to include the majority of Palestinian population centers known as Areas (A). Furthermore, it stipulated that the security forces be equipped with light arms, and that an arms database be constructed with Israel to ensure their proper monitoring.Footnote56

Despite its untidy organization, the most prominent achievement of this security structure was its containment of the decentralized network of mass organizations that had been active during the First Intifada, and their centralization into a group of security agencies. For example, the Military Intelligence and General Intelligence apparatuses constituted a framework in which returnees were employed, while the Preventive Security Services, as well as the bloated National Security Apparatus, formed the institutional vessel in which Fatah’s local networks were integrated. Such policy had been designed to ensure Arafat control in keeping with the principle of ‘divide and rule’.

In the late 1990s, Arafat’s PNA adopted two strategies: the first was its attempt to impose its hegemony on Palestinian society in the oPt, and to prove its efficiency in monopolizing collective political agency. To this day, many Palestinians still remember the events that took place at the Palestine Mosque in Gaza City in November 1994, when Palestinian security forces dispersed a peaceful demonstration of Hamas supporters with live ammunition, killing 17. They also still remember the arrest and torture campaigns carried out against leaders and members of Hamas and Islamic Jihad, especially after the series of suicide attacks they had carried out in Israel. The PNA also coordinated efficiently with Israel security forces in thwarting many military operations. Security cooperation contributed to dismantling the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, Hamas’ central military organization. By 1998, Arafat had reached understandings with the leaders of Hamas according to which aspects of its military action were to be suspended.

The second strategy Arafat pursued was to expand the margin of maneuver for his security agencies. This was done by violating the limits set in the interim agreements for the number of security personnel allowed and the quality of their armament, as their number swelled from 30,000 to 50,000, although the lists of security personnel were hidden. Arafat also violated coordination with Israel regarding the number and quality of weapons, which, according to one estimate, came to more than 40,000 pieces, including mortars and RPGs, over the allowable number.Footnote57 Moreover, the PNA established additional new agencies, whose number came to twelve by the year 2000 on the eve of the Second Intifada.Footnote58 Finally, security personnel were nationally mobilized, which was the easier task at the time, as the majority of its members were either former fighters returning from Diaspora, or activists who had led the First Intifada. One expression of that was the way in which they reacted to Israeli forces in the popular Tunnel Uprising of September 1996, in which dozens of Palestinians, including security personnel, were killed. At that time, Israel saw the Palestinian security forces, to which it had helped pass weapons, firing on its personnel and killing 17 officers and soldiers. This was an event from which it would take lessons while preparing to face the Second Intifada a few years later.

Thus, by the late 1990s, as shows, the extremely decentralized networks of political structures became organized into a group of centralized security agencies, all of which were directly subordinate to Arafat. These agencies monopolized the collective political agency and possessed a margin of maneuver. However, the confluence of these two conditions was not enough to lead to an independent state. Rather, it was at best, as indicates, a form of indirect rule linked to the ISGC, which was the most the Israeli government would be willing to accept. Thus, with the continuation of the settler-colonial policies, which doubled the number of settlers in the oPt, bringing their number to 200,000,Footnote59 and the collapse of the Camp David peace talks (2000), the political process took another course with the outbreak of the Second Intifada, over which Arafat sought to claim leadership for fear that it would sweep him away.

Turning the Page on Arafat

Within the narrow circle that accompanied Arafat, there is disagreement over the extent of his responsibility for planning or preparing for the Second Intifada. Mamdouh Nawfal and Marwan Kanafani, both of whom played advisory roles, assert that its outbreak was sponsored and planned by him,Footnote60 while according to Ahmed Qurei, Arafat found himself forced to lead it in order to cut off ‘opposing Palestinian forces’ (by which he meant Hamas) who wanted to ‘strengthen their political presence, and present their program as an alternative plan to that of the PNA.’Footnote61 However, the majority point of view is that Arafat—perhaps like others—anticipated the Second Intifada, and sought to make use of it in order to pressure Israel to accept his interpretation of the Oslo Accord, that is, to give the Palestinians a viable state with East Jerusalem as its capital. However, his attempt did not bear fruit due to miscalculation, poor preparation, and most importantly, the shift that had taken place in collective political agency—a shift which he himself had helped to bring about.

Arafat’s miscalculation involved a mistaken reading of the regional and international situation after the end of the Cold War and the rise of the neo-conservatives in the United States. The situation became worse in the second year of the Intifada after the attacks of September 11, 2001, which created an international atmosphere that had no tolerance for the use of violence to bring about political change. Consequently, the then-US President George W. Bush demanded that the Palestinians reform the PNA, dismantle armed organizations, and elect new leadership for the PNA.Footnote62

The poor preparation lay in Arafat’s reliance on the loyalty of his Fatah base, and on the cooperation of other Palestinian organizations. Since the beginning of the Intifada, Arafat had established the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades, the majority of whose members were either employed by the security services, under their protection, or informally linked directly to him.Footnote63 He also ordered the leaders of the security apparatuses to turn a blind eye to the arming of other organizations, especially Hamas and Islamic Jihad, as well as the PFLP, in the hope of containing them.Footnote64

However, Arafat had been wrong in his estimates. In the second year of the Intifada, it seemed as though the Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, whose groups had multiplied after the collapse of the security services and the weakening of their leaders, were rebelling against him and not accepting his political management of the Intifada. This was manifested via many groups’ insistence on continuing armed resistance at times when he needed calm and a willingness to negotiate. The reason for this was that the Fatah base, consisting primarily of local Fatah members, was resentful of the patronage system that favored returnees at locals’ expense. Not only did this division lead to political and military failure, but also it helped Israel to isolate Arafat when Ariel Sharon succeeded during the third year of the Intifada in convincing the US Administration that Arafat no longer was in control of Fatah and needed to be replaced by someone who could impose the needed control.Footnote65

Arafat also underestimated the size of Hamas and its ability to benefit from the Intifada. His decision to enter into a confrontation with Israel without having resolved his conflicts with it had dire consequences. When the Second Intifada broke out, Hamas had no reason to trust Arafat and his political administration. It could not have been expected to grant him its trust quickly, especially since the majority of its leaders and members only recently had emerged from a bitter experience under the lashes of his security apparatuses. Indeed, Hamas never had acknowledged Arafat’s legitimacy as a political authority and was not about to sign onto an adventure that might result in a political ceiling—that is, the Oslo Accords—that it would reject. Thus, Hamas ingeniously and rapidly rebuilt its organization from the ground up. Within one year, after the Intifada had turned to suicide operations, Hamas was able to come to the fore, and its leadership was acknowledged as having the final say in decisions concerning calm vs. confrontation.

