ABSTRACT

Organizations conducting global environmental assessments (GEAs) face the challenge of not only producing trustworthy and policy-relevant knowledge but also recruiting and training experts to conduct these GEAs. These experts must acquire the skills and competencies needed to produce knowledge assessments. By adopting an institutional approach, this paper explores IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure that aims to communicate and form the expertise that is needed to conduct its assessments. The empirical material consists of IPBES’s educational material, which teaches new experts how to perform the assessment. The analysis finds three crucial tasks that experts introduced in the assessments are expected to learn and perform. The paper concludes by discussing the broader importance of the findings that organizations that conduct GEAs are not passive intermediaries of knowledge but instead, through their epistemic infrastructure, generate ways to understand and navigate the world, both for those who create and those who receive the assessment report.

1. Introduction

In acomplex society where specialized science produces endless amounts of results, there is aneed to summarize and condense this knowledge to make it relevant and useable for decision-makers. International expert organizations have been developed in most environmental areas, all intending to conduct global environmental assessments (GEAs) aimed at enabling science-based policy decisions and agreements (Jabbour and Flachsland Citation2017; Castree etal. Citation2021).Footnote1 These organizations’ work– producing and communicating knowledge assessments– is crucial for mobilizing support for sustainable development and navigating it (Cash etal. Citation2003). How to develop usable knowledge for the governance of global environmental problems has become aburning question within the science– policy nexus (Harvey etal. Citation2019; Lidskog & Sundqvist Citation2022). As abroad overview of scientific bodies connected to international environmental regimes has found, to be able to “speak truth to power”, there is aneed to both create and package knowledge in away that makes it scientifically credible as well as understandable and relevant for its target groups (Haas and Stevens Citation2011).

A particular challenge for international assessment organizations to create trustworthy assessments is the constant need for experts who can understand abroader knowledge field than their own and who hold competencies in methodologies for producing knowledge assessments. These experts must acquire new competencies and skills by learning how to conduct assessments. Assessment organizations need to develop an infrastructure for assessments that consists of rules and procedures as well as resources and training for how to apply these rules in practice. If this is not put in place, the character and quality of the assessment will vary depending on the individual assessors. This may endanger not only the credibility of aparticular assessment but also the credibility of the whole organization. To remain atrustworthy source of credible and policy-relevant knowledge, assessment organizations must both develop an institutionalized way to conduct assessments and socialize their experts into aparticular culture of shared practices that includes how to use this infrastructure. Whereas there are these strong expectations attached to GEAs (Riousset etal. Citation2017), the institutional features needed to meet these expectations have not been sufficiently investigated.

In this study, we focus on aparticular assessment organization– the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)—to explore the question of how the organization’s expertise is defined and developed through its infrastructures and training material used to introduce new experts to the organization. The guiding research question is the following: what skills and competencies are needed, according to the IPBES, to perform the assessment? We thereby explore what expertise the IPBES seeks to develop as it introduces new experts to the epistemic infrastructure of the IPBES’s assessment process.

There are several reasons why we selected the IPBES for this study. Founded in 2012, IPBES has become acrucial knowledge provider to the Convention on Biological Diversity (Hughes and Vadrot Citation2019), and the IPBES secretariat has cooperation agreements with the convention as well as other conventions such as the Ramsar conventions, Cites and UNCCCD (IPBES Citation2022). It has already conducted eight assessments and initiated another five. Even though already quite experienced in terms of making assessments, IPBES is still at the beginning of the institutionalization of practices for how to perform their assessments. In contrast to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), which was formed more than three decades ago, the IPBES is aless mature organization, and its work– rules, routines, and practices– is less stabilized. Furthermore, its knowledge field– biodiversity—is extremely complex, including not only abroad array of scientific knowledge but also indigenous and local knowledge (Díaz etal. Citation2015; Dunkley etal. Citation2018; White and Lidskog Citation2023). This makes IPBES an interesting case to explore how experts are introduced to how to evaluate complex and transdisciplinary knowledge. By investigating expectations on expertise that IPBES through their training material communicates to new experts, this paper provides important knowledge about how the organization’s epistemic infrastructure and work develop and form the expertise that it needs to conduct GEAs. Whereas IPBES’s recruitment of experts has been studied (Montana and Borie Citation2016; Gustafsson and Lidskog Citation2018; Timpte etal. Citation2018), there is not yet any study on the next step: how new experts are introduced to their position.

This paper focuses on the infrastructure of the IPBES’s assessment process, how this infrastructure sets the stage and impacts knowledge production, and how this infrastructure and the expectations that come with it are introduced and communicated to new experts. This means that it explores the institutional conditions and not the insitu training practices or practical outcomes of IPBES’s work. In particular, we are interested in the competencies and skills that IPBES communicates and emphasizes as crucial while seeking and training its experts. Whereas many expert studies stress how expertise is acquired through informal socialization and collaborations with peers (e.g. Collins and Evans Citation2007; Lidskog and Sundqvist Citation2018), this paper provides important knowledge on the formal side in terms of the explicit communication and introduction of IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure through its introduction documents and tools as part of the organization’s objective to build capacity and thus to support new experts in acquiring the competencies that the organization finds crucial for its work.

The paper is divided into six parts, including this introduction. In thesecond part, we develop our analytical approach, which is an institutional and practice-oriented understanding of GEAs. We claim that epistemic infrastructure and culture are relevant to understanding what is needed to conduct aknowledge assessment. The third part presents the paper’s empirical material and analytical focus. The empirical material consists of The IPBES Guide on the Production of Assessment and The IPBES E-learning tool. Together, the educational material aims to inform new experts on how to perform an assessment, that is, how to use the IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure for knowledge assessments. The material is analysed with respect to epistemic infrastructure and culture by exploring the degree of formalization of the social and cognitive aspects of IPBES’s knowledge production. As the IPBES has partly used the IPCC as ablueprint, the analysis occasionally relates to how the IPCC works. The following two parts analyse this educational material, particularly how IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure and culture are communicated and taught to new experts. Part four describes the design and infrastructure of IPBES’s assessment work, from how it is initiated via its assessment of current knowledge to the communication of the assessment result. Part five investigates the competencies and skills that IPBES presupposes that its experts hold, and therefore, new experts need to acquire. The sixth part draws four conclusions of wider importance for IPBES as well as other expert organizations conducting GEAs.

