?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Conditional Cash Transfer (CCT) programmes are important anti-poverty programmes. There is relatively little evidence, however, of ongoing effectiveness several years after they have begun. Such evidence is particularly relevant for policymakers because programme effects may become larger or smaller over time. We analyse whether children exposed since birth to a CCT in El Salvador have better schooling outcomes at initial school ages. The results demonstrate that exposure significantly increased school enrolment and attainment for five-year-olds in preschool. The pattern of impacts suggests continued programme exposure might be improving primary school readiness or shifting norms around child investment.

1. Introduction

Conditional cash transfer (CCT) programmes are among the most important anti-poverty interventions in Latin America and the Caribbean. Two decades after their introduction they have operated in 18 countries and in 2013 benefited approximately 140 million people, a quarter of the population in the region.Footnote1 The programmes target poor areas and poor families, and typically make transfers to women. Conditionalities normally include preventive healthcare visits for children under five, and school enrolment and regular attendance for older children. Often these components are strengthened by health-related training and social marketing to encourage investment of the transfers in nutrition, health and education. In addition to alleviating short-term poverty, by promoting investment in human capital, CCTs also aim to reduce poverty in the long term.

Numerous rigorous evaluations of CCTs demonstrate beneficial short-term effects. These include increased consumption and reduced poverty at the household level, improved nutrition and health for young children, and increased school enrolment and attainment for older children (Fiszbein and Schady Citation2009; Bastagli et al. Citation2016; Parker and Todd Citation2017). Most research, however, examines impacts during the initial years of programme operation with comparatively little evidence for ongoing programmes several years after they have begun. This imbalance reflects the importance of early evaluation for ensuring that new programmes are effective, often a condition for continued funding or crucial for political support. The imbalance also reflects the difficulty of identifying programme impacts once coverage has expanded and control groups used in short-term evaluations have been incorporated into the programme. Even though programmes typically continue to be monitored, the standard monitoring and evaluation systems usually track processes and service delivery without estimating impact.

In this paper we assess the ongoing effectiveness of a typical CCT, the Salvadoran Comunidades Solidarias Rurales, using programme administrative data from 56 of the poorest rural municipalities in the country.Footnote2 We examine whether exposure to the CCT since birth led to higher enrolment and completed schooling for children ages five and six. Estimated impacts, therefore, represent the cumulative effects of the programme on children 5–6 years after it began. These include possible nutrition and health improvements during early childhood related to the transfers, conditionalities and other programme activities during those early years of life. Such improvements might contribute to earlier school readiness. Programme benefits in that period also might lead to increases in household wealth or changes in education norms. The cumulative effects also include possible increases in schooling outcomes at initial school ages related to the current (i.e. contemporaneous with time of measurement) transfers, conditionalities and other programme activities. We complement the analysis of schooling outcomes with an examination of household wealth, which helps distinguish between some of the possible mechanisms underlying the cumulative effects on schooling.

We use the programme eligibility rules and programme rollout with different incorporation dates in different municipalities to identify causal effects. At the start of the programme in each of the 56 rural municipalities incorporated between 2005–2008, families with a pregnant woman or at least one child under 15 years of age were eligible. Families with neither were ineligible at least until after 2013 when families were recertified. In other words, after it began in each municipality, programme enrolment was closed in that municipality. Included among the eligible were families in which a woman conceived her first child shortly before the incorporation of the programme in her municipality. Included among the ineligible, who form the comparison group, were families in which a woman conceived her first child shortly after the programme began. We estimate intent-to-treat (ITT) effects for firstborn children using an indicator of eligibility at programme incorporation and rely on an administrative programme census (in late 2012 and 2013) to obtain the long-term outcome measures for the study.

Within a national context of rising enrolment rates over the past decade, we find that CCT programme exposure of 5–6 years significantly increased preschool enrolment and early attainment at initial school ages. Five-year-old eligible children exposed since birth were approximately 9 percentage points more likely to have completed at least one year of preschool and 12 percentage points more likely to be currently enrolled. In contrast, there was little evidence of schooling improvements for six-year-olds exposed since birth, possibly because by that age most children had begun their schooling. There was, however, a more than one-third standard deviation improvement in a wealth index for households with a six-year-old.

As in most longer-term evaluations, an important threat to the identification strategy is selective migration into or out of the programme municipalities. We assessed the robustness of the findings to these and other potential biases.Footnote3

Early or on-time school entry can positively influence later schooling and is an important way in which CCTs can improve educational outcomes. There is limited evidence, however, on whether CCTs influence school entry. Behrman, Parker, and Todd (Citation2009) find a slight differential reduction (0.05 years), after 5.5 years of programme implementation, in the age of starting primary school for girls 7–8 years old exposed to the Mexican CCT 18 months longer than an experimental control. There were no significant effects for boys. They also find similar small absolute effects after 5.5 years for the fully exposed girls using matching methods and first-differences with a non-experimental comparison group.

Todd and Winters (Citation2011) use the same experiment with the 18-month differential exposure to estimate cohort difference-in-differences in school enrolment for six-year-olds. They motivate the analysis by highlighting the potential for CCT-induced improvements in early life nutrition and health outcomes (summarised in Parker and Todd Citation2017) to improve later schooling outcomes. Earlier exposure to the CCT increased the probability of on-time enrolment at age six in primary school in Mexico by approximately five percentage points. Their findings relate to the more general literature on the longer-term effects of CCT nutrition and health benefits during early childhood. The experimental evidence on longer-term effects is mixed. Some studies show sustained differences between initial treatment and control groups in cognitive, health or educational outcomes, whereas other studies show fade out (Fernald, Gertler, and Neufeld Citation2009; Barham, Macours, and Maluccio Citation2013; Araujo, Bosch, and Schady Citation2018; Cahyadi et al. Citation2020; Molina Millán et al. Citation2019; Citation2020).Footnote4 Non-experimental studies in Mexico and Colombia also show positive longer-term effects on education (Behrman, Parker, and Todd Citation2009; García et al. Citation2012).

We contribute to this literature by examining whether exposure to a CCT since birth leads to earlier entry into preschool. The paper underscores the potential importance of distinguishing between cumulative and current programme effects. More generally, the paper contributes to the literature on early school entry, particularly preschool, a potentially important driver of future school success (Berlinski, Galiani, and Gertler Citation2009; Berlinski, Galiani, and Manacorda Citation2008; Berlinski, Galiani, and McEwan Citation2011). Despite relatively high enrolment rates, early school entry has been hypothesised to be especially beneficial in El Salvador for reducing grade repetition in first grade of primary school, which historically has been around 20 percent (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010). The findings of the paper therefore have direct policy relevance, even if (due to the limitations imposed by working with administrative data) we cannot fully characterise the various possible pathways or assess physical, cognitive and other educational benefits more comprehensively.Footnote5

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 provides details of the Salvadoran CCT programme, findings from previous short-term impact evaluations and a description of the Salvadoran context. Section 3 describes data and methodology. Section 4 presents the estimated programme effects and provides related sensitivity analyses, and section 5 concludes.

2. The Salvadoran conditional cash transfer programme and schooling context

2.1. Programme design

El Salvador is a densely populated lower-middle income country; in 2013 the national poverty rate was 35 percent and the rural poverty rate 42 percent. The Salvadoran CCT began in late 2005 and by 2010 operated in the poorest 100 of the total 262 municipalities, benefiting over 100,000 families. In step with its expansion, the programme budget increased to 0.09 percent of gross national product by 2010. Afterwards it decreased modestly through 2013 because the original beneficiary rolls declined as families became ineligible, for example when their youngest child aged out or all children had completed the sixth-grade school requirement (de Sanfeliú, Lustig, and Oliva Citation2015). The CCT was designed with static or closed enrolment after each municipality was incorporated to maintain the target number of beneficiaries and adhere to the budget (Government of El Salvador Citation2005). Starting in late 2012, a new registry was collected in the 56 poorest rural municipalities to update the list of eligible households, providing the data source used in this paper.

