Abstract:

Since 1970, Iran has experienced dramatic environmental, political, and socioeconomic changes and events. All these events have impacted and shaped the urbanized landscape in Iran during the past 50 years. This article provides an overview of those factors influencing the socio-spatial patterns during this half-century of urbanization and highlights the current challenges that confront Iran’s cities.

Iran, because of its socioeconomic conditions (e.g. oil-based economy, rapid population changes, the size and population of the country, and high diversity in terms of ethnicity), historical background and geopolitical position (e.g. sharing a border with one of the superpowers of the world, the Soviet Union/Russia, influencing global energy market due to its vast oil and gas reserves, and its position at the crossroads of major trade routes and energy corridors), has experienced several dramatic events in the past 50 years, including the Islamic Revolution of 1978-79; the eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s, which was one the longest classic wars of the last century; an international economic and political crisis for the past decades over its nuclear program that has been accompanied by unprecedented US economic sanctions; a baby boom during the war with Iraq, followed by a successful family plan that has drastically reduced the size of the population under 20 compared to older age groups; and climate change/severe drought that has led to environmental problems, such as water shortage and air and dust pollution in the largest cities. Crises in neighboring countries and the wider Middle East/Persian Gulf region also have impacted Iran, including Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait in 1989-90; the US invasion and occupation of Iraq in the early 2000s; the Soviet-Russian occupation of Afghanistan in the 1980s; and the rise, fall, and resurgence of the Taliban in Afghanistan in the past 20 years. The three decades of intermittent instability in Afghanistan prompted three waves of mass migration of Afghans into Iran. All these events have shaped the urbanization landscape in Iran and left their footprints on the socio-spatial patterns of urbanization in the country.

In this article, I present an overview of the socio-spatial patterns and challenges that have significantly impacted Iran’s urbanization during the past five decades. Using existing data and literature, I address the following research questions: What spatial patterns of urbanization have emerged in Iran since the late 1970s? And what currently are the main socio-spatial urban challenges in Iran? This article will shed light on urbanization in Iran based on previous research and reports, including available official data, maps, and studies, and present a big picture of the country’s socio-spatial patterns and current urbanization challenges.

Influencing Factors: Geography and Environment

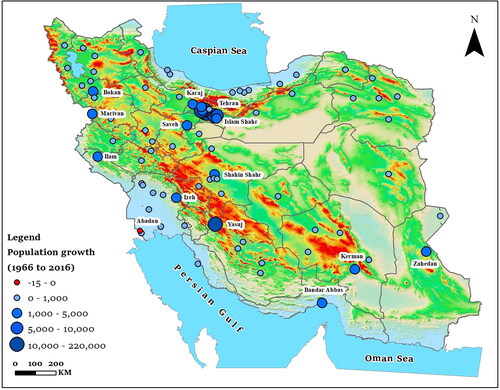

Iran’s geography sets the stage for the country’s uneven geographical distribution of cities. Geographical barriers include two mountain ranges (Alborz and Zagros) and two of the largest deserts in the world (Kavir-e-Lut and Dasht-e-Kavir) have made a large area of the country uninhabitable (See ). In addition, recent severe drought and climate change, overconsumption of groundwater,Footnote1 environmental mismanagementFootnote2 (e.g. shrinking Lake Urmia as a prominent example), and high air and dust pollutionFootnote3 are putting more pressure on populated areas, especially in arid and semi-arid areas. As show, not surprisingly, Tehran (the capital city) and its peripheral cities (e.g. Karaj), one of the largest urban agglomerations in the world, have kept their position and dominance in the urban spatial organization.

Figure 2. Cities with more than 50,000 population in 1966 [Source: compiled by Author based on Statiscal Centre of Iran data].

![Figure 2. Cities with more than 50,000 population in 1966 [Source: compiled by Author based on Statiscal Centre of Iran data].](/cms/asset/d6d19bb2-363c-43c7-8194-8845eb3e6ad9/ccri_a_2256144_f0002_c.jpg)

Demographic Factors and Population Dynamics

The population of Iran was almost 25.8 million in 1966. In the past 50 years, it has increased to 86.5 million. The country’s overall population increased approximately three times from 1966 to 2016, while the urban population experienced a six-fold increase in the same period. Since the first census in 1956, the urbanization growth rate has always been more than the population growth rate; as of 2016, the number of cities (1242 cities) was about five times more than in 1966 (272 cities).Footnote4 In the late 1970s, the country witnessed an urban transition, and the urban population exceeded the rural population for the first time.

One reason for this rapid urbanization rate is the official transformation of villages into cities, especially in the peripheral areas of major metropolitan cities, such as Tehran and Isfahan. In Iran, if the population of a village surpasses a specific number in a census survey, which usually happens every five years, this village officially becomes a city, and its residents are recorded as an urban population. This population threshold was 5,000 before the Islamic revolution, in1983 was 10,000 individuals, in 1986 was 5,000 individuals, and in 2010 was 3,500 individuals. There has been no specific population limitation recently, and the criteria for becoming a city are unclear. As and , and show, the size of many cities, Tehran (as the largest city/macrocephaly in the country’s urban system) and several small or medium-sized cities in the peripheral area of Tehran in 1966, now accommodate large numbers of people. Karaj, on the west and the capital of the new province of Alborz, emerged as a megacity with a population of over 1.6 million. One can see, in 1966, that twelve cities by population–Tehran, Isfahan, Mashhad, Tabriz, Abadan, Shiraz, Ahvaz, Kermanshah, Rasht, Qom, Hamedan, and Urmia—each had a population of more than 100 k, but in 2016, there were 98 cities with this population size. After Teheran, Isfahan shows a similar spatial pattern and change but at a different level regarding the number of cities and their population, including Najafabad, Shahin Shahr, and new towns (e.g. Baharestan). As and show, several cities in the Tehran city-region, Eslam Shahr (Shad Shahr before the Islamic Revolution), the second most populated city in Tehran Province, Karaj, Ghods, Malard, Nasim Shar, Nazarabad, Pakdasht, Shahriar, and Qarchak have experienced skyrocketing population growth. Other cities that have experienced a very high population growth rate include Bandar Abbas (the capital of Hormozagn Province), Yasuj (the capital of Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad Province and a unique example that was a small village with a population of just 931 in 1966 but by 2016 had grown into a city of 134,532 inhabitants), and Zahedan (capital of Sistan and Baluchestan Province).