2. Epistemic infrastructure and culture

GEAs are crucial for developing science-based regulation. It is, however, contested under which conditions and through which mechanisms GEAs matter for international regulation and in what aspects they matter (Lidskog and Sundqvist Citation2015; Castree etal. Citation2021). Analyzing GEAs’ influence on agreements and regulations is also complicated because there is no unidirectional influence between science and policy; instead, they mutually influence each other (Mahony and Hulme Citation2018). The organizations that conduct GEAs are best understood as boundary organizations involving both political and scientific representatives, ideals, and practices (Guston Citation1999; Miller Citation2001). The mission of GEAs is to perform assessments of knowledge within aparticular policy area and communicate it to policy-makers, thereby making it possible to develop international agreements and regulations that are science-based or at least informed by science.

To conduct GEAs, as in scientific knowledge production, there is aneed for internal organization and infrastructure that make it possible to develop, stabilize and circulate knowledge. Thus, epistemic infrastructure is crucial, as well as an epistemic culture that guides the members on how to use this infrastructure in avalid way (Knorr Cetina Citation2007). Epistemic infrastructure refers to the knowledge organization’s devices, methods, equipment, concepts, and rules for knowledge production; epistemic culture refers to skills and competencies (acknowledged as well as tacit) for how to use this infrastructure to create and warrant knowledge; and epistemic practice refers to actions that make objects knowable (Knorr Cetina Citation1999, p.246). Thus, epistemic practices are guided by an infrastructure that makes certain knowledge practices possible, ashared culture that explains how scientific evidence is found and established, the meaning of the empirical and its relation to theory, how to interpret an obtained result, and so on. Epistemic infrastructure and epistemic culture enable practices but not in adeterministic way. The reason for this is that practices derive not only from asingle source (a particular organization with its epistemic infrastructure and culture) but also from several sources (Knorr Cetina Citation2007). Therefore, practices may develop that challenge and change the established infrastructure and culture.

Focusing on epistemic infrastructure, culture, and practice is relevant for analysing the expertise of GEAs. The assessment work concerns rules for classifying and ordering phenomena, methodologies for selecting, interpreting, and evaluating empirical materials (published scientific texts), and rules for how to reach conclusions, present them in written form, and communicate them strategically. Like science, GEAs consist of institutional machinery that includes an epistemic infrastructure that enables this work, ashared epistemic culture that provides guidance on how to use this infrastructure, and trained members who have achieved the necessary skills to conduct this work. This means that we, like Oppenheimer etal. (Citation2019), do not see GEAs as asimple summary of established knowledge but as away to create new knowledge. Thus, assessment work is organized as aknowledge system of its own, designed to produce and distribute aparticular epistemic outcome, namely, policy-relevant knowledge.

There is, however, acrucial difference between assessments and research. Within expert studies, acommon distinction is made between contributory and interactional expertise (see, e.g. Collins and Evans Citation2007, pp.13–44). Contributory expertise means that aperson has acquired the skills necessary to contribute to aknowledge field. Interactional expertise means that aperson has mastered the language of this field but not its practices. In science, it is the researcher’s contributory expertise that is mainly requested (the knowledge production that the individual researcher is trained for). In addition to this expertise, interactional expertise– the competence to understand knowledge fields other than one’s own– is welcomed, especially in multidisciplinary and problem-oriented research. For GEAs, the individual researcher’s contribution is more complicated. GEAs can be understood as abounded space of knowledge production, but where the participants arrive from different epistemic locations from which they have appropriated particular epistemic practices.

Researchers have primarily been socialized into different research fields with different ways of constructing epistemic objects and different methods of studying them. When becoming experts and assessors in aGEA, the individual researchers must partly leave their competence areas (their contributory expertise) and evaluate abroader field of knowledge, consisting of knowledge that they do not have the competence to produce themselves (to conduct interactional expertise). This means that they must learn to work in the context of the epistemic infrastructure of the assessment, acquire the methodologies and practices for assessing and synthesizing knowledge to develop new competencies and skills (of making assessments), and thereby develop anew form of contributory expertise.

This composition implies achallenge for the expert organization, in that it needs to develop and uphold an epistemic infrastructure and an epistemic culture that support its members (the assessors) to uniformly conduct assessments, irrespective of their primary research socialization and disciplinary belonging. This is probably the reason that assessment organizations, compared to research organizations, have more formal rules and administrative hierarchies. There are formal rules on how to nominate and select members and guidelines for how to perform the review work (what knowledge to include and how to summarize it). There are also very diversified authorship positions (such as lead authors, coordinating lead authors, contributing authors, drafting authors, review editors, and chapter scientists). In this sense, assessment organizations are bureaucracies, aform of organization with hierarchies and impersonal rules making it autonomous from individual members’ interests and goals (Barnett and Finnemore Citation2004).

As stressed above, it is crucial but not sufficient to have administrative routines and explicit rules for how to perform assessments. There is also aneed for training and socializing the individual members on how to interpret and apply rules and use devices in asimilar way and to appropriate assessment skills that are impossible to make explicit and formalize. Like expert knowledge, assessment practices are learned partly through formal training exercises (courses, workshops, manuals, etc.) and partly through informal socialization (becoming part of an expert community that masters and practices these skills). Originally arriving from different research settings, the assessors must get to know and manoeuvre anew epistemic infrastructure to conduct an assessment. Thereby, an expert organization can stabilize its processes (the assessment work) and its product (the assessment report), that is, coordinate and train itself to speak with asingle voice to inform environmental governance.