Like most CCT programmes in the region, the Salvadoran CCT had both health and education components. For the health component, conditionalities included pre- and postnatal check-ups for women and growth monitoring and vaccinations for children under five. For the education component, conditionalities included enrolment and regular attendance (missing at most three days per month) through sixth grade for children 5–15 years old.Footnote6 Legally, primary schooling is compulsory from age seven in El Salvador, but six-year-olds considered to be prepared by their educational institution are allowed to start first grade as well. Those not considered prepared, or younger than six, can enrol in preschool. For children under seven and not yet in primary school, the CCT education conditionalities depended on preschool availability in the community. Specifically, the enrolment and regular attendance conditions were applied, and enforced, for children aged five or older at the start of the school year in communities with a preschool.Footnote7 They were not applied if the Ministry of Education verified there was no available preschool.

In addition, non-formal education in adult training workshops was offered to all beneficiaries. The wide-ranging training topics included the following: child health and nutrition; CCT conditionalities; child risk and child rights; sexual and reproductive health; gender equality; domestic violence; and participation and community organisation. Although not a condition for transfer receipt, workshop attendance was strongly encouraged and for mothers was high, in part because a majority understood them to be required (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2008; Adato, Morales Barahona, and Roopnaraine Citation2016).

Preschool in El Salvador is voluntary and spans ages 4–6 (formally with classes for each age). In principle, it focuses on integral development (fine motor, socioemotional and cognitive skills), promotion of self-esteem and development of the skills required for reading and writing (Ministry of Education Citation2013). Preschools are typically hosted in existing primary schools and the available evidence from the Ministry of Education indicates their widespread but not universal availability at the start of the programme, in approximately three-quarters of the programme communities. Qualitative research in the programme areas revealed that while most schools had the necessary basic infrastructure, there was substantial heterogeneity. Many had deficiencies in their facilities (for example requiring roof repairs or additional classroom space) and in availability of didactic materials (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010).

The amount of the conditional cash transfer varied with family composition. Families eligible for one (health or education) of the two components received 15 US $ per month, and families eligible for both components received 20 US $.Footnote8 USD The amounts were less than 10 percent of average household income among beneficiaries, smaller than for most other CCT programmes in the region (Beneke de Sanfeliú, Angel, and Shi Citation2015). This understates their potential importance for many beneficiaries, however, since the transfers were as much as one-third of income for families in the poorest two quintiles of the overall income distribution (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010). Moreover, in a beneficiary study done in late 2007 nearly one-half of families reported the transfers as their main source of cash income (Góchez Citation2008). Each nuclear family (including a parent or parents and their children) was eligible for their own transfers, independent of the number of co-resident nuclear families together in a single household, defined as individuals who regularly ate and slept there. Where possible, transfers were targeted to the mother.

The Salvadoran Social Investment Fund for Local Development administered the programme, contracting national and regional nongovernmental organisations (NGO) to implement the local field operations in one or more municipalities, including monitoring the conditionalities, coordinating transfer payments, responding to complaints and organising the workshops. At the municipality level, NGO personnel were the face of the programme. For example, they visited schools to collect the enrolment data used to determine compliance with conditionalities and payment of transfers. A 2009 assessment of six of a dozen implementing NGOs found modest variation across them in the prior experience they had working in the municipalities and in their execution of duties such as collecting the information required for monitoring (Britto Citation2007; IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010; Adato, Morales Barahona, and Roopnaraine Citation2016).

In addition to the demand-side components common to most CCTs, from the start the programme was paired with sizeable complementary investment programmes in the same municipalities, budgeted at about half the cost of the CCT programme itself (PNUD and FISDL Citation2011). The investments strengthened existing health and education services, the essential supply-side elements supporting the CCT (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010). They also improved basic water, sanitation and electric services, and roads. The investments targeted schools and health facilities and therefore benefited entire communities in the programme areas and not just the CCT beneficiaries.

2.2. Programme targeting

The CCT rolled out across municipalities based on the 2005 national poverty map (FISDL Citation2005). Cluster analysis using municipal-level extreme poverty rates and severe stunting rates for first-graders (height-for-age z-score less than −3.0), partitioned the 100 poorest municipalities into a ‘severe extreme poverty group’ (32 municipalities), where the programme began in late 2005 and in 2006, and a ‘high extreme poverty group’ (68 municipalities), where it began in 2007 and 2008. Within each group, municipalities were ordered by a marginality index based on poverty, education levels and housing characteristics and programme rollout largely followed that order (FISDL Citation2005; Britto Citation2007). The phased rollout has important implications for interpretation of our analyses, since municipalities that have been in the programme longer were at the outset poorer.

In rural areas, all nuclear families with a pregnant woman or a child up to 15 years old who had not yet completed sixth grade were eligible.Footnote9 Initial eligibility was determined at the time of incorporation. After the start of the programme in each municipality, the beneficiary roster was closed and new families were not eligible and could not be enrolled until after 2013.Footnote10 Beneficiary families lost eligibility if they repeatedly did not comply with the conditions, graduated out of the eligibility criteria (i.e. because their youngest child had become too old or all children had completed sixth grade) or moved out of the programme municipality.Footnote11 Compliance with conditions was high – above 98 percent for health and 90 percent for education in 2007 (Government of El Salvador Citation2008) – and most families who exited did so because they graduated out of eligibility (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010). There is evidence that programme conditions were monitored and enforced. In 2009 and 2010 about 10 percent of families reported discounted or suspended transfers, half of those for not fulfiling the education conditionalities (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2008; Citation2010).

2.3. Short-term evaluation impact evidence

In the short term the CCT was evaluated exploiting the non-experimental rollout that first incorporated municipalities in the severe extreme poverty group and then in the high extreme poverty group. Outcomes in the first group were compared with outcomes in the second group before the latter was exposed, and retrospective information collected in an evaluation survey used to construct difference-in-difference estimates. In addition, for some schooling outcomes the two groups were compared using the 2007 Salvadoran national census (VI Censo de Población y de Vivienda) to estimate first differences. For both data sources, the comparisons were strengthened by using a regression discontinuity design (RDD). The running variable was derived from the same factors (municipality-level extreme poverty rate and severe stunting among first graders) used for the original partitioned cluster analysis underlying the two extreme poverty groups (de Brauw and Gilligan Citation2011).Footnote12

de Brauw and Peterman (Citation2011) examined the health component of the programme after one year using the evaluation survey data. They found large improvements in maternal health-seeking behaviour at the time of birth (giving birth in a government or private hospital and, relatedly, with skilled attendants present – both a doctor and nurse) but no effects on pre- or postnatal care. For under-three-year-olds, there was also some evidence of reductions in the prevalence of diarrhoea in the last 15 days and in the percent stunted (height-for-age z-score below −2.0), although these findings may have resulted from pre-programme differences between the severe and high extreme poverty groups (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010).

de Brauw and Gilligan (Citation2011) examined the education component of the programme using the evaluation survey data as well as the 2007 national census data. Results were broadly consistent using the two data sources; we describe the findings based on the national census since they are reported in single-year cohorts. The authors find that the programme significantly increased preschool and primary school enrolment one year after the start of the programme. There were particularly large improvements in enrolment of six-year-olds in preschool (approximately 15 percentage points on a base of 65 percent in 2007) and enrolment for seven-year-olds in primary school (approximately 9 percentage points on a base of 90 percent in 2007). Effect sizes were smaller but significant for older age groups through age 12 except for 10-year olds, possibly due to measurement error associated with age-heaping. de Brauw and Gilligan do not report impact estimates for five-year-olds, an age group we examine below. Evaluation reports, however, do mention that an increase in enrolment in preschool for four- and five-year-olds resulting from the programme is possible (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010).