Table 1. Megacities and big cities’ population growth rate (percent), 1966 to 2016 (* Megacity).

Mass rural-to-urban migration is another crucial factor that has increased Iran’s urbanization rate, and it is the outcome of a series of interwoven economic, environmental, and social factors and changes, such as the transformation of the economy from agriculture to urban factory production and service sectors, capital accumulation in large cities, lack of job opportunities in rural areas, development of suburban industrial districts, and heavy industries (e.g. steel and textile) in these areas which absorbed and attracted white and blue-collar workers, climate change (e.g. water shortage and severe drought) and consequently farming collapse, and higher education development.Footnote5

The sedentarisation of nomads and tribes in the fringe of cities also directly affected the urbanization rate. Most of these tribes are/were living along the Zagros Mountains range, including in Bushehr, Chaharmahal and Bakhtiari, Fars, Ilam, Khuzestan, Kohgiluyeh and Boyer-Ahmad, Kurdistan, and Lorestan provinces, where Arab, Bakhtiari, Kurd, and Lur tribes are/were living and a part of Isfahan province where Bakhtiari are/were living.Footnote6 Over the past half-century, although the total population has been increasing, the number of nomads per total population constantly has declined in successive decennial censuses.Footnote7 In contrast, the urban population of Arabs, Bakhtiari, Kurds, and Lurs shows an increasing pattern in this region of the country (See ).

Political Factors

Policies also play a critical role in intensifying urbanization. City-centric policies, especially after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, have reinforced and promoted existing patterns. Along this line, designing and constructing new towns substantially impacted the pattern of urbanization in Iran. New towns were planned based on economic, ideological, and military goals, especially to provide housing for oil and gas employees before 1979. In 1985, the construction of 28 new towns was included in the work plan of the Ministry of Housing & Urban Development. These new towns and other public housing projects mainly Maskan Mehr or Mehr Housing were built to decentralize such major cities as Tehran and Isfahan, absorb the surplus populations of big cities, provide diverse employment opportunities, and overcome the urban housing problems by offering low-cost affordable housing.Footnote8

Moreover, during the last five decades, Iran’s economy has been at the (semi) periphery of neoliberal economic policies, but after returning the Islamic City Council (Shoray-e-Shahr) to an urban management and decision-making system in 1999 as a replacement for the city council (Anjoman-e-Shahr) in the Pahlavi era, they started following neoliberal policy in urban management. The Islamic City Council elects the mayor of the city and supervises and monitors almost all municipality activities, including the city budget and development plans. The members of the city councils are elected by direct public vote for a 4-year term. Over the past decades, urban managers implemented different versions of neoliberal economic policies under different names and projects, such as Public-Private-Partnership projects and privatization based on Article 44 of the Constitution, to cut city governments’ budgets and support.Footnote9 Therefore, city managers implemented neoliberal-oriented policies to deal with national economic crises due to US sanctions and budget shortages, which increased urban inequalities in favor of specific groups and businesses, especially in megacities.Footnote10

Among Iranian cities, Mashad and Qom, two religious cities, are unique in terms of ideology-driven development. Mashad is the home of the Imam Reza Shrine and attracts millions of pilgrims from Iran and other countries every year. Qom is often considered the religious capital of the country. It is also home to Imam Reza’s sister shrine and the renowned Qom Seminary, one of the Shia world’s most important scholarship and education centers. As Iran is a predominantly Shia Muslim country, these two cities’ religious authority and influence hold significant weight within the country’s political landscape.Footnote11 The government often seeks to maintain a favorable relationship with the religious establishments in Mashad and Qom. Both cities show very high and similar growth rates (), which may reflect the ideological and political perspective of the government toward urban development. Considering these two cities' environmental and ecological limitations, their population growth and physical expansion have exceeded their ecological capacity.Footnote12 At the urban level, the government tries to produce its own urban public space and symbols,Footnote13 for example, replacing Azadi Tower with Milad Tower as the symbol of TehranFootnote14 and developing religious spaces (e.g. the number of mosques).

Geopolitical Factors

During the last 50 years, the Middle East has experienced several dramatic political tensions and wars. After 1978, the fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power in Iran, along with eight years of war following Iraq’s invasion into Iran, had significant effects on the functionality, governing systems, and socio-spatial patterns of cities and their landscapes. This war caused a mass movement of the population from the western part of the country to other parts, especially the central area and megacities such as Tehran and Isfahan, which led to population growth and urban sprawl in megacities.Footnote15 For example, Abadan in Khuzestan province was a prosperous city in 1980, where the world’s largest oil refinery was based. Iraq’s September 1980 invasion into Iran destroyed the refinery and had a negative impact on population growth, with the city losing its population during the eight years of war. The city’s population was 273 thousand (k) in 1966, 294k in 1976, 0 in 1986, only 855 in 1991, but 206k in 1996, 220k in 2006, and 231k in 2016. Even three decades after the war, Abadan still has fewer inhabitants than in 1980 before the war ().

In Iran’s eastern neighbor, Afghanistan, the 1978 Saur Revolution and the rise, fall, and resurgence of the Taliban in Afghanistan led to Iran becoming one of the largest refugee-hosting countries in the world. Also, the two Persian Gulf Wars (1990-91 and 2003-2011) and the emergence of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) increased the immigration from Iraq to Iran’s megacities. Approximately 95% of these refugees are living in five cities: Esfahan, Mashad, Qom, Tehran, and Yazd. Simply put, urbanization patterns have been influenced by population pressure and dynamics, migration from rural to urban areas,Footnote16 the gas and petroleum industry, political perspective of the government toward development, new urban lifestyles of formerly migrating tribes, international immigration, mainly from Afghanistan and Iraq,Footnote17 and the Iraq-Iran war.Footnote18 From 1986 to 1996, Iran witnessed a significant change in the number of cities with up to 1 million population, but the pressure was on megacities, especially Bandar Abbas, Isfahan, Karaj, Mashad, Qom, Tehran, and Zahedan.