3. The study: empirical and analytical focus

This study analyzes the competencies and skills that IPBES expects its experts to hold and new experts to acquire. This is done by studying the two learning tools that IPBES has developed to introduce new experts to IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure and to train them in the skills required to perform the assessment. The IPBES Guide on the Production of Assessment (IPBES Assessment Guide) is awritten guide consisting of two sections that introduce IPBES as an organization and its four stages of the assessment process. The IPBES Assessment Guide is described as a“living document which will be updated and expanded over time to reflect the work of the IPBES task forces, expert groups and experiences of experts involved in IPBES assessments” (IPBES Citation2023c). The IPBES E-learning tool consists of three modules. This material is developed to prepare new experts for what an IPBES assessment entails, what IPBES requires of them, and how an assessment is done. The empirical material was collected and analysed in 2021.Footnote2

For expert organizations with in-house experts, new employees can gradually appropriate the epistemic culture and learn how to conduct work tasks (how to properly use the epistemic infrastructure). This is not an option for organizations such as IPBES, with external experts brought in for time-bound and task-specific assignments who are employed at another organization. Instead, they must be instructed on how to perform an assessment, and therefore, documents such as this learning material become decisive in communicating the organization’s epistemic core to new experts and thus creating stability in what the organization is and does. This is not least important for IPBES and similar expert organizations, where the experts, besides coming and going, vary greatly in terms of seniority,Footnote3 methodological skills, disciplines, and knowledge systems (Dunkley etal. Citation2018). By analysing IPBES training material, it thereby becomes possible to find and explore what skills and competencies an expert is expected to possess to be able to conduct knowledge assessments, that is, to serve as an expert within IPBES.

For this study, it is important to separate the formalization of the social and cognitive aspects of knowledge production. For example, it has been shown that the IPCC’s assessment process is characterized by ahigh degree of formalization of social aspects (e.g. how to select reviewers and assign roles and responsibilities to them) and arather low formalization of cognitive aspects (e.g. how to select material to assess and how to condense it) (Sundqvist etal. Citation2015). In our analysis of IPBES learning material, we find the same kind of far-reaching social formalization. In the next section (section four), we show how this formalization creates an assessment process with an epistemic infrastructure that in part is very structured. Thus, to conduct an assessment following IPBES design, the experts who author the assessment need to be informed about this process. However, the learning tools do not identify any specific skills that need to be acquired by new experts to be able to use this infrastructure. In contrast to the IPCC, the learning material also contributes to cognitive formalization. Thereafter, in section five, we find and analyse how the learning material focuses on three crucial infrastructural aspects that formalize cognitive procedures in the assessment process, which substantially influence how to perform assessments. First, IPBES’s conceptual framework functions as an obligatory point of passage that is unique for IPBES, with apervading impact on its knowledge assessments. Second, there is guidance on how to assess the level of confidence in the assessed knowledge, aconfidence assessment that is done to offer guidance for the reader of the assessment on how to interpret its content and identify knowledge gaps. Third, the guidance on how to present the results aims to teach new experts how to formulate and present the assessment results in the assessment report to make it understandable and trustworthy. The analysis finds that the learning material is written with the belief that new skills are required to be able to use IPBES infrastructure and perform assessments and that it is the new experts who have the responsibility to acquire them. To some extent, these skills may overlap with what is required by other assessment organizations, such as the IPCC, but which in many respects are unique to IPBES. The following two sections analyse how IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure and culture are communicated to new experts and what skills and competencies IPBES finds necessary to perform its assessments.

4. The design and epistemic infrastructure of IPBES assessments

The epistemic infrastructure of IPBES’s assessments consists of four main stages. These stages rely heavily on IPBES’s rules and procedures that have been decided by the Plenary (e.g. IPBES Citation2013a; Citation2015) and are introduced to new experts through the IPBES Assessment Guide and the IPBES’s E-learning tool. In this section, we will analyse and describe the design and epistemic infrastructure of IPBES’s assessment work, from how it is initiated via its assessment of current knowledge to the communication of the assessment result.

Throughout the presentation of the four stages of the assessment, we can see how the responsibility for the assessment is passed back and forth between the realms of policy and science, making the assessment aprocess of collaboration and coproduction of knowledge (cf. Gustafsson etal. Citation2020; Hughes etal. Citation2021; Montana Citation2021). However, who represents policy and science differs in the different stages. In the assessment, thepolitical part is represented by actors such as national focal points (appointed by themember state to be its contact point with the IPBES), delegates (who represent the member states in the IPBES’s Plenary), and reviewers (who contribute to the quality control of the assessment by participating in the assessment’ssecond round of external reviews). In general, the political part carries the responsibility to make formal decisions about the assessment, submit requests for assessments, initiate ascoping assessment as well as afull assessment report, approve the summary for policy-makers, and accept the assessment chapters. All these decisions are made by the IPBES’s Plenary through consensus decisions and allow the process to progress through its four stages.

Science, on the other hand, is presented as represented by individual experts. The expert role in the IPBES includes differences in responsibilities and roles (such as co-chairs, coordinating lead authors, lead authors, fellows, contributing authors, review editors, and reviewers) as well as in what kind of knowledge systems they represent (science, social sciences, humanities, indigenous and local knowledge). These experts carry the responsibility to execute the decisions that are made by the political part and to produce the assessment report, work that primarily takes place in the first two stages of the assessment process.