Of equal importance is the shift that took place in the structure of collective political agency. The process of political institutionalization on which Arafat had embarked in the 1990s, and the concomitant centralization of the networks of Palestinian organizations in the various Palestinian population centers in the oPt, had robbed the collective political agency of its most important source of strength, flexibility and resilience in the pre-Oslo era, namely decentralization. Consequently, this resulted in the institutionalization of a new pattern of resistance which, unlike its predecessor, was slow-moving and easy to pin down. By the end of March 2002, the Sharon government had defined the Intifada as a war, after which it found it easy to use the assassination of Israeli Minister of Tourism Rehavam Ze’evi and the suicide operations being carried out as pretexts justifying the invasion of Palestinian population centers. Sharon then isolated these centers from each other, besieged Arafat in his Ramallah compound, and isolated him from his security services. They were then targeted by aerial bombardment,Footnote66 and many of its members arrested and disarmed in a humiliating manner. Thus, by mid-2003, Israel had captured Arafat’s PNA.Footnote67

As for the other resistance organizations, which quickly had reorganized themselves in the first year of the Second Intifada, Israel confronted them with what it called a strategy of ‘beheading the snakes,’ as its security services focused on killing and arresting their leaders using guided missiles and booby-trapping techniques. Little by little, resistance organizations in the West Bank were depleted, and their leadership capabilities paralyzed. However, this strategy failed in Gaza, from which Sharon was obliged to withdraw in the summer of 2005.

Thus, as the Second Intifada entered its death throes, the oPt witnessed a successive collapse of the PNA’s institutions, prompting its terrified political elite to call on Mahmoud Abbas to manage the defeat. Abbas led a call for reform and an end to Arafat’s one-man hold on decision-making. This call was supported by the US through the Road Map plan introduced in April 2003. It was thus clear that both the US and Israel had decided to isolate Arafat politically by imposing a ‘reform’ that was supported by various Palestinian political elites, each for their own reasons. Thus, a paradoxical situation arose. While the Abbas’ faction, which were supported by the Fatah movement’s political majority, refused to exclude Arafat politically, they were, at the same time, enthusiastic about the steps being taken by Israel and the US to do this very thing. This contradiction might not have been resolved peacefully had it not been for Arafat’s mysterious death in November 2004, which allowed his successors to relegate him to the past while paying him lip-service as a martyr and a symbol of the resistance.

Phase III: Post-Intifada Colonial Governance

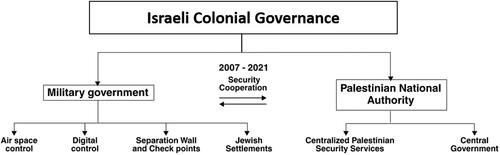

The principal lesson which Israel learned from the experience of the Second Intifada was not to trust any autonomous institutional structure to administer the affairs of the oPt. Since Abbas came to power (2005), successive Israeli governments in cooperation with the US have been keen to redefine the concept of ‘state building’ and to strip it of its political content, confining it instead to a set of technical and administrative criteria. The new PNA becomes, in the words of Tawfiq Haddad, ‘an anti-politics machine.’Footnote68

In the West Bank, Israel has employed highly advanced technology to develop what Jeff Halper terms a ‘Matrix of Control’ which manages and controls Palestinian activity in space and timeFootnote69 through a set of interconnected, interdependent surveillance systems which form an occupation that is at once horizontal and vertical. This matrix includes: 1) a separation wall extending hundreds of kilometers and equipped with electronic fences and monitoring and alarm devices;Footnote70 2) a territorial division and isolation of Palestinian communities via a network of settlements that constitute security fortresses both digital and geographical;Footnote71 3) a network of fixed and temporary military checkpoints which gather and analyze the biometrics of the Palestinians who regularly pass through them with the latest digital technologies;Footnote72 4) a drone program that controls the airspace;Footnote73 and 5) a comprehensive digital occupation of telecommunications networks and the Internet.Footnote74 All of the foregoing are undergird, moreover, by a set of special military laws that are being constantly updated.Footnote75

All of these systems physically and technically combine to control Palestinian communities in the West Bank. Physically through highways and bypass roads, and technically via advanced systems of high-quality surveillance cameras, and smart software capable of analyzing and predicting collective and individual movement patterns, and locating human elements that represent security threats.Footnote76 Thus, while ICG before the Second Intifada relied mainly on indirect rule of the population, technological advances have enabled Israel to control the Palestinians in their confined spaces in a selective and computerized manner, thereby making Israel less dependent on the PNA than it was in the Arafat era. In sum, high-tech has turned the West Bank into one of the largest control laboratories ever. It even has enabled Israel to market this model globally as a ‘brand’,Footnote77 making its occupation of the Palestinians so economically profitable that it has been referred to as a ‘neoliberal occupation’.Footnote78

On the other hand, the Palestinian commitment to security cooperation with Israel under direct US and European supervision has led to the digitization of security coordination in such a way that it has become difficult, if not impossible, to break free from it. Before the Second Intifada, the exchange of information between the PNA and Israel was limited to what Arafat chose to allow. This would take place through a joint security committee composed of representatives of the various branches of his security services, while Israeli security incursions were limited to rare cases of ‘hot pursuit.’Footnote79 Given the relatively underdeveloped capabilities of Israel’s surveillance systems, as well as their institutional dispersion of intelligence at that time,Footnote80 the security coordination process depended on Arafat’s personal willingness to share information, which gave him a margin of maneuver. Suffice it to recall that Israel only succeeded in condemning Marwan Barghouti, a leader of Fatah’s Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigades, by invading Ramallah, where it seized documents containing orders personally signed by Arafat to finance an armed Fatah group.Footnote81

This ceased to be possible in the era of Mahmoud Abbas. Since 2007, not only have coordination mechanisms been developed across eight regional offices staffed by both Palestinian and Israeli officers,Footnote82 but the Palestinian government has been forced to implement an ‘administrative reform’ plan whereby all security, administrative and civil databases have been digitized and linked to Israel under the supervision of international corporations which guarantee an immediate and comprehensive flow of information. Thus, it can now be said that security information reaches the Israeli security services and their Palestinian counterparts simultaneously.