Challenges

The aim of this article is not to refute the positive impacts and outcomes of urbanization on the economy, people and quality of life but rather to highlight the current urban challenges facing cities.Footnote19 An overview of these challenges reveals that many of them are also global challenges, which are the consequences of the tragedy of the commons in the world, but they can provide insights into the future for planners and researchers.Footnote20

One of the main drivers of urbanization is the economy. Iran’s economy highly depends on the gas and petroleum industries. Therefore, the oil production rate has been one of the most crucial factors in all socio-spatial processes and patterns, especially urbanization, including the development of the oil, gas, and petrochemical industries in Bushehr, Fars, Hormozgan, Ilam, Kermanshah, and especially Khuzestan provinces.Footnote21 Although the largest cities in these provinces act as economic engines, they also impede even-development by absorbing a large share of capital and business activities from peripheral cities.Footnote22 The list of urban cultural, economic, and socio-spatial challenges probably is endless, but they include crime, informal settlements and slums, macrocephaly in the urban system, mass immigration, new urban lifestyles, social change, housing shortages, ever-increasing house prices, spatial inequality and segregation, and suburbanization of poverty.Footnote23 Among these challenges, housing and the real estate market combined with the new individualistic lifestyle and demographic changes may trigger other socioeconomic challenges, e.g. the relationships between urban sprawl,Footnote24 housing, and divorce.Footnote25 The recent official report shows that the percentage of urban households without access to affordable housing amounted to 45% in the country and 79% in Tehran. The average housing price in Tehran has increased by 950% from 2019 to 2023.Footnote26 The government and urban management, municipalities, and city councils need to pay special attention to these areas.

Population growth and quantity and quality dualism have been at the center of debates in Iran since the Islamic Revolution. Different presidential administrations have supported various family planning policies. The government promoted population growth during the Iraq-Iran war. After this period, Iran ran one of the world’s most successful population control programs.Footnote27 Recently, the government announced that population growth is the main focus of all social and development plans. Now, some politicians in the country see population growth and quantity as a political challenge and a way to destabilize the government by Western countries. These questions are open because some researchers and experts have different ideas, but any implemented policy will impact socio-spatial patterns and future challenges of urbanization.

Moreover, environmental challenges grow as cities expand in size and number, especially in megacities. Transportation, industrial activities, and energy demand have increased in megacities due to population growth and unsustainable urban development, leading to increasing levels of air pollution, earthquake damage, floods, urban sprawl, and worn-out urban infrastructure.Footnote28 All these challenges subject city residents to health risks associated with harmful pollutants and impose high economic, health, and social costs on the citizens. Urbanization and climate change are deeply interwoven. While cities are affected by the global climate crisis, they contribute to climate change through various activities and processes that release greenhouse gases and affect the environment.Footnote29 Climate change can significantly affect various aspects of city life and patterns and processes of urbanization and exacerbate existing challenges, including water scarcity and drought, extreme heat waves, urban heat island effect, natural hazards, extreme weather events, and other environmental threats (i.e. flood and drought).Footnote30 Climate change, directly and indirectly, will lead to mass migration and more population pressure in megacities with better environmental and ecological conditions. Climate-induced environmental changes have inevitable cultural, health, political, and socioeconomic consequences for citizens. For example, water scarcity can push rural populations to migrate to cities in search of better opportunities in the job market, but many of these cities are prone to natural hazards, including earthquakes, landslides, and floods, especially along the Alborz and Zagros Mountain Ranges. This influx of people puts additional pressure on urban infrastructure,Footnote31 housing, employment opportunities, and services, potentially leading to an increase in informal settlements and urban poverty.Footnote32 The studies on internal migration in Iran show that the flow is toward areas currently suffering from water shortage, especially in the central areas (e.g. Isfahan and Yazd)Footnote33 and south (Kerman and Zahedan).Footnote34 This means more water demand and consumption, leading to a severe water shortage and tension inside the central areas. Some environmental and ecological changes and problems, such as drought, flood, and dust, should be seen at the Middle East scale. For example, Iran has water conflicts with Afghanistan, Iraq, and Turkey; the sources of dust storms in Iran are not only deserts in the country (e.g. Dasht-e-Kavir and Dasht-e-Lut), but also deserts in Iraq, Jordan, Syria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Turkmenistan.Footnote35 Some Middle Eastern countries have similar environmental issues, especially the degradation of environmental conditions.Footnote36 Geographical and environmental challenges often stem from factors and processes that disregard political borders; therefore, environmental plans to mitigate climate change impacts need to be designed for the wider context in this region, but the current geopolitical conditions in the Middle East make it very challenging if there is no political and collective will.

In the last 50 years, political and social unrest and upheavals have increased. The 1979 Islamic Revolution, which led to a major regime change in the country,Footnote37 was motivated, at least partially, by discontent over urban conditions in the second Pahlavi era. The US hostages’ crisis from November 1979 to January 1981 set off a break in Iran-US diplomatic relations that has continued for 44 years. Although there was a brief relaxation of tensions when the US and Iran mutually agreed in 2015 to a procedure for inspecting Iran’s nuclear facilities (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action, or JCPOA), the US withdrew from this agreement in 2018 and re-imposed economic sanctions on Iran. Since 1980, Western countries, especially the US, have imposed numerous economic sanctions on Iran, which have impacted the performance of the country’s economic sectors adversely. In addition, the Iranian government’s attitude toward centralizing power and capital has played an important role in concentrating economic activities and population in large cities. All these challenges, including the concentration of development, industrial site selection, social unrest and protest, and neoliberal economic policies,Footnote38 reveal the underlying tension in the society and governing system of the country.Footnote39 For example, five decades after the initiation of urban development plans in Iran, these plans still face various challenges to their full and successful implementation. Furthermore, top-down urban planning often has contributed to exacerbating diverse urban issues and problems, including people displacement and gentrification, ecological pressures, economic and/or ethnic segregation, poverty and health conditions, social tensions, and urban sprawl.Footnote40 The country has witnessed overemphasizing engineering and technocratic solutions, such as water transfer (e.g. Khuzestan to Isfahan and Isfahan to Yazd) and big dam projects, to overcome some of these challenges, and their destructive consequences on the ecosystem, forced people displacement, commodification and commercialization of water, and criminalization of environmental and social protests, have complicated the situation and increased social and political tensions between cities and citizens.Footnote41 This engineering and technological approach in (urban) planning and management systems needs to be revised; otherwise, it might exacerbate existing challenges and problems.Footnote42