The first stage of the assessment is titled request and scope. It starts with member states submitting topics in need of knowledge assessments. Thereafter, the experts in the Multidisciplinary Expert Panel (MEP) and the Bureau suggest aprioritization of these topics. Aspecially assigned expert group then produces ascoping document, and finally, the plenary decides which assessments to perform and when they should be done. This initial stage is crucial and heavily influences the outcome of the assessment because it determines the questions that should be explored and the methods that should be applied. Writing the scoping documents includes identifying the scope, geographical boundaries, and relevance of the assessment; outlining chapter content, appropriate methodological approaches, and important partnerships; and clarifying atimetable, estimated costs, and capacity-building needs. Thus, together with the IPBES’s rules and procedures for how to execute an assessment, it is the scoping document’s framing of the assessment that provides the infrastructure for thesecond stage of the assessment.

Expert evaluation is thesecond stage and consists of assessment work, which normally takes place over three years and follows acarefully planned and organized process on what to do and when and how to do it. The stage starts with the assembly of the expert group that will take the key expert roles (co-chairs of the assessment, coordinating lead authors, lead authors, and review editors). Thus, it is within this stage that we find the largest number of assessment experts. Candidates to participate in the different expert roles are nominated by the member states, the scientific community, and stakeholders and selected by the MEP to create aqualified and well-balanced expert group.Footnote4 Afirst- andsecond-order draft is circulated for review before afinal version of the assessment report is presented to the Plenary for adecision on acceptance. The first-order draft is reviewed by external expert volunteers from the scientific community, and thesecond-order draft is reviewed by governments and relevant stakeholders. Under pre-pandemic circumstances, the key experts gathered for aone-week meeting during each of the three rounds of drafting the assessment report. The summary for policy-makers is written by the co-chairs and the coordinating lead authors in two rounds and reviewed in parallel with thesecond-order draft of the full assessment.

Approval and acceptance of the final assessment report is the third stage of the assessment and takes place at the Plenary meeting, where co-chairs and coordinating lead authors of the assessment together with representatives from the MEP, the Bureau, and support staff assist the delegates in their work on accepting the assessment chapters and approving the Summary for policy-makers line by line. The negotiations follow IPBES’s rules and procedures for Plenary sessions, and the decision to accept the assessment chapters and approve the Summary for policy-makers is taken through consensus.

The use of the final assessment findings is the fourth stage of the assessment and consists of the communication of the results of the assessment report. Acommunication strategy is already developed in thesecond stage of the assessment. The implementation of the strategy starts with the official launch of the assessment report. Before this launch, individual experts were forbidden to give interviews or release content from the assessment report. Therefore, IPBES can control the presentation of the assessment’s key messages and findings.

Thus, we find that IPBES’s assessment is acomplex and, at the same time, very structured process that aims to govern the assessment process through an extensive social formalization aimed at producing robust and trustworthy results. The infrastructure assigns roles, organizes meetings, sets deadlines, and moves the assessment process along, thereby assuring that the assessment is done on time and follows the established procedures. To navigate within the assessment– to know what to do when and where– the learning material signals that the individual experts in the assessment are expected to be informed of this structure. However, for the assessment to become trustworthy, it is not sufficient for the organization to develop this kind of formalized epistemic infrastructure that organizes and moves the process forward. The involved experts also need to acquire the necessary skills and knowledge in how to perform their assigned roles. This leads to the question of what kind of expertise is needed to perform IPBES’s assessments, what competencies and skills need to be learned when entering the assessment, and what kind of cognitive formalization is taking place through IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure and culture to communicate these expectations and to teach these skills.

The next section examines IPBES learning materials to see what competencies and skills IPBES assumes its experts possess and thus need to acquire.

5. Competences and skills needed to perform an assessment

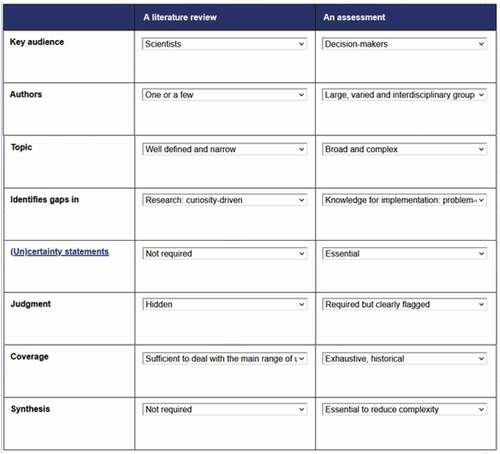

The IPBES assessment is commonly described as acomprehensive review of all current knowledge on aspecific topic, which is also how the IPBES Assessment Guide and the E-learning tool describe it. However, the E-learning tool emphasizes that reviewing and synthesizing the literature in an IPBES assessment is qualitatively different from ascientific literature review. It makes these differences explicit by making the comparisons in afill-in exercise, as shown in .

Figure 1. Comparing an IPBES assessment and aliterature review in the E-learning tool (Module 2, Lesson 1, p.14).

Based on these analyses of the learning material, we find that what all experts are expected to do in an assessment can be summarized in three related tasks. First, they are expected to review and synthesize the literature from the perspective of IPBES’s conceptual framework. Second, they are expected to analyse and assess the level of certainty of the reviewed and synthesized knowledge. Third, they are expected to present the results of the assessment in the assessment report, including accounting for the level of certainty in these results in alanguage that makes the knowledge policy-relevant but not policy prescriptive. The tasks should be performed to meet the objectives set by the scoping document. This could entail analysing the status and trends, using scenarios and modelling to develop descriptive storylines to illustrate possible futures, valuing nature’s benefits, including ecosystem services, mobilizing indigenous and local knowledge, analysing response options to enhance the contribution of ecosystem services to human well-being, or developing policy support tools and methodologies. To meet the expectations inherent in these three tasks, there is aneed for both interactional and contributory expertise specific to IPBES. In what follows, we will analyse how these three tasks are introduced to new experts by offering them training in (i) how IPBES’s conceptual framework should guide the review and synthetization of knowledge, (ii) how the level of certainty of reviewed knowledge should be analysed and assessed, and (iii) how the result of the assessment should be communicated.