There were also several other general short-term impacts of the programme. Consistent with beneficiary families signing an agreement with the programme regarding how they would spend the transfers (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010). Nearly all beneficiaries reported spending a portion of the transfers on food and about half on medicine (Beneke de Sanfeliú, Angel, and Shi Citation2015). This occurred even though expenditures were not a conditionality and were not explicitly monitored, a finding also observed in other contexts and consistent with an important role of social marketing in CCT programmes. Qualitative research in 2009 and 2010 demonstrated a strengthening of female empowerment, stemming in part from the training workshops (Adato, Morales Barahona, and Roopnaraine Citation2016). A separate study found a related increase in social capital for women, and greater financial inclusion for some beneficiaries in 2014 (Beneke de Sanfeliú, Angel, and Shi Citation2015).

Taken together, the research on the first few years of operation suggests modest programme effects in early childhood and more substantial effects at early school ages. Because the transfer sizes were relatively small, these early results may reflect a shift in parental behaviour beyond the income or price effects of the programme, increasing the likelihood of enduring effectiveness. This possibility is buttressed by the findings related to female empowerment and social capital that could influence later programme effectiveness. Modest changes made to the programme also may have influenced its ongoing effectiveness. In 2010 after various evaluations, the government adjusted the programme to improve performance of the implementing NGOs, for example introducing clearer operating procedures for their various responsibilities.

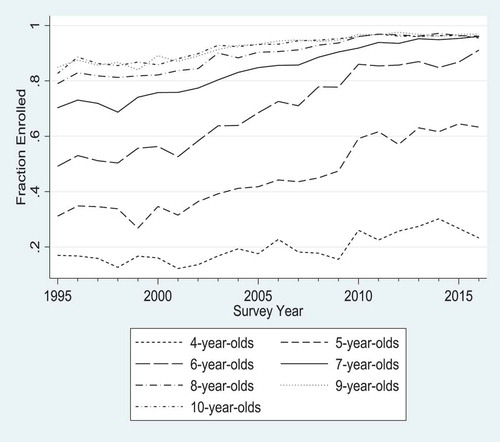

In this paper, we examine whether the short-term impacts in preschool enrolment for young school-age children in 2007 (at the start of the programme) are observed for similarly aged children in 2013, after they had been exposed to the programme since birth. Central to the interpretation of our results is how school enrolment evolved over the period in rural El Salvador. Improvements in both preschool and primary school have been important policy goals for the government and coverage, enrolment and quality have risen, although all are lower in rural areas (Ministry of Education Citation2013).Footnote13 In we present national rural enrolment rates by age using annual repeated cross-sectional household surveys from 1995 through 2016 (IDB Citation2018). Average enrolments have been increasing for all ages, with the largest gains in the last decade for five- and six-year-olds. By 2012, 57 percent of five-year-olds were enrolled (virtually all in preschool) and 86 percent of six-year-olds (65 percent in preschool and 21 percent in primary school). Enrolment rates for both seven- and eight-year-olds had reached 95 percent.

3. Data and methodology

The CCT administered a programme census in late 2012 and 2013 to recertify ongoing beneficiaries and identify new eligible families in the 56 poorest rural municipalities (from the original 100), including those whose first children had been born during closed enrolment after the start of the programme. The programme had begun at different times between September 2005 and March 2008. We use the data from this census to analyse impacts after 5–6 years of operation. Our identification strategy compares outcomes for children in families who were just eligible with those in families who were just ineligible, as determined at the time of programme incorporation in their municipality in 2005 to 2008.

The 2012/13 administrative programme census collected information for all individuals, including date of birth, schooling, and maternal and paternal relationships, and for all households, including ownership of assets and housing characteristics. We use the maternal relationships within each household to identify all co-resident children of each woman and define these children and their mother (and father if present) as a single nuclear family. A household in the census can contain more than one nuclear family, for example if co-resident adult sisters each have young children. The CCT targeted the nuclear family. Therefore, although rare, it was possible for multiple nuclear families co-resident in a single household to each receive their own benefits.Footnote14 For each nuclear family, we keep only the oldest child (or both if twins, which occurs in about one percent of the sample). We then keep only the five- or six-year-olds and assume that child was the firstborn child. This is the sample used in the main analyses.Footnote15

We then compare the date of birth of each firstborn child with the date of programme incorporation in their (current) municipality of residence to determine whether the child (and their family) would have been eligible.Footnote16 Assuming that a woman would have known she was pregnant with her first child at the end of the first trimester, and therefore would have reported the pregnancy during programme incorporation, we consider families of all firstborn children born within six months after the initial incorporation date in their municipality to be eligible. They form the treatment group. Families with firstborn children born more than six months after the incorporation date are not considered eligible, since the mother had no other (older) children at the time of incorporation and likely learned of her pregnancy or became pregnant afterwards; they form the ineligible comparison group.

shows how we use date of birth of the firstborn child, the programme incorporation date in the municipality and the six-month lag to delimit eligibility. We consider three windows of birthdates: i) an 8-month window including four months before and after the eligibility cut-off date; ii) a 12-month window (six months before and after); and to increase the number of observations and power, iii) a 24-month window (12 months before and after).Footnote17 All children born prior to the cut-off are considered eligible and all born after, ineligible. Within the 24-month window sample, for example, eligible children were born between six months before and six months after the programme incorporation date, and ineligible children between 6 and 18 months after that date. As described above, the short-term evaluation studies provided evidence that first-time mothers who were not pregnant until after the initial incorporation did not in general gain access to the programme. If some families with children born just after the cut-off did gain access, then the ITT results would likely underestimate programme impacts since we treat them as ineligible.Footnote18 The sample is restricted to firstborn children rather than including all children born in these ranges because any child with older siblings would have been in an eligible nuclear family at programme incorporation regardless of where his or her own birthdate falls relative to the eligibility cut-off.

Figure 2. Date of birth of firstborn child relative to programme incorporation date.

We study programme impacts for children in separate, single-year age brackets. Although in the 24-month window the range of possible birthdates relative to the eligibility cut-off span 24 months, at the time of measurement all children in the analysis of the five-year-old age group are between 61–72 months old and all those in the six-year-old age group, between 73–84 months old. Even with this restriction, however, eligible children will on average be older than ineligible children when measured.

If the 2012/13 administrative programme census had been completed in a single day in each municipality, all eligible children within a municipality would be older than all ineligible children in that same municipality. Different interview dates as the fieldwork progressed within each municipality, however, imply that despite having been born later, some ineligible children were older than some eligible children from the same municipality at the time of measurement. Consequently, for the 8-month window, the unconditional average age difference between eligible and ineligible firstborn children is only 1.1 months for both age groups, and for the 12-month window 1.3–1.4 months. For the 24-month window, differences are larger: 2.2 months for five-year-olds and 2.6 months for six-year-olds. These patterns make flexible controls for age essential for analysing child schooling outcomes, especially for the wider windows. For that reason, all models include binary monthly age indicators so that identification is based on comparisons of children at most 30 days older or younger than one another, and on average 15 days older or younger. There is nearly complete common support for age in months of eligible and ineligible firstborn children across all windows and both age groups.