Another challenge is using and dealing with technologies, especially emerging ones, such as urban artificial intelligence (AI) and smart city projects and initiatives. While technology can provide partial solutions to some economic, environmental, and socio-spatial problems, it can cause new challenges because technology usually reinforces existing socio-spatial structures and patterns and produces new forms of inequalities (e.g. digital divide).Footnote43 The digital and data revolution has had cultural, economic, political , and social changes in cities. In this digitalized world, where people are surrounded by the Internet of Things (IoT) and increasing smartphone usage, access to (stable and reliable) Internet is a basic need and right. The Internet connection is necessary for the education system, different urban management sectors, online jobs, communication through platforms, daily activities (e.g. online banking), etc.Footnote44 Also, digital technologies can play a critical role in the country’s social-spatial patterns and challenges of urbanization in different ways due to their impacts on influencing factors such as internal and international immigration. Over the digitalization process, some aspects of socio-spatial inequality, such as the digital divide, can boost people’s immigration from rural to urban areas and increase existing socio-spatial inequalities within urban areas. For the country, which has been suffering from brain drain over the recent decades, these emerging technological challenges can cause more difficulties at both national and international levels with footprints on the urbanization landscape and patterns.

Other outcomes, such as social change, are not within the scope of this article. Nevertheless, previous studies indicated that recent patterns and trends in urbanization have various effects on gender roles and families as they change the roles of women and men.Footnote45 Urbanization has facilitated social change by increasing women’s access to higher education, labor market, and participation in political arenas. Also, higher education acted as one of the drivers of immigration and urbanization over the past decades. Universities, especially in megacities, have absorbed a huge number of youths into cities. Urbanization has impacted all aspects of life in Iran; this topic needs more attention and research to deal with mounting challenges, such as bridging social capital, increasing brain drain rate, housing shortages, identity crises, inadequate urban services, growing informal economic activities, marginalization of people and communities, rising urban poverty and unsustainable urban development, especially in metropolises.

One reason for the existing gap in the literature on various aspects of urbanization in Iran is inadequate data availability and accessibility compared with developed countries. The government can resolve this issue by providing updated and open-access data and following the objectives of open science and open data. Open science in general, and open data in particular, make researchers more responsive to social challenges.Footnote46 Another reason is the lack of academic freedom, especially in social research areas, which has made researchers more conservative in disclosing their academic results and communicating their findings to policy designers and the public. Consequently, the social challenges can be exacerbated in the long term.Footnote47 Obviously, all macro and micro factors and drivers are interwoven, and more research on different scales will offer new insight into the literature and enable both officials and scholars to learn from the past patterns and trends for future environmental and socioeconomic planning and urban studies in Iran. Moreover, urbanization in Iran needs to be studied in the Middle East context. For this purpose, new emerging (big) data (e.g. night and day mode satellite images) and advanced spatial methods (e.g. data integration, spatial econometrics, and computational techniques) can provide more contextual, environmental, and geographical information to gain a better understanding of the underlying political and socioeconomic processes and environmental spillover effects of urbanization in the country. Qualitative data and methods (e.g. interviews and historical documents) can provide more information in this area and contextualize the quantitative outputs, such as maps.

Conclusion

This high-level overview of the spatial patterns of urbanization and their influencing factors in Iran over the last 50 years highlighted the current challenges of living in cities, especially megacities. These challenges cannot be addressed without considering all the cultural, environmental, geographical, political, and socioeconomic limitations and without attention to global and macro factors and drivers of changes in governmentality and spatial planning systems. One can predict that the country’s population will be more urban due to current trends of population dynamics and city-centric and top-down planning approaches. Moreover, on the one hand, Iran, as a country that has not been standing on the core of neoliberal economic policies, started implementing them by providing private urban facilities and services, such as schooling, after the Iraq-Iran war and under the banner of a privatization policy. On the other hand, external drivers such as two rounds of severe US economic sanctions, an unstable oil market, and mass migration from neighboring countries, mainly Afghanistan, make urban life much more costly and stressful for citizens. The integration of these immigrants into the host society needs more attention. In addition, Iran experienced a mass displacement of people from rural areas toward big cities and megacities where there was no plan for accommodating these newcomers, who usually experience cultural and social tensions with the long-settled urban residents. Climate change and environmental problems sharpen pre-existing vulnerabilities and aggravate above mentioned challenges. Therefore, it is likely that cities, especially megacities, and the suburbanization of poverty in the country will lead to more challenges and pressures that can burden citizens, government, and public organizations with huge costs, such as public health system, and we may witness the expansion of informal settlements and more social unrest and tensions in megacities and medium-sized cities. Tehran acts as an engine of capital relocation in the urban system, will likely retain its current position and remain the dominant megacity in the coming decades despite its ever-increasing environmental, political, and socioeconomic challenges. Also, other megacities likely will continue to draw more population. Considering similar environmental and population challenges at the Middle East scale, it is time to call for action and political and collective will to implement an integrated regional environmental policy. Universities, research bodies, researchers, and regional environmental and urban observatories and monitoring systems can play a critical role through academic collaborations, such as sharing data and communicating the findings to the public and policy designers.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Mahmoud Ghazi-Tabataei for encouraging me to write this article and Dr. Shahin Mohammadi for his help with maps.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 Mostafa Khorsandi, Saeid Homayouni & Pieter Van Oel (Citation2022) The Edge of the Petri Dish for a Nation: Water Resources Carrying Capacity Assessment for Iran, Science of the Total Environment, 817, pp. 1–12.

2 Sepehr Ghazinoory, Mohammad Khosravi & Shohreh Nasri (Citation2021) A Systems-Based Approach to Analyze Environmental Issues: Problem-Oriented Innovation System for Water Scarcity Problem in Iran, Journal of Environment and Development, 30(3), pp. 291–316.

3 Ashkan Jahandari (Citation2020) Pollution Status and Human Health Risk Assessments of Selected Heavy Metals in Urban Dust of 16 Cities in Iran, Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 27, pp. 23094–23107; Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi, Shahin Mohammadi, Mohsen Saber, Saeid Amini & Gavin McArdle (Citation2022) Spatiotemporal Analysis of NO2 Production Using TROPOMI Time-Series Images and Google Earth Engine in a Middle Eastern Country, Remote Sensing, 14(7), pp. 1–18.

4 Seyed Mehdi Mousakazemi (Citation2013) Spatial Distribution of Population and Hierarchical System of Cities (Case Study: Iran 1956–2011), Physical Social Planning, 1(3), pp. 113–124.