5.1. Reviewing and synthesizing the literature from the perspective of the IPBES conceptual framework

The first of the three modules of the E-learning tool focuses on IPBES’s conceptual framework and its importance for the assessments (see ). The framework consists of six elements and describes the interlinkages between them by bringing together Western science with other knowledge systems such as indigenous and local knowledge (Díaz etal. Citation2015, IPBES Citation2013b). Together, the elements describe and explain the relation between nature and society as “a social-ecological system that operates at various scales in time and space” (IPBES Citation2023b). The conceptual framework was developed by aspecially assigned group of experts at the request of the Plenary and was adopted as the IPBES’s official conceptual framework “to support the analytical work of the Platform, to guide the development, implementation, and evolution of its work programme, and to catalyse apositive transformation in the elements and interlinkages that are the causes of detrimental changes in biodiversity and ecosystems and subsequent loss of their benefits to present and future generations” (IPBES Citation2023b).

Figure 2. IPBES’s conceptual framework (Source: IPBES Citation2023b [updated from Díaz etal. Citation2015]).

![Figure 2. IPBES’s conceptual framework (Source: IPBES Citation2023b [updated from Díaz etal. Citation2015]).](/cms/asset/6ffe84fd-1ef0-453b-8149-8c1212ec3d3a/nens_a_2187844_f0002_oc.jpg)

The E-learning module introduces the conceptual framework as IPBES’s description of the relationship between people and nature, accounts for the framework’s different parts, and describes how it seeks to “organize thinking and structure the work that needs to be accomplished when assessing complex ecosystems, social arrangements, human– environment interactions” (E-learning Module 1, Lesson 1, p.9 [bold in original]). The E-learning module also goes into the details of how the framework describes “the interrelationship between biodiversity and ecosystems and human quality of life, at different spatial and temporal scales, and from the perspective of different worldviews (including e.g. western science and indigenous and local knowledge)” (E-learning Module 1, Lesson 2, p.4). By learning and applying the conceptual framework, the experts acquire new analytical tools to use when gathering, structuring, and assessing knowledge of interest for the assessment.

Being able to use the conceptual framework competently is portrayed in the material as astarting point for all IPBES’s work and acrucial skill when reviewing and synthesizing knowledge from different knowledge systems in IPBES’s assessments. Thus, the conceptual framework is to be understood as the core of IPBES’s epistemic culture; it provides alanguage for communicating between knowledge systems (interactional expertise) and analytical tools for reviewing and synthesizing what is currently known and unknown on the topic that is assessed (contributory expertise). Given its central role in the organization, the conceptual framework takes IPBES one step further than other GEAs; the framework becomes an epistemic infrastructure that includes aformalization of the cognitive aspects. The conceptual framework is developed and introduced to new experts through the learning material to create ashared and common understanding of how nature and society relate to one another and how these relations create ecosystem services, nature’s contribution to people, and changes in the planet’s biodiversity (see Dunkley etal. Citation2018 for an in-depth analysis of the conceptual framework). However, the formalization goes only that far; it is still up to the individual experts to develop what it means in practice to use this conceptual framework and to develop the interactional expert skills needed to do so (cf. Sundqvist etal. Citation2015). This is alearning process that falls outside the scope of this study but needs to be studied further.

5.2. Making uncertainty statements

Estimating and communicating the confidence level of the synthesized knowledge is aparticular task that makes an IPBES assessment different from atraditional research review. This is portrayed in the learning material as requiring aspecific form of contributory expertise, which needs to be appropriated by IPBES’s experts to participate in the assessment. IPBES’s Plenary has adopted amodel that almost completely mirrors the one developed and used by the IPCC, and it is presented in both the IPBES Assessment Guide and the E-learning tool.

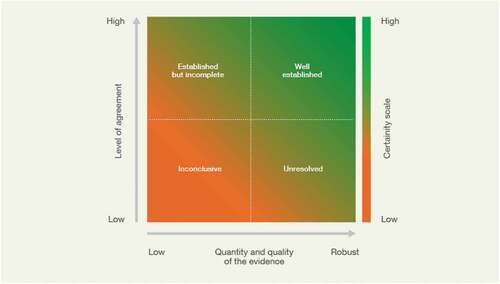

The confidence level of the reviewed research should be assessed and described using four confidence categories (see ). Among the four confidence categories, inconclusive has the lowest level of certainty, and well established has the highest level of certainty. Confidence levels are also used to communicate the probability that adescribed outcome will occur. These levels are expressed using quantitative probabilistic estimates ranging from aprobability of<1% (exceptionally unlikely) to>99% (virtually certain). The confidence terms are to be communicated as part of the key findings of the assessment, as they are presented in the executive summary of each assessment chapter.

Figure 3. Model for assessing the certainty level of the knowledge (Source: IPBES assessment guide, p.30).

The assessment of certainty levels also includes identifying knowledge gaps and areas in the field where knowledge is lacking. As described in the IPBES Assessment Guide:

IPBES assessments not only focus on what is known, but also on what is currently uncertain. Assessments play an important role in guiding policy through identifying areas of broad scientific agreement as well as areas of scientific uncertainty that may need further research.

The work on identifying knowledge gaps and strengthening the knowledge foundation is done within the assessment in collaboration with IPBES’s task force on knowledge and data and its task force on indigenous and local knowledge. Thus, through cognitive formalization, this collaboration is structured to go beyond the individual assessments; it includes the building of contributory expertise among experts in different organizational bodies of IPBES and creates an epistemic culture within IPBES on how to analyse and assess knowledge from the perspective of confidence levels and the identification of knowledge gaps.