The relationships between the programme incorporation date, birthdate and the 2012/13 administrative programme census interview date also make possible inclusion of municipality- or finer-level geographic fixed effects, strengthening the identification strategy. In the main analyses we include fixed effects for each canton, the administrative level below the municipality, averaging approximately 250 households. The canton-level fixed effects control for any additive effects resulting from possible differences across the implementing NGOs as well as other possible programmes or policies implemented in some but not all of the 56 municipalities.

A key identification assumption is that eligible and ineligible firstborn children conceived in a short interval around three months before the programme incorporation date in their municipality are comparable in terms of observable and unobservable characteristics, except eligibility for the CCT. The setup is similar to a RDD in which the running variable is the difference between birthdate and the eligibility cut-off date. Because of the small sample sizes in narrow intervals (yielding relatively low density of observations near the cut-off) and imprecision regarding the exact cut-off date that was binding for each family, however, we do not use the standard RDD specification as our main analysis. We do consider it in sensitivity analyses and find similar or larger results suggesting the ITT approach is, if anything, conservative (see section 4.2).

We estimate the following single-difference ITT equation using ordinary least squares (OLS):

where: Yic is the outcome for firstborn child i in geographic area c; eligibleic indicates whether the nuclear family in which the child lived was eligible for the programme (determined at the time of programme incorporation in that geographic area); Xi is a vector of individual- and family-level characteristics including an indicator of whether the child is female, binary monthly age indicators and the age and education of the household head; αc are the geographic-level fixed effects; and εic represents an idiosyncratic error term. is the ITT estimate of the programme effect. All analyses control for canton-level fixed effects and standard errors are adjusted for clustering at that level.

The timing of programme rollout and the 2012/13 census, in combination with the identification strategy, enable examination of five- and six-year-olds, critical ages for school-entry decisions including preschool. As described earlier, we estimate the impacts on five- and six-year-olds separately. Direct comparison of results for the two age groups is complicated by the differences in length of exposure as well as possible heterogeneous programme impacts by initial municipality poverty level, which differs for the two age groups because the CCT first began in poorer municipalities. In other words, we do not treat the six-year-old cohort as equivalent to the five-year-old cohort, except one year older. The information available in the 2012/13 administrative programme census permits examination of basic schooling outcomes as well as ownership of assets and housing characteristics of the household. Specific outcomes at the individual level include: i) whether the child is currently enrolled in any level of school; ii) whether the child has completed at least one year of school, including preschool; and iii) whether the child has completed at least one year of primary school (for six-year-olds only). Separately, for the family of each five- and six-year-old we explore a potentially important mechanism for changes in schooling – as well as an important outcome in its own right – household wealth. We use principal components of the assets and housing characteristics to construct a household wealth index described in Section 4.1. In addition to results estimated using OLS, for the wealth index we also present median regressions. For individual-level outcomes, because we keep only the firstborn child apart from cases of twins there is one observation per nuclear family. After excluding a small number of observations with incomplete information, we use the same sample for the household-level wealth index.

4. Results

4.1. Intent-to-treat effects of the Salvadoran conditional cash transfer programme

4.1.1. Schooling

presents summary statistics for the samples of firstborn children who fall within the 24-month window, 12 months before or after the eligibility cut-off date.Footnote19 Nearly half of five-year-olds were enrolled in school at the time of the census (42 percent of ineligible and 54 percent of eligible), modestly higher than the national rural average six years prior in 2007 (). Over 80 percent of six-year-olds were enrolled (81 percent of ineligible and 86 percent of eligible), more than 15 percentage points higher than reported in the 2007 baseline program evaluation survey (de Brauw and Gilligan Citation2011). As expected given the municipal-level program targeting, the 2012/13 census enrolment rates are similar to or a little lower than the 2012 national rural sample shown in . At the national level 57 percent of five-year-olds were enrolled in preschool and 86 percent of six-year-olds in school. Unconditionally, eligible children have similar or better schooling outcomes than ineligible children, possibly in part because they are on average 2.2–2.6 months older. Taken together, the evidence from the 56 program municipalities tracks the national increases over time and suggests higher enrolment rates for eligible compared with ineligible children.

Table 1. Individual characteristics of children and households in 24-month window by age.

Examination of whether parents work and a range of household characteristics, on the other hand, indicates relatively few differences between the two groups for each age despite the possibility the program could have influenced them, except that as would be expected eligible families have slightly more children (). More than half of the families are in households that have electricity and nearly half have good quality water, defined as a running tap in the house or compound. Owning a vehicle is uncommon, most households have a cell phone, three-quarters have a radio or television (and 40 percent have both), and about a third have a refrigerator or washing machine. Several of the household characteristics are slightly lower quality for eligible compared with ineligible children, possibly because the program started in more marginal municipalities first.

In we present characteristics unlikely to have been influenced by the program including parental age and education, in part to assess balance. There are few differences between groups in these measures. Starting in 2009, the government began implementing other important programs targeting some or all the 56 municipalities. These included a national non-contributory old age pension for people 70 years and older of 50 US $ per month, about three times the size of the CCT transfer. In some municipalities they also included rural agricultural development programs to increase food security among smallholder farmers through improved production and storage (de Saneliú, Lustig and Oliva Citation2015). These programs provided an agricultural package including various inputs and technical assistance. A potential concern for the analysis is that CCT beneficiary households might have had greater access to these other programs, in which case the effects we estimate could reflect impacts of both the CCT and these other programs. In , we compare whether households had a resident age 70 or over, received the agricultural package or another relevant household program (utility subsidies). For the generous old-age pension, there is almost no difference in potential eligibility across those eligible or not for the CCT, with only a small fraction of households having a co-resident elderly person. For the other programs, receipt differs modestly for the different age groups but mostly favours the ineligible households, especially for families of the five-year-olds. We conclude that possible unequal access to these other programs is unlikely to introduce substantial bias in the estimates of the effect of the CCT.Footnote20

Table 2. Household characteristics of families of children in 24-month window by age.

We estimate the effect since birth of up to six years of exposure to the CCT. If eligible families remained in the program throughout (which required complying with the conditionalities), estimated impacts are the net result of a combination of both long- and short-term potential effects. Longer-term effects arise because children (and their families) were benefiting from the transfers, conditionalities and other program activities since birth; shorter-term effects are more directly related to the current program activities. For each outcome and age group we present 8-, 12-, and 24-month windows but focus the discussion on the 24-month window, which empirically yields the most conservative (and most precise) point estimates for nearly all outcomes. Results show the estimation of EquationEquation 1(1)

(1) .

After 5–6 years of exposure, CCT program eligibility increased the probability that a five-year-old was enrolled in preschool by 12.3 percentage points, an approximate 30 percent increase over the enrolment rate of 42 percent for ineligible five-year-olds (). Related, the program increased the probability that the child had completed some schooling (i.e. preschool) by 8.7 percentage points, a 20 percent increase. Effect sizes are similar for the shorter 12-month window and substantially larger for the 8-month window where age and other differences between eligible and ineligible children and their families are the smallest, though the estimates on this smaller sample are less precise and insignificant in the case of completed schooling. This pattern of larger effect sizes for narrower windows is the opposite of what one would expect if age differences were driving the results, lending further credibility to the research design. The effects are consistent with the possibility of long-term impacts or a role for current transfers and conditionalities of the CCT program, which requires five-year-olds to enrol in preschool when one is available. Consequently, the results indicate that the CCT was effective at promoting preschool enrolment, particularly for five-year-olds in the high extreme poverty municipalities.Footnote21

Table 3. (a) Effect on individual-level school outcomes for five- and six-year olds.