Of equal importance is the comprehensive ‘security reform’ of the Palestinian security services, through which a new generation of security personnel were trained in the principles of maintaining order, combating riots and counter-terrorism instead of being nationally mobilized.Footnote83 Finally, the PNA under Abbas has been able, in coordination with Israel, to contain the elements of the second and third ranks of the Al-Aqsa Martyrs’ Brigades who were active in the Second Intifada, and to integrate them into the intelligence services’ hierarchy. This created a strange situation, as many Palestinian activists held in the PNA's detention centers were videotaped in interrogations being conducted by their former comrades in Israeli prisons.Footnote84 One report estimated that security coordination succeeded in thwarting more than two hundred operations against the occupation forces between October 2015 and January 2016 alone, and reduced the number of individual operations during the Knife Intifada by nearly 90% before the end of 2016.Footnote85

As shows, Israeli technological superiority has transformed the West Bank into a monitoring and control laboratory, while the comprehensive restructuring and administrative reorganization of the PNA has led to its being incorporated into ICG. The digital infrastructure of Ramallah’s PNA has come under the control of the Israeli government, thus depriving it of any ability to maneuver. This is why despite popular pressure and the decisions of the PLO Executive Committee and the Revolutionary Council of Fatah, the new PNA would be unable to halt or even freeze security coordination with Israel.

By employing a highly developed security matrix, and through security coordination with the PNA, the ICG succeeded in dismantling the Palestinian organizations in the West Bank. While, as indicated above, Palestinian resistance fighters during earlier periods had been able to disappear for years on end, the time period required for their arrest or assassination shrank under Mahmoud Abbas to somewhere between one day to several months at most (see below). For example, in March 2011, Israel arrested two Palestinian youths only three weeks after they carried out a stabbing attack in the Itamar settlement south of Nablus, and ten years later, in May 2021, it arrested Montaser Shalabi near Ramallah just four days after he had carried out a shooting attack at the West Bank’s Za’tara military checkpoint even though he had no record of previous political activity.

Table 1. List of most notable individual resistance operations (2011–2021)

When arresting or liquidating resistance fighters, Israeli security services employ a set of strategies, the most important of which is to encircle the villages surrounding the site of the operation, carry out mass arrests and interrogations, conduct mass DNA tests, and analyze huge numbers of photos and video footage filmed by cameras located along roadsides and borders around settlements, as well as cameras confiscated from the owners of Palestinian commercial establishments. Similarly, they would sift through huge volumes of data derived from wiretapping and social media, and from the ongoing security coordination with the PNA.

Nevertheless, although the Israeli matrix of control stifled the collective political agency in the West Bank more than ever before, it did not eliminate it but, rather, led to the emergence of new forms of resistance which made use of material and technical capabilities at their disposal, thus constituting a new pattern of their own. The first form of this pattern, which involved stabbings and car-rammings in areas of friction with the occupation forces, peaked between October 2015 and December 2017 in a broad range of separate individual incidents that were popularly known as the ‘knife intifada.’ Israeli analyses claimed that 420 Palestinians, with an average age of 22 years, carried out, or attempted to carry out, operations of this kind, the majority of them in areas of friction with Israeli soldiers in Jerusalem and Hebron, and one Israeli study estimated that about one-fifth of the perpetrators were women.Footnote86

As for the second form of this pattern of resistance, it consisted in the emergence of youth action groups of a political-cultural nature which relied primarily on social media platforms to engage in education, political mobilization, and criticism of the practices of Abbas’ PNA. Such groups communicated with a broad audience, both Palestinian and Arab, inside and outside historic Palestine. The young Jerusalemite Baha Alyan was known for organizing reading chains around the walls of the Old City of Jerusalem before he carried out a stabbing attack on an Israeli bus in October 2014. A second example is the group led by Basel Al-Araj in Ramallah who, after his liquidation by a special Israeli force in the city of Al-Bireh in March 2017, became an icon of the Palestinian resistance. In the events that took place in the various regions of historic Palestine in May 2021, these groups demonstrated notable effectiveness in pressuring, mobilizing and influencing world public opinion.

This pattern differs from the one that preceded it between the two Intifadas in that it lacks the political and organizational cover that was provided by Palestinian organizations. It involves individual, spontaneous acts of armed resistance which, due to their individual and spontaneous nature, cannot be kept in check by the matrix of control. Alternatively, they may grow out of small networks led by charismatic ‘junior leaders’ with experience in networking and the use of social networks for mobilization and influencing. The new forms have a shared suspicion of formal institutional frameworks, and an emphasis on discourse rather than strategy; as such, they evince a notable resemblance to the modern patterns of protest that emerged during the Arab revolutions.Footnote87 Realizing this fact, Israeli security services have extended their intelligence activities into the Palestinian digital realm. Of note in this context is the campaign of arrests launched against Palestinians between 2014 and 2017 due to posts or comments on social media.Footnote88

The Death Matrix in Gaza and Its Resistance

Unlike the West Bank, where Israel largely succeeded in dismantling the Palestinian organizations by the end of the Second Intifada before liquidating them entirely in cooperation with the new PNA, the organizations’ structure in Gaza were less affected. In fact, they might be said to have become more developed in terms of organization, armament, coordination and command than they had been before. This is due in part to the nature of the Gaza Strip, which represents a near-continuous chain of tightly packed and densely populated refugee camps. A fact that would make an Israeli land invasion similar to the 2002 Operation Defensive Shield in the West Bank impossible, both politically and military.