5.3. Presenting the results of the assessment

Presenting and communicating the assessment is the third task that our analysis has identified in the learning material and one for which all the assessment experts have aresponsibility. It is presented as requiring the development of contributory and interactional expertise that makes IPBES aunique epistemic culture by its specific way of writing the assessment report to present its result. The communication within the assessment report should aim to make the results easy to understand and policy-relevant, but not in away that makes them policy prescriptive. Both the IPBES Assessment Guide and the E-learning tool devote much space to instructing how to write the assessment report and the summary for policy-makers. In addition to offering extracts from previous assessments as examples, the E-learning tool also offers the following recommendations as guidance on how to write the assessment report ().

Figure 4. Instructions for how to present and communicate the assessment. The figure is acompilation of the exact text from interactive text boxes with general writing tips in the E-learning tool (Module 2, Lesson 3, p.29).

At the core of these recommendations lies the importance of using neutral and clear language to communicate what the knowledge says is the current state of biodiversity and ecosystem services, what recommendations, based on this knowledge, could be given on possible paths forward, and to offer this knowledge and recommendation without becoming prescriptive. Thus, even if it shares some similarities with scientific writing, it differs in many aspects. Furthermore, by focusing on the differences in relation to scientific writing, the learning material signals to new experts that appropriation of these writing and communication skills is required to function as an expert in the assessment. However, these communication guidelines, which are part of the IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure, influence not only the form of communication but also the content, i.e. what is permissible to say. The guidelines contain acognitive formalization concerning how knowledge can be discussed, what we know about biodiversity and the problems it faces, how we have this knowledge, and what needs to be done to mitigate these problems. The guidelines implicitly communicate arequirement for aspecific form of contributory expertise that new experts need to develop to be able to contribute policy-relevant but not policy-prescriptive knowledge in the IPBES’s assessment reports.

6. Concluding discussion

The growing demand for policy-relevant science has resulted in new sites for shaping expert knowledge and informing decision-making (Turnhout Citation2019; Montana Citation2020). Providing expert knowledge requires navigation in asocial landscape with conflicting interests and divergent beliefs about what knowledge is and how the world is constituted (Lidskog etal. Citation2022). In this landscape, scientific experts must make knowledge assessments in away that makes it relevant for decision-makers without affecting their scientific legitimacy to be credible for both their target groups and their peers. Thus, it is adelicate task for individual experts as well as expert organizations to provide advice in away that does not undermine the epistemic authority of the expertise.

In this paper, we have explored the infrastructure of IPBES’s assessment process, how this infrastructure sets the stage and influences knowledge production, and how this infrastructure through IPBES’s learning material has been introduced and communicated to new experts. We have identified and analysed what is seen as crucial expert competencies and skills needed to produce IPBES’s GEAs. In this concluding section, we draw and discuss four conclusions of wider importance for IPBES as well as other expert organizations conducting GEAs.

First, the analysis has shown that there is institutional machinery behind all GEAs and that skills and competencies need to be appropriated to make use of this infrastructure. With non-employed experts, it is not only achallenge to recruit new experts but also to introduce them to the epistemic infrastructure of an organization. Thus, for this kind of expert organization– an organization with few permanent staff and where experts spend only asmaller part of their work time– it is not sufficient to trust informal socialization (being part of acommunity of experts and gradually being socialized to become an expert); formal educational programs are needed (cf. Harden-Davies etal. Citation2022). In this work, IPBES has an advantage in comparison to other GEAs in that it, in addition to working on knowledge assessments, is also mandated to build the capacity to “enhance knowledge and skills of institutions and individuals to enable and facilitate engagement in the production and use of IPBES products” (IPBES Citation2023a [bold in original]). This capacity-building objective acknowledges the importance of formal educational programs (Gustafsson Citation2021).

Second, the analysis has shown that the institutional machinery behind the GEA also sets the stage for and thus influences the content of the assessment (what to assess, how to assess it, and how to communicate it). For example, the IPBES shares with the IPCC afar-reaching formalization of the social aspects of assessments (an institutional design for how to organize the assessment, including procedures for selecting reviewers and the different and very structured steps in the assessment) (cf. Sundqvist etal. Citation2015). However, in contrast to the IPCC, the IPBES also includes amore explicit formalization of cognitive aspects (how to select material and how to interpret it through the IPBES conceptual framework), an observation that is important to keep in mind and learn from when studying other GEAs. The cognitive formalization processes of IPBES’s epistemic infrastructure include its conceptual framework that experts are expected to make use of in the assessment and that fosters aparticular understanding of how both different knowledge systems and how society and nature are related. The epistemic infrastructure also includes the appropriation of aspecific language for communicating the assessment’s knowledge content but also in determining and communicating the certainty levels of the assessed knowledge.

Third, the analysis of the case of IPBES has shown that when conducting aGEA, experts not only make use of their interactional expertise (being able to understand and communicate with fields other than their own) but also rely on contributory expertise in that they make use of the epistemic infrastructure of the organization by applying methodologies unique to the assessment process that produce new expert knowledge (policy-relevant knowledge that did not exist before the assessment). Previous research has shown that scientific experts are nominated and selected as authors for IPBES assessments based on the interactional and contributory expertise they have acquired in the realms and practices of science (Gustafsson and Lidskog Citation2018). However, the analysis of this study has shown that to act as an expert in aGEA, such as an IPBES assessment, it is not enough for the experts to be able to contribute to the development of knowledge following the epistemic infrastructure, culture, and practice of science (Knorr Cetina Citation1999). To act as an expert in GEAs, one also needs to develop anew form of contributory expertise.