Table 3b. Placebo on Individual-Level School Outcomes for Five- and Six-year-olds.

In contrast, for six-year-olds estimated effect sizes are smaller and generally insignificant: there is little evidence of a program effect on enrolment or having completed at least one year of school. The different effects for the six-year-olds compared to the five-year-olds may be partly explained by national enrolment increases over time () and the positive association of enrolment and age. There is less room for improved enrolment for six-year-olds in 2012 than there was for example in 2007 when the short-term evaluation was done. It might also reflect differences in impact related to the poverty differences between the severe and high extreme poverty groups. Irrespective of the underlying reasons, it is notable that whereas in its first years of operation the CCT had large effects on six-year-olds (de Brauw and Gilligan Citation2011), approximately five years later it had similarly large effects on children one year younger.Footnote22

To shed light on whether cumulative or current effects underlie the findings, we consider narrower age ranges and exploit the conditionality rules that children who had not turned five by the start of the school year were not subject to the conditions, even when a preschool was available in the community. In , we first present results for six-month age groups: 61–66, 67–72, 73–78 and 79–84 months old. Because the range for each group is narrower, even the 24-month window yields average age differences between eligible and ineligible children that are smaller than those reported above. Separately, we also split five-year-olds into two different groups, those born from March through August and from September through February. The youngest (61–66 months) and those born March–August are two groups of five-year-olds who were less likely to have turned five by the start of the school year (which runs from February through November) and therefore not subject to school conditionality requirements that year.

Table 4. Effect on completed schooling and wealth index, by Narrow Age Group.

Results for having completed at least one year of school are shown in the top panel of for the 12- and 24-month windows. Despite the reduced precision for these narrower age groups with correspondingly smaller sample sizes, point estimates indicate larger effects for the youngest group (61–66 months of age) and for five-year-olds born March to August, groups for whom the conditions were yet not binding. At the same time there is, if anything, an estimated negative effect for the 73–78 month-olds, compared to a much higher mean in the comparison. Although not conclusive, the patterns suggest that improvements in enrolment were not primarily because of the current conditionality but rather may result from earlier benefits from the program (for example making them better prepared for school) or shifts in norms around investment in children associated with nearly six years of program exposure.

The above results are all based on relatively narrow windows that flexibly control for age. To provide further evidence that age differences between eligible and ineligible children are not driving the results, we estimate two placebo models. The first uses the same age groups and cut-off dates to assign placebo treatment and control status but includes children in the age groups who were not firstborn in their families and had an older sibling under 15 years of age so that all were eligible by virtue of being in a family with an older eligible sibling.

The second placebo model compares only firstborn children when neither child was eligible for the program or, separately, when both were eligible, as shown in . More specifically, for five-year-olds in the 24-month window, we drop the eligible children born before the cut-off, relabel the original ineligible group as the treatment, those born in the 12 months after the cut-off (months 6 to 18 in the figure) and construct a placebo control group of those born between 12 and 24 months after the cut-off (months 18 to 36 in ). By construction, all children in both groups were ineligible for the CCT. In similar fashion, for six-year-olds in the 24-month window, we drop the ineligible children, relabel the original eligible group as the control, i.e. those born in the 12 months prior to the cut-off (months −6 to 6 in the figure) and construct a placebo treatment group of those born between 12 and 24 months prior to the cut-off (months −18 to −6 in the figure). By construction, all children in both groups were eligible. (A parallel procedure defines the 12-month window for this firstborn placebo group, as shown in .)

Figure 3. Date of birth of firstborn child relative to programme incorporation date: 24-month window (Placebo).

There is little evidence of treatment effects from the two placebo models, with insignificant and relatively small point estimates for both ages and outcomes (). This provides further evidence that we adequately control for age differences (and other confounders) across the eligible and ineligible groups in the main analyses.

4.1.2. Household wealth index

To explore an important potential mechanism for improved schooling outcomes, increased wealth, we examine an index of household wealth using principal components analysis to aggregate ownership of assets and housing characteristics (Filmer and Pritchett Citation2001). We exclude water and electricity indicators from the index because of the complementary programmes implemented to increase their access and availability to all households in the programme municipalities. The principal components are estimated using all households in the 56 municipalities (approximately 75,000), irrespective of family eligibility, based on ownership of six assets (cell phone, cable internet, radio, television, refrigerator or washing machine, and vehicle) and housing characteristics including a latrine, good quality floor, walls and roof and number of rooms. We retain the first principal component, which explains 28 percent of the total variation. All but one of the included measures have positive loadings greater than 0.2 ().

The main ITT effects of the CCT on the household wealth index are shown in the top panel in for the samples of families with five- or six-year-olds. Although wealth is a household-level outcome, we examine the age groups separately for three reasons. First, families of six-year-olds have been exposed on average one year longer. Second, 60 percent of eligible families with a six-year-old in the sample had more than one child at the time of the 2012/13 programme census, and therefore for the prior two years those families would have had the potential to receive the larger transfer (20 versus 15 US $) with a child under five and another five or older.Footnote23 Third, because of the order of programme rollout, families of six-year-olds all come from the severe extreme poverty municipalities.

Table 5. Effects on and placebo tests for household-level wealth index for five- and six-year-olds.

There is no evidence of increased wealth as measured by the index for families of five-year-olds, but substantial improvements for the families of six-year-olds. For the 24-month window, the OLS and median regression estimates for six-year-olds indicate an increase of 0.3 standard deviations or more (). For the narrower 8- and 12-month windows, the effects more than double. Although estimated magnitudes are large in standard deviation terms, they appear to reflect relatively small absolute differences in wealth in these poor, rural communities. For example, just the ownership of a refrigerator or washing machine is associated with a 0.4 increase in the wealth index (). Placebo tests for children who are not firstborn show little evidence against the validity of this estimation approach (bottom panel, ).Footnote24

Examining more closely the timing of these effects, we also estimated the ITT effect on the household wealth index for the six-month age groups (). Strikingly, most of the impact for the six-year-olds is concentrated in the oldest group (79–84 months). Along with the evidence of no effects on wealth for the five-year-olds, this suggests that the observed wealth effects do not reflect a long-term accumulation resulting from continued receipt of transfers. Rather, they are consistent with families being able to allocate some of the additional resources resulting from the increased transfer size (15 to 20 US $) to asset accumulation, possibly because for most six-year-olds the school enrolment conditionality was nonbinding.

In theory, the wealth effect also could arise from an increase in labour force participation and income in eligible households. In particular, maternal labour market participation (for example related to possible increases in labour productivity during the CCT) could be an independent mechanism explaining increased enrolment of young children as mothers aim to reduce their responsibilities in the home. This is less likely in this rural context, however, because female labour force participation is low (less than one-quarter) and because about half of mothers with a firstborn five- or six-year-old also had a younger child not yet of preschool age at home. Indeed, indicates no strong evidence of differences in work patterns for eligible compared to ineligible mothers.Footnote25 Hence the impacts on early enrolment and wealth cannot be explained by changes in female employment activities.