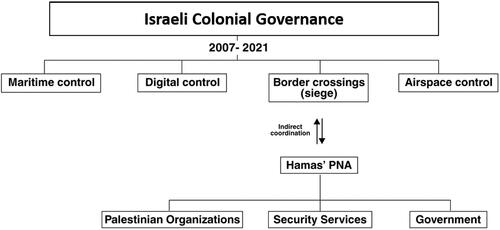

This is what made the ICG take a different form in Gaza. After Israeli disengagement from Gaza in summer 2005, Israel’s land occupation was replaced with a three-dimensional occupation: aerial, maritime and digital, effectively turning Gaza into an ‘Urban Warfare Laboratory,’ in which land and sea borders constantly are militarized. Ever since, the Israeli Air Force has made continuous raids on sites of resistance and civilian residential communities. In major operations, these raids are accompanied by massive, calculated ground invasions, as happened in the years 2006, 2008–2009 and 2014.Footnote89 In the 2014 operation, in particular, the first use was made of a camera system capable of obtaining comprehensive, high-quality visual contentFootnote90 to guide artillery and move tanks.Footnote91

While tightening its control over the maritime borders of the Gaza Strip through naval and air systems in which airplanes, boats, war submarines and military satellites operate in close harmony at the expense of the Gazan maritime economy, Israel has converted the two border crossings under its control (the Beit Hanoun crossing for travelers, and the Karni crossing for commercial goods) into military centers through which it develops its population database, exploiting people’s needs to travel and seek medical treatment in order to recruit collaborators in its war on the resistance.Footnote92 However, the most important function of these crossings is to tighten the economic blockade, which prevents the entry of hundreds of basic commodities: from building materials to particular types of chocolate. Israel even can calculate the average number of calories a Palestinian needs per day to survive.Footnote93 As Israel baldly admits, the purpose of these policies of collective punishment is to barter life for calm—in other words, to allow people barely to subsist in exchange for their passivity.

Between January 2008 and October 2021, successive Israeli military operations led to killing more than 5,900 people, wounding more than 130,000, destroying tens of thousands of homes, and shattering the Gazan infrastructure and industrial and economic backbone.Footnote94 The economic blockade, which has been in place for more than fifteen years, is leading to the slow, daily execution of more than 1.5 million Palestinians. Hence, while in the West Bank, Israel has designed a matrix of control, it compensated for its absence in Gaza with a matrix of death; a matrix that constantly produces ‘debility,’: ‘the slow wearing down of populations instead of the event of becoming disabled.’Footnote95

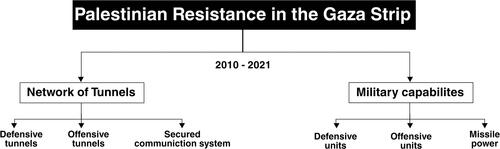

However, despite the vertical and horizontal layers of occupation and siege, resistance organizations, led by Hamas, have used the primitive capabilities at their disposal, including the remnants of unexploded Israeli missiles and parts of settlement sewage pipes, to engage in a military ‘race of deterrence.’ In so doing, the resistance has developed unique security capabilities that have enabled it to maneuver and achieve important political and symbolic gains that have strengthened its presence in Palestinian politics as demonstrated recently in the ‘Sword of Jerusalem’ Battle of May 2021.

It should be remembered that this did not happen overnight. The Gaza Strip, at least since the 1980s, has been considered the most important stronghold of both Hamas and other PLO organizations. However, the history of the Hamas movement’s control over Gaza and its political institutions began specifically in the latter stages of the Second Intifada, when it was able to rebuild its military organization that had been dismantled by Arafat’s Authority in the 1990s.

After the Israeli army’s disengagement carried out by the Sharon government in the summer of 2005, Hamas won the legislative elections of January 2006 and formed a government that has been boycotted both internally and internationally. The majority of Hamas governmental authorities then were removed in decisions signed by Abbas. This caused the outbreak of bloody clashes which escalated into a full-blown confrontation between security services affiliated with Abbas’ Authority and Fatah military groups on one side, and Hamas forces and their allies on the other, leaving more than 400 Palestinians dead. Eventually, Hamas extended its control over Gaza’s political, administrative and security institutions, many of whose employees resigned, to be replaced by others loyal to it. Since that time, an institutional structure has developed in Gaza, where an Authority with administrative headquarters and security services operates side by side with the Palestinian resistance organizations. By monopolizing the collective political agency there, this institutional structure has come to resemble the institutional structure that Arafat built after Oslo, its ongoing presence being one of the most salient features of the Palestinian division today.

However, Hamas’ seizure of control over the PNA's institutions proved no more difficult than it would be to maintain it. Israel immediately classified the Gaza Strip as a ‘hostile entity,’Footnote96 and less than two years later, in the winter of 2008–2009, it was the target of the most comprehensive military aggression up to that time. War planes attacked Gaza’s PNA buildings, including the police headquarters, and in the first few seconds of the operation, more than two hundred policemen were killed. In the weeks that followed, residential communities, schools, hospitals, and the power station were subjected to aerial bombardment and barrages of artillery. Israeli army brigades headed by Merkava 4 tanks penetrated the Strip from all directions, wreaking havoc everywhere, in a policy which could be described, at best, as Urbicide.Footnote97 For the Israeli army, the aggression launched that winter was more or less a picnic. However, the major military operations of 2012, 2014 and 2021 would prove to be otherwise.