Fourth, and most challenging, the analysis has shown that GEAs and the expert organizations that conduct them are not passive intermediaries of knowledge. Through their epistemic infrastructure, culture, and practices, GEAs generate aspecific way to understand and navigate the world, both for those who participate in the construction of the assessment report and for those who read the final report as guidance for environmental governance. However, while epistemic practices and epistemic infrastructure generate new perspectives, knowledge, and guidance, they also restrict other possible perspectives from which to know and act in the same situation. Introducing new experts to the organization’s epistemic infrastructure and culture is asocialization project that aims to shape assessment practices, facilitate collaborations, and enable communication. This is necessary for creating knowledge and facilitating action, which is the objective of most GEAs. However, it also means that it is crucial to analyse the institutional setup (the epistemic infrastructure) of these organizations, what takes place in performing and delivering assessments (epistemic culture and practice), and the wider implications of those processes, both for those involved in the assessment work and those to whom the assessment reports are directed, including those who are tasked to make decisions in environmental governance.

This study focuses on what skills and competencies IPBES finds necessary to perform its assessments, that is, to in avalid way make use of its epistemic infrastructure and produce and communicate its GEAs. Additional research is needed to address the question of how the learning material is informing how experts conduct the assessment. This is an important next step in understanding how these assessments are made credible and influential in international environmental policy deliberations and agreements.

Highlights

GEAs are constituted by epistemic infrastructures, cultures, and practices

GEAs generate new ways to understand and navigate the world

The social and cognitive formalization of the assessment influences GEA content

Experts need to appropriate particular skills and competencies to conduct GEAs

Through socialization, experts in GEAs develop new contributory expertise

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability statement

Publicly available datasets were analysed in this study. The analysis is based on published and accessible work by the IPBES, Full references to these documents (including links to them) are given in the list of references.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Since 1977, more than 140 GEAs have been conducted, most often by organizations within the UN system (such as DESA, FAO and WMO) but also by other international organizations such as IEA and OECD (for an overview, see Jabbour and Flachsland Citation2017). Examples of recent GEAs are the Global Sustainable Development Report 2022, Global Environmental Outlook GEO-6 (2019) and IPCC 6th assessment reports(2022).

2. In fall 2022, the e-learning tool was reorganized. Two of the three previous modules were merged into one and anew module was developed on IPBES’s newly adopted data and knowledge management policy. Thus, the e-learning tool still consists of three modules, of which this study analyzes the first two. All references made to the empirical material have been adjusted to the new organization of the modules (January2023).

3. With regards to seniority, acrucial distinction is to be made between seniority within GEAs and seniority within research. Where the first makes them well equipped to engage in an IPBES assessment, thesecond form of seniority does not necessarily provide the skills and competencies required in aGEA. Thus, even senior researchers need to appropriate new skills and competencies to be able to conduct GEAs.

4. The selection process shall strive to create abalanced representation with respect to “relevant experts with an appropriate diversity of expertise and disciplines, gender balance and representation from indigenous and local knowledge (ILK) holders to ensure appropriate representation from developing and developed countries and countries with economies in transition” (IPBES Guide: p.12).

References

- BarnettMN, FinnemoreM. 2004. Rules for the World: international Organizations in Global Politics. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press.

- CashDW, ClarkWC, AlcockF, DicksonNM, EckleyN, GustonDH, JägerJ, MitchellRB. 2003. Knowledge systems for sustainable development. PNAS. 100(14):8086–19. doi:10.1073/pnas.1231332100.

- CastreeN, BellamyR, OsakaS. 2021. The future of global environmental assessments: making acase for fundamental change. Anthr Rev. 28(1):56–82. doi:10.1177/2053019620971664.

- CollinsH, EvansR. 2007. Rethinking expertise. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- DíazS, DemissewS, LonsdaleC, JolyW, LarigauderieN, AshA, AdhikariJR, AricoS, AricoS, BáldiA, etal. 2015. The IPBES conceptual framework— connecting nature and people. Curr Opin Environ Sustainability. 14:1–16. doi:10.1016/j.cosust.2014.11.002.

- DunkleyR, BakerS, ConstantN, Sanderson-BellamyA. 2018. Enabling the IPBES conceptual framework to work across knowledge boundaries. IntEnviron Agreements. 18:779–799. doi:10.1007/s10784-018-9415-z.

- GustafssonK. 2021. Expert organizations’ institutional understanding of expertise and responsibility for the creation of the next generation of experts: comparing IPCC and IPBES. Ecosyst People. 17(1):47–56. doi:10.1080/26395916.2021.1891973.

- GustafssonKM, Díaz-ReviriegoI, TurnhoutE. 2020. Building capacity for the science-policy interface on biodiversity and ecosystem services: activities, fellows, outcomes, and neglected capacity building needs. Earth Syst Gov. 4:100050. doi:10.1016/j.esg.2020.100050.

- GustafssonK, LidskogR. 2018. Organizing international experts. IPBES’s efforts to gain epistemic authority. Environ Sociol. 4(4):445–456. doi:10.1080/23251042.2018.1463488.

- GustonDH. 1999. Stabilizing the boundary between US politics and science: the role of the office of technology transfer as aboundary organization. Soc Stud Sci. 29(1):87–111. doi:10.1177/030631299029001004.

- HaasPM, StevensC. 2011. Organized science, usable knowledge and multilateral environmental governance. In: LidskogR SundqvistG, editors. Governing the Air: thedynamics of science, policy, and citizen interaction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; pp. 125–161.

- Harden-DaviesH, AmonDJ, VierrosM, BaxNJ, HanichQ, HillsJM, GuilhonM, McQuaidKA, Mohammed E, Pouponneau A, etal. 2022. Capacity development in the Ocean Decade and beyond: key questions about meanings, motivations, pathways, and measurements. Earth Syst Gov. 12:100138. doi:10.1016/j.esg.2022.100138.

- HarveyB, CochraneL, Van EppM. 2019. Charting knowledge co-production pathways in climate and development. Environ Policy Gov. 29:107–117. doi:10.1002/eet.1834.