4.2. Limitations and sensitivity analyses

Section 4.1 demonstrates that the main results, all of which control for gender, age in months and canton-level fixed effects, are broadly similar for the different windows of inclusion. If anything, effect sizes are larger for narrower windows despite the smaller age differences between eligible and ineligible children, suggesting that age effects do not appear to be driving the results. In this section we explore three important limitations of the analysis and examine further the sensitivity of the main results. First, given the timing of the available post-intervention information in 2012/13, and the possibility of selective in- or out-migration for young families and their children since the start of the CCT, we explore the likely extent of migration using national census data. Second, we consider an alternative RDD estimation strategy, using the distance in days between birthdate and the cut-off date as the running variable. Third, we examine whether results are sensitive to eligibility cut-offs coinciding with calendar year cut-offs related to official guidelines on ages for starting school.Footnote26

4.2.1. Migration selectivity

Given high levels of Salvadoran domestic and international migration, an important concern for the validity of the results is potential selective migration of families with young children into or out of programme municipalities during the period between the initial programme incorporation and the 2012/13 programme census.Footnote27 Such migration could involve entire families, women of childbearing ages (just prior to giving birth) or only the firstborn child. If individuals migrating out are selected, ITT estimates based on the remaining families are biased. Complicating the potential bias, families that migrated into the areas after the programme started, and are therefore not eligible for the CCT, may be misclassified in the analysis as eligible based on the age of their firstborn child. A further potential source of bias is that the CCT itself may have influenced migration. Arguably the focus on young children and families, a less mobile population than teenagers or young adults without children, reduces these concerns somewhat, but not entirely.

We used the most recent Salvadoran national census to estimate historical absolute in- and out-migration rates in the 56 rural municipalities prior to 2007. The national census includes current municipality of residence and number of years there, previous municipality and municipality of birth. In-migration increases with age reaching nearly three percent for five- and six-year-olds while out-migration, also increasing with age, is half that. Unless patterns changed substantially since then, it is plausible that such levels of migration may not lead to highly selective samples in 2012/13. For example, the estimated effects on enrolment for five-year-olds would be reduced by 0.06 in an extreme bounds case (assuming in-migration and out-migration were both 3 percent and every child – whether migrating in or out, eligible or ineligible – behaved in a fashion to reduce the estimated impact). That is, when every age-eligible firstborn child moving in, and therefore misclassified as eligible, was not enrolled in 2012/13, whereas every age-ineligible firstborn child moving in was enrolled – and vice versa for those moving out. Based on this bounding exercise, the most conservative estimate for the 24-month window would be reduced by half, from 0.12 to 0.06. We conclude that selective in- or out-migration for these young families is not likely to have changed the substantive conclusions of the analysis.Footnote28

4.2.2. Regression discontinuity design

As described in section 3, the research design is similar to RDD in which the running variable is defined as the number of days between the date of birth and the eligibility cut-off. After partialling out all controls used in the main models, we implement a standard RDD estimation on the residuals. Using a linear smoothing function, except for six-year-olds completing one year of primary school, the RDD estimates of the local average treatment effect have the same pattern of significance and the significant RDD estimates are similar or larger in magnitude to the main specifications (). Although not our preferred approach because of the low density of observations near the cut-off dates as well as imprecision regarding the exact cut-off date that was binding for each family, these findings are similar to the OLS results and provide further evidence results are not driven by age differences.

4.2.3. Timing of birth and the school year

A third potential concern is that rather than the effect of the CCT, the identification strategy instead picks up the effect of official age-eligibility rules for enrolling in school (Berlinski, Galiani, and McEwan Citation2011). If the CCT eligibility cut-off date coincides with the period just before the start of the school year, children whose birthdays are also just before the cut-off might be more likely to enrol in that year but not necessarily because of the programme. A priori, this seems unlikely because most enrolment at the ages we study is in preschool, not primary school. Moreover, as explained earlier the legal age for starting primary school in El Salvador is seven, although six-year-olds can enrol if deemed prepared.

Because the school year runs from February to November, children with birthdays in December, January or February, are those most likely to face binding constraints on enrolment if official Ministry of Education rules are enforced. To assess sensitivity to this concern, we rerun the schooling analyses excluding all municipalities for which the eligibility cut-off date falls in December, January or February. Estimated results are similar though less significant (consistent with smaller sample sizes), suggesting the main analyses do not suffer from bias related to official ages for starting school ().

5. Conclusions

Rigorous evaluations of ongoing CCT programmes are uncommon. Assessing programme impacts after several years of implementation is particularly important for both researchers and policymakers trying to understand whether programmes remain (as) effective or lead to longer-term impacts. Various patterns including increasing or decreasing impacts might materialise. On one hand, it is possible that valuable programme learning occurs in the early years and effects become larger over time as operations improve or become more efficient. On the other hand, if programme activities or benefits are captured by rent-seeking or corrupt agents, effects may become smaller. Early positive results also may be the product of enthusiastic programme kick-offs and evaluations that are highly visible to both beneficiaries and programme operators; enthusiasm and effort on the part of the beneficiaries or the programme implementation team could wane over time, leading to decreased effectiveness.

In addition to these operations-related aspects, observed impacts also may change as a direct result of continuous programme exposure. Outcomes measured after five or six years, for example, may be enhanced by earlier programme effects, including dynamic complementarities between investments earlier and somewhat later in life (Cunha and Heckman Citation2007) or changing norms regarding child investment (Macours, Schady, and Vakis Citation2012; Macours and Vakis Citation2018). Evaluations of ongoing programmes can provide clues as to whether later programme effects result from the cumulative effect of the programme, reflecting potential synergies – for example across nutrition, health and education – often used to justify these programmes, as well as the possibility that they affect norms. Last, other trends such as nationally occurring increases in schooling, can moderate achievable impacts.

For the CCT programme in El Salvador, now operating for more than a decade, we used programme census data and eligibility rules to examine effects after 5–6 years of exposure. Although available data do not provide the full range of measures for a fully comprehensive assessment of benefits, we show that the CCT improves early schooling outcomes of five-year-olds exposed since birth. Results are estimated on an ITT basis and, although take-up was high, in that sense are conservative. Moreover, results are robust to different specifications and estimation approaches and to the threat of selective migration into or out of the programme municipalities.

The Salvadoran CCT, therefore, continued to deliver results half a decade after it began. The pattern of impacts, somewhat higher for groups that were eligible but not yet under full binding conditionality compared to others, suggests continued programme exposure might be improving school readiness or shifting norms favouring child investment. In comparison with the short-term evaluation results for the same programme, the largest effects on early schooling are no longer for six-year-olds; instead, they are for children one year younger. The CCT appears to be getting children into preschool at younger ages compared to when it first began, and as such possibly contributed to an easier transition into primary school and lower early grade repetition, a stated policy objective. These impacts were achieved in a context in which coverage and quality of preschools also improved modestly, possibly in part as result of the programme. This suggests that future longer-term assessments using other similar data sources would be informative. One possibility is the next Salvadoran national census currently scheduled for 2022, for which the identification strategy outlined here could be used on the same cohort when they are 14 and 15 years old.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (162.2 KB)Supplementary material

The supplemental data for this article can be accessed here

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

John A. Maluccio

Sanchez Chico is at the Organisation for European Cooperation and Development ([email protected]), Macours at the Paris School of Economics and INRAE ([email protected]), Maluccio at Middlebury College ([email protected]), and Stampini in the Social Protection and Health Division at the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB) ([email protected]). Support was provided by the IDB Economic and Sector Work ‘CCT Operational Cycles and Long-Term Impacts’ (RG-K1422). We thank the Government of El Salvador for providing the data and programme materials used for the analysis and María Deni Sanchez for her support throughout. We also thank Teresa Molina Millán, Tania Barham, Pablo Ibarrarán, Norbert Schady, Luis Tejerina, Diether Beuermann Mendoza, Ana Sofia Martinez, participants in presentations at the IDB and anonymous referees for valuable comments. All remaining errors are our own. This paper modifies and extends IDB working paper 908. The content and findings reflect the opinions of the authors and not those of the OECD or of the IDB, its Board of Directors or the countries they represent.