The fall of the regime of former Egyptian President Hosni Mubarak following a popular revolution in February 2011 opened a breach along the western borders of Gaza, thus facilitating the resistance’s military and material supply lines. This state of affairs peaked in mid-2012 with the accession of Mohamed Morsi to the presidency in Egypt. In this short period, which ended with a military coup (July 2013) in Egypt that brought in a regime more hostile to Hamas than even Mubarak’s had been, the resistance managed to accumulate various types of military equipment and build up technical expertise which enabled it to develop its missile capability, and during a battle in November 2012 that lasted less than a week, a Hamas missile with a range of over seventy kilometers was able for the first time to reach the city of Tel Aviv ( and ).

However, the most prominent manifestation of what the resistance had accumulated came in the Summer 2014 war, which lasted for seven weeks, and revealed: 1) a network of fortified and highly ramified tunnels hundreds of kilometers in length which were described as an underground city equipped with communication and coordination rooms, and many of those offensive tunnels penetrated the eastern borders of the Strip; 2) a more advanced missile capability with a range of over 160 kilometers (in the war of 2021, the range had increased to 250 kilometers); 3) a parallel network of groups of fighters capable of raining thousands of mortar shells on the Israeli forces located along the borders of the Strip, and of sniping at soldiers from behind the security fence; 4) a network capable of waging urban warfare; and 5) groups trained to carry out special combat missions behind Israeli army lines and by sea. Whereas Israel did not lose a single soldier in the 2008–2009 winter operation, the summer 2014 operation witnessed the loss of about seventy Israeli troops, including 13 elite soldiers who fell in a single operation in the Shejaiya neighborhood.Footnote98

Of no less importance, however, was the ability of the resistance to establish a communications network that could be scaled continuously against hacking, thus limiting the effectiveness of the digital occupation and Israel’s dominance over the digital infrastructure, while reinforcing its need to recruit collaborators and send special units to plant wiretapping devices in local communications lines. The last incident to occur in this connection was the accidental discovery of such a device in Khan Yunis in November 2018. Moreover, Hamas’ having taken control over the PNA in Gaza undoubtedly played an important role in preventing the sharing of biometric and civil population records with Israel. For unlike the West Bank which, since the restructuring and administrative reform operation in 2007, had become exposed on all levels to the ICG, Hamas’ coming to power in Gaza during the same period deprived Israel of its most valuable means of pursuing effective bio-political policies there.

In sum, Hamas was able to build a political institutional structure in Gaza after 2007 that monopolized collective political agency there. Unlike its rival in the West Bank, it accumulated military capabilities (see ) which provided it with a margin of autonomy and maneuvering room. However, as shown in , its realization of the dual conditions of monopoly and resistance resulted in a form of indirect rule under the ICG.

Conclusions

Utilizing an institutional approach, this study offers a conceptual framework to understand the shifts which have taken place in ICG since 1967, as well those that have occurred in patterns of Palestinian resistance to it in the oPt. These shifts have been traced across three successive stages, with emphasis on the need to meet two prerequisites in order for the relationship between the ICG and the Palestinian population to be one of indirect rule: the existence of a Palestinian political structure that monopolizes collective political agency, and this structure’s ability to resist. This postulate is justified by the consideration of the pre-Oslo period as a model of direct rule (despite Israeli attempts to establish formulas for indirect rule), the brief Oslo years as a model of indirect rule, and the post-Intifada as a model of direct rule in the West Bank and indirect rule in the Gaza Strip. In each of these stages, the ICG has interacted with a general pattern of resistance: decentralized in the first stage, centralized in the second, and in the third: decentralized in the West Bank, and centralized in Gaza.

In contrast to the prevailing trend in settler-colonial literature, which restricts analysis to the structure of settler institutions, this study shows that the mechanisms, forms, and ruling logic of ICG depend not only on the strategies of the colonial institutions, but, in addition, on their interaction with the institutional patterns of Palestinian resistance. In other words, it has been shown that the forms of ICG have varied from one time to another, and from one place to another, not only as an output of the strategies settler-colonialism, but also as an institutional response to the Palestinian resistance.

The study also reveals the problem that arises when the literature of comparative colonialism ignores the role of the technological revolution, especially when comparing Israeli settler-colonialism to the apartheid regime in South Africa. For example, contrary to Mamdani’s suggestion that settlers’ national sovereignty forces them to seek institutional solutions based on indirect rule, the evidence presented by this study indicates that highly advanced technology is now enabling Israel to rule the Palestinians directly, at least in the West Bank, through its high-tech integration of the Palestinian institutional structure into its ICG. Indeed, the deadly institutional violence with which Israel targets Gaza may indicate that the structure of the settler-colonial regime favors direct rule, and that when it fails to impose such rule, it compensates for this failure through a vicious cycle of horrific and deadly institutional violence. In order to verify this assertion, however, further research is required.

Disclaimer Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. I express gratitude to my colleague, Maryam Hawari, who provided insight and expertise that greatly assisted the research. I also would like to express my very great appreciation to Nadim Rouhana for his valuable and constructive remarks on an earlier draft of this article. I am also grateful for the insightful comments offered by the anonymous peer reviewers, which have improved this article and saved me from many errors.

Notes

1 G. Hydén, J. Court & K. Mease (Citation2004) Making Sense of Governance: Empirical Evidence from Sixteen Developing Countries (Boulder: Lynne Rienner Publishers), p. 16.

2 Patrick Wolfe (Citation2006) Settler-colonialism and the Elimination of the Native, Journal of Genocide Research, 8(4), pp. 387–409.

3 Ibrahim Shikaki (Citation2021) The Political Economy of Dependency and Class Formation in the Occupied Palestinian Territories Since 1967, in: Alaa Tartir, Tariq Dana & Timothy Seidel (eds) Political Economy of Palestine: Critical, Interdisciplinary, and Decolonial Perspectives, pp. 49–80 (London: Palgrave Macmillan).

4 Nigel Parsons (Citation2005) The Politics of the Palestinian Authority: From Oslo to al-Aqsa (London: Routledge), p. 3.