5 Hadi Salehi Esfahani & Hashem Pesaran (Citation2009) The Iranian Economy in the Twentieth Century: A Global Perspective, Iranian Studies, 42(2), pp. 177–211; Noureddin Farash, Hamidreza Rabiei Dastjerdi, Mahmoud Ghazi Tabatabaie & Rasoul Sadeghi. (Citation2021) Education and Spatial Segregation in Tehran Metropolis, Community Development, 13(1), pp. 37–65.

6 Mostafa Azkia (Citation1997) Modernization Theory in a Tribal‐peasant Society of Southern Iran, Critique: Journal for Critical Studies of the Middle East, 6(10), pp. 77–90.

7 Rahimberdi Annamoradnejad & Sedigheh Lotfi (Citation2010) Demographic Changes of Nomadic Communities in Iran (1956–2008), Asian Population Studies, 6(3), pp. 335–345.

8 Safar Ghaedrahmati & Moslem Zarghamfard (2020) Housing Policy and Demographic Changes: The Case of Iran, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 14(1), pp. 1–13.

9 Rana Habibi, Mohsen Habibi & Elmira Jamei (Citation2021) Space Production in Times of Neoliberalism, in: Simona Azzali, Silvia Mazzetto & Attilio Petruccioli (eds), Urban Challenges in the Globalizing Middle East: Social Value of Public Spaces (Springer Nature Open-access Books), pp. 11–22.

10 Kayhan Valadbaygi (Citation2021) Hybrid neoliberalism: Capitalist development in contemporary Iran, New Political Economy, 26(3), pp. 313–327.

11 Eric Hooglund & William Royce (Citation1985) The Shi’i Clergy of Iran and the Conception of an Islamic State, State, Culture, and Society, 1(3), pp. 102–117.

12 Hassan Mosammam Mohammadian, Jamileh Tavakoli Nia, Hadi Khani, Asghar Teymouri & Mohammad Kazemi (Citation2017) Monitoring Land Use Change and Measuring Urban Sprawl Based on its Spatial Forms: The Case of Qom City, The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 20(1), pp. 103–116; Ghazaleh Rabbani, Sirous Shafaqi & Mohammad Rahim Rahnama (Citation2018) Urban Sprawl Modeling Using Statistical Approach in Mashhad, Northeastern Iran, Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 4, pp. 141–149.

13 Kaveh Ehsani (Citation1999) Municipal Matters: The Urbanization of Consciousness and Political Change in Tehran, Middle East Report, 212, pp. 22–27.

14 Susan Ghaffaryan & Hamidreza Rabiei Dastjerdi (Citation2013) Modernization Alignment of Tehran Urban Symbols with Tehran Citizens Ways of Conceptualizing. In: NUL New Urban Language, pp. 1–7.

15 Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi, Saeid Amini, Gavin McArdle & Saeid Homayoun (Citation2022) City-Region or City? That Is the Question: Modelling Sprawl in Isfahan Using Geospatial Data and Technology, GeoJournal, pp. 1–21.

16 Ali Asghar Pilehvar (Citation2020) Urban Unsustainability Engineering in Metropolises of Iran, Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering, 44(3), pp. 775–785.

17 Rasoul Sadeghi, Mohammad Jalal Abbasi-Shavazi & Saeedeh Shahbazin (Citation2020) Internal Migration in Iran, in: Martin Bell, Aude Bernard, Elin Charles-Edwards & Yu Zhu (eds.), Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia, (Springer International Publishing), pp. 295–317; Eric Hooglund (Citation1991) The Other Face of War, Middle East Report, pp. 3–12.

18 Hadi Salehi Esfahani & Hashem Pesaran (2009) The Iranian Economy in the Twentieth Century: A Global Perspective. Iranian Studies, 42(2), pp. 177–211.

19 Edward Glaeser (Citation2011) Triumph of the City: How Urban Spaces Make Us Human (London: Pan Macmillan).

20 David Feeny, Fikret Berkes, Bonnie J. McCay & James M. Acheson (Citation1990) The Tragedy of the Commons: Twenty-Two Years Later, Human Ecology, 18(1), pp. 1–19.

21 Kaveh Ehsani (Citation2003) Social Engineering and the Contradictions of Modernization in Khuzestan’s Company Towns: A Look at Abadan and Masjed-Soleyman, International Review of Social History, 48(3), pp. 361–399.

22 Ali Madanipour (Citation1998) Tehran: The Making of a Metropolis (Sussex: John Wiley); Hooshang Amirahmadi & Ali Kiafar (Citation2017) The Transformation of Tehran from a Garrison Town to a Primate City: A Tale of Rapid Growth and Uneven Development, in: Hooshang Amirahmadi (ed) Urban Development in the Muslim World, pp. 109–136 (New York: Routledge).

23 Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi & Maryam Kazemi (Citation2016) Tehran: Old and Emerging Spatial Divides, in: Fatemeh Farnaz Arefian & Seyed Hossein Iradj Moeini (eds) Urban Change in Iran, pp. 171–186 (Cham: Springer International Publishing); Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi & Stephen A. Matthews (Citation2021) Who Gets What, Where, and How Much? Composite Index of Spatial Inequality for Small Areas in Tehran, Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13(1), pp. 191–205; Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi, Stephen A. Matthews & Ali Ardalan (Citation2018) Measuring Spatial Accessibility to Urban Facilities and Services in Tehran, Spatial Demography, 6(1), pp. 17–34.

24 Bagher Bagheri & Ali Soltani (Citation2023) The Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Urban Growth and Population in Metropolitan Regions of Iran, Habitat International, 136, pp. 1–13.

25 Mohammad Reza Farzanegan & Hassan Fereidouni Gholipour (Citation2016) Divorce and the Cost of Housing: Evidence from Iran, Review of Economics of the Household, 14, pp. 1029–1054.

26 Financial Tribune (June Citation2023). Tehran Home Prices Increase Astronomically Within 5 Yrs. Available online at https://financialtribune.com/node/118506, accessed 28 July 2023.

27 Akbar Aghajanian (Citation1991) Population Change in Iran, 1966–86: A Stalled Demographic Transition?, Population & Development Review, 17(4), pp. 703–715.