Notes

1. Calculations based on IDB Sociometro, available at https://www.iadb.org/en/research-and-data//social-transfers,7531.html, combined with information on programmes in Jamaica and the Bahamas. Stampini and Tornarolli (Citation2012) describe the expansion of CCT programmes in the region; Robles, Rubio, and Stampini (Citation2017) characterise coverage of the poor; and Ibarrarán et al. (Citation2017) describe CCT programme functioning.

2. Originally called Red Solidaria, a new government renamed the programme to Comunidades Solidarias Rurales in 2009. The CCT programme itself did not change substantively.

3. Molina Millán et al. (Citation2019) review the methodological challenges and evidence for the longer-term impacts of CCTs.

4. There is a related debate on the longer-term effects of unconditional cash transfers (Bandiera et al. Citation2017; Banerjee et al. Citation2016; Handa et al. Citation2018; Haushofer and Shapiro Citation2018).

5. Therefore, it also is not feasible to carry out cost-benefit analyses since we only examine a subset of the various possible beneficial outcomes resulting from the CCT.

6. The education transfer eligibility age cut-off was raised to 18 for municipalities entering the programme starting in 2008, but the change is not relevant for our analyses (de Brauw and Peterman Citation2011).

7. To our knowledge, Familias en Acción in Colombia was the only other CCT programme at the time with similarly explicit conditionality on preschool enrolment, but evaluation reports do not directly examine it as an outcome.

8. The transfer amounts were calculated to cover approximately one-quarter of the 2004 monthly minimum wage for agricultural activities, set at $74.10. A single transfer was equivalent to 37 percent of the 2005 Salvadoran monthly per capita rural poverty line (Britto Citation2007). Transfers were combined for delivery every other month.

9. Beginning with urban areas in the high extreme poverty group municipalities, a proxy means test (PMT) based on initial ownership of assets and housing characteristics was used along with the demographic criteria to determine programme eligibility (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010). We do not observe the initial information required to estimate the PMT score for families when the programme began. Therefore, we examine only rural areas in this study, where there was no PMT-related eligibility requirement.

10. Closed enrolment was widely enforced. Local programme promoters, however, could request that a nuclear family erroneously excluded during programme incorporation be included. The evaluations provide evidence of a significant negative consequence of closed enrolment, increasing under-coverage of the poor over time (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010).

11. By 2014, fewer than two-thirds of original beneficiaries continued to receive transfers (Beneke de Sanfeliú, Angel, and Shi Citation2015).

12. The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and the Fundación Salvadoreña para el Desarrollo Económico y Social (FUSADES) carried out the short-term evaluation (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2008; Citation2009; Citation2010). The identification strategy for the evaluation is not feasible for assessing the accumulated impacts of the programme after several years of operation for two reasons. First, there were no further follow-up evaluation surveys representative of the region after 2010. Second, the 100 poorest municipalities had been included in the programme by 2010, leaving no potential comparison municipalities in the severe or high extreme poverty groups.

13. Dimensions of quality of early schooling appear to have improved over time in early programme years, including school organisation and functioning and teacher attendance (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2010).

14. Multiple nuclear families in a household make up less than five percent of the sample. Excluding them from the analysis sample leads to negligible changes in estimated results.

15. By the time of the 2012/13 census, of course, the composition of nearly all families would have changed relative to when the programme had begun. For example, some children may have migrated or died, so we cannot determine with certainty the firstborn child for each mother with the available data. For those children who could not be linked to their mother using maternal relationships (because the mother was not co-resident in the same household or was deceased), it is possible to use i) paternal relationships and ii) relationship with the household head or the grandparents to determine if they might be firstborn children. Children assigned to a nuclear family through the maternal relationship comprise 88 percent of the likely firstborn five- and six-year-olds and this is the sample we use. (Paternal relationships yield an additional 2 percent and household head or grandparent the remaining 10 percent.) There is no significant relationship between eligibility status and whether the firstborn child is determined through their mother. The coefficient estimate on the eligibility indicator is −0.026 for the 24-month window for six-year-olds, and 0.010 or smaller for all other samples. Including the likely firstborns determined through paternal and other relationships in the sample leads to similar findings (not shown).

16. To determine the start or incorporation date in each municipality, we use the start of the programme incorporation registry implemented in the municipality. On average, the registry fieldwork within each municipality lasted 45 days. Results reported below change little when we instead set the cut-off based on the last day of interviews in the municipality. The programme incorporation registry is not used more directly in the analyses, however because it does not contain information on children not yet born (our comparison group) nor is it possible to link individuals from it to the 2012/13 programme census.

17. Given limits of statistical power, particularly for the narrower windows, we do not report an examination of possible treatment effect heterogeneity.

18. Even if these cases were known, however, because those who gained access despite being initially ineligible would be a selected group, we would not treat them any differently for the ITT analysis.

19. Summary statistics are similar for samples within the 8- and 12-month windows ( and ) and do not differ between boys and girls (not shown).

20. Children enrolled in school also could benefit from schooling related programmes operating during the period, including a student packet targeted to students in all rural public schools (two uniforms, a pair of shoes and school supplies) and school meals and milk programmes which combined were approximately 0.4 percent of GNP from 2010 onward (Mesa-Lago and De Franco Citation2010; Beneke de Sanfeliú, Lustig, and Oliva Citation2015). In line with higher enrolments due to the programme, these are somewhat higher for eligible children.

21. Because not all children would have had access to preschool, overall average estimated effects reflect effects in communities with and without preschools, which could differ from local average effects in areas with or without preschool.

22. Because we estimate multiple outcomes on schooling for each age group, we also recalculated statistical significance within each age group and window using Bonferroni family wise error rates and the Benjamini and Hochberg (Citation1995) false discovery rates. All effects significant at five percent or lower for five-year-olds remain significant at least at 10 percent.

23. At the same time, this change would come with potentially higher private costs to the family, though on the margin they would likely be small since the main components of private costs to the adults, collecting transfers and time spent in the training workshops, would be unchanged (IFPRI and FUSADES Citation2008).

24. Firstborn placebo tests as in ) are not estimated for wealth in . They are not plausible placebos for effects on the household wealth index, since longer exposure to transfers may enable asset accumulation for the families of six-year-olds, all of whom would have been eligible.

25. Kirk (Citation2016) further examined adult time use patterns by gender in the short term. She found evidence of an increase of about an hour a day in adult male time spent in formal and informal productive work that was largely offset but a reduction for adult females. This is consistent with programme demands on the time of the mother being accommodated by a reduction in other activities.

26. A different concern, that we are unable to investigate empirically due to the lack of exogenous variation in the density of exposure, is the possibility of spillovers on the ineligible population. In theory such spillovers could be positive or negative. However, evidence of related CCT programmes (whose design allows identification of spillover effects through a partial population experiment) generally point to positive spillover effects on educational outcomes (Angelucci et al. Citation2010; Bobonis and Finan Citation2009; Macours and Vakis Citation2018), which would suggest our results provide a lower bound of the actual effects.

27. For migration internal to the municipality, which we also do not observe, the implication for the analysis is that canton-level fixed-effects do not accurately reflect the ITT residential location at the start of the programme. We therefore re-estimate results controlling for the more aggregate municipality-level fixed effects. Results are substantively unchanged ( and ).

28. In the online appendix, we also summarise findings using the 2007 Salvadoran national census to estimate potential short-term effects of the programme on migration rates in the first 32 municipalities receiving the programme in 2005 and 2006, and find they are modest.