5 Lorenzo Veracini (Citation2010) Settler-colonialism: A Theoretical Overview (London: Palgrave Macmillan), p. 45.

6 Mahmoud Mamdani (Citation2020) Neither Settler nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), pp. 250–326; Tariq Dana (Citation2021) Israeli Conception of ‘Peace’ as Indirect Colonial Rule, in Jürgen Mackert, Hannah Wolf & Bryan S. Turner, The Condition of Democracy: Vol. 3, pp.71–89 (Oxford: Routledge).

7 Rana Barakat (Citation2018) Writing/ Righting Palestine Studies: Settler-colonialism, Indigenous Sovereignty and Resisting the Ghost(s) of History, Settler-colonial Studies, 8(3), pp. 349–363.

8 J. K. Kauanui (Citation2016) “A Structure, Not an Event”: Settler Colonialism and Enduring Indigeneity. Lateral, 5(1). Available at https://www.jstor.org/stable/48671433, assessed July 10, 2022.

9 Areej Sabbagh-Khoury (Citation2022) Tracing Settler Colonialism: A Genealogy of a Paradigm in the Sociology of Knowledge Production in Israel, Politics & Society 50(1), pp.44–83; Nadim N. Rouhana (Citation2021) Religious Claims and Nationalism in Zionism Obscuring Settler Colonialism, in: Nadim N. Rouhana and Nadera Shalhoub-Kevorkian (eds) When Politics Are Sacralized: Comparative Perspectives on Religious Claims and Nationalism, pp. 54–87 (Cambridge University Press).

10 James G. March & Johan P. Olsen (Citation2008) Elaborating the “new institutionalism, in: R. A. W. Rhodes, Sarah A. Binder & Bert A. Rockman, The Oxford Handbook of Political Institutions, pp. 3–20 (Oxford: Oxford University Press).

11 Kathleen Thelen (Citation1999) Historical Institutionalism in Comparative Politics, Annual Review of Political Science 2(1), pp. 369–404; Paul Pierson & Theda Skocpol (Citation2002) Historical Institutionalism in Contemporary Political Science, Political Science: The State of the Discipline, 3(1), pp. 1–32.

12 Francisco Garfias & Emily A. Sellars (Citation2021) From Conquest to Centralization: Domestic Conflict and the Transition to Direct Rule, The Journal of Politics 83(3), pp. 992–1009.

13 Mahmoud Mamdani (Citation2012) Define and Rule: Native as Political Identity (Cambridge: Harvard University Press).

14 J. Gerring, D. Ziblatt, J. V. Gorp & J. Arévalo (2011) An institutional theory of direct and indirect rule, World politics 63(3), pp. 377–433, p. 377.

15 Ibid, p. 414.

16 Ibid, p. 385.

17 Ibid, p. 414.

18 Ibid, p. 385.

19 Wael R. Ennab (Citation1994) Population and Demographic Developments in the West Bank and Gaza Strip until 1990, United Nations Conference on Trade and Development, UNCTAD/ ECDC/SEU/ 1: 1-100, June 1994. Available at https://bit.ly/3awTTOg, accessed October 12, 2021.

20 Shlomo Gazit (2003) Trapped Fools: Thirty Years of Israeli Policy in the Territories (London: Frank Cass Publishers), pp. 27–28.

21 Geoffrey Aronson (Citation1978) Israel's Policy of Military Occupation, Journal of Palestine Studies, 7(4), pp. 79–98. Ronald Ranta (Citation2015) Political Decision Making and Non-Decisions: The Case of Israel and the Occupied Territories (New York: Palgrave Macmillan).

22 Salim Tamari (Citation1983) In League with Zion: Israel's Search for a Native Pillar, Journal of Palestine Studies, 12(4), pp. 41–56.

23 Gazit, pp.167–187.

24 Benvenisti, The West Bank Data project, pp. 144–151.

25 Hani Awad (Citation2020) Understanding Hamas: Remarks on Three Different and Interrelated Theoretical Approaches, Siyasat Arabia 8(4), pp. 24–44, (in Arabic).

26 Shlomo Gazit (2003) Between Warning and Surprise: On Shaping National Intelligence Assessment in Israel, Memorandum No. 66 (Tel Aviv: Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies at Tel Aviv University), pp. 37–38 (in Hebrew).

27 Baumgarten, p. 311.

28 Benvenesti, p. 80.

29 Baruch Kimmerling (Citation2003) The Palestinian People: A History (Cambridge: Harvard University Press), pp. 294–295.

30 Ibid., pp. 294–295.

31 Yezid Sayigh (Citation2002) Armed Struggle and the Search for a State: The Palestinian National Movement, 1949-1993 (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies), p. 849.

32 Gazit, Trapped fools, pp. 230–232.

33 Hazem Jamjoum (Citation2012) The Village Leagues: Israel’s native authority and the 1981-1982 Intifada, MA thesis, American University of Beirut, p. 28.

34 Sayigh, Armed Struggle, p. 850.

35 Ephraim Lapid (2017) An “Intifada” that ended in a controversial agreement, Israel Defense, December 14, 2017 (in Hebrew), available at https://bit.ly/3EUI95k, accessed November 7, 2021.

36 Sayigh, Armed Struggle, p.849.

37 Ron Ketari (2018) Israeli Intelligence in the First Intifada: the 30th anniversary of its eruption, The Center for Intelligence Heritage, 4, (in Hebrew).

38 Gazit, Trapped fools, pp. 37–38.

39 Helga Baumgarten (Citation2006) From Liberation to the State: History of the Palestinian National Movement 1948–1988 (Ramallah: Muwatin), p. 317 (in Arabic).

40 Lisa Taraki (Citation1989) Mass-Organization in the West Bank, in Naseer Aruri (ed) Occupation: Israel over Palestine, pp. 431–463 (Belmont: Association of Arab-American University Graduates).

41 Sayigh, Armed Struggle, p. 850.

42 Baumgarten, From liberation to the State, p. 312.

43 Salim Tamari (Citation1990) The Risks of being Banal: Limited Defiance and Civil Society, Journal of Palestinian Studies – Arabic Edition 1(3), pp. 12–25.