28 James Jackson (Citation2006) Fatal Attraction: Living with Earthquakes, the Growth of Villages into Megacities, and Earthquake Vulnerability in the Modern World, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 364(1845), pp. 1911–1925; Parviz Zeaiean, Hamid Reza Rabiei & Abbas Alimohamadi. (Citation2005) Detection of Land Use/Cover Changes of Isfahan by Agricultural Lands Around Urban Area Using Remote Sensing and GIS Technologies, The Journal of Spatial Planning, 9(4), pp. 41–54; Morteza Shabani, Shadman Darvishi, Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi, Seyed Ali Alavi, Tanupriya Choudhury & Karim Solaimani (Citation2022) An Integrated Approach for Simulation and Prediction of Land Use and Land Cover Changes and Urban Growth (Case Study: Sanandaj City in Iran)., Journal of the Geographical Institute’Jovan Cvijić’SASA, 72(3), pp. 273–289.

29 Sarah Chapman, James EM Watson, Alvaro Salazar, Marcus Thatcher & Clive A. McAlpine (Citation2017) The Impact of Urbanization and Climate Change on Urban Temperatures: A Systematic Review, Landscape Ecology, 32(10), pp. 1921–1935.

30 Karim C. Abbaspour, Monireh Faramarzi, Samaneh Seyed Ghasemi & Hong Yang (Citation2009) Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources in Iran, Water Resources Research, 45(10). Available at https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2008WR007615, accessed 29 July 2023.

31 Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi & Stephen A. Matthews (Citation2018) Isfahan City Hospitals, Iran, in the Context of Urban Growth: New Developments and Future Challenges, Health Information Management, 15(1), pp. 1–2.

32 Oli Brown (Citation2008) Migration and Climate Change. IOM Migration Research Series (UN). Available online at https://www.un-ilibrary.org/content/books/9789213630235, accessed July 29, 2023.

33 Fatemeh Tanhaa, Hamid Reza Rabiei-Dastjerdi & Hossein Mahmoudian (Citation2023) The Impact of Internal Migration on the Sex Ratio of Iranian Counties in the 2011 to 2016 Period; Application of Geographically Weighted Regression, Journal of Population Association of Iran, pp. 207–240.

34 Esmaeil Khazaei, Rae Mackay & James W. Warner (Citation2004) The Effects of Urbanization on Groundwater Quantity and Quality in the Zahedan Aquifer, Southeast Iran, Water International, 29(2), pp. 178–188.

35 Alireza Rashki, Nick J. Middleton & Andrew S. Goudie (Citation2021) Dust Storms in Iran – Distribution, Causes, Frequencies and Impacts, Aeolian Research, 48, pp. 1–17.

36 Shahin Mohammadi, Mohsen Saber, Saeid Amini, Mir Abolfazl Mostafavi, Gavin McArdle & Hamidreza Rabiei-Dastjerdi. (Citation2022) Environmental Conditions in Middle Eastern Megacities: A Comparative Spatiotemporal Analysis Using Remote Sensing Time Series, Remote Sensing, 14(22), pp. 1–21.

37 Stephen C. Poulson (Citation2005) Social Movements in Twentieth-Century Iran: Culture, Ideology, and Mobilizing Frameworks (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books).

38 Farzaneh Haghighi (Citation2022) Street Protest and Its Representations: Urban Dissidence in Iran, in: N. Bobic & F. Haghighi (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Architecture, Urban Space and Politics, Volume I, pp. 361–378 (Routledge).

39 Amirhossein Teimouri (Citation2022) The Mahdavī Society: The Rise of Millennialism in Iran as the Cultural Outcome of Social Movements (2000–2016), Middle East Critique, 31(2), pp. 125–145.

40 Rahmatoallah Farhoodi, Mehdi Gharakhlou-N, Mostafa Ghadami & Musa Panahandeh Khah (Citation2009) A Critique of the Prevailing Comprehensive Urban Planning Paradigm in Iran: The Need for Strategic Planning, Planning Theory, 8(4), pp. 335–361.

41 Farhad Yazdandoost (Citation2016) Dams, Drought and Water Shortage in Today’s Iran. Iranian Studies, 49(6), pp.1017–1028.; Elham Hoominfar (Citation2023) The Marketization of Water: Environmental Movements’ Narratives and Common Experiences on Water Transfer Projects in Colorado and Western Iran, Water International, 48(4), pp. 500–526.

42 Kaveh Madani (Citation2014) Water Management in Iran: What Is Causing the Looming Crisis?, Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 4, pp. 315–328.

43 Sybille Bauriedl & Anke Strüver (Citation2020) Platform Urbanism: Technocapitalist Production of Private and Public Spaces, Urban Planning, 5(4), pp. 267–276.

44 Rob Kitchin (Citation2021) The Data Revolution: A Critical Analysis of Big Data, Open Data and Data Infrastructures (London: SAGE Publications); Rob Kitchin, Tracey P. Lauriault & Gavin McArdle (Citation2018) Data and the City (London: Routledge).

45 Roksana Bahramitash & Eric Hooglund (Citation2011) Gender in Contemporary Iran: Pushing the Boundaries (London: Taylor & Francis).

46 Erin C McKiernan, Philip E. Bourne, C. Titus Brown, Stuart Buck, Amye Kenall, Jennifer Lin, Damon McDougall, Brian A Nosek, Karthik Ram, Courtney K. Soderberg, Jeffrey R Spies, Kaitlin Thaney, Andrew Updegrove, Kara H. Woo & Tal Yarkoni (Citation2016) How Open Science Helps Researchers Succeed, eLife, 5, Available online at https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.16800, accessed 21 July 2023.; Kitchin, The Data Revolution: A Critical Analysis of Big Data, Open Data and Data Infrastructures.

47 Henry Reichman (Citation2019) The Future of Academic Freedom (Baltimore, MD: JHU Press).

References

- Abbaspour, K. C., Faramarzi, M., Ghasemi, S. S., & Yang, H. (2009) Assessing the Impact of Climate Change on Water Resources in Iran, Water Resources Research, 45(10), pp. 1–6. Available at: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1029/2008WR007615, accessed 29 July 2023.

- Aghajanian, A. (1991) Population Change in Iran, 1966-86: A Stalled Demographic Transition? Population and Development Review, 17(4), pp. 703–715.