References

- Adato, M., O. Morales Barahona, and T. Roopnaraine. 2016. “Programming for Citizenship: The Conditional Cash Transfer Programme in El Salvador.” Journal of Development Studies 52 (8): 1177–1191. doi:10.1080/00220388.2015.1134780.

- Angelucci, M., G. De Giorgi, M. Rangel, and I. Rasul. 2010. “Family Networks and School Enrollment: Evidence from a Randomized Social Experiment.” Journal of Public Economics 94 (3–4): 197–221. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2009.12.002.

- Araujo, M. C., M. Bosch, and N. Schady. 2018. “Can Cash Transfers Help Households Escape an Inter-Generational Poverty Trap?” In The Economics of Poverty Traps, edited by C. Barrett, M. R. Carter, and J.-P. Chavas 357-382. Chicago, IL, United States: University of Chicago Press.

- Bandiera, O. R., S. Burgess, N. Das Gulesci, I. Rasul, and M. Sulaiman. 2017. “Labor Markets and Poverty in Village Economies.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 132 (2): 811–870.

- Banerjee, A., E. Duflo, R. Chattopadhyay, and J. Shapiro. 2016. “The Long Term Impacts of a “Graduation” programme: Evidence from West Bengal.” Unpublished. MIT.

- Barham, T., K. Macours, and J. A. Maluccio. 2013. “Boys’ Cognitive Skill Formation and Physical Growth: Long-Term Experimental Evidence on Critical Ages for Early Childhood Interventions.” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 103 (3): 467–471. doi:10.1257/aer.103.3.467.

- Bastagli, F., J. Hagen-Zanker, L. Harman, G. Sturge, V. Barca, T. Schmidt, and L. Pellerano. 2016. Cash Transfers: What Does the Evidence Say? A Rigorous Review of Impacts and the Role of Design and Implementation Features. London: United Kingdom: Overseas Development Institute. https://www.odi.org/publications/10505-cash-transfers-what-does-evidence-say-rigorous-review-impacts-and-role-design-and-implementation

- Behrman, J. R., S. W. Parker, and P. E. Todd. 2009. “Schooling Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfers on Young Children: Evidence from Mexico.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 57 (3): 439–477. doi:10.1086/596614.

- Beneke de Sanfeliú, M., M. A. Angel, and M. A. Shi. 2015. “El Impacto de los Impuestos y el Gasto Social en la Desigualdad y la Pobreza en El Salvador.” Inter-American Development Bank Technical Note 775.

- Benjamini, Y., and Y. Hochberg. 1995. “Controlling the False Discovery Rate: A Practical and Powerful Approach to Multiple Testing.” Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B 57: 289–300.

- Berlinski, S., S. Galiani, and M. Manacorda. 2008. “Giving Children a Better Start: Preschool Attendance and School-Age Profiles.” Journal of Public Economics 92 (5–6): 1416–1440. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2007.10.007.

- Berlinski, S., S. Galiani, and P. Gertler. 2009. “The Effect of Pre-Primary Education on Primary School Performance.” Journal of Public Economics 93 (1–2): 219–234. doi:10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.09.002.

- Berlinski, S., S. Galiani, and P. J. McEwan. 2011. “Preschool and Maternal Labor Market Outcomes: Evidence from a Regression Discontinuity Design.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 59 (2): 313–334. doi:10.1086/657124.

- Bobonis, G., and F. Finan. 2009. “Neighborhood Peer Effects in Secondary School Enrollment Decisions.” Review of Economics and Statistics 91 (4): 695–716. doi:10.1162/rest.91.4.695.

- Britto, T. F. 2007. “The Challenges of El Salvador’s Conditional Cash Transfer Programme, Red Solidaria.” Country Study Number 9. Brasilia, Brazil: International Poverty Centre.

- Cahyadi, N., R. Hanna, B. A. Olken, R. A. Prima, E. Satriawan, and E. Syamsulhakim. 2020. “Cumulative Impacts of Conditional Cash Transfer Programmes: Experimental Evidence from Indonesia.” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy (forthcoming).

- Cunha, F., and J. Heckman. 2007. “The Technology of Skill Formation.” American Economic Review Papers and Proceedings 97 (2): 31–47. doi:10.1257/aer.97.2.31.

- de Brauw, A., and A. Peterman. 2011. “Can Conditional Cash Transfers Improve Maternal Health and Birth Outcomes? Evidence from El Salvador’s Comunidades Solidarias Rurales.” IFPRI Discussion Paper No. 01080. Washington, DC, United States: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- de Brauw, A., and D. Gilligan. 2011. “Using the Regression Discontinuity Design with Implicit Partitions: The Impacts of Comunidades Solidarias Rurales on Schooling in El Salvador.” IFPRI Discussion Paper No. 01116. Washington, DC, United States: International Food Policy Research Institute.

- de Sanfeliú, B., M., . N. Lustig, and J. A. Oliva. 2015. “Estudios de caso por países: Experiencias emergentes – El Salvador.” In Proteccion, Produccion, Promocion: Explorando Sinergias Entre Politicas De Proteccion Social Y Desarrollo Rural En Latinoamerica, edited by Maldonado, Moreno-Sanchez, Jomez, and Jurado. International Fund for Agricultural Development, Rome, Italy.

- Fernald, L. C. H., P. J. Gertler, and L. M. Neufeld. 2009. “10-Year Effect of Oportunidades, Mexico’s Conditional Cash Transfer Programme, on Child Growth, Cognition, Language, and Behaviour: A Longitudinal Follow-up Study.” Lancet 374 (9706): 1997–2005. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61676-7.

- Filmer, D., and L. Pritchett. 2001. “Estimating Wealth Effects without Expenditure Data – Or Tears: An Application to Educational Enrolments in States of India.” Demography 38 (1): 115–132. doi:10.1353/dem.2001.0003.

- Fiszbein, A., and N. Schady. 2009. “Conditional Cash Transfers: Reducing Present and Future Poverty.” World Bank Policy Research Report. Washington, DC, United States: World Bank.

- Fondo de Inversión Social para el Desarrollo Local de El Salvador (FISDL). 2005. Mapa De Pobreza: Tomo I. Política Social Y Focalización. San Salvador, El Salvador: FISDL.

- García, A., O. L. Romero, O. Attanasio, and L. Pellerano. 2012. “Impactos de Largo Plazo del Programa Familias en Acción en Municipios de Menos de 100 mil Habitantes en los Aspectos Claves del Desarrollo del Capital Humano.” Technical Report. Bogotá, Colombia: Union Temporal Econometria S.A. Sistemas Especializadas de Información, con la asesoria del Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- Góchez, R. E. 2008. “Percepción De Las/os Beneficiarios Del Funcionamiento E Impacto De Red Solidaria.” Informe entregado a Red Solidaria. El Salvador.

- Government of El Salvador. 2005. “Programa Social de Atención a las Familias en Extrema Pobreza de El Salvador: Red Solidaria.” Secretaría Técnica de la Presidencia (STP) Coordinación Nacional del Á Red en Acción. San Salvador, El Salvador: Government of El Salvador.

- Government of El Salvador. 2008. El Salvador: Red Solidaria-Taller de Análisis y Reflexión de Programas TMC. Cuernavaca, Mexico. 16 de enero 2008.

- Handa, S., L. Natali, D. Seidenfeld, G. Tembo, and B. Davis. 2018. “Can Unconditional Cash Transfers Raise Long-Term Living Standards? Evidence from Zambia.” Journal of Development Economics 133 (July): 42–65. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2018.01.008.

- Haushofer, J., and J. Shapiro. 2018. “The Long-Term Impact of Unconditional Cash Transfers: Experimental Evidence from Kenya.” Unpublished. Princeton.