44 Khaled Abu Hudaib (Citation1990) The Effect of the Intifada/Uprising in Detaching from the Occupation Authorities, Journal of Palestinian Studies – Arabic Edition 1(1), pp. 256–272.

45 Ibid.

46 Samir Jabbour (Citation1990) The Israeli Army Versus the Intifada, Journal of Palestinian Studies – Arabic Edition 1(1), pp. 204–227.

47 Ibid.

48 Elia Zureik & Anita Vitullo (Citation1992) Israeli ‘Death Squad’’s Toll of Death, Journal of Palestinian Studies – Arabic Edition 3(2), pp. 102–131.

49 Stuart A. Cohen (Citation1994) How Did the Intifada Affect the IDF?, Journal of Conflict Studies 14(3), pp. 7–22.

50 Ahmad As’ad and Munir Fakhr Eldin (Citation2021) The Israeli Control over the 1967-Occupied Palestinian and Syrian Lands, in Munir Fakher Eldin et al. (eds) The General Survey of Israel 2020, pp. 887–966 (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies), (in Arabic).

51 Laleh Khalili (Citation2010) The Location of Palestine in Global Counterinsurgencies, International Journal of Middle East Studies 42(3), pp. 413–433.

52 Ben White (2017) Facts about the First Intifada, Middle East Monitor, December 9, 2017. Available at https://bit.ly/3xdzp6V, accessed November 7, 2021.

53 Azmi Bishara (Citation1989) The Uprising’s Impact on Israel, in Zachary Lockman & Joel Beinin (eds) Intifada: Palestinian Uprising Against Israeli Occupation, pp. 217–230 (Toronto: Between the Lines).

54 Bilal Shalash (Citation2015) Transformations of Hamas Movement’s Armed Resistance in the West Bank during the al-Aqsa Intifada from Centralization to Exploding Fragmentations, in The Palestinian Issue and the Future of the National Palestinian Project, vol. 1 (Doha: Arab Center for Research and Policy Studies) (in Arabic).

55 Neri Zilber & Ghaith Al-Omari (Citation2018) State with No Army, Army with No State: Evolution of the Palestinian Authority Security Forces 1994-2018 (Washington D.C.: The Washington Institute for Near East Policy), pp. 7–8.

56 Ibid., p. 5.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 Jeremy Pressman (Citation2003) The Second Intifada: Background and Causes of the Israeli-Palestinian Conflict, Journal of Conflict Studies, 23(2), pp. 114–141, p. 120.

60 Marwan Kanfani (Citation2007) The Hope Years (Cairo: Al-Shorouk press), pp. 332–334, 383, (in Arabic); Mustafa Barghouti et al. (2001) Views on the Intifada and its Objectives (Symposium),” Journal of Palestinian Studies – Arabic Edition 12(3). Available at https://bit.ly/3qc0AOZ, accessed November 7, 202became1.

61 Ahmad Quray’ (Citation2011) The Complete Palestinian Account of the Negotiations: From Oslo to Annapolis, vol. 3, The Road to the Roadmap, 2000-2006 (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies), p. 47, (in Arabic). It should be noted that those disputes were found in Israeli sources as well. See: Zaki Shalom and Yoaz Hendel (Citation2005) The unique features of the Second intifada,” Military and Strategic Affairs 3(1), pp. 17-26.

62 Husam Mohamad (Citation2015) President George W. Bush's Legacy on the Israeli-Palestinian ‘Peace Process’, Journal of International and Area Studies 22(1). Available at: https://bit.ly/3BYfVol, accessed November 7, 2021.

63 Zilber and Al-Omari, State with no Army, pp. 20–21.

64 Ibid, pp. 12–13.

65 Mahmoud al-Natoor (Citation2014) Fateh Movement: Between Resistance and Assassination, vol. 2: 1983-2004 (Amman: Dar Al Ahlia for Publishing & Distribution), pp. 531–532, (in Arabic); Mohammad Yousef (Citation2019) An Incomplete March: Landmarks on the Path of Resistance (Doha: Arab Center for Policy and Strategic Studies)(in Arabic); Graham Usher (Citation2003), Facing Defeat: The Intifada Two Years On, Journal of Palestine Studies 32(2), pp. 21–40.

66 Zilber & Al-Omari, p. 20.

67 Salim Tamari (Citation2002) Who Rules Palestine? Journal of Palestine Studies, 31(4), pp. 102–113.

68 Toufic Haddad (Citation2016) Palestine Ltd.: Neoliberalism and Nationalism in the Occupied Territory (London: Bloomsbury), p.278.

69 Jeff Halper (Citation2015) War Against the People (London: Pluto Press), p. 149.

70 Eyal Weizman (Citation2007) Hollow Land: Israel's Architecture of Occupation (New York: Verso Books), p.101, pp. 161–166.

71 Elia Zureik (Citation2016) Strategies of Surveillance: The Israeli Gaze, Jerusalem Quarterly 19(2), pp. 12–38.

72 Nigel Parsons & Mark B. Salter (Citation2014) Israeli Biopolitics: Closure, Territorialization, and Governmentality in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, Omran 2(7), pp. 21–42 (in Arabic); Rema Hammami (Citation2019) Destabilizing mastery and the machine: Palestinian agency and gendered embodiment at Israeli military checkpoints, Current Anthropology 60(S19), pp.S87-S97.

73 Stefan Borg (Citation2021) Assembling Israeli Drone Warfare: Loitering Surveillance and Operational Sustainability, Security Dialogue 52(5), pp. 401–417.

74 Anan AbuShanab (2019) ’Connection Interrupted’: A New Report of 7amleh Center Reveals the Digital Occupation of the Palestinian Telecommunications Sector, 7amleh - The Arab Center for the Advancement of Social Media, January 28, 2019. Available at: https://bit.ly/3CVp0ji, accessed November 7, 2021.

75 Nurhan Abujidi (Citation2010) Surveillance and Spatial Flows in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, in Elia Zurek, David Lyon, & Yasmeen Abu-Laban (eds) Surveillance and Control in Israel/Palestine: Population, territory, and power, pp. 337–358 (London: Routledge).