- HughesH, VadrotA. 2019. Weighting the world: iPBES and the struggle over biocultural diversity. Glob Environ Polit. 19(2):14–37. doi:10.1162/glep_a_00503.

- HughesA, VadrotA, AllanJI, BackT, BansardJS, ChasekP, GrayN, LangletA, LeiterT, Marion SuiseeyaKR, etal. 2021. Global environmental agreement-making: upping the methodological and ethical stakes of studying negotiations. Earth Syst Gov. 10:100121. doi:10.1016/j.esg.2021.100121.

- IPBES. 2013a Decision IPBES-2/3: procedures for the Preparation of the platform’s deliverables. Decision from thesecond meeting of the plenary of the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. December 9–14. Antalya, Turkey: [accessed 2022 June 1]. https://ipbes.net/sites/default/files/downloads/Decision%20IPBES_2_3.pdf

- IPBES. 2013b. Decision IPBES-2/4: conceptual framework for the intergovernmental science-policy platform on biodiversity and ecosystem services. In Decision from the Second Meeting of the Plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; December 9–14; Antalya, Turkey:[accessed 2023 January 31] https://ipbes.net/sites/default/files/downloads/Decision%20IPBES_2_4.pdf

- IPBES. 2015. Decision IPBES-3/3: procedures for the preparation of platform deliverables. In Decision from the Third Meeting of the Plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services; January 12–17; Bonn, Germany: [accessed 2022 June 1]. https://ipbes.net/sites/default/files/downloads/Decision_IPBES_3_3_EN_0.pdf

- IPBES. 2022. Engagement related to multilateral environmental agreements. [accessed 2022 October 21]. https://ipbes.net/multilateral-environmental-agreements

- IPBES. 2023a. Building capacity. [accessed 2023 January 31] https://ipbes.net/building-capacity

- IPBES. 2023b. Conceptual framework. [accessed 2023 January 31]. https://ipbes.net/conceptual-framework

- IPBES. 2023c. Guide on the production of assessments. [accessed 2023 January 31]. https://ipbes.net/guide-production-assessments

- JabbourJ, FlachslandC. 2017. 40 years of global environmental assessments: aretrospective analysis. Environ Sci Policy. 77:193–202. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.05.001.

- Knorr CetinaK. 1999. Epistemic cultures: how the sciences make knowledge. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Knorr CetinaK. 2007. Culture in global knowledge societies: knowledge cultures and epistemic cultures. Interdiscip Sci Rev. 32(4):361–375. doi:10.1179/030801807X163571.

- LidskogR, StandringA, WhiteJ. 2022. Environmental expertise for social transformation: roles and responsibilities for social science. Environ Sociol. 8(3):255–266. doi:10.1080/23251042.2022.2048237.

- LidskogR, SundqvistG. 2015. When and how does science matter? International Relations meets science and technology studies. Glob Environ Polit. 15(1):1–20. doi:10.1162/GLEP_a_00269.

- LidskogR, SundqvistG. 2018. Environmental expertise as group belonging: environmental sociology meets science and technology studies. Nat Cult. 13(3):309–331. doi:10.3167/nc.2018.130301.

- LidskogR, SundqvistG. 2022. Lost in transformation: the Paris Agreement, the IPCC, and the quest for national transformative change. Front Clim. 4:906054. doi:10.3389/fclim.2022.906054.

- MahonyM, HulmeM. 2018. Epistemic geographies of climate change: science, space and politics. Prog Hum Geogr. 42(3):395–424.

- MillerC. 2001. Hybrid management: boundary organizations, science policy, and environmental governance in the climate regime. Sci Technol Hum Values. 26(4):478–500. doi:10.1177/016224390102600405.

- MontanaJ. 2020. Balancing authority and meaning in global environmental assessment: an analysis of organisational logics and modes in IPBES. Environ Sci Policy. 112:245–253. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.017.

- MontanaJ. 2021. From inclusion to epistemic belonging in international environmental expertise: learning from the institutionalisation of scenarios and models in IPBES. Environ Sociol. 7(4):305–315. doi:10.1080/23251042.2021.1958532.

- MontanaJ, BorieM. 2016. IPBES and biodiversity expertise: regional, gender, and disciplinary balance in the composition of the interim and 2015 multidisciplinary expert panel. Conserv Lett. 9(2):138–142. doi:10.1111/conl.12192.

- OppenheimerM, OreskesN, JamiesonD, BrysseK, O’reillyJ, ShindellM, WazecM. 2019. Discerning experts: the practices of scientific assessment for environmental policy. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- RioussetP, FlachslandC, KowarschM. 2017. Global environmental assessments: impact mechanisms. Environ Sci Policy. 77:260–267. doi:10.1016/j.envsci.2017.02.006.

- SundqvistG, BohlinI, HermansenEAT, YearlyS. 2015. Formalization and separation: asystematic basis for interpreting approaches to summarizing science for climate policy. Soc Stud Sci. 45(3):416–440. doi:10.1177/0306312715583737.

- TimpteM, MontanaJ, ReuterK, BorieM, ApkesJ. 2018. Engaging diverse experts in aglobal environmental assessment: participation in the first work programme of IPBES and opportunities for improvement. Innov Eur JSoc Sci Res. 31(sup1):S15–37. doi:10.1080/13511610.2017.1383149.

- TurnhoutE . 2019. Environmental experts at the Science-Policy-Society interface. In E. Turnhout, W. Tuinstra & W. Halffman (Eds). Environmental Expertise. Connecting Science, Policy and Society (pp. 222-233). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- WhiteJ, LidskogR. 2023. Pluralism, paralysis, practice: making environmental knowledge usable. Ecosyst People. 19(1):2160822. doi:10.1080/26395916.2022.2160822.