- Amirahmadi, H., & Kiafar, A. (2017) The Transformation of Tehran from a Garrison Town to a Primate City: A Tale of Rapid Growth and Uneven Development, in: Amirahmadi, H. (ed) Urban Development in the Muslim World, pp. 109–136 (New York: Routledge).

- Annamoradnejad, R., & Lotfi, S. (2010) Demographic Changes of Nomadic Communities in Iran (1956–2008), Asian Population Studies, 6(3), pp. 335–345.

- Azkia, M. (1997) Modernization Theory in a Tribal‐Peasant Society of Southern Iran, Critique: Critical Middle Eastern Studies, 6(10), pp. 77–90.

- Bagheri, B., & Soltani, A. (2023) The Spatio-Temporal Dynamics of Urban Growth and Population in Metropolitan Regions of Iran, Habitat International, 136, pp. 102797.

- Bahramitash, R., & Hooglund, E. (2011) Gender in Contemporary Iran: Pushing the Boundaries (London: Taylor & Francis).

- Bauriedl, S., & Strüver, A. (2020) Platform Urbanism: Technocapitalist Production of Private and Public Spaces, Urban Planning, 5(4), pp. 267–276.

- Brown, O. (2008) Migration and Climate Change. IOM Migration Research Series (UN). Available at: https://www.unilibrary.org/content/books/9789213630235, accessed 29 July 2023.

- Chapman, S., Watson, J. E., Salazar, A., Thatcher, M., & McAlpine, C. A. (2017) The Impact of Urbanization and Climate Change on Urban Temperatures: A Systematic Review, Landscape Ecology, 32(10), pp. 1921–1935.

- Ehsani, K. (1999) Municipal Matters: The Urbanization of Consciousness and Political Change in Tehran, Middle East Report, (212), pp. 22–27, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3012909.

- Ehsani, K. (2003) Social Engineering and the Contradictions of Modernization in Khuzestan’s Company Towns: A Look at Abadan and Masjed-Soleyman, International Review of Social History, 48(3), pp. 361–399.

- Esfahani, H. S., & Pesaran, M. H. (2009) The Iranian Economy in the Twentieth Century: A Global Perspective, Iranian Studies, 42(2), pp. 177–211.

- Farash, N., Rabiei Dastjerdi, H., Ghazi Tabatabaie, M., & Sadeghi, R. (2021) Education and Spatial Segregation in Tehran Metropolis, Community Development, 13(1), pp. 37–65.

- Farhoodi, R., Gharakhlou-N, M., Ghadami, M., & Khah, M. P. (2009) A Critique of the Prevailing Comprehensive Urban Planning Paradigm in Iran: The Need for Strategic Planning, Planning Theory, 8(4), pp. 335–361.

- Farzanegan, M. R., & Gholipour, H. F. (2016) Divorce and the Cost of Housing: Evidence from Iran, Review of Economics of the Household, 14(4), pp. 1029–1054.

- Feeny, D., Berkes, F., McCay, B. J., & Acheson, J. M. (1990) The Tragedy of the Commons: Twenty-Two Years Later, Human Ecology, 18(1), pp. 1–19.

- Financial Tribune (2023) Tehran Home Prices Increase Astronomically Within 5 Yrs, June. Available at https://financialtribune.com/node/118506, accessed 28 July 2023.

- Ghaedrahmati, S., & Zarghamfard, M. (2021) Housing Policy and Demographic Changes: The Case of Iran, International Journal of Housing Markets and Analysis, 14(1), pp. 1–13.

- Ghaffaryan, S., & Rabiei Dastjerdi, H. G. (2013) Modernization Alignment of Tehran Urban Symbols with Tehran Citizens Ways of Conceptualizing, in: NUL New Urban Language, pp. 1–7.

- Ghazinoory, S., Khosravi, M., & Nasri, S. (2021) A Systems-Based Approach to Analyze Environmental Issues: Problem-Oriented Innovation System for Water Scarcity Problem in Iran, The Journal of Environment & Development, 30(3), pp. 291–316.

- Glaeser, E. (2011) Triumph of the City: How Urban Spaces Make Us Human (London: Pan Macmillan).

- Habibi, R., Habibi, S. M., & Jamei, E. (2021) Space Production in Times of Neoliberalism, in: Azzali, S., Mazzetto, S. & Petruccioli, A. (eds) Urban Challenges in the Globalizing Middle-East: Social Value of Public Spaces, pp. 11–22 (Springer Nature), https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-69795-2#about-this-book.

- Haghighi, F. (2022) Street Protest and Its Representations: Urban Dissidence in Iran, in: Bobic, N. & Haghighi, F. (eds) The Routledge Handbook of Architecture, Urban Space and Politics, Vol. I, pp. 361–378 (New York: Routledge).

- Hooglund, E. (1991) The Other Face of War, Middle East Report, (171), pp. 3–12, https://merip.org/1991/07/the-other-face-of-war/.

- Hooglund, E., & Royce, W. (1985) The Shi’i Clergy of Iran and the Conception of an Islamic State, State, Culture, and Society, 1(3), pp. 102–117.

- Hoominfar, E. (2023) The Marketization of Water: Environmental Movements’ Narratives and Common Experiences on Water Transfer Projects in Colorado and Western Iran, Water International, 48(4), pp. 500–526.

- Jackson, J. (2006) Fatal Attraction: Living with Earthquakes, the Growth of Villages into Megacities, and Earthquake Vulnerability in the Modern World, Philosophical Transactions. Series A, Mathematical, Physical, and Engineering Sciences, 364(1845), pp. 1911–1925.

- Jahandari, A. (2020) Pollution Status and Human Health Risk Assessments of Selected Heavy Metals in Urban Dust of 16 Cities in Iran, Environmental Science and Pollution Research International, 27(18), pp. 23094–23107.

- Khazaei, E., Mackay, R., & Warner, J. W. (2004) The Effects of Urbanization on Groundwater Quantity and Quality in the Zahedan Aquifer, Southeast Iran, Water International, 29(2), pp. 178–188.

- Khorsandi, M., Homayouni, S., & van Oel, P. (2022) The Edge of the Petri Dish for a Nation: Water Resources Carrying Capacity Assessment for Iran, The Science of the Total Environment, 817, pp. 153038.

- Kitchin, R. (2021) The Data Revolution: A Critical Analysis of Big Data, Open Data and Data Infrastructures (London: SAGE Publications).

- Kitchin, R., Lauriault, T. P., & McArdle, G. (2018) Data and the City (London: Routledge).