76 Helga Tawil-Souri (Citation2011) Colored Identity: The Politics and Materiality of ID Cards in Palestine/Israel, Social Text 29(2), pp. 67–97.

77 Zureik, Strategies of surveillance, pp. 12–38.

78 Ahmed Sa’di (Citation2021) Israel’s Settler-Colonialism as a Global Security Paradigm, Race & Class 63(2), pp.21-37. Rhys Machold (Citation2015) Mobility and the Model: Policy Mobility and the Becoming of Israeli Homeland Security Dominance, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 47(4), pp. 816–832.

79 Zilber & Al-Omari, State with no Army, pp. 11–12.

80 Ronen Bergman (Citation2018) Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel's Targeted Assassinations (New York: Random House), pp. 427–441.

81 Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2002) Documents Seized during Operation Defensive Shield linking Arafat to Terrorism – 15-Apr-2002, April 15, 2002. Available at: https://bit.ly/3o77D8T, accessed November 7, 2021.

82 Zilber & Al-Omari, State with no Army, p. 53.

83 Alaa Tartir (Citation2015) The evolution and reform of Palestinian security forces 1993–2013, Stability: International Journal of Security and Development 4(1). Available at https://www.stabilityjournal.org/articles/10.5334/sta.gi/, assessed January 20, 2021.

84 Personal interviews with three Palestinians that were interrogated at a Palestinian security division, June 2021.

85 Zilber & Al-Omari, State with no Army, p.53.

86 Michal Weissbrod (Citation2012) ‘Lone Wolf’ Terrorists: The Palestinian Case Study, MA thesis, the Hebrew University, pp. 21–30.

87 On the patterns of protests in Arabic uprising, see: Asef Bayat (Citation2017) Revolution without revolutionaries: Making sense of the Arab Spring (California: Stanford University Press), p. 106.

88 As’ad and Fakhr Eldin, pp. 887–966.

89 Stephen Graham (Citation2010) Laboratories of War: Surveillance and US–Israeli Collaboration in War and Security, in: Zurek, Lyon, & Abu-Laban (eds), pp. 133–152.

90 Rebecca L. Stein (Citation2017) GoPro Occupation: Networked Cameras, Israeli Military Rule, and the Digital Promise, Current Anthropology 58(S15), pp. 56–64.

91 Borg.

92 Buthaina Ishtiwi (2017) Manufacturing Traitors. This is How the Shabak Recruits Palestinians collaborators,” Al-Jazeera, March 9, 2017 (in Arabic). Available at: https://bit.ly/300ujzg, accessed November 7, 2021.

93 “Israel used 'calorie count' to limit Gaza food during blockade, critics claim,” The Guardian, October 17, 2012. Available at: https://bit.ly/3BXrKv4, accessed November 7, 2021.

94 “Data on causalities,” OCHA. Available at: https://bit.ly/3wrpN9m, accessed November 7, 2021.

95 Jasbir K. Puar (Citation2017) The Right to Maim (Durham and London: Duke University Press).

96 Lisa Bhungalia (Citation2010) A Liminal Territory: Gaza, Executive Discretion, and Sanctions Turned Humanitarian, GeoJournal 75(4), pp. 347–357.

97 M. Shaw, M. Coward, E. Weizman, S. Graham, R. Warren & A. Hills (Citation2008) Part II: Urbicide and the Urbanization of Warfare, in Stephen Graham (ed.) Cities, War, and Terrorism: Towards an Urban Geopolitics, pp. 137–246 (Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing).

98 Ahmad Qassem Hussein (Citation2020) How Did Hamas Establish its Army in the Gaza? The Evolution of the Military Action of the Izz al-Din al-Qassam Brigades, Siyasat Arabia 8(4), pp. 45–65 (in Arabic).

References

- Abu Hudaib, K. (1990) The Effect of the Intifada/Uprising in Detaching from the Occupation Authorities, Journal of Palestinian Studies – Arabic Edition, 1(1), pp.256–272.

- Abujidi, N. (2010) Surveillance and spatial flows in the occupied Palestinian territories, in: Zurek, E., Lyon, D. & Abu-Laban, Y. (eds) Surveillance and Control in Israel/Palestine: Population, Territory, and Power, pp. 337–358 (London: Routledge).

- Al-Natoor, M. (2014) Fateh Movement: Between Resistance and Assassination, vol. 2: 1983-2004 (Amman: Dar Al Ahlia for Publishing & Distribution) (in Arabic).

- Aronson, G. (1978) Israel’s Policy of Military Occupation, Journal of Palestine Studies, 7(4), pp. 79–98.

- As’ad, A., & Fakhr Eldin, M. (2021) The Israeli Control over the 1967-Occupied Palestinian and Syrian Lands, in: Fakher Eldin, M. (ed) The General Survey of Israel 2020, pp. 887–966 (Beirut: Institute for Palestine Studies) (in Arabic).

- Awad, H. (2020) Understanding Hamas: Remarks on Three Different and Interrelated Theoretical Approaches, Siyasat Arabia, 8(4), pp. 24–44. (in Arabic).

- Barakat, R. (2018) Writing/Righting Palestine Studies: Settler-Colonialism, Indigenous Sovereignty and Resisting the Ghost(s) of History, Settler Colonial Studies, 8(3), pp. 349–363.

- Baumgarten, H. (2006) From Liberation to the State: History of the Palestinian National Movement, 1948-1988 (Ramallah: Muwatin) (in Arabic).

- Bayat, A. (2017) Revolution Without Revolutionaries: Making Sense of the Arab Spring (California: Stanford University Press).

- Bergman, R. (2018) Rise and Kill First: The Secret History of Israel’s Targeted Assassinations (New York: Random House), pp. 427–441.

- Bhungalia, L. (2010) A Liminal Territory: Gaza, Executive Discretion, and Sanctions Turned Humanitarian, GeoJournal, 75(4), pp. 347–357.