- Madani, K. (2014) Water Management in Iran: What is Causing the Looming Crisis? Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences, 4(4), pp. 315–328.

- Madanipour, A. (1998) Tehran: The Making of a Metropolis (Sussex: John Wiley).

- Manouchehri, G. R., & Mahmoodian, S. A. (2002) Environmental Impacts of Dams Constructed in Iran, International Journal of Water Resources Development, 18(1), pp. 179–182.

- McKiernan, E. C., Bourne, P. E., Brown, C. T., Buck, S., Kenall, A., Lin, J., McDougall, D., Nosek, B. A., Ram, K., Soderberg, C. K., Spies, J. R., Thaney, K., Updegrove, A., Woo, K. H., & Yarkoni, T. (2016) How Open Science Helps Researchers Succeed, eLife, 5, July. Available at https://elifesciences.org/articles/16800, accessed 21 July 2023.

- Mohammadi, S., Saber, M., Amini, S., Mostafavi, M. A., McArdle, G., & Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H. (2022) Environmental Conditions in Middle Eastern Megacities: A Comparative Spatiotemporal Analysis Using Remote Sensing Time Series, Remote Sensing, 14(22), pp. 5834.

- Mosammam, H. M., Nia, J. T., Khani, H., Teymouri, A., & Kazemi, M. (2017) Monitoring Land Use Change and Measuring Urban Sprawl Based on Its Spatial Forms: The Case of Qom City, The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 20(1), pp. 103–116.

- Mousakazemi, S. M. (2013) Spatial Distribution of Population and Hierarchical System of Cities (Case Study: Iran 1956-2011), Physical Social Planning, 1(3), pp. 113–124.

- Pilehvar, A. A. (2020) Urban Unsustainability Engineering in Metropolises of Iran, Iranian Journal of Science and Technology, Transactions of Civil Engineering, 44(3), pp. 775–785.

- Poulson, S. C. (2005) Social Movements in Twentieth-Century Iran: Culture, Ideology, and Mobilizing Frameworks (Lanham, MD: Lexington Books).

- Rabbani, G., Shafaqi, S., & Rahnama, M. R. (2018) Urban Sprawl Modeling Using Statistical Approach in Mashhad, Northeastern Iran, Modeling Earth Systems and Environment, 4(1), pp. 141–149.

- Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., & Kazemi, M. (2016) Tehran: Old and Emerging Spatial Divides. In: Arefian, F. F. & Moeini, S. H. I. (eds) Urban Change in Iran, pp. 171–186 (Cham: Springer International Publishing).

- Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., & Matthews, S. A. (2018) Isfahan City Hospitals, Iran, in the Context of Urban Growth: New Developments and Future Challenges, Health Information Management, 15(1), pp. 1–2.

- Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., & Matthews, S. A. (2021) Who Gets What, Where, and How Much? Composite Index of Spatial Inequality for Small Areas in Tehran, Regional Science Policy & Practice, 13(1), pp. 191–205.

- Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., Amini, S., McArdle, G., & Homayouni, S. (2022) City-Region or City? That is the Question: Modelling Sprawl in Isfahan Using Geospatial Data and Technology, GeoJournal, pp. 1–21, https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10708-021-10554-8.

- Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., Matthews, S. A., & Ardalan, A. (2018) Measuring Spatial Accessibility to Urban Facilities and Services in Tehran, Spatial Demography, 6(1), pp. 17–34.

- Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., Mohammadi, S., Saber, M., Amini, S., & McArdle, G. (2022) Spatiotemporal Analysis of NO2 Production Using TROPOMI Time-Series Images and Google Earth Engine in a Middle Eastern Country, Remote Sensing, 14(7), pp. 1725.

- Rashki, A., Middleton, N. J., & Goudie, A. S. (2021) Dust Storms in Iran – Distribution, Causes, Frequencies and Impacts, Aeolian Research, 48, pp. 100655.

- Reichman, H. (2019) The Future of Academic Freedom (Baltimore, MD: JHU Press).

- Sadeghi, R., Abbasi-Shavazi, M. J., & Shahbazin, S. (2020) Internal Migration in Iran, in: Bell, M., Bernard, A., Charles-Edwards, E. & Zhu, Y. (eds) Internal Migration in the Countries of Asia: A Cross-National Comparison, pp. 295–317 (Springer International Publishing), https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-030-44010-7#about-this-book.

- Shabani, M., Darvishi, S., Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H., Alavi, S. A., Choudhury, T., & Solaimani, K. (2022) An Integrated Approach for Simulation and Prediction of Land Use and Land Cover Changes and Urban Growth (Case Study: Sanandaj City in Iran), Journal of the Geographical Institute Jovan Cvijic, SASA, 72(3), pp. 273–289.

- Tanhaa, F., Rabiei-Dastjerdi, H. R., & Mahmoudian, H. (2023) The Impact of Internal Migration on the Sex Ratio of Iranian Counties in the 2011 to 2016 Period; Application of Geographically Weighted Regression, Journal of Population Association of Iran, 17(34), pp. 207–240.

- Teimouri, A. (2022) The Mahdavī Society: The Rise of Millennialism in Iran as the Cultural Outcome of Social Movements (2000–2016), Middle East Critique, 31(2), pp. 125–145.

- Valadbaygi, K. (2021) Hybrid Neoliberalism: Capitalist Development in Contemporary Iran, New Political Economy, 26(3), pp. 313–327.

- Yazdandoost, F. (2016) Dams, Drought and Water Shortage in Today’s Iran, Iranian Studies, 49(6), pp. 1017–1028.

- Zeaiean, P., Rabiei, H. R., & Alimohamadi, A. (2005) Detection of Land Use/Cover Changes of Isfahan by Agricultural Lands around Urban Area Using Remote Sensing and GIS Technologies, The Journal of Spatial Planning, 9(4), pp. 41–54.

![Figure 1. Geography of Iran [Source: compiled by Author].](/cms/asset/672d5cf6-e3c4-4c34-aede-f88a77e83429/ccri_a_2256144_f0001_c.jpg)

![Figure 3. Cities with more than 100k population in 2016 [Source: compiled by Author Based on Statistical Centre of Iran Data].](/cms/asset/fb585156-73ec-454d-9260-19668944f6a8/ccri_a_2256144_f0003_c.jpg)